Abstract

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) relies on radiofrequency (RF) excitation of proton spin. Clinical diagnosis requires a comprehensive collation of biophysical data via multiple MRI contrasts, acquired using a series of RF sequences that lead to lengthy examinations. Here, we developed a vision transformer-based framework that explicitly utilizes RF excitation information alongside per-subject calibration data (acquired within 28.2 s), to generate a wide variety of image contrasts including fully quantitative molecular, water relaxation, and magnetic field maps. The method was validated across healthy subjects and a cancer patient in two different imaging sites, and proved to be 94% faster than alternative protocols. The transformer-based MRI framework (TBMF) may support the efforts to reveal the molecular composition of the human brain tissue in a wide range of pathologies, while offering clinically attractive scan times.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is among the most powerful diagnostic tools in present-day clinical healthcare1. One compelling advantage is its wide versatility, which allows a single imaging modality to acquire a wide variety of biophysical information2. This is a consequence of the ability to program MRI scans to emphasize a particular tissue property of interest. Various pathways exist for modulating the MRI contrast, such as the use of gradients in diffusion-weighted imaging. Another commonly applied pathway is the design and application of a series of radiofrequency (RF) pulses to initiate a cascade of interactions with the tissue proton spins. The particular waveform, duration, power, and frequency of each RF pulse, as well as the characteristics of the entire RF train ensemble, affect the resulting contrast, which can be customized to detect microstructure, water content, cellularity, blood flow, molecular composition, and even functional characteristics3.

As a single MRI pulse sequence is generally not enough to determine the tissue state and make a diagnosis with sufficient certainty, standard clinical MRI exams involve the serial acquisition of multiple pulse sequences4. For example, brain cancer MRI protocols typically comprise T1-weighted, T2-weighted, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery and diffusion, and may also require perfusion and MR-spectroscopy imaging5. While multi-sequence acquisition provides rich information, it typically increases the scan time6. Moreover, the image contrast depends not only on the acquisition parameters, but also on the particular tissue characteristics, which may be highly variable across subjects. For example, while a given protocol may be able to differentiate multiple tumor components in one patient, it may be insufficient for another individual, and may require fine-tuning of the RF pulses (e.g., choosing a different flip angle, saturation pulse power, etc.). As radiological image analysis is commonly performed “offline", namely, after the acquisition is completed and the subject has left, rescheduling a subject scan for re-imaging with a modified acquisition protocol is either impractical or results in increased costs and prolonged waiting lines7.

In recent years, the need to enhance the biochemical information portfolio provided by MRI has prompted the search for new contrast options. Saturation transfer (ST) MRI represents one such promising option8, due to the RF-tunable sensitivity for various molecular properties, such as mobile protein and peptide volume fractions, intracellular pH, and glutamate concentration9. ST-MRI has shown promise for a variety of clinical applications10, such as tumor detection and grading11,12, early stroke characterization13,14, neurodegenerative disorder imaging15,16, and kidney disease monitoring17,18. However, the integration of ST-MRI into clinical practice has been slow and limited because of the relatively long scan times required. Moreover, as each ST target compound is characterized by a distinct proton exchange rate9,19, a separate pulse sequence must be acquired for each application of interest, thereby rendering multi-contrast ST imaging even less practical.

Quantitative imaging of biophysical tissue properties offers improved reproducibility, sensitivity, and consistency across sites and scanners, compared to contrast-weighted imaging20. In this context, imaging techniques that combine biophysical (differential equation-based) models with artificial intelligence (AI) have recently been suggested to be useful for accelerating water-pool relaxometry21,22,23,24,25 or quantitative ST-MRI acquisition and reconstruction26,27,28,29,30,31,32. In recent years, substantial improvements in magnetic resonance fingerprinting (MRF)21,33,model-based image reconstruction34, machine learning based reconstruction35, and fast imaging sequences36 have further accelerated scan time and accuracy, with some of these benefits already being implemented in commercially available imaging scanners37.

Unfortunately, the complexity of the multi-proton-pool in-vivo environment and the challenges in accurately modeling the large number of free tissue parameters limit the efficacy of model-based approaches for molecular MRI. This leads to substantial variability between the biophysical values reported by various groups (each incorporating different model assumptions)38,39,40 or to increased acquisition times, as water pool and magnetic field parameters may need to be separately estimated via additional pulse sequences, to reduce the model complexity27,41.

Here, we describe the development of a transformer-based MRI framework (TBMF), which can provide rich biological information in vivo, while circumventing the need for lengthy multi-pulse-sequence MRI acquisition (requires only a 28.2 s-long calibration scan). TBMF is not explicitly guided by the Bloch equations and instead learns in a data-driven manner. When employed on unseen subjects, pathology, and scanner models at a different imaging site from where the training set was obtained, TBMF was able to generate a variety of new image contrasts as well as fully quantitative molecular, water relaxation, and magnetic field maps.

Results

TBMF framework

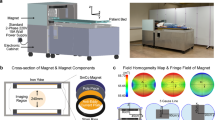

The TBMF core module (Fig. 1a) was designed to investigate the spatiotemporal dynamics of MRI signal propagation as a response to RF excitation, and enable the generation of on-demand image contrast. The system includes a vision transformer42,43 with a dual-domain input, comprised of RF excitation information and real-world tissue response image counterparts. An extension module was also designed, which quantifies six biophysical tissue parameters across the entire 3D brain, without the need for any additional input.

The core module inputs are a sequence of m = 6 non-steady-state MRI calibration images and an RF excitation parameter tensor (Fig. 1a). The tensor includes two concatenated parts: the acquisition parameters used for obtaining the calibration images and the desired on-demand parameters for the subsequent image output. Separate embeddings for the real-image-data and the physical RF properties are then learned using a vision transformer and a fully connected layer, respectively. The quantification module involves a transfer learning strategy where the core module weights are plugged in, the last layer is removed, and there is augmentation of two new convolutional layers. Ground truth reference data are then used to instigate quantification-oriented learning (Fig. 1b).

The TBMF framework was trained using over 3 million image and acquisition parameter pairs from 9 healthy human volunteers (two of them were used for hyperparameter tuning), scanned at a single imaging site (Tel Aviv University) on a 3T MRI (Prisma, Siemens Healthineers) equipped with a 64-channel coil (Supplementary Table 1). The framework was then tested using over 30,000 image and acquisition parameter pairs obtained from 4 other subjects representing three challenging datasets: (i) Two healthy subjects not used for training (scanned at the same site). (ii) A brain cancer patient scanned at a different imaging site (Erlangen University Hospital). (iii) A healthy volunteer scanned using different hardware and MRI model at a different imaging site (Erlangen University Hospital, Trio MRI with a 32-channel coil).

Biophysical-model-free multi-contrast prediction

The core module was validated for generating on-demand molecular (semisolid magnetization transfer (MT) and amide proton chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST)-weighted) images. The full reference imaging protocol consisted of 30 pseudo-random RF excitations (Supplementary Fig. 1)27. The first six images were used for per-subject calibration, followed by TBMF predictions of the multi-contrast images associated with the next six response images (Fig. 1a). A representative example of the TBMF output compared to the ground truth for each of the validation datasets is shown in Fig. 2 and whole-brain 3D reconstruction output is provided as Supplementary Movie 1 (semisolid MT) and Supplementary Movie 2 (amide). A visual, perceptive, and quantitative pixelwise similarity was obtained between TBMF output and ground truth. This is reflected by a structural similarity index measure (SSIM) > 0.96, peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) > 36, and normalized mean-square error (NRMSE) < 3% (Table 1).

a Automatic prediction of unseen molecular MRI contrast weighted images. The multi-domain input used includes a sequence of m non-steady-state MRI calibration images and a radiofrequency (RF) excitation parameter tensor. It includes the acquisition parameters associated with the calibration images (solid lines) and the on-demand acquisition parameters (dashed lines) for the desired image output (m new images shown at the top). Separate embeddings for the real-image-data and the physical RF properties are learned using a vision transformer and a fully connected layer, respectively. b A quantification module for the simultaneous mapping of six tissue and scanner parameter maps, including the semi-solid proton volume fraction (fss) and exchange rate (kssw), water proton longitudinal (T1) and transverse (T2) relaxation, and static (B0) and transmit (B1) magnetic fields. This module exploits the multi-domain embedding learned by the core module, utilizing a transfer learning strategy.

