Abstract

Propylene epoxidation with hydrogen and oxygen to prepare propylene oxide (PO) offers advantages in cleanliness, efficiency and flexibility. The Au/TS-1 catalyst exhibits great catalytic activity for the gas-phase epoxidation of propylene, which is attributed to the synergistic effect between Au nanoparticles and TS-1 zeolites: Au catalyzes the in situ generation of HOOH, and framework Ti atoms catalyze the oxygen addition to the double bond of propylene. Despite these benefits, the catalytic performance of Au-Ti catalysts remains insufficient for industrial applications, primarily due to their limited activity, excessive byproduct formation, and catalyst deactivation. Current strategies focus on enhancing active site exposure, optimizing pore structure and Au dispersion, suppressing side reactions, and improving diffusion kinetics. This review systematically evaluates advancements in catalyst design, proposes research directions for designing regeneration strategies and mitigating safety risks, offering actionable insights to accelerate the development of industrially viable catalytic systems for PO synthesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Propylene oxide (PO) is a key organic chemical raw material primarily used in the production of downstream products, such as polyether, propylene glycol, and non-ionic surfactants1,2. One of its major derivatives, polyurethane, has widespread applications in sound insulation, packaging, thermal insulation, and heat preservation, meeting the demands of industries such as construction, aviation, and healthcare. Furthermore, PO can absorb carbon dioxide (CO2) and is employed in the synthesis of biodegradable plastics, specifically polypropylene carbonate. As applications involving CO2-based polymers and dimethyl carbonate continue to expand, the demand for PO is expected to rise steadily. This trend is highly important for achieving carbon neutrality and addressing environmental protection issues.

Currently, the production methods for PO include the chlorohydrin process, co-oxidation processes (PO/SM, PO/TBA, and PO/MTBE), liquid-phase direct oxidation methods (HPPO, hydrogen peroxide to PO; and CHPPO, cumene hydroperoxide to PO), and the gas-phase direct oxidation method, as shown in Fig. 1. The chlorohydrin and co-oxidation processes are traditional methods for producing PO, accounting for about 90% of global PO production. However, the chlorohydrin process presents significant issues, such as severe equipment corrosion and substantial wastewater generation, making it inconsistent with the concept of green development. The co-oxidation process requires the coproduction of 2.2 to 2.5 times the amount of styrene or tert-butanol, and its economic viability is largely influenced by the market supply and demand for these coproducts3. The HPPO and CHPPO processes, which are catalyzed by titanium-based materials, utilize hydrogen peroxide (H2O2 or HOOH) and cumene hydroperoxide (CHP) as oxidants, respectively. These methods offer several advantages, including environmental sustainability, effective cost control, low pollutant emissions, and mild reaction conditions, positioning them as green production technologies that are strongly supported and encouraged4. Despite these benefits, the liquid-phase direct oxidation process faces notable challenges. The stringent storage and transportation requirements for peroxides necessitate their on-site production, limiting flexibility in process layout. Additionally, the handling of high-concentration peroxides raises concerns related to their preparation and storage. To address these limitations fundamentally, Haruta et al. were the first to propose an Au−Ti catalyst capable of enabling the direct gas-phase oxidation of propylene (C3H6) to produce PO in a single step under a hydrogen (H2) and oxygen (O2) atmosphere5. This gas-phase C3H6 epoxidation is a gas-solid phase reaction that is easy to perform and offers simple product separation. The process demonstrates high economic efficiency and environmental compatibility and aligns with the green development trends of the PO industry.

Haruta et al. reported that neither nano-sized Au nor TiO2 alone showed any catalytic activity for the conversion of C3H6, indicating that both components are indispensable for the selective epoxidation of C3H65. Catalysts such as Pd/TiO2 and Pt/TiO2 primarily catalyze the hydrogenation of C3H6 to C3H8, yielding only trace amounts of acetone as oxygenated byproducts. These findings demonstrate that Au simultaneously activates O2 to form O2– and promotes H2 dissociation. This leads to the in situ generation of HOOH-oxidizing species6, thereby facilitating its synergistic catalytic role with Ti-containing catalysts in the C3H6 epoxidation7. Various Au-supported Ti-containing catalysts have been applied to gas-phase C3H6 epoxidation, as summarized in Table 1. Studies have shown that amorphous Ti-based supports lead to excessive side reactions due to the presence of TiO2 or amorphous Ti species8,9. For example, in the Au/Ti-SiO2-catalyzed gas-phase C3H6 epoxidation, CO2 accounted for up to 16% of the byproducts10. Similarly, the presence of Ti-O-Ti linkages in the Au/amorphous meso-Ti-O-Si catalyst increased CO2 selectivity11. Therefore, a series of crystalline Ti-containing catalysts with different pore structures (e.g., Ti-SBA-15, Ti-MCM-41, and TS-2) were prepared. These catalysts exhibited significantly higher PO selectivities than those based on amorphous Ti-containing supports. Nevertheless, their catalytic pathways still deviated from the ideal PO formation, likely due to structural differences in the active Ti sites. Although catalysts such as Au/Ti-MCM-41 and Au/TS-2 did not show detectable TiO2 species, they still contained other forms of Ti species, resulting in higher amounts of CO2 and aldehyde byproducts12. Additionally, the synergistic interactions between Au and Ti-containing crystalline materials (e.g., Ti-SBA-15, Ti-MCM-41, and TS-2) were relatively weak, limiting C3H6 conversion and PO formation rate.

Notably, Au/TS-1 demonstrated excellent catalytic performance in the gas-phase C3H6 epoxidation13. The incorporation of tetrahedrally coordinated Ti atoms into the TS-1 framework renders it highly suitable for catalyzing the partial oxidation of C3H6 to produce PO14,15. Specifically, these Ti atoms possess empty orbitals capable of accepting lone pair electrons from the oxygen atoms in HOOH, forming active Ti-OOH centers. Upon approaching these centers, the C=C double bond in C3H6 undergoes an electrophilic reaction, leading to the formation of PO. Furthermore, TS-1 facilitates the high dispersion of metal nanoparticles (NPs) through strong metal-support interactions, thereby generating a greater number of active sites and enhancing the synergetic effects of Au-Ti.

Therefore, Au/TS-1 has been widely employed as a catalyst in the gas-phase epoxidation reaction of C3H6. Its surface properties and pore structures have been modified or controlled to improve C3H6 conversion, PO selectivity, and reaction stability, as depicted in Table 2. However, it has not yet been transferred into an industrial application. The primary barrier to industrialization lies in the challenge of ensuring both high reaction performance and process safety. Specifically for catalysts, achieving a balance between C3H6 conversion greater than> 10% and PO selectivity exceeding 90% remains difficult, with catalyst stability typically less than 1000 h. This combined technical gap creates critical economic barriers, rendering the overall process economically unviable for industrial-scale deployment. These issues not only affect the production capacity and economic viability of the process but also pose risks to reaction safety — deep oxidation may lead to significant heat release and even an explosive risk in the reactor bed. To support and guide the development of catalytic materials for the C3H6 epoxidation reaction, this review presents a comprehensive analysis of recent studies, focusing on the structure-activity relationships of Au-Ti-based catalysts. This work examines the key factors limiting catalytic performance, summarizes strategies for regulating catalyst structure and surface modification, and categorizes the intrinsic factors that enhance catalytic performance along with their implications for future research. By understanding these aspects, this work intends to advance the industrial application of catalytic materials.

Strategies to achieve high reaction conversion

Currently, C3H6 conversion generally remains below 15% (based on PO selectivity exceeding 90%), which significantly restricts the economic viability and industrial application of the gas-phase C3H6 epoxidation reaction. This reaction is catalyzed by Au-Ti dual active centers, where the catalytic activity involves not only the in situ generation of HOOH intermediate species by Au but also the adsorption and transformation of C3H6 on Ti active sites, along with the migration and effective utilization of HOOH species16. Therefore, the synergistic interaction between the Au and Ti active sites is closely related to the reaction activity17,18, as shown in Fig. 2.

