Abstract

Strong light-matter interactions demonstrated considerable potential to control photochemical reactions. Here, we coupled a single cavity mode to the electronic S0-S1 transition of azopyrrole E and Z-isomers. This allows us to observe the impact on the photoisomerization process “on-the-go”, i.e., capturing a sharp transition in the kinetics when moving from strong to weak coupling. Pumping either at the upper polaritonic state or the uncoupled population shows an acceleration of the photoisomerization process (strong to weak), whereas the opposite is observed when exciting the lower polaritonic state. Excellent correlation between spectral overlap and rate suggests that changes in photochemistry are mediated by relaxation via the dark state manifold. Remaining in the ultra-strong coupling regime affects the reaction kinetics, but without sharp transitions. Our experimental and theoretical findings underline that dynamic transitions between coupling domains might pave the way to a better understanding of how strong coupling modifies photoisomerization reactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ever since lasers were invented, one of the first thought experiments was to control chemical reactions by external stimuli. Many experiments can be found in the literature, starting from resonant/non-resonant laser excitations, which can selectively target a chemical bond1,2,3. In an unconventional attempt, the last decade witnessed the application of strong light-matter interactions for selective control of chemical reactions4,5. This phenomenon replaces external stimuli with vacuum fluctuation (aka zero-point energy), leading to the emergence of a new field of research known as polaritonic chemistry6,7. Strong coupling occurs when a molecular transition interacts resonantly with a cavity photon and overcomes other dissipation rates, forming hybrid light-matter states. The first experimental approach to control a chemical reaction was done on a photoisomerization reaction by electronic strong coupling4, which slowed down spiropyran to merocyanine conversion5. Recent literature reports suggested that many photoinduced processes can be modified by coupling to the vacuum field8,9,10,11,12. At the same time, there are claims showing negligible change in the photoisomerization process if the excitation is done at different conditions13. This includes pumping at the polaritonic states versus uncoupled/dark state manifold and also on the choice of non-cavity control experiment used to compare the reaction rates. Excitation done on the active side of a single mirror half-cavity is also found to enhance the reaction rates due to changes in the effective photon flux felt by the molecular switches14. These studies motivated us to try a system that has both E and Z isomers absorbing at the same energy that can be a good test bed for verifying polaritonic effects on photoisomerization processes.

The idea of electronic strong coupling and chemical reaction control triggered an uproar in the research community. There are many theoretical suggestions as to how the polaritonic states can store photochemical energy, thereby slowing down the conversion yield15. Standard photoswitches such as azobenzene and stilbene are a few of the molecules tested, and the results indicate a modification of the potential energy surfaces. Ultra-strong coupling (USC) can store the reaction energy for a longer time, thereby almost stopping a photoconversion process15. Some of these experiments also propose the photon mixing fraction can tailor the reaction channels, especially the conical intersections, which are important in deciding the energy flow in such systems16,17,18. Exciton-plasmon coupling is also being studied both experimentally and theoretically shown to affect the conversion yield19,20. Though these events take place in the excited states, the thermal return channel in such systems is still active and has been found to be almost independent of the excited state reaction dynamics. Further, these experiments pave the way to test the involvement of the ground state in chemical reactions by coupling vibrational transitions21. Ground state control of thermal reactions by strong coupling is another attractive challenge for selective control of chemical reactivity22,23. Here, the reaction yield is affected by the complex interplay of inter/intramolecular vibrational relaxation channels24. The latest understanding of this topic is discussed in some of the review papers25,26,27,28,29. Normally, T-type photoswitches exhibit reversibility, and hence, access to the thermal channels can be measured by observing the smooth return of the photoisomers back to their stable form or their native state. Even though the thermal channel can be decoupled from the excited state dynamics, it is more intuitive to test the electronic strong coupling modification of an opposing reaction that can lead to some knowledge of the equilibrium (fraction of Z-isomer) in the system.

In the spiropyran-merocyanine experiment, the excitation is done at the isosbestic point in the UV region, and this high-energy pumping is efficient due to the availability of a high transmission window for Ag mirrors5. Similar to this experiment, the effect of strong coupling on the photoisomerization kinetics of fulgide is also tested, where the forward rate is found to be accelerated under strong coupling. In the above case, the authors suggest that excited state symmetry is responsible for increased reaction rates9. In a different study, photoisomerization quantum yield is calculated for norbornadiene-quadricyclane photoswitches. Here, the photoisomerization quantum yield is similar for coupled and bare molecules when the upper polariton (UP) or the molecular transition is excited. However, the quantum yield conversion drops if the lower polaritonic (LP) state is excited8. This intriguing feature suggests a complex interplay of strong coupling that controls the excited state reaction dynamics. A polariton funneling mechanism is also explained in a recent experimental observation10. In the current system, we are trying to couple both the E and Z-isomers of a molecule to a cavity photon and test the photoisomerization process. What if both the isomers are coupled to a cavity? Shall we understand the signature of light-matter interactions by closely observing the system while evolving from strong to weak coupling regime?

