Abstract

Oxygen vacancies are regarded as crucial defects greatly affecting the electronic and optical properties of oxide films and devices, yet systematic studies on κ-Ga2O3 are still lacking. Herein, we investigate the thermodynamic, electronic, and optical properties of oxygen vacancies in κ-Ga2O3 using density functional theory calculations with the hybrid functional. The electronic structure reveals that oxygen vacancies create a deep donor defect in the bandgap, with defect levels and transition energies influenced by Ga atom displacement and localized electron dynamics. This interplay explains the stability of vacancies at specific sites and their connection to experimentally observed defect levels. Additionally, oxygen vacancies generate distinct absorption and electron energy loss peaks in the ultraviolet range. Our results elucidate the nature of oxygen vacancies, and offering a foundation for tuning and optimizing the electrical and optical properties of κ-Ga2O3 films and improving device performance through defect engineering.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ga2O3 exhibits significant potential for applications in power devices, deep-ultraviolet (UV) photodetectors (PDs), and extreme conditions physics, as well as in agricultural monitoring due to its ultra-wide bandgap of 4.6–4.9 eV1,2,3,4. There are five crystal phases of Ga2O3: \(\alpha\), \(\beta\), \(\gamma\), \(\delta\) and \(\kappa\), with β-Ga2O3 being the only thermodynamically stable phase. However, there is considerable interest in other metastable phases, particularly κ-Ga2O35,6,7. Compared to the monoclinic β-Ga2O3, orthorhombic κ-Ga2O3 features higher symmetry in its crystal structure, allowing it to be grown on commercially available substrates such as GaN, sapphire, and SiC8,9,10,11. This compatibility reduces heteroepitaxy costs and facilitates large-scale production of κ-Ga2O3 films. Interestingly, orthorhombic κ-Ga2O3 is a ferrielectric material exhibiting spontaneous polarization of 23–31 µC/cm2 along the (001) direction, which surpasses that of GaN by an order of magnitude6,12,13. This generates a two-dimensional electron gas at the heterojunction interface, promising applications in high electron mobility devices.

Numerous intrinsic defects frequently arise during the synthesis of Ga2O3, while extrinsic defects are commonly introduced artificially during the epitaxial growth process14. Among these, oxygen vacancies (\({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}\)) represent one of the most prevalent point defects in metal oxide semiconductors (MOS), significantly influencing their electrical resistivity, thermal conductivity, and overall semiconductor characteristics15,16. In various applications, \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}\) are regarded as critical defects that significantly impact the electrical and optical properties of Ga2O3 films and influence device behavior. For instance, leakage currents in \(\beta\)-Ga2O3 gate insulators or capacitors are attributed to electron conduction through trap levels in the forbidden gap induced by \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}\)17\(.\) Similarly, absorption losses in \(\beta\)-Ga2O3 coatings, which act as optically active traps, can impair the performance of optical devices such as high-average-power lasers18. In these cases, \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}\) are viewed as detrimental. Theoretical and experimental studies have extensively explored oxygen vacancies in \(\beta\)-Ga2O3, elucidating their formation energies, charge states, and impact on material properties14,19,20,21. Meanwhile, recent studies have started to explore the nature of oxygen vacancies in κ-Ga2O3, investigating their electronic structure and optical properties through a combination of experimental and computational approaches22,23,24. In addition, post-annealing approaches have been developed to enhance the photodetection performance of κ-Ga2O3 PDs by improving film quality and modulating the concentration of \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}\) defects10,25. Despite these advances, several important aspects of oxygen vacancies in κ-Ga2O3 remain to be clarified, such as their thermodynamic stability at different sites, dominant charge states under realistic growth conditions, and their detailed electronic and optical signatures. Furthermore, a comprehensive understanding using advanced first-principles methods is still lacking, particularly for correlating the microscopic properties of \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}\) with experimentally observed defect states and absorption features.

