Abstract

Although a trimerized ground state has been predicted for LiVO2 for over half a century, the direct determination of its crystal structure in the trimerized phase by X-ray diffraction remains elusive. Depending on the cooling process, two distinct structural modifications have been prepared - LiVO2 with streak-like, smeared-out superstructure reflection intensities and Li0.91VO2 with well-separated superstructure reflection intensities. The discovery of well-separated superstructure reflections in Li0.91VO2 enabled us to solve its crystal structure. This motivated us to attribute the streak-like superstructure reflection intensities in LiVO2 to an overlap of reflections due to a unit cell doubling along the c-axis, which contrasts with the previous interpretation of randomly stacked V trimer layers. The availability of the crystal structure data forms a starting point for the quantitative modeling of the trimerization phenomenon in this complex Mott insulator.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

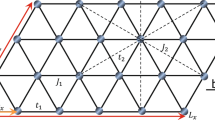

The triangular lattice system LiVO2 remains an enigmatic material although it has been synthesized already more than 70 years ago1. Earlier studies reveal that LiVO2 undergoes a structural phase transition at about 463 K2. The high-temperature phase adopts a rhombohedral structure with space group \(R\bar{3}m\), resembling a derivative of the rock-salt structure, where the (1 1 1) planes are alternatingly occupied by either Li or V ions. Despite numerous structural studies2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20, the exact nature of the low-temperature structure remains unsolved. Since the phase transition coincides with a sudden disappearance of the paramagnetic susceptibility signal2, it was proposed that nonmagnetic V trimers form in the low-temperature phase5. Resistivity measurements have shown that the first-order phase transition is not a conventional metal-to-insulator transition but rather an insulator-to-insulator transition4,6,8,14. The “Mottness” of LiVO2 complicates interpretations based on a standard Peierls type transition, and a consensus on a quantitative theoretical model has yet to be reached10,21,22,23,24,25,26.

Indications for the existence of non-magnetic trimers in LiVO2 have been gathered from various experimental techniques. NMR studies have culminated in the observation of an orbital reconstruction with threefold rotational symmetry in the low-temperature phase12,15,16,25,27. X-ray absorption fine structure and pair distribution function (PDF) analyzes have revealed peak splitting associated with the different V–V distances13,16, supporting the presence of trimers. X-ray diffraction (XRD) and electron diffraction studies have reported third-integer superstructure reflections (1/3 1/3 L) which appear as diffuse streaks along the c*-direction7,8,9,11,12,13,14,16. A more recent PDF study using powder XRD suggests that the vanadium trimers are periodically ordered within each ab-plane, but that these ordered planes are randomly stacked along the c-axis direction18. Interestingly, a subsequent study19 reported a Li-deficient sample in which powder XRD measurements suggested indications for short-range order in the c-direction. However, the crystal structure could not be solved, and no follow-up studies using the more informative single crystal XRD were conducted. Likewise, no further reports used these findings to resolve the crystal structure of stoichiometric LiVO2.

Here, we report single-crystal XRD measurements on two Li1−xVO2 crystals, each representing a different low-temperature modification. One crystal, LiVO2, exhibits smeared-out, streak-like superstructure reflection intensities, while the other, Li0.91VO2, shows well-separated reflections that are broadened along the c*-axis. The presence of well-separated reflections in the latter allowed us to determine its crystal structure. This finding enabled us to reinterpret the streak-like superstructure reflections in our LiVO2 sample, attributing them to a unit cell doubling along the c-axis, rather than a random stacking of vanadium trimer layers. A structural model for LiVO2 was also developed, which provides a reasonable fit to the XRD data despite superstructure reflection overlap and disorder. We note that the correlation length of each reflection in the c-direction is similar for both structural modifications, and that their structural relationship suggests that Li1−xVO2 is a polytypic compound.

