Abstract

Anti-CRISPR (Acr) proteins are natural inhibitors of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)–CRISPR-associated protein (Cas) systems, providing valuable tools for regulating genome editing. Here, we present the crystal structure of AcrIIA19, a plasmid-encoded Type II-A CRISPR-Cas system inhibitor that targets Cas9. AcrIIA19 adopts a previously uncharacterized fold and forms a stable homodimer. Biochemical assays revealed that AcrIIA19 binds selectively to the wedge (WED) domain of Cas9, a conserved structural interface critical for single guide RNA–DNA duplex stabilization and catalysis. This interaction disrupts Cas9 activity at multiple stages, independent of the order of complex assembly. Notably, AcrIIA19 exhibits broad-spectrum inhibition across divergent Cas9 orthologs, including Streptococcus pyogenes and Staphylococcus aureus Cas9, by exploiting a conserved WED domain vulnerability. Our findings establish AcrIIA19 as a versatile Cas9 inhibitor and highlight the WED domain as a strategic target for developing species-agnostic CRISPR regulatory tools in biotechnology and therapeutic applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

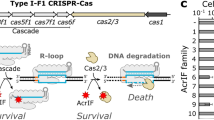

The clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)–CRISPR-associated protein (Cas) system provides adaptive immunity in bacteria and archaea by capturing fragments of foreign DNA and using them to guide RNA-directed nucleases that cleave invading genetic elements during subsequent infections1,2,3. Among the various CRISPR–Cas systems, Type II-A CRISPR–Cas from Streptococcus pyogenes has emerged as a powerful tool for genome editing due to its simple two-component system and robust programmable DNA cleavage activity4,5.

Cas9 is a multi-domain effector protein in the Type II CRISPR-Cas system that undergoes complex conformational transitions as it progresses through activation, DNA binding, and cleavage4,6. Cas9 initially recognizes a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) and then scans nearby DNA regions for sequences complementary to the guide RNA, enabling highly specific binding to the target site7. Binding to the target DNA triggers a conformational shift in Cas9 that activates its cleavage function by repositioning the HNH and RuvC nuclease domains. These allosteric changes are crucial for regulating catalytic activity of Cas98. Another central process of Cas9 functioning is the wedge (WED) domain, which connects the recognition (REC) and nuclease (NUC) lobes of Cas9, stabilizes the scaffold, and supports interactions with the single guide RNA (sgRNA)–target DNA duplex9,10.

To counteract CRISPR immunity, bacteriophages have evolved small inhibitory proteins known as anti-CRISPR (Acr) proteins, which function as molecular mimics or steric blockers to disable different types of CRISPR–Cas systems11. Since their initial discovery in 2013, approximately 100 distinct Acr proteins have been identified through a combination of functional assays and computational analyses12. Acr proteins exhibit remarkable mechanistic diversity. Some block the loading of sgRNA13, others prevent DNA recognition14, while a few inhibit the conformational changes necessary for cleavage15,16. Many Acr proteins are highly specific to a particular Cas ortholog and function at a defined stage of Cas9 activity17,18.

AcrIIA19 was identified in a bacterial plasmid as an anti-CRISPR protein exhibiting inhibitory activity against the Type II-A CRISPR-Cas system19. However, its structural features and precise mechanism of action remains unresolved. In the current study, we reported on the crystal structure of AcrIIA19 and revealed that it formed a homodimer in solution. Structural and biochemical analyses demonstrated that AcrIIA19 bound specifically to the WED domain of multiple Cas9 orthologs, thereby interfering with the distinct steps of the Cas9 functional cycle. This mode of inhibition was not limited to a single species, suggesting a broad-spectrum inhibitory mechanism that exploits a conserved structural interface. Unlike previously characterized Acr proteins with narrow specificity, AcrIIA19 showed broad inhibitory activity across divergent Cas9 orthologs, indicating that it targets a conserved structural feature within the WED domain. This finding enhances our understanding of the structural plasticity of Cas9 inhibition and highlights the WED domain as a conserved molecular vulnerability across Cas9 proteins from different species. Our results provide a framework for understanding Acr-mediated inhibition of Cas9 and may facilitate the development of engineered Acr proteins or small molecules to precisely control CRISPR-based genome-editing tools in biotechnology and therapeutic applications.

Results

High-resolution structural analysis of AcrIIA19 reveals a previously uncharacterized structural fold

To elucidate the inhibition mechanism of AcrIIA19, we began by overexpressing and purifying full-length AcrIIA19 protein from S. pseudintermedius for structural analysis. The purification workflow involved Ni-NTA affinity chromatography, followed by SEC. A well-defined peak was consistently observed during the SEC process and SDS-PAGE analysis confirmed that the protein corresponding to this peak was the 14 kDa AcrIIA19 protein (Fig. 1A). The main peak in the SEC profile eluted at approximately 16 mL, corresponding to a molecular weight between that of the protein standards ovalbumin (44 kDa) and myoglobin (17 kDa) (Fig. 1A, B). This observation indicates that AcrIIA19 likely existed as a dimer in solution. Crystallization trials were conducted using the protein fractions obtained from the major SEC peak, ultimately leading to successful crystal formation. Following successful crystallization, the structure of AcrIIA19 was solved at a 1.98 Å resolution using MR, with the AlphaFold2 model used as a search template. Details on crystallographic and refinement statistics are listed in Table 1.

A Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) profile of AcrIIA19. A representative image of an SDS-PAGE gel loaded with the main peak fractions is provided at the bottom of the profile. The corresponding SEC fractions analyzed by SDS-PAGE are indicated by black arrows. B The elution volume line fitting in SEC plotted against the size marker and logarithm of the molecular weight of AcrIIA19. The red point on the fitting line signifies the elution volume of AcrIIA19. C Four molecules of AcrIIA19 in the same crystallographic asymmetry unit (ASU). D Cartoon representation of the AcrIIA19 structure. The color of the chain from the N- to the C-termini gradually moves through the spectrum from blue to red. The secondary structures are labeled. E Topological representation of AcrIIA19. F Surface electrostatic potential of AcrIIA19. The respective surface electrostatic distributions are represented by a scale ranging from −7.0 kT/e (red) to +7.0 kT/e (blue). G B-factor distribution in the structure of AcrIIA19. The structure is presented in a putty representation. Spectrum colors from red to violet with increasing B-factor values were used for B-factor visualization. H Four superimposed AcrIIA19 structures in ASU. I Structural superimposition of the experimental structure of AcrIIA19 with predicted structure by AlphaFold2. The structurally different region that is not aligned is indicated by the black-dot box. J Table summarizing the results of a structural similarity search using the DALI server.

The crystal belonged to space group C2221 and contained four molecules (MolA to MolD) in the asymmetric unit (ASU; Fig. 1 C). The final structural model covered the complete AcrIIA19 (residues M1 to G115). The structure of AcrIIA19 consisted of five α-helices (α1–α5) and one β-sheet (Fig. 1D, E). Electrostatic potential analysis revealed that both negative and positive charges were distributed almost evenly across the surface of AcrIIA19 (Fig. 1F), making it difficult to infer a functional mechanism based on charge distribution alone. B-factor analysis showed relatively higher values at the N-terminus; however, the overall B-factor was low (average 48.8 Å), indicating that the structure was highly rigid (Fig. 1G). The observation that all four molecules in the same ASU exhibited nearly identical structures served as additional indirect evidence supporting the high structural stability of AcrIIA19 (Fig. 1H).

Following the successful completion of MR phasing using the predicted structural model generated by AF2, we sought to evaluate the structural similarity between the experimentally determined structure and predicted model. To this end, the two structures were superimposed for comparative analysis. Structural alignment of AcrIIA19 with the AF2 predicted model revealed a high degree of overall similarity, except for the N-terminal region. Specifically, the N-terminal β-sheet observed in the experimental structure was modeled as an extended loop in the AF2 prediction (Fig. 1I). The overall strong structural resemblance was likely a key factor that contributed to the successful MR phasing.

After analyzing the AcrIIA19 structure, we employed the DALI server20 to identify structurally similar proteins with characterized functions, thereby obtaining insights into the potential mechanism of action of AcrIIA19. This analysis revealed that prefoldin subunit 1 was the most structurally similar to AcrIIA19 (Fig. 1J). Although prefoldin subunit1 was identified as the closest structural match, its low Z-score (5.4) and sequence identity (11%) suggested limited structural similarity. Similarly, other candidate proteins exhibited low Z-scores (ranging from 5.0 to 5.3) and low sequence identities between 9 and 10%, collectively indicating that AcrIIA19 adopted a structural fold not previously reported.

AcrIIA19 forms a stable dimer in solution

While numerous Acr proteins have been reported to inhibit Cas9 activity as monomers, previous studies have shown that certain Acr proteins function as dimers21,22. In the case of AcrIIA19, SEC revealed a single prominent peak eluting between the 44 and 17 kDa molecular weight markers (Fig. 1A). However, since SEC alone is insufficient to determine precise stoichiometry, MALS analysis was performed. The MALS data yielded an experimental molecular weight of 32.7 kDa with a fitting error of 2.8% (Fig. 2A). Considering that the theoretical molecular weight of monomeric AcrIIA19, including the C-terminal 6×His tag, would be 13.5 kDa, these results clearly indicate that AcrIIA19 existed as a dimer in solution.

A Profile of multi-angle light scattering (MALS) analysis. The experimental MALS data (red line) plotted on the size exclusion chromatography (SEC) chromatogram (black) with the x-axis representing the SEC elution volume and y-axis representing the absolute molecular mass. Profile with blue-dot line indicates SEC profile monitored by UV absorbance at 280 nm. B Table summarizing the result of a Protein Interfaces, Surfaces and Assemblies (PISA) analysis. C Dimeric structure of AcrIIA19. The model shows two dimers formed by MolA/MolD and MolC/MolD. D Two superimposed dimer structures of AcrIIA19. E Superimposed experimentally determined dimers of AcrIIA19 with predicted dimer structure generated using AF2. F Protein–protein interaction (PPI) analysis of the AcrIIA19 dimer. Two major interaction interfaces are highlighted with black-dotted boxes. Close-up view of the MolA/MolB dimer first PPI (G) and second PPI (H) interfaces. Key residues contributing to the PPI are labeled. Residues involved in salt bridge formation are highlighted with red boxes.

To gain detailed insights into the dimerization of AcrIIA19, we analyzed the protein–protein interaction (PPI) interfaces using the Protein Data Bank Europe Protein Interfaces, Surfaces and Assemblies (PDBePISA) server20. The PISA complex formation score, which ranges from 0 to 1 with higher values indicating greater biological relevance, was 1.0 for both the AB and CD dimers. This suggests that these dimers may represent biologically relevant forms of AcrIIA19 in solution (Fig. 2B). Since the AB dimer and CD dimer represent essentially the same dimeric form (Fig. 2C, D), we selected the AB dimer as a representative structure to analyze in detail. In the AB dimer, the dimer buried surface area was 3126.5 Å2, representing 30.8% of total dimer surface area. Overall, 70 residues (60.3% of total AcrIIA19 residues) were involved in PPI (Fig. 2B). The PPI was formed by 38 hydrogen bonds (# of HB) and 8 salt bridges (# of SB) (Fig. 2B). To further validate the dimeric architecture of AcrIIA19, we employed AF2 to predict its dimeric form based on our experimentally derived structural information. The resulting model exhibited a high degree of similarity to our crystallographically determined dimer structure (Fig. 2E). This structural congruence supports the conclusion that the observed dimer represents the authentic dimeric form of AcrIIA19.