In this work, we employ first-principles computational methods based on hybrid density functional theory (DFT) to investigate the thermodynamic, electronic, and optical properties of oxygen vacancies in κ-Ga2O3. We identify thermodynamically favorable oxygen sites with lower vacancy formation energies that significantly contribute to the valence band maximum (VBM) wave function. Additionally, we analyze the concentrations and dominant oxidation states of oxygen vacancies as a function of growth conditions. Our findings suggest that experimentally observed but unidentified defect states in κ-Ga2O3 can be attributed to neutral oxygen vacancies. The additional absorption features arise from electron transitions between defect levels induced by oxygen vacancies and the valence band. Our work deepens the microscopic understanding of oxygen vacancy characteristics in κ-Ga2O3, which is essential for optimizing its electrical and optical properties, as well as advancing material synthesis and enhancing device performance.

Results and discussion

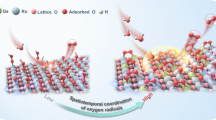

Structural and electronic properties of κ-Ga2O3

Figure 1 shows the optimized orthorhombic κ-Ga2O3 cell. The structural parameters of κ-Ga2O3 based on our calculation results and other previous theoretical with experimental results are listed in Table 1. The calculation results are in good agreement with other results derived from different functionals, which indicate our optimization method is reasonable. The primitive cell comprises 40 atoms, including four nonequivalent Ga atoms and six non-equivalent O atoms, where octahedra share edges or vertices with other octahedra or tetrahedra. The intricate tetrahedra/octahedra formation involves different Ga atom states (represented by different colors). The O atoms in κ-Ga2O3 can be divided into six types according to their occupation sites. The atomic coordinates of the optimized computational models are provided in Supplementary Data 1. It is well known that the difficulty in achieving p-type conductivity in κ-Ga2O3, as with other Ga2O3 polymorphs, is primarily due to its valence band structure: the valence band maximum (VBM) is relatively flat and composed mainly of highly localized O 2p orbitals, resulting in a large hole effective mass and low hole mobility. This band structure limits the migration ability of holes and makes it challenging to realize efficient p-type doping, as most acceptor impurities introduce deep acceptor levels rather than shallow ones20,26,27.

a The conventional cell and b the 80 atoms supercell of κ-Ga2O3. \({{{\rm{Ga}}}}_{1}-{{{\rm{Ga}}}}_{4}\) atoms with different coordinates are represented by green, purple, blue and cyan spheres, while \({{{\rm{O}}}}_{1}-{{{\rm{O}}}}_{6}\) atoms with different coordinates are illustrated as pink, yellow, red, white, gray, and dark cyan spheres.

The electronic band structure was calculated on the stable equilibrium structural configuration using PBE approximation and HSE functional, and the results are plotted in Fig. 2 with blue and pink lines, respectively. κ-Ga2O3 is usually considered as a direct bandgap semiconductor, our calculations reveal that its VBM is located along the high-symmetry \(\Gamma\)-\({{\rm{X}}}\) path in momentum space, while the conduction band minimum (CBM) resides at the \(\Gamma\) point. The reason why κ-Ga2O3 has always been considered as a direct gap semiconductor is that the energy difference between the actual VBM and the valence band at Γ point to the CBM is only 0.003 eV. Such a small energy difference is generally not enough for the electron to overcome the large momentum transfer from the actual VBM to the CBM. Therefore, κ-Ga2O3 is generally regarded as a direct ultrawide bandgap semiconductor. As can be clearly seen from Fig. 2, there is a great difference between the bandgap obtained by the PBE approximation and HSE functional. The latter is 4.62 eV, while the former is only 2.10 eV, far from the experimental value 4.60 eV28. Furthermore, it can be found that κ-Ga2O3 has a flat VBM, which means the large effective mass and weak migration ability of holes, which is also the reason why κ-Ga2O3 with p-type properties is difficult to prepare.

Electronic properties of κ-Ga2O3 with O vacancies

The electronic band structures of κ-Ga2O3 are calculated using the HSE functional. As illustrated in Fig. 3, these structures are unfolded for different neutral oxygen vacancy sites with the easyunfold code29. A defect level occupied by two electrons emerges, with the defect levels of these six types of vacancies located at energies of 2.41 eV, 3.39 eV, 3.37, 3.34, 3.96 and 3.98 eV from the CBM, respectively. All oxygen vacancy defect levels are deep donors, link to the band structures of other defective oxides semiconductor like ZnO, Ta2O5 and Al2O330,31,32. Furthermore, the electron density of states (DOS) for κ-Ga2O3 with all neutral oxygen vacancies was also computed using the HSE hybrid functional, as is shown in Fig. 4. The detailed partial density of states (PDOS) for the deep donor levels of each O vacancy is shown in the inset at the upper right corner. The valence and conduction bands edge do not change significantly, apart from the appearance of a defect peak within the ultrawide bandgap. Analysis of the PDOS reveals that the defect states primarily arise from Ga-4s, Ga-4p, and O-2p contributions. While previous arguments suggest that the unpaired dangling bonds of Ga ions around the vacancies are the primary contributors to these defect peaks, it is important to note that the contributions from the oxygen atoms are not negligible and play a meaningful role in the overall electronic structure.