A comparison between representative ground truth (a, c, e) and TBMF-predicted (b, d, f) molecular MRI contrast-weighted images in the human brain. a, b Semisolid magnetization transfer (MT)-weighted images from an unseen subject. c, d Amide proton transfer chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST)-weighted images from a brain tumor patient scanned at an unseen imaging site. e, f Semisolid MT-weighted images from an unseen subject scanned at an unseen imaging site with different hardware to that used for training.

To evaluate the ability to generate an up to 4-times longer output compared to the input, the process was continued recursively, until the entire 30-long sequence was predicted based on the first six calibration images (Supplementary Movie 3 (semisolid MT) and Supplementary Movie 4 (amide)). Although there were some errors in the last six images, the overall performance remained high, with a SSIM > 0.94, PSNR > 32, and NRMSE < 3.7% (Table 1). The inference times for reconstructing whole brain 6 or 24 unseen image contrasts were 7.674 s and 10.896 s, respectively, when using an Nvidia RTX 3060 GPU, and 9.495 s and 19.55 s, respectively, when using a desktop CPU (Intel I9-12900F).

Rapid quantification of biophysical tissue parameters

The quantification module was trained to receive the exact same input as the core module, and then produce six parameter maps: the semisolid MT proton volume fraction (fss) and exchange rate (kssw), water pool longitudinal (T1) and transverse (T2) relaxation times, and the static (B0) and transmit (B1) magnetic fields. The TBMF reconstructed paramater maps were visually, perceptually, and quantitatively similar to the ground truth reference (Figs. 3, 4, 5 panels a, b and Supplementary Fig. 2). The reconstruction performance was highest for the test subject scanned by the same scanner used for training (SSIM = 0.919 ± 0.024; PSNR = 30.197 ± 1.808; NRMSE = 0.049 ± 0.008), followed by the cancer patient (unseen pathology at an unseen imaging site: SSIM = 0.884 ± 0.024; PSNR = 26.349 ± 1.246; NRMSE = 0.059 ± 0.007), and the unseen subject scanned using unseen hardware at an unseen imaging site (SSIM = 0.811 ± 0.044; PSNR = 24.186 ± 1.523; NRMSE = 0.076 ± 0.011). The inference time required for reconstructing whole-brain quantitative images was 6.751 s or 9.822 s when using an Nvidia RTX 3060 GPU or a desktop CPU (Intel I9-12900F), respectively.

a Ground truth reference images obtained using conventional T1 and T2-mapping, water shift and B1 (WASABI), and semisolid magnetization tansfer (MT) MR-fingerprinting (MRF) in 8.5 min. b The same parameter maps obtained using TBMF in merely 28.2 s (94% faster scan time). c Quantitative reconstruction using conventional supervised learning (RF tissue reponse pretraining excluded), utilizing the same raw input data used in (b) for comparison. d Statistical analysis of the SSIM, PSNR, and NRMSE performance measures, comparing the TBMF reconstructed parameter maps compared to reference ground truth (n = 69 brain image slices per group). In all box plots the central horizontal lines represent median values, box limits represent upper (third) and lower (first) quartiles, whiskers represent 1.5 ✕ the interquartile range above and below the upper and lower quartiles, respectively, and all data points are plotted. ****p < 0.0001, two-tailed t-test.

a Ground truth reference images obtained using conventional T1 and T2-mapping, WASABI (for B0 and B1 mapping), and semisolid MT MR-Fingerprinting (MRF) in 8.5 min. b The same parameter maps obtained using TBMF in merely 28.2 s (94% faster scan time). c Quantitative reconstruction using conventional supervised learning (RF tissue reponse pretraining excluded), utilizing the same raw input data used in (b) for comparison. d Statistical analysis of the SSIM, PSNR, and NRMSE performance measures, comparing the TBMF reconstructed parameter maps to reference ground truth (n = 68 brain image slices per group). In all box plots: the central horizontal lines represent median values, box limits represent upper (third) and lower (first) quartiles, whiskers represent 1.5 the interquartile range above and below the upper and lower quartiles, respectively, and all data points are plotted. ****p < 0.0001, two-tailed t-test.

a Ground truth reference images obtained using conventional T1 and T2-mapping, WASABI (for B0 and B1 mapping), and semisolid MT MR-Fingerprinting (MRF) in 8.5 min. b The same parameter maps obtained using TBMF in merely 28.2 s (94% faster scan time). c Quantitative reconstruction using conventional supervised learning (RF tissue reponse pretraining excluded), utilizing the same raw input data used in (b) for comparison. d Statistical analysis of the SSIM, PSNR, and NRMSE performance measures, comparing the TBMF reconstructed parameter map to reference ground truth (n = 68 brain image slices per group). In all box plots the central horizontal lines represent median values, box limits represent upper (third) and lower (first) quartiles, whiskers represent 1.5 the interquartile range above and below the upper and lower quartiles, respectively, and all data points are plotted. ****p < 0.0001, two-tailed t-test.

Test-retest study and impact of noise

To characterize the inter- and intra-subject variations, overall repeatability, and reliability, three additional healthy volunteers were recruited. The volunteers were scanned at Tel Aviv University across three different days within 8 months. In addition, on the last scan day, each volunteer was scanned three times with 10-min breaks outside the MRI room. Representative quantitative parameter maps from each scan and subject are shown in Fig. 6 and in Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4, demonstrating the visual repeatability of the results. The quantitative parameters obtained for each scan and subject are detailed in Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Table 3. The average within-subject coefficient of variance (WCoV) of the estimated parameters across several months (Supplementary Table 4) was lower than 7% for all of the parameters except for B0, indicating a high test-retest repeatability. The average WCoV of the estimated parameters across different scans performed on the same day (Supplementary Table 4) was even lower (<2.5% for all the parameters, except for B0). The between-subject CoV values are detailed in Supplementary Table 5. A high repeatability is shown for all scans and maps (less than 3% averaged between subject coefficient of variance (BCOV)), with the exception of the B0 maps. Scatterplots comparing the TBMF results with ground truth values are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5, accompanied by the intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC). An excellent reliability (ICC > 0.97) was demonstrated for the kssw, fss, and T1 mapping. A good reliability (ICC = 0.67–0.75) was obtained for T2 mapping, a fair reliability (ICC = 0.45–0.75) for B1 mapping, and a poor reliability for B0 (ICC < 0.4). The corresponding Pearson correlation coefficients were (r > 0.98, p < 0.0001), (r > 0.75, p < 0.0005), and (r < 0.04, p > 0.9), with n = 9 repeated measurements for three subjects across three different scans.