The dimerization occurred primarily in two distinct regions (Fig. 2F). The first involved interactions between the N-terminal regions composed of β1, α1, and α2 helices (Fig. 2G), and the second involved interactions between the C-terminal regions composed of α3, α4, and α5 helices (Fig. 2H). Salt bridges formed by residues K10, E43, R101, and E107 from each molecule were the primary forces maintaining the integrity of this dimeric interface. Additionally, residues N11, Y14, N31, Q35, T39, Y63, D67, T83, D84, Q86, K89, T91, and Y95 from each monomer were involved in forming massive H-bonds.

AcrIIA19 suppresses the DNA cleavage activity of Cas9, independent of reaction order

We established an in vitro Cas9-mediated DNA cleavage assay to assess its ability to directly inhibit Cas9 activity. We first employed SpyCas9 in our in vitro assay as AcrIIA19 was initially discovered as an inhibitor of SpyCas919. SpyCas9, a widely utilized nuclease in genome-editing applications, is a large protein composed of 1368 amino acid residues. For the cleavage assay, a 1100 base pair double-stranded DNA substrate containing a target site with the PAM sequence 5′-NGG-3′, which is recognized by SpyCas9, was used along with a synthetic sgRNA designed to direct SpyCas9 to the target region. As expected, formation of the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex through co-incubation of SpyCas9 and sgRNA resulted in efficient cleavage of the target DNA (Fig. 3A). However, a marked reduction in DNA cleavage was observed upon the addition of AcrIIA19, indicating its inhibitory effect on SpyCas9 activity (Fig. 3A). The inhibitory activity of AcrIIA19 was observed regardless of the order of component addition, whether AcrIIA19 was added after the formation of the Cas9-sgRNA complex or if it was pre-incubated with Cas9 prior to the sgRNA being introduced (Fig. 3A). These results suggest that AcrIIA19 inhibited SpyCas9 at multiple stages of its functional pathway.

A In vitro anti-CRISPR activity assay for detecting reaction order-dependent inhibition of SpyCas9 activity. The numbers indicate the order in which the samples were added to the enzyme reaction. Polyacrylamide gels (4%) were stained with SYBR GOLD. The experiments were performed three times with similar results. In the enzyme reaction, + and – indicate added and not added, respectively. B, C In vitro anti-CRISPR activity assay for detecting Acr concentration-dependent inhibition of SpyCas9 activity. Two sets of experiments were performed, one in which 33 nM of Cas9 was first incubated with 30 nM of sgRNA to form the RNP complex prior to assessing the effect of Acr (B), and another in which Acr was pre-incubated with Cas9 (33 nM) prior to the addition of sgRNA(30 nM) (C). The amount of AcrIIA19 added to the reaction is indicated. The numbers next to the agents used in the experiment indicate the order in which agents were added to the reaction. In the enzyme reaction, + and – indicate added and not added, respectively. In all assays in (A), (B), and (C), target DNA (2 nM) was added at the final step. The quantification results corresponding to panel A (D), panel B (E), and panel C (F) are presented. For quantification of target DNA cleavage by Cas9 and its inhibition by AcrIIA19, both the substrate and product band intensities from the gel were analyzed and expressed their ratio as the cleavage ratio. The experiments were performed independently three times (1st, 2nd, and 3rd) and the mean values with standard deviations are presented. The numbers on the X-axis correspond to the lane numbers shown below each gel in panels (A–C).

Next, to assess the concentration dependency of AcrIIA19 activity, we performed inhibition assays under the following two conditions: (1) AcrIIA19 added after Cas9-sgRNA complex formation (Fig. 3B) and (2) AcrIIA19 pre-incubated with Cas9 prior to sgRNA addition (Fig. 3C). In both cases, we tested AcrIIA19 at concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 5 μM. The results showed that AcrIIA19 inhibited Cas9 activity in a concentration-dependent manner under both conditions (Fig. 3B, C). Notably, when AcrIIA19 was present prior to RNP complex formation (i.e., added before the addition of sgRNA), nearly complete inhibition was observed at 2–5 μM, indicating that AcrIIA19 was more effective at inhibiting Cas9 activity when it interacted with Cas9 prior to sgRNA loading. To provide a clearer quantification of target DNA cleavage by Cas9 and its inhibition by AcrIIA19, we quantified both the substrate and product band intensities from the gel and expressed their ratio as the cleavage ratio. The quantification results corresponding to Fig. 3A–C are presented in Fig. 3D–F, respectively.

AcrIIA19 binds to Cas9 via the WED domain

Several mechanisms have been proposed for how Acr proteins inhibit Cas9 activity, including its direct binding to the target DNA, the sgRNA, or the Cas9 protein itself16,21,23,24,25,26,27. Previous immunoprecipitation assays have demonstrated that AcrIIA19 can directly bind to Cas919. Building on previous findings, the inhibitory mechanism of AcrIIA19 was further investigated using a binding assay that employed full-length SpyCas9. Considering that previous confirmation was based on immunoprecipitation assays performed in cells, we conducted our in vitro binding experiments by incubating purified SpyCas9 with AcrIIA19, followed by SEC. The results showed that in the presence of SpyCas9, the AcrIIA19 peak shifted to an earlier elution position, indicating complex formation (Fig. 4A). SDS-PAGE analysis further confirmed the co-migration of AcrIIA19 with SpyCas9, suggesting a direct interaction between the two proteins (Fig. 4A). To further validate this interaction, we performed a pulldown assay using untagged AcrIIA19 and 6×His tagged SpyCas9. The supernatant containing both proteins was subjected to Ni-NTA bead pulldown, and the presence of untagged AcrIIA19 co-eluted with the tagged SpyCas9 was examined by SDS–PAGE. The results showed that untagged AcrIIA19 co-eluted with SpyCas9, providing additional evidence for their direct binding (Fig. 4B).