Defect formation energy

The vacancy formation energy \({E}_{{{\rm{tot}}}}[{V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}^{q}]\) is key for defining defects and understanding how point defects and their charges affect semiconductor performance. Determining \({E}_{{{\rm{tot}}}}[{V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}^{q}]\) facilitates the precise alteration of critical properties. Formation energies for various oxygen vacancies in κ-Ga2O3 across different charge states have been calculated as a function of the Fermi energy, as depicted in Fig. 5. This analysis considers both oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor conditions, focusing on the most energetically favorable charge state for each vacancy at specific Fermi levels. At the mid-gap position of the Fermi level, the stability of charged vacancies surpasses that of neutral vacancies. Notably, these oxygen vacancies exhibit negative-U behavior, indicating that the +1 charge state is unstable across all vacancy types. The transition levels \(\varepsilon\)(0/2+) for the vacancies \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}1}\), \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}2}\), \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}3}\), \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}4}\), \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}5}\) and \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}6}\) are found to be 3.612, 2.852, 3.592, 3.682, 3.792 and 2.565 eV, respectively, all situated ~1 eV below the CBM. These findings indicate that oxygen vacancies function as deep donors and do not contribute to n-type conductivity. Among these vacancies, the lowest energy configuration for \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}^{0}\) is at the \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}6}\) site. This is due to the longest Ga-O bond lengths around the oxygen vacancies, suggesting that vacancy formation at the \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}6}\) site is energetically favorable.

The formation energy of oxygen vacancies is also influenced by growth conditions via the oxygen chemical potential \({\mu }_{{{\rm{O}}}}\). As depicted in Fig. 6a, the formation energy of an oxygen vacancy at the specific site \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}6}\) differs for both neutral and doubly charged states as a function of \({\mu }_{{{\rm{O}}}}\). The equilibrium Fermi level is observed to increase toward the conduction band with decreasing \({\mu }_{{{\rm{O}}}}\), as shown in Fig. 6b. In oxygen-poor conditions (lower \({\mu }_{{{\rm{O}}}}\)), the formation energies for ionized oxygen vacancies decrease, leading to a higher concentration of excess electrons in the conduction band. Furthermore, the concentration of vacancies at different charge states and the dominant charge state depends on \({\mu }_{{{\rm{O}}}}\). A critical value for the oxygen chemical potential \({\mu }_{{{\rm{O}}}}^{{{\rm{critical}}}}\) exists, below which neutral oxygen vacancies are thermodynamically preferred, while charged vacancies dominate at higher values. A critical value for the oxygen chemical potential \(({\mu }_{{{\rm{O}}}}^{{{\rm{critical}}}})\), indicates the point at which neutral oxygen vacancies are preferred below this level, while charged vacancies become predominant above this threshold. At this critical \({\mu }_{{{\rm{O}}}}\), the equilibrium Fermi level aligns with the thermodynamic transition level, marking a transition in the predominant oxidation state in Fig. 6b, c. Under oxygen-poor conditions, the concentration of neutral vacancies significantly increases and predominates over charged vacancies, as illustrated in Fig. 6c. Conversely, in oxygen-rich environments, the concentration of charged vacancies remains low, typically below 1.56 \(\times {10}^{9}\,{{{\rm{cm}}}}^{-3}\) at room temperature. However, it is important to note that, under certain Fermi level and chemical potential conditions, the calculated equilibrium concentration of oxygen vacancies can be extremely low, even unphysically low, as indicated in Fig. 6c, where concentrations fall below 10−4 cm−3 and as low as 10−34 cm−3. This reflects the limits of equilibrium defect chemistry, emphasizing that in real materials, non-equilibrium effects, kinetic limitations, or the presence of other defect types can modify the actual defect landscape. Our research results indicate that in thermodynamically stable amorphous κ-Ga2O3, oxygen vacancies predominantly exist in a neutral charge state. This further suggests that the neutral \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}\) with low formation energy could significantly influence the defect energy levels in the mid-gap.

