Abstract

The design of efficient artificial light-harvesting antennas is essential for enabling the widespread use of solar energy. Natural photosynthetic systems offer valuable inspiration, but many rely on complex pigment–protein interactions and have limited spectral coverage, which pose challenges for rational design. Chlorosome mimics, which are self-assembling pigment aggregates inspired by green photosynthetic bacteria, offer structural simplicity, flexible tunability, and strong excitonic coupling through pigment–pigment interactions. However, these pigment aggregates suffer from limited absorption in the green and near-infrared regions and, similarly to other light-harvesting systems, reduced energy transfer efficiency at high donor concentrations. One promising strategy to overcome these limitations is the integration of plasmonic nanoparticles, which enhance local electromagnetic fields, increase spectral coverage, and make new energetic pathways accessible. Although plasmonic enhancement has been widely studied in pigment–protein complexes like Photosystem I and light-harvesting complexes (LHCs), its application to pigment-pigment self-assembled systems remains largely unexplored. This perspective presents recent advances in biomimetic light-harvesting design with chlorosome mimics and explores the potential for plasmonic enhancement of photophysics in these systems. We examine the structure of chlorosomes and their artificial mimics to understand the role of pigment-pigment interactions in facilitating highly efficient energy transfer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Designing efficient light-harvesting systems is crucial for the widespread, affordable, and safer practical use of solar radiation as a renewable energy source. The design parameters for these systems, such as near unity quantum efficiency, wide spectral coverage, cooperative energy transfer, and photoprotection, have been dictated by natural photosynthesis1,2,3,4,5. These principles have inspired biomimetic artificial light-harvesting antenna, which aim to improve energy transfer dynamics beyond those found in natural light-harvesting antennas6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14.

One natural system studied as an inspiration for self-assembling light-harvesting systems are chlorosomes found in green photosynthetic bacteria6,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. These chlorosomes, primarily made up of thousands of bacteriochlorophyll (BChl) c, d, or e, are able to sustain phototropic life under extreme low-light conditions4,16,23,24. Chlorosomes are also unique in that their structure self-assembles through pigment-pigment interactions, as opposed to being dictated by pigment-protein interactions4,25. This pigment self-assembly allows for facile preparation of artificial light-harvesting antenna, and additional pigments can be easily incorporated into the self-assembling structure26,27,28,29. Artificial chlorosome-like structures demonstrate efficient energy transfer and strong excitonic coupling resulting in superradiance6,15,16,30,31.

However, despite the efficient energy transfer between pigments in chlorosome-inspired artificial antennas, these systems have similar limitations as other light-harvesting complexes (LHCs). The efficiency of energy transfer decreases with an increasing concentration of pigments added to the bacteriochlorophyll structure due to limited packing space6. Additionally, these antennas exhibit low absorption in the green to yellow regions of the visible spectrum and in wavelengths above 900 nm, limiting their light-harvesting efficiency when compared to inorganic absorbers such as silicon4,6,16. Extending the absorption range and improving energy transfer efficiency would contribute towards optimizing artificial light-harvesting antennas to harness a maximal amount of sunlight.

One promising approach to addressing these limitations is the incorporation of plasmonically active nanomaterials into light-harvesting antennas32,33,34,35,36. Plasmonic behavior is a size-dependent phenomenon in which nanoparticles concentrate light to generate highly energetic charge carriers and form “hot spots” of local electromagnetic field enhancement37. The nanoparticle can act as an antenna and transfer energy to molecules confined near its surface38. Plasmonic confinement has the potential to enhance the energy transfer efficiency between pigments by making new energetic pathways accessible and extending the range of absorption wavelengths.

Most studies on plasmonically confined photosynthetic complexes have focused on systems whose structures are governed by pigment-protein interactions, such as Photosystem I (PSI) and various purified LHCs39,40,41,42,43. In contrast, the incorporation of plasmonic nanoparticles into self-assembling systems like artificial chlorosome mimics, which rely on pigment-pigment interactions, remains largely unexplored8.

In this perspective, we will first summarize progress in the development of bioinspired light-harvesting antennas, with a focus on design considerations in these systems. We will then examine chlorosomes and their mimics, investigating the role of pigment-pigment interactions in facilitating efficient energy transfer. Plasmonic enhancement will be introduced as an approach for addressing the shortcomings of these systems. Literature on the plasmonic enhancement of comparable light-harvesting systems will be presented to demonstrate the potential benefits of this approach. Then, we will evaluate strategies for integrating plasmonic nanoparticles into artificial chlorosome mimics. Finally, we will express our outlook on the promising future of plasmonically enhanced chlorosome mimics.

Main

Design considerations for artificial light-harvesting antennas based on natural pigments

In natural systems, the efficiency of photosynthesis strongly depends on regulation and adaptation to variable light conditions. High-light conditions necessitate dissipation of absorbed energy, since the downstream processes are what limits the rate of photosynthesis. Alternatively, low-light conditions demand that nearly all absorbed photons are utilized for photochemistry. Photosynthetic organisms in nature have met this requirement, achieving an over 90% quantum efficiency for energy transfer from light-harvesting antennas to reaction centers under optimal-light conditions25. For this reason, many studies devoted to increasing the efficiency of photosynthesis in vivo focus on improvements to the inefficient chemical reactions that follow, rather than light-harvesting itself 44,45,46,47,48.

For in vitro systems that take only the light-harvesting part of the photosynthetic apparatus and attach it to electrodes in either a solar or photochemical cell, it is possible to circumvent some of the limitations set by natural reaction centers1. Control over the speed of excitation conversion to separated electrons would allow high quantum efficiency to be maintained under illuminations of varying intensity. The limiting factor for such a system would then be the number of photons it can capture, although assessing the limits of artificial reaction centers comes with its own set of challenges. The obstacles faced when integrating natural light-harvesting antennas in biohybrid devices and their potential solutions have already been discussed and summarized in numerous reviews49,50,51,52.

This perspective focuses on the optimization of one component of biohybrid devices for solar energy capture: the antenna (Fig. 1). Biomimetic antennas hold great promise due to the near-unity quantum efficiencies found in nature, but there is room for improvement in terms of the spectral coverage of these systems. For example, natural light-harvesting antennas, with the exception of phycobilisomes, generally do not absorb much green light. While researchers provide proposed explanations for why most photosynthetic organisms do not absorb this abundant region of light53,54, in biohybrid devices, any part of the solar spectrum that is ignored yields lower overall efficiency. Another range of underutilized light is the red to infrared region, as most natural light-harvesting antennas do not use these wavelengths for photosynthesis.

The antenna must absorb as much of the solar spectrum as possible. A simple preparation procedure is desirable to lower production costs. The internal quantum efficiency of multicomponent systems hinges on efficient energy transfer between individual components. The bandgap of the lowest-energy component determines the energy efficiency. Long-term stability under working conditions is necessary. The antenna must be compatible with other parts of the device incorporating it. Preferably, nontoxic components or processes are used for preparation.

Concerted efforts to extend the absorption range of light-harvesting antennas have focused on designing proteins to tune spectral gaps of pigments or bind modified absorbers55,56. Some approaches to constructing artificial light-harvesting systems, such as those based on dendrimers of dyes, organic nanocrystals, or non-covalent assemblies, have been also been studied11,12,57,58,59. Others have focused on incorporating natural pigments with unique optical properties, such as chlorophyll (Chl) f. Prior to the discovery of Chl f in 201060, it was believed that only anoxygenic photosynthesis could utilize wavelengths of light beyond 680 nm, as oxygenic photosynthesis was considered to be limited by the high redox potential necessary to split water. Far-red-light-adapted organisms with antennas containing Chl f suggested otherwise, demonstrating that longer wavelengths of light could be utilized in oxygenic photosynthesis60,61,62. Incorporating Chl f in modified photosynthetic antennas broadened their absorption range, demonstrating potential for applications in photoelectrochemical cells for hydrogen or fuel production from photocatalytic water splitting63. However, these systems showed poor overall stability and efficiency, limiting their practical use64.

