Abstract

A μSPEed microextraction combined with ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) with UV detection was developed for analysing six veterinary antibiotics (tetracycline, chlortetracycline, oxytetracycline, doxycycline, sulfamethoxazole, and trimethoprim) in environmental samples. To optimise extraction, 12 sorbent cartridges, sample loading cycles, volumes, and pH were assayed. The PS/DVB-RP cartridge, three 250 μL sample loading cycles, and two 50-µL elutions with acidified methanol yielded maximum efficiency. The method was validated with optimised fast chromatographic separation, showing good linearity (R2 > 0.99), precision (RSD < 20%), and recoveries between 46-86%. Detection and quantification limits ranged from 0.30-1.23 μg L−1 and 0.92-3.73 μg L−1, respectively. The optimised μSPEed/UPLC-PDA efficiently analysed environmental water samples, requiring only 6 min extraction, 6 min analysis, and 500 μL sample, surpassing alternative methods in speed, workloads and reproducibility. The cost-effective, commercially available equipment facilitates accessibility for laboratories and adaptability for analysing selected antibiotics in diverse matrices, including food and environmental samples.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent decades, the high consumption of animal food in the human diet has boosted the excessive use of antibiotics to prevent and control diseases, promote growth, and improve the feed conversion efficiency in livestock farming1. The main classes of antibiotics used for these purposes include sulphonamides (mainly sulfamethazine, sulphadimidine, sulfamethoxypyridazine, sulfamethazine, and sulfathiazole), tetracyclines (including oxytetracycline, epi-oxytetracycline, chlortetracycline, doxycycline, among others), penicillins (such as amoxycillin, penicillin G, ampicillin, among others), macrolides (including gamithromycin, neospiramycin, erythromycin among others), quinolones and fluoroquinolones (mainly enrofloxacin, oxolinic acid, and ciprofloxacin), and aminoglycosides (such as neomycin or streptomycin)2. They are used in aquaculture, cattle, eggs, honey, milk, swine, poultry, rabbits, and sheep/goats3,4, and can be administered orally (through water or feed), as injectables, by transfusion, or topically.

The overuse of antibiotics (12 million kilograms worldwide each year1) can leave residues both in their original form and as metabolites or degradation products in foods5. It has been shown that antibiotic residues in food can lead to the development of bacterial resistance, making common infections difficult to treat6,7,8,9. In addition, the continuous ingestion of these residues can alter intestinal flora, causing digestive problems and favouring the growth of pathogenic bacteria. In some cases, prolonged exposure to low levels of antibiotics can trigger allergic reactions or toxicity, affecting organs such as the liver and kidneys10. The presence of antibiotic residues can also interfere with microbiota, weaken the immune system, and increase susceptibility to other diseases6. Specifically, diethylstilbestrol, nitrofurans, and chloramphenicol were banned because of their carcinogenic properties11,12.

To address these problems, it is essential to implement a combination of strategies involving the strict control of antibiotic use in agriculture and animal husbandry, sustainable agricultural practices to reduce reliance on antibiotics, and improved antibiotic residue detection techniques. This will ensure compliance with existing government regulations that can significantly reduce antibiotic contamination in the food chain and protect consumer health. The European Union (EU) has mandated that food undergo scientific assessment in line with Regulation (EC) No. 470/200913. Additionally, in collaboration with the FDA14 and the Codex Alimentarius organisation (which established the Codex Guidelines for the Establishment of a Regulatory Programme for Control of Veterinary Drug Residues in Food)15, the EU has implemented maximum residue concentration limits for pharmacologically active substances utilised in animals. To assess the presence of antibiotic residues in food, it is essential to use an extraction procedure to overcome the complexity of matrices and mitigate interference with target analyte quantification. Solid–liquid extraction (SLE), Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE), and liquid–liquid extraction (LLE) techniques have historically been the most widely used techniques, as reviewed by Barros et al.2. Combined with advanced analytical methods such as liquid chromatography (LC), extraction techniques such as SLE, d-SPE, SPE, and LLE have improved the detection and quantification of antibiotics, thus ensuring greater food safety and compliance with government regulations2,16,17,18,19,20. However, the current challenge is the development of miniaturised extraction procedures using minimal amounts of solvents, reagents, and samples to fulfil the goals of Sustainable Green Chemistry21. To this end, a μSPEed/UPLC-UV methodology was developed and validated for the simultaneous analysis of six veterinary antibiotics in environmental water: tetracycline (TC), chlortetracycline (CTC), oxytetracycline (OTC), doxycycline (DC), sulfamethoxazole (SMX), and trimethoprim (TMP). Overall, the developed methodology exhibits exceptional efficiency, with a total processing time of only 12 min and a sample volume of 500 μL, outperforming other methods in terms of speed and sample use while maintaining robust analytical performance and environmental friendliness. Moreover, this semi-automated approach reduces the workload of analysts and improves their reproducibility. The method’s adaptability and use of affordable, readily available equipment (μSPEed sorbent and DigiVol) make it easily accessible to other laboratories and suitable for analysing selected antibiotics in various matrices, including food and environmental samples.

