Abstract

Many studies of azobenzene photoswitches are carried out in polar aprotic solvents as a first principles characterization of thermal isomerization. Among the most convenient polar aprotic solvents are chlorinated hydrocarbons, such as DCM. However, studies of azobenzene thermal isomerization in such solvents have led to spurious, inconclusive, and irreproducible results, even when scrupulously cleaned and dried, a phenomenon not well understood. We present the results of a comprehensive investigation into the root cause of this problem. We explain how irradiation of an azopyridine photoswitch with UV in DCM acts not just as a trigger for photoisomerization, but protonation of the pyridine moiety through photodecomposition of the solvent. Protonation markedly accelerates the thermal isomerization rate, and DFT calculations demonstrate that the singlet-triplet rotation mechanism assumed for many azo photoswitches is surprisingly abolished. This study implies exploitative advantages of photolytically-generated protons and finally explains the warning against using chlorinated solvent with UV irradiation in isomerization experiments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

“Avoid chlorinated solvents when studying the kinetics of molecular photoswitches”. This well-known axiom is universally accepted in the research community, for doing so will all but guarantee irreproducible, and even counterintuitive, results in switching rates; well-known, but not well understood. This adage is passed down from advisor to graduate student. Researchers share it during coffee breaks at conferences. And some, like us, learned it the hard way. Consequently, reports of photoswitch isomerization kinetics in chlorinated solvents are conspicuously sparse in the literature. In the children’s fable, the tortoise rightfully wins the race. But in the real-life tale of photoswitch isomerization, the hare sometimes, seemingly inexplicably, steals victory. Herein, we definitively explain why.

The most widely studied class of molecular photoswitches1 are the azobenzenes. Beyond their staple applications as dyes in textiles, cosmetics, and food, azobenzenes have unlocked new opportunities in various applied research areas, including photopharmacology, photoresponsive biomaterials, and molecular machines2,3,4. These emerging applications derive from the remarkable light-triggered photoisomerization about the azo bond between stable planar trans and metastable bent cis isomers, which possess distinct shapes, dipole moments, and spectral properties5,6,7. Azobenzenes are additionally classified as T-type photochromes since their isomerization is thermally reversible, typically proceeding in the cis-to-trans direction on timescales spanning several orders of magnitude depending on the ring substitution pattern, as well as local environmental conditions, such as pH6,7. Despite extensive research, the mechanism for thermal isomerization has been heavily contested, where different mechanisms have been proposed, including in-plane inversion, out-of-plane rotation, or a hybrid mechanism of the two6,7. Recent literature findings on unsubstituted azobenzene and other azo derivatives have proposed that thermal isomerization proceeds by a multistate rotation mechanism involving the S0 and T1 potential energy surfaces8,9,10, which provided an explanation for the experimentally observed negative activation entropy of thermal isomerization11. Therefore, our understanding of the thermal isomerization process as a function of substituents and environmental factors is still evolving.

In particular, the thermal isomerization rate plays an important role in determining the ultimate application of a given azobenzene photoswitch. For example, in the design of optical information-transmitting materials12 and photoswitchable ligands regulating protein channel function13, thermal isomerization must occur rapidly, typically in microseconds or less. On the other hand, thermal stability is desirable in applications such as photoswitchable liquid crystal optics14 and on-target selective photoactivation of drugs15 where the photoswitch must behave in an on-off fashion to “lock in” the properties of either isomer for extended periods of time. Indeed, in many biological applications, damage to cells and tissue from intense irradiation required to compete with fast thermal isomerization must be avoided16. An emerging application of azobenzenes even utilizes the thermal isomerization rate as a quantitative readout of the surrounding environment for design of sensor materials17,18.

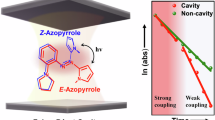

As a major step forward in the development of versatile and smart photoswitch materials, azopyridines have been designed as next-generation photoswitches (Scheme 1) where broad environmental responsivity in the switching behaviour is imparted by the pyridine moiety19. By acquiring the unique Lewis base properties of the pyridine ring otherwise inaccessible to conventional azobenzene, azopyridines have been exploited in various applications, including the photocontrol of liquid crystal phases20,21, pharmacological agents22,23, photodriven oscillators24,25,26, metal complexes27,28, mass transfer29, and molecular spin switches30. However, a major gap exists in understanding the fundamental thermal isomerization kinetics of azopyridines. Limited studies have demonstrated a high propensity for inconsistent results31, while further studies have reported inconsistencies in solubility and reliability32,33 or have measured thermal isomerization kinetics in solvents not explicitly dried, yet where proton transfer processes were possible24. Evidently, something is turning the tortoise into the hare—likely, adventitious protonation is at play.

Although protonation of azopyridines is emerging as an impactful area of interest to reversibly tune the thermal isomerization rate through electronic structure effects, even dedicated studies to elucidate the effect of protonation have drawn contradictory conclusions. For example, in a systematic study investigating the protonation of push-pull azopyridines, Martin et al. demonstrated through quantum chemical calculations that protonation of the pyridine ring shuts down bulk photoisomerization by significantly decreasing the barrier for thermal isomerization and rendering formation of the cis isomer unfavourable34. In another report, however, Ren et al. experimentally observed that photoisomerization of a model azopyridine system was indeed operative at low pH, and the thermal isomerization rate was significantly accelerated from the timescale of hours to a few milliseconds35. Furthermore, in a study of an azopyridine-based humidity sensor, abrupt and inexplicable cusp-like changes occurred in the thermal isomerization rate, delineating distinct fast and slow isomerization regimes36. This plurality of irreproducible and non-reliable results in literature presents a prominent problem in the practical utilization and exploration of engineering applications with these photoswitches. Thus, the effect of protonation, and more broadly of Lewis acids, on the photophysics of azopyridines and, by extension, azobenzenes possessing acid-sensitive groups, still remain to be properly explained.

