Abstract

In March 2011, the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station (FDNPS) suffered reactor core overheating and fuel melting following the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami, producing complex microparticles from vaporized and rapidly solidified nuclear and structural materials. The chemical states and local structures of key elements in these particles, particularly uranium and plutonium, remain poorly constrained. Here, we present the synchrotron-based micro-focused X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) and X-ray diffraction (XRD) study of microparticles recovered from inside Unit 2 of FDNPS. The particles contain uranium, zirconium, and trace plutonium uniformly incorporated into chemically homogeneous oxide matrices. Two types were identified: uranium-rich particles with cubic UO2 and mixed U-Zr oxides with tetragonal ZrO2, the latter persisting at room temperature, indicating rapid cooling from a high-temperature metastable phase above 1650 °C. Both uranium and plutonium are mainly in the +4 state, with localized valence increases in zirconium-rich regions, suggesting redox-driven charge compensation during crystallization. These results provide direct evidence of melt evolution, actinide mixing, and oxidation-state preservation during severe reactor accidents, informing models of core degradation and strategies for safe decommissioning at FDNPS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station (FDNPS) accident in March 2011 remains one of the most severe nuclear incidents in history, triggered by the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. A complete loss of power at Units 1–3 led to reactor core overheating, severe fuel damage, and partial meltdowns, primarily driven by residual decay heat and exothermic zirconium-water reactions1. These events led to the formation of complex mixtures of nuclear fuel debris within the reactors, whose physical and chemical characteristics remain only partially understood due to the extreme difficulty of accessing the highly radioactive reactor cores, such as the primary containment vessels (PCVs), and retrieving the debris.

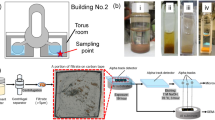

Characterizing the composition and structure of this fuel debris is crucial for developing safe decommissioning strategies, assessing long-term stability, and predicting behavior under environmental exposure2. In November 2024, a pivotal milestone was achieved with the successful retrieval of the first fuel debris sample, weighing approximately 0.7 g, from inside Unit 2 of the FDNPS. On the other hand, prior to this, numerous micrometer-sized particles originating from the reactor interior had been collected during remote inspections of Units 1–32,3. These particles are thought to have formed through melting, condensation, sublimation or evaporation, and solidification under extreme thermal conditions. They offer rare and valuable insights into the chemical processes that took place during the accident. Of particular interest are the oxidation states and local chemical environments of uranium, plutonium, and zirconium in these particles. These elements serve as key indicators of the redox conditions and thermal history experienced by the fuel. Moreover, their chemical behavior and spatial distribution provide critical insights into the safety, environmental mobility, and long-term stability of the debris. Understanding their chemical forms at the microscale is essential for safety assessments related to the storage and management of fuel debris, as it can reveal important information about accident progression and potential changes during long-term aging.

Synchrotron-based X-ray techniques, especially micro-focused X-ray fluorescence (XRF), X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES), and X-ray diffraction (XRD), provide a powerful, non-destructive approach to determine elemental distributions, oxidation states, and crystal structures in complex radioactive samples with micrometer spatial resolution. Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA) has established a dedicated synchrotron beamline, BL22XU, at SPring-8 for advanced analyses of nuclear materials. It is currently the only beamline in Japan capable of handling nuclear materials, enabling synchrotron-based analysis of these particles from FDNPS.

In this study, we apply synchrotron XRF, XANES, and XRD to investigate microparticles collected from within Unit 2 of FDNPS. Unit 2 is of particular interest due to its distinct accident sequence, unlike Units 1 and 3, it did not experience a hydrogen explosion, but suffered core degradation and likely PCV breach1. By probing the valence states and local structural environments of uranium, plutonium, and zirconium in selected particles, we aim to understand their formation history and provide insights into the physicochemical evolution of nuclear fuel debris under extreme accident conditions.

