Abstract

The solid-phase enthalpy of formation (∆Hf, solid) of energetic materials was generally predicted from the gas-phase enthalpy of formation (∆Hf, gas) and sublimation enthalpy (∆Hsub). Here, the standard ∆Hf, solid of energetic materials is directly obtained from density functional theory (DFT) calculations by computing the enthalpy difference between the solid-phase energetic material and its constituent elements in their reference states. To reduce the errors in DFT calculations, a concept of isocoordinated reaction is introduced, i.e., the reference states are selected based on the coordination numbers of all atoms in the energetic material. This DFT method for ∆Hf, solid calculation does not require experimental input, data fitting, or machine learning. For more than 150 energetic materials collected from the literature, the mean absolute error (MAE) of ∆Hf, solid for the DFT method is 39 kJ mol−1 (or 9.3 kcal mol−1) referring to the literature. Our demonstration raises prospects for first-principles prediction of the properties of energetic materials, and the proposed method for ∆Hf, solid calculation is also promising for other materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Energetic materials include explosives, propellants, pyrotechnics, and other energy sources widely used in both military and civilian spheres1. The enthalpy of formation (∆Hf) and mass density (ρ) are crucial properties for energetic materials, because they fundamentally determine the energy output and combustion/detonation properties of energetic materials2,3. The theoretical calculation of ∆Hf and ρ for energetic materials is important due to the high cost and safety requirements in their experimental studies, especially for novel energetic materials without prior knowledge. Moreover, some novel energetic materials are not available in sufficient quantities for extensive experimental studies of their physical and chemical properties4. Therefore, the theoretical calculation of ∆Hf and the density of energetic materials is highly desired.

The ∆Hf of a compound is the change of enthalpy during the formation of one mole of the substance from its constituent elements in their reference states. As enthalpy is a state function, the ∆Hf can be calculated from the sum of the enthalpy changes for a series of individual reactions, either real or fictitious, according to Hess’s law5. Experimentally, the solid-phase ∆Hf (∆Hf, solid) of energetic materials can be calculated from the heat of combustion, which is measured by the bomb combustion calorimetry6. This method is challenging for explosives, because the combustion of explosives may grow into deflagration and detonation of explosives due to the fast self-oxidation-reduction. The products of self-oxidation-reduction reactions can be different from normal combustion with external O2. Uncertainty in the products leads to uncertainty of calorimetry7. Theoretically, the ∆Hf, solid values are generally computed from ∆Hf of gas (∆Hf, gas) and the sublimation enthalpy (∆Hsub). Meanwhile, ∆Hf, gas, and ∆Hsub are usually predicted by models from fitting or machine learning of “training” molecules8,9,10,11,12,13. However, it is difficult to obtain reliable experimental data of ∆Hf, gas, and ∆Hsub for energetic materials due to the low volatility and metastability of energetic materials14. Therefore, this “∆Hf, gas minus ∆Hsub” method is still faced with the problem of lacking accurate training data.

Why did previous theoretical studies mainly focus on gas-phase ∆Hf, gas instead of solid-phase ∆Hf, solid of energetic materials? Because the theoretical simulation of a single molecule can be much more accurate and faster than molecular crystals15. Several methods have been proposed for the prediction of gas-phase ∆Hf, gas, such as atomization energy16,17,18, atom/group equivalent10,19, and isodesmic reaction17,18,20. The atomization energy method converts total DFT energies to enthalpies of formation via atomization and formation reaction procedures, which rely on accurate ∆Hf and high-level ab initio simulations of isolated atoms and molecules. The atom/group equivalent method employs fitting or machine learning of existing ∆Hf, gas data to predict ∆Hf, gas of new molecules based on the numbers of each atom or functional group. Both the atomization energy and atom/group equivalent methods are faced with error accumulation when the size of the molecule increases. The isodesmic reaction method reduces the energy errors in the DFT calculation of chemical bonds formed and broken due to the constant number of bonds of a given type21,22, but it requires knowing the ∆Hf, gas of all the other species in the reaction equation to calculate the ∆Hf, gas of intended products.

