Abstract

The use of pressure to obtain new materials that can be recovered under ambient conditions is a central problem in high-pressure physics. Despite decades of research, this goal has only been achieved in the laboratory for a few notable examples, such as diamond and cubic boron nitride. An area of significant interest is the transformation under compression of light-element molecular compounds to extended covalent-bonded (polymeric) solids. Among them, CO2 has been extensively studied because of its status as a prototypical simple molecular system with a rich phase diagram and due to its fundamental role in Earth’s physics and chemistry. One of its polymeric crystalline phases, accessible at extreme pressures and temperatures, has been recently quenched to ambient pressure, but below room temperature. Here we report ab initio calculations predicting that isothermal compression of a carbon monoxide and oxygen mixture (CO+O2), rather than the compound CO2, lowers the onset of C-polymerization at room temperature from ~ 118 GPa to ~ 7 GPa (complete by ~ 23 GPa). Moreover, it leads to the formation of an intrinsically different polymer with enhanced metastability. We predict that this dense phase is an energetic material which can potentially be recovered to ambient pressure and temperature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the high-pressure sciences, there have been discoveries of exotic crystalline phases of even simple elements such as Ca1, Na2, and Li3. However, almost without fail, thermodynamic or kinetic effects lead to the breakdown of such exotic phases upon decompression (relaxation) and their practical applications as superhard4 or high-energy-density (HED) materials have been precluded, albeit with a few exceptions such as diamond5 and cubic boron nitride6,7.

The confluence of high-pressure physics and energetic materials research has led to the prediction that the high-pressure (~110 GPa) and high-temperature (~2000 K) synthesis of cubic gauche nitrogen (cg-N, space group I213)8,9 would lead to an energetic material having upper end estimates of energy content more than twice that of TNT (>10 kJ/g), undoubtedly the most energetic non-nuclear composition in existence. Practical use would, of course, depend on developing a method for synthesizing the material at ambient pressure and temperature, which has very recently been suggested10, as all attempts at decompression-based recovery have failed. The materials further explored in this category include compressed phases of N-rich compounds8,11,12,13,14,15, CO216,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28, CH429, NH330,31, and CO32,33,34. They form extended covalent-bonded (polymeric) solids that, if recovered to ambient conditions, would be in a high-energy metastable state. A subsequent transition to a thermodynamically stable phase would release a large amount of energy. Naturally, much research has focused on attempts to make the synthesis conditions more accessible while increasing the HED content and ambient-condition metastability of the high-pressure phases. These requirements are often conflicting.

Carbon dioxide was one of the first molecular systems that was shown to polymerize under compression35,36. Given its fundamental nature and importance for understanding the physics and chemistry of the Earth, its phase diagram has been of particular interest to the high-pressure research community17,37,38,39. Below 200 K and at ambient pressure, CO2 exists in phase I as a molecular solid ‘dry ice’ cubic structure (Pa3). At pressures above ~12 GPa, CO2-I transforms to the molecular CO2-III (Cmca), CO2-II (P42/mnm) or CO2-IV (Pbcn), in increasing order of temperature16,17.

Thereafter, the picture becomes somewhat uncertain. A fully covalent-bonded CO2-V structure was obtained above 40–60 GPa with heating up to 1800 K, and reported as either tridymite (high temperature polymorph of silica/SiO2, tetrahedrally bonded/fourfold-coordinated)-type (P212121) at higher temperatures40 or an extended-solid cristobalite-type (I4-2d) at lower temperatures25,41. Metadynamics simulations22 starting from CO2-III at ~80 GPa and <300 K suggest an intermediate Pbca ultimately evolving to an α-cristobalite-like (P41212) fourfold-coordinated structure, whereas CO2-II at ~60 GPa and ~600 K transforms to a fully tetrahedral, layered structure (P\(\overline{4}\)m2). However, experimental observations21 reported a fully covalent extended-solid sixfold-coordinated stishovite-type CO2-VI (P42/mnm) obtained directly by compressing CO2-II above 50 GPa and at 530-650 K.

There have also been predictions by simulations19,42 and observations in laser-heated conditions43 above 40 GPa of an amorphous phase called carbonia/a-CO2. A combination of experiments and simulations44 have shown that the actual nature of CO2 in the 40–100 GPa region is a mixture of three- and four-fold coordinated metastable phases, manifesting as a-CO2, rather than any particular well-defined fully tetrahedral phase. Recent attempts to recover polymeric crystalline CO2-V (P212121) have shown that the recovered product decays to dry ice/CO2-I (Pa\(\overline{3}\)) at 185 K45. As such, recovering polymeric CO2 to atmospheric pressure at room temperature has been hitherto elusive27.

In general, pressure-induced polymerization of molecular compounds can be divided into two types, thermodynamic and kinetic transitions46. The former takes place between phases that are in thermodynamic equilibrium (specifically, the lowest free energy phases of the pure material). The compression of CO2 and N2 until polymerization falls into this category. Here, the amount of energy stored in the polymeric phases creates a trade-off with the accessibility of synthesis conditions. In the second type, the transition is from or to a phase which is metastable (i.e., a high-energy state). Thus, the kinetic barrier that separates the molecular and polymeric phases can be overcome at relatively low pressure. This is the case for CO, where the polymeric (p-CO) rather than the molecular phase is the lowest free energy state of pure CO under ambient conditions, and the onset of the transition is only at around 5 GPa at 300 K. However, the usefulness of p-CO as a HED material is limited by the fact that its relevant exothermic reaction, namely the decomposition of p-CO to \({CO}_{2}^{(g)}\) + C, contains a product (C) with a relatively high formation energy33.

The challenge and a key for discovering a useful material is to combine the benefits of the two types of transitions. Systems such as polymeric CO2 (p-CO2) and cg-N are compelling due to the significant energy differential between these and their stable molecular phases at ambient pressure. However, to reduce the transition pressures, we wish to arrive at one of these polymeric phases via a kinetic transition from a high-energy state compared to their molecular phases. These considerations have motivated us to investigate the polymerization of a mixture of CO and O2, stoichiometrically equivalent to the compound CO2.

Another reason for evaluating this system is the expectation that amorphous systems offer more possibilities to achieve high metastability. First, decompression of high-pressure covalent crystalline phases can cause significant bond strains, leading them to become dynamically unstable. Second, kinetic barriers depend on the atomic arrangements, and amorphous solids have higher degrees of freedom for such arrangements.

Here, we show that isothermal compression of a mixture of CO and O2 at 300 K leads to a polymer stoichiometrically equivalent to p-CO2, but accessible at much lower pressure than when compressing molecular CO2 (m-CO2). Importantly, the resulting amorphous polymer is structurally different from the known p-CO2 phases and exhibits a higher degree of metastability. Our study indicates that it can be stabilized at even elevated temperatures at near-atmospheric pressure. In the next section, we describe the first-principles simulations leading to this prediction, followed by an analysis of structural and thermodynamics properties and metastability, comparative with that of the relevant solid CO2 phases.

Results

Prediction of polymerization and recovery at 300 K

A gaseous mixture of molecular CO and O2 was initially equilibrated using ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations at ambient temperature and pressure conditions. It was then isothermally compressed along the 300 K isotherm. This approach results in the simulation of amorphous, rather than crystalline, polymeric high-pressure phases. It is intended to mimic experimental conditions, and in the case of CO was shown to agree well with measurements33.

