Abstract

Phase separation is fundamental to cellular organization, yet early events driving this process remain poorly characterized. ATP is highly concentrated in platelet dense granules, where it coexists with divalent cations. Here, we reconstitute ATP phase separation and use nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) to discover a 1:2 stoichiometric complex between Mg2+ and ATP. Using a modified NMR pulse sequence of diffusion-ordered spectroscopy (DOSY), we accurately evaluate the size of Mg2+–ATP nanoclusters, and identify them as pre-transitional intermediates that grow in hydrodynamic radius at increasing Mg2+ concentration. Excess Mg2+ beyond the specific ratio promotes hydration and charge neutralization of the nanoclusters, resulting in the formation of a system-spanning network. The process is characteristic of phase separation coupled to percolation, a mechanism further validated by complementary techniques. Our work reveals how stoichiometric imbalance between interacting components regulates phase transition kinetics and dictates the physical properties of the resulting condensate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) is a fundamental mechanism underlying the formation of membraneless organelles (MLOs)1,2,3. These dynamic compartments enable cells to spatially organize biomolecules for functions like molecular partitioning4,5,6 and concentration buffering7. MLOs may also coexist within membraned organelles8,9, where active transport elevates solute concentrations, thereby promoting phase separation. This interplay is exemplified by secretory granules in chromaffin cells, where condensates form within the vesicles but disperse rapidly upon membrane fusion10,11.

The thermodynamic driving force for phase separation is a decrease in the Gibbs free energy (ΔG < 0), which enables spontaneous condensation when the solute concentration exceeds a critical threshold (Csat). However, thermodynamics alone does not capture the kinetic pathways or energy barriers involved in the process, and macroscopic phase transitions may obscure microscopic events not directly observable by conventional microscopy. In processes such as crystallization, nucleation constitutes a well-defined, rate-limiting step that precedes energetically favorable growth and the incorporation of additional molecules12. Whether liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) proceeds through discrete intermediate states remains an open question, largely due to the experimental challenges in capturing such transient species, while the exact mechanism also depends on the system under study13.

In binary or multiple-component systems that undergo phase separation, stoichiometry is a key determinant of condensate formation and stability. This has been well-characterized in systems comprising RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) and their associated RNA, which engage in both specific and non-specific interactions. Typically, an optimal window for condensation emerges near charge neutrality, where positive charges on proteins are balanced by negative charges on RNA14,15. An excess of either component can lead to reentrant phase behavior, characterized by the dissolution of the condensed phase16,17,18,19. On the other hand, condensates can mature through a process of phase separation coupled to percolation, in which the formation of solute-dense droplets precedes and templates the development of a percolated network within them, leading to a system-spanning gel13. This process can result in hysteresis or kinetic arrest, transitioning the molecular assembly from fluid to a gel or solid-like state19,20,21,22.

Studying the phase separation of small molecule systems provides a simplified framework for elucidating the kinetic processes and assembly pathways that may be obscured in macromolecular systems. Previous studies have shown that small molecules such as simple peptides and oligonucleotides can spontaneously form liquid-like condensates, preceding the emergence of more ordered structures like fibrils or crystals23,24,25,26. In this study, we investigate the phase separation behavior of ATP in the presence of divalent cations, specifically Mg2+ and Ca2+. Physiologically, ATP concentrations exceeding 500 mM, along with high concentrations of ADP, 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), and divalent cations, are found in dense granules (δ-granules, ref. 27), the specialized secretory vesicles in platelets. Within these vesicles, electron-dense ATP condensates occupy a sub-volume, implying membraneless condensates28,29. Interestingly, the ionic composition of dense granules varies between species, e.g., high Ca2+ in humans vs. high Mg2+ in rodents and pigs30, and by pathological states, e.g., elevated Mg2+ levels in atopic dermatitis patients31.

Our findings demonstrate that the material properties of ATP condensates are governed by the identity of the coordinating divalent cation. In the presence of Mg²⁺, we uncover a hierarchical assembly pathway in which stable nanoclusters—comprising thousands of ATP molecules—act as metastable intermediates en route to a macroscopic, viscoelastic condensed phase. The identification of these nanoclusters as key assembly intermediates demonstrates that small molecules such as ATP can also undergo phase separation coupled to percolation (PSCP).

Results

Mg²⁺ induces the formation of percolated, gel-like ATP condensates

We reconstituted the phase separation system of Mg2+-ATP in vitro, forming a translucent phase with gel-like, viscoelastic properties (Supplementary Fig. 1), consistent with previous reports27,30,32. Demixing occurred at ATP concentrations exceeding 0.6 M and Mg2+ concentrations above 0.9 M (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Notably, the phase boundary remained nearly unchanged when the pH was shifted from 5.4—mimicking the acidic environment in dense granules—to 7.0 (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Given that the triphosphate moiety of ATP carries more negative charge at pH 7.0, the results suggest that Mg2+ promotes ATP phase separation through a mechanism that is not simply electrostatic neutralization.

To dissect the molecular forces governing condensation, we replaced ATP with ADP, another abundant molecule in platelet dense granules. This substitution shifted the phase boundary, lowering the required nucleotide concentration (Supplementary Fig. 2c). However, phase separation still required an excess of Mg2+ beyond this 1:1 ratio, with redissolution occurring at Mg2+ concentrations exceeding a 1.5:1 stoichiometry. Congruently, the addition of 5-HT (Supplementary Fig. 1c) lowered the Mg2+ concentration required for ATP phase separation (Supplementary Fig. 2d). On the other hand, lowering the temperature expanded the boundaries of the dense phase (Supplementary Fig. 2e, f), characteristic of an upper critical solution temperature (UCST) behavior. Thus, the phase separation process should be enthalpically driven, with energetic contributions from Mg2+-ATP coordination, electrostatic neutralization, as well as π-stacking of adenine bases.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) revealed that the Mg2+–ATP condensates form a percolated, fractal-like network of interconnected filaments, with the finest filaments measuring 10–20 nm in diameter (Fig. 1a). Such architecture likely accounts for the observed viscoelastic properties—with the storage modulus G′ greater than the loss modulus G″ and the upper limit of the linear regime (γLVE) of 0.237% in the typical range for hydrogels (Fig. 1b), Mg2+-ATP condensate is thus characteristic of a weak, non-covalently cross-linked network.

a Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image showing the percolated filamentous network of the hydrogel. Inset: Magnified view of the filaments, with the meshes pseudo-colored to indicate depth. b Viscoelastic properties of the hydrogel. The storage modulus (G′) exceeds the loss modulus (G″), and the upper limit of the linear viscoelastic region (LVER) is indicated.

