Abstract

Aqueous nitrate (\({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\)) can be electrocatalytically reduced to value-added or benign products. However, the impact of the electrochemical potential on key reaction steps remains poorly understood. Using explicit and analytical grand-canonical density functional theory (eGC-DFT and aGC-DFT), we investigate the potential dependence of nitrate adsorption and dissociation on pure metals and Cu-based single-atom alloys (SAAs). With aGC-DFT, we find that the nitrate adsorption free energy on stable/metastable SAAs and pure metals varies linearly with the applied potential, indicated by constant slopes (electrosorption valencies) of −0.60 \(\frac{{{{\rm{eV}}}}}{{{{\rm{V}}}}}\) to −0.80 \(\frac{{{{\rm{eV}}}}}{{{{\rm{V}}}}}\). The nitrate dissociation barrier exhibits weak, but linear potential dependencies across metals with slopes of −0.04 \(\frac{{{{\rm{eV}}}}}{{{{\rm{V}}}}}\) and −0.20 \(\frac{{{{\rm{eV}}}}}{{{{\rm{V}}}}}\). The potential dependence for both reaction steps correlates with the change in the surface normal dipole moment, resulting largely from partial charge transfer during adsorption or N-O bond cleavage during dissociation. We demonstrate aGC-DFT predicts potential-dependent adsorption and activation energies that can differ significantly from conventional approximations (e.g., the computational hydrogen electrode model). However, aGC-DFT computed energies and these differences vary with the assumed double-layer properties. This work clarifies potential-dependent nitrate adsorption and dissociation trends across SAAs and pure metals, emphasizing the need to account for electrochemical conditions in mechanistic studies of nitrate reduction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electrocatalytic nitrate reduction (ENR) is being widely studied because of its potential to convert nitrate (\({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\)) waste into value-added or benign products such as ammonia or dinitrogen1,2. ENR uses electricity to drive an electrocatalyst and reduce aqueous \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) through several proton-coupled-electron-transfer (PCET) steps2. Researchers have identified electrocatalysts that promote desired product formation, including pure transition metals and bimetallic alloys2. Promising electrocatalysts in terms of activity and selectivity to desirable products (e.g., ammonia) often include platinum group elements, such as palladium (Pd), platinum (Pt), and rhodium (Rh), as well as coinage metals, such as copper (Cu)3,4.

More recently, single atom alloys (SAAs), a class of catalysts in which one metal element is atomically dispersed in another metal host, have demonstrated improved performance over their pure metal and bimetallic alloy counterparts5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. SAAs can potentially have high activity, high selectivity, and low cost compared to other alloys and pure metals10,13,14,15,16,17. Particularly due to the low cost and abundance of Cu, there has been interest in Cu-based SAAs to promote electrochemical reactions such as ENR, including Ti1Cu, Ni1Cu, Nb1Cu, Pd1Cu and Au1Cu6,8,9,11,12,18. These SAAs promote strong \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) adsorption and subsequent reduction to both dinitrogen and ammonia.

Despite the application of SAA and pure metal electrocatalysts, the impact of the applied electrochemical potential on key ENR reaction steps is not well understood, as well as the influence of dilute alloying on the potential dependence. Thus far, most theoretical studies of ENR use canonical Density Functional Theory (DFT) modeling combined with simplified approaches to consider the effects of the applied electrochemical potential on reaction energetics3,18,19. The most common approach is the computational hydrogen electrode (CHE) model19. Within the CHE framework, the adsorption energy, calculated via canonical DFT, is shifted by the electrochemical potential of the transferred electrons19. Therefore, the assumed integer charge transfer directly determines the potential dependence of any PCET step. For example, writing \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) adsorption as full electron transfer reaction (eq. (1)), then the CHE model computes an electrosorption valency of −1.00 \(\frac{{{{\rm{eV}}}}}{{{{\rm{V}}}}}\) (i.e., the rate of change in \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) adsorption energy with the applied potential)19.

A major drawback of the CHE model is that it can only approximate the potential dependence of PCET reaction steps, limiting its application to a subset of reaction steps within ENR. For example, direct nitrate dissociation to nitrite (\({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }+* \to {{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{2}^{* }\) + O*) is generally considered to be potential-independent, as it does not involve a proton or electron transfer. Furthermore, the CHE model neglects the formation of counter-charge above an electrode, termed the Helmholtz Layer (used synonymously with electrochemical double layer (EDL) in this work)20,21,22. Consideration of the potential dependence of both PCET and non-PCET steps as well as EDL effects aligns closer to experimental ensembles and gives a more accurate description of reaction energetics in electrochemical reactions23,24.

Recently, Grand Canonical DFT (GC-DFT) calculations have been used to simulate constant potential reactions and EDL effects at the electrochemical interface through computing the grand free energy20,25,26,27,28. The grand free energy of a candidate structure (e.g., adsorbed nitrate), ΦG, is shown in eq. (2), where F is the Helmholtz free energy of the system, μe is the electrochemical potential of an electron, and Nexc is the number of excess electrons (net surface charge) to shift the system from its potential of zero charge (PZC) to the potential on the absolute scale, U.

An explicit GC-DFT method (eGC-DFT), such as that proposed by Sundararaman et al., computes ΦG directly by changing Nexc to converge μe to −eU29. Ions present within the implicit solvation model simulate a collection of counter-charge above the surface and maintain overall charge neutrality. Therefore, an eGC-DFT structure optimization accounts for structural changes under applied potentials by optimizing a system with some net surface charge.

Explicit GC-DFT methods have been used to simulate the potential dependence of CO adsorption, CO reduction, and anion adsorption, revealing appreciable EDL effects and potential dependencies30,31,32. Alsunni et al. also found that the explicit GC-DFT yields significantly different reaction pathways and computed energetics than the CHE model for CO2 reduction to CO33. To help design electrocatalysts that break adsorbate scaling relations, Gao et al. performed eGC-DFT calculations to simulate \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) reduction to ammonia over Cu(111) and Cu(100) at 0.0 V vs. the Reversible Hydrogen Electrode. However, besides the analysis by Gao et al., eGC-DFT calculations have scarcely been applied to study ENR. One limitation of eGC-DFT that hinders its more widespread use to reactions like ENR is the increased computational cost compared to canonical DFT when converging an additional self-consistent loop such that μe = −eU.

The higher computational cost of eGC-DFT can be circumvented by approximating ΦG using a second-order Taylor expansion of F around the PZC, as shown in eq. (3)26,34. Here, F(Nexc = 0) represents the ground-state free energy of the candidate structure at the PZC, Uχ. The second-order approximation, given in eq. (4), is derived by applying Janak’s Theorem, \({\left.\frac{\partial F}{\partial {N}_{{{{\rm{exc}}}}}}\right\vert }_{{N}_{{{{\rm{exc}}}}} = 0}=-e{U}_{\chi }\), along with the relation \({\left.\frac{{\partial }^{2}F}{\partial {N}_{{{{\rm{exc}}}}}^{2}}\right\vert }_{{N}_{{{{\rm{exc}}}}} = 0}=\frac{{e}^{2}}{{C}_{\chi }}\), where Cχ denotes the double-layer capacitance at the PZC35 and thermochemistry corrections are assumed to be potential independent. Additionally, F(Nexc = 0) is rewritten as the DFT-computed ground-state free energy of the system at the PZC with thermochemistry corrections, FDFT(Uχ). Using this approximation for F, the net surface charge can be determined by minimizing ΦG with respect to Nexc, as shown in eq. (5)34,35. Substituting eq. (5) into eqs. (2) and (4) results in a quadratic approximation of ΦG, given in eq. (6). Guo et al. utilized eq. (6) to model the potential dependence of ENR reaction mechanisms across different facets of Cu36. However, this approximation alone neglects electric field interactions present within the double layer.

Agrawal et al. parameterized Cχ using a parallel plate model and modified eq. (6) to account for such electric field interactions within the EDL37. As shown in eq. (7), this modification included dipole-field and induced-dipole field interactions parameterized through the surface normal dipole moment and the polarizability. In this model, Uχ and μχ represent the PZC and surface normal dipole moment of either a bare surface (χ = *) or a surface with adsorbates (χ = A*). However, the polarizability, αχ, represents just the adsorbate molecule (αA = αA* − α*). Other parameters include the solution permittivity, ε, the double layer thickness, d and the surface area, A. They also provided an accurate and convenient way to compute Uχ in a dielectric medium, as shown in eq. (8), where U0 is the PZC of the bare surface calculated in vacuum from the work function37.