As detailed in the following sections, simulations were performed using (1) different numbers of atoms (as high as 864) to ensure size convergence and (2) various exchange-correlation functionals to confirm that the results are not artifacts of the functional choice. Unless specified otherwise, the discussion refers to the calculations with 432-atom supercells using the PBE exchange-correlation functional with DFT-D3 (zero damping)47 semi-local dispersion forces. A full description of computational details can be found in the “Methods” section and Tables S1 and S2 in Supplementary Discussion 1.

In these simulations, the onset of pressure-induced polymerization is predicted at approximately 7 GPa (~80% of ambient cell volume). The transformation is gradual; the early polymeric phase consists of broken chains and transient 4-member C−O rings. By ~23 GPa, complete polymerization of the CO molecules is observed (denoted as the pa phase), characterized by −O(CO)− chains linking either planar or non-planar 5-member (C,O) rings and 6-member (C,O) rings.

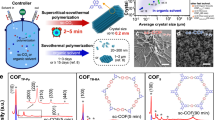

A visualization of the amorphous pa phase with fully-polymerized C atoms is shown in Fig. 1a. The fraction of carbon and oxygen atoms locked in different bonding configurations in chains and rings is shown in Fig. 1b as a function of the simulation cell size (see Supplementary Discussion 2 for further details). The 432-atom simulations are well-converged with respect to equilibrated pressure and bonding statistics. Finally, upon decompression (simulated for a total of 10.1 ps) from the highest compressed configuration at ~32 GPa along the 300 K isotherm, the pa phase is retained all the way to ambient pressure with only a minor change in the bonding statistics (see Supplementary Figs. S1–S3).

Results from isothermal compression of CO + O2 mixtures using NVT-AIMD simulations along the T = 300 K isotherm. a Polymerized amorphous product in an 864-atom cell at 32.6 ± 0.7 GPa and ρ = 3.23 g/cc after simulation time of 11 ps at 300 K. Red and brown spheres indicate oxygen and carbon atoms, respectively, with chain and ring regions color-coded as shown. b Comparison of simulation results obtained with different cell sizes at ρ = 3.23 g/cc. Shown are the percentage of atoms locked in −O−C− and −C−C− bonds, and the equilibrated pressure P. Convergence is reached with 432-atom simulations. Violet and gray spheres correspond to oxygen and carbon atoms, respectively. The dimensions of the cubic box simulation cells are shown in Angstroms. c Starting from a molecular gaseous mixture of CO and O2, labeled as phase mg, the resulting phases from AIMD and metadynamics searches are shown in perspective view. The polymeric crystalline phases pc1 (84-atom Pbcn) and pc2 (36-atom P1) were obtained from constrained metadynamics searches. At pressures above 10 GPa, the polymeric amorphous phase pa is energetically preferred, as can be seen in the enthalpy versus pressure and density plots. The brown arrows and markers point to the change in the enthalpy and density when NPT-AIMD simulations are performed on the crystalline phases.

Machine-learned molecular dynamics (MLMD) simulations using a 2926-atom cell and a total simulation time of 2.5 ns at the 300 K compression isotherm also confirm the emergence of the amorphous structure observed in the AIMD simulations (see Supplementary Fig. S6 for details).

To explore the possibility of formation, under isothermal compression, of [CO+O2]-like crystalline structures that are energetically competitive with the pa phase, we complemented the above approach with constrained metadynamics simulations. In this methodology, the CO and O2 bond lengths were constrained to remain close to their unreacted equilibrium values. The simulations yielded two polymeric crystalline phases: one with an 84-atom unit cell (space group Pbcn) and another one with a 36-atom unit cell (P1), denoted as pc1 and pc2, respectively. A visualization of these phases and a comparison of their enthalpies to that of the amorphous pa are shown in Fig. 1c. They are energetically favorable to pa only in a small pressure region below 10 GPa, and when subjected to constant-pressure AIMD, they become disordered (see Supplementary Fig. S4 for visualization). Upon further compression, they amorphize to structures identical to pa. Therefore, we conclude that while intermediate crystalline phases are possible, isothermal compression at 300 K of a mixture of molecular CO and O2 leads to the amorphous phase pa at pressure above 10 GPa, which will be the principal focus of this paper. Note that all these phases are metastable relative to known molecular and polymeric CO2 phases, as will be discussed in the following sections.

A consideration when analyzing the stoichiometry of the compressed pa polymer is to determine if there are any residual unreacted molecules remaining in the system. We observe that at around 30 GPa, when the C atoms are fully polymerized, there are a few remaining O2 molecules. Upon further compression, these residual molecules form oxygen chains, and at ~88 GPa, they attach to the remaining polymer without affecting its structure. We have investigated several different recipes for the formation of polymers with exact CO2 stoichiometry, including over- and undersaturation with O2, compression along a higher temperature isotherm, and heating the pa phase at 32 GPa followed by further compression. The results for the enthalpy, stoichiometry, and structural details of the phases obtained in these computational experiments are summarized in Fig. 2.

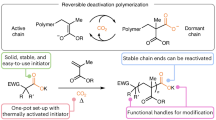

a Enthalpy versus pressure plots for 192-atom NVT-AIMD simulations along compression trajectories at (left) 300 K and (right) 500 K. Plotted are results for systems with stoichiometric CO2 mixtures, as well as such with 11% over- and under-saturation of oxygen. The red symbols in the left panel indicate a system heated to 500 K at about 32 GPa and then further compressed. The remaining results are for isothermal compressions starting from below 7 GPa. The labels to selected points indicate the stoichiometry of the polymeric phase achieved at various pressures and the presence of unreacted (\({O}_{2}^{(s)}\)) or polymerized (p-O) oxygen. b Radial distribution function, g(r), for CO1.88+\({O}_{2}^{(s)}\) (top) and CO2 (bottom) along the 300 K compression trajectory at approximately 32 and 88 GPa, respectively. The inset cartoons show how the remaining unreacted O2 molecules at 32 GPa link up to form chains in fully-polymerized CO + O2 at 88 GPa.

As evident from the data, compressing the gas mixture at higher temperature lowers the polymerization pressure and brings the polymer closer to CO2 stoichiometry near 30 GPa. Oxygen undersaturation delays the onset of polymerization, while oversaturation does not accelerate it. On the other hand, oversaturation reduces the pressure at which oxygen is fully locked up in the polymeric structure. Thus, as a recipe for experimentalists to achieve a polymer with exact CO2 stoichiometry, we propose a combination of oversaturation and compression at elevated temperatures starting from below 7 GPa. However, in the remainder of this paper, the analysis will focus on the properties derived from the pa phase at 32 GPa and 300 K, corresponding to CO1.88+\({O}_{2}^{(s)}\). Having a few non-reacted O2 molecules, it provides a lower bound for the stability of the recovered polymer and its energy content.

Finally, we verify the mechanical stability of the recovered polymeric phase, which we denote as pa,rc. The computed phonons do not exhibit any imaginary modes (see Supplementary Fig. S5), which indicates that pa,rc is metastable. However, it is important to note that this standard approach does not provide information about the magnitude of kinetic barriers and, consequently, the temperature range over which the system remains stable.

To further ascertain the kinetic stability of the recovered polymer, we performed two-phase simulations where 624-atom simulation cells were filled with 192 atoms of the gaseous mg phase and 432 atoms of the recovered polymeric pa,rc phase. A NVT-AIMD simulation was thereafter run for the two-phase mixture at 300 K for a total simulation time of 8.8 ps (the system is well-equilibrated by 3.1 ps), equilibrating to a near-ambient pressure of 1.6 ± 0.6 kbar. As can be seen in Fig. 3a, b, there is coalescence of the polymeric chains with the gaseous mixture during the simulation. However, from the radial distribution function, g(r), shown in Fig. 3c, it is evident that the gaseous and amorphous parts of the mixture remain intact. The first peak of the g(r), bifurcated at 1.16 Å and 1.25 Å, corresponds to the original molecular gaseous phase and changes insignificantly, with a slight reduction in the second peak due to the coalescence described earlier. The small features between 1.3 Å and 2.8 Å, which are signatures of the polymeric structure, remain unchanged during the simulations.

