Abstract

The interplay between attractive London dispersion forces and steric effects due to repulsive forces resulting from the Pauli principle often determines the geometry and stability of nanostructures. Aromatic polyimides (PI) and carbon nanotubes (CNT) were chosen as building blocks as two components in the hetero delocalized electron nanostructures. Two PIs, having the same diamine part and different linkage substituents between two phenyl rings of dianhydride part, one linked with ether bond (C-O-C) (OPI), the other with C-(CF3)2 (FPI), were investigated. Surprisingly, two CNT/PI nanocomposites show distinct failure mode from CNT yielding to CNT pull-out failure. Calculation of the interaction energy and chain conformations of each PI upon CNT was performed by accurate density functional theory (DFT) calculations and molecular dynamic simulation (MDS). OPI chain adopt helically wrapping conformation around CNT with relatively strong interaction energy. FPI chain take the one-side wavelike conformation upon CNT with relatively weak interaction energy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atoms and molecules drives the assembly of building blocks with preferred conformations at the nanoscale within the noncovalent complexes, which proceed into the diverse architectures at macroscale1,2,3,4. London dispersion forces are present for all matter starting from atoms (e.g., the condensation of helium) over molecules (e.g., aggregation) to larger nanostructures and even macroscopic objects materials (e.g., adhesion). London dispersion forces play a vital role in binding, the thermodynamic stability of molecules in condensed phases, chemical selectivity through transition-state stabilization, the formation of molecular crystals5,6, protein folding, drug binding, self-assembly of supramolecular complexes, molecular recognition, complex nanostructures, biological systems, and composites structures. London dispersion forces reflect an inherently quantum mechanical phenomenon that arise from electrodynamic correlations between instantaneous charge fluctuations in matter7,8,9. London dispersion (LD) interactions formally describe the attractive part of the van-der-Waals (vdW) potential and were first established by Fritz London to rationalize the condensation of noble gases10. London dispersion forces were underappreciated for a long time because the individual interactions between pairs of atoms are relatively weak (about 2 kJ mol−1). However, for the large molecules and increasingly larger structures, due to collective many-body fluctuation, London dispersion forces are on the order of tens of kilocalories per mole, which is sufficient to markedly influence their physical, chemical, and mechanical properties. Recently, the synergy of experiment and theory has reached a stage where dispersion effects can be examined in fine detail and precise calculation methods of London dispersion forces have been developed9,11,12,13,14,15. Many-body effects have been employed to describe the London dispersion forces for explaining when compact or extended linear arrangements are preferred to give significant many-body effects, and how cooperative effects provide enhanced stability in helices making them one of the most common structures in biomolecules16,17,18. London dispersion forces between polarizable nonmetallic nanostructures can be more completely understood in terms of collective interactions between wavelike charge density fluctuations, rather than simply by a summation over pairwise interactions between instantaneous particle- or fragment-like dipolar fluctuations9.

Different from London dispersion forces which play the role of an attractive force in the chemical reactivity, biosystems and nanostructures, steric effects usually contribute a repulsive force. The original notion of a steric effect and its influence on the molecular structure was first formulated by T. L. Hill and F.H. Westheimer in the 1930s19,20,21. Steric effects arise from a consequence of the space required to accommodate the atoms and groups in a molecular system or hetero molecule complexes, and are often thought to arise from overlapping electron densities22. The steric effect will be conformationally dependent, and it is probable that the minimal steric interaction principle will be observed. This principle states that a substituent whose steric effect is conformationally dependent, will prefer that conformation which minimizes steric repulsions and which will give rise to the smallest steric effects23.

In recent years, there has been growing interest in studying the interplay between London dispersion and steric effects in hybrid nanostructure with delocalized electrons, nanoscale system and in exploring the intermolecular interaction energy12. The interplay of London dispersion forces and steric effects can be observed in different fields, such as aromatic interactions24, chemical reactivity, including diastereoselectivity25,26, molecular conformation1,27,28,29,30,31, interaction energy32. Interaction energy between the building blocks constituting a molecule determines not only the physicochemical properties of noncovalent complexes, clusters, and condensed molecular matter but also the structure and mechanics and other physical properties of larger molecules23,33,34,35. In large systems like noncovalent nanocomposites, interfacial interaction energy or interfacial bonding at the molecular level plays an important role in enabling high load transfer efficiency, leading to the overall improved mechanical performance of such composites36,37,38,39,40,41.

To address this issue of interplay between steric effects and London dispersion forces, we investigated a two-component system, in which London dispersion forces drive the assembly of two molecules with delocalized electron different chemical structure while steric hindrances constrain such tendency. We note that London dispersion forces play a dominant role in delocalized π electron systems. One type of such system is characterized by extensively delocalized π electrons, such as carbon nanotube, graphene, another type is formed by aromatic ring-containing polymers, like phenyl-ring-containing polymer, such as aromatic polyimides. Attractive interactions between them may influence conformer preference to maximize attractive interactions between carbon nanotube and aromatic ring-containing polymer. Steric effects arise by introducing side bulk groups into the backbone of aromatic polymers tend to be repulsive, which impose conformers allowing to minimizing these steric repulsive interactions. Carbon nanotubes, cylindrical molecules that consist of rolled-up sheets of single-layer carbon atoms (graphene), display outstanding electric mechanical, and thermal properties. There, unsaturated π orbitals in the plane of the graphene sheet perpendicular to the CNT surface form a delocalized π electrons network across the nanotube. The unique nature of CNT cylindrical structures with different rolling-up direction endows them with extraordinary material properties, such as thermal and electrical properties, stiffness, strength, and toughness. Due to the excellent thermal stability, dielectric and mechanical properties, aromatic polyimides reinforced with CNTs have been developed as promising noncovalent complexes for the application in fields of microelectronics and advanced aerospace vehicles. The hexagonal arrangement in the graphene sheet of CNTs is isomorphic to the wrapping atomic arrangement of carbon atoms in the aromatic rings on the polyimide backbone, therefore aromatic rings tend to interact with nanotubes strongly via London dispersion forces and form an ordered assembly of PI strands on the surface of nanotubes. However, due to differences in geometry (planar, cylinder, cone, sphere), flexibility (rigid, flexible, semi-rigid), chemical structure and chirality, tailoring noncovalent interactions within multi-component systems becomes extremely complicated. Interactions between PI strands adsorbed on the underlying hexagonal graphene sheet are determined not only by local London dispersion forces, the overall PI chain geometry, and flexibility, but also by the steric effects generated by bulky side groups in the PI backbone.