Materials and methods

Reagents and materials

Analytical standards (≥99%) for tetracycline (TC), chlortetracycline (CTC), oxytetracycline (OTC), doxycycline (DC), sulfamethoxazole (SMX), and trimethoprim (TMP) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Louis, MO, USA. HPLC-grade acetonitrile (ACN), methanol (MeOH), and sodium hydroxide (NaOH) were obtained from Fischer Scientific (Loughborough, UK). Formic acid (FA), chloride acid (HCl, 37%) were purchased from Panreac Química (Barcelona, Spain). Purified water used in the experiments was produced from a Milli-Q ultrapure water purification system (Millipore, Milford, MA, USA). All reagents were of the highest available analytical quality.

The Digivol® syringe and μSPEed® cartridges (butyl silica (C4), octyl silica (C8), octadecyl silica (C18-RPS), octadecyl silica hydrophilic ODS (C18-ODS), unmodified silica (Sil), aminopropyl silane sorbent (WAX), polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), porous PS/DVB normal phase (PS/DVB), porous PS/DVB reversed phase (PS/DVB-RP), PS/DVB anionic exchange (PS/DVB-SAX), PS/DVB cationic exchange (PS/DVB-SCX), and porous graphitic carbon (μCARB)) were supplied by EPREP (Mulgrave, Victoria, Australia).

Standard solutions were prepared at 1 mg mL−1 using ACN as the solvent (for CTC, MeOH was used). Lower concentrations were obtained by diluting standard solutions with an appropriate amount of ACN.

Instrumentation

Chromatographic analysis was performed using a Waters Ultra-High Pressure Liquid Chromatographic Acquity system (Acquity UPLC H-Class, Milford, MA, USA) equipped with a column heater, an Acquity sample manager (SM), a degassing system, a Water Acquity quaternary solvent manager (QSM), and a photodiode array (PDA) detector. The analytical column was a Acquity UPLC BEH C18 (130 Å, 2.1 mm × 50 mm, 1.7 μm, Waters, USA) operated at 30 °C with gradient elution at a flow rate of 0.40 mL min–1; the mobile phase for the chromatographic separation was a mixture of A (0.1% FA) and B (ACN). Separation was performed with the following gradient conditions: 95% A, 80% A at 3 min, 75% A at 3.5 min, 70% A at 4 min, 65% A at 4.5 min, and 60% A at 6 min. The system was re-equilibrated for 2 min with 95% A between injections. PDA detection was set at 280 nm during the analysis.

