Abstract

Increasing chemical pollution is a threat to sustainable water resources worldwide. Plastics and harmful additives released from plastics add to this burden and might pose a risk to aquatic organisms, and human health. Phthalates, which are common plasticizers and endocrine-disrupting chemicals, are released from polyvinyl chloride (PVC) microplastics and are a cause of concern. Therefore, the leaching kinetics of additives, including the influence of environmental weathering, are key to assessing exposure concentrations but remain largely unknown. We show that photoaging strongly enhances the leaching rates of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) by a factor of 1.5, and newly-formed harmful transformation products, such as mono(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP), phthalic acid, and phthalic anhydride from PVC microplastics into the aquatic environment. Leaching half-lives of DEHP reduced from 449 years for pristine PVC to 121 years for photoaged PVC. Aqueous boundary layer diffusion (ABLD) is the limiting mass transfer process for the release of DEHP from pristine and photoaged PVC microplastics. The leaching of transformation products is limited by intraparticle diffusion (IPD). The calculated mass transfer rates can be used to predict exposure concentrations of harmful additives in the aquatic environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global chemical pollution is an issue of increasing concern1. Rapidly increasing numbers and amounts of chemicals are being released into the environment through various sources with possibly detrimental consequences for sustainable living in the future2,3. Plastics and potentially toxic substances stemming from plastics add to this chemical burden and are a threat to humans and animal life4,5. In the environment, plastics are subject to degradation and fragmentation processes, leading to the formation of ever smaller particles of various shapes, structures, and sizes, including microplastics (<5000 µm)6. Microplastics are ubiquitous in the environment and have become an increasing, multifaceted problem for living organisms and human health. On a global scale, microplastics can negatively impact carbon and nutrient cycling (including nitrogen and phosphorous) in aquatic environments, and they can irreversibly alter the structure of sediments and soil habitats7. At the individual level, exposure to microplastics through uptake (e.g., ingestion and inhalation) or skin contact can cause serious health damage, including inflammation and oxidative stress in humans and animals8,9.

In addition to physical hazards, (micro)plastics contain a plethora of chemical compounds. These include non-intentionally added substances (NIAS) such as by-products, degradation products, and contaminants10. In addition to NIAS, which are introduced at all stages of the life cycle of plastics, more than 10,000 chemicals such as monomers, processing aids, and additives (55% of the identified chemicals) are used intentionally for the manufacturing of plastic products. More than 2400 of these intentionally used plastic chemicals are potentially hazardous given their persistent, bio-accumulative, toxic, or endocrine-disruptive properties11. Additives contribute to improving the material properties of plastics and can account for up to 70 wt% of plastic products for PVC5,12. With few exceptions, additives are not chemically bound to the polymer and therefore inevitably leach into the surrounding environment during the life-span of the plastic product5,13. Some additives are even designed to migrate through plastics and be released14.

Potentially harmful additives used in plastic manufacturing can become a serious problem in the environment and for humans15. For example, the release of a tire rubber-derived additive, i.e., its transformation product (6PPDq), caused acute recurrent mortality of coho salmon populations in urban creeks14. Bisphenol A (BPA) and its analogs bisphenol S and bisphenol F interfere with the hormone system16. In particular, exposure to plasticizers, more specifically, phthalic acid esters (phthalates), has been associated with several health damages arising from their endocrine-disrupting effects and linked diseases such as liver cancer, type II diabetes, and reproductive injuries15. Phthalates, e.g., benzyl butyl phthalate (BBP), dibutyl phthalate (DPB), and di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP), are known to have adverse health effects17, but they have nonetheless been found in various everyday plastic products, including food contact materials18 and medical supplies19. Worldwide, 6–8 million tons of phthalates are produced annually, with the main use (80%) being in the manufacture of polyvinyl chloride (PVC)5,20. Recently, the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) has specifically identified the release of ortho-phthalates such as DEHP from PVC as a risk to humans and the environment, with PVC microplastics being the main source of phthalate release21.

There is an urgent need to assess the chemical pollution stemming from additives, especially phthalates released from PVC microplastics. To assess the exposure and, ultimately, the risk for aquatic and human life, in-depth knowledge of leaching kinetics and processes is required to predict environmental concentrations of phthalates. Diffusion models, such as the intraparticle diffusion (IPD) model and the aqueous boundary layer diffusion (ABLD) model, have been applied to elucidate the leaching of organic contaminants and additives, for example, organochlorine pesticides22, polycyclic compounds23, polychlorinated biphenyls24, brominated flame retardants25, chlorinated benzenes26, and phthalates27 from different micron-sized polymers including polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), and PVC into aqueous systems. Process-specific parameters for IPD and ABLD depend on the properties of the diffusing compound and the polymer28. The relative contribution of IPD and ABLD to the overall leaching process is specific to the contaminant-polymer combinations under consideration. In general, ABLD is the limiting mass transfer process for compounds with high octanol-water partition coefficients (KO/W) in combination with a high ABL thickness, and a short diffusion distance in the polymer22. This is exemplified by thin PE sheets, which are commonly used as passive samplers for hydrophobic organic contaminants in aqueous environments29. Under environmentally relevant conditions, the leaching of DEHP from pristine PVC into air30 and water27 is limited by BLD. In aquatic environments, however, several factors, including flow conditions, salinity, the aqueous concentration of organic carbon, and the water temperature, crucially influence leaching. The impact of these factors on the leaching kinetics and processes has been determined by integrating experimental data into models in our previous study31. In addition, weathering of plastics, for example, due to heat, light, mechanical stress, and microbial activity, requires consideration when investigating leaching processes32.

PVC is one of the least stable polymers in the environment33,34. During the manufacturing process, an often complex mixture of stabilizers is therefore added to the polymer to ensure its durability in outdoor applications35. In particular, PVC is susceptible to photodegradation by UV light with a peak sensitivity at 320 nm36. UV irradiation induces the autocatalytic dechlorination of PVC (Fig. S5)34. In the absence of oxygen, photochemical reactions of the polymer lead to the formation of polyenic -(CH=CH-)n- sequences and thus to the discoloration (yellowing) of the polymer. Under atmospheric conditions, the oxidation of polyene (photobleaching) depends on the oxygen diffusion rate into the polymer37,38. Such changes in the physicochemical properties of the polymer can strongly influence the leaching of phthalates from PVC microplastics27,32, and they should be taken into account when using leaching kinetics for environmental exposure assessment. The influence of UV irradiation on the leaching of phthalates has been investigated from high and low-density PE into aqueous solutions39,40 and from PVC to petroleum oils41. The leaching of phthalates from photoaged PVC microplastics into aqueous solutions has been investigated in only a few studies. These have demonstrated that photoaging can result in either higher or lower leaching rates. The experimental set-up (e.g., wet versus dry photoaging) influenced the amount of phthalates leached. Higher leaching rates were associated with changes in the chemical properties of the photoaged PVC, while lower leaching rates were associated with the degradation of phthalates to products not quantified in these studies42,43,44. The leaching process of phthalates from PVC impacted by UV light into water has received little attention and remains largely unknown.