Two-phase AIMD and MLMD results for the stability of polymeric amorphous material pa,rc[CO + O2]. Visualization of the a initial and b final atomic configurations along a 624-atom two-phase simulation trajectory (432 atoms initially in pa,rc[CO+O2] and 192 atoms in molecular m[CO+O2] at P = 1.6 ± 0.6 kbar and T = 300 K. Oxygen and carbon atoms are shown in red and brown, respectively. c Radial distribution function, g(r), for the initial (top) and final (bottom) configurations. The latter is averaged over simulation time of 5.7 ps, after equilibrating for over 3.1 ps. The insets show the polymeric g(r) features that do not alter significantly during the course of the simulation. d Computed pressure during the AIMD simulation run is shown to remain at 1.6 ± 0.6 kbar. The 15,600-atom configurations at e the initial and f the final (after 100 ns) stages of an MLMD run, together with the associated radial distribution functions g(r), demonstrating the stability of the recovered amorphous structure at larger length and time scales. g Computed pressure during the MLMD simulation, showing to equilibration at 1.9 ± 0.3 kbar. h Mean square displacements of C and O atoms from the gaseous and polymeric phases during the MLMD run, demonstrating the stability of the latter. i Parity plots of energy and forces for the machine-learned interatomic potential (MLIP), with RMSE values indicated. j Normalized vibrational density of states (VDOS) for AIMD (over 8.8 ps), MLMD (over the first 8.8 ps), and MLMD (over the entire 100 ns).

To confirm the predictions of the AIMD simulations regarding the stability of the recovered polymer, we performed MLMD for a 15,600-atom two-phase cell over 100 ns. This system comprised 4800 atoms in the molecular gas phase and 10,800 atoms in the amorphous pa,rc structure. As shown in Fig. 3e, f, the two phases coexist without loss of kinetic stability for 100 ns, as indicated by the qualitatively unchanged radial distribution function. The mean square displacement (MSD) of different atom types provides a more intuitive perspective: C and O atoms initially part of the pa,rc structure remain locked within it, while bulk gas and interfacial C and O atoms drift slowly until equilibrating at approximately 20 ns. The trapped O2, as discussed earlier in Fig. 2, diffuses out of the amorphous structure without affecting the kinetic stability of the amorphous network.

The system equilibrates to a pressure of 1.9 ± 0.3 kbar, indicating near-ambient, multi-nanosecond stability of the two-phase system. The validity of the MLMD simulations relies on the accuracy of the machine-learned interatomic potentials (MLIP), as demonstrated by the root mean square error (RMSE) in energies and forces shown in Fig. 3i. Additional validation was obtained by comparing the vibrational density of states (VDOS) across different timescales. The torsional and bond-bending modes, as well as their distributions, remain fundamentally unchanged from picosecond to nanosecond timescales, although some shuffling occurs among the layer and bond-stretch modes. This can be intuitively attributed to the release of trapped O2, which induces more breathing vibrational modes within the system. As a result, any local layer-like characteristics are relaxed, allowing for increased lateral stretching in the amorphous network.

These results confirm the mechanical as well as kinetic stability of the polymeric phase at 300 K and a near-ambient pressure, with the highest temperature of stability being 700 K, when partial breakdown of the polymeric chain starts (discussed later).

Stability comparison with respect to compression and recovery of initially molecular carbon dioxide

Validating and understanding our theoretical findings for the polymerization of CO+O2 requires an apt comparison with that of the well-studied CO2 system. In this section, we examine comparatively the metastability of the two systems. For the latter, we consider three cases—crystalline CO2-V (P212121) and two amorphous solids generated as described below.

CO2-V, as alluded to earlier, is the only polymeric carbon dioxide phase that has been recovered to ambient conditions, but only at temperatures below 200 K45. Because single-phase AIMD simulations usually cannot capture crystalline transitions, due to simulation cell size and time constraints, we have used the experimental P212121 structure as our starting point16. After equilibrating this structure at 60 GPa and 100 K, we decompressed it along the 100 K isotherm. However, at 4.9 ± 0.2 kbar, when increasing the temperature to only 200 K, this crystalline phase breaks down to gaseous CO2 (see Supplementary Fig. S7) in complete agreement with the experimental results.

Next, we generated amorphous a-CO2 similarly to the way it was synthesized experimentally. For this purpose, 144-atom simulation cells with gaseous CO2 were heated to high temperature at ambient pressure using a NVT ensemble (to overcome kinetic reaction barrier) and subsequently compressed to pressures in the span of ~60 to ~118 GPa to overcome barriers for complete polymerization. After polymerization, they were slowly quenched to 300 K or below. For example, at ~60 GPa, a kinetic barrier of roughly 600 K has to be overcome in order to obtain an amorphous structure on quenching to 300 K. This kinetic barrier is inversely proportional to the pressure, and the barrier becomes only 300 K at ~118 GPa. The resulting a-CO2 obtained this way is a mixture of three- and four-coordinated carbon atoms. It can be recovered to ambient conditions only along the 200 K or lower temperature isotherm and breaks down to gaseous CO2 when heated up (in single-phase NVT-AIMD) to 300 K at 8.2 ± 0.2 kbar (see Supplementary Fig. S8). When decompressed along the 300 K isotherm, it breaks down to a molecular phase below ~30 GPa.

Finally, for a direct comparison with the polymerized CO and O2 mixture (referred to as pa,rc[CO+O2] here and in the following section for clarity), we obtained polymeric p-CO2 (referred to as pa,rc[CO2] in this section) directly by isothermal compression of 144-atom CO2 simulation cells along the 300 K isotherm. A polymeric phase emerges beyond ~118 GPa comprised of entirely 4-coordinated carbon atoms. This is, in fact, the limiting case of a-CO2, as mentioned in the previous paragraph. As pressure is reduced, pa,rc[CO2] gradually changes from a fully four-coordinated to a mostly three-coordinated structure. Upon isothermal decompression to 6.2 ± 0.2 kbar at 300 K, this polymeric phase persists but breaks down to gaseous CO2 at temperature at or above 400 K in single-phase NVT-AIMD simulations (see Supplementary Fig. S9).

Among the three aforementioned cases, only the latter yields a polymeric structure at ambient conditions. However, its stability is still significantly lower than that of pa,rc[CO+O2], which persists at temperatures of at least 1000 K when heated at 7.7 ± 0.3 kbar (see Supplementary Fig. S9) as well as at ~29 GPa (see Supplementary Fig. S10) in single-phase simulations.

However, single-phase (heat-until-breakdown) simulations may overestimate the stability of the simulated phase. To determine more accurately the temperatures at which the polymeric phases break down, we carried out two-phase NPT AIMD simulations. Here, the target pressure was set to 1 kbar instead of 1 atm, as barostat fluctuations at lower pressures can produce transient negative normal stress components. Under these conditions, it was observed that pa,rc[CO2] breaks down to a gaseous molecular form at just 300 K and 3.2 ± 0.1 kbar (see Supplementary Fig. S11), while pa,rc[CO+O2] remains stable up to 700 K at 4.7 ± 0.2 kbar (see Supplementary Figs. S12 and S13), only beginning to partially break down at this temperature.

