Abstract

So far, measurements of free calcium in the nanoscale cytosolic region near the plasma membrane remain a challenge in cell biology. We present a convenient approach that combines membrane-bound dyes with cytosolic calcium probes. Manipulations with distinct laser excitations of these dyes allow monitoring of calcium in both the cytosol and the sub-membrane region. Whereas Förster resonance energy transfer induces secondary fluorescence of the calcium probe at distances under 10 nm from the membrane upon membrane dye excitation, direct excitation of the probe visualizes the bulk calcium. Experiments on HEK293 cells and neurons disclose that at rest sub-membrane calcium concentration is large exceeding 400 nM. Furthermore calcium entry through ion channels, exchangers, or ionophores, as well as spontaneous calcium neuronal oscillations, increase calcium concentration up to 1 µM and 800 nM in the pre-membrane domain and in the cytoplasm, respectively. This approach provides a new tool for calcium nanodomain studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Calcium, an indispensable ion for cell metabolism, is a vital secondary messenger ubiquitous to all eukaryotic cells1. In cells of nervous systems, calcium exhibits even more diverse functions, being a key player in electrogenesis, vesicular release, spine formation, synaptic plasticity, transduction of extracellular signals, triggering intracellular signaling cascades, gene expression, etc. Despite the existence of numerous binding sites for calcium in cells, precise targeting in possessing certain calcium-dependent functions occurs. This is achieved in specialized cellular compartments and plasma membrane microdomains like presynaptic endings and spines, as well as plasma membrane lipid rafts in which integral proteins such as ion channels, pumps, transporters, enzymes, etc., are tightly packed to perform fast signaling and to limit calcium spreading. For example, membrane clustering within microdomains enhances Ca2+-dependent crosstalk between neighboring N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs)2, NMDARs and sodium–calcium exchanger (NCX)3,4, and between Na/K-ATPase and NCX5,6. The plasma membrane enriched with cholesterol intrinsic to lipid rafts is essential for this interplay7,8,9. Furthermore, the pharmacological effect of some medicines, in particular memantine10 and tricyclic antidepressants11,12, also depends on NMDAR and NCX coupling in lipid rafts. In addition, calcium-permeable channels clustered within the lipid rafts can generate up to 100 µM local Ca2+ transients13,14 within tens of nanometers from the site of entry and trigger signaling pathways independently of bulk calcium increases15,16.

This knowledge was accumulated based in part on the electrophysiological experiments, in which Ca2+-dependent processes near the inner plasma membrane surface were monitored as changes of NMDAR currents because of Ca2+-dependent desensitization4,5. Apparently, Ca2+ buffering by protein may cooperate with Ca2+ extrusion to balance Ca2+ entry into neurons17, so that the counter transport at rest maintains the pre-membrane Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]m) rather stable. Since different Ca2+-permeable channels are subjected to Ca2+-dependent desensitization, similar crosstalk between them and NCXs may occur8. Whereas this mechanistic understanding of [Ca2+]m dynamics seems plausible, it is based on indirect observations on neuronal currents. Conclusive evidence in favor of this understanding requires direct measurements of [Ca2+]m in a nanoscale region of pre-membrane cytoplasm. Such an experimental approach would considerably strengthen molecular crosstalk and pharmacological studies of lipid rafts, offering new insights into pre-membrane processes underlying basic cellular functions.

Experiments with membrane-targeted genetically encoded Ca²⁺ indicator fluorescent proteins in cultured cells appear to represent a proper solution18,19 that provided substantial progress in this scientific area16,20,21. However, this approach, like others, has its own limitations. First of all, the expression of GCaMPs is not stable between cell types and produces various side effects on cell physiology and channel gating22. If GCaMP is fused to a membrane-targeting sequence, it most localizes to the plasma membrane, but some remains cytosolic, retained in the ER, or cycles via endocytosis, yielding non-membrane fluorescence21. In addition, GCaMPs have at least a 20-fold smaller emission dynamic range23,24 than small molecule Ca2+ sensors like Fluo-8 or Calbryte 52025. Membrane-targeted small molecules like FFP1826 are rarely used because of dim fluorescence and partial detection of extracellular calcium27. Finally, the lateral resolution of an ideal confocal scanning microscope can not be smaller than 250 nm, impeding the ability to distinguish sub-plasma calcium from other cytoplasm. Since confocal microscopy remains diffraction-limited, super-resolution methods like STORM, PALM, SIM, or STED can surpass this limit, yet they are slow or require repeated scanning, making them unsuitable for rapid calcium transients near the plasma membrane28.

To overcome these limitations, we developed a convenient method combining a membrane-bound dye with a cytosolic Ca2+ sensor to detect sub-membrane calcium via Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET)-induced fluorescence, limited to distances <10 nm. This approach allows simultaneous monitoring of both bulk and near-membrane calcium in HEK293 cells and neurons.

Results

Verification of the approach in HEK293 cells

A general idea of how we could measure free calcium in the close proximity of the inner surface of the plasma membrane is illustrated in Fig. 1a. In case of staining of the plasma membrane with some lipid fluorescence dye in cells loaded with a water-soluble calcium probe, the activated light of the lipid dye could cause a secondary fluorescence of the calcium probe at the distance at which FRET is allowed (<10 nm). In agreement, FRET had been demonstrated earlier between the membrane-incorporated probe and the water-soluble dye in the extracellular solution29. To achieve this goal, the plasma membrane of HEK293 cells loaded with the Fluo-8 calcium probe was stained with the externally applied carbocyanine dye DiB (Cellbrite Blue30) (Fig. 1a). The fluorescence of DiB was excited using a 2-photon (2p) laser at a wavelength of 735 nm, which was picked out as optimal for our imaging hardware to achieve maximal fluorescence of DiB at 460 nm with negligible direct excitation of Fluo-8 (Fig. 1b). At 2p excitation, rather intensive blue fluorescence of cell membranes stained with DiB was observed, as well as some green Fluo-8 fluorescence colocalized with DiB of lesser intensity was present (Fig. 1c). Analysis of single-cell emission spectrum revealed green Fluo-8 fluorescence as a deviation from the DiB spectrum, with distinct peak of 515 nm (Fluo-8) as well as 460 nm for DiB (Fig. 1d). To verify whether the fluorescence in the green spectral region is dependent on calcium, experiments with ionomycin (5 µM), an ionophore that allows calcium to enter cells through the plasma membrane, were conducted. Ionomycin increased membrane-associated Fluo-8 fluorescence (Fig. 1c). The rise of [Ca2+]m induced by ionomycin increased the Fluo-8 peak in the emission spectrum and slightly decreased the DiB peak (Fig. 1d), which we refer to as augmented energy transfer between the dyes upon Fluo-8 binding to Ca2+. Thus, this procedure allows recognition of [Ca2+]m increase evoked by calcium influx.