Herein, we propose a first-principles method for the direct and accurate calculation of solid-phase ∆Hf, solid of energetic materials, based on the DFT energies and enthalpy corrections of the molecular crystal and its constituent elements in reference states. The reference states are a series of small molecules determined by the coordination number of the central atoms. This method is as simple as atomization energy and atom/group equivalent methods, and it can effectively reduce the errors in the DFT calculation of energy difference between the molecular crystal and reference small molecules, similar to the isodesmic reaction method. In other words, it has the advantages of previous methods and avoids their reliance on data fitting or high-level ab initio calculations, and it is applicable to solids. For more than 150 energetic materials (see the Supplementary Data 1) collected from literature14,19,23, the mean absolute error (MAE) of ∆Hf, solid for this first-principles coordination (FPC) method is 39 kJ mol−1 (or 9.3 kcal mol−1), referring to previously reported data. Due to the considerable uncertainty of experimental ΔHf, solid data of energetic materials14,24, the prediction accuracy cannot be improved infinitely when experimental data are used as reference values. The performance of this new method is comparable to that of previous methods in terms of standard error and slope of the linear regression with experimental data.

Results and discussion

Density calculation

To obtain the solid-phase ∆Hf, solid of energetic materials by DFT calculations, their crystal structures and lattice parameters should be optimized by DFT structural relaxation. DFT-D3 method with Becke-Johnson damping function25 is adopted to include the vdW (dispersion) correction. The initial crystal structures of 156 energetic materials are retrieved from the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD)26, all of which are dynamically stable structures obtained from experiments. The mass densities of energetic materials from our DFT-D3 calculations are in reasonable agreement with experimental room-temperature densities in the CSD. If only low-temperature densities are available in experiments, the room-temperature densities (ρ298.15K) are estimated by the volume expansion formula:

where ρT is the low-temperature density, T is the corresponding temperature, and av is the thermal expansion coefficient. This work adopts a typical av value of 1.5 × 10−4 K−127. Note that different materials actually have different av, and the ρ298.15K data can be improved if individual av is used for each material. The comparison and linear regression between DFT and literature (CSD) densities are shown in Fig. 1a. Each red point represents an energetic material, and its horizontal and vertical coordinates are the literature density and DFT density, respectively. The black dashed line represents equivalent DFT and literature densities, and the two dashed gray lines represent the difference values of ±0.05 g cm−3 between DFT and literature densities. Most of the energetic materials fall between the gray lines and have density errors smaller than 0.05 g cm−3. The mean absolute error (MAE) is 0.026 g cm−3. The blue line is the linear fit of the density data. The slope is 0.85 with a standard error of 0.01. The standard error of the regression is 0.016 g cm−3. Interestingly, the DFT calculations tend to overestimate the densities of low-density energetic materials, while slightly underestimating the densities of high-density energetic materials. The reason for this phenomenon is still elusive and requires future investigations. The distribution of density error is further presented in Fig. 1b, which shows that 77% of the studied energetic materials have larger DFT density than the reference CSD density (positive density error), and the maximum deviation is ~0.07 g cm−3. Others have negative density errors, and the maximum absolute error is smaller than 0.06 g cm−3. The effect of density error on the calculation of solid-phase ∆Hf, solid will be discussed later in this work.

a Comparison and linear regression between DFT and literature densities (ρ) of energetic materials. Gray dashed lines represent ±0.05 g cm−3 errors. Standard error of the regression (SER) and slope of the linear regression are shown. b Distribution of density error between DFT calculations and literature.

