Abstract

Single-molecule magnets (SMMs) show promise for high-density data storage due to molecular-level magnetic hysteresis, but low-temperature quantum tunneling of magnetization (QTM) limits their blocking temperatures (TB), making QTM suppression critical. Herein, we report two dinuclear Er-cyclooctatetraenyl compounds: [K(18-C-6)(THF)][(COT1,4TMS2)Er(μ-Cl)₃Er(COT1,4TMS2)] (1) and [K(18-C-6)(THF)₂][(COT1,3TMS2)Er(μ-Br)₃Er(COT1,3TMS2)] (2) (COT1,4TMS2 and COT1,3TMS2 donate 1,4- and 1,3-bis(trimethylsilyl)-substituted cyclooctatetraenyl ligands, respectively; 18-C-6 = 18-Crown-6 ether). In both compounds, the two Er(III) ions are triply bridged by Cl− (1) or Br− (2). Ab initio calculations confirm strong axial anisotropy and ferromagnetic axial dipolar interactions from “head-to-tail” magnetic easy axes. Such axial dipolar interactions lead to the QTM being effectively suppressed by minimizing transverse dipolar fields, yielding hard magnetic behavior with open magnetic hysteresis loops up to 10 K and coercive fields of 6.25 kOe (1) and 4.75 kOe (2) at 2 K. These results demonstrate tunable halide-bridged dinuclear architectures for hard-magnetic SMMs via a non-radical approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Magnetic materials constitute a significant category of functional materials that find extensive applications across various industries in contemporary society, including information processing and storage, energy conversion and electrical engineering, healthcare and biomedical applications, consumer electronics, and sensors, etc.1,2. According to the coercivity characteristics of magnetic hysteresis loops, magnetic materials are typically categorized into two classes: soft and hard. The coercivity values of soft magnets are <100 Oe, while they are >1000 Oe for hard magnets (Fig. 1a)1,2,3,4. Hard magnets, commonly called permanent magnets, are utilized to generate magnetic fields in various applications, including motors, alternators, magnetic resonance imaging scanners, computers, mobile phones, and numerous other advanced technological products2,5.

a Hysteresis loops for a soft magnetic material (orange, featuring a narrow hysteresis curve with low coercivity and low remanence), a hard magnetic material (sky blue, a large hysteresis due to the high coercivity and remanence), and for an SMM with strong QTM (olive green, showing a “butterfly-like” hysteresis loop that features low coercivity and low remanence near zero field while remaining open at higher fields). b A diagram of the relaxation processes in a typical SMM with the Orbach, Raman, and QTM processes dominating the magnetic relaxation at high, intermediate, and low temperatures, respectively. The direct process becomes significant only under high magnetic fields.

Single-molecule magnets (SMMs) are a new kind of molecular-based magnetic materials that exhibit magnetic hysteresis at the single-molecule level6. With a single molecule as the smallest functional unit, SMMs are thus well-known as promising candidates for high-density information storage7,8,9. The key parameter for SMMs is the relaxation time (τ), representing the time for magnets to achieve magnetic equilibrium10. The τ should be adequately long, for example, longer than 100 s, so that the magnetic hysteresis loops can be observed and the SMMs can be used to process information11,12. It has been proven that τ values are often contributed by the Orbach process, the Raman process, the direct process, and the quantum tunneling of magnetization (QTM) process (Fig. 1b)13,14. The Orbach, Raman, and QTM processes typically dominate magnetic relaxation at high, intermediate, and low temperature regimes, respectively, while the direct process will be the main process when a high dc field is applied. Due to the rapid QTM effect, the magnetic relaxation at low temperatures is often very fast, so many SMMs exhibit soft magnetic properties with narrow or butterfly-shaped hysteresis loops13,14,15,16,17,18,19. To enhance the “hardness” of SMMs, extending the τ at low temperatures is crucial, with suppression of QTM being the key strategy.

The QTM for SMMs is often influenced by various factors, including molecular vibrations, hyperfine interactions between nuclear spins and electronic spins, crystal field effects, and magnetic exchange couplings20,21,22,23. Manipulating the magnetic exchange couplings has been proven to be the most effective approach to achieve hard SMMs11,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. For example, the N23– radical-bridged dilanthanide complexes, {[(Me3Si)2N]2(THF)Tb}2(μ-η2:η2-N2)− held the record of blocking temperature (TB) for SMMs for a long time11,24,25. In 2022, the metal–metal bonding between lanthanide ions was discovered, which induces an exchange constant of J = +387(4) cm−1, leading to ultra-hard SMMs with coercive fields exceeding 14 T below 60 K31,32. We note that previously Magott and colleagues reported an interesting example of enhancing magnetic blocking through metal–metal bonding in [Er(ReCp2)3] that entails the direct coordination of transition metal complex units with a lanthanide ion center33; the hysteresis loop opens within the range of 0.05–1.5 T at 1.8 K, representing the widest span among trigonal Er(III) SMMs. However, compounds featuring radical bridges or metal–metal bonds often exhibit high sensitivity to moisture and oxygen. In contrast, a non-radical strategy for achieving hard SMM behavior is highly desirable.