a Schematics of Förster resonance energy transfer (curved arrow) from membrane dye DiB (blue circles) to cytosolic Ca2+-sensitive probe Fluo-8 (green stars) in pre-membrane area. b Spectral diagrams depicting two modes of intracellular Ca2+ detection. “FRET” section—an excitation of DiB by a 2p 735 nm laser and FRET to Fluo-8 to reveal pre-membrane Ca2+. The gray area depicts an overlap integral of the donor emission spectrum with the acceptor absorption spectrum. “Direct” section—a direct excitation of Fluo-8 by 1p 488 nm laser to detect bulk Ca2+. Dotted and solid curves depict excitation and emission spectra of DiB (blue) and Fluo-8 (green), respectively. Ch1 and Ch2—spectral emission ranges for detection of DiB and Fluo-8 fluorescence. c Images of stained live HEK293 cells under 2p 735 nm excitation before and after 5 µM ionomycin application. Fluo-8 emission (Ch2) is associated with membrane DiB emission (Ch1) and increases in response to 5 µM ionomycin. d Emission spectrum of ROI shown in (c) was obtained in the range of 400–600 nm. Blue curve—control, red curve— in the presence of 5 µM ionomycin. Solid areas depict the published reference emission spectra of DiB (blue) and Fluo-8 (green). Absolute fluorescence intensity is presented in arbitrary units—a.u. e Comparison of Fluo-8 emissions in pre-membrane area (2p 735 nm excitation, top row) and in the cytosole volume (1p 488 nm excitation, bottom row) in the presence of 5 µM ionomycin. f The linear intensity profile plotted along the line is shown in (e). FRET-induced Fluo-8 fluorescence co-localizes with the membrane fluorescence. Direct Fluo-8 excitation reveals cytosolic emission smoothly distributed in the cell body. g Emission spectra captured using FRET and direct excitations of the same cell are shown in (e). The dotted line shows the fluorescence spectrum of a similar preparation at 2p 735 nm excitation recorded with Fluo-8 only staining. h Intensity fluorescence diagrams. Mean values ± SEM (shown by bars) of Fluo-8 emission intensities obtained in the absence (control) and presence of 5 µM ionomycin corresponding to pre-membrane Ca2+ (left, n = 10) and bulk Ca2+ (right, n = 21). Data are significantly different (***p = 0.004; ****p = 0.00001 Student’s paired t-test). Circles connected by lines represent data from single cells. i The response to the increase of extracellular KCl concentration from 2.8 to 70 mM of pre-membrane Fluo-8 emission (2p 735 nm excitation) in HEK293 cells expressing NCX1. On the right, images of the cell membrane captured in control (upper one) and at the end of KCl application (lower one). On the left, relative to the values in 2.8 mM KCl, fluorescence intensity values (F/Fo) are plotted along time for Fluo-8 (Ch2) and DiB (Ch1). Mean values with SEM (indicated by bars) from 5 cells are shown. Circles represent individual measurements. The horizontal bars indicate KCl application and time calibration. j Caffeine-induced increase in cytosolic fluorescence observed under 488 nM excitation does not affect pre-membrane fluorescence observed under 2p excitation. Images on the left were captured in control and upon 20 mM caffeine application in Ca2+-free external solution under 2p 735 nm and 1p 488 nM excitations. The chart to the right demonstrates the averaged (between experiments, n = 4) response of cytosolic and pre-membrane fluorescence to caffeine. Relative to control fluorescence intensity values (F/Fo) are plotted along time for Fluo-8 (Ch2). Mean values with SEM (indicated by bars) are shown. Circles represent individual measurements. The horizontal bars indicate caffeine application and time calibration.

We also compared the spatial distribution of the dyes either under 2p excitation of DiB or direct excitation of Fluo-8 with a 1p 488 nm laser (Fig. 1e). Under 2p excitation, the linear profile plotted across the cell body (Fig. 1e, f) reveals narrow 430 ± 55 nm peaks (mean from 24 cells) of DiB and Fluo-8 fluorescence marking the cell borders. Obviously, the peaks are much wider than the expected (~5–10 nm) theoretical FRET distance. Obtained peaks of 350–400 nm in our experimental conditions look well considering the lateral resolution limit of 250 nm of the confocal scanning microscope stated by the manufacturer. Despite blurring, in this case, the light originates from the nanoscale pre-membrane region where FRET is allowed. When excited with 488 nm, the Fluo-8 fluorescence was evenly distributed in the soma (Fig. 1f). Thus, the same calcium probe allows the detection of both sub-membrane calcium via membrane dye excitation and cytosolic calcium via direct excitation (Fig. 1g). In cells stained with only Fluo-8 without DiB, the fluorescence spectrum of the preparation at 2p excitation recorded at the same parameters demonstrates lower amplitude (dotted line in Fig. 1g). This serves as additional confirmation that the green fluorescence during double staining is the result of FRET. In both compartments—pre-membrane and cytosolic, ionomycin caused a substantial increase of [Ca2+]s (Fig. 1h).

We further tested whether this method could be utilized to visualize more physiologically relevant calcium changes in cells determined, for example, by sodium–calcium exchanger (NCX) transports (Fig. 1i). In HEK293 cells expressing NCX1, we applied 70 mM KCl to force the exchanger to transport Ca2+ into the cytosol. In the membrane area at 2p excitation, we observed a Fluo-8 response to KCl application, indicating the Ca²⁺ entry through the exchanger. Therefore, this experimental approach allows monitoring physiologically relevant changes of [Ca2+]m and detecting the Ca2+ entry through inherent participants of cellular calcium homeostasis. We also tested whether the increase in pre-membrane calcium concentration was the result of calcium entry from the outside or secondary release from intracellular stores. In a calcium-free extracellular solution (containing 5 mM EGTA), application of 20 mM caffeine induced a moderate cytoplasmic response in cells, but no significant changes were recorded in the pre-membrane region (Fig. 1j, n = 5). Although we cannot completely exclude the contribution of calcium release from stores, in our experiments, the pre-membrane response to ionomycin is probably associated with calcium entry from the outside.