A Interaction analysis between AcrIIA19 and SpyCas9 by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) followed by SDS-PAGE analysis. SEC profiles produced by AcrIIA19 (black line), SpyCas9 (blue line), and the mixture of AcrIIA19 and SpyCas9 (red line) are shown. The SDS-PAGE image was produced by loading and electrophoretically separating the main fractions from the mixture of SpyCas9 and AcrIIA19. The black arrow indicates the co-migrated AcrIIA19 with Cas9 proteins. M and I indicate Marker and Input sample. B Pull-down assay for detecting the interaction of 6×His tagged SpyCas9 with untagged AcrIIA19. The supernatant containing both proteins was subjected to Ni-NTA bead pulldown, and the presence of untagged AcrIIA19 co-eluted with the tagged protein was examined by SDS–PAGE. Protein bands on a 15% SDS-PAGE gel were detected using Coomassie blue staining. M: size marker, S: supernatant, P: pellet, F: flow-through, W: wash, and E: elution. C Domain organization of SpyCas9. The domain constructs generated from the pull-down assay are represented as black bars. D Pull-down assay interaction analysis between AcrIIA19 and each domain of SpyCas9. E SEC profiles produced by AcrIIA19 (black line), and the mixture of AcrIIA19 and the REC1-2 domain (red line) are shown. A representative image of SDS-PAGE analysis of the AcrIIA19 and REC1-2 domain mixture is provided under the SEC profile. Loaded fractions for SDS-PAGE are indicated by the black arrows. M and I indicate Marker and Input sample. F SEC profiles produced by AcrIIA19 (black line), WED domain (blue line), and the mixture of AcrIIA19 and WED domain (red line) are shown. A representative image of SDS-PAGE analysis of the AcrIIA19 and WED domain mixture is provided under the SEC profile. Loaded fractions for SDS-PAGE are indicated by the black arrows. M and I indicate Marker and Input sample. (G) Pull-down assay for detecting the interaction of untagged AcrIIA19 with various Cas9 orthologues from different species. + and – indicate added and not added, respectively. * indicated a control for the pulldown with no Cas9 but only the untagged AcrIIA19. (H) The bar graph shows the quantified intensity of co-eluted untagged AcrIIA19. Complex (%) represents the ratio of untagged AcrIIA19/Cas9 determined from the pulldown assay. The values were quantified using ImageJ by measuring the integrated band intensities of Cas9 and AcrIIA19 in the SDS-PAGE gel shown in panel (G). Complex (%) = (Integrated area of AcrIIA19 band)/(Integrated area of Cas9 band)× 100. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from three independent experiments (1st, 2nd, and 3rd). I in vitro anti-CRISPR activity assay of AcrIIA19 against SauCas9. Polyacrylamide gels (4%) were stained with SYBR GOLD. The numbers indicate the order in which the agents were added to the reaction. In the enzyme reaction, + and – indicate added and not added, respectively. J The quantification results corresponding to panel (I) are presented. For quantification of target DNA cleavage by Cas9 and its inhibition by AcrIIA19, both the substrate and product band intensities from the gel were analyzed and expressed their ratio as the cleavage ratio. The experiments were performed independently three times (1st, 2nd, and 3rd) and the mean values with standard deviations are presented. The numbers on the X-axis correspond to the lane numbers shown below the gel in panel (I).

To gain a more detailed understanding of the binding mechanism, additional experiments were performed using individual domains of SpyCas9. Considering that SpyCas9 comprises several distinct functional domains, namely the REC domain, HNH nuclease domain, WED domain, and PAM-interacting (PI) domain, various expression constructs were designed for use in in vitro pull-down assays. The PI domain was excluded from our pull-down assay as it was highly insoluble, making it difficult to obtain interpretable results. The results of these experiments showed that untagged AcrIIA19 was not pulled down by the REC1-2, REC3, or HNH domains, but was clearly pulled down by the WED domain. Although a small amount of AcrIIA19 appeared to co-elute with the REC1-2 domain, subsequent SEC analysis with the mixture of separately purified two proteins revealed no co-migration (Fig. 4E), suggesting that if any interaction existed, it was extremely weak and likely occurred with very low affinity. Regarding the WED domain, mixing the individually purified proteins and analyzing them by SEC revealed a peak shift along with co-migration on SDS-PAGE, confirming that AcrIIA19 bound strongly to the WED domain (Fig. 4F). Collectively, the binding assay results using full-length SpyCas9 and its individual functional domains strongly indicate that AcrIIA19 exerted its inhibitory effect through direct interaction with Cas9, notably by binding to the WED domain.

Several members of the AcrIIA proteins, including AcrIIA16, AcrIIA17, and AcrIIA28, exhibited broad-spectrum inhibition against multiple Cas9 orthologs16,19. To determine whether AcrIIA19 possesses a similar capability, we conducted pull-down assays to assess its interaction with various Cas9 proteins. The results revealed that AcrIIA19 bound to SpyCas9 and Cas9 from N. meningitidis (NmeCas9), H. parainfluenzae (HpaCas9), and SauCas9 (Fig. 4G, H). Therefore, we next examined whether AcrIIA19 could inhibit the activity of SauCas9. Indeed, AcrIIA19 was found to inhibit SauCas9-mediated DNA cleavage in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4I). These findings suggest that AcrIIA19 can function as a broad-spectrum Cas9 inhibitor, and that targeting the WED domain may allow for inhibition of various Cas9 orthologs without exhibiting species-specific restrictions.

