Abstract

Extended covalent compounds that contain gold are virtually unknown because Au prefers metallic or molecular coordination. Using crystal structure search combined with first-principles calculations at high pressure, we have identified a family of ternary compounds, M2AuB6 (M = Na, K, Mg, Ca, and Sr), featuring Au-B covalent frameworks that satisfy a simple “push-pull” design rule: strongly electropositive cations donate charge that anchors Au in electron-deficient B6 octahedra, thereby stabilizing Au–B σ bonds through Au dsp2 hybridization. The low enthalpy phases, Na2AuB6 and K2AuB6, exhibit superconductivity, with Au-6px/6py and B-2p states contributing to Cooper pair formation, facilitated by low- and medium-frequency phonons arising from Au−B bond stretching. These pressure-induced structures and bonding configurations can be quenched to ambient pressure, demonstrating an effective approach to bypassing traditional electronegativity constraints. We propose M2AuB6 compounds as realistic and chemically unique platforms for exploring gold-based superconductivity and for testing electron-donor-guided materials discovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chemical bonding is intertwined with the stability, properties, and behavior of matter, serving as the essential link between atomic interactions and macroscopic functionalities1,2,3,4,5. Emerging bonding paradigms—such as multi-center bonds6,7, high-pressure-stabilized bonds8,9,10, and bonds influenced by relativistic effects11,12—challenge traditional theories and offer valuable insights into unconventional interactions. These mechanisms have led to the discovery of materials with extraordinary properties, such as high-temperature superconductivity13,14,15 and ultra-hardness16,17,18. Yet, one conspicuous gap remains: extended covalent frameworks that incorporate gold.

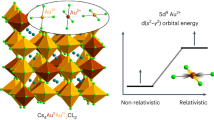

Gold, known for its strong relativistic effects, exhibits distinctive physical and chemical properties in both elemental and compound forms19,20,21,22,23. Its relativistic effects induce contraction of the 6 s orbital alongside slight radial expansion and energetic stabilization of the 5 d orbitals, endowing gold with unique bonding configurations11,24, rich oxidation states (ranging from −3 to +6)25,26,27, and unusual aurophilic interactions28,29. These properties place gold at the forefront of studies exploring unconventional bonding and electronic properties, making it a key element in materials science30,31,32,33.

Boron, on the other hand, stands out as an electron-deficient element with an unparalleled ability to form diverse multi-center bonds, fundamentally broadening our understanding of chemical bonding34,35,36,37,38. Boron-based compounds exhibit exceptional properties, including high chemical stability, exceptional mechanical strength39,40,41, large nonlinear optical response42,43,44, and high conductivity45,46,47, with some even displaying superconductivity48,49,50. For instance, MgB2, a prototypical boride superconductor with the highest transition temperature (Tc = 39 K) among ambient-pressure conventional superconductors, features two superconducting gaps—one associated with strong-coupling σ bands and the other with weaker π bands50,51. These unique features arise not solely from boron itself but from its interplay with the crystal structure, electronic configuration, and interatomic interactions in the compounds. Nonetheless, the presence of boron contributes significantly to enabling such functionalities through its versatile bonding characteristics and electronic richness.

In molecular chemistry these features enable the formation of isolated Au–B covalent bonds stabilized by bulky ligands or cluster confinement52,53,54. Translating such bonds into an infinite solid, however, has remained elusive. Although an early report described an AlB2-type AuB2 phase55, subsequent analyses indicate that the Au–B interactions in this structure are predominantly ionic rather than covalent56,57. The comparable electronegativities58,59 of Au and B (as exemplified by the Au-H system60), hinder the formation of strongly polar Au–B covalency, and the enthalpic contribution to the free energy disfavors binary Au-B compound formation. Thus far, no crystallographically authenticated bulk phase exhibiting an extended Au–B covalent framework has yet been established, leaving both the geometry and electronic consequences of Au–B covalency in extended solids unexplored.

To overcome this intrinsic thermodynamic barrier, we propose a strategy inspired by “push–pull” principle61, previously demonstrated to effectively redistribute charge and stabilize unconventional materials in multicomponent systems62,63,64. In this framework, strongly electropositive calcium element is introduced to modulate the electron distribution within the Au-B system. Calcium atoms act as electron donors, effectively pushing electrons toward the electron-deficient boron sublattice, while simultaneously pulling electron density into the Au-centered orbitals. This dual modulation results in the accumulation of charge density on Au atoms, thereby promoting orbital interactions and enhancing the covalent character of the Au–B bonds. When further combined with pressure tuning, this approach enables precise control over energy-level alignment and bonding configurations, providing a powerful means to stabilize Au–B interactions in boron-rich compounds.