ΔH f, solid calculation

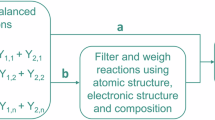

Although the DFT calculations can well describe the mass density of energetic materials, the direct calculation of their solid-phase ∆Hf has always been a challenge. High-level DFT calculations of solid-phase energetic materials are unaffordably expensive. Currently, there are no ab initio methods reported for the ΔHf, solid calculation of energetic materials. For affordable DFT calculations, the DFT energy errors are large in the computation of the enthalpy differences between chemically dissimilar systems28,29, i.e., the compound and its elemental constituents, based on the definition of the enthalpy of formation. Similar to the hierarchy of reaction conditions proposed for hydrocarbons and the isocoordinate concept proposed for ligands and complexes30,31, we take another step forward on the basis of isodesmic reaction for energetic materials. For an isodesmic reaction, the formal type and number of chemical bonds are unchanged before and after the reaction. Herein, we fix the number of chemical bonds but ignore the type of bonds to construct a type of reaction in which the coordination number of each atom remains unchanged in the reactants and products. This type of reaction may be termed “isocoordinated reaction”. We modify the classical atom/group equivalent method for the quantum mechanical calculations of the gas-phase ∆Hf10,19, and propose a coordination number-based method for the first-principles calculations of solid-phase ∆Hf, solid of energetic materials based on the “isocoordinated reaction”. In this method, the elemental constituents, which can be regarded as the reactants of “isocoordinated reactions”, are a series of molecules with different coordination numbers of the central atom, whose coordination atoms are H atoms for single bonds or the same as the central atom for double/triple bonds (Fig. 2a). For H, the coordination number should be one, and the corresponding reference molecule is H2. For O, the coordination number can be one or two, and the corresponding reference molecules are O2 and H2O, respectively. For N, the coordination number could be one, two, or three, and the corresponding reference molecules are N2, N2H2, and NH3, respectively. For C in energetic materials, the coordination number may be two, three, and four, and the corresponding reference molecules are C2H2, C2H3, and CH4, respectively.

The coordination number of each atom in the energetic materials is determined by counting its neighboring atoms (within proper cut-off bond lengths). For example, in the TNT molecule as shown in Fig. 2b, all the C atoms in the benzene ring have the same coordination number of three, and the coordination number of the methyl carbon is four. The coordination numbers of N and O in the nitro are three and one, respectively. For 2-diazo-4,6-dinitrophenol (DINOL, Fig. 2c), the coordination numbers of the two N atoms in the diazo are one and two, respectively, and all the O and C atoms are one- and three-coordinated, respectively. In addition, all the H atoms in TNT and DINOL are one-coordinated. This method does not need to analyze the bond order, which sometimes is ambiguous and controversial. Based on the coordination numbers and corresponding reference molecules, the solid-phase enthalpy of formation (∆Hf, solid) of energetic materials can be calculated as follows:

where HEM is the DFT enthalpy per structural unit of the solid-phase energetic material, nX-m is the number of m-coordinated X (X = H, O, N, C) atoms in the structural unit of the energetic material. HX-m is the “atom equivalent” enthalpy of m-coordinated X atoms. The HX-m are determined by the enthalpies of the reference molecules X-m (H(X-m)) as follows:

where the structures of X-m molecules are shown in Fig. 2a, and the calculation method of H(X-m) can be found in the “Methods” section.

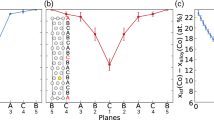

All the ∆Hf, solid of 156 energetic materials are calculated by this coordination number-based method, and the comparison with literature data14,19,23 is shown in Fig. 3a. The MAE between DFT and literature enthalpies is 39 kJ mol−1 (i.e., 9.3 kcal mol−1). The red line is the linear fitting of the ∆Hf, solid data. The slope is 0.93 with a standard error of 0.01. The standard error of the regression is 48.5 kJ mol−1 (i.e., 11.6 kcal mol−1). The gray dashed lines represent ±100 kJ mol−1 errors between DFT and literature enthalpies. Most of the data points are located between the two dashed lines, and the maximum positive and negative deviations are 162 and −207 kJ mol−1, respectively. In consideration of the non-negligible uncertainty in experimental measurements24 and the wide range of ∆Hf, solid values (−1000~1300 kJ mol−1), the error and deviations of this method are acceptable. The distribution of ∆Hf, solid error is shown in Fig. 3b. About 60% (or 40%) of the DFT calculated ∆Hf, solid errors are higher (or lower) than the corresponding literature ones, and most of the errors are distributed around zero. Therefore, this first-principles coordination method can effectively predict the solid-phase ∆Hf, solid of energetic materials, with reasonable accuracy. In addition, when only N2, O2, and H2 are used as the reference molecules for N, O, and H, respectively, and their specific coordination numbers in the energetic materials are ignored, the mean absolute error of ∆Hf, solid calculation increased to 107 kJ mol−1, which is much larger than the one (39 kJ mol−1) of the coordination number based method. Therefore, the coordination scheme significantly reduced the errors in the DFT calculation of the energy difference between the molecular crystal and reference small molecules.