Results

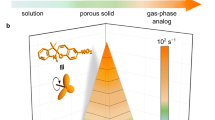

Here, we selected (E)-1-methyl-2-((2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)-1H-pyrrole (hereafter mentioned as azopyrrole) photoswitch—it is an unsymmetrical, push-pull type, and heteroazoarene-based photoswitchable molecular system (Fig. 1a)30. This thermodynamically stable E isomer can be converted into its metastable Z isomer upon photo-irradiation. The metastable Z isomer can be converted back to the E isomer thermally with a half-life of approximately five minutes in the solution phase. In agreement with previous studies mentioned in the introduction, we found that the strongly coupled states slow down the photoisomerization rate. However, while moving from strong to weak coupling, the isomerization rate shoots up and becomes double at weakly coupled conditions while exciting at the UP and dark state (DS) manifolds. Whereas the situation is exactly the opposite when pumping at the LP state. Interestingly, there is a sudden change around the transition from strong to weak coupling regime. We complement this study with theoretical estimates for the modification of the potential energy surfaces as well as simple models based on state overlap functions, further detailed in the following sections.

a Molecular structure and photoisomerization reaction of azopyrrole; b absorption spectra of E and Z-isomers of azopyrrole derivative in a polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) matrix; c Schematic of energy diagram showing the collective coupling of E and Z-isomers with a cavity mode and the collapse of Rabi splitting energy upon irradiation. Dark states are also shown for clarity. (The relative population difference in E and Z-isomers is exaggerated).

Azopyrrole system shows notable advantages over conventional photoswitches. These molecules have a larger separation between π−π*and n−π* transitions, and hence, the mixing of orbitals is less compared to azobenzene. However, the presence of an electron donor pyrrolidine ring at the ortho position to the azo unit led to longer wavelength strong absorption in the n−π* region due to intense charge transfer in the system. Figure 1b shows the absorption spectrum of the E and Z-isomers. E-azopyrrole has two prominent bands, one at 362 nm due to π−π* transition and a broad n−π* transition with λmax at 490 and 520 nm. We can clearly observe a hump in the broadband absorption spectrum, which can possibly be due to the presence of different conformers. Additionally, the n-π* transition is much more intense than π-π*, making it a visible light photoswitch. This is due to better overlapping of the n and π* orbitals and charge transfer in the system due to the loss of planarity, making the transition intense31,32. The extinction coefficient of E isomer n-π* and π-π* transitions are calculated in the toluene solution and found to be 12605 M–1cm–1 and 7995 M–1cm–1, respectively.

Interestingly, the n-π* transition/CT band for both E and Z isomers has the same energy but different extinction coefficients; thus, we could couple both the isomers cooperatively to the cavity. The overlapping of the absorption band of the n-π* transition makes it an ideal system for testing the effect of strong and weak light-matter coupling on the reaction rates. It is noteworthy to mention that all the strong coupling experiments studied till now involve photoswitches where bond breaking is involved. Whereas, in the current system, there is no bond breaking; instead, the C-N = N-C part of the molecule lies on an inversion/rotation/distortion coordinate that controls the E/Z photoisomerization. Figure 1c depicts the on-the-go change in the Rabi splitting/DS population when it undergoes photoisomerization. Both E and Z-isomers are cooperatively coupled to the cavity mode due to the fact that they absorb at the same wavelength and give two polaritonic states separated by Rabi splitting energy. Considering the difference in the extinction coefficient between the E and the Z-isomers, upon photoirradiation, a large decrease in the absorption was observed at the n-π* transition, leading to an effective drop in Rabi splitting. After a certain time interval, the system undergoes transitions from the strong to weak coupling domain, which can be closely monitored, through which its impact on the photoisomerization process under such conditions can be realized.

After optimizing the spectral features during the photoisomerization of the non-cavity system, we moved into the fabrication of cavity structures. For film preparation, a toluene solution was prepared with 1% azopyrrole and 2% PMMA (w/w) as the final concentration. This freshly prepared solution is spin-coated on an optically clean glass substrate. Further, 30 nm Ag mirrors are sputtered, and the sandwiched configuration forms the Fabry-Perot cavity. Here, the Fabry-Perot cavity is one of the simplest representations of a QED reactor and from now onwards referred to as a quantum flask. The quality factor of the cavity is determined to check the dephasing rate, and it is found to be ~ 15. Next, we compared the Rabi splitting energy with the FWHM of the absorption spectrum of the molecule to ensure that the system is strongly coupled at t = 0. At this condition, only the E-isomer is present, and the initial Rabi splitting energy is purely dependent on the concentration of this isomer. Figure 2a shows the temporal evolution of polaritonic states with 490 nm photoirradiation at a regular time interval of 10 s up to 220 s. The Rabi splitting energy is with 550 meV (t = 0) greater than the FWHM of the molecule (450 meV) and the empty cavity mode (Fig. S2). To check the kinetics of photoisomerization, both cavity and non-cavity samples were irradiated at absorption maxima of the molecule (490 nm), as well as near the UP (450 nm) and LP positions. As photoisomerization takes place from the E to Z-isomer, a decrease in the transition probability of the n−π* band takes place, leading to a reduction in the coupling strength. Thus, UP and LP states start moving towards each other, collapsing the Rabi splitting, and pushing the system into the weak coupling regime. Figure 2b–d illustrates the reaction kinetics of photoisomerization of azopyrrole inside the cavity and its comparison with the non-cavity. The kinetics is estimated by measuring the absorbance at different time intervals and when the equilibrium is reached, i.e., A∞ (Eq.( 1)). The first absorbance value inside the cavity (A0) and the empty cavity mode position (ωc) are calculated using transfer matrix simulation (TMM). Here, we have taken ωc as a fixed value during the course of the reaction, assuming that there is no change in the background refractive index (Δn = 0.03) of the thin film upon photoirradiation. Absorbance values at different time intervals are calculated from their direct relation with Rabi splitting energy as per Eq.(2)8.