We studied two nanostructured systems consisting of two different aromatic polyimides with embedded carbon nanotubes having delocalized electrons. The chosen two PIs have the same diamine part but different linkage substituents between two phenyl rings of the dianhydride part. One is linked with ether bonds (C–O–C) (labeled as OPI), the other one is linked with C–(CF3)2 bonds (labeled as FPI) (Fig. 1). Their fragments are shown in Fig. 2. We studied the mechanical properties of CNT/OPI and CNT/FPI nanocomposites. Using quantum chemical and molecular dynamics calculations, we elucidated the experimentally observed properties of these nanocomposites. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study on CNT/PI nanocomposites that addresses the issue of interplay between London dispersion forces and steric effects.

Results

Experimental

The failure behavior of the two nanocomposites, in which two polyimides with the similar chemical structure were reinforced with carbon nanotubes, was monitored by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and stress–strain curves to compare the change in terms of interaction energy and local fracture morphology after failure under uniaxial tension. The stress–strain curves of the nanocomposite film are shown in Fig. 3.

The results of mechanical tests of the obtained films demonstrated significantly higher values of the CNT/OPI nanocomposite compared to those of the CNT/FPI nanocomposite. For example, the specific fracture toughness values of CNT/OPI and CNT/FPI nanocomposite films are 75.3 MJ m−3 and 18.8 MJ m−3, respectively, and the elongations at break of the CNT/OPI and CNT/FPI nanocomposite films are 38% and 15%, respectively. This distinction in the mechanical properties indicates significant differences in the behavior of the compared materials under the action of mechanical loads. For the two types of the polymer matrix, it was confirmed that these differences are significantly influenced by the interactions of polymers with the filler, i.e., the same nanotubes. It is the degree of compatibilization of nanotubes with the surrounding polymer that contributes to the enhancement of material properties42.

The efficiency of the compatibilization of the components of the nanocomposite, the level of interaction between the nanotube surface and the surrounding polymer chains, combined with the homogeneity of nanotubes distribution in the material volume achieved during the composite fabrication, can be evaluated by comparing the stiffness of the nanocomposite film with the stiffness of the appropriate unfilled polymer material, i.e., by comparing the values of their elastic modulus E. For the materials considered in this work, the value of the ratio Enanocomposite/Eunfilled PI is 1.24 for CNT/OPI and only 1.09 for CNT/FPI.

Obviously, compared to the CNT/FPI system, the rigid framework of nanotubes and structural integrity of the surrounding polymers in the CNT/OPI system are much more effective in absorbing the external load applied to the film and redistributing it over the material volume. A substantial difference in stiffness values of two nanocomposite materials is also observed during further deformation of the films (Fig. 3). Indeed, the stress–strain curve of the CNT/OPI film is situated noticeably higher than that of the CNT/FPI film. This seems to indicate that the difference in the intensity of the interaction between the two PIs and nanotubes persists until the material fracture.

To carry out a direct study on the nature of the interactions between nanotubes and two polymer matrices, SEM methods were used, i.e., Micrographs of the fracture surfaces of the nanocomposite films were compared. Figure 4 demonstrates a significant difference in the morphological characteristics of the two nanocomposites. The SEM micrograph for CNT/FPI (Fig. 4a) shows a smooth appearance of the fracture surface, characteristic for quasi-brittle fracture. Long fragments of CNTs were pulled out of the polymer matrix in the course of the elongation process of the sample, clearly seen on the fracture surface, as well as pores, i.e., traces remaining of pulled-out nanotubes which can be observed on the opposite fracture surface of the sample. At a higher magnification (Fig. 4c), the pore surrounding the partially pulled-out nanotube is clearly visible. The presence of such pores evidently indicates the lack of strong interaction between the components of the nanocomposite, i.e., the lack of sufficient adhesion of polymer chains to the surface of the nanotube. This is also evidenced by the appearance of nanotubes that were obviously pulled out of the matrix under the applied stress, which agrees well with the stress–strain curve shown in Fig. 3. This resulting surface morphology of the material indicates that during deformation there is no effective stress transfer from the PI matrix to the nanotubes, suggesting that the polymer chains have poor contact with the surface of the nanoparticles. On the contrary, micrographs of the CNT/OPI nanocomposite fracture surface show pronounced traces of plastic flow of the material before fracture (Fig. 4b). Strong adhesion of polyimide molecules to nanotubes can deduce from the fact that until fracture CNTs were tightly enveloped by polymer layer (Fig. 4d), implying high-stress transfer from the polymer matrix to the nanotubes. The nanotubes in this composite did not detach from the matrix polymer up to the ultimate elongation. The appearance of this characteristic fracture surface, indicating the co-movement of polymer and nanotubes, is consistent with the stress–strain curve shown in Fig. 3. In summary, our experimental results under uniaxial tension show two different deformation and fracture mechanisms that significantly affect the strength and energy dissipation in the system: the CNT pulling-out mechanism, which occurs at the interface between CNTs and FPI; and the combined deformation of both nanocomposite components, which is realized within the OPI matrix without breaking the contact between the components. The exchange of substituents in the chemical structure from ether bond to C(CF3)2 led to a fundamental change in the modes of deformation and fracture, which is due to differences in interaction strength between CNTs and polyimide molecules.