Over the course of our research exploring applications of azopyridine photoswitching, we were not immune to the erratic kinetic behaviour encountered under seemingly innocuous conditions. Whereas a polar aprotic solvent such as dichloromethane (DCM) should be a convenient and inert solvent for the study of proton-sensitive azo photoswitches, we observed widely inconsistent results when measuring thermal isomerization kinetics of 4-phenylazopyridine (AzPy) in DCM activated with UV light. These anomalies were not present in other alcohol-based and nonpolar solvents, such as ethanol and toluene, which are commonly employed to study the thermal isomerization kinetics of azopyridines. We therefore present herein a concerted experimental and computational investigation which definitively explains this kinetic puzzle in chlorinated solvent. Our results underscore extraordinary susceptibility of azopyridine thermal isomerization towards adventitious catalysis by trace water and protons, even as a consequence of an otherwise routine choice of activation wavelength. This work provides new mechanistic insights into the effect of protonation on the thermal isomerization process. Furthermore, these findings have wider consequences for the characterization of azobenzenes possessing acid-sensitive groups where the thermal isomerization rate is a key element of materials design.

Results and Discussion

365 nm irradiation of AzPy in DCM causes an unexpected spectral redshift

Solutions of AzPy in DCM exhibited a strong absorption band in the UV at 312.5 nm (24000 M−1 cm−1), as well as a weak absorption band in the visible at 452.0 nm (460 M−1 cm−1), corresponding to the \({{{\rm{\pi }}}}\to {{{{\rm{\pi }}}}}^{* }\) and \(n\to {{{{\rm{\pi }}}}}^{* }\) transitions of AzPy, respectively (Figure S4). The locations of these bands were weakly dependent on the choice of solvent (Figure S5) and, like unsubstituted azobenzene, the energetic ordering of the \({{{\rm{\pi }}}}\to {{{{\rm{\pi }}}}}^{* }\) and \(n\to {{{{\rm{\pi }}}}}^{* }\) bands places AzPy identically into the azobenzene spectral class according to the classification scheme proposed by Rau6. In this scheme, the azobenzene class exhibits a low intensity \(n\to {{{{\rm{\pi }}}}}^{* }\) band and high intensity \({{{\rm{\pi }}}}\to {{{{\rm{\pi }}}}}^{* }\) band in the visible and UV regions, respectively, and thermal isomerization typically occurs on the order of several hours. The trans-to-cis photoisomerization of azopyridines is marked experimentally by a loss of intensity of the \({{{\rm{\pi }}}}\to {{{{\rm{\pi }}}}}^{* }\) band, as well as an increase in intensity and blueshift of the \(n\to {{{{\rm{\pi }}}}}^{* }\) band19,31,32,33,34,35,36.

To characterize the photoisomerization process and thermal isomerization kinetics of AzPy, a 60 µM AzPy solution in DCM was irradiated at 365 nm, which falls in the typical UV activation wavelength range for the azopyridine derivatives19,31,32,33,34,35,36. Instead of the typical spectral changes associated with the trans-to-cis photoisomerization process, 365 nm irradiation produced unexpected shifts in the absorption bands which were systematically tracked by UV-visible spectroscopy, as shown in Fig. 1a. Notably, a new peak formed at 340.0 nm alongside a concomitant decrease in intensity of the original \({{{\rm{\pi }}}}\to {{{{\rm{\pi }}}}}^{* }\) band at 312.5 nm, delineated by an isosbestic point at 323.5 nm, as well as two additional isosbestic points in the UV at 236.0 nm and 258.0 nm. Similar changes were observed for the \(n\to {{{{\rm{\pi }}}}}^{* }\) band, shown in the inset of Fig. 1a, where a new peak formed at 473.0 nm. Plotting the variation in absorbance of both UV bands as a function of cumulative UV irradiation time (Fig. 1b) resembled a titration curve where after 6 min of irradiation, no further changes were observed. Repeating the experiment with a visible irradiation wavelength of 450 nm did not produce the observed bathochromic and hyperchromic shifts. Rather, only trans-to-cis photoisomerization was observed (Fig. 1c), as well as competing thermal isomerization occurring during and between steady-state measurements. Systematic 365 nm irradiation of AzPy in other solvents, such as toluene (Figure S6), also produced the expected spectral changes associated solely with isomerization processes. Thus, the anomalous spectral shifts only occurred in DCM, and only when irradiated at 365 nm.

a Irradiation of 60 μM AzPy in DCM by 365 nm light in 15 s intervals. Inset shows the \(n\to {{{{\rm{\pi }}}}}^{* }\) band. b Absorbance of the initial \({{{\rm{\pi }}}}\to {{{{\rm{\pi }}}}}^{* }\) band (312 nm) and the newly formed absorbance peak (340 nm) as a function of 365 nm irradiation time. c Irradiation of 60 μM AzPy in DCM by 450 nm light in 15 s intervals, showing typical trans-to-cis photoisomerization and competing thermal isomerization. Inset shows the \(n\to {{{{\rm{\pi }}}}}^{* }\) band. All UV-vis measurements were performed at 21 °C.

Spectral shifts are caused by adventitious protons generated from UV-mediated photodecomposition of DCM

In a previous report, Wegner and Schweighauser synthesized a macrocyclic azocarbazole whose colour changed from yellow to green when irradiated with 302 nm UV light in chloroform37. This colour change corresponded to formation of a new visible light peak, which could be reproduced by the addition of HCl to solutions of the macrocycle. These observations were attributed mainly to an electron transfer mechanism from excited singlet carbazole to chloroform, however, photolysis of chloroform into soluble products including HCl38 was also discussed. Investigations of the photodecomposition of gaseous DCM by vacuum UV light have shown that the mechanistic pathway is highly dependent on the presence of water and oxygen, however, direct photolysis by UV light can create HCl and other soluble products39. Hypothesizing that UV-mediated protonation was responsible for the observed spectral changes, we titrated solutions of AzPy in DCM with 0.01 mM methanolic HCl, which reproduced the observed bathochromic and hyperchromic shifts in the \({{{\rm{\pi }}}}\to {{{{\rm{\pi }}}}}^{* }\) and \(n\to {{{{\rm{\pi }}}}}^{* }\) bands (Fig. 2a). For more concentrated samples, addition of acid resulted in a visible colour change from yellow to pink (Figure S7). Indeed, methylation25 or protonation34,35 of the pyridine nitrogen in azopyridine derivatives has been shown to cause a redshift of the \({{{\rm{\pi }}}}\to {{{{\rm{\pi }}}}}^{* }\) band due to a strong electron-withdrawing effect created upon the nitrogen acquiring a permanent positive charge. In these studies, however, an electron-donating substituent such as a hydroxyl or alkoxy group was present in the para position of the opposite phenyl ring, which would create a push-pull electronic distribution expected to further enhance the effect6,7. To further support that UV irradiation of DCM results in the generation of protons, 1,8-bis(dimethylamino)naphthalene, known commercially as proton sponge (PS), was employed as a proton scavenger in DCM. Irradiation of 60 µM solutions of PS by 365 nm light produced the characteristic spectral changes associated with protonation of this scavenger40, as shown in Fig. 2b, while 450 nm irradiation did not produce any spectral changes (Figure S8). These results were surprising, since the direct photolysis of DCM typically requires excitation energies larger than the 365 nm irradiation employed here39. However, pyridine and pyridine derivatives are known react with DCM to form bispyridinium adducts under ambient conditions41. It is reasonable that such an adduct formation facilitates the photodecomposition process.