Besides affecting the polymer structure, photoaging can lead to the transformation of additives contained in PVC, including plasticizers like phthalates45. Absorption of short-wave UV light and hydroxyl radical attack induces the transformation of DEHP to mono(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP) and 2-ethylhexanol (Fig. S6). Further irradiation leads to the transformation of MEHP to phthalic acid. The formation of phthalic anhydride has been suggested but not confirmed45. The aforementioned transformation products have significantly different chemical properties compared to DEHP46, potentially altering the leaching process: they are smaller, more soluble in water and less hydrophobic47. These transformation products can also cause health problems as MEHP is suspected to interact with the hormone system in ways similar to DEHP, causing negative developmental and reproductive effects48,49. MEHP and phthalic acid can be toxic to aquatic invertebrates50. However, the leaching process of these transformation products from PVC microplastics has not yet been studied, and hence, there exists a major knowledge gap for exposure assessment of phthalates in aquatic systems.

In this study, we investigated the leaching of DEHP (which was used as a model phthalate) and its most abundant transformation products MEHP, phthalic acid, and phthalic anhydride from PVC microplastics into aqueous solutions. PVC microplastics were artificially photoaged under UV light for 24 and 48 days. We determined time-dependent leaching curves for DEHP from pristine and photoaged microplastics and, for the first time, also for transformation products. We identified the governing leaching process for each compound and elucidated the effects of photoaging on phthalates leaching.

Results and discussion

Photoaging enhanced the leaching of DEHP from PVC microplastics

The influence of photoaging on the leaching of DEHP and its transformation products was studied using spherical PVC microplastics with a radius of 2 mm, a surface area of 169 m2 g−1 and an initial DEHP content of approximately 38 wt%27. These model microplastics were artificially photoaged (dry aging) for 24 days and for 48 days under standardized laboratory conditions in a UV chamber51. PVC microplastics are denoted according to the degree of photoaging: PVCPristine (pristine PVC microplastics), PVC24d, and PVC48d (PVC microplastics aged for 24 days and 48 days, respectively). The physicochemical properties of the PVC microplastics were determined before and after photoaging. Details on the characterization of PVC microplastics and photoaging conditions are provided at the beginning of the “Methods” section and in Supplementary Information S2. Laboratory batch-leaching experiments were conducted using pristine and photoaged PVC microplastics added to a 1 mM KCl solution using an infinite sink method52. At defined time intervals (after 1, 3, 5, 9, 16, 30, 50 and 80 days), the mass of DEHP and of each transformation product leached from the PVC microplastics was determined.

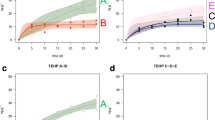

Exposure of PVC microplastics to UV irradiation strongly increased the leaching of DEHP, therefore, leaching processes in the environment will be substantially faster than estimates based on pristine PVC microplastics. The time-dependent leaching curves of DEHP were linear for PVCPristine (R2 = 0.998, p = 4.78 × 10−9), PVC24d (R2 = 0.947, p = 4.82 × 10−5), and PVC48d (R2 = 0.953, p = 3.32 × 10−5) during 80 days of the experiment (Table S4.1). The mass of DEHP released instantaneously increased with the degree of photoaging of the PVC microplastics from 0.199 µg for PVCPristine to 2.64 µg and 6.83 µg for PVC24d and PVC48d, respectively (Fig. 1). Continuous leaching rates (slopes of the time-dependent leaching curves) increased with the degree of photoaging from 0.135 µg d−1 for pristine PVC microplastics to 0.179 µg d−1 and 0.209 µg d−1 for PVC24d and PVC48d, respectively.

A Experimentally determined time-dependent leaching curves. The mass of DEHP leached (mleach in µg, y-axis) from PVCPristine27 (black circles), PVC24d (blue circles) and PVC48d (green circles) versus the respective sampling time (days, x-axis) are shown. The error bars represent one standard deviation (n = 3) calculated using Gaussian error propagation. The leaching curves can be described by linear regression lines (R2 = 0.947–0.998). B Fitting of the experimental data using mass transfer models for ABLD and IPD. The fitted ABLD model (solid lines in the respective color of the experiment) and the IPD model (dashed purple line) using the diffusion coefficient of DEHP in PVC DPVC = 10−14 m2 s−1 (reported for PVC with comparable content of DEHP54) are shown. Fdesorbed (y-axis) is the cumulative fraction of DEHP leached from the PVC microplastics. The limit of quantification (LOQ) of the method is indicated (dashed gray line).

Photoaging led to a 15% increase in surface area from 169 ± 3.18 m2 g−1 for PVCPristine to 195 ± 1.39 m2 g−1 for PVC48d due to chain scission followed by crack formation, and thereby, to an increase in continuous and instantaneous leaching of DEHP27. The surface area of PVC24d could not be determined using BET analysis because, in contrast to PVCPristine and PVC48d, PVC24d microplastics were sticky, causing interferences during the measurements. The leaching rate increased by a factor of 1.3 and 1.5 from PVCPristine to PVC24d and from PVCPristine to PVC48d, respectively. An increase in the leaching rate was also reported by Yan et al. 42 for the leaching of di-n-butyl phthalate (DnBP) from naturally photoaged PVC with a similar phthalate content (30 wt%) compared to the PVC microplastics used in this study42. Depending on the density of PE, UV irradiation during the experiments led to a 1.3 to 7.6-fold increase in the leaching rate of DEHP40. Exposure to artificial light led to a doubling of the released mass of dimethyl phthalate (DMP) and diethyl phthalate (DEP) from a PVC cable compared to the dark control44. In contrast, for PVC foil exposed to UVA light (320–400 nm)53 lower leaching rates of DEHP compared to the dark control were reported43. Less pronounced effects of photoaging could be due to the black color of the investigated PVC foil absorbing light and inhibiting the effect of photoaging into deeper layers or due to the phototransformation of DEHP during the experiment38.