At 450 nm excitation and under standard conditions (non-cavity), the apparent rate is estimated to be 1.24 × 10–2 ± 0.10 × 10–2 s–1 (Fig. 2b). Within the cavity, we identify two slopes that clearly indicate an increase in the reaction rate when the system transitions from the strong to weak coupling regime. Initially, when azopyrrole is under strong coupling, it follows the first-order kinetics with a rate constant of 2.93 × 10–2 ± 0.63 × 10–2 s–1. When the system enters the weak coupling regime, a new first-order curve is observed with an apparent rate of 5.15 × 10–2 ± 0.77 × 10–2 s–1. This transition is also indicated by the reduced Rabi splitting of 428 meV at 30 s, which is now less than the FWHM of the molecule. The same abrupt transition in the isomerization rate is observed when excited at 490 nm (Fig. 2c). Here, A∞ is taken as 100 s for clear visualization of the two slopes. In stark contrast, photoirradiation at the LP position results in the opposite trend, nearly cutting the rate in half at 80 s (Fig. 2d). The effect of ESC on the thermal return channels is less prominent as shown in Fig. S5. These marginal changes are due to the differences in the fraction of Z-isomer in the cavity and non-cavity conditions. Further, the fraction of Z-isomer was approximated by taking the ratio of the absorption maximum at 490 nm of the n → π* transition, and the initial E-isomer thin film absorption ratio, and further subtracting it from unity33. This is done for different conditions of pump excitation and found to show an overall increase in cavity system (Fig. S8).

a Temporal evolution of E to Z-isomer conversion of azopyrrole (1 w% in a PMMA matrix) inside the cavity upon photoirradiation with 490 nm LED source; dashed-dot line represents the absorption of E-isomer at t = 0 (dashed pink line is marked at the absorption maximum). Comparison of photoisomerization reaction kinetics of non-cavity (orange dot) with ON-resonance cavity (black dot) by pumping at b 450 nm, c 490 nm, and d LP (553 nm) excitation energies. Strong (green shade) and weak coupling regimes are demarcated as measured by the absorption linewidth of the molecular band. The theoretical spectral overlap for the time-dependent evolution of polaritonic state e with the uncoupled molecular line shape (D is the DS overlap), and f with the light source (E is the excitation overlap) for three different excitations (at 450, 490, and 553 nm). Changes in the DS overlap (e) at 30 s (for 450 and 490 nm) and 80 s (553 nm) are qualitatively consistent with the experimentally observed rate changes from strong to weak coupling.

A key observation is that the sudden change in reaction rate, moving from strong to weak coupling, depends on the excitation energy. Especially puzzling, existing theoretical models based on modified potential energy surfaces would not explain the sudden reduction in rate when exciting the LP state, but would suggest rate enhancement, thus calling a widely used concept in question15,16,34,35. One possible alternative mechanism would involve a fast relaxation from the delocalized bright state into the DS manifold with subsequent localization of the excitation on a single molecule that results in the isomerization reaction, as suggested by Dutta A. et al. in a recent article12. Following this hypothetical mechanism, the isomerization rate in the cavity is then dominated by the spectral overlap between the time-dependent optical spectrum (excited polaritonic states) and the dark state manifold located at the original maximum of the bare absorption spectrum—essentially enforcing energy conservation for transmission into the DS. We approximate this DS overlap by integrating the overlap of the transmission spectrum of the polaritonic state evolution with the uncoupled molecular line shape of the E-isomer absorption spectrum at t = 0. Further fitting the changes of the overlap integral on a first-order kinetic equation is found to be consistent with the experimentally observed reaction rate. This also reproduces the transition between strong and weak coupling regimes. All the calculation details are given in the SI (Section 8). Here, UP and LP states show the opposite trends, which is exactly reproduced in the DS overlap correlation (Fig. 2e). Calculating the excitation overlap, i.e., the spectral overlap between the pump source and dynamic absorption spectrum, shows inconsistencies with the observed trend in the experimental reaction rate (Fig. 2f). This disqualifies such trivial explanations and hints at a mechanism mediated by strong coupling that goes beyond absorption matching.

