Abstract

The neonatal period is critical for brain development, yet the mechanisms linking structural differentiation to functional reorganization remain poorly understood. Using multi-modal MRI data from 399 neonates (348 term-born, 51 preterm-born), here we characterize the dynamic structure-function coupling (SFC) across macroscale brain networks and examine its associations with cortical microstructure (indexed by the T1w/T2w ratio) and network flexibility. We show that the dynamic SFC varies markedly across the neocortex and increases with postmenstrual age, particularly within the default mode network (DMN). Notably, the dynamic SFC in the posterior DMN mediates the relationship between the T1w/T2w ratio and network flexibility. Preterm infants exhibit a significantly reduced dynamic SFC relative to term-born peers, along with an altered developmental trajectory of DMN linked to premature extra-uterine exposure. These findings establish dynamic SFC, especially within the DMN, as a potential biomarker for neonatal brain maturation, offering insight into the early emergence of internally directed cognition and its vulnerability to early-life adversity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The neonatal period is a critical phase of brain development, characterized by rapid maturation of anatomical architecture and extensive reorganization of functional networks1,2. Advances in neuroimaging have greatly expanded our understanding of the development of the brain connectome in early life3,4,5,6. Specifically, diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) has revealed the heterogeneous maturation of white matter tracts, with substantial progress observed in key pathways such as the corpus callosum and the corticospinal tracts from late gestation to early infancy7,8. Concurrently, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has shown the presence of a hierarchical organization of functional networks at birth, in which primary systems mature earlier and more robustly than higher-order systems like the default mode and executive control networks9,10. These developmental trajectories align with the established ‘bottom-up’ and ‘posterior-to-anterior’ hypothesis, wherein early maturation of primary cortices lays a groundwork for the subsequent development of higher-order cortices11,12,13. Despite these insights, previous studies have mainly focused on either structural or functional connectome patterns alone. How the structural maturation of the neonatal brain drives its functional reorganization remains largely unexplored. Revealing the precise relationship between these two elements is crucial for elucidating the mechanisms underlying early typical and atypical brain development.

The white matter architecture of the brain constrains and facilitates synchronization among neuronal clusters, giving rise to a rich repertoire of complex functional activities14,15. Structure-function coupling (SFC) refers to the statistical correspondence between structural and functional connectomes, offering a simplified framework to examine how the anatomical wiring of the brain shapes its functional communication16,17. In adults, SFC is typically stronger in unimodal cortices and weaker in transmodal cortices, reflecting a fundamental principle of brain organization18,19. SFC variations are linked to individual differences in cognitive performance across multiple domains, including working memory, inhibitory control, and mental flexibility20,21,22. More importantly, SFC is not static but fluctuates over time. Dynamic SFC measures the time-varying interplay between structural and functional connectomes, offering novel insights beyond static models by capturing subtle temporal variations23. Previous studies in adults have demonstrated that dynamic SFC mediates the balance between functional segregation and integration, and exhibits an increase in temporal variability along the cortical hierarchy—from unimodal to transmodal cortices—with higher-order association areas exhibiting greater fluctuations over time24,25. In our previous work, we identified that aberrant dynamic SFC patterns are associated with clinical symptoms in neuropsychiatric conditions, highlighting the potential of dynamic SFC as a sensitive marker for atypical neurodevelopment26,27. However, how SFC varies dynamically across time in the neonatal brain is poorly understood. Moreover, the underlying biological mechanisms of dynamic SFC during this critical period of development, and its potential influence on the emergence of cognitive functions as well, require further investigation.

Recent evidence suggests that myelination is a key biological substrate influencing the variable expression of SFC across the cortical hierarchy28. Brain regions with higher myelination (indexed by the T1w/T2w ratio), such as primary sensory cortices, tend to exhibit more stable patterns of temporal SFC variance due to stronger structural constraints. In contrast, brain regions with lower myelination, such as transmodal cortices, display greater variability throughout the entire scan duration25. However, because intracortical myelination is largely absent at birth, the neonatal cortical T1w/T2w signal ratio is considered a microstructural proxy sensitive to pre-myelination processes (e.g., oligodendrocyte lineage proliferation, glial density)29,30. Consistent with developmental gradients, this proxy exhibits a well-documented primary-to-transmodal pattern, providing a structural antecedent that shapes the spatial distribution of dynamic SFC at birth. Furthermore, dynamic SFC has been linked to flexible cognition, and higher network flexibility is believed to support improved cognitive performance31,32. In neonates, a recent fMRI study demonstrated that six transient connectivity states are already present at birth; importantly, the occupancy, dwell times, and transition structure of these states—indices of short-timescale network flexibility—are altered in preterm infants and prospectively associated with early-childhood neurodevelopmental outcomes5. Accordingly, within a developmentally motivated statistical framework, we hypothesize that regional variation in pre-myelination microstructure (T1w/T2w ratio) is associated with tighter alignment of functional co-fluctuations to the structural scaffold (i.e., higher, more stable dynamic SFC), which in turn is associated with a narrower repertoire of short-timescale community states (i.e., lower network flexibility).

In this study, we investigated the dynamic SFC pattern and its associations with cortical microstructural maturation and network flexibility in the neonatal brain. We utilized a large cohort comprising 399 infants (348 term-born and 51 preterm-born) from the Developing Human Connectome Project (dHCP). These infants underwent multimodal MRI scans at term-equivalent age, ranging from 37 to 44 weeks postmenstrual age (PMA). We developed a novel quantitative framework to examine dynamic SFC in macroscale brain networks, capturing the moment-to-moment interplay between structural differentiation and functional reorganization across the neocortex. The basic flow of studying dynamic SFC is depicted in Fig. 1. We further conducted mediation analyses to explore how dynamic SFC influences the relationship between the T1w/T2w ratio and the flexible reconfiguration of functional networks. Finally, we compared dynamic SFC patterns between term-born and preterm-born infants to elucidate the potential impact of prematurity on the early development of the brain.

Four major steps were included: a use multimodal parcellation template with 210 cortical parcels and categorized these parcels into 5 resting-state networks (RSNs), including the sensorimotor network (SMN), visual network (VN), high-level visual network (HVN), ventral attention network (VAN), and default mode network (DMN); b construct dynamic functional network connectivity with sliding window approach; c construct structural network connectivity and compute the corresponding Euclidean distance (euc), path length (pl), and communicability (comm) networks; and d estimate dynamic structure-function coupling (SFC) with a multilinear regression model and Pearson’s correlation analysis.