Quantum chemistry calculations

Interactions of monomers (OPI and FPI) with a CNT sheet

The interaction energies of the polyimide monomers OPI and FPI with CNTs were calculated on model systems using CNT sheet and at B3LYP-D3/6-31 G* level, as described in Methods. To obtain representative conformers of the polyimide monomers OPI and FPI, conformational analysis of the monomers was done by calculating relaxed energy profiles for three critical torsion angles (Fig. SI 1). The resulting profiles show that the highest energy barrier for OPI is 2.4 kcal mol−1 (Fig. SI 2) and for FPI is 3.8 kcal mol−1 (Fig. SI 3). The higher energy barrier for t2 and t3 torsions of FPI are the consequence of the bulky CF3 groups.

The low-energy barriers between different conformers indicate the possibility for a large number of conformers, but also suggest that the conformation of the monomer can be changed easily. To illustrate possible interactions of polyimide monomers with CNT sheets, four optimized conformers were chosen to calculate interaction energies between a polyimide monomer and a CNT sheet. The largest CNT-24 sheet (described in “Methods”) was used for all calculations with polyimide monomers. Minimized geometries using one representative geometry for each polyimide monomer are shown in Fig. 5, while other conformations can be found in the Supplementary Information (Fig. SI 4). These optimized geometries were used to calculate interaction energies at the B3LYP-D3/6−31 G* level. The values of interaction energies of representative monomers with CNT (Fig. 5) as well as the range of values obtained for other monomers shown (Fig. SI 4) are presented in Table 1.

The results for the interaction energy of OPI with a CNT-24 sheet show that the different monomer conformations lead to very similar interaction energies in the range from −45.21 to −46.64 kcal mol−1 (Table 1), even though monomers are positioned differently on the CNT surface (Fig. 5). For FPI monomers, interaction energies lay in the wider range from −38.45 to −42.31 kcal mol−1 (Table 1).

The most important conclusion is that compared to FPI monomers, OPI monomers showed consistently stronger interaction energies with the CNT sheet, indicating stronger binding, which is in accordance with the experimental data. All OPI monomers were oriented strongly parallel to the CNT sheet. However, because of the CF3 groups, parallel placement of the FPI monomers was impeded, as shown in Fig. 6.

Using the smaller fragments R1-R5 (Fig. 2), it was shown that parallel orientation is crucial for strengthening the interaction between a molecule and a CNT (Fig. SI). It was also shown that heteroatoms do not contribute significantly to the strengthening of the total interaction energy. This was proven for the benzene (R1), which out of all R fragments has the strongest value of energy per electron (E/ne). Moreover, the electrostatic potential of the CNT sheet is very uniform, leading to the conclusion that changes in the electrostatic potential caused by heteroatoms do not have a significant impact on the interaction energy between a molecule and a CNT sheet.

Therefore, dispersion interactions are expected to be the leading attractive interaction term between polyimide monomers and the CNT sheet. Unfortunately, full PI/CNT systems are too large for energy decomposition analysis. Thus, a complementary analysis is performed on representative smaller parts of the polyimide monomers, using also a smaller CNT sheet.

Energy decomposition analysis: Interactions of R1 + R2, R3 + R5, and R4 + R5 fragments with the CNT sheet

To elucidate the nature of PI/CNT interactions, each polyimide monomer was split into two parts: first part, R1 + R2, which is the same for both OPI and FPI monomers, and the second part, R3 + R5 for OPI, and R4 + R5 for FPI, respectively (Fig. 2). Each fragment was first optimized, and these coordinates were used to construct the interactions of these fragments with CNT-17. These fragment/CNT-17 systems were optimized by molecular mechanics (MM) using a general Amber force field (GAFF). For R4 + R5 molecule, two conformations were used. The geometries obtained by the minimization (Fig. 6) were used to calculate the interaction energies of fragments R1 + R2, R3 + R5, and R4 + R5 with CNT-17 (Table 2).

The data in Table 2 show that R1 + R2 fragment has the weakest interaction energy of around −20.5 kcal mol−1 with a CNT sheet, what can be anticipated as this fragment is the smallest one. Also, this fragment is common for both monomers (Fig. 1). Fragment R3 + R5 has the strongest interaction energy with a CNT sheet of around −27.0 kcal mol−1 (Table 2). Two different conformers of R4 + R5 fragment bind with similar interaction energies of around −23.0 kcal mol−1. The interaction energy of R3 + R5 (part of OPI monomer) being stronger than R4 + R5 (part of FPI monomer) agrees well with the conclusions about OPI being more strongly bonded to the CNT than FPI (Table 1). Hence, these data confirm that the presence of CF3 groups in FPI polyamine causes the difference in binding and behavior of OPI and FPI polyimide polymers.

Xiamen energy decomposition analysis (XEDA) reveals that for all four systems, the most attractive term is the dispersion, followed by the much weaker electrostatics, and lastly polarization as the weakest. This proves the previous conclusions based on the uniformity of the CNT sheet electrostatic potential surface about the interactions being mostly based on dispersion. Another interesting finding is that even though R1 + R2 molecule has all the attractive terms significantly stronger than the ones for R4 + R5 conformers, a much lower value of the exchange-repulsion terms for R4 + R5 conformers, as this molecule is not able to take the parallel position above the CNT sheet, leading to R4 + R5 having 3.0 kcal mol−1 stronger total interaction energy with the CNT than R1 + R2.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation of preferred chain conformation wrapping around CNT

To further investigate the chain conformation at the surface of CNT and help elucidate the nature of the failure morphology of PI/CNT complex, MD was employed to simulate the molecular dynamic interactions of a PI chain of 10 monomers with a CNT (diameter, 2 nm) and to obtain the preferred conformation of two PI chains on the CNT surface.