Leaching of DEHP from photoaged PVC microplastics is aqueous boundary layer diffusion limited

Phototransformation led to a decrease in the DEHP content of the PVC microplastics from 37.8 wt% for PVCPristine27 to 22.6 wt% for PVC24d and to 15.7 wt% for PVC48d (p = 3.66 × 10−6, Table 1 and Table S2.4). The influence of thermal aging on the spatial distribution of DEHP was ruled out by time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (TOF-SIMS) analyses of the cross sections of PVCPristine, PVC24d, and PVC48d. The analyses showed that the DEHP concentrations within the respective PVC microplastics (edge, middle, center) remained similar (Fig. S2.5). The results of the TOF-SIMS analysis confirmed the findings of the DEHP content measurements: The DEHP concentration was significantly different between the three PVC microplastics (p = 4.05 × 10−8, Table S2.5) and decreased from PVCPristine to PVC24d, and from PVC24d to PVC48d. The reduction in the DEHP concentrations in PVC24d and PVC48d compared to PVCPristine suggested that phototransformation of DEHP had occurred throughout the PVC microplastics, from the surface to the core. With decreasing DEHP content, PVC microplastics became less flexible and DPVC decreased54. DPVC decreased from 8.45 × 10−14 m2 s−1 for PVCPristine to 4.58 × 10−15 m2 s−1 and 1.22 × 10−15 m2 s−1 for PVC24d and PVC48d, respectively (Eq. 3, “Methods”). The calculations of DPVC do not account for the effects of photoaging on the polymer structure. The surface of the polymer oxidized with increasing photoaging as indicated by an increase in the carbonyl index ICO from 11.9 ± 0.46 for PVCPristine to 23.6 ± 1.34 for PVC24d and to 50.6 ± 1.22 for PVC48d (Eq. 1)55. While ICO values close to zero have been reported for unaged PVC56, pristine PVC used in this study has a higher ICO because of the high content of C=O-containing DEHP42. Photoaging led to the discoloration (yellowing) of the PVC microplastics (Fig. S2.2.1). Besides the photo-oxidized surface, a brownish subsurface layer indicating high polyene concentrations37 was identified from the cross section of the PVC microplastics (Fig. S2.2.2). UV light absorption in this layer hindered photochemical reactions in deeper layers, and the PVC microplastics became less yellow towards the center38. The glass transition temperature Tg increased from −33 °C for PVCPristine to −20 °C and −8 °C for PVC24d and PVC48d, respectively, confirming the increasing degree of crosslinking in the polymer with prolonged exposure time to UV irradiation57. Tg of unplasticized PVC and DEHP are 80 °C and −83.5 °C, respectively. Higher Tg for PVC24d and PVC48d compared to PVCPristine result from the lower DEHP content in the polymer due to phototransformation58,59. A reduction in the polymer chain length due to chain scission results in a lower number-averaged molecular weight (Mn) of the PVC microplastics37. With increasing exposure time to UV irradiation, Mn decreased from 76.2 kg mol−1 for PVCPristine to 7.04 kg mol−1 and 6.54 kg mol−1 for PVC24d and PVC48d, respectively. Crosslinking reactions of polymer chains due to photoaging resulted in a higher weight-averaged molecular weight (Mw) in PVC24d (Mw = 260 kg mol−1) and PVC48d (Mw = 237 kg mol−1) compared to PVCPristine (Mw = 182 kg mol−1). The lower solubilities in tetrahydrofuran (THF) of PVC exposed to UV light for more than 1000 h (equivalent to 42 days) could have resulted in a lower Mw of PVC48d compared to PVC24d57. In the literature, the lowest Mw were found at the surface and in deeper layers of photoaged PVC, while the highest Mw values were found in polyene-rich subsurface layers37. A brownish subsurface indicates the polyene-rich layers37 in PVC48d (Fig. S2.2.2).

Photoaging-induced changes in the polymer structure of the PVC microplastics can lead to spatial variability of DPVC. Whereas DPVC could be higher in the oxidized surface layer characterized by chain scission, crosslinking reduces diffusion processes and DPVC in the core of the PVC microplastic could be lower than the calculated DPVC41. For IPD-limited leaching processes, lower DPVC values slow down leaching (Eq. 2). The introduction of oxygen-containing functional groups with increasing exposure time to UV light (Fig. S2.3.2) increased the surface polarity and hydrophilicity of the PVC microplastics and led to lower partition coefficients, KPVC/W39,42,44. Decreasing KPVC/W values accelerate the leaching of DEHP for ABLD-limited leaching processes (Eq. 4)27,42.

While the leaching of DEHP from pristine PVC microplastics is ABLD-limited27, we investigated if photoaging led to a shift of the limiting mass-transfer process from ABLD to IPD. This shift in mass transfer would substantially change the leaching kinetics of DEHP into aqueous systems and its susceptibility to effects from environmental factors31. However, IPD could not describe the experimental data and ABLD was clearly the governing diffusion process for the leaching of DEHP from photoaged PVC (Fig. 1). The log KPVC/W decreased from 8.55 for PVCPristine to 8.21 and 7.98 for PVC24d and PVC48d, respectively, and was the decisive parameter for the increase in both continuous and instantaneous leaching of DEHP from photoaged PVC microplastics. The reduction in KPVC/W can be attributed to the introduction of oxygen-containing functional groups, such as C=O (Fig. S2.3.3), and the decreased concentration of DEHP in photoaged PVC microplastics (cPVC). This resulted in a more pronounced change in KPVC/W in comparison to the leaching rates. Lower KPolymer/W have been observed for DEHP and DnBP after exposure of PE and PVC to UV light and to sunlight, respectively40,42.

In well-mixed laboratory batch experiments similar to this study, the leaching of hydrophobic contaminants, namely tonalide (log KO/W = 5.7)23 and polychlorinated biphenyls (log KO/W = 4.90–8.19)24 from spherical PE microplastics was also limited by ABLD with the partition coefficient KPE/W being the decisive parameter. The release of brominated flame retardants (log KABS/W = 2–3.1) from acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) was limited by IPD due to the lower partition coefficients25. The leaching of less hydrophobic hexachlorocyclohexanes (log KO/W ≤ 4.14) from PE and PP films was IPD-limited, while the leaching of chlorinated benzenes with higher partition coefficients (log KO/W ≥ 5.17) was ABLD-limited26.

Leaching half-lives of DEHP from pristine and photoaged PVC microplastics into water were calculated using the aqueous diffusion coefficient Daq, the aqueous boundary layer thickness δ and the respective KPVC/W (Eq. 5)27. The corresponding leaching half-lives were 449 years for the leaching of DEHP from PVCPristine, 205 years from PVC24d and 121 years from PVC48d. Compared to the influence of other environmental factors, photoaging had a more pronounced effect on the leaching half-lives of DEHP from PVC microplastics than ionic strength and water temperature but a less pronounced effect than flow conditions, dissolved organic carbon, and fragmentation (particle size)27,31. In aquatic environments, these factors are subject to a high spatial-temporal variability, and their interaction must be taken into account when studying leaching processes.