Results and discussion

As described in the “Methods” section, we successfully synthesized Li1−xVO2 single crystals using an optimized flux growth method and tuned the Li content by utilizing different cooling rates during the synthesis. Photos of two single crystals are shown in Fig. 1a. The cooling rate was 10 K/h for LiVO2, and 5 K/h for Li0.91VO2, and the Li content was determined by comparing and calibrating the measured c/a ratios with literature values for the Li1−xVO2 system20. The Li content of Li0.91VO2 was also determined by refinements of the Li/V content in single crystal XRD measurements as is discussed below in detail. Representative X-ray scattering intensities are shown in Fig. 1b, c. The stoichiometry of the full LiVO2 compound was confirmed by soft X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) measurements at the V L2,3 edges (510–527 eV) and at the O K edge (527–537 eV), as shown in Fig. 2. The distinct line shapes clearly differentiate the V3+ spectrum of LiVO2 from the V4+ spectrum of VO2. Notably, the LiVO2 spectrum shows no indications of V4+ species.

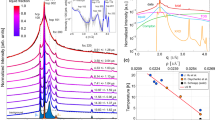

a As-grown Li1−xVO2 single crystals: LiVO2 (left) and Li0.91VO2 (right). b X-ray scattering intensities in the (h0l) plane of reciprocal space measured by means of single crystal X-ray diffraction on LiVO2 (left) and Li0.91VO2 (right). Here, a unit cell doubling in c-direction has been already considered for the panel of LiVO2. (Unphysical narrow peaks of one or two detector pixels solely are due to detector noise/stingers/cosmic radiation and have been partly removed). c X-ray scattering intensities in the (hk0) plane of reciprocal space for LiVO2 (left) and Li0.91VO2 (right).

XAS spectra of LiVO2 at the V L2,3 edges (510–527 eV) and at the O K edge (527–537 eV). The black curve shows the spectrum of our full LiVO2 compound. The red curve is that of VO2. In the inset (green box), we focus on the pre-edge region of the O K edge. While VO2 (V4+) has its main peak at 528.6 eV, LiVO2 has there its minimum intensity.

Single crystal XRD intensities within the (h0l) plane of reciprocal space are shown for both samples in Fig. 3a, b. For LiVO2 a streak-like intensity distribution in c*-direction is observed, see Fig. 3a, consistent with previous reports in literature18. At first glance this pattern suggests a rather high degree of disorder or that the “vanadium trimers are randomly aligned along the c-axis”18. Such a diffuse diffraction pattern poses a significant challenge in solving the underlying crystal structure.

X-ray scattering intensities in the (h0l) plane of reciprocal space measured by means of single crystal X-ray diffraction on (a, c) LiVO2 and (b, d) Li0.91VO2. The detector background offset amounts to 32 counts; the intensities for both compounds are presented on the same unit cell (without any doubling of c); intensity scale is plotted with a logarithmic color scheme. For the single crystal of Li0.91VO2, the superstructure reflections (at h = −4) are well-separated with peak intensities reaching the background level between two reflections. l-scans across the superstructure reflections at h = −4 are shown in (c) for LiVO2 (red circles) and in (d) for Li0.91VO2 (blue dots); brown line: detecor background offset. In (d), the light gray shaded area indicates a scan across the fundamental Bragg reflections (with intensities divided by 50) and solid lines indicate gaussian fits in order to obtain the peak widths (FWHM). In (c), the intensity difference of the intensities of the LiVO2 sample and of the intensities of the Li0.91VO2 sample weighted by 45% is shown. This suggests a doubling of the unit cell in c-direction for LiVO2 (see text).

In contrast, the other sample, Li0.91VO2, shows well-separated superstructure reflection intensities, as shown in Fig. 3b, which are exceptional for Li1−xVO2. Note that indications for the possible development of short-range order—depending on the cooling process—were also observed in literature19. Therein, a completely disordered Li1−xVO2 sample and a sample with indications for short-ranged correlations in the stacking were reported19. A closer look at the X-ray intensities of our LiVO2 sample along the (−40l)-direction in reciprocal space—see the curve with the red dots in Fig. 3c—reveals that the intensity remains high for all l values, while in Li0.91VO2 the intensities drop to the background level between the peaks—see the curve with the blue dots in Fig. 3d. This allows us to properly integrate these well-separated superstructure reflection intensities, enabling us to solve the crystal structure of Li0.91VO2, which is described below. Compared to the fundamental Bragg reflections, the superstructure reflections are nearly six times broader in the c*-direction, indicating the short-ranged nature of the stacking of vanadium layers in the c-direction.