Before running the procedure of interacting a polyimide chain with CNT via Materials Studio (MS), we constructed in the MS program the PI monomer with preferred conformation as the initial chain for MD study of a PI chain interacting with the CNT, as shown in Fig. 7a, b. The OPI monomer displays a more curved preferred conformation than that of the FPI monomer. This difference is further confirmed by the preferred conformation of two PIs having 10 monomers each, as shown in the Fig. 8a, b, respectively. Both PI chains show helical structure as their preferred conformation. Compared with the chain of FPI, the chain of OPI has a low pitch and a high helix radius. Both PIs with 10 monomers each and CNTs were placed in the same simulation unit within the Universal Force Field (UFF) under the Periodic Boundary Condition, respectively. After MD simulation, the preferred conformation of PI on the CNT surface was obtained. In the case of FPI, the FPI-10 monomer chains take a wavelike conformation on one side of CNT wall which arose by the tilted orientation of FPI monomer with respect to CNT, as shown in Fig. 8c. Thus, FPI failed to adopt a helical conformation wrapping around CNTs. This particular conformation results in a low interface energy between FPI and the surface of the CNTs, which is consistent with the results of Fig. 6 and Tables 1 and 2. Furthermore, the conformation of FPI chain also implies loose contact between delocalized π electrons of CNTs and the π electron clouds of the PI’s aromatic rings.

The results of the simulated conformation clarify the morphology of the pull-out of CNT failure mode, as shown in Fig. 4a, c. On the contrary, in the case of OPI, the 10-monomer polyimide chain adopts a helical conformation wrapped around the CNT favored by the parallel orientation of OPI monomers with respect to the CNT surface, as shown in Fig. 8d. As such “wrapping”, we anticipate a stronger interfacial energy in accordance with quantum chemical calculations (Tables 1 and 2). Furthermore, this unique conformation clarifies the nature of the corresponding failure mode implying plastic polymer flow, as shown in Fig. 4b, d.

Discussion

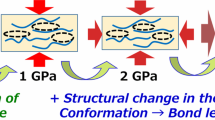

Noncovalent interactions between nanofillers and polymer matrix control composite interfaces play an important role in determining properties of nanocomposites. The here studied CNT/PI nanocomposites were synthesized by in situ polymerization in the presence of carbon nanotubes. Due to the rigidity and big diameter of the carbon nanotubes, the polyimide chain can be regarded as assembling on a rigid carbon substrate, driven by the London dispersion between the delocalized π electrons of the aromatic phenyl ring and heteroaromatic benzoxazole rings and strongly delocalized π electrons of carbon nanotubes. In the presence of a carbon nanotube, attractive London dispersion between delocalized π electrons in the benzene ring and benzoxazole ring in the polyimides and their counterpart in the carbon nanotubes can help the polyimides to overcome the energy barrier for undergoing large conformational changes leading to stable and ordered wrapping structure around CNTs. CNT/benzoxazole ring containing polyimide hybrid nanocomposites indicate strong interactions at the interfaces between carbon nanotubes and benzoxazole rings. The surrounding polyimide molecules or segments around a carbon nanotube, either FPI or OPI, experience changes in conformation due to the interaction with carbon nanotubes. In the case of OPI and CNT complexes, the R1, R2, R5 fragments containing aromatic rings have a strong London dispersion interaction with carbon nanotubes. There, due to the relatively small size of the O atoms in the R3 fragment, the impact of the steric hindrance imposed by the ether bond is smaller compared to the impact of delocalized π electrons along the PI main chain. Therefore, an approximately helical conformation of PI chains around CNT is preferred, with aromatic ring oriented parallel to the CNT surface. On the contrary, in the case of (CF3)2-groups, the R1, R2 and R5 parts of monomer chains favor the London dispersion with CNT, while the R4 with a bulky CF3-C-CF3 group, the CF3 groups in the FPI are larger than O atom in the OPI, imposing strong steric repulsion. Thus, the symmetrical and bulky structure of –C(CF3)2 determines that the 6FDA (4,4’-hexafluoroisopropylidene diphthalic anhydride) moiety possesses a high rotational barrier, resulting in the infeasible free rotation around the Ph–C(CF3)2 bond. The London dispersion of aromatic ring and heteroaromatic ring in the R1, R2, R5 fragments with π electrons in the CNT attract the polymer backbone including R4 to the surface of CNTs. However, as the rigid -C(CF3)2 groups approach the extensively delocalized π electrons of carbon nanotubes, the Pauli repulsion increases dramatically and outweighs the attractive London dispersion forces due to the nature of steep distance dependence of Pauli repulsion caused by the overlap of CF3 orbital and π orbital of CNT. Even though the local dipole-dipole interaction between the atom F of hexafluoroisopropylidene ( − C(CF3)2 − ) and π electrons of the CNT does contribute to the attractive interactions of the complexes, its contribution is smaller compared to the London dispersion interaction of the PI backbone with π electrons of CNT. Therefore, R4 with (CF3)2 adopted a tilted conformation as compromise between the attraction interactions of R1, R2, R3 fragments with CNT, and the Pauli repulsion of R4 fragment with CNT. Additionally, FPI would have a less delocalized π-electron density than OPI, resulting in a preferred conformation which is nonplanar. Steric hindrance effects are significant when rigid and bulky functional groups are added to the backbone because the larger groups make chain rearrangement more difficult as the hexafluoropropylene group (CF3)2 restricts torsional motion of chain segments. The FPI chain failed to form a helical conformation around CNT surface. The interplay between London dispersion and steric effects leads to strain imposed by steric constraints, which increase the distance between PI main chain and CNT, and lower the interaction energy between them. Thus, the FPI chain fails to wrap around the CNT.

To elucidate details of the interactions between CNT and PI at the molecular level, we performed quantum chemical and molecular dynamic calculations. The interaction energy of OPI and FPI monomers with model system of CNT show stronger interaction of OPI monomer, the interaction energies for OPI monomer are in the range −46.64 to −45.51 kcal mol−1, while the interaction energies for FPI monomer are in the range −42.31 to −38.45 kcal mol−1 (Table 1). The difference in the interaction energies is the consequence of the geometries of the monomers; while OPI monomers can adopt planar conformations, FPI monomers cannot adopt planar conformation, since steric repulsion of the –C(CF3)2 group prevents planarization. Consequently, OPI chains with 10 monomers adopt a helical conformation allowing for wrapping around CNTs, while FPI chains with 10 monomers take a wavelike conformation on one side of CNT, failing to helically wrap around CNTs.