a Formation energy of the oxygen vacancy at a low-energy O site (\({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}6}\)) as a function of the Fermi level across various growth conditions. The shaded region represents the formation energy range between the extreme O-rich and O-poor conditions. b Equilibrium Fermi level (relative to the VBM, E-Fermieq – EVBM) as a function of the oxygen chemical potential. c Equilibrium concentrations of neutral and doubly charged oxygen vacancies as a function of the oxygen chemical potential.

To further elucidate the relationship between transition levels and local environments, we examined atomic relaxation around \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}\) in relation to the atomic positions of the pristine structure. In the neutral oxygen vacancy, atomic relaxation manifests as a combination of expansion and contraction. Ga atoms migrating toward the vacancy (positive displacement) exhibit markedly decreased charge density, indicating electron localization on these Ga atoms, which is supported by the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) wavefunctions of \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}^{0}\) shown in Fig. 7. Conversely, in the positive charge states, all Ga atoms are displaced away from the vacancy (negative displacement), with \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}^{2+}\) showing more pronounced displacements compared to \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}^{1+}\). Notably, the Ga ions adjacent to the \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}^{2+}\) vacancy exhibit unusually large outward displacements. \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}6}\) surrounded larger atomic displacements compared to other vacancies in both the 0 and +2 charge states, resulting in \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}6}\) having lower formation energies and deeper charge transition levels.

Optical properties

An in-depth understanding of the optical properties of κ-Ga2O3, particularly concerning oxygen vacancies, is essential for its application in optoelectronic devices. The dielectric function \(\varepsilon \left({{\rm{\omega }}}\right)\) describes the crystal linear response to electromagnetic radiation and highlights the interaction between photons and electrons. The complex dielectric function is expressed as \({{\rm{\varepsilon }}}({{\rm{\omega }}})\,=\,{\varepsilon }_{1}({{\rm{\omega }}})\,+\,i{{{\rm{\varepsilon }}}}_{2}({{\rm{\omega }}})\,\), where the imaginary part can be represented by the equation33:

where e is the electron charge, \(m\) is the free electron mass, and M refers to the dipole matrix element. The real part is derived using the Kramers–Kronig relationship33:

with P denoting the principal value of the integral. Subsequent optical properties, including the absorption coefficient \(\alpha \left(\omega \right)\), reflectivity \(R\left(\omega \right)\), refractive index \(n\left(\omega \right)\) and energy-loss function \(L(\omega )\), are entirely derived from the complex dielectric function33:

Figure 8a, b illustrates the real and imaginary components of the complex dielectric function across a broad energy range of 0–100 eV. The most pronounced peak in the imaginary part, situated around 3.5 eV, corresponds to inter-band transitions from the O-2p valence band to the Ga-4s conduction band.

The absorption coefficient in Fig. 8c reveals new peaks at 3.06, 3.46, 3.83, 3.84, 3.47, and 4.24 eV for \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}1}\) through \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}6}\), with the first two peaks located within the visible spectrum. Figure 8d, e depicts reflectivity and the complex refractive index. For intrinsic κ-Ga2O3, both properties exhibit a nearly constant behavior in the low-energy range. The refractive index is 2.07, which is in good agreement with the refractive index\({n}\) and absorption coefficient κ-Ga2O3 measured by spectral ellipsometry in our experiments on sapphire heteroepitaxial κ-Ga2O3, showing values ranging from 1.95 to 2.04 in the wavelength range of 380–1000 nm. However, with the introduction of oxygen vacancies, an increase in reflectivity and refractive index is observed, accompanied by additional peaks linked to defect levels within the bandgap. The presence of absorption and reflectivity peaks reduces the transparency of κ-Ga2O3, limiting its potential as a transparent coating for applications ranging from visible to deep UV light.