In order to widen the applicability of this method, experiments with fluorescent proteins were also performed.

Calcium-sensitive fluorescent proteins as a secondary sensor

As genetically encoded Ca²⁺-sensitive fluorescent proteins are widely used, we tested if FRET is possible between a small-molecule membrane dye (DiB) and a Ca²⁺-sensitive protein (GCaMP6s) located in the cytosol near the plasma membrane (Fig. 2a). In the following experiments, instead of loading Fluo-8, cells were transfected with the plasmid expressing plasma membrane-associated GCaMP6s bearing the CAAX motif. DiB and GCaMP6s provide a FRET pair with almost similar spectra as in previous experiments (Fig. 2b). Under 2p excitation with a 735 nm laser, we observed colocalized DiB and GCaMP6s fluorescences (Fig. 2c). The linear profile across the cell body revealed colocalized peaks of DiB and GCaMP6s fluorescence only at cell membranes (Fig. 2d). Visually observed membrane “thickness” was 410 ± 60 nm (mean from 18 cells), similar to those for the DiB and Fluo-8. Regardless of the membrane targeting, direct 488 nm excitation of GCaMP6s also revealed diffuse somatic fluorescence (Fig. 2d). In contrast, energy transfer from the membrane selectively highlights GCaMP6s within ~10 nm of the plasma membrane and excludes an excitation of molecules located more distantly. Unlike experiments with Fluo-8, under 2p excitation, GCaMP6s fluorescence at the membrane area (ROI1 in Fig. 2c) did not respond to 5 µM ionomycin, as shown by the ROI1 spectrum (Fig. 2e). Ionomycin did not cause fluorescence increase in time for ROIs outlining plasma membrane (Fig. 2f, n = 5). In contradiction, under 488 nm excitation, the whole volume of GCaMP6s in the same cells (cytosolic ROIs, n = 5) responded to 5 µM ionomycin by a multi-fold increase in fluorescence. To explain this discrepancy, we suggested that in a narrow layer adjacent to the plasma membrane, [Ca2+]m is much larger than that of cytosol31,32. Hence, in this narrow layer, GCaMP6s with Kd[Ca] = 140 nM is already saturated by calcium, in contrast to Fluo-8 with Kd[Ca] = 389 nM. Most likely under 488 nm excitation, the response of GCaMP6s located in the cytoplasm predominantly contributes to fluorescence.

a Schematics of Förster resonance energy transfer (curved arrow) from membrane stain DiB (blue circles) to GCaMP6s (green oval). b Spectral diagram of excitation (dotted lines) and emission (solid lines) spectra of DiB and GCaMP6s. The gray area depicts an overlap integral of the donor emission spectrum with the acceptor absorption spectrum. Ch1 and Ch2—spectral emission ranges for detection of DiB and GCaMP6s, respectively. c Images of DiB (Ch 1) and GCaMP6s (Ch 2) captured on live HEK293 cells expressing GCaMP6s and stained with DiB under 2p 735 nm or 1p 488 nm excitation before and after 5 µM ionomycin application. d The linear intensity profile plotted along the line shown in (c). FRET-induced GCaMP6s fluorescence shows better association with the membrane than fluorescence evoked by direct excitation. e Emission spectrum of ROI1 is shown in (c) in the range of 400–600 nm. Blue curve—control, purple curve—after 5 µM ionomycin application. Solid areas depict the published reference emission spectra of DiB and GCaMP6s. Fluorescence intensity is normalized to a maximum at 460 nm. f Average responses from four experiments showing GCaMP6s fluorescence changes over time in pre-membrane and cytosolic ROIs, similar to those shown in (c), following application of 5 µM ionomycin. Pre-membrane ROI fluorescence was recorded in Ch2 using 2p excitation at 735 nm to detect local Ca2+ signals, while cytosolic ROI fluorescence was recorded in Ch2 using one-photon excitation at 488 nm to detect bulk cytosolic Ca2+. Data are presented as relative fluorescence (F/Fo), where Fo is the baseline fluorescence in control conditions and F is the fluorescence in the presence of ionomycin. Mean values ± SEM are shown. Circles represent individual measurements. The horizontal bar indicates the period of ionomycin application (5 µM).

Saturation of calcium-induced fluorescence of a high-affinity Ca2+ probe in the sub-plasma region in the HEK293 cells allows an estimation of [Ca2+]m at least 300 nM. This surprising result forced us to perform experiments on other cell types, in particular on neurons. We examined whether calcium entry into the sub-plasma region could be monitored upon activation of Ca2+-permeable glutamate receptors, in particular of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) type.

Exploring sub-plasma calcium in neurons

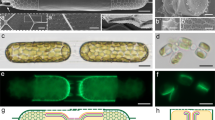

Similar to HEK293 cells, Fluo-8-loaded neurons with DiB-stained membranes demonstrated membrane-localized co-emission of DiB and Fluo-8 under 2p excitation and diffuse Fluo-8 signal in the soma under 1p 488 nm excitation. (Fig. 3a, b). Linear profiles revealed narrow 500 ± 60 nm width peaks (mean from 22 neurons) of DiB and Fluo-8 fluorescence, marking the cell borders. Membrane-associated Fluo-8 fluorescence in neurons suggests that, as in HEK293 cells, the neuronal [Ca2+]m is maintained at a rather large level at rest (Fig. 3c).

