Abstract

The preparation of Zintl phases with pronounced spin-orbit coupling has received substantial scientific interest because of their distinctive electronic properties. In the context of superconductivity and topological phenomena related to band inversion, intermetallic compounds of bismuth have come into focus recently. While bismuth forms a rich variety of Zintl phases with the heavier alkaline-earth metals, there are significantly fewer magnesium compounds. Here we show that high-temperature high-pressure synthesis opens a convenient route for the preparation of Mg5Bi3Hx already at moderate conditions. The compound (space group Pnma, a = 11.5399(3) Å, b = 8.9503(2) Å and c = 7.8770(2) Å) adopts a Ca5Sb3F crystal structure. The minute amounts of hydrogen could only be detected by thermal decomposition of the compound in combination with mass spectroscopy of the gas phase. Direct space analysis of the chemical bonding allowed for allocating the hydrogen position at a partially occupied interstitial site and reveals strongly polar Mg-Bi and Mg-H bonds in accordance with the Zintl concept. Calculated band structures exhibit substantial electronic reorganization upon hydrogen insertion. The combination of advanced analytical tools in concert with modern quantum chemical techniques provides an efficient approach to allocate trace amounts of interstitial atoms stabilizing intermetallic phases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The renewed interest in intermetallic compounds of bismuth is driven by the frequent occurrence of valuable physical properties like superconductivity1,2,3 and the recurrent appearance of topological phenomena, which originate from band inversion resulting from the enormous spin-orbit coupling in the heavy element4,5,6. Intermetallic compounds of bismuth already attracted the attention of Zintl7,8 who recognized that the salt-like properties of Mg3Bi2 may be described by the electron-precise balance [Mg+2]3[Bi−3]2. Despite the later discovery of numerous new bismuth phases of other alkaline-earth metals9, Mg3Bi2 remained the only compound in the system Mg-Bi. Its ambient-temperature modification transforms into a disordered high-temperature form at 959 K10.

In recent studies, the formation of new bismuth compounds has been extensively investigated at extreme conditions. The discovery of several new binary phases with transition-metals11,12,13,14,15,16,17 suggests that application of high pressure is a suitable means to manufacture unacquainted products. The present study in the system magnesium—bismuth at high-pressure high-temperature conditions discloses a compound with composition Mg5Bi3Hx containing only approximately 0.03 wt% hydrogen. Diligent investigation of the reaction conditions verify that the formation of the compound requires the presence of those infinitesimal amounts of hydrogen. Consequently, the atomic arrangement is assigned to the Ca5Sb3F type18,19. As a result of the present study, we report the discovery of the ternary phase Mg5Bi3Hx. A detailed analysis of the chemical bonding sheds light on the atomic charges as well as on the position of the interstitial hydrogen and its role for the stability of the phase. The band structure changes upon hydrogen insertion involve sophisticated charge adjustments within the polar intermetallic compound.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterization

The maximum yield of the new compound is achieved by treatment of a mixture Bi62.5Mg37.5 at 4 GPa combined with heating for 30 min at 1073(50) K followed by annealing for 3 h at 773(30) K before quenching under load. Powder X-ray diffraction patterns of the product show reflections of the new compound plus a second set, which is compatible with the well-known Mg3Bi2-type crystal structure.

The phases in the product mixture reveal insignificant (Supplementary Fig. 1) X-ray backscattering contrast with an average composition amounting to Mg62.8(5)Bi37.2 of metallographic samples (Supplementary Fig. 2). We note here that the accompanying side phase, which is commonly labelled as Mg3Bi2, exhibits a broad homogeneity range from Mg60Bi40 up to Mg64Bi36 at ambient pressure and 773 K20,21,22.

For further chemical analysis, the mass loss of an as-cast mixture from the high-pressure synthesis is investigated by ramping the temperature and performing mass spectroscopy of the gas phase (Fig. 1). The measurements indicate that 23.9 mg of sample contain 0.0046 mg of hydrogen, which is released at temperatures above 613 K (onset). Using the phase amount of Mg5Bi3Hx as determined by X-ray powder refinements (approximately 80 mass%) and the determined charge, the hydrogen content of the product mixture (0.019 mass%) is estimated by a calibration function (Supplementary Fig. 3). The composition of the new phase amounts to Mg5Bi3Hx with x ≈ 0.2. Chemical analysis of the elements used for synthesis clearly identified significant amounts of hydrogen in the magnesium and bismuth powders used for synthesis (Supplementary Fig. 4). Using carefully dehydrogenated magnesium and bismuth fail to yield the new ternary phase pointing at an essential role of hydrogen for stabilization of the new compound.

