Abstract

Cyclic β-(1→2)-d-glucan (CβG) is a unique carbohydrate derivative produced by pathogenic bacteria of the genus Brucella. Controversial opinions regarding the use of CβG in brucellosis diagnosis have been published. Herein we report the first synthesis of spacered oligo-β-(1→2)-d-glucosides related to the fragments of CβG and containing up to 5 glucose units. Although the desired di- and trisaccharides could be obtained using standard methods, the synthesis of tetra- and pentasaccharides required substantial effort. The obtained oligosaccharides exhibited complex dependencies of their NMR spectral data on the chain length, explained by a tendency to form helical structures. Despite high production of the CβG by Brucella, antibodies to β-(1→2)-d-glucosides detected in human sera are not related to the brucellosis. However, the antibodies to CβG were raised after immunization by BSA-conjugate of penta-β-(1→2)-d-glucoside and allowed detection of CβG, which opens a way towards the development of the new brucellosis diagnostic kit.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Brucellosis is a bacterial disease caused by Brucella species. This infection afflicts humans as well as wild and domestic animals (cattle, sheep etc.) widely across the globe1,2,3,4. Modern veterinary standards for the eradication of brucellosis in livestock require the culling of infected animals, which has a crucial impact on the economics2,5,6. The increasing incidence of this infection and the expansion of endemic areas make the prevention of brucellosis a significant challenge. The effective prevention of infection requires specific and sensitive diagnostic tools. Nowadays, laboratory diagnosis of brucellosis is based on three different approaches: (1) direct bacteriological isolation and culturing7, (2) serological and immunological assays8, including allergic testing9, and (3) various molecular approaches based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques10. Despite the accumulation of experience in the application of these tests, certain limitations persist across all test types11. For serological detection, the O-chain of Brucella LPS is often utilized12. It consists of 4-N-formamido-4,6-dideoxy-d-mannose (“perosamine”) residues connected via α-(1→2) or α-(1→3)-glycoside linkages. The use of the O-chain for the design of human and animal brucellosis diagnostics is complicated by several factors which include (1) low preparative availability of the Brucella O-chain and complexity of its purification; (2) problems of distinguishing between vaccinated and infected animals; (3) serological cross-reactivity with Yersinia enterocolitica O:9, Vibrio cholera, Escherichia hermannii, and E. coli O15713,14,15,16. The latter is due to the similarity of the Brucella O-chain to polysaccharides expressed on the cell walls of the above species.

However, there is another carbohydrate derivative expressed by Brucella in a relatively large amount (1–5% of the dry weight of bacteria17), which is known as cyclic β-(1→2)-d-glucan (CβG) or Polysaccharide B. This is a macrocycle consisting of 17–25 d-glucose units linked by β-(1→2) glycoside bonds (Fig. 1A)18,19. Such a type of cyclic glucans is also produced by a non-virulent to mammals bacteria Rhizobium spp. and Agrobacterium spp.20,21,22, but there is no evidence of CβG appearance in Y. enterocolitica O:9, V. cholera, E. hermannii or E. coli. Controversial opinions regarding the potential use of CβG in brucellosis diagnosis were reported. In the early 1980s, polysaccharide B was considered an alternative serological marker that could differentiate between infected and vaccinated cattle23,24. But in 1988, Bundle et al. concluded that CβG cannot be used as a marker for brucellosis and supposed that the previously reported antigenic and serological activity of CβG was due to its contamination with Brucella O-chains18. Although Brucella CβG is considered, as non-immunogenic25, in 2022, Gildersleeve et al. discovered antibodies in humans that specifically recognized tetra-β-(1→2)-d-glucoside as the coating antigen26. Since chemically synthesized spacered β-(1→2)-d-gluco-oligosaccharides are not available, this antigen could possibly be obtained by partial acidic depolymerization of the CβG27. To date, only the syntheses of sophorose (β-Glc-(1→2)-β-Glc)28 and saponins containing di-29 and trisaccharide30 β-(1→2)-oligoglucoside moieties have been reported.

The immunological properties of CβG were not investigated in detail20,31,32,33,34,35,36. Surprisingly, this polysaccharide combines the lack of endotoxicity and immunogenicity with the ability to activate pro- and anti-inflammatory pathways17. Thus, CβG plays a fundamental and critically important role in the intracellular survival of Brucella by fine-tuning in some way the host’s immune response. Such a controversy in the literature over the past decades has stimulated us to further investigate the CβG.

Taking into account that synthetic oligosaccharides, which mimic fragments of a natural polysaccharide, are powerful tools for a variety of interdisciplinary studies37,38,39,40,41, we performed the first synthesis of spacered di-, tri-, tetra-, and penta-β-(1→2)-d-glucosides 1–4 (Fig. 1B) and demonstrated their applicability in conformational and immunochemical investigations of Brucella CβG. Herein we communicate the results of these studies.

Results and discussion

Synthesis of spacered oligoglucosides 1–4 related to linear fragments of CβG

The synthesis of target oligoglucosides 1–4 was performed using acetimidates 9 and 10 as key building blocks (Scheme 1). These glycosyl donors bear an acetyl group at O2, which has a dual function, being a participating group in stereoselective 1,2-trans-glycosylation and a temporary protecting group for further chain elongation. Thus, the synthesis of compounds 9 and 10 was started from d-glucose 5, which was first converted into orthoester 6 via peracetylation, bromination, and intramolecular 1,2-O-cyclization of orthoester. Classical conditions for this process typically require sterically hindered pyridines (such as sym-collidine or 2,6-lutidine), which leads to further laborious chromatographic separation of the acid-labile orthoester product from the reaction mixture. To facilitate purification, we used anhydrous Na2CO342 as a more convenient base that provided orthoester 6 in a 72% yield starting from glucose.