To improve stability and ease of practical application, other efforts to modify light-harvesting antennas have explored self-assembling systems. In 2022, Hancock et al.65 studied self-assembled liposomes with a combination of natural complexes and synthetic dyes. Energy transfer was demonstrated between components without covalent binding or other modifications of said natural complexes. Lipophilic dyes and lipid-bound hydrophilic dyes were used to sensitize LHCII from plants and LH2 from bacteria, and an 80% boost in fluorescence from the acceptor was recorded. In 2025, they followed up with increased generation of photocurrent directly from sensitized LHCII in an identical system66. This shows potential for utilization of such artificial self-assembling membranes in light-harvesting.

Other studies have focused on the design of self-assembled light-harvesting antennas themselves. Chlorosomes, antennas of green bacteria that are mostly composed of pigments, are an inspiration for a whole other class of self-assembled absorbers (Fig. 2a). Bacteriochlorophylls isolated from these antennas have shown the ability to self-assemble in vitro into units that are functionally very similar to chlorosomes themselves. Modifications of these artificially self-assembled antennas have been studied with the intent to develop an antenna with an extended absorption spectrum6,19,28,29,67,68,69.

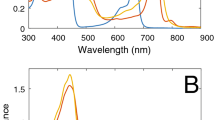

a The diagram illustrates the shape and interior structure of a typical chlorosome. The lamellar layers (shown in green) consist of aggregates of bacteriochlorophyll (BChl). These layers are held together by hydrophobic interactions between the interdigitated esterifying alcohols of the BChls, which create a hydrophobic space (depicted in orange) between the chlorin layers. This space is also occupied by carotenoids and quinones. At the base of the chlorosome, the baseplate is represented as being composed of CsmA protein dimers, each containing one BChl a molecule (represented as a blue-green rectangle). The orange background of the baseplate indicates the presence of carotenoids within it. The envelope is primarily made up of proteins (illustrated as gray particles), while lipids fill the space between the proteins (shown in cyan). Reprinted from reference 17, © 2014, with permission from Springer Nature. b An absorbance spectrum of artificial chlorosome mimics, which are pigment aggregates made up of BChl a, BChl c, and β-carotene. Arrows indicate the flow of electronic energy transfer and relaxation within the aggregates. c A conceptual energy level diagram illustrating the flow of energy transfer in artificial chlorosome mimic pigment aggregates.

Chemically modified bacteriochlorophylls have been used to prepare artificial chlorosome-like antennas with optimized spectral properties. Selective substitution of functional groups of the chlorin ring was shown to tune absorption properties of individual pigments67,70, partially covering the green gap or red-shifting absorption71. In other studies, co-assemblies of natural bacteriochlorophylls with other pigments have been demonstrated19,26,27,28,29,68,69. Recently, efficiency of energy transfer between components in a three-pigment self-assembled antenna was determined (Fig. 2b, c)6.

While self-assembling multi-component light-harvesting antennas provide, in theory, a relatively simple solution to the search for a panchromatic photosynthetic absorber, it is important to consider the efficiency of energy transfer between individual components. Although many dyes can transfer excitation energy to photosynthetic complexes, they do not all exhibit optimal efficiency. In the previously mentioned case of liposomes65, the efficiency of energy transfer to LHCII ranged between 25 and 97% depending on the dye and concentration, and the efficiency of energy transfer to LH2 ranged between 53 and 91%. The recorded 97% efficiency corresponded to energy transfer from Texas Red to LHCII, but the efficiency was significantly lowered with increasing the donor concentration.

Similar conclusions were found for chlorosome mimics. One study loaded a bacteriochlorophyll structure with carotenoids, which transferred almost 90% of excitations at low carotenoid content, but efficiency dropped with higher donor concentration6. Thus, for practical applications, the efficiency of energy transfer, light-harvesting, or both must be improved in order for multi-component systems to be used as absorbers.

Structure-function relationship within natural and artificial bacteriochlorophyll aggregates

Chlorosomes and their artificial mimics have great potential in solar energy harnessing due to their high number of pigments, efficient energy transfer, and simple preparation procedures. Although the pigments in these systems can harvest light fairly well on their own, it is only upon aggregation that exciton delocalization occurs4,16,17, which contributes to a high excitation energy transfer efficiency despite the large size of these systems72,73. Therefore, a robust understanding of the role of pigment-pigment interactions in these systems is needed to guide rational design for the incorporation of plasmonic nanoparticles into chlorosomes.

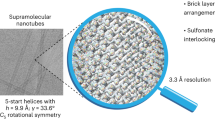

The large size of the chlorosome and the high degree of heterogeneity and disorder4,16,17 make pigment organization in each chlorosome unique, preventing structure determination by X-ray crystallography or single particle averaging. X-ray scattering and cryo-EM studies have revealed repeating layers of pigments exhibiting lamellar organization74. This layered arrangement has since been confirmed by many other studies75,76,77,78,79,80,81.

The formation of layers is enabled by the structure of chlorosomal BChls76. Individual BChls are bound together by π-π interactions, with bonds between the central metal ion and the alcohol and keto groups leading to the formation of 2D layers82. These layers are held together by van der Waals interactions between the esterifying alcohols of BChls. The same bonding structure is found within artificial chlorosome mimics, suggesting that the layered nature of aggregates is embedded within the structure of the BChl molecules themselves83. The aggregates adopt various structures, from the disordered curved lamellae found in most of the native chlorosomes to the cylinders found in specific mutants with a simplified composition75,81,84,85,86,87.

The strong interactions between pigments in both natural and artificial chlorosomes yield several distinct effects when compared to individual pigments. Excitonic interactions give rise to red-shifted and broadened absorption bands when compared to those of monomeric pigments. Strong coupling between BChls results in exciton delocalization, which can extend over many pigments15,16,88,89. In fact, the excitation interactions between pigments are so strong that they maintain some extent of delocalization even after exciton relaxation, causing aggregates to exhibit superradiance15. These strong pigment-pigment interactions also give rise to structural domains separated by inhomogeneities or structural variations where pigments interact more strongly90,91, which may allow for Förster hopping between these domains and increase the efficiency of energy transfer by limiting the number of hopping steps72,73,91,92,93.

Towards the development of artificial aggregates, chlorosomal bacteriochlorophylls have been found to aggregate both in non-polar solvents and in aqueous environments. Aggregation in aqueous solvents is driven by interaction between the non-polar esterifying alcohols, and addition of a suitable non-polar molecule is required to induce the aggregation19,68,69. Aggregation in non-polar solvents is driven by interactions between the polar chlorin rings94. This ability to self-assemble under various conditions adds versatility to preparing co-assemblies of plasmonic nanoparticles with chlorosome mimics. The hydrogen and coordination bonds within bacteriochlorophyll aggregates indicate that attaching them to functionalized nanoparticles is possible, which has been confirmed experimentally by growing BChl aggregates on gold surfaces functionalized with hydroxyl groups8.