Reaction mechanism

Currently, two proposed mechanisms for the gas-phase C3H6 epoxidation over Au/TS-1 catalysts exist: the sequential and simultaneous reaction mechanisms. The sequential reaction mechanism suggests that HOOH generated on Au transfers to adjacent framework Ti atoms, forming Ti–OOH active sites that subsequently catalyze the epoxidation of C3H6 to PO. Through in situ UV-vis characterization, Haruta et al. observed Ti–OOH species (evidenced by a characteristic peak at 370 nm indicating charge transfer between -OOH and Ti4+) on Au/Ti-SiO2 catalyst surfaces, supporting the plausibility of a sequential mechanism6. Kinetic studies revealed that the formation rate of Ti-OOH species is significantly slower than their consumption rate by C3H6, indicating that effective HOOH generation is the rate-determining step governing PO production19,20. However, the absence of transient kinetic data leaves uncertainty regarding whether Ti-OOH serves as a true reaction intermediate, prompting skepticism about this mechanism. For example, Thomson’s DFT simulations demonstrated that the energy barrier for HOOH to form Ti-OOH on tetrahedrally coordinated Ti sites adjacent to Au (32.1 kcal/mol) substantially exceeds that for isolated framework Ti atoms (16.8 kcal/mol), suggesting kinetic limitations in the sequential pathway21. The parallel reaction mechanism involves direct interactions between HOOH (generated on the Au surface) and C3H6 adsorbed on Ti active sites. Delgass et al. determined reaction orders of 0.60, 0.31, and 0.18 for H2, O2, and C3H6, respectively, and concluded that the rate-determining HOOH formation requires dual active centers—a condition unmet by the sequential mechanism22,23. In this parallel pathway, the critical step involves C3H6 attacking the H-Au-OOH species to form PO and water, simultaneously engaging both Au and tetrahedrally coordinated Ti atoms as cooperative catalytic centers.

The above reaction mechanisms correspond to distinct Au loading positions on the TS-1 zeolite. The simultaneous mechanism involves the dispersion of Au species—such as single atoms, dimers, or subnanometer clusters (<2 nm)—within the TS-1 crystal. In this case, the Au and Ti active sites are in proximity, allowing H2 and O2 to directly generate Ti-OOH species at the Ti sites without requiring the migration of HOOH24,25. In contrast, the sequential mechanism involves dual active centers, Au-Ti, that are spatially separated. In this scenario, Au NPs are typically deposited on the external surface of TS-1, where the distance between the Au and the abundant Ti sites within the bulk is relatively large. The active oxygen species HOOH generated by the Au NPs must migrate to the distant Ti site to form the Ti-OOH active center before catalyzing the epoxidation of C3H6 to form PO. There is an ongoing debate regarding the dominant reaction mechanism. Generally, both proposed mechanisms coexist in the Au-Ti catalytic system26,27.

Increasing the number of active sites

The number of active sites is closely related to the reaction activity. An increase in the number of Au and Ti active sites leads to corresponding improvements in the in situ generation of HOOH and C3H6 adsorption28,29,30,31. It is generally believed that the tetra-coordinated Ti within the TS-1 framework serves as the active site for C3H6 conversion32. TS-1 zeolites with blocked pores undergo varying degrees of thermal treatment, which removes different amounts of TPA+ template ions. Studies have shown that reducing the TPA+ content exposes more (101) crystal faces and framework Ti species, thereby enhancing C3H6 adsorption and considerably improving catalytic activity, which in turn doubles the PO formation rate33,34,35. During the synthesis of the titania-silica precursor, TiO2 aggregation is reversed by hydroxyl radicals generated in situ via ultraviolet irradiation, which aligns with the hydrolysis rates of the Ti and Si sources. As a result, all Ti atoms are successfully incorporated into the TS-1 framework, resulting in a high content of tetra-coordinated Ti active sites. This contributes to a C3H6 conversion rate of 8.8%36. By calcining TS-1 under an inert N2 atmosphere at lower temperatures, the detachment of Ti atoms from the framework can be effectively mitigated, thereby reducing the content of extra-framework TiO2. This approach significantly improves both the HOOH utilization efficiency and the epoxidation efficiency37.

Ni2+, when used as a co-precipitating agent alongside Na+, provided a significant amount of positive charge during the Au loading process. Ni2+ acts as a bridge by neutralizing the negative charges on the TS-1 surface and counterbalancing those of the [Au(OH)x(Cl)4-x]− precursor complex. This enhanced electrostatic attraction between the Au precursors and the TS-1 support ultimately improved the Au capture efficiency and achieved a C3H6 conversion of 10.5%38. The introduction of phosphate species onto TS-1 further facilitated Au capture, resulting in the formation of smaller, more active Au sites, as Au species preferentially deposit at P-rich positions39. Delgass et al. treated TS-1 with NH4NO3 to impart a surface with abundant -NH2 groups. The coordination effect between -NH2 and Au increased the Au capture efficiency by 75%16. Haruta et al. employed the KOH dissolution method to treat TS-1, generating more Si-OH and Ti-OH defects on the surface, which facilitated the anchoring of Au nanoparticles40. These hydroxyl structures act as electron donors, transferring electrons to adjacent Au nanoparticles. O2 subsequently captured electrons from the Au surface to form O2− intermediates. The newly deposited Au on the TS-1 support exists predominantly as Au+ species, with minor amounts of Au0 and Au3+. O2 is activated to O2− through electron transfer from Au, which subsequently reacts with H2 to form the OOH species. Therefore, electron-enriched Au species (i.e., Au0) facilitate HOOH production41. Research indicates that pre-treatment in either H2 or feed gas atmospheres (comprising H2, O2, C3H6, and N2) promotes the formation of Au0. Initially, H2 pre-treatment encourages the disproportionation of Au+ to Au0. Subsequent treatment with the feed gas further reduces Aun+ species, leading to an Au0 proportion as high as 99% and a PO formation rate of 220 gPO•h–1•kgCat–1 42. When Na3Au(S2O3)2 was used as the Au precursor, residual sulfur-based compounds remained on the Au surface. These electronegative species withdraw electrons from Au, increasing its electron binding energy and favoring the formation of additional Au0 species. The lower charge density of Au0 enhances its ability to attract electrons from hydrogen atoms, thereby reducing the dissociation energy of H2 and promoting HOOH formation43. Furthermore, owing to the difference in electronegativity between Pt and Au, electron transfer from Pt to Au occurs in Pt-Au alloys, increasing their capacity to activate O2. This process facilitates HOOH generation and increases the C3H6 conversion rate to 11%44,45.

Improving active intermediate utilization efficiency

Kinetic Monte Carlo simulations have demonstrated that maximizing the local availability of HOOH near Ti sites is crucial for accelerating PO production20,46. While the number of Au active sites within the TS-1 crystal is limited, their high activity ensures rapid utilization of the HOOH generated by nearby Ti sites, playing an important catalytic role47,48,49,50,51. A shorter Au-Ti distance facilitates electron transfer from Ti to Au, promoting Au0-catalyzed O2 activation and HOOH generation. The generated HOOH can rapidly migrate to adjacent Ti active sites. Furthermore, Ti, which has increased electron binding energy after electron transfer, can effectively share electrons with the C=C bond of C3H6, thereby strengthening C3H6 adsorption. However, owing to the narrow channels and mass transfer resistance of TS-1, a greater proportion of Au tends to accumulate on the external surface. Under such conditions, HOOH must migrate over a longer distance to reach the Ti active site, increasing its likelihood of decomposition and restricting overall catalytic activity52. Nevertheless, when an excessive amount of Au is confined within the TS-1 micropores, the narrow channels can impose diffusion limitations, hindering the accessibility of reactants to Au sites located deeper inside the micropores. Therefore, the Au NPs loaded on the surface of TS-1 also contribute substantially to its catalytic activity53. Additionally, when numerous C3H6 molecules adsorb onto single Au atoms, causing their deactivation, the Au NPs can supply HOOH for reaction with C3H6, thereby releasing single Au atoms to achieve superior catalytic activity. The coexistence of single Au atoms and Au NPs in the system results in a synergistic catalytic effect. This synergy leads to optimal catalytic performance54.