Orthoester 6 was then deacetylated and benzylated, resulting in tri-O-benzylated orthoester 7. Then, monosaccharide 7 was treated with a catalytic amount of TFA in an acetone-water mixture that led to the regioselective opening of the orthoester ring and the formation of 2-O-acetylated glucose derivative 8а, which was purified by recrystallization. Interestingly, changing the solvent from aqueous acetone to CH2Cl2 led to a loss of regioselectivity of orthoester opening and the formation of a mixture of 1-O-acetylated (8b) and 2-O-acetylated (8a) isomers. Nevertheless, the resulting mixture of isomers was acetylated, leading to single diacetate 8c, which was then converted into target hemiacetal 8a via regioselective deacetylation with hydrazine acetate.

The synthetic scheme described above was applied for the multigram (up to 25 grams) synthesis of hemiacetal 8 from glucose, using only two flash-chromatography procedures and one recrystallization for purification. The imidation of hemiacetal 8а yielded key glycosyl donors: trichloroacetimidate 9 and usually used for complicated glycosylation N-(phenyl)-trifluoroacetimidate derivative 1043.

Spacered glycosyl acceptor 13 was obtained by TMSOTf-promoted glycosylation of N-Cbz-protected 3-aminopropanol 11 with trichloroacetimidate 9 followed by deacetylation. Coupling of glycosyl acceptor 13 and glycosyl donor 9 under TMSOTF promotion in CH2Cl2 gave disaccharide 14 in a good yield of 85% and excellent β-selectivity (Scheme 2). Its deacetylation resulted in the formation of disaccharide acceptor 15 that was subjected to further glycosylation with donor 9 under the same conditions to afford trisaccharide 16 in a moderate yield of 68%.

To continue chain elongation, compound 16 was converted into trisaccharide acceptor 17 and glycosylated with donor 10, but unfortunately, the desired tetrasaccharide 18 was obtained only in a poor yield of 22%. Nevertheless, an attempt to reach the pentasaccharide was undertaken, but the deacetylation conditions previously used for shorter oligosaccharides 14 and 16 appeared ineffective for tetrasaccharide 18. Complete deacetylation of compound 18 could not be achieved under standard conditions (Zemplen, K2CO3, MeOH, CH2Cl2), therefore, harsh conditions were tested. Treatment of acetate 18 with NaOH in a refluxing ethanol-dichloroethane-water mixture for 3 days or with DIBAL-H in toluene44,45,46 at low temperature for 10 min led to good yields of deacetylation (Scheme 2). However, tetrasaccharide acceptor 19 obtained with such difficulties did not react with donor 10 under standard glycosylation conditions, and no traces of desired pentasaccharide 20 were detected in the reaction mixture.

The relatively easier deacetylation of 18 in toluene suggested the possibility of a more efficient glycosylation using this solvent as a medium. Moreover, the benefits of using toluene as a solvent for glycosylations have been recently reported47. Indeed, the change of the commonly used CH2Cl2 to toluene in glycosylation reactions resulted in a drastic increase in the yield of tetrasaccharide 18, from 22% in CH2Cl2 to 90% in toluene (Table 1). Pentasaccharide 20, which could not be obtained in CH2Cl2, was produced in toluene with a yield of 35%.

Total deprotection of oligosaccharides 14, 16, 18, and 20 included catalytic hydrogenolysis of O-benzyl and N-benzyloxycarbonyl groups and subsequent alkaline hydrolysis of the acetyl group to produce target glycosides 1–4 (Scheme 2).

NMR studies of oligoglucosides 1–4 related to CβG

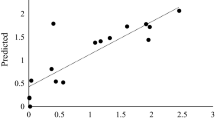

Complete assignment of the 1H and 13C signals in NMR spectra (see Fig. 2, and Tables S10.1 and S10.2 in SI) of target model oligosaccharides 1–4 was performed applying 2D NMR experiments 1H–1H-COSY, 1H–13C-HSQC, 1H–1H-ROESY, 1H–1H-NOESY, 1H–1H-TOCSY and 1H–13C-HMBC. Comparison of the NMR spectra of synthesized β-(1→2)-oligoglucosides 1–4 revealed unusually complex dependencies of the 13C chemical shifts from the chain length. In the case of the β-(1→2)-oligoglucosides, the addition of each subsequent residue to the oligosaccharide chain significantly altered the 13C chemical shifts of all the residues within the chain. For example, in the rows of C-2 or C-4 chemical shifts of the reducing residue in di- (1), tri- (2), tetra- (3), and pentasaccharide (4) the range of changes reached 2.0 ppm (Fig. 2B). This permitted to expect remarkable changes of 3D shape of oligosaccharide sequences influenced by the chain elongation. This property distinguished β-(1→2)-oligoglucosides from usual oligosaccharide homologs, for example oligogalactofuranosides related to fragments of Aspergillus galactomannan48 or oligoglucosides related to fungal β-(1→3)-glucan49, when the 13C chemical shifts of the constituent monosaccharides are influenced only by the monosaccharide units, that are directly connected to the considered residue. The influence of distant residues for this type of oligosaccharide was estimated to be <0.2 ppm48.

A The 13C NMR spectra of synthetic oligosaccharides 1–4 and the Brucella CβG (full view). B The dependence of the C-2 and C-4 chemical shifts of reducing residues on the chain length for β-(1→2)-oligoglucosides 1–4. C Comparison of 13C NMR spectra for oligosaccharides 1–4 and CβG (zooming the C-1, C-2, and C-4 regions).

Oligosaccharides 1–4 were compared to the natural Brucella CβG polysaccharide using 13C NMR spectroscopy. The results showed that only the inner bond between the second and the third residues of pentasaccharide 4 (residues B and C in Fig. 2) matched well the signals in the natural CβG polysaccharide. Thus, the C-1 shift of residue C (δ = 101.99) and C-2 signal of residue B (δ = 82.45) were almost identical to those in the natural CβG (δ = 102.02 and δ = 82.45, respectively). The signals of C-4 in both residues B and C also matched the corresponding signals in the natural CβG (Fig. 2C). These data allowed us to conclude that only pentasaccharide 4 could be regarded as the minimal size model mimicking CβG.