Both ε and d introduce variability in GC-DFT computed grand free energies. The permittivity is determined by the dielectric constant at an interface, εr, through ε = εrε0, where ε0 is the vacuum permittivity. For water, εr can range between the values of bulk water (78.4) and near-vacuum values (1)38. As for d, the characteristic thickness of the EDL is typically indicated by the Debye-Hückel length, which depends on εr, the ionic bulk concentration and charge, and the temperature of the system39. For eGC-DFT calculations in JDFTx, which simulates the double layer using a Poisson-Boltzman distribution, the Debye-Hückel length and hence the characteristic EDL thickness is 3.0 Å for a 1 molar solution of Na+/F− (represented as point charges) at 298 K. However, aGC-DFT instead considers the double layer as a Helmholtz model with some fixed double-layer thickness, where d is typically assumed to be between 3.0 Å and 7.0 Å31,37,40.

Overall, this analytical GC-DFT approach, herein referred to as aGC-DFT, presents a computationally efficient method to approximate ΦG by optimizing the candidate structure at the PZC and then correcting the computed energy for EDL effects and applied potentials. Wong et al. demonstrated its efficacy in approximating potential-dependent activation energies of C-H, O-H, and OC-CO bond formations over Cu(111)31. The model maintained mean absolute errors (MAEs) between 0.03 and 0.06 eV compared to eGC-DFT calculations. Cui et al. also used the model to support their experimental findings that CO2 reduction has potential-dependent negative fractional reaction orders at high overpotentials with respect to CO partial pressure41.

Despite the recent widespread usage of GC-DFT applications in electrocatalysis, advanced analytical models such as eq. (7) have not been applied yet to study the potential dependence of electrochemical reactions in ENR. Furthermore, the lack of clarity regarding how different computational approaches (eGC-DFT, aGC-DFT, and CHE) diverge in their predicted energetics for ENR underscores the need for a systematic comparison. This is especially true given that GC-DFT methods are sensitive to the choice of parameters to represent the EDL, including ε and d31,42. Altogether, an analysis which outlines the applications of GC-DFT models to ENR reaction steps would provide insights into the potential-dependent reaction energetics of ENR and ultimately improve the reliability of computational predictions in ENR. Specifically, the results and methodology within this work can be used to build potential-dependent microkinetic models for ENR reaction mechanisms. These potential-dependent models can help identify active catalysts and aid experimental catalyst design, as previously shown for non-potential-dependent models3.

Herein, we use eGC-DFT and aGC-DFT to examine the potential dependence of key steps of ENR on Cu-based SAAs, and we compare these results against pure metals to evaluate the effects of dilute alloying. To ensure we study likely stable SAAs, we use eGC-DFT to compute the segregation and aggregation energetics of (111) facets for eight Cu-based SAAs at −0.114 and −0.714 V vs SHE. Pd1Cu is stable against surface segregation and aggregation across all conditions, while Ni1Cu, Ru1Cu, and Rh1Cu maintain positive or near-zero segregation energies with low to moderate aggregation energies in the presence of adsorbed hydrogen and nitrate. When studying \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) adsorption and dissociation over Cu(111), we find the analytical method approximates grand free energies comparable with the explicit method. Therefore, using this analytical method, we elucidate the potential dependence of \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) adsorption and dissociation over (111) and (100) facets of four SAAs and five pure metals. Our results demonstrate that the surface normal dipole moment change dictates the potential dependence for nitrate adsorption and dissociation for both pure metals and SAAs. These dipole moment changes result largely from either partial charge transfer from \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) to the surface during adsorption (which correlates with the fractional d-band filling of the metal) or N-O bond cleavage during dissociation. However, when the dielectric medium fails to effectively screen strong electric field interactions, the polarizability of the adsorbates can contribute significantly to the potential dependence of both reaction steps. We find that neglecting EDL effects can yield appreciable errors for both nitrate adsorption and dissociation, but these errors depend on the exact double layer parameters assumed in the aGC-DFT model, as well as the studied catalysts.

Results

Dopant segregation and aggregation in single-atom alloys

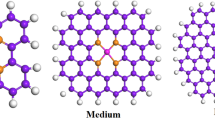

Before examining the effect of the applied potential on the ability of SAAs to promote \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) adsorption and dissociation, we evaluated their thermodynamic stability under applied potentials. SAAs suffer from stability problems under reaction conditions when the dopant atom segregates into the bulk structure or aggregates (clusters) with other dopant atoms on the surface, as illustrated in Fig. 1a17,43. While dopant segregation and aggregation are well-studied under vacuum conditions43,44,45,46, the effects of adsorbates under electrochemical conditions on the segregation and aggregation of the dopant atom are underexplored. Therefore, we analyzed the stability of eight Cu-based SAAs–Ti1Cu, Nb1Cu, Ni1Cu, Ru1Cu, Rh1Cu, Pd1Cu, Pt1Cu, and Au1Cu–because of their demonstrated activity towards ENR11,18,31.

a Schematic showing dopant segregation (top) and aggregation (bottom) over a bare X1Cu(111) surface, along with the equations to compute bare surface segregation and aggregation grand free energies, ΔΦseg(U) and ΔΦagg(U), as well as adsorbate-induced segregation and aggregation grand free energies, \(\Delta {{\varPhi} }_{{{{\rm{seg}}}}}^{{{{\rm{A}}}}^* }(U)\) and \(\Delta {{\varPhi} }_{{{{\rm{agg}}}}}^{{{{\rm{A}}}}^* }(U)\). Here, \(\Delta \Delta {{\varPhi} }_{{{{\rm{ads,1:2}}}}}^{{{{\rm{A}}}}^* }\) is the adsorption-free energy difference between system 1 and system 2. Segregation and aggregation free energies for 8 Cu-based SAAs with (b) a bare surface, (c) adsorbed hydrogen (H*), and (d) adsorbed nitrate (\({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }\)). Segregation free energy is indicated by the bar value, where values above zero signify stability on the surface. Aggregation free energy is indicated by the bar color, where values above zero (red) signify stability as a single dopant. Free energies were calculated at −0.714 V and 0.114 V (striped) using the eGC-DFT method. For \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) adsorption on Pt1Cu and Au1Cu, a white colored bar or the absence of any bar indicates that \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) would not adsorb on the site. The schematics in each figure show the expected SAA structure depending on the segregation and aggregation free energies. The data used in creating these figures is in Supplementary Tables 1-3.

Figure 1 a details the calculation of the segregation and aggregation grand free energies of the dopant atom for a bare surface (ΔΦseg(U) and ΔΦagg(U))43 or in the presence of common ENR adsorbates, H* and \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }\) (\(\Delta {{\varPhi} }_{{{{\rm{seg}}}}}^{{{{\rm{A}}}}^* }(U)\) and \(\Delta {{\varPhi} }_{{{{\rm{agg}}}}}^{{{{\rm{A}}}}^* }(U)\)). Single-atom dopants with endothermic segregation and aggregation energies are defined as thermodynamically stable. Unstable dopants are classified by their segregation and aggregation tendencies, depending on which one is more exothermic. All energies are eGC-DFT-computed energies, absent of any entropic and zero-point-energy contributions43. We used the eGC-DFT method within the Joint Density Functional Theory (JDFTx) Software with the Revised Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (RPBE) functional29,47. The grand free energies for each system are computed at −0.714 and −0.114 V versus SHE (common operating range of ENR). From this point on, U implies the SHE scale in this work. Solvent and ion effects were accounted for with the CANDLE implicit solvation model48. Thermochemistry corrections beyond those included within the implicit solvation model were excluded when computing the segregation and aggregation energies according to the methodology of Darby et al.43 See Methods for all modeling details. Simulation benchmarking and the equations for computing segregation and aggregation free energies can be found in Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1.