Results

XRF mapping and elemental composition

We conducted micro-XRF mapping on samples and identified several distinct microparticles ranging in size from 5 to 30 μm. These particles were recovered from inside Unit 2 of the FDNPS, as detailed in the sample description subsection of the Methods section. Figure 1 presents their morphology and elemental distributions. Four representative particles (designated A1, A2, B, and C) were selected for detailed analysis. Figures 1a–c, d–f, g–i) display the XRF mappings of the U Lα, Pu Lα, and Zr Kα lines for particles A1 and A2, B, and C, respectively. The spatial distributions of U Lα, Zr Kα, and Pu Lα signals are nearly identical across all particles within the spatial resolution of the present experimental setup (~1 μm). To illustrate the relative signal intensities, the corresponding XRF spectra acquired near the centers of these particles are shown in Fig. 1j.

a–c Maps of U Lα, Pu Lα, and Zr Kα emission lines for particles A1 and A2. d–f Corresponding elemental maps for particle B. g–i Corresponding elemental maps for particle C. j XRF spectra of particles A1, A2, B, and C. The spectra are normalized to the peak intensity of the U Lα emission line in each spectrum.

Particles A1 and A2 are compact (approximately 5 μm) and uranium-rich, with U Lα-to-Zr Kα fluorescence intensity ratios of 9.5:0.5 and 8:2 as estimated from XRF spectrum shown in Fig. 1j, respectively. As shown in the inset, the Pu Lα signal was less than 1% of the U Lα intensity. In contrast, particle B, approximately 20 μm in size, shows a zirconium-rich profile, with a Zr Kα signal that exceeds that of U Lα. The U Lα-to-Zr Kα fluorescence intensity ratio is approximately 4:6. Particle C, with a diameter of approximately 30 μm, exhibits a U Lα-to-Zr Kα fluorescence intensity ratio of about 6:4, which is almost the inverse of the ratio observed in particle B.

It should be noted that the relationship between the U Lα-to-Zr Kα fluorescence intensity ratio and the actual chemical composition is not well established in the present study, as data of reference samples were not acquired under the same experimental conditions. However, calculated X-ray fluorescence cross sections at an incident photon energy of approximately 20 keV indicate that the cross sections of these lines are nearly comparable: 5.42 × 103 barns for U Lα at hν = 21.95 keV and 5.48 × 103 barns for Zr Kα at hν = 20 keV4. Therefore, although the observed intensity ratio may be influenced by experimental geometry and self-absorption effects, the U Lα-to-Zr Kα fluorescence intensity ratio can still serve as a rough indicator of the relative elemental composition.

Meanwhile, the relative intensity of the Pu Lα fluorescence is less than 1% of U Lα, though precise estimation is challenging due to the very weak Pu signal. Assuming comparable fluorescence cross sections (While no detailed calculations are available for the Pu Lα fluorescence cross section, it is presumed to be comparable to that of U Lα, as these transitions involve orbitals with identical quantum numbers and the elements are adjacent in the periodic table.), the Pu content is likewise estimated to be below 1% relative to U. While the exact plutonium inventory of Unit 2 fuel is unknown, this estimate is consistent with typical spent nuclear fuel, which generally contains approximately 1% Pu by weight depending on burnup.

Fluorescence signals from additional elements associated with reactor structural materials (e.g., Fe Kα, Ni Kα, Zn Kα, etc.) were also detected in the XRF spectra, underscoring the chemically complex nature of these microparticles (For XRF spectra covering a broader photon energy range, please refer to the Note 1 and Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Information.). These signals fall within a relatively low photon energy range (hν = 6–9 keV) and are highly sensitive to experimental conditions, such as the air path length between the sample and the detector, making it difficult to reliably quantify intensity ratios. Although a detailed analysis was not performed in this study, the presence of these elements likely reflects incorporation of molten or degraded reactor structural materials into the fuel melt during high-temperature conditions.

XRD and crystal structure

To elucidate the crystalline phases present in the microparticles, we performed XRD measurements on two representative samples, particles A1 and B, which exhibit markedly different uranium and zirconium compositions. Figure 2 presents the XRD patterns obtained from these particles. Although the diffraction profiles are dominated by strong reflections originating from the aluminum substrate used to support the samples, several additional, weaker peaks are discernible. To interpret these features, we conducted detailed peak fitting using reference patterns for known uranium and zirconium oxide phases.