UV-mediated protonation markedly accelerates thermal isomerization of AzPy

These results demonstrate that, due to the strong Brønsted-Lowry basicity of the pyridine ring, the thermal isomerization rate of phenylazopyridines in polar aprotic solvents can be influenced by the presence of protons even in trace concentrations, leading to highly irreproducible measurements with recourse only from scrupulous drying techniques. Initially, trace water in our solvents posed difficulties for measuring the thermal isomerization rate reliably, with intra-sample discrepancies as large as an order of magnitude (Fig. 3, Figure S9, Table S1). Hence, even DCM which has been rigorously dried can still act as a source for adventitious protons in experiments where basic azobenzenes are irradiated by UV light at wavelengths conducive to photoisomerization. Consequently, care must be taken when studying switching kinetics of azobenzenes possessing acid-sensitive groups (such as AzPy discussed here) in DCM, as photoinduced adventitious protonation can markedly interfere with the study.

In their work on the protonation of a cyclotetraazocarbazole, Wegner and Schweighauser carried out further investigations of photoswitch properties in THF37,42. Yet protonation can significantly modulate isomerization processes, and has even been shown to abolish photoisomerization entirely when the protonation site restricts molecular degrees of freedom34,43. Therefore, we sought to fully characterize the effect of UV-induced protonation on the thermal isomerization of AzPy in DCM. A 60 µM solution of AzPy was alternately irradiated by 365 nm light as an intentional proton generator, followed by 450 nm light to trigger trans-to-cis photoisomerization for subsequent measurement of thermal relaxation kinetics, corresponding to excitation of the \(n\to {{{{\rm{\pi }}}}}^{* }\) band. This cyclic dual-wavelength pump scheme is depicted in Fig. 4a, and was repeated for several cycles, beginning with a sample which had not previously been irradiated with UV light as a “baseline” measurement. In solution, thermal isomerization of azobenzenes obeys a first-order rate process described by Eq. (1), where k is the first-order rate constant.

a Schematic representation of a cyclic dual pump scheme for measuring thermal isomerization kinetics of AzPy as a function of 365 nm irradiation. b Thermal isomerization kinetics of 60 μM AzPy in DCM as a function of 365 nm irradiation time. Black dashed line shows kinetic data measured after addition of PS in a 1:1 mole ratio to the final measurement sample (30 s, red curve). Each measurement was performed in duplicate. Each sample curve is normalized to its \({A}_{\infty }\) value. c Kinetic data and overlaid monoexponential fit for the black dashed curve shown in (b) plotted against x-axis extended in time. All UV-vis measurements were performed at 21 °C.

Here, in our case, the measured \(k\) is an effective rate constant convoluting two parallel isomerization processes, corresponding to thermal relaxation of species AzPy and the protonated form, 4-phenylazopyridinium (AzPyH+). This effective rate constant is related to the individual parallel rate constants as derived in the Supplementary Information Section 5.1. By monitoring the absorbance recovery \(A(t)\) of the \({{{\rm{\pi }}}}\to {{{{\rm{\pi }}}}}^{* }\) band as a function of time, the effective rate constant can be extracted from a monoexponential fit to the absorbance-time data, according to Eq. (2), where \({A}_{0}\) is the absorbance immediately after the pump is turned off, and \({A}_{\infty }\) is the absorbance long after the pump has been turned off, i.e. cis-to-trans thermal isomerization has gone to completion (Supplementary Information Section 5.2).

With each subsequent cycle of 365 nm and 450 nm irradiation, the thermal isomerization rate approximately doubled (Fig. 4a, Figure S10, Table S2). Due to temporal limits of our instrument, only initial stages of the acceleration could be observed, which will be rectified in a future instrumental report. After collection of the final (red) curve in Fig. 4b, PS was added to the solution in a 1:1 stoichiometric ratio, and the thermal isomerization kinetics were measured following excitation with a 450 nm light source, shown by the black dashed curve. As a separate control, we verified that irradiation of PS by 450 nm had no effect on the spectral features of the scavenger (Figure S8); therefore, all spectral changes observed could be attributed to the isomerization of AzPy. As shown in Fig. 4b and additionally in Fig. 4c where the x-axis has been extended in time, PS abolished the UV-induced acceleration and recovered the baseline thermal isomerization rate of AzPy (Figure S11, Table S2), in similar agreement with previous literature reports of neutral azopyridines in non-chlorinated polar organic solvents31.