Photoaging enhanced the leaching of transformation products from PVC microplastics

Photoaging of PVC microplastics led to higher leaching rates of MEHP, phthalic acid, and phthalic anhydride. PVCPristine did not contain any of these transformation products, and they were not observed in the time-dependent leaching curves (Table 1, Fig. 2). Slightly more MEHP leached from PVC48d compared to PVC24d, due to the higher initial MEHP content (p = 2.95 × 10−5, Table S2.4) in PVC48d. Leaching rates of MEHP from PVC24d and PVC48d were higher for the first 16 days than for later time points (Table 2, Table S4.2). After 80 days, 49.4 µg (10% of the initial content) and 54.7 µg (4% of the initial content) of MEHP were released from PVC24d and PVC48d, respectively, indicating that MEHP depletion was not reached. In comparison, 16.0 µg (PVC24d) and 22.8 µg (PVC48d) of DEHP, corresponding to 0.08% and 0.17% of the initial content, respectively, were leached after 80 days. MEHP was leached faster than DEHP because (1) MEHP is less hydrophobic (KPVC/W is lower) and diffuses faster through the ABL, and (2) MEHP is smaller and diffuses faster through PVC46.

A–C Time-dependent leaching curves of the transformation products. The mass of MEHP, phthalic acid, and phthalic anhydride leached from PVCPristine (black circles), PVC24d (blue circles) and PVC48d (green circles) (mleach in µg, y-axis) versus the respective sampling time (days, x-axis) are shown. The error bars represent one standard deviation (n = 3) calculated using Gaussian error propagation. D–G Fitting of the experimental data using mass transfer models for ABLD and IPD. The ABLD model (solid purple line) and the IPD model (dashed lines in the respective color of the experiment) for MEHP and phthalic acid are shown. Fdesorbed (y-axis) is the cumulative fraction of each transformation product leached from the PVC microplastics. For the leaching of MEHP from PVC48d and for phthalic acid, KO/W of the compound was used to calculate the ABLD model. The limit of quantification (LOQ) of the method is indicated (dashed gray line).

Photoaging led to a 13-fold increase in the phthalic acid content (p = 2.34 × 10−5, Table 1 and Table S2.4) in PVC48d compared to PVC24d, consequently leading to higher leaching quantities. For instance, after 80 days, 10.4 µg of phthalic acid was leached from PVC48d compared to 1.56 µg from PVC24d. As for MEHP, the leaching rates of phthalic acid were higher for the initial 16 days than for subsequent time points (Table 2, Table S4.2).

The amount of phthalic anhydride leached after 80 days increased from 4.99 µg for PVC24d to 6.05 µg for PVC48d due to the higher initial concentration in PVC48d compared to PVC24d (p = 7.35 × 10−6, Table 1 and Table S2.4). The time-dependent leaching curves had a steeper slope at the beginning of the experiment and a flatter slope at later leaching times (Table 2, Table S4.2). The initial content of phthalic anhydride in photoaged PVC microplastics was lower than the mass leached, probably due to the reaction of phthalic anhydride with THF during the dissolution of the PVC microplastics (the dissolution was required to determine the phthalic anhydride content in the microplastics, S2.4) resulting in the formation of products not quantified in this study60.

Intraparticle diffusion governs the leaching of transformation products

At the beginning of the leaching experiment (1–16 days), ABLD was the rate-limiting process for the leaching of MEHP from PVC24d (log KPVC/W = 5.40) (Fig. 2). The IPD model could not adequately fit the experimental data due to relatively high DPVC and thus, fast diffusion of MEHP in the oxidized surface layer of the photoaged PVC microplastics characterized by chain scission. After surface depletion, the diffusion of MEHP slowed down due to lower DPVC in the cross-linked deeper layers of the PVC microplastics. A shift in mass transfer could be observed, and IPD became the limiting mass transfer process for the leaching of MEHP from PVC24d at later time points; DPVC was 5 × 10−16 m2 s−1. For PVC48d, introducing oxygen-containing functional groups with proceeding photoaging increased the surface hydrophilicity of the PVC microplastics leading to lower KPVC/W of MEHP for PVC48d than for PVC24d. Thereby, ABLD became faster and could not describe the experimental data. IPD was the rate-limiting mass transfer process for the leaching of MEHP from PVC48d. DPVC was lower for PVC48d (DPVC = 8 × 10−17 m2 s−1) than for PVC24d because of increasing crosslinking of the polymer with increasing exposure time to UV light, slowing down IPD. Leaching of MEHP from PVC48d was faster at the beginning of the experiments due to higher DPVC in the surface layer. With increasing leaching time, leaching slowed down, since diffusion of MEHP in deeper layers of the photoaged PVC microplastics was slower. Fitted DPVC values for IPD represent an average value for the PVC microplastics. Compared to chain scission, crosslinking reactions lead to heterogeneous polymer structures with local accumulation of conjugated polyenes37,38. In the aquatic environment, floating plastic debris are mostly not evenly photoaged61. To better describe IPD-limited leaching from photoaged PVC microplastics, numerical models accounting for the spatial variability of DPVC require consideration in future research54. For ABLD-limited leaching, heterogeneous photoaging of the surface of the microplastics resulting in spatial variability of KPVC/W must be taken into account. Photoaging-induced changes in the concentration of the diffusing compound altering KPVC/W also need to be integrated into numerical models.

The ABLD model did not fit the time-dependent leaching curves for phthalic acid from PVC24d and PVC48d because phthalic acid is rather hydrophilic (log KO/W = 0.74). IPD was also the rate-limiting process for phthalic acid from photoaged PVC microplastics (Fig. 2). IPD slowed down with proceeding leaching time due to higher DPVC at the surface and lower DPVC values in deeper layers of the PVC microplastics. DPVC decreased from 1.5 × 10−16 m2 s−1 for PVC24d to 1.5 × 10−17 m2 s−1 for PVC48d because crosslinking reactions in the polymer increased with exposure time to UV light.

Time-dependent leaching curves for phthalic anhydride were not evaluated using the ABLD and IPD models because the initial content in the photoaged PVC microplastics could not be determined. Phthalic anhydride is more hydrophilic than phthalic acid (Table 3), and ABLD will be relatively fast compared to IPD. Due to similar molecular weight and structure, similar DPVC can be assumed for phthalic acid and phthalic anhydride. IPD is expected to be the governing diffusion process for the leaching of phthalic anhydride from photoaged PVC microplastics.

Conclusions

Photoaging strongly enhances the leaching of DEHP from PVC microplastics and leads to the formation and enhanced release of transformation products into aquatic environments. Leaching of DEHP from pristine and photoaged microplastics is governed by ABLD due to high KPVC/W. Leaching of transformation products from photoaged microplastics is in most cases governed by IPD because KPVC/W is low and photoaging leads to crosslinking in the polymer and, thereby, to lower DPVC.