In order to get a clear picture of the role of the DS and its influence on the reaction rate, we further checked the USC regime. Here, we increased the concentration of the azopyrrole molecules in the cavity and non-cavity by preparing 1.5% azopyrrole and 1.5% PMMA (w/w) in toluene. Rabi splitting energy of 626 meV (a change of >20% of the fundamental transition energy of the molecule) was obtained at t = 0, defacto moving the system into the USC domain. Figure 3a shows the evolution of UP and LP states in the USC cavity. Back focal spectroscopy is done for the USC sample, and the LP state is dispersing and is further fitted using TMM simulation. The green, blue, and red dots in Fig. 3b represent the excitation position at the normal incidence of the cavity. Back focal imaging setup is limited in the spectral window, and hence, the information on the high-energy UP state cannot be obtained. As per the dispersion plot, there is less optically active population at the uncoupled molecular position (ω0), resulting in a reduced DS overlap. Specifically, the DS overlap at t = 0 reduces in USC for LP by 22%, UP by 53%, and 490 nm by 54%. Contrary to the previous case, the system never transitions into the weak coupling domain, giving rise to a single decay rate for the entire measurement time (Fig. 3c). Even after 100 s of photoirradiation, the Rabi splitting is found to be 484 meV, which is greater than the FWHM of the molecule. This indicates that the reaction rate is drastically slowed down under ESC and it is clearly visible from the temporal plot (Fig. 3c). The reaction rate is calculated using Eqs.( 1) and (2). Exciting UP or 490 nm results in a reduced rate compared to the non-cavity, with a notable resonance dependence. In contrast to the previous excitation energies, the bare spectrum features vanishing oscillator strength above 550 nm, resulting in slow photoisomerization in the non-cavity. ON-resonance (red) and OFF-resonance (blue) cavities show almost similar trends due to the funnelling of low-energy photons more effectively into the photoisomerization process. The resonance dependence is further discussed in the next session. DS overlap (Fig. 3d) provides again a consistent figure of merit for the experimentally observed reaction rate.

a Temporal evolution spectra of E to Z conversion of azopyrrole (1.5 w% in a PMMA matrix) inside the cavity upon irradiation with 490 nm LED source (dashed pink line; taken at the absorption maximum). b Experimentally measured dispersion plot of the ultra-strong coupled system using back-focal microspectroscopy. The black dashed line represents the absorption maximum of the E and Z-isomers. The dashed line represents the corresponding TMM fitting of the empty cavity mode (red) and lower polaritonic state (blue). Excitation positions are represented as green (UP) and pink (LP) (Outline: blue and red corresponding to ON- and OFF-resonance cavity, respectively.) c Comparison of photoisomerization reaction kinetics of non-cavity (orange dot), ON-resonance (red dot), and OFF-resonance cavities (blue dot) by pumping at 450 nm (first panel), 490 nm (middle panel), and d LP excitation energies (lower panel). The theoretical spectral overlap for the time-dependent evolution of polaritonic state d with the uncoupled molecular line shape (D is the DS overlap), and e with the light source (E is the excitation overlap) for three different excitations (at 450, 490, and 565 nm).

Tuning experiments are done by changing the thickness of the cavity, and, in turn, cavity mode position and reaction kinetics are plotted versus the empty cavity mode position (calculated from TMM), as shown in Fig. 4. Several experiments were conducted in and around the absorption envelope, and it was found that the rate changes follow the same line shape as the absorber molecules. Excitation at 490 nm gives the kinetic action spectra of the forward photoisomerization process, and when the system is at ON-resonance, the reaction rate decreases drastically. The non-cavity rate constant is estimated to be 2.09 × 10–2 ± 0.09 × 10–2 s–1, and the cavity effect is getting muffled at OFF-resonance conditions. Photoexcitation at 450 nm also gives a similar signature (Fig. 4a). Here, the FWHM was estimated between 455 and 545 nm. Altogether, tuning the cavity mode under ultra-strong coupling conditions shows an overall decrease in photoisomerization kinetics when exciting at the UP and ω0. In contrast, the LP state behaves exactly the opposite.

Kinetic action spectra of azopyrrole forward switching inside the cavity with varying mode position while pumping at a 450 nm and b 490 nm excitations, respectively. Non-cavity apparent rates are shown by the shaded green region. The transmission line shape of the azopyrrole molecule is given as a guide to the eye. Red and blue-circled data points represent the ON- and OFF-resonance reaction rates, which are shown in Fig. 3. Each cavity is prepared independently, and the standard errors are calculated for those points in which the empty mode overlaps within 3 nm of λ/2 cavity mode position.