It is well known that the chemical shifts of the 13C atoms near the inter-residual bond reflect the conformational state of the glycosidic linkages50,51. Thus, the previously described heterogeneity of 13C NMR signals for natural CβG was explained by conformational nonequivalence of the glycoside bonds within the carbohydrate chain18. To explore this hypothesis, molecular modeling was performed using molecular dynamics simulations (for details, see SI section 8, initial and final atomic coordinates in molecular dynamics simulations are provided in Supplementary Data 1). The selection of MM3 forcefield in explicit water was justified based on a previous comparative study52 demonstrating its optimal balance of accuracy, computational efficiency, and broad compatibility. Prior to modeling the natural macrocycle, we validated our chosen computational methodology with simpler models: disaccharide 1 and trisaccharide 2. The φ/ψ conformational map obtained for disaccharide 1 has shown good compatibility with previously reported53 X-ray diffraction data for sophorose (β-Glc-(1→2)-Glc, CSD reference codes SOPHROS), as well as with previously implemented54 conformational analyses (Fig. 3A). Similarly, for trisaccharide 2, the results were consistent with earlier conformational studies55, confirming the distinct conformational behavior of the two glycosidic linkages within trisaccharide 2 and indicating the spatial proximity of the terminal residues (Fig. 3B). Notably, both the present study and the previous work55 identified a significant population of conformers in the β-(1→2)-linked trisaccharide with a hydrogen bond between the 3-OH group of the reducing residue and the endocyclic O-5 atom of the non-reducing terminal residue (see Fig. 3D). Comparison of geometric parameters for β-(1→2)-linked di- and trisaccharides is presented in SI (see Table S8.1). The conformational map of the torsional angles (φ, ψ) of the glycosidic linkages in the cyclic β-(1→2)-glucan with 24 glucose units demonstrated significant heterogeneity where multiple centers could be determined (Fig. 3C). The analysis of the carbohydrate chain geometry revealed the presence of helical shapes containing four units (Fig. 3D, shape II), with spatial proximity of the terminal residues (N and N + 3 proximity). Another detected form of the chain (Fig. 3D, shape I) was a fragment where units separated by one residue are in close proximity (N and N + 2 proximity). The tendency to form helical secondary structures explains the NMR effects from distant residues (across one and across two residues) and may be connected with the dramatic decrease in glycosylation yields upon chain elongation. The same can be suggested as an explanation of the unusual dependency of 13C NMR chemical shifts for oligosaccharides 1–4. To the best of our knowledge, the few examples of a homooligosaccharide chain with similar properties are β-(1→2)-oligomannans56,57 and cyclic β-(1→6)-glucosamines58,59.

Immunochemical investigations of oligoglucosides 1–4 related to CβG

Immunochemical studies require the preparation of glycoconjugates with various tags and polymer carriers as coating antigens and immunogens. The presence of an aminopropyl spacer in the structure of oligosaccharides 1–4 enables site-specific conjugation and the production of all necessary molecular probes. Thus, the biotin tag was connected to oligoglucosides 1–4 through a flexible hydrophilic linker by the reaction with active ester C6F5O–Biot60 to produce derivatives 21–24 (Scheme 3A). A biotinylated derivative of the native CβG (CβG-biot) was prepared by treatment of CβG with C6F5O–Biot in anhydrous DMSO in presence of DIPEA and DMAP, and biotinylation was confirmed using HRMS (for details see SI, section 3.4).

A conjugate of pentasaccharide 4 with polyacrylamide (PAA) 4-PAA was obtained by condensation of poly(p-nitrophenyl acrylate)61 with 20 molar % of glycoside 4 followed by neutralization of remaining active ester groups with n-butylamine and ethanolamine (Scheme 3B). Conjugation of 4 with BSA (Scheme 3C) was carried out with the use of the squarate procedure62 to give neoglycoconjugate 4-BSA. According to MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, conjugate 4-BSA contained on average 16–17 copies of the pentasaccharide.

Antibodies specific to β-(1→2)-oligoglucosides were detected in human sera26 but up to now their natural antigen as well as their physiological role have not been established. Herein, we investigated the possible association of these antibodies with Brucella infection, where CβG could play a role of the natural antigen. For this purpose, an ELISA screening of human donor sera was conducted using glycoconjugate 4-PAA as a coating antigen. Three groups of human donors were involved: (1) donors with yersiniosis (N = 11); (2) donors with other infections (viral respiratory infections, N = 7); (3) donors with brucellosis (N = 29) (Fig. 4A).

A ELISA screening of human donor’s sera from three groups: donors with yersiniosis (N = 11), brucellosis (N = 29) and other infections (N = 7) using 4-PAA as the coating antigen revealed 5 sera positive samples (Y1, Y2, O1, O2, B1). B ELISA profiling of 5 selected sera samples (Y1, Y2, O1, O2, and B1) on an array of biotinylated di-, tri-, tetra-, and pentssaccharides 21–24 revealed Kabat and non-Kabat types of dependency. C Scheme of rabbit immunization by conjugate of pentasaccharide 4 with BSA (4-BSA). D ELISA profiling of rabbit blood sera antibodies after immunization with 4-BSA on the array of oligosaccharides 21–24. E Determination of antibodies in rabbit blood sera to CβG after immunization with conjugate 4-BSA. F Detection of soluble CβG in inhibition assay using CβG-biot immobilized on the surface of a streptavidin microtiter plate.