μSPEed procedure

Extraction was performed using a DigiVol® X-change® electronic automatic syringe (250 μL needle). The PS/DVB-RP cartridge was conditioned with 250 µL of MeOH (750 μL min−1 flow rate), equilibrated with 250 µL of H2O (750 μL min−1 flow rate), and 500 µL of the sample was loaded three times (500 μL min−1 flow rate). The elution step was performed with two cycles of 50 µL acidic MeOH (500 μL min−1 flow rate). The optimised extraction procedure required 6 min for each sample. Each cartridge was used for over 50 extractions without affecting its activity. The experimental procedure is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Results and discussion

Semi-automated solid-phase microextraction has been used to extract and purify four tetracyclines, SMX, and TMP, in aqueous samples. The selected antibiotics have different physicochemical properties and polarities. For this reason, full optimisation of the extraction and chromatographic conditions using a univariate protocol was performed. The starting conditions for the conditioning, equilibration, sample loading, and elution steps of µSPEed extraction were chosen based on previous experiments22,23.

Optimization of cartridge used for extraction

Cartridge selection is crucial for the μSPEed method. Different cartridges provide distinct retention mechanisms that are tailored to various target analytes22. Twelve cartridges (C4, C8, C18 RPS, C18 ODS, Sil, WAX, PFAS, PS/DVB, PS DVB, PS/DVB, PS DVB RP, PS/DVB, PS DVB SAX, PS DVB SCX, and μCARB) were tested for the extraction of the selected analytes. To assay the PS DVB SAX and PS DVB SCX cartridges, the sample pH was adjusted to 4, 7, and 9. This was essential to ensure that the sorbents were assayed under the best conditions. Moreover, the effect of pH on the extraction of antibiotics, including those used in this work, has been widely reported in the literature24,25,26. According to Mirzaei et al.24 and Zhou et al.26, the pH of water samples plays a crucial role in the extraction recovery of antibiotics, affecting both the stability of the antibiotics and their interactions with the extraction medium. To optimise the recovery, the sample pH is often adjusted using hydrochloric acid before extraction24. The recovery values for each cartridge are shown in Fig. 2. Overall, the PS DVB cartridges (normal phase and reverse phase, RP) were found to be the most suitable for extracting the selected antibiotics, outperforming the other sorbents assayed, including the ionic exchange sorbents mentioned above. PS DVB RP was selected for subsequent experiments because it is the most versatile PS DVB sorbent.

Sample conditions optimization: volume, loading cycles and pH

To improve the recovery of the selected analytes during extraction, further optimisation of the process was performed. In the third step of μSPEed extraction (see Fig. 1), the effects of the amount of sample, number of extraction cycles, and pH of the elution solvent on the recovery of the target analytes were assayed. While the sample volume and number of extraction cycles affect the amount of the selected compounds available in the solution to be retained in the sorbent during the extraction, the pH of the elution solvent was also assayed considering the dependence of the extraction efficiency on the pH mentioned above24,25,26. Accordingly, 3–5 sample loading cycles followed by MeOH or acidified MeOH elution were performed. The highest recoveries for all selected antibiotics (46.9–75.3%) were obtained for a 3 × 250 μL sample cycle loading at a flow rate of 500 μL min−1 using acidified MeOH as the elution solvent (Fig. 3a). The effect of the sample volume was further investigated by analysing the recovery of the target antibiotics at sample volumes of 500 and 800 μL. Optimum recoveries (45.9–85.9%) were obtained for a sample volume of 500 μL at a flow rate of 500 μL min−1 (Fig. 3b). Up to this point of extraction optimisation, the recoveries of some of the selected antibiotics, namely CTC and DC, were very low (not reaching 50%). This led us to thoroughly assess the influence of pH on the extraction of target analytes. We consider that tetracyclines are amphoteric compounds, with pKa values of 3.33, 7.55, 9.33 for CTC; 3.02, 7.97, 9.15 DC, 3.22, 7.46, 8.94 for OTC; and 3.32, 7.78, 9.58 for TC27,28; SMX is an acidic compound with a low pKa of 1.6 and 5.729, while TMP is an alkaline compound with a pKa of 7.1230. Therefore, it was necessary to select suitable pH conditions to ensure that the selected compounds were in the protonated/non-protonated forms. Accordingly, we considered a pH below all pKa values (pH 2.5, and not pH 4.0, as previously assayed), pH 7.0 as a neutral condition, and pH 8.5, and not 9.0 (basic conditions). The best performance (recoveries in the range 46.9–75.3%) was obtained with samples at pH 7 and elution with acidified MeOH (5% FA, Fig. 3c).