Results

Dynamic SFC pattern in term-born infants

We found that the group-averaged dynamic SFC pattern in term-born infants was characterized by stronger SFC co-fluctuations (i.e., more robust connections) within each resting-state network (RSN), and weaker SFC co-fluctuations (i.e., sparse connections) between RSNs (Fig. 2a). We also observed considerable variation in regional mean dynamic SFC across the neocortex, with the visual and default mode regions displaying notably high levels of co-fluctuation (Fig. 2b). The visual network (VN) exhibited the highest intra-network dynamic SFC (F(4, 1388) = 1211.5, P < 0.001, Kendall’s W = 0.49, Friedman ANOVA) and the strongest inter-network dynamic SFC with other RSNs (F(4, 1388) = 228.7, P < 0.001, Kendall’s W = 0.16, Friedman ANOVA) at the subnetwork level (Fig. 2c, d). It is noted that a positive association between PMA and intra-network dynamic SFC was identified within the default mode network (DMN) (r = 0.13, P = 0.017, FDR-corrected; Fig. 2e). As the brain matured during early development (37–44 weeks), increases in PMA were linked to more stable and mature SFC co-fluctuations within the DMN (Supplementary Fig. 1). We next asked whether dynamic SFC carries a generalizable age signal. Using the connectome-based predictive modeling (CPM) framework, we found a strong correlation between predicted and actual ages (r = 0.27, P < 0.001; Fig. 2f, g). The most significant dynamic SFC features for PMA prediction are highlighted in Fig. 2h. We observed that DMN-centered features are among the most important contributors to the predictive signal. These results remained consistent across varying lengths of sliding window and increment steps (Supplementary Figs. 2–5). Additionally, we calculated the conventional static SFC, but no meaningful associations with PMA were detected (Supplementary Fig. 6). These findings underscore the sensitivity and effectiveness of dynamic SFC in detecting early stages of brain development and organization in newborns, which are less discernible with traditional static SFC measures.

a Group averaged dynamic SFC matrix in term-born infants. b Regional dynamic SFC maps, which vary markedly across the neocortex. c Subnetwork-level dynamic SFC. d Violin plots showing intra-network dynamic SFC of each RSN. e Scatter plot showing the relevance between postmenstrual age and intra-network dynamic SFC of the RSNs. f Scatter plot depicting the correlation between the actual and predicted postmenstrual ages. g Statistical significance via permutation tests. h Circle plot visualization of the most prominent positive and negative dynamic SFC features (left) and RSN-by-RSN aggregation across the full Connectome-based Prediction Model (CPM)-selected feature set (right). f–h illustrate postmenstrual age prediction using the dynamic SFC features and CPM models. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Relationships among dynamic SFC, T1w/T2w, and network flexibility in term-born infants

To identify the structural substrates underlying dynamic SFC, we assessed T1w/T2w ratio mapping, a key indicator for microstructural maturation. The regional cortical T1w/T2w ratio maps revealed high levels of intensity in sensorimotor, calcarine, and posterior superior temporal regions (Fig. 3a). At the subnetwork level, intra-network cortical T1w/T2w ratio exhibited a hierarchical organization, spanning from unimodal to transmodal cortices (F(4, 1388) = 1234.9, P < 0.001, Kendall’s W = 0.89, Friedman ANOVA; Fig. 3b). No significant correlation was found between cortical T1w/T2w ratio and dynamic SFC across the whole neocortex (P > 0.05; Fig. 3c). Moreover, we observed positive correlations between intra-network cortical T1w/T2w ratio and dynamic SFC within the SMN (r = 0.11, P = 0.047, FDR-corrected), VN (r = 0.12, P = 0.030, FDR-corrected), VAN (r = 0.12, P = 0.024, FDR-corrected), and DMN (r = 0.14, P = 0.008, FDR-corrected; Fig. 3d), indicating that the matured microstructure within these networks supports stronger SFC co-fluctuations during early brain development. Additionally, we found intra-network T1w/T2w ratio showed a significant increase with PMA (all P < 0.001, FDR-corrected; Fig. 3e)

a Regional T1w/T2w ratio maps, which vary markedly across the neocortex. b Violin plots showing the intra-network T1w/T2w ratio of each RSN. c Scatter plot showing the correlation between mean regional T1w/T2w ratio and the dynamic SFC of all term-born infants across the neocortex. d Scatter plot showing the relevance between intra-network T1w/T2w ratio and intra-network dynamic SFC of the RSNs. e Scatter plot showing the relevance between postmenstrual age and intra-network T1w/T2w ratio of the RSNs. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

We also explored the relationship between dynamic SFC and network flexibility, a metric reflecting the capacity for large-scale brain network reconfiguration. Group-averaged network flexibility was calculated for each brain region and correlated with dynamic SFC. Network flexibility varied considerably across the neocortex, with higher flexibility in attention-related regions and lower flexibility in sensorimotor regions (Fig. 4a). In contrast to the hierarchical gradient observed in T1w/T2w, intra-network flexibility showed a decreasing gradient from the VN to the sensorimotor network (SMN) (F(4, 1388) = 278.6, P < 0.001, Kendall’s W = 0.20, Friedman ANOVA; Fig. 4b). We observed a negative correlation between dynamic SFC and network flexibility across the whole neocortex (r = −0.20, P = 0.003, FDR-corrected; Fig. 4c), indicating that regions with stronger dynamic SFC tend to have lower flexibility. Notably, dynamic SFC was negatively correlated with flexibility within each RSN (all P < 0.05, FDR-corrected; Fig. 4d), suggesting that higher dynamic SFC may be associated with more stable, rather than flexible, configurations. We further found that network flexibility within the SMN (r = 0.13, P = 0.020, FDR-corrected) and VN (r = 0.16, P = 0.005, FDR-corrected) increased with PMA (Fig. 4e).

a Regional network flexibility maps, which vary markedly across the neocortex. b Violin plots showing the intra-network flexibility of each RSN. c Scatter plot showing the correlation between mean regional flexibility and dynamic SFC of all term-born infants across the neocortex. d Scatter plot showing the relevance between intra-network flexibility and intra-network dynamic SFC of the RSNs. e Scatter plot showing the relevance between postmenstrual age and intra-network flexibility of the RSNs. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

To better understand the relationship between cortical microstructure, dynamic SFC, and network flexibility, we performed a mediation analysis for each RSN. We tested whether dynamic SFC mediated the effect of T1w/T2w ratio on network flexibility in term-born infants. We revealed that the direct effect was not statistically significant in any RSN. However, in the DMN, we observed a significant indirect effect whereby a higher T1w/T2w ratio reduced flexibility via increased dynamic SFC (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 7). Specifically, cortical T1w/T2w ratio was positively associated with dynamic SFC (a path), which, in turn, was negatively associated with network flexibility (b path). The indirect effect (ab path) of T1w/T2w ratio on network flexibility through dynamic SFC was significant (β = −0.03, P = 0.007, CI: [−0.054, −0.007], bootstrap). More importantly, we found that this mediation effect was only significant within the posterior but not the anterior part of the DMN (β = −0.02, P = 0.030, CI: [−0.052, −0.002], bootstrap), indicating that dynamic SFC within the posterior DMN plays a mediating role in the relationship between microstructural maturation and network flexibility. We further performed mediation analysis with static SFC as the mediator and found no significant indirect effects across all RSNs (all P > 0.05; Supplementary Fig. 8).

