Abstract

Aliphatics prevail in asteroids, comets, meteorites and other bodies in our solar system. They are also found in the interstellar and circumstellar media both in gas-phase and in dust grains. Among aliphatics, linear alkanes (n-CnH2n+2) are known to survive in carbonaceous chondrites in hundreds to thousands of parts per billion, encompassing sequences from CH4 to n-C31H64. Despite being systematically detected, the mechanism responsible for their formation in meteorites has yet to be identified. Based on advanced laboratory astrochemistry simulations, we propose a gas-phase synthesis mechanism for n-alkanes starting from carbon and hydrogen under conditions of temperature and pressure that mimic those found in carbon-rich circumstellar envelopes. We characterize the analogs generated in a customized sputter gas aggregation source using a combination of atomically precise scanning tunneling microscopy, non-contact atomic force microscopy and ex-situ gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Within the formed carbon nanostructures, we identify the presence of n-alkanes with sizes ranging from n-C8H18 to n-C32H66. Ab-initio calculations of formation free energies, kinetic barriers, and kinetic chemical network modelling lead us to propose a gas-phase growth mechanism for the formation of large n-alkanes based on methyl-methylene addition (MMA). In this process, methylene serves as both a reagent and a catalyst for carbon chain growth. Our study provides evidence of an aliphatic gas-phase synthesis mechanism around evolved stars and provides a potential explanation for its presence in interstellar dust and meteorites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Extraterrestrial organic matter found in meteorites may hold a unique record of its synthesis, chemical, and thermal alterations in the parent body, and processes within the nebular and presolar environments1,2. Several classes of compounds, including amino acids, carboxylic acids, hydroxy-carboxylic acids, sulfonic acids, phosphonic acids, aromatic hydrocarbons, fullerenes, and heterocycles, as well as carbonyl compounds, alcohols, amines, and amides have been identified in carbonaceous chondritic meteorites3,4,5. Additionally, aliphatic compounds, especially large n-alkanes, have been systematically detected6,7,8. In 1967, a survey of thirty meteorites revealed in all of them the presence of n-alkanes in varying amounts, typically in the range of 10-100 parts per billion (ppb)6. These compounds exhibit monomodal distributions with peaks between n-C10H22 and n-C31H64, with no clear predominance of odd over even carbon numbers. It is worth noting that, given the uncertainty surrounding the mechanism responsible for their production, concerns regarding the potential introduction of terrestrial contaminants have arisen in the literature. In particular, it was suggested that they may have been added to the indigenous meteoritic material through physical contact with other samples or by atmospheric transport from fossil hydrocarbons9.

Nevertheless, the presence of hydrocarbons, and in particular of aliphatics, in space and meteorites has been the subject of vigorous research in recent years and aliphatics are now recognized as significant components of interstellar dust grains. They are detected in mid-IR emission of red giants, post-AGB sources, and planetary nebula by their 3.4 µm band and ~8 µm and ~12 µm plateaus10,11,12,13. In the solar system, aliphatics have been observed on comets14 and C-type asteroids15, both by space missions and sample return jobs16,17,18. Even the highly processed surface of the dwarf planet Ceres contains traces of aliphatics19. There is also direct experimental evidence of the presence of linear n-alkanes in asteroids before their entrance into the Earth’s atmosphere. Mass spectrometry measurements have confirmed the presence of methane (CH4), ethane (C2H6), propane (C3H8), butane (n-C4H10), pentane (n-C5H12), hexane (n-C6H14) and heptane (n-C7H16) in the coma of the comet 67 P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko20.

Also, reports on newly fallen meteorites that show minimal signs of terrestrial weathering have consistently found aliphatics, and in particular n-alkanes, as a predominant component of their organic content. A 2015 report revealed that the Paris meteorite contained 7670 parts per billion (ppb) of n-alkanes in the n-C16H34 to n-C25H52 range. The absence of common terrestrial hydrocarbon signatures was used as evidence of their indigenous nature7. More recently, experiments on the Aguas Zarcas meteorite, considered to be pristine due to its rapid collection after fall in April 2019, provided an opportunity to study an organic-rich meteorite with minimal terrestrial residence and little contamination21. Univocal identification of n-alkanes ranging from n-C12H26 to n-C18H38 was achieved, with some tentative detection up to n-C32H66 also suggested21. Notably, particles retrieved by Hayabusa2 spacecraft from the Ryugu asteroid have provided exceptionally pure and unaltered extraterrestrial material, showcasing a prevalence of hydrogen-rich aliphatic organics with CH2:CH3 ratios as high as 1,922,23. Interestingly, isotopic analysis of some of these aliphatic grains showed exceptional deuterium, nitrogen-15, and/or carbon-13 enrichment/depletions24, which pointed to a more primitive origin of the aliphatic material compared with other grains in their surroundings23. These results hint at the possibility that aliphatics in Ryugu may have originated from precursor molecules synthetized before the formation of the Solar System22.

Despite all the evidence on the presence of aliphatics and large n-alkanes in meteorites, comets, asteroids, and dust grains, their origin is still uncertain, and mechanisms accounting for their extraterrestrial origin are a matter of debate. Models proposing that n-alkanes may have been produced abiotically by a Fischer-Tropsch-like reaction have been invoked25. Such heterogeneous catalytic reaction involves the production of hydrocarbon chains from carbon monoxide and hydrogen on the surfaces of mineral catalysts. Problems with this hypothesis started to rise when evidence showed that the necessary catalysts and temperature-pressure conditions were absent in the early solar nebula26,27,28. More recent results, however, have demonstrated that Fischer-Tropsch-like mechanism may account for the production of some complex organics in other astrophysical environments29,30,31,32,33,34. Another proposed mechanism is the photolysis from methane-rich ices. This process has been demonstrated efficient in the synthesis of n-alkanes up to n-C14H3035,36. These experiments are performed by irradiating CH4 ices at very low temperatures in ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions, thus mimicking cold molecular clouds and the first stages of protoplanetary disc formation. Recently, astrochemical laboratory experiments based on sputter gas aggregation sources (SGAS) have found that non-aromatic carbonaceous material forms efficiently in conditions similar to the ones present in circumstellar envelopes of C-rich evolved stars37. It has been suggested that aliphatic hydrocarbons can efficiently grow in the gas phase and on the surface of small carbon grains, thus opening new ways for studying n-alkane synthesis in the interstellar medium and circumstellar shells38.