Using this strategy and first-principles calculations, we predict a metastable metallic phase, Ca2AuB6, at 50 GPa. This compound features four-coordinate Au−B bonds stabilized by dsp2 hybridization of Au. Remarkably, this bonding configuration remains stable in related compounds, such as Na2AuB6 and K2AuB6, which exhibit metallized Au−B σ-bonds and are predicted to be superconductors at ambient pressure. Our findings not only fill the gap in Au-B chemistry, but also provide transformative insights into the role of Au−B bonds in stabilizing structures and driving superconductivity.

Results and discussion

Structure and stability

Pressure is widely recognized as a powerful tool for stabilizing distinct structures with unique bonding behaviors and intriguing properties65,66,67,68,69,70. Based on extensive structure searches, including the AuB2 phase, our constructed convex hull for the Au-B system reveals that even at pressures up to 300 GPa, no stable binary Au-B compounds emerge due to their large positive formation enthalpies (Supplementary Fig. S1). This indicates that pressure alone cannot compensate for the electronegativity difference between Au and B to stabilize binary Au-B compounds. Interestingly, upon incorporating Ca into this system, a metastable phase, Ca2AuB6, was identified, lying only 68 meV/atom above the convex hull relative to its most stable decomposition products in the Ca-Au-B system at 50 GPa (Fig. 1a). This value falls within the range of many synthesized metastable materials71,72,73,74. Phonon dispersion calculations from 0 to 50 GPa revealed no imaginary frequencies across the Brillouin zone (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. S2), confirming its dynamical stability and the potential for quenching to ambient pressure. To be noted, the Ca-Au-B ternary phase diagram also includes several other metastable phases (Supplementary Fig. S3) featuring discrete Au and B structural motifs, along with the stable Ca-Au compounds (e.g., CaAu3, Ca2Au3, CaAu, Ca3Au2, Ca2Au and Ca3Au, Supplementary Fig. S4), which will be published in future work. Structural predictions and stability analyses used the PBE functional, validated by known pressure-induced phase transitions of Ca, Au, and B (Supplementary Fig. S5).

a Convex hull of predicted Ca-Au-B compounds relative to stable elemental solids and binary compounds at 50 GPa. Fm-3m Au, Pm-3m Ca, and γ-B28 were selected as reference elemental structure. The colored circles represent phases that may be thermodynamically stable, metastable or unstable, and the color bar denotes the magnitude of the relative formation enthalpies (ΔH) of the compounds. The AlB2-type AuB255 with a positive formation enthalpy is also plotted. b Phonon dispersion curve of Ca2AuB6 at ambient pressure. c Free energy as a function of MD time at the temperature of 2800 K for Ca2AuB6 at ambient pressure, and the inset illustrates the trajectories of the atoms within Ca2AuB6 within the 2 × 2 × 2 supercell after MD equilibration. d Predicted crystal structure of P4/mmm Ca2AuB6. The blue and golden spheres represent Ca and Au atoms, while the two inequivalent B atoms are denoted by green (B1) and magenta (B2) spheres, respectively. e Calculated ELF of Ca2AuB6 in the (001) plane. f Calculated charge density of Ca sublattice in Ca2AuB6, with an isosurface value of 0.008 e/bohr3.

Ca2AuB6 crystallizes in a tetragonal structure with P4/mmm symmetry, featuring a three-dimensional Au-B framework (Fig. 1d). At ambient pressure, the B atoms occupy two inequivalent sites: B1 at 4j (0.8216, 0.1784, 0.0000) and B2 at 2g (0.0000, 0.0000, 0.7064). These atoms form B6 octahedra, with B1 atoms positioned within the basal plane and B2 atoms located at the vertices. The Au atoms coordinate with B1 atoms from four octahedra in the ab-plane, forming a square-planar AuB4 configuration, while the B2 atoms link the octahedra along the c-axis, resulting in a robustly interwoven Au-B skeleton. The B−B bond lengths (1.73–1.80 Å) are comparable to those in α-B12 (1.77 Å)75. The Au−B bond length is 2.29 Å, slightly exceeding that in the gold boride complex (~2.19 Å)52. The Ca atoms are situated in the channels formed by the Au-B skeleton along the c-axis, forming Ca−B and Ca−Au bond of 2.66–2.78 Å and 3.28 Å, respectively. It is worth noting that P4/mmm structures have been previously reported in Au-based ternary systems, including both perovskite-type and structurally simpler compounds76,77. Taken together with its robust Au-B skeleton and favorable thermodynamic and dynamical stability, these features suggest that Ca2AuB6 may be experimentally accessible under proper conditions.