a Comparison and linear regression between solid-phase ∆Hf, solid of energetic materials from DFT calculations and literature. Gray dashed lines represent ±100 kJ mol−1 errors. Standard error of regression (SER) and slope of the linear regression are shown. b Distribution of ∆Hf, solid error between DFT calculations and literature.

∆Hf, solid error versus density error

The scatter plot of density error and ∆Hf, solid error, is shown in Fig. 4a to see whether the Hf, solid error, is related to the density error. Obviously, the distribution of data points in Fig. 4a is highly disordered. Small density errors do not mean small ∆Hf, solid errors, and vice versa. Large density errors also do not mean large ∆Hf, solid errors, and vice versa. The Pearson coefficient (r) between them is only 0.253. Pearson's coefficient can range from −1 to +1, where ±1 indicates the strongest correlation and 0 indicates no correlation. It indicates that the density error has a low correlation with the DFT calculations of ∆Hf, solid, which mainly depends on the molecular structure of energetic materials. The scatter plots of density and ∆Hf, solid are presented in Fig. 4b, c, for literature data and DFT calculations, respectively. The data distributions are still quite dispersed in Fig. 4b, c, and these two plots are similar, which further indicates the good performance of DFT calculations of density and ∆Hf, solid. The main difference between them is that DFT calculations tend to overestimate the density of energetic materials with relatively small density (1.4~1.7 g cm−3), which is in accordance with the data in Fig. 1a.

The density effect on the ∆Hf, solid is further calculated for several typical energetic materials with totally different density errors. Among them, benzotrifuroxan (BTF, Fig. 5a) has the most negative density error (−0.058 g cm−3), octogen (HMX, Fig. 5b) has a near-zero density error, and p-nitroaniline (Fig. 5c) has the most positive density error (0.072 g cm−3). For all three energetic materials, the ∆Hf, solid is calculated at different densities by changing the volume of their unit cells. The densities distribute around the experimental density values, and the deviations are large enough to take into account all the density error between DFT calculations and literature (Fig. 1b). The change of calculated ∆Hf, solid is less than ±10 kJ mol−1 when the change of density is less than ±0.075 g cm−3 as shown in Fig. 5, which indicates the density error has an insignificant effect on the accuracy of ∆Hf, solid calculation in our coordination number based DFT method. In addition, the density effect for p-nitroaniline is less significant than BTF and HMX, which may be because of the much smaller density of p-nitroaniline.

Comparison with previous methods

To compare our DFT method for ∆Hf, solid calculation with previous methods, two sets of experimental ∆Hf, solid data of energetic materials are obtained from two references14,19, which proposed two ∆Hf, solid prediction methods. One of them is a semi-empirical computational method proposed by Byrd et al. in ref. 19, which predicted the formation enthalpy of gas (∆Hf, gas) through atom and group equivalents, and predicted sublimation enthalpy (∆Hsub) based on electrostatic potentials isosurfaces. The parameters in the calculation equations of both ∆Hf, gas, and ∆Hsub are obtained by least-squares fits with experimental values. The other one is a method combining calculation and experiment proposed by Muravyev et al. in ref. 14, which calculated ∆Hf, gas by high-level ab initio calculations and obtained ∆Hsub by advanced thermal analysis experiments. As our DFT method for ∆Hf, solid calculation requires the crystal structure of the solid-phase material, energetic materials in the aforementioned two references that have available crystal structures in the Cambridge Structural Database are retrieved, and their ∆Hf, solid is calculated by our DFT method for comparison. The linear regressions of our DFT ∆Hf, solid with experimental values, are shown in Fig. 6a, b, where the experimental data come from Byrd et al.19 and Muravyev et al.14, respectively. For Muravyev et al.14, some energetic materials have more than one experimental ∆Hf, solid source. In this case, the average value of different sources is calculated and used as the experimental ∆Hf in Fig. 6b. The performance of previous methods is shown in Fig. 6c, d, for Byrd et al.19 and Muravyev et al.14, respectively.