Recently, axial dipolar fields—achievable via “side-by-side” or “head-to-tail” magnetic dipole arrangements—have been shown to effectively suppress QTM as well34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41. Building on our previous work in changing the magnetic dipole from a “staggered” arrangement to a “head-to-tail” alignment by introducing an additional bridging atom (Cl–) into dinuclear complex units39, we report herein the synthesis, crystal structures, and magnetic properties of two dinuclear erbium cyclooctatetraenyl (Er-COT) compounds, namely [K(18-C-6)(THF)][(COT1,4TMS2)Er(μ-Cl)3Er(COT1,4TMS2)] (1) and [K(18-C-6)(THF)2][(COT1,3TMS2)Er(μ-Br)3Er(COT1,3TMS2)] (2) (COT1,4TMS2 and COT1,3TMS2 donate 1,4- and 1,3-bis(trimethylsilyl)-substituted cyclooctatetraenyl ligands, respectively; THF = tetrahydrofuran; 18-C-6 = 18-crown-6 ether), in which the two Er(III) ions are triply-bridged by three halide ions (Cl– for 1 and Br– for 2). The effect of the bridging atoms on intramolecular dipolar interactions and magnetic properties was investigated by ab initio calculations, and comparative studies with other structure similar SMMs, including [K(18-C-6)][(COT)Er(μ-Cl)3Er(COT)] (Er2Cl3)39 and [Li(THF)4][(ErCOT)2(μ-CH3)3](Er2(CH3)3)36.

Results and discussion

Syntheses and crystallographic analyses

The precursor for the cyclooctatetraenide dianion (COTTMS2), namely 5,8-bis(trimethylsilyl)-1,3,6-cyclooctatriene (H2COTTMS2), was prepared following literature procedures42,43. The potassium salt of the cyclooctatetraenide dianion (K2COTTMS2) was synthesized by deprotonation of H2COTTMS2 with n-BuLi (2.5 M in hexane), followed by a cation-exchange reaction with KOtBu42. Compounds 1 and 2 were prepared using analogous synthetic protocols, differing only in the rare-earth salt employed: anhydrous ErCl₃ for compound 1 and ErBr₃ for compound 2. Specifically, the rare-earth salts were dispersed in THF, and a THF solution of K2COTTMS2 was slowly added dropwise. The reaction mixtures were stirred at room temperature for 12 h, after which 0.5 equiv of 18-C-6 was introduced, followed by an additional 12 h of stirring. The organic phase was then filtered, and the solvent was removed under vacuum. Crystals suitable for single-crystal X-ray diffraction were obtained by layering n-hexane into a THF solution of the two compounds.

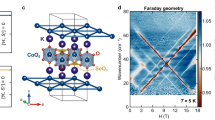

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction analyses (Table S1 and Supplementary Data 1) reveal that both compounds crystallize in the monoclinic system, with compound 1 in space group P2₁/n and compound 2 in C2/c. Structurally, both are dinuclear entities comprising a core anionic moiety and counter cations. The counter cations in both compounds are K⁺ ions chelated by 18-C-6 and THF molecules, though with a key distinction: the counter cation in compound 1 features one THF molecule coordinated to K⁺, whereas compound 2 exhibits two THF ligands. This disparity likely arises from steric interactions between the TMS groups of the anionic framework and the K⁺ ion in compound 1, restricting additional THF coordination44. The anionic cores of both compounds are dinuclear Er(III) complexes tris-bridged by three halogen ions, sandwiched between two COT rings. The halogen bridges are Cl− for compound 1 and Br− for compound 2, analogous to the structures of Er2Cl340 and Er2(CH3)337 compounds. In compound 2, we observed a positional rearrangement of the TMS groups—from the 1,4-positions in K2COTTMS2 to the 1,3-positions. Literature indicates that such structural rearrangements can be thermally induced or driven by countercation variations in complex anions43,45,46,47,48. However, the differing halogen ions are probably the primary cause of this structural disparity in the present system.

The [(COT)Er(μ-X)3Er(COT)]− cores for 1 and 2 are structure similar to these for Er2Cl340 and Er2(CH3)337 with similar bond lengths (Table 1), including: the average Er–C bond lengths are ranging from 2.5371 to 2.5434 Å for the two compounds (Tables S2 and S3); the distance from Er(III) to the COT ring center is 1.7365 Å for 1 and 1.7463 Å for 2. The intramolecular Er–Er distance in 1 is 3.6918 Å, which is close to the value for Er2Cl3, while it is 3.8316 Å for 2, which is the longest for the four structurally similar compounds, probably because the ionic radius of Br− is larger than that of Cl− and CH3−. The Er–X (X = Cl for 1 and Br for 2) bond lengths range from 2.5371 to 2.5434 Å for 1, and 2.8548 to 2.8633 Å for 2. All the above values are similar to other Er-COT36,37,39,40,41,42,43,49,50,51,52,53 or Er–Br compounds54,55. The minimum intermolecular Er(III) distances in 1 and 2 are 10.1373 and 10.6572 Å, respectively.