Additionally, we performed two-phase NVT MLMD simulations using 11,520-atom cells composed of polymeric amorphous pa,rc[CO+O2] and a gaseous phase (molecular CO2 or CO+O2). As shown in Fig. 4, the structure remains intact at 500 K and only begins to break down upon heating to 700 K. This occurs regardless of whether the amorphous system is in contact with CO2 or CO+O2.

Kinetic stability of the polymeric amorphous pa,rc[CO+O2] phase, assessed using 11,520-atom MLMD two-phase simulations (pa,rc[CO+O2] on one side and gaseous, molecular m-CO2 on the other), by heating the two-phase cell to 500 and 700 K over a total simulation time of 152.6 ns. The polymeric amorphous phase begins to decompose at 700 K, as indicated by the topmost radial distribution function.

Thus, our results predict that compressing CO+O2, rather than CO2, not only induces polymerization at lower pressures but also produces a polymer that is significantly more stable upon pressure release. Note that during AIMD simulations, negative (tensile) normal stress components along any axis can cause unphysical fragmentation of the polymers. To avoid this, the simulations were equilibrated at a kilobar of pressure. However, the PBE exchange-correlation functional is known to overestimate the pressure in polymeric phases (as discussed in the “Energetics” section). Therefore, these results can be used to ascertain the physics at ambient pressure.

Structural properties

The stability of polymers is directly linked to their atomic arrangements. To understand the differences among the recovered pa,rc[CO+O2] and pa,rc[CO2] phases, we therefore present a comparative analysis of their structural properties.

A qualitative comparison of radial distribution functions in Fig. 5a shows that the pa,rc[CO2] structure is only centered around C−O bonds. In contrast, pa,rc[CO+O2] has C−O, C=O, C−C, and O−O bonds, all contributing to the formation of chain-ring structures. Ball-and-stick models for the predicted chain or chain-ring structures are shown in Fig. 5b. The chain-ring structure in pa,rc[CO+O2] is quite nuanced, with 5-member rings linked into the −O(CO)− chains (shown as 5l), 5-member rings networked into a cage-type bonding mesh (shown as 5n), and 6-member rings interlocked with 5-member rings (shown as 6i). In contrast, the structure of pa,rc[CO2] is just −O(CO)− chains.

Comparative analysis of the structural features of the recovered polymeric phases of CO2 (pa,rc[CO2] at 200 K) and CO+O2 (pa,rc[CO+O2] at 300 K). a Pairwise radial distribution function, g(r), for both systems at near-ambient pressures. b Comparison of chain structures, with carbon and oxygen atoms shown in gray and red, respectively. Here, 5l, 5n, and 6i indicate 5-member chain-linked, 5-member networked, and 6-member interlocked rings, respectively. c Partial crystal orbital Hamiltonian population (pCOHP) for pa[CO+O2] for C-centered (top-left) and O-centered (top-right) bondings, as well as the integrated COHP as a function of bond order for selected pressures. d Nearest neighbor coordination number (NNCN) histograms for C−O, O−C, O−O, and C−C pairs.

The partial crystal order Hamiltonian population (pCOHP)48,49,50 analysis of the pa[CO+O2] phase, shown for C-centered and O-centered bonds in Fig. 5c, shows the usual C−O and O−O (single) σ-σ* bonding-antibonding orbital combinations and the O=C (double) π-π* combination. Of significance here are the unusually strong C=C π-π* bonds (ΔE ~ 16 eV) and C−C σ-σ* bonds (ΔE ~ 13 eV). The C=C π-π* bonds originate in the 6-member rings, which themselves are a result of including London dispersion forces in the simulations, while the C−C σ-σ* bonds are present in the 5-member rings. Recall that at ambient conditions, all stable molecules formed from elements in the second row of the periodic table have stronger σ than π bonds. The absence of these bonds in pa,rc[CO2] (evident from the g(r) in Fig. 5a) may be a contributing factor in its reduced kinetic stability during decompression.

Another important parameter when analyzing pressure-induced structures such as pa,rc[CO+O2] is the bond order. For synthesizing energetic materials using a compression-decompression method, ideally, we would want a transition similar to the formation of cg-N, where all triple bonds delocalize into single bonds. The integrated COHP (ICOHP) versus the bond order of pa,rc[CO+O2] as a function of pressure is shown in Fig. 5c, the bond order being calculated using the integrated crystal order bond index (ICOBI) analysis50,51. As the pressure increases from 15 GPa to 31 GPa, the value of the maximum bond order reduces from ~3 to ~2, indicating that the system is evolving towards a higher energetic state.

A distribution of the nearest-neighbor coordination numbers (NNCN) for the C−O, O−C, O−O, and C−C pairs in pa,rc[CO+O2] and pa,rc[CO2] is shown in Fig. 5d, with their mean values summarized in Table 1. The main observation here is the near absence of C−C and O−O bonding in pa,rc[CO2]. The average C−O NNCN of ~3, alongside O−C NNCNs of 1 and 2, also suggests the abundance of three-coordinated −O(CO)− chains in that structure, which is in clear contrast to pa,rc[CO+O2], where the chain intermittently has 5- and 6-member rings, thereby decreasing the mean C−O NNCN. The crystalline CO2-V (P212121) phase, recovered to ambient pressure and 100 K, is also included in the table, again showing a complete absence of C−C bonding. It is important to note the existence of O−O pairs in both recovered systems, as mentioned earlier for the CO+O2 case.

The structural differences among the various polymerized systems originate from their distinct reaction trajectories during compression, as discussed in the section on chemical dynamics later. The linear geometry of O=C=O molecules imposes geometrical constraints on their approach to one another—constraints that are absent in the CO + O2 mixture. These limitations inhibit C–C bond formation, resulting in differences in the polymerized structures that ultimately form.

In summary, the compression of a CO and O2 mixture leads to the formation of a drastically different high-pressure structure compared to that of compressed CO2. The structural differences manifest in increased metastability of the polymerized amorphous product when it is recovered to ambient pressure.

Energetics

The potential use of pa,rc[CO+O2] as an energetic material depends on the density of the recovered phase and its energy relative to the thermodynamically stable phase at ambient conditions, namely, molecular CO2. In this section, we focus on computing these properties.

For a more detailed look at the energetics of the systems under consideration, we went beyond the PBE (GGA) exchange-correlation functional. In order to estimate the formation enthalpy of the final polymerized product more accurately, NVT-AIMD simulations were performed for the full compression-decompression trajectories with PBE52, PBE + D3[BJ]53, PBE + D3[0]47, PBE + rVV1054,55, and SCAN-L56 + rVV10 combinations. Cell sizes with 432 and 864 atoms were used for the PBE and 258 atoms for the SCAN-L AIMDs (summarized in Supplementary Table S1). In addition, static single-point calculations were performed on five to seven configurations at each density along the PBE-calculated isothermal 108-atom AIMD trajectory using SCAN57, SCAN + rVV10 and HSE0658 functionals, and then averaged. Fermi-Dirac smearing corresponding to a temperature of 300 K was used for these calculations.

