Abstract

Glomerular extracellular matrix protein accumulation, mediated largely by mesangial cells(MC), is a defining feature of diabetic kidney disease(DKD). Previously we showed that TGFβ1, a profibrotic cytokine in kidney fibrosis, inhibits expression of the antifibrotic follistatin through induction of microRNA-299a-5p. Whether this microRNA contributes to DKD is unknown. We show that microRNA-299a-5p is increased in mouse and human diabetic kidneys, and by high glucose in primary MC. Overexpression of microRNA-299a-5p in MC increased basal ECM protein production. Conversely, microRNA-299a-5p inhibition prevented the glucose-induced profibrotic response. Bioinformatics screening revealed that cripto-1 is also a target of microRNA-299a-5p. Induction of microRNA-299a-5p by high glucose mediated the MC fibrotic response by inhibiting follistatin and cripto-1 which led to increased activin A and TGFβ1 signaling. In vivo, microRNA-299a-5p inhibition reduced clinical markers of DKD, and was associated with increased expression of follistatin and cripto-1. Thus, microRNA-299a-5p is an important mediator of glucose-induced profibrotic responses in diabetic kidneys.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is a major complication of diabetes mellitus, developing in up to 40% of patients. It is the leading cause of end-stage kidney disease, associated with reduced quality of life and increased mortality1,2. The current standard of care for DKD includes control of blood glucose and blood pressure, and use of inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, and for type 2 diabetics sodium glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors. However, current therapies, even in combination, are unable to halt DKD progression. The identification of novel therapeutic targets aimed at preventing disease progression is thus a major clinical need.

Initial pathologic changes of the diabetic kidney occur in the glomerulus, characterized by basement membrane thickening and mesangial expansion from accumulation of extracellular matrix proteins. The profibrotic cytokine transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1) is well known to be a major pathologic mediator of these changes3,4. However, the pleiotropic roles of TGFβ1 make its direct therapeutic targeting challenging. Previously, our lab identified that TGFβ1 inhibits the production of an antifibrotic protein, follistatin (FST) by mesangial cells (MC) through upregulation of miR-299a-5p5.

FST is a potent inhibitor of activins, members of the TGFβ superfamily, in particular activins A and B. The importance of both activins to fibrosis and DKD has been shown6,7,8. We had also shown that FST attenuated high glucose (HG)-induced matrix production by MC and reduced fibrosis in a model of DKD9. However, effects are attenuated at higher doses, indicating that administration may have a narrow therapeutic window. Novel strategies to increase endogenous FST may thus be more effective and better clinically tolerated.

miR-299a-5p is a member of the miR-154 family, the second largest miRNA cluster in the human genome. Containing over 40 members, it is highly conserved between species10. Members of this family are implicated in fibrosis in other organs. In idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), several members are increased including miR-299a-5p and miR-154, with the latter shown to heighten IPF fibroblast response to TGFβ111. miR-154 expression alone also increased cardiac fibroblast collagen production12, and its LNA inhibition protected against cardiac fibrosis and dysfunction in a pressure overload model13,14. Increased miR-299a-5p was also found in fibrotic liver from patients with primary biliary cirrhosis15. Our previous data show its increase in a hypertensive model of chronic kidney disease5, but whether miR-299a-5p contributes to the progression of fibrosis in DKD is unknown.

Here, we show that miR-299a-5p expression is significantly upregulated in glomeruli and tubules in both animal models of type 1 diabetes and in kidneys of type 2 DKD patients. HG increases the expression of miR-299a-5p by MC to inhibit FST production. Bioinformatics screening identified cripto-1 as an additional miR-299a-5p target. Unlike FST which has no neutralizing activity against TGFβ116, cripto-1 inhibits the actions of both activin A (actA) and TGFβ117,18. We hypothesize that inhibition of miR-299a-5p in vivo with anti-miR administration ameliorated DKD, in association with elevated expression of FST and cripto-1. Our study highlights a potential therapeutic role for miR-299a-5p inhibition in restoring endogenous antifibrotic protein expression to slow the progression of DKD.

Results

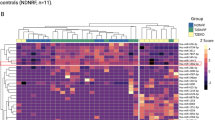

miR-299a-5p expression is increased by HG in MC and in mouse and human DKD

We first investigated the effects of HG on miR-299a-5p expression. HG, but not the osmotic control mannitol, increased the expression of miR-299a-5p in MC (Fig. 1a). Next, we confirmed miR-299a-5p overexpression in MCs after transfection with the miR-299a-5p overexpression plasmid using qPCR (Supplementary Fig 1a). For miR-299a-5p inhibition, MCs were transfected with the miR-299a-5p inhibitor, after which they were treated with HG for 72 h. Supplementary Fig 1b showed that miR-299a-5p expression was significantly increased by HG, but we did not see a significant reduction with the inhibitory plasmid as assessed by qPCR. This is not surprising given the mechanism of action of locked-nucleic acid inhibitors which do not lead to reduced expression of the target miR but rather prevent it from engaging its target19. We did confirm, however, that the miR inhibitor was functional by using a construct in which the miR-299a-5p regulatory element (MRE) is placed downstream of the luciferase gene5. Figure 1b shows decreased luciferase activity in HG, indicating increased miR-299a-5p binding, which was prevented by the inhibitor. We next assessed miR-299a-5p expression in vivo. By PCR, miR-299a-5p was increased in kidney cortex of CD1 streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice (Fig. 1c), confirmed by ISH (Fig. 1d, e). Increased expression was also seen in type 1 diabetic Akita mice (Fig. 1f, g), and in human DKD kidney biopsies (Fig. 1h, i). Expression was observed in both glomeruli and tubules, suggesting a role for this miR across kidney cell types. However, it is important to note that miR-299a-5p localization appears to differ across these tissues. These differences in miR-299a-5p localization may reflect differences in the models. The streptozotocin model represents an acute, chemically induced β-cell injury that results in rapid onset of severe hyperglycemia which may drive early and robust glomerular expression of miR-299a-5p20. In contrast, the Akita model develops diabetes due to a mutation in Ins2, leading to a more gradual and modest disease course21. The reduced glomerular signal in this model may therefore reflect differential regulation of miR-299a-5p in response to chronic rather than acute hyperglycemia. Age could also play a role in the differences seen20,21. Here CD1 mice given streptozotocin were 21 weeks old at harvest in comparison to 30-week-old Akita mice. In human DKD, the relatively lower glomerular expression is consistent with the heterogeneous and progressive nature of disease.