In contrast to the gel-like behavior observed with Mg2+, substitution with Ca2+ led to the formation of a white, solid precipitate (Supplementary Fig. 1). This precipitation occurred under less stringent stoichiometric conditions and proceeded even when Ca2+ was present in sub-stoichiometric amounts relative to ATP (Supplementary Fig. 3a). SEM revealed that the Ca2+-ATP assemblies consist of monodisperse and uniform nanoparticles with an average diameter of 190 ± 12 nm (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Thus, the divalent cation not only dictates phase separating conditions and macroscopic appearance, but also the nanoscale architecture. For monovalent ions (Na⁺ or K⁺) could induce ATP condensation, even at concentrations as high as 2.4 M, no phase separation was observed (Supplementary Fig. 4), further demonstrating that charge screening is not the sole determinant of ATP condensation.

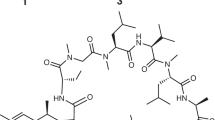

NMR spectroscopy reveals the formation of well-defined Mg²⁺-ATP assembly

To elucidate how divalent cations drive ATP phase separation, we performed NMR titrations on an ATP sample with increasing amount of Mg2+. The resulting 31P chemical shift exhibited significant downfield perturbations for both γ- and β-phosphorous nuclei (Fig. 2a, b and Supplementary Table 1), implying direct coordination of Mg2+ to and consequently magnetically de-shielding of the terminal phosphate groups. Global fitting of the chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) for both γ- and β-phosphorous nuclei yielded a stoichiometry of one Mg2+ ion per two ATP molecules (N = 0.5) and a dissociation constant (KD) of (7.06 ± 1.49) × 10−2 M0.5 (Fig. 2c). The values were consistent with the individual fits for each nucleus (Supplementary Fig. 5), confirming that both phosphate groups participate in the same Mg2+ coordination event.

a, b 1D 31P NMR spectra showing chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) for the γ- and α-phosphorus nuclei a, and the β-phosphorus nucleus (b), colored from blue to red, at increasing Mg2+ concentration. The peaks of γ- and β-phosphorus, but not α-phosphorus, shift monotonically downfield. Line broadening and multiplet degeneration are also observed at increasing Mg2+ concentration. c Global fitting of the CSPs for the γ- and β-phosphorus nuclei as a function of Mg2+ concentration yields a binding stoichiometry of N = 0.5 and a dissociation constant KD = (7.06 ± 1.49) × 10−2 M0.5. d, e Snapshots from MD simulations of Mg2+–ATP complexes. Panel (d) illustrates metal coordination and (e) illustrates adenosine stacking. For clarity, protons and water molecules are omitted.

The α-phosphorus resonance experienced much smaller CSPs and exhibited a non-monotonic response upon Mg2+ titration (Fig. 2a). It initially shifted downfield like γ- and β-phosphorus, but upfield as Mg2+ concentrations exceeded 0.4 M. This biphasic behavior suggests a secondary, weaker interaction that affects its chemical environment at higher Mg2+ concentrations.

No reliable fitting could be achieved for the 1H resonances of ATP base and sugar (Supplementary Fig. 6), supporting the model in which Mg2+ preferentially coordinates with ATP phosphate groups (Fig. 2d, e). Notably, the addition of Mg2+ caused significant line broadening in both 31P and 1H spectra. In particular, the well-resolved 31P J-coupling multiplets observed in the absence of Mg2+ collapsed into single broad peaks upon Mg2+ titration (Fig. 2a, b). The broadening of ATP resonances indicated enhanced transverse relaxation upon the formation of large assemblies with slow tumbling on the NMR timescale.

To assess the specificity of this assembly process, we performed parallel titrations with Ca2+ into ATP. While Ca2+ induced 31P CSPs of comparable magnitude to those observed with Mg2+, the perturbations lacked inflection points (Supplementary Fig. 7), indicating weaker and presumably non-cooperative binding. Furthermore, Ca2+ did not induce significant line broadening, implying that ATP remaining in solution is predominantly monomeric or small oligomers.

Together, NMR titration data reveal that Mg2+ and ATP co-assemble into stoichiometrically defined clusters of a very large molecular weight, a behavior not reproduced by Ca2+, highlighting a cation-specific mechanism of ATP condensation.

Excess Mg2+ induces hydration of ATP nanoclusters

To further characterize the molecular properties of Mg2+-ATP nanoclusters, we performed NMR DOSY measurement for ATP with increasing Mg2+ concentrations. Initially, elevation of Mg2+ led to a progressive decrease in the translational diffusion coefficient (D) of ATP, corroborating the formation of large clusters. However, when Mg2+ concentration exceeded 0.5 M, the signal decay curves as a function of pulse field gradient strength significantly deviated from mono-exponential behavior (Supplementary Fig. 8a).

A bi-exponential fit of the DOSY curves revealed two distinct species: a fast-diffusing component (Dfast ≈ 3.2 × 10−10 m2•s−1) and a slow-diffusing component (Dslow). The Dslow decreased progressively with increasing Mg2+ concentration, reaching approximately 1/20 of Dfast at the highest Mg2+ concentration (Supplementary Table 2), indicating the formation of larger ATP nanoclusters at higher Mg2+ concentration. In contrast, Dfast remained largely constant for different ATP proton signals over a range of Mg2+ concentrations (Supplementary Table 2), whereas the fractional contribution of the fast-diffusing component increased with Mg2+ concentration (Supplementary Fig. 8b). Intriguingly, Dfast was significantly lower than the diffusion coefficient of free ATP in dilute solution (~3.7 × 10−10 m2•s−1, refs. 33,34), ruling out free ATP as the fast-diffusing component.

We hypothesized that the anomalous Dfast component originated from water molecules interacting with ATP nanoclusters through chemical exchange or NOE. This was supported by multiple lines of evidence. First, the fractional contribution of the Dfast component to DOSY signal decay increased at longer diffusion delays implemented in the NMR pulse sequence (Supplementary Fig. 9a), a characteristic feature of magnetization transfers rather than true molecular diffusion. Second, as the diffusion delay increases, ribose protons (H2′, H3′, H4′, H5′) exhibited earlier onset of significant Dfast contribution compared to H8, H2, and H1′ (Supplementary Fig. 9b), indicating an additional relaxation mechanism—possibly mediated by adjacent hydroxyl groups through solvent exchange. Third, water-NOE experiments by selective inverting solvent resonance confirmed interactions between water and ATP protons in the clusters, and the NOE buildup became faster and more pronounced at higher Mg2+ concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 9c). Together, our data support a structural model in which Mg2+, when present in excess of 2:1 stoichiometry with ATP, promotes the hydration of ATP nanoclusters.

