Abstract

The dynamic nature of supramolecular networks of telechelic polymers offers new avenues for the design of novel materials with enhanced melt strength and extensibility, increased energy at break, or self-healing properties. However, monitoring the kinetics of the underlying molecular-level scission-reaggregation events remains challenging, particularly in high-molar-mass polymers in the bulk state. Here, we employ solid-state 1H NMR spectroscopy relaxation dispersion experiments to investigate the aggregation-scission dynamics in poly(ε-caprolactone) modified with oligopeptide end groups that form one-dimensional hydrogen-bonded aggregates. We have successfully determined the timescale of end-group dissociation directly and independently of any relaxation of the polymer segments at different temperatures in the bulk semi-crystalline and melt state. This site-specific, non-destructive method is applicable to entangled, high-molar-mass polymers without chemical modifications or modeling, provides critical insight into the dynamics of supramolecular networks in the bulk state, and promises to be a valuable tool for the directed development of next-generation functional materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The inherently dynamic nature of networks based on dynamic covalent1 or supramolecular2,3 crosslinking motifs has been instrumental in expanding the property landscape of polymers towards materials with self-healing properties, improved recyclability, and enhanced toughness, compressional strength, and extensibility4,5,6,7,8. Supramolecular crosslinks, especially those based on hydrogen-bonding motifs9, have attracted particular interest for the development of materials with tailored time-dependent properties. This is because their dynamics are characterized by much shorter timescales than those of dynamic covalent networks10,11,12. Meijer et al. were the first to describe reversible polymers and polymer networks based on difunctional small molecules and low molar mass telechelic polymers interacting through self-complementary multivalent hydrogen-bonded ligands13,14. Such materials behave as well-entangled high molar mass or covalently crosslinked polymers, but with precise transitions to low-viscosity melts at the dissociation temperature of the supramolecular aggregates14,15,16, suggesting this to be a promising route to more easily processable and recyclable plastics17. Although the low end-group concentration usually precludes use of high molar mass polymers with dimerizing monotopic end groups, our group has recently shown that this limitation may be overcome through co-assembly of ditopic end groups that form extended one-dimensional aggregates with a low molar mass additive based on the same supramolecular motif18. Thus, high molar mass, semicrystalline polyesters may be modified to produce materials with enhanced melt elasticity and strain hardening, and exceptional melt extensibility. It is suggested that reversible scission of the one-dimensional extended aggregates by dynamic exchange of the additive and end groups contributes to their orientation along the tensile direction during melt drawing, while reaggregation occurs fast enough to prevent macroscopic flow at temperatures immediately above the melting point of the base polyester.

Indeed, while the overall degree of crosslinking in thermo-reversible elastomers and related materials containing supramolecular network junctions is determined by the thermodynamic equilibrium constant of aggregation, the aggregation kinetics may profoundly impact not only the flow behavior but also other important macroscopic properties, such as the self-healing efficiency19,20. It is therefore of key interest to tailor the aggregation kinetics of any given system in order to optimize its performance in target applications or processing techniques. The macroscopic time- and temperature-dependent flow behavior in elastomers with phase-separated micelles formed by hydrogen bonding21,22 or ionic23 groups has been investigated in detail by dynamic shear rheometry or dielectric spectroscopy. Related studies show that relaxation occurs through a chain-hopping mechanism, where sticker detachment from micelles is the rate-determining step, and the associated activation energy barrier is governed by the interaction strength with the polymer matrix24. Often, dielectric spectroscopy detects faster relaxation than shear rheometry25,26, consistent with Rubinstein and Semenov’s theory that molecular-scale crosslinking dynamics in reversible, gel-like dimeric polymer end-group aggregates do not necessarily coincide with the time scales associated with macroscopic relaxation27. It follows that a profound understanding of the effect of molecular-scale hydrogen bond dissociation events on the macroscopic response requires additional site-specific techniques that characterize end-group dissociation directly. However, analytical techniques that independently reveal the timescale of macroscopic and molecular-scale relaxation phenomena have so far only been described for systems in dilute solution and may require elaborate chemical modification for labeling. For example, Craig et al. designed and investigated systems based on metal-ligand interactions with roughly equal equilibrium constants of association, but drastically different dissociation rate constants, and showed that the macroscopic viscosity scales linearly with the dissociation rate constant determined by NMR spectroscopy in solution28,29. Isothermal titration calorimetry7 and single-molecule force microscopy6,30 have also provided quantitative data on site-specific exchange in supramolecular hydrogels and elastomers, and the conformational dynamics of oligoalanine-containing self-assembled nanofibers in solution have been resolved by electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy31. Meijer et al. were also able to visualize molecular exchange in solutions of benzene-1,3,5-tricarboxamides (BTA)-based supramolecular aggregates composed of different-colored fluorescence-labeled monomers by computer-assisted ultra-high-resolution microscopy32 and modeling studies suggest that monomer exchange occurs primarily at structural defect sites in this system33.

By contrast, although the kinetic rate constants of the molecular-level association-scission events in supramolecular aggregates of polymer end groups are suspected to be linked to macroscopic rheological relaxation times in the bulk state34, to the best of our knowledge, direct experimental proof is lacking35, primarily due to the absence of established analytical techniques for selectively monitoring end-group dynamics in a bulk polymer matrix. Moreover, in telechelic polymers with multivalent hydrogen-bonded end groups, the complex interplay of polymer backbone dynamics and the supramolecular network dynamics makes differentiated analysis particularly challenging36,37,38. There is hence a need for a versatile method to characterize hydrogen bond dynamics in technologically relevant systems, namely a site-specific technique with molecular resolution, appropriate temporal resolution, that is applicable to bulk polymers and does not require labeling, ad hoc chemical modification, or extensive modeling.

Solid-state NMR spectroscopy is a powerful non-destructive method of studying polymers and biomacromolecules39. It allows for structural studies of synthetic disordered or semi-ordered systems, such as organic semiconductors40, metal-organic frameworks41, and supramolecular materials42,43. The advent of fast magic angle spinning (MAS) in combination with high magnetic field spectrometers (>9.7 T) has inherently improved the spectral resolution of solid-state 1H NMR spectroscopy, marking the beginning of its application to the structural characterization of hydrogen-bonded molecules, biomacromolecules, and supramolecular materials44,45. Time-resolved solid-state NMR spectroscopy is also capable of revealing conformational reorganization, short-lived transient states, and dynamic motion in a site-specific manner with a temporal resolution down to a few microseconds46,47,48. The transverse relaxation rate (R2) depends on structural dynamics and may be monitored using the Carr–Purcell–Meiboom–Gill (CPMG) pulse sequence49,50, which is used to study protein dynamics in a time range of a few microseconds to about 30 ms in liquid environments51,52 and, more rarely, in the solid state48,53,54. This type of experiment, combined with computer simulations, has considerably advanced the understanding of protein folding processes and the associated transient states55,56,57,58,59.