a The anterior and posterior areas of the default mode network (DMN). b Mediation analysis in the DMN. c Mediation analysis in the anterior DMN. d Mediation analysis in the posterior DMN. T1w/T2w ratio was set as an independent variable, while the network flexibility was a dependent variable, and the dynamic SFC was the mediated variable. Mediation results are reported as standardized regression coefficients, and statistical significance was assessed using 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals. Standard errors are provided in parentheses. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Dynamic SFC pattern in preterm-born infants

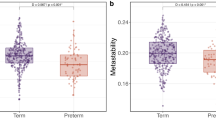

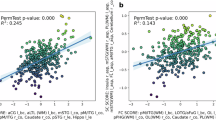

We addressed the dynamic SFC pattern of preterm-born infants and compared the dynamic SFC pattern with that of term-born infants to identify the potential effects of prematurity on brain organization. Given the unbalanced sample sizes of infants (51 for preterm-born versus 348 for term-born), we created a matched subset of term-born infants (n = 51) with similar PMA to the preterm-born group (40.92 ± 1.87 vs. 40.90 ± 1.91 weeks; t = 0.06, P > 0.95; Fig. 6a). Specifically, for each preterm infant, a term-born infant with the closest PMA at scan was selected from the larger cohort using a one-to-one nearest-neighbor matching algorithm without replacement, resulting in a subset that was well-matched for age. While the term-born infants had a significantly higher gestational age (GA) at birth (39.96 ± 1.40 vs. 31.98 ± 3.32 weeks, P < 0.001), they had a much shorter postnatal time (PT) relative to the preterm-born infants (0.96 ± 1.13 vs. 8.91 ± 4.42 weeks, P < 0.001). Significant differences in dynamic SFC were detected between the two groups (Fig. 6b). At sub-network level, the preterm-born infants exhibited a lower dynamic SFC within the ventral attention network (VAN) and DMN, as well as between SMN and VAN (all P < 0.05; Fig. 6c). We also examined the relationship between the dynamic SFC and PMA within each group. Consistent with the findings from the full group of term-born infants, the dynamic SFC within the DMN was also significantly positively correlated with PMA (r = 0.30, P = 0.032) in the subset of term-born infants. However, such association was not seen in the preterm-born infants (r = −0.01, P = 0.932; Fig. 6d), implying that prolonged time spent ex utero may negatively affect the development of SFC co-fluctuations in this network. Finally, we performed the mediation analysis to the preterm cohort and to the subset of term-born infants. Neither analysis yielded a significant indirect effect of T1w/T2w on network flexibility via dynamic SFC in the DMN (matched term: ab β = 0.05, P = 0.266, CI: [−0.162, 0.039], bootstrap; preterm: ab β = 0.01, P = 0.958, CI: [−0.052, 0.060], bootstrap; Supplementary Fig. 9).

a Bar plots showing age differences between term- and preterm-born infants. b Group differences in dynamic SFC matrix. c Group differences in subnetwork-level dynamic SFC. d Scatter plot showing the relevance between postmenstrual age (PMA) and dynamic SFC of the DMN for term- and preterm-born infants. GA gestational age, PT postnatal time. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

In this study, we systematically characterized dynamic SFC across macroscale brain networks in a large neonatal cohort from the dHCP. By integrating multimodal neuroimaging measures, we developed a robust quantitative framework capturing intricate moment-to-moment interactions between structural maturation and functional reorganization. We further explored how cortical microstructure relates to network flexibility via dynamic SFC. Our findings offer a novel insight into the intricate structural-functional interplay underlying early brain maturation, particularly highlighting the pivotal role of the DMN.

We observed marked spatial variability in dynamic SFC across cortical regions, with primary sensory networks, particularly the VN, exhibiting the highest dynamic coupling. In contrast, static SFC recapitulated the canonical unimodal-to-transmodal gradient (SMN highest, DMN lowest), consistent with baseline (tonic) structural tethering in early-maturing sensorimotor systems33. These metrics are therefore complementary rather than interchangeable: static SFC reflects hierarchical wiring priorities, whereas dynamic SFC indexes the propensity for transient, moment-to-moment alignment with anatomy in early life5,34. The prominence of the VN in the dynamic regime aligns with previous evidence indicating a rapid and pronounced maturation of primary sensory cortices relative to higher-order association regions during early infancy2,35. Early sensory experiences significantly shape structural and functional brain networks, as sensory pathways rapidly mature due to frequent and intense environmental stimulation immediately post-birth36. Particularly, the VN undergoes rapid structural and functional maturation driven by visual inputs that are consistently available shortly after birth37. These sensory-driven experiences facilitate synaptic strengthening and pruning processes, optimizing neural pathways for efficient signal processing and communicating38. Therefore, the robust co-fluctuation of SFC observed within the VN likely reflects structural constraints optimized for the rapid and efficient processing of visual stimuli. Importantly, we found a significant positive correlation between PMA and dynamic SFC within the DMN, highlighting the surprising emergence and maturation of higher-order cognitive networks during early infancy39.

Cognitive networks such as the DMN are considered to undergo maturation relatively later than primary sensory and motor networks40,41,42. Our findings challenge this traditional view by suggesting that dynamic structural-functional interplay supporting higher-order cognitive functions begins forming much earlier. And these early foundational architectures may play a critical role in supporting internal mentation and cognitive integration, setting the groundwork for future complex cognitive and socio-emotional development43,44. Indeed, accumulating data suggest that the DMN has a significant structural and functional integration even at very early stages of development, which facilitates crucial sensory and cognitive integration for complex tasks and social cognition5,45. Additionally, this positive correlation was uniquely identified using our dynamic SFC approach rather than typical static analysis, demonstrating its sensitivity in capturing subtle progressions of neurodevelopment23. Moreover, the ability of dynamic SFC features to accurately predict PMA further emphasizes their potential as robust biomarkers for assessing early neurodevelopment.

Our investigation revealed that dynamic SFC within the SMN, VN, VAN, and DMN was positively associated with the T1w/T2w ratio. This suggests that cortical microstructural maturation may enhance the efficiency of neural information transmission and support more stable and coherent functional activity within cognitive networks46. Higher T1w/T2w likely indexes greater microstructural maturity, which can increase conduction reliability and temporal precision, thereby tightening short-timescale alignment of functional co-fluctuations to the structural scaffold—observed here as stronger dynamic SFC47,48. Consequently, our findings suggest that premyelination-driven enhancement in microstructural integrity substantially supports stable and robust functional configurations that underlie separated cognitive processing in neonates49. Notably, our findings—higher T1w/T2w associated with greater dynamic SFC in transmodal networks—contrast with previous studies in adults linking myelination to reduced SFC variability. We propose that, in early life, increasing microstructural maturity enables coherent yet adaptable SFC co-fluctuations. With continued development, stronger structural constraints progressively stabilize interactions, producing the lower variability observed later23,25,50. Accordingly, the direction of cortical microstructure–dynamic SFC associations is likely phase-dependent across development. Therefore, multimodal and longitudinal data are needed to determine whether this association persists, attenuates, or reverses with maturation and to reconcile neonatal–adult differences. We also observed a significant negative correlation between dynamic SFC and network flexibility within each RSN. Notably, network flexibility varied markedly across the cortical hierarchy, displaying relatively lower flexibility in primary sensory cortices but increased flexibility in attention-related areas. This hierarchical organization may reflect a critical neurobiological mechanism balancing neural stability and adaptability across cortical areas51. Stability within RSNs supports consistent and reliable information processing, whereas adaptability enables flexible responses to dynamic cognitive demands and environmental variability32,52. Thus, the observed negative correlation between dynamic SFC within each RSN and network flexibility suggests an intrinsic trade-off, where networks optimized for stable functional interactions inherently exhibit reduced dynamic flexibility, and vice versa. This balance is essential for adaptive cognition and efficient dynamic cognitive control19,53. Taken together, these results indicate an intrinsic interplay among structural maturation, functional stability, and adaptability.