a Images of single cell emission in the membrane area (2p 735 nm excitation, top row) and in the cytosole (1p 488 nm excitation, bottom row), obtained in a neuron in the presence of 30 µM NMDA. b The linear intensity profile plotted along the line is shown in (a). FRET-induced Fluo-8 fluorescence co-localizes with the membrane fluorescence. Direct Fluo-8 excitation reveals emission smoothly distributed along the profile. c Images of a neuron in the presence of increasing NMDA concentrations obtained upon excitation by a 2p 735 nm laser. Blue panel—DiB emission at Ch1. Green panels—Fluo-8 emission at Ch2. d Emission spectra in the range of 400–600 nm of ROI are shown in (c) in the presence of different NMDA concentrations. Solid areas depict emission spectra of DiB (blue) and Fluo-8 (green). Absolute fluorescence intensity is in arbitrary units—a.u. e Emission spectra normalized to maximum at 460 nm (F460) to evaluate the crosstalk between Fluo-8 and DiB fluorescence at 515 nm (F515). The 0.08 value corresponds to the reference crosstalk between normalized spectra of DiB and Fluo-8. f A plot of Fluo-8 fluorescence without DiB crosstalk of membrane region as a function of NMDA concentration. Emission intensity is normalized to maximum (FFluo-8/Fmax). 0.95 from the maximum intensity reveals Fluo-8 saturation with Ca2+ and roughly corresponds to the doubled Kd[Ca2+] of Fluo-8. Circles and error bars are means ± SEMs, obtained in the presence of NMDA from 7 experiments. Circles represent individual measurements. Symbols shown beyond the log-scale correspond to control (left) and ionomycin (right).

In HEK293 cells, Fluo-8 allowed to recognize [Ca2+]m increase caused by ionomycin (Fig. 1c,d) whereas GCaMP6s did not (Fig. 2e). In neurons the membrane fluorescence of Fluo-8 increased with an increase of NMDA concentration (Fig. 3c). For each neuron studied, an emission spectrum for a membrane region on the cell similar to the ROI in Fig. 3c was chosen, in which amplitudes of two peaks of emission, F460 (460 ± 5 nm) and F515 (515 ± 5 nm), corresponding to DiB and Fluo-8, were measured. Representative emission spectra are shown in Fig. 3d, e. Whereas in the majority of experiments, obtained spectra resemble those in Fig. 3e, in some spectra the Fluo-8 peak was more pronounced than the DiB one, suggesting perfect conditions for FRET in the particular cell in Fig. 3d. It should be noted that despite spectral variations, the effect of NMDA concentration increase on the amplitude of the Fluo-8 peak and its concentration dependence were similar.

The normalized Fluo-8 emission (FFluo8/Fmax) versus NMDA concentrations was plotted (Fig. 3f). In experiments, F515 saturation was achieved at 100 µM NMDA. At this point, 5 µM ionomycin, which provides an additional pathway to NMDARs for calcium entry through the plasma membrane, did not cause a further increase in F515, suggesting that the Fluo-8 emission is already saturated. Therefore, this saturation could be attributed to the fluorescence rather than to the saturation of calcium entry through NMDARs. In some neurons, as the NMDA concentration increased, we observed a reciprocal redistribution of emission from F460 to F515, indicating an increase in FRET efficiency (Fig. 3d) upon [Ca2+]m increase. Based on the assumption that in the absence of calcium, the fluorescence of the Fluo-8 dye is absent, and 100 μM NMDA alone or with ionomycin causes fluorescence saturation of Fluo-8 bound with calcium, and taking into account Kd[Ca]Fluo-8 = 389 nM, one can estimate the [Ca2+]m (Fig. 3f). Without NMDA, pure Fluo-8 emission in the membrane area was slightly above half of the maximal fluorescence, which roughly corresponds to the Kd of Fluo-8. Accordingly, even at rest, [Ca2+]m in 10 nm proximity to the membrane probably exceeds 389 nM, which is higher than in cytosol (<100 nM). Saturation of the calcium probe upon application of NMDA allows us to conclude that under these particular conditions [Ca2+]m is at least twice as large as Kd for Fluo-8 and exceeds 800 nM.

To broaden applicability and validate the approach, we performed experiments with a FRET pair of NeuroDio green fluorescent plasma membrane dye and Cal590 calcium probe, in which both dyes are excited by visible light. Since low-affinity Ca2+ probes could be more appropriate, considering the fluorescence saturation of Fluo-8, a relatively high Cal590 Kd[Ca2+] of 561 nM33 represents an additional advantage to estimate [Ca2+]m with more accuracy.

A schematic of what we expect to obtain in experiments is shown in Fig. 4a. Indeed, NeuroDio green fluorescent plasma membrane dye and Cal590 calcium probe with green absorption and orange emission form a FRET pair (Fig. 4a, b). NeuroDio has an advantage over DiB due to its brighter fluorescence, better solubility in neuronal membranes, and visible light excitation. In the presence of 30 µM NMDA upon NeuroDiO excitation with a 488 nm laser (Fig. 4b), the spatial distribution of Cal590 fluorescence along the linear profile crossing the neuronal soma (Fig. 4c, d) was similar to that of DiB and Fluo-8 (Fig. 3a, b). Direct excitation of Cal590 with a 543 nm laser (Fig. 4b) revealed a uniform Cal590 distribution in the cytosol. An overlay of Cal590 fluorescence in neurons under 488 and 543 nm excitations (Fig. 4e) provided a distinct image of two sub-plasma and cytosolic Ca2+ compartments (video in Supplement A). It should be emphasized that the fluorescence shown by green color in Fig. 4e emits from the pre-membrane region within <10 nm of FRET and uncovers the existence of a pre-membrane calcium domain in which a rather large calcium concentration is maintained. Under 488 nm excitation (Fig. 4b), an increase of NMDA concentration resulted in a gradual increase of pre-membrane fluorescence at 590 nm (F590) corresponding to Cal590 emission (Fig. 4f). For each NMDA concentration, we also captured Cal590 fluorescence under 543 nm to obtain a cytosolic Ca2+ response. Both cytosolic and sub-plasma Ca2+ responses were averaged between neurons and plotted versus NMDA concentration (Fig. 4g). In analogy with Fluo-8 experiments, on top of the 100 µM NMDA effect, 5 µM ionomycin was added to achieve full Cal590 fluorescence because of Ca2+ overload. In contradiction to Fluo-8, ionomycin further increased the intensity of fluorescence for both pre-membrane and cytosolic compartments. Hence, in the case of Cal590, the NMDAR activation can not provide a sufficient Ca2+ inflow to reach a probe saturation. As Fluo-8 in similar experiments in the presence of 100 µM NMDA ionomycin did not increase fluorescence, the difference between probes is presumably determined by a larger value of Cal590 Kd[Ca2+] (561 nM) than those of Fluo-8 (389 nM). Therefore, for Cal590, the intensity of fluorescence was normalized to maximal intensity at saturation (100 µM NMDA + 5 µM ionomycin). Obviously, [Ca2+]m in neurons at rest exceeds half-maximum for Cal590 saturation and can be estimated as ~800 nM according to Cal590 Kd[Ca2+] of 561 nM. A much lower basal Ca2+ level of ~100 nM was found in cytosol, which corresponded well with usual concentrations in cells34. Since Cal590 was not saturated in the presence of 100 µM NMDA, the [Ca2+]m could be estimated as 1 µM, and the cytosolic response of about 700 nM.