Ab initio calculations

The magnetic energy manifolds of the ground states for each Er(III) ion in 1 (Er(1) and Er(2)) and 2 (Er(1)) were evaluated with CASSCF/SO-RASSI/SINGLE_ANISO/POLY_ANISO ab initio calculations using OpenMolcas (Table S4)56,57,58,59. The principal anisotropy axes of the ground Kramers doublets (KDs) for the three Er(III) ions in 1 and 2 are closely aligned with the vector from the Er(III) ion to its COT centroid (Fig. 2b and c). This phenomenon is similar to other Er-COT SMMS, because the f-electron cloud of the Er(III) ion is prolate and the π coordination of the COT ligands can maximize its magnetic anisotropy effectively49. Because the two COT rings are close to parallel with dihedral angles <3.48° in such tri-bridged complexes (Table 1), the magnetic easy axes are all close to a perfect “head-to-tail” arrangement (Fig. 2b and c). The angles (θ) between the calculated magnetic easy axes and the intramolecular Er–Er vector are <1.25° for the two compounds (Table 2). Such an arrangement of the magnetic easy axes leads to highly axial intramolecular dipolar interactions (vide infra).

a Preparations of cyclooctatetraenide dianion (COT1,4TMS2) and the rearrangement of TMS groups in compound 2 from the 1,4-positions in K2COT1,4TMS2 to 1,3-positions (COT1,3TMS2) in the presence of anhydrous ErBr₃. b Ball-and-stick depiction of the crystal structure of [(COT1,4TMS2)Er(μ-Cl)3Er(COT1,4TMS2)]− anion in compound 1. c Ball-and-stick depiction of the crystal structure of [(COT1,3TMS2)Er(μ-Br)3Er(COT1,3TMS2)]− anion in compound 2. The pink-colored vectors are the main anisotropy axes of the ground doublets obtained from the CASSCF-SO calculations. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity (color legends: Er, purple; O, red; Cl, green; Br, dark red; Si, turquoise; C, gray). # 1—X, Y, 1.5—Z.

The calculated electronic states of Kramers doublets for these Er(III) ions are often closely related to the magnetic relaxation dominated by the Orbach process59, a phonon-assisted thermal relaxation mechanism that follows an Arrhenius law. According to the mean absolute values of the corresponding matrix element of transition magnetic moments, the probable relaxation pathway by the Orbach process can be proposed with the energy gaps close to the experimental energies for the Orbach process. The ground KDs for compounds 1 and 2 (Tables S5–S13) are all dominated by the mJ = ±15/2 component with contributions over 98.5%, g-factors gx, gy < 0.003, and gz > 17.83. Such pure and highly axial anisotropic ground states represent a prerequisite for SMMs36,37,39,40,43,49,50,51,52,53. The excited KDs are slightly different for the two compounds. For compound 1, the first excited KDs are primarily from mJ = ±1/2 states (>92.7% contribution), and the second excited KDs are predominantly composed of mJ = ±13/2 states, with contributions of more than 84.5%. On the contrary, the first and second excited KDs for 2 are mainly contributed by mJ = ±13/2 (>87.2% contribution) and mJ = ±1/2 states (>89.8% contribution). So the most probable relaxation pathway of the Orbach process is via the first excited KDs for 1 (Fig. 3a) and the second excited KDs for 2 (Fig. 3b).

CASSCF-SO calculated energies of KDs (thick black lines) as a function of the projection of their magnetic moment along the principal magnetic axis for Er(1) in 1 (a) and Er(1) in 2 (b). POLY_ANISO calculated energies of DDs (thick black lines) as a function of magnetic moment projection for 1 (c) and 2 (d), respectively. Green lines: Represent QTM through ground KDs/DDs and thermally assisted QTM (TA-QTM) via excited KDs/DDs. Blue lines: Denote off-diagonal relaxation processes. Red arrows: Indicate the most probable Orbach relaxation pathway through energy barriers. Purple lines a, b: Show experimental energy barriers for the Orbach process. Numerical labels: Indicate the mean absolute value of transition magnetic moment matrix elements for each pathway.

The intramolecular dipolar interactions for compounds 1 and 2 were calculated by using the POLY_ANISO program based on the results from CASSCF/SO-RASSI/SINGLE_ANISO/POLY_ANISO calculations (Tables S14 and S15)60,61. The obtained values are 1.3697 cm–1 for 1 and 1.2298 cm–1 for 2, which are comparable with the value for Er2Cl3 (1.3651 cm–1) but smaller than the value for Er2(CH3)3 (1.952 cm–1). As the θ values are <1.25°, which is close to the Ising axis (θ = 0°), suggesting that these dipolar interactions are ferromagnetic34. The average axial components of the dipolar fields (Baxial) are 261.57 and 234.53 Oe for 1 and 2, respectively, which are significantly larger than the average transversal components (Btrans) of 6.60 Oe (1) and 2.89 Oe (2) (Table 2). Such highly anisotropic intramolecular dipolar fields can effectively suppress the QTM34,35,36,37,38,39,40. What’s more, the transition probabilities between the dipole-induced Zeeman eigenstates (DDs) are less than 2 × 10−14 (Fig. 3c and d), suggesting the magnetic relaxations will prefer an Orbach process through the excited DDs at low temperatures37.

Magnetic properties

The static magnetic properties for 1 and 2 were investigated by temperature-dependent susceptibilities, which were measured under a 1000 Oe DC field from 300 to 2 K and low-temperature field-dependent magnetizations (Figs. S1 and S2). At 300 K, the χMT values are 22.83 and 22.94 for 1 and 2, respectively, which are in excellent agreement with the theoretical value of 22.92 cm3 K mol–1 for two uncoupled Er(III) ions (J = 15/2, gJ = 6/5). For compound 1, the χMT values decrease with cooling to a minimum value of 18.11 cm3 K mol–1 at 32 K, owing to the crystal-field state depopulation. The χMT values for 2 remain almost unchanged above 22 K. A Gradual increase of the χMT values was observed for 1 below 32 K to a maximum value of 20.57 cm3 K mol–1 at 6 K, and below 22 K to a maximum value of 22.79 cm3 K mol–1 at 10 K for 2. Such behavior is probably because of the presence of ferromagnetic intramolecular dipolar interactions. The χMT values subsequently decrease to 18.40 and 15.18 cm3 K mol–1 at 2 K for 1 and 2, respectively, suggesting the presence of antiferromagnetic interactions, which may be antiferromagnetic dipolar interactions and/or super-exchange interactions. At 2 K and 7 T, the maximum magnetizations are 8.62 and 10.04 μB for 1 and 2, respectively. The overall static magnetic properties for 1 and 2 are similar to those for Er2Cl3, and reported for other dinuclear Er(III) SMMs36,37,40,49,51,62.