However, while supramolecular materials are increasingly characterized using solid-state NMR spectroscopy, their molecular-scale dynamics so far received little attention60,61. Existing studies are generally limited to temperature-dependent structural rearrangements and variations in hydrogen bond strengths, and advanced structural characterization, such as the determination of intermolecular distances between aggregated molecules using 2D NMR spectroscopy techniques42,43,62,63. Saalwächter et al. combined solid-state NMR spectroscopy with shear rheometry to elucidate the relaxation mechanism of a bulk low molar mass telechelic with end groups that aggregate into microscopic clusters. Their analysis focused on relaxation observations of the main chain64, whereas local processes within the supramolecular clusters remain to be studied.

Here we demonstrate, for the first time, the use of solid-state NMR spectroscopy to study the dynamics of hydrogen-bonded aggregates that give rise to a supramolecular polymer network in the bulk state. To this end, we have investigated materials based on an entangled telechelic aliphatic polyester modified with oligopeptide end groups, which are known to aggregate into a physical network of β-sheet nanofibrils18,65. Taking advantage of the high sensitivity of NMR spectroscopy to 1H nuclei, which facilitates the study of the dynamics of the polymer end groups at the intrinsically low concentration imposed by the polymer molar mass, we have used relaxation dispersion experiments based on the CPMG pulse sequence to monitor the end-group dissociation events at different temperatures. Such events are reflected by a characteristic increase in the apparent transverse relaxation rates (R2) of the amide proton signals as a function of the echo delay time (τ). This approach fills a key experimental gap by combining site-specificity, as in previous high-resolution microscopy studies on supramolecular systems in solution32 or in the gel state7, with temporal resolution appropriate for the non-destructive characterization of technologically relevant polymer materials, that is, highly entangled bulk polymers in the semi-crystalline or melt state, while avoiding the need for additional chemical modification or modeling.

Results and discussion

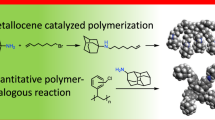

We have chosen to test the applicability of solid-state NMR spectroscopy relaxation-dispersion experiments using oligopeptide-modified telechelic poly(ε-caprolactone) (Mn = 22,000, which is about seven times its entanglement molar mass, Me \(\approx\) 3000 /mol66), mPCL, which contains about 2 wt% of acetyl-l-alanyl-l-alanyl (AcAla2) end groups (Fig. 1a), as reported previously by our group18. Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) is an aliphatic polyester, a class of polymers that may be technologically relevant as potential sustainable replacements for current petroleum-based plastics67,68, but whose low melt strength and poor form stability at elevated temperatures limit their processability and applications. PCL has a degree of crystallinity of about 40 wt%, a glass transition temperature, Tg, of about −60 °C, and a nominal melting temperature, Tm, of about 55 °C. Although the amorphous domains soften and increase in mobility above Tg, it hence remains a biphasic, rheologically solid material up to Tm, beyond which it transforms into a low viscosity liquid for the molar mass of Mn = 22,000 under consideration here.

a Chemical structure of mPCL modified with AcAla2 end groups (blue) that aggregate by threefold hydrogen bonding into polymer-linked β-sheet nanofibrils65. b Oscillatory shear rheometry temperature sweeps (1 rad s–1, cooling at 5 °C min–1) show a rubbery plateau (with a storage modulus G’ ≈ 0.9 MP at 60 °C) between the polymer crystallization temperature and the G” > G’ crossover temperature at 85 °C. c DSC heating (red) and cooling (blue) curves of mPCL (5 °C/min) in which the nominal Tm = 55 °C and the crystallization temperature Tc = 27 °C are highlighted, with insets showing the transitions corresponding to end-group dissociation at Td = 84 °C (heating) and aggregation at Tagg = 83 °C (cooling). d Amide A and e amide I and II regions of the FTIR spectra of mPCL recorded at different temperatures (29–94 °C), and unmodified PCL with about the same molar mass (PCL20, gray). The band at 3448 cm−1 is attributed to adsorbed water, possibly coexisting with free amide.

The AcAla2 end groups in the modified mPCL are designed to aggregate via trivalent, self-complementary hydrogen bonding to form well-defined nanofibrils comprising helically twisted stacks of β-sheet-like tapes18,65. This results in a supramolecular network of hydrogen-bonded nanofibrils bridged by polymer segments, which manifests itself as a rubbery plateau in oscillatory shear rheometry temperature sweeps (Fig. 1b) extending up to the dissociation temperature, Td = 84 °C of the end-group aggregates, as determined by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC, Fig. 1c). Below Td, temperature-variable Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra show the vibrational bands of the amide functions at 3268 cm−1 (N–H stretching, amide A), 1629 cm–1 with a second component at 1688 cm–1 (C=O stretching, amide I), and 1543 cm−1 (C=O bending, amide II), which is the characteristic signature of extended β-sheet aggregates (Fig. 1d,e)69. These aggregates coexist with weakly aggregated amides, as indicated by the presence of an additional band at 3368 cm–1, corresponding to kinetically trapped defects that are unable to undergo reorganization. Above Td = 84 °C, only this band is present, and the transition observed in DSC heating scans thus corresponds to the dissociation of the β-sheet aggregates into disordered colloidal aggregates, rather than molecularly dissolved species.

As the temperature approaches Td, we expect reversible scission-reassociation processes within the AcAla2 aggregates to give rise to structural rearrangements during macroscopic deformation that should contribute significantly to macroscopic stress relaxation. Indeed, shear rheology frequency sweeps performed at T > Tm = 55 °C indicate a viscoelastic relaxation process in the form of a local maximum in G” and a simultaneous downturn in G’ at low frequencies, until the nanofibrillar network dissociates at T > Td = 84 °C where the material behaves like a viscous fluid in the experimentally available frequency range (Supplementary Fig. S1). These results confirm the dynamic behavior of mPCL on a macroscopic length scale below the dissociation of the nanofibrils at Td = 84 °C.

We therefore consider this material, with its well-characterized thermal transitions and macroscopic relaxation events at temperatures Tm < T < Td, to be an ideal benchmark for establishing the suitability of temperature-variable solid-state NMR spectroscopy relaxation dispersion experiments for investigating the underlying molecular-scale dissociation dynamics. Relaxation dispersion experiments probe molecular exchange on relevant timescales if the investigated species exhibit distinct isotropic shifts. In hydrogen-bonded supramolecular materials, such as amides, exchange between bound and free states typically meets this criterion58. Additionally, the peak of the higher populated, aggregated species must be well separated from others, including those from the polymer matrix, to enable peak deconvolution.

We have first investigated the bulk modified mPCL materials by solid-state 1D 1H NMR spectroscopy at 25 °C and 60 °C. Solution-phase 1D 1H NMR spectra have also been recorded at 25 °C in CDCl3 to aid peak assignment. Because the polymer end groups that participate in supramolecular aggregation make up only 2 wt% of the material, we have chosen 1H detection in combination with high magnetic field strengths to ensure adequate intensity for integration and sufficient spectral resolution to separate the diagnostic end-group peaks from the significantly more intense polymer backbone peaks. We have used a 1.3 mm rotor as a compromise to maximize the specimen size, while still permitting a MAS frequency as high as 55 kHz, which directly determines the lower limit of the temporal resolution of the relaxation dispersion experiments (minimum echo delay time, τ = 2 rotor periods = 2/MAS frequency) and further improves spectral resolution.