Protonation of AzPy lowers the thermal isomerization barrier and abolishes singlet-triplet crossing mechanisms

To gain further mechanistic insight into the protonation process and the acceleration of the thermal isomerization rate beyond our current instrumental capabilities, we mounted a theoretical investigation of AzPy and AzPyH+ with density functional theory (DFT). The pyridine ring was identified as the primary protonation site of AzPy, as expected, where protonation at either azo nitrogen was significantly less energetically favorable (Table S3, Table S4). Ground state geometries and electronic energies of the cis and trans isomers of AzPy and AzPyH+ are presented in Figure S12 and Table S5, respectively. Available X-ray crystal structures for the AzPy trans isomer44 agree well with DFT-calculated geometries using both the M06-2X and BH&HLYP functionals. Bond lengths and bond angles agree to within 0.05 Å and 2°, respectively, and calculated structures are planar in agreement with crystal structures. To estimate relative rates of thermal isomerization between AzPy and AzPyH+, we investigated the canonical pathways for azobenzene thermal isomerization, shown in Scheme 2. These pathways include inversion through a linear sp-hybridized nitrogen, where for azobenzenes para-substituted with electron acceptor groups (i.e. AzPy, AzPyH+), inversion occurs preferentially through the azo nitrogen nearest the electron acceptor45. Thermal isomerization may also proceed instead through rotation about a partially ruptured azo bond. Torsion about the azo bond is a situation where Kohn-Sham DFT will fail since the wavefunction acquires significant multiconfigurational character near the transition state, necessitating instead multireference approaches11. Indeed, although Martin et al. showed through quantum chemical calculations that protonation renders formation of the cis isomer unfavourable34, thus shutting down photoisomerization in principle, this conclusion was drawn from excited states calculated with an unreliable Kohn-Sham reference state, resulting in disagreement with experiment35. In our work, we employed the spin-flip time-dependent DFT (SF-TDDFT) method46,47, where the functional BH&HLYP, containing 50% Hartree Fock exchange and 50% semilocal B8848 exchange (BH&H) in conjunction with LYP correlation49, is a standard choice50. Moreover, inclusion of dispersion corrections is important for reliably predicting azobenzene thermal isomerization barriers, particularly due to van der Waals stabilization of the cis isomer51.

Previous reports on unsubstituted azobenzene have provided experimental and computational evidence for a multistate or “type II” rotation mechanism8,9 originally proposed by Cembran et al. 52, where spin-orbit coupling drives intersystem crossing between S0 and T1 potential energy surfaces. While the mechanism for thermal isomerization has been contentious for several years, the proposed multistate mechanism provided a resolution for the significant qualitative disagreement between large and negative activation entropies measured by experiment compared to the small and positive activation entropies predicted by quantum chemical calculations and Eyring theory—known as the “entropy puzzle”11. For such a mechanism, the transition state is no longer a first-order saddle point on a single potential energy surface, but rather minimum energy crossing points (MECPs) along the crossing seams of the S0 and T1 surfaces53,54. Given the unfavorable negative activation entropy measured for azopyridine derivatives in previous reports25,31, we suspected that this multistate mechanism may be operative in AzPy, which has not been addressed in existing computational reports55,56. Therefore, we additionally calculated the rotation reaction profile for the T1 surface in both AzPy and AzPyH+—yielding a surprising result.

For both AzPy and AzPyH+, thermal isomerization obeyed a hybrid inversion-rotation mechanism (Fig. 5), where inversion proceeded most favorably through the azo nitrogen nearest the pyridine ring. Inversion instead through the azo nitrogen nearest the phenyl ring was significantly less energetically favourable in both AzPy and AzPyH+ (Figure S13); therefore, this pathway was excluded from further analysis. For rotation of AzPyH+ on S0 (Fig. 5b, orange curve), the CNN angles on both sides of the azo bond were constrained for all optimizations along the reaction coordinate to enforce rotation. Without these additional constraints, calculated structures tended to invert approaching the transition state, causing the dihedral angle to become undefined and the transition state search to fail (Figure S14). For AzPy, the S0 and T1 surfaces crossed at CNNC dihedral angles of approximately 77.5° and 102.5°, with electronic energy barrier heights of 120 kJ mol−1 and 115 kJ mol−1, respectively. Interestingly, the inversion barrier at 112 kJ mol−1 was slightly lower than both MECPs, which would suggest that, energetically, the inversion pathway is more favorable. However, initial calculations of the inversion pathway with Kohn-Sham DFT yielded a positive activation entropy (Supplementary Information Section 6.5, Figure S15, Table S6, Table S7) in clear conflict with experimental reports31, suggesting that the multistate mechanism is in fact principally operative.

a Energy profiles for dihedral rotation and inversion pathways of AzPy calculated with SF-TDDFT at the BH&HLYP-D3(BJ)/def2-QZVPP level. Energies are reported in kJ mol-1 relative to the AzPy cis isomer (\({E}_{{cis}}=-588.6847942\) Hartree) calculated identically with SF-TDDFT. b Energy profiles for dihedral rotation and inversion pathways of AzPyH+ calculated with SF-TDDFT at the BH&HLYP-D3(BJ)/def2-QZVPP level. For rotation on S0, internal CNN angles were additionally constrained to the average of cis and trans geometries (\({\angle {{{\rm{CNN}}}}}_{{{{\rm{pyr}}}}}=121.0^{\circ}\), \({\angle {{{\rm{CNN}}}}}_{{{{\rm{ph}}}}}=119.9^{\circ}\)) to enforce rotation. Energies are reported in kJ mol−1 relative to the AzPyH+ cis isomer (\({E}_{{cis}}=-589.0642227\) Hartree) calculated identically with SF-TDDFT.

For AzPyH+, on the other hand, the multistate reaction mechanism was completely evaded. As seen in Fig. 5b, the S0 and T1 surfaces no longer crossed, with the slight dip in the T1 surface near the 90° dihedral being caused by spin contamination between the S0 and T1 states, which is a limitation of spin-flip methods46,47. Thermal isomerization proceeded for AzPyH+ primarily through inversion of the azo nitrogen nearest the pyridinium ring. We attributed this result to significant weakening of the azo double bond in AzPyH+, discussed in more detail next, which would likely be observed for quaternized azopyridine derivatives and the wider class of push-pull azobenzenes. In addition, the barrier for thermal isomerization was markedly reduced from minimum energy crossing barriers exceeding 100 kJ mol−1 in AzPy to just 25 kJ mol−1 in AzPyH+. While certainly a remarkable reduction in the barrier, we anticipated that polar solvents, such as DCM discussed here, would stabilize the cationic AzPyH+ species, thus retarding the thermal isomerization rate. To further improve our estimation of the barrier for AzPyH+, we additionally evaluated ground state cis and transition state (\(\angle {{{\rm{CNN}}}}=175\)°) geometries in a linear-response polarizable continuum model57,58,59 for DCM as implemented in our chosen quantum chemistry software Orca60, which predicted a heightened barrier of 62 kJ mol−1. Using a simple Arrhenius model, and assuming a barrier height of 120 kJ mol−1 for AzPy (MECP1), we calculated 6 orders of magnitude acceleration in the thermal isomerization rate upon protonation. Indeed, push-pull azopyridines where the pyridine nitrogen acquired a permanent positive charge from protonation35 or quaternization25,35 produced photoswitches with short cis half-lives on millisecond or microsecond timescales, respectively. Evidently, from the experimental results presented herein, as well as efforts to design rapidly isomerizing photoswitches, adventitious protonation is capable of significantly altering the thermal isomerization kinetics of AzPy which can be undesirable in several applications predicated on the precise control of these kinetics.