To investigate the dynamic magnetic properties of 1 and 2, AC magnetic susceptibilities were collected under zero applied field below 30 K. Peaks of out-of-phase component (χ“) of AC susceptibilities can be clearly observed below 20 K (Figs. S3 and S4, Supplementary Data 2) for the two compounds, indicative of SMM behaviors8. Frequency-dependent AC data were collected from 19 to 9 K for 1 (Fig. 4a), and from 19 to 10 K for 2 (Fig. 4b), which were fitted with a generalized Debye model to yield relaxation times and corresponding α parameters (Figs. S5 and S7, Tables S16 and S17)63,64. All the α parameters are <0.12, indicating narrow relaxation time distributions at the corresponding temperatures. The magnetic relaxation becomes very slow below 10 K, so that the relaxation times are beyond the time scale limit of standard AC magnetic susceptibility measurements, and DC decay measurements were applied65. Fitting the DC decay susceptibilities with the stretched exponential function yielded the relaxation times below 10 K for the two compounds (Figs. S6 and S8).

The temperature dependencies of the relaxation times (ln(τ) vs. 1/T) for 1 and 2 are remarkably similar (Fig. 5). The ln(τ) values increase linearly with 1/T above 10 K (1/T < 0.1), which is the typical behavior of the through-barrier Orbach process. Below 10 K (1/T > 0.1), the increase slows to nearly temperature-independent at 2 K. Such behavior is often regarded as the contributions from Raman and QTM processes. However, the QTM should be effectively suppressed by the axial intramolecular dipolar interactions as mentioned above, and the relaxation times are not fully temperature-independent down to 2 K. A second through-barrier Orbach process via the excited DDs may be dominant at low temperatures. As expected, the relaxation data of 1 and 2 can be well reduced with a combined Orbach process through excited KDs (\({\tau }_{0}^{-1}{{\mbox{e}}}^{-{U}_{{\mbox{eff}}}/T}\)) (Ueff is the energy barrier required for Orbach relaxation process through excited KDs and τ0 is its pre-exponential factor), Raman process(\({{CT}}^{n}\)) (C is the normalization constant and n is the exponent for Raman process), and Orbach process through excited DDs (\({\tau }_{{\mbox{D}}}^{-1}{{\mbox{e}}}^{-{D}_{{\mbox{eff}}}/T}\)) (Deff is the energy barrier required for Orbach relaxation process through excited DDs and τD is its pre-exponential factor) (Eq. (1))37. As shown in Table 3, all parameters are comparable between the two compounds, except that the τD value of 448(21) s for compound 2 is approximately six times larger than the τD of 74(3) s for compound 1. This difference is consistent with the variation in relaxation times between the two compounds, as reflected by the ratio of τ for compound 1 to compound 2 at the same temperatures (inset in Fig. 5), which increases with decreasing temperature. The Ueff are 162(1) and 170(1) cm−1 for 1 and 2, respectively, which are higher than the energies for the most probable Orbach process through the excited KDs by ab initio calculations. The Ueff for 1 (162(1) cm−1) and 2 (170(1) cm−1) are lower than the Ueff of 184(2) cm−1 for Er2Cl340, which lacks TMS substituents. This difference is probably because the TMS substituents induce strong molecular vibrations, thereby reducing the Ueff39,40. On the other hand, the Ueff for 1 and 2 are higher than the Ueff of 79(6) cm−1 for Er2(CH3)337, indicating the bridging ligands play an important role in controlling the magnetic anisotropy of Er(III) ions. The Deff for Orbach through excited DDs are identical to the energy gaps between the ground and excited DDs (Fig. 3c and d). Since the Orbach process is widely recognized as the slowest relaxation pathway in SMMs, designing SMMs where magnetic relaxation is exclusively governed by the Orbach process has been proposed as a highly effective strategy to achieve high blocking temperatures66,67,68,69. Further increase of the τD and Deff by chemical design will be very effective in designing SMMs with higher blocking temperatures.

The circles are plots of ln(τ) vs. 1/T for 1 (τa) and 2 (τb). Solid lines are the best fits with Eq. (1). The inset figure shows the ratio of τ of compound 1 and compound 2 at the same temperatures.