Our mediation analyses revealed the complex relationships among cortical microstructure, dynamic SFC, and network flexibility. Specifically, we observed a robust indirect-only mediation pathway evident in the DMN, suggesting that microstructural variation appears to relate to flexibility primarily through dynamic SFC rather than a direct route. More importantly, we found that dynamic SFC within posterior but not anterior DMN regions significantly mediated the relationship between T1w/T2w ratio and network flexibility. This regional specificity highlights a clear posterior-to-anterior gradient of maturation within the DMN, aligning with theories proposing posterior DMN regions as foundational hubs for integrating structural maturation with flexible network reorganization54,55. This posterior emphasis is consistent with the developmental pattern that posterior cortical areas mature earlier, providing essential structural and functional scaffolding for the subsequent development of advanced perception and cognition56,57. Additionally, the absence of mediation by static SFC indicates that, in early life, it is the moment-to-moment alignment to the structural scaffold—rather than time-averaged coupling—that links cortical microstructure to flexibility.

Comparative analyses between term-born and preterm-born infants further elucidated potential neurodevelopmental disruptions associated with premature birth. Our recent studies have shown widespread alterations of both structural and functional brain networks in preterm-born infants37,58,59,60. Here, we extended these works to find disruptions specifically in dynamic SFC patterns, capturing the intricate interplay between structural rewiring and functional reorganization over time. Our findings suggest that preterm-born infants are particularly vulnerable to disruptions in structural-functional relationships within and between key RSNs. These alterations likely reflect the adverse impact of premature exposure to the extrauterine environment, which may interrupt the typical trajectories of neurodevelopment61,62. Notably, the robust PMA-related increase in dynamic SFC identified within the DMN of term-born infants was absent in preterm infants. Such divergence implies that the protracted extrauterine developmental environment negatively impacts typical maturation processes of structural and functional brain networks, particularly those involved in higher-order cognitive functions crucial for complex cognition and socio-emotional development63,64. These findings align with existing literature showing that accelerated structural-functional maturation predominantly occurs in utero, thereby emphasizing developmental vulnerabilities associated with premature birth1. Collectively, our findings highlight the urgent need for targeted interventions specifically designed to mitigate developmental disruptions and optimize cognitive trajectories among preterm-born infants65. Further longitudinal studies tracking infants from the neonatal period into early childhood are essential to understand how early dynamic SFC patterns evolve and influence subsequent cognitive and behavioral outcomes66. Additionally, exploring the effects of environmental and experiential factors, such as early sensory stimulation, caregiver interactions, and nutritional status, could provide critical insights into the neuroplastic mechanisms underpinning early brain development and highlight intervention points to mitigate developmental vulnerabilities67,68.

Several methodological considerations must be acknowledged when interpreting our findings. First, despite rigorous motion correction and regression techniques being implemented, residual motion artifacts inherent to neonatal imaging remain potential confounds23. Infants, particularly preterm-born neonates, are more prone to motion artifacts due to the natural restlessness and variability in sleep states during scanning, potentially impacting data quality and the reliability of connectivity estimates. Second, parallel mediation analyses in the preterm cohort and in the subset of term-born infants (each n = 51) detected no significant indirect effect of T1w/T2w on network flexibility via dynamic SFC in the DMN. This null result is compatible with either insufficient statistical power or a genuine absence/alteration of the pathway in prematurity; with the current sample size, we cannot adjudicate between these alternatives. Larger preterm cohorts are needed to achieve adequate power and obtain precise indirect-effect estimates in the future. Third, the present study investigated dynamic SFC specifically within the gray matter of the neonatal brain, leaving the white matter largely unexplored. Emerging evidence indicates that white matter exhibits intrinsic functional activity comparable to that observed in gray matter69,70, as reflected by blood-oxygenation-level-dependent (BOLD) signals. Recent studies have demonstrated aberrant white matter SFC linked to clinical symptom severity in various neuropsychiatric conditions71,72. Therefore, future research should examine dynamic SFC within neonatal white matter, expanding our understanding of early structural-functional network integration and its potential implications for developmental outcomes.

In conclusion, the present study provides a detailed characterization of dynamic structure-function interactions during early neonatal brain development, highlighting the essential role of dynamic SFC—particularly within the DMN—in early internal mentation and cognitive integration. The identified disruptions in preterm-born infants underscore the urgent need for targeted interventions during critical developmental periods. A deeper understanding of dynamic SFC mechanisms will be crucial for clarifying the neurobiological basis of cognitive development and addressing neurodevelopmental vulnerabilities in the early stages of life.

Materials and methods

Participants

This study utilized minimally preprocessed neuroimaging data from the third release of the Developing Human Connectome Project (http://developingconnectome.org/)73. Neonates with failed quality control or substantial imaging artifacts, as flagged by the dHCP preprocessing pipelines, were excluded. The final sample comprised 399 neonates, including 348 term-born and 51 preterm-born infants. Term neonates were defined as those born at ≥37 weeks of gestation; preterm neonates were born at <37 weeks. The median gestational age (GA) at birth among term-born neonates was 40.36 weeks (range: 37.00–42.29 weeks; interquartile range [IQR]: 2.43 weeks), and the median postmenstrual age (PMA) at scan was 40.43 weeks (range: 37.43–44.71 weeks; IQR: 4.00 weeks). For the preterm-born group, the median GA at birth was 32.50 weeks (range: 23.71–36.86 weeks; IQR: 6.14 weeks), and the median PMA at scan—performed at term-equivalent age—was 41.14 weeks (range: 37.00–44.29 weeks; IQR: 3.29 weeks). Details regarding the inclusion/exclusion criteria and attrition at each processing step are illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 10. Ethical approval was granted by the appropriate institutional review boards (UK REC reference 14/LO/1169), and written informed consent was obtained from all infants’ parents or legal guardians prior to data acquisition. All ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed.