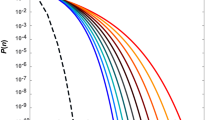

The Dfast value was approximately 1/2 of the value measured for bulk water measured for the same ATP sample (~7 × 10−10 m2•s−1, Supplementary Table 2), implying that the fast-diffusing species corresponds to water molecules loosely associated with ATP nanoclusters rather than freely diffusing bulk solvent. To eliminate the interference from hydrated species, we modified DOSY pulse sequence by incorporating a water-selective excitation pulse followed by a purge gradient to dephase water magnetization prior to the stimulated echo (STE) block. Additionally, continuous-wave irradiation was applied between the encoding and decoding STE blocks to suppress magnetization transfer from water to solute signals (Supplementary Fig. 10a, b). This revised sequence afforded a clean mono-exponential NMR signal decay across all Mg2+ concentrations, when plotted against gradient strength or diffusion delay (Supplementary Fig. 10c and Fig. 3a). Moreover, the diffusion coefficients obtained with the modified pulse sequence are consistent with the Dslow values from the bi-exponential fits using the standard DOSY pulse sequence. Yet, given the systematic and larger residuals associated with those bi-exponential fits (Supplementary Fig. 11), the modified pulse sequence effectively eliminates contributions from water interference, regardless of the underlying mechanism, and excels in providing more accurate translational diffusion rates of ATP nanoclusters (Fig. 3b).

a Using the modified DOSY pulse sequence, H8 NMR signals for the Mg2+–ATP system are plotted on a logarithmic scale as a function of the square of the Z-gradient strength. Across a range of Mg2+ concentrations up to 0.8 M, the data are well described by single-exponential decays. b Translational diffusion coefficients measured at increasing concentrations of Mg2+ or Ca2+. Arrows, in three different colors, indicate metal concentrations at which phase separation or precipitation begins to appear for each system. In the Mg2+–ATP samples, 0.1 M 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) was included. All measurements were performed using 0.7 M ATP at 298 K and pH 5.4.

We also assessed the diffusion behavior of 5-HT and elucidated its interactions within the condensates. While the addition of 5-HT lowers the concentration threshold for Mg2+–ATP phase separation, its diffusion, monitored by the non-labile 5-HT H2 resonance (Supplementary Fig. 1c), was consistently faster than that of ATP (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 12a). This means that 5-HT retains partial mobility when sequestered in Mg2+-ATP condensates.

On the other hand, Ca2+-ATP systems showed little deviation from mono-exponential decays, regardless of the pulse sequence, diffusion delay in the pulse sequence, or cation concentration (Supplementary Fig. 12b), implying the absence of hydration or minimal interference from associated water molecules. Nevertheless, diffusion coefficient as a function of Ca2+ concentration closely matches that of Mg2+ concentration (Fig. 3b).

Using these measured values, we could estimate the size of the Mg2+-ATP nanoclusters. Considering the ~40-fold reduction in D relative to bulk water in the same sample (Supplementary Table 2) and assuming hydrodynamic similarity, each cluster should have molecular weight over 1 MDa and contain over 2000 ATP molecules.

Coalescence of Mg2+-ATP nanoscale condensates leads to macroscopic phase separation

To elucidate what occurs as excess Mg2+ results in the hydration of ATP nanoclusters, we performed 31P dark-state exchange saturation transfer35,36,37 (DEST) experiments. Using 31P rather than 1H NMR allowed us to minimize complicating effects from NOE and chemical exchange and to obtain a clear picture of the invisible, high-molecular-weight species that led up to macroscopic phase separation.

In pure ATP solutions (0.7 M, pH 5.4, 298 K), no dark state was detected (Supplementary Fig. 13a). The addition of 0.35 M Mg2+ resulted in mild broadening of the DEST profiles collected at two RF fields (Supplementary Fig. 13b), but a minor species could not be confidently modeled. Only when we increased Mg2+ concentration to 0.7 M, we could observe much broadened DEST profiles and fit the dark state (Fig. 4a). Individual fittings of the α- and β-phosphorus DEST profiles indicated the presence of a dark state with comparable parameters, a feature not observed for the γ-phosphorus (Supplementary Table 3). This suggests that the α- and β-phosphorus atoms directly participate in a common chemical exchange process associated with clustering and aggregation, but not the γ-phosphorus. This finding contrasts with the pattern observed in concentration-dependent chemical shift perturbations (Fig. 2). Global fitting of α- and β-phosphorus yielded a minor state population of <4%, with a transverse relaxation rate (R2,B) ~ 15 times of that of the major state (R2,A) and an exchange rate (kex) of ~80 s−1.

From left to right, DEST profiles of 31P for the α-, β-, and γ-phosphorus nuclei of 0.7 M ATP, acquired at radiofrequency (RF) field strengths of 150 Hz (red) and 300 Hz (cyan), in the presence of (a) 0.7 M Mg2+ and (b) 0.35 M Ca2+. Global fitting of the α- and β-phosphorus profiles (black lines) yields exchange rate of 82.4 ± 22.4 s−1 and dark-state population of 3.7 ± 1.0% for Mg2+, and 187 ± 22 s−1 and 0.87 ± 0.09% for Ca2+.

In parallel, we performed DEST experiments on the Ca2+–ATP system and detected dark-state exchange at 0.35 M Ca2+ concentration, near the threshold concentration for macroscopic phase separation. The dark state was populated at ~1%, with R2,B ~ 50 times of R2,A and a kex of ~180 s−1 (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 4). Notably, the DEST profiles for Ca2+–ATP are much sharper than those of Mg2+-ATP at the same concentration. This can be attributed to the smaller population of the dark state in the Ca2+-ATP system, as well as the faster exchange with the dark state. Notably, the R2 values of the NMR-visible state of Ca2+-ATP are ~1/10 of those in the Mg2+-ATP system, indicating that Ca2+–ATP form only small clusters before coalescing into large particles.

Together, the DEST analyses indicate that the dark state corresponds to large, slow-tumbling assemblies. As increasing Mg2+ further neutralizes the negative charges of ATP, its clusters can percolate and form a viscoelastic network. Based on the DOSY data, we estimate the molecular weight of Mg2+–ATP nanoclusters to exceed 1 MDa. This corresponds to a size of 10 nm in diameter, and is consistent with the filament thickness observed by SEM.