Their self-assembly, the ability to incorporate other pigments into their structure, and the potential for their attachment to functionalized surfaces of plasmonic nanoparticles make chlorosome mimics promising candidates for plasmonically enhanced light-harvesting antennas. The gaps in chlorosomes’ absorption spectra between 500–700 nm and above 900 nm are one downside of these systems that the incorporation of plasmonic nanoparticles would improve. This, along with other ways that plasmonic confinement can enhance the photophysics of chlorosomes, will be discussed in the following sections.

Plasmonic nanoantennas as “super” sensitizers to enhance light-harvesting antennas

Recently, plasmonic nanoantennas have been applied to extend the absorption range and enhance the photophysics of light-harvesting systems. Plasmonic nanoparticles offer the advantages of extended spectral coverage34,95, enhanced light-harvesting abilities in nearby molecules96, and easily tunable optical properties97,98,99. In this section, we will discuss how plasmonic nanoparticles can act as “super” sensitizers and enhance the photophysics of light-harvesting antennas. For literature focused on comprehensive analyses of related topics, readers are referred to reviews on plasmonic behavior37, plasmonic photochemistry100,101,102, and surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS)103.

A surface plasmon is defined as a collective oscillation of delocalized electrons that is induced by irradiation with light37,104. There are two types of surface plasmons: the surface plasmon polariton (SPP) (Fig. 3a) and the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) (Fig. 3b)37. SPPs are traveling electromagnetic waves that propagate across a thin metal surface, while LSPRs are localized to a nanoparticle.

Schematics showing the transformative potential of plasmonic materials, where in a, we see a compelling illustration of the surface plasmon polariton, while part b showcases localized surface plasmon resonance, both of which are foundational concepts in this field. Part c offers a critical summary of the key absorption spectral ranges of various plasmonic metals, highlighting their potential in harnessing the expansive solar spectrum through diverse shapes and sizes of metal nanoparticles. Reprinted with permission from ref. 117, Copyright © 2024 by the American Chemical Society. In part d, a schematic comparison of the optical and physical properties of noble and non-precious plasmonic metal nanoparticles reveals significant differences that drive innovation in material design. Reprinted with permission from ref. 117, Copyright © 2024 by the American Chemical Society. Part e presents a dynamic schematic that captures the timescale of plasmon excitation and its time-resolved progression, providing a clearer understanding of these rapid processes. This illustration is reprinted with permission from ref. 37, Copyright © 2024 by AIP Publishing. Finally, part f introduces the concept of "hot spots," showcasing the remarkable electromagnetic field enhancement occurring at the junction between two plasmonic nanoparticles. All mechanisms underscore the intricate interactions at play in plasmonics for light-harvesting.

For plasmonic applications in biomimetic light-harvesting systems, we have chosen to focus on the LSPR. One reason it is desirable to work with the LSPR is because plasmonic nanoparticles offer the advantage of great flexibility. The LSPR frequency can easily be tuned by adjusting the nanoparticle shape, size, or material, which allows for precise control when integrating into complex light-harvesting systems (Fig. 3c, d)105,106,107. Another reason for working with the LSPR is that LSPR excitation and decay present several opportunities for charge and energy transfer that can enhance the photophysics of nearby molecules37,38. During LSPR decay, highly energetic charge carriers are generated that can transfer to nearby molecules or recombine, resulting in thermal dissipation (Fig. 3e)37. LSPR excitation concentrates light to “hot spots” of localized electromagnetic field enhancement, the strength of which can be described by the electromagnetic enhancement factor L(ν) relating the amplitude of the local field |ELoc| with that of the incident electromagnetic field |E0|(Eq. (1))108,109,110

This enhancement comes from two main contributions: a wavelength-dependent component from the resonant excitation of localized surface plasmons in metallic nanostructures (LSP(ν)) and a geometric component called the “lightning rod effect” (LLR) (Eq. (2))108,110,111

This “lightning rod effect” refers to the crowding of electric field lines at the junctions between nanoparticles and sharp geometric features, which explains why those regions experience the most intense electromagnetic enhancement (Fig. 3f)111. The LSP(ν) is directly proportional to the g factor derived through Mie Theory (Eq. (3)) that relates the dielectric function of the plasmonic nanoparticle (ε(ω)) and the dielectric constant of the surrounding medium (εm)37,104,108,112. Maximal electromagnetic field enhancement is achieved when the g factor is maximized by meeting the Frölich condition for plasmonic behavior (Eq. (4))112

“Hot spots” of this electromagnetic field enhancement exhibit changes in polarizability and shifts in the adsorbate molecular orbital overlap with the density of states in the plasmonic metal37,108,112. This is notable because it can modify fluorescence109,113,114,115, absorption116, and scattering processes109,110 in plasmonically confined molecules.

The effects of plasmons on nearby molecules, from both electromagnetic hot spots and highly energetic charge carriers, enable plasmonic nanoantennas to be thought of as “super” sensitizers. Not only do plasmonic nanoparticles act as conventional photosensitizers by extending the absorption range of a system, but they also make new energetic pathways accessible for nearby, plasmonically confined, molecules37,38,117.

Research into this aspect of plasmonics is relatively young. Although plasmonic behavior has been studied since the 1970s118,119,120,121, initial research on plasmonics was limited to applications in spectroscopy and imaging. This changed in 2010, with the first report of a plasmon-driven chemical transformation122. In this work, Huang et al. observed the oxidation of para-aminothiophenol to form 4,4′-dimercaptoazobenzene during SERS measurements on a silver plasmonic substrate122. This discovery ushered in a new era for the field of plasmonics, extending research into applications in surface catalysis and light-harvesting systems.

Effects of plasmonic enhancement in photosynthetic complexes

Plasmonic confinement of natural photosynthetic complexes has been shown to offer several benefits, such as extended absorption ranges123, enhanced energy transfer and absorption114,124, and increased photostability114,125. The plasmonic nanoparticles used in these systems are most commonly either silver or gold, since silver offers strong electromagnetic field enhancement and gold offers great stability37. Natural photosynthetic complexes that have been studied under plasmonic confinement include Photosystem I (PSI)126, Photosystem II (PSII)127, light-harvesting complex II (LHCII)128, light-harvesting complex 1 (LH1)123, light-harvesting complex 2 (LH2)114, and peridinin−chlorophyll−protein (PCP)129. Plasmonic confinement of chlorosomes or their artificial mimics has not yet been studied, but examining the impacts of plasmonic enhancement on other natural photosynthetic systems enables the development of a hypothesis for how plasmonic confinement could benefit chlorosomes and their artificial mimics.

Plasmonic nanoparticles can extend the absorption range of light-harvesting systems through rational design of the optical overlap between the nanoparticle and the photosynthetic complex. For example, the limited absorption capability of both LH1 and LH2 between ~600 and 800 nm can be compensated for by incorporating gold nanoparticles that have an LSPR frequency in this region and strongly absorb this light (Fig. 4)123. Chlorosomes and their mimics similarly have limited absorption in the 500–700 nm region, so the incorporation of gold nanoparticles could be used to achieve a more robust absorption spectrum in plasmon-chlorosome hybrid systems.

Extinction spectra for gold nanostructured periodic arrays before (blue) and after (red) attachment of a the Δcrtl::crtlPa ΔcrtC mutant of LH2 and b the ΔcrtC mutant of LH1. Arrows indicate new peaks formed from the energetic splitting of the LSPR. The absorption spectra of solvated proteins are shown in green. Reprinted with permission from ref. 123, Copyright © 2024 American Chemical Society.