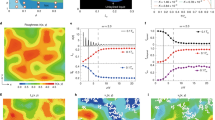

For solving the crystal structure, a total of 14,665 reflections were collected up to 2Θmax = 70.8°—see Supplementary Table S1. Apart from the triclinic and trigonal Laue symmetries (\(\bar{1}\), \(\bar{3}\) and \(\bar{3}1m\)), all other symmetries can be directly discarded due to extremely high Rint-values (>50%) as shown in Supplementary Table S5. (Note that in general, the highest symmetries that appear to be suitable from a comparison of Rint-values may not reflect the true crystal symmetries, e.g., due to twinning in the measured crystal that mimics these higher symmetries. The choice of the space group ultimately also depends on the R-values and stability of the structure refinements.) Especially, a structural model based on space group P31m with Laue symmetry \(\bar{3}1m\) (and with structural parameters taken from ref. 18) would result in R-/Rw-values of 50.67%/74.3% and a goodness of fit (GoF) of 7.37. The best structure solutions yielding the lowest GoF and R-values were achieved with trigonal space groups with point group \(\bar{3}\): i.e., P3, \(P\bar{3}\) and P31 (or P32). Among these, the best refinements were achieved with space group P31 (or P32). Notably, the experimentally observed extinction conditions of systematically absent reflections are also consistent with this space group, as shown in Fig. 1b (right). For reliability, we performed a refinement using only isotropic displacement parameters Uiso. Additionally, Uiso was constrained to the same value for each type of element—lithium, vanadium, and oxygen. For light lithium ions, a refinement of Uiso appears to be a natural choice. For oxygen, which is also relatively light and occupies multiple sites within the unit cell, this approach remains reasonable, especially given the complexity of the crystal structure. Since a vanadium site needs to be treated with a split-atom model (see below) and since the crystal exhibits twinning, it is also appropriate to use Uiso for the vanadium ions. Moreover, since all lithium and vanadium ions share a similar octahderal oxygen coordination, applying the same Uiso value for each element type is a reasonable choice. The crystals are twinned with a twin fraction of 49.972(23)% (~racemic mixture of P31 and P32). This twinning is probably a consequence of stacking faults and the limited correlation length of the stacking of the trimerized layers in the c-direction. In addition to this twinning, one of the trimerized vanadium ions, V3, can be found with a probability of 24.0(3)% at a site V3’ effectively flipping or mirroring the trimer to the other side, as shown in Fig. 4a–c. A split-atom model best accounts for this property, which may arise from additional disorder in the stacking of layers. The two different types of trimers are highlighted in Fig. 4a–c with solid lines (“regular” trimers with 76.0(3)% probability) or dashed lines (“flipped” trimers with 24.0(3)% probability). The introduction of the split-atom model for V3 significantly improved the GoF and R- / Rw-values. Otherwise, these values would increase to 2.44 and 8.96%/22.25% for I > 3σ(I) (and 11.09%/25.09% for all reflections). Flipping the trimers alters the stacking of adjacent vanadium layers, which is associated with a completely different kind of stacking fault, unrelated to twinning of P31 and P32. (But due to the twin law, the trimers are also modeled as being flipped in another direction.) In this case, where the trimers in one layer are “flipped” with a probability of 24.0(3)%, the trimers in two adjacent layers adopt a non-helical arrangement, with a 180° rotation (around c) between them. The superstructure reflections are elongated only in the c*-direction and remain sharp in perpendicular directions, indicating that the trimerized patterns are long-range ordered within the vanadium-oxygen planes. The effective lithium deficiency of Li0.91VO2 is best described with additional vanadium ions at the octahedrally coordinated Li sites which has been also reported in the literature for severely delithiated Li0.22VO228. Regarding the fact that the refinement only contains three displacement parameters, Uiso(Li), Uiso(V) and Uiso(O), and regarding the disorder in the stacking of layers (indicated by the enhanced detected peak widths in c*-direction), we consider the finally obtained R-values and GoF acceptable. The structural parameters are listed in Supplementary Table S2. Furthermore, our refinements yield a composition that is consistent with the composition of Li0.91VO2 derived from its lattice parameters, as determined by the study of lattice parameters and Li content using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry in literature20—the Li:V ratio amounts to 0.932(4) according to our structural refinement. This result is based on the refinement of the occupancy of the comparatively heaviest ions in the system—the V ions—within the Li-deficient layers, and not only on the occupancy refinement of the very light Li ions. The bond valence sums (BVS) for the Li ions are 1.08(1), 1.09(1) and 1.00(1) for Li1, Li2 and Li3, respectively. The BVS for the V ions amount to 2.96(2), 3.02(1) and 3.04(2) for V1, V2 and V3. These values underline the high reliability of our crystal structure refinement.

