Abstract

Electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction (CO2RR) in aqueous systems provides a sustainable pathway to convert CO2 into valuable chemicals and fuels. However, the limited solubility and slow diffusion of CO2 in aqueous electrolyte impose significant mass transfer barriers, particularly at high current densities. This study introduces a nanobubble-infused electrolyte strategy that leverages the unique properties of nanobubbles, including localized CO2 enrichment, enhanced diffusion, and micro-convection to overcome these limitations. Compared to conventional CO2-saturated electrolytes, the nanobubble-infused electrolytes achieve a 10-fold increase in the volumetric mass transfer coefficient and a 42.3% increase in the limiting current density. Implementing this approach with a zero-gap liquid-fed electrolyzer featuring a hydrophilic diffusion medium further enhances mass transfer, yielding an additional 28% increase in limiting current density. Mechanistic insights from multiphysics simulations reveal that nanobubbles enhance CO2 availability near the catalyst, reduce overpotentials, and improve CO2RR selectivity by suppressing hydrogen evolution. By validating this scalable and robust approach across different catalysts, this work establishes nanobubble-infused electrolytes as a universal solution for addressing mass transfer challenges independent of catalyst choice in liquid-fed CO2RR and paves the way for industrial-scale CO2 conversion technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction reaction (CO2RR) in aqueous systems has emerged as a promising route for converting CO2 into valuable chemicals and fuels, supporting sustainable carbon utilization1,2,3,4. However, mass transfer limitations, driven by the inherent low solubility of CO2 in water ( ~ 33 mM under ambient conditions) and slow diffusion rates, remain a critical barrier to achieving high reaction rates and selectivity, particularly at high current densities5,6. These limitations lead to CO2 depletion zones near the catalyst surface, increasing concentration overpotentials and reducing product selectivity7,8,9,10. Thus, improving mass transfer in aqueous CO2RR systems is crucial for enhancing reaction rates and achieving high product yields11. Various studies have explored strategies to overcome CO2 mass transfer limitations12, such as increasing system pressure or lowering the operating temperature, which can enhance CO2 solubility13,14,15,16,17. For instance, operating a CO2R electrolyzer at 9.5 bar increased the limiting current density from 21 to 286 mA cm-2 compared to operation at 1 bar18. Similarly, reducing the operating temperature from 30 °C to 0 °C increased the CO2 concentration from 28.6 to 69.3 mM17. However, these methods can decrease reaction activity (e.g., lower temperatures reduce catalytic activity)19, while high-pressure conditions require more complex equipment and increase the risk of salt precipitation, which can limit stable operation and reduce the device lifetime20,21. Therefore, alternative methods are needed to improve mass transfer without compromising simplicity and long-term stability22.

One emerging solution is using nanobubbles, i.e., gas bubbles with diameters typically in the tens to hundreds of nanometers23,24,25. Nanobubbles possess unique properties, i.e., localized CO2 enrichment, enhanced gas-to-solution transfer, and micro-convection, making them well-suited to mitigating diffusion limitations in aqueous CO2RR systems. The mass transfer enhancement mechanisms are illustrated in Fig. 1: i) Localized CO2 Enrichment: Nanobubbles act as stable, localized CO2 reservoirs, providing a continuous supply of CO2 near the catalyst surface and hence leading to an increased effective solubility of CO2. ii) Enhanced gas-to-solution transfer: The large surface-area-to-volume ratio of nanobubbles facilitates faster CO2 exchange between the gas phase and the electrolyte, improving diffusion and reducing the formation of depletion zones during CO2RR. iii) Micro-Convection: Nanobubbles can induce localized mixing, enhancing CO2 transport to the catalyst and improving overall mass transfer, especially in diffusion-limited regimes26,27,28. Previous studies on nanobubbles in water treatment, flotation, and catalysis have demonstrated their potential to improve mass transfer and reaction efficiency29,30,31. In electrochemical systems, nanobubbles have shown the ability to enhance gas-phase transport by providing sustained CO2 availability and improving reaction kinetics, making them an attractive solution for overcoming the inherent mass transfer limitations in aqueous CO2RR32,33. However, research into their application in aqueous CO2RR remains limited, particularly in understanding their role in addressing mass transfer limitations under high-performance conditions. Additionally, the interaction between nanobubbles and different catalysts or electrolytes remains underexplored, raising questions about the universality of their benefits.

In this study, we introduce a nanobubble-infused electrolyte strategy designed to address mass transfer limitations in aqueous CO2 electro-reduction to CO. By leveraging the unique properties of nanobubbles, i.e., localized CO2 enrichment, enhanced diffusion, and micro-convection, we investigate their role in enhancing CO2 solubility, transport, and reaction efficiency. Using Ag nanoparticles as a model catalyst, we systematically explore key parameters, including CO2 concentration, mass transfer coefficients, and the buffer capacity of nanobubbles (see Methods), to validate their impact on device performance. We conducted experiments in two electrochemical configurations: an H-cell with a planar Ag cathode and a zero-gap liquid-fed electrolyzer using a commercially available Ag nanoparticle catalyst (see Methods). The zero-gap liquid-fed electrolyzer setup demonstrated a partial current density for CO production (jCO) that was 60% higher than that observed in the planar H-cell configuration, attributed to the increased catalyst surface area and enhanced CO2 availability near the reaction interface. Using a higher-performing catalyst in the zero-gap liquid-fed electrolyzer setup, the polarization curves shifted to lower operating voltages, indicating improved reaction kinetics. However, the limiting current density remained unaffected, reflecting the mass transfer constraints imposed by the diffusion medium. This work provides a comprehensive investigation into the potential of nanobubble-infused electrolytes to address mass transfer challenges in aqueous CO2RR, presenting a scalable solution to improve CO2 conversion efficiency, potentially applicable for industrial implementation.