Putative 2:2 stoichiometric complex model of AcrIIA19 and Cas9

Finally, to analyze and predict how the AcrIIA19 dimer binds to the WED domain of Cas9 and inhibits its function, we performed structural modeling of the AcrIIA19/Cas9 complex using AlphaFold328. The resulting model revealed that the AcrIIA19 dimer simultaneously interacts with the WED domains of two Cas9 molecules, forming a 2:2 complex (Fig. 5A).

A Complex structural model generated by AF3. B The raw profile of SEC-MALS. Assays are represented as black bars. UV and LS indicate ultraviolet and light scattering, respectively. C Profiles of MALS analysis (1st, 2nd, and 3rd peaks). The experimental MALS data (red line) plotted on the SEC chromatogram (black) with the x-axis representing the SEC elution volume and y-axis representing the absolute molecular mass.

To support the structural model suggesting that the AcrIIA19 dimer interacts with two Cas9 molecules, we performed additional SEC–MALS analyses using a mixture of AcrIIA19 and SpyCas9 proteins. The chromatogram showed three distinct peaks (Fig. 5B). MALS analysis indicated molecular masses of approximately 399.5 kDa (±2.7) for the first peak, 175.6 kDa (±2.9) for the second, and 50.6 kDa (±6.0) for the third peak (Fig. 5C). Considering that one Cas9 monomer has a molecular weight of 158.5 kDa and one AcrIIA19 monomer has 13.5 kDa, the first peak likely corresponds to a 2:2 complex (two Cas9 and two AcrIIA19 molecules), the second to a 1:2 complex (one Cas9 and two AcrIIA19 molecules), and the third to a dimeric AcrIIA19 alone. These results are consistent with our structural model and strongly support the hypothesis that the AcrIIA19 dimer can engage two Cas9 molecules simultaneously.

Discussion

In this study, we determined the crystal structure of AcrIIA19, an Acr protein originally discovered in a plasmid of S. pseudintermedius, and revealed its inhibitory mechanism against multiple Cas9 orthologs. Our findings demonstrate that AcrIIA19 exerted its inhibitory function by binding to the WED domain of Cas9. Additionally, we provide compelling evidence that the observed inhibition occurred at multiple stages of the Cas9 functional cycle.

Structural analysis revealed that AcrIIA19 adopted a previously uncharacterized fold, forming a symmetric homodimer stabilized by extensive hydrogen bonding and salt bridge networks. While most known Acr proteins function as monomers, our SEC-MALS and crystallographic data confirm that dimerization was an inherent feature of AcrIIA19, and likely crucial to its biological function. This dimeric architecture may offer functional advantages, such as an enhanced binding affinity or multivalent interactions with the WED domain of Cas9. Furthermore, the absence of significant structural homology to previously reported proteins indicates that AcrIIA19 represents a unique structural class within the Acr family, which may provide new scaffolds for synthetic inhibitor design.

Many Acr proteins inhibit Cas9 by blocking sgRNA loading (e.g., AcrIIC213), preventing DNA binding/cleavage (e.g., AcrIIA225, AcrIIA423, and AcrIIA529), and blocking the REC3 domain of Cas9. However, AcrIIA19 targets the WED domain, which is a critical structural interface that bridges the REC and NUC lobes of Cas9 and stabilizes sgRNA: DNA interactions. Our domain-specific pull-down and SEC assays provide clear evidence that AcrIIA19 bound to the WED domain, with negligible binding to other domains (REC1-2, REC3, or HNH). Considering the central role of the WED domain in orienting the nucleic acid duplex and facilitating conformational transitions essential for catalysis, AcrIIA19 binding may likely disrupt multiple steps in Cas9 activation, including RNP assembly and DNA cleavage.

Our in vitro cleavage assays revealed that AcrIIA19 effectively inhibited Cas9 activity, regardless of the temporal order of component addition. This feature contrasts with Acr proteins such as AcrIIC1, whose activity is dependent on blocking pre-RNP assembly stages13. This stage-independent inhibition suggests that AcrIIA19 binding to the WED domain may stabilize an inactive conformation or sterically hinder conformational transitions required for activation, reinforcing the idea that AcrIIA19 is able to act as a multi-step inhibitor, rather than being a binary blocker.

To date, over 40 distinct type II-targeting Acrs have been reported, the majority of which (around 30–35) act in a type-specific manner16,24,30,31. In contrast, a smaller subset (around 5) exhibit broad-spectrum inhibition across multiple Cas9 variants, including well-characterized inhibitors such as AcrIIA5, AcrIIA16, AcrIIA17, and AcrIIA1119,32,33. One of the most striking features of AcrIIA19 was its cross-reactivity toward multiple Cas9 orthologs, including SpyCas9, SauCas9, NmeCas9, and HpaCas9. This broad-spectrum inhibitory capacity sharply contrasts with the narrow specificity typically observed for Acr proteins, which often evolved to inhibit a single Cas variant. Our findings suggest that AcrIIA19 exploits a conserved structural vulnerability in the WED domain that is shared among diverse Cas9 orthologs. Considering the structural and evolutionary divergence of Cas9 proteins, the ability of AcrIIA19 to inhibit across species underscores the functional conservation of the WED domain and positions it as a strategic target for developing pan-Cas9 inhibitors. This broad activity profile has substantial implications for CRISPR regulation in biotechnology. AcrIIA19, or its engineered variants, could serve as off-switch tools in therapeutic genome editing applications that utilize multiple Cas9 systems. In contrast to PAM-specific or sequence-dependent Acr proteins, WED-targeting inhibitors such as AcrIIA19 may offer species-agnostic and context-independent control.

The newly provided characterization of AcrIIA19 adds to the growing repertoire of potential tools for precision modulation of CRISPR–Cas systems. As the demand for tightly regulated gene-editing systems grows, Acr proteins such as AcrIIA19 offer a promising strategy for enhancing safety by preventing off-target effects or enabling temporal regulation. Moreover, the structural insights provided in this study pave the way for rational design of Acr derivatives or small molecules that mimic AcrIIA19, targeting the WED domain to allosterically inhibit Cas9 activity.