In the absence of adsorbates, only Pd1Cu, Pt1Cu, and Au1Cu prefer to stay as SAAs based on the thermodynamics of SAA dopant segregation (ΔΦseg(U) > 0) and aggregation (ΔΦagg(U) > 0), as shown in Fig. 1b. Ti1Cu, Ni1Cu, and Rh1Cu have small ΔΦseg(U) and ΔΦagg(U) with values between −20 kJ/mol and 13 kJ/mol only. Nb1Cu and Ru1Cu both have highly exothermic ΔΦseg(U) and ΔΦagg(U) indicating thermodynamic preferences for dimers.

For most of the SAAs, the applied potential has a negligible effect on the segregation and aggregation thermodynamics without adsorbates. However, Ti1Cu and Nb1Cu have non-negligible variations in their ΔΦseg(U) with the applied potential. Both Wang et al. and Gupta et al. demonstrated partial +1 charges on Ti and Nb dopants, which we confirmed (see Supplementary Fig. 2), due to electron transfer with the Cu host18,49. These positively charged dopants become increasingly unstable as the surface is negatively charged at −0.714 V vs SHE.

The data in Fig. 1c shows that adsorbed hydrogen makes the segregation free energy of the dopant more endothermic (\(\Delta {{\varPhi} }_{{{{\rm{seg}}}}}^{{{{\rm{H}}}}^* }(U) > \Delta {{\varPhi} }_{{{{\rm{seg}}}}}(U)\)) for most SAAs, resulting in positive or near zero values at both potentials ( < 10 kJ/mol). Compared to adsorption on a pure Cu surface, H* binds more strongly on Ti1Cu through Pt1Cu SAAs but weaker on Au1Cu. The preference of H* to bind to the dopant over Cu explains why it stabilizes most dopants against segregation (compared to their bare surfaces). Conversely, H* makes the aggregation free energy of these dopants slightly more exothermic. However, Ti1Cu, Ni1Cu, Rh1Cu, Pd1Cu, and Pt1Cu maintain relatively small \(\Delta {{\varPhi} }_{{{{\rm{agg}}}}}^{{{{\rm{H}}}}^* }(U)\) with values between −15 kJ/mol and 10 kJ/mol only. Nb1Cu and Ru1Cu maintain their thermodynamic preferences for dimers. Across all SAAs, only Ti1Cu and Nb1Cu have \(\Delta {{\varPhi} }_{{{{\rm{seg}}}}}^{{{{\rm{H}}}}^* }(U)\) and \(\Delta {{\varPhi} }_{{{{\rm{seg}}}}}^{{{{\rm{H}}}}^* }(U)\) that change significantly with the applied potential.

As with H*, \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }\) induces stability on the surface when it interacts with the dopant site more strongly than with a pure Cu site. That is the case for Ti1Cu, Nb1Cu, Ni1Cu, Ru1Cu, Rh1Cu, and Pd1Cu, where \(\Delta {{\varPhi} }_{{{{\rm{seg}}}}}^{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^* }(U)\) are positive or near-zero. Conversely, \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }\) interacts with Pt and Au more weakly than Cu, which destabilizes Pt1Cu with \(\Delta {{\varPhi} }_{{{{\rm{seg}}}}}^{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^* }(U) < 0\). \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }\) did not adsorb on Pt dimers at −0.714 V only and adsorbed on Au single atom sites only at −0.114 V, indicating its preference to adsorb to pure Cu sites and the effects of the applied potential on \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) adsorption. As for aggregation tendencies in the presence of \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }\), Pd1Cu maintains its stability against surface aggregation while Ni1Cu, Rh1Cu, and Ru1Cu have \(\Delta {{\varPhi} }_{{{{\rm{agg}}}}}^{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^* }(U)\) between −0.20 kJ/mol (Rh1Cu) and −60 kJ/mol (Ru1Cu). Ti1Cu and Nb1Cu have highly exothermic \(\Delta {{\varPhi} }_{{{{\rm{agg}}}}}^{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^* }(U)\) with values between −60 kJ/mol and −140 kJ/mol due to their strong interaction with \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }\). Refer to Supplementary Fig. 3 for DFT-optimized structures of \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }\) interacting with the different SAAs.

Overall, Pd1Cu is stable against surface segregation and aggregation across all conditions. Ni1Cu, Ru1Cu, and Rh1Cu maintain positive or near-zero segregation energies with low to moderate aggregation energies, especially in the presence of adsorbed H* and \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }\). While Pt1Cu and Au1Cu maintain stability across most conditions, they adsorb \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }\) weakly, indicating that \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }\) may bind to pure Cu sites rather than the dopant sites. Both Ti1Cu and Nb1Cu show large tendencies to cluster around \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }\). Therefore, we only considered the performance of stable and potentially meta-stable SAAs for nitrate adsorption and dissociation, including Ni1Cu, Ru1Cu, Rh1Cu, and Pd1Cu.

Potential dependence of nitrate adsorption and its link to charge transfer

When \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) adsorbs onto an electrode, it is expected to donate at least some of its charge to the metal surface, which has been shown through cyclic voltammetry experiments50. However, the extent of the charge transfer, understood via the electrosorption valency, is unknown both computationally and experimentally. Typically, the CHE model is used to evaluate the potential dependence of this reaction, which assumes a full electron donation to the surface upon adsorption. To address the validity of this assumption, we computed how the adsorption free energy of \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) (\(\Delta {{\varPhi} }_{{{{\rm{ads}}}}}^{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}(U)\)) changes with the applied potential through eq. (9), where \({{\varPhi} }_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}(U)\) is the grand free energy of the surface with nitrate adsorbed and Φ*(U) is the grand free energy of the surface without adsorbates. We modeled this adsorption as a PCET reaction step referenced to gaseous HNO3. \({G}_{{{{{\rm{HNO}}}}}_{3}}\) and \({G}_{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{2}}\) are the Gibbs free energies of gas phase HNO3 and H2. See Supplementary Note 2 for the thermodynamic cycle used in deriving Eq. (9), which was adapted from the work of Tran et al.51

We computed \(\Delta {{\varPhi} }_{{{{\rm{ads}}}}}^{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}(U)\) and the electrosorption valency for this reaction step in three ways: (1) using the CHE model and approximating \({{\varPhi} }_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}(U)\) and Φ*(U) with energies computed at their respective PZCs (\({U}_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }},{U}_{* }\)); (2) using aGC-DFT to approximate \({{\varPhi} }_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}(U)\) and Φ*(U); and (3) using eGC-DFT to compute \({\Phi }_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}(U)\) and Φ*(U) directly. For aGC-DFT, we derived eq. (10) by substituting eq. (7) for \({{\varPhi} }_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}(U)\) and Φ*(U). In this model, \(U^{\prime} =U-{U}_{\chi }\), which is the shift from the PZC of a bare surface (χ = *) or a surface with \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{*}\) (χ = \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }\)) to U. \(\Delta {{\varPhi} }_{{{{\rm{ads}}}}}^{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}({U}_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }},{U}_{* })\) represents the potential-independent adsorption energy computed with canonical DFT at the respective PZC of each state (i.e., \(\Delta {{\varPhi} }_{{{{\rm{ads}}}}}^{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}({U}_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }},{U}_{* })={{\varPhi} }_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}({U}_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }})-\left({{\varPhi} }_{{{{\rm{slab}}}}}({U}_{* })+{G}_{{{{{\rm{HNO}}}}}_{3}}-\frac{1}{2}{G}_{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{2}}\right)+0.07\)). We assumed a double layer thickness of 3 Å and a relative permittivity (εr) of 78.4 (water). To compute energies at the PZC for the CHE model and the aGC-DFT method, we used the Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP) with the RPBE functional and VASPSol continuum solvation model to simulate solvent and ion effects47,52,53,54,55,56. To compute grand free energies with the eGC-DFT method, we used JDFTx with similar settings (exchange-correlation functional, energy cutoff) as used in VASP. See Methods for all modeling details and Supplementary Note 3 for calculating aGC-DFT parameters.