The pressure-density equations of state (EOS) for the CO+O2 system are shown in Fig. 6a, calculated using the different combinations of exchange-correlation functions, van der Waals treatment and cell sizes (see Figs. S13–S17 for a broader version). The kinks in the EOS curves coincide with the initialization of −C−C− polymerization. There is a general downward revision of pressure for the same density for SCAN-L and HSE06 w.r.t. PBE calculations, similar to observations of Bonev et al.33 on CO simulations for HSE06 w.r.t. PBE.

a Equations of state along the compression-decompression paths of CO+O2 obtained within NVT-AIMD at T=300 K using various combinations of cell sizes, exchange-correlation functionals and van der Waals treatment. Solid and dashed lines indicate compression and decompression paths, respectively. b Pressure ranges over which the formation of −C−C− and −C−O− bonds and rings are observed under different simulation parameters. The red error bars are the standard deviations of the pressures in the ensemble-averaged NVT-AIMD simulations.

The ranges of pressure over which −C−C− and −C−O− bonds and rings form are shown in Fig. 6b for the different combinations of cell size, exchange-correlation functional, and van der Waals treatment used. It can be seen that the polymerization process is delayed when using meta-GGA, but the behavior of sequential bond formation remains consistent. With respect to the PBE + D3[0] 864-atom simulations, which form the bulwark of the analyses in this paper, the pressure domains for −C−C−, −C−O− and rings are ~7.1–8.5 GPa, ~12.2–13.2 GPa, and ~19.3–23.2 GPa, respectively.

Figure 7 shows the equations of state for the compression-decompression cycle of the CO+O2 system from NVT-AIMD simulations using an 864-atom cell, alongside the same cycle for 144-atom CO2 cells at 200 K, all within PBE + D3[0]. The CO2 system ends with an enthalpy higher than its starting molecular state, which is expected because molecular CO2 is the most stable form at ambient pressure. A similar curve for the polymeric crystalline pc2[CO+O2] system (obtained from metadynamics) was also evaluated, where it was decompressed to ambient conditions using NVT-AIMD simulations in a 288-atom cell. However, this crystalline phase breaks down into the constituent CO and O2 molecules below a pressure of ~9 GPa and a density of ~1.7 g/cc. This confirms that only the amorphous polymeric phase of CO+O2 is recoverable.

Equations of state along the compression-decompression paths of the amorphous pa,rc[CO+O2] obtained using NVT-AIMD at T=300 K, the polymeric crystalline pc2[CO+O2] obtained with metadynamics along the compression path and subsequently decompressed using NVT-AIMD at T=300 K, and the compound CO2 obtained with NVT-AIMD at T=200 K are presented in a pressure-density, b enthalpy-pressure, and c enthalpy-density spaces. The solid and dashed lines represent the compression and decompression paths, respectively. All curves are evaluated within PBE + D3[0], using 432-atom, 288-atom, and 144-atom simulation cells for amorphous CO+O2, crystalline CO+O2, and CO2, respectively. The curves corresponding to CO+O2 in Fig. 6a are the same as the PBE + D3[0] data shown in Fig. 1b. The data for CO2 is only shown up to 40 GPa, while the polymerization of this system commences beyond ~118 GPa at 300 K.

The comparative analysis of density values, in Table 2, shows a compression of an initial gaseous mixture (mg) with a density of 0.021 g/cc to a recovered polymer (pa,rc) with density of 2.04 g/cc within PBE + D3[0]; this can be as high as 2.28 to 2.34 g/cc with corrections using meta-GGA or hybrid functionals. It is important to mention here that the deviation in the calculated values for the mass density and volumetric energy density is approximately 41% and 32%, respectively, although the gravimetric energy density varies only by 7%. The formation enthalpy of ~204–243 kJ/mol (~4.6–5.5 kJ/g) is more than that of CO, which stands at ~95 kJ/mol (~3.4 kJ/g)33, i.e., more stable. Furthermore, unlike CO, this composition is not susceptible to decomposition to graphite and oxygen, but converts to lower energy molecular CO2 at a sufficiently high T > 500 K. In essence, the process ends up yielding a denser polymer both gravimetrically and energetically.

In terms of comparison to carbon dioxide, also shown in Fig. 7, the recovered pa,rc[CO2] differs from the recovered pa,rc[CO+O2] with a density higher by ~0.1 g/cc and an enthalpy lower by ~1 eV/CO2 molecule. This suggests that for near-similar quantitative bulk properties of the recovered amorphous phase, a significant reduction in polymerization onset pressure has been achieved.

Phenomenological analysis of chemical dynamics

To understand the formation of the pa phase and its structural differences from the polymeric CO2 phases, we analyze the atomic dynamics within the CO+O2 and CO2 systems before and after the onset of polymerization. We define the atomic number density, ρN(r), as the number of atoms within a sphere of radius r centered on an atom, averaged over all atoms and configurations in the AIMD. The sphere around each atom, inside which the first monomers start forming, has a radius equal to the first minimum of ρN(r) and is called the kinetic sphere of radius Rks.

The evolution of the atomic arrangement in CO+O2 along a compression trajectory—from a nearly homogeneous molecular system at t = 0 (ambient pressure) to an aggregated one with Rks = 5.3 Å at t = 1 ps (P ≈ 7 GPa)—is illustrated in Fig. 8b. Since Rks is easily discernible only in the density region where the polymerization occurs, we define Rks along the entire compression trajectory as:

a An illustration of kinetic sphere of radius Rks (shaded as a blue circle) and kinetic diameter ϕ defined in the text. b Radial number density, ρN, for the CO + O2 system at ambient pressure (t = 0) and the onset of polymerization (t = 1.0 ps) along a compression trajectory. c Evolution of the kinetic \([C-O]{\overline{\phi }}_{1}\) versus \([C-C]{\overline{\phi }}_{2}\) diameters along isothermal compression simulations starting from ambient pressure at 300 K. The CO + O2 and CO2 systems are compressed up to 32 and 120 GPa, respectively. The two radial axes for CO + O2 show the time and pressure for specific points of significance along the AIMD trajectory. d Change in average magnetic moment per oxygen atom and fraction of residual molecular O2 as a function of pressure. e Atomic arrangements from an AIMD trajectory showing the relative arrangements of CO and O2 molecules in the vicinity of O4 clusters, together forming the kinetic sphere.

The mean distance between atoms X (where X is C or O) and all first-neighboring Y atoms (C or O) inside their kinetic spheres, excluding the Y atom in its own molecule, is the X–Y kinetic diameter:

where NX is the total number of X atoms in the cell and NY,ks(i) is the total number of first-neighbor Y atoms inside the kinetic sphere of the ith X atom, but not bonded with it. During this computation, we ensure that the following condition is satisfied:

where \({\Omega }_{j}[\,={\cos }^{-1}({\varphi }_{j}/{r}_{shell})]\) is the subtended solid angle of the jth Y atom with respect to a shell of radius rshell. Here, the radial distance between the nth and n + 1th shells calculated radially outwards from the X atoms, \(\Delta {r}_{shell}[={r}_{shell,n+1}-{r}_{shell,n}]\), is the tunable parameter used to ensure that the total subtended solid angle is approximately equal to 4πsr.

The evolution of the C–O versus C–C kinetic diameters along an 864-atom AIMD compression trajectory spanning pressures from ambient to ~32 GPa during a 12.5 ps simulation is shown in Fig. 8c. Here \(t{\prime}\) and t″ are estimated at 0.5 ps and 7.6 ps, respectively, for the CO+O2 system. The resulting locus of points exhibits a Γ-shaped path. Note that a similar observation holds true even if just the nearest or the average of the first two to five neighboring atoms is used to define the diameter (see Supplementary Fig. S19).