The crystal structure model used in the refinement of the single-crystal X-ray diffraction data of Li0.91VO2. Green/blue/gray spheres denote V-, O- and Li-ions; the yellow spheres indicate V-sites occupied with 24.0(3)% probability (V3' in a split-atom model). The “regular” V-trimers are indicated by thick solid lines and the “flipped” trimers involving the V3' ions are denoted by thick dashed lines. a Crystal structure with viewing direction parallel to the vanadium oxide layers A, B, and C. b Top view of the single vanadium oxide layer A. c Visualization how the trimers in vanadium oxide layers A, B, and C are stacked in c-direction. d A “regular” trimer together with a “flipped” trimer. The arrows pointing up (down) denote shifts of the oxygen ions that are situated directly over (below) the center of the “regular” (“flipped”) vanadium trimers that appear with a probability of 76.0(3)% (24.0(3)%).

The V-trimerization is evident from the shortening of the V–V intra-trimer bond lengths: the average intra-trimer V–V distance of 2.59(6) Å is distinctly smaller than the average inter-trimer distance of 2.98(7) Å. Although the stacking of the vanadium trimers is not fully long-range ordered and stacking faults are expected, as indicated by the broadness of the superstructure reflections, there appears to be a preferred stacking order in Li1−xVO2. It follows an ordering scheme that can be best described by space group P31. An illustration of how the presence of trimers in one layer affects the arrangement of trimers in adjacent vanadium layers is provided in Fig. 4d. One oxygen ion is situated above each “regular” trimer and one below each “flipped” trimer. Due to the short V–V distances within each trimer, these oxygen ions are displaced in the out-of-plane direction away from these trimers, as indicated by the arrows in the Fig. 4d. Thus, a potential is created to the adjacent Li oxide layers, and can propagate further along the c-direction to subsequent layers. Since no split-atom model was used for these oxygen ions, their differing out-of-plane shifts are a consequence of the probabilities of finding a trimer below/above these ions. In contrast to LiVS218, the Li oxide layers in Li1−xVO2 appear unable to fully transmit these distortions to the next V layer. This limitation could explain the short-ranged nature of the trimer layer stacking. Nevertheless, the stacking is not random and predominantly follows the symmetries of space group P31.