Selection of elution solvent

In the last step (Fig. 1), the effect of the solvent on the elution of target analytes was assayed and fine-tuned. Tests were performed using MeOH, ACN, and acidic MeOH (with 5% FA and 1% FA). Other conditions such as acidic ACN were not assayed to preserve the integrity of the spare parts of the DigiVol® syringe. After evaluation, acidic MeOH with 5% FA was found to allow for a higher extraction of the target antibiotics, and this condition was selected for further analysis (Fig. 4). These results agree with other reports referring to MeOH as the most suitable solvent for desorbing compounds from SPE26. The volume of solvent required to elute all the analytes was also examined. Accordingly, 50, 100, and 150 μL of acidic MeOH were assayed. While increasing the elution volume from 50 to 100 µL yielded better results, there was no significant difference in the recoveries between the 100 μL and 150 μL elution volumes. We verified that the extraction of the target analytes was further enhanced with two consecutive 50 µL elution steps in comparison with a single 100 μL elution step (data not shown). All discarded solutions in the different steps of the µSPEed protocol were collected and analysed throughout the optimisation process to evaluate the effect of each condition on the extraction efficiency. This was essential to verify the efficiency of the µSPEed sorbent in retaining the target analytes during the sample loading step and the ability of the elution solvent to elute the analytes from the sorbent, thus avoiding carry-over effects. Specifically, in this case, a third consecutive elution step performed during the optimisation revealed that no antibiotics were retained in the sorbent. Overall, the best conditions obtained included 500 μL of the sample processed in a 3 × 250 µL sample loading cycle, followed by two consecutive elution steps with 50 μL of acidified MeOH (5% FA). The flow rate was maintained at 500 μL min−1 during the entire procedure.

μSPEed/UPLC-PDA validation

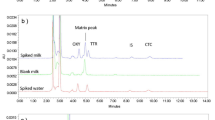

To allow appropriate validation of the methodology, the chromatographic separation of the target analytes was optimised using a gradient of acidified water (0.1% FA) and ACN (as described in “Materials and Methods”). This resulted in a fast chromatographic separation of only six min that, to the best of our knowledge, has not been previously reported for the selected antibiotics in this time range (Fig. 5).

The analytical performance of the developed methodology was evaluated based on relevant parameters, such as the linear range, recovery, limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ), and precision (intra-day and inter-day). Calculations were performed using a calibration curve (plot of the peak area to the analyte concentration, seven concentration points, n = 3). The method was found to be linear in the range 0.92–10 μg L–1, r2 > 0.9914. The LOD values were calculated based on the equation LOD = 3.3(Sy/S), where Sy is the standard deviation of the response and S is the slope of the calibration curve, obtaining values in the range 0.30–1.23 μg L–1 (n = 6). The LOQ values were calculated based on the equation LOQ = 10(Sy/S), obtaining values in the range 0.92–3.73 μg L–1 (n = 6). The selectivity of the method was also verified, because no impurities were observed in the retention times (RTs) of the target analytes (Fig. 5). The intra- and inter-day precisions were expressed as the relative standard deviation (RSD) of the analyte content and were <20%. The recoveries (Rec, %) were calculated based on the following equation: Rec % = (amount of compound recovered/amount of compound originally present) ×100, and varied from 45.9 to –85.9%. The recoveries for CTC and DC (45.9% and 47.2%, respectively) were particularly low, but this was not totally unexpected. The optimized conditions used in this work, namely the neutral sample pH, do not favour the extraction of some tetracyclines, as already reported in the literature25,31,32.

Detailed data are shown in Table 1.

Analysis of real samples

The μSPEed/UPLC-PDA methodology was applied to analyse water samples from Levadas, which are used by local farmers on Madeira Island to irrigate cultivated lands. Three samples were collected from different water channels, filtered, and subjected to μSPEed/UPLC-PDA analysis in triplicates. Replica samples were fortified with a standard mixture containing the target antibiotics at ML concentrations (Table 1) and analysed. No interference was detected at the retention times of the target antibiotics, suggesting that matrix interference can be disregarded. Moreover, none of the selected antibiotics were found in the analysed samples.