The energy decomposition analysis of the fragments of the monomers (Fig. 6) shows that the main contribution to the interaction energy results from dispersion interactions (Table 2). In the case of FPI fragments (R4 + R5), both interaction energy and dispersion component are less attractive in comparison to OPI fragments (R3 + R5), caused by the nonparallel orientation of FPI fragments (Fig. 6). Molecular dynamics calculations showed better interactions for OPI with CNTs than for FPI with CNTs (Fig. 8c, d). Based on our calculations, a comprehensive understanding of the interplay between steric effects and London dispersion forces on the properties of the CNT/OPI and CNT/FPI films is achieved. The –O atom in OPI determines the planar conformation of OPI on CNTs, which enables parallel orientation of OPI around CNT and strong dispersion interaction energy. This strong interaction explains the strong mechanical properties of CNT/OPI. The –C(CF3)2–group in FPI results in strong steric repulsion, which causes that the conformation of FPI is not planar, preventing parallel orientation of the FPI on the CNT surface. Consequently, the distance between FPI and CNT is somewhat larger and the dispersion interaction energy is lower.

From research on microfiber-reinforced, nanofiber-reinforced composites over the past decades, it is well-established that the structure and properties of fiber-matrix interfaces play a major role in determining the mechanical performance and structural integrity of such composite materials. Strong interfacial binding is a necessary condition for successfully transferring external load across the interface between fibers or CNTs and the surrounding polymer matrix. Under an applied tensile force, the tensile stress generated in the nanocomposite film is transferred through shear between graphene sheets of CNT and the surrounding PI molecules layer. The value of interfacial shear strength increases with increasing interfacial interaction strength by an approximately linear scaling relationship.

Failure modes have a great impact on energy dissipation in the nanocomposite system, which directly controls the toughness. Therefore, the fracture toughness is governed by interfacial interaction energy between CNT and surrounding polyimide layers, related to PI chain conformations around CNT. In the case of CNT/FPI nanocomposite films, the energy required to fracture the nanocomposite is mainly governed by the weak interfacial interaction energy, allowing for easy sliding of CNTs past the surrounding polyimide layer. On the contrary, in the case of CNT/OPI, the yielding mode of failure involves the breaking of carbon nanotubes. Thus, the energy required to fracture CNT/OPI nanocomposites is much higher, implying that a tremendous amount of energy can be dissipated upon tensile loading. The strong interfacial interaction energy between CNTs and surrounding PI molecules is related to the preferred helical chain conformation.

Our experimental data on CNT/OPI and CNT/FPI nanocomposite films show significant differences in the behavior of the two films. The results of mechanical tests of CNT/OPI and CNT/FPI nanocomposite films show that CNT/OPI is stronger than CNT/FPI. The specific fracture toughness values of CNT/OPI and CNT/FPI nanocomposite films are 75.3 MJ m−3 and 18.8 MJ m−3, respectively. The corresponding elongations at break for CNT/OPI and CNT/FPI nanocomposite films are 38% and 15%, respectively. In addition, the stress–strain curve of the CNT/OPI film is higher than that of the CNT/FPI film (Fig. 3). All these data indicate stronger interactions between CNT and OPI than between CNT and FPI. The influence of contact between CNT and PI on the strength of the nanocomposite films was experimentally supported by microscopic SEM images. Namely, SEM micrographs of the fracture surfaces of nanocomposite films (Fig. 4) indicate different fracture processes for CNT/OPI and CNT/FPI films. The SEM micrograph for CNT/FPI (Fig. 4a, c) showed the fracture surface with long fragments of CNTs pulled out of the polymer matrix in the uniaxial deformation process. On the other hand, SEM micrographs of the CNT/OPI nanocomposite showed the fracture surface with pronounced traces of plastic flow of the material before fracture (Fig. 4b, d), indicating strong adhesion of polyimide molecules to nanotubes until fracture.

Conclusions

We have performed systematic studies on appropriately designed systems which allowed to shed light on the impact of specific types of substituents within the polyimide monomers on the geometry and energy of noncovalent interactions. Differences in the mechanical behavior and the local fracture morphology after uniaxial tension are a consequence of the impact of the substituents. In our work, we used two aromatic PIs, FPI and OPI, and CNTs as building blocks, which allowed to form specific hetero nanostructures in the investigated nanocomposites. Our quantum chemical calculations showed differences in geometry and interaction energy of OPI and FPI with the CNT. In the CNT/OPI system, interactions were stronger than in CNT/FPI. Namely, for the OPI monomer, the calculated interaction energies at the B3LYP-D3/6-31 G* level for two PI conformers with a part of the nanotube were in the range −46.64 to −45.51 kcal mol−1, while for the FPI monomer, the interaction energies were in the range −42.31 to −38.45 kcal mol−1. Also, quantum chemical calculations showed that the most important contribution to the total interaction energy resulted from dispersion interactions. Our theoretical computational study of molecular dynamics suggests that two separate fracture mechanisms be distinguished in terms of different chain conformation and corresponding interactions with CNT. The two polyimides with different substituent groups adopt different interactions with carbon nanotubes. OPI monomers have ether bond substituents parallel to the CNT surface. OPI chains adopt helically wrapping conformation around CNT with relatively strong interaction energy between OPI and CNT. The helically wrapping conformation favors close contacts between extensively delocalized π electrons of CNTs and the π electron clouds from the aromatic rings of the PIs. By contrast, the rigid nature of symmetric and bulky –C(CF3)2 groups of FPI prevents parallel orientation with the CNT surface. Namely, the steric constraints of the –C(CF3)2 groups prevent planar conformations of FPI monomers, resulting in a tilted orientation with respect to the CNT surface, which, in turn, results in relatively weak interactions between FPI and CNT. Consequently, FPI chains take the wavelike conformation upon one side of CNT. The one-side wavelike conformation leads to a lowered contact between the extensively delocalized π electrons of CNTs and π electron cloud from the aromatic rings of PIs. The synergetic effect of interaction energy and chain conformation leads to different stress transfer efficiency and structural integrity, and consequently different failure modes, CNT pull-out failure and CNT yielding failure.