Results and discussion

Typically, CO2 gas bubbling into the solution produces visible macro-micro bubbles (diameter in the range of 1 µm to 10 mm) that quickly rise to the surface, partially dissolving to form aqueous CO2(aq), as shown in Fig. 1. The dissolved CO2 then diffuses through the bulk solution and the diffusion layer before reaching the electrode surface, where the electrochemical CO2 reduction occurs. The transport of CO2(aq) in the diffusion layer represents the major transport barrier. In the nanobubble case, the stable nanobubble, generated using the cavitation method in this study, can penetrate the diffusion layer, driven by the concentration difference of nanobubbles within the diffusion layer. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the nanobubbles enhance CO2RR by serving as stable, localized CO2 reservoirs that increase apparent CO2 solubility, facilitating faster CO2 gas-to-solution transfer due to their high surface-area-to-volume ratio and inducing micro-convection that improves mass transfer in diffusion-limited conditions. These combined effects substantially increase the availability of CO2 for the CO2RR, particularly in diffusion-limited regions under high current densities where efficient reactions require a continuous supply of CO2. By increasing CO2 solubility and promoting efficient mass transfer at the gas-liquid interface, nanobubbles can support sustained reaction rates and improved stability, making them promising for large-scale CO2 electroreduction applications. CO2 nanobubbles in solution typically follow Brownian motion34, but CO2 consumption during CO2RR creates a localized concentration gradient from bulk to electrode, causing CO2 nanobubbles to diffuse and transport toward the electrode surface. The mass transfer of non-charged CO2(aq) can be described by the following simplified Nernst-Planck equation35:

where \({N}_{{\mbox{C}}{{\mbox{O}}}_{2},{\mbox{aq}}}\) is the local flux of CO2(aq), \({D}_{{\mbox{C}}{{\mbox{O}}}_{2,}{\mbox{aq}}}^{{\mbox{eff}}}\) is the effect diffusivity of CO2. Given that a one-dimensional mass transfer process is considered, the contribution of the micro-convection effect induced by nanobubbles to the mass transfer process can be represented by an equivalent mass transfer coefficient km. Therefore, the convective term is simplified as km cCO2,aq and incorporated into the overall flux equation (see Supplementary Note S2 for detailed model description). In addition, a separate equation was solved for the nanobubble transport considering only diffusion, i.e., neglecting the additional transport due to micro-convection, due to

where \({N}_{{\mbox{C}}{{\mbox{O}}}_{2},{\mbox{NB}}}\) is the flux of nanobubble, \({D}_{{\mbox{C}}{{\mbox{O}}}_{2,}{\mbox{NB}}}^{{\mbox{eff}}}\) is the effective nanobubble diffusion coefficient can be estimated based on Einstein-Stokes equation (see Supplementary Note S2 for details). The mass transfer between gaseous bubble and solution can be described by a mass source/sink term accounting for local CO2(aq) enrichment due to nanobubble (See Supplementary Note S2 for details).

To understand the mass transfer enhancement as a result of utilizing CO2 nanobubble-infused electrolyte for the liquid-based CO2RR, the physical characterizations of nanobubbles was performed. Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA), was utilized to visualize and analyze the nanobubble concentration (see Fig. 2a) and size distribution (see Fig. 2b) for three selected samples: i) the deionized water (noted as DI water case), ii) 0.1 KHCO3 blank electrolyte with macro-bubbled saturated CO2 (noted as reference case), and iii) 0.1 KHCO3 with nano-bubbled saturated CO2(noted as nanobubble case). The concentration of nanobubbles is defined as the number of nanobubbles present per unit volume of solution, typically expressed as the count per milliliter (mL) of liquid. The DI water case provides a baseline measurement to account for background particles, while the reference case with macro-bubbled CO2 offers a reference point for CO2 solubility and mass transfer characteristics without infused-nanobubbles. By comparing these two cases with the nanobubble case, where CO2 nanobubbles are infused into the electrolyte, we can isolate the specific effects of nanobubbles on CO2 availability and transport properties. As shown in Fig. 2a, the DI water and reference cases were measured as baseline points, with particle concentrations of ~3.5×106 particles mL−1 and ~1.2×107 particles mL−1, respectively. In contrast, the nanobubble case showed an order of magnitude higher nanoparticle (bubble) concentration of approximately ~1×108 particles mL−1. The images of nanobubbles via NTA are exhibited in insets of Fig. 2a, where the bright dots represent particles (nanobubbles), confirming a significant higher bubble counts in the nanobubble case. Figure 2b further shows the bubble size distribution for all three cases. In the nanobubble case, the presence of two high peaks at 135 nm and 185 nm with nanobubble sizes primarily distributed between 100 and 200 nm. Note that although bubble sizes out of the range are observed, they only accounts of < 10% of the total bubble counts. We also studied the stability of the nanobubble for a wide range of standing time from 30 minutes (the first data point) to 7 days which revealed that the nanobubble concentration still shows a concentration of 3.2 ×107 particles mL−1 at the 7th day (Supplementary Fig. S5). As the nanobubble-infused electrolyte is directly utilized for CO2 reduction, the nanobubble concentration in our study is close to the fresh solution, i.e, ~1×108 particles mL−1.