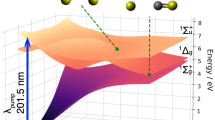

Let us refine our understanding by taking a closer look at potential rate control via cavity- modified potential energy surfaces. We perform time-dependent density-functional theory (TDDFT) calculations with the ORCA5.0 quantum chemical code36 by scanning C-N = N-C dihedral and N = N-C angle with constrained geometry optimization using the CAM-B3LYP functional37, including the toluene solvent implicitly38, and a def2-TZVPD basis. Based on those geometries, we then calculate the ground and excited state potential energy landscape (PES). The absorption spectrum of the E isomer is shown as gray lines in Fig. 5 with a sizeable blueshift compared to the experimental measurements. Collective coupling between the ground and the i’th excited state is mediated by the coupling elements

where \(\bar{{{{\boldsymbol{\mu }}}}_{{{\boldsymbol{i}}}}}\) is the angular average of the transition dipole moment to the i’th excited state and \({N}_{E/Z}^{\left(C\right){NNC}}={e}^{-{\left({R}_{\left(C\right){NNC}}-{R}_{E/Z}\right)}^{2}/{\sigma }^{2}}/\sqrt{{{2}}{{\pi }}{\sigma }^{{{\boldsymbol{2}}}}}\) is a Gaussian distribution represented in the (C)N = N-C angles around the E (red dot and cross) and Z (green dot and cross) isomer with standard deviation in the respective angles of σ = 20 degree. This is a simplified model for the expected number of molecules participating in the collective interaction for a given configuration, i.e., the further away from E and Z isomers, the fewer molecules can contribute to the cavity potential energy surface (cPES) and the weaker its impact on the isomerization process. Please note that dark-state surfaces are not considered in this model. A matrix including 9 excited states plus an idealized loss-less cavity mode is then diagonalized to obtain the cPES34 shown on the right-hand side of Fig. 5. Isomerization of the E isomer into the Z isomer can take different paths, which can be characterized by either: (i) performing a CNNC inversion, e.g. using excess energy to overcome the S1 barrier (red dots on S1 in Fig. 5a–f), or (ii) a barrier-less CNNC dihedral rotation (blue diamonds on S1 in Fig. 5a–f) via the S1-S0 CI from where relaxation to E and Z isomer is possible. As E and Z-isomer absorb the pump energy, the reverse process from Z to E-isomer, e.g., following pathway (i), results in the convergence towards equilibrium under constant illumination.

Represent modified polaritonic surfaces for {g/ωR = a) 0.0543, b) 0.1086, c) 0.1257} that result in the experimentally observed Rabi splitting ranging from weak (a; 1 w% azopyrrole; at equilibrium), over strong (b; 1 w% azopyrrole), to ultra-strong (c; 1.5w% azopyrrole) for a frequency of the cavity mode chosen to be in resonance with the theoretically predicted absorption energy S0 to S1 of 427 nm. d–f Transition-state barriers for different reaction paths on the S1 (lower polariton) surface of the combined system with the absorption spectrum of the bare system as a gray line in the background. Higher transparency of a data point corresponds to a smaller matter contribution, i.e., a higher photonic fraction of the polariton.

Longer wavelengths, i.e., large red-detuning, will formally increase the splitting between S2 and S1 at the loss of hybridization between light and matter. In other words, the S1 surface continues to red-shift but turns into an effective photon replica of the ground-state S0 surface without notable light-matter hybridization at the isomer. Hybridization appears now further away from the E/Z isomers, practically enhancing the S0 “pocket” in which optically excited molecules could be trapped, ultimately reducing the isomerization rate. This essentially linear increase in cavity-induced barriers for increasing wavelengths (Fig. 5d–f) is consistent with the experimental action spectra shown in Fig. 4.

Discussion

To get clarity on the overall data, the photoisomerization apparent rate per power density of the irradiation source is calculated for both concentrations (Table 1). Here, the ON-resonance cavity refers to the average of all the cavities that lie within the FWHM of the molecular absorption band. In the case of a strongly coupled system, the rate increases both at UP and 490 nm excitations. Whereas, in the case of LP excitation, only an initial increase can be observed within the strong coupling regime. Further, upon entering the weak coupling regime, the system goes back to the non-cavity rate. Non-cavity data somewhat follows the absorption profile as a maximum rate per power density is obtained at 490 nm excitation. Here, the LP state lies close to 550 nm, where the extinction coefficient is quite low; thus, less photoswitching is observed in a non-cavity.

The dark-state overlap serves as a remarkably consistent figure of merit for the observed rate changes (Figs. 2, 3). Not only for the transition between strong and weak coupling, but even for the relative size of the rates between ultra-strong and strong coupling. This suggests that dark-state mediated relaxation processes dominate over cavity-induced modifications of the PES, at least near the transition from strong to weak coupling. It is important to note that thermal disorder present in our system limits the degree of delocalization via polaritonic states12,39. A decreasing Rabi splitting results in an increased spectral overlap between bright and dark states that will increasingly localize excitation. At the transition from strong to weak coupling, delocalization will rapidly disappear, which results in a sudden switch in the reaction rate. The weak coupling domain is likely dominated by Purcell-enhanced absorption, where ‘polaritonic’ peaks act as an absorption filter for the bare molecules. Purcell enhanced absorption might explain an overall increase in reactivity in the weak coupling domain. However, the distinctly reduced rate when exciting the lower polaritonic state (Table 1), despite this energy window featuring the largest absorbance (see SI; Figs. S10, S11), contradicts such an interpretation. It should be noted that azopyrrole is non-emissive, i.e., a reduced rate via enhanced emission from the lower polaritonic state cannot explain this effect.