To increase the reaction activity, researchers have aimed to introduce more active Au sites into TS-1 crystals, thereby strengthening the interaction between the Au and Ti active sites and improving both the HOOH utilization efficiency and C3H6 conversion. However, the microporous structure of TS-1 accommodates only a limited number of Au sites. To overcome this limitation, hierarchical TS-1 with mesopore channels has been explored as a support for Au loading. In addition, in situ encapsulation of Au within the TS-1 crystal reduced the Au−Ti distance. By combining deposition−precipitation and impregnation methods, the capillary effect allowed uniform dispersion of Au within the mesopores of HTS-1, facilitating the transfer of HOOH from Au to the adjacent abundant Ti active sites and leading to a 2.4-fold increase in C3H6 conversion55. 3-Mercaptopropyl trimethoxysilane was introduced to ligate with the Au precursor during the hydrothermal crystallization of the Ti-Si sol-gel, enabling the construction of the TS-1 framework around the Au species56. Ti atoms anchored to Au in the form of Ti-phenol through the reducing and coordinating abilities of tannic acid encapsulate a uniform dispersion of Au NPs in proximity to highly dispersed framework Ti species. The bridging oxygen interaction at the Au-(O)-Ti interface enhanced perturbations in the microenvironment surrounding the framework Ti atoms, thereby improving the stability and catalytic activity of Ti-OOH57. Au-Ti@MFI catalysts were prepared by combining seed-induced, solvent-free crystallization with bioextraction. The encapsulating structure of the Ti-containing zeolite ensured intimate contact and strong electronic interactions between Au and Ti. This interaction promoted the generation and transfer of HOOH, achieving a C3H6 conversion rate of 14.8%58. By removing O atoms near Ti atoms in the TS-1 framework, oxygen vacancies are created to serve as anchoring sites stabilizing Au. The Au-Ti distance is reduced to 2.6 Å, significantly enhancing the electron-acquiring capability of Au. This effectively prevents the degradation of *OOH, achieving a H2 efficiency as high as 45%59. Compared with the Au deposited on the external surface of TS-1 or dispersed within its mesopore channels, the Au confined within the TS-1 micropores is typically located closer to the Ti active sites. This reduced Au-Ti distance, along with more frequent atomic contacts, offers kinetic benefits for gas-phase C3H6 epoxidation.

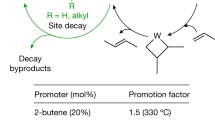

Strategies to achieve high selectivity

Side reactions involving either the C3H6 feedstock or the PO product are likely to occur during the gas-phase C3H6 epoxidation catalyzed by Au/TS-1, as shown in Fig. 3. The Au sites catalyze the cracking of C3H6 to form acetaldehyde, its hydrogenation to produce propane, and its hydroxylation to yield acrolein, with a combined selectivity of about 5%. In particular, the incomplete reduction of the Au active sites during the pre-treatment step leaves some residual Au+ ions, which promote the hydrogenation of C3H6 to form propane60. Additionally, larger Au particles (>5 nm) also tend to facilitate the hydrogenation reaction61,62,63,64. The interaction of H2 and O2 at the Au sites not only generates HOOH but also produces *OOH active oxygen species on the Au65 surface66. These *OOH species further decompose into O* and OH*, with the highly reactive O* attacking the allylic intermediate of C3H6 through dehydrogenation, leading to the formation of acrolein as a byproduct67,68. To mitigate these undesired side reactions associated with Au sites, researchers have employed precipitation or improved impregnation methods to load Au while controlling its particle size, thereby increasing O2 activation and H2 dissociation. The promotion of electron transfer enables the formation of more Au0 active sites, effectively suppressing these side reactions.

Ti3+ sites can also catalyze PO oxidation to form acrolein within the micropores of TS-1 zeolite69. Notably, the primary side reaction in this system involves the PO isomerization to propanal and acetone, with a byproduct selectivity of about 10%. This side reaction primarily arises from limited molecular diffusion within the catalyst and the presence of secondary reaction centers. The narrow micropore channels of the MFI topology in the TS-1 zeolite (0.55 nm in diameter) hinder the timely desorption and diffusion of PO from the active sites and out of the catalyst channels, thereby promoting side reactions. To prove this, S-1 shells of varying thicknesses were coated on the surface of TS-1 to modify the diffusion pathways of PO within the catalyst. It is observed that as the thickness of the S-1 shell increased, the PO diffusion out of the catalyst became more restricted. In contrast, its susceptibility to side reactions increased, resulting in a linear decline in PO selectivity70. Additionally, the acidic hydroxyl groups (Ti-OH or Si-OH) on TS-1 enhance the adsorption of PO onto the catalyst surface. Through interactions involving the electronegative oxygen atoms of PO, Ti atoms, and hydroxyl groups, PO undergoes a ring-opening reaction to form propanal and acetone71,72. In situ infrared characterization of PO adsorption revealed that a reduction in the number of hydroxyl defects on the TS-1 surface significantly weakens PO adsorption at hydroxyl sites, while simultaneously improving PO selectivity73. To mitigate the formation of propanal and acetone byproducts, modifications to the catalyst structure and properties are implemented based on the underlying mechanisms for their formation. These efforts focused on two main strategies: enhancing the diffusion rate of PO within the TS-1 crystals and eliminating the catalytic centers responsible for PO isomerization.

Increasing the mass transfer ability

Promoting the rapid desorption and diffusion of PO from the exterior of the Au/TS-1 catalyst can prevent PO from undergoing the isomerization reaction. One approach to achieve this is by shortening the diffusion pathway of PO within the TS-1 crystals, whereas another approach involves increasing its intracrystalline diffusion rate. Both strategies require regulation of the TS-1 structure, as shown in Fig. 4.

Modification of TS-1 morphological structure

To shorten the diffusion pathway of PO within TS-1 zeolite, small-crystalline and lamellar TS-1 structures were developed as Au-loaded supports. The TS-1 crystal size can be reduced from 880 nm to 200 nm by controlling the amount of template agent. As the crystal size decreased, the diffusion distance correspondingly decreased, allowing PO to quickly diffuse to the catalyst exterior. This modification increased PO selectivity from 78% to 91%, while reducing the selectivity for propanal and acetone byproducts from 15% to 6%74. Furthermore, the addition of urea inhibits crystal growth along the (010) plane, reducing the length in the b-axis direction to just 95 nm and yielding a lamellar morphology. The MFI-type framework of TS-1 contained straight ten-membered ring channels parallel to the b-axis, enabling rapid PO diffusion through these shortened channels and achieving a PO selectivity of 92%75. A thin layer of TS-1 was coated onto the surface of hierarchical S-1 to prepare the Au/TS-1/S-1-H catalysts. The mesopores of S-1, combined with the shorter channel distance of TS-1, effectively enhance the PO diffusion rate, increasing PO selectivity by 7%76. Although these methods reduce the diffusion pathway for PO, C3H6 and other reactants also diffuse rapidly through the catalyst. This rapid diffusion, coupled with their weak adsorption to the abundant active sites within the catalyst channels, results in low C3H6 conversions of only 3.9%, 3.8%, and 2.3%, respectively.