The energy-loss function (ELF) presented in Fig. 8f illustrates the energy consumed by an electron moving through a homogeneous dielectric medium. The ELF spectra reveal distinct energy ranges corresponding to electronic excitations of various orbitals, facilitating comparisons with spectroscopic measurements such as electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS), which provide insights into the electronic interactions with an incident electron beam.

The calculated ELF for intrinsic κ-Ga2O3 aligns closely with experimental data, featuring a broad band between 5 and 75 eV. For intrinsic κ-Ga2O3, the significant characteristic peaks are identified at 25.62 eV. These peaks are critical for understanding the electronic structure and optical properties of κ-Ga2O3. Energy loss peaks associated with oxygen vacancies \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}1}\) to \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}6}\) are identified at 3.19, 3.29, 3.46, 3.51, 3.57, and 3.73 eV. These energy loss peaks correspond to regions of significant reflectivity decline, indicating the impact of oxygen vacancies on the optical properties of κ-Ga2O3, corresponding to regions of significant reflectivity decline. We have also provided additional results for the +1 and +2 charge states (see Supplementary Figs. S1, S2). The charged oxygen vacancies introduce more defect electronic states compared to neutral oxygen vacancies, significantly affecting the energy loss peaks, static dielectric constant, and optical properties of κ-Ga2O3. Specifically, the charged oxygen vacancies enhance the reflectivity and refractive index in the low-energy region, and increase the absorption coefficient in the visible and infrared regions.

Optical transition calculations reveal two distinct types of transitions in κ-Ga2O3, enhancing our understanding of its optical properties. Type I transitions, observed in \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}^{0}\) and \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}^{+1}\), involve transitions from occupied defect states to conduction band. Type II transitions occur in \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}^{+1}\), moving from VBM to unoccupied defect states, as illustrated in Fig. 9. Type I transitions exhibit high oscillator strength (f), occurring from occupied defect states to resonant states above the CBM, producing transition energies greater than the difference between defect levels and the CBM. The VBM comprises O p orbitals, while the CBM is dominated by O and Ga s orbitals. \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}\) defects introduce localized states within the bandgap and alter conduction band, creating resonant states above the CBM with diverse molecular orbital symmetries that enable strong dipole transitions. Similar behavior has been noted in α-Al2O3 and monoclinic HfO234,35.

Illustrates the molecular orbitals (MOs) associated with the occupied defect level in \(\kappa\)-Ga2O3, highlighting the electronic transitions that occur due to the presence of the \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}\) defect. Correspondingly, the LUMO + 1 level of \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}^{0}\) in \(\kappa\)-Ga2O3, emphasizing its role in the optical properties of the material. This depiction aids in understanding how these electronic structures contribute to the overall optical behavior of \(\kappa\)-Ga2O3.

Optical transition energies correlate with defect energy levels, indicating that deeper defect levels correspond to higher optical transition energies. For \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}^{0}\), the strongest transition occurs around 4.16–4.29 eV, except for \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}^{5}\) and \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}^{6}\), which show transitions at 3.45 eV and 5.02 eV, respectively. Transition energies for \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}^{+1}\) are lower than those for \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}^{0}\), with differences exceeding 1.0 eV for \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}^{+1}\) and \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}4}^{+1}\). In \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}^{+1}\), transition energies are nearly identical around 4.6–4.8 eV, except for \({V}_{O6}\), which has a lower transition energy of 4.09 eV and an oscillator strength of 0.05. Based on the comparison with experimental data, two broad peaks associated with \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}\) in κ-Ga2O3 films can be identified: one in the range of 2.5–3.5 eV (likely corresponding to optical transitions in \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}^{0}\) or \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}^{+1}\)) and another in the range of 3.5–4.5 eV (attributed to transitions in \({V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}^{+1}\)). These findings are consistent with the observed absorption spectrum in the undoped κ-Ga2O3 films25,28,36.