Initially, we expected that resonance stabilization of a linear transition state in AzPyH+ was principally responsible for the observed acceleration in the thermal isomerization rate, as shown in Scheme 3. However, in silico analysis of bond lengths, bond orders, and formal charges in the trans and cis isomers of AzPy and AzPyH+ (Table S8) revealed that neither resonance stabilization of a linear transition state nor resonance weakening of the azo bond (Scheme 3) were significant.

Shifting focus instead to the molecular orbitals (MO) of AzPy and AzPyH+, the \({{{\rm{\pi }}}}\)-bonding (HOMO) orbital of AzPyH+ was polarized towards the pyridinium ring compared to AzPy, as shown in Fig. 6. To explore weakening of the azo double bond, we devised a hypothetical isodesmic reaction (Scheme 4) to estimate the energy of reaction for breaking the azo bond. In an isodesmic reaction, the number and type of bonds are preserved, while only their mutual relationships change61. As a result, these reactions can probe deviations from the additivity of bond energies, such as resonance stabilization, and can take advantage of cancellation of bond-specific errors on both sides of the reaction.

The calculated enthalpy of reaction at 298.15 K was 37.9 kJ mol−1 and 46.4 kJ mol−1 for the trans and cis isomers respectively (Table S9), demonstrating that partial breaking of the azo linkage was favorable in AzPyH+. These enthalpies were also a significant fraction of the barrier drop for AzPy compared to AzPyH+. We concluded that the azo bond is instead weakened by an inductive effect, which would facilitate rotation, as observed from the difference in energy between rotation on S0 of AzPy (Fig. 5a) and AzPyH+ (Fig. 5b), even as AzPyH+ was subject to additional geometry constraints. AzPyH+ demonstrates similar character to push-pull azobenzene systems, wherein electron delocalization across the entire structure favors partial breaking of the azo linkage6,7, which poses protonation as a reversible tool to tune the thermal isomerization rate in azopyridines over several orders of magnitude. Our ongoing work focuses on the contribution of inversion mechanisms to the acceleration of thermal isomerization in AzPyH+ using other wavefunction and quantum chemical methods.

Conclusion

In this work, we provide a definitive explanation for anomalous azopyridine photoswitching in DCM as an archetypal chlorinated solvent. Through a concerted experimental and theoretical treatment, we unveil the mechanistic underpinnings of reversible protonation of the pyridine ring of AzPy in DCM triggered by long-wave UV irradiation otherwise intended to activate photoisomerization. Even trace quantities of proton photo-generated by DCM induce a profound acceleration in the thermal isomerization rate. Surprisingly, this acceleration is caused by a weak inductive effect rather than resonance effects which are commonly invoked to rationalize changes in the thermal isomerization rate. This inductive effect withdraws electron density from the azo bond, enabling more facile rotation in the protonated form. In addition, protonation shuts down the multistate singlet-triplet rotation mechanism in AzPy, underscoring the complexity of the thermal isomerization process and the necessity to thoroughly and rigorously consider various mechanisms in quantum chemical treatments of isomerization. Although routine experimental conditions generate two distinct and unequal photoswitch species in solution—a tortoise and a hare—addition of a proton scavenger reversed the acceleration, restoring the rightful victory of the tortoise. More broadly, our results demonstrate that thermal isomerization of azopyridine photoswitches, a prominent photoswitch in materials applications, may be generally tuned by protonation, including photolytically-generated protons, over several orders of magnitude. This study has further implications for reconciling inconsistent, unreliable, and even contradictory reports of azopyridine thermal isomerization, pointing toward a root cause of adventitious protonation and proton transfer mechanisms capable of significantly perturbing the thermal isomerization rate in this highly sensitive class of azo photoswitches.

Methods

Materials

Toluene (ACS reagent grade), pyridine (ReagentPlus®, ≥ 99.5%), DCM (Uvasol®, spectroscopic grade), 0.5 M methanolic HCl solution, and chloroform-d (99.8 atom % D) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. DCM (ACS reagent grade), cyclohexane (ACS reagent grade), ethyl acetate (ACS reagent grade), ethanol (ACS reagent grade, 95%), and methanol (ACS reagent grade) were purchased from Fisher. THF (reagent) was purchased from Caledon. Tetramethylammonium hydroxide solution (ACS reagent), 4-aminopyridine (98%), nitrosobenzene (≥ 97%), and 1,8-bis(dimethylamino)naphthalene (99%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All solvents and reagents were used without further purification unless otherwise specified.

1H NMR characterization data was collected at 296 K on a Bruker ARX 400 MHz Spectrometer, internally referenced to the residual CDCl3 solvent signal (7.26 ppm). Infrared (IR) spectra were recorded using a Bruker Alpha-Platinum ATR FTIR spectrometer with a diamond crystal.