Independent validation of the phase separation coupled to percolation process

We employed complementary techniques to characterize the ATP nanoclusters and monitor the subsequent phase transition. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements on ATP solutions revealed a Mg2+-dependent increase in nanocluster size (Fig. 5a, b). Notably, at each Mg2+ concentration below the macroscopic phase separation threshold, the system remained homogeneous indefinitely. At 0.50 M MgCl2, the hydrodynamic diameter was approximately 14 nm, consistent with the size estimated using NMR. The cluster size increased rapidly at higher Mg2+ concentration, reaching ~140 nm at 0.80 M MgCl2. Although the absolute sizes measured by DLS were larger than those estimated by DOSY—likely reflecting the higher sensitivity of DLS to larger aggregates—the consistent growth trend confirms the Mg2+-dependent stabilization and expansion of ATP clusters.

a, b Dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis for an ATP sample (0.70 M). a Size distribution profiles of Mg2+–ATP assemblies at increasing Mg2+ concentrations (colored blue to dark red, 0.25, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.75, 0.80 M). b Hydrodynamic diameter of the predominant population (mean ± s.d., n = 3 measurements) as a function of Mg2+ concentration. Nanoclusters remained stable at each concentration without macroscopic phase separation, though increased size dispersion was observed at 0.80 M Mg2+. c–f Real-time observation of phase separation via temperature-jump SIM. Time-lapse bright-field images show rapid condensate formation at 2.6 s, 2.8 s, 4.8 s, and 10 s after cooling to room temperature. The mature droplets exhibit internal structural heterogeneity, consistent with network formation, though percolated connectivity is beyond SIM resolution.

We next sought to visualize the transition from nanoclusters to a macroscopic condensed phase. Using a temperature-jump approach based on the system’s upper critical solution temperature (UCST) behavior (Supplementary Fig. 2), we monitored coacervation in real time with the use of structured illumination microscopy (SIM). The sample—composed of 0.7 M ATP and 0.9 M Mg2+ and capable of phase separation at room temperature—was briefly heated to dissolve condensates and then cooled on the microscope stage. Upon cooling, sub-micron droplets rapidly formed throughout the field of view (Fig. 5c–f). These droplets subsequently fused, and macroscopic turbidity developed within seconds. Although SIM cannot resolve molecular connectivity, the non-homogeneous internal structure of the droplets suggests the formation of a networked structure.

To probe the material properties of the mature condensates, we performed fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP), with the doping of a fluorescent ATP analog (Supplementary Fig. 14). The measured bulk diffusion coefficient (Dbulk = (3.63 ± 0.24) × 10−14 m2•s−1) is comparable to values reported for protein condensates38, but lower than those characteristic of gel-like RNA-protein19 or RNA-only condensates39,40,41. Given the small size of ATP, this severely restricted mobility—even after accounting for increased viscosity—strongly supports the formation of a percolated network in a gel-like condensed phase.

On the other hand, Ca2+ forms stronger, water-excluded complexes with ATP42,43 and the resulting assemblies are markedly different (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Moreover, incomplete charge neutralization would lead to electrostatic repulsion and self-limiting assembly, as manifested by uniformly sized nanoparticles under SEM.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that ATP phase separation in the presence of Mg2+ is not a simple, direct process but proceeds through transient intermediate states, in which Mg2+ and ATP first form stoichiometrically well-defined nanoclusters. In contrast, stronger but less specific binding of Ca2+ to ATP bypasses the intermediate state and directly form macroscopic precipitation. Thus, the differences in assembly pathway and physical property of the condensed phase hinge on a delicate balance in interaction strength between the components.

The Mg2+-ATP nanoclusters represent pre-transitional intermediates, analogous to metastable liquid clusters previously observed in protein solutions44. The stability of the nanoclusters imposes an energetic barrier that must be overcome prior to coalescence into a macroscopic phase: The formation of 1:2 Mg2+-ATP complexes satisfies local binding requirements, but hinders progression toward a globally stable, phase-separated state (Fig. 6). This behavior expands the repertoire of physicochemical properties and biological roles associated with ATP45,46,47. In contrast, Ca2+ forms stronger, less hydrated complexes with ATP42,43, and proceeds via a more direct, thermodynamically favorable pathway that lacks a well-defined stoichiometric intermediate. Incomplete charge neutralization results in electrostatic repulsion, leading to self-limiting assembly and the formation of uniformly sized nanoparticles, as observed by SEM. This behavior is characteristic of a short-range attraction and long-range repulsion (SALR) interaction as documented48.

The diagram depicts the progression of assembly with increasing Mg2+ concentration and effective charge neutralization. As the saturation concentration (Csat) is lower than the percolation threshold (Cperc), the system undergoes phase separation coupled to percolation (PSCP), wherein the hydrated Mg2+–ATP nanoclusters act as precursor assembly intermediates prior to macroscopic phase separation. This hierarchical pathway determines the resulting condensate’s morphology and viscoelastic properties.

A key finding in the present study is that the addition of Mg2+ beyond the 1:2 stoichiometric ratio drives the transition to a macroscopic phase. Excess Mg2+ neutralizes the negative charges on the ATP nanoclusters, reducing electrostatic repulsion and enabling percolation into a continuous, system-spanning network. This extra “coating” of ATP clusters likely reflects Mg2+‘s preference for coordinating with water over phosphate groups42. At the atomic level, DEST analysis revealed that the α- and β-phosphorus nuclei undergo a common exchange process into a larger, NMR-invisible state, a transition that likely involves additional adenosine stacking and reorientation of the glycosidic bond. Importantly, the estimated diameter of the ATP nanoclusters (~10 nm) matches the filament thickness observed in the macroscopic hydrogel, suggesting these nanoclusters serve as the fundamental building blocks of the emergent network. This hierarchical assembly pathway exemplifies phase separation coupled to percolation (PSCP), a mechanism recently proposed for macromolecular systems13,21. In PSCP, the saturation concentration (Csat) is lower than the percolation threshold (Cperc). Here, Csat corresponds to the condition for forming the metastable ATP nanoclusters, while Cperc is defined by the excess Mg2+ required to trigger network formation.

This assembly process shares conceptual parallels with the maturation of RNA–protein condensates, which often culminate in irreversible gelation via multivalent crosslinking19. Similarly, polyphosphate-scaffolded phase transitions can lead to mature states with hysteresis18,49. In contrast, the Mg2+–ATP condensate can be readily redissolved upon dilution, owing to the weak, interactions among the nanoclusters. Additionally, the porous hydrogel network is capable of sequestering water and small molecules such as serotonin (5-HT), which retain partial mobility (Fig. 3b). Thus, the Mg2+–ATP phase transition not only illustrates a novel assembly mechanism but also provides a plausible model for the function of platelet dense granules in concentrating and releasing bioactive molecules in a rapid, controlled manner50,51.

While the Mg2+–ATP system is a simplified model, the metastable nanocluster intermediates uncovered here have broad implications. These nanoclusters are not merely transient species but act as critical regulatory checkpoints that can either promote or arrest the phase separation process. By governing assembly kinetics and dictating the final condensate morphology, these intermediate states play a decisive role in determining the functional outcome of the phase transition.