Comparison of μSPEed/UPLC-PDA with other extraction methods and greenness assessment

To obtain a clear insight into how the μSPEed/UPLC-PDA proposed here is compared with other equivalent methodologies, we performed a survey of methodologies previously reported using microextraction followed by chromatographic analysis with UV detection for the determination of tetracyclines, SMX, and TMP (Table 2). Many other methodologies employing MS analysis33,34,35 were not considered because although this configuration has the potential to allow better analytical performance, it is far more expensive and labourious. Similarly, promising approaches using custom-made sorbents or solvents and layouts that are not yet commercially available36,37,38,39 were also not discussed in this study. Table 2 summarises the main analytical features of the methods reported from 2018 to 2024. As can be easily observed, μSPEed/UPLC-PDA offers a faster extraction time (6 min per sample), requires much less sample (500 µL), and can simultaneously analyse six frequently used veterinary antibiotics, while delivering comparable analytical performance. In addition to these benefits, the system requires minimal laboratory effort beyond that of the semi-automatic syringe. Furthermore, both the µSPEed sorbent and DigiVol® are commercially available and highly cost-effective, and the electronic pipette can be utilised as a standard pipette, with the significant advantage of being easily programmable for automated tasks. This feature helps reduce the experimental errors typically associated with human operators performing repetitive actions.

The experimental setup of μSPEed/UPLC-PDA proposed herein can be readily modified for various matrices beyond environmental water samples, provided that they can be converted into a liquid state with minimal viscosity and complexity, thereby avoiding blockage of the sorbent chamber. This limitation can be overcome by the technique’s high preconcentration capability, which depends on the specific analytes and sample type under investigation.

To compare the proposed μSPEed/UPLC-PDA analysis with the other methodologies listed in Table 2, a detailed greenness assessment was performed. This includes the Analytical Eco-Scale assessment40, Analytical GREEnness (AGREE)41 tool, and BAGI tool42. The eco-scale measures the environmental impact by subtracting points from 100, with higher scores being greener. The μSPEed/UPLC-PDA method scored 76 points, indicating excellent green analysis, which is comparable to the reports presented in Table 2, ranging to from 72 to 79 points. The AGREE tool is based on 12 green chemistry principles and gave the μSPEed approach a score of 0.64, which is one of the highest of the 0.49–0.65 range obtained. The methodologies listed in Table 2 were further considered within the scope of practicality and assessed using the BAGI tool42. In simple terms, this tool measures, for instance, how easy it is to implement a given methodology and how many samples can be processed per unit time. The μSPEed/UPLC-PDA score was 67.5, one of the highest scores achieved in our comparison. Complementary analysis was performed using the green analytical procedure index (ComplexGAPI)43. This tool provides pictograms showing areas for improvement in terms of sampling, transport, solvents, and waste treatment. The data obtained, which are available as supplementary material, once again point to the greener profile of the μSPEed/UPLC-PDA analysis. Overall, the cumulative assessment using the most important green assessment tools available, namely the analytical eco-scale40, AGREE41 and GAPI tools43 and BAGI index42, clearly shows the higher greenness character of the μSPEed/UPLC-PDA analysis proposed here in comparison with other alternatives reported in the literature using similar methodologies.

Conclusion

In this study, a semi-automated solid-phase microextraction technique was validated for the quantification of six antibiotics (tetracycline, chlortetracycline, oxytetracycline, doxycycline, sulfamethoxazole, and trimethoprim) in aqueous samples with good analytical performance. The developed methodology exhibits exceptional efficiency, with a total processing time of just 12 min and a sample volume of 500 μL, outperforming other methods in terms of speed and sample use while maintaining robust analytical performance and environmental friendliness. Moreover, this semi-automated approach reduces the workload for analysts and improves reproducibility. The method’s adaptability and use of affordable, readily available equipment (μSPEed sorbent and DigiVol) make it easily accessible to other laboratories and suitable for analysing the selected antibiotics in various matrices, including food and environmental samples.