We attribute this interesting structure-mechanical property relationship to a complex interplay between the steric strain hindering rotation of polymer main chain introduced by bulky substituents along the backbone, which caused strong Pauli repulsion and the concerted rotations along the polymer backbone around carbon nanotubes driven by London dispersion forces. London dispersion forces and Pauli repulsion arise from different mechanisms, electron correlations for dispersion interactions and the Pauli exclusion principle for exchange repulsion. There is no straightforward connection between these interactions and both can be varied independently. Further works will improve our understanding further on how London dispersion forces and Pauli exclusion at atom level affect and control the formation and the strength of nanostructures.

Methods

Experimental

Materials and synthesis methods

The CNTs had been synthesized by catalytic chemical vapor deposition (CVD technology) with an outer diameter ranging from 2 nm to 30 nm, and a length of 10–20 μm, obtained from Chengdu Organic Chemicals Co. Ltd., Chinese Academy of Science. The 5-amino-2-(p-aminophenyl) benzoxazole (AAPB, purity 99.71%, melting point 230.0 °C–230.6 °C), 4,4’-oxydiphthalic anhydride (ODPA, purity 99.7%, melting point 227.3 °C) and 4,4’-hexafluoroisopropylidene diphthalic anhydride (6FDA, Fluorochem) are of high purity to meet the chemical reaction requirements. N, N-dimethylacetamide (DMAc) was distilled before use. CNT-reinforced PI nanocomposites were synthesized by in situ polymerization of diamine and dianhydride in the presence of CNTs. AAPB was dissolved in DMAc at room temperature and then sonicated after adding multi-walled CNTs. The dilute CNT suspension was obtained by sonication for 3 h at 47 kHz. The suspension was immediately transferred to a nitrogen-purged three-neck round bottom flask equipped with a mechanical stirrer and drying tube outlet filled with calcium sulfate. After stirring the CNTs dispersion, ODPA was added. The reaction mixture was sonicated in a bath sonicator while simultaneously being stirred for 6 h at 300 rpm at room temperature. The solution viscosity increased and stabilized, which indicate that CNT-poly (amic acid) (PAA) solution was synthesized. The DMAc solutions of PAA (with or without CNTs) were cast onto clean glass plates and dried in a dry air-flowing chamber for 10 h at 90 °C. Then the films, with a thickness of 40–60 μm, were step-wise cured in vacuum at temperatures up to 350 °C to obtain fully imidized, solvent-free CNT/PI films. In this work, the impact of CNT was evaluated for a loading concentration of c = 0.5 wt% CNTs relative to PI. The polyimide nanocomposites based on 6FDA and AAPB reinforced with CNTs were also synthesized along the above-described procedures.

Characterization

The tensile tests of the films with the dimensions of 2*30 mm2 were carried out in the uniaxial extension mode using a universal mechanical test system UTS-10 (Germany) at room temperature according to ASTM D638. A scanning electron microscope (SEM, Quanta 200 F) was used to characterize the morphology of the fracture surfaces of 0.5 wt% CNT/FPI and 0.5 wt% CNT/OPI nanocomposite films. The samples were sputter-coated with a thin layer (ca. 3 nm) of gold (Au) prior to SEM imaging to decrease the charging effect under the SEM analysis.

Computational methods

Quantum chemistry calculations of interaction energies

Both polyimide monomers, OPI and FPI (Fig. 1) were optimized, and different conformations were obtained. Relaxed scan calculations were done for three critical torsion angles for both OPI and FPI monomers to estimate energy barriers for conformational changes (Fig. SI). Four conformations of each polyimide monomer were chosen for further calculations. All quantum chemical calculations were performed at B3LYP-D3/6-31 G*43,44,45 using the Gaussian 09 program package46.

Since polyimide monomers and the corresponding carbon nanotubes are too large for a detailed analysis, each monomer was split into four fragments out of the following five: R1, R2, R3, R4, and R5, where R3 is present only in OPI, and R4 only in FPI monomer (Fig. 2a). Along the same lines, OPI and FPI monomers were also split into two parts, namely, R1 + R2 and R3 + R5 for OPI, and R1 + R2 and R4 + R5 for FPI (Fig. 2b). Full geometry optimization was done for these molecules, and resulting optimized geometries (conformations) were used for the further calculations.

Armchair (222,222) type CNT with a diameter of 30.1 nm was chosen, and its atomic coordinates were obtained using the Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD) Nanotube builder plugin. Using only a part of the nanotube surface for calculations was justified not only by computational cost, but also by the size ratio between the nanotube and fragment/monomer. VMD obtained CNT was cut into curved sheets of different dimensions and saturated with hydrogens. Every model system considered consisted of a CNT sheet with frozen coordinates and a monomer or its part. The coordinates of CNT sheets were kept frozen in every calculation to preserve its curvature and mimic that the sheet was only a part of a larger and more rigid nanotube. The choice of the CNT sheet size for the calculation depends on the complexity of the method and the size of the molecule that was attached to it. The following CNT sheet sizes were used: CNT-24 ( ≈ 24 × 24 Å, 296 atoms, 252 C atoms), CNT-20 ( ≈ 20 × 20 Å, 206 atoms, 170 C atoms), CNT-17 ( ≈ 17×17 Å, 174 atoms, 142 C atoms), and CNT-13 ( ≈ 13 × 13 Å, 106 atoms, 82 C atoms) (Supplementary Information, Figure SI 4–6).

Coordinates and interaction energies between fragments and CNT were obtained using two different approaches. In the first, fully quantum chemical approach, fragments were placed parallel to the CNT and interaction energies at the B3LYP-D3/6-31 G* level were calculated for different values of normal (separation) distance (R). Starting from the geometry with the strongest interaction energy, geometry optimization was performed with frozen CNT coordinates. Finally, the interaction energy was calculated for the optimized geometry. All interaction energies in this work are corrected for the basis set superposition error (BSSE) using the counterpoise keyword. This approach was applied to R1, R2, R3, R4, and R5 fragments.