Methods

Preparation of ATP condensed phase

For the assessment by SEM and rheological measurements, a 1 M stock solution of adenine nucleotide (ATP or ADP, Macklin) was mixed with the appropriate volume of 4 M MCl2 (M = Mg or Ca) and ddH2O at 298 K, adjusted to pH 5.4 (or pH 7), to achieve final concentrations of 0.7 M nucleotide and 1.2 M divalent cation. After vortexing, whitish suspension formed, which settled at 298 K for 24 hours.

To determine phase separation boundaries, stock solutions of adenine nucleotide were diluted to the desired concentrations with ddH2O. Then, 44 M MCl2 (M=Mg, Ca) was added to a final volume of 500 μL. The mixtures were vortexed thoroughly and incubated at 298 K for at least 24 h to allow phase separation to take place and reach equilibrium. Additionally, 5-hydroxytryptamine hydrochloride (Macklin) was added from a 0.143 M stock solution to the desired final concentration.

SEM characterization

The morphology of ATP condensates was examined using a Merlin Compact scanning electron microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany) operated at an accelerating voltage of 2 kV for Mg2+-ATP system and 5 kV for Ca2+-ATP system. Images were acquired at magnifications ranging from 18,050 to 36,610×. For Mg2+-ATP samples, a drop of the condensed phase was deposited onto a silicon nitride film; for Ca2+-ATP samples, a drop of the aqueous suspension was directly loaded onto a silicon nitride wafer.

Rheological characterization of the condensed phase of Mg2+-ATP

Rheological measurements were performed using a rotational parallel-plate rheometer (MCR301, Anton Paar, Austria) equipped with a cylindrical PP08 spindle (8 mm diameter). Experiments were conducted at 25 °C. Strain-sweep tests were performed in triplicate, with strain amplitudes ranging from 0.01% to 100% at a constant oscillation frequency of 1 Hz. The storage modulus (G’) and loss modulus (G”) were plotted using OriginPro. The linear viscoelastic region (LVER) was identified as the point at which both G’ and G” began to deviate from their plateau values, in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines.

Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) measurements

A stock solution of 1.00 M disodium ATP (pH 5.4) and a 4.00 M MgCl2 solution (pH 5.4) were prepared using ultrapure water (ddH2O). Both stock solutions were filtered through a 0.45 μm aqueous-phase filter to remove large particulate contaminants. For each sample, 700 μL of the 1.00 M ATP solution was mixed with an appropriate volume of the 4.00 M MgCl2 solution. The mixture was then diluted with ddH₂O to a final volume of 1000 μL, yielding final Mg2+ concentrations of 0.00, 0.25, 0.50, 0.60, 0.70, 0.75, and 0.80 M, with the ATP concentration fixed at 0.70 M.

A 1 cm × 1 cm disposable plastic cuvette was filled with 700 μL of the sample. DLS measurements were performed on a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS90 instrument at 25 °C. The viscosity of pure water at 25 °C was used for data analysis. The attenuator position and measurement duration were automatically optimized by the software, with the measured attenuation index consistently maintained at a relative value of 11 for all samples to ensure comparable scattered light intensities. Each sample was measured in triplicate. The mean hydrodynamic diameter of the predominant population (Peak 1) is reported. Under the constant measurement geometry and attenuation index applied, the derived scattering intensity is proportional to the size of the nanoclusters.

Real-time observation of condensate formation via structured illumination microscopy (SIM)

A Mg2+-ATP sample exhibiting phase separation at room temperature was prepared by mixing 350 μL of 1.00 M disodium ATP solution (pH 5.4) with 112.5 μL of 4.00 M MgCl2 solution (pH 5.4) and 37.5 μL of ultrapure water (ddH₂O). The resulting turbid mixture clarified upon warming, for instance, by hand.

For imaging, a 10 μL aliquot of the suspension was placed on a glass-bottom dish. The dish was positioned on the metal stage of a super-resolution microscope (in the laboratory of Prof. Xi Peng, College of Engineering, Peking University), which was integrated with an environmental chamber. The sample was heated to 45 °C until the turbidity disappeared completely. The sample was then immediately translated to the observation position under a 60× oil-immersion objective without further focusing. Phase separation was re-induced by allowing the sample to cool naturally to room temperature. This temperature-jump (T-jump) process was monitored in bright-field mode with images acquired every 200 ms for a duration of 1 minute.

FRAP measurement

The fluorescent probe TNP-ATP (APExBIO) was added to the ATP solution at a final concentration of approximately 0.2% relative to ATP. A freshly prepared Mg2+–ATP gel—obtained by gentle vortexing and low-speed centrifugation to form a macroscopic condensed phase—was transferred onto a coverslip, sealed, and imaged using a Leica Stellaris 5 confocal microscope. Given the macroscopic, system-spanning nature of the condensed phase, conventional whole-droplet bleaching was not applicable. Instead, a small circular region of interest (ROI) was selected within the gel for partial bleaching; the use of a small ROI within a macroscopic gel ensured that recovery reflected internal rearrangements rather than exchange with a surrounding dilute phase. Prior to photobleaching, baseline fluorescence intensity was recorded every 2.624 s for 10 frames. Photobleaching was performed using 20 pulses of a 488 nm laser within a minimized time window. Fluorescence recovery was subsequently monitored by acquiring images every 2.583 s. FRAP measurements were repeated in multiple distinct regions of the Mg2+–ATP gel to ensure reproducibility.

Post-bleach recovery curves were analyzed using the established protocol52,53, consisting of a two-part approach. The first involved calculating diffusion time (\({\tau }_{D}\)) by fitting the fluorescence intensity–time curve using a model based on a Gaussian laser beam profile, as given in Eq. (1). In this model, \({F}_{{pre}}\) and \({F}_{0}\) represent the fluorescence intensities before and immediately after photobleaching, and R denotes the mobile fraction. The bleaching parameter K, which quantifies the extent of bleaching, is calculated from the relationship \({F}_{0}/{F}_{{pre}}=(1-{e}^{-K})/K\). The variable is defined as \({\left[\frac{2\left(t-{t}_{0}\right)}{{\tau }_{D}}+1\right]}^{-1}\), where t₀ is the onset of recovery. The lower incomplete gamma function \(\gamma \left(K,|,\nu \right)={\int }_{0}^{K}{e}^{-u}{u}^{\nu -1}{du}\) captures the kinetics of fluorescence recovery. The full expression is given below

The second part involved determining the radius of the bleached region using Gaussian fitting. Fluorescence intensity profiles were extracted from post-bleach images using ImageJ by drawing line scans across horizontal, vertical, and diagonal axes of the bleached region of interest (ROI). These profiles were then fitted to a Gaussian model, as given in Eq. (2) using the non-linear fitting module in OriginPro. The effective radius was calculated as \({r}_{e}=2{r}_{t}\), and the diffusion coefficient could be derived from the relation \({D}_{{FRAP}}=\frac{{r}_{e}^{2}}{4{\tau }_{D}}=\frac{{r}_{t}^{2}}{{\tau }_{D}}\).