a Schematics of Förster resonance energy transfer (curved arrow) from membrane dye Neuro-DIO (green circles) to cytosolic Ca2+-sensitive probe Cal590 (orange stars) in pre-membrane area. b Spectral diagrams depicting two modes of intracellular Ca2+ detection. “FRET” section—an excitation of Neuro-DIO by 488 nm laser and FRET to Cal-590 to reveal pre-membrane Ca2+. The gray area depicts an overlap integral of the donor emission spectrum with the acceptor absorption spectrum. “Direct” section - a direct excitation of Cal-590 by 543 nm laser to detect cytosolic Ca2+. Dotted and solid curves depict excitation and emission spectra of Neuro-DIO (green) and Cal-590 (orange), respectively. Ch1 and Ch2—spectral emission ranges for detection of Neuro-DIO and Cal-590 fluorescence. c Images of single cell emission in the membrane area (488 nm excitation) and in the cytosole (543 nm excitation) in the presence of 30 µM NMDA. d The linear intensity profile plotted along the line is shown in (c). FRET-induced Cal590 fluorescence shows association with the membrane. The fluorescence induced by direct excitation is distributed smoothly along the cytoplasm. e An overlay of Cal590 fluorescence demonstrating membrane-associated and cytosolic fluorescence of Cal590 in the same group of neurons. f Emission spectra in the range of 505 to 615 nm of the membrane area of a neuron in the presence of different NMDA concentrations. Spectra are normalized to membrane fluorescence at F510. Solid areas depict emission spectra of Neuro-DiO (green) and Cal590 (red). The crosstalk between Neuro-DiO and Cal590 fluorescence at 590 nm was 0.04 of F510 for normalized reference spectra. g A plot of fluorescence of Cal590 without Neuro-DiO crosstalk as a function of NMDA concentration. Black - pre-membrane fluorescence, green - cytosolic maximum intensity reveals Cal590 saturation with Ca2+ and roughly corresponds to the doubled Kd[Ca2+] of Cal590. Circles and error bars are means ± SEMs, obtained in the presence of NMDA from 20 to 30 experiments. Circles represent individual measurements. Symbols shown beyond the log-scale correspond to control (left) and ionomycin (right). hImages of Neuro-DiO and Cal590-stained neurons captured at different moments t1 and t2 of spontaneous neuronal activity. ROI1 and ROI2 correspond to the membrane and cytosol regions of a single cell. i Fluorescence intensity for membrane area (ROI1) and cytosolic area (ROI2) plotted over time for neuron at (h). j Intensity fluorescence diagrams. Mean values ± SEM (shown by bars) of Fluo-8 emission intensities obtained at two time points t1 and t2, corresponding to pre-membrane Ca2+ (left, n = 11) and bulk Ca2+ (right, n = 9). Data are significantly different (***p = 0.0004; ****p = 0.00001, Student’s paired t-test). Circles connected by lines represent data from single cells.

With these stainings, we observed synchronous spontaneous [Ca2+] oscillations in cultured neurons in both the membrane area (ROI1) and cytosol (ROI2) (Fig. 4h), suggesting that staining procedures did not affect neuron functions. In agreement, spontaneous cytosolic and sub-plasma Ca2+ oscillations were observed in many cells. Cytosolic oscillations were of large amplitude (Fig. 4i), accompanied by small sub-plasma oscillations. The differences between basal (t1) and peak (t2) amplitudes were considerable (Fig. 4i, j). Thus, the proposed approach has a wide potential in the simultaneous detection of pre-membrane and bulk calcium in different cell types at rest and in dynamics.

Discussion

Our study introduces a novel FRET-based approach to monitor sub-plasma membrane Ca2+ dynamics with nanoscale precision, overcoming key limitations of existing methods such as genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators (GECIs) and conventional small-molecule dyes. By double staining with membrane-targeted fluorescent dyes (DiB, NeuroDiO) and cytosolic Ca²⁺ sensors (Fluo-8, Cal590, GCaMP6s), we demonstrate that [Ca2+]m within ~10 nm of the inner plasma membrane is considerably higher (300–800 nM) than in the cytosol at rest and increases further upon Ca2+ influx through NMDARs or NCX. These findings provide direct experimental support for the long-standing hypothesis that nanodomains near the plasma membrane maintain elevated Ca2+ levels, which is important for rapid signaling and local effector targeting31,32.

A special feature of the near-membrane region is the high electric field strength of the membrane, which is sufficient for the dehydrogenation of calcium ions at a distance of up to 7 nm from the membrane35. Membrane potential (typically negative inside) helps Ca2+ ions attach to the membrane surface, forming a diffuse layer of counterions. Probably, this attraction helps concentrate Ca2+ near the membrane, facilitating its role in signaling and in screening of membrane surface negative charges for proper electrogenesis.

In our experiments, GCaMP6s (Kd ~ 140 nM) failed to exhibit sub-membrane Ca2+ increases, likely due to saturation by the high basal [Ca2+] in this compartment. This aligns with prior work suggesting that high-affinity probes are unsuitable for measuring [Ca2+]m16,22. In contrast, Fluo-8 (Kd = 389 nM) and Cal590 (Kd = 561 nM) provided dynamic ranges sufficient to resolve resting and activity-dependent changes and further supported their use for nanodomain studies.

In HEK293 cells and neurons, resting [Ca2+]m is ~400–800 nM, far exceeding cytosolic levels (<100 nM). This spatial asymmetry reveals the functional segregation of Ca2+ microdomains, where localized influx preferentially activates nearby effectors (e.g., NCX, CaMKII) without global cytosolic flooding.

We provide direct evidence that the sub-plasma membrane zone is a high-Ca2+ compartment, dynamically regulated by channels and transporters. This compartmentalization enables spatially precise signaling, critical for synaptic plasticity, excitotoxicity, and drug actions.