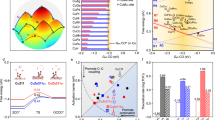

Particle concentration (a) and size distribution (b) of DI water, reference case (CO2 saturated - 0.1 M KHCO3), and nanobubble case (CO2 nanobubbles - 0.1 M KHCO3) with the inset image characterized by nanoparticle track analysis (NTA). c pH changes of the reference case bubbling CO2 gas and nanobubble case generating CO2 nanobubbles with time. d Volumetric mass transfer coefficient calculated at the first 100 mins. e Titration curves in 0.1 M KHCO3 compared with the nanobubble, reference, and blank cases (pure - 0.1 M KHCO3). f Buffer capacity evaluation at different pH values of various cases.

Figure 2c shows the pH variation as a function of bubbling time for both reference and nanobubble cases. Bubbling CO2 into the 0.1 M KHCO3 solution leads to gas dissolving and forming carbonic acid and resulting in pH drops. For all cases, the initial pH of the electrolyte was ~8.4. Upon reaching equilibrium after bubbling, the pH in the nanobubble case stabilized at 6.67, in contrast to the slightly higher value of 6.82 observed in the reference case. The pH increase in the nanobubble case indicates a higher CO2 saturation concentration, based on the Henderson-Hasselbalch theory. This equilibrium pH can be translated to be 33.8 mM dissolved CO2 in the reference case and 47.8 mM in the nanobubble case, confirming a greater dissolution of CO2 in the nanobubble environment (calculation detailed in Supplementary Note S1). Notably, the pH exhibited a sharper decline at the initial stage ( < ~ 100 minutes) for the nanobubble case, decreasing from 8.42 to 6.67 compared to the reference case (from 8.37 to 7.15). This is a direct indication of fast gas-to-solution transfer kinetics. The volumetric mass transfer coefficient (KLa), defined as the rate of mass transfer per unit concentration difference between the gas-liquid interface and the bulk phase can be used to quantify this fast gas-to-solution transfer. KLa was found to be 5.39 h−1 for the nanobubble case, in contrast to only 0.59 h−1 for the reference case, showing an approximately ten-fold enhancement (see Fig. 2d and detailed calculation in Supplementary Note S1). A similar result was also observed in the DI water based with the KLa of 3.52 h−1 in the nanobubble case and 0.19 h−1 in the reference case as shown in Supplementary Fig. S7.

CO2 nanobubbles can effectively support the carbonate-bicarbonate buffering system by increasing CO2 concentration and providing efficient CO2 dissolution interfaces. This improvement subsequently improves the buffer capacity, which is critical in maintaining pH stability within the diffusion layer, hence a relatively more stable micro-environment can be secured for CO2RR. The OH- generated during CO2R reacts with dissolved CO2 to form HCO3−/CO32, which are inactive for CO2R and suppress the kinetics of reaction. With buffer capacity, the buffering species (e.g., HCO3−/CO32−) rapidly neutralize locally generated OH- through acid-base equilibria (e.g., HCO3− + OH- → CO32− + H2O), effectively suppressing pH fluctuations near the catalyst surface. To assess this, we evaluated three solutions, 0.1 M KHCO3 (blank), the reference case (CO2-saturated KHCO3), and the nanobubble case (CO2 nanobubble-infused KHCO3), by titration with 1 M KOH. As illustrated in Fig. 2e, the solution in the nanobubble case exhibits a significantly greater resistance to pH changes induced by titration. For instance, to elevate the pH of the blank solution to 11, only 4.1 mmol of titrant is required. In contrast, the reference solution needs 7.3 mmol, while the nanobubble solution demands 12 mmol to achieve the same pH level. This led to peak buffer capacity for the nanobubble case to be 3.96 mmol pH-1 at a pH of ~10 (see Fig. 2f), compared to 2.51 mmol pH−1 for the reference case. Similar results can also be observed in the DI water case, further confirming the buffer capacity enhancement as a result of infusing CO2 nanobubble (see Supplementary Fig. S8).

To elucidate the impact of nanobubbles on enhancing mass transfer in CO2RR, we employed a combined experimental and simulation approach. Experimentally, a H-cell electrolyzer in a three-electrode configuration was utilized to demonstrate electrochemical performance enhancement because of mass transfer improvement due to nanobubbles. The H-cell electrolyzer is formed by a planar silver (Ag) cathode, a planar Pt anode, and the 0.1 M KHCO3 electrolyte (see Methods and Fig. S9). Note that the catholyte can be macro-bubbled (reference case) or nano-bubbled (nanobubble case) with CO2 in 0.1 M KHCO3. Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) results (Fig. 3a) show that the nanobubble case significantly enhances total current density, particularly at higher potentials ( > 1.0 V vs. RHE). Note that all the potential analysis in the H-cell electrolyzer was subjected to 85% iR compensation. At −1.5 V vs. RHE, the total current density in the nanobubble system reached 38.8 mA cm−2, 39% higher than the reference case (27.9 mA cm−2). This enhancement can be an indication of the enhanced CO2 mass transfer. The CO partial current density and CO product selectivity were measured by chronopotentiometry (Supplementary Fig. S10). The CO limiting current density increased by 42.3%, from 14.9 mA cm-2 (reference case) to 21.2 mA cm-2 (nanobubble case, see Fig. 3b). This is also attributed to the enhanced local CO2 concentration in the nanobubble case suppressing the HER, thereby achieving higher CO product selectivity ( ~ 95%) in the Faradaic region of 1.1–1.3 V vs. RHE compared to that of the reference case ( ~ 85%) as shown in Fig. 3c. It is worth noting that nanobubbles have minor effects at low potentials, indicating that they do not impact the intrinsic activity of the electrochemical behavior. Instead, their primary role is to enhance mass transfer in the concentration polarization region (mass transfer limited region in Fig. 3b), with a more pronounced impact at higher current densities.