In the second approach, molecular mechanics (MM) energy minimization was used to obtain the coordinates for quantum chemical interaction energy calculations. System preparation was done using the AmberTools20 programs47. The general Amber force field (GAFF)48 and AM1-BCC charges49,50 were used for the energy minimization in NAMD software51, where CNT was kept frozen during the minimization. The final coordinates given by MM were used for the calculation of interaction energy between each fragment and a CNT sheet at B3LYP-D3/6-31 G* level. This approach was done for both monomers and their parts.

The accuracy of the second approach was verified by comparing the results for R1-R5 fragments to the first approach interaction energies. By comparing the results for the two approaches (Tables SI 1 and 2), one can notice the slightly larger normal distances for MM minimization-derived geometries, causing these geometries to give somewhat weaker interactions. However, the interaction energy differences are small, so the usage of the MM minimization approach is justified for larger systems.

Energy decomposition analysis

Xiamen energy decomposition analysis (XEDA)52,53 was done for R1-R5 fragments and for the two fragment halves of the monomers (R1 + R2, R3 + R5, and R4 + R5) with the CNT sheets. This method decomposes the DFT interaction energies (Etot) into the following decomposition terms: electrostatics (Eel), exchange (Eex) and repulsion (Erep), usually represented as the addition of the two (Eex+Erep=Eex,rep), polarization (Epol), electron correlation (Ecorr), and Grimme’s dispersion (ED3), both summarized as the dispersion term (Ecorr + ED3 = Edisp).

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation that probed the chain conformation change after interacting with CNT was conducted. A two-dimensional model of the FPI 10-mer, the OPI 10-mer with 10 repeated monomer units and a carbon nanotube (diameter 20 Å) was constructed. The preferred conformation of the two PIs related to CNT was performed as the PI strand interacted with CNT. The generation is fulfilled by the Amorphous Cell Packing task in BIOVIA Materials Studio (MS)54,55.

Data availability

All relevant data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

Vaccarelli, O. et al. Quantum-mechanical force balance between multipolar dispersion and Pauli repulsion in atomic van der Waals dimers. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 033181 (2021).

Srinivasan, R. & Rose, G. D. A physical basis for protein secondary structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 14258–14263 (1999).

Becker, J., Allen, W. D. & Schreiner, P. R. Probing the delicate balance between Pauli repulsion and London dispersion with triphenyl methyl derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 11421 (2018).

Burley, S. K. & Petsko, G. A. Aromatic-aromatic interaction: a mechanism of protein structure stabilization. Science 229, 23–28 (1985).

Hoja, J. et al. Reliable and practical computational description of molecular crystal polymorphs. Sci. Adv. 5, 3338 (2019).

Rosel, S. et al. London dispersion enables the shortest intermolecular hydrocarbon H…H contact. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 7428–7431 (2017).

Karimpour, M. R., Fedorov, D. V. & Tkatchenko, A. Quantum framework for describing retarded and nonretarded molecular interactions in external electric fields. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 013011 (2022).

Prasoon, A. et al. On-water surface synthesis of electronically coupled 2D polyimide-MoS2 van der Waals heterostructure. Commun. Chem. 6, 280 (2023).

Ambrosetti, A. et al. Wavelike charge density fluctuations and van der Waals interactions at the nanoscale. Science 351, 1171–1176 (2016).

London, F. Zur Theorie und Systematik der Molekularkräfte. Z. f.ür. Phys. 63, 245–279 (1930).

Bursch, M. et al. Understanding and quantifying London dispersion effects in organometallic complexes. Acc. Chem. Res. 52, 258–266 (2018).

Lima, C. F. et al. Experimental support for the role of dispersion forces in aromatic interactions. Chem. A Eur. J. 18, 8934–8943 (2012).

Wagner, J. P. & Schreiner, P. R. London dispersion in molecular chemistry–reconsidering steric effects. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 12274–12296 (2015).

Liptrot, D. J. & Power, P. P. London dispersion forces in sterically crowded inorganic and organometallic molecules. Nat. Rev. Chem. 1, 0004 (2017).

Ehrlich, S., Moellmann, J. & Grimme, S. Dispersion-corrected density functional theory for aromatic interactions in complex systems. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 916–926 (2013).

Ouyang, J. F. & Bettens, R. P. A. When are many-body effects significant? J. Chem. Theory Comput. 12, 5860–5867 (2016).

DiStasio, R. A. Jr., von Lilienfeld, O. A. & Tkatchenko, A. Collective many-body van der Waals interactions in molecular systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 14791–14795 (2012).

DiStasio, R. A. Jr., Gobre, V. V. & Tkatchenko, A. Many-body van der Waals interactions in molecules and condensed matter. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 26, 213202 (2014).

Hill, T. L. Steric Effects. I. Van der Waals potential energy curves. J. Chem. Phys. 16, 399 (1948).

Westheimer, F. H. & Mayer, J. E. The theory of the racemization of optically active derivatives of diphenyl. J. Chem. Phys. 14, 733 (1946).

Lilach, Y. & Asscher, M. Steric effect in electron−molecule interaction. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 4358–4361 (2004).

Schreiner, P. et al. Overcoming lability of extremely long alkane carbon–carbon bonds through dispersion forces. Nature 477, 308–311 (2011).

Huber, R. G. et al. Heteroaromatic π-stacking energy landscapes. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 54, 1371–1379 (2014).

Geiger, T. et al. Synthesis and photodimerization of 2- and 2,3-disubstituted anthracenes: influence of steric interactions and London dispersion on diastereoselectivity. J. Org. Chem. 84, 10120–10135 (2019).

Eschmann, C., Song, L. & Schreiner, P. R. London dispersion forces rather than steric hindrance determine the enantioselectivity of the Corey–Bakshi–Shibata reduction. Angew. Chem. 60, 4823–4832 (2021).