A miR-299a-5p expression was increased, as assessed by qPCR, after HG but not mannitol treatment of MC for 72 h. B miR-299a-5p MRE-Luc activity was assessed in MCs after HG (72 h), showing increased miR-299a-5p binding which was prevented by the miR inhibitor. C miR-299a-5p was increased in kidney cortex of streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetic CD1 mice, as assessed by qPCR. ISH showed an increase in miR-299a-5p expression in: D, E streptozotocin-induced type-1 diabetic CD1 mice, with blue staining indicating a positive signal; F, G in 40-week type 1 diabetic Akita mice; and in H, I kidney biopsies of type 2 diabetic patients (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). Data presented as mean ± SEM. The scale bar represents 100 µm.

miR-299a-5p promotes HG-induced profibrotic responses in MC

Previously, we showed that FST is a target of miR-299a-5p5, and that FST regulates both basal and HG-induced matrix production through its potent inhibition of actA9. We thus assessed whether miR-299a-5p regulates HG-induced fibrotic responses. We used plasmids to either inhibit or overexpress this miR5, with transfection efficiency measured by mCherry or GFP immunofluorescence respectively (Fig. 2a, e). MiR-299a-5p inhibition significantly attenuated HG (72 h) profibrotic effects, measured as collagen Iα1 luciferase activity (Fig. 2b) and matrix protein (fibronectin, collagen Iα1) and profibrotic cytokine (connective tissue growth factor (CTGF)) expression (Fig. 2c, d). Conversely, miR-299a-5p overexpression augmented basal collagen Iα1 promoter activity (Fig. 2f) and profibrotic protein synthesis (Fig. 2g, h) to levels seen with HG.

A MC were transfected with miR-299a-5p inhibitor or its control. Effective transfection was confirmed with mCherry immunofluorescence. B miR-299a-5p inhibition decreased collagen 1α1 promoter activation by HG (72 h). C, D miR-299a-5p inhibition decreased basal and HG-induced matrix protein and cytokine (CTGF) production. E miR-299a-5p was overexpressed in MC. Effective transfection was confirmed with GFP immunofluorescence. F miR-299a-5p overexpression increased collagen 1α1 promoter activation, with no additive effect by HG. G, H miR-299a-5p overexpression increased basal matrix protein and CTGF expression to levels seen with HG. I, J miR-299a-5p inhibition prevented HG-induced Smad3 activation, assessed by its C-terminus phosphorylation. K miR-299a-5p inhibition prevented HG-induced Smad3 transcriptional activation, assessed using the Smad3-responsive CAGA12 luciferase. L, M miR-299a-5p overexpression induced Smad3 activation, assessed by phosphorylation, to levels seen with HG, as well as N Smad3 transcriptional activation (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). Data presented as mean ± SEM. The scale bar represents 100 µm.

Profibrotic responses to HG in MC are known to require Smad322, which mediates both actA and TGFβ1 signaling3,6,23. We thus assessed whether miR-299a-5p mediates HG (72 h)-induced Smad3 activation. Figure 2i, j shows that miR-299a-5p inhibition prevented HG-induced Smad3 C-terminal phosphorylation, required for its activation. Smad3 transcriptional activity, assessed using its reporter CAGA12-luciferase, was also inhibited (Fig. 2k). Conversely, miR-299a-5p overexpression alone increased Smad3 phosphorylation and transcriptional activity to levels seen with HG (Fig. 2l–n). Interestingly, as for matrix protein synthesis, this was not augmented by HG, suggesting a major role for miR-299a-5p in Smad3 activation by HG.

miR-299a-5p inhibits expression of anti-fibrotic proteins cripto-1 and FST

We next assessed whether, in addition to FST, other potentially anti-fibrotic genes were regulated by miR-299a-5p. Bioinformatics screening of potential targets using TargetScan8.0, miRDB, miRWalk and Fireplex discovery engine revealed cripto-1, a known antagonist of both TGFβ1 and actA, as a target. As seen in Fig. 3a, the miR-299a-5p response element is conserved in the mouse and human cripto-1 3’UTR17,18. To confirm regulation by miR-299a-5p, we tested its effects on a cripto-1 3’UTR-luciferase reporter. Figure 3b shows that HG (72 h) reduced cripto-1 3’UTR luciferase activity. This was reversed by miR-299a-5p inhibition (Fig. 3c). As seen in Fig. 3d–f, both cripto-1 mRNA and protein expression were decreased by HG, with reduced FST expression also confirmed. Decreased cripto-1 and FST expression were also observed in kidney cortex immunoblots of type 1 DKD (Akita) mice (Fig. 3g, h), with cripto-1 reduction confirmed by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 3i, j). Reduction in cripto-1 and FST were confirmed in a second DKD mouse model (streptozotocin-treated, uninephrectomized CD1 mice) (Fig. 3k–n)24, and cripto-1 reduction also confirmed in human DKD biopsies (Fig. 3o, p).