After solving the crystal structure of Li0.91VO2, a crystal structure solution for the LiVO2 sample with diffuse superstructure reflection intensities becomes feasible. As shown in Fig. 3c, the superstructure reflections are no longer centered anymore at multiples of three in the (-40l)-direction, as in the case of Li0.91VO2, compare Fig. 3d. Instead, these intensities appear at multiples of 3/2 in the (-40l)-direction. A closer inspection of the peak shapes suggests that the reflections in LiVO2 are not simply infinitely broad in the c*- direction; rather, the upper parts of these reflections resemble those of Li0.91VO2. This can be seen when comparing the red and the dark blue data points in Fig. 3c. A simple subtraction of the superstructure reflection intensities of Li0.91VO2 (weighted by 45%) from the corresponding intensities of LiVO2 yields an intensity difference (light blue data) that strongly resembles the superstructure reflection intensities in Li0.91VO2, including a very similar peak shape and width. The intensity difference shows peaks at L values that are multiples of 3/2 with similar peak widths as the superstructure reflections observed for Li0.91VO2. Our results suggest that the streaks for LiVO2 are not caused by a random stacking in the c-direction. Instead, the measured intensities for our sample can be interpreted as a superposition of superstructure reflections resulting from a unit cell doubling in the c-direction. And indeed, an integration of the XRD intensities in LiVO2 with a doubled c-lattice constant enabled us to find a structural model for this modification of Li1−xVO2 that describes the measured XRD intensities reasonably well. This structural model for LiVO2 strongly resembles the model found for Li0.91VO2, see Fig. 5a–c.

The crystal structure model used in the refinement of the single-crystal X-ray diffraction data of LiVO2. Green/blue/gray spheres denote vanadium, oxygen, and lithium ions; the yellow spheres indicate vanadium sites within a split-atom model that are occupied with 28.1(8)% probability. The vanadium trimers involving V3 are indicated by thick solid lines and the alternative trimers involving the V3' ions are denoted by thick dashed lines. a Crystal structure with viewing direction parallel to the vanadium oxide layers A, A', B, B', C, and C'. b Visualization of how the trimers in vanadium oxide layers A, B & C are stacked in c-direction. c Visualization of how the trimers in vanadium oxide layers A', B' & C' are stacked in c-direction.

For the LiVO2 sample, 10458 reflections were measured up to \(\sin (\Theta)/\lambda\) = 0.666—see Supplementary Table S3. Similarly to the other sample (Li0.91VO2), the crystal structure of LiVO2 can be described best with the same space group P31, twinning, and with similar split-atom model for one of the Vanadium sites. (The experimentally observed extinction conditions are consistent with this space group, as shown in Fig. 1b (left). In the same way as for the other sample, all other symmetries apart from the triclinic and trigonal Laue symmetries \(\bar{1}\), \(\bar{3}\) and \(\bar{3}1m\) could be directly excluded due to their extremely high Rint-values > 50%. Moreover, the structure refinement with space group P31 was stable, yielding the smallest possible R-values and GoF values, and without any nonphysical structural parameters.) For the LiVO2 sample, the twin fraction amounts to 49.53(14)%, and the split vanadium ion is found with a probability of 71.9(8)% at its regular position, both of which resemble the values determined for the Li0.91VO2 sample. Refinement and structural parameters for the LiVO2 sample can be found in Supplementary Table S4. Considering (i) the complex structure with large unit cell dimensions, (ii) the use of only three isotropic displacement parameters Uiso(Li), Uiso(V), Uiso(O) throughout the entire refinement, (iii) the presence of broad, overlapping superstructure reflections, and (iv) the disorder in the stacking of trimerized layers, the GoF and R-values attain acceptable values, indicating that the structural model for LiVO2 describes the measured X-ray intensities reasonably well. This is further corroborated by the BVS for all the vanadium sites (V1 to V6), which amount to 2.95(4), 2.86(4), 3.06(4), 2.90(3), 2.87(4) and 3.00(4). The vanadium–vanadium distances are listed in Table 1. The intra-trimer V–V distance in Li1.0VO2 has been directly determined by single crystal XRD, with a value of 2.53(3) Å. In contrast, the distance between non-trimerized neighboring V-ions amounts to 3.00(4) Å. The small scattering of V–V distances among V-ions within trimers and between neighboring V-ions in different trimers provides further evidence for the high reliability of this crystal structure model, as shown in Table 1. With a V–V distance of 2.53(3) Å, the V–V distances within each trimer are even shorter than in vanadium metal, where the shortest V–V distance amounts to 2.6206(5) Å29. Such a short bond length would usually favor a picture in which molecular orbitals form within the trimers. However, whether this molecular orbital description is appropriate is an important question, especially for compounds where Mott physics plays a significant role, as discussed above10,21,22,23,24,25,26.