Modification of TS-1 channel structure

To reduce the intracrystalline mass transfer resistance of PO, mesopores were introduced to prepare hierarchical TS-1 zeolites77. Hierarchical MTS-1 zeolites featuring a mesopore channel of 3.4 nm were synthesized via a dry-gel conversion method. Au/MTS-1 catalyzes the gas-phase C3H6 epoxidation with a PO selectivity of 94%78. Additionally, increasing the number of micropores in TS-1 enhanced the PO diffusion rate of PO within the crystal. Secondary micropores were incorporated into the existing MFI structure of TS-1 through dehydration condensation between chlorosilane and titanosilicate precursors, leading to a hierarchical microporous TS-1 that achieved a PO selectivity of 92.7%79. These aforementioned strategies preserve the original TS-1 structure while introducing additional pores, thereby promoting PO diffusion through the newly formed pore network and maintaining C3H6 adsorption and conversion at the active sites of the original framework. Consequently, these approaches enhance PO selectivity while achieving relatively high C3H6 conversions of 7.7% and 13.3%, respectively.

Elimination of the by-product catalysis center

Eliminating acidic hydroxyl groups from the catalyst can fundamentally inhibit the isomerization of PO. It is crucial to control the degree of hydroxyl modification, ensuring effective Au loading while minimizing hydroxyl generation to maximize the reaction efficiency. The hydroxyl species present on Au/TS-1 include Si-OH and Ti-OH groups. However, it remains uncertain which specific type of hydroxyl group acts as the catalytic center for PO isomerization80,81. Therefore, various catalyst modification methods were employed to selectively remove the target hydroxyl groups, as illustrated in Fig. 5.

Selective elimination of Si-OH groups

When Cs2CO3 was used as the precipitating agent for Au loading, the Cs+ ions underwent ion exchange with Si-OH groups on TS-1, forming Si-O-Cs species. This exchange moderated the surface acidity and effectively suppressed PO isomerization, achieving a PO selectivity of 91.2%82. Zhou et al. reported that H* released from H2 dissociation on Au interacted with Si-OH groups through hydrogen exchange. The spilled-over hydrogen from Si-OH contributed to protonation effects, thereby leading to the isomerization of PO. To address this, a continuous silylation treatment was employed to selectively eliminate Si-OH groups and obtain a ternary Au-Ti(-OH)-Si(-O-SiR3) catalytic center, achieving a H2 efficiency of 42.5% and a PO selectivity of 95.7%83,84.

Selective elimination of Ti-OH groups

When NH4OH was used as the precipitating agent for Au loading to preserve the acidic Ti-OH groups on Ti-SiO2, the selectivity toward propanal reached 83.4%, with only a minor amount of PO generated. This indicates that Ti-OH serves as the active site responsible for catalyzing PO isomerization. Using Na2CO3 as the precipitating agent facilitated the neutralization of acidic Ti sites by Na+ ions, resulting in an increased PO content in the product mixture85. Additionally, depositing a porous SiO2 shell on the surface of TS-1 covered the Lewis acid centers associated with Ti(OSi)3OH, which effectively suppressed PO isomerization, achieving a PO selectivity of 93.9%86.

Simultaneous elimination of Si-OH and Ti-OH groups

Appropriate strategies can be adopted during the TS-1 synthesis process and the Au loading process to eliminate hydroxyl groups. Adjusting the amount of added urea helps improve the TS-1 crystal structure and reduce surface defects. Infrared spectroscopy shows only a weak PO adsorption peak on TS-1, suggesting that PO molecules readily desorb and diffuse within the TS-1 crystals, achieving a PO selectivity of 93%73. Ammonia (NH3) treatment replaced hydroxyl groups with -NH2 ligands, significantly lowering the acidity of TS-187. Additionally, alkali treatment can be applied to directly neutralize acidic sites on Au/TS-188. Immersing Au/TS-1 in Rb2CO3 or Cs2CO3 solutions followed by ultrasonic dispersion effectively reduced both the acidity strength and density on the catalyst surface89. As the density of hydroxyl groups on the TS-1 surface decreased, the desorption of PO became more favorable, effectively alleviating the occurrence of ring-opening reactions. Furthermore, the elimination of hydroxyl groups was achieved by adjusting the activation atmosphere of the Au/TS-1 catalyst. Characterization results from O2-TPO-MS and 29Si NMR indicate that pre-treating the Au/TS-1 catalyst with a H2-C3H6 mixed gas atmosphere functionalized the catalyst surface, imparting hydrophobic properties that promote C3H6 adsorption and PO desorption90.

Strategies to maintain high stability

A common challenge in gas-phase C3H6 epoxidation is the poor reaction stability of the Au/TS-1 catalysts, which results in a gradual decline in the PO formation rate. The deactivation of Au/TS-1 catalysts can be categorized as follows: coverage of active sites, pore structure blockage, or loss of active sites. The narrow microporous channels of TS-1 severely restrict the diffusion of epoxidation products. Strong adsorption of PO and its isomerization products on active sites will lead to coverage of catalytic active centers for the main reaction, thereby causing catalyst deactivation. Further deposition and transformation of PO into polyolefins, hard coke, and refractory aromatic species will block TS-1 micropores (Fig. 6a), as indicated by the characteristic peaks in the derivative TG curves at about 460 °C and 640 °C, accelerating catalyst deactivation91,92,93,94. Au aggregation leads to the loss of active sites (Fig. 6b). Under high temperatures or in the presence of gas-phase reactants, Au may migrate and aggregate into larger particles, which reduces the number of active sites responsible for HOOH generation, gradually decreasing the catalytic activity. Based on the above main deactivation mechanisms, corresponding inhibition strategies should be discussed.

Preventing coking

Coking-induced catalyst deactivation is closely related to side reactions occurring during the reaction process. Increasing PO selectivity can significantly suppress catalyst deactivation. For example, modifying the pore structure of the TS-1 support can improve mass transport properties. Hierarchical pore structures are considered effective in enhancing intracrystalline diffusion within TS-1. The development of TS-1 with micro-mesoporous hierarchical structures has emerged as a promising strategy to inhibit rapid catalyst deactivation, as depicted in Fig. 6c. Through a combined treatment involving NH3 and organic bases, mesopores with diameters ranging from 4.1 nm to 19.5 nm can be created within TS-1 crystals. As the mesopore diameter increases, the mass transport ability of TS-1 improves, thereby alleviating coking. Notably, the carbon content of the catalyst decreases from 5.65% to 1.94%95. Furthermore, constructing a mesoporous structure within the TS-1 crystal through “resolution-crystallization” results in a PO selectivity of 97% and extends the catalyst lifespan to 100 h96,97. Although the microporous structure maintains the PO generation efficiency, the introduced mesopore channels enhance the mass transport of product molecules. This alteration effectively mitigates the pore blockage caused by carbon deposition. Moreover, spray drying a mixture of TS-1 crystals and their mother liquor produces TS-1 microspheres with numerous intercrystalline mesopores. Weight-based measurements suggest that the diffusion coefficient of C3H6 within these microspheres is twice that observed in conventional TS-1 zeolites65. The total carbon weight (0.99 wt%) of Au/TS-1/S-1 catalyst is significantly lower than that of the Au/TS-1 catalyst (4.9 wt%) after the gas-phase C3H6 epoxidation reaction98. This reduction is attributed to the shorter diffusion distances within the TS-1 core−shell structure, which facilitate PO diffusion and inhibit coke formation, enabling stable reactions for up to 100 h. Modifying the pore structure of TS-1 serves two main purposes. On the one hand, it promotes the rapid diffusion of PO through the TS-1 crystals, preventing side reactions and avoiding coke formation at the source. On the other hand, even if minor coke formation occurs, the presence of abundant pore space ensures that the diffusion channels remain accessible, extending the catalyst’s lifespan. Additionally, reducing the number of hydroxyl groups on the catalyst surface can suppress PO side reactions can also improve reaction stability. For example, covering the acid sites on the TS-1 surface with a SiO2 shell enables stable performance for up to 120 h86, whereas the use of silane agents to eliminate Si-OH groups extends the catalyst lifespan to 200 h.