To assess the impact of noise on the quantification ability of TBMF, we reconstructed all six 3D whole brain quantitative parameter maps (kssw, fss, T1, T2, B0, and B1) in the three healthy volunteers mentioned above (Supplementary Table 1), while adding white Gaussian noise to the input calibration data (SNR ranging from 6 to 60 dB with 2 dB increments). The results are shown in Supplementary Fig. 6. Under a relatively heavy noise (SNR < 20), the NRMSE values compared to ground truth were mostly deteriorated for the B1 quantification task, followed by the T1, B0, semisolid MT exchange parameters, and T2 quantification. The PSNR demonstrated a relatively similar trend, with the PSNR mainly deteriorating for B1 quantification, followed by B0, semisolid MT exchange parameters, and water T1 and T2. The SSIM showed a similar deterioration due to heavy noise, yet the effect was relatively similar across the different parameter maps. Notably, although severe noise will clearly affect the performance, a plateau in performance was obtained at an SNR of approximately 24 dB or higher (Supplementary Fig. 6). Fortunately, several groups have previously measured and characterized the de-facto practical in vivo noise for the quantification task of the parameters detailed in our work to be within an SNR of 46 dB44,45 to 53 dB29, across several different acquisition patterns, readouts (e.g., echo planar imaging and turbo spin echo), acceleration factors, flip angles, and MRI vendors.

Ablation studies

Training loss choice

To verify the appropriateness of the chosen loss, an ablation study was performed. The TBMF core model (Fig. 1a) was separately retrained from scratch using different losses (L146,47,48, SSIM, mean squared error (MSE), or their combinations). Next, the performance of each variant was evaluated using the three healthy volunteers described above. The resulting performance metrics for the on-demand contrast generation task across all slices, and these three volunteers are shown in Supplementary Table 6. Notably, the specific loss used in our work (a combination of SSIM and L1, as described in Equation 1) provided the optimal performance across all three metrics.

Removal-based explanation using Shapley values

To examine the attentiveness of the model to the RF excitation input features, a Shapley additive explanations analysis (SHAP) was performed49,50,51. For each quantitative parameter map, we used the gradient-based explanation mode51 to wrap the trained model and characterize the impact of each RF input parameter on the quantitative whole-brain output. The resulting SHAP summary plots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 7. Interestingly, several dependencies could be reasoned using physics-based logic, suggesting that even without explicit exposure to the governing Bloch–McConnell equations27, the model was able to learn some of the hidden biophysical dynamics. For example, all six most impactful RF parameters for quantifying the B0 map were associated with saturation pulse frequency offsets (Supplementary Fig. 7c), as this parameter is more predictive of static field inhomogeneities than the pulse power52. Other dependecies were in line with previous protocol optimization studies28,53,54, showing that the quantification ability often relies on the minimum and maxmimum possible values for each acquisition parameter; this was the case for fss quantification (Supplementary Fig. 7b), where the two most impactful input “features” were the minimum and maximum saturation pulse frequency offsets (6 ppm and 14 ppm, respectively). Similarly, in the case of kssw quantification, the five most impactful input parameters included again the 6 ppm and 14 ppm frequency offsets, as well as the minimum saturation pulse power (0.5 μT). Notably, the spin history is yet another factor that affects the contribution of each input parameter (Supplementary Fig. 1), which complicates the derivation of direct human intuitive conclusions in all cases.

Transformer interpretability using attention visualization

To gain a basic intuition for the spatial attention mechanism underlying TBMF, the attention weights from each transformer layer were extracted, averaged across the different attention heads55, and overlaid atop the different orientation views of a random healthy volunteer (Supplementary Fig. 8). The first transformer layer seemed to be primarily focused on the white matter in the axial orientation, the frontal and occipital regions at the sagittal orientation, and the dorsal and ventral regions at the coronal orientation. This could potentially indicate that this layer attempts to understand the basic formation of the brain and recognize its borders. The second-layer attention map was more homogeneously dispersed throughout the entire brain volume, with some of the areas already represented in the first layer now excluded (e.g., the center region in the axial slices). The third layer further complemented the information regions highlighted in the previous layers, now more focused on the outer brain regions and borders. Next, we repeated the process for the same subject, yet for a different acquisition protocol input (Supplementary Fig. 9). While some variations compared to the previous protocol (Supplementary Fig. 8) were naturally observed (for example, at the sagittal regions of the first transformer layers), the general trends were kept.

Assessing the contribution of the information captured by the TBMF core module to the quantification task performance using a removal-based ablation study

The same quantification architecture (Fig. 1b) was trained to receive the same inputs, and then output the same six quantitative biophysical parameter maps, but without employing the pre-trained TBMF weights (learnt by the core module, Fig. 1a). This standard supervised learning routine yielded parameter maps with a markedly lower resemblance to the ground truth (Figs. 3, 4, and 5 panel c). The deterioration in output was accompanied by a significantly lower SSIM (0.805 ± 0.057, 0.778 ± 0.062, 0.725 ± 0.066, for the unseen subject, pathology, and hardware datasets, respectively, p < 0.0001, n = 68 image pairs) and PSNR (25.733 ± 1.473, 23.546 ± 1.428, 22.614 < 1.342, for the three datasets, respectively, p < 0.0001, n = 68 image pairs), and a higher NRMSE (0.0842 ± 0.0125, 0.0843 ± 0.0128, 0.092 ± 0.012 for the three datasets, respectively, p < 0.0001, n = 68 image pairs, Figs. 3, 4, and 5 panel d).

Comparison with alternative methods

A comparison with three quantitative MRI methods was performed: Bloch fitting56, classical dot-product based ST MRF32, and physics-informed self-supervised learning57. For fair comparison, all methods were assessed using the same input data, comprised of the six rapidly acquired images described in previous sections. For additional insights, the analysis was repeated by providing the entire 30-image-long input series for each comparison algorithm (Supplementary Fig. 1).

In L-arginine phantoms (see preparation details in the methods section), TBMF provided a clear visual and significant improvement (p < 0.0001, n = 12 image slices) in the estimation of water T1 and T2 compared to alternatives (Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Fig. 11). The TBMF-based proton volume fraction (fs) estimation was closer to the ground truth compared to all reference methods applied using the same input (six images), and comparable to the methods employing 30 input images. For the proton exchange rate quantification (ksw), TBMF absolute percent error (APE) values were again significantly lower compared to the comparison methods using the same image input (p < 0.0001, n = 12 image slices), with the exception of dot product MRF, which was not significantly different (Supplementary Fig. 11). When aggregating the results across all six quantified parameters, the APE values obtained by TBMF were significantly lower (p < 0.02, n = 24–72 parameters per evaluated method, see Supplementary Fig. 12) than all other methods, except for Bloch fitting and physics-informed self-supervised learning that received 30 images as input.

A similar comparison was then performed in three healthy volunteers. The results are shown in Supplementary Figs. 13–15. The APE values obtained by TBMF were significantly lower compared to all methods in the quantification of the semisolid MT proton volume fraction (fss, p < 0.001, n = 217 image slices) and exchange rate (kssw, p < 0.0001, n = 217 image slices), and for water T1 and T2 (p < 0.0001 and p < 0.01, respectively, n = 217 image slices). The APE in estimating the B0 parameter was significantly lower for TBMF compared to DP MRF with 30 input images (p = 0.002, n = 217 image slices), but not compared to DP MRF with six input images. When aggregating the results across all six quantified parameters, the PSNR and SSIM values obtained by TBMF were significantly higher (p < 0.001 and p < 0.03, respectively, n = 217 image slices) than those obtained by all comparison methods (Fig. 15). The NRMSE values were significantly lower (p < 0.05, n = 217 image slices) than all alternative methods, except for Bloch fitting (Supplementary Fig. 15).