Next, we compared the apparent rate average for the USC regime for all the above excitation conditions. Here, both UP and 490 nm excitations show a decrease in the reaction rate. This decrement is more prominent if the ON-resonance cavity is at 490 nm. However, LP excitation is exactly the opposite, and the apparent rate per power density is ~ 2.5 times more than the non-cavity. Comparing the rate per power density for non-cavity at LP excitation, the values are lower in the case of USC conditions because here, the LP state is more red-shifted (>560 nm), where the transition probability of the uncoupled molecule is almost nil. At USC, cavity-modified potential-energy surfaces suggest a strong rate inhibition by trapping molecules in a dip of the S1 surface near the E/Z isomers (Fig. 5). The associated enthalpic barriers increase almost monotonously (in the investigated domain) with increasing wavelengths, which is consistent with the experimental action spectrum (Fig. 4), and therefore can be suggested as a plausible mechanism for rate modification in the ultra-strong coupling domain.

Conclusion

Electronic strong coupling can control photoisomerization processes as it involves an excited state process. Normally, photoconversion rates depend on the concentration of isomers and the photon flux. Here, by varying the collective coupling strength of the E and Z-isomers of the azopyrrole cooperatively, we have demonstrated the importance of strong coupling in funnelling optical absorption via the DS population in a photoisomerization reaction. Many factors control the kinetic rates, including the PES, the DS, and the excitation overlap of the collectively coupled system. In the present study, each of the parameters is estimated and compared. However, DS overlap seems to play a major role in this reaction under collective strong coupling. A very interesting observation is a complete rate modification upon strong-to-weak coupling transition in an on-the-go reaction. DS overlap provides an excellent figure of merit for those transitions, which is otherwise not evident from cavity-modified PES. We mapped excitation dependence reaction rates at both bright states and DS and clearly correlated them with available field distribution and overlap functions. In short, the optical strength of a number of molecules exchanging energy coherently via the cavity mode (strong coupling) acts as an antenna for any incoming optical drive. Excitation energy is then funnelled from the polaritonic states into the DS manifold (or gray states), where the isomerization proceeds as usual. The spectral overlap between polaritonic states and dark/gray states plays, conceptually, an equivalent role to the strong resonance dependence of Förster resonant energy transfer, but is now distributed over the participating molecules. Our observation emphasizes the role of DS spectral overlap, besides their visual absence, remains an integral part of cavity photochemistry. Surely, this conclusion is limited to the collective strong coupling regime. Additional measurements and theoretical investigations in the USC domain highlight that cavity-induced modifications of the PES remain a possible explanation under more extreme conditions. Further studies will be necessary to draw a comprehensive picture of the relative importance of DS-mediated relaxation, Purcell enhanced absorption, and modified reactivity via cPES. In this work, we have identified the dynamic transition between two coupling domains as a potentially critical tool in the understanding of the fundamental mechanisms behind cavity-modified reactivity, preparing the ground for a leap to building a comprehensive understanding of QED chemistry.

Methods

Solution preparation

(E)-1-Methyl-2-((2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)phenyl)diazenyl)-1H-pyrrole (termed as azopyrrole) was synthesised, and the structure and purity of the compound were confirmed by NMR spectroscopy30. Poly-methyl methacrylate (PMMA) and electronic grade toluene were bought from Merck Inc. and used as it is. For making solid samples, azopyrrole and PMMA were dissolved in toluene separately and then mixed together to get a good-quality thin film. Different w/w concentration solutions of Azopyrrole and PMMA were prepared to obtain the desired thickness of the film. For strong coupling experiments 3% Azopyrrole and 3% PMMA were dissolved in toluene and stirred for 4–5 h to ensure complete dissolution. Later on, the azopyrrole solution was filtered using a PTFE syringe filter (pore size: 0.22 μm) and was mixed with 3% PMMA solution in a 1:1 (v/v) proportion to get the resultant solution of concentration 1.5% Azopyrrole and 1.5% PMMA in toluene. Similarly, 1% Azopyrrole and 2% PMMA in Toluene solution was prepared when the splitting energy was less. However, the system was still in strong coupling at the start and eventually entered a weak coupling regime with irradiation.