A comparison of the crystal structures of LiVO2 and Li0.91VO2 reveals that the former shares a similar stacking of vanadium layers with the latter: the same structural elements are found in the same stacking order in every second vanadium layer A, B, and C of the LiVO2 sample, with the difference that additional vanadium oxide layers A’, B’, and C’ are introduced between the layers A, B, and C, i.e., layer A’ after layer A, etc.—see Fig. 6a, b. This difference in the stacking is responsible for the doubling of the c-axis in LiVO2. Interestingly, the additionally introduced vanadium layers A’, B’, and C’ do not exhibit any indication of split V-sites, suggesting that there is no related disorder due to a flipping of the trimers within a layer for these vanadium oxide layers A’, B’, and C’ in this structural modification.

Conclusion

In conclusion, two different Li1−xVO2 single crystals were synthesized with an optimized flux growth method. One crystal, LiVO2, exhibits well-known diffuse, streak-like superstructure reflection intensities, while the other crystal, Li0.91VO2, has well-separated superstructure reflection intensities. The crystal structure of the latter crystal, Li0.91VO2, was determined in the trimerized phase. Rather than resulting from a random stacking of the vanadium oxide layers, the streak-like appearance of the superstructure reflection intensities in the other modification of LiVO2 can be attributed to a doubling of the c lattice constant, which leads to a partial overlap of the doubled amount of superstructure reflections. The peak widths of the superstructure reflections are similar in both modifications, indicating a limited correlation length in the c-direction. A structural model for LiVO2 was also developed, which provides a reasonable fit to the measured XRD data, despite the overlap of superstructure reflection intensities and disorder. The limited correlation length in the c-direction for both structural modifications is consistent with a split-atom model and twinning. Trimer formation was observed at the atomic level in both types of Li1−xVO2 compounds, including the V–V distances within and between the trimers. Within a trimer of LiVO2, the V–V distances of 2.53(3) Å are smaller than those in vanadium metal. Our results also show that the trimer pattern in Li1−xVO2 remains stable when Li is deficient. The intra-trimer V–V distance is 2.59(6) for Li0.91VO2. Future theoretical studies will benefit from our crystal structure data on Li1−xVO2 single crystals, which will help to quantify the extent to which a molecular orbital description of the V-trimers is adequate in view of the Mott physics present in this compound.

Methods

Chemical synthesis and characterization

Single crystals of Li1−xVO2 were grown by a flux method. The starting materials Li2CO3 (99.995%, Alfa Aesar) and V2O3 (99.99%, Thermo Fisher) were mixed in stoichiometric quantities (plus a 3% excess of Li2CO3) and reacted (by solid-state reaction) in an alumina crucible under a flow of reforming gas (5% H2 95% Ar) at 750 °C for 48 h. As a flux for the single crystal growth a mixture of Li2CO3 and LiBO2 was chosen with a mass ratio of LiBO2, Li2CO3 and LiVO2 of 10:3:1. The entire mixture (flux and precursor) was heated at 1000 °C for 12 h. Then, it was cooled down to 700 °C with a cooling rate of either 5 K/h (Li0.91VO2) or 10 K/h (LiVO2), and afterwards to 30 °C with a cooling rate of 10 K/h. The whole growth process was conducted in a reforming gas atmosphere. Then, flux and single crystals were separated by dissolving the flux with distilled water at room temperature. For a determination of the Li content x we made use of the c/a-ratio (in notation of the high-temperature \(R\bar{3}m\) structure). It has been reported that a is smallest and c is largest for the (near) stoichiometric compound with x~120. The room-temperature lattice parameters of Li0.91VO2 & LiVO2 are listed in Supplementary Tables S1; S3. After transformation to the high temperature (\(R\bar{3}m\)) unit cell the c/a ratio of these lattice parameters amounts to 5.2106(5) for Li0.91VO2 and 5.2405(4) for LiVO2. From the former value, we derived the composition of Li0.91VO2. Note that our XRD results are indicative for a somewhat higher Li content with a composition of Li0.932(4)VO2. The value for the other sample is somewhat higher than the highest values reported for essentially stoichiometric samples in literature20. Since the largest c/a ratio can be expected for stoichiometric samples, this result would indicate a composition close to LiVO2 for that sample. Further complementary XAS measurements of this LiVO2 sample confirm its stoichiometry (see main text).