Electrochemical performance including the total current density (a), CO partial current density (b), and CO Faradaic efficiency (c) as a function of applied voltage with 85% iR compensation for the cases of reference and nanobubble. The results show both experimental and numerical predicted data for the H-cell with 0.1 M KHCO3 electrolyte and Ag planar cathode. d The applied voltage breakdown for reference and nanobubble cases. e CO2 and OH- concentration distributions of electrode interface as a function of current densities of CO2RR as well as the location of diffusion layer with the insert figure indicating the 1D model for diffusion layer. f CO2 flux analysis as a function of CO partial current density in nanobubble case.

Theoretically, we further developed a 1D multi-physics model (detailed in Supplementary Note S2 and Figs. S1–3) to explore the mechanisms underlying these observations (Fig. 3d–e). The model accounts for the mass transfer process in the diffusion layer by considering the nanobubble as an additional diffusive species. As seen in Fig. 3b, the model predicted CO partial current densities showed good agreement with the experimental results. The predicted concentration overpotential showed a reduction for the nanobubble case compared to the reference case (see Fig. 3d). For example, at a current density of 30 mA cm-2, the mass transfer overpotential, defined as \({\eta }_{{\mbox{m}}}=\frac{{RT}}{\alpha F}{\mathrm{ln}}(\frac{{c}_{{\mbox{CO}}2}}{{c}_{{\mbox{CO}}2}^{0}})\), which decreased from 291.1 mV in the reference case to 192.8 mV in the nanobubble case, corresponding to a reduction in energy losses from 21.3% to 14.9%. We also show the concentration profiles of OH− and CO2 at varying current densities. As shown in Fig. 3e, the red solid curve represents the CO2 concentration at the electrode interface in the nanobubble case, which exhibits a gradual decline and reaches complete consumption at a total current density of ~35 mA cm−2 (jCO = 21.2 mA cm−2, the limiting current density), in contrast to the reference case indicated by the blue curve, where complete consumption occurs at a total current density of 20 mA cm−2 (jCO = 14.9 mA cm−2, the limiting current density). This observation confirms the role of nanobubbles in enhancing CO2 concentration. Specifically, taking the current density of 20 mA cm−2 as an example, the CO2 concentration profile within the diffusion layer is shown in Fig. 3e. The CO2 concentration is saturated ( ~ 33 mM) in the bulk with a concentration gradient toward 0.3 mM (reference case) and 10.6 mM (nanobubble case) on the electrode surface (location = 0). The dashed lines in Fig. 3e illustrate the OH- concentration as a function of current density, revealing a narrower range from 0 to 4.0 mM in the nanobubble case (vs. 0 to 11.2 mM in the reference case) as the current density increases up to 30 mA cm-2. For the nanobubble case, CO2 transport occurs through two contributions (diffusion and micro-convection) as described by the Nernst-Planck equation (Eq. 1). Figure 3f demonstrates that elevating the current density to 10 mA cm-2 induces a proportional increase in CO2 flux (reaching 1.34 mmol m−2 s−1), attributable to accelerated CO2 consumption at the reaction interface. Notably, micro-convection emerges as the predominant transport pathway under these conditions. Quantitative analysis reveals that at a CO partial current density of 10 mA cm−2, micro-convection contributes 67% (0.89 mmol m−2 s−1) of the total mass flux.

To further enhance CO2RR performance, we conducted zero-gap liquid-fed electrolyzer tests, motivated by the higher catalyst surface area available in porous electrodes compared to planar electrodes in H-cell and significantly lower cell voltage due to low internal Ohmic resistance. Unlike the commonly studied gas-fed membrane-electrode assembly (MEA), the zero-gap liquid-fed electrolyzer requires a hydrophilic diffusion medium (DM) to ensure fully wetted pores for dissolved CO2 and infused CO2 nanobubble to be transported to the catalyst layer (CL). For reference, we also include the hydrophobic DM case (noted as Case 1) and two other hydrophilic cases with the benchmark nano-Ag (noted as Case 2) and a higher-selectivity catalyst (noted as Case 3). The experimental details are shown in Supplementary Fig. S11 and Methods. The studied 3 cases are summarized as follows:

Case 1: Hydrophobic DM (5 wt.% PTFE) with nano-Ag catalyst.

Case 2: Hydrophilic DM (1 wt.% PTFE) with nano-Ag catalyst.

Case 3: Hydrophilic DM (1 wt.% PTFE) with NiPC-OMe MDE catalyst.

As shown in Fig. 4a–c, DM hydrophobicity plays a critical role in determining the transport of nanobubbles and electrolytes to the catalyst interface. The contact angle of the hydrophobic DM in Case 1 was measured at 145° (Supplementary Fig. S12), significantly hindering the transport of nanobubbles and liquid to the catalyst layer. In contrast, the hydrophilic DM in Cases 2 and 3 exhibited a contact angle of 63° (Supplementary Fig. S12), allowing easier transport of nanobubbles and liquid to the reaction interface due to reduced flow resistance.

chSchematic illustrations of porous electrodes submerged in the nanobubble-infused electrolyte at the construction of hydrophobic DM coating with nano-Ag catalyst (a), hydrophilic DM coating with nano-Ag catalyst (b), and hydrophilic DM coating with NiPC-OMe MDE catalyst (c). Characteristics of electrochemical performance with CO partial current density (d) and CO Faradaic efficiency (e) in reference (dash lines) and nanobubble (solid lines) case with IrO2-Ti anode using 0.1 M KHCO3 as the anolyte for CO2 conversion into CO in the zero-gap liquid-fed electrolyzer. f Water saturation and CO2 concentration distribution in the zero-gap liquid-fed electrolyzer for different structures of cathode electrode via simulation prediction (Case 1 and Case 2).