Chemical bonding analysis

We subsequently investigate the chemical bonding attributes and stability mechanism of Ca2AuB6 at ambient pressure using Bader charge analysis, electron localization functions (ELF), and solid state adaptive natural density partitioning (SSAdNDP). Significant charge transfer occurs from the Ca atoms to the Au-B framework, resulting in ionic Ca−Au and Ca−B bonds. High ELF values are observed at the center of B−B bonds (Fig. 1e), signifying strong covalent bonding. In contrast, the regions of high ELF values along the Au−B bonds are polarized towards the B atoms, indicating the presence of polar covalent interactions. The charge density of the Ca sublattice (Fig. 1f) shows significant electron accumulation in the interstitial regions near the original Au-B framework, which stabilizes the Au-B network and resembles the chemical template effect78. The SSAdNDP analysis79 identified several key bonding features: one two-center−two-electron (2c−2e) B−B σ bond, eight 3c−2e B−B σ bonds, four 2c−2e Au−B σ bonds, and four lone pair (LP) electrons of Au (Fig. 2a–d and Supplementary Fig. S6). This Ca2AuB6 structure, featuring a multicenter-bonded Au–B polyanionic anionic network with covalently bonded B6 octahedra and AuB4 units, exhibits substantial charge transfer from the Ca cations and can be classified as a polar intermetallic80,81. Temperature-dependent molecular dynamics (MD) simulations demonstrated that Ca2AuB6 maintains its structural integrity up to 2800 K (Fig. 1c and Supplementary S7), highlighting its thermal robustness. Furthermore, the compound meets the criteria for mechanical stability with a calculated Vickers hardness of 24.5 GPa (Supplementary Table S3), making it a promising candidate for applications requiring high hardness and thermal resilience.

a–d SSAdNDP analysis along with the occupation number (ON). In total 17 bonds are shown, including four two-center−two-electron (2c−2e) Au−B σ bonds, one 2c−2e B−B σ bond, eight three-center−two-electron (3c−2e) B−B σ bonds, and four lone pairs (LP) on Au. The orbital-resolved PDOS of e B1 and f Au atoms. Calculated g −COHP and h, i − pCOHP of Au−B1 interaction. Positive and negative values denote bonding and antibonding orbital interactions for COHP, respectively. j −ICOHP values between Au and B1 atom pairs. Positive −ICOHP values represent bonding states. k The schematic diagram of the formation of Au−B covalent bonds via dsp2 hybridization in Ca2AuB6, along with the anti-bonding contribution to the Au−B1 bond from the Au 5dxy states.

The square-planar AuB4 configuration provides an excellent framework to investigate the valence electron distribution and hybridization of the Au atom. Projected density of states (PDOS) analysis reveals strong hybridization below the Fermi level between Au and B1 atoms (Fig. 2e, f and Supplementary Fig. S8). This hybridization arises from interactions involving B 2s−Au 6s/6px/6py/5dxy, B 2px−Au 6s/6py/5dxy, and B 2py−Au 6s/6px/5dxy orbitals (Fig. 2g–i), demonstrating that Au 5dxy, 6s, 6px, and 6py orbitals actively participate in forming Au−B bonds, and Au atom shows a dsp2 hybridization. In Ca2AuB6, electron donation from Ca atoms leads to charge accumulation on Au. Mulliken orbital population analysis indicates that the additional electrons are primarily distributed in the Au 6s and 6p orbitals (Supplementary Table S4). Meanwhile, the Au 5dxy orbital participates in a dsp2 hybridization and also contributes to the formation of an Au−B anti-bonding orbital (Fig. 2j). This hybridization mechanism is further validated by crystal orbital Hamilton population (COHP) analysis (Fig. 2k) performed with the LOBSTER code82,83. The integral of the COHP (ICOHP) value, reaching up to −4.00 eV per bond, highlights the significant strength of the Au−B bond84. Notably, this dsp2 hybridization in the anionic Au differs fundamentally from the hybridization observed in cationic Au (Au3+). In the latter, Au loses three valence electrons to achieve a formal +3 oxidation state, creating four vacant dsp2 hybrid orbitals that accept electrons from ligands to form coordination bonds24. Additionally, PDOS and ICOHP analysis of Ca2AuB6 at pressures of 25 and 50 GPa reveal its pressure-insensitive hybridization and robust Au−B bonding (Supplementary Fig. S9 and S10).