The [Ca2+]m we observed (<1 µM) is markedly lower than values reported using calcium-activated ion channels (e.g., KCa) as sensors, which suggest sub-plasmalemmal concentrations around 10 µM36,37. Even higher [Ca2+]m up to ~50 µM was estimated in depolarized smooth muscle cells in the narrow space between the plasma membrane and SR38. In squid giant axons, a low-affinity aequorin mutant detected synaptic “hot spots” of 200–300 µM during action potentials13. The lower [Ca2+]m we observed likely reflects that KCa colocalizes with calcium channels in microdomains, reporting local [Ca2+]m near entry sites. In contrast, our measurements evaluated the average [Ca2+]m across the entire plasma membrane, including regions without Ca2+ influx. Additionally, the use of ionomycin to facilitate calcium entry in our experiments apparently cannot cause calcium transients similar to those in microdomains in smooth muscle or neurons.

Currently, plasma membrane-targeted GECIs are widely used for Ca2+ imaging because they enable genetic targeting to specific cell types or organelles and allow long-term in vivo studies. However, their expression levels vary across cell types, and overexpression can disrupt channel gating and other physiological processes. Even with membrane-targeting sequences, GECIs often leak into the cytosol or organelles, producing non-specific fluorescence. Compared to small-molecule probes, they offer narrower dynamic and spectral ranges, and fast-response variants tend to saturate in sub-membrane microdomains, impeding detection of local Ca2+ dynamics. Moreover, confocal microscopy remains diffraction-limited, preventing reliable resolution of near-membrane signals.

The double-staining FRET method addresses several of these limitations. It provides simple, dye-based labeling that is independent of expression variability, with broader spectral and dynamic ranges than GECIs. The double-staining approach does not optically overcome the diffraction limits (~250 nm), but <10 nm energy transfer ensures specificity to the sub-membrane compartment. A practical limitation is that membrane dyes gradually redistribute into intracellular membranes within hours due to recycling; therefore, selective plasma membrane measurements are best performed immediately after staining. Moderate-affinity small-molecule dyes remain effective in high-Ca2+ environments, capturing both basal and activity-dependent changes with fast temporal resolution. The proposed method lacks the genetic specificity of GECIs, but it minimizes physiological interference and requires only the simple procedure of dye loading.

We also demonstrated the possibility of FRET from a membrane fluorescent label to cytosolic GECI, potentially allowing the advantages of both approaches to be combined.

Methods

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells

Immortalized human kidney embryonic (HEK293T) cells were obtained from Biolot Ltd. (Russia). Cells were plated onto 7 mm glass coverslips pretreated with poly-L-lysine (0.2 mg/ml) in 35 mm culture dishes at 1 × 105 cells per dish. For some experiments, before staining, HEK cells were transiently transfected with an expression vector encoding NCX1 (Rat NCX1.1 (pcDNA3.1+), Addgene Cat. #75190) or with GCaMP6s (pGP-CMV-GCaMP6s-CAAX, Addgene Cat. #52228) using GenJect-40 reagent (dia-m.ru, Russia) according to standard manufacturer protocol. Briefly, transfection was performed by adding to each dish 50 µl serum-free medium containing 1 µg total DNA and 1 µl GenJect-40. Staining and experiments were performed 24–72 h after transfection.

Primary culture of cortical neurons

All manipulations on animals were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Federation for Laboratory Animal Science Associations and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees of Sechenov Institute (Protocol 1-6/2022 from 21.01.2022). We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use. Briefly, 16 days pregnant Wistar rats (16 female rats used in this study, supplied by the Sechenov Institute Animal Facility) were placed in a plastic box connected to a CO2 tank by a tube and then sacrificed by 1 min CO2 inhalation. Fetuses were removed, and then primary cultures of rat cortical neurons were prepared using conventional procedures as described earlier39. Neurons were grown in Neurobasal culture medium supplemented with B-27 (Gibco-Invitrogen, UK) on glass 15 mm diameter coverslips coated with poly-D-lysine and were used for experiments after 12–14 days in culture.

Fluorescent Labeling

For experiments, HEK cells and neurons grown on glass coverslips were consequently stained with a FRET pair of cytosolic (acceptor) probe and then membrane-associated dye (donor). For plasma membrane labeling, we used CellBrite Blue (Biotium) based on DiB lipophilic blue fluorescent dye30,40 or CellBrite Green (Biotium) based on green NeuroDiO33,41. Cytosolic Ca2+-sensitive probes were Fluo-8-AM (Abcam), Cel-590-AM (AAT Bio), or GCaMP6s protein.

DiB + Fluo-8 FRET pair

First, HEK cells or neurons were loaded with Fluo-8 by incubating cells for 30 min in a dish containing 500 µl of Hanks solution with 1.6 µM Fluo-8-AM (Abcam). After washing, cells were incubated in Hank's solution for 30 min. For HEK cells expressing GCaMP6s, Fluo-8 loading was omitted. Then, the cells were incubated for 60 min in 1 ml growth media containing 7 µl CellBrite Blue (Biotium) + 7 µl loading buffer (Biotium). Cells were washed out with Hank’s solution before the experiment. All procedures were done at 37 °C.

Neuro-DIO + Cal-590 FRET pair

First, neurons were loaded with Cal-590 by incubating for 30 min in Hank's solution containing 1.6 µM Cal-590-AM (AAT Bio). After washing, cells were incubated for 5 min in 1 ml Hank's solution containing 0.4 µL CellBrite Green (Biotium) + 0.02% Pluronic F-127 (Sigma-Aldrich, P2443). Pluronic was added to facilitate membrane dye incorporation into neuronal membranes42; otherwise, staining was too weak. Next, cells were washed and incubated in Hank's solution for 30 min. All procedures were done at 37 °C.

Image capture

For experiments, coverslips with stained cells were placed in an imaging chamber (Chamlide CA-PI, volume ~200 µl) and were continuously perfused at a rate of 0.5 ml/min with the following extracellular basic solution (BS) (in mM): 140 NaCl, 2.8 KCl, 2.0 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, at pH 7.3–7.4. Images were captured using a Leica TCS SP5 MP inverted microscope.