NMR spectroscopy

Samples of nucleotide–MCl2 (M = Mg or Ca) solutions were prepared at a concentration of 0.70 M nucleotide and varying concentrations of M2+ ions, with or without the addition of 0.10 M 5-hydroxytryptamine (5HT), as described above. Each sample had a total volume of 500 μL and was adjusted to pH 5.4. For all experiments except DOSY, 50 μL of 0.10 M DSS in D2O was added during sample preparation for field locking and chemical shift calibration. For DOSY experiments, DSS in D2O was omitted to avoid potential kinetic effects; instead, samples were transferred directly into 5 mm Norell NMR tubes and sealed with a coaxial insert (Norell, catalog # NI5CCI-B) containing 0.10 M DSS in D2O.

All NMR measurements were carried out at 298 K on a Bruker Avance III 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm broadband observe (BBO) probe. 1H NMR spectra were referenced to the methyl peak of DSS. For 31P spectra, the reference was set to the residual hydrolyzed phosphate from nucleotide. Spectra were processed using TopSpin 3.6.1, titration data were analyzed in MestreNova 14.0.0 (https://mestrelab.com/software/mnova/nmr), and chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) were fitted in OriginPro. Equation (3) was used to describe the binding equilibrium between ATP and divalent cation, \({{\rm{ATP}}}+{{\rm{n}}}{{{\rm{M}}}}^{2+}\leftrightarrow {{\rm{ATP}}}\cdot {{{\rm{M}}}}_{{{\rm{n}}}}^{2+}\), with stoichiometry n, equilibrium dissociation constant KD, and maximum chemical shift perturbation \({\delta }_{\infty }\) fitted parameters

Here, \({\left[{M}^{2+}\right]}_{{total}}\), \({\left[{ATP}\right]}_{{total}}\) are the respective concentrations in the reaction mixture, and \({\delta }_{0}\) is the initial chemical shift value for free ATP.

Water NOE spectra were acquired using the Bruker pulse sequence ephogsygpno54, which was modified by applying continuous-wave (CW) irradiation on labile protons during the mixing time to suppress exchange-relayed NOE signals55. For selective inversion of water, a 20 ms Gaussian-shaped 180° pulse was used, with the power adjusted for optimal excitation. The mixing time (d8 in Bruker notation) ranged from 5 to 1000 ms. Peak areas of all ATP signals were integrated in MestreNova with the water signal held positive, and plotted as a function of mixing time.

Diffusion-ordered spectroscopy (DOSY) was performed using either the standard pulse sequence56 or our modified version (Supplementary Fig. 10). Gradient strength calibration was carried out at 298 K using ddH2O sealed with a coaxial DSS insert (63 G/cm). For each new DOSY sample, the 90° pulse was recalibrated. Pulsed field gradients were applied in 19 linearly incremented steps from 5% to 95% of the maximum strength. The diffusion delay Δ (d20 in Bruker notation) ranged from 50 to 800 ms, and the gradient pulse length δ (p30 in Bruker notation) was adjusted so that the final signal intensity at maximum gradient was reduced to 3–7% of the intensity at minimum gradient.

DOSY spectra were first processed in TopSpin; peak integration was performed in Bruker Dynamics Center, with the output denoted as I in the fitting routines. The data were exported to OriginPro and fitted using either a mono-exponential or bi-exponential decay model, described by Eq. (4), where n represents the number of components (n = 1 for mono-exponential, 2 for bi-exponential) and i represents the pre-factor of the relative contribution:

Dark-state exchange saturation transfer (DEST) spectra were acquired with the dephasing block of 90°(x)–G1–90°(y)– G1–CW(x)–90°(x)–acquisition, where the dephasing gradient (G1) had a duration of 1 ms and a strength of 30% of the maximum z-gradient (18.9 G/cm). CW irradiation was applied for 1 s at nutation frequencies of 150 or 300 Hz. The power of the CW pulse was calculated from Eq. (5), where TCW is the duration of CW and PLWCW the corresponding power level:

For 31P DEST, spectra were acquired over a frequency offset with the range of ±15,000 Hz in 100 Hz steps, and were normalized using reference spectra acquired at ±90,000 Hz. Spectra were processed and integrated in MestreNova. DEST profiles were plotted in OriginPro as normalized intensities (I/I0), where I0 refers to intensity at highest offset (±90,000 Hz). The exchange parameters, assuming a two-state exchange model, were fitted using the software ChemEx (https://www.github.com/gbouvignies/chemex, ref. 57).

Estimation of the size of ATP nanoclusters

Based on Stokes-Einstein equation, the translation diffusion coefficient (D) is given by

where \(\eta\) is the viscosity of the solution and the \({R}_{h}\) is the hydrodynamic radius of the molecule or molecular assembly. From the bi-exponential fitting of the DOSY data collected with the standard pulse sequence, we observed that Dslow is as small as 1/20 of Dfast, which is in turn ~1/2 of the bulk water (Supplementary Table 2). This means that the hydrodynamic radius of the ATP nanocluster is about 40 times greater of water molecule. Since this comparison is internal to the same sample, the effect of viscosity is effectively normalized.

Assuming uniform shape and mass distribution, and using the molecular weight of water (18 Da) as a reference, the molecular weight (M) of the ATP nanocluster is estimated as

Given the molecular weight of a Mg2+–ATP complex (0.5:1 in stoichiometry) is approximately 519 Da (507 Da for ATP plus half of a Mg2+ ion at 12 Da), this corresponds to

molecules of Mg2+-ATP in each nanocluster.

To estimate the volume of the nanocluster, we use the partial specific volume of ATP (~1 cm³/g), denser than that of typical proteins58. The conversion to nanometers is given by

Using M = 1,152,000 Da, the volume is calculated as ~1912 nm3. Assuming a spherical shape, the radius (R) is calculated as

This radius can be an underestimate, as the hydrated ATP nanocluster comprises coated water molecules and may have a density lower than 1 g/cm3. The diameter of the nanocluster \(D=2\times R\) is ~15 nm, comparable to the thickness of the filaments observed in the percolated network of the ATP hydrogel.