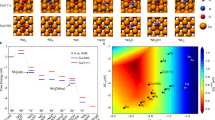

We first considered the potential dependence of \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) adsorption over Cu(111), one of the most well-studied catalysts for ENR57. In this work, when discussing the potential dependence of any reaction step, we use units of \(\frac{{{{\rm{eV}}}}}{{{{\rm{V}}}}}\), which represents the instantaneous rate of change in the energy (eV) over a 1 V range. Predictions of \(\Delta {{\varPhi} }_{{{{\rm{ads}}}}}^{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}(U)\) using the three different approaches within a range of −1.0 to 1.0 V are shown in Fig. 2a. We note that the eGC-DFT curve is shifted upwards in energy by less than 0.1 eV compared to the aGC-DFT model predictions. We found the difference in implicit solvation methods used within JDFTx versus VASPSol causes this small deviation. The electrosorption valencies (m) are represented by the slope of each line in Fig. 2a, that is the explicit (meGC-DFT) and analytical (maGC-DFT) models predict similar electrosorption valencies of −0.58 \(\frac{{{{\rm{eV}}}}}{{{{\rm{V}}}}}\) and −0.69 \(\frac{{{{\rm{eV}}}}}{{{{\rm{V}}}}}\). The CHE model always assumes an electrosorption valency (mCHE) of −1.00 \(\frac{{{{\rm{eV}}}}}{{{{\rm{V}}}}}\) for one full electron transfer assumed upon adsorption. Given the agreement between the aGC-DFT and eGC-DFT results, we concluded that (1) the analytical model can approximate grand free energies reasonably well compared to the eGC-DFT method and (2) the CHE model overpredicts the potential dependence of \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) adsorption for Cu(111) (i.e., ∣mCHE∣ > ∣meGC-DFT∣, ∣maGC-DFT∣). Although we could not find experimentally measured electrosorption valencies for \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) adsorption to confirm these values over Cu(111), JDFTx-computed electrosorption valencies have been shown to align well with experimentally measured values51.

a \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) adsorption free energy (\(\Delta {\varPhi }_{{{{\rm{ads}}}}}^{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}(U)\)) versus the potential on Cu(111), calculated based on the computational hydrogen electrode model (CHE), the analytical GC-DFT model (aGC-DFT), and explicit GC-DFT (eGC-DFT). Electrosorption valencies (mi) are written inset. The eGC-DFT model is represented by a line of best fit to free energies computed at select potentials, whereas the CHE and aGC-DFT models are continuous representations of \(\Delta {{\varPhi} }_{{{{\rm{ads}}}}}^{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}(U)\). All energies are computed at a temperature of 298 K and pH of 7.0. b The change in surface normal dipole moment from \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) adsorption (\(\Delta {\mu }_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}\)) versus the partial charge transfer from \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) to the surface (\(\Delta {q}_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}\)) of different pure metals and SAAs. The color bar indicates the electrosorption valency. Circles represent the (111) and (0001) facets, and squares represent the (100) facet. X1Cu SAAs are labeled inset as X1. The data used in creating these figures is in Supplementary Table 4.

To analyze the source of the potential dependence, we derived an expression for the electrosorption valency through the 1st-order derivative of eq. (10), shown in eq. (11). As shown, the electrosorption valency is a function of both the change in the surface dipole moment upon adsorption, \(\Delta {\mu }_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}\), the polarizability of the adsorbate, \({\alpha }_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}}\), and U0 (as well as double layer properties). Although eq. (11) states that \(\Delta {{\varPhi} }_{{{{\rm{ads}}}}}^{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}(U)\) is nonlinear (\(\frac{\partial \Delta {{\varPhi} }_{{{{\rm{ads}}}}}^{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}(U)}{\partial U}=f(U)\)), the data in Fig. 2a shows a linear potential dependence that is well predicted by \(\Delta {\mu }_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}\) (i.e., \(-1+\frac{2\Delta {\mu }_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}}{d}=-0.69\frac{{{{\rm{eV}}}}}{{{{\rm{V}}}}}\)), emphasizing that polarizability effects are negligible under the assumed conditions. This change in dipole moment directly controls the net capacitive energy to charge the double layer and the net dipole-field interactions.

Results from aGC-DFT for \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) adsorption across (111) and (100) facets of pure metals and the identified stable/meta-stable SAAs further support the correlation between \(\Delta {\mu }_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}\) and electrosorption valencies (see Supplementary Fig. 4). Although we only studied the stability of (111) facets of the Cu-based SAAs, we also included the (100) facets to examine facet effects on the potential dependence. Electrosorption valencies for each metal ranged between −0.60 \(\frac{{{{\rm{eV}}}}}{{{{\rm{V}}}}}\) and −0.80 \(\frac{{{{\rm{eV}}}}}{{{{\rm{V}}}}}\), indicating that the potential dependence changes with the metal catalyst. A combination of factors, including (1) electron redistribution on the surface due to Pauli repulsion between the adsorbate and surface electrons, (2) the intrinsic dipole moment of the molecule, and (3) partial charge transfer between the adsorbate and the surface, can influence \(\Delta {\mu }_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}\), and hence the electrosorption valency58,59,60,61,62. In the case of anion adsorption, this process is expected to be dominated by partial charge transfer from \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) to the surface (as assumed by the CHE model).

We used the Density Derived Electrostatics and Chemical Charges (DDEC6) atomic population analysis to confirm the residual charge on \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }\) and compute the partial charge transfer from \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) to the surface upon adsorption, \(\Delta {q}_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}\)63. As shown in Fig. 2b, \(\Delta {q}_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}\) ranges between 0.60e− and 0.80e− across metals and correlates inversely with \(\Delta {\mu }_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}\). This indicates that \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) retains some of its negative charge upon adsorption and that increased \(\Delta {q}_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}\) yields smaller \(\Delta {\mu }_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}\) and thus greater potential dependencies (i.e., \(\uparrow | \Delta {q}_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}|\), \(\downarrow | \Delta {\mu }_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}|\), ↑∣maGC-DFT∣). Therefore, while the CHE model correctly assumes the potential dependence for \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) adsorption is dominated by charge transfer from \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) to the surface, it overestimates the potential dependence by expecting a full electron donation across all catalysts.

From Fig. 2b, it is apparent that non-noble metals, such as Ru, Rh, and Ni, have greater \(\Delta {q}_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}\) than more noble metals, such as Cu and Pd. SAAs also have varying potential dependencies with their values generally being a weighted average of the electrosorption valencies/charge transfer of the pure Cu host and of the pure dopant surface. To relate this behavior to metal properties, we correlated \(\Delta {q}_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}\) with the fractional d-band filling of each metal, fd, computed from the projected density of states (pDOS) of the d-band of the two atoms bound to \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }\). As the d-band center of the metal approaches the system’s Fermi energy and the d-band width increases, the number of unoccupied states (shown by the unshaded region above 0 eV) increases. As shown in Fig. 3, this effect results in lower fd and thus, greater charge transfer to the metal atoms. Therefore, metals with lower fd, such as Ru, Rh, and Ni, have greater potential dependencies and \(\Delta {q}_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}\) than Cu and Pd. Additionally, (111) facets of the same metal have greater potential dependencies than (100) facets, which have slightly larger fd. See Methods for computing the pDOS of each metal in VASP.

The SAAs also follow these nobility trends in electrosorption valencies, with their behavior modulated by the Cu host. However, their behavior is well predicted by fd of the pure metals comprising the alloy. Larger differences in the fd of pure Cu and that of a pure dopant atom yield a smaller SAA fd, and thus increased charge transfer to the surface. For example, Ru(0001) and Cu(111) have the greatest difference in their pure metal fd values (0.24) and thus Ru1Cu pulls the most charge off \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) compared to the other SAAs. Thus, when a metal with low d-band filling (i.e., Ru) is coupled with Cu in the SAA, it will enhance the potential dependence of the catalyst with electrosorption valencies somewhere between that of the pure Cu and the dopant metal.

In summary, contributions to the electrosorption valency, as shown in eq. (11), can be partitioned into (1) surface normal dipole moment changes resulting largely from the partial charge transfer from \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) to the surface, and (2) induced electric field interactions due to the polarizability of the adsorbed nitrate. As previously concluded, for an assumed εr and d of 78.4 and 3.0 Å, the potential dependence is well determined by the change in surface normal dipole moment across all metals. Under variations in εr ∈ [1, 80] and d ∈ [3, 7] Å, we found that this conclusion remains valid until the electric field in the double layer becomes excessively strong and the dielectric medium cannot effectively screen the strong electric field interactions (see Supplementary Fig. 5). These effects become significant when εr < 5 and d ≤ 5 Å, respectively. Within this range, \(\Delta {{\varPhi}}_{{{{\rm{ads}}}}}^{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}(U)\) is still linear with U, but \(\frac{\partial \Delta {{\varPhi} }_{{{{\rm{ads}}}}}^{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}(U)}{\partial U}\) now includes non-negligible polarizability contributions from \(\frac{{\alpha }_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}}{\mu }_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}}{\varepsilon Ad}\). See Supplementary Note 4 for a more in-depth discussion on the sensitivity of the electrosorption valency of Cu(111) to εr and d.