The C–C polymerization happens just beyond ~7 GPa, which corresponds to the corner of this Γ-shaped path, where the average C–C diameter is minimized; presumably, the system overcomes the activation barrier for polymerization. Thereafter, as the C–C polymerization completes by ~9 GPa, relaxation of the C–O diameter is observed, most likely an effect of C–O polymerization, which completes by ~14 GPa. The cumulative simulation time needed for these two stages of polymerization is approximately 3 ps, which gives a benchmark for the time scales of bond rearrangement in such compressed carbon–oxygen systems. This is comparable to the experimentally observed timescales of 1–3 ps in both ionic as well as cyclic covalent compounds1–3.

In the case of CO2, a Γ-shaped path is not followed by the kinetic diameters, despite a simulation time of 10 ps, even though the system eventually reaches a four-coordinated amorphous structure. This highlights the fact that, although the CO+O2 mixture and CO2 are stoichiometrically equivalent, the dynamics of their reaction trajectories are completely different. The linear O=C=O molecules impose geometrical constraints on their approach to one another that are not present in the CO+O2 mixture, thereby inhibiting C–C bond formation.

Another observation is the local reaction environment inside the simulation cell. In a 2:1 CO:O2 mixture, the residual magnetic moment of oxygen in the cell is shown in Fig. 8d as a function of pressure. The average magnetic moment is 1.41μB at ambient and decreases with increasing pressure. This is consistent with an ample amount of free O2 molecules in the CO+O2 cell at lower pressures, including conditions where C–C and C–O bonds form. To visualize the effect of the residual O2, we look inside a kinetic sphere during a simulation. As shown in Fig. 8e, O2 molecules tend to aggregate into O4 clusters, which is similar to the ε phase of oxygen at comparable pressures4,5. They provide a local potential energy environment within which CO and other O2 molecules react to form C–C and C–O bonds. The elimination of such an environment inhibits polymerization. This shows that even though the mixture is stoichiometrically equivalent to the compound CO2, the local chemical environment during polymerization is completely non-stoichiometric.

Discussion

Density functional theory-based methods were used to predict a new, low-pressure way to synthesize a metastable, polymeric amorphous form of CO2 that can be recovered at ambient conditions and used as a high-energy-density material. Traditional methods for making fully 4-coordinated polymeric CO2 require extreme pressures (approximately 118 GPa), and the resulting phases revert to molecular CO2 when pressure is released at room temperature. In contrast, we propose compressing a mixture of CO and O2 (with a stoichiometry equivalent to CO2) along the 300K isotherm. This approach lowers the polymerization onset to about 7 GPa and achieves complete C–C polymerization by around 23 GPa, which is a significant reduction in the required pressure. When decompressed back to ambient pressure at 300 K, this polymeric phase remains stable with almost no change in bonding statistics, showing both mechanical and kinetic stability.

Constrained metadynamics searches identified two transient crystalline intermediates that are slightly favorable below 10 GPa but quickly become amorphous when compressed further. This confirms that the amorphous phase is the main product at higher pressures. Small amounts of unreacted O2 remain up to about 30 GPa, and later form oxygen chains that become part of the polymer without disrupting its structure. This effect increases the kinetic barriers and therefore enhances the metastability of the material.

Kinetic stability was further tested using two-phase AIMD simulations (624 atoms) for more than 8 ps, and large-scale MLMD simulations (15,600 atoms) for 100 ns. Both showed that the polymer and gas phases can coexist, with stable pressures (1.6–1.9 kbar) at room temperature and locked-in C, O frameworks. Unreacted O2 was able to diffuse out without causing the polymer to collapse. Phonon analysis showed no imaginary modes, confirming mechanical metastability. Both MLMD and two-phase NPT AIMD simulations also demonstrated that the amorphous polymer structure remains stable up to 700 K at ambient pressure before it begins to partially break down. A comparative analysis with the well-studied CO2 system shows that our approach successfully reproduces the experimentally observed stability of known polymeric-[CO2] phases, thereby validating our methodology.

Structural comparisons between recovered polymeric-[CO+O2] and conventional polymeric-[CO2] reveal key differences. Polymeric-[CO+O2] exhibits C-O, C=O, C-C, and O-O bonds forming complex chain-ring networks (including 5- and 6-membered rings), whereas polymeric-[CO2] consists mainly of three-coordinated –O(CO)– chains with minimal C–C or O–O bonding. Crystal Orbital Hamilton Population (COHP) analyses highlight unusually strong C=C π-π* and C–C σ-σ* interactions in polymeric-[CO+O2], indicating higher stored energy. Energetic metrics predict higher formation enthalpies (−204 to −243 kJ/mol), densities (2.04–2.34 g/cc), and volumetric energy densities (8.2–12.9 kJ/cc)—surpassing polymeric CO2 and rivaling TNT energetics.

If the prediction that compression of an initial metastable mixture lowers the onset of polymerization and yields kinetically robust HED materials is generally true, then this opens up opportunities to create and recover various energetic materials starting from initial mixtures of C, H, O, N compounds as the starting building blocks. To this end, we have provided Raman signatures of the relevant polymeric and amorphous phases in Supplementary Discussion 10 for aiding in experimentation.

Methods

Ab initio one-phase simulations

Ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations, utilizing the Born-Oppenheimer approximation59, with temperature being controlled via a Nosé-Hoover thermostat in a canonical (constant-NVT) or an isothermal-isobaric (constant-NPT) ensemble, form the backbone of the methods used in this paper.

The Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP)60,61,62 was used for such calculations, where 4- and 6-electron hard projector augmented wave (PAW) pseudopotentials were used for carbon and oxygen, respectively, with a 850 eV plane-wave cutoff energy for generalized gradient approximation (GGA)63 and 1000 eV for meta-GGA exchange-correlation functionals. Most of these calculations were performed using the Γ-point for sampling (resolution of at least <2π × 0.10 Å−1) the first Brillouin zone (1BZ), but for some cases, we used a single special k-point (1/4, 1/4, 1/4), as was introduced by Baldereschi64.

Supercells were used, with 108, 192, 216, 258, 432 and 864 atoms, with an ionic time step of 0.5–0.8 fs for AIMDs at ambient pressure and temperature. Cubic supercells were used to prevent a bias towards any non-amorphous structure. For equilibrating simulations along these compression and decompression paths, the combination of ionic step size and total number of steps was such that the total physical time for the simulation system was always more than 5 ps, exceeding 10 ps in pivotal cases (see Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 for complete list).

Oxygen was considered to be magnetic in all production simulations (see Supplementary Table S1) by utilizing spin-polarized calculations. This allows the converged ground-state solution to be the triplet (total spin S = 1) state, rather than the singlet state65.

The PBE (Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof) formulation52 of the GGA exchange-correlation functional was mostly used for the simulations. However, to check for the effects of climbing up Jacob’s ladder, as the sensitivity of reaction kinetic barriers to the nature of exchange-correlation is of utmost importance66,67, the SCAN (strongly constrained and appropriately normed)57 and SCAN-L56 meta-GGA functionals were also used. The hybrid functional HSE06 (Heyd-Scuseria-Ernzerhof)58 was also used for static tests. For van der Waals dispersion to be taken into account, the DFT-D3 [zero damping]47, DFT-D3 [Becke-Johnson damping]53, and the rVV10 (revised Vydrov-van Voorhis) non-local correlation functional54,55 were used. Thus, the combinations of PBE, PBE + D3[BJ], PBE + D3[0], PBE + rVV10, and SCAN-L + rVV10 were used for AIMD simulations, while PBE, SCAN, SCAN + rVV10 and HSE06 were used for single-point calculations at multiple snapshots along the compression and decompression AIMD trajectories.