Solel, E., Ruth, M. & Schreiner, P. R. London dispersion helps refine steric A-values: dispersion energy donor scales. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 20837–20848 (2021).

Jakobsche, C. E., Choudhary, A., Miller, S. J. & Raines, R. T. n → π* Interaction and n) (π Pauli repulsion are antagonistic for protein stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 6651–6653 (2010).

Takahashi, O., Kohno, Y. & Nishio, M. Relevance of weak hydrogen bonds in the conformation of organic compounds and bioconjugates: evidence from recent experimental data and high-level ab initio MO calculations. Chem. Rev. 110, 6049–6076 (2010).

Carter-Fenk, K. & Herbert, J. M. Electrostatics does not dictate the slip-stacked arrangement of aromatic π–π interactions. Chem. Sci. 11, 6758–6765 (2020).

Zoppi, L. et al. Pauli repulsion versus van der Waals: interaction of indenocorannulene with a Cu(111) surface. J. Phys. Chem. B 122, 871–877 (2018).

Sinnokrot, M. O. & Sherrill, C. D. Substituent effects in π-π interactions: sandwich and T-shaped configurations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 7690–7697 (2004).

Gung, B. W. & Amicangelo, J. C. Substituent effects in C6F6C6H5X stacking interactions. J. Org. Chem. 71, 9261–9270 (2006).

Tsuzuki, S., Uchimaru, T. & Mikami, M. Intermolecular interaction between hexafluorobenzene and benzene: ab initio calculations including CCSD(T) level electron correlation correction. J. Phys. Chem. A 110, 2027–2033 (2006).

Chattopadhyaya, M., Hermann, J., Poltavsky, I. & Tkatchenko, A. Tuning intermolecular interactions with nanostructured environments. Chem. Mater. 29, 2452–2458 (2017).

Chen, J. et al. Noncovalent engineering of carbon nanotube surfaces by rigid, functional conjugated polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 9034–9035 (2002).

Wall, A., Coleman, J. N. & Ferreira, M. S. Physical mechanism for the mechanical reinforcement in nanotube-polymer composite materials. Phys. Rev. B 71, 125421 (2005).

Song, N., Gao, Z. & Li, X. Tailoring nanocomposite interfaces with graphene to achieve high strength and toughness. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba7016 (2020).

Kinloch, I. A., Suhr, J., Lou, J., Young, R. J. & Ajayan, P. M. Composites with carbon nanotubes and graphene: an outlook. Science 362, 547–553 (2018).

Chakravorty, D. K. et al. Energetics of zinc-mediated interactions in the allosteric pathways of metal sensor proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 30–33 (2013).

Thanthiriwatte, K. S., Hohenstein, E. G., Burns, L. A. S. & Herrill, C. D. Assessment of the performance of DFT and DFT-D methods for describing distance dependence of hydrogen-bonded interactions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 7, 88–96 (2011).

Turney, J. M. et al. PSI4: an open-source ab initioelectronic structure program. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2, 556–565 (2012).

Rahmat, M. & Hubert, P. Carbon nanotube-polymer interactions in nanocomposites: a review. Compos. Sci. Technol. 72, 72–84 (2011).

Becke, A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 5648–5652 (1993).

Lee, C., Yang, W. & Parr, R. G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 37, 785–789 (1988).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 09, Revision D.01, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT (2009).

Case, D. A. et al. AMBER 2019 (University of California, 2019).

Wang, J., Wolf, R. M., Caldwell, J. W., Kollman, P. A. & Case, D. A. Development and testing of a general amber force field. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1157–1174 (2004).

Jakalian, A., Bush, B. L., Jack, D. B. & Bayly, C. I. Fast, efficient generation of high-quality atomic charges. AM1-BCC model: I. Method. J. Comput. Chem. 21, 132–146 (2000).

Jakalian, A., Jack, D. B. & Bayly, C. I. Fast, efficient generation of high-quality atomic charges. AM1-BCC model: II. Parameterization and validation. J. Comput. Chem. 23, 1623–1641 (2002).

Phillips, J. C. et al. Scalable molecular dynamics on CPU and GPU architectures with NAMD. J. Chem. Phys. 153, 044130 (2020).

Su, P., Tang, Z. & Wu, W. Generalized Kohn-Sham energy decomposition analysis and its applications. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 10, e1460 (2020).

Tang, Z. et al. XEDA, a fast and multipurpose energy decomposition analysis program. J. Comput. Chem. 42, 2341 (2021).

Arash, B., Wang, Q. & Varadan, V. Mechanical properties of carbon nanotube/polymer composites. Sci. Rep. 4, 6479 (2014).

Fu, H., Xu, S. & Li, Y. Nanohelices from planar polymer self-assembled in carbon nanotubes. Sci. Rep. 6, 30310 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work has been financially supported by China oversea scholarship (no. 201508210267), and DAAD supported Baltic-German University Liaison Office Project no. 2017/8. This research is funded by the Ministry of Education and Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation, Republic of Serbia, Contract numbers: 451-03-65/2024-03/200146, 451-03-66/2024-03/200288, and 451-03-66/2024-03/200168. The high-performance computers were provided by the IT Research Computing Group at Texas A&M University in Qatar, which is founded by Qatar Foundation for Education, Science and Community Development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.Z. and G.R. conceived and planned this project. B.Z. synthesized CNT/polyimide nanocomposites. I.G. and B.Z. carried out the mechanical test and characterized the fracture morphology. S.D.Z., S.S.Z., and B.Z. carried out quantum chemistry and molecular dynamics calculations. B.H. performed the data curation. B.Z. prepared the original draft. G.R., B.Z. and S.D.Z. reviewed and edited the draft. All authors discussed the results, commented on the manuscript, and approved the final version of the paper for submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Uttam K. Ghorai and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, B., Zarić, S.D., Zrilić, S.S. et al. London dispersion forces and steric effects within nanocomposites tune interaction energies and chain conformation. Commun Chem 8, 21 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01414-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01414-4