Discussion

The past few decades have seen increased reliance on MRI for clinical diagnosis58. In parallel, this has required the introduction of new contrast mechanisms and dedicated pulse sequences10,59,60,61,62,63,64. While offering biological insights and improved diagnosis certainty, the integration of these sequences into routine MRI examinations exacerbates the scan times. Here, we describe the development of a deep-learning-based framework that can rapidly generate a variety of on-demand image contrasts in silico that faithfully recapitulate their physical in vivo counterparts.

The target contrasts requested from TBMF were associated with RF parameters extrapolated beyond the range of the training parameters, thereby representing a highly challenging task (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Data 1). Nevertheless, an agreement between the generated and ground-truth image-sets was obtained (Fig. 2 and Table 1). The dependence of TBMF on the particular set of calibration images used and the desired output contrast was assessed on 18 different input-output pairs (Supplementary Fig. 16). Despite some variability, a satisfactory reconstruction was obtained in all cases (SSIM > 0.96, PSNR > 36, and NRMSE > 2%). Importantly, TBMF was able to overcome unknown initial conditions, as all calibration image-set combinations but one (image indices 1–6, Supplementary Fig. 16) were acquired following an incomplete magnetization recovery.

The core module architecture was designed for image translation of m-to-m size (Fig. 1a, illustrated for m = 6). Nevertheless, it can be recursively applied (by using the model’s output as the next input for generating another set of m images), and maintains an attractive performance, for up to m-to-3m translations (Supplementary Movie 3 and Supplementary Movie 4). Although some errors were visually observed when attempting m-to-4m translation (in the last m = 6 images), additional training with longer acquisition protocols could further improve this performance.

The on-demand contrast generation performance exhibited by TBMF (Table 1) can be attributed to two key factors: (1) The introduction of explicit (and varied) acquisition parameter descriptors into the training procedure; this information is traditionally overlooked and hidden from MR-related neural networks34,35. (2) The incorporation of visual transformers as the learning strategy. These enable the system to address the double sequential nature of the image data obtained from both the 3D spatial domain and the temporal (spin-history) domain. Visual transformers, with their effective attention mechanism, are not only capable of capturing long-range data dependencies but can also understand global image context, alleviate noise, and adapt to various translational tasks43,65.

Contrast-weighted imaging is the prevalent acquisition mode in clinical MRI. However, it has become increasingly clear that quantitative extraction of biophysical tissue parameters may offer improved sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility66,67,68. By harnessing the learnt brain tissue response to RF excitation information learned by the core module, the TBMF framework was further leveraged to simultaneously map six quantitative parameters (Figs. 3–5), spanning three different biophysical realms, namely water relaxation, semisolid macromolecule proton exchange, and magnetic field homogeneity. The results provide a high agreement with the ground truth (Figs. 3–5d and Supplementary Fig. 2).

Importantly, the rich whole-brain information provided by TBMF was reconstructed in only 6.8 s, following a non-steady state rapid acquisition using a single pulse sequence of 28.2 s. This represents a 94% acceleration compared to the state of the art ground-truth reference (acquired in 8.5 min, Fig. 1b). Interestingly, the quantification task results were even less sensitive to the particular pulse sequence used for acquiring the calibration images (Supplementary Fig. 17) than the on-demand contrast generation task (Supplementary Fig. 16).

The success of the quantification module is directly associated with the reliance on TBMF’s core pre-training. This is supported by the significantly higher performance obtained by the quantification module compared to the vanilla use of TBMF (untrained) architecture (Figs. 3–5 panels c, d, n = 68 image slices, p < 0.0001).

The generalization of TBMF predictions was assessed on three datasets, each representing a different challenge. Overall, there proved to be compelling evidence for generalization. It should, however, be noted that, as expected, the parameter quantification of the unseen subject scanned at the same site and scanner used for training yielded the best results. The cancer patient scanned at a different image site yielded the next best performance (only healthy volunteers were used for training), followed by the healthy subject scanned using a different scanner model and hardware at a different imaging site (Fig. 3–5d and Supplementary Fig. 17). When assessing the on-demand contrast generation task performance, the differences between the various test-sets were much less discernible, with mostly subtle variations in the reconstruction metrics (Table 1). In the future, additional training using subjects scanned on other scanner models could be performed to further boost the framework generalization performance. Similarly, training using larger disease cohorts must be performed to improve and explore the method suitability for clinical imaging. Finally, future validation efforts should focus on the generalizability and robustness across different imaging settings and additional acquisition parameters to further verify that the network genuinely captures the underlying spin physics and does not correlate spatial image features with the desired outcome.

The pseudo-random MRI acquisition protocol used in our work (Supplementary Fig. 1) was taken as-is from previous ST MRF studies27,32,38. The main reasons were its previously demonstrated ability for efficient ST parameter encoding (using its original and complete 30-image-long sequence), and to facilitate a fair comparison with alternative approaches (Supplementary Figs. 10–15). As the ST contrast is affected by water T1 and T2, as well as B0 and B1, the sequence enabled a reasonable encoding of most of these parameters (Figs. 3–5). Nevertheless, the lack of saturation pulses at low frequency offsets (<3.5 ppm), as often used in gold-standard ST-based static field homogeneity mapping protocols52, resulted in a relatively low quantification ability for B0 dynamics in vivo (Figs. 3–5). Similarly, adding multiple flip angles to the sequence could better encode for B1 and T2 dynamics. The 3D EPI readout used (with spoilers applied at the end of each saturation block) was chosen due to its previous optimization and demonstrated benefits (e.g., whole brain coverage) for rapid ST imaging38,69. Notably, while the first MRF work used random acquisition parameter patterns21, it is now becoming clear that the encoding capability can be substantially improved using a variety of traditional53,54,70 and AI-based optimization methods28,71,72. While the focus of this study was on the contrast generation and quantification mechanisms associated with TBMF, future work could further improve the multi-parameter encoding ability using dedicated sequence optimization endeavors.

Our work builds upon prior foundational contributions in the field, including MRF, machine learning based quantification, and rapid non-steady state imaging21,24,73,74. Notably, various physics-informed models were previously designed for the rapid quantification of MR properties75, e.g., using self-supervised learning for T276, or ST parameter mapping57. Other works have further leveraged k-space redundancies with machine learning pipelines for additional acceleration77 or performed end-to-end mapping with physics-based model guidance to ensure the consistency of the water relaxometry values78. A different computational route that shares similar concepts with our approach is model-free MR image synthesis48, as was previously implemented for diffusion parameter quantification79,80. The main novelty of the present work is the explicit use of the acquisition parameters alongside a few calibration images for generating on-demand contrasts, and the data-driven quantification of proton exchange (and other) parameters within a short acquisition time.

A phantom study comparing several quantitative MRI methods demonstrated significantly lower quantification errors for TBMF across most output parameters (Supplementary Figs. 11 and12), when all methods were similarly fed with the same challenging 6-image long input (acquired within merely 28.2 s). Increasing the input image series length by fivefold (into 30 images, as originally used in most comparison algorithms)27,32,57 improved the performance of the comparison methods. However, in the majority of cases, they were not significantly better than those of TBMF (Supplementary Figs. 11 and12). Repeating the same experiment in humans demonstrated similar trends (Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15); however, it should be fairly stated that, unlike phantom studies, there is no ultimate ground truth in vivo (e.g., for assessing the semisolid MT proton volume fraction). Another limitation of this study was that not all comparison methods were able to provide all six quantitative parameter maps; the official open-source version of each algorithm was used whenever possible (see “Methods” section).