The compression and decompression analysis of any system using NVT-AIMD simulations, starting with a gaseous mixture configuration at <0.1 kbar, involved a two-step approach. First, a fast compression trajectory was simulated using short simulations of 500 ionic steps at each volume along an isotherm, starting from ambient conditions. The volume was decreased by 1–2% at each point on the trajectory. Upon reaching the furthest point along the isotherm where complete pressure-induced polymerization is observed, equilibration simulations were performed for 5–10 ps, as described earlier (see Supplementary Table S1), at this furthest point as well as at intermediate points along the compression path for finding the resulting equilibrated ionic arrangement and constructing the equation of state. Second, for recovery, a fast decompression trajectory was similarly simulated with the volume being increased by 1–2% at each point on the trajectory. Equilibrating AIMD simulations of 5–10 ps were also performed at select points on the decompression trajectory to find the resulting equilibrated ionic arrangement and constructing the recovery equation of state.

Single-phase MLMD simulations were also performed using LAMMPS68 for ~ns timescale checks, and those can be found in Supplementary Discussion 3. Extensive discussion on Allegro69,70,71 training is also available in Supplementary Discussion 9.

Ab initio two-phase simulations

For the two-phase simulations, we performed a few cases with NVT ensemble while the rest were NPT ensemble simulations. In each of these cases, we started with cuboid supercells, with each side’s phase being well-equilibrated beforehand with respect to atomic arrangements using NVT simulations. The two-phase simulations used Baldereschi k-point for sampling, with 192 atoms for m-CO2∣ pa,rc[CO2], and 216 to 624 atoms (see Supplementary Table S2) for m-[CO+O2] ∣ pa,rc[CO+O2] systems respectively. Here, the symbol ∣ is used to denote each of the two phases on either side. Then, an AIMD simulation was performed on these merged cells with a time step of 0.5 fs, with a total simulation time exceeding 5 ps for all cases.

For the larger-scale 15,600-atom m-[CO+O2] ∣ pa,rc[CO+O2] and 11,520-atom m-CO2∣ pa,rc[CO+O2] two-phase NVT MLMD simulations, machine learned interatomic potentials (MLIPs) trained using Allegro69,70,71 were used to perform molecular dynamics simulations using LAMMPS68. The training was performed within the RMSE threshold of 5 meV/atom for energies and 50 meV/Å for forces.

Metadynamics

Constrained NPT-metadynamics calculations were performed, with the PBE + D3[0] exchange-correlation functional and the bias potential being constructed of fixed Gaussians, at each ρ,T point after constraining the C−O and O−O bond lengths at higher pressures to within 2.5% of ambient values (as observed in AIMD at corresponding pressures) and using the cell basis vectors (magnitude as well as angles) as collective variables. Cell sizes corresponding to 36- to 108-atoms were used for the simulations, in increments of 6 atoms (i.e., 2CO+O2). It is worth mentioning that, as a check, metadynamics simulations were also performed without constraining bond lengths, which yielded molecular crystal CO2-I as the stable solution. This is unphysical given the fact that at 300 K, the system’s thermal energy is insufficient for the reaction of CO and O2, even at 30 GPa.

Vibrational spectra

Phonon and Raman spectra calculations were performed in 108-atom cells with PBE + D3[0] functional, utilizing density functional perturbation theory (DFPT)72 calculations for the Born effective charge (BEC) tensor and Phonopy73 was utilized for evaluating the dynamical response of the system. Raman spectra were calculated (see Supplementary Discussion 10 for formulation) using this BEC tensor.

Data availability

Input, configuration, and trajectory files for compression and decompression pathways from VASP have been uploaded at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15027031 via GitHub upload at https://github.com/paulRqsg/COO2_data_dump.git, alongside raw data for the figures. Allegro MLIP and training details have been uploaded at https://github.com/paulRqsg/COO2_MLIP.git.

References

Novoselov, D. Y., Korotin, D. M., Shorikov, A. O., Oganov, A. R. & Anisimov, V. I. Weak Coulomb correlations stabilize the electride high-pressure phase of elemental calcium. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 32, 445501 (2020).

Ma, Y. et al. Transparent dense sodium. Nature 458, 182–185 (2009).

Neaton, J. & Ashcroft, N. Pairing in dense lithium. Nature 400, 141–144 (1999).

Hilleke, K. P., Bi, T. & Zurek, E. Materials under high pressure: a chemical perspective. Appl. Phys. A 128, 441 (2022).

Sundqvist, B. Carbon under pressure. Phys. Rep. 909, 1–73 (2021).

Datchi, F., Dewaele, A., Le Godec, Y. & Loubeyre, P. Equation of state of cubic boron nitride at high pressures and temperatures. Phys. Rev. B 75, 214104 (2007).

Goncharov, A. F. et al. Thermal equation of state of cubic boron nitride: implications for a high-temperature pressure scale. Phys. Rev. B 75, 224114 (2007).

Eremets, M. I., Gavriliuk, A. G., Trojan, I. A., Dzivenko, D. A. & Boehler, R. Single-bonded cubic form of nitrogen. Nat. Mater. 3, 558–563 (2004).

Peiris, S. M. & Piermarini, G. J. Static Compression of Energetic Materials (Springer, 2008).

Xu, Y. et al. Free-standing cubic gauche nitrogen stable at 760 K under ambient pressure. Sci. Adv. 10, eadq5299 (2024).

Bini, R., Ulivi, L., Kreutz, J. & Jodl, H. J. High-pressure phases of solid nitrogen by Raman and infrared spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 112, 8522–8529 (2000).

Eremets, M. et al. Polymerization of nitrogen in sodium azide. J. Chem. Phys. 120, 10618–10623 (2004).

Mattson, W. D., Sanchez-Portal, D., Chiesa, S. & Martin, R. M. Prediction of new phases of nitrogen at high pressure from first-principles simulations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 125501 (2004).

Gregoryanz, E. et al. High P-T transformations of nitrogen to 170 GPa. J. Chem. Phys. 126, 184505 (2007).

Pickard, C. J. & Needs, R. High-pressure phases of nitrogen. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 125702 (2009).

Yoo, C. et al. Crystal structure of carbon dioxide at high pressure: “Superhard” polymeric carbon dioxide. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 5527 (1999).

Bonev, S., Gygi, F., Ogitsu, T. & Galli, G. High-pressure molecular phases of solid carbon dioxide. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 065501 (2003).

Giordano, V. M., Datchi, F. & Dewaele, A. Melting curve and fluid equation of state of carbon dioxide at high pressure and high temperature. J. Chem. Phys. 125, 054504 (2006).

Santoro, M. et al. Amorphous silica-like carbon dioxide. Nature 441, 857–860 (2006).

Giordano, V. M. et al. Molecular carbon dioxide at high pressure and high temperature. Europhys. Lett. 77, 46002 (2007).

Iota, V. et al. Six-fold coordinated carbon dioxide VI. Nat. Mater. 6, 34–38 (2007).

Sun, J. et al. High-pressure polymeric phases of carbon dioxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 6077–6081 (2009).

Datchi, F., Giordano, V. M., Munsch, P. & Saitta, A. M. Structure of carbon dioxide phase IV: breakdown of the intermediate bonding state scenario. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 185701 (2009).

Giordano, V. M., Datchi, F., Gorelli, F. A. & Bini, R. Equation of state and anharmonicity of carbon dioxide phase I up to 12 GPa and 800 K. J. Chem. Phys. 133, 144501 (2010).

Santoro, M. et al. Partially collapsed cristobalite structure in the non molecular phase V in CO2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 5176–5179 (2012).

Datchi, F. et al. Structure and compressibility of the high-pressure molecular phase II of carbon dioxide. Phys. Rev. B 89, 144101 (2014).