This study provides a mechanistic understanding of the effects of photoaging on the leaching of phthalates and transformation products from PVC microplastics into aquatic systems. The solar UV radiation in the environment exhibits considerable natural variability. Diurnal and annual variations, as well as the latitude, altitude, and weather conditions (e.g., UV attenuation by clouds), strongly impact UV radiation62. Site-specific parameters must be taken into account when investigating the photoaging phenomena of plastics in the environment. In addition, leaching processes in complex aquatic environments can be significantly influenced by a number of environmental factors, including flow conditions, water chemistry, mechanical stress, and microbial activity (e.g., biofilm formation), resulting in altered leaching times such as half-lives27. The leaching models and calculations presented here can be adapted to the specific environmental conditions.

While environmental processes can facilitate the degradation of harmful additives, transformation products (such as monoesters in the case of phthalates) can cause a number of adverse health effects, too63. To assess the chemical pollution of the environment by additives emitted from plastics, it is not only necessary to understand the leaching process but to consider the transformation of additives and to account for the effect of environmental factors that have a decisive influence on leaching kinetics and processes. Both aspects must be factored in for a well-founded prediction of the risk of (micro)plastics, otherwise the consequences of exposure will be underestimated.

The release of ortho-phthalates such as DEHP from PVC microplastics has only recently been recognized as a risk to humans and the environment. Our results highlight the risk of long-term release of harmful phthalates and transformation products from PVC microplastics into the aquatic environment, and the identified mass transfer rates can contribute to the adaption of regulations and enforcing restrictions21,64. Ortho-phthalates have been used for decades in various everyday plastic applications, resulting in decades of exposure to aquatic life and humans. In terms of sustainable chemical management, our findings support the need to minimize the release of additives into the environment21. In addition, strategies to reduce the environmental footprint of plastic additives would need to include a reduction of plastic production (as plastics are the intended use of additives), the recovery and recycling of additives, the use of sustainable resources and renewable energy in the additive production, and the replacement of harmful additives with benign and environmentally friendly alternatives that are not harmful at any stage of their life cycle.

Methods

Dry UV-aging of PVC microplastics

Information on all used chemicals and instruments is provided in Supplementary Information S1. In this study, model PVC microplastics purchased from Industrie Generali spa (Samarate, Italy) were used to investigate the influence of photoaging on phthalates leaching. The PVC microplastics (28 ± 0.5 mg per pellet) were spherical with a radius of 2 mm and contained 37.8 wt% of DEHP (C24H38O4)65 determined in the laboratory in our previous study27. DEHP was the only plasticizer identified in the PVC microplastics. Plastic particles detected in the environment can differ from the microplastics used in this study, e.g., in size and shape66. Calculations on the mass transfer processes need to be adjusted accordingly67. In addition, the penetration depth of UV light might vary for particles of different shapes and sizes and requires consideration61. PVC microplastics were artificially photoaged under controlled laboratory conditions according to DIN EN ISO 4892-251. Therefore, a Suntest CPS+ photoaging chamber equipped with a NXe 1500 B xenon lamp (both: Atlas/AMETEK, Linsengericht, Germany) was used. PVC microplastics were placed in two quartz glass Petri dishes, covered with a lid, and placed in the UV chamber for 24 or 48 days. The distance between the pellets was ~0.3 cm. In the UV chamber, PVC microplastics were exposed to a UV spectrum of 300–400 nm, representing the UV radiation of terrestrial systems53. The UV intensity was 65 W m−2. The black standard temperature (BST) and the temperature in the chamber were 65 °C and 40 ± 2 °C, respectively. To ensure microplastics were exposed evenly to UV irradiation in the chamber, Petri dishes were rotated 90° clockwise every 3 days, and the PVC microplastics were turned upside down after half of the total aging time. Regular opening of the Petri dishes ensured sufficient oxygen supply for photooxidation reactions. The accumulated UV irradiation was 135 MJ m−2 after 24 days and 269 MJ m−2 after 48 days. For ambient Central European conditions, about 216 MJ m−2 per year can be assumed68. This means that 24 days and 48 days of artificial photoaging correspond to 7.5 and 15 months of aging in the environment. PVC microplastics are denoted according to the degree of photoaging: pristine PVC microplastics are denoted PVCPristine, PVC microplastics after 24 days and 48 days of photoaging are denoted PVC24d and PVC48d, respectively.

PVC microplastics were thoroughly characterized before and after photoaging to identify the effect of photoaging-induced changes of the polymer on the leaching of DEHP and transformation products. Selected chemical properties of DEHP and its transformation products MEHP (C16H22O4)65, phthalic acid (C8H6O4)65, and phthalic anhydride (C8H4O3)65 are given in Table 3. Details on the respective measurement and characterization of the microplastics are provided in Supplementary Information S2. PVC microplastics were weighed before and after aging. Surface functional groups were determined using Attenuated Total Reflectance-Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR). The content of DEHP and of the transformation products of pristine and photoaged PVC microplastics was determined following the standard and adapted operation procedure for consumer product safety69. The spatial distribution of DEHP in pristine and photoaged PVC microplastics was determined using time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (TOF-SIMS) analysis. The surface area of the PVC microplastics was determined using Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) analysis. The molar mass distribution of the PVC microplastics was measured using Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC), and the glass transition temperature was determined using Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC).

To assess the degree of photoaging of the PVC microplastics, the carbonyl index (ICO) was calculated. ICO describes the ratio between the absorbance of carbonyl groups to the absorbance of a reference group, e.g., the methylene bond and can be determined from ATR-FTIR spectra. ICO can be expressed as follows55:

where AC=O and Aref are the peak area of the carbonyl bond and the reference bond, respectively. For AC=O, the integrated signal at 1610–1830 cm−1 was used. The peak area 1440–1480 cm−1 corresponding to C-H groups was chosen for Aref56. Four to five spectra were evaluated to calculate the mean ICO for each PVC microplastics (Fig. S2.3.1).