Here, we propose an alternative mechanism for the origin of n-alkanes and other aliphatics. The mechanism is based on sequential gas-phase methyl-methylene addition (MMA) growth of carbon chains. A combination of experimental and theoretical results demonstrates that, when atomic carbon comes into contact with molecular hydrogen at temperatures and densities comparable to those reported in the condensation zone of circumstellar envelopes (see Supp. Figure 2 for detailed physicochemical initial hypothesis)37, C and H atoms interact to produce methyl and methylene radicals38. These radicals undergo further polymerization through radiative association and thermalization, often facilitated by collisions with other species, resulting in the formation of large n-alkanes. Significantly, such a process occurs without the need for seeds or catalysts.

Results

The working principle of our experiments is the Ar+ sputtering of a graphite target operating in an SGAS, which induces atomic vaporization of C atoms from a graphite target into an UHV system, and their subsequent aggregation in a hydrogen atmosphere. We estimate the partial densities to be nH2 = 1.5x1010 molecules cm-3 and nC = 2.5 × 1010 atoms cm-3 in an Ar buffer atmosphere of nAr > 1013 atoms cm-3. The gas temperature during aggregation is around 500–1000 K (see methods and Supp. Fig. 2 for further details on the experimental conditions)37,39,40. The synthesized molecules, clusters, and nano-sized carbonaceous species are collected on ultra-clean, atomically flat substrates and characterized by scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) and non-contact atomic force microscopy (nc-AFM). Analogs for ex-situ gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) were grown using a higher dose of H2 (1012 molecules cm-3), increasing the reaction yield while preserving the aliphatic nature of the analogs37,38. The results are confronted with ab-initio density functional theory (DFT) and chemical kinetics calculations permitting us to establish a sound molecular growth mechanism.

Atomic scale characterization of the analogs with scanning probe microscopy

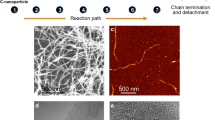

Figure 1a–c presents atomic-scale STM images recorded at 4.3 K of the aliphatic analogs collected on an inert Au(111) surface. STM is a valuable tool for characterizing carbonaceous molecules on surfaces41,42,43. Fig. 1a shows that the surface is covered by many molecular species, which are difficult to ascribe to particular chemical species. Self-ordered domains are resolved within the carbon mantle, indicating selective intermolecular attractive interactions. On the left part of Fig. 1a, we notice domains of self-assembled molecular dimer- and trimer-like structures, which have been previously reported37. In addition, close inspection of the flat areas, e.g., in Fig. 1b, reveals a different class of self-assembled domains consisting of 2D crystallites of parallel linear structures presenting low topographic corrugation. The domains cover approximately 20% of the surface, have an apparent height of 1.5 Å, and exhibit an interline spacing of 5 Å. Chains are aligned with the high symmetry direction of the Au(111) surface and weakly interact with the substrate and with neighboring chains (see Supp. Fig. 3). High-resolution images obtained at high tunneling currents (see Fig. 1c) show an intramolecular wiggling pattern with a periodicity of 2.5 ± 0.1 Å (see Fig. 1e), compatible with the CH2-CH2 bond distance in alkanes (see STM simulations in Supp. Fig. 6)44 or the CH-CH bond distance of polyacetylene in trans-configuration45. The intermolecular distance and molecular orientation of the self-assembled domains observed in the STM images resemble the ones reported for n-alkanes on Au(111)46,47, yet chemical identification is difficult to ascertain based only on STM images.

a Large-scale STM micrograph of C-analogs condensed on Au(111) surface. The substrate is chosen to permit efficient tunneling conditions while preserving the intrinsic C-analog properties due to the low reactivity of gold surfaces toward molecular adsorbates. The STM parameters are 14 × 14 nm2, V = 1.4 V, I = 10 pA. b Detail of the 2D crystallites found within the C-analog condensed region, 7 × 7 nm2, V = 1.4 V, 20 pA. c High-resolution image of the linear structures. A wiggling intramolecular resolution is observed in the tunnel channel. 2 × 2 nm2, V = 1.5 V, I = 0.5 nA. d Histogram of the length distribution of the C-chains. The events have been binned by 1.2 Å, which corresponds to the CH2–CH2 distance in the aliphatic chains. Therefore, the number of events per channel corresponds to the number of molecules measured for a particular carbon length. The number of chains inspected is 232. The yellow-marked part of the histogram represents the range in which alkanes with small sizes do not efficiently adsorb on Au(111) due to a low sticking coefficient. e Profile obtained from the image shown in panel d, following the black dashed line. The periodicity of the wiggling pattern within the chains is 2.5 Å.