MRI acquisition

Imaging was conducted at the Evelina Newborn Imaging Centre, Evelina London Children’s Hospital, using a 3 Tesla Philips Achieva scanner equipped with a custom-built 32-channel neonatal head coil and a dedicated neonatal imaging system73. Infants were scanned during natural, unsedated sleep in an environment optimized for comfort and acoustic protection. The total scan time was approximately 63 minutes. High-resolution structural MRI included both T1w and T2w images acquired using a multi-slice fast spin-echo sequence. T1w images were acquired with TR = 4795 ms, TE = 8.7 ms, TI = 1740 ms, slice thickness = 1.6 mm, matrix = 256 × 256, field of view (FOV) = 145 × 122 × 100 mm, and in-plane resolution = 0.8 × 0.8 mm². T2w images were acquired with TR = 12,000 ms, TE = 156 ms, slice thickness = 1.6 mm, matrix = 256 × 256, FOV = 145 × 145 × 108 mm, and in-plane resolution = 0.8 × 0.8 mm². Parallel imaging acceleration factors (SENSE) were 2.27 for T1w and 2.11 for T2w sequences. Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) was performed using a single-shot echo-planar imaging sequence with multiband acceleration (factor = 4). Diffusion sensitizing gradients were applied at b-values of 0, 400, 1000, and 2600 s/mm² across 20, 64, 88, and 128 directions, respectively. Imaging parameters included TR = 3800 ms, TE = 90 ms, slice thickness = 3 mm with a 1.5 mm overlap, and in-plane resolution = 1.5 × 1.5 mm². Resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI) was acquired using a multiband-accelerated echo-planar imaging sequence (multiband factor = 9) with TR = 392 ms, TE = 38 ms, flip angle = 34°, and isotropic spatial resolution of 2.15 mm. A total of 2300 volumes were collected per session. All sequences followed protocols optimized for neonatal neuroimaging and are described in detail in the dHCP release documentation.

Data preprocessing

Anatomical preprocessing employed super-resolution reconstruction to produce high-resolution 3D T1-weighted and T2-weighted volumes. The T1w images were rigidly aligned to T2w volumes and subjected to bias field correction and brain extraction. Tissue segmentation was performed on T2w volumes using the neonatal-specific DRAW-EM algorithm74. Cortical surfaces were extracted and registered using the dHCP surface processing pipeline, and T1w/T2w ratio maps were obtained directly from the release data.

DWI preprocessing included skull stripping, susceptibility distortion correction using fieldmaps75, eddy-current and motion correction using EDDY76, and up-sampling to 1.5 mm isotropic resolution77. b0 images least affected by motion were selected for correction78. Boundary-based registration aligned DWI data to individual T2w images, followed by non-linear transformation to the 40-week symmetric dHCP neonatal template (dHCP-40_week_template) to allow for atlas-based analyses79.

Resting-state fMRI preprocessing was implemented using DPARSF and custom MATLAB scripts80. Approximately 70% of the volumes with minimal head motion (~1600 volumes) were selected per infant37. Volumes were aligned to individual T2w images using FSL’s FLIRT81. Further preprocessing included linear detrending, nuisance regression (24 motion parameters, white matter, CSF, and global signal), and temporal bandpass filtering (0.01–0.08 Hz). Functional data were projected onto the cortical surface and registered to the 40-week symmetric dHCP template using multimodal surface matching (MSM). Final surface-based data were smoothed using a 2 mm full-width-at-half-maximum (FWHM) Gaussian kernel82.

Anatomical ROIs

Cortical parcellation was defined using our neonatal-specific, multimodal brain atlas consisting of 210 cortical regions, optimized for developmental neuroimaging and tailored to the unique anatomical and functional characteristics of the neonatal brain83. This template was derived using T1w, T2w, DWI, and fMRI features, ensuring anatomical symmetry and functional homogeneity between adjacent regions. Following prior approaches84, parcels were assigned to five canonical resting-state networks (RSNs): the sensorimotor network (SMN, 50 ROIs), visual network (VN, 14 ROIs), high-level visual network (HVN, 42 ROIs), ventral attention network (VAN, 68 ROIs), and default mode network (DMN, 36 ROIs). These networks represent important functional domains in the neonatal brain, reflecting mergent macroscale brain organization. Detailed information regarding the parcellation of these RSNs and their corresponding regions is provided in Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Fig. 11.

Dynamic functional network construction

Dynamic functional connectivity networks were estimated using a validated tapered sliding window approach, following established protocols85,86. The BOLD time series from each ROI was segmented into overlapping windows of 39.2 seconds (100 TRs), with a step size of 3.92 seconds (10 TRs), yielding a total of 160 windows per infant. This window length was chosen based on prior work demonstrating that durations within the 30–60 second range offer an optimal trade-off between temporal resolution and the reliable estimation of covariance structures85. Within each window, we computed the covariance matrix across 210 cortical ROIs, resulting in a dynamic sequence of connectivity matrices with dimensions 210 × 210 × 160. This approach enabled time-resolved tracking of functional brain network dynamics throughout the scan duration87.

Structural network construction

Structural brain networks were constructed by performing whole-brain probabilistic tractography to map white matter pathways between cortical ROIs. The 210-ROI parcellation, defined in the 40-week dHCP neonatal template space, was non-linearly registered to each subject’s native diffusion space. The tractography pipeline was implemented using the MRtrix3 toolkit and incorporated neonatal-specific protocols optimized for the unique challenges of the infant brain, such as low myelination and high partial volume effects35,78,88. Specifically, voxel-wise fiber orientation distributions (FODs) were estimated using multi-shell, multi-tissue constrained spherical deconvolution (CSD), which models signal contributions from white matter, gray matter, and cerebrospinal fluid to improve fiber tracking accuracy in partially myelinated tissue89. Tissue response functions were estimated using the msmt_5tt method. Given the intrinsically low fractional anisotropy (FA) in the neonatal brain, a specific FA threshold of 0.2 was applied to ensure a robust and representative white matter response function was estimated. A log-domain intensity normalization method was used to standardize signal intensities across subjects90. Streamlines were initiated from the gray-white matter interface to maximize cortical coverage, a more robust seeding strategy for neonatal data. The iFOD2 algorithm was used to generate 2 million streamlines per subject with the following parameters: a step size of 0.75 mm, minimum and maximum lengths of 20 mm and 200 mm, respectively, and termination thresholds based on an FOD amplitude <0.05 or an angular deviation >45°. The structural connectome was defined by a weighted 210 × 210 matrix in which edge weights corresponded to the streamline count between ROI pairs, corrected for ROI size.