To examine enhanced energy transfer and absorption, many studies on plasmonically confined natural photosynthetic complexes focus on fluorescence spectroscopy and maximizing fluorescence signal intensity32,34,35,100,126. Plasmonic confinement of fluorophores can result in either fluorescence quenching or enhancement, depending on factors such as optical overlap and the distance between the nanoparticle and fluorophore molecule (Fig. 5)130. Fluorescence enhancement is understood to occur by enhancing the molecule’s absorbance or by increasing the radiative rate of the plasmonically confined species114. Absorption enhancement depends on the degree of overlap between the LSPR scattering spectrum and the chromophore’s absorption spectrum, while the increased radiative rate depends on strong plasmonic enhancement of the local electromagnetic field130. Increased fluorescence signals can also signify increased energy transfer between chromophores in multi-component systems, which is desirable for optimal light-harvesting124. It can be challenging to deconvolute the factors contributing to fluorescence enhancement and quenching, but studying changes in fluorescence does have great potential to reveal information about the photophysics of plasmonically confined light-harvesting systems.

Fluorescence quenching is experienced by fluorophores near the nanoparticle surface due to strong energy losses involving the scattering of electrons in the metal. The enhancement of the electric field (E-field) through localized surface plasmons (LSPs) on plasmonic nanoparticles leads to increased absorption and/or radiative rate for adsorbed fluorophores, extending up to several tens of nanometers (approximately 30 nm, as shown here). Nanosurface energy transfer (NSET) occurs between the transition dipole moment of the fluorophore emission and the LSPs on the nanoparticle, resulting in a distance-dependent enhancement or quenching of the signal. Typically, both NSET and E-field enhancement happen concurrently, resulting in a combination of quenching and enhancement, referred to as "quenchancement." Reprinted from ref. 130 with permission from The Royal Society of Chemistry.

Plasmonic confinement has been shown to enhance the absorption of natural photosynthetic complexes, resulting in considerable fluorescence enhancement. Czechowski et al. reported a fluorescence enhancement factor of ~200 for PSI when placed under the plasmonic confinement of silver nanoparticles124. Since fluorescence lifetimes were not changed by plasmonic confinement, the signal enhancement was attributed to plasmonic activation of new excitation and emission channels in PSI124. For LH2, an over 500-fold plasmonic fluorescence enhancement has been observed at the single-molecule level, which was partially attributed to excitation enhancement from the LSPR114. Since enhanced photon absorption and newly accessible energetic pathways are common in other plasmonically confined light-harvesting systems, it is reasonable to hypothesize that this may occur in plasmonically confined chlorosomes as well.

Plasmonic confinement can also increase the photostability of light-harvesting systems. The plasmonically enhanced local electromagnetic field can cause radiative rate enhancement, which improves photostability by minimizing the amount of time that the plasmonically confined species exist in an excited state, allowing for an increased number of photons to be emitted before any photodamage occurs114. Additionally, interaction with the plasmonic nanoparticle can protect chromophores from degradation, which is shown in the example of gold nanoparticles preventing the degradation of Chl a from reactive oxygen species by binding with the pigments at nitrogen sites125. For chlorosomes, some photoprotection is already provided by the carotenoids and quinones in the structure and the excitonic interactions between aggregated pigments, but further stability provided by plasmonic nanoparticles would be beneficial.

Design strategies for the integration of plasmonic nanoparticles into artificial chlorosome mimics

Despite the promising effects observed in plasmonically enhanced natural photosynthetic pigment-protein complexes, there is a lack of research on plasmonic confinement of chlorosome structures or their artificial mimics. Given that plasmonic enhancement is highly dependent on the location of confined molecules relative to plasmonic nanoparticles and their “hot spots,” it is important to discuss strategies for integrating nanoparticles into chlorosome-like structures to obtain maximal plasmonic enhancement.

The first design consideration for these systems is the selection of plasmonic nanoparticles. Plasmonic nanoparticles can vary in their size, shape, and composition, which all influence the LSPR frequency and the electromagnetic field enhancement105,106,107. Although recent reviews have focused on silver plasmonic systems due to their strong plasmonic activity131, we advocate for the use of gold nanoparticles due to their superior stability that simplifies sample handling and spectroscopic characterization. Additionally, gold nanoparticles offer a high degree of functional versatility. They can be readily modified with various ligands such as citrate132, cetyltrimethylammonium bromide133, or thiol-containing compounds8, which enable diverse attachment strategies to tune interactions with chlorosome mimics. Gold nanoparticles have been synthesized in a variety of morphologies, including spheres134,135, rods133,136, cubes98,137,138, and stars139,140, which offers additional flexibility in design.

Particle shape is an important factor affecting plasmon-molecule interactions, due to the previously discussed geometric dependence of electromagnetic field enhancement108. Maximizing the number of “hot spots” accessible to chlorosomal pigments requires a nanoparticle shape with several sharp geometric features, since these yield the highest electromagnetic field enhancement. Shapes such as nanostars or nanorods are promising, not only because of the number of hot spots per particle, but also because their anisotropy supports multiple LSPR frequencies, enabling use of a wider range of wavelengths.

Size is another important parameter, as larger particles exhibit red-shifted LSPR frequencies and smaller particles exhibit blue-shifted LSPR frequencies105. Tuning the nanoparticle size is a simple way to control the optical overlap between the nanoparticle’s LSPR and the absorption of the chlorosomal pigments. Gaps in the absorption spectrum of artificial chlorosome mimics, particularly in the 500–700 nm and >900 nm regions, can be compensated for with nanoparticles that absorb those wavelengths. Alternatively, nanoparticles can be designed to have an LSPR that matches specific pigment absorption features, such as that of BChl c, to enhance energy transfer processes toward BChl a. Together, these design options offer multiple viable approaches for optimizing plasmon-molecule interactions, enabling efficient broadband light-harvesting.

Beyond nanoparticle selection, a crucial design consideration is the method used to place chlorosomal pigments under plasmonic confinement. There are two main strategies for this: immobilization on solid-phase plasmonic substrates (Fig. 6a)141,142 or solution-phase nanoparticle aggregation (Fig. 6b)132. In the first approach, solid-phase plasmonic substrates, such as nanoarrays of functionalized nanoparticles, would be fabricated via lithography, and previously prepared chlorosome mimics would be deposited on their surfaces141,142. However, since chlorosome mimics are quite large, attachment in this manner would place only a small fraction of the pigments within the “hot spot” regions of the plasmonic substrate, leaving the majority of pigments unaffected (Fig. 6c).

Schematic showing plasmonic confinement of small molecules via a a solid-phase plasmonic substrate and b solution-phase nanoparticle aggregation. Since artificial chlorosome mimics are quite large compared to the size of plasmonic nanoparticles, the number of pigments placed under plasmonic confinement is limited for c solid-phase plasmonic substrate compared to d when nanoparticles are embedded within the chlorosome mimics via simultaneous pigment and nanoparticle aggregation.

To maximize the amount of chlorosomal pigments placed under plasmonic confinement, incorporating nanoparticles within the structure is a promising approach (Fig. 6d). This could be achieved using the solution-phase nanoparticle aggregation method. In this approach, colloidal nanoparticles are dispersed in solution, and pigment molecules are introduced to destabilize the dispersion, triggering nanoparticle aggregation132. The nanoparticles form dimers, trimers, and larger oligomers with “hot spots” at each nanoparticle junction. If needed, excessive aggregation and precipitation can be prevented by adding a polymer that will form a shell around the oligomers, stopping the aggregation process132. If chlorosomal pigments were added to a colloidal nanoparticle dispersion, the simultaneous formation of pigment aggregates and nanoparticle aggregates could occur. Electrostatic attractions or hydrogen bonding between the pigments and the functionalized nanoparticle surface could cause the nanoparticles to form aggregates within the chlorosome structure. Embedding the plasmonic aggregates within the larger chlorosome structure would allow for plasmonic confinement of a larger portion of the chlorosomal pigments, amplifying plasmonic enhancement effects. The structural disruption caused by the presence of the nanoparticles themselves could also alter the excited-state dynamics, independent of plasmonic enhancement effects. Such a phenomenon was recently observed6 when additional pigments were added into the structure of bacteriochlorophyll aggregates and an increase in total fluorescence was observed. However, the effects of plasmonic nanoparticles in these circumstances are still largely unexplored.