To unambiguously determine the chemical structure of the C-chains we have performed constant-height non-contact atomic force microscopy measurements. Bond-resolved nc-AFM is a powerful tool for the identification of unknown hydrocarbons48,45. The chemical structure of individual planar molecules and even the bond order (i.e., single vs. double or triple bonds) between atoms can be resolved, and the species identified by visual inspection of the images49,50,51. n-Alkanes and polyynes (both linear and ring-shaped) have been characterized, and the intramolecular zig-zag structure of sp3 alkanes has been distinguished from the linear backbone of sp-bonded polyynes52,53,54. Recently, nc-AFM has been used to atomically identify astrochemical analogs of Titan organic haze43 and organics from the Murchinson meteorite55, demonstrating the use of this technique for understanding the chemical routes operating on cosmic dust at the atomic level. In Fig. 2, we present our nc-AFM results. The frequency shift map in Fig. 2b shows a bond-resolved image of the chains in Fig. 2a, which allows for determining the zig-zag pattern of n-alkanes. It univocally discloses the presence of n-alkanes of three distinct lengths: decane (n-C10H22), undecane (n-C11H24), and pentadecane (n-C15H32). Figure 2c shows a ball-and-stick model of the molecules found in the 2.6 x 1.7 nm2 image shown in Fig. 2b. Other nc-AFM measurements show the presence of other alkanes with larger lengths (see Supp. Fig. 4). Thus, nc-AFM confirms the n-alkane nature of the self-assembled chain domains identified in STM images.

a Constant-height STM current image of a surface region where three chains are resolved 1.7 ×2.6 nm2 (V = 0.01 V). b Constant-height bond-resolved nc-AFM frequency shift image obtained simultaneously with the STM image shown in a. Regulated at 0.01 V and 20 pA, at the central lobe molecule at constant amplitude of ~50 pA. c Ball-and-stick schematic model of the molecular configuration unambiguously resolved in b. Three small aliphatic chains, a decane (n-C10H22), an undecane (n-C11H24), and a pentadecane (n-C15H32) are present in the small area inspected by nc-AFM.

In the next step, we determine the carbon number distribution of the n-alkanes by measuring their size individually in STM images and plotting their distribution as a function of length. Figure 1d presents the resulting histogram where 232 chains have been analyzed. Several conclusions can be drawn: (i) we notice the absence of C-chains with less than six atoms (yellow region in Fig.1d), which may be due to the low sticking coefficient of small alkanes on Au(111) at the deposition temperature (300 K)56. (ii) Chains longer than n-C37H76 are also absent, which points towards a self-limiting growth process44. (iii) The histogram presents a global maximum at n-C24H50 and two other local maxima at n-C15H32 and n-C32H66. (iv) There is no clear dominance of odd/even species. However, the limited statistics of the atomic-scale approach call for analytical methods that permit further corroborating these observations with higher statistical relevance.

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry measurements

In Fig. 3a, we show gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) results of the carbon analogs. Chromatographic and mass spectrometric parameters were optimized to maximize separation and sensitivity. Under these conditions, alkanes were detected as narrow and symmetrical peaks, approximately between 15 and 30 min of retention time. The main species observed are n-alkanes between n-C22H46 and n-C32H66, in good agreement with the results obtained by scanning probe measurements. In addition, GC-MS results permit quantifying the alkane chain distribution independently. The most frequent molecular chain is n-C26H54, a value close to the one found in the STM analysis. Besides, GC-MS shows low branching of alkanes in the analogs, as revealed by small peaks between those corresponding to n-alkanes. Based on their retention indices and mass spectra, these can be assigned to 2-methyl and 3-methyl alkanes. Close inspection of our STM images (Fig. 1b) also reveals the presence of small rounded features in some of the chains that can be readily assigned to branched methyl groups on these species (see Supp. Fig. 3).

a Representative GC-MS chromatogram for the acetonitrile extract of the compounds deposited on silicon. The selected ion chromatogram for m/z 57, 71, and 85 shows a series of peaks, identified as linear alkanes on the basis of their retention indices and mass spectra. The bell-shaped distribution of peaks is a result of its relative composition, with hexacosane (n-C26H54) as the most abundant compound. b The single ion GC-MS traces (m/z = 57) of the CH2Cl2/CH3OH extracts of the Aguas Zarcas meteorite. Linear aliphatic hydrocarbons (n-alkanes) ranging from C22 to C32 are found. The most abundant n-alkane is hexacosane (n-C26H54). Reproduced with permission from S. Pizzarello et al.21. c Presence of n-alkanes in meteorites according to the literature. Refs. 3,6,7,9,21,25,57,80,81. The (tentatively) identified species are marked with (white) black circles. When provided, the peak of the distribution is also introduced as a red circle.

GC-MS results also permit us to compare our analogs with extraterrestrial samples from meteorites (Fig. 3c). Various distributions for different samples featuring a peak between C14H30 and C26H54 are observed, with the longest chain ranging between C33H68 and C21H44, and the shortest chain between C8H18 and C19H40. These results align with the range observed in our MMA analogs. To illustrate the similarity in n-alkane distribution between our analogs and those in some carbonaceous chondrites, we present in Fig. 3b GC-MS measurements of the Aguas Zarcas meteorite from Pizzarello et al.21, a carbonaceous chondrite providing a pristine remnant of the early Solar System. Despite their radically different origins, both samples show qualitative chemical similarities. Both chromatograms contain a series of n-alkanes between n-C22H46 and n-C32H66, with their maximum at n-C26H54, and low branching. Several other meteorites show similar distributions according to the literature. In Fig. 3c we present such a comparison. Although their shortest and longest carbon chains and maximum intensity appear displaced compared to Aguas Zarcas (see Fig. 3c), the similarities are evident57. The main differences between our laboratory astrochemistry analogs and specific meteoritic samples can be explained by two main factors: i) Variations in physicochemical conditions during analogs growth, such as plasma temperature, total pressure or partial atomic densities (i.e.[C],[H] and [H2])during MMA growth and ii) collisions with third bodies and/or high energy photons which account for destruction of long chains and formation of new molecules through radical chemistry. This second factor may particularly account for the peaks appearing in the GC-MS of meteorites which have inevitably undergone weathering and processing effects.

Kinetic modeling and density functional theory simulations

To establish an alkane growth mechanism compatible with our experimental observations, we have modeled several gas-phase reaction paths in conditions similar to those found in our experiments. Our SGAS produces C species37 that react with atomic and molecular hydrogen in an Ar atmosphere (initial conditions nAr = 1018 cm-3, nC = nH2 = 1010 cm-3 and nH = 109 cm-3). Atomic hydrogen is produced by H2 dissociation in the sputter source. We estimate that 10% of the injected H2 reaches the magnetron head, being therefore susceptible to dissociation. Amongst other products, the gas-phase reactions produce methylene (CH2), methyl (CH3), and ethyl (C2H5) radicals, (see Supp. Note 1) which trigger the hydrocarbon alkane growth.