Dynamic structure-function coupling estimation

A multilinear regression model was fitted to estimate the regional, ROI-wise SFC for each ROI separately18. We derived three predictor matrices from each SC matrix: (i) Euclidean distance, indexing geometric/wiring and temporal cost, with \({D}_{{ij}}={{||}{r}_{i}-{r}_{j}{||}}_{2}\) between region centroids; (ii) shortest-path length, capturing routing efficiency along optimal polysynaptic routes, computed as \({L}_{p}^{w}=\frac{1}{n}\mathop{\sum }_{i\in N}\frac{{\sum }_{j\in N,j\ne i}{d}_{{ij}}^{w}}{n-1}\), where \({d}_{{ij}}^{w}\) is the shortest weighted length of path between i and j; and (iii) Communicability, modeling diffusive, multi-path exchange, defined as \({C}_{{ij}}={(\exp ({D}^{-1/2}W{D}^{-1/2}))}_{{ij}}\), where W is the weighted adjacency and \(D={diag}({s}_{i})\) with strengths \({s}_{i}={\sum }_{k=1}^{N}{W}_{{ik}}\)91. These predictors instantiate geometry-limited, routing-based, and diffusion-based communication regimes with established relevance for SFC and its temporal variance18,23. For a given ROI, the response is the FC between the ROI and all other ROIs, while the predictors were Euclidean distance, path length, and communicability between the ROI and all other ROIs. The level of SFC was measured using ROI-wise R2 from the multilinear model. We fitted the multilinear model across the ROIs within each window and resulting in a matrix (210 × 160) for each infant. Every row of the matrix depicts the SFC fluctuations over time. To estimate dynamic SFC, Pearson’s correlation coefficients of SFC fluctuations between all ROI pairs were further calculated to construct the covariance matrices (210 × 210) for each infant. To assess distinct versus shared variance among these structural predictors, we also estimated SFC for single, pairwise, and combined models. Group-mean R² increased from single to paired models and peaked when all three predictors were included, indicating partially non-overlapping contributions (Supplementary Fig. 12).

Individualized prediction analysis

A CPM framework was employed to predict PMA from dynamic SFC patterns92. We implemented a 10-fold cross-validation procedure to ensure robust and unbiased performance estimation. In each fold, the dataset was partitioned into a training set (90%) and a held-out test set (10%), with each subject serving as test data once. Within each training set, dynamic SFC features were correlated with PMA using non-parametric Kendall’s Tau correlations. Features showing significant associations (p < 0.01) were retained to generate a binary feature mask. For each subject, the retained features were then averaged into a single summary score. A linear regression model was fitted between these summary scores and PMA values in the training set, after regressing out potential confounding variables, including head motion, sex, and birth weight. The trained model was subsequently applied to the test set to predict PMA using the same feature mask and summary procedure. This process was repeated across all folds, yielding out-of-sample PMA predictions for each participant.

Network flexibility

Network flexibility was quantified using the GenLouvain community detection algorithm applied to multilayer functional connectivity matrices93. Specifically, temporal communities were identified via modularity maximization across sliding windows, enabling the detection of community affiliations for each ROI at each time point. Regional flexibility was defined as the proportion of windows in which a given ROI switched its community assignment, normalized by the total number of possible transitions94. This measure reflects the extent to which each node dynamically reconfigures its functional affiliations over time, distinguishing rigid temporal cores (low flexibility) from peripheral, highly adaptive regions (high flexibility). Given the stochasticity inherent in modularity optimization, the community detection process was repeated 50 times per subject. Flexibility scores were computed for each run and subsequently averaged to obtain robust, subject-level estimates of regional network flexibility.

Statistics and reproducibility

Between-group comparisons and correlations were evaluated using nonparametric permutation testing (10,000 iterations) and Spearman’s correlation. Friedman nonparametric one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare brain metric (dynamic SFC, T1w/T2w ratio, and network flexibility) differences between RSNs. Mediation analyses were conducted to test whether dynamic SFC mediated the relationship between T1w/T2w ratio and network flexibility. Specifically, T1w/T2w ratio, dynamic SFC, and flexibility were entered as independent, mediator, and dependent variables, respectively. False discovery rate (FDR) correction was applied to control for multiple comparisons, with statistical significance defined at FDR-corrected p < 0.05. To evaluate the reproducibility of our findings, we performed sensitivity analyses using alternative window lengths (80–120 TRs) and step sizes (5–20 TRs), confirming the stability of the observed dynamic SFC patterns across a broad parameter space.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data used in the current study are provided by the developing Human Connectome Project and can be downloaded through their website (http://www.developingconnectome.org/). Other data underlying the graphs and charts in the main and Supplementary Figs. are available at https://github.com/zztute/Dynamic-SFC.git.

Code availability

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) data were preprocessed using FMRIB Software Library (FSL; https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl) and MRtrix3 (https://www.mrtrix.org). Resting-state fMRI data were preprocessed using SPM12 (Welcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, UK; www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm), Data Processing & Analysis for (Resting-State) Brain Imaging (DPABI) toolbox 4.3 version, DynamicBC toolbox 2.2 version (http://restfmri.net/forum/DynamicBC), and GenLouvain (http://netwiki.amath.unc.edu/GenLouvain) implemented in the MATLAB 2022b (Math Works, Natick, MA) platform. Mediation analyses were performed in R package bruceR. Other data processing and analysis code are available on our GitHub repository (https://github.com/zztute/Dynamic-SFC.git).

References

Grotheer, M. et al. Human white matter myelinates faster in utero than ex utero. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2303491120 (2023).

Dall’Orso, S. et al. Development of functional organization within the sensorimotor network across the perinatal period. Hum. Brain Mapp. 43, 2249–2261 (2022).

Li, Q. et al. Development of segregation and integration of functional connectomes during the first 1000 days. Cell Rep. 43, 114168 (2024).

Park, S. et al. A shifting role of thalamocortical connectivity in the emergence of cortical functional organization. Nat. Neurosci. 27, 1609–1619 (2024).

Franca, L. G. S. et al. Neonatal brain dynamic functional connectivity in term and preterm infants and its association with early childhood neurodevelopment. Nat. Commun. 15, 16 (2024).

Nielsen, A. N. et al. Maturation of large-scale brain systems over the first month of life. Cereb. Cortex 33, 2788–2803 (2023).

Thomason, M. E. Development of brain networks in utero: relevance for common neural disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 88, 40–50 (2020).

Thompson, D. K. et al. Characterization of the corpus callosum in very preterm and full-term infants utilizing MRI. NeuroImage 55, 479–490 (2011).

Eyre, M. et al. The Developing Human Connectome Project: typical and disrupted perinatal functional connectivity. Brain: J. Neurol. 144, 2199–2213 (2021).

Turk, E. et al. Functional Connectome of the Fetal Brain. J. Neurosci.:. J. Soc. Neurosci. 39, 9716–9724 (2019).

Tousignant, B., Eugene, F. & Jackson, P. L. A developmental perspective on the neural bases of human empathy. Infant Behav. Dev. 48, 5–12 (2017).

Dubois, J. et al. The early development of brain white matter: a review of imaging studies in fetuses, newborns and infants. Neuroscience 276, 48–71 (2014).

Casey, B. J., Giedd, N. J. & Thomas, K. M. Structural and functional brain development and its relation to cognitive development. Biol. Psychol. 54, 241–257 (2000).