Synthesis of 4-Phenylazopyridine

4-Phenylazopyridine was synthesized by a modification of the procedure by Bannwarth et al. 62. In brief, 25 mL of pyridine was added to a solution of 2.00 g (21.2 mmol) of 4-aminopyridine in 25 mL of 20% aqueous tetramethylammonium hydroxide, and then heated to 80 °C. A solution of 3.00 g (28.0 mmol) of nitrosobenzene in 25 mL of pyridine was then added over a period of 1 h, and the reaction mixture was stirred at 80 °C for an additional hour. The solution was cooled to RT and extracted with dry toluene (4 × 50 mL). The toluene extracts were combined and washed with sat NaCl(aq), dried over anh MgSO4, and filtered. The toluene was stripped by vacuum rotary evaporation, yielding a dark red solid. This crude residue was dissolved in reagent grade DCM and was purified by column chromatography on Sigma-Aldrich (230–400 mesh) 60 Å irregular silica gel with 2:1 cyclohexane/ethyl acetate as the eluent. Yield: 1.94 g (50%) orange powder. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): d = 8.81–8.82 (dd, 2H), 7.96–7.98 (m, 2H), 7.71–7.72 (dd, 2H), 7.55–7.56 (m, 3H) (Figure S1). IR (neat): n = 1443, 1474, 1565, 1583, 1704 cm-1 (Figure S2).

UV-visible spectroscopy and acid titrations

Spectroscopic grade DCM (Sigma-Aldrich) was used for all electronic spectra. Steady-state and time-resolved UV-visible spectra were collected with a Varian Cary Bio 100 UV-vis spectrophotometer in Fisher macro cell quartz cuvettes (10 mm path length, 200 nm–2500 nm) capped with a PTFE stopper to prevent solvent evaporation. UV photometric titrations were performed by preparing solutions of 60 µM AzPy in DCM. Solutions were irradiated by a 365 nm LED (ams-OSRAM USA Inc., 10 nm FWHM) or 450 nm LED (New Energy, 10 nm FWHM) in 15 s intervals, and UV-visible spectra were collected between each irradiation. The optical power at the sample was measured to be 104 mW and 56 mW for the 365 nm and 450 nm excitation LEDs, respectively, using a Thorlabs Integrating Sphere Photodiode Power Sensor (S142C, 350 nm–1100 nm). Acid titrations were performed similarly by preparing solutions of 60 µM AzPy and a requisite amount of 0.01 M methanolic HCl in DCM. Methanolic HCl solution microvolumes were added to a 2.5 mL volume of AzPy in 10 µL increments with a 25 µL glass syringe; in total, 50 µL of acid was added. UV-visible spectra were collected between each addition. Thermal isomerization kinetics were measured by pumping 60 µM AzPy solutions prepared in DCM with a 450 nm LED for 4 min, and then monitoring sample absorbance at the peak of the \(\pi \to {\pi }^{* }\) band (312 nm–313 nm). A schematic for the custom pump-probe spectroscopy instrument is shown in Figure S3. All spectroscopic measurements were performed at 21 °C. All data figures were prepared in MATLABTM and monoexponential fits to isomerization kinetic data were computed with the MATLABTM Curve Fitting Toolbox.

Quantum chemical calculations

DFT calculations were performed using the Orca 5.0.3 software63,64,65. Exchange and Coulomb integrals were evaluated in the Resolution of Identity (RI) approximation66 with chain-of-spheres (RIJCOSX)67 and a corresponding def2/J auxiliary basis set68. First protonation stages of cis and trans geometries and isodesmic reaction enthalpies were calculated in the gas phase with the M06-2X functional69 and def2-QZVPP basis set70. Optimized structures were verified as true minima by vibrational analysis71 which returned only real frequencies.

Transition state searches for CNNC dihedral rotation and inversion thermal isomerization pathways were calculated with the SF-TDDFT method46,47 in the Tamm-Dancoff approximation72 with the “Becke half-and-half” BH&HLYP functional48,49 and def2-QZVPP basis set70, including D3(BJ) dispersion correction73,74. Angles and dihedrals were incremented in steps of 10°, and then 5° or less approaching the transition state. For thermal isomerization pathways proceeding on a single potential energy surface, the transition state geometry was taken as the highest-energy structure along the reaction coordinate. Energetic barriers for thermal isomerization were reported relative to the ground state cis geometry, which was calculated with SF-TDDFT at an identical theory level to the transition state search. Electronic structure properties of ground state cis and trans geometries (i.e. population analysis and MOs) were evaluated with the Kohn-Sham wavefunction. All structures, vibrational modes, and MOs were visualized with Chemcraft (https://www.chemcraftprog.com)75.

Data availability

Additional supplementary methods, figures, data, and discussion supporting the findings in the main text are available in the Supplementary Information. All data relating to figures in the main text and Supplementary Information are available upon request from the authors. Cartesian coordinates of relevant calculated structures discussed in the main text and Supplementary Information are provided as a text file in Supplementary Data 1.

References

Dürr, H. & Bouas-Laurent, H. Photochromism: Molecules and Systems (Elsevier, 2003).

Hüll, K., Morstein, J. & Trauner, D. In vivo photopharmacology. Chem. Rev. 118, 10710–10747 (2018).

Abendroth, J. M., Bushuyev, O. S., Weiss, P. S. & Barrett, C. J. Controlling motion at the nanoscale: rise of the molecular machines. ACS Nano. 9, 7746–7768 (2015).

Chang, V. Y., Fedele, C., Priimagi, A., Shishido, A. & Barrett, C. J. Photoreversible soft azo dye materials: toward optical control of bio-interfaces. Adv. Optical Mater. 7, 1900091 (2019).

Jerca, F. A., Jerca, V. V. & Hoogenboom, R. Advances and opportunities in the exciting world of azobenzenes. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 51–69 (2022).

Rau, H. Photochemistry and Photophysics Ch. 4 (CRC Press, 1990).

Bandara, H. M. D. & Burdette, S. C. Photoisomerization in different classes of azobenzene. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 1809–1825 (2012).

Reimann, M., Teichmann, E., Hecht, S. & Kaupp, M. Solving the azobenzene entropy puzzle: direct evidence for multi-state reactivity. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 13, 10882–10888 (2022).

Axelrod, S., Shakhnovich, E. & Gómez-Bombarelli, R. Thermal half-lives of azobenzene derivatives: virtual screening based on intersystem crossing using a machine learning potential. ACS Cent. Sci. 9, 166–176 (2023).

Singer, N. K., Schlögl, K., Zobel, J. P., Mihovilovic, M. D. & González, L. Singlet and triplet pathways determine the thermal Z/E isomerization of an arylazopyrazole-based photoswitch. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 14, 8956–8961 (2023).