Kinetics modeling permits us to quantify the formation of these radicals and track the evolution of the chemical composition of the reactants and products. In Fig. 4 a, we present calculations depicting the evolution of the densities of C, H, H2, CH2, CH3, and C2H5 at a temperature of 500 K in our best-fit model. We first examine the synthesis of methylene (CH2) radicals. Methylene synthesis may proceed through radiative association, bimolecular association, or thermalization with a third body, such as an Ar atom. Given the relatively high density of Ar in our experiment, this is an efficient mechanism taking place within the lifetime of intermediate species (see supplementary note 2 for details on the transition states). In a similar way, reactions producing methyl radicals (CH3) efficiently deplete C, H, and H2 concentrations during the early stages of chemical evolution. Together, the formation of methyl and methylene radicals rapidly consume C and H, leading to a significant decrease in their abundances, often by several orders of magnitude, as seen in our simulations (Fig. 4a).

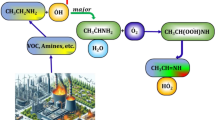

a Calculations on the evolution of the C, H, H2, CH2, CH3, and C2H5 densities at a temperature of 500 K (initial conditions nAr = 1018 cm-3, nC = nH2 = 1010 cm-3, and nH = 109 cm-3) from the kinetic chemical model introduced in the main text. b Schematics of the methyl-methylene addition mechanism producing alkanes in gas-phase. The reaction originates with a methyl radical, which sequentially incorporates methylene radicals. The chain growth finishes when either a hydrogen atom (H) is captured by a terminal CH2 or a methyl group (CH3) is attached to close the chain. c. Computed theoretical energy variation diagram, in eV, along the minimum reaction path, which also includes transition state energy barriers between each reaction step, as determined by ab-initio calculations of the polymerization mechanism proposed for the formation of the aliphatic chains in the experiments based on CH2 addition. Transition states, with only an imaginary normal mode frequency, are also shown as insets.

Next, we perform DFT electronic structure calculations to get the potential energy surfaces of n-CnH2n+1 system, with n = 2-6. We compute a mechanism involving the consecutive addition of methylene radicals to a methyl seed: a process that we have termed methyl-methylene addition (MMA). In Fig. 4b we show a ball-and-stick scheme of the MMA mechanism. As a starting point, a methyl radical becomes an ethyl radical upon the addition of a methylene group (i.e., CH3 + CH2 → C2H5*). The reaction has an energy barrier of ΔETS = 0.17 eV (Fig. 4c). The process is highly efficient, as evidenced by the three orders of magnitude increase in ethyl density, nC2H5, in the kinetic chemical model (yellow line in Fig. 4a). The resulting product, C2H5*, remains a radical with an unpaired electron, which permits the addition of a second methylene group and the formation of a C3H7* radical with an even lower barrier of 0.11 eV. The MMA mechanism will continue according to the reaction,

with energy barriers between 0.1 and 0.2 eV. Similar energy barriers have been calculated for radical-radical reactions that trigger chemical enrichment in gas phase reactions during cross-beam experiments58,59.

For small molecules (n < 3), any excess energy is effectively stabilized in the intermediate compound through equipartition into vibrational and rotational modes. Our ab-initio molecular dynamics simulations show that such equipartition stabilization can efficiently occur within the typical lifetimes of the intermediates. Moreover, the participation of a third body at large enough densities (e.g., CH2 + CH3 + Ar → C2H5*+Ar), provides the pathway for removing the excess energy and generating ethyl and propyl radicals. Three-body reactions involving an Ar atom have typical rate constants of the order 10-30 cm6 s-1, which for a density of 1018 cm-3 result in rate constants on the order of 10-12 cm3 s-1. These rate constants are competitive enough and can contribute to the gas-phase polymerization sequence. In circumstellar envelopes, other species such as H2 or He may also serve as a third body. Finally, once CnH2n+1* products with n > 3 have been formed, radiative association processes become efficient and could approach collisional rates when the number of collisions is sufficiently high. Calculations also suggest that the energies of the barriers are reduced by thermodynamic effects as demonstrated by Gibbs free energies (see Supp. Fig. 5).

The addition of methylene monomers will continue with low energy barriers until either a CH3 radical or atomic hydrogen attaches to the end of the chain, resulting in alkane closure:

Reactions [2] and [3] proceed without energy barriers and serve as termination steps for the chain growth when k, m ≥ 3. In our experiments, the concentration of atomic hydrogen, [H], is higher than that of [CH3] and [CH2] as a consequence of H2 dissociation in the magnetron38, and most of the chains will cease growing due to atomic hydrogen addition. Consequently, [H] will play a crucial role in determining the average length of the chains. We note that similar chain growth mechanisms based on sequential addition of radical monomers have been recently reported. For instance, the coupling of acetylene molecules allows for the selective fabrication of polyacetylene chains40,45,60, and polyethylene synthesis proceeds through further polymerization with consecutive ethylene insertion into the chains61,61.