Linear regression of our DFT calculated solid-phase ∆Hf, solid with experimental data collected from (a) Byrd et al.19 and b Muravyev et al.14. The solid-phase ∆Hf, solid prediction performance of the methods described in (c) Byrd et al.19 and d Muravyev et al.14. Gray dashed lines represent ±100 kJ mol−1 errors. Standard error of regression (SER) and slope of the linear regression are shown.

All the slope values of the fitting lines are close to 1, especially for our DFT method, which has a slope value of 0.99 for both datasets, as shown in Fig. 6a, b. The standard errors of regression (SER) of our DFT method are 38.6 kJ mol−1 (Fig. 6a) and 44.3 kJ mol−1 (Fig. 6b), which are larger than the previous methods: 31.6 kJ mol−1 (Fig. 6c) and 34.6 kJ mol−1 (Fig. 6d), respectively. In the aspect of accuracy, due to the considerable uncertainty of experimental ΔHf, solid data of energetic materials14,24, the prediction accuracy cannot be effectively improved if experimental data are used as reference values, unless selective data screening is performed. Note that the “accuracy” is based on the comparison with experimental data, and our method is an ab initio method, while previous methods rely on data fitting or the input of experimental data. It is not surprising that the “accuracy” of our method is not better than previous methods. Our DFT ΔHf, solid data is totally independent of experimental measurements. By using low-cost DFT calculations and without any data fitting, the performance of this method is comparable to previous well-known methods, which rely on experimental gas-phase ΔHf, gas or sublimation ΔHsub. This work manifests that reasonable ab initio ΔHf, solid values can be obtained in benefit from error cancellations through a simple isocoordinated scheme. The DFT ΔHf, solid data of more than 150 energetic materials, can be a supplement to the database of thermodynamic properties of energetic materials.

Conclusions

In summary, we propose a DFT calculation method of solid-phase enthalpy of formation (∆Hf, solid) for CHON-containing energetic materials without any data fitting or machine learning. The ∆Hf, solid is directly calculated from the enthalpies of bulk energetic materials and constituent elements in their reference states, which are small molecules with different coordination numbers for the central atom. The reference molecules are H2 for hydrogen; O2 and H2O for oxygen; N2, N2H2, and NH3 for nitrogen; and C2H2, C2H4, and CH4 for carbon. To calculate the enthalpies of bulk energetic materials, the crystal structure and lattice are first optimized by DFT-D3 calculations. The calculated densities are in reasonable agreement with experimental values at room temperature, for a dataset with more than 150 energetic materials. The mean absolute errors (MAE) for density and ∆Hf, solid are only 0.026 g cm−3 and 9.3 kcal mol−1, respectively. The new method is slightly less accurate than previous methods that rely on the input of experimental data. In consideration of the non-negligible uncertainty in experimental measurements, the ab initio ∆Hf, solid data provided in this work are a valuable supplement to the database of thermodynamic properties of energetic materials. The complete data are summarized in the Supplementary Data 1. In addition, the density error is found to have an insignificant effect on the calculation of ∆Hf, solid. This work provides a first-principles method for the calculation of ∆Hf, solid, which can be helpful in the design and applications of novel energetic materials.