Sera positive samples were present in all groups, but no significant differences were observed between the studied cohorts (for numerical source data for all graphs and charts, see Supplementary Data 2). The five sera samples with the highest antibody level (A(450) > 0.7) were selected for further investigation of IgG epitope specificity. Thus, two samples from donors with yersiniosis (Y1 and Y2); 2 samples from donors with other infections (O1 and O2) and one sample from a donor with brucellosis (B1) were profiled using an array of biotinylated oligosaccharides 21–24 (Fig. 4B). A biotinylated β-d-glucoside was used as a negative control and is labeled as (−). Surprisingly, it was found that the detected antibodies most effectively bound the shortest β-(1→2)-linked disaccharide 21.

The dramatic difference in the spectral NMR and spatial properties of disaccharide 21 and the native CβG, as well as the lack of a significant increase in antibody levels in brucellosis patients, led us to the conclusion that the observed antibodies are not related to the Brucella CβG. On the other hand, the β-(1→2)-linked diglucoside fragment is found in the polysaccharide antigens of various pathogenic and non-pathogenic bacteria, for example, Shigella flexneri, Streptococcus pneumonia type 37 or Lactobacillus plantarum63,64,65. Thus, the reported antibodies may have a wide range of microbial specificity and play an important role in the immune system.

Of additional interest is the unique length dependence of antigenic properties of the described β-(1→2)-oligoglucosides. The interaction of antibodies with homooligosaccharides typically follows the Kabat principle66. According to it, the interaction with antibodies increases gradually and then reaches a plateau with the elongation of the antigenic chain. However, this type of dependence was observed only for sample B1 (Fig. 4B).

For the other positive sera samples (Y1, Y2, O1, O2), a different (non-Kabat) type of dependence with local minima and maxima was obtained. This observation additionally confirms the formation of helical structures discussed above (see Fig. 3), leading to a drastic change in the geometry of the epitope upon addition of each subsequent monosaccharide residue.

The lack of immunogenicity makes it challenging to generate antibodies that recognize the Brucella CβG. Indeed, T-dependent immunity and IgG formation are not possible in response to a low molecular weight (~3–4 kDa) carbohydrate molecule that does not contain a protein or lipid moiety. On the other hand, synthetic oligosaccharides that mimic the chain of a natural CβG may be useful for the production of anti-CβG IgG. To demonstrate this principle, rabbits were immunized (Fig. 4C) with a BSA conjugate of pentasaccharide 4, which is a minimal size fragment that mimics CβG (see Fig. 2). After two immunizations, antibodies to tri-(22), tetra-(23), and pentasaccharides (24), but not against disaccharide (21), were raised (Fig. 4D).

The ability of the obtained antiserum to recognize natural CβG was demonstrated by ELISA with the use of immobilized CβG-biotin on the surface of streptavidin-coated plate. Rabbit serum collected at day 28 showed the ability to bind to surface-fixed CβG (Fig. 4E). The plate surface without pre-immobilized CβG-biotin served as a negative control and did not show any interaction. The binding of antibodies with dissolved CβG was dose-dependent, which was confirmed in the inhibitory assay (Fig. 4F).

Thus, using an immunogen based on oligosaccharide mimetic 4, antibodies were obtained that were specific to the natural CβG and could be used for detection of soluble CβG. Taking into account that CβG is expressed in large amounts (when bacteria are killed by the host immune system, CβG is released into the environment in mM concentration17) the detection of CβG can be considered as a new promising option for the diagnosis of brucellosis.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the first synthesis of β-(1→2)-oligoglucosides 1–4, structurally related to Brucella macrocyclic CβG was performed. CβG represents the great interest due to its unique immunological activity and potential as a marker of brucellosis. Despite the apparent simplicity of the synthesis, unexpected complications were encountered during the preparation of the target compounds. To overcome them, optimization of glycosylation conditions was performed, including a careful choice of solvent, which finally led to a remarkable increase in the yields of the desired products.

The molecular modeling predicted a tendency for the β-(1→2)-gluco-chains to form helical structures, which could be a key for understanding the cause of unusual chemical, spectral (13C NMR) and antigenic properties of β-(1→2)-oligoglucosides 1–4. Such behavior might also be a source of the mentioned synthetic difficulties.

Application of synthesized oligosaccharides 1–4 and conjugates thereof allowed establishing CβG-independent origin of anti-β-(1→2)-glucan IgGs detected in the sera of human donors. In addition, using pentasaccharide 4 as a minimal model of the CβG led to the raising of anti-CβG antibodies, which could not be obtained using the immunogen based on CβG. The applicability of these antibodies for the detection of soluble CβG produced by bacteria was demonstrated. Its high concentration in bacterial cells opens possibilities for the development of new diagnostic tools for brucellosis detection.

Methods

General method for glycosylation

A mixture of glucosyl-acceptor (1 eq) and glucosyl-donor 5 or 6 (0.75-1.4 eq) was coevaporated with toluene, and dried under reduced pressure. The mixture was dissolved in dry CH2Cl2 or dry toluene, and freshly activated molecular sieves 4 Å (0.1 g per 1 ml) were added. After 30 min the mixture was cooled to −50 °C and TMSOTf (0.3 eq) was added. After 30 min, the reaction was stopped by the addition of Et3N (15 μl), then filtered through silica gel. Filtrate was washed with EtOAc. All obtained compounds were purified by column chromatography.

General method for deacetylation

To a solution of acetylated compounds (0.1 М) in a mixture of CH2Cl2 and MeOH (1:1 v/v), K2CO3 (5 eq) was added, and the mixture was left under stirring. After full conversion of acetylated compound, reaction mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 and washed with aq. sat. NH4Cl. The organic phase was dried by filtration through Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. All obtained compounds were purified by column chromatography.