Astrochemical implications

The results presented in this study hold significant astrochemical implications. At temperatures similar to those in the inner layers of circumstellar envelopes of C-rich AGBs, the MMA mechanism presents an efficient route for n-alkanes formation. To operate in circumstellar envelopes, however, MMA requires the presence of CH2 and CH3 radicals. Simple hydrocarbons have been indeed detected in astronomical sources. CH4 has been detected in the vicinity of C-rich AGBs62, CH2 in molecular clouds63, and CH3+ was first detected in space in 2023 by advanced observations from the James Webb Space Telescope in a protoplanetary disc64. Chemical equilibrium calculations of the inner envelopes of AGB stars predict the abundances of these radicals in the range of 10-9 with respect to H265,66. In our kinetic model, CH2 and CH3 can be efficiently formed by the interaction of C and CH with H2 via three-body reactions (see Supp. Table 1). The formation of CH radicals from atomic carbon and H2 alone, through the reaction C + H2 → CH + H might need shock-wave-induced chemistry40 since this bimolecular reaction necessitates temperatures in the range of several thousand kelvins to operate efficiently. Once CH is formed, the bimolecular reaction of CH with H2 to produce CH2 can operate at the temperatures of the inner envelope as the reaction is endothermic by about 10 kJ/mol (Supp. Table 1). Another possibility for CH2 and CH3 formation is the photodissociation of CH4 in the outer envelope67, in the same manner as C2H is formed from C2H2.

Once CH3 and CH2 are present, the reaction barriers for methylene addition can be easily overcome as described above. MMA thus provides an all-natural formation mechanism of n-alkanes and related aliphatics observed in the interstellar medium. With the MMA mechanism as the starting point, we can propose a potential evolution sequence for interstellar n-alkanes (Supp. Fig. 1). Synthetized in the vicinity of C-rich AGB stars, they coagulate with aromatics, in sub-micrometer hydrogenated amorphous carbon grains as they are expelled from the circumstellar envelope by radiative pressure. In the post-AGB stage, visible-UV photons excite mid-IR emission and process the grains (as seen by the variation of the intensity of the 3.4 µm to 3.3 µm emission)68 being the aliphatic material more easily destroyed than the aromatic one69,70. Unprocessed n-alkanes effectively shielded from UV radiation by surrounding material (e.g. aromatics, silicates or silicon carbide grains)71 will eventually become part of dense molecular clouds and later protoplanetary discs of nascent stellar systems. The surviving material will be incorporated in comets, asteroids, and planetesimals, with some of it, possibly becoming the n-alkane chains found in meteorites. To further evaluate this hypothesis, we plan future experiments to test the stability of n-alkane under astrophysically relevant conditions. We finally note that our MMA mechanism may compete and complement other aliphatic synthesis processes known to operate in cosmic environments. Processes involving charged monomers—where long-range Coulomb interactions could facilitate reactions involving oppositely charged species, but it could also increase kinetic barriers for molecules carrying the same charge- and/or irradiation in carbon-containing interstellar ices may be also considered for a better understanding of the origin of interstellar aliphatic material.

Methods

Synthesis of carbonaceous species in sputter gas aggregation source (SGAS)

Alkanes and other carbonaceous species are synthesized using a Multiple Ion Cluster Source (Oxford Applied Research Ltd.), working under UHV conditions (base pressure 1 × 10−9 mbar). The magnetron in use was loaded with a graphite target of 99.95% purity with a typical applied power of 100 W. The Ar flow rate used for the experiments was 150 sccm. Extra-pure H2 (99.99% purity) was injected during the fabrication of the samples used in GC-MS through one of the lateral entrances of the aggregation zone of the SGAS to increase the amount of material during the preparation of the samples used in GC-MS, as this is a bulk sensitive technique. The carbonaceous analogs are deposited on the native oxide surface of Si wafers for GC-MS and on Au(111) for STM/nc-AFM.

Scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) and non-contact atomic force microscope (nc-AFM) measurements

Samples for STM and nc-AFM were prepared in the Stardust machine72,73. Subsequently, they were transferred to the UHV chambers of the microscopes located in two different laboratories, using a UHV suitcase with an ion-getter pump (base pressure < 1 × 10−9 mbar) to avoid chemical reactions with environmental atmospheric gases. Samples were deposited on an atomically flat Au(111) single crystal surface pre-cleaned by repeated sputtering (10 min using Ar+ ions at an energy of 1.25 kV) and annealing (at 800 K for 5 min) cycles. Clean Au(111) was later exposed to the carbonaceous species for 5 min, keeping the sample at room temperature, and then transferred to the UHV suitcase. STM and nc-AFM measurements were performed at 4.3 K in two independent low-temperature STM/ nc-AFM instruments (Scienta Omicron) with a base pressure of < 10−10 mbar.

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis

Silicon wafers with the carbonaceous analogs were immersed in 3 mL of acetonitrile and the extract was analyzed by a Thermo Scientific Trace Ultra gas chromatograph (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San José, CA, USA) coupled to a Thermo Scientific DSQ II single quadrupole mass spectrometer. Chromatographic separation was carried out on a poly (5% diphenyl 95% dimethylsiloxane) fused-silica capillary column (Zebron ZB-5) from Phenomenex (Torrance, CA, USA) of 30 m length, 0.25 mm internal diameter, and 1.00 µm film thickness. Helium (99.999% purity) was used as carrier gas at a constant flow of 1.5 mL min-1. Acetonitrile extracts (1 μL) were injected in pulsed splitless mode (0.25 min, 26 psi) at 300 °C. The oven temperature program was initially set at 60 °C for 1 min, increased to 300 °C at 15 °C min-1, and held for 30 min. The temperatures for the interface and the ion source were 300 and 200 °C, respectively. Electron impact (EI) mass spectra at 70 eV were recorded from m/z 40 to 500 at 3 scans s-1. Xcalibur 2.0 software was used for data acquisition and control of operating conditions. Compounds detected were identified by first matching the obtained mass spectra with those available in the NIST/EPA/NIH 05 and Wiley 6.0 mass spectral libraries. The identity of linear alkanes was confirmed by comparison of retention times and mass spectra of a standard mixture of linear alkanes from tetradecane (n-C14H30) to hexacosane (n-C26H54) plus octacosane (n-C28H58), triacontane (n-C30H62) and dotriacontane (n-C32H66) in acetonitrile. For the rest of the alkanes, confirmation was achieved by comparing their chromatographic retention indices measured under temperature-programmed conditions (RI) with literature data74.