Upon heating at ambient pressure, the as-cast high-pressure product exhibits an exothermal, monotropic effect at approximately 516(10) K in differential scanning calorimetry measurements (Fig. 2). After the thermal treatment, the reflections of the new phase Mg5Bi3Hx have disappeared and powder X-ray diffraction data essentially indicate a transformation of the hydride into Mg3Bi2 (Supplementary Fig. 5). These findings indicate that the compound Mg5Bi3Hx is a metastable high-pressure phase.

The phase mixture contains Mg3Bi2 and the new phase Mg5Bi3Hx. The exothermal signal in the inset is attributed to the decomposition of Mg5Bi3Hx into Mg3Bi2 and Mg(Bi). All effects occurring at higher temperatures are endothermal upon heating in accordance with the phase diagram refs. 20,21,22. The signal at 756 K is assigned to the melting of Mg(Bi), the one at 822 K is attributed to the melting of the eutectic mixture. At 959 K the transformation of the low-temperature modification of Mg3Bi2 into the high-temperature form is indicated, and 990 K corresponds to the liquidus.

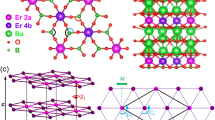

Structure solution and refinement of the high-pressure product are done using powder X-ray diffraction data. Indexing of the reflections of the new phase suggests orthorhombic symmetry with systematic extinctions being compatible with the space groups Pnma and P2na. The intensity pattern points at a crystal structure which is related to the β-Yb5Sb3-type (Supplementary Fig. 6).

A two-phase refinement using full diffraction profiles confirms the presence of Mg3Bi2 and substantiates for Mg5Bi3Hx a structure model in the centrosymmetric space group Pnma (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 7). Admittedly, the position of hydrogen remains undetermined because of its weak scattering contribution in comparison to that of bismuth. Refinements with and without H atoms yield essentially the same results and R-values (compare Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 6). Thus, the position of hydrogen is determined by quantum chemical optimization of the crystal structure (see subsection Determination of the Hydrogen Position) and included. Refinements of the Ca5Sb3F-type model19 converge to RP = 0.026 and RI = 0.037 (Tables 1 and 2; selected interatomic distances Mg−Bi and Mg−H are listed in Table S1). The resulting composition with respect to the metal atoms is in full accordance with the findings of the wavelength dispersive X-ray spectroscopy measurements. At the same p,T conditions, attempts to synthesize the new phase with a substantially higher hydrogen content (Mg5Bi3H1) by reaction of MgH2 + 9 Mg + 6 Bi yield a different product (see Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9).

Chemical bonding analysis

In order to investigate the role of hydrogen in the high-pressure phase, we performed chemical bonding analysis for the idealized hydrogen-free case with composition Mg5Bi3 as well as for the scenario with interstitial hydrogen according to a hypothetical composition Mg5Bi3Hx (x = 1). The formal charge of a compound Mg5Bi3 may be rationalized as [Mg+2]5[Bi−3]3 × 1e− pointing at an electron-excess compound, in which the cations offer more electrons than required in the anionic part23. Such a formal surplus of electrons is compatible with several different electronic scenarios. The excess electrons may fill antibonding states above the pseudo gap in the electronic density of states (DOS). Materials with these DOS features are interpreted as metallic Zintl phases24,25,26,27.

Another conceptual situation appears when the cationic component forms homoatomic bonds, e.g., in gallium mono-selenide comprising the gallium di-cation [Ga2]4+[(0b)Se2−]2. Alternatively, excess electrons may be localized in a lone pair of the cation, like in indium monobromide: [(lp)In+] [(0b)Br−]. And finally, a recent study on LuGe evidences that excess electrons Lu3+[(2b)Ge2−] × 1e− are used for multi-atomic bonding and the formation of vertices-condensed polycations Lu428.