As shown in Fig. 4d, utilizing the nanobubble-infused electrolyte results in an increase in the limiting current density (jCO, lim) compared to the reference case (Case 1 and Case 2 show the 29.2% and 46.6% increase, respectively), which confirms that nanobubbles enhance mass transfer performance in zero-gap liquid-fed electrolyzer. Case 2 with a hydrophilic DM demonstrated a higher limiting current density of 34.6 mA cm-2 compared to 27.0 mA cm-2 in Case 1, which featured a hydrophobic DM (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Fig. S15). This improvement is attributed to more wetted DM surfaces due to the high hydrophilic nature, which supports more effective transport of nanobubbles and CO2 to the reaction interface, as confirmed by simulation results (Fig. 4f). As seen in Fig. 4f, at a cell voltage of 3 V, Case 2 exhibited a higher CO2 concentration across the porous electrodes compared to Case 1. This can be attributed to the hydrophilic DM in Case 2 having a higher water saturation (SL > 0.9 in DM) compared to Case 1 (SL < 0.4 in DM), which promotes CO2 mass transfer, as CO2 can be supplied either in the dissolved aqueous form or as dispersed nanobubbles. While this large SL in DM for Case 2 led to a reduced CO Faradaic efficiency as seen in Fig. 4e. For instance, at 3 V, Case 1 achieved a CO Faradaic efficiency of 81.8%, whereas Case 2 only reached 63.2%.

To mitigate the HER observed in Case 2, the silver catalyst was replaced with a high-selectivity NiPC-OMe MDE catalyst, which exhibits a larger free energy barrier for *H adsorption36, forming Case 3 (see Methods, Fig. S13, and Supplementary Fig. S16). This modification significantly improved CO selectivity, as shown in Fig. 4e, where Case 3 achieved 98.9% CO selectivity at 2.5 V. Moreover, Case 3 exhibited superior catalytic kinetics, as reflected in the polarization curve (Fig. 4d). At a CO partial current density of 20 mA cm−2, the cell voltage for Case 3 was reduced by 410 mV compared to Case 2. Despite these enhancements, the limiting current density of Case 3 remained at 33.5 mA cm−2, similar to Case 2, due to the identical DM structure and corresponding mass transfer conditions. This again confirms that the nanobubble-infusion strategy is a universal mass transfer enhancement method for liquid-fed CO2RR independent of catalyst.

Discussion

This study demonstrates a nanobubble-infused electrolyte strategy to address mass transfer limitations in aqueous CO2 electroreduction systems. By leveraging the unique properties of nanobubbles, i.e., localized CO2 enrichment, enhanced gas-to-solution transfer, and micro-convection, we improved the mass transfer efficiency leading to higher limiting current density as well as CO2RR selectivity. The integration of nanobubbles into the electrolyte increased the volumetric mass transfer coefficient by an order of magnitude and improved the limiting current density by 42.3% in an H-cell electrolyzer compared to conventional CO2-saturated electrolytes. These enhancements were complemented by a 35.6% improvement in buffer capacity, enabling stable pH conditions near the catalyst interface to sustain high reaction rates. To validate the scalability and practical applicability of this approach, we integrated nanobubble technology into a zero-gap liquid-fed electrolyzer configuration, where a hydrophilic diffusion medium (DM) enhanced nanobubble transport and CO2 delivery to the catalyst surface. The nanobubble case showed a 46.6% improvement in limiting current density of CO compared to the macro-bubbled case. Furthermore, the hydrophilic DM increased limiting current density by 28% compared to hydrophobic DM due to better wetting of the DM for liquid electrolyte transport and hence the dissolved CO2 and infused nanobubbles. Importantly, combining nanobubble-infused electrolytes with a higher-selectivity NiPC-OMe MDE catalyst further suppressed HER (98.9% CO selectivity at 2.5 V), achieving a jlim,CO of ~35 mA cm-2 and lower cell voltage (3.0 V vs. 3.4 V at the jlim,CO) compared to the Ag-based catalyst. To conclude, the nanobubble-infused electrolyte strategy can be widely used in liquid-fed CO2RR for mass transfer enhancement, which is independent of catalyst with broader implications for other electrocatalytic systems reliant on efficient gas-liquid transport, such as nitrogen reduction and oxygen evolution reactions.

Methods

Experimental preparation

Case 2&3 carbon substrate consisted of hydrophobic MPL and hydrophilic DM

The GDE in Case 2 of this study is based on the substrate of hydrophilic DM (TGP-H-060) coating the hydrophobic MPL, which is made of 30 wt.% PTFE and 70 wt.% carbon black. The carbon black is dispersed in an ethanol solution, and then the mixed solution is subjected to ultrasonication for 40 min. The dropwise PTFE dispersion was added to the mix solution, and an ultrasonic treatment is performed for 60 min. The mixture solution would be sprayed on the DM via the spray gun on the 80°C hot platform and further sintered at 350 °C for 40 min under an argon protection. The carbon black loading for MPL was controlled at 1.0 mg cm−2.