Data availability

The detailed data produced in this research can be provided upon request.

References

Adegbeye, M. J. et al. Comprehensive insights into antibiotic residues in livestock products: Distribution, factors, challenges, opportunities, and implications for food safety and public health. Food Control 163 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2024.110545 (2024).

Barros, S. C., Silva, A. S. & Torres, D. Multiresidues multiclass analytical methods for determination of antibiotics in animal origin food: A critical analysis. Antibiotics-Basel 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12020202 (2023).

Du, L. & Liu, W. Occurrence, fate, and ecotoxicity of antibiotics in agro-ecosystems. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 32, 309–327 (2012).

Leibovici, L. et al. Addressing resistance to antibiotics in systematic reviews of antibiotic interventions. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71, 2367–2369 (2016).

European Food Safety Authority. Report for 2011 on the results from the monitoring of veterinary medicinal product residues and other substances in live animals and animal products. EFSA Supporting Publ. 10, 363E (2013).

Arsene, M. M. J. et al. The public health issue of antibiotic residues in food and feed: Causes, consequences, and potential solutions. Vet. World 15, 662–671 (2022).

Landers, T. F., Cohen, B., Wittum, T. E. & Larson, E. L. A review of antibiotic use in food animals: Perspective, policy, and potential. Public Health Rep. 127, 4–22 (2012).

Elafify, M. et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in milk and dairy products in Egypt. J. Environ. Sci. Health B 55, 265–272 (2020).

Habib, I. et al. Genomic profiling of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli from Pets in the United Arab Emirates: Unveiling colistin resistance mediated by mcr-1.1 and its probable transmission from chicken meat - A One Health perspective. J. Infect. Public Health 16, 163–171 (2023).

Bacanli, M. & Basaran, N. Importance of antibiotic residues in animal food. Food Chem. Toxicol. 125, 462–466 (2019).

Dolores Marazuela, M. in Liquid Chromatography: Applications, Vol 2, 2nd Edition Handbooks in Separation Science (eds S. Fanali, P. R. Haddad, C. F. Poole, & M. L. Riekkola) 539-570 (2017).

Pratiwi, R., Ramadhanti, S. P., Amatulloh, A., Megantara, S. & Subra, L. Recent Advances in the Determination of Veterinary Drug Residues in Food. Foods 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12183422 (2023).

Official Journal of the European Union. Commission Regulation (EU) No 37/2010 of 22 December 2009 on pharmacologically active substances and their classification regarding maximum residue limits in foodstuffs of animal origin (Text with EEA relevance), https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32010R0037

Food and Drug Administration. (FDA). The Code of Federal Regulations, U.S.F. & D.A. Food and drugs.

Food Safety and Inspection Service, USDA. Codex Alimentarius: Meeting of the Codex Committee on Residues of Veterinary Drugs in Food.

Kang, J. et al. Multiresidue screening of veterinary drugs in meat, milk, egg, and fish using liquid chromatography coupled with ion trap time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 182, 635–652 (2017).

Zheng, W. et al. Development and validation of a solid-phase extraction method coupled with LC-MS/MS for the simultaneous determination of 16 antibiotic residues in duck meat. Biomed. Chromatogr. 33 https://doi.org/10.1002/bmc.4501 (2019).

Castilla-Fernandez, D., Moreno-Gonzalez, D., Beneito-Cambra, M. & Molina-Diaz, A. Critical assessment of two sample treatment methods for multiresidue determination of veterinary drugs in milk by UHPLC-MS/MS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 411, 1433–1442 (2019).

Li, X. et al. Untargeted multi-residue method for the simultaneous determination of 141 veterinary drugs and their metabolites in pork by high-performance liquid chromatography time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 1634 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2020.461671 (2020).

Zhang, C., Zeng, J., Xiong, W. & Zeng, Z. Rapid determination of amoxicillin in porcine tissues by UPLC-MS/MS with internal standard. J. Food Composition Anal. 92 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2020.103578 (2020).