A The miRNA regulatory element (MRE) for miR-299a-5p is conserved in the 3′UTR of mouse and human cripto-1. B Cripto-1 3’UTR-luciferase activity was attenuated by HG (72 h), and C this was prevented by miR-299a-5p inhibition. D Cripto-1 mRNA expression was reduced by HG (72 h). E, F Cripto-1 and FST protein expression were significantly reduced by HG (72 h) in MC, and G, H in type 1 diabetic Akita mice. IHC showed that expression of cripto-1 is reduced in type 1 diabetic Akita mice (I, J) and in CD1 streptozotocin-induced CD1 diabetic mice (K, L). M, N IHC for FST confirms its reduction in streptozotocin-induced diabetes. O, P IHC showing reduced CR-1 expression in human DKD kidney biopsies. Q, R miR-299a-5p inhibition prevented HG (72 h)-induced reduction of cripto-1 and FST protein expression in MC. S, T miR-299a-5p overexpression reduced cripto-1 and FST protein expression (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). Data presented as mean ± SEM. The scale bar represents 100 µm.

We next sought to confirm that the regulation of cripto-1 by HG is mediated by miR-299a-5p. As seen in Fig. 3q, r, miR-299a-5p inhibition attenuated HG-induced repression of cripto-1. Conversely, miR-299a-5p overexpression reduced basal expression of cripto-1 similarly to HG-mediated reduction (Fig. 3s, t). FST was similarly affected by miR inhibition and overexpression. Together, these results indicate that HG-induced miR-299a-5p expression reduces cripto-1 and FST synthesis.

Cripto-1 inhibits HG-induced profibrotic responses in MC

Cripto-1 is known to antagonize both TGFβ1 and actA signaling17,18. We first confirmed this in MC. Supplementary Fig. 2 shows that Smad3 transcriptional activation by TGFβ1 or actA was inhibited by cripto-1, although ActA inhibition was greater. We next determined whether cripto-1 could prevent HG-induced Smad3 activation. Figure 4a, b shows that the increased Smad3 C-terminal phosphorylation induced by HG (72 hr) was inhibited by cripto-1, as was Smad3 transcriptional activity (Fig. 4c). Figure 4d–f shows that cripto-1 also inhibited HG-induced collagen Iα1 luciferase activation and the increase in expression of fibrotic proteins.

A, B Cripto-1 (1 µg/ml) decreased HG (72 h)-induced Smad3 phosphorylation in MC, as well as C its transcriptional activation assessed using CAGA12-luciferase. D Collagen 1α1 promoter activation by HG (72 h) was inhibited by cripto-1. E, F HG (72 h)-induced matrix protein and CTGF upregulation were inhibited by cripto-1. G HG-induced Smad3 transcriptional activation was inhibited by cripto-1 (1 µg/ml) and FST (500 ng/ml), with a synergistic effect of both together. H Overexpression of miR-299a-5p increased Smad3 transcriptional activity. This was inhibited by cripto-1 and FST, with a synergistic effect seen with both. I MiR-299a-5p overexpression increased collagen 1α1 promoter activation, which was inhibited by cripto-1 or FST alone, and a greater effect seen when used together. J ActA or TGFβ1 inhibition using specific neutralizing antibodies inhibited Smad3 transcriptional activation induced by miR-299a-5p overexpression, similarly to FST. However, actB neutralization had no effect (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). Data presented as mean ± SEM.

Since both FST and cripto-1 are decreased by miR-299a-5p in HG and both inhibit actA, but only cripto-1 inhibits TGFβ1, we tested if their combination would have an additive effect. Figure 4g shows that each individually suppressed HG (72 h)-induced Smad3 transcriptional activity, with a small additive effect. In response to miR-299a-5p overexpression, cripto-1 and FST alone reduced Smad3 reporter activity, with this effect augmented by their combination (Fig. 4h). Similar augmented effects were seen for collagen Iα1 luciferase (Fig. 4i).

Finally, using neutralizing antibodies we explored effects of individual inhibition of TGFβ1 or the two activins primarily neutralized by FST, actA and activin B (actB). Interestingly, neutralization of either actA or TGFβ1, but not actB, inhibited Smad3 transcriptional activation by miR-299a-5p overexpression (Fig. 4j). This suggests that cripto-1 and FST prevent Smad3-dependent fibrotic signaling through their inhibition of actA and TGFβ1 with no significant contribution from actB. Together, these data also suggest that direct inhibition of miR-299a-5p may have greater therapeutic efficacy than use of FST or cripto-1 alone.

miR-299a-5p is increased in caveolin-1 knockout MC

Previously, we showed a reduction in both basal and HG-induced matrix protein expression in MC that lack caveolin-1 and thus caveolae, membrane microdomains which regulate profibrotic signaling25,26. Furthermore, FST was significantly upregulated in MC derived from caveolin-1 knockout (KO) mice9,27, mediated by suppressed miR-299a-5p expression and activity in these cells5. This translated to protection from DKD in caveolin-1 KO mice9. We thus hypothesized that cripto-1 would also be increased in KO MC. To do this, primary mouse MCs were isolated from caveolin-1 wild-type (WT) and caveolin-1 KO B6129SF1/J mice as described previously5. Indeed, Supplementary Fig. 3a, b show that cripto-1 expression was higher in caveolin-1 KO compared to WT cells, and this expression was reduced by miR-299a-5p overexpression (Supplementary Fig. 3c, d). Furthermore, miR-299a-5p inhibition in WT cells increased cripto-1 and FST expression (Supplementary Fig. 3, f). Interestingly, bioinformatics screening showed that another target of miR-299a-5p is the transcription factor SP1, which we previously showed regulates FST promoter activation in MC27. Supplementary Fig. 4 shows that miR-299a-5p overexpression significantly decreased SP1 expression.

miR-299a-5p inhibition improves DKD

We next assessed the therapeutic potential of miR-299a-5p inhibition in DKD. We used Akita mice with genetically increased TGFβ1 expression which was previously shown to exacerbate DKD28. MiR-299a-5p was competitively inhibited from binding to its targets using a Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) anti-miR. Mice were treated for 12 weeks (12–24 weeks of age, Fig. 5a).