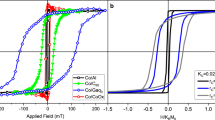

The magnetic blockings for 1 and 2 were investigated by magnetic hysteresis, field-cooled (FC), and zero-field-cooled (ZFC) magnetization measurements (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Data 3)8. As anticipated, both compounds exhibit distinct magnetic hysteresis loops that remain open up to 10 K (Fig. 6a and b). At 2 K, the coercive forces (Hc) of 1 and 2 are 6.25 and 4.75 kOe, respectively. The remanent magnetizations (Mr) are 6.95μB for 1 and 6.06μB for 2, indicating that the magnetizations exhibit approximately 80% and 60% hysteresis delays for 1 and 2, respectively. The blocking temperatures, defined as the peak temperature in the ZFC magnetization curve, are 5.8 and 6.8 K for 1 and 2, respectively (Fig. 6c and d). The magnetic blocking temperatures of 1 and 2 are comparable to those of Er2Cl3 but significantly higher than those of Er2(CH3)337,40. Like Er2Cl3, compounds 1 and 2 qualify as hard SMMs37, whereas Er2(CH3)3 behaves as a soft SMM above 2 K40. The main reason for such a difference is that the Ueff for 1, 2 and Er2Cl3, are much higher than the Ueff for Er2(CH3)3. As noted above, bridging ligands primarily influence Ueff, while substituents on the COT rings play a secondary role.

The magnetic hysteresis loops were measured at an average sweep rate of 200 Oe/s at the indicated temperatures for 1 (a) and 2 (b). The FC (blue) and ZFC (black) magnetization data for 1 (c) and 2 (d) at a sweep rate of 2 K/min. Red arrows: the peak temperature of the ZFC magnetization curve (defined as the blocking temperature TB). Solid lines serve as guides to the eyes.

Conclusions

In conclusion, two triply halide-bridged dinuclear Er(III)-COT SMMs exhibiting hard magnetic behavior have been successfully synthesized and comprehensively characterized. The impact of bridging atoms on their structural and magnetic properties was systematically investigated. A distinct rearrangement of TMS groups—from the 1,4-positions in the precursor to the 1,3-positions—was observed in the presence of Br⁻ ions. The triply halide-bridged architecture induces a “head-to-tail” alignment of magnetic easy axes in both compounds, accompanied by highly axial intramolecular dipolar interactions. These dipolar interactions effectively suppress QTM by minimizing transverse dipolar field components, thereby accounting for the hard magnetic behavior of these compounds. The suppression of QTM via axial dipolar interactions, coupled with the ability to tune properties through bridging atom engineering, establishes a viable non-radical strategy for advancing high-performance molecular magnetic materials. Future studies will focus on exploring alternative bridging ligands to further optimize dipolar interactions and enhance magnetic hardness.

Methods

General considerations and methods

All manipulations were performed using standard Schlenk techniques or in a glovebox under an argon atmosphere. All glassware was dried overnight at 120 °C before use. Anhydrous n-hexane was dried over activated alumina and stored over a potassium mirror before use. The potassium salt K₂COTTMS₂ was prepared according to literature procedures42,43. Commercially available reagents, including ultra dry ErCl₃, ErBr₃, tetrahydrofuran (THF), and 18-crown-6 ether (>99.5%), were purchased from Energy-Chemical and used as received.

Synthesis of ({[(COT1,4TMS2)Er(μ-Cl)₃Er(COT1,4TMS2)K(18-C-6)(THF)] (1)

Under an inert atmosphere, 205 mg (0.75 mmol) of super-dry ErCl₃ was added to a 25 mL Schlenk flask, followed by 6 mL of ultra-dry tetrahydrofuran (THF). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h to ensure complete dissolution of ErCl₃. Separately, 253 mg (0.5 mmol) of K₂COTTMS₂ was dissolved in 5 mL of THF and slowly added to the ErCl₃/THF solution over at least 30 min. The reaction mixture was then stirred for an additional 12 h. Subsequently, 66 mg (0.25 mmol) of 18-crown-6 was added to the flask, and the mixture was stirred for another 12 h. The resulting suspension was filtered to remove insoluble materials (primarily KCl and excess ErCl₃), and the organic solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The solid product obtained was re-dissolved in THF (3 mL), and the resulting solution was layered with n-hexane (6 mL) for recrystallization. Three days after the standing of this set-up at −35 °C, orange crystals of compound 1 suitable for X-ray diffraction studies were obtained (160 mg, 48% yield based on ErCl₃). Anal. Calc. for C44H80Cl3Er2KO7Si4: C, 40.24; H, 6.14; Found: C, 40.47; H, 6.33.

Synthesis of [(COT1,3TMS2)Er(μ-Br)₃Er(COT1,3TMS2)K(18-C-6)(THF)] (2)

Compound 2 was prepared by a procedure that is similar to the synthesis of 1, with the use of ErBr₃ in place of ErCl₃. The product was obtained as pink block crystals (157 mg, 41% yield based on ErBr₃). Anal. calc. for C48H88Br3Er2KO8Si4: C, 37.96; H, 5.84; Found: C, 37.76; H, 5.67.

Characterization

Elemental analyses were recorded on a Carlo Erba EA1110 simultaneous CHN elemental analyzer. Single crystal X-ray intensity data were collected at 100 K on a Bruker D8 VENTURE diffractometer with Mo-Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å). Using Olex2, the structure was solved with the SHELXT structure solution program using Intrinsic Phasing and refined with the SHELXL refinement package using least-squares minimization70,71,72. All hydrogen atoms were placed in calculated, ideal positions and refined as riding on their respective carbon atoms, with displacement parameters also dependent on the parent carbon atom Ueq value. The phase purity of the bulk polycrystalline sample was verified by comparing its powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) pattern with the simulated one based on the single-crystal structure (Figs. S9 and S10). The measurements were made at room temperature on a Bruker D8 Venture X-ray diffractometer equipped with Cu Kα radiation. The 2θ angle range spans from 5° to 50°. In a glovebox, the samples of both compounds were ground into a fine powder and subsequently loaded into a borosilicate glass capillary (a diameter of 0.5 mm and a wall thickness of 0.01 mm)33. Magnetic susceptibility measurements were carried out with a Quantum Design MPMS-3 SQUID magnetometer. Polycrystalline samples were sealed with melted eicosane in NMR tubes under vacuum.