Electronic and superconducting properties

We also explored the response of the Au-B framework to the nature of the cationic species by substituting the Ca atom with various alkali and alkaline earth metals, resulting in the formation of four dynamically stable M2AuB6 (M = Na, K, Mg, and Sr) compounds at ambient pressure (Supplementary Fig. S11, 12). These compounds also exhibit negative formation enthalpies, indicating their potential thermodynamic accessibility from the selected precursors (Supplementary Fig. S13). The covalency within the Au-B framework remained intact across these substitutions (Supplementary Fig. S14 and Table S5). Band structure calculations (Fig. 3a, d, Supplementary Fig. S15 and S16a) confirmed metallic behavior, with two or three bands crossing the Fermi level (EF). However, the origin of the metallicity differs significantly between Na2AuB6/K2AuB6 and Mg2AuB6/Ca2AuB6/Sr2AuB6. For example, despite similar band dispersion in Ca2AuB6 and Na2AuB6, the EF of Ca2AuB6 is ~2 eV higher than in Na2AuB6 (Fig. 3a, d). This shift arises from the combined influence of differences in valence electron count and elemental characteristics, particularly the substantial contribution of Ca 3d orbitals, along with minor contribution from B1-px/py and Au-5dxy states in Ca2AuB6 (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. S17). Additionally, electron pockets are observed near the A and M points in the Brillouin zone of Ca2AuB6. Additionally, the calculations performed with fully relativistic pseudopotentials including explicit spin-orbit coupling show negligible impact on the electronic structure near the EF (Supplementary Fig. S18), indicating that the scalar-relativistic approximation employed here captures the key electronic feature.

Ca2AuB6 at ambient pressure: a projected electronic band structure, b Fermi surfaces with the color drawn proportional to the magnitude of the Fermi velocity, and c Fermi surface nesting function, ξ(Q). Na2AuB6 at ambient pressure: d projected electronic band structure, e Fermi surfaces with the color drawn proportional to the magnitude of the Fermi velocity, f Fermi surface nesting function, ξ(Q), and g phonon dispersions weighted by the magnitude of the electron−phonon coupling EPC (λqv), projected phonon density (PHDOS), Eliashberg spectral function, α2F(ω), and EPC integral, λ(ω). h Phonon vibration modes for E-1 and B2g modes, with the red arrows on the atoms indicating the direction of their vibrations. i Calculated Tc, λ, and −ICOHP values of Au−B bond for K2AuB6 and Na2AuB6 at ambient pressure.

In contrast, the metallic behavior of Na2AuB6 is primarily driven by contributions from B1-2px/py and Au-6px/6py orbitals (Supplementary Fig. S19a and S20), indicating that electrons in the Au−B bond participate in conductivity. The band structure near EF exhibits distinct features (Fig. 3d), including flat bands along the Г−Z direction and around the M point, as well as steep bands along the Z−A direction. We also investigate their Fermi surfaces, whose topological structures reflect the electronic behavior at EF. In Ca2AuB6, three Fermi surfaces are associated with three energy bands that intersect EF. The first Fermi surface exhibits a porous cylindrical character, originating from a hybridized state of Ca-3dx2−y2/dxy/dz2, B1-2px/py and Au-5dz2/6pz orbitals (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. S17). The other two consist of twelve discrete curved surfaces oriented towards the vertices or edge centers of the Brillouin zone, with a major contribution of Ca-3d orbitals. For Na2AuB6, two energy bands cross EF, giving rise to two Fermi surfaces with intriguing topology. One consists of four interconnected, two-dimensional torpedo-like shapes, while the other features four-leaf clover (Fig. 3e). These Fermi surfaces primarily arise from the contribution of B1-2s/2px/py and Au-5dxy/6px/6py electronic states (Supplementary Fig. S20). Additionally, Na2AuB6 has an obvious nesting behavior along the Z−A−M direction (Fig. 3f), which is slightly stronger than that observed in Ca2AuB6 (Fig. 3c). Overall, these electronic characters in Na2AuB6 are considered favorable indicators for superconductivity85,86.

The superconducting transition temperatures (Tc) of M2AuB6 compounds were estimated using the Allen-Dynes modified McMillan equation87, with μ* = 0.1 (Supplementary Table S6). Mg2AuB6, Ca2AuB6, and Sr2AuB6 remain nonsuperconducting due to their low electron-phonon coupling constants (λ = 0.18–0.21), much smaller than those of Na2AuB6 (λ = 0.64) and K2AuB6 (λ = 0.55). Correspondingly, Na2AuB6 and K2AuB6 exhibit higher predicted Tc values of 10.4 K and 7.0 K, exceeding those of typical Au-based superconductors such as Pt-doped AuTe2 (4.0 K)88,89 and AuAgTe4 (3.5 K)90. The Fermi-level DOS of Na2AuB6 (10.8 states/spin/Ry/unit cell) is slightly higher than that of K2AuB6 (10.7 states/spin/Ry/unit cell), correlating with their λ values and primarily originating from B-2px/2py and Au-6px/6py states. Phonon analysis reveals that both low- and mid-frequency acoustic modes dominate λ in Na2AuB6: the low-frequency contribution mainly originates from the pronounced softening along the M–Γ direction involving B/Au atom vibrations along the Au–B bond, while the mid-frequency contribution arises from the B2g mode associated with the vibrations of B atoms along the Au−B bond axis (Fig. 3g, h). In contrast, in K2AuB6, λ arises from mid-frequency phonons, corresponding to vibrations of B atoms along the Au−B bond axis (Supplementary Fig. S16c, d). This distinction stems from stronger Au–B bonding in Na2AuB6, enabled by the smaller ionic radius of Na (Fig. 3i). Therefore, the higher Tc of Na2AuB6 compared to K2AuB6 arises from the synergistic effects of an enhanced Fermi-level DOS and stronger Au–B bonding strength.