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations

To describe the methyl-methylene addition mechanism producing alkanes in the gas phase, we use ab-initio Density Functional Theory to compute self-consistent wavefunctions, Ψ, and their associated ground-state variational total energies, U0, for geometrical configurations optimized to keep the maximum force on any atom below 0.02 eV/Å with Gaussian75. The all-electron chemistry model is based on the hybrid exchange-correlation functional B3LYP76 with the basis cc-pVTZ77. To explicitly include the effect of the temperature in the calculations, for each molecule (H, CH2, CH3, C2H5, C3H7, C4H9, C5H11, C5H12, and C6H14), we have computed a partition function78 taking into account electronic, translational, rotational and vibrational contributions to extend the electronic energies to temperature-dependent Gibb’s free energies. Transition states on the sequential methyl-methylene additions minimum reaction path have been computed within the Synchronous Transit-guided Quasi-Newton (STQN) method79; all have been characterized as having only one imaginary normal mode frequency.

Chemical kinetic model

we have constructed a network of 39 elementary reactions involving 16 chemical species to study the time evolution of different compounds along the simplest path to produce the shortest alkane, C2H6. Details for such a network are described in the Supplementary Information.

Data availability

The authors declare that all the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article (and Supplementary Information Files), or available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Data processing code and simulation models are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Alexander, C. M. O., Fogel, M., Yabuta, H. & Cody, G. D. The origin and evolution of chondrites recorded in the elemental and isotopic compositions of their macromolecular organic matter. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 71, 4380–4403 (2007).

Sabbah, H. et al. Detection of cosmic fullerenes in the Almahata Sitta Meteorite: are they an interstellar heritage? Astrophys. J. 931, 91 (2022).

Sandra, P. et al. The organic content of the Tagish lake meteorite. Science 293, 2236–2239 (2001).

Botta, O. & Bada, J. L. Extraterrestrial organic compounds in meteorites. Surv. Geophys. 23, 411–467 (2002).

Glavin, D. P. et al. in Primitive Meteorites and Asteroids Physical, Chemical and Spectroscopic Observations Paving the Way to Exploration (ed. Abreu, N.) 205–271 (Elsevier, 2018).

Nooner, D. W. & Oró, J. Organic compounds in meteorites—I. Aliphatic hydrocarbons. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 31, 1359–1394 (1967).

Martins, Z., Modica, P., Zanda, B. & d’Hendecourt, L. L. S. The amino acid and hydrocarbon contents of the Paris meteorite: insights into the most primitive CM chondrite. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 50, 926–943 (2015).

Mumma, M. J. et al. Detection of abundant ethane and methane, along with carbon monoxide and water, in Comet C/1996 B2 hyakutake: evidence for interstellar origin. Science 272, 1310–1314 (1996).

Sephton, M. A., Pillinger, C. T. & Gilmour, I. Normal alkanes in meteorites: molecular δ13C values indicate an origin by terrestrial contamination. Precambrian Res. 106, 47–58 (2001).

Joblin, C., Szczerba, R., Berné, O. & Szyszka, C. Carriers of the mid-IR emission bands in PNe reanalysed. Astron. Astrophys. 490, 189–196 (2008).

Kwok, S. & Zhang, Y. Mixed aromatic-aliphatic organic nanoparticles as carriers of unidentified infrared emission features. Nature 479, 80–83 (2011).

Kwok, S., Volk, K. & Bernath, P. On the origin of infrared plateau features in Proto–Planetary Nebulae. Astrophys. J. 554, L87–L90 (2001).

Sloan, G. C. et al. The unusual hydrocarbon emission from the early carbon star HD 100764: the connection between aromatics and aliphatics. Astrophys. J. 664, 1144–1153 (2007).

Raponi, A. et al. Infrared detection of aliphatic organics on a cometary nucleus. Nat. Astron. 4, 500–505 (2020).

Pilorget, C. et al. First compositional analysis of Ryugu samples by the MicrOmega hyperspectral microscope. Nat. Astron. 6, 221–225 (2022).

Sandford, S. A. et al. Organics captured from Comet 81P/Wild 2 by the stardust spacecraft. Science 314, 1720–1724 (2006).

Ito, M. et al. Hayabusa2 returned samples: a unique and pristine record of outer Solar System materials from asteroid Ryugu. Nat. Astron. 6, 1163–1171 (2022).

Tachibana, S. et al. Pebbles and sand on asteroid (162173) Ryugu: In situ observation and particles returned to Earth. Science 375, 1011–1016 (2022).

De Sanctis, M. C. et al. Localized aliphatic organic material on the surface of Ceres. Science 355, 719–722 (2017).

Schuhmann, M. et al. Aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons in comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko seen by ROSINA. Astron. Astrophys. 630, A31 (2019).

Pizzarello, S., Yarnes, C. T. & Cooper, G. The Aguas Zarcas (CM2) meteorite: new insights into early solar system organic chemistry. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 55, 1525–1538 (2020).

Ito, M. et al. A pristine record of outer Solar System materials from asteroid Ryugu’s returned sample. Nat. Astron. 6, 1163–1171 (2022).

Dartois, E. et al. Chemical composition of carbonaceous asteroid Ryugu from synchrotron spectroscopy in the mid- to far-infrared of Hayabusa2-returned samples. Astron. Astrophys. 671, A2 (2023).

Yabuta, H. et al. Macromolecular organic matter in samples of the asteroid (162173) Ryugu. Science 379, eabn9057 (2024).

Studier, M. H., Hayatsu, R. & Anders, E. Origin of organic matter in early solar system—I. Hydrocarbons. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 32, 151–173 (1968).

Sephton, M. A. Organic compounds in carbonaceous meteorites. Nat. Prod. Rep. 19, 292–311 (2002).

Navarro, V., van Spronsen, M. A. & Frenken, J. W. M. In situ observation of self-assembled hydrocarbon Fischer–Tropsch products on a cobalt catalyst. Nat. Chem. 8, 929 (2016).