ST (encompassing both CEST and semisolid MT) is the dominant biophysical mechanism involved in the on-demand contrast generation task. This was chosen as a representative emerging imaging approach that is the focus of much interest from across the medical community10,81,82,83,84,85,86. Nevertheless, the same conceptual framework could potentially be applied for generating on-demand diffusion, perfusion, relaxation, susceptibility, and other contrast-weighted images, given that a per-subject rapidly acquired data from the same general mechanism of interest is provided, alongside the matching acquisition parameters. Notably, a single pulse sequence may represent several biophysical properties, similarly to the way that ST-contrast weighted images are affected by the T1, T2, B0, and B1. Furthermore, while this work was focused on brain imaging, we expect that the same framework could be similarly utilized in other organs/tissues (after proper training). Specifically, biophysical parameter quantification in new target organs, with different molecular composition and drastically different anatomy (such as creatine imaging in the calf muscle), would mandate additional fine-tuning with case-specific data. For example, an (expected) degradation in performance was obtained when using the TBMF trained solely on human brain data for direct inference on L-arginine phantom data (Supplementary Fig. 18 and Supplementary Table 7). A fine-tuning (further training) of the same network using separate phantom data yielded convergence within merely 1 h and yielded further performance improvement (SSIM = 0.9976 ± 0.0004, PSNR = 45.98 ± 0.83, and NRMSE = 0.0085 ± 0.0007). Interestingly, the resulting values were slightly better than those obtained using a TBMF trained solely on phantom data (Supplementary Table 7), which was trained for approximately 24 h until convergence. This is apparently rooted in the richer molecular and spatial information available within the human brain.

Finally, the ground-truth reference used for the quantification task was obtained via standard water proton relaxometry, magnetic field-mapping, and semisolid MT MRF. However, the same quantification module could seamlessly be trained using alternative reference modalities, such as 31P-imaging (for reconstructing intracellular pH maps)87, or even non-MR images (such as Ki-67 proliferation index histological images), thereby creating new cross-modality insights and opportunities.

In summary, we have developed and validated a computational framework for multi-contrast generation and quantitative MRI (Supplementary Table 8). The method is biophysical-model-free and thus, unbiased by pre-existing parameter restrictions or assumptions. Given its ultra-fast on-demand contrast generation ability, we expect this approach to support the efforts to accelerate clinical MRI.

Methods

Human subjects

Fourteen healthy volunteers (five females/nine males, with average age 25.2 ± 4.0) were scanned at Tel Aviv University (TAU), using a 64-channel 3T MRI (Prisma, Siemens Healthineers). The research protocol was approved by the TAU Institutional Ethics Board (study no. 0007572-2) and the Chaim Sheba Medical Center Ethics Committee (0621-23-SMC). Two additional subjects were scanned at University Hospital Erlangen (FAU): a glioblastoma patient (World Health Organization grade IV, IDH mutation, and methylation of MGMT (O(6)-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase) promoter), scanned using the same scanner model described above, and a healthy volunteer, imaged using a different 3T MRI model and coil system (Trio, Siemens Healthineers with a 32 channel coil). The research protocol was approved by the University Hospital Erlangen Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee. All subjects gave written, informed consent before the study. All ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed.

MRI acquisition

Following scout image positioning and shimming, each subject was scanned using five different pulse sequences, all implemented using the Pulseq prototyping framework88,89 and the open-source Pulseq-CEST sequence standard90. Non-steady-state ST images of the amide and semisolid MT proton pools were acquired using two dedicated pulse sequences, as described previously27,38. Each protocol employed a spin lock saturation train (13 × 100 ms, 50% duty-cycle), which varies the saturation pulse power between 0 and 4 μT (detailed pattern available in Supplementary Fig. 1) to generate 30 contrast-weighted images. The saturation pulse frequency offset was fixed at 3.5 ppm for amide imaging91,92 or varied between 6 and 14 ppm for semisolid MT imaging27. The saturation block was fused with a 3D centric reordered EPI readout module69,93, which provided a 1.8 mm isotropic resolution across a whole-brain field of view. The echo time was 11 ms, and the flip angle was set to 15∘. The same rapid readout module and hybrid pulseq-CEST framework were used to acquire additional B0 and B1 maps by using the water shift and B1 (WASABI) method94, and water T1 and T2 maps by using saturation recovery and multi-echo sequences, respectively. The total scan time per subject for all five protocols was 10.85 min (8.5 min for the quantitative reference set described in Fig. 1b).

Data organization

The data from nine healthy subjects scanned at TAU were used for training and validation (hyper-parameter tuning) with a ~ 80%/20% split (7/2 subjects, respectively). Each training sample was composed of an m = 6 image series, and an acquisition parameter tensor, which included the corresponding six saturation pulse power and frequency offset values utilized, as well as the parameters associated with the subsequent m-long image-series output (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1). A 3D volume of maximum 144 × 144 × 144 voxel size was acquired for each subject. After all non-brain-containing slices were removed, 8–12-fold rotation-based data augmentation was performed. The core module was trained using 18 various combinations of acquisition parameter and 6-to-6 image pairs (Supplementary Fig. 16). The training process was repeated for all brain orientation views (axial, sagittal, and coronal) and for both the amide- and semi-solid MT-weighted data. Overall, a total (train and validation) of 563,904 image series/acquisition parameter pairs (3,383,424 single images) were used for core module development. A detailed breakdown of the train, validation, and test sets is available in Supplementary Table 1.

The quantification module implements a transfer learning strategy, which benefited from, and expanded upon, the trained core module. Therefore, a relatively small dataset (85,824 image series and acquisition parameter pairs) was sufficient for its fine tuning.

All images were motion-corrected and registered using elastix95. Skull removal was performed using statistical parameter mapping (SPM)96 on a T1 map. Quantitative reference semisolid MT-MRF maps were obtained using a fully connected neural network trained on simulated dictionaries, where all m = 30 raw input measurements were taken as input. Pixelwise T1, T2, and B0 values were also incorporated as direct NN inputs, for improved reconstruction accuracy27. A detailed description of the ST-MRF reconstruction and quantification procedure has been published previously27,38.

The core module “label” images were derived from the physically acquired non-steady-state amide or semisolid MT data. The quantification module treated the separately acquired B0, B1, T1, T2, fss, and kssw maps as the training set image labels.

The test cohort was composed of three separate datasets: (1) Two healthy volunteers scanned at TAU (not used for training or validation). (2) A healthy volunteer scanned at FAU using a scanner model and hardware different to those used for training. (3) A brain cancer patient scanned at FAU (see more details in the Human Subjects section above).

Core module architecture

The core module (Fig. 1a) was designed to generate “on-demand” image contrast, according to a user-defined acquisition parameter set. It receives a dual-domain input, representing a per-subject (rapidly acquired) calibration image set and RF excitation information. The calibration set was composed of serially acquired image data \(x\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{M\times H\times W}\), where M is the temporal dimension (6 in our case), and H × W are the spatial image dimensions. The RF information is represented by an acquisition parameter tensor \(p\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{2\times (2M)}\), composed of the saturation pulse powers (B1) and frequency offsets (ωrf), associated with the calibration and the “on-demand” image sets, respectively. The module output is a set of new contrast images \(y\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{M\times H\times W}\).

Each calibration image was reshaped into patches that were projected linearly and embedded into a tissue response representation. The acquisition parameter tensor was converted into RF excitation embedding, using a fully connected layer. The dual-domain embedding was then concatenated into a single tensor and transferred into a transformer encoder42,43, with the following hyper-parameters: embedding dimension = 768, MLP size = 3072, transformer layers = 3, attention heads = 4.

The next step involved the sequential application of three convolution layer blocks. The first two blocks comprised 3 × 3 convolutions, batch normalization, ReLU activation function, and Max Pooling. The third block contained an up-sample layer, a 3 × 3 convolution layer, and a sigmoid activation function.