Methods

Computational methods

Accurate first-principles calculations were performed using density functional theory as implemented in the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)32. The ion-electron interactions were treated with the projected augmented wave pseudopotentials33, and the plane-wave basis set was cut off at 520 eV. Generalized gradient approximation with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof functional was used to determine the exchange-correlation energy34. The reference molecules were put in boxes larger than 20 Å in each direction, and a single Gamma k-point was used. The crystal structures of energetic materials were retrieved from the Cambridge Structural Database. The k-point grid used for the Brillouin-zone integration was denser than 0.2 Å−1 in each direction and sampled by a gamma-centered Monkhorst-Pack scheme35. Test calculations with a k-point grid denser than 0.1 Å−1 result in nearly the same density and ΔHf, solid of energetic materials. The DFT-D3 method with Becke-Johnson damping function was used to include van der Waals interactions25. All structures were fully relaxed by the conjugate gradient method until the residual force on each atom was less than 0.01 eV Å−1. In addition, our test calculations indicated that the ΔHf, solid calculation method proposed in this work is generally insensitive to different dispersion corrections, but the usage of revised exchange-correlation functionals may lead to significant errors.

Enthalpy calculations

To obtain the enthalpy corrections at finite temperature and pressure, the second-order derivatives of the total energy with respect to the position of the ions were computed in the VASP using a finite differences approach. The dynamical matrix was constructed and diagonalized, and the phonon modes and frequencies of single-molecule systems were calculated. The enthalpy of molecule X-m (H(X-m)) was expressed as follows:

where U is the internal energy, EZPE is the zero-point energy, and PV is the volume work. Although the DFT-D3 method is used, U is the conventional Kohn-Sham DFT energy without the dispersion correction term. EZPE is calculated from the frequency calculation, and PV is calculated based on the ideal gas approximation (PV = NRT). More details of these thermo energy corrections for enthalpy can be found in an open-source VASPKIT code36. ∆Hf, X-m is the reported enthalpy of formation of the reference molecule X-m, which can be retrieved from an open-source database37.

Data availability

All relevant data are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Badgujar, D. M., Talawar, M. B., Asthana, S. N. & Mahulikar, P. P. Advances in science and technology of modern energetic materials: An overview. J. Hazard Mater. 151, 289–305 (2008).

Kamlet, M. J. & Jacobs, S. J. Chemistry of detonations. I. A simple method for calculating detonation properties of C–H–N–O explosives. J. Chem. Phys. 48, 23–35 (1968).

Kubota, N. Propellants and Explosives: Thermochemical Aspects of Combustion (John Wiley & Sons, 2015).

Muravyev, N. V. What shall we do with the computed detonation performance? Comment on “1,3,4-Oxadiazole bridges: a strategy to improve energetics at the molecular level”. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 11568–11570 (2021).

Hess, H. H. Recherches Thermochimiques. Bull. Sci. Acad. Imp. Sci. (St. Petersburg) 8, 257–272 (1840).

Jessup, R. S. Precise Measurement of Heat of Combustion With A Bomb Calorimeter, Vol. 7 (US Department of Commerce, National Bureau of Standards, 1960).

Sun, Q. et al. Reply to “Comment on ‘Studies on thermodynamic properties of FOX-7 and its five closed-loop derivatives’”. J. Chem. Eng. Data 62, 577–577 (2017).

Habibollahzadeh, D., Grice, M. E., Concha, M. C., Murray, J. S. & Politzer, P. Nonlocal density functional calculation of gas phase heats of formation. J. Comput. Chem. 16, 654–658 (1995).

Politzer, P., Murray, J. S., Edward Grice, M., Desalvo, M. & Miller, E. Calculation of heats of sublimation and solid phase heats of formation. Mol. Phys. 91, 923–928 (1997).

Rice, B. M., Pai, S. V. & Hare, J. Predicting heats of formation of energetic materials using quantum mechanical calculations. Combust. Flame 118, 445–458 (1999).

Suntsova, M. A. & Dorofeeva, O. V. Prediction of enthalpies of sublimation of high-nitrogen energetic compounds: modified Politzer model. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 72, 220–228 (2017).

Liu, R. et al. QSPR models for sublimation enthalpy of energetic compounds. Chem. Eng. J. 474, 145725 (2023).

Chen, C. et al. Accurate machine learning models based on small dataset of energetic materials through spatial matrix featurization methods. J. Energy Chem. 63, 364–375 (2021).

Muravyev, N. V., Monogarov, K. A., Melnikov, I. N., Pivkina, A. N. & Kiselev, V. G. Learning to fly: thermochemistry of energetic materials by modified thermogravimetric analysis and highly accurate quantum chemical calculations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 23, 15522–15542 (2021).