Rietze, C., Titov, E., Lindner, S. & Saalfrank, P. Thermal isomerization of azobenzenes: on the performance of Eyring transition state theory. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 29, 314002 (2017).

Garcia-Amorós, J. & Velasco, D. Recent advances towards azobenzene-based light-driven real-time information-transmitting materials. Beilstein J. Org. 8, 1003–1017 (2012).

Kienzler, M. A. et al. A red-shifted fast-relaxing azobenzene photoswitch for visible light control of an ionotropic glutamate receptor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 17683–17686 (2013).

Bang, C.-U., Shishido, A. & Ikeda, T. Azobenzene liquid-crystalline polymer for optical switching of grating waveguide couplers with a flat surface. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 28, 1040–1044 (2007).

Weston, C. E. et al. Toward photopharmacological antimicrobial chemotherapy using photoswitchable amidohydrolase inhibitors. ACS Infect. Dis. 3, 152–161 (2017).

Beharry, A. A. & Woolley, G. A. Azobenzene photoswitches for biomolecules. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 4422–4437 (2011).

Fedele, C., Ruoko, T.-P., Kuntze, K., Virkki, M. & Priimagi, A. New tricks and emerging applications from contemporary azobenzene research. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 21, 1719–1734 (2022).

Poutanen, M., Ahmed, Z., Rautkari, L., Ikkala, O. & Priimagi, A. Thermal isomerization of hydroxyazobenzenes as a platform for vapor sensing. ACS Macro. Lett. 7, 381–386 (2018).

Ren, H., Yang, P. & Winnik, F. M. Azopyridine: a smart photo- and chemo-responsive substituent for polymers and supramolecular assemblies. Polym. Chem. 11, 5955–5961 (2020).

Cui, L. & Zhao, Y. Azopyridine side chain polymers: an efficient way to prepare photoactive liquid crystalline materials through self-assembly. Chem. Mater. 16, 2076–2082 (2004).

Yu, H., Liu, H. & Kobayashi, T. Fabrication and photoresponse of supramolecular liquid-crystalline microparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 3, 1333–1340 (2011).

Pittolo, S. et al. An allosteric modulator to control endogenous G protein-coupled receptors with light. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 813–815 (2014).

Qiao, Z. et al. Photosensitive and photoswitchable TRPA1 agonists optically control pain through channel desensitization. J. Med. Chem. 64, 16282–16292 (2021).

Garcia-Amorós, J., Nonell, S. & Velasco, D. Photo-driven optical oscillators in the kHz range based on push-pull hydroxyazopyridines. Chem. Commun. 47, 4022–4024 (2011).

Garcia-Amorós, J., Massad, W. A., Nonell, S. & Velasco, D. Fast isomerizing methyl iodide azopyridinium salts for molecular switches. Org. Lett. 12, 3514–3517 (2010).

Garcia-Amorós, J., Díaz-Lobo, M., Nonell, S. & Velasco, D. Fastest thermal isomerization of an azobenzene for nanosecond photoswitching applications under physiological conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 12820–12823 (2012).

Liu, G. et al. Control on the dimensions and supramolecular chirality of self-assemblies through light and metal ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 16275–16283 (2018).

Peng, B. et al. A photoresponsive azopyridine-based supramolecular elastomer for self-healing strain sensors. Chem. Eng. J. 395, 125079 (2020).

Gelebart, A. H. et al. Making waves in a photoactive polymer film. Nature 546, 632–636 (2017).

Venkataramani, S. et al. Magnetic bistability of molecules in homogeneous solution at room temperature. Science 331, 445–448 (2011).

Brown, E. V. & Granneman, G. R. Cis-trans isomerism in the pyridyl analogs of azobenzene. A kinetic and molecular orbital analysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 97, 621–627 (1975).

Bujak, K. et al. Fast dark cis-trans isomerization of azopyridine derivatives in comparison to their azobenzene analogues: experimental and computational study. Dyes Pigm. 160, 654–662 (2019).

Konieczkowska, J. et al. Kinetics of the dark cis-trans isomerization of azobenzene and azo pyridine derivatives in ethanol and chloroform solutions. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A. 444, 114979 (2023).

Martin, S. M. et al. The doorstop proton: acid-controlled photoisomerization in pyridine-based azo dyes. N. J. Chem. 47, 11882–11889 (2023).

Ren, H., Qiu, X.-P., Shi, Y., Yang, P. & Winnik, F. M. pH-dependent morphology and photoresponse of azopyridine-terminated poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) nanoparticles in water. Macromolecules 52, 2939–2948 (2019).

Patrakka, J. Azobenzene photoisomerization in humidity sensing. Master’s thesis (Tampere University, Tampere, 2020).

Schweighauser, L. & Wegner, H. A. Cyclotetraazocarbazole – a multichromic molecule. Chem. Commun. 49, 4397–4399 (2013).

Ottolenghi, M. & Stein, G. The radiation chemistry of chloroform. Radiat. Res. 14, 281–290 (1961).

Yu, J. et al. Conversion characteristics and mechanism analysis of gaseous dichloromethane degraded by a VUV light in different reaction media. J. Environ. Sci. 24, 1777–1784 (2012).

Alder, R. W., Bowman, P. S., Steele, W. R. S. & Winterman, D. R. The remarkable basicity of 1,8-bis(dimethylamino)naphthalene. Chem. Commun. (London). 723–724 https://doi.org/10.1039/C19680000723 (1968).

Rudine, A. B., Walter, M. G. & Wamser, C. C. Reaction of dichloromethane with pyridine derivatives under ambient conditions. J. Org. Chem. 75, 4292–4295 (2010).

Schweighauser, L., Häussinger, D., Neuburger, M. & Wegner, H. A. Symmetry as a new element to control molecular switches. Org. Biomol. Chem. 12, 3371–3379 (2014).

Thongchai, I.-A. et al. Acid violet 3: a base-activated water-soluble photoswitch. J. Phys. Chem. A. 128, 785–791 (2024).