Quantification module architecture

The quantification module was designed to leverage the intricate mapping between the RF irradiation domain and the image domain, as extensively learned by the core module, and then utilize a transfer learning strategy in order to achieve quantitative mapping. Specifically, the same weights used for the on-demand contrast generation task served as the initial state for the transformer encoder in the quantification module. The architecture (Fig. 1b) included several modifications: the last convolutional layer and sigmoid activation were replaced by a new 3 × 3 convolutional layer, batch normalization, and ReLU activation. An additional (fourth) convolutional block was added, concluded by sigmoid activation. The quantification module input was identical to that of the core module, while the target output was six parameter maps: kssw, fss, B0, B1, T1, T2.

Training properties

For both modules, the loss function \({{\mathcal{L}}}\) was defined as a combination of the structural similarity index measure (SSIM) and L1:

Where \(\hat{y}\) is the predicted image sequence, y is the ground truth, λ1 = 0.6, λ2 = 0.4, C1 = 0.0001, C2 = 0.0009, and \({\mu }_{y/\hat{y}}\), \({\sigma }_{y/\hat{y}}^{2}\), and \({\sigma }_{y\hat{y}}\) are the mean, variance, and covariance, respectively. The core module was trained using five RTX 5000 GPUs in parallel, using a batch size = 64, and a learning rate = 0.0004. The training (259 epochs) took 5 days. The quantification module was trained using a single RTX 5000 GPU, with a batch size = 16 and a learning rate = 0.002. The training (348 epochs) took 3 days. All models were implemented in PyTorch (version 2.3.0).

Comparison with alternative algorithms

The performance of TBMF was compared with three alternative approaches: Bloch fitting56, classical dot-product based ST MRF32, and physics-informed self-supervised learning57. These methods were chosen as they all quantify ST parameters, and some also provide T1, T2, and B0 maps (dot product MRF). The methods were implemented using the open-source code available in refs. 32,57.

L-arginine phantoms were prepared as described in27,32,38,91,92. Briefly, various concentrations of L-arginine (L-arg, 25–200 mM, chemical shift = 3 ppm, Sigma-Aldrich) were titrated to different pH levels between 4.0 and 6.0 and placed in a 120 mm diameter cylindrical holder (MultiSample 120E, Gold Standard Phantoms, UK), filled with saline. Multiple phantom variants were created, each with various 6 to 8 vial combinations placed at random locations across the 24 possible sample holders, to ultimately create a training dataset with a similar order to that used in humans. A separate phantom variant was used as a test set. Laboratory scale measured concentrations and separately measured proton exchange rates using the steady state protocol and varied saturation powers (QUESP)97 served as ground truth for the ST estimated parameters in phantoms. Ground truth B0, B1, T1, and T2 were obtained using separate traditional scans, as described in the MRI acquisition section above.

Three healthy human volunteers served as an additional test set (Supplementary Table 1). For fair comparison, all methods were assessed using the same input data, comprised of the six rapidly acquired images, as described in previous sections. For additional insights, the analysis was repeated by providing the entire 30-image-long input series for each comparison algorithm (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Statistical analysis and reproducibility

A two-tailed t-test was calculated using the open-source SciPy scientific computing library for Python98 (Python version 3.9, SciPy version 1.13.1). Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05. Group comparative analyses were carried out using one-way ANOVA, followed by correction for multiple comparisons using a two-sided Tukey’s multiple comparisons test in SciPy. The SSIM, ICC(2, 1), and PSNR were calculated using the open-source SciPy, Pingouin, and scikit-image99 scientific computing libraries for Python. In all box plots, the central horizontal lines represent median values, box limits represent the upper (third) and lower (first) quartiles, the whiskers represent 1.5 ✕ the interquartile range above and below the upper and lower quartiles, respectively, and all data points are plotted. For a reproducibility analysis, three healthy human volunteers served as an additional test set (Supplementary Table 1). Each subject was scanned a total of five times: three times on the same day, and two other times on different days. Reproducibility was assessed using WCoV, BCOV, and ICC.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The main data supporting the results of this study are available within the paper and Supplementary Information. The 3D human data cannot be shared due to subject confidentiality and privacy. Two sample 2D datasets are available at https://github.com/momentum-laboratory/tbmfand https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17712834100.

Code availability

The MRI acquisition protocols used in this work are available in .seq format at the pulseq CEST open library: https://github.com/kherz/pulseq-cest-library/tree/master/seq-library101. The TBMF framework code is publicly available at https://github.com/momentum-laboratory/tbmf and https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17712834100.

References

van Beek, E. J. et al. Value of MRI in medicine: more than just another test? J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 49, e14–e25 (2019).

Yousaf, T., Dervenoulas, G. & Politis, M. Advances in MRI methodology. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 141, 31–76 (2018).

Bernstein, M. A., King, K. F. & Zhou, X. J. Handbook of MRI pulse sequences (Elsevier, 2004).

Ellingson, B. M. et al. Consensus recommendations for a standardized brain tumor imaging protocol in clinical trials. Neuro Oncol. 17, 1188–1198 (2015).

Kaufmann, T. J. et al. Consensus recommendations for a standardized brain tumor imaging protocol for clinical trials in brain metastases. Neuro Oncol. 22, 757–772 (2020).

Edelstein, W. A., Mahesh, M. & Carrino, J. A. MRI: time is dose-and money and versatility. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 7, 650 (2010).

Sreekumari, A. et al. A deep learning–based approach to reduce rescan and recall rates in clinical MRI examinations. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 40, 217–223 (2019).

Van Zijl, P. C., Lam, W. W., Xu, J., Knutsson, L. & Stanisz, G. J. Magnetization transfer contrast and chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI features and analysis of the field-dependent saturation spectrum. Neuroimage 168, 222–241 (2018).

Liu, G., Song, X., Chan, K. W. & McMahon, M. T. Nuts and bolts of chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI. NMR Biomed. 26, 810–828 (2013).

Jones, K. M., Pollard, A. C. & Pagel, M. D. Clinical applications of chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 47, 11–27 (2018).

Zhou, J. et al. Differentiation between glioma and radiation necrosis using molecular magnetic resonance imaging of endogenous proteins and peptides. Nat. Med. 17, 130–134 (2011).

Zhou, J., Heo, H.-Y., Knutsson, L., van Zijl, P. C. & Jiang, S. Apt-weighted MRI: techniques, current neuro applications, and challenging issues. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 50, 347–364 (2019).

Zhou, J., Payen, J.-F., Wilson, D. A., Traystman, R. J. & Van Zijl, P. C. Using the amide proton signals of intracellular proteins and peptides to detect pH effects in MRI. Nat. Med. 9, 1085–1090 (2003).

Sun, P. Z., Zhou, J., Sun, W., Huang, J. & Van Zijl, P. C. Detection of the ischemic penumbra using pH-weighted MRI. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 27, 1129–1136 (2007).

Cai, K. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of glutamate. Nat. Med. 18, 302–306 (2012).

Cember, A. T., Nanga, R. P. R. & Reddy, R. Glutamate-weighted cest (glucest) imaging for mapping neurometabolism: an update on the state of the art and emerging findings from in vivo applications. NMR Biomed. 36, e4780 (2023).

Stabinska, J., Keupp, J. & McMahon, M. T. Cest MRI for monitoring kidney diseases. in Advanced Clinical MRI of the Kidney: Methods and Protocols, 345–360 (Springer, 2023).

Longo, D. L., Cutrin, J. C., Michelotti, F., Irrera, P. & Aime, S. Noninvasive evaluation of renal pH homeostasis after ischemia reperfusion injury by CEST-MRI. NMR Biomed. 30, e3720 (2017).