Outlook

In conclusion, this perspective emphasizes the untapped potential of plasmonic enhancement in self-assembling artificial light-harvesting systems. We have summarized the design considerations that guided previous development of nature-inspired light-harvesting systems, highlighting why chlorosomes are particularly promising as a source of inspiration for artificial light-harvesting systems. We examined the effects of plasmonic confinement on light-harvesting systems, considering the potential benefits this could have on chlorosomes and their mimics. We assert that the plasmonic confinement of artificial chlorosomes is worth investigating. Self-assembling chlorosome mimics offer the advantages of simple fabrication and efficient energy transfer, and high photostability. We believe that there is potential for exciting future work in the design and optimization of plasmon-chlorosome systems, as the synergy between the light-absorbing abilities of plasmonic nanoparticles and the enhanced photophysics and photostability of plasmonically confined molecules holds promise for the development of light-harvesting systems with unprecedented light-harvesting efficiency.

References

Dogutan, D. K. & Nocera, D. G. Artificial photosynthesis at efficiencies greatly exceeding that of natural photosynthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 52, 3143–3148 (2019).

Yang, S.-J., Wales, D. J., Woods, E. J. & Fleming, G. R. Design principles for energy transfer in the photosystem II supercomplex from kinetic transition networks. Nat. Commun. 15, 8763 (2024).

Wang, D. et al. Elucidating interprotein energy transfer dynamics within the antenna network from purple bacteria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 120, e2220477120 (2023).

Orf, G. S. & Blankenship, R. E. Chlorosome antenna complexes from green photosynthetic bacteria. Photosynth. Res. 116, 315–331 (2013).

Fleming, G. R., Schlau-Cohen, G. S., Amarnath, K. & Zaks, J. Design principles of photosynthetic light-harvesting. Faraday Discuss. 155, 27–41 (2012).

Malina, T., Bína, D., Collins, A. M., Alster, J. & Pšenčík, J. Efficient two-step excitation energy transfer in artificial light-harvesting antenna based on bacteriochlorophyll aggregates. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 254, 112891 (2024).

Löhner, A. et al. Spectral and structural variations of biomimetic light-harvesting nanotubes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10, 2715–2724 (2019).

Furumaki, S., Vacha, F., Hirata, S. & Vacha, M. Bacteriochlorophyll aggregates self-assembled on functionalized gold nanorod cores as mimics of photosynthetic chlorosomal antennae: a single molecule study. ACS Nano 8, 2176–2182 (2014).

Xin, X., Tang, X., Guan, W. & Lu, C. Design of aggregation-induced emissive multiwalled tubules for efficiently sequential light harvesting. Adv. Opt. Mater. 12, 2401434 (2024).

Matsubara, S., Shoji, S. & Tamiaki, H. Biomimetic light-harvesting antennas via the self-assembly of chemically programmed chlorophylls. Chem. Commun. 60, 12513–12524 (2024).

Chen, P.-Z. et al. Light-harvesting systems based on organic nanocrystals to mimic chlorosomes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 2759–2763 (2016).

Zhang, D. et al. Hierarchical self-assembly of a dandelion-like supramolecular polymer into nanotubes for use as highly efficient aqueous light-harvesting systems. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 7652–7661 (2016).

Ogi, S., Grzeszkiewicz, C. & Würthner, F. Pathway complexity in the self-assembly of a zinc chlorin model system of natural bacteriochlorophyll J-aggregates. Chem. Sci. 9, 2768–2773 (2018).

Matsubara, S. & Tamiaki, H. Supramolecular Chlorophyll aggregates inspired from specific light-harvesting antenna “Chlorosome”: static nanostructure, dynamic construction process, and versatile application. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 45, 100385 (2020).

Malina, T., Koehorst, R., Bína, D., Pšenčík, J. & van Amerongen, H. Superradiance of Bacteriochlorophyll c aggregates in chlorosomes of green photosynthetic bacteria. Sci. Rep. 11, 8354 (2021).

Oostergetel, G. T., van Amerongen, H. & Boekema, E. J. The chlorosome: a prototype for efficient light harvesting in photosynthesis. Photosynth. Res. 104, 245–255 (2010).

Pšenčík, J.; Butcher, S. J.; Tuma, R. Chlorosomes: Structure, Function and Assembly. in The Structural Basis of Biological Energy Generation (ed Hohmann-Marriott, M. F.) 77–109 (Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2014).

Brune, D. C., Nozawa, T. & Blankenship, R. E. Antenna Organization in green photosynthetic bacteria. 1. Oligomeric Bacteriochlorophyll c as a model for the 740 Nm absorbing Bacteriochlorophyll c in Chloroflexus Aurantiacus chlorosomes. Biochemistry 26, 8644–8652 (1987).

Collins, A. M., Timlin, J. A., Anthony, S. M. & Montaño, G. A. Amphiphilic block copolymers as flexible membrane materials generating structural and functional mimics of green bacterial antenna complexes. Nanoscale 8, 15056–15063 (2016).

Hirota, M. et al. High degree of organization of Bacteriochlorophyll c in Chlorosome-like aggregates spontaneously assembled in aqueous solution. Biochim.Biophys. Acta (BBA) Bioenerg. 1099, 271–274 (1992).

Smith, K. M., Kehres, L. A. & Fajer, J. Aggregation of the Bacteriochlorophylls c, d, and e. Models for the antenna chlorophylls of green and brown photosynthetic bacteria. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 105, 1387–1389 (1983).

Miyatake, T., Tamiaki, H., Holzwarth, A. R. & Schaffner, K. Self-assembly of synthetic zinc chlorins in aqueous microheterogeneous media to an artificial supramolecular light-harvesting device. Helvetica Chim. Acta 82, 797–810 (1999).

Overmann, J., Cypionka, H. & Pfennig, N. An extremely low-light adapted phototrophic sulfur bacterium from the Black Sea. Limnol. Oceanogr. 37, 150–155 (1992).

Beatty, J. T. et al. An obligately photosynthetic bacterial anaerobe from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 9306–9310 (2005).

Blankenship, R. E. Molecular Mechanisms of Photosynthesis (Wiley, 2008).

Alster, J. et al. β-Carotene to Bacteriochlorophyll c energy transfer in self-assembled aggregates mimicking chlorosomes. Chem. Phys. 373, 90–97 (2010).

Miyatake, T. & Tamiaki, H. Self-aggregates of natural chlorophylls and their synthetic analogues in aqueous media for making light-harvesting systems. Coord. Chem. Rev. 254, 2593–2602 (2010).

Matěnová, M. et al. Energy transfer in aggregates of bacteriochlorophyll c self-assembled with azulene derivatives. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 16755–16764 (2014).

Alster, J. et al. Self-assembly and energy transfer in artificial light-harvesting complexes of bacteriochlorophyll c with Astaxanthin. Photosynth. Res. 111, 193–204 (2012).

Zietz, B., Prokhorenko, V. I., Holzwarth, A. R. & Gillbro, T. Comparative study of the energy transfer kinetics in artificial BChl e aggregates containing a BChl a acceptor and BChl E-containing chlorosomes of Chlorobium phaeobacteroides. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 1388–1393 (2006).