Ab initio calculations

OpenMolcas56 was used to perform the CASSCF-SO calculation of the electronic structures of 1 and 2 with the molecular geometries taken from the crystallographic analyses; no optimization was made except for taking the largest disorder component. Relativistic effects have been accounted for by using the second-order Douglas–Kroll Hess Hamiltonian, and the basis sets from the ANO-RCC library57,58 were accordingly employed, with VTZP quality for Er atoms, VDZP quality for the coordinating C atoms, and VDZ quality for any remaining atoms. Cholesky decomposition of the two-electron integrals with a threshold of 10−8 was performed to save disk space and to reduce computational demand. The molecular orbitals were optimized in state-averaged CASSCF calculations within each spin manifold, with a minimal active space of 11 electrons in 7 orbitals and considering 35 and 112 roots for the spin quartet and doublet, respectively. For each spin multiplicity, the number of states mixed by spin–orbit coupling is also 35 and 112, respectively. The resulting spin-orbit wavefunctions were decomposed into their CF wavefunctions, and the magnetic susceptibility was calculated using SINGLE_ANISO59. The dipolar interactions in 1 and 2 were computed with POLY_ANISO60,61.

Data availability

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers 2471570 (1) and 2471569 (2) (Supplementary Data 1). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. The following data are part of the Supporting Information: X-ray crystallography, see Supplementary Information Tables S1–S3; Ab initio calculation results, see Supplementary Information Tables S4–S15; and magnetometry data, see Supplementary Information Tables S16, S17, Figs. S1–S8, Supplementary Data 1 and 2; Power X-ray diffraction patterns, see Supplementary Information Figs. S9 and S10.

References

Cullity, B. & Graham, C. Introduction to Magnetic Materials (IEEE Press, 2008).

Coey, J. M. D. Perspective and prospects for rare earth permanent magnets. Engineering 6, 119–131 (2020).

Silveyra, J. M., Ferrara, E., Huber, D. L. & Monson, T. C. Soft magnetic materials for a sustainable and electrified world. Science 362, eaao0195 (2018).

Kim, Y. & Zhao, X. Magnetic soft materials and robots. Chem. Rev. 122, 5317–5364 (2022).

Przybył, A., Gębara, P., Gozdur, R. & Chwastek, K. Modeling of magnetic properties of rare-earth hard magnets. Energies 15, 7951 (2022).

Gatteschi, D., Sessoli, R. & Villain, J. Molecular Nanomagnets (Oxford University Press, 2006).

Troiani, F. & Affronte, M. Molecular spins for quantum information technologies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 3119–3129 (2011).

Woodruff, D. N., Winpenny, R. E. P. & Layfield, R. A. Lanthanide single-molecule magnets. Chem. Rev. 113, 5110–5148 (2013).

Gaita-Ariño, A., Luis, F., Hill, S. & Coronado, E. Molecular spins for quantum computation. Nat. Chem. 11, 301–309 (2019).

Liu, J.-L., Chen, Y.-C. & Tong, M.-L. Symmetry strategies for high performance lanthanide-based single-molecule magnets. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 2431–2453 (2018).

Rinehart, J. D., Fang, M., Evans, W. J. & Long, J. R. A. N23– Radical-bridged terbium complex exhibiting magnetic hysteresis at 14 K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 14236–14239 (2011).

Gregson, M. et al. A monometallic lanthanide bis(methanediide) single molecule magnet with a large energy barrier and complex spin relaxation behaviour. Chem. Sci. 7, 155–165 (2016).

Ding, Y.-S. et al. Field- and temperature-dependent quantum tunnelling of the magnetisation in a large barrier single-molecule magnet. Nat. Commun. 9, 3134 (2018).

Ding, Y.-S. et al. Studies of the temperature dependence of the structure and magnetism of a hexagonal-bipyramidal dysprosium(III) single-molecule magnet. Inorg. Chem. 61, 227–235 (2022).

Jiang, S.-D., Wang, B.-W., Su, G., Wang, Z.-M. & Gao, S. A Mononuclear dysprosium complex featuring single-molecule-magnet behavior. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 7448–7451 (2010).

Jin, P.-B. et al. Thermally stable terbium(II) and dysprosium(II) bis-amidinate complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 27993–28009 (2023).

Emerson-King, J. et al. Isolation of a bent dysprosium bis(amide) single-molecule magnet. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 3331–3342 (2024).

Benner, F., Jena, R., Odom, A. L. & Demir, S. Magnetic hysteresis in a dysprosium bis(amide) complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 8156–8167 (2025).

Emerson-King, J. et al. Soft magnetic hysteresis in a dysprosium amide–alkene complex up to 100 Kelvin. Nature 643, 125–129 (2025).

Gatteschi, D. & Sessoli, R. Quantum tunneling of magnetization and related phenomena in molecular materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42, 268–297 (2003).

Zabala-Lekuona, A., Seco, J. M. & Colacio, E. Single-molecule magnets: from Mn12-Ac to dysprosium metallocenes, a travel in time. Coord. Chem. Rev. 441, 213984 (2021).

Kragskow, J. G. C. et al. Spin–phonon coupling and magnetic relaxation in single-molecule magnets. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 4567–4585 (2023).