A Experimental timeline for miR-299a-5p inhibition studies. Created in BioRender. Nmecha, K. (2025) https://BioRender.com/po97zgk. B, C MiR-299a-5p inhibition restored the reduced cripto-1 and FST protein expression seen in DKD. D, E FST reduction in DKD, seen by IHC, was restored by miR-299a-5p inhibition. F Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was increased in DKD, with miR-299a-5p inhibition having no effect. G Kidney hypertrophy was increased in DKD. This was unaffected by miR-299a-5p inhibition. H The increased albuminuria seen in DKD was attenuated by anti-miR-299a-5p inhibition. I Glomerular volume was increased in DKD, and this was reduced by miR-299a-5p inhibition. J, K The decreased expression of the podocyte marker nephrin in DKD was restored by miR-299a-5p inhibition (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). Data presented as mean ± SEM. The scale bar represents 100 µm.

We first confirmed that miR-299a-5p inhibition could rescue reduced cripto-1 and FST expression in diabetic kidneys. Figure 5b, c shows that both proteins were significantly increased by miR-299a-5p inhibition, confirmed for FST by IHC (Fig. 5d, e). Supplementary Table 6 shows that endpoint fasting blood glucose and weight were not affected by miR-299a-5p inhibition. Blood pressure was measured at enrollment and every 4 weeks (Supplementary Table 7). By study endpoint both systolic and diastolic pressures were increased in diabetic mice, with reduction by miR-299a-5p inhibition. No effect on blood pressure was seen in non-diabetic mice. Diabetic mice showed the expected hyperfiltration (increased GFR) and kidney hypertrophy characteristic of early DKD. These were unaffected by miR-299a-5p inhibition (Fig. 5f, g). However, miR inhibition significantly decreased albuminuria (Fig. 5h) and glomerular hypertrophy (Fig. 5i), two key features of early DKD29. MiR inhibition also significantly rescued loss of nephrin, a marker of podocyte injury which has been correlated with albuminuria in diabetic mice30,31 (Fig. 5j, k).

We next assessed fibrosis. Picrosirius red (PSR) showed the expected increase in collagen I/III expression in diabetic kidneys, which was reduced by miR inhibition (Fig. 6a, b). Similarly, IHC showed that fibronectin, collagen IVα1 and CTGF expression were also decreased by miR-299a-5p inhibition in diabetic mice (Fig. 6a, c–e). This was confirmed by immunoblotting of kidney cortex (Fig. 6f–i). MiR-299a-5p inhibition also reduced activation of Smad3, assessed by its phosphorylation (Fig. 7a, b). Furthermore, the expected increase in actA expression in diabetic kidneys9 was markedly reduced in both glomeruli and tubules by miR-299a-5p inhibition, as shown by IHC (Fig. 7c, d). Urinary actA, significantly elevated in diabetic mice, was also decreased by the inhibitor (Fig. 7e). Similarly, urinary TGFβ1 was reduced by miR inhibition (Fig. 7f). Interestingly, serum miR-299a-5p was increased in diabetic mice, highlighting its potential role as a biomarker for DKD (Fig. 7g). Consistent with the lack of reduction in miR-299a-5p levels by miR inhibition, in vivo we also did not observe a significant decrease in serum miR-299a-5p levels by inhibitor (Supplementary Fig 5). These data support potential therapeutic value of miR-299a-5p inhibition as an antifibrotic agent in DKD through its restoration of cripto-1 and FST, endogenous antagonists of profibrotic TGFβ1 and actA.

A–E Increased fibrosis was seen in DKD, assessed by PSR (A, B) and IHC for fibronectin, collagen IVα1 and CTGF (C–E). All were reduced by miR-299a-5p inhibition. F–I Immunoblotting for fibronectin, collagen 1α1 and CTGF showed similar results (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001). Data presented as mean ± SEM. The scale bar represents 100 µm.

A, B Elevated Smad3 phosphorylation in DKD was reduced by miR-299a-5p inhibition (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). ActA protein expression in the kidney cortex and excretion in the urine was assessed by C, D IHC and E ELISA. Both were increased in DKD and reduced by miR-299a-5p inhibition (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001). F Urinary TGFβ1 was increased in diabetic mice, and this was reduced by miR-299a-5p inhibition (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). G miR-299a-5p expression was increased in the serum of diabetic Akita mice (*p < 0.05). H Schematic diagram of study findings, showing the contribution of actA and TGFβ1 to DKD, and the role of FST and cripto-1 in their inhibition and improvement of DKD as shown by these studies. Image Created in BioRender. Nmecha, K. (2025) https://BioRender.com/vkr4j4g. Data presented as mean ± SEM. The scale bar represents 100 µm.

Discussion

miRs play various regulatory roles in cellular processes of healthy kidneys. However, disease-specific alteration of particular miRs may enable their therapeutic targeting and/or use as diagnostic markers. We identified a novel role for miR-299a-5p in the pathogenesis of fibrosis in DKD. It not only downregulates expression of FST, which inhibits fibrosis through its potent neutralization of activins, but it also downregulates the TGFβ1 antagonist cripto-1. By restoring endogenous FST and cripto-1, miR-299a-5p inhibition ameliorates DKD, as summarized in Fig. 7h.