Potential dependence of nitrate dissociation to nitrite

We considered the potential dependence of \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }\) dissociation to \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{2}^{* }\) over Cu(111). This reaction is typically considered to be potential-independent, as it involves neither proton transfer nor electron transfer. To assess this assumption, we computed how the activation free energy for direct N-O bond cleavage (\({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }+* \to {{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{2}^{* } + {\rm{O}}^*\)) changes with applied electrochemical potential through eq. (12), where Φ‡(U) is the transition state grand free energy. We also evaluated the variation in dissociation free energy with applied potential and found the reaction free energy exhibited negligible dependence on potential across all studied metals (see Supplementary Note 5 and Supplementary Table 5).

As before, we assess the potential dependence of ΔΦ‡(U) using three models. Firstly, we neglect the potential dependence by approximating \({{\varPhi}}_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}(U)\) and Φ‡(U) with energies computed at their respective PZCs (U*, U‡). We then used the aGC-DFT method to approximate \({{\varPhi}}_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}(U)\) and Φ‡(U) through eq. (7) and the eGC-DFT method to compute \({{\varPhi}}_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}(U)\) and Φ‡(U) directly. For the aGC-DFT method, we modeled ΔΦ‡(U) through eq. (13). Unlike eq. (10), this expression includes an additional polarizability term for both the transition state and the initial state, as both contain adsorbates. Note that this is the exact model proposed by Agrawal et al. to compute potential dependent activation barriers37. All calculations were converged with the Climbing Image Nudge Elastic Band (CI-NEB) method within a force tolerance of 0.05 \(\frac{{\mbox{eV}}}{\mathring{{{\rm{A}}}}}\). See Methods for all modeling details and Supplementary Note 3 for calculating aGC-DFT parameters at transition states.

The data in Fig. 4a shows the three predictions of ΔΦ‡(U) between −1.0 to 1.0 V. Neglecting the potential dependence yields a constant activation free energy of 0.45 eV or 43.42 kJ/mol. Naturally, the analytical method predicts the same activation energy at the PZC but with a slope (maGC-DFT), of −0.17 \(\frac{{{{\rm{eV}}}}}{{{{\rm{V}}}}}\). This is considerably closer to the slope predicted by the explicit method (meGC-DFT = −0.24 \(\frac{{{{\rm{eV}}}}}{{{{\rm{V}}}}}\)). The inflections within the eGC-DFT curve in Fig. 4a arise from slight variations in thermochemistry energy corrections with the applied potential, due to variations in the vibrational partition function. If we fit the energies without the thermochemistry corrections, these inflections disappear and R2 = 1.00.

a Activation free energy for \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }\) dissociation (ΔΦ‡(U)) versus the potential on Cu(111), calculated using analytical GC-DFT (aGC-DFT) and explicit GC-DFT (eGC-DFT). The computed activation barrier at the PZC (null) is also shown. All energies are computed at a temperature of 298 K. Potential dependencies (mi) are written inset. b The change in the surface normal dipole moment from \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }\) to the transition state (Δμ‡) versus the potential dependence (maGC-DFT). Circles represent the (111) and (0001) facets, and squares represent the (100) facets. X1Cu SAAs are labeled inset as X1. The data used in creating these figures is in Supplementary Table 5.

As we observed for \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) adsorption over Cu(111), ΔΦ‡(U) has a linear potential dependence that is well determined by the Δμ‡ (i.e., \(\frac{2\Delta {\mu }_{{{\ddagger}} }}{d}=-0.17\frac{{{{\rm{eV}}}}}{{{{\rm{V}}}}}\)). According to the first-order derivative of eq. (13), shown in eq. (14), this indicates that the net capacitive energy to charge the double layer and the net dipole-field interactions, both controlled by Δμ‡, outweigh the polarizability effects of both adsorbed nitrate and the transition state. Therefore, the small dipole moment change from the partial N-O bond cleavage at the transition state yields a potential dependence for this \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) dissociation step that is approximately a third of the electrosorption valency for \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) adsorption ( −0.17 \(\frac{{{{\rm{eV}}}}}{{{{\rm{V}}}}}\) versus −0.58 \(\frac{{{{\rm{eV}}}}}{{{{\rm{V}}}}}\)).

The data in Fig. 4b demonstrates that these findings hold across the pure metals and SAAs analyzed in this work. Potential dependencies range between −0.04 \(\frac{{{{\rm{eV}}}}}{{{{\rm{V}}}}}\) and −0.20 \(\frac{{{{\rm{eV}}}}}{{{{\rm{V}}}}}\) with larger ∣Δμ‡∣ yielding greater net capacitative energies to charge the double layer, increased net dipole-field interactions, and thus greater potential dependencies (i.e., ∣maGC-DFT∣) for the dissociation step. Across all metals, there is generally negligible partial charge transfer along the reaction coordinate (see Supplementary Fig. 6), which leads to smaller changes in the surface normal dipole moment and explains the decreased potential dependence compared to nitrate adsorption, albeit still appreciable. Therefore, while the traditional assumption that there is no charge transfer along this reaction is correct, the dissociation still has some non-negligible potential dependence, most likely due to some electron redistribution following partial cleavage of the N-O bond at the transition state. This partial cleavage results in a reduction in the surface normal dipole moment for all metals. Unlike for \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }\) adsorption, the trends in the surface normal dipole moments, and hence the potential dependence, of the SAAs are not well understood by examining the potential dependence or properties of the pure metals.

In summary, contributions to the potential dependence, as shown in eq. (14), can be partitioned into (1) surface normal dipole moment changes due to the partial N-O bond cleavage, and (2) induced electric field interactions due to the polarizability of (2a) adsorbed nitrate and (2b) the transition state structure. While the relative contribution of the polarizability effects are more sensitive to variations in εr and d than for nitrate adsorption, the change in the surface normal dipole moment still dominates the potential dependence until the electric field in the double layer becomes excessively strong and the dielectric medium cannot effectively screen the strong electric field interactions (see Supplementary Fig. 7). These effects become significant for εr < 5 and d ≤ 5 Å, respectively. At this point, ΔΦ‡(U) is still linear with U, but \(\frac{\partial \Delta {{\varPhi} }^{{{\ddagger}} }(U)}{\partial U}\) now includes non-negligible polarizability contributions from both \(\frac{{\alpha }_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}}{\mu }_{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}}{\varepsilon Ad}\) and \(\frac{{\alpha }_{{{\ddagger}} }{\mu }_{{{\ddagger}} }}{\varepsilon Ad}\). See Supplementary Note 6 for a more in-depth discussion on the sensitivity of the potential dependence of Cu(111) to εr and d.

Errors in neglecting EDL effects, model sensitivity and selection

We quantified approximate errors in neglecting EDL effects by using just the CHE model for \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) adsorption and neglecting the potential dependence altogether for \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }\) dissociation for different catalysts and EDL parameters. Overall, this analysis aims to further inform the modeling community about the errors associated with typical assumptions used for atomistic modeling of electrocatalytic reactions and the sensitivity of GC-DFT results on the EDL parameters.

To understand the error associated with neglecting EDL effects and the variability with assumed EDL parameters, we considered Ni SAAs on Cu. The stability and activity of Ni1Cu(111) and Ni1Cu(100) towards ENR have been validated through both experimental research and canonical DFT modeling8,12,64. Additionally, across all studied SAAs, Ni1Cu(111) is moderately stable against surface segregation and aggregation (Fig. 1), adsorbs \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) moderately ( −22.48 kJ/mol at PZC), and cleaves the N-O bond with a relatively low dissociation barrier (46.30 kJ/mol at PZC).