The dominant reflections arise from the aluminum substrate, while relatively weak reflections are attributed to the microparticles. a XRD pattern of particle A1, overlaid with simulated diffraction peaks corresponding to a fluorite-type UO2 crystal structure. b XRD pattern of particle B, overlaid with simulated diffraction peaks based on a tetragonal-type ZrO2 crystal structure.

In the uranium-rich particle A1 shown in Fig. 2a, the observed weak diffraction peaks are mostly indexed by a fluorite-type cubic uranium dioxide (UO2) structure, as shown in red curve, although the experimental pattern contains unexplained peaks, suggesting the mixed-phase nature of the particle in a microscopic scale. The refined lattice parameter of the cubic phase is a = 5.4093 Å, approximately 99% of the reported value for stoichiometric UO2 (a = 5.47127 Å)5, suggesting the formation of a cubic UxZr1−xO2 solid solution6.

Conversely, particle B shown in Fig. 2b, which has a higher zirconium-to-uranium ratio, exhibits a distinctly different set of diffraction peaks. These peaks are best matched by a tetragonal ZrO2-type structure, as indicated by the green curve, suggesting a zirconia-rich composition and partial solid solution formation. It should be noted that, in addition to the dominant reflections, weak peaks near 17° and 21° were observed in the XRD pattern of particle B. The origin of these peaks could not be identified, and they may arise from minor secondary phases present within the particle. According to the equilibrium phase diagram of the UO2–ZrO2 system6, the thermodynamically stable form of UxZr1−xO2 at room temperature is a mixture of monoclinic and cubic phases, while the tetragonal phase is stable only at elevated temperatures above approximately 1100 °C. The presence of the tetragonal ZrO2 phase at room temperature and its implications are discussed in detail in the Discussion section.

Based on the XRD results, it is likely that the crystalline structure of the particles was formed through the segregation and solidification of the U–Zr–O fuel melt into a U-rich cubic phase and a Zr-rich tetragonal phase. Similar phase separation has been reported in the melted core of the Three Mile Island (TMI) reactor6. These particles also preserve critical information about the thermal conditions, redox environment, and cooling history inside Unit 2 of the FDNPS during the accident.

XANES and chemical states

Zr K XANES spectra

We next examine the XANES spectra of zirconium, uranium, and plutonium to gain insights into the local chemical environments within the microparticles. Figure 3 presents Zr K XANES spectra of microparticles and reference ZrO2 samples with different crystal structures. Figure 3 shows a comparison of the Zr K-edge XANES spectra for particles A1, A2, B, and C. The spectral profiles of all particles closely resemble that of ZrO2, and differ markedly from that of metallic zirconium, indicating that zirconium is predominantly present in its oxidized form as ZrO2.

a Zr K XANES spectra of particles A1, A2, B, and C. The smoothed spectrum for particle A1 is shown as a dotted curve. b Zr K XANES spectra of ZrO2 reference compounds with monoclinic, orthorombic, tetragonal, and cubic crystal structures for comparison. Reprinted figure 12 with permission from Ping Li et al.7. Copyright 1993 by the American Physical Society.

Zirconium K-edge XANES spectra are typically characterized by three distinct features: a pre-edge peak (denoted as a) and two prominent resonances in the white-line region (labeled b and c). Previous studies have shown that the relative intensities of these features are sensitive to the crystal structure of zirconium oxide7, as illustrated in Fig. 3b. Notably, feature b is enhanced in monoclinic ZrO2, the thermodynamically stable phase at room temperature, but it is suppressed in all particles examined in this study, indicating that none of them adopt a monoclinic structure. This suggests that the Zr-containing phases are metastable tetragonal or cubic phases, likely formed through rapid quenching from high temperatures during the accident.

In particles B and C, the comparable intensities of features b and c are consistent with a tetragonal ZrO2 structure, implying that the local coordination of Zr is tetragonal-like. In contrast, particle A2 exhibits a relative enhancement of feature c over b, which is indicative of a more cubic-like environment around the Zr atoms. Although the spectrum of particle A1 is too noisy for detailed analysis, its overall profile, estimated from the smoothed spectrum, resembles that of particle A2, with slightly enhanced intensities in features a and c. These similarities likely indicate a predominantly U-rich cubic environment surrounding zirconium.