Four high-intensity peaks are visible at 25 °C and 60 °C in the spectral regions characteristic of aliphatic protons (h–j), protons adjacent to carbonyl groups (e), and protons adjacent to ester functions (c; Fig. 2). In the solid-state 1H NMR spectra, the polymer peaks are comparatively narrow with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 0.4 ppm even at 25 °C, reflecting the mobility of the amorphous PCL domains above Tg. These peaks become even narrower, with a FWHM of 0.2 ppm at 60 °C, where the PCL matrix is fully molten, although the material remains a rheological solid due to the supramolecular network of nanofibrils. However, only one of the end-group peaks (d at δ = 3.66 ppm) is visible in the lower δ region of the solid-state spectra, the end-group proton peaks a, b, f and g only appearing in the solution-phase NMR spectra. By contrast, the peaks assigned to the amide protons NH1, NH2, and NH3 of the AcAla2 end groups are clearly present in the range δ = 7.4–9.3 ppm and hence occupy a distinct region of the solid-state NMR spectra. Consistent with aggregation of the end groups, these peaks are broad, and their chemical shifts are increased by 2.5 ppm relative to those in the solution-phase spectra, implying a higher hydrogen bond strength58. When the temperature is increased to 60 °C, the shape, δ, and FWHM of the peaks in the solid-state NMR spectra assigned to NH2 and NH3 remain unchanged, but two additional, well-resolved peaks appear that are superimposed onto the NH1 peak. We assign these new peaks to weakly aggregated amide protons (NHweak) corresponding to disordered but still phase-separated colloidal aggregates that coexist with the aggregated amides at and above 60 °C, consistent with the results from FTIR spectroscopy (Fig. 1d,e), and with what has recently been observed for modified PCL with BTA end groups70. Solid-state NMR experiments using MAS at temperatures above Td = 84 °C, where the end groups are completely dissociated, are precluded, because the material becomes liquid.

Relaxation dispersion experiments based on the CPMG pulse sequence can detect the correlation time of molecular motion processes in a site-specific manner through their influence on the R2 values for peaks assigned to the respective nuclei. We have used this phenomenon to semi-quantitatively determine the correlation time of scission events of the amide hydrogen bonds forming the β-sheet-like aggregates. In what follows, we refer to the correlation time of the scission events in the amide polymer end groups as “amide dynamics”, with a kinetic dissociation rate constant kd and a hydrogen bond lifetime 1/kd.

The peaks of NH2 and NH3 are well separated from other signals, whereas NHweak and NH1 overlap with the flank of the intense polymer peak. Because of the overlap, we have only considered the sum of the integrals of the NH2 and NH3 peaks in what follows and refer to this as NH2 + NH3. To obtain time-sensitive spectra, we have systematically increased echo delay times, τ, defined in integers of one rotor period (rp, [s] = 1/MAS frequency) in the range 4 rp (72 μs) to 240 rp (4.36 ms), for a total of 12 different τ (“Materials and methods”, Table 1). To determine the τ-dependent R2, we have recorded at least five spectra for a given τ, which differ in the number of echoes, n, so that the total experimental time is given by texp = τ · n (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. S2). In absence of any dynamic processes occurring within the chosen time, τ, spectra recorded at equal texp resemble each other regardless of τ. This is, for example, the case for the mPCL backbone peaks at 25 °C (Fig. 4a) but not for the end-group peaks (Fig. 4b), providing a first, qualitative indication that amide hydrogen bond scission occurs within the experimental time window of 72 µs ≤ τ ≤ 4.36 ms.

Representative examples illustrating the procedure used to obtain R2 for a given τ, in this case for τ = 12 rp (=12/55 kHz). a Vertical stack of spectra from CPMG experiments at τ = 12 rp for different n as indicated. b Deconvolution of the spectrum for n = 10. c The decay in the sum of the integrals of the NH2 + NH3 peaks obtained from the deconvolution of each spectrum is used to obtain R2 according to Eq. 1. Spectra for all the τ investigated and the corresponding exponential fits to the decay in the integrals of the NH2 + NH3 peaks are provided in Supplementary Fig. S2.

a, b 1H NMR spectra of mPCL from CPMG experiments at 25 °C for different τ, where n has been varied so that texp = 4.64 ms for all the spectra. The spectral regions containing the polymer backbone peaks (δ = 1–5 ppm) and the end-group peaks (δ = 6–12 ppm) are shown separately at different magnifications. c Whereas R2 for the peaks associated with j (gray squares, the dashed line serves as guide to the eye) remains constant, R2 for the NH2 + NH3 peaks (blue squares) increases over the investigated range of τ (the data point at τ = 4.36 ms is unreliable because it was obtained from a linear fit to two points, see Supplementary Fig. S2). R2 for the peaks associated with the polymer peaks c, e, h, i, j is shown in Supplementary Fig. S4. The solid red curve represents the best fit of the Carver–Richards equation to the overall increase in R2 for the NH2 + NH3 peak, caused by the amide dynamics, with kd = 1550 ± 1400 s–1 and R2,0 = 0.15 ± 0.02 ms–1. We attribute this behavior to (d) dissociation of all three hydrogen bonds. A list of all the experiments, along with spectra for all the τ investigated and the corresponding exponential fits to the decay in the integrals of the NH2 + NH3 peaks, is provided in Materials and Methods and Supplementary Fig. S6. Error bars represent uncertainties from the fitting procedure, which exceeded the experimental error in all cases.

To obtain R2 for quantitative analysis of the amide dynamics, we have fitted the spectral regions in the range of 6–12 ppm (amide peaks of the end groups) and 0–6 ppm (polymer backbone peaks) of each spectrum separately using the open-source software DMFIT71. We have chosen a total of seven peaks for the deconvolution (see Materials and Methods). Moreover, we have applied a Gaussian fit to the peaks assigned to NH2 and NH3, and a Lorentzian fit to the peaks assigned to NHweak coexisting with the third aggregated amide NH1 (Fig. 3b). The Gaussian shapes of the NH2 and NH3 peaks are indicative of restricted motion, and hence a heterogeneous electronic environment, as expected for aggregated amides. Exponential fits to the decay in the integral with increasing total experimental time texp = τ · n yield R2 (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. S2), according to:

Any external influence on R2, for example, a magnetic field or temperature fluctuation, would result in a change in both R2 and the FWHM, because R2 = R2’ + R2† and FWHM = R2/π, where R2’ covers homogeneous contributions to transverse spin relaxation and is enhanced by dynamic processes with a coherence time within the investigated time frame, and R2† includes inhomogeneous effects that cause line broadening, such as structural heterogeneity72. More specifically, R2’ and thus R2 is expected to increase with τ if additional motional processes involving the molecular site assigned to the investigated peak occur within that time frame. The C–C bonds of the polymer backbone undergo bond rotations and vibrations in a nanosecond time range, which is faster than that probed by relaxation dispersion experiments73. Indeed, whereas R2 of the polymer peak j corresponding to the amorphous fraction remains constant over the time range investigated due to the absence of any change in polymer dynamics, R2 of the peaks assigned to NH2 + NH3 shows a significant increase within the experimental time window of 72 µs ≤ τ ≤ 4.36 ms, while the corresponding FWHM remains constant (Supplementary Fig. S3), which one may hence interpret to originate from the accelerating amide bond dynamics. Accordingly, we fitted the increase in R2 over the whole range 72 µs ≤ τ ≤ 4.36 ms with the Carver–Richards model for fast two-site exchange (Eq. 2)73,74, which is often used to extract kinetic rate constants associated with exchange processes in biomacromolecules from CPMG experiments in solution73,75:

Here, R2,0 is the initial transverse relaxation rate before the onset of amide dynamics, kd is the rate constant for the exchange from the aggregated to the dissociated state, and ɸ = pA ∙ pD ∙ Δω2, where pA and pD are the fractions of aggregated and dissociated amide, respectively, and Δω is the difference in resonance frequency of the peaks associated with the two states74. Assuming a fast exchange between NH2 and NH3 and their respective dissociated states according to the Carver–Richards model, which is supported by the absence of additional peaks at increasing τ and no signs of exchange in exchange spectroscopy experiments (EXSY, Supplementary Fig. S5), we obtain the corresponding overall dissociation rate constant, kd = 1550 ± 1400 s–1 (red line in Fig. 4c), corresponding to a hydrogen bond lifetime of 0.65 ± 0.59 ms at 25 °C, which we associate with combined dissociation of all three hydrogen bonds (Fig. 4d). While the Carver–Richards fitting captures the overall process reasonably well, the systematic deviations in the experimental data may indicate a multi-step dissociation process, or a broad distribution of the apparent kd similar to what is observed for supramolecular materials studied using dielectric spectroscopy25.

We have subsequently used the same procedure and τ range as at 25 °C to investigate the amide dynamics at 60 °C, while the polymer backbone peaks serve again as a reference, because their dynamics are expected to occur on a time scale below 72 μs. Indeed, the intensities of the polymer backbone peaks c, e, h, i and j do not change in the investigated time window of 72 μs to 4.36 ms (Fig. 5a). By contrast, those of the NH2 and NH3 peaks decrease in spectra recorded at increasing τ but similar texp, due to the increasing amide mobility (Fig. 5b). Compared with spectra obtained from the CPMG experiments at 25 °C, the peaks of NH2 and NH3 remain constant in shape, FWHM, and δ, suggesting no structural changes in the NH2 and NH3 aggregates. This is not the case for the spectral region containing peaks assigned to NH1 and NHweak, where three well-resolved peaks with a FWHM of 0.04–0.08 ppm are now visible at 60 °C, and the broader NH1 peak observed at 25 °C is absent (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Figs. S6–7). This indicates that the NH1 scission already occurs at τ < 4 rp at 60 °C. These qualitative observations are further supported quantitatively by the τ-dependent R2 values of the amide peaks at 60 °C. These show an initial plateau at τ = 72–292 μs, a smooth increase in the range 292 μs ≤ τ ≤ 0.616 ms, and finally a second plateau at τ > 0.616 ms extending to the point where the intensity of NH2 + NH3 is too weak to permit integration (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Fig. S6). It is suggested that NH1 dissociation occurs too rapidly to be detected in the experimentally available time range, and that dissociation of NH2 and NH3 now occurs simultaneously. We have again fitted the Carver–Richards Eq. (2) to the R2 data and obtain kd = 5170 ± 1910 s–1, corresponding to a hydrogen bond lifetime of 0.19 ± 0.07 ms. R2 for the polymer peak of j again remains constant over the whole time range investigated, indicating no change in polymer dynamics.

a,b 1H NMR spectra of mPCL from CPMG experiments at 60 °C for different τ, where n has been varied so that texp is similar for all the spectra. The spectral regions containing the polymer backbone peaks (δ = 1–5 ppm) and the end-group peaks (δ = 6–12 ppm) are shown separately at different magnifications. c R2 for the peaks associated with j (gray squares) and NH2 + NH3 (blue squares). The dashed lines represent the plateaus in R2. The solid red curve represents the best fit of the Carver–Richards equation to the increase in R2 for the NH2 + NH3 peak, caused by the amide dynamics, with kd = 5170 ± 1910 s–1 and R2,0 = 0.10 ± 0.02 ms–1. A list of all the experiments, along with spectra for all the τ investigated and the corresponding exponential fits to the decay in the integrals of the NH2 + NH3 peaks, is provided in Materials and Methods and Supplementary Fig. S6. Error bars represent uncertainties from the fitting procedure, which exceeded the experimental error in all cases.

With all uncertainties due to the change in the physical state of the polymer matrix and the fact that we only have two data points, comparison of the kd from the overall Carver–Richards fits at 25 and 60 °C indicates the dynamics of the β-sheet-like aggregates to be accelerated by a factor of 3.3, which implies an apparent activation energy Ea ≈ 31 kJ mol–1 for the dissociation process. This is in a similar range to Ea = 62 ± 15 kJ mol–1 reported for the dissociation process of dimers of UPy in toluene formed by fourfold hydrogen bonding76, and Ea = 32 ± 2 kJ mol–1 for the dissociation of BTA aggregates formed by threefold hydrogen bonding in n-dodecane at 20 °C36. The protein ubiquitin may be considered to be a benchmark for NMR studies of dynamics in biomacromolecules because it is known to undergo conformational changes associated with its biological functions on the microsecond to millisecond time scale as a result of amide hydrogen bond dynamics59. The rate constants for these processes determined by solid-state NMR relaxation dispersion experiments at 27 °C are of the same order of magnitude (2100–10,000 s–1)53,77 as kd determined here for the AcAla2 end-group dynamics at 25 °C and 60 °C, while the dynamics of ubiquitin at 5 °C in solution are more rapid (18,800 ± 900 s–1)52.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a method to monitor the dissociation of β-sheet-like aggregates of AcAla2 polymer end groups within the bulk polymer matrix at various temperatures, with a temporal resolution ranging from 72 μs to 4.36 ms. By measuring the evolution of R2 associated with the amide peak in solid state NMR with τ, we may directly determine the timescale of the amide dissociation independently of any relaxation of the polymer segments. This approach is applicable to any material containing dynamic crosslinks, provided there is sufficient spectral resolution. It stands out from previous attempts to measure the dissociation rates of dynamic crosslinks, which have typically focused on small molecule model compounds in liquid environments, in that it is site-specific and suitable for both the semicrystalline and molten states of a bulk high molar mass polymer matrix, by which we mean molar masses that are several times the polymer’s entanglement molar mass. We find that the AcAla2 crosslinks in our system remain dynamic even at room temperature, where the bulk polymer matrix behaves as a rigid solid, and that their dynamics accelerate at 60 °C, where the polymer segments are fully molten. This method is hence a potentially powerful tool for comparing the dynamics of different systems in the bulk state, such as networks based on different supramolecular units. This should allow us to link the microscopic, molecular-scale dynamics to macroscopic relaxation phenomena, significantly contributing to our understanding of the dynamics of supramolecular interactions in soft materials, which are increasingly used to tune their macroscopic properties.