Park, H. J. & Friston, K. Structural and functional brain networks: from connections to cognition. Science 342, 1238411 (2013).

Hermundstad, A. M. et al. Structural foundations of resting-state and task-based functional connectivity in the human brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 6169–6174 (2013).

Suarez, L. E., Markello, R. D., Betzel, R. F. & Misic, B. Linking structure and function in macroscale brain networks. Trends Cogn. Sci. 24, 302–315 (2020).

Fotiadis, P. et al. Structure-function coupling in macroscale human brain networks. Nat. Rev. Neuroscience 25, 688–704 (2024).

Vazquez-Rodriguez, B. et al. Gradients of structure-function tethering across neocortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 21219–21227 (2019).

Zamani Esfahlani, F., Faskowitz, J., Slack, J., Misic, B. & Betzel, R. F. Local structure-function relationships in human brain networks across the lifespan. Nat. Commun. 13, 2053 (2022).

Dong, X. et al. How brain structure–function decoupling supports individual cognition and its molecular mechanism. Hum. Brain. Mapp. 45, e26575 (2024).

Popp, J. L. et al. Structural-functional brain network coupling predicts human cognitive ability. NeuroImage 290, 120563 (2024).

Zhao, S. et al. Sex differences in anatomical rich-club and structural-functional coupling in the human brain network. Cereb. cortex 31, 1987–1997 (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. Time-resolved structure-function coupling in brain networks. Commun. Biol. 5, 532 (2022).

Fukushima, M. et al. Structure-function relationships during segregated and integrated network states of human brain functional connectivity. Brain Struct. Funct. 223, 1091–1106 (2018).

Fotiadis, P. et al. Myelination and excitation-inhibition balance synergistically shape structure-function coupling across the human cortex. Nat. Commun. 14, 6115 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Dynamic structure-function coupling across three major psychiatric disorders. Psychol. Med. 54, 1629–1640 (2024).

Liu, G. et al. Aberrant dynamic structure–function relationship of rich-club organization in treatment-naïve newly diagnosed juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Hum. Brain Mapp. 43, 3633–3645 (2022).

Feng, G. et al. Spatial and temporal pattern of structure-function coupling of human brain connectome with development. elife 13, RP93325 (2024).

Bernhardt, B. C. et al. Multiscale Structure–Function Gradients in the Neonatal Connectome. Cereb. Cortex 30, 47–58 (2020).

Ball, G. et al. Cortical morphology at birth reflects spatiotemporal patterns of gene expression in the fetal human brain. PLoS Biol. 18, e3000976 (2020).

Betzel, R. F., Satterthwaite, T. D., Gold, J. I. & Bassett, D. S. Positive affect, surprise, and fatigue are correlates of network flexibility. Sci. Rep. 7, 520 (2017).

Safron, A., Klimaj, V. & Hipolito, I. On the importance of being flexible: dynamic brain networks and their potential functional significances. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 15, 688424 (2021).

Huntenburg, J. M., Bazin, P. L. & Margulies, D. S. Large-scale gradients in human cortical organization. Trends Cogn. Sci. 22, 21–31 (2018).

Fukushima, M. & Sporns, O. Structural determinants of dynamic fluctuations between segregation and integration on the human connectome. Commun. Biol. 3, 606 (2020).

Grotheer, M. et al. White matter myelination during early infancy is linked to spatial gradients and myelin content at birth. Nat. Commun. 13, 997 (2022).

Wu, Y. J. et al. Rapid learning of a phonemic discrimination in the first hours of life. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 1169–1179 (2022).

Li, M. Y. et al. Development of visual cortex in human neonates is selectively modified by postnatal experience. eLife 11, e78733 (2022).

Lyall, A. E. et al. Dynamic development of regional cortical thickness and surface area in early childhood. Cereb. Cortex 25, 2204–2212 (2015).

Cao, M., Huang, H. & He, Y. Developmental connectomics from infancy through early childhood. Trends Neurosci. 40, 494–506 (2017).

Chen, M. et al. Default mode network scaffolds immature frontoparietal network in cognitive development. Cereb. Cortex 33, 5251–5263 (2023).

Gao, W., Alcauter, S., Smith, J. K., Gilmore, J. H. & Lin, W. Development of human brain cortical network architecture during infancy. Brain Struct. Funct. 220, 1173–1186 (2015).

Grayson, D. S. & Fair, D. A. Development of large-scale functional networks from birth to adulthood: A guide to the neuroimaging literature. NeuroImage 160, 15–31 (2017).

Siffredi, V. et al. Corpus callosum structural characteristics in very preterm children and adolescents: Developmental trajectory and relationship to cognitive functioning. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 60, 101211 (2023).

Sacchi, C. et al. Socio-Emotional and Cognitive Development in Intrauterine Growth Restricted (IUGR) and typical development infants: early interactive patterns and underlying neural correlates. rationale and methods of the study. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 12, 315 (2018).

Sylvester, C. M. et al. Network-specific selectivity of functional connections in the neonatal brain. Cereb. Cortex 33, 2200–2214 (2023).

Silbereis, J. C., Pochareddy, S., Zhu, Y., Li, M. F. & Sestan, N. The cellular and molecular landscapes of the developing human central nervous system. Neuron 89, 248–268 (2016).

Cábez, M. B. et al. Characterisation of the neonatal brain using myelin-sensitive magnetisation transfer imaging. Imaging Neurosci. 1, 1–17 (2023).

Funfschilling, U. et al. Glycolytic oligodendrocytes maintain myelin and long-term axonal integrity. Nature 485, 517–521 (2012).

Huntenburg, J. M. et al. A systematic relationship between functional connectivity and intracortical myelin in the human cerebral cortex. Cereb. Cortex 27, 981–997 (2017).

Jiang, L. et al. Gene transcription, neurotransmitter, and neurocognition signatures of brain structural-functional coupling variability. Nat. Commun. 16, 7623 (2025).

Song, B. et al. Maximal flexibility in dynamic functional connectivity with critical dynamics revealed by fMRI data analysis and brain network modelling. J. Neural Eng. 16, 056002 (2019).

Cohen, J. R. The behavioral and cognitive relevance of time-varying, dynamic changes in functional connectivity. NeuroImage 180, 515–525 (2018).

Betzel, R. F. & Bassett, D. S. Multi-scale brain networks. NeuroImage 160, 73–83 (2017).

Leech, R. & Sharp, D. J. The role of the posterior cingulate cortex in cognition and disease. Brain: J. Neurol. 137, 12–32 (2014).

Buckner, R. L. & DiNicola, L. M. The brain’s default network: updated anatomy, physiology and evolving insights. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 20, 593–608 (2019).

Zhao, Z. et al. Age-dependent functional development pattern in neonatal brain: An fMRI-based brain entropy study. NeuroImage 297, 120669 (2024).

Namiranian, R., Moghaddam, H. A., Khadem, A., Jafari, R. & Chalechale, A. Assessment of resting state structural-functional relationships in perisylvian region during the early weeks after birth. Brain Struct. Funct. 230, 167 (2025).