Catalysts deactivated due to coking are typically regenerated using thermal methods (Fig. 6d). The catalyst is reactivated through oxidation, causing the deposited carbon species to react with O2 to form CO2, which is subsequently released from the pores. For example, deactivated Au/TS-1 treated in an atmosphere containing 5 vol.% O2 in N2 at 250 °C for 0.5 h exhibited a relatively stable PO formation rate over the following 50 h, although deactivation persisted afterward73. Furthermore, periodic regeneration of the Au/TS-1 catalyst every 5 h under 10 vol.% O2/He at 300 °C for 1 h maintained PO selectivity close to its initial value, despite a gradual decline in H2 efficiency over time99.

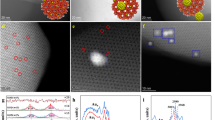

Preventing Au aggregation

It is difficult to redisperse nano-Au once it aggregates into high-activity catalytic sites. Therefore, obtaining highly dispersed and small-sized Au during the preparation process is crucial. One approach involves modifying the TS-1 support to improve the Au loading efficiency and uniformity. For example, freeze-drying can remove bound water from the TS-1 synthesis, preventing particle agglomeration and ensuring dispersion. This process facilitates uniform adsorption of Au precursor species, potentially leading to subnano Au100. Additionally, incorporating vanadium atoms into the TS-1 framework has been shown to reduce the average Au particle size and improve dispersion, thereby enhancing PO generation at low H2 concentrations101. Alternatively, special functional groups can be utilized to anchor Au and prevent its migration and aggregation. For example, Na3Au(S2O3)2 contains sulfur species that act as protective ligands, promoting the formation of highly dispersed Au particles (~2.8 nm) that remain stable for 42 h during the catalytic reaction43. In addition, the NH3 derived from ammonium salts used as a precipitant can replace Cl− or OH− ligands to strengthen the electrostatic interactions between the Au precursor and the TS-1 support (Fig. 6e). This method enables the preparation of atomically dispersed Au particles (<1 nm)7, achieving a C3H6 conversion of 14.3% and maintaining catalytic stability for more than 100 h102. Furthermore, the use of Cs2CO3 to promote the hydrolysis of HAuCl4 reduces the Cl content in [AuClx(OH)4-x] complexes on TS-1, resulting in a narrower Au particle size distribution. Au particles in the range of 0.5 − 1 nm and single-atom Au species can be observed, achieving a C3H6 conversion of 10% and a stability exceeding 130 h103. Similarly, complete hydrolysis of AuCl4− the use of NaOH to form [Au(OH)4]− results in a significant C3H6 conversion of 12%. Additionally, the basic environment induces defect sites on the TS-1 support, which promote strong Au anchoring and prevent sintering104,105.

Research has indicated that certain functional groups introduced by biomass can inhibit Au aggregation (Fig. 6f). The introduction of -COOH groups onto the Au surface using biomass extracts has been found to prevent aggregation during high-temperature calcination11. The use of biomass extracts for the in situ reduction of Au allows the residual biomass on the catalyst surface to suppress Au agglomeration, resulting in a C3H6 conversion of 14.5% and sustained catalytic stability for up to 850 h85. Additionally, incorporating other metals into the catalyst matrix can enhance the stability of the Au active sites. For example, subnano Au−Zr bimetallic clusters synthesized via the co-precipitation method and supported on TS-1 exhibited strong Au−Zr interactions, which stabilized Au in its subnano form and achieved a C3H6 conversion of 14.06%, with a stable performance maintained for 51 h49.

Conclusion and perspective

Numerous fine chemicals derived from PO are widely used in the pharmaceutical, personal care, and textile industries. PO serves as a vital organic chemical raw material, playing a critical role in both the national economy and public well-being. Direct C3H6 epoxidation using H2 and O2 has emerged as a promising alternative, offering advantages such as environmental friendliness, high efficiency, and operational flexibility. Over the past two decades, considerable attention has been given to the Au−Ti catalytic system, particularly the Au/TS-1 catalyst, in response to the limited performance of the gas-phase C3H6 epoxidation. Various strategies have been employed for structural regulation and surface modification, achieving initial catalytic performance with C3H6 conversion exceeding 10% and PO selectivity of over 90%. However, the C3H6 conversion rate and PO selectivity still cannot be simultaneously improved, and the catalyst lifespan has not yet surpassed 1000 h. Even when side reactions are suppressed to achieve a PO selectivity of 95% and reduce coking, both C3H6 conversion and PO selectivity gradually decrease, failing to maintain the initial performance.

Shortening the PO diffusion pathway or introducing mesopores within the TS-1 crystal can increase the PO mass transfer rate, thereby suppressing side reactions. However, reactants such as C3H6 may also rapidly diffuse through catalyst channels with weak adsorption to the abundant active sites in the bulk phase, leading to lower C3H6 conversion rates. The selectivity for PO can also be improved by removing Ti-OH and Si-OH groups from the catalyst surface, which is achieved through acid-base neutralization or active site coverage. Nevertheless, since Ti-OH simultaneously serves as crucial active sites for the main catalytic reaction, covering these Ti active sites would inevitably lead to a decrease in reaction activity.

To address these critical issues, further clarification of the acidic sites responsible for catalyzing PO isomerization reactions is essential. Notably, Ti-OH can simultaneously catalyze both primary and side reactions. Therefore, it is crucial to investigate techniques for suppressing side reactions by eliminating hydroxyl groups while retaining the catalytic capability of tetra-coordinated Ti, which remains a central focus for future research. Furthermore, given the propensity of Au/TS-1 catalysts to deactivate, exploring regeneration processes has become an urgent priority. Additionally, due to the safety risks posed by unstable catalytic performance, such as explosion hazards arising from the mixing of raw material gases and the transportation of reaction gases, thoroughly addressing these challenges is crucial. In conclusion, advancing research in these areas will facilitate the transition of the technology from small-scale testing to pilot-scale implementation and, ultimately, toward industrial application.

References

Herzberger, J. et al. Polymerization of ethylene oxide, propylene oxide, and other alkylene oxides: Synthesis, novel polymer architectures, and bioconjugation. Chem. Rev. 116, 2170–2243 (2016).

Luinstra, G. A. Poly (propylene carbonate), old copolymers of propylene oxide and carbon dioxide with new interests: Catalysis and material properties. Polym. Rev. 48, 192–219 (2008).

Ghanta, M., Fahey, D. R., Busch, D. H. & Subramaniam, B. Comparative economic and environmental assessments of H2O2-based and tertiary butyl hydroperoxide-based propylene oxide technologies. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 1, 268–277 (2013).

Lin, M., Xia, C., Zhu, B., Li, H. & Shu, X. Green and efficient epoxidation of propylene with hydrogen peroxide (HPPO process) catalyzed by hollow TS-1 zeolite: A 1.0 kt/a pilot-scale study. Chem. Eng. J. 295, 370–375 (2016).

Hayashi, T., Tanaka, K. & Haruta, M. Selective vapor-phase epoxidation of propylene over Au/TiO2 catalysts in the presence of oxygen and hydrogen. J. Catal. 178, 566–575 (1998).

Chowdhury, B. et al. In situ UV-vis and EPR study on the formation of hydroperoxide species during direct gas phase propylene epoxidation over Au/Ti-SiO2 catalyst. J. Phy. Chem. B. 110, 22995–22999 (2006).

Kanungo, S., Perez Ferrandez, D. M., d’Angelo, F. N., Schouten, J. C. & Nijhuis, T. A. Kinetic study of propene oxide and water formation in hydro-epoxidation of propene on Au/Ti-SiO2 catalyst. J. Catal. 338, 284–294 (2016).