To understand the situation of such an electron-excess model of the Mg5Bi3-type, the electronic density of states (DOS) is analyzed (Fig. 4, top). Below the Fermi level, it consists of two clearly separated regions. The first one (− 12 eV < E < − 10 eV) is mostly formed by s states of Bi with small contribution of Mg(s) and Mg(p). The main region (− 5.5 eV < E < EF) contains primarily the p states of bismuth mixed with s and p states of magnesium. A striking aspect is the position of the Fermi level slightly above the lowest section in the pseudo gap. Integration of the number of states between the pseudo-gap minimum and the Fermi level yields 3.87 electrons per unit cell, i.e., approximately one electron per formula unit, well in agreement with the electron count given above. Consequently, a compound Mg5Bi3 would bear a striking similarity to LuGe28.

That situation is fundamentally changed upon insertion of hydrogen. The magnesium s contributions located at the Fermi level in Mg5Bi3 are shifted to lower energies and form the separated DOS region together with mainly H(s) states in Mg5Bi3H (−7 eV < E < − 6 eV). As a result, a gap of approximately 0.2 eV appears at EF (Fig. 4, bottom) in line with the electron precise balance [Mg2+]5[Bi3−]3[H−].

Information about the bonding interactions are obtained from topological analysis of the calculated electron density (ED). The zero-flux surfaces in the gradient vector field of the ED form the boundaries of basins which represent atomic regions (Fig. 5, top).

While the bismuth charges of −2.02 and −2.10 for both crystallographic positions in Mg5Bi3 are quite similar, the spread of the magnesium atoms from +1.15 to +1.33 is slightly larger. The insertion of hydrogen in Mg5Bi3H (Fig. 5, bottom) mainly affects the calculated charge of only two magnesium atoms (Mg2 and Mg4) while the other values exhibit only minor changes. However, the changes effectively reduce the range to values between +1.35 and +1.42 in the hydride. The general increase is in line with the role of hydrogen as an additional electron acceptor with a calculated negative charge of −0.97.

The calculated charge transfers, in both Mg5Bi3 and Mg5Bi3H, are significantly lower than the formal oxidation states of +2 and −3 assigned to Mg and Bi, respectively. Nevertheless, the obtained effective charges for the Mg species comply with the general tendency of decreasing charge with increasing content of the cationic component. Similar trends are observed for Al in Al-Pt compounds29, for yttrium in Y-Ga30 and for Be in Be-Rh compounds31.

Further insight into the atomic interactions is obtained by analysis of the spatial distribution of the Electron-Localizability Indicator (ELI), in its ELI-D representation, combined with ED data within the electron-localizability approach. The bonds with Bi participation are mostly two- or three-atomic (with the exception of one four-atomic interaction Mg1-Mg3-Mg4-Bi2). Invariably, bismuth contributes the major part to the bond population, i.e., all those interactions are strongly polar. The bond basins around both bismuth atoms are mostly located within the atomic (QTAIM) shapes of the bismuth species (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11 [top]), forming the anionic substructure in hp-Mg5Bi3. Summation of the populations of the basins around Bi1 and Bi2 yields 7.39 and 7.97 electrons, respectively. Ascribing these electrons to the Bi atoms results in effective charges NvalELI(Bi) of −2.61 for Bi1 and −2.97 for Bi2. The values are close to the conceptual one of −3. Usually, they are larger than estimated because of contributions of inner electrons to the valence bond basins32.

The ELI-D distribution in the hydride model Mg5Bi3H (Supplementary Fig. 12) is similar to that in Mg5Bi3. The ELI-D/QTAIM intersection method reveals pronounced polarity of the Mg-Bi and Mg-H bonds. Ascribing all electrons in the bond basins around Bi1, Bi2 and H (Supplementary Fig. 11, lower row) to the respective anion yields the NvalELI values of 8.3, 8.2, and 2.08 electrons, respectively, corresponding to Bi3− and H−. The finding is well in agreement with the conceptual values considering the effect mentioned above32.

The most interesting bond basin is the one of the four-atomic interaction between the magnesium atoms Mg2-Mg3-Mg4-Mg4 (light pink in Supplementary Fig. 10, middle and bottom). It has one of the largest populations (1.42 e−) in the compound. The partial ELI-D technique33 shows that the electronic states between the pseudo-gap and the Fermi level contribute most to that feature. The isolated tetra-cations [Mg4] and the anionic species around Bi complete the bonding picture of Mg5Bi3 (Fig. 6).