Taken together, the variations in XANES spectral features across the particles indicate a compositional dependence of the local Zr environment: uranium-rich particles tend to exhibit cubic-like symmetry, whereas zirconium-rich particles favor tetragonal coordination. These results are consistent with the XRD data.

U L III XANES spectra

Figure 4 summarizes the U LIII XANES spectra of those particles together with reference compounds. Figure 4a shows the U LIII spectra of particles A1, A2, B, and C, along with reference spectra of stoichiometric UO2 and U3O8. The absorption edges, estimated from the inflection points of the spectra, defined as the energies where the second derivative becomes zero, are indicated by solid circles for the particles and solid squares for the reference compounds. The spectral shapes and absorption edges of particles A1, A2, B, and C closely resemble those of UO2 rather than U3O8. However, the precise positions of the absorption edges exhibit slight variations among the particles. The inset shows a close-up of the spectra, together with the absorption edge positions indicated by solid circles and squares. The absorption edges of particles A1 and A2 closely match that of UO2, indicating that uranium in these particles predominantly exists in the U4+ oxidation state and is coordinated within a fluorite-type structure, consistent with the XRD results discussed earlier. In contrast, the absorption edges of particles B and C deviate from the U4+ state, with particle B’s edge significantly deviated from it, suggesting that some of the uranium may be oxidized to the U5+ state in particles B and C. The origin of the correlation between zirconium content and uranium oxidation state is also considered in the Discussion section.

Pu L III XANES spectra

Figure 5 presents the Pu LIII XANES spectra of particles A1 and B. Due to the extremely low concentration of plutonium in these samples (less than 1% relative to uranium), the spectral features are generally weak but still detectable, although its signal fell below the detection limit in particle C. Despite the low signal intensity, a slight shift in the white-line position can be observed between particles A1 and B. The inset shows a close-up of the spectra, together with the absorption edge positions estimated from their arctangent fittings, indicated by circles. It should be noted that the absorption edges of the particles were determined using an arctangent fit, rather than the second derivative method applied in the U LIII XANES analysis, in order to allow direct comparison with the referenced data.

Reported absorption edge energies from previous studies8,9 are also indicated as dotted lines. Although these values differ slightly (by ~0.6 eV), the edge position of particle A1 falls within this range. The spectrum of particle A1 closely resembles that of PuO2, including the characteristic oscillatory feature at approximately 18.11 eV, which corresponds to the nearest Pu–O bond distance. Therefore, while precise quantification of the absolute oxidation state is not feasible, the data strongly suggest that plutonium in particle A1 predominantly exists in the +4 oxidation state.

In contrast, the absorption-edge energy of particle B is shifted by approximately 0.6 eV relative to particle A1. In addition, the oscillatory feature in the spectrum of particle B is slightly displaced compared with that of particle A1, suggesting possible structural modifications around Pu relative to PuO2.

Together, these results indicate that particle B contains partially oxidized Pu and/or exhibits structural distortions in the local Pu environment. A similar trend is observed in the U LIII XANES spectra, where the absorption edge shifts by approximately 0.9 eV between particles A1 and B. The largely consistent behavior of uranium and plutonium, combined with the homogeneous elemental distributions revealed by XRF mapping, supports the interpretation that both elements are uniformly incorporated within the same oxide matrices.

Discussion

Combined structural and chemical analyses of microparticles recovered from inside Unit 2 of the FDNPS provide critical insights into their origin and the physicochemical processes that occurred during the severe nuclear accident. Two compositionally distinct types of microparticles were identified: uranium-rich oxide particles (A1 and A2), which crystallize in a fluorite-type cubic UO2 structure, and mixed U-Zr oxide particles (B and C), which adopt a tetragonal ZrO2-type structure.