Leaching experiments

All glassware was rinsed with ultra-pure water, then with acetone, and heated at 550 °C for 5 h in a muffle oven. Closures were equipped with a Teflon septa. All experiments were conducted using three sample replicates and six blanks (consisting of an infinite sink and the background solution). For the leaching experiments, an infinite sink method was applied. Details on the infinite sink method for phthalate analysis are described elsewhere52. For investigating the leaching of the more hydrophilic transformation products (Table 1), the method was modified (Fig. S1). Briefly, 10 mg of activated carbon was weighed on a piece of filter paper, folded, and the sink was stabilized by a 0.35 mm stainless steel wire. The sinks were equilibrated in 40 mL of 1 mM KCl solution at neutral pH (pH = 6.69 ± 0.16) on a horizontal shaker at 125 rpm overnight. To focus on the effects of photoaging on leaching, potential interference from biotic weathering was excluded by adding sodium azide (50 mg L−1) to the aqueous solutions. 85 ± 0.5 mg of PVC microplastics were added, and the vials were placed on a horizontal shaker at 20 °C until sampling. To avoid photodegradation during the leaching experiments, samples were kept in the dark. At sampling intervals of 1–80 days, first the PVC microplastics and then the infinite sink were taken out with tweezers. For the quantification of DEHP, the infinite sinks were spiked with 1 µg of deuterated internal DEHP-d4 standard. To quantify the transformation products MEHP, phthalic acid and phthalic anhydride, the infinite sinks were additionally spiked with 1 µg of deuterated internal phthalic acid-d4 standard. Sinks were dried at 40 °C and stored in a desiccator until extraction.

DEHP was extracted from the infinite sinks using an accelerated solvent extractor (ASE) at 120 °C using n-hexane as solvent. The transformation products were afterward extracted at 100 °C using methanol as solvent. For the quantification of transformation products in the water phase, 5 mL were spiked with 1 µg of phthalic acid-d4, and 1 mL was filtered with a 0.45 µm cellulose acetate filter in a 1.5 mL brown glass measurement vial. The methanol extracts from the solid-phase extraction were concentrated to 500 µL. The transformation products in the methanol extracts (msink) as well as in the water phase (mw) were quantified using a liquid chromatograph coupled to a triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer (LC-MS/MS) (S1). For the quantification of DEHP in water, 20 mL of the aqueous solution was spiked with 1 µg of DEHP-d4 and extracted using liquid-liquid extraction with three times 5 mL of n-hexane. The extracts were pooled in a 20 mL vial. The hexane extracts were concentrated to 100 µL, and the amount of DEHP in the infinite sink (msink) and in the water phase (mw) were quantified using a gas chromatograph coupled to a triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer (GC-MS/MS) (S1). By conducting the leaching experiments, the mass of DEHP, MEHP, phthalic acid, and phthalic anhydride leached from the PVC microplastics mleach (= msink + mw) was determined. By plotting mleach versus the respective sampling time, time-dependent leaching curves for each compound were obtained. The time-dependent leaching curve of DEHP from PVCPristine has been determined in an earlier study27.

A recovery test was conducted by spiking each 2.5 µg of DEHP, MEHP, phthalic acid, and phthalic anhydride into 40 mL of a 1 mL KCl solution containing the infinite sink. The vials were placed on the horizontal shaker at 125 rpm for 5 days. The experiments were then carried out as described above. The recovery test was conducted using triplicates. The recoveries were 95 ± 9% for DEHP, 98 ± 12% for MEHP, 70 ± 3% for phthalic acid and 92 ± 11% for phthalic anhydride.

To ensure transformation products measured in the framework of the leaching experiments resulted from the photoaging of the PVC microplastics and not from further transformation processes during the leaching experiments, the stability of each compound in water was measured over 24 days using triplicates (S3). MEHP, phthalic acid and phthalic anhydride were stable throughout the experiment, with a recovery of 117 ± 6% for MEHP, 99.6 ± 2% for phthalic acid, and 100 ± 4% for phthalic anhydride (Fig. S3, Table S3).

Leaching process

Phthalates leaching is composed of instantaneous and continuous leaching. Instantaneous leaching results from the diffusion of a compound and the formation of a layer on the surface of the PVC microplastics and, can be obtained from the y-intercept of the time-dependent leaching curves27. Continuous leaching can be determined from the slope of the leaching curves. To exclude the influence of instantaneous leaching for the evaluation of continuous leaching, the mass of DEHP leached instantaneously was subtracted from mleach. Since time-dependent leaching curves for the transformation products were not linear, the y-intercept could not be determined, and the mass leached after 1 day was subtracted from mleach.

Continuous leaching of a compound from PVC microplastics consists of sequential internal and external diffusion processes. The slower of both processes governs the overall diffusion28. The internal diffusion process is called intraparticle diffusion (IPD) and describes the diffusion of a compound within the PVC microplastics. For this experimental set-up using spherical PVC microplastic particles, IPD can be expressed as follows24:

where fdesorbed (-) is the fraction of the compound desorbed at each time t (d), Mt (µg) and M0 (µg) are the mass of the compound in the PVC microplastics at t and the initial mass, respectively, and r is the radius (m) of the PVC microplastics. M0 for DEHP in PVCPristine was known27 and M0 of DEHP in photoaged PVC and of the transformation products was determined in this study. A Taylor number n = 1–10,000 was used to approximate the IPD model. DPVC (m2 s−1) is the diffusion coefficient of the compound in PVC. Based on its relationship with the DEHP content (x) of the PVC microplastics, DPVC was calculated by30:

where DPVCzero (m2 s−1) is the diffusion coefficient of DEHP in PVC with a DEHP content of zero, and a (-) is the plasticization power, indicating the efficiency of DEHP. DPVCzero is 6 × 10−17 m2 s−1 and a is 19.227.

The external diffusion process is called aqueous boundary layer diffusion (ABLD) and describes the diffusion of a compound through an aqueous boundary layer on the surface of the PVC microplastics. For this experimental set-up using spherical PVC microplastics, ABLD can be expressed as follows24:

where Daq (m2 s−1) is the aqueous diffusion coefficient of the compound, δ (m) is the ABL thickness and KPVC/W (L L−1) is the partition coefficient of compound between PVC and water. KPVC/W describes the ratio of the concentration of a compound in PVC (cPVC, µg L−1) to its concentration in water (cw, µg L−1). Using the density of the PVC microplastics, KPVC/W can be converted to L kg−1.

Specific leaching times, such as leaching half-lives, can be calculated when the limiting mass transfer process is known. The leaching half-life expresses the time it takes until 50% of DEHP or of the transformation products have leached from the PVC microplastics. For ABLD-limited leaching, half-lives can be calculated as follows24:

Parameter fitting

The cumulative fraction of DEHP and each transformation product leached from the PVC microplastics over time was evaluated using IPD and ABLD models, and the governing diffusion process was identified. For IPD log DPVC was fitted, and for ABLD log KPVC/W was optimized. Daq of DEHP (= 4.45 × 10−10 m2 s−1) and δ = 38.4 µm for this experimental set-up have been determined in an earlier study27. Daq for MEHP, phthalic acid, and phthalic anhydride were calculated70. All calculations were made in MATLAB R2018a; the tool fminsearch was used for the fitting of the time-dependent leaching data. The sum of the squared differences between the experimental and model values for fdesorbed was chosen as an objective function.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information file).