The computed errors for Ni1Cu(111), Ni1Cu(100), and Cu(111) are shown in Fig. 5a, b, assuming a relative permittivity of 78.4 (water) and double layer thickness of 3 Å. We completed this analysis between −1.30 and 0.20 V to align with typical operating ranges of ENR over Cu catalysts12,65. Within this range, Ni1Cu(111) has a maximum error of 32.52 kJ/mol for \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) adsorption and 21.72 kJ/mol for \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }\) dissociation at −1.30 V. Cu(111)’s maximum errors are similar to Ni1Cu(111) at −1.30 V while Ni1Cu(100) has maximum errors of 31.77 kJ/mol and 15.05 kJ/mol at −1.30 V.

Approximate errors for Ni1Cu(111), Ni1Cu(100), and Cu(111) from (a) computing the adsorption free energy of nitrate (\(\Delta {{\varPhi} }_{{{{\rm{ads}}}}}^{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}(U)\)) with the CHE model versus the aGC-DFT method, and (b) computing the activation free energy for nitrate dissociation (ΔΦ‡(U)) with no potential dependence versus the aGC-DFT method. Errors at each potential were computed with a relative permittivity (εr) of 78.4 (water) and double layer thickness (d) of 3.0 Å. The star indicates the potential at which we considered the variations in errors with double layer properties for Ni1Cu while \({U}_{\min }\) is the potential at which the error is minimized. A heat map of computed error at −0.55 V for (c) nitrate adsorption and (d) nitrate dissociation, showing the variation in the computed errors with relative permittivity (εr) and double layer thickness (d). The stars represent the error computed with a εr of 78.4 (water) and d of 3.0 Å.

In Fig. 5a, b, all metals obtain a minimum error of 0.0 kJ/mol between −0.3 V and 0.1 V. We derived an expression for the potential at which the error is minimized (\({U}_{\min }\)), i.e., where neglecting EDL effects (such as by using the CHE model) results in no error (see Supplementary Note 7 for derivation). This \({U}_{\min }\) is a function of the bare surface PZC, U0, as well as a term that shifts the PZC from U0 due to the presence of surface normal dipole moments. This expression indicates why −1.30 V yields the maximum error for all metals, as it is furthest from their PZCs (see Supplementary Note 3 for computing PZCs). The difference between \({U}_{\min }\) across metals can also be explained by examining their respective PZCs. Cu(111) and Ni1Cu(111) have almost identical \({U}_{\min }\) because of the similar PZCs between the surfaces (U0,Cu(111) = −0.090 V, \({U}_{0,{{{{\rm{Ni}}}}}_{1}{{{\rm{Cu}}}}(111)}=-0.085\) V) while Ni1Cu(100)’s error curve is shifted to the left with smaller maximum errors because of its more negative PZC (\({U}_{0,{{{{\rm{Ni}}}}}_{1}{{{\rm{Cu}}}}(100)}=-0.30\)V ). However, we would like to emphasize that the PZC of a metal is not a universal point that will minimize the error in neglecting EDL effects when computing reaction energies. If the adsorbate induces large surface normal dipole moments and/or the dielectric constant is small enough, then \({U}_{\min }\) could be significantly different than the PZC of the metal.

When using the aGC-DFT model, the assumed double layer parameters, including εr and d, introduce variability in aGC-DFT computed \(\Delta {\it{\Phi} }_{{{{\rm{ads}}}}}^{{{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }}(U)\) and ΔΦ‡(U). Given the variations in aGC-DFT computed energies with double layer properties, we generated heat maps for the computed errors across various εr and d for Ni1Cu(111), shown in Fig. 5c, d. For nitrate adsorption and dissociation, errors are < 7 kJ/mol for large εr and d, but hyperbolically increase as εr and d decrease. The error from CHE model exceeds 60 kJ/mol for \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) adsorption and 50 kJ/mol for \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }\) dissociation at a relative permittivity of 1 (vacuum) and a double layer thickness of 3 Å. Referring to the derived equation for computing the error (see Supplementary Note 7 for the equation), the contributions to the error come from the capacitive energy to charge the double layer and the electric field interactions. Specifically, as d and εr approach infinity, the capacitive energy and the electric field interactions become negligible. However, a medium with a small εr minimally screens electric field interactions, while both the electric field strength and the energy to charge a double layer become extensive with small d. Overall, in the regime of small εr and d, there are large contributions from these energy terms to the computed grand free energies, which should not be neglected. Based on these results and the uncertainty in EDL parameters, it is recommended to consider EDL effects in computed reaction energetics, even for non-PCET reactions, to avoid significant errors.

Conclusions

Knowledge of the potential dependence of \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) adsorption and \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }\) dissociation as a function of catalyst composition is important for understanding the electrocatalytic reduction of nitrate. Herein, we analyzed \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) adsorption and \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{* }\) dissociation on pure metals and stable and meta-stable Cu-based single-atom alloy (SAAs) catalysts using both analytical and explicit GC-DFT. We demonstrated that the potential dependence of \({{{{\rm{NO}}}}}_{3}^{-}\) adsorption and dissociation is linearly dependent on the change in the surface normal dipole moment along the reaction coordinate. However, if the electric field interactions are excessive in the double layer, then the polarizability of the adsorbed structure contributes significantly to the potential dependence of both reaction steps.

Altogether, we have presented three models in this work that can consider these potential dependent PCET and non-PCET reactions. The CHE model, which considers only PCET reactions, is the most computationally efficient method. However, it neglects EDL effects and can result in large errors when compared to aGC-DFT computed energies. aGC-DFT presents a computationally efficient way to approximate grand free energies and the potential dependence of both PCET and non-PCET reaction steps, but it is sensitive to the assumed double layer parameters, such as d and εr. Furthermore, aGC-DFT neglects structural changes under applied potentials. If this is of interest, as was the case for potential-dependent segregation and aggregation energies, then eGC-DFT is the appropriate method. However, this method is more computationally intensive than canonical DFT and still maintains some arbitrariness in parameterizing the EDL.

All three methods typically rely on some implicit solvation model to simulate solvation effects during the reaction. However, the inclusion of explicit water molecules and ions is desirable for a full assessment of the potential dependence of these reaction steps because it could alter both the adsorption and dissociaiton of nitrate. However, using explicit solvation requires rigorous statistical sampling to obtain ensemble averages, which is computationally demanding with ab initio methods37. Development of machine learned force fields with near first-principles accuracy to enable simulations with explicit solvation is a promising approach to address this challenge66.

Methods

Dopant segregation and aggregation modeling in JDFTx

All DFT calculations for the segregation and aggregation studies were performed using JDFTx with the RPBE functional29,47. We initially employed JDFTx to study potential-dependent segregation and aggregation energies over other plane wave-based DFT program packages (e.g., VASP with VASPSol++) because it was noted to be very effective at implicit solvation simulation of extended metallic electrodes20. A plane wave energy cutoff of 544 eV was used for valence electron expansion, while the core electrons were accounted for using projected augmented wave potentials. Spin-polarized calculations were done for Ni1Cu only. Each surface was modeled using a 3 × 3 × 5 supercell with the top 4 layers able to relax (along with adsorbates) and the bottom layer fixed in its lattice coordinates. The Brillouin zone was sampled with a 4 × 4 × 1 Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid67,68. Periodic images in the z-direction were separated by a vacuum layer of 15 Å to minimize periodic interactions. Forces were converged to < 0.01 eV/Å.

A surface atom in the Cu host metal (computed lattice constant: 3.70 Å) was replaced by a dopant atom to simulate the SAA structure. For aggregation studies, an adjacent Cu atom on the surface layer was replaced by a dopant. For segregation studies, a Cu atom in the third layer was replaced by a dopant atom to simulate the dopant in the subsurface, while the surface layer was pure Cu. This methodology was benchmarked with the results of Darby et al., as shown in Supplementary Fig. 143.

For computing grand free energies, we used the CANDLE implicit solvation model to account for solvent and ion effects48. To simulate an applied potential, we set the electronic Fermi energy (equal to the electrochemical potential of an electron, μe) to the target potential, which was converted to the SHE scale via \({U}_{{{{\rm{SHE}}}}}=\frac{-{\mu }_{e}-{\phi }_{{{{\rm{ref}}}}}}{e}\). In this work, ϕref = 4.66 eV, as calibrated to the CANDLE implicit solvation model48.