Molecular dynamics simulations

Force field parameters for ATP-containing systems were prepared using tLeap from AMBER 22. The AMBER OL3 force field was applied to ATP, with the exception of the polyphosphate region, for which modified parameters from ref. 59 were used. To account for electronic screening in the highly negatively charged phosphate groups while preserving the polarity of the adenosine moiety, partial charges on the polyphosphate were scaled by a factor of 0.746. Water molecules were modeled using the OPC model60, which provides an accurate representation of ATP properties and water–ATP interactions at high concentrations61. Monovalent and divalent ions were treated using the Li/Merz 12-6 Lennard-Jones non-bonded parameter set62,63.

Each system was first energy-minimized for 40,000 steps with positional restraints on heavy atoms, followed by an additional 40,000 steps without restraints. The systems were then heated to 300 K for 200 ps. Equilibration was performed under constant pressure and temperature (NPT ensemble; 300 K, 1 atm) for 1 ns, allowing the simulation box to shrink to ~50 × 50 × 50 ų. Long-range electrostatic interactions were computed using the particle mesh Ewald (PME) method, while short-range non-bonded interactions were truncated at a cutoff distance of 10.0 Å.

Production runs were carried out under constant volume and temperature (NVT ensemble) for 10 ns at 300 K. Temperature was maintained using a Langevin thermostat with a collision frequency of 1.0 ps⁻¹, and pressure was regulated during the NPT stage using the Berendsen barostat. Snapshots were generated and visualized in PyMol3.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are included in the main text and Supplementary Information.

References

Shin, Y. & Brangwynne, C. P. Liquid phase condensation in cell physiology and disease. Science 357, eaaf4382 (2017).

Wang, J. et al. A Molecular grammar governing the driving forces for phase separation of prion-like RNA binding proteins. Cell 174, 688–699.e616 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Membraneless organelles in health and disease: exploring the molecular basis, physiological roles and pathological implications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 9, 305 (2024).

Banani, S. F., Lee, H. O., Hyman, A. A. & Rosen, M. K. Biomolecular condensates: organizers of cellular biochemistry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 285–298 (2017).

Farag, M., Borcherds, W. M., Bremer, A., Mittag, T. & Pappu, R. V. Phase separation of protein mixtures is driven by the interplay of homotypic and heterotypic interactions. Nat. Commun. 14, 5527 (2023).

Ambadi Thody, S. et al. Small-molecule properties define partitioning into biomolecular condensates. Nat. Chem. 16, 1794–1802 (2024).

Klosin, A. et al. Phase separation provides a mechanism to reduce noise in cells. Science 367, 464–468 (2020).

Snead, W. T. & Gladfelter, A. S. The control centers of biomolecular phase separation: how membrane surfaces, PTMs, and active processes regulate condensation. Mol. Cell 76, 295–305 (2019).

Zhao, Y. G. & Zhang, H. Phase separation in membrane biology: the interplay between membrane-bound organelles and membraneless condensates. Dev. Cell 55, 30–44 (2020).

Omiatek, D. M. et al. The real catecholamine content of secretory vesicles in the CNS revealed by electrochemical cytometry. Sci. Rep. 3, 1447 (2013).

Estevez-Herrera, J. et al. ATP: The crucial component of secretory vesicles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 113, E4098–E4106 (2016).

Sleutel, M. & Van Driessche, A. E. Role of clusters in nonclassical nucleation and growth of protein crystals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 111, E546–E553 (2014).

Mittag, T. & Pappu, R. V. A conceptual framework for understanding phase separation and addressing open questions and challenges. Mol. Cell 82, 2201–2214 (2022).

Banerjee, P. R., Milin, A. N., Moosa, M. M., Onuchic, P. L. & Deniz, A. A. Reentrant phase transition drives dynamic substructure formation in ribonucleoprotein droplets. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 56, 11354–11359 (2017).

Maharana, S. et al. RNA buffers the phase separation behavior of prion-like RNA binding proteins. Science 360, 918–921 (2018).

Portz, B. & Shorter, J. Biochemical timekeeping via reentrant phase transitions. J. Mol. Biol. 433, 166794 (2021).

Henninger, J. E. et al. RNA-mediated feedback control of transcriptional condensates. Cell 184, 207–225 e224 (2021).

Chawla, R. et al. Reentrant DNA shells tune polyphosphate condensate size. Nat. Commun. 15, 9258 (2024).

Wadsworth, G. M. et al. RNA-driven phase transitions in biomolecular condensates. Mol. Cell 84, 3692–3705 (2024).

Lin, Y., Protter, D. S., Rosen, M. K. & Parker, R. Formation and maturation of phase-separated liquid droplets by RNA-binding proteins. Mol. Cell 60, 208–219 (2015).

Martin, E. W. et al. A multi-step nucleation process determines the kinetics of prion-like domain phase separation. Nat. Commun. 12, 4513 (2021).

Chatterjee, S. et al. Reversible kinetic trapping of FUS biomolecular condensates. Adv. Sci. 9, e2104247 (2022).

Carducci, F., Yoneda, J. S., Itri, R. & Mariani, P. On the structural stability of guanosine-based supramolecular hydrogels. Soft Matter 14, 2938–2948 (2018).

Tang, Y. M. et al. Prediction and characterization of liquid-liquid phase separation of minimalistic peptides. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2, 100579 (2021).

Bai, Q., Zhang, Q., Jing, H., Chen, J. & Liang, D. Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation of Peptide/Oligonucleotide Complexes in Crowded Macromolecular Media. J. Phys. Chem. B 125, 49–57 (2021).

Yuan, C. Q., Li, Q., Xing, R. R., Li, J. B. & Yan, X. H. Peptide self-assembly through liquid-liquid phase separation. Chem 9, 2425–2445 (2023).

Meyers, K. M., Holmsen, H. & Seachord, C. L. Comparative-study of platelet dense granule constituents. Am. J. Physiol. 243, R454–R461 (1982).

Hiasa, M. et al. Essential role of vesicular nucleotide transporter in vesicular storage and release of nucleotides in platelets. Physiol. Rep. 2, e12034 (2014).

Pokrovskaya, I. D. et al. 3D ultrastructural analysis of alpha-granule, dense granule, mitochondria, and canalicular system arrangement in resting human platelets. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 4, 72–85 (2020).

Ugurbil, K., Fukami, M. H. & Holmsen, H. P-31 NMR-studies of nucleotide storage in the dense granules of pig platelets. Biochemistry 23, 409–416 (1984).

Takaya, K., Niiya, K., Toyoda, M. & Masuda, T. High magnesium concentrations in the dense bodies of human blood platelets from patients with atopic dermatitis and chronic myelogenous leukemia. Med. Electron Microsc. 27, 330–332 (1994).