Although the precise mechanism by which AcrIIA19 binding to the WED domain inhibits Cas9 activity remains unclear, our modeling study and SEC–MALS analysis of the AcrIIA19/Cas9 mixture demonstrated the possibility of forming a 2:2 complex (Fig. 5A–C). This potential 2:2 complex formation suggests an inhibitory mechanism in which dimeric AcrIIA19 induces Cas9 dimerization, thereby preventing target DNA from being recruited to the crRNA in Cas9, similar to the mechanisms previously proposed for AcrIIC321 and AcrIIA630.

While this study provides critical structural and functional insights, several questions remain. For instance, the atomic-resolution mechanism whereby WED domain binding disrupts Cas9 catalysis warrants further investigation using cryogenic electron microscopy or single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer to capture conformational states. Additionally, in vivo validation of AcrIIA19 activity across bacterial and eukaryotic systems would further substantiate its utility as a universal CRISPR regulator. Finally, determining whether AcrIIA19 exhibits any off-target effects or immunogenicity in host systems will be critical for therapeutic translation.

Materials and methods

Cloning, overexpression, and purification of AcrIIA19, Cas9 variants, and individual Cas9 domains

The full-length Staphylococcus pseudintermedius acrIIA19 gene, encoding amino acid residues 1–115 (GenBank accession no. WP_100006909.1), was synthesized by Bionics (Daejeon, Republic of Korea) and cloned into the pET21a expression vector (Novagen, Madison, WI, USA) using NdeI and XhoI restriction sites. The resulting recombinant plasmid was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells, which were cultured in 1 L of lysogeny broth supplemented with 50 µg/mL ampicillin at 37 °C. Upon reaching an optical density at 600 nm (OD₆₀₀) of approximately 0.8, the culturing temperature was lowered to 20 °C, and protein expression was induced with 0.25 mM isopropyl-β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside. The cells were then incubated for an additional 20 h at 20 °C to allow for expression of AcrIIA19. After incubation, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 2000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The cell pellet was resuspended in 25 mL of lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0) and 500 mM NaCl, and subsequently lysed by ultrasonication. The resulting lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was then incubated with nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) resin for 3 h to allow binding of His-tagged protein. The mixture was loaded onto a gravity-flow column (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), followed by washing with 50 mL of lysis buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins. The target protein was eluted using 3 mL of elution buffer comprising 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, and 250 mM imidazole. The eluted AcrIIA19 protein was further purified via size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) using a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) connected to an ÄKTA Explorer system (GE Healthcare). The column was pre-equilibrated with SEC buffer consisting of 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0) and 150 mM NaCl. Fractions corresponding to the AcrIIA19 peak were collected, pooled, and concentrated to 9.8 mg/mL for crystallization. Protein purity was confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis.

Expression constructs for S. pyogenes Cas9 (#62731), Neisseria meningitidis Cas9 (#71474), Haemophilus parainfluenzae Cas9 (#121540), S. muelleri Cas9 (#121541), and Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 (#101086) were obtained from Addgene (Watertown, MA, USA). To express individual protein domains, PCR amplification was performed using S. pyogenes Cas9 as a template. All PCR products were cloned into the pET21a vector using NdeI and XhoI restriction sites. All proteins were purified using the same method as that used to purify AcrIIA19.

Crystallization and X-ray diffraction data collection

AcrIIA19 was crystallized using the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method at 20°C. For each crystallization drop, 1 µL of protein solution (9.8 mg/mL in SEC buffer) was mixed with 1 µL of reservoir solution containing 0.1 M HEPES (pH 8.1) and 1.8 M ammonium acetate (NH₄CH₃CO₂), then equilibrated against 500 µL of the same reservoir solution. Optimal crystals typically formed within 8 d under these conditions. X-ray diffraction data were collected at −178°C using a BL-5C in-vacuum undulator beamline at the Pohang Accelerator Laboratory (Pohang, Republic of Korea). The diffraction data were processed and scaled using HKL2000 software, enabling subsequent structural analysis34.

Structure determination and refinement

The crystal structure of AcrIIA19 was solved by molecular replacement (MR) using the PHASER program within the PHENIX software suite35. A structural model predicted by AlphaFold2 (AF2) was used as the search model, facilitating successful MR-based phasing. Initial automated model building was performed using AutoBuild available in PHENIX, followed by iterative manual model correction and refinement using Coot36 and phenix.refine37. Model validation was conducted using MolProbity38 to assess structural quality, stereochemistry, and overall geometry. All structural figures and molecular representations were generated using PyMOL39.

Multi-angle light scattering (MALS) analysis

The absolute molecular massed of AcrIIA19 and AcrIIA19/SpyCas9 mixture in solution were determined using SEC coupled with MALS (SEC-MALS). Purified AcrIIA19 protein was loaded onto a 24 mL Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated with SEC buffer and operated at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. The mixture of purified AcrIIA19 and SpyCas9 was loaded onto a 24 mL Superose 6 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated with SEC buffer and operated at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. The SEC-MALS experiments were conducted at 20°C using a DAWN-TREOS multi-angle light scattering detector (Wyatt Technology, Santa Barbara, CA, USA) integrated with an ÄKTA Explorer chromatography system (GE Healthcare). Bovine serum albumin was used as a reference standard to validate the accuracy of the molecular weight measurements. All data were processed and analyzed using ASTRA software (Wyatt Technology), allowing for the precise calculation of absolute molecular weight and polydispersity of the protein samples.

in vitro anti-CRISPR activity assay

A series of in vitro DNA cleavage assays were performed to assess the inhibitory effects of wild-type AcrIIA19 on Cas9-mediated target DNA cleavage. SpyCas9 and S. aureus Cas9 (SauCas9) enzymes were obtained from New England Biolabs (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA), and corresponding sgRNAs were synthesized in vitro using a HiScribe™ T7 Quick High Yield RNA Synthesis Kit (NEB).