Vieru, V., Gómez-Coca, S., Ruiz, E. & Chibotaru, L. F. Increasing the magnetic blocking temperature of single-molecule magnets. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202303146 (2024).

Rinehart, J. D., Fang, M., Evans, W. J. & Long, J. R. Strong exchange and magnetic blocking in N23−-radical-bridged lanthanide complexes. Nat. Chem. 3, 538–542 (2011).

Demir, S., Gonzalez, M. I., Darago, L. E., Evans, W. J. & Long, J. R. Giant coercivity and high magnetic blocking temperatures for N23− radical-bridged dilanthanide complexes upon ligand dissociation. Nat. Commun. 8, 2144 (2017).

Demir, S., Zadrozny, J. M., Nippe, M. & Long, J. R. Exchange coupling and magnetic blocking in bipyrimidyl radical-bridged dilanthanide complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 18546–18549 (2012).

Gould, C. A. et al. Substituent effects on exchange coupling and magnetic relaxation in 2,2′-bipyrimidine radical-bridged dilanthanide complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 21197–21209 (2020).

Mavragani, N. et al. Radical-bridged Ln4 metallocene complexes with strong magnetic coupling and a large coercive field. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 24206–24213 (2021).

Benner, F., La Droitte, L., Cador, O., Le Guennic, B. & Demir, S. Magnetic hysteresis and large coercivity in bisbenzimidazole radical-bridged dilanthanide complexes. Chem. Sci. 14, 5577–5592 (2023).

Bajaj, N. et al. Hard single-molecule magnet behavior and strong magnetic coupling in pyrazinyl radical-bridged lanthanide metallocenes. Chem 10, 2484–2499 (2024).

Gould, C. A. et al. Ultrahard magnetism from mixed-valence dilanthanide complexes with metal–metal bonding. Science 375, 198–202 (2022).

Kwon, H. et al. Coercive fields exceeding 30 T in the mixed-valence single-molecule magnet (CpiPr5)2Ho2I3. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 18714–18721 (2024).

Magott, M., Brzozowska, M., Baran, S., Vieru, V. & Pinkowicz, D. An intermetallic molecular nanomagnet with the lanthanide coordinated only by transition metals. Nat. Commun. 13, 2014 (2022).

Katoh, K. et al. Control of the spin dynamics of single-molecule magnets by using a quasi one-dimensional arrangement. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 9262–9267 (2018).

Chen, Y.-C. & Tong, M.-L. Single-molecule magnets beyond a single lanthanide ion: the art of coupling. Chem. Sci. 13, 8716–8726 (2022).

Orlova, A. P., Hilgar, J. D., Bernbeck, M. G., Gembicky, M. & Rinehart, J. D. Intuitive control of low-energy magnetic excitations via directed dipolar interactions in a series of Er(III)-based complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 11316–11325 (2022).

Bernbeck, M. G. et al. Dipolar coupling as a mechanism for fine control of magnetic states in ErCOT-alkyl molecular magnets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 7243–7256 (2024).

Deng, W. et al. Aggregation-induced suppression of quantum tunneling by manipulating intermolecular arrangements of magnetic dipoles. Aggregate 5, e441 (2024).

Ding, Y.-S., Chen, Q.-W., Huang, J.-Q., Zhu, X.-F. & Zheng, Z. Sandwich-type single-molecule magnets complexes of Er(III) with Ansa-cyclooctatetraenyl ligands. Chin. J. Chem. 42, 3099–3106 (2024).

Huang, J.-Q. et al. Enhancement of single-molecule magnet properties by manipulating intramolecular dipolar interactions. Adv. Sci. 12, 2409730 (2025).

Zhu, Z. et al. Record quantum tunneling time in an air-stable exchange-bias dysprosium macrocycle. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 18899–18904 (2024).

Chen, Q.-W., Ding, Y.-S., Xue, T., Zhu, X.-F. & Zheng, Z. A hundredfold enhancement of relaxation times among Er(III) single-molecule magnets with comparable energy barriers. Inorg. Chem. Front. 10, 6236–6244 (2023).

Chen, Q.-W., Ding, Y.-S., Zhu, X.-F., Wang, B.-W. & Zheng, Z. Substituent positioning effects on the magnetic properties of sandwich-type erbium(III) complexes with bis(trimethylsilyl)-substituted cyclooctatetraenyl ligands. Inorg. Chem. 63, 9511–9519 (2024).

Sellin, M. et al. Promoting alkane binding: crystallization of a cationic manganese(I)-pentane σ-complex from solution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202507494 (2025).

Lorenz, V., Edelmann, A., Blaurock, S., Freise, F. & Edelmann, F. T. A surprising solvent effect on the crystal structure of an anionic lanthanide sandwich complex. Organometallics 26, 6681–6683 (2007).

Edelmann, A. et al. Steric effects in lanthanide sandwich complexes containing bulky cyclooctatetraenyl ligands. Organometallics 32, 1435–1444 (2013).

Apostolidis, C. et al. A structurally characterized organometallic plutonium(IV) complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 5066–5070 (2017).

Lorenz, V. et al. The “Wanderlust” of Me3Si groups in rare-earth triple-decker complexes: a combined experimental and computational study. Chem. Commun. 54, 10280–10283 (2018).

Harriman, K. L. M. & Murugesu, M. An organolanthanide building block approach to single-molecule magnets. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 1158–1167 (2016).