Single crystal X-ray diffraction (XRD)

Single crystal XRD measurements have been performed on a Bruker D8 VENTURE diffractometer (Mo Kα radiation) with a bent graphite monochromator for about three times intensity enhancement and equipped with a Photon III CMOS area detector. Single crystal XRD measurements reveal two different types of Li1−xVO2 systems with different stacking of vanadium oxide layers, which is reflected in the fact that the c-lattice constant of the LiVO2 sample is doubled compared to the Li0.91VO2 sample. The reflection conditions of both measured Li1−xVO2 polytypes are in agreement with space group P31, i.e., for (0 0 l) only reflections for l = 3n (\(n\in {\mathbb{Z}}\)) are observed in both cases—see Fig. 1b. The CIF-files of the structural models that we developed for both polytypes of Li1−xVO2 can be found in the Supplementary Data 1 (Li0.91VO2) and Supplementary Data 2 (LiVO2). The numerical data of the graphs/plots can be found in the Supplementary Data 3.

X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS)

Soft XAS measurements were conducted in the total electron yield mode at the TPS45A beamline of the National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center in Taiwan. The XAS measurements were performed at 300 K. A fresh sample surface was prepared by top-post-cleaving in ultra-high vacuum at 300 K. A V2O3 sample was measured simultaneously in an upstream chamber for energy calibration of the V L-edges. The numerical data of Fig. 2 can be found in the Supplementary Data 3.

Code availability

Computer code is available from http://jana.fzu.cz(Jana2006 version 04/12/2022).

References

Rüdorff, W. & Becker, H. Notizen: Über Umsetzungen des Vanadin(III)oxyds und des Vanadin(IV)oxyds mit einigen Metalloxyden. Z. f.ür. Naturforsch. B 9, 613–614 (1954).

Bongers, P. F. Structuur en magnetische eigenschappen van enkele complexe oxyden der overgangselementen. ’S-Gravenhage: Excelsior, Ph.D dissertation, The University of Leiden, Leiden, The Netherlands (1957).

Rüdorff, W. & Becker, H. Notizen: Die Strukturen von LiVO2, NaVO2, LiCrO2 und NaCrO2. Z. f.ür. Naturforsch. B 9, 614–615 (1954).

Reuter, B., Weber, R. & Jaskowsky, J. Über Oxidsysteme mit Übergangsmetallen in verschiedenen Oxydationsstufen und ihr elektrisches Verhalten I. Das System VO—LiVO2 Z. Elektrochem. 66, 832-838 (1962).

Goodenough, J. B. Magnetism and The Chemical Bond (Interscience Publishers, 1963).

Kobayashi, K., Kosuge, K. & Kachi, S. Electric and magnetic properties of LixV2−xO2. Mater. Res. Bull. 4, 95–106 (1969).

Hewston, T. A. & Chamberland, B. L. Preparation of LiVO2 crystals. J. Solid State Chem. 59, 168–173 (1985).

Hewston, T. A. & Chamberland, B. L. A study of the ternary oxide LiVO2 and its anomalous behavior. J. Solid State Chem. 65, 100–110 (1986).

Cardoso, L. P., Cox, D. E., Hewston, T. A. & Chamberland, B. L. Structural studies of Li0.7VO2 in the temperature range 20–300 ∘C. J. Solid State Chem. 72, 234–243 (1988).

Goodenough, J. B., Dutta, G. & Manthiram, A. Lattice instabilities near the critical V-V separation for localized versus itinerant electrons in LiV1−yMyO2 (m=cr or ti) li1-xvo2. Phys. Rev. B 43, 10170–10178 (1991).

Imai, K., Koike, M., Sawa, H. & Takei, H. Structural change in Li1−xVO2 (x≈0.2) single crystals. J. Solid State Chem. 102, 277–280 (1993).