For DiB + Fluo-8 staining, DiB fluorescence was excited with a two-photon (2p) laser (Chameleon Ti:Sapphire by Coherent) at 735 nm to obtain FRET to Fluo-8 (Fig. 1a, b). Alternatively, Fluo-8 was directly excited with a one-photon (1p) laser at 488 nm. DiB emission was detected by Ch1 photomultiplier (PMT) at 460 ± 7 nm. Fluo-8 emission was detected by Ch2 PMT at 515 ± 7 nm. Both Ch1 and Ch2 were set to similar gains to achieve similar PMT sensitivity for these wavelengths. These parameters were also used to capture images for the DiB + GCaMP6s FRET pair.

For Neuro-DIO + Cal-590 staining, a 1p 488 nm laser was used to induce Neuro-DIO fluorescence to obtain FRET to Cal-590 (Fig. 4a, b). Alternatively, Cal-590 was directly excited with a one-photon (1p) laser at 543 nm. Neuro-DIO emission was detected by Ch1 PMT at 515 ± 7 nm. Fluo-8 emission was detected by Ch2 PMT at 589 ± 7 nm. Both Ch1 and Ch2 were set to similar gains to achieve similar PMT sensitivity for these wavelengths.

To capture images of individual HEK293 cells or neurons, the maximum available magnification was used, which limited the field of view to only a few cells.

To obtain emission spectra, lambda stacks were captured using the automated “xyλ” function of Leica LAS AF software. DiB + Fluo-8 emission was obtained under 2p 735 nm laser excitation without a dichroic mirror. Frames were captured at 10 nm bandwidth, with a 7 nm step advancement from 400 to 600 nm (29 steps). NeuroDio + Cal590 emission was obtained under 1p 488 nm laser excitation with SP500 dichroic mirror. Frames were captured at 10 nm bandwidth, with a 6 nm step advancement from 500 to 620 nm (20 steps). Gain and laser intensity settings were adjusted to avoid detector saturation and were not altered during the experiment.

Calcium responses of cells were elicited either by the addition of 5 µM ionomycin or, in the case of neurons, by stepwise increases in the concentration of NMDA (glycine 10 µM was added as a co-agonist).

Image analysis

Image analysis was done in Leica LAS AF software. To detect premembrane Ca2+, mean fluorescence intensities were measured in regions of interest (ROIs) outlining the membrane area. For each ROI from the fluorescence of the calcium-sensitive probe, the crosstalk was subtracted from the fluorescence of the membrane dye. Particularly, Fluo-8 fluorescence was calculated as F515−F460 * 0.08, where F460 and F515 correspond to peak emissions of DiB and Fluo-8, respectively (Fig. 3e). Likewise, Cal590 fluorescence was calculated as F590−F510 * 0.04, where F510 and F590 correspond to peak emissions of NeuroDiO and Cal590 (Fig. 4f). To detect cytosolic Ca2+, additional ROIs were selected for the cytoplasm of cells, excluding the plasma membrane.

Statistics

Quantitative data are expressed as mean ± SEM. GraphPad Prism software was used to compare groups of measurements using Student’s two-tailed t-test. Each recording obtained from a single coverslip was considered an independent experiment. The number of experiments is indicated by ‘n’. The level of statistical significance was set to p < 0.05. Data marked by ***, or **** are significantly different with p < 0.001, or p < 0.0001, respectively. Approximations of the data were performed with the usage of Origin Pro software. Obtained values were averaged between experiments and presented as means ± SEM.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Supplementary Data contains source numerical values used for plotting graphs and statistical comparisons for all figures containing the numerical data (Figs. 1i, j, h, 2f, 3f, 4g, and j). Supplement A contains a video illustrating the sub-plasma (green) and cytosolic (red) Ca2+ compartments revealed by double staining of neurons with NeuroDiO and Cal590 (see Fig. 4e). All other data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Clapham, D. E. Calcium signaling. Cell 131, 1047–1058 (2007).

Iacobucci, G. J. & Popescu, G. K. Spatial coupling tunes NMDA receptor responses via Ca²⁺ diffusion. J. Neurosci. 39, 8831–8844 (2019).

Sibarov, D. A. et al. Inhibition of plasma membrane Na/Ca-exchanger by KB-R7943 or lithium reveals its role in Ca-dependent N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor inactivation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 355, 484–495 (2015).

Boikov, S. I., Karelina, T. V., Sibarov, D. A. & Antonov, S. M. Selective inhibitor of sodium–calcium exchanger, SEA0400, affects NMDA receptor currents and abolishes their calcium-dependent block by tricyclic antidepressants. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1432718 (2024).

Sibarov, D. A. et al. Na⁺,K⁺-ATPase functionally interacts with the plasma membrane Na⁺,Ca²⁺ exchanger to prevent Ca²⁺ overload and neuronal apoptosis in excitotoxic stress. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 343, 596–607 (2012).

Ivanova, M. A. et al. Calcium export from neurons and multi-kinase signaling cascades contribute to ouabain neuroprotection in hyperhomocysteinemia. Biomolecules 10, 1104 (2020).

Tian, J. & Xie, Z. J. The Na-K-ATPase and calcium-signaling microdomains. Physiology 23, 205–211 (2008).

Sibarov, D. A. & Antonov, S. M. Calcium dependent desensitization of NMDA receptors. Biochemistry (Moscow) 83, 1173–1183 (2018).

Boikov, S. I., Sibarov, D. A. & Antonov, S. M. Nutritional and metabolic factors, ethanol and cholesterol, interact with calcium-dependent N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor inhibition by tricyclic antidepressants. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 16, 946426 (2022).

Glasgow, N. G. et al. Memantine and ketamine differentially alter NMDA receptor desensitization. J. Neurosci. 37, 9686–9704 (2017).

Stepanenko, Y. D. et al. Dual action of amitriptyline on NMDA receptors: enhancement of Ca-dependent desensitization and trapping channel block. Sci. Rep. 9, 19454 (2019).

Stepanenko, Y. D., Sibarov, D. A., Shestakova, N. N. & Antonov, S. M. Tricyclic antidepressant structure-related alterations in calcium-dependent inhibition and open-channel block of NMDA receptors. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 815368 (2022).

Llinas, R., Sugimori, M. & Silver, R. B. Microdomains of high calcium concentration in a presynaptic terminal. Science 256, 677–679 (1992).