Prokhorenko, V. I., Holzwarth, A. R., Nowak, F. R. & Aartsma, T. J. Growing-in of optical coherence in the FMO antenna complexes. J. Phys. Chem. B 106, 9923–9933 (2002).

Caprasecca, S., Guido, C. A. & Mennucci, B. Control Of coherences and optical responses of pigment–protein complexes by plasmonic nanoantennae. J. Phys. Chem. Lett.7, 2189–2196 (2016).

Andreussi, O., Biancardi, A., Corni, S. & Mennucci, B. Plasmon-controlled light-harvesting: design rules for biohybrid devices via multiscale modeling. Nano Lett. 13, 4475–4484 (2013).

Beyer, S. R. et al. Hybrid nanostructures for enhanced light-harvesting: plasmon induced increase in fluorescence from individual photosynthetic pigment–protein complexes. Nano Lett. 11, 4897–4901 (2011).

Carmeli, I. et al. Broad band enhancement of light absorption in photosystem i by metal nanoparticle antennas. Nano Lett. 10, 2069–2074 (2010).

Adhyaksa, G. W. P. et al. A light harvesting antenna using natural extract graminoids coupled with plasmonic metal nanoparticles for bio-photovoltaic cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 4, 1400470 (2014).

Warren, N. L., Yunusa, U., Singhal, A. B. & Sprague-Klein, E. A. Facilitating excited-state plasmonics and photochemical reaction dynamics. Chem. Phys. Rev. 5, 011307 (2024).

Carlin, C. C. et al. Nanoscale and ultrafast in situ techniques to probe plasmon photocatalysis. Chem. Phys. Rev. 4. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0163354 (2023).

Szalkowski, M. et al. Plasmon-induced absorption of blind chlorophylls in photosynthetic proteins assembled on silver nanowires. Nanoscale 9, 10475–10486 (2017).

den Hollander, M.-J. et al. Enhanced photocurrent generation by photosynthetic bacterial reaction centers through molecular relays, light-harvesting complexes, and direct protein–gold interactions. Langmuir 27, 10282–10294 (2011).

Pamu, R., Sandireddy, V. P., Kalyanaraman, R., Khomami, B. & Mukherjee, D. Plasmon-enhanced photocurrent from photosystem I assembled on Ag nanopyramids. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9, 970–977 (2018).

Furuya, R., Omagari, S., Tan, Q., Lokstein, H. & Vacha, M. Enhancement of the photocurrent of a single photosystem I complex by the localized plasmon of a gold nanorod. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 13167–13174 (2021).

Govorov, A. O. & Carmeli, I. Hybrid structures composed of photosynthetic system and metal nanoparticles: plasmon enhancement effect. Nano Lett. 7, 620–625 (2007).

Evans, J. R. Improving photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 162, 1780–1793 (2013).

Blankenship, R. E. & Chen, M. Spectral expansion and antenna reduction can enhance photosynthesis for energy production. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 17, 457–461 (2013).

Matsumura, H. et al. Hybrid Rubisco with complete replacement of rice Rubisco small subunits by sorghum counterparts confers C4 plant-like high catalytic activity. Mol. Plant 13, 1570–1581 (2020).

Tanvir, R. U. et al. Harnessing solar energy using phototrophic microorganisms: a sustainable pathway to bioenergy, biomaterials, and environmental solutions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 146, 111181 (2021).

Gionfriddo, M., Rhodes, T. & Whitney, S. M. Perspectives on improving crop Rubisco by directed evolution. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 155, 37–47 (2024).

Teodor, A. H. & Bruce, B. D. Putting photosystem I to work: truly green energy. Trends Biotechnol. 38, 1329–1342 (2020).

Villarreal, C. C. et al. Bio-sensitized solar cells built from renewable carbon sources. Mater. Today Energy 23, 100910 (2022).

Voloshin, R. A. et al. Photosystem II in bio-photovoltaic devices. Photosynthesis 60, 121–135 (2022).

Voloshin, R. A., Lokteva, E. S. & Allakhverdiev, S. I. Photosystem I in the biohybrid electrodes. Curr. Opin. Green. Sustain. Chem. 41, 100816 (2023).

Arsenault, E. A., Yoneda, Y., Iwai, M., Niyogi, K. K. & Fleming, G. R. The role of mixed vibronic Qy-Qx states in green light absorption of light-harvesting complex II. Nat. Commun. 11, 6011 (2020).

Terashima, I., Fujita, T., Inoue, T., Chow, W. S. & Oguchi, R. Green light drives leaf photosynthesis more efficiently than red light in strong white light: revisiting the enigmatic question of why leaves are green. Plant Cell Physiol. 50, 684–697 (2009).

Cohen-Ofri, I. et al. Zinc-bacteriochlorophyllide dimers in de novo designed four-helix bundle proteins. A model system for natural light energy harvesting and dissipation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 9526–9535 (2011).

Lahav, Y., Noy, D. & Schapiro, I. Spectral tuning of chlorophylls in proteins – electrostatics vs. ring deformation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 23, 6544–6551 (2021).

Rogati, G. M. A. et al. Molecular modelling and simulations of light-harvesting decanuclear Ru-based dendrimers for artificial photosynthesis. Chem. A Eur. J. 28, e202103310 (2022).

Chen, X.-M. et al. Self-assembled supramolecular artificial light-harvesting nanosystems: construction, modulation, and applications. Nanoscale Adv. 5, 1830–1852 (2023).

Chen, H. et al. A visible-light-harvesting covalent organic framework bearing single nickel sites as a highly efficient sulfur–carbon cross-coupling dual catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 10820–10827 (2021).

Chen, M. et al. A red-shifted chlorophyll. Science 329, 1318–1319 (2010).

Judd, M. et al. The primary donor of far-red photosystem II: ChlD1 or PD2?. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Bioenerg. 1861, 148248 (2020).

Nürnberg, D. J. et al. Photochemistry beyond the red limit in chlorophyll f–containing photosystems. Science 360, 1210–1213 (2018).

Hernández-Prieto, M. A., Hiller, R. & Chen, M. Chlorophyll f can replace chlorophyll a in the soluble antenna of dinoflagellates. Photosynth Res 152, 13–22 (2022).

Viola, S. et al. Impact of energy limitations on function and resilience in long-wavelength photosystem II. eLife 11, e79890 (2022).

Hancock, A. M. et al. Enhancing the spectral range of plant and bacterial light-harvesting pigment-protein complexes with various synthetic chromophores incorporated into lipid vesicles. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 237, 112585 (2022).

Kondo, M.; Hancock, A. M.; Kuwabara, H.; Adams, P. G.; Dewa, T. Photocurrent generation by plant light-harvesting complexes is enhanced by lipid-linked chromophores in a self-assembled lipid membrane. J. Phys. Chem. B acs.jpcb.4c07402. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcb.4c07402 (2025).

Matsubara, S. & Tamiaki, H. Synthesis and self-aggregation of π-expanded chlorophyll derivatives to construct light-harvesting antenna models. J. Org. Chem. 83, 4355–4364 (2018).

Klinger, P. & Arellano, J. B. Effect of carotenoids and monogalactosyl diglyceride on bacteriochlorophyll c aggregates in aqueous buffer: implications for the self-assembly of chlorosomes. Photochem. Photobiol. 80, 572–578 (2004).

Orf, G. S. et al. Polymer–chlorosome nanocomposites consisting of non-native combinations of self-assembling bacteriochlorophylls. Langmuir 33, 6427–6438 (2017).