We previously identified FST as a miR-299a-5p target5. Its greatest efficacy is against actA32, known to be increased in rodent and human DKD9,33. While FST reduced fibrosis and protected against podocyte loss in Akita mice, higher dosing did not increase benefit, and in a non-diabetic model showed reduced efficacy5,34. These data suggested a therapeutic window for FST, possibly related to inhibition of other TGFβ family members. Restoring reduced endogenous FST levels in DKD may thus be a better treatment option. Our identification of increased miR-299a-5p expression in both glomeruli and tubules of mouse and human DKD suggested the potential therapeutic value of targeting miR-299a-5p, supported by our preclinical study. As expected, this was associated with reduced actA in kidneys and urine of diabetic mice.

Given that miRNAs have several targets, we further performed bioinformatics analysis to identify potential additional mechanisms by which miR-299a-5p may contribute to fibrosis. Interestingly, we found that the cripto-1 3’UTR is also a target of miR-299a-5p. Cripto-1 is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked membrane protein essential in human embryonic development and also implicated in tumor progression35. While it functions as a co-receptor for TGFβ family members nodal, growth differentiation factor (GDF)1 and GDF336, it was also shown to block signaling of actA, actB and TGFβ1 itself17,18,37. Through binding these ligands and their type I/II receptors, cripto-1 inhibits ligand-receptor interaction to prevent signaling. Cripto-1 can also be shed from the membrane36, likely further enabling interaction with these cytokines. Indeed, our data showed that recombinant cripto-1 effectively inhibits signaling by actA and TGFβ1 in MC.

Little is known of the role of cripto-1 in the kidney. One study found no significant kidney expression of cripto-1 by immunohistochemistry, but this was in comparison to renal cell carcinoma in which expression may be highly elevated38. We now show that cripto-1 is expressed in normal kidney in both glomeruli and tubules, likely at much lower levels than seen in cancer cells, and that this is attenuated in DKD. In agreement, miR-299a-5p-regulated inhibition of cripto-1 expression by HG was also seen in MC. We confirmed that recombinant cripto-1 reduces signaling by both actA and TGFβ1 and now show that it also attenuates the profibrotic effects of HG. Interestingly, specific neutralization studies suggested that the contribution of actA to these effects was greater than that of actB. Of importance therapeutically, we observed synergy between cripto-1 and FST in attenuating the profibrotic effects of either miR-299a-5p overexpression or of HG. Together, the targeting of both actA and TGFβ1 should theoretically provide more effective inhibition of fibrosis in DKD than inhibition of either ligand separately, although this would need to be demonstrated using target-specific miR blockers.

Previously, we showed that caveolae and their structural membrane protein caveolin-1 are important regulators of FST expression. Caveolin-1 deletion in MC significantly reduced miR-299a-5p, leading to increased expression of FST and reduced expression of fibrotic proteins9. Caveolin-1 knockout in mice also protected against glomerular fibrosis in DKD9. Our data now extend these findings to show the negative regulation of cripto-1 expression by caveolin-1, mediated by miR-299a-5p. The protective effects of cav-1 deletion on DKD can thus likely be attributed to additional antifibrotic effects of cripto-1. Interestingly, Bianco et al. showed that caveolin-1 interaction with cripto-1 in mammary epithelial cells inhibits cripto-1 biologic activity13, suggesting that caveolin-1 can regulate both cripto-1 expression and activity. A negative feedback mechanism was also suggested, with cripto-1 reducing caveolin-1 expression in these cells13. The reduction in cripto-1 seen in diabetic kidneys may thus serve to augment caveolin-1 expression, further reducing FST and cripto-1. Additional studies are needed to test whether this feedback mechanism exists.

Our data support a novel role for miR-299a-5p in DKD. Increased by HG in MC and in diabetic kidneys, its inhibition protects against DKD. Overexpression of miR-299a-5p alone in the absence of HG promotes matrix synthesis, highlighting the important role it plays in the cellular fibrotic response. This is not surprising given its inhibition of at least two potent antifibrotic targets. Further studies are needed to determine whether additional miR-299a-5p targets which could contribute to kidney fibrosis exist. Interestingly, miR-299a-5p was found to suppress Atg5 expression and thereby autophagy in neurons39. As autophagy dysfunction is also found in DKD40, miR-299a-5p may affect multiple pathogenic processes important to disease. Additional miR-154 family members may also contribute to DKD. Increased miR-377 in type 2 diabetic db/db mice and with HG in MC led to increased profibrotic PAI-1 and TGFβ1 expression through PPARγ inhibition41.

Sensitive biomarkers for diagnosis and prediction of DKD progression are needed. Measures of urinary and/or serum miR levels represent a potential non-invasive and affordable means to do this. Several urinary miRNAs (95-3p, 185-5p, 1246, 631) were shown to distinguish various forms of nephropathy in diabetic patients, and two of these reflected DKD severity42. Here we show a significant increase in serum miR-299a-5p in diabetic mice (Fig. 6g), suggesting that its measure could be explored further in patient cohorts to determine its clinical utility in the context of kidney disease progression. Two other miR-154 family members were also found increased in serum in DKD patients. Circulating miR-154-5p correlated with serum TGFβ1 and albuminuria, and inversely correlated with kidney function43, and serum miR-377 was also suggested to be a potential early biomarker of DKD44. Larger studies, however, are needed to confirm these findings.

In conclusion, we identify a novel role for miR-299a-5p in promoting fibrosis in DKD, supporting further assessment of miR-299a-5p inhibition in its treatment. The restoration of endogenous antifibrotic proteins and inhibition of pathologic TGFβ1 signaling in the kidney may be better tolerated than systemic inhibition of these ligands. Indeed, targeting TGFβ1 has proven challenging due to its homeostatic role45,46. Further work should also address some limitations of this study. Given that miRs are not specific for single targets, confirmation that beneficial effects of miR-299a-5p targeting occur via increased cripto-1 and FST expression could be ascertained using specific target site blockers to restrict effects to each of these RNAs. This study focused on MC, but miR-299a-5p expression was also seen in the tubular epithelium. Future studies will address the question of how this miR may contribute to tubular injury or interstitial fibrosis in DKD.