Conclusions

In summary, we have investigated the stabilization of Au−B bonds through the incorporation of electropositive elements and pressure tuning, which led to the discovery of metallic M2AuB6 compounds (where M = Na, K, Mg, Ca, and Sr). These compounds feature distinctive bonding configurations, including Au−B σ-bonds stabilized by dsp2 hybridization, which remain robust under ambient conditions. Our findings underscore the crucial role of charge transfer and orbital hybridization in stabilizing these structures, contributing to their enhanced mechanical strength and thermal stability. Furthermore, we disclose superconductivity in K2AuB6 and Na2AuB6, with Tcs of 7.0 K and 10.2 K, respectively. The increased electron-phonon coupling, particularly from low-frequency phonons associated with Au−B bond vibrations, is identified as a key factor driving superconductivity in these materials. This discovery not only advances our understanding of Au-B chemistry but also opens up new avenues for unconventional bonding strategies in material design, with potential applications in creating functional materials with unique properties.

Methods

Structure searches of CaxAuyBz (x = 1−4, y = 1−2, z = 1−8) at 50 GPa were performed using the Crystal structure AnaLYsis Particle Swarm Optimization (CALYPSO) code91,92,93. Structural optimization and electronic property calculations were carried out using density functional theory (DFT) as implemented in the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)94. The Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) generalized gradient approximation (GGA)95 was employed for the exchange–correlation functional. The projector−augmented wave (PAW) method96 was used, with valence electrons specified as 3s23p64s2 for Ca, 5d106s1 for Au, and 2s22p1 for B. A cutoff energy of 550 eV was adopted, and the Monkhorst–Pack scheme97 with a dense k-point grid spacing of 2π × 0.03 Å−1 was used to ensure excellent convergence of the enthalpy. Phonon calculations were carried out using the finite displacement method98, as implemented in the PHONOPY code99. Ab initio MD simulations in the canonical ensemble (NVT) employed the Nose–Hoover thermostat100, using a 2 × 2 × 2 supercell with a time step of 1 fs over a total duration of 20 ps. The chemical bonding analysis was analyzed using the solid state adaptive natural density partitioning (SSAdNDP) method79 at the 6–31 G*/ANO-R1 level of theory. The crystal orbital Hamilton population (COHP)84 calculations were performed using the LOBSTER software package. Electron−phonon coupling calculations for superconductivity were performed with the QUANTUM−ESPRESSO package101, employing a kinetic energy cutoff of 90 Ry. Further computational details are provided in Supplementary Methods.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Mao, W. L. et al. Bonding changes in compressed superhard graphite. Science 302, 425–427 (2003).

Goesten, M. G. Be–Be π-bonding and predicted superconductivity in MBe2 (M = Zr, Hf). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202114303 (2022).

Lavroff, R. H., Munarriz, J., Dickerson, C. E., Munoz, F. & Alexandrova, A. N. Chemical bonding dictates drastic critical temperature difference in two seemingly identical superconductors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2316101121 (2024).

Belli, F., Novoa, T., Contreras-García, J. & Errea, I. Strong correlation between electronic bonding network and critical temperature in hydrogen-based superconductors. Nat. Commun. 12, 5381 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. The microscopic diamond anvil cell: stabilization of superhard, superconducting carbon allotropes at ambient pressure. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202205129 (2022).

Green, J. C., Green, M. L. H. & Parkin, G. The occurrence and representation of three-centre two-electron bonds in covalent inorganic compounds. Chem. Commun. 48, 11481–11503 (2012).

Eberhardt, W. H., Crawford, B. Jr & Lipscomb, W. N. The valence structure of the boron hydrides. J. Chem. Phys. 22, 989–1001 (1954).

Miao, M. S. Caesium in high oxidation states and as a p-block element. Nat. Chem. 5, 846–852 (2013).

Dong, X. et al. A stable compound of helium and sodium at high pressure. Nat. Chem. 9, 440–445 (2017).

Lin, J. et al. Exploring the limits of transition-metal fuorination at high pressures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 9155–9162 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. Au with sp3 Hybridization in Li5AuP2. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 13, 236–242 (2022).

Sommer, A. Alloys of gold with alkali metals. Nature 152, 215–215 (1943).

Drozdov, A. P. et al. Superconductivity at 250 K in lanthanum hydride under high pressures. Nature 569, 528–531 (2019).

Li, Z. et al. Superconductivity above 200 K discovered in superhydrides of calcium. Nat. Commun. 13, 2863 (2022).