Nitrate adsorption and dissociation in VASP and JDFTx

All DFT calculations for both the CHE model and the analytical GC-DFT method were completed using VASP with the RPBE functional47,52,53,54,55,56. A plane wave energy cutoff of 544 eV was used for valence electron expansion, while the core electrons were accounted for using the projected augmented wave potentials. Spin-polarized calculations were done for Ni only. We found that Ni1Cu energetics and system properties did not change with and without spin-polarization. Each structure was modeled using a 3 × 3 × 4 supercell with the top two layers able to relax (along with adsorbates) and the bottom two layers fixed in their lattice coordinates. Pure metal lattice constants were computed and used to generate each slab. For SAAs, a surface atom in the Cu host metal (computed lattice constant: 3.70 Å) was replaced by the dopant atom(s) to simulate the SAA structure. The Brillouin zone was sampled with a 4 × 4 × 1 Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid. Periodic images in the z-direction were separated by a vacuum layer of 15 Å to minimize interactions. All adsorbates and the two topmost slab layers were relaxed by geometry optimization, with forces converged to < 0.01 eV/Å. For transition state searches, we used CI-NEB method with forces converged to < 0.05 eV/Å, implemented in VASP TST69. The VASPSol continuum solvation model was utilized to simulate solvent and ion effects52,53.

Explicit GC-DFT calculations for adsorption and dissociation studies over Cu(111) were completed using JDFTx with the RPBE Functional and the CANDLE implicit solvation model29,47,48. To match our calculations from VASP, we used an identical plane wave energy cutoff and force tolerances for geometry optimizations, completed in JDFTx, and CI-NEB calculations, completed in the Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE) with a JDFTx calculator70. Cu(111) was modeled using the exact slab size, z-directional vacuum, and Brillouin zone sampling as employed in VASP. Grand free energies were computed according to the methodology outlined for the segregation and aggregation studies.

In VASP and JDFTx, all transition states were confirmed to have one large imaginary frequency corresponding to the N-O bond dissociation. Enthalpic and entropic thermochemistry corrections for H2(g), HNO3(g), adsorbed nitrate in solution, and nitrate dissociation barriers were computed using the rigid rotor harmonic oscillator approximation as implemented in (ASE)70.

Projected density of states calculations in VASP

pDOS calculations were performed in VASP using the tetrahedron method (ISMEAR = −5) with an 11 × 11 × 1 Gamma-centered k-point grid67,68. Gaussian smoothing was applied to the pDOS data to obtain continuous, smooth distributions. The fractional d-band filling was calculated relative to the Fermi level using eq. (15), where \(\rho (\bar{\epsilon })\) is the pDOS evaluated at energy, ϵ, relative to the electronic Fermi energy, ϵfermi71.

Data availability

Simulation data, including optimized structures, input files, and all data generated during this research, can be found at the following GitHub link: https://github.com/DeanMSweeney/nitrate-GC.

References

Wei, M. et al. A Perspective on Cu-based electrocatalysts for nitrate reduction for ammonia synthesis. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 5, 2300173 (2024).

Wang, Z., Richards, D. & Singh, N. Recent discoveries in the reaction mechanism of heterogeneous electrocatalytic nitrate reduction. Catal. Sci. Technol. 11, 705–725 (2021).

Liu, J.-X., Richards, D., Singh, N. & Goldsmith, B. R. ACtivity and selectivity trends in electrocatalytic nitrate reduction on transition metals. ACS Catal. 9, 7052–7064 (2019).

Pérez-Gallent, E., Figueiredo, M. C., Katsounaros, I. & Koper, M. T. M. Electrocatalytic reduction of Nitrate on Copper single crystals in acidic and alkaline solutions. Electrochimica. Acta 227, 77–84 (2017).

Giannakakis, G., Flytzani-Stephanopoulos, M. & Sykes, E. C. H. Single-atom alloys as a reductionist approach to the rational design of heterogeneous catalysts. Accounts Chem. Res. 52, 237–247 (2019).

Gao, D., Yi, D., Xia, J., Yang, Y. & Wang, X. First-principles screening of Cu-based single-atom alloys for highly efficient electrocatalytic nitrogen reduction. Mol. Catal. 555, 113879 (2024).

Xing, F., Jeon, J., Toyao, T., Shimizu, K.-i & Furukawa, S. A Cu-Pd single-atom alloy catalyst for highly efficient NO reduction. Chem. Sci. 10, 8292–8298 (2019).

Wang, S. et al. Non-noble single-atom alloy for electrocatalytic nitrate reduction using hierarchical high-throughput screening. Nano Energy 113, 108543 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Chen, X., Wang, W., Yin, L. & Crittenden, J. C. Electrocatalytic nitrate reduction to ammonia on defective Au1Cu (111) single-atom alloys. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 310, 121346 (2022).

Da, Y. et al. The applications of single-atom alloys in electrocatalysis: progress and challenges. SmartMat 4, e1136 (2023).

Yin, H., Peng, Y. & Li, J. Electrocatalytic reduction of nitrate to ammonia via a Au/Cu single atom alloy catalyst. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 3134–3144 (2023).

Cai, J. et al. Electrocatalytic nitrate-to-ammonia conversion with ~100% Faradaic efficiency via single-atom alloying. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 316, 121683 (2022).

Darby, M. T., Réocreux, R., Sykes, E. C. H., Michaelides, A. & Stamatakis, M. Elucidating the stability and reactivity of surface intermediates on single-atom alloy catalysts. ACS Catal. 8, 5038–5050 (2018).

Hannagan, R. T., Giannakakis, G., Flytzani-Stephanopoulos, M. & Sykes, E. C. H. Single-atom alloy catalysis. Chem. Rev. 120, 12044–12088 (2020).

Yang, X.-F. et al. Single-atom catalysts: a new frontier in heterogeneous catalysis. Accounts Chem. Res. 46, 1740–1748 (2013).

Schumann, J., Stamatakis, M., Michaelides, A. & Réocreux, R. Ten-electron count rule for the binding of adsorbates on single-atom alloy catalysts. Nat. Chem. 16, 749−754 (2024).

Darby, M. T., Stamatakis, M., Michaelides, A. & Sykes, E. C. H. Lonely atoms with special gifts: breaking linear scaling relationships in heterogeneous catalysis with single-atom alloys. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9, 5636–5646 (2018).

Gupta, S., Rivera, D. J., Shaffer, M., Chismar, A. & Muhich, C. Behavior of cupric single atom alloy catalysts for electrochemical nitrate reduction: an Ab initio study. ACS ES&T Eng. 4, 166–175 (2024).

Nørskov, J. K. et al. Origin of the overpotential for oxygen reduction at a fuel-cell cathode. J. Phys. Chem. B. 108, 17886–17892 (2004).

Ringe, S., Hörmann, N. G., Oberhofer, H. & Reuter, K. Implicit solvation methods for catalysis at electrified interfaces. Chem. Rev. 122, 10777–10820 (2022).

Sebastián-Pascual, P., Shao-Horn, Y. & Escudero-Escribano, M. Toward understanding the role of the electric double layer structure and electrolyte effects on well-defined interfaces for electrocatalysis. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 32, 100918 (2022).

Li, P., Jiao, Y., Huang, J. & Chen, S. Electric double layer effects in electrocatalysis: insights from Ab initio simulation and hierarchical continuum modeling. JACS Au 3, 2640–2659 (2023).

Hörmann, N. G., Beinlich, S. D. & Reuter, K. Converging divergent paths: constant charge vs constant potential energetics in computational electrochemistry. J. Phys. Chem. C. 128, 5524–5531 (2024).

Schwarz, K. & Sundararaman, R. The electrochemical interface in first-principles calculations. Surf. Sci. Rep. 75, 100492 (2020).

Domínguez-Flores, F. & Melander, M. M. Approximating constant potential DFT with canonical DFT and electrostatic corrections. J. Chem. Phys. 158, 144701 (2023).

Jinnouchi, R. Grand-canonical first principles-based calculations of electrochemical reactions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 171, 096502 (2024).

Melander, M. M., Wu, T., Weckman, T. & Honkala, K. Constant inner potential DFT for modelling electrochemical systems under constant potential and bias. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 1–11 (2024).

Beinlich, S. D., Kastlunger, G., Reuter, K. & Hörmann, N. G. Controlled electrochemical barrier calculations without potential control. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 19, 8323–8331 (2023).