Böller, B., Durner, K. M. & Wintterlin, J. The active sites of a working Fischer–Tropsch catalyst revealed by operando scanning tunnelling microscopy. Nat. Catal. 2, 1027–1034 (2019).

Llorca, J. & Casanova, I. Formation of carbides and hydrocarbons in chondritic interplanetary dust particles: a laboratory study. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 33, 243–251 (1998).

Kress, M. E. & Tielens, A. G. G. M. The role of Fischer-Tropsch catalysis in solar nebula chemistry. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 36, 75–91 (2001).

Ferrante, R. F., Moore, M. H., Nuth, J. A. & Smith, T. Laboratory studies of catalysis of CO to organics on grain analogs. Icarus 145, 297–300 (2000).

Sekine, Y. et al. An experimental study on Fischer-Tropsch catalysis: Implications for impact phenomena and nebular chemistry. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 41, 715–729 (2006).

Cabedo, V., Llorca, J., Trigo-Rodriguez, J. M. & Rimola, A. Study of Fischer–Tropsch-type reactions on chondritic meteorites. Astron. Astrophys. 650, A160 (2021).

Pareras, G., Cabedo, V., McCoustra, M. & Rimola, A. Single-atom catalysis in space: Computational exploration of Fischer–Tropsch reactions in astrophysical environments. Astron. Astrophys. 680, A57 (2023).

Abplanalp, M. J., Jones, B. M. & Kaiser, R. I. Untangling the methane chemistry in interstellar and solar system ices toward ionizing radiation: a combined infrared and reflectron time-of-flight analysis. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 5435–5468 (2018).

Jones, B. M. & Kaiser, R. I. Application of reflectron time-of-flight mass spectroscopy in the analysis of astrophysically relevant ices exposed to ionization radiation: methane (CH4) and D4-methane (CD4) as a case study. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 1965–1971 (2013).

Martínez, L. et al. Prevalence of non-aromatic carbonaceous molecules in the inner regions of circumstellar envelopes. Nat. Astron. 4, 97–105 (2020).

Martínez, L. et al. Metal-catalyst-free gas-phase synthesis of long-chain hydrocarbons. Nat. Commun. 12, 5937 (2021).

Accolla, M. et al. Silicon and hydrogen chemistry under laboratory conditions mimicking the atmosphere of evolved stars. Astrophys. J. 906, 44 (2021).

Santoro, G. et al. The chemistry of cosmic dust analogs from C, C2, and C2H2 in C-rich circumstellar envelopes. Astrophys. J. 895, 97 (2020).

Merino, P. et al. Graphene etching on SiC grains as a path to interstellar polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons formation. Nat. Commun. 5, 3054 (2014).

Hornekær, L. et al. Metastable structures and recombination pathways for atomic hydrogen on the graphite (0001) surface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 156104 (2006).

Schulz, F. et al. Imaging Titan’s organic haze at atomic scale. Astrophys. J. 908, L13 (2021).

Zhong, D. et al. Linear alkane polymerization on a gold surface. Science 334, 213–216 (2011).

Wang, S. et al. On-surface synthesis and characterization of individual polyacetylene chains. Nat. Chem. 11, 924–930 (2019).

Yamada, R. & Uosaki, K. Two-dimensional crystals of alkanes formed on Au(111) surface in neat liquid: structural investigation by scanning tunneling microscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 104, 6021–6027 (2000).

Zhang, H.-M., Xie, Z.-X., Mao, B.-W. & Xu, X. Self-assembly of normal alkanes on the Au (111) surfaces. Chem. A Eur. J. 10, 1415–1422 (2004).

Schuler, B., Meyer, G., Peña, D., Mullins, O. C. & Gross, L. Unraveling the molecular structures of asphaltenes by atomic force microscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 9870–9876 (2015).

Gross, L. et al. Organic structure determination using atomic-resolution scanning probe microscopy. Nat. Chem. 2, 821–825 (2010).

Gross, L. et al. Bond-order discrimination by atomic force microscopy. Science 337, 1326–1329 (2012).

Gross, L. et al. Atomic force microscopy for molecular structure elucidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 3888–3908 (2018).

Schuler, B. et al. Characterizing aliphatic moieties in hydrocarbons with atomic force microscopy. Chem. Sci. 8, 2315–2320 (2017).

Pavliček, N. et al. Polyyne formation via skeletal rearrangement induced by atomic manipulation. Nat. Chem. 10, 853–858 (2018).

Kaiser, K. et al. An sp-hybridized molecular carbon allotrope, cyclo[18]carbon. Science 365, 1299–1301 (2019).

Kaiser, K. et al. Visualization and identification of single meteoritic organic molecules by atomic force microscopy. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 57, 644–656 (2022).

Wetterer, S. M., Lavrich, D. J., Cummings, T., Bernasek, S. L. & Scoles, G. Energetics and kinetics of the physisorption of hydrocarbons on Au(111). J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 9266–9275 (1998).

Kissin, Y. V. Hydrocarbon components in carbonaceous meteorites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 67, 1723–1735 (2003).

Zhao, L. et al. Pyrene synthesis in circumstellar envelopes and its role in the formation of 2D nanostructures. Nat. Astron. 2, 413–419 (2018).

Zhao, L. et al. Molecular mass growth through ring expansion in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons via radical–radical reactions. Nat. Commun. 10, 3689 (2019).

Ravagnan, L. et al. sp hybridization in free carbon nanoparticles—presence and stability observed by near edge X-ray absorption fine structure spectroscopy. Chem. Commun. 47, 2952–2954 (2011).

Weijun, G. et al. Visualization of on-surface ethylene polymerization through ethylene insertion. Science 375, 1188–1191 (2022).

Hall, D. N. B. & Ridgway, S. T. Circumstellar methane in the infrared spectrum of IRC+10°216. Nature 273, 281–282 (1978).