Ma, L. et al. High-temperature superconducting phase in clathrate calcium hydride CaH6 up to 215 K at a pressure of 172 GPa. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 167001 (2022).

Li, Q. et al. Superhard monoclinic polymorph of carbon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 175506 (2009).

Zhao, Z. et al. Novel superhard carbon: C-centered orthorhombic C8. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 215502 (2011).

Zhang, M. et al. Superhard BC3 in cubic diamond structure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 015502 (2015).

Gimeno, M. C. & Laguna, A. Some recent highlights in gold chemistry. Gold. Bull. 36, 83–92 (2003).

Jiang, D. -e & Walter, M. Au40: a large tetrahedral magic cluster. Phys. Rev. B 84, 193402 (2011).

Pyykkö, P. Theoretical chemistry of gold. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 4412–4456 (2004).

Pyykkö, P. Relativistic effects in chemistry: more common than you thought. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 63, 45–64 (2012).

Hutchings, G. J., Brust, M. & Schmidbaur, H. Gold—an introductory perspective. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 1759–1765 (2008).

Faltens, M. O. & Shirley, D. A. Mössbauer spectroscopy of gold compounds. J. Chem. Phys. 53, 4249–4264 (1970).

Lin, J., Zhang, S., Guan, W., Yang, G. & Ma, Y. Gold with +4 and +6 oxidation states in AuF4 and AuF6. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 9545–9550 (2018).

Yang, G., Wang, Y., Peng, F., Bergara, A. & Ma, Y. Gold as a 6p-element in dense lithium aurides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 4046–4052 (2016).

Du, X., Lou, H., Wang, J. & Yang, G. Pressure-induced Na–Au compounds with novel structural units and unique charge transfer. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 23, 6455–6461 (2021).

Schmidbaur, H. & Schier, A. A briefing on aurophilicity. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 1931–1951 (2008).

Schmidbaur, H. & Schier, A. Aurophilic interactions as a subject of current research: an up-date. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 370–412 (2012).

Hashmi, A. S. K. & Hutchings, G. J. Gold catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 7896–7936 (2006).

Wittstock, A. & Bäumer, M. Catalysis by unsupported skeletal gold catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 731–739 (2014).

Sanchis-Gual, R., Coronado-Puchau, M., Mallah, T. & Coronado, E. Hybrid nanostructures based on gold nanoparticles and functional coordination polymers: chemistry, physics and applications in biomedicine, catalysis and magnetism. Coord. Chem. Rev. 480, 215025 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Site-recognition-induced structural and photoluminescent evolution of the gold–pincer nanocluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 9631–9639 (2024).

Albert, B. & Hillebrecht, H. Boron: elementary challenge for experimenters and theoreticians. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 8640–8668 (2009).

Akopov, G., Yeung, M. T. & Kaner, R. B. Rediscovering the crystal chemistry of borides. Adv. Mater. 29, 1604506 (2017).

Chen, T.-T. et al. Spherical trihedral metallo-borospherenes. Nat. Commun. 11, 2766 (2020).

Jian, T. et al. Probing the structures and bonding of size-selected boron and doped-boron clusters. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 3550–3591 (2019).

Oganov, A. R. et al. Ionic high-pressure form of elemental boron. Nature 457, 863–867 (2009).

Chung, H.-Y. et al. Synthesis of ultra-incompressible superhard rhenium diboride at ambient pressure. Science 316, 436–439 (2007).

Gu, Q., Krauss, G. & Steurer, W. Transition metal borides: superhard versus ultra-incompressible. Adv. Mater. 20, 3620–3626 (2008).

Akopov, G. et al. Synthesis and characterization of single-phase metal dodecaboride solid solutions: Zr1-xYxB12 and Zr1-xUxB12. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 9047–9062 (2019).

Huang, H. et al. Deep-ultraviolet nonlinear optical materials: Na2Be4B4O11 and LiNa5Be12B12O33. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 18319–18322 (2013).

Ma, C. et al. Strong chiroptical nonlinearity in coherently stacked boron nitride nanotubes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 1299–1305 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Two-dimensional molybdenum boride (MBene) Mo4/3B2Tx with broadband and termination-dependent ultrafast nonlinear optical response. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 15, 3461–3469 (2024).

Zhao, B. et al. Fabrication of alkali metal boride: honeycomb-like structured NaB4 with high hardness and excellent electrical conductivity. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2110872 (2022).

Ma, T. et al. Ultrastrong boron frameworks in ZrB12: a highway for electron conducting. Adv. Mater. 29, 1604003 (2017).

Huang, M.-X. et al. Hard copper boride with exceptional conductivity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 136301 (2024).

Gou, H. et al. Discovery of a superhard iron tetraboride superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 157002 (2013).