Sundararaman, R. et al. JDFTx: Software for joint density-functional theory. SoftwareX 6, 278–284 (2017).

Tran, B. & Goldsmith, B. R. Theoretical investigation of the potential-dependent CO adsorption on copper electrodes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 15, 6538–6543 (2024).

Wong, A. J.-W., Tran, B., Agrawal, N., Goldsmith, B. R. & Janik, M. J. Sensitivity analysis of electrochemical double layer approximations on electrokinetic predictions: case study for co reduction on copper. J. Phys. Chem. C. 26, 10837–10847(2024).

Clary, J. M. & Vigil-Fowler, D. Adsorption site screening on a PGM-free electrocatalyst: insights from grand canonical density functional theory. J. Phys. Chem. C. 127, 16405–16413 (2023).

Alsunni, Y. A., Alherz, A. W. & Musgrave, C. B. Electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CO over AG(110) and CU(211) modeled by grand-canonical density functional theory. J. Phys. Chem. C 125, 23773–23783 (2021).

Hörmann, N. G., Marzari, N. & Reuter, K. Electrosorption at metal surfaces from first principles. npj Comput. Mater. 6, 1–10 (2020).

Janak, J. F. Proof that \(\frac{\partial e}{\partial {n}_{i}}=\epsilon\) in density-functional theory. Phys. Rev. B. 18, 7165–7168 (1978).

Guo, Y. et al. Potential-dependent insights into the origin of high ammonia yield rate on copper surface via nitrate reduction: a computational and experimental study. J. Energy Chem. 96, 272–281 (2024).

Agrawal, N., Wong, A. J.-W., Maheshwari, S. & Janik, M. J. An efficient approach to compartmentalize double layer effects on kinetics of interfacial proton-electron transfer reactions. J. Catal. 430, 115360 (2024).

Fumagalli, L. et al. Anomalously low dielectric constant of confined water. Science 360, 1339–1342 (2018).

Saboorian-Jooybari, H. & Chen, Z. Calculation of re-defined electrical double layer thickness in symmetrical electrolyte solutions. Results Phys. 15, 102501 (2019).

Grimnes, S. & Martinsen, O. G. Chapter 7 - Electrodes. In Bioimpedance and Bioelectricity Basics (Third Edition) (eds. Grimnes, S. & Martinsen, O. G.) 179–254 (Academic Press, Oxford, 2015).

Cui, Z., Wong, A. J.-W., Janik, M. J. & Co, A. C. Negative reaction order for CO during CO2 Electroreduction on Au. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 23872–23880 (2024).

Gauthier, J. A. et al. Challenges in modeling electrochemical reaction energetics with polarizable continuum models. ACS Catal. 9, 920–931 (2019).

Darby, M. T., Sykes, E. C. H., Michaelides, A. & Stamatakis, M. Carbon monoxide poisoning resistance and structural stability of single atom alloys. Topics Catal. 61, 428–438 (2018).

Papanikolaou, K. G., Darby, M. T. & Stamatakis, M. CO-induced aggregation and segregation of highly dilute alloys: a density functional theory study. J. Phys. Chem. C. 123, 9128–9138 (2019).

Salem, M., Cowan, M. J. & Mpourmpakis, G. Predicting segregation energy in single atom alloys using physics and machine learning. ACS Omega 7, 4471–4481 (2022).

Salem, M., Loevlie, D. J. & Mpourmpakis, G. Single atom alloys segregation in the presence of ligands. J. Phys. Chem. C 127, 22790–22798 (2023).

Hammer, B., Hansen, L. B. & Nørskov, J. K. Improved adsorption energetics within density-functional theory using revised Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof functionals. Phys. Rev. B 59, 7413–7421 (1999).

Sundararaman, R. & Goddard III, W. A. The charge-asymmetric nonlocally determined local-electric (CANDLE) solvation model. J. Chem. Phys. 142, 064107 (2015).

Wang, Z., Jiao, D. & Zhao, J. A direct complete dissociation mechanism for nitrate reaction to ammonia. Mol. Catal. 552, 113692 (2024).

Richards, D., D. Young, S., R. Goldsmith, B. & Singh, N. Electrocatalytic nitrate reduction on rhodium sulfide compared to Pt and Rh in the presence of chloride. Catal. Sci. Technol. 11, 7331–7346 (2021).

Tran, B. & Goldsmith, B. Predicting competitive anion electrosorption on late transition metals. ChemRxiv 10.26434/chemrxiv-2025-pvlzg (2025).

Mathew, K., Sundararaman, R., Letchworth-Weaver, K., Arias, T. A. & Hennig, R. G. Implicit solvation model for density-functional study of nanocrystal surfaces and reaction pathways. J. Chem. Phys. 140, 084106 (2014).

Mathew, K., Kolluru, V. S. C., Mula, S., Steinmann, S. N. & Hennig, R. G. Implicit self-consistent electrolyte model in plane-wave density-functional theory. J. Chem. Phys. 151, 234101 (2019).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558–561 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Karamad, M., Goncalves, T. J., Jimenez-Villegas, S., Gates, I. D. & Siahrostami, S. Why copper catalyzes electrochemical reduction of nitrate to ammonia. Faraday Discuss. 243, 502–519 (2023).

Leung, T. C., Kao, C. L., Su, W. S., Feng, Y. J. & Chan, C. T. Relationship between surface dipole, work function and charge transfer: Some exceptions to an established rule. Phys. Rev. B 68, 195408 (2003).

Schmickler, W. & Guidelli, R. The partial charge transfer. Electrochimica. Acta 127, 489–505 (2014).

Rusu, P. C. & Brocks, G. Surface dipoles and work functions of alkylthiolates and fluorinated alkylthiolates on Au(111). J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 22628–22634 (2006).

Hofmann, O. T., Atalla, V., Moll, N., Rinke, P. & Scheffler, M. Interface dipoles of organic molecules on Ag(111) in hybrid density-functional theory. N. J. Phys. 15, 123028 (2013).

Otero, R., Vázquez de Parga, A. L. & Gallego, J. M. Electronic, structural and chemical effects of charge-transfer at organic/inorganic interfaces. Surf. Sci. Rep. 72, 105–145 (2017).

Limas, N. G. & Manz, T. A. Introducing DDEC6 atomic population analysis: part 4. Efficient parallel computation of net atomic charges, atomic spin moments, bond orders, and more. RSC Adv. 8, 2678–2707 (2018).

Patel, D. A. et al. Atomic-scale surface structure and CO tolerance of NiCu single-atom alloys. J. Phys. Chem. C 123, 28142–28147 (2019).

Jia, Z., Feng, T., Ma, M., Li, Z. & Tang, L. Emerging advances in Cu-based electrocatalysts for electrochemical nitrate reduction (NO3RR). Surf. Interf. 48, 104294 (2024).

Chen, B. W. J., Zhang, X. & Zhang, J. Accelerating explicit solvent models of heterogeneous catalysts with machine learning interatomic potentials. Chem. Sci. 14, 8338–8354 (2023).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Pack, J. D. & Monkhorst, H. J. "Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations”—a reply. Phys. Rev. B 16, 1748–1749 (1977).

Henkelman, G., Uberuaga, B. P. & Jónsson, H. A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9901–9904 (2000).

Hjorth Larsen, A. et al. The atomic simulation environment—a Python library for working with atoms. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 29, 273002 (2017).

Norskov, J. K., Studt, F., Frank, A. P. & Bligaard, T. Fundamental Concepts in Heterogeneous Catalysis 1st edn (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the National Science Foundation for providing funding support for this research via the CAREER Award 2236138.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.S. wrote the initial manuscript draft, performed all computational studies, and was responsible for data collection and analysis. B.T. reviewed/edited the manuscript and advised D.S. on all computational studies. B.G. reviewed/edited the manuscript, advised D.S. on all computational studies, and conceived the original work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Shyam Deo and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sweeney, D.M., Tran, B. & Goldsmith, B.R. A grand canonical study of the potential dependence of nitrate adsorption and dissociation across metals and dilute alloys. Commun Chem 8, 182 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01579-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01579-y

This article is cited by

-

Robust catalyst assessment for the electrocatalytic nitrate reduction reaction

Communications Chemistry (2025)