Determination of the hydrogen position

A known useful feature of the ELI (and the related electron localization function) is the ability to designate sites in crystal structures which are suitable locations for anions, specifically hydride34,35,36,37,38. Consequently, the ELI-D maximum pointing at the four-atomic bond between the magnesium atoms Mg2-Mg3-Mg4-Mg4 in Mg5Bi3 is identified as a potential position of the hydride ion in Mg5Bi3H. The negligible contribution of hydrogen to the X-ray scattering in bismuth compounds impedes the refinement of its coordinates by X-ray diffraction data. Consequently, the crystal structure including hydrogen is optimized using the experimental symmetry and lattice parameters. The finding that the resulting coordinates of the allocated hydride almost perfectly coincide with those of the fluorine position in Ca5Sb3F (a detailed comparison of atomic coordinates is shown in Table S2) impressively corroborates that the selected strategy represents an encouraging approach for intermetallic phases in general.

Consequently, the optimized atomic coordinates were used for the structure refinement with the X-ray diffraction data (see subsection Synthesis and Characterization) as well as for further quantum chemical calculations. Finally, the total energy for the reaction of Mg5Bi3 with elemental hydrogen to yield Mg5Bi3H1, was calculated according to the reaction equation

Here, the hydride is found to be lower in energy by 48.8 kJ mol−1 (at 0 K), in excellent agreement with the experimentally observed phase formation.

Methods

Synthesis

Preparation and sample handling were performed in argon-filled glove boxes (MBraun, H2O < 0.1 ppm; O2 < 0.1 ppm). The precursor samples were prepared from elemental magnesium (Alfa Aesar, 325 mesh, 99.8%) and bismuth (Alfa Aesar, 200 mesh, 99.999%) powders in the molar ratio 5:3. The samples were well mixed in an agate mortar for about 5–10 min to assure homogeneity. This mixture is placed in boron nitride crucibles for extreme conditions synthesis.

High-pressure high-temperature experiments were realized using a hydraulic multi-anvil press39. Pressure transmission is realized in MgO octahedra with an edge length of 18 mm. Reaction temperatures are adjusted by resistance heating of graphite sleeves. Calibrations of pressure and temperature were done by observing resistance changes of bismuth40 and thermocouple-calibrated runs both having been conducted before the synthesis experiments. The compound Mg5Bi3HX is synthesized at pressures between 4 and 5 GPa and within the temperature range of 973 to 1273 K. The maximal yield is obtained upon heating to 1073(50) K for 30 min followed by annealing at 773(30) K for three hours before quenching under load and decompression to ambient conditions.

Powder X-ray diffraction

Sample characterization and data collection for structure refinement were realized in transmission alignment with a Huber image plate Guinier camera G670 with a beam size on the sample of 1 × 10 mm using CuKα1 radiation, λ = 1.54056 Å All crystallographic calculations including lattice parameters and structure refinements on the basis of full diffraction profiles (Rietveld method) were performed using the WinCSD program package41.

Metallography

Sample composition and phase distribution were analyzed by metallographic analysis. Light microscopy images (Zeiss Axioplan 2 with CCD Camera) at various magnifications were done followed by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy on a scanning electron microscope SEM (Jeol JSM 7800 F) with an attached energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDXS) system (Quantax 400, Brucker, Silicon-Drift-Detector. Additionally, the wavelength dispersive X-ray spectroscopy analyses were performed with an electron microprobe (Cameca SX100 tungsten cathode). For these measurements, the selected sample surface was carefully prepared by argon-ion beam etching (Jeol IB 19520CCP). In order to avoid contamination of the clean surface by oxygen or water, the prepared specimen was transferred under inert conditions to the electron microprobe.

Thermal analysis

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) experiments were done in a Netzsch DSC 404 C device using Al2O3 crucibles (up to 773 K) or in sealed Ta ampoules (up to 1123 K). Measurements were done with a heating and cooling rate of 10 K/min in argon atmosphere.

The hydrogen content in the various samples (educts and products) Mg, Bi, Mg3Bi2 and Mg5Bi3Hx was determined by releasing the hydrogen into the gas phase by means of thermal desorption, i.e., decomposition and subsequent qualitative and quantitative analysis of the gas phase.

The composition of the gas phase was analyzed by a temperature-dependent process using a TG-MS system, which is a combination of a thermo-balance STA 409 CD (NETZSCH) and a quadrupole mass-spectrometer QMS 422 (Pfeiffer Vacuum). The installation of this system in an argon-filled glove box (MBraun) enables handling and measurement of especially air- or moisture-sensitive samples.