Parekh, A. B. Ca²⁺ microdomains near plasma membrane Ca²⁺ channels: impact on cell function. J. Physiol. 586, 3043–3054 (2008).

Hardingham, G., Arnold, F. & Bading, H. A calcium microdomain near NMDA receptors: on switch for ERK-dependent synapse-to-nucleus communication. Nat. Neurosci. 4, 565–566 (2001).

Shigetomi, E. et al. Imaging calcium microdomains within entire astrocyte territories and endfeet with GCaMPs expressed using adeno-associated viruses. J. Gen. Physiol. 141, 633–647 (2013).

Chamberland, S., Zamora Moratalla, A. & Topolnik, L. Calcium extrusion mechanisms in dendrites of mouse hippocampal CA1 inhibitory interneurons. Cell Calcium 77, 49–57 (2019).

Akerboom, J. et al. Optimization of a GCaMP calcium indicator for neural activity imaging. J. Neurosci. 32, 13819–13840 (2012).

Kempmann, A. et al. The functional characterization of GCaMP3.0 variants specifically targeted to subcellular domains. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 6593 (2022).

Tong, X. et al. Genetically encoded calcium indicators and astrocyte calcium microdomains. Neuroscientist 19, 274–291 (2013).

Shigetomi, E., Kracun, S. & Khakh, B. S. Monitoring astrocyte calcium microdomains with improved membrane targeted GCaMP reporters. Neuron Glia Biol. 6, 183–191 (2010).

Yang, Y. et al. Improved calcium sensor GCaMP-X overcomes the calcium channel perturbations induced by the calmodulin in GCaMP. Nat. Commun. 9, 1504 (2018).

Yamada, Y. & Mikoshiba, K. Quantitative comparison of novel GCaMP-type genetically encoded Ca²⁺ indicators in mammalian neurons. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 6, 41 (2012).

Ye, L., Haroon, M. A., Salinas, A. & Paukert, M. Comparison of GCaMP3 and GCaMP6f for studying astrocyte Ca²⁺ dynamics in the awake mouse brain. PLoS ONE 12, e0181113 (2017).

Lock, J. T., Parker, I. & Smith, I. F. A comparison of fluorescent Ca²⁺ indicators for imaging local Ca²⁺ signals in cultured cells. Cell Calcium 58, 638–648 (2015).

Vorndran, C., Minta, A. & Poenie, M. New fluorescent calcium indicators designed for cytosolic retention or measuring calcium near membranes. Biophys. J. 69, 2112–2124 (1995).

Takahashi, A., Camacho, P., Lechleiter, J. D. & Herman, B. Measurement of intracellular calcium. Physiol. Rev. 79, 1089–1125 (1999).

McCarron, J. G., Chalmers, S., Olson, M. L. & Girkin, J. M. Subplasma membrane Ca2+ signals. IUBMB Life 64, 573–585 (2012).

Foley, M. et al. The lateral diffusion of lipid probes in the surface membrane of Schistosoma mansoni. J. Cell. Biol 103, 807–818 (1986).

Schmidt, A. et al. Antioxidant defense in primary murine lung cells following short- and long-term exposure to plastic particles. Antioxidants 12, 227 (2023).

Eggermann, E., Bucurenciu, I., Goswami, S. P. & Jonas, P. Nanodomain coupling between Ca²⁺ channels and sensors of exocytosis at fast mammalian synapses. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 7–21 (2011).

Canepari, M. & Ross, W. N. Spatial and temporal aspects of neuronal calcium and sodium signals measured with low-affinity fluorescent indicators. Pflügers Arch. 476, 39–48 (2024).

Staffend, N. A. & Meisel, R. L. DiOlistic labeling of neurons in tissue slices: a qualitative and quantitative analysis of methodological variations. Front. Neuroanat. 5, 14 (2011).

Gleichmann, M. & Mattson, M. P. Neuronal calcium homeostasis and dysregulation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 14, 1261–1273 (2011).

Barger, J. P. & Dillon, P. F. Near-membrane electric field calcium ion dehydration. Cell Calcium 60, 415–422 (2016).

Zou, H., Lifshitz, L. M., Tuft, R. A., Fogarty, K. E. & Singer, J. J. Imaging Ca2+ entering the cytoplasm through a single opening of a plasma membrane cation channel. J. Gen. Physiol. 114, 575–588 (1999).

Zhuge, R., Fogarty, K. E., Tuft, R. A. & Walsh, J. V. Jr. Spontaneous transient outward currents arise from microdomains where BK channels are exposed to a mean Ca2+ concentration on the order of 10 µM during a Ca2+ spark. J. Gen. Physiol. 120, 15–27 (2002).

Bradley, K. N., Craig, J. W., Muir, T. C. & McCarron, J. G. The sarcoplasmic reticulum and sarcolemma together form a passive Ca2+ trap in colonic smooth muscle. Cell Calcium 36, 29–41 (2004).

Mironova, E. V., Evstratova, A. A. & Antonov, S. M. A fluorescence vital assay for the recognition and quantification of excitotoxic cell death by necrosis and apoptosis using confocal microscopy on neurons in culture. J. Neurosci. Methods 163, 1–8 (2007).

Fink, A. E. et al. Two-photon compatibility and single-voxel, single-trial detection of subthreshold neuronal activity by a two-component optical voltage sensor. PLoS ONE 7, e41434 (2012).

Klymchenko, A. S. & Kreder, R. Fluorescent probes for lipid rafts: from model membranes to living cells. Chem. Biol. 21, 97–113 (2014).

Lojewska, Z. & Loew, L. M. Insertion of amphiphilic molecules into membranes is catalyzed by a high molecular weight non-ionic surfactant. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 899, 104–112 (1987).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the Russian Science Foundation #24-15-00242.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: A.S.M. and D.A.S.; methodology, investigation, data analysis, and visualization: D.A.S.; writing original draft: D.A.S.; review and editing: A.S.M. and D.A.S.; project administration, funding acquisition, and supervision: A.S.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Martin Bootman, Francisco Javier Martin-Romero and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Kaliya Georgieva.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Antonov, S.M., Sibarov, D.A. Evaluation and experimental monitoring of calcium in plasma membrane inner nanoscale cytoplasm regions. Commun Biol 8, 1829 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09381-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09381-1