Bricco, A. R. et al. A genetic programming approach to engineering MRI reporter genes. ACS Synth. Biol. 12, 1154–1163 (2023).

Seiberlich, N. et al. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging (Academic Press, 2020).

Ma, D. et al. Magnetic resonance fingerprinting. Nature 495, 187–192 (2013).

Fujita, S. et al. MR fingerprinting for contrast agent–free and quantitative characterization of focal liver lesions. Radiol. Imaging Cancer 5, e230036 (2023).

Gaur, S. et al. Magnetic resonance fingerprinting: a review of clinical applications. Investig. Radiol. 58, 561–577 (2023).

Cohen, O., Zhu, B. & Rosen, M. S. MR fingerprinting deep reconstruction network (drone). Magn. Reson. Med. 80, 885–894 (2018).

Fyrdahl, A., Seiberlich, N. & Hamilton, J. I. Magnetic resonance fingerprinting: the role of artificial intelligence. in Artificial Intelligence in Cardiothoracic Imaging, 201–215 (Springer, 2022).

Perlman, O., Farrar, C. T. & Heo, H.-Y. MR fingerprinting for semisolid magnetization transfer and chemical exchange saturation transfer quantification. NMR Biomed. 36, e4710 (2023).

Perlman, O. et al. Quantitative imaging of apoptosis following oncolytic virotherapy by magnetic resonance fingerprinting aided by deep learning. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 6, 648–657 (2022).

Perlman, O., Zhu, B., Zaiss, M., Rosen, M. S. & Farrar, C. T. An end-to-end AI-based framework for automated discovery of rapid cest/mt mri acquisition protocols and molecular parameter quantification (AutoCEST). Magn. Reson. Med. 87, 2792–2810 (2022).

Cohen, O. et al. CEST MR fingerprinting (CEST-MRF) for brain tumor quantification using EPI readout and deep learning reconstruction. Magn. Reson. Med. 89, 233–249 (2023).

Nagar, D., Vladimirov, N., Farrar, C. T. & Perlman, O. Dynamic and rapid deep synthesis of chemical exchange saturation transfer and semisolid magnetization transfer MRI signals. Sci. Rep. 13, 18291 (2023).

Kang, B., Kim, B., Park, H. & Heo, H.-Y. Learning-based optimization of acquisition schedule for magnetization transfer contrast MR fingerprinting. NMR Biomed. 35, e4662 (2022).

Vladimirov, N. et al. Quantitative molecular imaging using deep magnetic resonance fingerprinting. Nat. Protoc. 20, 3024–3054 (2025).

Assländer, J. A perspective on MR fingerprinting. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 53, 676–685 (2021).

Heckel, R., Jacob, M., Chaudhari, A., Perlman, O. & Shimron, E. Deep learning for accelerated and robust MRI reconstruction. Magn. Reson. Mater. Phys. Biol. Med. 37, 335–368 (2024).

Chen, Y. et al. AI-based reconstruction for fast MRI-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Proc. IEEE 110, 224–245 (2022).

Liao, C. et al. 3d mr fingerprinting with accelerated stack-of-spirals and hybrid sliding-window and grappa reconstruction. Neuroimage 162, 13–22 (2017).

Trofimova, A. & Kadom, N. Added value from abbreviated brain MRI in children with headache. Am. J. Roentgenol. 212, 1348–1353 (2019).

Weigand-Whittier, J. et al. Accelerated and quantitative three-dimensional molecular MRI using a generative adversarial network. Magn. Reson. Med. 89, 1901–1914 (2023).

Heo, H.-Y. et al. Quantifying amide proton exchange rate and concentration in chemical exchange saturation transfer imaging of the human brain. Neuroimage 189, 202–213 (2019).

Carradus, A. J., Bradley, J. M., Gowland, P. A. & Mougin, O. E. Measuring chemical exchange saturation transfer exchange rates in the human brain using a particle swarm optimisation algorithm. NMR Biomed. 36, e5001 (2023).

Kim, B., Schär, M., Park, H. & Heo, H.-Y. A deep learning approach for magnetization transfer contrast MR fingerprinting and chemical exchange saturation transfer imaging. Neuroimage 221, 117165 (2020).

Hatamizadeh, A. et al. Unetr: transformers for 3d medical image segmentation. In Proc. IEEE/CVF winter conference on applications of computer vision, 574–584 (IEEE, 2022).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929 (2020).

Singh, M. et al. Bloch simulator–driven deep recurrent neural network for magnetization transfer contrast MR fingerprinting and cest imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 90, 1518–1536 (2023).

Singh, M. et al. Saturation transfer MR fingerprinting for magnetization transfer contrast and chemical exchange saturation transfer quantification. Magn. Reson. Med. 94, 993–1009 (2025).

Sun, H. et al. Retrospective T2 quantification from conventional weighted MRI of the prostate based on deep learning. Front. Radiol. 3, 1223377 (2023).

Nykänen, O. et al. Deep-learning-based contrast synthesis from MRF parameter maps in the knee joint. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 58, 559–568 (2023).

Wang, K. et al. High-fidelity direct contrast synthesis from magnetic resonance fingerprinting. Magn. Reson. Med. 90, 2116–2129 (2023).

Letzgus, S. et al. Toward explainable artificial intelligence for regression models: a methodological perspective. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 39, 40–58 (2022).

Nohara, Y., Matsumoto, K., Soejima, H. & Nakashima, N. Explanation of machine learning models using Shapley additive explanation and application for real data in hospital. Comput. Methods Prog. Biomed. 214, 106584 (2022).

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proc. 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 4768–4777 (Curran Associates Inc., 2017).

Kim, M., Gillen, J., Landman, B. A., Zhou, J. & Van Zijl, P. C. Water saturation shift referencing (WASSR) for chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) experiments. Magn. Reson. Med. 61, 1441–1450 (2009).

Zhao, B. et al. Optimal experiment design for magnetic resonance fingerprinting: Cramér-rao bound meets spin dynamics. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 38, 844–861 (2018).

Cohen, O. & Rosen, M. S. Algorithm comparison for schedule optimization in MR fingerprinting. Magn. Reson. Imaging 41, 15–21 (2017).

Chefer, H., Gur, S. & Wolf, L. Transformer interpretability beyond attention visualization. In Proc. IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 782–791 (IEEE, 2021).

Woessner, D. E., Zhang, S., Merritt, M. E. & Sherry, A. D. Numerical solution of the Bloch equations provides insights into the optimum design of paracest agents for MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 53, 790–799 (2005).

Finkelstein, A., Vladimirov, N., Zaiss, M. & Perlman, O. Multi-parameter molecular MRI quantification using physics-informed self-supervised learning. Commun. Phys. 8, 164 (2025).

Smith-Bindman, R. et al. Trends in use of medical imaging in us health care systems and in Ontario, Canada, 2000-2016. JAMA 322, 843–856 (2019).

Ward, K., Aletras, A. & Balaban, R. S. A new class of contrast agents for MRI based on proton chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST). J. Magn. Reson. 143, 79–87 (2000).

Wang, Y. et al. Clinical quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM): biometal imaging and its emerging roles in patient care. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 46, 951–971 (2017).

Wu, B. et al. An overview of CEST MRI for non-MR physicists. EJNMMI Phys. 3, 1–21 (2016).

Van Zijl, P. C. & Yadav, N. N. Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST): what is in a name and what isn’t? Magn. Reson. Med. 65, 927–948 (2011).

Marrale, M. et al. Physics, techniques and review of neuroradiological applications of diffusion kurtosis imaging (DKI). Clin. Neuroradiol. 26, 391–403 (2016).