Chen, X. Y., Chen, S. L., Jia, A. P., Lu, J. Q. & Huang, W. X. Gas phase propylene epoxidation over Au supported on titanosilicates with different Ti chemical environments. Appl. Surf. Sci. 393, 11–22 (2017).

Shi, S. et al. Synergizing tetra-coordinated Ti sites anchored onto micropore-free silica with Au sites to boost propylene hydro-oxidation. Chem. Eng. J. 491, 151732–151741 (2024).

Shi, S., Du, W., Zhang, Z., Duan, X. & Zhou, X. Modulating Ti coordination environment in Ti-containing materials by sulfation for synergizing with Au sites to facilitate propylene epoxidation. Chem. Engin. J. 500, 156364 (2024).

Yao, S. et al. Activity and stability of titanosilicate supported Au catalyst for propylene epoxidation with H2 and O2. Mol. Cata. 448, 144–152 (2018).

Uphade, B. S., Yamada, Y., Akita, T., Nakamura, T. & Haruta, M. Synthesis and characterization of Ti-MCM-41 and vapor-phase epoxidation of propylene using H2 and O2 over Au/Ti-MCM-41. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 215, 137–148 (2001).

Lee, W. S., Cem Akatay, M., Stach, E. A., Ribeiro, F. H. & Nicholas Delgass, W. Reproducible preparation of Au/TS-1 with high reaction rate for gas phase epoxidation of propylene. J. Catal. 287, 178–189 (2012).

Stangland, E. E., Taylor, B., Andres, R. P. & Delgass, W. N. Direct vapor phase propylene epoxidation over deposition-precipitation gold-titania catalysts in the Presence of H2/O2: Effects of support, neutralizing agent, and pretreatment. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 2321–2330 (2005).

Li, W. et al. Highly efficient epoxidation of propylene with in situ-generated H2O2 over a hierarchical TS-1 zeolite-supported non-noble nickel catalyst. ACS Catal. 13, 10487–10499 (2023).

Cumaranatunge, L. & Delgass, W. N. Enhancement of Au capture efficiency and activity of Au/TS-1 catalysts for propylene epoxidation. J. Catal. 232, 38–42 (2005).

Zheng, J. et al. Uncalcined TS-1 supported Au catalyst via NaBH4 reduction method for propylene epoxidation: Insights into the H2 pretreatment effect on catalytic performance. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 670, 119555 (2024).

Du, M., Huang, J., Sun, D. & Li, Q. Propylene epoxidation over biogenic Au/TS-1 catalysts by cinnamomum camphora extract in the presence of H2 and O2. Appl. Surf. Sci. 366, 292–298 (2016).

Huang, J. et al. Propene epoxidation with dioxygen catalyzed by gold clusters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 7862–7866 (2009).

Turner, C. H., Ji, J., Lu, Z. & Lei, Y. Analysis of the propylene epoxidation mechanism on supported gold nanoparticles. Chem. Eng. Sci. 174, 229–237 (2017).

Joshi, A. M., Delgass, W. N. & Thomson, K. T. Mechanistic implications of Aun/Ti-lattice proximity for propylene epoxidation. J. Phys. Chem. C. 111, 7841–7844 (2007).

Harris, J. W., Arvay, J., Mitchell, G., Delgass, W. N. & Ribeiro, F. H. Propylene oxide inhibits propylene epoxidation over Au/TS-1. J. Catal. 365, 105–114 (2018).

Taylor, B., Lauterbach, J., Blau, G. E. & Delgass, W. N. Reaction kinetic analysis of the gas-phase epoxidation of propylene over Au/TS-1. J. Catal. 242, 142–152 (2006).

Arvay, J. W. et al. Kinetics of propylene epoxidation over extracrystalline gold active sites on Au/TS-1 catalysts. ACS Catal. 12, 10147–10160 (2022).

Feng, X., Chen, D. & Zhou, X. G. Thermal stability of TPA template and size-dependent selectivity of uncalcined TS-1 supported Au catalyst for propene epoxidation with H2 and O2. RSC Adv. 6, 44050–44056 (2016).

Du, W. et al. Kinetic insights into the tandem and simultaneous mechanisms of propylene epoxidation by H2 and O2 on Au-Ti Catalysts. ACS Catal. 13, 2069–2085 (2023).

Li, Z., Zhang, J., Wang, D., Ma, W. & Zhong, Q. Confirmation of gold active sites on titanium silicalite-1 supported nano-gold catalysts for gas-phase epoxidation of propylene. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 25215–25222 (2017).

Chen, J. et al. Enhancement of catalyst performance in the direct propene epoxidation: A Study into gold-titanium synergy. ChemCatChem 5, 467–478 (2013).

Li, Z., Wang, Y., Zhang, J., Wang, D. & Ma, W. Better performance for gas-phase epoxidation of propylene using H2 and O2 at lower temperature over Au/TS-1 catalyst. Catal. Commun. 90, 87–90 (2017).

Lu, J., Zhang, X., Bravo-Suarez, J. J., Fujitani, T. & Oyama, S. T. Effect of composition and promoters in Au/TS-1 catalysts for direct propylene epoxidation using H2 and O2. Catal. Today 147, 186–195 (2009).

Lu, X., Zhao, G. & Lu, Y. Propylene epoxidation with O2 and H2: A high-performance Au/TS-1 catalyst prepared via a deposition-precipitation method using urea. Catal. Sci. Technol. 3, 2906–2909 (2013).

Li, N. et al. TS-1 supported highly dispersed sub-5 nm gold nanoparticles toward direct propylene epoxidation using H2 and O2. J. Solid State Chem. 261, 92–102 (2018).

Li, Z., Chen, X., Ma, W. & Zhong, Q. Effect of TS-1 crystal planes on the catalytic activity of Au/TS-1 for direct propylene epoxidation with H2 and O2. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 8, 8496–8504 (2020).

Zhang, Z., Xu, K., Cao, Y., Duan, X. & Zhou, X. Modified impregnation combined with thermal treatment to boost Au-Ti catalytic hydro-oxidation of propylene. Chem. Eng. Sci. 305, 121184–121194 (2025).

Zhang, Z. et al. Differences in catalytic sites for selective oxidation of propane and direct propene epoxidation using H2 and O2 on Au/TS-1 catalysts. Chem. Eng. J. 508, 160977–160990 (2025).

Lin, D. et al. Reversing titanium oligomers formation towards high-efficiency and green synthesis of titanium-containing molecular sieves. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 3443–3448 (2021).

Liao, Y. et al. Tailoring titanium species to boost bifunctional Au-TS-1 catalyzing propylene hydro-oxidation. AIChE J. 71, e18820 (2025).

Su, Z., Gao, L., Gao, J. & Ma, W. Effect of nickel promoter in Au/TS‑1 catalysts for gas‑phase propylene epoxidation. J. Porous Mat. 29, 143–152 (2022).

Xu, J. et al. Phosphate-modified effects on uncalcined TS-1-Immobilized Au catalysts for propylene epoxidation with H2 and O2. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 62, 21654–21665 (2023).

Huang, J., Takei, T., Ohashi, H. & Haruta, M. Propene epoxidation with oxygen over gold clusters: Role of basic salts and hydroxides of alkalis. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 435–436, 115–122 (2012).

Feng, X. et al. Enhanced catalytic performance for propene epoxidation with H2 and O2 over bimetallic Au-Ag/uncalcined TS-1 catalysts. ACS Catal. 8, 7799–7808 (2018).

Lin, D. et al. Enhancing the dynamic electron transfer of Au species on wormhole-like TS-1 for boosting propene epoxidation performance with H2 and O2. Green. Energy Environ. 5, 433–443 (2020).

Zhang, Z. et al. Engineering gold impregnated uncalcined TS-1 to boost catalytic formation of propylene oxide. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 319, 121837 (2022).