Cas9 proteins (33 nM) were preincubated with their respective sgRNAs (30 nM) in NEBuffer r3.1 (NEB) at 20°C for 15 min to allow ribonucleoprotein complex formation. Subsequently, AcrIIA19 (0, 0.5, 1, 2, or 5 \(\mu\)M) was added to the reaction mixture and incubated for an additional 15 min at 20 °C. Target DNA (2 nM) was then introduced, and the reaction proceeded at 37 °C for 30 min. Cas9 proteins (33 nM) were also preincubated with AcrIIA19 (0, 0.5, 1, 2, or 5 \(\mu\)M) first for 15 min followed by the addition of generated sgRNAs (30 nM) in NEBuffer r3.1 (NEB), which were then incubated for an additional 15 min at 20 °C. Then, target DNA (2 nM) was introduced, and the reaction allowed to proceed at 37 °C for 30 min. Reactions were terminated by the addition of 10 µg proteinase K, followed by a 10 min incubation at 4 °C to degrade proteins. The resulting DNA products were separated by electrophoresis on 4% polyacrylamide gels and stained with SYBR GOLD to visualize DNA cleavage patterns. Gel images were analyzed to quantify and compare the inhibitory effects of AcrIIA19 on Cas9-mediated DNA cleavage.

SEC assay for analyzing complex formation

SEC was employed to investigate complex formation between AcrIIA19 and various Cas9 proteins or individual Cas9 domains. Briefly, AcrIIA19 was mixed with each full-length Cas9 protein or specific Cas9 domains and incubated at 4 °C for 1 h to allow complex assembly. The mixtures were subsequently loaded onto a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated with SEC buffer containing 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0) and 150 mM NaCl. Chromatographic profiles were recorded and fractions corresponding to elution peaks of interest were collected for further analysis. Collected fractions were analyzed using SDS-PAGE then stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. The migration and co-migration patterns of protein bands were examined to assess physical interactions and complex formation between AcrIIA19 and the respective Cas9 proteins or Cas9 domains.

Pulldown assay for analyzing complex formation

Pulldown assays were conducted to assess complex formation between AcrIIA19 and various Cas9 proteins as well as AcrIIA19 and individual Cas9 domains. Each E. coli strain expressing the target proteins for pulldown was transformed and cultured separately. After growth, the bacterial cells were combined and subjected to centrifugation to obtain a mixed cell pellet. The pellet was resuspended in 50 mL of lysis buffer (as used for protein purification), followed by sonication to lyse the cells. The lysate was then centrifuged to separate the supernatant from the cell debris. Supernatants containing untagged AcrIIA19 and full-length 6×His tagged Cas9 proteins or 6×His tagged Cas9 domains were supplemented with Ni-NTA resin and incubated for an additional 2 h at 4 °C to allow the binding of His-tagged proteins. The resin-protein complexes were then transferred into gravity-flow columns (Bio-Rad) and washed with 100 mL of lysis buffer to remove unbound proteins. Bound complexes were eluted with 1 mL of elution buffer containing 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, and 250 mM imidazole. The eluates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and visualized by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining. Protein migration and co-migration patterns were carefully examined to evaluate the interaction between AcrIIA19 and the Cas9 proteins or Cas9 domains.

Prediction of the SpyCas9-spAcrIIA19 complex

The structure model of the SpyCas9/spAcrIIA19 complex was predicted using AlphaFold328. The amino acid sequences of SpyCas9 and spAcrIIA19 were entered in the entity fields, and each entity was modeled with two copies (SpyCas9:spAcrIIA19 = 2:2) to account for potential dimeric interactions. All other parameters, including random seeds and model presets, were automatically assigned by the program. Among the generated models, the top-ranked prediction based on the AlphaFold confidence score (pLDDT, ipTM, and pTM) was selected for further analysis. The resulting complex structure was visualized and analyzed using PyMOL.

Statistics and reproducibility

All Acr activity and Cas9 binding assays were performed independently at least three times (n = 3) with similar results. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The coordinate and structural factors have been deposited in the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics (RCSB) Protein Data Bank (PDB) under the PDB code 9WA8. Uncropped original gels are provided at the Supplementary Fig. 1. The raw data for quantification analysis for Acr activity and Cas9 binding assays are provided in Supplementary Data 1.

References

Barrangou, R. et al. CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science 315, 1709–1712 (2007).

Sorek, R., Kunin, V. & Hugenholtz, P. CRISPR–a widespread system that provides acquired resistance against phages in bacteria and archaea. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 6, 181–186 (2008).

Hille, F. et al. The biology of CRISPR-Cas: Backward and forward. Cell 172, 1239–1259 (2018).

Jinek, M. et al. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 337, 816–821 (2012).

Doudna, J. A. & Charpentier, E. Genome editing. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science 346, 1258096 (2014).

Le Rhun, A., Escalera-Maurer, A., Bratovic, M. & Charpentier, E. CRISPR-Cas in streptococcus pyogenes. Rna Biol. 16, 380–389 (2019).

Josephs, E. A. et al. Structure and specificity of the RNA-guided endonuclease Cas9 during DNA interrogation, target binding and cleavage. Nucleic Acids Res 44, 2474 (2016).

Dagdas, Y. S., Chen, J. S., Sternberg, S. H., Doudna, J. A. & Yildiz, A. A conformational checkpoint between DNA binding and cleavage by CRISPR-Cas9. Sci. Adv. 3, eaao0027 (2017).

Nishimasu, H. et al. Crystal structure of Cas9 in complex with guide RNA and target DNA. Cell 156, 935–949 (2014).