Tang, H. et al. Boron-rich molybdenum boride with unusual short-range vacancy ordering, anisotropic hardness, and superconductivity. Chem. Mater. 32, 459–467 (2019).

Nagamatsu, J., Nakagawa, N., Muranaka, T., Zenitani, Y. & Akimitsu, J. Superconductivity at 39 K in magnesium diboride. Nature 410, 63–64 (2001).

Souma, S. et al. The origin of multiple superconducting gaps in MgB2. Nature 423, 65–67 (2003).

Braunschweig, H. et al. A trimetallic gold boride complex with a fluxional gold–boron bond. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 9735–9738 (2009).

Zhai, H.-J., Miao, C.-Q., Li, S.-D. & Wang, L.-S. On the analogy of B−BO and B−Au chemical bonding in B11O− and B10Au− clusters. J. Phys. Chem. A 114, 12155–12161 (2010).

Chen, Q., Zhai, H.-J., Li, S.-D. & Wang, L.-S. On the structures and bonding in boron-gold alloy clusters: B6Aun− and B6Aun (n = 1−3). J. Chem. Phys. 138, 084306 (2013).

Obrowski, W. Die Struktur der Diboride von Gold und Silber. Naturwissenschaften 48, 428–428 (1961).

Kortus, J., Mazin, I. I., Belashchenko, K. D., Antropov, V. P. & Boyer, L. L. Superconductivity of metallic boron in MgB2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 4656–4659 (2001).

Yang, F., Han, R.-S., Tong, N.-H. & Guo, W. Electronic structural properties and superconductivity of diborides in the MgB2 structure. Chin. Phys. Lett. 19, 1336 (2002).

Mann, J. B., Meek, T. L., Knight, E. T., Capitani, J. F. & Allen, L. C. Configuration energies of the d-block elements. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 5132–5137 (2000).

Mann, J. B., Meek, T. L. & Allen, L. C. Configuration energies of the main group elements. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 2780–2783 (2000).

Rahm, M., Hoffmann, R. & Ashcroft, N. W. Ternary gold hydrides: routes to stable and potentially superconducting compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 8740–8751 (2017).

Dubois, J.-M., Belin-Ferré, E. & Tsai, A. P. Quasicrystals and Complex Metallic Alloys. In Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology (Wiley, 2016).

Burkhardt, F. et al. A new complex ternary phase in the Al-Cr-Sc push-pull alloy. J. Alloy. Compd. 768, 230–239 (2018).

Kelhar, L. et al. The role of Fe and Cu additions on the structural, thermal and magnetic properties of amorphous Al-Ce-Fe-Cu alloys. J. Non Cryst. Solids 483, 70–78 (2018).

Boulet, P. et al. Crystalline and electronic structures of the Al1+xV2Sn2–x (x = 0.19) intermetallic compound. Inorg. Chem. 59, 360–366 (2020).

Zhang, L., Wang, Y., Lv, J. & Ma, Y. Materials discovery at high pressures. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 17005 (2017).

Miao, M., Sun, Y., Zurek, E. & Lin, H. Chemistry under high pressure. Nat. Rev. Chem. 4, 508–527 (2020).

Miao, M.-S. & Hoffmann, R. High pressure electrides: a predictive chemical and physical theory. Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 1311–1317 (2014).

Oganov, A. R., Pickard, C. J., Zhu, Q. & Needs, R. J. Structure prediction drives materials discovery. Nat. Rev. Mater. 4, 331–348 (2019).

Hilleke, K. P. & Zurek, E. 3.13-Crystal Chemistry at High Pressure. In Comprehensive Inorganic Chemistry III 3rd edn (eds Reedijk J., Poeppelmeier K. R.) (Elsevier, 2023).

Han, S. et al. Pressure-driven charge transfer and tunable superconductivity in intermetallic Li–Mg electrides. Superconductivity 15, 100187 (2025).

Vlasse, M., Slack, G. A., Garbauskas, M., Kasper, J. S. & Viala, J. C. The crystal structure of SiB6. J. Solid. State Chem. 63, 31–45 (1986).

Yuan, Z., Xiong, M. & Yu, D. A novel metallic silicon hexaboride, Cmca-B6Si. Phys. Lett. A 384, 126075 (2020).

Wang, J.-T. et al. Body-centered orthorhombic C16: a novel topological node-line semimetal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 195501 (2016).

Kroto, H. W., Heath, J. R., O’Brien, S. C., Curl, R. F. & Smalley, R. E. C60: Buckminsterfullerene. Nature 318, 162–163 (1985).

Li, D., Xu, Y.-N. & Ching, W. Y. Electronic structures, total energies, and optical properties of α-rhombohedral B12 and α-tetragonal B50 crystals. Phys. Rev. B 45, 5895–5905 (1992).