Materials and methods

Materials

The following compounds and reagents were obtained from commercial suppliers and used without further purification: Chloroform-d, >99.80% (CDCl3, Apollo Scientific); N,N-Diisopropylethylamine, 99% (DIPEA, abcr GmbH); N-(9-Fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl)-l-alanine (Fmoc-Ala-OH, Novabiochem); 2-(dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP, Fluorochem); N,N-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide, 99% (DCC, Acros Organics); piperidine, 99% (Acros Organics), N-acetyl-l-alanine (GL Biochem); hydroxy-telechelic poly(ε-caprolactone) (Mn = 10,000 g/mol specified, Mn = 22,000 g/mol according to GPC analysis) (Aldrich); tetrahydrofurane (THF), DCM, and methanol were purchased from Reactolab SA and distilled prior to use.

Synthesis of mPCL

The end-modified mPCL was prepared in four steps as described in the literature18:

PCL20-AlaFmoc (1)

Hydroxy-telechelic poly(ε-caprolactone) (Mn = 20,000, 100 g) was dissolved in THF (700 mL). Fmoc-Ala-OH (17.7 g, 113 mmol), DMAP (3.45 g, 28.2 mmol), and DCC (35.3 g, 171 mmol) were added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3d. The mixture was poured into MeOH. The precipitate was dried under high vacuum to yield PCL20-AlaFmoc 1 as a colorless solid in a yield of 97 g (97%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.80 (d, 2H), 7.61 (m, 3H), 7.41 (m, 3H), 7.34 (m, 4H), 5.42 (bs, 1H), 4.40 (brs, 7H), 4.26 (brs, 100H), 4.08 (t, 198H), 2.32 (t, 200H), 1.68 (m, 426H), 1.41 (m, 213H) ppm.

PCL20-AlaNH2 (2)

PCL20-AlaFmoc 1 (95 g) was dissolved in DCM (400 mL), and piperidine (5.0 g) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 d and then poured into MeOH (1.5 L). The precipitate was re-dissolved in DCM and poured again into MeOH. The precipitation procedure was repeated one more time. The precipitate was washed with MeOH and hexane and was dried under high vacuum to yield PCL20-AlaNH2 2 as a colorless solid in a yield of 79 g (83%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 4.09 (t, 1.94H), 3.92 (t, 0.03H), 3.57 (m, 0.02H), 2.33 (t, 2.00H), 1.67 (m, 4.26H), 1.41 (m, 2.16H) ppm.

PCL20-Ala2Fmoc (3)

Fmoc-Ala-OH (7.35 g, 47.2 mmol), DIEA (3.78 g, 28.5 mmol), and PyBOP (13.2 g, 25.7 mmol) were added to a solution of PCL20-AlaNH2 2 (70 g) in THF (700 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 d and then poured into MeOH (1.2 L). The precipitate was re-dissolved in DCM, and the solution was again precipitated into MeOH. The precipitate was collected, washed with hexane, and dried under high vacuum to yield PCL20-Ala2Fmoc 3 as a colorless solid in a yield of 70 g (99%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.79 (d, 0.03H), 7.61 (d, 0.03H), 7.42 (m, 0.03H), 7.34 (m, 0.04H), 6.46 (brs, 0.01H), 5.45 (brs, 0.01H), 4.58 (t, 0.02H), 4.07 (t, 1.89H), 2.33 (t, 2.00H), 1.67 (m, 4.26H), 1.41 (m, 2.21H) ppm.

PCL20-Ala2NH2 (4)

PCL20-Ala2Fmoc 3 (69 g) was dissolved in DCM (400 mL), and piperidine (5.0 g) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 d and then poured into MeOH (1.5 L). The precipitate was re-dissolved in DCM, and the solution was again precipitated into MeOH. The precipitate was washed with MeOH and hexane and dried under high vacuum to yield PCL20-Ala2-NH2 4 as a colorless solid in a yield of 62 g (90%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 7.73 (brs, 0.01H), 4.59 (t, 0.01H), 4.09 (t, 2.06H), 2.34 (t, 2.00H), 1.67 (m, 3.98H), 1.41 (m, 2.34H) ppm.

mPCL

N-acetyl-l-alanine (1.76 g, 13.4 mmol), DIEA (2.16 g, 16.7 mmol), and PyBOP (7.56 g, 14.5 mmol) were added to a solution of PCL20-Ala2-NH2 4 (40 g) in THF (500 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 5 d, then poured into MeOH (1.5 L). The precipitate was collected, washed with hexane, and dried under high vacuum to yield mPCL as a white solid in a yield of 39 g (98%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 6.60 (m, 0.02H), 6.13 (m, 0.01H), 4.47 (m, 0.04H), 4.09 (t, 1.90H), 2.33 (t, 2.00H), 2.04 (s, 0.07H), 1.67 (m, 3.94H), 1.41 (m, 2.14H) ppm; GPC: Mn = 22200 g/mol; Mw = 29300 g/mol; Ð = 1.32. TGA: decomposition onset: 387 °C. DSC: Tm = 54 °C, Tc = 28 °C, Td = 77 °C, Ta = 76 °C. The 1H NMR spectrum is shown in Supplementary Fig. S8.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

DSC measurements were performed with a Mettler Toledo DSC 3+ under N2 atmosphere (flow rate 10 mL min–1) at a scanning rate of 5 °C/min. Approximately 10 mg of mPCL was used for each measurement, which comprised four heating and three cooling scans to check for reproducibility. The results shown are from the second heating and first cooling scans.

Infrared (IR) spectroscopy

Films of mPCL were prepared for IR spectroscopy by drop casting from a 10 mg mL–1 solution in DCM onto KBr windows (iCL, REAL CRYSTAL IR CARD). The films were dried under vacuum, melted at 150 °C using a hot plate, and cooled to ambient temperature at 10 °C/min. The IR spectra were averaged over 100 scans recorded in transmission with a JASCO FT/IR 6300 spectrometer at a spectral resolution of 4 cm–1. The temperature was controlled with the PIKE accessory (Madison, WI) and measured by placing a thermocouple (METRA Instruments, Type-K) close to the specimen surface.

Oscillatory shear rheometry

Dynamic shear rheometry was performed with a TA Instruments ARES 2 rheometer and parallel steel plates. The diameters of the upper and lower plates were 8 and 25 mm, respectively, and the gap was set to 0.5 mm. To record temperature sweeps, molten mPCL was loaded at 150 °C and then cooled to 25 °C at 5 °C min–1, while applying a cyclic strain of amplitude 0.5% at a fixed angular frequency of 1 rad s–1. For the frequency sweeps, specimens were molten at 150 °C using a hot plate, and cooled to ambient temperature at 10 °C/min. The specimens were loaded at the experimental temperature, allowed to equilibrate for 15 min, and frequency sweeps were performed starting from 500 rad/s and scanning to 0.01 rad s–1. Time-temperature-superposition (TTS) was applied using the implemented software from TA Instruments to shift the curves horizontally by temperature-dependent shift factors aT, and vertically by bT.

Solution-phase NMR spectroscopy

Solution-phase 1D 1H NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 at 25 °C with a Bruker Avance III 400 spectrometer (9.7 T) at a 1H Larmor frequency of 400 MHz and calibrated with respect to the residual CDCl3 solvent peak (1H CDCl3 δ = 7.26 ppm).