Duhamel, G. et al. Validating the sensitivity of inhomogeneous magnetization transfer (ihMT) MRI to myelin with fluorescence microscopy. Neuroimage 199, 289–303 (2019).

Khan, S. et al. Transformers in vision: a survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 54, 1–41 (2022).

Buonincontri, G. et al. Three dimensional MRF obtains highly repeatable and reproducible multi-parametric estimations in the healthy human brain at 1.5 T and 3T. Neuroimage 226, 117573 (2021).

Panda, A. et al. Repeatability and reproducibility of 3d MR fingerprinting relaxometry measurements in normal breast tissue. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 50, 1133–1143 (2019).

Yankeelov, T. E., Pickens, D. R. & Price, R. R. Quantitative MRI in cancer (Taylor & Francis, 2011).

Mueller, S. et al. Whole brain snapshot CEST at 3T using 3D-EPI: aiming for speed, volume, and homogeneity. Magn. Reson. Med. 84, 2469–2483 (2020).

Vladimirov, N., Zaiss, M. & Perlman, O. Optimization of pulsed saturation transfer MR fingerprinting (ST MRF) acquisition using the cramér–rao bound and sequential quadratic programming. Magn. Reson. Med. 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.70141 (2025).

Jordan, S. P. et al. Automated design of pulse sequences for magnetic resonance fingerprinting using physics-inspired optimization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2020516118 (2021).

Loktyushin, A. et al. Mrzero-automated discovery of MRI sequences using supervised learning. Magn. Reson. Med. 86, 709–724 (2021).

Choyke, P. L. Quantitative MRI or machine learning for prostate MRI: which should you use? Radiology 289, 138–139 (2018).

Rueckert, D. & Schnabel, J. A. Model-based and data-driven strategies in medical image computing. Proc. IEEE 108, 110–124 (2019).

Zhu, Y. et al. Physics-driven deep learning methods for fast quantitative magnetic resonance imaging: performance improvements through integration with deep neural networks. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 40, 116–128 (2023).

Torop, M. et al. Deep learning using a biophysical model for robust and accelerated reconstruction of quantitative, artifact-free and denoised images. Magn. Reson. Med. 84, 2932–2942 (2020).

Liu, F., Kijowski, R., El Fakhri, G. & Feng, L. Magnetic resonance parameter mapping using model-guided self-supervised deep learning. Magn. Reson. Med. 85, 3211–3226 (2021).

Liu, F., Feng, L. & Kijowski, R. Mantis: model-augmented neural network with incoherent k-space sampling for efficient MR parameter mapping. Magn. Reson. Med. 82, 174–188 (2019).

Golkov, V. et al. Q-space deep learning: twelve-fold shorter and model-free diffusion MRI scans. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 35, 1344–1351 (2016).

Aliotta, E., Nourzadeh, H., Sanders, J., Muller, D. & Ennis, D. B. Highly accelerated, model-free diffusion tensor MRI reconstruction using neural networks. Med. Phys. 46, 1581–1591 (2019).

Kim, M. & Kim, H. S. Emerging techniques in brain tumor imaging: what radiologists need to know. Korean J. Radiol. 17, 598–619 (2016).

Zhou, J. et al. Review and consensus recommendations on clinical apt-weighted imaging approaches at 3T: application to brain tumors. Magn. Reson. Med. 88, 546–574 (2022).

Jabehdar Maralani, P. et al. Chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI: what neuro-oncology clinicians need to know. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 22, 15330338231208613 (2023).

Van Zijl, P. C. Apt-weighted MRI can be an early marker for demyelination. Radiology 299, 435–437 (2021).

Rivlin, M., Perlman, O. & Navon, G. Metabolic brain imaging with glucosamine CEST MRI: in vivo characterization and first insights. Sci. Rep. 13, 22030 (2023).

Armbruster, R. R. et al. Personalized and muscle-specific oxphos measurement with integrated CrCEST MRI and proton MR spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 15, 5387 (2024).

Paech, D. et al. Whole-brain intracellular ph mapping of gliomas using high-resolution 31P MR spectroscopic imaging at 7.0 T. Radiol. Imaging Cancer 6, e220127 (2023).

Ravi, K. S., Geethanath, S. & Vaughan, J. T. Pypulseq: a Python package for MRI pulse sequence design. J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1725 (2019).

Layton, K. J. et al. Pulseq: a rapid and hardware-independent pulse sequence prototyping framework. Magn. Reson. Med. 77, 1544–1552 (2017).

Herz, K. et al. Pulseq-cest: towards multi-site multi-vendor compatibility and reproducibility of cest experiments using an open-source sequence standard. Magn. Reson. Med. 86, 1845–1858 (2021).

Perlman, O. et al. Cest MR-fingerprinting: practical considerations and insights for acquisition schedule design and improved reconstruction. Magn. Reson. Med. 83, 462–478 (2020).

Cohen, O., Huang, S., McMahon, M. T., Rosen, M. S. & Farrar, C. T. Rapid and quantitative chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) imaging with magnetic resonance fingerprinting (MRF). Magn. Reson. Med. 80, 2449–2463 (2018).

Akbey, S., Ehses, P., Stirnberg, R., Zaiss, M. & Stöcker, T. Whole-brain snapshot CEST imaging at 7 T using 3D-EPI. Magn. Reson. Med. 82, 1741–1752 (2019).

Schuenke, P. et al. Simultaneous mapping of water shift and B1 (wasabi)-application to field-inhomogeneity correction of CEST MRI data. Magn. Reson. Med. 77, 571–580 (2017).

Klein, S., Staring, M., Murphy, K., Viergever, M. A. & Pluim, J. P. Elastix: a toolbox for intensity-based medical image registration. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 29, 196–205 (2009).

Ashburner, J. & Friston, K. J. Unified segmentation. Neuroimage 26, 839–851 (2005).

McMahon, M. T. et al. Quantifying exchange rates in chemical exchange saturation transfer agents using the saturation time and saturation power dependencies of the magnetization transfer effect on the magnetic resonance imaging signal (quest and quesp): ph calibration for poly-l-lysine and a starburst dendrimer. Magn. Reson. Med. 55, 836–847 (2006).

Virtanen, P. et al. Scipy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17, 261–272 (2020).

Van der Walt, S. et al. scikit-image: image processing in Python. PeerJ 2, e453 (2014).

Nagar, D. & Perlman, O. Code and sample data for multi-contrast generation and quantitative imaging using a transformer-based MRI framework (tbmf) with RF excitation embeddings. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17712834 (2025).

Liebeskind, A. et al. The pulseq-cest library: definition of preparations and simulations, example data, and example evaluations. Magn. Reson. Mater. Phys. Biol. Med. 38, 1–10 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Tony Stöocker and Rüdiger Stirnberg for their help with the 3D EPI readout. This project was funded by the European Union (ERC, BabyMagnet, project no. 101115639). Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: D.N. and O.P., deep learning methodology: D.N. and O.P., MRI acquisition and reconstruction: M.Z. and O.P., ablation studies and test-retest study: S.I., comparison with state of the art and phantom studies: S.I., N.V., A.F., and O.P., writing, reviewing, and editing: D.N., M.Z., O.P., S.I., N.V., and A.F., supervision: O.P.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

D.N. and O.P. applied for a patent related to the proposed framework (PCT/IL2025/050688). All other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Dafna Sussman, Sairam Geethanath and Martijn Cloos for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editor: Jasmine Pan. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nagar, D., Ifrah, S., Finkelstein, A. et al. Multi-contrast generation and quantitative MRI using a transformer-based framework with RF excitation embeddings. Commun Biol 9, 102 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09371-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09371-3