References

Persson, L. et al. Outside the safe operating space of the planetary boundary for novel entities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 1510–1521 (2022).

Diamond, M. L. et al. Exploring the planetary boundary for chemical pollution. Environ. Int. 78, 8–15 (2015).

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Global Environmental Outlook 5: Environment for the Future We Want, 551 (UNEP, 2012).

Villarrubia-Gómez, P., Cornell, S. E. & Fabres, J. Marine plastic pollution as a planetary boundary threat—the drifting piece in the sustainability puzzle. Mar. Policy 96, 213–220 (2018).

Hahladakis, J. N., Velis, C. A., Weber, R., Iacovidou, E. & Purnell, P. An overview of chemical additives present in plastics: migration, release, fate and environmental impact during their use, disposal and recycling. J. Hazard. Mater. 344, 179–199 (2018).

GESAMP Joint Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection. Sources, Fate and Effects of Microplastics in the Marine Environment: A Global Assessment, Vol. 90, 1–96 (IMO, 2015).

MacLeod, M., Arp, H. P. H., Tekman, M. B. & Jahnke, A. The global threat from plastic pollution. Science 373, 61–65 (2021).

Prata, J. C., da Costa, J. P., Lopes, I., Duarte, A. C. & Rocha-Santos, T. Environmental exposure to microplastics: an overview on possible human health effects. Sci. Total Environ. 702, 134455 (2020).

Koelmans, A. A. et al. Risk assessment of microplastic particles. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7, 138–152 (2022).

Geueke, B. Dossier—Non-Intentionally Added Substances (NIAS), 1–10 (Food Packag. Forum, 2018).

Wiesinger, H., Wang, Z. & Hellweg, S. Deep dive into plastic monomers, additives, and processing aids. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 9339–9351 (2021).

Murphy, J. Additives for Plastics 2nd edn (Elsevier, 2001).

Kwon, J. H., Chang, S., Hong, S. H. & Shim, W. J. Microplastics as a vector of hydrophobic contaminants: importance of hydrophobic additives. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 13, 494–499 (2017).

Tian, Z. et al. A ubiquitous tire rubber–derived chemical induces acute mortality in coho salmon. Science 371, 185–189 (2021).

Merkl, A. & Charles, D. The Price of Plastic Pollution. Social Costs and Corporate Liabilities, 1–48 (Minderoo Foundation, 2022).

Martínez, M. et al. Bisphenol A analogues (BPS and BPF) present a greater obesogenic capacity in 3T3-L1 cell line. Food Chem. Toxicol. 140, 111298 (2020).

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Phthalates Action Plan, 1–16 (EPA, 2012).

da Costa, J. M. et al. Occurrence of phthalates in different food matrices: a systematic review of the main sources of contamination and potential risks. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 22, 2043–2080 (2023).

Wang, W. & Kannan, K. Leaching of phthalates from medical supplies and their implications for exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 7675–7683 (2023).

Net, S., Sempéré, R., Delmont, A., Paluselli, A. & Ouddane, B. Occurrence, fate, behavior and ecotoxicological state of phthalates in different environmental matrices. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 4019–4035 (2015).

European Chemicals Agency (ECHA). Investigation Report on PVC and PVC Additives (ECHA, 2023).

Thompson, J. M., Hsieh, C. H. & Luthy, R. G. Modeling uptake of hydrophobic organic contaminants into polyethylene passive samplers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 2270–2277 (2015).

Seidensticker, S., Zarfl, C., Cirpka, O. A., Fellenberg, G. & Grathwohl, P. Shift in mass transfer of wastewater contaminants from microplastics in the presence of dissolved substances. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 12254–12263 (2017).

Endo, S., Yuyama, M. & Takada, H. Desorption kinetics of hydrophobic organic contaminants from marine plastic pellets. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 74, 125–131 (2013).

Sun, B., Hu, Y., Cheng, H. & Tao, S. Releases of brominated flame retardants (BFRs) from microplastics in aqueous medium: kinetics and molecular-size dependence of diffusion. Water Res. 151, 215–225 (2019).

Lee, H., Byun, D.-E., Kim, J. M. & Kwon, J.-H. Desorption modeling of hydrophobic organic chemicals from plastic sheets using experimentally determined diffusion coefficients in plastics. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 126, 312–317 (2018).

Henkel, C., Hüffer, T. & Hofmann, T. Polyvinyl chloride microplastics leach phthalates into the aquatic environment over decades. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 14507–14516 (2022).

Grathwohl, P. Diffusion in Natural Porous Media: Contaminant Transport, Sorption/Desorption and Dissolution Kinetics 1st edn (ed. Chatwin, P.) (Springer, 1998).

Lohmann, R. Critical review of low-density polyethylene’s partitioning and diffusion coefficients for trace organic contaminants and implications for its use as a passive sampler. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 606–618 (2012).

Wei, X., Linde, E. & Hedenqvist, M. S. Plasticiser loss from plastic or rubber products through diffusion and evaporation. NPJ Mater. Degrad. 3, 18 (2019).

Henkel, C., Lamprecht, J., Hüffer, T. & Hofmann, T. Environmental factors strongly influence the leaching of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate from polyvinyl chloride microplastics. Water Res. 242, 120235 (2023).

Arp, H. P. H. et al. Weathering plastics as a planetary boundary threat: exposure, fate, and hazards. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 7246–7255 (2021).

Lin, J., Yan, D., Fu, J., Chen, Y. & Ou, H. Ultraviolet-C and vacuum ultraviolet inducing surface degradation of microplastics. Water Res. 186, 116360 (2020).

Gewert, B., Plassmann, M. M. & MacLeod, M. Pathways for degradation of plastic polymers floating in the marine environment. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 17, 1513–1521 (2015).

Decker, C. Photodegradation of PVC in Degradation and Stabilisation of PVC (ed. Owen, E. D.) (Springer, 1984).

Feldman, D. Polymer weathering: photo-oxidation. J. Polym. Environ. 10, 163–173 (2002).

Anton-Prinet, C. et al. Photoageing of rigid PVC—II. Degradation thickness profiles. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 60, 275–281 (1998).

Gardette, J. L., Gaumet, S. & Philippart, J. L. Influence of the experimental conditions on the photooxidation of poly(vinyl chloride). J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 48, 1885–1895 (1993).

Zhao, E., Xu, Z., Xiong, X., Hu, H. & Wu, C. The impact of particle size and photoaging on the leaching of phthalates from plastic waste. J. Clean. Prod. 367, 133109 (2022).

Dhavamani, J. et al. The effects of salinity, temperature, and UV irradiation on leaching and adsorption of phthalate esters from polyethylene in seawater. Sci. Total Environ. 838, 155461 (2022).