Conclusions

In this study, we have systematically investigated the thermodynamic, electronic, and optical properties of oxygen vacancies in κ-Ga2O3 using first principles calculations. Our findings reveal that oxygen vacancies introduce deep donor levels within the bandgap, significantly influencing the electronic structure and charge dynamics of κ-Ga2O3. The analysis of the density of states confirms that these vacancies lead to new defect states, which correlate with observed experimental defect levels, elucidating their role as critical factors in determining the electronic behavior. We demonstrated that the formation energy of oxygen vacancies varies with the Fermi level and growth conditions, highlighting a preference for neutral vacancies under oxygen-poor environments. This indicates that oxygen vacancies can significantly impact the electrical conductivity and charge transport mechanisms, particularly through the formation of polarons. Optically, the presence of oxygen vacancies introduces additional absorption peaks in the ultraviolet region. Our work provides a comprehensive understanding of the effects of oxygen vacancies on the electronic and optical properties of κ-Ga2O3, laying a solid foundation for future defect engineering strategies aimed at optimizing the performance of κ-Ga2O3-based devices.

Methods

We perform DFT calculations using the projector augmented wave (PAW) method within the QUANTUM ESPRESSO code37. A plane-wave energy cutoff of 450 eV is employed, with Brillouin-zone integration conducted using a Γ-centered 4 × 4 × 4 k-point mesh for the primitive cell and a 2 × 2 × 2 mesh for the supercell. Spin polarization was included for all defective structures to account for possible unpaired electrons. A 2 × 2 × 1 supercell containing 160 toms was used for defect calculations, which ensures sufficient separation between periodic images of defects. The PAW potentials are based on the valence-electron configurations 4 s²4p¹ for Ga and 2 s²2p⁴ for O. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) of Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) is employed to optimize the structural parameters with the fixed lattice constants until the residual forces are less than 0.01 eVÅ−1. We then used Heyd-Scuseria-Ernzerhof (HSE) hybrid functional to accurately calculate the electronic structure and optical properties. It is noted that the validity of the PBE relaxation with HSE single-point calculations and the HSE relaxation are discussed in Supplementary Fig. S3. The mixing parameter of HSE was set to α = 0.35 with a screening parameter μ = 0.2 Å−1, resulting in a band gap of 4.62 eV for κ-Ga2O3, in close agreement with the experimental value of 4.60 eV28,38. For all structural optimization, atomic positions are fully relaxed until the Hellmann-Feynman force on each atom is below 0.01 eV/Å. The self-consistent field (SCF) cycles were iterated until the energy difference between successive steps was less than 10⁻⁶ eV. The formation energy of oxygen vacancies for different charge states is given by follow:

The formation energy of oxygen vacancies in various charge states is given by the difference between the total energy of the supercell containing the vacancy \({E}_{{{\rm{tot}}}}[{V}_{{{\rm{O}}}}^{q}]\) and that of a perfect crystal \({E}_{{{\rm{tot}}}}[{{{\rm{Ga}}}}_{2}{{{\rm{O}}}}_{3}]\). The removed oxygen is associated with a reservoir, referenced to the energy of an O₂ molecule. The oxygen chemical potential \({\mu }_{{{\rm{O}}}}\) can vary to reflect experimental conditions during growth or annealing, spanning O- poor to O-rich environments. The Fermi level is referenced to the valence band maximum of the bulk cell with band alignment corrections. \(\Delta V\) is a finite-size correction term for charged defects39,40. The dielectric constant (13.2) of κ-Ga2O3 used in this study was taken from previously reported values6. The equilibrium Fermi level and the concentration of oxygen vacancies in each charge state are calculated self-consistently, with defect concentrations derived from their formation energies using a Boltzmann expression41.

Data availability

The data that support the conclusions of this study are available in the paper and the Supplementary files or from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Additional result, discussion and figure are provided in Supplementary Information. The atomic coordinates of the optimized computational models and the numerical source data underlying the graphs and charts are provided in Supplementary Data 1.

References

Roy, R., Hill, V. & Osborn, E. Polymorphism of Ga2O3 and the system Ga2O3-H2O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 74, 719–722 (1952).

Weiser, P., Stavola, M., Fowler, W. B., Qin, Y. & Pearton, S. Structure and vibrational properties of the dominant O-H center in β-Ga2O3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 232104 (2018).

Zheng, R. et al. p-IrOx/n-β-Ga2O3 heterojunction diodes with 1-kV breakdown and ultralow leakage current below 0.1 μA/cm2. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 71, 1587–1591 (2024).

Tan, S. W., Chang, C. W., Jiang, Z. H. & Lin, K. W. Study of a platinum nanoparticles/indium gallium oxide based ammonia gas sensor and a gas sensing model for internet of things (IoT) application. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 72, 813–821 (2025).