Synthesis of compound 15

Desacetylation with NaOH

Monoacetate 14 (251.4 mg, 0.126 mmol) was dissolved in DCE (500 μl) and EtOH (500 μl), and NaOH (50.4 mg, 1.26 mmol) was added. The mixture was left under reflux for 3 days. Then reaction mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2, organic phase was washed with aq. sat. NH4Cl. The organic phase was dried by filtration through Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. Reaction mixture was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel (PE/Tol/EA 1:1:1), giving alcohol 15 as a white foam (218.8 mg, 90%).

Desacetylation with DIBAL-H

Monoacetate 14 (27.8 mg, 0.0140 mmol) was dissolved in dry toluene (200 μl), and the mixture was cooled to −78 °C. DIBAL-H solution (50 μl, 1 М in toluene) was added. After 30 min aq. sat. NH4Cl was added, then the mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2. The organic phase was dried by filtration through Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. Reaction mixture was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel (PE/Tol/EA 1:1:1), giving alcohol 15 as a white foam (22.1 mg, 81%).

Desacetylation with Bu4NOH

Monoacetate 14 (62.1 mg, 0.0313 mmol) was dissolved in THF (200 μl) and MeOH (100 μl) and aq. Bu4NOH (100 μl, 40% by weight) was added. The mixture was left under reflux for 7 days. Conversion of monoacetate was 0% by NMR.

General method for deprotection of oligosaccharides

Fully protected oligosaccharides (10, 12, 14, 16) were dissolved in THF/H2O (800 μl:200 μl) and AcOH (20 μl) was added. Pd(OH)2/C was added, and the flask volume was degassed by a water jet pump, then the flask was filled with H2. Reaction mixture was left under stirring overnight. The mixture was filtered through a nylon filter, then the mixture was evaporated. The residue was dissolved in 500 μl of H2O and NaOH (7.5 eq) was added. After desacetylation completion, the reaction was neutralized with 0.1 М aq. AcOH, then concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by size-exclusion chromatography (TSK HW-40 (S), 0.1 M AcOH) to give target oligosaccharides.

Synthesis of biotinylated oligosaccharides

To a solution of aminopropyl glycoside and Et3N (15 μl) in DMF (150 μl) then solution of biotin-activated ester in DMF (1.2 eq., 62 μmol per ml) was added. After 30 min the mixture was purified by size exclusive chromatography (TSK HW-40 (S), 0.1 M AcOH) to give target oligosaccharides.

Polyacrylamide conjugate of pentasaccharide

Aminopropyl pentaglucoside 4 (1076 μg, 1.216 μmol) was dissolved in DMF (200 μl) and Et3N (2.5 μl). p-Nitrophenyl polyacrylate (1162 μg, 6.08 μmol p-nitrophenyl residues) in DMF (100 μl) was added at 37 °C. After 2 h n-BuNH2 (0.24 μl, 2.43 μmol) was added to the reaction mixture. After another 2 h ethanolamine (20 μl) was added and the reaction was left. The mixture was concentrated in vacuo, conjugate was purified by size-exclusive chromatography on LH-20 gel, eluting with MeCN/H2O 1:1. The product was obtained as beige foam (1.46 mg).

BSA conjugate of pentasaccharide

To a solution of pentasaccharide 4 (2.37 mg, 2.68 μmol) in EtOH:H2O (1:1 v/v, 250 μl) diethyl squarate (0.59 μl, 4.02 μmol) and Et3N (0.74 μl, 5.36 μmol) were added. After 30 min the reaction mixture was evaporated, the residue was purified by column chromatography on SepPak C18 cartridge with MeOH:H2O (0%→60% MeOH v/v, 2 ml portions with steps of 5%). Fractions of 25 were evaporated and lyophilized, obtaining 2.04 mg, yield: 72%.

Solution of bovine serum albumin (BSA) (6.51 mg) in 150 μl of 0.2М borate buffer (pH = 9.0). were added to the lyophilizate of 24. The mixture was left for a day, then conjugate was purified on Sephadex G-15 column in H2O. Protein fractions were lyophilized, resulting in pure conjugate 4-BSA (7.7 mg) with 16–17 residues of pentasaccharide attached to one molecule of BSA (MALDI-TOF MS).

Biotinylated CβG

To a solution of CβG (0.2 mg) in DMSO (50 μl) DIPEA (3 μl) and DMAP (cat.) were added. Solution of activated ester of biotin in DMF (4.74 μl, 62 мМ) was added. After 4 days 150 μl MeCN, 800 μl EtOAc and 7 μl H2O were added, then the mixture was centrifuged and the solvents were removed. Dry residue was dissolved in H2O and lyophilized. Conjugate was purified by column chromatography on SepPak C18 cartrige with MeOH:H2O (0%→80% MeOH v/v, 0.5 ml portions with steps of 5%). Fractions of the conjugate were lyophilized. MS of the obtained conjugate is attached in SI section 11.

Ethics statement

The studies involving animals and humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Moscow Infectious Clinical Hospital №1 of the Moscow Department of Healthcare on 17 December 2023 (Protocol No. 11 of 12/17/2023). All of the experimental procedures involving human blood sera were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the National Committee on Research Ethics (Russia) and the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and its subsequent changes or comparable ethical principles. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Human donor serum screening

Polyacrylamide conjugate 4-PAA was absorbed on the wells of polystyrene plates (Xema, Russia) (100 µL of a 2 μg/mL solution in PBS) for 24 h at 4 °С. Subsequently, the wells were washed with PBS one time and blocked with 1% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) for 1 h at 37°С. After shaking out and drying, the plates were ready to use. Human donors sera (d200) was added to the wells. After that plates were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C, then washed three times. The wells were treated with conjugates of anti-human IgG Ab with peroxidase (d10000; IMTEK, Russia) and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. The plates were washed five times, and color was developed using 100 µL of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) monocomponent substrate (Xema, Russia) for 15 min. The reaction was stopped with 50 µL of 1 M sulfuric acid. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a Multiskan GO plate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States). All measurements were repeated independently and performed twice.