Papaspyrides, C. D. & Duvis, T. Loss of plasticizers from polymer films to liquid environments: counterdiffusion aspects versus immersion temperature and ultra-violet-induced surface crosslinking. Polymer 31, 1085–1091 (1990).

Yan, Y. et al. Dibutyl phthalate release from polyvinyl chloride microplastics: influence of plastic properties and environmental factors. Water Res. 204, 117597 (2021).

Suhrhoff, T. J. & Scholz-Böttcher, B. M. Qualitative impact of salinity, UV radiation and turbulence on leaching of organic plastic additives from four common plastics—a lab experiment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 102, 84–94 (2016).

Paluselli, A., Fauvelle, V., Galgani, F. & Sempéré, R. Phthalate release from plastic fragments and degradation in seawater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 166–175 (2019).

Hankett, J. M., Collin, W. R. & Chen, Z. Molecular structural changes of plasticized PVC after UV light exposure. J. Phys. Chem. B 117, 16336–16344 (2013).

Stark, T. D., Choi, H. & Diebel, P. W. Influence of plasticizer molecular weight on plasticizer retention in PVC geomembranes. Geosynth. Int. 12, 99–110 (2005).

Archem L. L. C. SPARC Online Calculator. http://archemcalc.com/sparc-web/calc (2022).

Latini, G. Monitoring phthalate exposure in humans. Clin. Chim. Acta 361, 20–29 (2005).

Ito, R. et al. High-throughput determination of mono- and di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate migration from PVC tubing to drugs using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 39, 1036–1041 (2005).

Mathieu-Denoncourt, J., Wallace, S. J., de Solla, S. R. & Langlois, V. S. Influence of lipophilicity on the toxicity of bisphenol A and phthalates to aquatic organisms. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 97, 4–10 (2016).

International Organization for Standardization. ISO 4892-2:2013(E) Plastics—Methods of Exposure to Laboratory Light Sources—Part 2: Xenon-Arc Lamps, 1–13 (2013).

Henkel, C., Hüffer, T. & Hofmann, T. The leaching of phthalates from PVC can be determined with an infinite sink approach. MethodsX 6, 2729–2734 (2019).

Diffey, B. L. Sources and measurement of ultraviolet radiation. Methods 28, 4–13 (2002).

Griffiths, P. J. F., Krikor, K. G. & Park, G. S. Diffusion of additives and plasticizers in poly(vinyl chloride)—III. Diffusion of three phthalate plasticizers in poly(vinyl chloride) in Polymer Additives. Polymer Science and Technology, Vol. 26 (eds Kresta, J. E.) 249–260 (Springer, 1984).

ter Halle, A. et al. To what extent are microplastics from the open ocean weathered? Environ. Pollut. 227, 167–174 (2017).

Liu, H. et al. Ultraviolet light aging properties of PVC/CaCO3 composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 127, 2749–2756 (2013).

Anton-Prinet, C., Mur, G., Gay, M., Audouin, L. & Verdu, J. Change of mechanical properties of rigid poly(vinylchloride) during photochemical ageing. J. Mater. Sci. 34, 379–384 (1999).

Krongauz, V. V., Lee, Y. P. & Bourassa, A. Kinetics of thermal degradation of poly(vinyl chloride): thermogravimetry and spectroscopy. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 106, 139–149 (2011).

Calò, E., Greco, A. & Maffezzoli, A. Effects of diffusion of a naturally-derived plasticizer from soft PVC. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 96, 784–789 (2011).

Ferrahi, M. I. & Belbachir, M. Polycondensation of tetrahydrofuran with phthalic anhydride induced by a proton exchanged montmorillonite clay. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 4, 312–325 (2003).

ter Halle, A. et al. Understanding the fragmentation pattern of marine plastic debris. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 5668–5675 (2016).

Seckmeyer, G. et al. Variability of UV irradiance in Europe. Photochem. Photobiol. 84, 172–179 (2008).

Zhang, Y.-J., Guo, J.-L., Xue, J.-C., Bai, C.-L. & Guo, Y. Phthalate metabolites: characterization, toxicities, global distribution, and exposure assessment. Environ. Pollut. 291, 118106 (2021).

European Commission. Request to the European Chemicals Agency to Prepare an Investigation Report on PVC and PVC Additives. Ref. Ares(2022)3898522, 1–3 (EC, 2022).

Royal Society of Chemistry. Chemspider. http://www.chemspider.com/ (2023).

Mitrano, D. M., Wick, P. & Nowack, B. Placing nanoplastics in the context of global plastic pollution. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 491–500 (2021).

Crank, J. The Mathematics of Diffusion 2nd edn (Oxford Univ. Press, 1975).

Wohlleben, W. et al. NanoRelease: pilot interlaboratory comparison of a weathering protocol applied to resilient and labile polymers with and without embedded carbon nanotubes. Carbon 113, 346–360 (2017).

U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commision (CPSC). Standard Operation Procedure for Determination of Phthalates, 1–8 (CPSC, 2010).

Worch, E. Eine neue gleichung zur berechnung von diffusionskoeffizienten gelöster stoffe (A new equation for the calculation of diffusion coefficients for dissolved substances). Vom Wasser 81, 289–297 (1993).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Eugen Libowitzky for support in obtaining the ATR-FTIR spectra and Martin Stockhausen for support with the BET analysis of the PVC microplastics, and Sefine Oksal Kilinc for assistance in the laboratory conducting the leaching experiments. Charlotte Henkel was funded by the University of Vienna through the research platform Plastics in the Environment and Society (PLENTY). Thilo Hofmann acknowledges funding from the Austrian Science Fund, Cluster of Excellence COE7, Grant 10.55776/COE7. Open access funding is provided by the University of Vienna.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.H., T.Hü. and T.Ho. designed the research. C.H. carried out the leaching experiments and characterization of the pristine and photoaged PVC microplastics. R.P. and C.H. developed the methods to quantify DEHP and its transformation products using GC-MS/MS and LC-MS/MS. X.G. and S.G. analyzed the DEHP distribution in pristine and photoaged PVC microplastics using TOF-SIMS. C.H. evaluated the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. T.Hü. and T.Ho. contributed with discussion of data and results and their revision substantially improved the manuscript. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Henkel, C., Hüffer, T., Peng, R. et al. Photoaging enhances the leaching of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate and transformation products from polyvinyl chloride microplastics into aquatic environments. Commun Chem 7, 218 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-024-01310-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-024-01310-3

This article is cited by

-

Enhanced Leaching of Plasticizers from Polyvinyl Chloride Plastics Weathered by Simulated Solar Light

Water, Air, & Soil Pollution (2026)