Methods

Cell culture

Primary MC were grown from glomeruli of male C57BL/6J mice isolated using Dynabeads (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as described previously5. MC were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS), streptomycin (100 µg/ml) and penicillin (100 µg/ml) at 37 °C in 95% O2, 5% CO2. Cells were serum deprived in DMEM with 0.5% FBS for 24 h following transfection and prior to treatment with high glucose (30 mM) for 72 h, drugs or recombinant proteins (Supplementary Table 1). Passage 9–16 MCs were used for experiments.

mRNA and miRNA extraction and qPCR

RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and 1 µg was reverse transcribed using qScript cDNA SuperMix Reagent (Quanta Biosciences). miRNA-enriched cDNA was generated using the qScript microRNA Quantification System (Quanta Biosciences). Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using a SYBR Green PCR Master Mix kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) on the ViiA 7 Sequence Detector (Life Technologies). Amplification of cripto-1 or miRNA expression, relative to 18S or U6 respectively, was measured using the ΔΔCT method. Primers are listed in Supplementary Table 2. miRNeasy serum advanced kit (Qiagen) was used to extract RNA from the serum of diabetic mice after which miRNA-enriched cDNA was generated as above.

miRNA in-situ hybridization (ISH)

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded kidney sections (4 µm) were deparaffinized, dehydrated, and treated with proteinase K. After incubation in hybridization buffer, sections were incubated with DIG-labeled miRCURY LNA anti-miR detection probes (Supplementary Table 3) targeting miR-299a or U6 (18 h). After further washes47, sections were blocked in 1×Casein Solution (Vector labs) and incubated with anti-digoxigenin-AP Fab fragment. Chromogenic reaction was carried out using NBT/BCIP (Vector Labs). Slides were then mounted with Vectamount (Vector labs). Images were taken at 40× using a BX41 Olympus microscope and quantified using ImageJ.

For human studies, kidney biopsy samples with a diagnosis of DKD were obtained. Normal kidney tissues surrounding resected renal cancers were used as controls (Research Ethics Board approval number 2010-159).

Transient transfections

For luciferase experiments, MC were plated in triplicate at 60–70% confluence and transfected with 0.5 µg of luciferase construct (pGL3-CAGA12-luc or pGL3-COL1α1-luc) with 0.05 µg pCMV β-galactosidase (Clontech) using Effectene (Qiagen). At harvest, MC were lysed with 1X Reporter Lysis Buffer (Promega, Madison, WI) and frozen at −80 °C overnight. Luciferase and β-gal activities were measured on clarified lysate using specific kits (Promega) with a Spectramax Plus 384 plate reader set to luminescence and 420 nm, respectively. β-gal activity was used to adjust for transfection efficiency.

miR299a-5p regulatory element (MRE) luciferase was generated in order to measure miR299a-5p activity as previously described5, and MCs were transfected as above.

For transient expression, MC resuspended in electroporation buffer containing 10 μg expression plasmid were electroporated using a single square pulse set at 200 V for 35 ms (ECM830, Harvard Bioscience). After 18 h, media was exchanged. To assess transfection efficiency of miR plasmids (Supplementary Table 4), mCherry (ex 550 nm/em 620 nm) and GFP (ex 490 nm/em 525 nm) immunofluorescence were confirmed by imaging (EVOS FL Cell Imaging System, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Luciferase constructs and pCMV β-galactosidase were transfected 4 h later in some experiments.

Protein extraction and immunoblotting

MC were washed 3× with cold phosphate buffered saline and lysed in buffer with protease inhibitors (10 µg/ml PMSF, 2 µg/ml leupeptin, 2 µg/ml aprotinin). After clarification, proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting. Antibodies used are listed in Supplementary Table 5.

Animal studies

Animal studies were approved by the McMaster University Animal Research Ethics Board and carried out in accordance with the Canadian Council on Animal Care guidelines and ARRIVE guidelines and checklist. Animals were housed under standard conditions with free access to chow and water. Two animal models were assessed by IHC and ISH: (1) Male type 1 diabetic Akita (C57BL/6-Ins2Akita/J) or wild-type mice (C57BL/6J) (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) at age 40 weeks (ethics #18-07-30). (2) Uninephrectomized male CD1 mice aged 9 weeks were injected with 200 µg streptozotocin and euthanized after 12 weeks of diabetes as described previously24,48 (#14-11-48).

C57BL/6-Ins2HH Akita mice expressing hypermorphic (gain in function) alleles for TGFβ1 (denoted HH-A), resulting in ~300% increase in transcript expression, were described previously28. Controls were non-diabetic HH mice. Male mice were enrolled at age 12 weeks, randomly assigned and treated with 2 mg/kg of miR-LNA inhibitor (LNAi) or negative control “B” (LNAc, Qiagen) intraperitoneally once weekly for 12 weeks. There were four groups: HH-LNAc (n = 8), HH-LNAi (n = 8), HH-A-LNAc (n = 12) and HH-A-LNAi (n = 12). Mice with glucometer measure of tail vein blood glucose >17 mM were enrolled as diabetics. Those that developed ketonuria (dipstick, Bayer Multistix) or progressive weight loss were administered ¼ insulin pellet (LinShin Canada) to maintain body weight while also maintaining hyperglycemia. Blood pressure was measured in the morning, at 4, 8, and 12 weeks using tail-cuff plethysmography (Coda non-invasive blood pressure monitoring system, Kent Scientific). We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use.