Profiling experiments

Solutions of conjugates 21–24 in wash buffer (PBS, pH = 7.4, 0.1% BSA, 0.05% Tween-20) (0.2 μM, 100 μl per well) were added to the PierceTM Streptavidin-coated clear strip plate with SuperBlockTM blocking buffer and incubated for 1.5 h at 37 °C. After incubation plates were washed three times. Human donors sera (d200, d600, d1800) were added to the wells. After that plates were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C, then washed three times. The wells were treated with conjugates of anti-human IgG Ab with peroxidase (d10000; IMTEK, Russia) and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. The plates were washed five times, and color was developed using 100 µL of TMB monocomponent substrate (Xema, Russia) for 15 min. The reaction was stopped with 50 µL of 1 M sulfuric acid. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a Multiskan GO plate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States). All measurements were repeated independently and performed twice in triplicate.

Profiling of antibodies in rabbit blood sera

Solutions of conjugates 21–24 in wash buffer (PBS, pH = 7.4, 0.1% BSA, 0.05% Tween-20) (0.2 μM, 100 μl per well) and biotinylated CβG (1 μg/ml) were added to the PierceTM Streptavidin-coated clear strip plate with SuperBlockTM blocking buffer and incubated for 1.5 h at 37 °C, then washed three times. Rabbit’s blood sera before and after immunization (d150) were added to the wells, and the plates were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C, then washed three times. The wells were treated with conjugates of anti-rabbit IgG Ab with peroxidase (d10000; IMTEK, Russia) and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. The plates were washed five times, and color was developed using 100 µL of TMB monocomponent substrate (Xema, Russia) for 15 min. The reaction was stopped with 50 µL of 1 M sulfuric acid. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a Multiskan GO plate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States). All measurements were repeated independently and performed twice in triplicate.

Inhibition assay for the detection of CβG in a solution

Solution of biotinylated CβG (1 μg/ml) was added to the PierceTM Streptavidin-coated clear strip plate with SuperBlockTM blocking buffer and was incubated for 1.5 h at 37 °C, then washed three times. To the wells of the strip plate rabbit’s blood sera after immunization (d200) in wash buffer was added, and to some wells the solution of CβG (inhibitor) was added to the concentrations of 100,000, 20,000, 4000, 800, 160 ng/ml, and the plates were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C, then washed three times. The wells were treated with conjugates of anti-rabbit IgG Ab with peroxidase (d10000; IMTEK, Russia) and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. The plates were washed five times, and color was developed using 100 µL of TMB monocomponent substrate (Xema, Russia) for 15 min. The reaction was stopped with 50 µL of 1 M sulfuric acid. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a Multiskan GO plate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States). All measurements were repeated independently and performed twice in triplicate.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files.

References

Laine, C. G., Johnson, V. E., Scott, H. M. & Arenas-Gamboa, A. M. Global estimate of human brucellosis incidence. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 29, 1789–1797 (2023).

Franc, K. A., Krecek, R. C., Häsler, B. N. & Arenas-Gamboa, A. M. Brucellosis remains a neglected disease in the developing world: a call for interdisciplinary action. BMC Public Health 18, 125 (2018).

Pappas, G., Papadimitriou, P., Akritidis, N., Christou, L. & Tsianos, E. V. The new global map of human brucellosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 6, 91–99 (2006).

Ponomarenko, D. G. et al. Overview of epizootological and epidemiological situation on brucellosis in the Russian Federation in 2017 and Prognosis for 2018. Probl. Part. Danger. Infect. 23–29 (2018).

Khurana, S. K. et al. Bovine brucellosis – a comprehensive review. Vet. Q. 41, 61–88 (2021).

Larson, J. W. Brucellosis in cattle - reproductive system. Merck Veterinary Manual https://www.merckvetmanual.com/reproductive-system/brucellosis-in-large-animals/brucellosis-in-cattle (2023).

Di Bonaventura, G., Angeletti, S., Ianni, A., Petitti, T. & Gherardi, G. Microbiological laboratory diagnosis of human brucellosis: an overview. Pathogens 10, 1623 (2021).

Ruiz-Mesa, J. D. et al. Rose Bengal test: diagnostic yield and use for the rapid diagnosis of human brucellosis in emergency departments in endemic areas. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 11, 221–225 (2005).

Ponomarenko, D. G. et al. A new approach to the allergodiagnosis of brucellosis. Russ. J. Infect. Immun. 3, 89–92 (2013).

Mitka, S., Anetakis, C., Souliou, E., Diza, E. & Kansouzidou, A. Evaluation of different PCR assays for early detection of acute and relapsing brucellosis in humans in comparison with conventional methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45, 1211–1218 (2007).

Yagupsky, P., Morata, P. & Colmenero, J. D. Laboratory diagnosis of human brucellosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 33, https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.00073-19 (2019).

McGiven, J. et al. Improved serodiagnosis of bovine brucellosis by novel synthetic oligosaccharide antigens representing the capping M epitope elements of brucella o-polysaccharide. J. Clin. Microbiol. 53, 1204–1210 (2015).

Caroff, M., Bundle, D. R., Perry, M. B., Cherwonogrodzky, J. W. & Duncan, J. R. Antigenic S-type lipopolysaccharide of Brucella abortus 1119-3. Infect. Immun. 46, 384–388 (1984).

Perry, M. B. & Bundle, D. R. Antigenic relationships of the lipopolysaccharides of Escherichia hermannii strains with those of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Brucella melitensis, and Brucella abortus. Infect. Immun. 58, 1391–1395 (1990).

Zygmunt, M. S., Dubray, G., Bundle, D. R. & Perry, M. P. Purified native haptens of Brucella abortus B19 and B. melitensis 16M reveal the lipopolysaccharide origin of the antigens. In: Annales de l’Institut Pasteur/Microbiologie vol. 139, 421–433 (Elsevier, 1988).