Solid-state 1D NMR spectroscopy

For solid-state NMR spectroscopy, mPCL was melted in the oven of the ARES 2 rheometer at 150 °C and cooled to ambient temperature at 10 °C/min. Small fragments were cut from the solidified material and placed in a ZrO2 rotor with an outer diameter of 1.3 mm (2.5 μL specimen volume, filled to ~70%), which was subsequently sealed with SP1 bottom and drive caps from Bruker. Solid-state NMR experiments were performed with a Bruker Avance NEO 800 MHz spectrometer (18.8 T) equipped with a 1.3 mm standard bore CPMAS triple channel HCN probe. The temperature was controlled with the built-in control unit. After each change in temperature, the specimen was allowed to equilibrate for 5 min. The spectra were calibrated with respect to an adamantane reference specimen (1H adamantane δ = 1.82 ppm) at 25 °C, and the polymer h, i peaks at 60 °C (Fig. 2b). All spectra were recorded at a MAS frequency of 55 kHz. The longitudinal relaxation time (T1) was determined at 25 and 60 °C by fitting peak areas from saturation recovery experiments in order to determine the optimal recycle delay between scans (Supplementary Table S1). 1D 1H spectra were then recorded using a single-pulse sequence with a 90° pulse of 2.4 μs. The spectra were averaged over 16 and 512 scans at 25 and 60 °C, respectively, with the recycle delay set to ≥5T1. Pneumatic damping of the magnet was essential to reduce artefacts caused by external vibrations.

Solid-state CPMG NMR spectroscopy

CPMG experiments were carried out at a MAS frequency of 55 kHz using a CPMG49,50 pulse sequence with perfect echoes78, in which a 90° excitation pulse of length 2.4 μs was followed by a train of 180° echo pulses of length 4.8 μs and a 90° refocusing pulse of length 2.4 μs, with an echo delay time (τ), expressed as an integral number of rotor periods (rp) (Fig. 6). The recovery time was set to 1.3 T1. Pseudo 2D spectra were recorded for fixed τ and an increasing number (n) of echoes according to Table 1. The low concentration of the supramolecular end groups (2 wt%) meant that 128–512 scans were required for 1H detection at large τ and n. Four dummy scans were performed prior to each experiment, after which 512 transients were accumulated at 25 °C and 60 °C, respectively. The pulse sequences are available upon request.

Spectral processing and deconvolution

All spectra were processed with the TopSpin (Bruker) software, and the open source software DMFIT71 was used to deconvolute the processed spectra in the region δ = 6–12 ppm (end-group peaks) and δ = 0–6 ppm (polymer peaks). Table 2 gives the peak assignment and δ for all peaks used for the fits in the region δ = 6–12 ppm. For the spectra recorded at 25 °C, a total of seven peaks were selected for the deconvolution of the end group peaks: NH2 and NH3 between 8.7 and 10 ppm, NH1 at about 8 ppm, three NHweak peaks between 7.0 and 7.7 ppm, and the polymer peak c, which is assumed to account for overlap with contributions from the polymer backbone (Fig. 3b). The assignment of NH1, NH2, and NH3 was based on solution-phase spectra, in which the amides gave rise to two overlapping peaks (NH2 and NH3) and a third, well-separated peak (NH1) shifted by about δ = –0.5 ppm relative to the former peaks (Fig. 2b). The NHweak peaks were identified from solid-state spectra recorded at various temperatures between 25 and 60 °C, which showed the broad peak present at δ = 7.0–7.7 ppm at 25 °C (Supplementary Fig. S7) to transform into three distinct, sharp peaks in the same region at temperatures above about 50 °C. In the spectra recorded at 60 °C, the polymer peak c no longer extended beyond δ = 6 ppm, because the PCL matrix was molten and its FWHM was consequently reduced. Moreover, there was no clear evidence of a broad NH1 peak in these spectra, presumably because dissociation occurred at a timescale of τ < 4 rp. We therefore reduced the number of peaks used for the deconvolution of the spectra recorded at 60 °C to five: NH2 and NH3 at 9.6 ppm and 9.0 ppm, and the three NHweak peaks at δ = 7.3–7.6 ppm.

A Gaussian fit was used for the NH2 and NH3 peaks, and a Lorentzian fit for all other end-group peaks. The peak positions were assumed to remain unchanged after the first fit for each temperature and τ dataset, while the FWHM and amplitude were adjusted. To deconvolute the polymer backbone peaks c, e, h, i, and j in the spectral region δ = 0–6 ppm, a combined Gaussian and Lorentzian fit was used for each peak at 25 °C, and a single Lorentzian fit for peak d, resulting in a total of nine peaks (h and i appear at the same position). At 60 °C, Lorentzian fits were sufficient for peaks c, d, e, h, i, and j, because the PCL matrix was fully molten.

Fitting to the Carver-Richards Model

To obtain dissociation rate constants, kd, we fitted the R2 data obtained from the CPMG experiments for the peaks assigned to NH2 + NH3, to the Carver–Richards equation73,74,75. In the case of a fast two-site exchange between aggregated (A) and dissociated (D) state of the amide moieties, the Carver–Richards model simplifies to Eq. 2, where R2,0 is the transverse relaxation rate in the absence of dynamics, kd is the rate constant for the exchange from state A to D, and ɸ = pA∙pD∙Δω2, where pA and pD are the fractions of aggregated and dissociated amide groups, respectively, and Δω is the difference in resonance frequency of the peaks associated with the two species73. In absence of well-distinguishable peaks for the two states, indicating a fast exchange according to Carver–Richards, these latter three parameters cannot be obtained separately and are thus combined in ɸ.

2D exchange spectroscopy experiments

The exchange spectroscopy (EXSY) experiment was conducted on a 900 MHz Bruker wide bore spectrometer (21.1 T) equipped with an Avance Neo console and a 1.3 mm HX double resonance CPMAS probe. The samples were packed into 1.3 mm zirconia rotors under ambient conditions. The rotor was spun at 55 kHz spinning speed using dry nitrogen gas. The pulse sequence consisted of three 90° pulses of 1.0 μs which were separated by an incremented evolution period (rotor synchronized increments of 67 μs) and a mixing time of 20 ms. 128 transients were cumulated for each of the 910 slices constituting the indirect dimension. The recycle delay was set to 3.6 s, which is equivalent 1.3T1 of the slowest relaxing species.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study is available within the paper and its Supplementary Information file. All other information is available upon request.

Code availability

The pulse sequences are available upon request.

References

Webber, M. J. & Tibbitt, M. W. Dynamic and reconfigurable materials from reversible network interactions. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7, 541–556 (2022).

Voorhaar, L. & Hoogenboom, R. Supramolecular polymer networks: hydrogels and bulk materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 4013–4031 (2016).

Peng, H.-Q. et al. Supramolecular polymers: recent advances based on the types of underlying interactions. Prog. Polym. Sci. 137, 101635 (2023).

Yanagisawa, Y., Nan, Y., Okuro, K. & Aida, T. Mechanically robust, readily repairable polymers via tailored noncovalent cross-linking. Science 359, 72–76 (2018).