Berenguer, C. V. et al. Exploring the potential of microextraction in the survey of food fruits and vegetable safety. Appl. Sci.-Basel 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/app13127117 (2023).

González-Gómez, L., Pereira, J. A. M., Morante-Zarcero, S., Câmara, J. S. & Sierra, I. Green extraction approach based on μSPEed® followed by HPLC-MS/MS for the determination of atropine and scopolamine in tea and herbal tea infusions. Food Chem. 394, 133512 (2022).

García-Cansino, L., García, M., Marina, M. L., Câmara, J. S. & Pereira, J. A. M. Simultaneous microextraction of pesticides from wastewater using optimized μSPEed and μQuEChERS techniques for food contamination analysis. Heliyon 9, e16742 (2023).

Mirzaei, R. et al. An optimized SPE-LC-MS/MS method for antibiotics residue analysis in ground, surface and treated water samples by response surface methodology- central composite design. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 15, 21 (2017).

Chabilan, A., Landwehr, N., Horn, H. & Borowska, E. Impact of log(Kow) value on the extraction of antibiotics from river sediments with pressurized liquid extraction. Water 14, 2534 (2022).

Zhou, J. L., Maskaoui, K. & Lufadeju, A. Optimization of antibiotic analysis in water by solid-phase extraction and high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta 731, 32–39 (2012).

Kortesmäki, E. et al. Occurrence of antibiotics in influent and effluent from 3 major wastewater‐treatment plants in Finland. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 39, 1774–1789 (2020).

Harrower, J. et al. Chemical fate and partitioning behavior of antibiotics in the aquatic environment—A Review. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 40, 3275–3298 (2021).

Bizi, M. Sulfamethoxazole removal from drinking water by activated carbon: Kinetics and diffusion process. Molecules 25, 4656 (2020).

Guneysel, O., Onur, O., Erdede, M. & Denizbasi, A. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole resistance in urinary tract infections. J. Emerg. Med. 36, 338–341 (2009).

Tang, H. Z. et al. Development and application of magnetic solid phase extraction in tandem with liquid-liquid extraction method for determination of four tetracyclines by HPLC with UV detection. J. Food Sci. Technol. 57, 2884–2893 (2020).

Poindexter, C., Yarberry, A., Rice, C. & Lansing, S. Quantifying antibiotic distribution in solid and liquid fractions of manure using a two-step, multi-residue antibiotic extraction. Antibiotics (Basel) 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11121735 (2022).

Shahriman, M. S., Mohamad, S., Mohamad Zain, N. N. & Raoov, M. Poly-(MMA-IL) filter paper: A new class of paper-based analytical device for thin-film microextraction of multi-class antibiotics in environmental water samples using LC-MS/MS analysis. Talanta 254, 124188 (2023).

Wang, R. et al. Selective extraction and enhanced-sensitivity detection of fluoroquinolones in swine body fluids by liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry: Application in long-term monitoring in livestock. Food Chem. 341, 128269 (2021).

Mondal, S. et al. Solid-phase microextraction of antibiotics from fish muscle by using MIL-101(Cr)NH(2)-polyacrylonitrile fiber and their identification by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta 1047, 62–70 (2019).

Alipanahpour Dil, E., Ghaedi, M., Mehrabi, F. & Tayebi, L. Highly selective magnetic dual template molecularly imprinted polymer for simultaneous enrichment of sulfadiazine and sulfathiazole from milk samples based on syringe-to-syringe magnetic solid-phase microextraction. Talanta 232, 122449 (2021).

Gissawong, N., Boonchiangma, S., Mukdasai, S. & Srijaranai, S. Vesicular supramolecular solvent-based microextraction followed by high performance liquid chromatographic analysis of tetracyclines. Talanta 200, 203–211 (2019).

Pochivalov, A. et al. Liquid-liquid microextraction with hydrophobic deep eutectic solvent followed by magnetic phase separation for preconcentration of antibiotics. Talanta 252, 123868 (2023).