Zhao, Z., Li, R., Wu, Y., Li, M. & Wu, D. State-dependent inter-network functional connectivity development in neonatal brain from the developing human connectome project. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 71, 101496 (2025).

Zheng, W. et al. Spatiotemporal developmental gradient of thalamic morphology, microstructure, and connectivity from the third trimester to early infancy. J. Neurosci.: J. Soc. Neurosci. 43, 559–570 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Profiling cortical morphometric similarity in perinatal brains: Insights from development, sex difference, and inter-individual variation. NeuroImage 295, 120660 (2024).

Smyser, C. D. et al. Resting-state network complexity and magnitude are reduced in prematurely born infants. Cereb. Cortex 26, 322–333 (2016).

Bouyssi-Kobar, M. et al. Regional microstructural organization of the cerebral cortex is affected by preterm birth. NeuroImage. Clin. 18, 871–880 (2018).

Wang, W. et al. Altered cortical microstructure in preterm infants at term-equivalent age relative to term-born neonates. Cereb. Cortex 33, 651–662 (2023).

McBryde, M., Fitzallen, G. C., Liley, H. G., Taylor, H. G. & Bora, S. Academic outcomes of school-aged children born preterm: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e202027 (2020).

Yrjölä, P. et al. Facilitating early parent-infant emotional connection improves cortical networks in preterm infants. Sci. Transl. Med. 14, eabq4786 (2022).

Bernabe-Zuniga, J. E. et al. Early interventions with parental participation and their implications on the neurodevelopment of premature children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 34, 853–865 (2025).

Lautarescu, A., Bonthrone, A. F., Bos, B., Barratt, B. & Counsell, S. J. Advances in fetal and neonatal neuroimaging and everyday exposures. Pediatr. Res. 96, 1404–1416 (2024).

Tooley, U. A. et al. Prenatal environment is associated with the pace of cortical network development over the first three year of life. Nat. Commun. 15, 7932 (2024).

Li, J. et al. A neuromarker of individual general fluid intelligence from the white-matter functional connectome. Transl. Psychiatry 10, 147 (2020).

Ding, Z. et al. Detection of synchronous brain activity in white matter tracts at rest and under functional loading. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 595–600 (2018).

Qing, P. et al. Structure-function coupling in white matter uncovers the hypoconnectivity in autism spectrum disorder. Mol. Autism 15, 43 (2024).

Zhao, J. et al. Structure-function coupling in white matter uncovers the abnormal brain connectivity in Schizophrenia. Transl. Psychiatry 13, 214 (2023).

Edwards, A. D. et al. The developing human connectome project neonatal data release. Front. Neurosci. 16, 886772 (2022).

Makropoulos, A. et al. Automatic whole brain MRI segmentation of the developing neonatal brain. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 33, 1818–1831 (2014).

Andersson, J. L., Skare, S. & Ashburner, J. How to correct susceptibility distortions in spin-echo echo-planar images: application to diffusion tensor imaging. NeuroImage 20, 870–888 (2003).

Andersson, J. L. R. & Sotiropoulos, S. N. An integrated approach to correction for off-resonance effects and subject movement in diffusion MR imaging. NeuroImage 125, 1063–1078 (2016).

Kuklisova-Murgasova, M., Quaghebeur, G., Rutherford, M. A., Hajnal, J. V. & Schnabel, J. A. Reconstruction of fetal brain MRI with intensity matching and complete outlier removal. Med. Image Anal. 16, 1550–1564 (2012).

Bastiani, M. et al. Automated processing pipeline for neonatal diffusion MRI in the developing Human Connectome Project. NeuroImage 185, 750–763 (2019).

Makropoulos, A. et al. The developing human connectome project: A minimal processing pipeline for neonatal cortical surface reconstruction. NeuroImage 173, 88–112 (2018).

Yan, C. & Zang, Y. DPARSF: A MATLAB Toolbox for “Pipeline” Data Analysis of Resting-State fMRI. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 4, 13 (2010).

Jenkinson, M., Bannister, P., Brady, M. & Smith, S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. NeuroImage 17, 825–841 (2002).

Glasser, M. F. et al. The minimal preprocessing pipelines for the Human Connectome Project. NeuroImage 80, 105–124 (2013).

Li, M. et al. Multi-modal multi-resolution atlas of the human neonatal cerebral cortex based on microstructural similarity. NeuroImage 272, 120071 (2023).

Molloy, M. F. & Saygin, Z. M. Individual variability in functional organization of the neonatal brain. NeuroImage 253, 119101 (2022).

Allen, E. A. et al. Tracking$te. Cereb. Cortex 24, 663–676 (2014).

Kim, J. et al. Abnormal intrinsic brain functional network dynamics in Parkinson’s disease. Brain J. Neurol. 140, 2955–2967 (2017).

Smith, S. M. et al. Network modelling methods for FMRI. NeuroImage 54, 875–891 (2011).

Tournier, J. D., Calamante, F. & Connelly, A. Improved probabilistic streamlines tractography by 2nd order integration over fibre orientation distributions. Proc. Int. Soc. Magn. Resonance Med. (2010).

Christiaens, D. et al. Global tractography of multi-shell diffusion-weighted imaging data using a multi-tissue model. NeuroImage 123, 89–101 (2015).

Jeurissen, B., Tournier, J. D., Dhollander, T., Connelly, A. & Sijbers, J. Multi-tissue constrained spherical deconvolution for improved analysis of multi-shell diffusion MRI data. NeuroImage 103, 411–426 (2014).

Crofts, J. J. & Higham, D. J. A weighted communicability measure applied to complex brain networks. J. R. Soc. Interface 6, 411–414 (2009).

Shen, X. et al. Using connectome-based predictive modeling to predict individual behavior from brain connectivity. Nat. Protoc. 12, 506–518 (2017).

Jutla, I. S., Jeub, L. G. S. & Mucha, P. J. A Generalized Louvain Method for Community Detection Implemented in Matlab. Available online at: http://netwiki.amath.unc.edu/GenLouvain (2011–2012).

Harlalka, V., Bapi, R. S., Vinod, P. K. & Roy, D. AtypicAl flexibility in dynamic functional connectivity quantifies the severity in autism spectrum disorder. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 13, 6 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participants in this study. This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (STI 2030-Major Project 2021ZD0201705; to B.L.), Hangzhou Normal University Discipline and Talent Cultivation Fund (4045C5021920465; to B.L.), and Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LMS25H180005; to Z.Z.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Z. designed the study, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. C.Z. analyzed the data. X.Z., Y.X., M.L., and W.Z. carried out the data curation, validation, and visualization. W.D. provided technical assistance. B.L. conceptualized the study and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Sahar Ahmad and Jasmine Pan.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Z., Zhang, C., Zhang, X. et al. Dynamic structure-function coupling in macroscale neonatal brain networks. Commun Biol 9, 35 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09300-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09300-4