Feng, W. et al. Critical role of dopant bond strength in enhancing the conductivity of n-type doped κ-Ga2O3. Phys. Let. A 511, 129546 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. ε-Ga2O3: a promising candidate for high-electron-mobility transistors. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 1–1, https://doi.org/10.1109/LED.2020.2995446 (2020).

Feng, W., Chen, X., Liang, J., Wang, G. & Pei, Y. First-principles prediction of κ-Ga2O3: N ferromagnetism. J. Phys. Chem. C 128, 7733–7741 (2024).

Oshima, Y., Víllora, E. G., Matsushita, Y., Yamamoto, S. & Shimamura, K. Epitaxial growth of phase-pure ε-Ga2O3 by halide vapor phase epitaxy. J. Appl. Phys. 118, 085301 (2015).

Xia, X. et al. Hexagonal phase-pure wide band gap ε-Ga2O3 films grown on 6H-SiC substrates by metal organic chemical vapor deposition. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 202103 (2016).

Che, C. et al. High performance solar-blind photodetectors based on MOCVD grown β-Ga2O3 with hydrogen plasma treatment. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 40, 055005 (2025).

Boschi, F. et al. Hetero-epitaxy of ε-Ga2O3 layers by MOCVD and ALD. J. Cryst. Growth 443, 25–30 (2016).

Cho, S. B. & Mishra, R. Epitaxial engineering of polar ε-Ga2O3 for tunable two-dimensional electron gas at the heterointerface. Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 162101 (2018).

Mezzadri, F. et al. Crystal structure and ferroelectric properties of ε-Ga2O3 films grown on (0001)-sapphire. Inorg. Chem. 55, 12079–12084 (2016).

McCluskey, M. D. Point defects in Ga2O3. J. Appl. Phys. 127, 101101 (2020).

Liu, L. L. et al. Fabrication and characteristics of N-doped β-Ga2O3 nanowires. Appl. Phys. A 98, 831–835 (2010).

Farzana, E., Chaiken, M. F., Blue, T. E., Arehart, A. R. & Ringel, S. A. Impact of deep level defects induced by high energy neutron radiation in β-Ga2O3. APL Mater. 7, 022502 (2019).

Hong, Z. et al. Low turn-on voltage and reverse leakage current β-Ga2O3 MIS Schottky barrier diodes with an AlN interfacial layer. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 71, 6934–6941 (2024).

Yoo, J.-H., Rafique, S., Lange, A., Zhao, H. & Elhadj, S. Lifetime laser damage performance of β-Ga2O3 for high power applications. APL Mater. 6, 036105 (2018).

Zacherle, T., Schmidt, P. C. & Martin, M. Ab initio calculations on the defect structure of β-Ga2O3. Phys. Rev. B 87, 235206 (2013).

Varley, J. B., Weber, J. R., Janotti, A. & Van de Walle, C. G. Oxygen vacancies and donor impurities in β-Ga2O3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 142106 (2010).

Dong, L., Jia, R., Xin, B., Peng, B. & Zhang, Y. Effects of oxygen vacancies on the structural and optical properties of β-Ga2O3. Sci. Rep. 7, 40160 (2017).

Lyons, J. L. Electronic Properties of Ga2O3 Polymorphs. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 8, Q3226–Q3228 (2019).

Mazzolini, P. et al. Engineering shallow and deep level defects in κ-Ga2O3 thin films: comparing metal-organic vapour phase epitaxy to molecular beam epitaxy and the effect of annealing treatments. Mater. Today Phys. 45, 101463 (2024).

He, X., Wang, M., Meng, J., Hu, J. & Jiang, Y. The effect of vacancy defects on the electronic properties of β-Ga2O3. Comput. Mater. Sci. 215, 111777 (2022).

Li, S. et al. Oxygen vacancies modulating the photodetector performances in ε-Ga2O3 thin films. J. Mater. Chem. C. 9, 5437–5444 (2021).

Peelaers, H. & Van De Walle, C. G. Brillouin zone and band structure of β-Ga2O3. Phys. Status Solidi b 252, 828–832 (2015).

Wang, Y. et al. Recent progress on the effects of impurities and defects on the properties of Ga2O3. J. Mater. Chem. C. 10, 13395–13436 (2022).