In the uranium-rich particles, the local environment around zirconium atoms is also cubic, as evidenced by the ZrK XANES spectra, suggesting partial substitution of uranium sites by zirconium in the fluorite lattice. This interpretation is supported by the slightly reduced lattice parameter of particle A1 (5.4093 Å) compared to that of pure UO2 (5.47127 Å), consistent with the smaller crystal ionic radius of Zr4+ (0.86 Å) relative to U4+ (1.03 Å). On the other hand, according to the experimental lattice constants and Vegard’s law of the cubic UxZr1−xO2 phase10,11,12, the lattice constant of particle A1 corresponds to an expected U-to-Zr ratio of approximately 8:2, which differs substantially from the ratio estimated by XRF intensities of about 9.5:0.5. This discrepancy may reflect the incorporation of Fe into the cubic UxZr1−xO2 matrix, which is known to reduce the lattice constant due to its smaller atomic radius13. However, its influence cannot be quantified in the present study due to the lack of qualitative estimate of Fe incorporation.

In contrast, particles B and C exhibit ZrK absorption edge features consistent with a tetragonal structure based on a ZrO2-type framework, with uranium concentrations comparable to that of zirconium and trace amounts of plutonium. The stability of the tetragonal phase at room temperature is noteworthy, as pure ZrO2 typically stabilizes in the monoclinic form below approximately 1100 °C. Tetragonal-type UxZr1−xO2 solid solutions at room temperature have also been reported in debris from the TMI accident14 and in UO2–ZrO2 corium melting and spreading experiments10, where they are attributed to metastable phases formed at high temperatures. According to the phase diagram of the pseudo-binary UO2–ZrO2 system10, a metastable tetragonal phase UxZr1−xO2 solid solution up to x ~0.4 can form at temperatures exceeding 1650 °C. The observed tetragonal phase in the present study may have originated under such high-temperature conditions, with its structure preserved by rapid quenching that kinetically suppressed the transformation to the monoclinic phase.

In Zr-rich particles, uranium exhibits a mixed +4/+5 oxidation state. Zirconium remains in the +4 state across all samples, as shown by the consistent edge position in the ZrK spectra (Fig. 3a). The mechanism underlying the correlation between zirconium content and actinide oxidation state remains unclear. Potential contributing factors include increased oxygen availability resulting from water radiolysis under intense radiation fields, or redox interactions involving transition metals such as Fe incorporated into the zirconium-rich phases. Further sampling and investigation are required to assess the universality and the origin of this correlation. Meanwhile, in U-rich particles, uranium and plutonium are predominantly present in the +4 oxidation state, which is in agreement with the cubic crystal structure observed for these particles.

Overall, these results suggest that the microparticles preserve a detailed chemical and structural record of the high-temperature, redox, and cooling conditions inside the reactor during the accident. The compositional and structural differences between particle types reflect localized segregation and crystallization processes within the debris pool. These findings not only improve our understanding of nuclear fuel behavior under extreme conditions but also provide essential data for modeling core degradation, supporting future strategies for debris retrieval, long-term storage, and reactor decommissioning.

Conclusion

This study provides direct evidence of fuel microparticle formation from a molten U–Zr–O pool inside Unit 2 of the FDNPS, with uranium, zirconium, and plutonium uniformly incorporated into oxide matrices. Two distinct particle types were identified, uranium-rich and mixed U-Zr oxide particles, whose compositions, crystal structures, and actinide oxidation states reflect different solidification pathways. Uranium and plutonium were found homogeneously distributed and predominantly in the +4 oxidation state, with oxidation shifts linked to local chemistry. These particles preserve the chemical and structural signatures of their formation and suggest long-term chemical stability, supporting current containment safety and informing future decommissioning and environmental management efforts.

Methods

Sample preparation

The radioactive micro particles were collected from the smear paper taken from X-6 penetration route of FDNPS Unit 2. They were put onto a piece of carbon tape (approximately 10 × 10 mm) on thin aluminum plate, and sealed by a stainless sample holder and Kapton films in Fuels and Materials Department Facility in Oarai, Ibaraki. The samples were then transferred to SPring-8 by a chartered special vehicle. The details of the samples are described in ref. 2.