Wang, G. et al. Combining trace Pt with surface silylation to boost Au/uncalcined TS-1 catalyzed propylene epoxidation with H2 and O2. AIChE J. 68, e17416 (2022).

Li, Z., Gao, L., Ma, W. & Zhong, Q. Higher gold atom efficiency over Au-Pd/TS-1 alloy catalysts for the direct propylene epoxidation with H2 and O2. Appl. Surf. Sci. 497, 143749 (2019).

Lee, W., Akatay, M. C., Stach, E. A., Ribeiro, F. H. & Delgass, W. N. Gas-phase epoxidation of propylene in the presence of H2 and O2 over small gold ensembles in uncalcined TS-1. J. Catal. 313, 104–112 (2014).

Ayvalı, T. et al. Mononuclear gold species anchored on TS-1 framework as catalyst precursor for selective epoxidation of propylene. J. Catal. 367, 229–233 (2018).

Taylor, B., Lauterbach, J. & Delgass, W. N. Gas-phase epoxidation of propylene over small gold ensembles on TS-1. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 291, 188–198 (2005).

Lee, W. et al. Probing the gold active sites in Au/TS-1 for gas-phase epoxidation of propylene in the presence of hydrogen and oxygen. J. Catal. 296, 31–42 (2012).

Feng, X. et al. Insights into size-dependent activity and active sites of Au nanoparticles supported on TS-1 for propene epoxidation with H2 and O2. J. Catal. 317, 99–104 (2014).

Feng, X. et al. Au/TS-1 catalyst prepared by deposition-precipitation method for propene epoxidation with H2/O2: Insights into the effects of slurry aging time and Si/Ti molar ratio. J. Catal. 325, 128–135 (2015).

Song, Z. et al. Propene epoxidation with H2 and O2 on Au/TS-1 catalyst: Cost-effective synthesis of small-sized mesoporous TS-1 and its unique performance. Catal. Today 347, 102–109 (2020).

Xiang, F. et al. Manipulating gold spatial location on titanium silicalite-1 to enhance the catalytic performance for direct propene epoxidation with H2 and O2. ACS Catal. 8, 10649–10657 (2018).

Wang, Q. et al. Nanoparticles as an antidote for poisoned gold single-atom catalysts in sustainable propylene epoxidation. Nat. Commun. 15, 3249 (2024).

Sheng, N. et al. Effective regulation of the Au spatial position in a hierarchically structured Au/HTS-1 catalyst: To boost the catalytic performance of propene epoxidation with H2 and O2. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 10, 9515–9524 (2022).

Otto, T., Zhou, X., Zones, S. I. & Iglesia, E. Synthesis, characterization, and function of Au nanoparticles within TS-1 zeotypes as catalysts for alkene epoxidation using O2/H2O reactants. J. Catal. 410, 206–220 (2022).

Wang, L. et al. Tannic acid assisted construction of Au-Ti integrated catalyst regulating the local environment of framework Ti toward propylene epoxidation under H2/O2. Mol. Catal. 545, 113206 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. Titanium silicalite-1 zeolite encapsulating Au particles as a catalyst for vapor phase propylene epoxidation with H2/O2: A matter of Au-Ti synergic interaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 4428–4436 (2020).

Sun, S. et al. Defect engineering of black TS-1 for anchoring electron-rich Au with enhanced H2 efficiency in propene epoxidation. Chem. Eng. J. 504, 158931–158941 (2025).

Li, Z., Su, Z., Ma, W. & Zhong, Q. Competition of propylene hydrogenation and epoxidation over Au-Pd/TS-1 bimetallic catalysts for gas-phase epoxidation of propylene with O2 and H2. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 615, 118060 (2021).

Gaudet, J. et al. Effect of gold oxidation state on the epoxidation and hydrogenation of propylene on Au/TS-1. J. Catal. 280, 40–49 (2011).

Haruta, M., Uphade, B. S., Tsubota, S. & Miyamoto, A. Selective oxidation of propylene over gold deposited on titanium-based oxides. Res. Chem. Intermed. 24, 329–336 (1998).

Caixia, Q. et al. Switching of reactions between hydrogenation and epoxidation of propene over Au/Ti-based oxides in the presence of H2 and O2. J. Catal. 281, 12–20 (2011).

Bukowski, B. C., Delgass, W. N. & Greeley, J. Gold stability and diffusion in the Au/TS-1 catalyst. J. Phys. Chem. C. 125, 4519–4531 (2021).

Hou, L., Yan, S., Liu, L., Liu, J. & Xiong, G. Fabrication of gold nanoparticles supported on hollow microsphere of nanosized TS-1 for the epoxidation of propylene with H2 and O2. Chem. Eng. J. 481, 148676 (2024).

Du, W., Zhang, Z., Song, N., Duan, X. & Zhou, X. Kinetics and mechanism of propylene hydro-oxidation to acrolein on Au catalysts. Nano Res. 17, 354–363 (2024).

Lin, B. et al. Mechanistic insights into propylene oxidation to acrolein over gold catalysts. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 57, 39–49 (2023).

Ji, J., Lu, Z., Lei, Y. & Turner, C. H. Mechanistic insights into the direct propylene epoxidation using Au nanoparticles dispersed on TiO2/SiO2. Chem. Eng. Sci. 191, 169–182 (2018).

Du, W. et al. Kinetic insights into reaction pathways of acrolein formation in propylene epoxidation by H2 and O2 over Au/TS-1 catalyst. Chem. Eng. J. 487, 150512 (2024).

Li, Z., Ma, W. & Zhong, Q. Effect of core-shell support on Au/S-1/TS‑1 for direct propylene epoxidation and design of catalyst with higher activity. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 58, 4010–4016 (2019).

Ping, C., Lin, M., Guo, Q. & Ma, W. The competition between propylene epoxidation and hydrogen oxidation and the effect of water on Au/TS-1/MOx catalysts. Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 368, 113034 (2024).

Shi, S. et al. Tailoring the microenvironment of Ti sites in Ti-containing materials for synergizing with Au sites to boost propylene. Chin. J. Catal. 63, 133–143 (2024).

Xu, J. et al. Au/TS-1 catalyst for propylene epoxidation with H2 and O2: Effect of surface property and morphology of TS-1 zeolite. Nano Res. 16, 6278–6289 (2023).

Xu, J. et al. Zeolite crystal size effects of Au/uncalcined TS-1 bifunctional catalysts on direct propylene epoxidation with H2 and O2. Chem. Eng. Sci. 227, 115907 (2020).

Ping, C., Zhu, Q., Ma, W., Hu, C. & Zhang, Y. Effect of urea on the morphology of TS-1 and catalytic performance of Au/TS-1 for direct gas phase epoxidation of propylene. J. Porous Mat. 29, 1919–1928 (2022).

Ping, C., Lin, M., Guo, Q. & Ma, W. Coating hollow silicalite-1 with TS-1 shell as support of Au: Preparation and enhanced catalytic stability for direct propylene epoxidation. Res. Chem. Intermediat. 50, 1–15 (2024).

Yuan, J. et al. Mesoporogen-free strategyto construct hierarchical TS‑1 in a highly concentrated system for gas-phase propene epoxidation with H2 and O2. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 26134–26142 (2021).

Zhu, Q., Liang, M., Yan, W. & Ma, W. Effective hierarchization of TS-1 and its catalytic performance in propene epoxidation. Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 278, 307–313 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. TS-1 with abundant micropore channel-supported Au catalysts toward improved performance in gas-phase epoxidation of propylene. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 11, 7042–7052 (2023).

Kanungo, S. et al. Silylation enhances the performance of Au/Ti-SiO2 catalysts in direct epoxidation of propene using H2 and O2. J. Catal. 344, 434–444 (2016).

Kanungo, S. et al. Direct epoxidation of propene on silylated Au-Ti catalysts: A study on silylation procedures and the effect on propane formation. Catal. Sci. Technol. 8, 3052 (2018).