Pavesi, M. et al. ε-Ga2O3 epilayers as a material for solar-blind UV photodetectors. Mater. Chem. Phys. 205, 502–507 (2018).

Zhu, B., Kavanagh, S. R. & Scanlon, D. easyunfold: A Python Package for Unfolding Electronic Band Structures (Zenodo, 2024).

Janotti, A. & Van de Walle, C. G. Oxygen vacancies in ZnO. Appl. Phys. Lett. 87, 122102 (2005).

Lee, J., Lu, W. D. & Kioupakis, E. Electronic and optical properties of oxygen vacancies in amorphous Ta2O5 from first principles. Nanoscale 9, 1120–1127 (2017).

Matsunaga, K., Tanaka, T., Yamamoto, T. & Ikuhara, Y. First-principles calculations of intrinsic defects in Al2O3. Phys. Rev. B 68, 085110 (2003).

Hao, L. Y., Du, J. L. & Fu, E. G. Theoretical study on structural and optical properties of β-Ga2O3 with O vacancies via shell DFT-1/2 method. J. Appl. Phys. 134, 085101 (2023).

Dicks, O. A., Cottom, J., Shluger, A. L. & Afanas’ev, V. V. The origin of negative charging in amorphous Al2O3 films: the role of native defects. Nanotechnology 30, 205201 (2019).

Muñoz Ramo, D., Gavartin, J. L., Shluger, A. L. & Bersuker, G. Spectroscopic properties of oxygen vacancies in monoclinic Al2O3 calculated with periodic and embedded cluster density functional theory. Phys. Rev. B 75, 205336 (2007).

Yang, Y. et al. In-depth investigation of low-energy proton irradiation effect on the structural and photoresponse properties of ε-Ga2O3 thin films. Mater. Des. 221, 110944 (2022).

Giannozzi, P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 21, 395502 (2009).

Heyd, J., Scuseria, G. E. & Ernzerhof, M. Hybrid functionals based on a screened Coulomb potential. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 8207–8215 (2003).

Freysoldt, C., Neugebauer, J. & Van de Walle, C. G. Fully ab initio finite-size corrections for charged-defect supercell calculations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 016402 (2009).

Freysoldt, C., Neugebauer, J. & Van De Walle, C. G. Electrostatic interactions between charged defects in supercells. Phys. Status Solidi b. 248, 1067–1076 (2011).

Van de Walle, C. G. & Neugebauer, J. First-principles calculations for defects and impurities: applications to III-nitrides. J. Appl. Phys. 95, 3851–3879 (2004).

Cora, I. et al. The real structure of ε-Ga2O3 and its relation to κ-phase. CrystEngComm 19, 1509–1516 (2017).

Zhang, Z.-C., Wu, Y. & Ahmed, S. First-principles calculation of electronic structure and polarization in ε -Ga2O3 within GGA and GGA + U frameworks. Mater. Res. Express 6, 125904 (2019).

Kim, J., Tahara, D., Miura, Y. & Kim, B. G. First-principle calculations of electronic structures and polar properties of (κ,ε)-Ga2O3. Appl. Phys. Express 11, 061101 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Young Innovative Talents Project for General University in Guangdong Province (2025KQNCX085), Guangdong Hilly Agriculture Intelligent Equipment Engineering Technology Research Center (2025GCZX010), National Key Research and Development Program (2024YFE0205300), Science and Technology Development Plan Project of Jilin Province, China (No. YDZJ202303CGZH022), Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (No. 20231127114207001), Open Fund of the State Key Laboratory of Optoelectronic Materials and Technologies (OEMT-2023-KF-05), respectively.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: W.F., J.L., and Y.P.; methodology: W.F. and Z.L.; investigation: P.F., Y.P, Y.Z., D.Z., and Z.L; writing original draft: W.F. and Y.P.; writing review & editing: W.F., P.F., Y.Z., D.Z., J.L., X.W. and Y.P., funding acquisition: W.F., J.L., X.W. and Y.P.; resources: W.F., J.L. and Y.P.; supervision: W.F., J.L. and Y.P.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Feng, W., Fang, P., Zhang, Y. et al. The role of oxygen vacancies in the electronic and optical properties of κ-Ga2O3. Commun Chem 9, 36 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01843-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01843-1