Polehampton, E. T., Menten, K. M., Brünken, S., Winnewisser, G. & Baluteau, J.-P. Far-infrared detection of methylene. Astron. Astrophys. 431, 203–213 (2005).

Berné, O. et al. Formation of the methyl cation by photochemistry in a protoplanetary disk. Nature 621, 56–59 (2023).

Agúndez, M., Martínez, J. I., de Andres, P. L., Cernicharo, J. & Martín-Gago, J. A. Chemical equilibrium in AGB atmospheres: successes, failures, and prospects for small molecules, clusters, and condensates. Astron. Astrophys. 637, A59. (2020).

Cherchneff, I. The inner wind of IRC+10216 revisited: new exotic chemistry and diagnostic for dust condensation in carbon stars. Astron. Astrophys. 545, A12 (2012).

Agúndez, M., Roueff, E., Le Petit, F. & Le Bourlot, J. The chemistry of disks around T Tauri and Herbig Ae/Be stars. Astron. Astrophys. 616, A19 (2018).

Chiar, J. E., Pendleton, Y. J., Geballe, T. R. & Tielens, A. G. G. M. Near‐infrared spectroscopy of the Proto–Planetary Nebula CRL 618 and the origin of the hydrocarbon dust component in the interstellar medium. Astrophys. J. 507, 281–286 (1998).

Goto, M. et al. Spatially resolved 3 micron spectroscopy of IRAS 22272+5435: formation and evolution of aliphatic hydrocarbon dust in proto–planetary nebulae. Astrophys. J. 589, 419–429 (2003).

Pilleri, P., Joblin, C., Boulanger, F. & Onaka, T. Mixed aliphatic and aromatic composition of evaporating very small grains in NGC 7023 revealed by the 3.4/3.3 μm ratio. Astron. Astrophys. 577, A16 (2015).

Jones, A. P. et al. The evolution of amorphous hydrocarbons in the ISM: dust modelling from a new vantage point. Astron. Astrophys. 558 (2013).

Martínez, L. et al. Precisely controlled fabrication, manipulation and in-situ analysis of Cu based nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 8, 7250 (2018).

Santoro, G. et al. INFRA-ICE: an ultra-high vacuum experimental station for laboratory astrochemistry. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 91, 124101 (2020).

Andriamaharavo, N. R. Retention Data NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center. Retrieved March 17, 2015 (NIST Mass Spectrometry Data Center, 2014).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian∼ 09 Revision D. 01. (Science Open, 2014).

Becke, A. D. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A 38, 3098–3100 (1988).

Dunning, T. H. Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. I. The atoms boron through neon and hydrogen. J. Chem. Phys. 90, 1007–1023 (1989).

Kardar, M. Statistical Physics of Particles (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Peng, C. & Bernhard Schlegel, H. Combining synchronous transit and Quasi-Newton methods to find transition states. Isr. J. Chem. 33, 449–454 (1993).

Krishnamurthy, R. V., Epstein, S., Cronin, J. R., Pizzarello, S. & Yuen, G. U. Isotopic and molecular analyses of hydrocarbons and monocarboxylic acids of the Murchison meteorite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 56, 4045–4058 (1992).

Cronin, J. R. & Pizzarello, S. Aliphatic hydrocarbons of the Murchison meteorite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 54, 2859–2868 (1990).

Acknowledgements

We thank the European Research Council for funding support under Synergy Grant ERC-2013-SyG, G.A. 610256 (NANOCOSMOS). We also acknowledge partial support from the Spanish Research Agency (AEI) through grants PID2021-125309OA-I00, TED2021-129416A-I00, CNS2022-135658, PID2020-113142RB-C21, MAT2017-85089-c2-1R, FIS2016-77578-R and FIS2016-77726-C3-1-P by MCIN/AEI/ 10.13039/501100011033. Support from the FotoArt-CM Project (P2018/NMT-4367) through the Program of R&D activities between research groups in Technologies 2013, co-financed by European Structural Funds, is also recognized. G.S. acknowledges grant RYC2020-029810-I funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by “ESF Investing in your future”. C.S.S acknowledges funding from the Agencia Estatal de Investigación through the Ramón y Cajal contract (RYC2018-024364-I). PM acknowledges grant EUR2021-122006 funded by MCIN/AEI/ 10.13039/501100011033 and, as appropriate, by “ERDF A way of making Europe”, by the “European Union” or by the “European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR”. P.M. also acknowledges grant RYC2020-029800-I funded by MCIN/AEI/ 10.13039/501100011033 and, as appropriate, by “ESF Investing in your future” or by “European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR”. R.O. acknowledges financial support from the Spanish Ministry for Science and Innovation (PGC2018-096047-B-I00), the regional government of Comunidad de Madrid (Grant S2018/NMT-4321, and Program for Excellence for University Professors, V PRICIT), Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (UAM/48) and IMDEA Nanoscience. Both IMDEA Nanoscience and IFIMAC acknowledge support from the Severo Ochoa and Maria de Maeztu Programs for Centres and Units of Excellence in R&D (MINECO, Grants CEX2020-001039-S and CEX2018-000805-M). In memoriam of Prof. S. Pizzarello.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.M., P.L.D.A., and J.A.M.G. conceived the project. L.M., G.S., K.L., M.A. synthesized and characterized the samples. N.R.D.A., C.S.S., A.M.J., R.O., M.P., D.S., E.L.A., J.E.Q.L., and J.M. carried out the experimental measurements. J.I.M. and P.L.D.A. developed and carried out the theoretical analysis. P.M., P.L.D.A., and J.A.M.G. supervised the research and wrote the paper. The manuscript reflects the contributions and ideas of all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Merino, P., Martínez, L., Santoro, G. et al. n-Alkanes formed by methyl-methylene addition as a source of meteoritic aliphatics. Commun Chem 7, 165 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-024-01248-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-024-01248-6