Ag-NP electrode preparation

To prepare the gas diffusion electrode (GDE) used as the cathode, Ag nanoparticles (Ag-NPs) were applied to the catalyst layer through spray-coating on the MPL. Each GDE used in this study had dimensions of 1.5 × 1.5 cm2. Specifically, 3.2 mg of Ag-NP powder was first diluted in 2.5 mL of ethanol and subjected to high-power sonication. Next, 25 μL of ionomer solution (XA-9) was added to the mixture, which was then sonicated for an additional hour to achieve a uniform dispersion. The resulting solution was evenly spray-coated onto the carbon paper substrate, maintained at 80°C on a hot platform, to reach a target Ag-NP loading of approximately 0.5 mg cm−2.

NiPc-OMe electrode preparation

The molecularly dispersed electrocatalyst (MDE) sample (8.00 mg) was mixed in 3.6 mL Nafion solution (0.0325 wt.% in ethanol) and 0.4 mL PTFE solution (1%), and sonicated for 1 h to form MDE ink. 0.56 mL of the electrocatalyst ink was drop-dried onto a 1.5 × 1.5 cm2 Case 2&3 carbon substrates prepared before (loading: 0.5 mg cm−2). The working electrode was obtained by heating the catalyst-loaded carbon paper at 330 °C for 1 h under argon protection. Pure NiPc-OMe electrodes were prepared by dispersing NiPc-OMe in an XA-9 solution with 2 mg mL−1 and drop-dried on Case 2 carbon substrate with a loading of 0.5 mg cm−2.

IrO2-Ti anode preparation

The anodes were fabricated by depositing IrO2 onto titanium fiber felt through dip coating followed by thermal decomposition. Initially, the titanium fiber felt was rinsed with absolute ethanol and deionized water, then etched in oxalic acid at 90 oC for 3 hours to remove the surface oxide layer, exposing the titanium hydride beneath. After etching, the titanium fiber felt was immersed in an IrCl6 solution, dried at 100 °C in an oven for 10 minutes, and subsequently calcined in a furnace at 500 °C for 1 hour before being cooled naturally to room temperature. This dipping, calcination, and cooling procedure was repeated to achieve the desired loading of approximately 2 mg cm−2.

Nanobubbles generation

CO2 nanobubbles were generated by cavitation method using the batch recirculation nanobubble generator (LF300, NANOscientific) at a constant pressure of ~0.4 MPa. By controlling the flow of liquid and gas in a narrow space process, the size and number of controllable bubbles or bubble flows are formed. The pure CO2 gas was delivered to the generator at a gas flux of 15 sccm. All experiments were conducted with 1 L of deionized water and maintained the recirculation until the end of the electrochemical experiments.

Electrochemical configurations

The electrochemical experiments for CO2RR in the customized gastight H-type electrolyzer was divided by an anion exchange membrane (Sustainion® X37-50 grade RT) and employed a three-electrode configuration. This configuration consisted of an Ag planar working electrode, a Pt planar counter electrode, and an Ag/AgCl reference electrode, all immersed in a 0.1 M KHCO3 aqueous electrolyte with circulated flow of saturated CO2 or CO2 nanobubbles supplied during the experiment. Before each experiment, the Ag planar electrode was polished to a smooth surface using 1000-grit sandpaper.

The electrochemical experiments for CO2RR in the zero-gap liquid-fed electrolyzer with a two-electrode configuration were carried out using a custom-built electrolyzer cell. The homemade electrolyzer was constructed from two TA-2 grade titanium plates, each featuring serpentine channels to facilitate the transport of reactants and products, with an active area of 1.5 × 1.5 cm2. The anion exchange membrane (Sustainion® X37-50 grade RT) was sandwiched between the cathode (Ag-NP or NiPc-OMe electrode) and the IrO2-Ti felt-based anode, with two 0.25 mm thick PTFE gaskets used to hold the electrodes in place and to prevent gas and liquid leakage. The entire cell assembly was secured with six-bolt screws tightened to a torque of 6 N·m throughout the experiments.

Characterization method

Electrode characterization

The morphology and elemental composition of the porous electrode samples, both at the cross-section and surface, were examined using a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM, Carl Zeiss Microscopy Ltd., Sigma 300) equipped with integrated energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). Additionally, contact angle experiments were conducted using the sessile drop method on a video-based contact angle measurement system (Sindin, SDC-200SH) to assess the surface wettability of the samples.

Nanobubbles characterization

Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA, Nanosight NS300, Malvern) was employed to analyze the concentration and size distribution of CO2 nanobubbles. Each sample was tested 5 times with the detect threshold of 5 and camera level of 14, and then the average value was calculated from the results. Dynamic light scattering (DLS, Zetasizer Pro, Malvern) was used to measure the size distribution and stability of CO2 nanobubbles. The sample of three types: i) DI water case, ii) reference case – 1 L 0.1 M KHCO3 bubbling CO2 gas with 15 sccm for 100 mins, iii) 1 L 0.1 MKHCO3 generating CO2 nanobubbles with 15 sccm CO2 supplied for 100 mins were prepared for characterization. For the NTA test, 1 mL of the sample was extracted for each measurement.