Ren, Y. et al. Dual-component sodium and cesium promoters for Au/TS-1: Enhancement of propene epoxidation with hydrogen and oxygen. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59, 8155–8163 (2020).

Wang, G. et al. Mechanism-guided elaboration of ternary Au-Ti-Si sites to boost propylene oxide formation. Chem. Catal. 1, 1–11 (2021).

Aly, M. & Saeys, M. Selective silylation boosts propylene epoxidation with H2 and O2 over Au/TS-1. Chem. Catal. 1, 761–762 (2021).

de Boed, E. J. J., de Rijk, J. W., de Jongh, P. E. & Donoeva, B. Steering the selectivity in gold-titanium catalyzed propene oxidation by controlling the surface acidity. J. Phys. Chem. C. 125, 16557–16568 (2021).

Song, Z. et al. Engineering three-layer core-shell S-1/TS-1@dendritic-SiO2 supported Au catalysts towards improved performance for propene epoxidation with H2 and O2. Green. Energy Environ. 5, 473–483 (2020).

Yuan, T., Zhu, Q., Gao, L., Gao, J. & Ma, W. The nitriding of titanium silicate-1 and its effect on gas phase epoxidation of propylene. J. Mater. Sci. 55, 3803–3811 (2020).

Zhao, C. et al. Enhanced catalytic performance for gas phase epoxidation of propylene with H2 and O2 by multiple pretreated Au/TS-1 catalysts. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 685, 119895 (2024).

Fu, J. S. et al. Enhancement of the activity and stability of Au/TS-1 catalyst in the gas-phase epoxidation of propene through alkali carbonate modification. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 48, 1256–1262 (2020).

Ren, Y. et al. Dual-component gas pretreatment for Au/TS-1: Enhanced propylene epoxidation with oxygen and hydrogen. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 584, 117172 (2019).

Feng, X. et al. Au nanoparticles deposited on the external surfaces of TS-1: Enhanced stability and activity for direct propylene epoxidation with H2 and O2. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 150-151, 396–401 (2014).

Feng, X., Lin, D., Chen, D. & Yang, C. Rationally constructed Ti sites of TS-1 for epoxidation reactions. Sci. Bull. 66, 1945–1949 (2021).

Feng, X. et al. Simultaneously enhanced stability and selectivity for propene epoxidation with H2 and O2 on Au catalyst supported on nano-crystalline mesoporous TS-1. ACS Catal. 7, 2668–2675 (2017).

Feng, X., Liu, Y., Li, Y. & Yang, C. Au/TS-1 catalyst for propene epoxidation with H2/O2: A novel strategy to enhance stability by tuning charging sequence. AIChE J. 62, 3963–3972 (2016).

Sheng, N. et al. Intracrystalline diffusion regulation of Au/hierarchical TS-1 for simultaneously enhanced stability and selectivity in propene epoxidation with H2 and O2. Chem. Eng. Sci. 300, 120538 (2024).

Lin, M., Su, Z. & Ma, W. Effect on the introduction of hollow structure on Au/TS-1 to improve the stability for propylene epoxidation. Chem. Phys. 581, 112259 (2024).

Sheng, N. et al. Enhanced stability for propene epoxidation with H2 and O2 over wormhole like hierarchical TS-1 supported Au nanocatalyst. Chem. Eng. J. 377, 119954 (2019).

Song, Z. et al. Cost-efficient core-shell TS-1/silicalite-1 supported Au catalysts: Towards enhanced stability for propene epoxidation with H2 and O2. Chem. Eng. J. 377, 119927 (2019).

Kapil, N. et al. Precisely engineered supported gold clusters as a stable catalyst for propylene epoxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 18185–18193 (2021).

Guo, Y., Zhang, Z., Xu, J., Duan, X. & Zhou, X. Suppression of TS-1 aggregation by freeze-drying to enhance Au dispersion for propylene epoxidation using H2 and O2. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 62, 8654–8664 (2023).

Qi, C. et al. Efficient formation of propylene oxide under low hydrogen concentration in propylene epoxidation over Au nanoparticles supported on V-doped TS-1. J. Catal. 436, 115608 (2024).

Peng, J. et al. Synthesis strategy of atomically dispersed Au clusters induced by NH3 on TS-1: Significantly improve the epoxidation activity of propylene. Chem. Eng. J. 472, 144895 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. A novel and simple method yields highly dispersed Au/TS-1 catalysts for enhanced propylene hydro-oxidation. Chem. Commun. 60, 7737 (2024).

Lu, Z. et al. Gold catalysts synthesized using a modified incipient wetness impregnation method for propylene epoxidation. Chem. Cat. Chem. 12, 5993–5999 (2020).

Huang, J., Takei, T., Akita, T., Ohashi, H. & Haruta, M. Gold clusters supported on alkaline treated TS-1 for highly efficient propene epoxidation with O2 and H2. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 95, 430–438 (2010).

Liu, C., Guan, Y., Hensen, E. J. M., Lee, J. & Yang, C. Au/TiO2@SBA-15 nanocomposites as catalysts for direct propylene epoxidation with O2 and H2 mixtures. J. Catal. 282, 94–102 (2011).

Sacaliuc, E., Beale, A. M., Weckhuysen, B. M. & Nijhuis, T. A. Propene epoxidation over Au/Ti-SBA-15 catalysts. J. Catal. 248, 235–248 (2007).

Lu, J. et al. Direct propylene epoxidation over barium-promoted Au/Ti-TUD catalysts with H2 and O2: Effect of Au particle size. J. Catal. 250, 350–359 (2007).

Uphade, B. S., Akita, T., Nakamura, T. & Haruta, M. Vapor-phase epoxidation of propene using H2 and O2 over Au/Ti-MCM-48. J. Catal. 209, 331–340 (2002).

Zhang, Z. et al. Uncalcined TS-2 immobilized Au nanoparticles as a bifunctional catalyst to boost direct propylene epoxidation with H2 and O2. AIChE J. 66, e16815 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Effect of TiO2 on catalytic performance of gold-titanium-catalyzed gas-phase epoxidation of propylene. Mol. Catal. 560, 114095–114103 (2024).

Lian, T. et al. The influence of active biomolecules in plant extracts on the performance of Au/TS-1 catalysts in propylene epoxidation. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 23, 2853–2859 (2019).

Hong, Y. L., Huang, J. L., Zhan, G. W. & Li, Q. B. Biomass-modified Au/TS-1 as highly efficient and stable nanocatalysts for propene epoxidation with O2 and H2. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 58, 21953–21960 (2019).

Dong, T. et al. Propylene epoxidation over Au/TS-1 modified by ammonium salt: Enhancement of the attractiveness of gold precursors and supports. Chem. Phys. Lett. 804, 139880 (2022).

Peng, J. et al. Atomically dispersed nano Au clusters stabilized by Zr on the TS-1 surface: Significant enhancement of catalytic oxidation ability using H2 and O2. Appl. Surf. Sci. 619, 156733 (2023).

Hou, L., Liu, L., Liu, J. & Xiong, G. Low concentration template preparation of microsized Au/TS-1 as an efficient catalyst for gas-phase propylene epoxidation with H2 and O2. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 12, 10164–10174 (2024).

Zhao, C. et al. Alkaline-Assisted excessive impregnation for enhancing Au nanoparticle loading on the TS-1 zeolite. LANGMUIR 41, 804–810 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22578518, 22278452, 22208383).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. wrote the manuscript. Y.T., Y.L., H.Z. and M.L. assisted in writing the manuscript. B.S., W.X., and Z.Y. conceived the framework of the manuscript. C.Z. revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Tian, Y., Li, Y. et al. Reaction limitations and modification strategies of Au-Ti catalysts for gas-phase propylene epoxidation. Commun Chem 8, 341 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01721-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01721-w