Datchi, F., Moog, M., Pietrucci, F. & Saitta, A. M. Polymeric phase V of carbon dioxide has not been recovered at ambient pressure and has a unique structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, E656–E657 (2017).

Dziubek, K. F. et al. Crystalline polymeric carbon dioxide stable at megabar pressures. Nat. Commun. 9, 3148 (2018).

Gao, G. et al. Dissociation of methane under high pressure. J. Chem. Phys. 133, 144508 (2010).

Ninet, S. & Datchi, F. High pressure–high temperature phase diagram of ammonia. J. Chem. Phys. 128, 154508 (2008).

Ojwang, J., Stewart McWilliams, R., Ke, X. & Goncharov, A. F. Melting and dissociation of ammonia at high pressure and high temperature. J. Chem. Phys. 137, 064507 (2012).

Lipp, M. J., Evans, W. J., Baer, B. J. & Yoo, C.-S. High-energy-density extended CO solid. Nat. Mater. 4, 211–215 (2005).

Bonev, S., Lipp, M., Crowhurst, J. & McCarrick, J. Energetics of polymeric carbon monoxide. J. Chem. Phys. 155, 024108 (2021).

Scelta, D. et al. High temperature decomposition of polymeric carbon monoxide at pressures up to 120 GPa. J. Chem. Phys. 159, 084501 (2023).

Iota, V., Yoo, C. S. & Cynn, H. Quartzlike carbon dioxide: an optically nonlinear extended solid at high pressures and temperatures. Science 283, 1510–1513 (1999).

Datchi, F., Mallick, B., Salamat, A. & Ninet, S. Structure of polymeric carbon dioxide CO2-V. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 125701 (2012).

Iota, V. & Yoo, C.-S. Phase diagram of carbon dioxide: evidence for a new associated phase. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 5922 (2001).

Yoo, C.-S., Sengupta, A. & Kim, M. Phase diagram of carbon dioxide: update and challenges. High. Press. Res. 31, 68–74 (2011).

Cogollo-Olivo, B. H., Biswas, S., Scandolo, S. & Montoya, J. A. Ab initio determination of the phase diagram of CO2 at high pressures and temperatures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 095701 (2020).

Holm, B., Ahuja, R., Belonoshko, A. & Johansson, B. Theoretical investigation of high pressure phases of carbon dioxide. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 1258 (2000).

Kim, M., Ryu, Y. J., Lim, J. & Yoo, C.-S. Transformation of molecular CO2-III in low-density carbon to extended CO2-V in porous diamond at high pressures and temperatures. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 30, 314002 (2018).

Serra, S., Cavazzoni, C., Chiarotti, G., Scandolo, S. & Tosatti, E. Pressure-induced solid carbonates from molecular CO2 by computer simulation. Science 284, 788–790 (1999).

Tschauner, O., Mao, H. -K. & Hemley, R. J. New transformations of CO2 at high pressures and temperatures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 075701 (2001).

Montoya, J. A., Rousseau, R., Santoro, M., Gorelli, F. & Scandolo, S. Mixed threefold and fourfold carbon coordination in compressed CO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 163002 (2008).

Yong, X. et al. Crystal structures and dynamical properties of dense CO2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 11110–11115 (2016).

Brazhkin, V. V. Metastable phases, phase transformations, and phase diagrams in physics and chemistry. Phys. Uspekhi 49, 719 (2006).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Dronskowski, R. & Blöchl, P. E. Crystal orbital Hamilton populations (COHP): energy-resolved visualization of chemical bonding in solids based on density-functional calculations. J. Phys. Chem. 97, 8617–8624 (1993).

Deringer, V. L., Tchougréeff, A. L. & Dronskowski, R. Crystal orbital Hamilton population (COHP) analysis as projected from plane-wave basis sets. J. Phys. Chem. A 115, 5461–5466 (2011).

Maintz, S., Deringer, V. L., Tchougréeff, A. L. & Dronskowski, R. LOBSTER: A tool to extract chemical bonding from plane-wave based DFT. J. Comput. Chem. 37, 1030–1035 (2016).

Müller, P. C., Ertural, C., Hempelmann, J. & Dronskowski, R. Crystal orbital bond index: covalent bond orders in solids. J. Phys. Chem. C 125, 7959–7970 (2021).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1456–1465 (2011).

Peng, H., Yang, Z.-H., Sun, J. & Perdew, J. P. SCAN+rVV10: a promising van der Waals density functional. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1510.05712 (2015).

Román-Pérez, G. & Soler, J. M. Efficient implementation of a van der Waals density functional: application to double-wall carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 096102 (2009).

Mejia-Rodriguez, D. & Trickey, S. Deorbitalization strategies for meta-generalized-gradient-approximation exchange-correlation functionals. Phys. Rev. A 96, 052512 (2017).

Sun, J., Xiao, B. & Ruzsinszky, A. Communication: effect of the orbital-overlap dependence in the meta generalized gradient approximation. J. Chem. Phys. 137, 051101 (2012).

Becke, A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. I. The effect of the exchange-only gradient correction. J. Chem. Phys. 96, 2155–2160 (1992).

Born, M. & Heisenberg, W. Zur quantentheorie der molekeln. Original Scientific Papers Wissenschaftliche Originalarbeiten 216–246 (1985).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Atoms, molecules, solids, and surfaces: applications of the generalized gradient approximation for exchange and correlation. Phys. Rev. B 46, 6671 (1992).

Baldereschi, A. Mean-value point in the Brillouin zone. Phys. Rev. B 7, 5212 (1973).

Freiman, Y. A. Magnetic properties of solid oxygen under pressure. Low. Temp. Phys. 41, 847–857 (2015).

Kaplan, A. D., Shahi, C., Bhetwal, P., Sah, R. K. & Perdew, J. P. Understanding density-driven errors for reaction barrier heights. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 19, 532–543 (2023).

Kanungo, B., Kaplan, A. D., Shahi, C., Gavini, V. & Perdew, J. P. Unconventional error cancellation explains the success of Hartree–Fock density functional theory for barrier heights. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 15, 323–328 (2024).

Thompson, A. P. et al. Lammps-a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 271, 108171 (2022).

Tan, C. W. et al. High-performance training and inference for deep equivariant interatomic potentials. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2504.16068 (2025).

Musaelian, A. et al. Learning local equivariant representations for large-scale atomistic dynamics. Nat. Commun. 14, 579 (2023).

Kozinsky, B., Musaelian, A., Johansson, A. & Batzner, S. Scaling the leading accuracy of deep equivariant models to biomolecular simulations of realistic size. In Proc. International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis 2, 1–12 (2023).

Baroni, S., De Gironcoli, S., Dal Corso, A. & Giannozzi, P. Phonons and related crystal properties from density-functional perturbation theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 73, 515 (2001).

Togo, A. First-principles phonon calculations with Phonopy and Phono3py. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 92, 012001 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank C.S. Yoo for discussions. This work was performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) under contract number DEAC52-07NA27344. The authors acknowledge funding support from the DOE Laboratory Directed Research and Development (LDRD) program at LLNL under the project tracking code 23-ER-028.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C.C. and S.A.B. designed research; R.P. performed research; S.A.B. supervised research; R.P. and S.A.B. wrote the paper; J.C.C. provided guidance; all authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Ding Pan and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Paul, R., Crowhurst, J.C. & Bonev, S.A. Prediction of an alternative high-pressure route to polymeric carbon dioxide as a metastable energetic material. Commun Chem 9, 5 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01802-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01802-w