Nishibori, S., Hara, N. & Tamiaki, H. Effect of perfluorination at the 3-ethyl group in chlorophyll-a derivatives on physical properties in solution. J. Fluor. Chem. 274, 110261 (2024).

Tamiaki, H., Kuno, M. & Kunieda, M. Self-aggregation of a synthetic zinc chlorophyll derivative possessing a 131-dicyanomethylene group as a light-harvesting antenna model. Tetrahedron Lett. 55, 2825–2828 (2014).

Yakovlev, A., Novoderezhkin, V., Taisova, A. & Fetisova, Z. Exciton dynamics in the chlorosomal antenna of the green bacterium Chloroflexus aurantiacus: experimental and theoretical studies of femtosecond pump-probe spectra. Photosynth. Res. 71, 19–32 (2002).

Taisova, A. S., Yakovlev, A. G. & Fetisova, Z. G. Size Variability of the unit building block of peripheral light-harvesting antennas as a strategy for effective functioning of antennas of variable size that is controlled in vivo by light intensity. Biochem. Mosc. 79, 251–259 (2014).

Pšenčík, J. et al. Lamellar organization of pigments in chlorosomes, the light harvesting complexes of green photosynthetic bacteria. Biophys. J. 87, 1165–1172 (2004).

Pšenčík, J. et al. Structure of chlorosomes from the green filamentous bacterium Chloroflexus Aurantiacus. J. Bacteriol. 191, 6701–6708 (2009).

Egawa, A. et al. Structure of the light-harvesting Bacteriochlorophyll c assembly in chlorosomes from Chlorobium Limicola determined by solid-state NMR. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA104, 790–795 (2007).

Ganapathy, S. et al. Alternating Syn-Anti bacteriochlorophylls form concentric helical nanotubes in chlorosomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 8525–8530 (2009).

Tian, Y. et al. Organization of bacteriochlorophylls in individual chlorosomes from Chlorobaculum tepidum studied by 2-dimensional polarization fluorescence microscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 17192–17199 (2011).

Vogl, K., Tank, M., Orf, G. S., Blankenship, R. E. & Bryant, D. A. Bacteriochlorophyll f: properties of chlorosomes containing the “forbidden chlorophyll. Front. Microbiol. 3, 298 (2012).

Dsouza, L. et al. An integrated approach towards extracting structural characteristics of chlorosomes from a bchQ mutant of Chlorobaculum Tepidum. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 26, 15856–15867 (2024).

Garcia Costas, A. M. et al. Ultrastructural analysis and identification of envelope proteins of “Candidatus Chloracidobacterium Thermophilum” chlorosomes. J. Bacteriol. 193, 6701–6711 (2011).

Bystrova, M., Malgosheva, I. & Krasnovskii, A. Study of molecular mechanism of self-assembly of aggregated forms of bacteriochlorophyll-C. Mol. Biol.13, 440–451 (1979).

Kishi, M., Nakamura, Y. & Tamiaki, H. Effect of additional hydroxy group on self-aggregation of synthetic zinc bacteriochlorophyll-c analogs. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 400, 112592 (2020).

Furumaki, S. et al. Absorption linear dichroism measured directly on a single light-harvesting system: the role of disorder in chlorosomes of green photosynthetic bacteria. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 6703–6710 (2011).

Günther, L. M. et al. Structure of light-harvesting aggregates in individual chlorosomes. J. Phys. Chem. B 120, 5367–5376 (2016).

Günther, L. M. et al. Structural variations in chlorosomes from wild-type and a bchQR mutant of Chlorobaculum Tepidum revealed by single-molecule spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 122, 6712–6723 (2018).

Günther, L. M., Knoester, J. & Köhler, J. Limitations of linear dichroism spectroscopy for elucidating structural issues of light-harvesting aggregates in chlorosomes. Molecules 26, 899 (2021).

Prokhorenko, V. I. et al. Energy transfer in supramolecular artificial antennae units of synthetic zinc chlorins and co-aggregated energy traps. a time-resolved fluorescence study. J. Phys. Chem. B 106, 5761–5768 (2002).

Savikhin, S., Zhu, Y., Blankenship, R. E. & Struve, W. S. Ultrafast energy transfer in chlorosomes from the green photosynthetic bacterium Chloroflexus aurantiacus. J. Phys. Chem. 100, 3320–3322 (1996).

Pšenčík, J. et al. Internal structure of chlorosomes from brown-colored chlorobium species and the role of carotenoids in their assembly. Biophys. J. 91, 1433–1440 (2006).

Dostál, J. et al. Two-dimensional electronic spectroscopy reveals ultrafast energy diffusion in chlorosomes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 11611–11617 (2012).

Prokhorenko, V. I., Steensgaard, D. B. & Holzwarth, A. R. Exciton dynamics in the chlorosomal antennae of the green bacteria Chloroflexus aurantiacus and Chlorobium tepidum. Biophys. J. 79, 2105–2120 (2000).

Frehan, S. K. et al. Photon energy-dependent ultrafast exciton transfer in chlorosomes of Chlorobium Tepidum and the role of supramolecular dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. B 127, 7581–7589 (2023).

Zupcanova, A. et al. The length of esterifying alcohol affects the aggregation properties of chlorosomal bacteriochlorophylls. Photochem. Photobiol. 84, 1187–1194 (2008).

Dang, X. et al. Tunable localized surface plasmon-enabled broadband light-harvesting enhancement for high-efficiency panchromatic dye-sensitized solar cells. Nano Lett. 13, 637–642 (2013).

Lee, M. et al. Aluminum nanoarrays for plasmon-enhanced light harvesting. ACS Nano 9, 6206–6213 (2015).

Atwater, H. A. & Polman, A. Plasmonics for improved photovoltaic devices. Nat. Mater. 9, 205–213 (2010).

Zhang, Q. et al. Seed-mediated synthesis of Ag nanocubes with controllable edge lengths in the range of 30−200 Nm and comparison of their optical properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 11372–11378 (2010).

Orendorff, C. J., Sau, T. K. & Murphy, C. J. Shape-dependent plasmon-resonant gold nanoparticles. Small 2, 636–639 (2006).

Du, X., Liu, L. & Ye, J. Plasmonic metal nanoparticles for artificial photosynthesis: advancements, mechanisms, and perspectives. Sol. RRL 5, 2100611 (2021).

Ly, N. H., Vasseghian, Y. & Joo, S.-W. Plasmonic photocatalysts for enhanced solar hydrogen production: a comprehensive review. Fuel 344, 128087 (2023).

Verma, P. et al. Plasmonic heterojunction photocatalysts for hydrogen generation: a mini-review. Energy Fuels 37, 17652–17666 (2023).

Langer, J. et al. Present and future of surface-enhanced Raman scattering. ACS Nano 14, 28–117 (2020).

Aslam, U., Rao, V. G., Chavez, S. & Linic, S. Catalytic conversion of solar to chemical energy on plasmonic metal nanostructures. Nat. Catal. 1, 656–665 (2018).

Chen, H., Kou, X., Yang, Z., Ni, W. & Wang, J. Shape- and size-dependent refractive index sensitivity of gold nanoparticles. Langmuir 24, 5233–5237 (2008).

Ringe, E. Shapes, plasmonic properties, and reactivity of magnesium nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C. 124, 15665–15679 (2020).

Lounis, S. D., Runnerstrom, E. L., Llordés, A. & Milliron, D. J. Defect chemistry and plasmon physics of colloidal metal oxide nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 5, 1564–1574 (2014).

Maier, S. A. Plasmonics: Fundamentals and Applications, 1st edn (Springer New York, NY, 2007).