Cordier, P., Tournilhac, F., Soulié-Ziakovic, C. & Leibler, L. Self-healing and thermoreversible rubber from supramolecular assembly. Nature 451, 977–980 (2008).

Lai, J.-C. et al. Thermodynamically stable whilst kinetically labile coordination bonds lead to strong and tough self-healing polymers. Nat. Commun. 10, 1164 (2019).

Huang, Z. et al. Highly compressible glass-like supramolecular polymer networks. Nat. Mater. 21, 103–109 (2022).

Burnworth, M. et al. Optically healable supramolecular polymers. Nature 472, 334–337 (2011).

Song, P. & Wang, H. High-performance polymeric materials through hydrogen-bond cross-linking. Adv. Mater. 32, 1901244 (2020).

Yang, H., Ghiassinejad, S., van Ruymbeke, E. & Fustin, C.-A. Tunable interpenetrating polymer network hydrogels based on dynamic covalent bonds and metal–ligand bonds. Macromolecules 53, 6956–6967 (2020).

Grindy, S. C. et al. Control of hierarchical polymer mechanics with bioinspired metal-coordination dynamics. Nat. Mater. 14, 1210–1216 (2015).

Chen, H. & Tong, K. The contributions of supramolecular kinetics to dynamics of supramolecular polymers. Chem. Plus Chem. 87, e202200279 (2022).

Sijbesma, R. P. et al. Reversible polymers formed from self-complementary monomers using quadruple hydrogen bonding. Science 278, 1601–1604 (1997).

Lange, R. F. M., Van Gurp, M. & Meijer, E. W. Hydrogen-bonded supramolecular polymer networks. J. Polym. Sci. Part Polym. Chem. 37, 3657–3670 (1999).

Hirschberg, J. H. K. K. et al. Supramolecular polymers from linear telechelic siloxanes with quadruple-hydrogen-bonded units. Macromolecules 32, 2696–2705 (1999).

Cortese, J., Soulié-Ziakovic, C., Cloitre, M., Tencé-Girault, S. & Leibler, L. Order–disorder transition in supramolecular polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 19672–19675 (2011).

Aida, T., Meijer, E. W. & Stupp, S. I. Functional supramolecular polymers. Science 335, 813–817 (2012).

Görl, D. et al. Supramolecular modification of sustainable high-molar-mass polymers for improved processing and performance. Nat. Commun. 16, 217 (2025).

Marco-Dufort, B., Iten, R. & Tibbitt, M. W. Linking molecular behavior to macroscopic properties in ideal dynamic covalent networks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 15371–15385 (2020).

Yan, T., Schröter, K., Herbst, F., Binder, W. H. & Thurn-Albrecht, T. Unveiling the molecular mechanism of self-healing in a telechelic, supramolecular polymer network. Sci. Rep. 6, 32356 (2016).

Wubbenhorst, M., van Turnhout, J., Folmer, B. J. B., Sijbesma, R. P. & Meijer, E. W. Complex dynamics of hydrogen bonded self-assembling polymers. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 8, 365–372 (2001).

Xing, K. et al. Hydrogen-bond strength changes network dynamics in associating telechelic PDMS. Soft Matter 14, 1235–1246 (2018).

Mordvinkin, A. et al. Hierarchical sticker and sticky chain dynamics in self-healing butyl rubber ionomers. Macromolecules 52, 4169–4184 (2019).

Ge, S. et al. Unravelling the mechanism of viscoelasticity in polymers with phase-separated dynamic bonds. ACS Nano 16, 4746–4755 (2022).

Gold, B. J. et al. The microscopic origin of the rheology in supramolecular entangled polymer networks. J. Rheol. 61, 1211–1226 (2017).

Gold, B. J. et al. Importance of compact random walks for the rheology of transient networks. ACS Macro Lett. 6, 73–77 (2017).

Rubinstein, M. & Semenov, A. N. Thermoreversible gelation in solutions of associating polymers. 2. Linear Dynamics. Macromolecules 31, 1386–1397 (1998).

Yount, W. C., Loveless, D. M. & Craig, S. L. Strong means slow: dynamic contributions to the bulk mechanical properties of supramolecular networks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 2746–2748 (2005).

Yount, W. C., Loveless, D. M. & Craig, S. L. Small-molecule dynamics and mechanisms underlying the macroscopic mechanical properties of coordinatively cross-linked polymer networks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 14488–14496 (2005).

Li, C.-H. et al. A highly stretchable autonomous self-healing elastomer. Nat. Chem. 8, 618–624 (2016).

Ortony, J. H. et al. Internal dynamics of a supramolecular nanofibre. Nat. Mater. 13, 812–816 (2014).

Albertazzi, L. et al. Probing exchange pathways in one-dimensional aggregates with super-resolution microscopy. Science 344, 491–495 (2014).

Bochicchio, D., Salvalaglio, M. & Pavan, G. M. Into the dynamics of a supramolecular polymer at submolecular resolution. Nat. Commun. 8, 147 (2017).

Sivakova, S., Bohnsack, D. A., Mackay, M. E., Suwanmala, P. & Rowan, S. J. Utilization of a combination of weak hydrogen-bonding interactions and phase segregation to yield highly thermosensitive supramolecular polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 18202–18211 (2005).

Samanta, S., Kim, S., Saito, T. & Sokolov, A. P. Polymers with dynamic bonds: adaptive functional materials for a sustainable future. J. Phys. Chem. B 125, 9389–9401 (2021).

Shikata, T., Ogata, D. & Hanabusa, K. Viscoelastic behavior of supramolecular polymeric systems consisting of N,N‘,N“-Tris(3,7-dimethyloctyl)benzene-1,3,5-tricarboxamide and n-Alkanes. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 508–514 (2004).

Jangizehi, A., Ahmadi, M. & Seiffert, S. Dynamics of supramolecular associative polymer networks at the interplay of chain entanglement, transient chain association, and chain-sticker clustering. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 57, 1209–1223 (2019).

Jangizehi, A., Ahmadi, M. & Seiffert, S. Emergence, evidence, and effect of junction clustering in supramolecular polymer materials. Mater. Adv. 2, 1425–1453 (2021).

Reif, B., Ashbrook, S. E., Emsley, L. & Hong, M. Solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Nat. Rev. Methods Primer 1, 1–23 (2021).

Seifrid, M., Reddy, G. N. M., Chmelka, B. F. & Bazan, G. C. Insight into the structures and dynamics of organic semiconductors through solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 910–930 (2020).

Brunner, E. & Rauche, M. Solid-state NMR spectroscopy: an advancing tool to analyse the structure and properties of metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Sci. 11, 4297–4304 (2020).

Brown, S. P. & Spiess, H. W. Advanced solid-state NMR methods for the elucidation of structure and dynamics of molecular, macromolecular, and supramolecular systems. Chem. Rev. 101, 4125–4156 (2001).

R. Chierotti, M. & Gobetto, R. Solid-state NMR studies of weak interactions in supramolecular systems. Chem. Commun. 0, 1621–1634 (2008).

Nishiyama, Y., Hou, G., Agarwal, V., Su, Y. & Ramamoorthy, A. Ultrafast magic angle spinning solid-state NMR spectroscopy: advances in methodology and applications. Chem. Rev. 123, 918–988 (2023).