The individual samples were measured using heating and cooling rates of 5 K/min and corundum crucibles in a Knudsen cell with Ta inlay, perforated lid (Effusion bore diameter 0.2 mm) and a thermocouple type S (PtRh/Pt). The measurements were carried out in flowing argon atmosphere as purging gas (Ar 99.999% 50 ml/min with subsequent drying and oxygen post-purification via a Big Oxygen Trap (Trigon Technologies). The detection of gas particles was carried out in MID mode for ions with m/z 1 (H+), 2 (H2+), 16 (O+), 17 (HO+), 18 (H2O+), 24 (Mg+), 32 (O2+) 209 (Bi+) with 70 eV electron impact ionization.

Educts and products were investigated in the temperature range from 298 to 813 K using sample masses of 28.48 and 12.45 mg (Mg), 17.13 mg (Bi), 35.51 mg (Mg3Bi2), as well as 23.91 and 30.25 mg of Mg5Bi3Hx. Removal of hydrogen from elemental magnesium and bismuth was achieved under the same conditions and monitoring the hydrogen release.

The gases being released from the specimen were intermixed with a continuous argon purging-gas stream and directed to the ionization chamber of the mass spectrometer by using a skimmer located directly above the bore of the effusion crucible. Background mass spectra were recorded before the measurement by using the same conditions. We abstained from correcting the thermogravimetry data for buoyancy as this allows for a more suitable material combination of the crucible setup. The quantification of the released hydrogen was carried out by calibration using five independent measurements of NaH (Supplementary Fig. 3). The thermal decomposition of NaH shows only one sharp, well reproducible signal for the release of hydrogen into the gas phase between 250 and 400 °C with a maximum at 325 °C. Peak shape and baseline are ideally suited for using the hydrogen release during the thermal decomposition of NaH for quantitative calibration.

Quantum chemical calculations

Electronic structure calculations and chemical bonding analysis were performed with the all-electron, local orbital full‒potential technique (FPLO) within the local density approximation42 (Perdew‒Wang parametrization43, scalar relativistic calculation, standard basis set, 12 × 12 × 12 k points). The experimentally obtained atomic coordinates were optimized keeping the experimental lattice parameters constant. For the analysis of chemical bonding in position space, the ED and the ELI-D were calculated with a specialized module implemented in the FPLO program package44. The topology of ED and ELI-D was analyzed with the program DGrid45. The ED was integrated within atomic basins, i.e., spatial regions confined by zero-flux surfaces in the gradient field of ED and ELI-D, respectively (for additional information, see Supplementary Methods). This technique represents the procedure proposed in the Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecules (QTAIM46 and provides effective electron populations for the QTAIM atoms. Correspondingly, bond basins are the same type of confined regions associated to attractors in the valence region of the ELI-D gradient field. Further bonding relevant information is obtained from combined analysis of ED and ELI-D within the electron localizability approach47.

Data availability

The data sets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Differential calorimetry measurements are realized with NETZSCH Messung, version 6.1.0. and data are analysed using NETZSCH PROTEUS version 8.0.3. Thermogravimetry and mass spectroscopy measurement were done with the NETSCH Proteus software, version 6.1.0. (NETZSCH.com), and the Inficon AG Quadstar-32-bit software, version 7.02 (quadstar-32-bit.software.informer.com). For integration of the experimental charge, least squares fit of the calibration data and display of the experimental data as well as refinement results, we used OriginPro 2020b (64-bit, OriginLab Corporation). X-ray diffraction data are collected with G670 Imaging Plate Guinier Camera, version 6.0 build 86 by Huber Diffraktionstechnik GmbH (xhuber.com). WinCSD program package may be downloaded upon registration (wincsd.eu). The crystal structure is visualized with Atoms version 6.3.4. The FPLO package may be downloaded from www.fplo.de after registration. The ELI-D module for FPLO is available upon request from the authors. Please notice that German embargo regulations are in place for certain countries and institutions. Information on the AVIZO software for visualization of ELI-D and charge density is available at www.thermofisher.com.

Change history

28 July 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01616-w

References

Zhuravlev, N. N. & Melik Adamyan, V. R. Study of the crystal structure of the superconducting compounds SrBi3 and BaBi3. Sov. Phys. Crystallogr.6, 121–124 (1961).