Onoda, M. & Inabe, T. Role of structural change in phase transition in LiVO2. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 62, 2216–2219 (1993).

Imai, K., Sawa, H., Koike, M., Hasegawa, M. & Takei, H. Superstructure analyses on single crystals of Li0.8VO2. J. Solid State Chem. 114, 184–189 (1995).

Tian, W. et al. Single crystal growth and characterization of nearly stoichiometric LiVO2. Mater. Res. Bull. 39, 1319–1328 (2004).

Takao, K. & Onoda, M. Li local configurations for the trimerized state of the geometrically frustrated triangular lattice system Li1-xVO2 with 0 ≤ x ≤ 0.14. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 22, 116003 (2010).

Pourpoint, F. et al. New insights into the crystal and electronic structures of Li1+xV1−xO2 from solid state NMR, pair distribution function analyses, and first principles calculations. Chem. Mater. 24, 2880–2893 (2012).

Gaudet, J. & Dahn, J. Lattice constant anomaly in the Li1+xV1−xO2 system near x = 0. Can. J. Phys. 91, 444–449 (2013).

Kojima, K., Katayama, N., Tamura, S., Shiomi, M. & Sawa, H. Vanadium trimers randomly aligned along the c-axis direction in layered LiVO2. Phys. Rev. B 100, 235120 (2019).

Kojima, K. et al. Short-range order and increased transition temperature in LiVO2 with weakened trimer frustration. Phys. Rev. B 107, L020101 (2023).

Kinemuchi, Y., Masuda, Y., Ozaki, K. & Fujita, A. LiVO2 as a new solid-state phase change material. J. Alloy. Compd. 882, 160741 (2021).

Pen, H. F., van den Brink, J., Khomskii, D. I. & Sawatzky, G. A. Orbital ordering in a two-dimensional triangular lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 1323–1326 (1997).

Pen, H. F. et al. Phase transition in LiVO2 studied by near-edge x-ray-absorption spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 55, 15500–15505 (1997).

Ezhov, S. Y., Anisimov, V. I., Pen, H. F., Khomskii, D. I. & Sawatzky, G. A. Orbital polarization in LiVO2 and NaTiO2. Europhys. Lett. 44, 491 (1998).

Yoshitake, J. & Motome, Y. Trimer formation and metal-insulator transition in orbital degenerate systems on a triangular lattice. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 80, 073711 (2011).

Jin-no, T., Shimizu, Y., Itoh, M., Niitaka, S. & Takagi, H. Orbital reformation with vanadium trimerization in d2 triangular lattice LiVO2 revealed by 51V NMR. Phys. Rev. B 87, 075135 (2013).

Subedi, A. Mott-to-goodenough insulator-insulator transition in LiVO2. Phys. Rev. B 95, 214119 (2017).

Kikuchi, J. et al. 51V Knight shift and quadrupole interaction in the low-temperature phase of LiVO2. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 60, 3620–3624 (1991).

Thackeray, M., de Picciotto, L., David, W., Bruce, P. & Goodenough, J. Structural refinement of delithiated LiVO2 by neutron diffraction. J. Solid State Chem. 67, 285–290 (1987).

Carlson, O. N. & Owen, C. V. Preparation of high-purity vanadium metalb by the iodide refining process. J. Electrochem. Soc. 108, 88 (1961).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Y. Prots, P. Höhn, H. Borrmann, U. Schwarz and A. Severing for helpful discussions. We acknowledge the support for the XAS measurements from the Max Planck-POSTECH-Hsinchu Center for Complex Phase Materials.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Project management: A.C.K.; crystal growth: S.Y.; single crystal XRD measurements: A.C.K.; soft XAS measurements: C.-F.C., S.-H.C., C.-Y.K.; interpretation and manuscript writing: A.C.K. and L.H.T. with contributions from the other authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yun, S., Chang, CF., Chen, SH. et al. Direct observation of V-trimers in the crystal structure of LiVO2. Commun Chem 8, 202 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01595-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01595-y