Samoson, A., Tuherm, T. & Gan, Z. High-field high-speed MAS resolution enhancement in 1H NMR spectroscopy of solids. Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson. 20, 130–136 (2001).

Hansen, M. R., Graf, R. & Spiess, H. W. Solid-state NMR in macromolecular systems: insights on how molecular entities move. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 1996–2007 (2013).

Steigel, A. Mechanistic studies of rearrangements and exchange reactions by dynamic NMR spectroscopy. In Dynamic NMR Spectroscopy (eds Steigel, A. & Spiess, H. W) 1–53 (Springer, 1978).

Schanda, P. & Ernst, M. Studying dynamics by magic-angle spinning solid-state NMR spectroscopy: principles and applications to biomolecules. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 96, 1–46 (2016).

Carr, H. Y. & Purcell, E. M. Effects of diffusion on free precession in nuclear magnetic resonance experiments. Phys. Rev. 94, 630–638 (1954).

Meiboom, S. & Gill, D. Modified spin‐echo method for measuring nuclear relaxation times. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 29, 688–691 (2004).

Baldwin, A. J. & Kay, L. E. NMR spectroscopy brings invisible protein states into focus. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 808–814 (2009).

Salvi, N., Ulzega, S., Ferrage, F. & Bodenhausen, G. Time scales of slow motions in ubiquitin explored by heteronuclear double resonance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 2481–2484 (2012).

Tollinger, M., Sivertsen, A. C., Meier, B. H., Ernst, M. & Schanda, P. Site-resolved measurement of microsecond-to-millisecond conformational-exchange processes in proteins by solid-state NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 14800–14807 (2012).

Ma, P. et al. Probing transient conformational states of proteins by solid-state R1ρ relaxation-dispersion NMR spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 4312–4317 (2014).

Anthis, N. J. & Clore, G. M. Visualizing transient dark states by NMR spectroscopy. Q. Rev. Biophys. 48, 35–116 (2015).

Lewandowski, J. R. Advances in solid-state relaxation methodology for probing site-specific protein dynamics. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 2018–2027 (2013).

Lamley, J. M. et al. Solid-state NMR of a protein in a precipitated complex with a full-length antibody. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 16800–16806 (2014).

Yamauchi, K., Kuroki, S., Fujii, K. & Ando, I. The amide proton NMR chemical shift and hydrogen-bonded structure of peptides and polypeptides in the solid state as studied by high-frequency solid-state 1H NMR. Chem. Phys. Lett. 324, 435–439 (2000).

Sidhu, A., Surolia, A., Robertson, A. D. & Sundd, M. A hydrogen bond regulates slow motions in ubiquitin by modulating a β-turn flip. J. Mol. Biol. 411, 1037–1048 (2011).

Hansen, M. R., Graf, R. & Spiess, H. W. Interplay of structure and dynamics in functional macromolecular and supramolecular systems as revealed by magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Chem. Rev. 116, 1272–1308 (2016).

Spiess, H. W. 50th anniversary perspective: the importance of NMR spectroscopy to macromolecular science. Macromolecules 50, 1761–1777 (2017).

Pavlović, R. Z., Egner, S. A., Palmer, L. C. & Stupp, S. I. Supramolecular polymers: dynamic assemblies of “dancing” monomers. J. Polym. Sci. 61, 870–880 (2023).

Schnell, I. et al. Quadruple hydrogen bonds of ureido-pyrimidinone moieties investigated in the solid state by 1 H double-quantum MAS NMR spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 4, 3750–3758 (2002).

Mordvinkin, A., Döhler, D., Binder, W. H., Colby, R. H. & Saalwächter, K. Terminal flow of cluster-forming supramolecular polymer networks: single-chain relaxation or micelle reorganization? Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 127801 (2020).

Croisier, E. et al. A toolbox of oligopeptide-modified polymers for tailored elastomers. Nat. Commun. 5, 4728 (2014).

Gimenez, J., Cassagnau, P. & Michel, A. Bulk polymerization of ε-caprolactone: rheological predictive laws. J. Rheol. 44, 527–547 (2000).

Tang, X. & Chen, E. Y.-X. Toward infinitely recyclable plastics derived from renewable cyclic esters. Chem 5, 284–312 (2019).

Stempfle, F., Ortmann, P. & Mecking, S. Long-chain aliphatic polymers to bridge the gap between semicrystalline polyolefins and traditional polycondensates. Chem. Rev. 116, 4597–4641 (2016).

Aggeli, A. et al. Hierarchical self-assembly of chiral rod-like molecules as a model for peptide β-sheet tapes, ribbons, fibrils, and fibers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 11857–11862 (2001).

Thiele, S. et al. Polymer-bridged nanofibrils in a high-molar-mass polyester via co-assembly of benzenetricarboxamide end groups and additive. Org. Chem. Front. https://doi.org/10.1039/D5QO00087D (2025).

Massiot, D. et al. Modelling one- and two-dimensional solid-state NMR spectra. Magn. Reson. Chem. 40, 70–76 (2002).

Le Marchand, T. et al. 1H-detected biomolecular NMR under fast magic-angle spinning. Chem. Rev. 122, 9943–10018 (2022).

Palmer, A. G. I. NMR characterization of the dynamics of biomacromolecules. Chem. Rev. 104, 3623–3640 (2004).

Carver, J. P. & Richards, R. E. A general two-site solution for the chemical exchange produced dependence of T2 upon the Carr-Purcell pulse separation. J. Magn. Reson. 1969 6, 89–105 (1972).

Otten, R., Villali, J., Kern, D. & Mulder, F. A. A. Probing microsecond time scale dynamics in proteins by methyl 1H Carr−Purcell−Meiboom−Gill relaxation dispersion NMR measurements. Application to activation of the signaling protein NtrCr. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 17004–17014 (2010).

Söntjens, S. H. M., Sijbesma, R. P., van Genderen, M. H. P. & Meijer, E. W. Stability and lifetime of quadruply hydrogen bonded 2-Ureido-4[1H]-pyrimidinone dimers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 7487–7493 (2000).

Kurauskas, V. et al. Slow conformational exchange and overall rocking motion in ubiquitin protein crystals. Nat. Commun. 8, 145 (2017).

Aguilar, J. A., Nilsson, M., Bodenhausen, G. & Morris, G. A. Spin echo NMR spectra without J modulation. Chem. Commun. 48, 811–813 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by SNSF BRIDGE program (grant agreement no. 40B2-0_211501). S.T. would like to thank B. Tiberghien for the synthesis of mPCL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.F. and S.T. developed the research concept. L.P. and S.T. designed and performed the NMR experiments. S.T. carried out the FTIR, rheometry, and DSC measurements, and analyzed all data. S.T., C.J.G.P. and H.F. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Toshikazu Miyoshi, Kay Saalwächter for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thiele, S., Plummer, C.J.G., Piveteau, L. et al. Dynamics of hydrogen-bonded end groups in bulk polymers revealed by solid-state NMR spectroscopy relaxation dispersion experiments. Commun Chem 8, 217 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01597-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01597-w