Electrochemical measurements

All the electrochemical measurements were operated under an electrochemical workstation (Gamry, Reference 3000). The reference electrode potentials were converted to reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) with 85% iR in the three-electrode configuration with H-cell using the equation of \(E\left({{\rm{vs}}}.{{\rm{RHE}}}\right)=E\left({{\rm{vs}}}.{{\rm{Ag}}}/{{\rm{AgCl}}}\right)+{E}_{{{\rm{A}}}{{\rm{g}}}/{{\rm{AgCl}}}}^{{{\rm{o}}}}+0.059{pH}+\,0.197-85 \% \,i{R}_{u}.\)

CO2RR products analysis

The outlet gas from the electrolyzer in all experiments was sequentially passed through a drying bottle for dehydration, followed by a dry-type gas flow calibrator (Beijing Kean Laobao, DCal 500) to measure the volume flow rate of the gas mixture. The resulting gas mixture was then analyzed using an online gas chromatograph (GC, FULI INSTRUMENTS, GC9790Plus) equipped with Molecular Sieve 5 A Capillary Column, Hayesep A, and Porapak N columns, with argon as the carrier gas. A thermal conductivity detector (TCD) operating at 120 °C was used to quantify H2 concentration, while a flame ionization detector (FID) operating at 150 °C was employed for CO concentration analysis. The gas chromatograph was calibrated using gas mixtures with three known standard concentrations, and the calibration was performed by comparing the peak areas analyzed by the instrument. The Faradaic efficiency (FE) of gas products was calculated as follows:

where ni is the number of electrons transferred per mole of gaseous product i involved in the reaction, F is Faraday constant (96485 C mol−1), p0 is the standard atmospheric pressure (101.325 kPa), xi is the volume fraction of product i quantified by an online gas chromatograph in the cathodic gas mixture, v is the flow rate calculated by the dry-type gas volumetric flowmeter, jtotal is the total current recorded by electrochemical workstation, R is the ideal gas constant (8.314 J mol−1 K−1), and T is the temperature. All calculations were converted to the International System of Units.

Calculation of partial current density (ji) was determined using the following equation:

where A is the geometric active-area of working electrode.

Numerical calculation

CO2 concentration calculation

In the process of CO2 dissolution in aqueous solutions, particularly in buffered systems such as 0.1 M KHCO3, the dissolved CO2 concentration directly impacts the pH of the solution. Understanding the relationship between pH and CO2 concentration is crucial for quantifying CO2 dissolution under different conditions. The dissolved CO2 concentration at any pH during CO2 saturation and CO2 nanobubble in a 0.1 M KHCO3 solution was calculated in this study. The details for the calculation are shown in Supplementary Note S1.

Buffer capacity calculation

The buffer capacities of 0.1 M KHCO3 based blank case, reference case with saturated CO2, and CO2 nanobubble case were evaluated by titration using 1 M KOH. The buffer capacity (β) was quantified by,

where n is titration molar concentration of KOH and \(\Delta {pH}\) denotes the change in pH caused by the titration.

Multiphysics modeling

Two one-dimensional models of diffusion layer in H-cell electrolyzer and zero-gap liquid-fed electrolyzer were developed to simulate the relevant phenomena of the electrochemical CO2 reduction system, such as ions transport, charge transfer, homogeneous reactions and phase-transfer reactions, and mass transport. The details for the modeling are shown in Supplementary Note S2.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are provided in the paper and its Supplementary Information. The raw data for the figures in the paper are provided in Supplementary Data 1. Additional data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Zhang, W. et al. Dynamic bubbling balanced proactive CO2 capture and reduction on a triple-phase interface nanoporous electrocatalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 21335–21347 (2024).

Wen, G. et al. Continuous CO2 electrolysis using a CO2 exsolution-induced flow cell. Nat. Energy 7, 978–988 (2022).

Obasanjo, C. A. et al. High-rate and selective conversion of CO2 from aqueous solutions to hydrocarbons. Nat. Commun. 14, 3176 (2023).

Corral, D. et al. Bridging knowledge gaps in liquid- and vapor-fed CO2 electrolysis through active electrode area. Chem Catal 2, 3239–3253 (2022).

Xin, Z. et al. Metallocene implanted metalloporphyrin organic framework for highly selective CO2 electroreduction. Nano Energy 67, 104233 (2020).

Gao, D., Arán-Ais, R. M., Jeon, H. S. & Roldan Cuenya, B. Rational catalyst and electrolyte design for CO2 electroreduction towards multicarbon products. Nat. Catal. 2, 198–210 (2019).

Tan, Y. C., Lee, K. B., Song, H. & Oh, J. Modulating Local CO2 Concentration as a General Strategy for Enhancing C−C Coupling in CO2 Electroreduction. Joule 4, 1104–1120 (2020).

Lu, S. et al. Mass transfer effect to electrochemical reduction of CO2: Electrode, electrocatalyst and electrolyte. J. Energy Storage 52, 104764 (2022).

Lees, E. W., Mowbray, B. A. W., Parlane, F. G. L. & Berlinguette, C. P. Gas diffusion electrodes and membranes for CO2 reduction electrolysers. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7, 55–64 (2022).

Morrison, A. R. T. et al. Modeling the electrochemical conversion of carbon dioxide to formic acid or formate at elevated pressures. J. Electrochem. Soc. 166, 77–86 (2019).

Henckel, D. A. et al. Understanding Limitations in Electrochemical Conversion to CO at Low CO2 Concentrations. ACS Energy Lett 9, 3433–3439 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Non-isothermal CO2 electrolysis enables simultaneous enhanced electrochemical and anti-precipitation performance. Nat. Commun. 16, 4181 (2025).