Karton, A. A computational chemist’s guide to accurate thermochemistry for organic molecules. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 6, 292–310 (2016).

Curtiss, L. A., Raghavachari, K., Redfern, P. C. & Pople, J. A. Assessment of Gaussian-2 and density functional theories for the computation of enthalpies of formation. J. Chem. Phys. 106, 1063–1079 (1997).

Suntsova, M. A. & Dorofeeva, O. V. Use of G4 theory for the assessment of inaccuracies in experimental enthalpies of formation of aromatic nitro compounds. J. Chem. Eng. Data 61, 313–329 (2016).

Suntsova, M. A. & Dorofeeva, O. V. Use of G4 theory for the assessment of inaccuracies in experimental enthalpies of formation of aliphatic nitro compounds and nitramines. J. Chem. Eng. Data 59, 2813–2826 (2014).

Byrd, E. F. C. & Rice, B. M. Improved prediction of heats of formation of energetic materials using quantum mechanical calculations. J. Phys. Chem. A 110, 1005–1013 (2006).

Raghavachari, B. K., Stefanov, B. B. & Curtiss, L. A. Accurate density functional thermochemistry for larger molecules. Mol. Phys. 91, 555–560 (1997).

Dorofeeva, O. V. & Osina, E. L. Performance of DFT, MP2, and composite ab initio methods for the prediction of enthalpies of formations of CHON compounds using isodesmic reactions. Comput. Theor. Chem. 1106, 28–35 (2017).

Chan, B., Collins, E. & Raghavachari, K. Applications of isodesmic-type reactions for computational thermochemistry. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 11, e1501 (2021).

Muravyev, N. V., Wozniak, D. R. & Piercey, D. G. Progress and performance of energetic materials: open dataset, tool, and implications for synthesis. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 11054–11073 (2022).

Muravyev, N. V., Pivkina, A. N. & Kiselev, V. G. Comment on “Studies on thermodynamic properties of FOX-7 and its five closed-loop derivatives”. J. Chem. Eng. Data 62, 575–576 (2017).

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1456–1465 (2011).

Groom, C. R., Bruno, I. J., Lightfoot, M. P. & Ward, S. C. The Cambridge Structural Database. Acta Crystallogr. B 72, 171–179 (2016).

Fischer, D., Klapötke, T. M. & Stierstorfer, J. Synthesis and characterization of diaminobisfuroxane. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 5808–5811 (2014).

Lany, S. Semiconductor thermochemistry in density functional calculations. Phys. Rev. B 78, 245207 (2008).

Stevanović, V., Lany, S., Zhang, X. & Zunger, A. Correcting density functional theory for accurate predictions of compound enthalpies of formation: Fitted elemental-phase reference energies. Phys. Rev. B 85, 115104 (2012).

Wheeler, S. E., Houk, K. N., Schleyer, Pv. R. & Allen, W. D. A hierarchy of homodesmotic reactions for thermochemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 2547–2560 (2009).

Lima, N. B. D., Silva, A. I. S., Santos, V. F. C., Gonçalves, S. M. C. & Simas, A. M. Europium complexes: choice of efficient synthetic routes from RM1 thermodynamic quantities as figures of merit. RSC Adv. 7, 20811–20823 (2017).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Blochl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Wang, V., Xu, N., Liu, J.-C., Tang, G. & Geng, W.-T. VASPKIT: a user-friendly interface facilitating high-throughput computing and analysis using VASP code. Comput. Phys. Commun. 267, 108033 (2021).

Ruscic, B. & Bross, D. H. Active thermochemical tables (ATcT) thermochemical values ver. 1.124 (Argonne National Lab., United States, 2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Z. and D.L. conceived the idea, performed the work, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. M.H. and X.Y. helped with data collection. R.L. and Y.Y. supervised the project. All authors contributed to the writing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Partha Sarathi Ghosh and the other anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhong, L., Liu, D., Hu, M. et al. First-principles calculations of solid-phase enthalpy of formation of energetic materials. Commun Chem 8, 142 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01544-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01544-9