Cavity preparation

Glass substrates were cut into 2.5 × 2.5 cm size and sonicated in a solution of Hellmanex concentrate and distilled water for 8 min. After cleaning the substrates with distilled water, glass substrates were sonicated in ethanol for 1 h. Then, the substrates were cleaned with distilled water and dried in an oven for at least 12 h. These clean glass substrates were then used to make cavity and non-cavity structures. For non-cavity, a solution of azopyrrole and PMMA was spin-coated (LABSPIN 6, Suss-Microtech) on the glass substrate. Meanwhile, 30 nm silver is sputtered on the glass substrates for cavity formation using the Hind-High Vac (BT300) sputter coater before and after spin coating the azopyrrole solution to get a Fabry-Pérot cavity configuration. To observe the effect of strong coupling, the cavity thickness was varied by varying the rotation speed of spin coating from 800 to 3000 rpm.

Photoisomerization of azopyrrole

The cavity and non-cavity were irradiated with three wavelengths to study the effect of ESC on reaction kinetics. Once the samples were excited at the molecular absorption maxima of 490 nm, and in another cycle, they were irradiated close to the upper polariton position at 450 nm. Similarly, excitation was done at lower polariton position as well. For cavity as well as non-cavity, excitation was performed from the glass side. Before irradiating the samples, the power of the light was measured every time using the Newport Model 843-R Power Meter. For analysing E to Z photoisomerization and thermal return from Z to E azopyrrole, Perkin Elmar Lambda 465 was used. The forward switching rate was monitored by irradiating the sample for 10 s and then recording its UV spectra, and this was done several times to extract the kinetics of photoisomerization. After this, the sample was allowed to return to the E isomer, and backward switching kinetics were observed for both cavity and non-cavity samples.

Data availability

All the raw data are available in the following repository with https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15607450.

References

Frei, H., Fredin, L. & Pimentel, G. C. Vibrational excitation of ozone and molecular fluorine reactions in cryogenic matrices. J. Chem. Phys. 74, 397–411 (1980).

Frei, H. & Pimentel, G. C. Selective vibrational excitation of the ethylene-fluorine reaction in a nitrogen matrix. I. J. Chem. Phys. 78, 3698–3712 (1983).

Brumer, P. & Shapiro, M. Chemistry: Controlling chemical reactions with lasers. Acc. Chem. Res. 22, 407–413 (1989).

Schwartz, T., Hutchison, J. A., Genet, C. & Ebbesen, T. W. Reversible switching of ultrastrong light-molecule coupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 196405 (2011).

Hutchison, J. A., Schwartz, T., Genet, C., Devaux, E. & Ebbesen, T. W. Modifying chemical landscapes by coupling to vacuum fields. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 1592–1596 (2012).

Ebbesen, T. W. Hybrid light-matter states in a molecular and material science perspective. Acc. Chem. Res 49, 2403–2412 (2016).

Hertzog, M., Wang, M., Mony, J. & Börjesson, K. Strong light–matter interactions: A new direction within chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 937–961 (2019).

Mony, J. et al. Photoisomerization efficiency of a solar thermal fuel in the strong coupling regime. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2100737 (2021).

Zeng, H. et al. Control of photoswitching kinetics with strong light-matter coupling in a cavity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 19655–19661 (2023).

Lee, I., Melton, S. R., Xu, D. & Delor, M. Controlling molecular photoisomerization in photonic cavities through polariton funneling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 9544–9553 (2024).

Puro, R. et al. Exciton polariton-enhanced photodimerization of functionalized tetracene. J. Phys. Chem. C. 125, 27072–27083 (2021).

Dutta, A. et al. Thermal disorder prevents the suppression of ultra-fast photochemistry in the strong light-matter coupling regime. Nat. Commun. 15, 6600 (2024).

Thomas, P. A., Tan, W. J., Kravets, V. G., Grigorenko, A. N. & Barnes, W. L. Non-Polaritonic Effects in Cavity-Modified Photochemistry. Adv. Mater. 36, 2309393 (2024).

Schwartz, T. & Hutchison, J. A. On the importance of experimental details: A Comment on” Non-Polaritonic Effects in Cavity-Modified Photochemistry”. Adv. Mater. 37, 2404602 (2025).

Galego, J., Garcia-Vidal, F. J. & Feist, J. Suppressing photochemical reactions with quantized light fields. Nat. Commun. 7, 13841 (2016).

Ulusoy, I. S., Gomez, J. A. & Vendrell, O. Modifying the nonradiative decay dynamics through conical intersections via collective coupling to a cavity mode. J. Phys. Chem. A 123, 8832–8844 (2019).

Mandal, A. & Huo, P. Investigating new reactivities enabled by polariton photochemistry. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 5519–5529 (2019).

Fregoni, J., Granucci, G., Coccia, E., Persico, M. & Corni, S. Manipulating azobenzene photoisomerization through strong light-molecule coupling. Nat. Commun. 9, 4688 (2018).

Swaminathan, S., Bera, J. K. & Chandra, M. Simultaneous harvesting of multiple hot holes via visible-light excitation of plasmonic gold nanospheres for selective oxidative bond scission of olefins to carbonyls. Angew. Chem. - Int. Ed. 62, e202215933 (2023).