Yıldırım, S., Cocovi-Solberg, D. J., Uslu, B., Solich, P. & Horstkotte, B. Lab-In-Syringe automation of deep eutectic solvent-based direct immersion single drop microextraction coupled online to high-performance liquid chromatography for the determination of fluoroquinolones. Talanta 246, 123476 (2022).

Gałuszka, A., Migaszewski, Z. M., Konieczka, P. & Namieśnik, J. Analytical Eco-Scale for assessing the greenness of analytical procedures. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 37, 61–72 (2012).

Pena-Pereira, F., Wojnowski, W. & Tobiszewski, M. AGREE—Analytical GREEnness metric approach and software. Anal. Chem. 92, 10076–10082 (2020).

Manousi, N., Wojnowski, W., Plotka-Wasylka, J. & Samanidou, V. Blue applicability grade index (BAGI) and software: a new tool for the evaluation of method practicality. Green. Chem. 25, 7598–7604 (2023).

Płotka-Wasylka, J. & Wojnowski, W. Complementary green analytical procedure index (ComplexGAPI) and software. Green. Chem. 23, 8657–8665 (2021).

Di, X., Zhao, X. & Guo, X. Hydrophobic deep eutectic solvent as a green extractant for high-performance liquid chromatographic determination of tetracyclines in water samples. J. Sep. Sci. 43, 3129–3135 (2020).

Wang, Y., Li, J., Ji, L. & Chen, L. Simultaneous determination of sulfonamides antibiotics in environmental water and seafood samples using ultrasonic-assisted dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction coupled with high performance liquid chromatography. Molecules 27 https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27072160 (2022).

Al-Afy, N., Sereshti, H., Hijazi, A. & Rashidi Nodeh, H. Determination of three tetracyclines in bovine milk using magnetic solid phase extraction in tandem with dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction coupled with HPLC. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life. Sci. 1092, 480–488 (2018).

Lian, L., Lv, J., Wang, X. & Lou, D. Magnetic solid-phase extraction of tetracyclines using ferrous oxide coated magnetic silica microspheres from water samples. J. Chromatogr. A 1534, 1–9 (2018).

Yang, Y. et al. Carboxyl Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticle-based SPE and HPLC method for the determination of six tetracyclines in water. Anal. BioAnal. Chem. 411, 507–515 (2019).

Sereshti, H., Karami, F., Nouri, N. & Farahani, A. Electrochemically controlled solid phase microextraction based on a conductive polyaniline‐graphene oxide nanocomposite for extraction of tetracyclines in milk and water. J. Sci. Food Agric. 101, 2304–2311 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia [grants number UIDB/00674/2020 (CQM Base Fund—DOI: 10.54499/UIDB/00674/2020) and UIDP/00674/2020 (Programmatic Fund—DOI 10.54499/UIDP/00674/2020)] by EDRF-Interreg MAC 2014–2020 Cooperacion territorial through AD4MAC project (MAC2/1.1b/350), ARDITI—Agência Regional para o Desenvolvimento da Investigação Tecnologia e Inovação [Project M1420-01-0145-FEDER-000005 (Madeira 14–20 Programme)], Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (Project PID2022-140512NB-I00), the University of Alcalá [FPI predoctoral contract and mobility grant to stay at Madeira University given to LGC], and Polish Ministry of Education and Science [grants: 0713/SBAD/0990, 0713/SBAD/0991, 0911/SBAD/2404].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.A., L.G.-C.: Investigation; Methodology; Data curation; Formal analysis; Validation; Writing—original draft; J.deS.C., D.G.-K., J.Z., M.Á.G., M.L.M.: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Writing—review & editing; J.deS.C.: Funding acquisition; J.A.M.P. Investigation; Methodology; Formal analysis; Supervision; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Antos, J., García-Cansino, L., García, M.Á. et al. Improved methodology to survey veterinary antibiotics in environmental samples using µSPEed microextraction followed by ultraperformance liquid chromatography. Commun Chem 8, 68 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01454-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01454-w