Hutchins, K. M., Groeneman, R. H., Reinheimer, E. W., Swenson, D. C. & MacGillivray, L. R. Achieving dynamic behaviour and thermal expansion in the organic solid state via co-crystallization. Chem. Sci. 6, 4717–4722 (2015).

Dokić, J. et al. Quantum chemical investigation of thermal cis-to-trans isomerization of azobenzene derivatives: substituent effects, solvent effects, and comparison to experimental data. J. Phys. Chem. A. 113, 6763–6773 (2009).

Shao, Y., Head-Gordon, M. & Krylov, A. I. The spin-flip approach within time-dependent density functional theory: theory and applications to diradicals. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 4807–4818 (2003).

Casanova, D. & Krylov, A. I. Spin-flip methods in quantum chemistry. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 22, 4326–4342 (2020).

Becke, A. D. Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Phys. Rev. A. 38, 3098 (1988).

Lee, C., Yang, W. & Parr, R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 37, 785–789 (1988).

Li, Z. & Liu, W. Theoretical and numerical assessments of spin-flip time-dependent density functional theory. J. Chem. Phys. 136, 024107 (2012).

Schweighauser, L., Strauss, M. A., Bellotto, S. & Wegner, H. A. Attraction or repulsion? London dispersion forces control azobenzene switches. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 13436–13439 (2015).

Cembran, A., Bernardi, F., Garavelli, M., Gagliardi, L. & Orlandi, G. On the mechanism of the cis-trans isomerization in the lowest electronic states of azobenzene: S0, S1, and T1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 3234–3243 (2004).

Harvey, J. N. Understanding the kinetics of spin-forbidden chemical reactions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 9, 331–343 (2007).

Lykhin, A. O., Kaliakin, D. S., dePolo, G. E., Kuzubov, A. A. & Varganov, S. A. Nonadiabatic transition state theory: application to intersystem crossings in the active sites of metal-sulfur proteins. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 116, 750–761 (2016).

Wang, L., Yi, C., Zou, H., Xu, J. & Xu, W. Theoretical study on the isomerization mechanisms of phenylazopyridine on S0 and S1 states. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 22, 888–896 (2009).

Casellas, J., Alcover-Fortuny, G., De Graaf, C. & Reguero, M. Phenylazopyridine as switch in photochemical reactions. A detailed computational description of the mechanism of its photoisomerization. Materials 10, 1342 (2017).

Miertuš, S., Scrocco, E. & Tomasi, J. Electrostatic interaction of a solute with a continuum. A direct utilization of AB initio molecular potentials for the prevision of solvent effects. Chem. Phys. 55, 117–129 (1981).

Cammi, R. & Mennucci, B. Linear response theory for the polarizable continuum model. J. Chem. Phys. 110, 9877–9886 (1999).

Cossi, M. & Barone, V. Time-dependent density functional theory for molecules in liquid solutions. J. Chem. Phys. 115, 4708–4717 (2001).

Barone, V. & Cossi, M. Quantum calculation of molecular energies and energy gradients in solution by a conductor solvent model. J. Phys. Chem. A. 102, 1995–2001 (1998).

Hehre, W. J., Ditchfield, R., Radom, L. & Pople, J. A. Molecular orbital theory of the electronic structure of organic compounds. V. Molecular theory of bond separation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 92, 4796–4801 (1970).

Bannwarth, A. et al. Fe(III) spin-crossover complexes with photoisomerizable ligands: experimental and theoretical studies on the ligand-driven light-induced spin change effect. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 2776–2783 (2012).

Neese, F. The ORCA program system. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2, 73–78 (2012).

Neese, F. Software update: the ORCA program system, version 4.0. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 8, e1327 (2017).

Neese, F., Wennmohs, F., Becker, U. & Riplinger, C. The ORCA quantum chemistry program package. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 224108 (2020).

Weigend, F. A fully direct RI-HF algorithm: implementation, optimised auxiliary basis sets, demonstration of accuracy and efficiency. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 4, 4285–4291 (2002).

Neese, F., Wennmohs, F., Hansen, A. & Becker, U. Efficient, approximate and parallel Hartree-Fock and hybrid DFT calculations. A ‘chain-of-spheres’ algorithm for the Hartree-Fock exchange. Chem. Phys. 356, 98–109 (2009).

Weigend, F. Accurate coulomb-fitting basis sets for H to Rn. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 8, 1057–1065 (2006).

Zhao, Y. & Truhlar, D. G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Account. 120, 215–241 (2008).

Weigend, F. & Ahlrichs, R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 7, 3297–3305 (2005).

Bykov, D. et al. Efficient implementation of the analytic second derivatives of Hartree-Fock and hybrid DFT energies: a detailed analysis of different approximations. Mol. Phys. 113, 1961–1977 (2015).

Hirata, S. & Head-Gordon, M. Time-dependent density functional theory within the Tamm-Dancoff approximation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 314, 291–299 (1999).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1456–1465 (2011).

Chemcraft - graphical software for visualization of quantum chemistry computations. Version 1.8, build 682.

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (DGECR-2020-06539, ALLRP 570902-21), Canada Foundation for Innovation (12939, 41723). We also thank the Canada First Research Excellence Fund (CFREF-2015-00013 and CFREF-2022-00010) programs. We thank Dr. Howard Hunter and Prof. Demian Ifa (Department of Chemistry, York University), and Dr. Christopher W. Schruder (Department of Physics and Astronomy, York University) for synthesis and characterization resources. We also thank Prof. Tao Zeng (Department of Chemistry, York University) for helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CH: conceptualization, experimental and theoretical data curation, formal analysis, methodology, validation, investigation, visualization, writing – original draft, review & editing. SR: chemical synthesis and characterization data curation, formal analysis, methodology, validation, investigation, writing – review & editing. CB: conceptualization, methodology, validation, project administration, funding acquisition, resources, supervision, writing – review & editing. WP: conceptualization, methodology, validation, project administration, funding acquisition, resources, supervision, writing – review & editing. OM: conceptualization, methodology, validation, project administration, funding acquisition, resources, supervision, writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hillel, C., Rough, S., Barrett, C.J. et al. A cautionary tale of basic azo photoswitching in dichloromethane finally explained. Commun Chem 7, 250 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-024-01321-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-024-01321-0