Cordier, G., Dietrich, C. & Friedrich, T. Crystal structures of europium digold pentagallide, EuAu2Ga5 and strontium digold pentagallide, SrAu2Ga5. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 211, 627–628 (1996).

Offermanns, J., Ruschewitz, U. & Kneip, C. Syntheses and crystal structures of novel ternary alkali metal gold acetylides MIAuC2 (MI = Li, Na, K, Rb, Cs). Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 626, 649–654 (2000).

Sun, Y. & Miao, M. Chemical templates that assemble the metal superhydrides. Chem 9, 443–459 (2023).

Zubarev, D. Y. & Boldyrev, A. I. Developing paradigms of chemical bonding: adaptive natural density partitioning. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 10, 5207–5217 (2008).

Corbett, J. D. Exploratory synthesis: the fascinating and diverse chemistry of polar intermetallic phases. Inorg. Chem. 49, 13–28 (2010).

Lin, Q. & Miller, G. J. Electron-poor polar intermetallics: complex structures, novel clusters, and intriguing bonding with pronounced electron delocalization. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 49–58 (2018).

Maintz, S., Deringer, V. L., Tchougréeff, A. L. & Dronskowski, R. LOBSTER: a tool to extract chemical bonding from plane-wave based DFT. J. Comput. Chem. 37, 1030–1035 (2016).

Müller, P. C., Reitz, L. S., Hemker, D. & Dronskowski, R. Orbital-based bonding analysis in solids. Chem. Sci. 16, 12212–12226 (2025).

Dronskowski, R. & Bloechl, P. E. Crystal orbital Hamilton populations (COHP): energy-resolved visualization of chemical bonding in solids based on density-functional calculations. J. Phys. Chem. 97, 8617–8624 (1993).

Simon, A. Superconductivity and chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 36, 1788–1806 (1997).

Pereira, Z. S., Faccin, G. M. & da Silva, E. Z. Predicted superconductivity in the electride Li5C. J. Phys. Chem. C. 125, 8899–8906 (2021).

Allen, P. B. & Dynes, R. C. Transition temperature of strong-coupled superconductors reanalyzed. Phys. Rev. B 12, 905–922 (1975).

Kitagawa, S. et al. Pressure-induced superconductivity in mineral calaverite AuTe2. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 82, 113704 (2013).

Kudo, K. et al. Superconductivity induced by breaking Te2 dimers of AuTe2. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 82, 063704 (2013).

Amiel, Y. et al. Silvanite AuAgTe4: a rare case of gold superconducting material. J. Mater. Chem. C. 11, 10016–10024 (2023).

Wang, Y., Lv, J., Zhu, L. & Ma, Y. Crystal structure prediction via particle-swarm optimization. Phys. Rev. B 82, 094116 (2010).

Wang, Y., Lv, J., Zhu, L. & Ma, Y. CALYPSO: a method for crystal structure prediction. Comput. Phys. Commun. 183, 2063–2070 (2012).

Shao, X. et al. A symmetry-orientated divide-and-conquer method for crystal structure prediction. J. Chem. Phys. 156, 014105 (2022).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758 (1999).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188 (1976).

Parlinski, K., Li, Z. Q. & Kawazoe, Y. First-principles determination of the soft mode in cubic ZrO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 4063–4066 (1997).

Togo, A., Oba, F. & Tanaka, I. First-principles calculations of the ferroelastic transition between rutile-type and CaCl2-type SiO2 at high pressures. Phys. Rev. B 78, 134106 (2008).

Martyna, G. J., Klein, M. L. & Tuckerman, M. Nosé–Hoover chains: the canonical ensemble via continuous dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 97, 2635–2643 (1992).

Giannozzi, P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China under Grants No. U23A20537, 22372142, 12304028, and 12404027, the Foreign Expert Introduction Program (G2023003004L), the Central Guiding Local Science and Technology Development Fund Projects (236Z7605G), the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province (Grant No. B2024203051, A2024203023, and A2024203002), the Science and Technology Project of Hebei Education Department (Grants No. JZX2023020), Innovation Capability Improvement Project of Hebei province (22567605H), and Hebei Province Yan Zhao Huang Jin Tai Talent Program (Postdoctoral Platform, B2024003003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.H. performed calculations, analyzed the data, and wrote the original draft; X.Z., S.W., and S.D. assisted the calculations, and participated in the data analysis; L.Z., E.Z., and G.Y. wrote and modified the manuscript; G.Y. conceived the initial idea and supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Yue-Wen Fang and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, S., Zhang, X., Zhu, L. et al. Ambient-pressure superconductivity in covalent Au-B frameworks stabilized by electropositive metals. Commun Chem 8, 342 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01723-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01723-8

This article is cited by

-

Li-F polarity-driven stabilization of −VII oxidation state of gold at high pressure

Nature Communications (2025)