Berneis, K. H., Pletscher, A. & Daprada, M. Phase separation in solutions of noradrenaline and adenosine triphosphate - influence of bivalent cations and drugs. Br. J. Pharmacol. 39, 382–389 (1970).

Hubley, M. J., Locke, B. R. & Moerland, T. S. The effects of temperature, pH, and magnesium on the diffusion coefficient of ATP in solutions of physiological ionic strength. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1291, 115–121 (1996).

Sigel, H. & Griesser, R. Nucleoside 5’-triphosphates: self-association, acid-base, and metal ion-binding properties in solution. Chem. Soc. Rev. 34, 875–900 (2005).

Fawzi, N. L., Ying, J., Ghirlando, R., Torchia, D. A. & Clore, G. M. Atomic-resolution dynamics on the surface of amyloid-beta protofibrils probed by solution NMR. Nature 480, 268–272 (2011).

Fawzi, N. L., Ying, J., Torchia, D. A. & Clore, G. M. Probing exchange kinetics and atomic resolution dynamics in high-molecular-weight complexes using dark-state exchange saturation transfer NMR spectroscopy. Nat. Prot. 7, 1523–1533 (2012).

Egner, T. K., Naik, P., Nelson, N. C., Slowing, I. I. & Venditti, V. Mechanistic insight into nanoparticle surface adsorption by solution nmr spectroscopy in an aqueous gel. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 56, 9802–9806 (2017).

Kamagata, K. et al. Molecular principles of recruitment and dynamics of guest proteins in liquid droplets. Sci. Rep. 11, 19323 (2021).

Jain, A. & Vale, R. D. RNA phase transitions in repeat expansion disorders. Nature 546, 243–247 (2017).

Ma, Y. et al. Nucleobase Clustering contributes to the formation and hollowing of repeat-expansion RNA condensate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 4716–4720 (2022).

Majumder, S., Coupe, S., Fakhri, N. & Jain, A. Sequence-encoded intermolecular base pairing modulates fluidity in DNA and RNA condensates. Nat. Commun. 16, 4258 (2025).

Collins, K. D. Ion hydration: Implications for cellular function, polyelectrolytes, and protein crystallization. Biophys. Chem. 119, 271–281 (2006).

Stern, N. et al. Studies of Mg2+/Ca2+ complexes of naturally occurring dinucleotides: potentiometric titrations, NMR, and molecular dynamics. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 17, 861–879 (2012).

Gliko, O. et al. Metastable liquid clusters in super- and undersaturated protein solutions. J. Phys. Chem. B 111, 3106–3114 (2007).

Patel, A. et al. ATP as a biological hydrotrope. Science 356, 753–756 (2017).

Mehringer, J. et al. Hofmeister versus Neuberg: is ATP really a biological hydrotrope?. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2, 100343 (2021).

Zhu, Y. et al. ATP promotes protein coacervation through conformational compaction. J. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, mjae038 (2025).

Dinsmore, A., Dubin, P. & Grason, G. Clustering in complex fluids. J. Phys. Chem. B 115, 7173–7174 (2011).

Wang, X. et al. An inorganic biopolymer polyphosphate controls positively charged protein phase transitions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 59, 2679–2683 (2020).

Ge, S., White, J. G. & Haynes, C. L. Quantal release of serotonin from platelets. Anal. Chem. 81, 2935–2943 (2009).

Ge, S., Woo, E., White, J. G. & Haynes, C. L. Electrochemical measurement of endogenous serotonin release from human blood platelets. Anal. Chem. 83, 2598–2604 (2011).

Kang, M., Day, C. A., Drake, K., Kenworthy, A. K. & DiBenedetto, E. A generalization of theory for two-dimensional fluorescence recovery after photobleaching applicable to confocal laser scanning microscopes. Biophys. J. 97, 1501–1511 (2009).

Loren, N. et al. Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching in material and life sciences: putting theory into practice. Q. Rev. Biophys. 48, 323–387 (2015).

Dalvit, C., Fogliatto, G., Stewart, A., Veronesi, M. & Stockman, B. WaterLOGSY as a method for primary NMR screening: practical aspects and range of applicability. J. Biomol. NMR 21, 349–359 (2001).

Melacini, G., Kaptein, R. & Boelens, R. Editing of chemical exchange-relayed NOEs in NMR experiments for the observation of protein-water interactions. J. Magn. Reson. 136, 214–218 (1999).

Wu, D. H., Chen, A. D. & Johnson, C. S. An Improved diffusion-ordered spectroscopy experiment incorporating bipolar-gradient pulses. J. Magn. Reson., Ser. A 115, 260–264 (1995).

Vallurupalli, P., Bouvignies, G. & Kay, L. E. Studying “invisible” excited protein states in slow exchange with a major state conformation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 8148–8161 (2012).

Singh, M. & Sharma, Y. K. Applications of activation energy and transition state theory for nucleos(t)ides and furanose helix puckering interactions in aqueous medium from 288.15 to 298.15. K. Phys. Chem. Liq. 44, 1–14 (2006).

Meagher, K. L., Redman, L. T. & Carlson, H. A. Development of polyphosphate parameters for use with the AMBER force field. J. Comput. Chem. 24, 1016–1025 (2003).

Shabane, P. S., Izadi, S. & Onufriev, A. V. General purpose water model can improve atomistic simulations of intrinsically disordered proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 15, 2620–2634 (2019).

Mori, T. & Yoshida, N. Tuning the ATP-ATP and ATP-disordered protein interactions in high ATP concentration by altering water models. J. Chem. Phys. 159, 035102 (2023).

Li, P., Song, L. F. & Merz, K. M. Jr Systematic Parameterization of Monovalent Ions Employing the Nonbonded Model. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11, 1645–1657 (2015).

Sengupta, A., Li, Z., Song, L. F., Li, P. & Merz, K. M. Jr. Parameterization of monovalent ions for the OPC3, OPC, TIP3P-FB, and TIP4P-FB water models. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 61, 869–880 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the NMR facility at the National Center for Protein Sciences at Peking University and the NMR platform of the State Key Laboratory of Natural and Biomimetic Drugs at Peking University for their technical support and assistance with data collection. We thank Profs. Dehai Liang and Peng Xi for providing access to the rheometer and SIM, respectively, and for their guidance during the measurements. This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2023YFF1205600) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 92353304).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.L. and C.T. designed research; Z.L. performed research; Z.L. modified the DOSY pulse sequence with the help T.Y.; Z.L. analyzed data and wrote the first draft of the paper; C.T. revised the paper with inputs from two other authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Yuwen, T. & Tang, C. Nanocluster intermediates orchestrate the phase transition of ATP condensates. Commun Chem 8, 411 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01804-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01804-8