Zhou, Y. et al. Advancements in electrochemical CO2 reduction reaction: A review on CO2 mass transport enhancement strategies. Chem. Eng. J. 486, 150169 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Electroreduction of CO2to formate on a copper-based electrocatalyst at high pressures with high energy conversion efficiency. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 7276–7282 (2020).

Qi, K. et al. Unlocking direct CO2 electrolysis to C3 products via electrolyte supersaturation. Nat. Catal. 6, 319–331 (2023).

Vos, R. E. & Koper, M. T. M. The effect of temperature on the cation-promoted electrochemical CO2 reduction on gold. ChemElectroChem 9, 1–11 (2022).

Henry, J. W. & Stone, R. W. An improved model calculating CO2 solubility in pure water and aqueous NaCl solutions from 273 to 533 K and from. Chem. Geol. 193, 257–271 (2003).

Lamaison, S. et al. High-Current-Density CO2-to-CO Electroreduction on Ag-Alloyed Zn Dendrites at Elevated Pressure. Joule 4, 395–406 (2020).

Löwe, A. et al. Influence of temperature on the performance of gas diffusion electrodes in the CO2 reduction reaction. ChemElectroChem 6, 4497–4506 (2019).

Morrison, A. R. T., Girichandran, N., Wols, Q. & Kortlever, R. Design of an elevated pressure electrochemical flow cell for CO2 reduction. J. Appl. Electrochem. 53, 2321–2330 (2023).

Endrödi, B. et al. Multilayer electrolyzer stack converts carbon dioxide to gas products at high pressure with high efficiency. ACS Energy Lett 4, 1770–1777 (2019).

Bagemihl, I., Bhatraju, C., Van Ommen, J. R. & Van Steijn, V. Electrochemical reduction of CO2 in tubular flow cells under gas-liquid taylor flow. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 10, 12580–12587 (2022).

Han, G. et al. A review and perspective on micro and nanobubbles: What They Are and Why They Matter. Miner. Eng. 189, 107906 (2022).

Li, J., Guo, J. & Dai, H. Probing dissolved CO2(aq) in aqueous solutions for CO2 electroreduction and storage. Sci. Adv. 8, 1–12 (2022).

Magdaleno, A. L. et al. Unlocking the potential of nanobubbles: achieving exceptional gas efficiency in electrogeneration of hydrogen peroxide. Small 20, 1–10 (2024).

Shin, D. et al. Growth dynamics and gas transport mechanism of nanobubbles in graphene liquid cells. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–6 (2015).

Bae, Y. et al. Nanobubble dynamics in aqueous surfactant solutions studied by liquid-phase transmission electron microscopy. Engineering 7, 630–635 (2021).

Zhou, L., Wang, S., Zhang, L. & Hu, J. ScienceDirect Generation and stability of bulk nanobubbles: A review and perspective. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 53, 101439 (2021).

Foudas, A. W. et al. Fundamentals and applications of nanobubbles: A review. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 189, 64–86 (2023).

Ye, S. et al. Boosting oxygen diffusion by micro-nano bubbles for highly-efficient H2O2 generation on air-calcining graphite felt. Electrochim. Acta 439, 1–8 (2023).

Wang, D., Yang, X., Tian, C., Lei, Z. & Kobayashi, N. Characteristics of ultra-fi ne bubble water and its trials on enhanced methane production from waste activated sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 273, 63–69 (2019).

Wu, K. et al. Formation of bismuth nanosheets on copper foam coupled with nanobubble technology for enhanced electrocatalytic CO2 reduction. J. Mater. Chem. A 12, 33972–33983 (2024).

Tomisaki, M., Natsui, K., Fujioka, S., Terasaka, K. & Einaga, Y. Unique properties of fine bubbles in the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide using boron-doped diamond electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 389, 138769 (2021).

Sharma, H. & Nirmalkar, N. Materials today: proceedings enhanced gas-liquid mass transfer coefficient by bulk nanobubbles in water. Mater. Today Proc. 57, 1838–1841 (2022).

Burdyny, T. et al. Nanomorphology-enhanced gas-evolution intensifies CO2 reduction electrochemistry. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 5, 4031–4040 (2017).

Jiang, Z. et al. Molecular Catalyst with Near 100% Selectivity for CO2 Reduction in Acidic Electrolytes. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2–9 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 52376191. The Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Commission under Grant No. 20231120185819001 and KCXST20221021111207017, the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation under Grant No. 2023A1515011595, Guangdong Major Project of Basic and Applied Basic Research (2023B0303000002), SUSTech High Level of Special Funds under grant No. G03034K001, and Guangdong grant under Grant No. 2021QN02L562 are also acknowledged for their support. Jieyang Li thanks the support from PhD Short-term Visiting Program of Southern University of Science and Technology during his stay at UCL. The computation in this work is supported by the Center for Computational Science and Engineering at Southern University of Science and Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.L. conceived the research concept and supervised the project. J.L., C.L., Z.H., and K.J. co-developed the experimental methodology and carried out nanobubble characterization, materials analysis, electrochemical measurements, and associated data interpretation. Z.J. and Y.L. designed and synthesized the catalyst. H.Z., J.C., T.S.M., and R.J. performed simulations and electrode structure analysis. J.L. prepared the initial draft of the manuscript. M.L., J.L., and all authors contributed to manuscript revision and approved the final version of the work. M.L. also acquired funding.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Mengran Li, Pengtao Xu, and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Luo, C., Zhang, H. et al. Nanobubble-infused electrolytes for enhanced mass transfer in liquid-fed CO2 electroreduction. Commun Chem 8, 251 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01645-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01645-5