Orlova, A. P., Bernbeck, M. G. & Rinehart, J. D. Designing quantum spaces of higher dimensionality from a tetranuclear erbium-based single-molecule magnet. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 23417–23425 (2024).

Hauser, A. et al. Cycloheptatrienyl-bridged triple-decker complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 13760–13769 (2024).

De, S., Mondal, A., Chen, Y.-C., Tong, M.-L. & Layfield, R. A. Single-molecule magnet properties of silole- and stannole-ligated erbium cyclo-octatetraenyl sandwich complexes. Chem. Eur. J. 31, e202500011 (2025).

Schwarz, N. et al. Rare earth stibolyl and bismolyl sandwich complexes. Nat. Commun. 16, 983 (2025).

Xie, Z., Liu, Z., Zhou, Z.-Y. & Mak, T. C. W. Synthesis and reactivity of cationic lanthanide metallocene complexes. hexabromocarborane and tetraphenylborate as counter ions. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 3367–3372 https://doi.org/10.1039/A804311F (1998).

Buschmann, D. A. et al. Multimetallic half-sandwich complexes of the rare-earth metals. Inorg. Chem. 64, 2795–2808 (2025).

Li Manni, G. et al. The OpenMolcas Web: a community-driven approach to advancing computational chemistry. J. Chem. Theory. Comput. 19, 6933–6991 (2023).

Roos, B. O., Lindh, R., Malmqvist, P. -Å, Veryazov, V. & Widmark, P.-O. Main group atoms and dimers studied with a New Relativistic ANO basis set. J. Phys. Chem. A 108, 2851–2858 (2004).

Roos, B. O., Lindh, R., Malmqvist, P. -Å, Veryazov, V. & Widmark, P.-O. New Relativistic ANO basis sets for transition metal atoms. J. Phys. Chem. A 109, 6575–6579 (2005).

Ungur, L. & Chibotaru, L. F. Ab initio crystal field for lanthanides. Chem. Eur. J. 23, 3708–3718 (2017).

Chibotaru, L. F., Ungur, L. & Soncini, A. The origin of nonmagnetic Kramers doublets in the ground state of dysprosium triangles: evidence for a toroidal magnetic moment. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 4126–4129 (2008).

Ungur, L., Van den Heuvel, W. & Chibotaru, L. F. Ab initio investigation of the non-collinear magnetic structure and the lowest magnetic excitations in dysprosium triangles. New J. Chem. 33, 1224–1230 (2009).

Handzlik, G., Żychowicz, M., Rzepka, K. & Pinkowicz, D. Exchange bias in a dinuclear erbium single-molecule magnet bridged by a helicene ligand. Inorg. Chem. 64, 15088–15097 (2025).

Guo, Y.-N., Xu, G.-F., Guo, Y. & Tang, J. Relaxation dynamics of dysprosium(III) single molecule magnets. Dalton Trans. 40, 9953–9963 (2011).

Reta, D. & Chilton, N. F. Uncertainty estimates for magnetic relaxation times and magnetic relaxation parameters. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 23567–23575 (2019).

Blackmore, W. J. A. et al. Characterisation of magnetic relaxation on extremely long timescales. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 25, 16735–16744 (2023).

Mondal, K. C. et al. Coexistence of distinct single-ion and exchange-based mechanisms for blocking of magnetization in a CoII2DyIII2 single-molecule magnet. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 7550–7554 (2012).

Wu, S.-G. et al. Field-induced oscillation of magnetization blocking barrier in a holmium metallacrown single-molecule magnet. Chem 7, 982–992 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Opening magnetic hysteresis by axial ferromagnetic coupling: from mono-decker to double-decker metallacrown. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 5299–5306 (2021).

Deng, W. et al. Engineering a high-barrier d–f single-molecule magnet centered with hexagonal bipyramidal Dy(III) unit. Sci. China Chem. 67, 3291–3298 (2024).

Dolomanov, O. V., Bourhis, L. J., Gildea, R. J., Howard, J. A. K. & Puschmann, H. OLEX2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 42, 339–341 (2009).

Sheldrick, G. SHELXT-integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. A 71, 3–8 (2015).

Sheldrick, G. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. C 71, 3–8 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (92261203, 22101116, and 21971106), the Guizhou Province Science and Technology Innovation Leading Talent Workstation of Solid Functional Materials (KXJZ[2024]015), the Guizhou Provincial Basic Research Program (Natural Science) (QN[2025]275), Science and Technology Program Project of Guizhou Province (2024-142), Key Laboratory of Rare-Earth Chemistry of Guangdong Higher Education Institutes (2022KSYS006), the Stable Support Plan Program of Shenzhen Natural Science Fund (20200925161141006), Shenzhen Fundamental Research Program (JCYJ20220530115001002 and JCYJ20220818100417037). Computational work was supported by the Center for Computational Science and Engineering at Southern University of Science and Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.W.C. synthesized and characterized the compounds with the assistance of J.Q.H. and Z.H. Y.S.D. performed magnetic measurements, modeled and interpreted the magnetic data, and performed CASSCF-SO calculations. Y.S.D., G.Y.Z., X.F.Z., and Z.P.Z. designed the research project and directed the experiments. The writing of the manuscript was completed by contributions from all authors, who have also given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Alessandro Prescimone and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, QW., Ding, YS., Huang, JQ. et al. Triply halogen-bridged erbium compounds with hard single-molecule magnet behavior. Commun Chem 9, 27 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01836-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01836-0