Smirnova, E. A. et al. Current methods of human and animal brucellosis diagnostics. Adv. Infect. Dis. 03, 177–184 (2013).

Degos, C., Gagnaire, A., Banchereau, R., Moriyón, I. & Gorvel, J.-P. Brucella CβG induces a dual pro- and anti-inflammatory response leading to a transient neutrophil recruitment. Virulence 6, 19–28 (2015).

Bundle, D. R., Cherwonogrodzky, J. W. & Perry, M. B. Characterization of Brucella polysaccharide B. Infect. Immun. 56, 1101–1106 (1988).

Garozzo, D. et al. Quantitative determination of β(1–2) cyclic glucans by matrix‐assisted laser desorption mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 8, 358–360 (1994).

Dylan, T., Helinski, D. R. & Ditta, G. S. Hypoosmotic adaptation in Rhizobium meliloti requires β-(1→2)-glucan. J. Bacteriol. 172, 1400–1408 (1990).

Hisamatsu, M., Amemura, A., Koizumi, K., Utamura, T. & Okada, Y. Structural studies on cyclic (1→2)-β-D-glucans (cyclosophoraoses) produced by Agrobacterium and Rhizobium. Carbohydr. Res. 121, 31–40 (1983).

Puvanesarajah, V., Schell, F. M., Stacey, G., Douglas, C. J. & Nester, E. W. Role for 2-linked-β-D-glucan in the virulence of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Bacteriol. 164, 102–106 (1985).

Diaz, R., Toyos, J., Salvo, M. D. & Pardo, M. L. A simple method for the extraction of polysaccharide B from Brucella cells for use in the radial immunodiffusion test diagnosis of bovine brucellosis. Ann. Rech. Vet. 12, 35–39 (1981).

Jones, L. M. et al. Evaluation of a radial immunodiffusion test with polysaccharide B antigen for diagnosis of bovine brucellosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 12, 753–760 (1980).

Martirosyan, A. et al. Brucella β 1,2 cyclic glucan is an activator of human and mouse dendritic cells. PLOS Pathog. 8, e1002983 (2012).

Temme, J. S. et al. Microarray-guided evaluation of the frequency, B-cell origins, and selectivity of human glycan-binding antibodies reveals new insights and novel antibodies. J. Biol. Chem. 298, 102468 (2022).

Zhang, H. et al. Generation and characterization of β-1,2-gluco-oligosaccharide probes from Brucella abortus cyclic β-glucan and their recognition by C-type lectins of the immune system. Glycobiology 26, 1086–1096 (2016).

Coxon, B. & Fletcher, H. J. Jr. Simplified preparation of sophorose (2-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-D-glucose). J. Org. Chem. 26, 2892–2894 (1961).

Yang, F., Hou, W., Zhu, D., Tang, Y. & Yu, B. A stereoselective glycosylation approach to the construction of 1,2‐trans‐β‐D‐glycosidic linkages and convergent synthesis of saponins. Chem. Eur. J. 28, e202104002 (2022).

Du, Y., Wei, G. & Linhardt, R. J. Total synthesis of quercetin 3-sophorotrioside. J. Org. Chem. 69, 2206–2209 (2004).

Rigano, L. A. et al. Bacterial cyclic β-(1,2)-glucan acts in systemic suppression of plant immune responses. Plant Cell 19, 2077–2089 (2007).

Arellano-Reynoso, B. et al. Cyclic beta-1,2-glucan is a Brucella virulence factor required for intracellular survival. Nat. Immunol. 6, 618–625 (2005).

Roset, M. S. et al. Brucella cyclic β-1,2-glucan plays a critical role in the induction of splenomegaly in mice. PLoS ONE 9, e101279 (2014).

Haag, A. F., Myka, K. K., Arnold, M. F. F., Caro-Hernández, P. & Ferguson, G. P. Importance of lipopolysaccharide and cyclic β-1,2-glucans in Brucella-mammalian infections. Int. J. Microbiol. 2010, 124509 (2010).

Briones, G. et al. Brucella abortus cyclic β-1,2-glucan mutants have reduced virulence in mice and are defective in intracellular replication in HeLa cells. Infect. Immun. 69, 4528–4535 (2001).

Diaz, R., Garatea, P., Jones, L. M. & Moriyon, I. Radial immunodiffusion test with a Brucella polysaccharide antigen for differentiating infected from vaccinated cattle. J. Clin. Microbiol. 10, 37–41 (1979).

Del Bino, L. et al. Synthetic glycans to improve current glycoconjugate vaccines and fight antimicrobial resistance. Chem. Rev. 122, 15672–15716 (2022).

Krylov, V. B. & Nifantiev, N. E. Synthetic oligosaccharides mimicking fungal cell wall polysaccharides. In The Fungal Cell Wall (ed. Latgé, J.-P.) Vol. 425, 1–16 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2019).

Laverde, D. et al. Synthetic oligomers mimicking capsular polysaccharide diheteroglycan are potential vaccine candidates against encapsulated Enterococcal infections. ACS Infect. Dis. 6, 1816–1826 (2020).

Geissner, A. & Seeberger, P. H. Glycan arrays: from basic biochemical research to bioanalytical and biomedical applications. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 9, 223–247 (2016).

Horlacher, T. & Seeberger, P. H. Carbohydrate arrays as tools for research and diagnostics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 1414–1422 (2008).

Wei, S., Zhao, J. & Shao, H. A facile method for the preparation of sugar orthoesters promoted by anhydrous sodium bicarbonate. Can. J. Chem. 87, 1733–1737 (2009).

Yu, B. & Sun, J. Glycosylation with glycosyl N-phenyltrifluoroacetimidates (PTFAI) and a perspective of the future development of new glycosylation methods. Chem. Commun. 46, 4668–4679 (2010).