Nishimasu, H. et al. Crystal structure of staphylococcus aureus Cas9. Cell 162, 1113–1126 (2015).

Bondy-Denomy, J., Pawluk, A., Maxwell, K. L. & Davidson, A. R. Bacteriophage genes that inactivate the CRISPR/Cas bacterial immune system. Nature 493, 429–U181 (2013).

Davidson, A. R. et al. Anti-CRISPRs: Protein inhibitors of CRISPR-Cas systems. Annu Rev. Biochem 89, 309–332 (2020).

Thavalingam, A. et al. Inhibition of CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complex assembly by anti-CRISPR AcrIIC2. Nat. Commun. 10, 2806 (2019).

Kim, D. Y., Lee, S. Y., Ha, H. J. & Park, H. H. AcrIE7 inhibits the CRISPR-Cas system by directly binding to the R-loop single-stranded DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 122, e2423205122 (2025).

Harrington, L. B. et al. A broad-spectrum inhibitor of CRISPR-Cas9. Cell 170, 1224–1233.e1215 (2017).

Kim, G. E. & Park, H. H. AcrIIA28 is a metalloprotein that specifically inhibits targeted-DNA loading to SpyCas9 by binding to the REC3 domain. Nucleic Acids Res 52, 6459–6471 (2024).

Lee, J. et al. Potent Cas9 Inhibition in Bacterial and Human Cells by AcrIIC4 and AcrIIC5 Anti-CRISPR Proteins. mBio 9, https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.02321-18 (2018).

Sun, W. et al. Structures of Neisseria meningitidis Cas9 complexes in catalytically poised and anti-CRISPR-inhibited states. Mol. Cell 76, 938–952.e935 (2019).

Mahendra, C. et al. Broad-spectrum anti-CRISPR proteins facilitate horizontal gene transfer. Nat. Microbiol 5, 620–629 (2020).

Holm, L. & Sander, C. Dali: a network tool for protein structure comparison. Trends Biochem. Sci. 20, 478–480 (1995).

Zhu, Y. et al. Diverse mechanisms of CRISPR-Cas9 inhibition by type IIC anti-CRISPR proteins. Mol. Cell 74, 296–309.e297 (2019).

Kim, G. E. et al. Molecular basis of dual anti-CRISPR and auto-regulatory functions of AcrIF24. Nucleic Acids Res 50, 11344–11358 (2022).

Dong, D. et al. Structural basis of CRISPR-SpyCas9 inhibition by an anti-CRISPR protein. Nature 546, 436–439 (2017).

Yang, H. & Patel, D. J. Inhibition mechanism of an anti-CRISPR suppressor AcrIIA4 targeting SpyCas9. Mol. Cell 67, 117–127.e115 (2017).

Liu, L., Yin, M., Wang, M. & Wang, Y. Phage AcrIIA2 DNA mimicry: Structural basis of the CRISPR and Anti-CRISPR arms race. Mol. Cell 73, 611–620.e613 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Structural basis for anti-CRISPR repression mediated by bacterial operon proteins Aca1 and Aca2. J. Biol. Chem. 297, 101357 (2021).

Sun, W. et al. Anti-CRISPR AcrIIC5 is a dsDNA mimic that inhibits type II-C Cas9 effectors by blocking PAM recognition. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, 1984–1995 (2023).

Abramson, J. et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 630, 493–500 (2024).

Song, G. et al. AcrIIA5 inhibits a broad range of Cas9 orthologs by preventing DNA target cleavage. Cell Rep. 29, 2579–2589.e2574 (2019).

Fuchsbauer, O. et al. Cas9 allosteric inhibition by the anti-CRISPR protein AcrIIA6. Mol. Cell 76, 922–937.e927 (2019).

Liu, H., Zhu, Y., Lu, Z. & Huang, Z. Structural basis of Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 inhibition by AcrIIA14. Nucleic Acids Res 49, 6587–6595 (2021).

Choudhary, N. et al. A comprehensive appraisal of mechanism of anti-CRISPR proteins: an advanced genome editor to amend the CRISPR gene editing. Front Plant Sci. 14, 1164461 (2023).

Dillard, K. E. et al. Mechanism of Cas9 inhibition by AcrIIA11. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaf318 (2025).

Otwinowski, Z. DENZO data processing package. (Yale University, 1990).

McCoy, A. J. Solving structures of protein complexes by molecular replacement with Phaser. Acta Crystallogr D. Biol. Crystallogr 63, 32–41 (2007).

Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D. Biol. Crystallogr 60, 2126–2132 (2004).

Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D. Biol. Crystallogr 66, 213–221 (2010).

Chen, V. B. et al. MolProbity: All-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D. Biol. Crystallogr 66, 12–21 (2010).

DeLano, W. L. & Lam, J. W. PyMOL: A communications tool for computational models. Abstr. Pap. Am. Chem. S 230, U1371–U1372 (2005).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the 5 C beamline staff of the Pohang Accelerator Laboratory (Pohang, Korea) for their assistance during data collection. This study was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (RS-2025-02316334 and RS-2025-16065724).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.H.P. designed the research and supervised the project. G.E.K. expressed and purified the proteins and performed crystallization and structure determination. G.E.K. and S.Y.L. conducted biochemical and EMSA experiments. S.Y.L. and Y.J.K. performed structural prediction and MALS analysis. H.B.J. assisted with structural determination. H.H.P., G.E.K., and S.Y.L. interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Tomas Sinkunas, Yuvaraj Bhoobalan-Chitty and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Joanna Timmins and Laura Rodriguez Perez. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, G.E., Lee, S.Y., Kang, Y.J. et al. AcrIIA19 binds to the WED domain and inhibits various Cas9 orthologs at multiple stages. Commun Biol 9, 136 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09417-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-09417-6