Synchrotron radiation experiment

The experiments were conducted at the JAEA-contracted beamline BL22XU at SPring-815. A monochromatic X-ray microbeam was focused to approximately 1 μm using a Kirkpatrick-Baez mirror system, consisting of a vertical mirror (200 mm in length) and a horizontal mirror (300 mm in length), both tilted at 1.7 mrad. Elemental mapping and XRF measurements were performed using a silicon drift detector (SDD). XRD measurements were carried out with a CsI scintillator flat-panel detector. To avoid interference from the transmitted beam, the sample was positioned to prevent beam obstruction after transmission. The incident X-ray energy for XRF and XRD measurements was set to 20 keV. XANES spectra were acquired using the Quick Scan method. In this approach, the undulator gap was fixed while the Si(111) monochromator crystals were scanned continuously, allowing real-time data acquisition. Fluorescence signals for XANES were detected using a 19-element Ge semiconductor detector. Incident X-ray intensity was monitored and controlled using a nitrogen-filled ionization chamber.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Hirano, M. et al. Insights from review and analysis of the Fukushima Dai-ichi accident. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 49, 1–17 (2012).

Kurata, M., Okuzumi, N., Nakayoshi, A., Ikeuchi, H. & Koyama, S. Step-by-step challenge of debris characterization for the decommissioning of Fukushima-Daiichi Nuclear Power Station (FDNPS). J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 59, 807–834 (2022).

Zubekhina, B., Pshenichnikov, A., Nagae, Y. & Kurata, M. The key role of sample analysis in Fukushima Dai-Ichi decommissioning, debris management, and accident progression investigation. Front. Nucl. Eng. 2, 1324221 (2023).

Puri, S. et al. K and L shell X-ray fluorescence cross sections. Data Nucl. Data Tables 61, 289–311 (1995).

Leinders, G., Cardinaels, T., Binnemans, K. & Verwerft, M. Accurate lattice parameter measurements of stoichiometric uranium dioxide. J. Nucl. Mater. 459, 135–142 (2015).

Seibert, A. et al. Thermophysical properties of U, Zr-oxides as prototypic corium materials. J. Nucl. Mater. 520, 165–177 (2019).

Li, P., Chen, I.-W. & Penner-Hahn, J. E. X-ray-absorption studies of zirconia polymorphs. I. Characteristic local structures. Phys. Rev. B 48, 10063–10073 (1993).

Conradson, S. D. et al. Oxidation state determination of plutonium aquo ions using X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Polyhedron 17, 599–602 (1998).

Kropf, A. J., Reed, D. T. & Aase, S. B. X-ray Absorption Near-edge Spectroscopy of Plutonium Solid Species (Argonne National Lab., 1998).

Piluso, P., Trillon, G. & Journeau, C. The UO2-ZrO2 system at high temperature (T > 2000 K): importance of the meta-stable phases under severe accident conditions. J. Nucl. Mater. 344, 259–264 (2005).

Zhang, L., Shelyug, A. & Navrotsky, A. Thermochemistry of UO2 – ThO2 and UO2 – ZrO2 fluorite solid solutions. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 114, 48–54 (2017).

Xiao, H. et al. Investigation of the mechanical properties of ZrO2-doped UO2 ceramic pellets by indentation technique. J. Nucl. Mater. 509, 482–487 (2018).

Okamoto, Y. & Takano, M. Chemical state analysis of simulated corium debris by EXAFS. Prog. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 5, 200–203 (2018).

Brown, A., McIntyre, G. J. & Gräslund, C. Analysis of crystalline phases in core bore materials from Three Mile Island Unit 2. Nucl. Technol. 87, 137–145 (1989).

Shobu, T. et al. Wide band energy beamline using Si (111) crystal monochromators at BL22XU in SPring-8. AIP Conf. Proc. 879, 902–906 (2007).

Acknowledgements

The experiment was performed under Proposal No. 2023B3708 at SPring-8 BL22XU. The authors would like to thank Shinya Mizokami, Masato Mizokami, Mutsumi Hirai, and Masaki Kurata for stimulating discussion and comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.K., M.K. and H.T. prepared samples, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and worked on figures; Y.O. performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and worked on figures; S. F. performed the experiments, analyzed the data, worked on figures, and wrote the manuscript; Y.T., T.T., T.F., G.S., I.K., R.D., T.O. and Y.S. performed the experiments; S.S. and K.M. prepared samples; T.Y. designed the study, performed the experiments, and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kobayashi, T., Kobata, M., Tanida, H. et al. Synchrotron radiation analysis of microparticles from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power station. Commun Chem 9, 13 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01820-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01820-8