Hartmann, O. & Kalesse, M. The structure elucidation and total synthesis of β-lipomycin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 53, 7335–7338 (2014).

Lacharity, J. J. et al. Total synthesis of unsymmetrically oxidized nuphar thioalkaloids via copper-catalyzed thiolane assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 13272–13275 (2017).

Jana, S., Sarpe, V. A. & Kulkarni, S. S. Total synthesis and structure revision of a fungal glycolipid fusaroside. Org. Lett. 23, 1664–1668 (2021).

Usui, R., Koizumi, A., Nitta, K., Kuribara, T. & Totani, K. Multisite partial glycosylation approach for preparation of biologically relevant oligomannosyl branches contribute to lectin affinity analysis. J. Org. Chem. 88, 14357–14367 (2023).

Krylov, V. B. et al. Synthesis of oligosaccharides related to galactomannans from Aspergillus fumigatus and their NMR spectral data. Org. Biomol. Chem. 16, 1188–1199 (2018).

Gerbst, A. G. et al. Theoretical and experimental conformational studies of oligoglucosides structurally related to fragments of fungal cell wall β-(1→3)-D-Glucan. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 32, 205–221 (2013).

Bock, K., Brignole, A. & Sigurskjold, B. W. Conformational dependence of 13C nuclear magnetic resonance chemical shifts in oligosaccharides. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 1711–1713 (1986).

Gerbst, A. G., Grachev, A. A., Shashkov, A. S. & Nifantiev, N. E. Quantum mechanical calculation of 13C NMR chemical shifts in a series of isomeric fucobiosides with the account for conformational equilibrium. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 31, 93–104 (2012).

Stroylov, V., Panova, M. & Toukach, P. Comparison of methods for bulk automated simulation of glycosidic bond conformations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 7626 (2020).

Ohanessian, J., Longchambon, F. & Arene, F. Structure cristalline du sophorose [O-β-D-glucosyl-(1→2)-α-D-glucose]. Acta Crystallogr. B 34, 3666–3671 (1978).

Pereira, C. S. et al. Conformational and dynamical properties of disaccharides in water: a molecular dynamics study. Biophys. J. 90, 4337–4344 (2006).

Stortz, C. A. & Cerezo, A. S. mm3 Potential energy surfaces of the 2-linked glucosyl trisaccharides α-kojitriose and β-sophorotriose. Carbohydr. Res. 338, 1679–1689 (2003).

Johnson, M. A., Cartmell, J., Weisser, N. E., Woods, R. J. & Bundle, D. R. Molecular recognition of Candida albicans (1→2)-β-mannan oligosaccharides by a protective monoclonal antibody reveals the immunodominance of internal saccharide residues. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 18078–18090 (2012).

Nitz, M. & Bundle, D. R. The unique solution structure and immunochemistry of the Candida albicans β1, 2-mannopyranan cell wall antigen. In NMR Spectroscopy of Glycoconjugates 145–187. https://doi.org/10.1002/352760071X.ch7 (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2002).

Gening, M. L. et al. Synthesis, NMR, and Conformational Studies of Cyclic Oligo‐(1→6)‐β‐D‐Glucosamines. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 2465–2475 (2010).

Grachev, A. A. et al. NMR and conformational studies of linear and cyclic oligo-(1→ 6)-β-D-glucosamines. Carbohydr. Res. 346, 2499–2510 (2011).

Tsvetkov, Y. E. et al. Synthesis and molecular recognition studies of the HNK-1 trisaccharide and related oligosaccharides. The specificity of monoclonal anti-HNK-1 antibodies as assessed by surface plasmon resonance and STD NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 426–435 (2012).

Krylov, V. B. et al. ASCA-related antibodies in the blood sera of healthy donors and patients with colorectal cancer: characterization with oligosaccharides related to Saccharomyces cerevisiae mannan. Front. Mol. Biosci. 10, 1296828 (2023).

Karelin, A. A., Tsvetkov, Y. E., Kogan, G., Bystricky, S. & Nifantiev, N. E. Synthesis of oligosaccharide fragments of mannan from Candida albicans cell wall and their BSA conjugates. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 33, 110–121 (2007).

Sun, Q. et al. Dissemination and serotype modification potential of pSFxv_2, an O-antigen PEtN modification plasmid in Shigella flexneri. Glycobiology 24, 305–313 (2014).

Ayyash, M. et al. Characterization, bioactivities, and rheological properties of exopolysaccharide produced by novel probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum C70 isolated from camel milk. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 144, 938–946 (2020).

Llull, D., Garcı́a, E. & López, R. Tts, a processive β-glucosyltransferase of streptococcus pneumoniae, directs the synthesis of the branched type 37 capsular polysaccharide in pneumococcus and other gram-positive species. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 21053–21061 (2001).

Kabat, E. A. The upper limit for the size of the human antidextran combining Site1. J. Immunol. 84, 82–85 (1960).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (grant no. 19-73-30017-P). The authors thank Ms. A.I. Tokatly for reading this manuscript and its critical discussion, Dr. A.Y. Belyy for assistance with the preparation of graphic materials, Drs. A.O. Chizhov and A.S. Dmitrenok for recording HRMS and NMR spectra using the equipment in the Shared Research Center (Department of Structural Studies) of N.D. Zelinsky Institute of Organic Chemistry RAS, Moscow.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.E.T., O.A.B., Y.K.K., V.B.K. and N.E.N. conceived the project and designed the experiments. A.N.K., A.G.G., R.R.K. and A.A.D. performed the experiments. A.N.K., V.B.K. and N.E.N. interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. N.E.N. acquired funding. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Martin Smiesko and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuznetsov, A.N., Gerbst, A.G., Tsvetkov, Y.E. et al. Synthesis and immunochemical studies of linear oligoglucosides structurally related to the cyclic β-(1→2)-d-glucan of Brucella. Commun Chem 8, 172 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01570-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01570-7