Iyo, A. et al. Large enhancement of superconducting transition temperature of SrBi3 induced by Na substitution for. Sr. Sci. Rep. 5, 10089 (2015).

Winiarski, M. J. et al. Superconductivity in CaBi2. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 21737–21745 (2016).

Zhang, H. et al. Topological insulators in Bi2Se3, Bi2Te3 and Sb2Te3 with a single Dirac cone on the surface. Nat. Phys. 5, 438–442 (2009).

Ren, Z., Taskin, A. A., Sasaki, S., Segawa, K. & Ando, Y. Large bulk resistivity and surface quantum oscillations in the topological insulator Bi2Te2Se. Phys. Rev. B 82, 241306 (2010).

Liu, Z. K. et al. Discovery of a three-dimensional topological Dirac semimetal, Na3Bi. Science 343, 864–867 (2014).

Zintl, E. & Kaiser, H. Über die Fähigkeit der Elemente zur Bildung negativer Ionen. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 211, 113–131 (1933).

Zintl, E. & Husemann, E. Bindungsart und Gitterbau binärer Magnesiumverbindungen. Z. Physikal. Ch. B 21, 138–155 (1933).

Schäfer, H., Eisenmann, B. & Müller, W. Zintl phases: transitions between metallic and ionic bonding. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 12, 693–712 (1973).

Barnes, A. C., Guo, C. & Howells, W. S. Fast-ion conduction and the structure of β-Mg3Bi2. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 6, L467–L471 (1994).

Schwarz, U. et al. CoBi3: a binary cobalt–bismuth compound and superconductor. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 9853–9857 (2013).

Walsh, J. P. S. et al. MnBi2: a metastable high-pressure phase in the Mn−Bi system. Chem. Mater. 31, 3083–3088 (2019).

Walsh, J. P. S., Clarke, S. M., Meng, Y., Jacobsen, S. D. & Freedman, D. E. Discovery of FeBi2. ACS Cent. Sci. 2, 867–871 (2016).

Clarke, S. M. et al. Discovery of a superconducting Cu–Bi intermetallic compound by high-pressure synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 13446–13449 (2016).

Guo, K. et al. Weak interactions under pressure: hp-CuBi and its analogues. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 5620–5624 (2017).

Powderly, K. M. et al. High-pressure discovery of β-NiBi. Chem. Commun. 53, 11241–11244 (2017).

Altman, A. B. et al. Computationally directed discovery of MoBi2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 214–222 (2021).

Corbett, J. D. & Leon-Escamilla, E.-A. Role of hydrogen in stabilizing new hydride phases or altering old ones. J. Alloy. Compd. 356–357, 59–64 (2003).

Hurng, W.-M. & Corbett, J. D. Alkaline-earth-metal antimonides and bismuthides with the A5Pn3 stoichiometry. Interstitial and other Zintl phases formed on their reactions with halogen or sulfur. Chem. Mater. 1, 311–319 (1989).

Grube, G., Mohr, L. & Bornhak, R. Elektrische Leitfähigkeit und Zustandsdiagramm bei binären Legierungen. Das System Magnesium-Wismut. Z. Elektrochem. 40, 143–150 (1934).

Wobst, M. Das ternäre system Magnesium-Bismut-Zinn. Z. Phys. Chem. 219, 239–265 (1962).

Oh, C.-S., Kang, S.-Y. & Lee, D. N. Assessment of the Mg-Bi system. Calphad 16, 181–191 (1992).

Parthé, E. Elements of Inorganic Structural Chemistry Vol. 38 (Petit-Lancy, Switzerland, 1996).

Parthé, E. Valence-electron concentration rules and diagrams for diamagnetic, non-metallic iono-covalent compounds with tetrahedrally coordinated anions. Acta Crystallogr. B 29, 2808–2815 (1973).

Zhao, J.-T. & Corbett, J. Square pyramidal clusters in La3ln5 and Y3In5. La3In5 as a metallic Zintl phase. Inorg. Chem. 34, 378–383 (1995).

Nesper, R. Structure and chemical bonding in Zintl-phases containing lithium. Prog. Solid St. Chem. 20, 1–45 (1990).

Nesper, R. Bonding patterns in intermetallic compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 30, 789–817 (1991).