Climent, C., Galego, J., Garcia-Vidal, F. J. & Feist, J. Plasmonic nanocavities enable self-induced electrostatic catalysis. Angew. Chem. 131, 8790–8794 (2019).

Shalabney, A. et al. Coherent coupling of molecular resonators with a microcavity mode. Nat. Commun. 6, 5981 (2015).

Thomas, A. et al. Ground-state chemical reactivity under vibrational coupling to the vacuum electromagnetic field. Angew. Chem. 128, 11634–11638 (2016).

Thomas, A. et al. Tilting a ground-state reactivity landscape by vibrational strong coupling. Science (1979) 363, 615–619 (2019).

Schäfer, C., Fojt, J., Lindgren, E. & Erhart, P. Machine learning for polaritonic chemistry: Accessing chemical kinetics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 5402–5413 (2024).

George, J. & Singh, J. Polaritonichemistry: Band-selective control of chemical reactions by vibrational strong coupling. ACS Catal. 13, 2631–2636 (2023).

Simpkins, B. S., Dunkelberger, A. D. & Vurgaftman, I. Control, modulation, and analytical descriptions of vibrational strong coupling. Chem. Rev. 123, 5020–5048 (2023).

Simpkins, B. S., Dunkelberger, A. D. & Owrutsky, J. C. Mode-specific chemistry through vibrational strong coupling (or a wish come true). J. Phys. Chem. C. 125, 19081–19087 (2021).

Dunkelberger, A. D., Simpkins, B. S., Vurgaftman, I. & Owrutsky, J. C. Vibration-cavity polariton chemistry and dynamics. Annu Rev. Phys. Chem. 73, 429–451 (2022).

Nagarajan, K., Thomas, A. & Ebbesen, T. W. Chemistry under vibrational strong coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 16877–16889 (2021).

Gaur, A. K. et al. Structure-property relationship for visible light bidirectional photoswitchable azoheteroarenes and thermal stability of Z-isomers. J. Org. Chem. 87, 6541–6551 (2022).

Kuntze, K. et al. Towards low-energy-light-driven bistable photoswitches: ortho-fluoroaminoazobenzenes. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 21, 159–173 (2022).

Sadovski, O., Beharry, A. A., Zhang, F. & Woolley, G. A. Spectral tuning of azobenzene photoswitches for biological applications. Angew. Chem. - Int. Ed. 48, 1484–1486 (2009).

Cho, E. N., Zhitomirsky, D., Han, G. G. D., Liu, Y. & Grossman, J. C. Molecularly engineered azobenzene derivatives for high energy density solid-state solar thermal fuels. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 9, 8679–8687 (2017).

Galego, J., Garcia-Vidal, F. J. & Feist, J. Cavity-induced modifications of molecular structure in the strong-coupling regime. Phys. Rev. X 5, 041022 (2015).

Schnappinger, T. & Kowalewski, M. Nonadiabatic wave packet dynamics with ab initio cavity-born-oppenheimer potential energy surfaces. J. Chem. Theory Comput 19, 460–471 (2023).

Neese, F. Software update: The ORCA program system—Version 5.0. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Comput Mol Sci 12, 1–15 (2022).

Yanai, T., Tew, D. P. & Handy, N. C. A new hybrid exchange-correlation functional using the Coulomb-attenuating method (CAM-B3LYP). Chem. Phys. Lett. 393, 51–57 (2004).

Cammi, R., Mennucci, B. & Tomasi, J. Fast evaluation of geometries and properties of excited molecules in solution: A Tamm-Dancoff model with application to 4-dimethylaminobenzonitrile. J. Phys. Chem. A 104, 5631–5637 (2000).

Liu, T., Yin, G. & Xiong, W. Unlocking delocalization: How much coupling strength is required to overcome energy disorder in molecular polaritons?. Chem. Sci. 16, 4676–4683 (2025).

Acknowledgements

P. G. thank UGC-CSIR, J. S. thank SPM-CSIR, A. K. G thank IISER Mohali for the PhD fellowships. J.G. thank DCS, and IISER Mohali for the use of the infrastructure facility. J. G. thank the SERB-core research grant (CRG/2023/001122), S. V. thank SERB-core research grant (CRG/2023/003861), and DCS, IISER Mohali for the instrument facilities. C. S. thank the European Union under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No. 101065117.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.G. conceptualized the project and secured funding. C.S. performed the TD-DFT calculations, computed the overlap integrals, and contributed significantly to the interpretation of the results. S.V. provided the molecule for study and offered valuable suggestions throughout the work. P.G. carried out all experiments and performed the TMM calculations. J.S. assisted with the conceptual understanding of the system and the setup of the experimental apparatus. A.K.G. synthesized the molecule used in the experiments. The manuscript was written by J.G., C.S., and P.G., with input from all authors. All authors reviewed, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Garg, P., Singh, J., Gaur, A.K. et al. Unveiling the role of dark states in dynamic control of azopyrrole photoisomerization by light-matter interaction. Commun Chem 8, 192 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01588-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01588-x