After 12 weeks, urine was collected (6 h, Nalgene metabolic cage 650-0210). Urine albumin and creatinine were measured using Albuwell M (Exocell) and Mouse Creatinine Assay kits (Crystal Chem) respectively to determine the albumin to creatinine ratio (ACR). Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was measured using fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled sinistrin (Fresenius Kabi Linz) as previously described9. Mice were then anesthetized, perfused with saline and kidneys harvested for analysis.

ELISA kits (R&D Systems) were used to measure total TGFβ1 or actA in urine, normalized to urine creatinine. TGFβ1 samples underwent acid activation.

Imaging

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded kidney sections (4 µm) were deparaffinized and stained using Trichrome (Sigma), PAS or Picrosirius red (PSR) (Polysciences Inc.) or using antibodies (Supplementary Table 5). Images were captured using the Olympus BX41 microscope at 20× (or Olympus IX81 fluorescence microscope for PSR) and quantified as percentage of positive area using ImageJ. 20–30 images per mouse which included at least 2 glomeruli per image were used for quantification. Glomerular hypertrophy was assessed by glomerular cross-sectional area measures on Periodic acid-Schiff-stained sections as described previously8.

For immunofluorescence, 10 μm OCT-embedded frozen kidney sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde prior to blocking and nephrin antibody incubation. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Images were taken at 40× for quantification.

Statistical analysis and reproducibility

GraphPad Prism 10 was used to analyze differences between groups using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc testing, or two-tail unpaired t test. Repeated measures two-way ANOVA was used to analyze blood pressure. Statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0.05, with data presented as mean ± SEM. Sample size for in vitro experiments is n = 7–16, while in vivo experiments n = 4–16.

Data availability

This study does not involve large data sets, new software or custom codes. The original data obtained and presented in this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Uncropped/unedited gels/blots are available in the Supplementary Information file and numerical source data for the graphs are provided in Supplementary data.

References

Kato, M. & Natarajan, R. Epigenetics and epigenomics in diabetic kidney disease and metabolic memory. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 15, 327 (2019).

Varghese, R. T. & Jialal, I. Diabetic nephropathy. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534200/ (2023).

Gewin, L. S. TGF-β and diabetic nephropathy: lessons learned over the past 20 years. Am. J. Med. Sci. 359, 70–72 (2020).

Wang, L., Wang, H. L., Liu, T. T. & Lan, H. Y. TGF-beta as a master regulator of diabetic nephropathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 7881 (2021).

Mehta, N. et al. miR-299a-5p promotes renal fibrosis by suppressing the antifibrotic actions of follistatin. Sci Rep. 11, https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-020-80199-Z (2021).

Mehta, N. & Krepinsky, J. C. The emerging role of activins in renal disease. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 29, 136–144 (2020).

Tsai, M.-T., Ou, S.-M., Lee, K.-H., Lin, C.-C. & Li, S. Circulating activin A, kidney fibrosis, and adverse events. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 19, 169–177 (2023).

Sun, Y. et al. Tubule-derived INHBB promotes interstitial fibroblast activation and renal fibrosis. J. Pathol. 256, 25–37 (2022).

Zhang, D. et al. The caveolin-1 regulated protein follistatin protects against diabetic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 96, 1134–1149 (2019).

Formosa, A. et al. MicroRNAs, miR-154, miR-299-5p, miR-376a, miR-376c, miR-377, miR-381, miR-487b, miR-485-3p, miR-495 and miR-654-3p, mapped to the 14q32.31 locus, regulate proliferation, apoptosis, migration and invasion in metastatic prostate cancer cells. Oncogene 33, 5173–5182 (2013).

Milosevic, J. et al. Profibrotic role of miR-154 in pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 47, 879–887 (2012).

Sun, L. Y. et al. MiR-154 directly suppresses DKK2 to activate Wnt signaling pathway and enhance activation of cardiac fibroblasts. Cell Biol. Int. 40, 1271–1279 (2016).

Bianco, C. et al. Regulation of Cripto-1 signaling and biological activity by Caveolin-1 in mammary epithelial cells. Am. J. Pathol. 172, 345 (2008).

Bernardo, B. et al. Inhibition of miR-154 protects against cardiac dysfunction and fibrosis in a mouse model of pressure overload. Sci. Rep. 6, 22442 (2016).

Padgett, K. A. et al. Primary biliary cirrhosis is associated with altered hepatic microRNA expression. J. Autoimmun. 32, 246–253 (2009).

Iemura, S. I. et al. Direct binding of follistatin to a complex of bone-morphogenetic protein and its receptor inhibits ventral and epidermal cell fates in early Xenopus embryo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 9337–9342 (1998).

Gray, P. C., Shani, G., Aung, K., Kelber, J. & Vale, W. Cripto binds transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) and inhibits TGF-β signaling. Mol. Cell Biol. 26, 9268 (2006).

Gray, P. C., Harrison, C. A. & Vale, W. Cripto forms a complex with activin and type II activin receptors and can block activin signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 5193 (2003).

Stenvang, J. et al. Inhibition of microRNA function by antimiR oligonucleotides. Silence 3, 22230293 (2012).

Riley, W. J., McConnell, T. J., Maclaren, N. K., McLaughlin, J. V. & Taylor, G. The diabetogenic effects of streptozotocin in mice are prolonged and inversely related to age. Diabetes 1 30, 718–723 (1981).

Kitada, M., Ogura, Y. & Koya, D. Rodent models of diabetic nephropathy: their utility and limitations. Int. J. Nephrol. Renovasc. Dis. 9, 279–290 (2016).

Zhu, Q. J., Zhu, M., Xu, X. X., Meng, X. M. & Wu, Y. G. Exosomes from high glucose-treated macrophages activate glomerular mesangial cells via TGF-β1/Smad3 pathway in vivo and in vitro. FASEB J. 33, 9279–9290 (2019).