Freccero, R. et al. Excess” electrons in LuGe. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 6457–6461 (2021).

Baranov, A., Kohout, M., Wagner, F. R., Grin, Y. & Bronger, W. Spatial chemistry of the aluminum-platinum compounds: a quantum chemical approach. Z. Kristallogr. 222, 527–531 (2007).

Yu. Grin, A., Fedorchuk, R. J. & Wagner, F. R. Atomic charges and chemical bonding in Y-Ga compounds. Crystals 8, 99 (2018).

Agnarelli, L. et al. Charge transfer in Be-Ru compounds. Chem. Eur. J. 29, e202302301 (2023).

Freccero, R. et al. Polar-covalent bonding beyond the Zintl picture in intermetallic rare-earth germanides. Chem. Eur. J. 25, 6600–6612 (2019).

Wagner, F. R., Bezugly, V., Kohout, M. & Grin, Y. Charge decomposition analysis of the electron localizability indicator: a bridge between the orbital and direct space representation of the chemical bond. Chem. Eur. J. 13, 5724–5741 (2007).

Savin, A., Nesper, R., Wengert, S. & Fässler, T. F. ELF: the electron localization function. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 36, 1808–1832 (1997).

Lang, D. A. & Zaikina, J. V. Ca2LiC3H: a new complex carbide hydride phase grown in metal flux. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 17523–17530 (2010).

Al Alam, A. F. & Matar, S. F. Hydrogen insertion effects on the magnetic properties and chemical bonding within C14 Laves phases. Prog. Solid State Chem. 36, 192–212 (2008).

Matar, S. F. Intermetallic hydrides: a review with ab initio aspects. Prog. Solid State Chem. 38, 1–37 (2010).

Feng, X.-J. et al. Zintl-Phase Sr3LiAs2H: crystal structure and chemical bonding analysis by the electron localizability approach. Chem. Eur. J. 21, 14471–1477 (2015).

Walker, D., Carpenter, M. A. & Hitch, C. M. Some simplifications to multianvil devices for high pressure experiments. Am. Mineral. 75, 1020–1028 (1990).

Young, D. A. Phase Diagrams of the Elements (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1991).

Akselrud, L. & Grin, Y. WinCSD: software package for crystallographic calculations (Version 4). J. Appl. Crystallogr. 47, 803–805 (2014).

Koepernik, K. & Eschrig, H. Full-potential nonorthogonal local-orbital minimum-basis band-structure scheme. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1743–1757 (1999).

Perdew, J. P. & Wang, Y. Accurate and simple analytic representation of the electron-gas correlation energy. Phys. Rev. B 45, 13244–13249 (1992).

Ormeci, A., Rosner, H., Wagner, F. R., Kohout, M. & Grin, Y. Electron Localization Function in Full-Potential Representation for Crystalline Materials. J. Phys. Chem. A 110, 1100–1105 (2006).

Kohout, M. DGrid Versions 4.6−5.0 (Dresden, Germany, 2018−2021).

Bader, R. F. W. Atoms in Molecules-A Quantum Theory 3rd edn. 222–237 (Oxford University Press, New York, 1990).

Wagner, F. R. & Grin, Y. Chemical bonding analysis in position space. In Comprehensive Inorganic Chemistry III (eds. Reedijk, J. & Poeppelmeier, K. R.) 222–237 (Elsevier, 2023).

Acknowledgements

Valuable discussions with Jürgen Nuss (Max Planck Institute for Solid State Research, Stuttgart, Germany) and Steffen Wirth (Max Planck Institute for Chemical Physics of Solids, Dresden, Germany) are gratefully acknowledged. We thank Susann Leipe for supporting high-pressure syntheses and express our gratitude to Sylvia Kostmann for metallographic analyses and Susann Scharsach for TG-MS measurements. Financial support for T. N. by the International Max Planck Research School for Chemistry and Physics of Quantum Materials (IMPRS-CPQM) is gratefully recognized.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.N., L.A., M.S., and U.B. prepared and performed experiments; Y.G. performed DFT calculations and bonding analysis; U.S. supervised the project; all authors have edited the draft written by Y.G. and U.S. and given approval to the final version of the manuscript. The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Neziraj, T., Akselrud, L., Schmidt, M. et al. Locating hydrogen in the Mg5Bi3Hx Zintl phase. Commun Chem 8, 132 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01530-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01530-1