Weitz, D. A., Garoff, S., Gersten, J. I. & Nitzan, A. The enhancement of Raman scattering, resonance Raman scattering, and fluorescence from molecules adsorbed on a rough silver surface. J. Chem. Phys. 78, 5324–5338 (1983).

Gersten, J. & Nitzan, A. Electromagnetic theory of enhanced Raman scattering by molecules adsorbed on rough surfaces. J. Chem. Phys. 73, 3023–3037 (1980).

Liao, P. F. & Wokaun, A. Lightning rod effect in surface enhanced Raman scattering. J. Chem. Phys. 76, 751–752 (1982).

F. Aroca, R. Plasmon enhanced spectroscopy. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3CP44103B.

Wientjes, E. et al. Nanoantenna enhanced emission of light-harvesting complex 2: the role of resonance, polarization, and radiative and non-radiative rates. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 24739–24746 (2014).

Wientjes, E., Renger, J., Curto, A. G., Cogdell, R. & van Hulst, N. F. Strong antenna-enhanced fluorescence of a single light-harvesting complex shows photon antibunching. Nat. Commun. 5, 4236 (2014).

Wientjes, E., Renger, J., Cogdell, R. & van Hulst, N. F. Pushing the photon limit: nanoantennas increase maximal photon stream and total photon number. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7, 1604–1609 (2016).

Mahajan, T. et al. Broadband enhancement in absorption cross-section of N719 dye using different anisotropic shaped single crystalline silver nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 6, 48064–48071 (2016).

Kaushik, T., Ghosh, S., Dolkar, T., Biswas, R. & Dutta, A. Noble metal plasmon–molecular catalyst hybrids for renewable energy relevant small molecule activation. ACS Nanosci. Au 4, 273–289 (2024).

Jeanmaire, D. L. & Van Duyne, R. P. Surface Raman spectroelectrochemistry. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem. 84, 1–20 (1977).

Moskovits, M. Surface roughness and the enhanced intensity of Raman scattering by molecules adsorbed on metals. J. Chem. Phys. 69, 4159–4161 (1978).

Albrecht, M. G. & Creighton, J. A. Anomalously intense Raman spectra of pyridine at a silver electrode. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 99, 5215–5217 (1977).

Alan Creighton, J. G., Blatchford, C. Grant Albrecht, M. Plasma resonance enhancement of raman scattering by pyridine adsorbed on silver or gold sol particles of size comparable to the excitation wavelength. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 2 Mol. Chem. Phys. 75, 790–798 (1979).

Huang, Y.-F. et al. When the signal is not from the original molecule to be detected: chemical transformation of para-aminothiophenol on Ag during the SERS measurement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 9244–9246 (2010).

Tsargorodska, A. et al. Strong coupling of localized surface plasmons to excitons in light-harvesting complexes. Nano Lett. 16, 6850–6856 (2016).

Czechowski, N. et al. Large plasmonic fluorescence enhancement of cyanobacterial photosystem I coupled to silver island films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 043701 (2014).

Barazzouk, S., Bekalé, L. & Hotchandani, S. Enhanced photostability of chlorophyll- a using gold nanoparticles as an efficient photoprotector. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 25316–25324 (2012).

Kim, I. et al. Metal nanoparticle plasmon-enhanced light-harvesting in a photosystem I thin film. Nano Lett. 11, 3091–3098 (2011).

Noji, T. et al. Photosystem II–gold nanoparticle conjugate as a nanodevice for the development of artificial light-driven water-splitting systems. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2, 2448–2452 (2011).

Kyeyune, F. et al. Strong plasmonic fluorescence enhancement of individual plant light-harvesting complexes. Nanoscale 11, 15139–15146 (2019).

Mackowski, S. et al. Metal-enhanced fluorescence of chlorophylls in single light-harvesting complexes. Nano Lett. 8, 558–564 (2008).

Hildebrandt, N. et al. Plasmonic quenching and enhancement: metal–quantum dot nanohybrids for fluorescence biosensing. Chem. Commun. 59, 2352–2380 (2023).

Kowalska, D. et al. Silver island film for enhancing light harvesting in natural photosynthetic proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 2451 (2020).

Yunusa, U., Warren, N., Schauer, D., Srivastava, P. & Sprague-Klein, E. Plasmon resonance dynamics and enhancement effects in tris(2,2′-bipyridine)ruthenium(II) gold nanosphere oligomers. Nanoscale 16, 5601–5612 (2024).

Schauer, D. G. et al. Targeted synthesis of gold nanorods and characterization of their tailored surface properties using optical and X-ray spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 26, 25581–25589 (2024).

Zhang, T., Li, X., Li, C., Cai, W. & Li, Y. One-pot synthesis of ultrasmooth, precisely shaped gold nanospheres via surface self-polishing etching and regrowth. Chem. Mater. 33, 2593–2603 (2021).

Goy-López, S., Castro, E., Taboada, P. & Mosquera, V. Block copolymer-mediated synthesis of size-tunable gold nanospheres and nanoplates. Langmuir 24, 13186–13196 (2008).

Chen, H., Shao, L., Li, Q. & Wang, J. Gold nanorods and their plasmonic properties. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 2679–2724 (2013).

Kou, X., Sun, Z., Yang, Z., Chen, H. & Wang, J. Curvature-directed assembly of gold nanocubes, nanobranches, and nanospheres. Langmuir 25, 1692–1698 (2009).

Wu, H.-L. et al. A comparative study of gold nanocubes, octahedra, and rhombic dodecahedra as highly sensitive SERS substrates. Inorg. Chem. 50, 8106–8111 (2011).

Khoury, C. G. & Vo-Dinh, T. Gold nanostars for surface-enhanced Raman scattering: synthesis, characterization and optimization. J. Phys. Chem. C 112, 18849–18859 (2008).

Barbosa, S. et al. Tuning size and sensing properties in colloidal gold nanostars. Langmuir 26, 14943–14950 (2010).

Baia, L., Baia, M., Popp, J. & Astilean, S. Gold films deposited over regular arrays of polystyrene nanospheres as highly effective SERS substrates from visible to NIR. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 23982–23986 (2006).

Farcau, C. & Astilean, S. Mapping the SERS efficiency and hot-spots localization on gold film over nanospheres substrates. J. Phys. Chem. C 114, 11717–11722 (2010).

Acknowledgements

Research supported by SVV–2025–260832 from Charles University and by Brown University startup funds. The authors also acknowledge research support from the Initiative for Sustainable Energy seed funding. E.D. and E.S.K. acknowledge academic infrastructure provided by the Initiative for Maximizing Student Development (IMSD) at Brown NIH T32 training grant and university support as well as graduate student support from the Rhode Island Space Grant Consortium (NASA Rhode Island Space Grant Consortium). We also acknowledge support through the multidisciplinary partnership between Brown-Charles University, facilitated by the Office of Global Engagement (Prof. Masako Fidler, in memory of Prof. Vlastimil Fidler).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.D.: conceptualized the perspective; prepared figures; wrote introduction, plasmonics, and outlook sections; and edited and reviewed manuscript. T.M.: prepared figures; wrote section on design considerations for artificial light-harvesting antennas based on natural pigments; and edited and reviewed manuscript. E.S.: contributed to plasmonics section, and edited and reviewed the manuscript. J.P.: edited and reviewed manuscript. E.A.S.-K.: conceptualized the perspective; supervision; edited and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Marcin Szalkowski and Takehisa Dewa for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Donahue, E., Malina, T., Smith, E. et al. Photophysics of plasmonically enhanced self-assembled artificial light-harvesting nanoantennas. Commun Chem 8, 263 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01664-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01664-2