Soomro, A. et al. A therapeutic target for CKD: activin A facilitates TGFβ1 profibrotic signaling. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 28, 10 (2023).

Trink, J. et al. Both sexes develop DKD in the CD1 uninephrectomized streptozotocin mouse model. Sci. Rep. 13, https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-023-42670-5 (2023).

Peng, F. et al. TGFβ-induced RhoA activation and fibronectin production in mesangial cells require caveolae. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 295, F153 (2008).

Guan, T. H. et al. Caveolin-1 deficiency protects against mesangial matrix expansion in a mouse model of type 1 diabetic nephropathy. Diabetologia 56, 2068–2077 (2013).

Mehta, N. et al. Caveolin-1 regulation of Sp1 controls production of the antifibrotic protein follistatin in kidney mesangial cells. Cell Commun. Sign. 17, https://doi.org/10.1186/S12964-019-0351-5 (2019).

Hathaway, C. K. et al. Low TGFβ1 expression prevents and high expression exacerbates diabetic nephropathy in mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 5815–5820 (2015).

Kolset, S. O., Reinholt, F. P. & Jenssen, T. Diabetic Nephropathy and Extracellular Matrix. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 60, 976 (2012).

Kandasamy, Y., Smith, R., Lumbers, E. R. & Rudd, D. Nephrin - a biomarker of early glomerular injury. Biomark Res. 2, https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-7771-2-21 (2014).

Welsh, G. I. & Saleem, M. A. Nephrin - Signature molecule of the glomerular podocyte?. J. Pathol. 220, 328–337 (2010).

Thompson, T. B., Lerch, T. F., Cook, R. W., Woodruff, T. K. & Jardetzky, T. S. The structure of the follistatin:activin complex reveals antagonism of both type I and type II receptor binding. Dev. Cell 9, 535–543 (2005).

Bian, X. et al. Senescence marker activin A is increased in human diabetic kidney disease: association with kidney function and potential implications for therapy. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 7, 720 (2019).

Mehta, N., Gava, A.L., Zhang, D., Gao, B. & Krepinsky, J. C. Follistatin protects against glomerular mesangial cell apoptosis and oxidative stress to ameliorate chronic kidney disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 31, 551–571 (2019).

Sousa, E. R. et al. A multidisciplinary review of the roles of cripto in the scientific literature through a bibliometric analysis of its biological roles. Cancers 12, 1480 (2020).

Gray, P. C. & Vale, W. Cripto/GRP78 modulation of the TGF-β pathway in development and oncogenesis. FEBS Lett. 586, 1836 (2012).

Shukla, A., Ho, Y., Liu, X., Ryscavage, A. & Glick, A. B. Cripto-1 alters keratinocyte differentiation via blockade of transforming growth factor-beta1 signaling: role in skin carcinogenesis. Mol. Cancer Res. 6, 509–516 (2008).

Xue, Y. J. et al. Cripto-1 expression in patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma is associated with poor disease outcome. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 38, https://doi.org/10.1186/S13046-019-1386-6 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. MiR-299-5p regulates apoptosis through autophagy in neurons and ameliorates cognitive capacity in APPswe/PS1dE9 mice. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–14 (2016).

Gonzalez, C. D., Carro Negueruela, M. P., Santamarina, C. N., Resnik, R. & Vaccaro, M. I. Autophagy dysregulation in diabetic kidney disease: from pathophysiology to pharmacological interventions. Cells 10, https://doi.org/10.3390/CELLS10092497 (2021).

Duan, L. J. et al. Long noncoding RNA TUG1 alleviates extracellular matrix accumulation via mediating microRNA-377 targeting of PPARγ in diabetic nephropathy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 484, 598–604 (2017).

Han Q., et al. Urinary sediment microRNAs can be used as potential noninvasive biomarkers for diagnosis, reflecting the severity and prognosis of diabetic nephropathy. Nutr. Diabetes. 11, https://doi.org/10.1038/S41387-021-00166-Z (2021).

Ren, H. et al. Correlation between serum miR-154-5p and urinary albumin excretion rates in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional cohort study. Front. Med. 14, 642–650 (2020).

Xing, C. et al. The predictive value of miR-377 and phospholipase A2 in the early diagnosis of diabetic kidney disease and their relationship with inflammatory factors. Immunobiology 229, 152792 (2024).

Kulkarni, A. B. et al. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 null mice. An animal model for inflammatory disorders. Am. J. Pathol. 146, 264 (2024).

Voelker, J. et al. Anti-TGF-b1 antibody therapy in patients with diabetic nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 28, 953–962 (2017).

Kriegel, A. J. & Liang, M. MicroRNA in situ hybridization for formalin fixed kidney tissues. J. Vis. Exp. 81, 50785 (2013).

Van Krieken, R. et al. Inhibition of SREBP with fatostatin does not attenuate early diabetic nephropathy in male mice. Endocrinology 159, 1479–1495 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors recognize the support of The Research Institute at St. Joe’s Hamilton for nephrology research. J.C.K. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (JCK, PJT-148628). I.K.N. is a recipient of an Ontario Graduate Scholarship award and the 2023 Canadian Graduate Student (CIHR) award (189316).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.K.N., B.G., M.M., D.Z., U.B. and J.C. performed experiments; I.K.N. and J.C.K. conceived experimental design; I.K.N., D.Z. and J.T. analyzed the data; I.K.N. and J.C.K. wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Roel Bijkerk and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Kaliya Georgieva. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nmecha, I.K., Gao, B., MacDonald, M. et al. miR-299a-5p is a mediator of fibrosis in diabetic kidney disease by regulating follistatin and cripto-1. Commun Biol 9, 15 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09271-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09271-6