Abstract

The urgent need to phase out SF6, an extremely potent greenhouse gas prevalent in electrical grids, drives the search for eco-friendly insulation alternatives. Trifluoromethanesulfonyl fluoride (CF3SO2F) emerges as a promising candidate due to its excellent properties. However, understanding its thermal decomposition pathways and products under operationally relevant conditions is critical for evaluating its environmental feasibility and mitigating potential risks upon accidental release or during fault events. This study investigates the thermal decomposition mechanisms of CF3SO2F using a deep learning potential that combines ab initio accuracy with empirical MD efficiency. By leveraging machine learning driven molecular dynamics, we systematically analyze the yields and components of decomposition products versus temperatures, gas mixing ratios, and buffer gas. The results reveal that the bond-breaking pathways are temperature-dependent, with both elevated temperatures and higher buffer gas mixing ratios promoting its decomposition. Elevated gas pressure enhances the decomposition process by increasing the collision frequency among reactant species. Additionally, N2 exhibits an inhibitory effect on decomposition under high pressure compared to CO2. Experimental validation via a thermal decomposition platform confirms characteristic decomposition products. These findings are pivotal for guiding the rational design and safe deployment of CF3SO2F to achieve substantial greenhouse gas mitigation in the power industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Insulating gases play an irreplaceable role in power systems. Sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) has been widely used as an insulating gas in power equipment such as switchgear and transmission pipelines due to its excellent insulation and arc extinguishing properties1,2. However, the potential greenhouse effect caused by high global warming potential (GWP = 23900) and atmospheric lifetime (3200 years) of SF6 will have an irreversible impact on the atmosphere and the earth’s environment, and it is imperative to explore the green and eco-friendly new insulation medium3,4,5,6. Researchers have done much work in SF6 alternative gases7,8. So far, some gases with comparatively high insulating properties, such as CF3I, C5F10O, and C4F7N, and their mixtures are being investigated as SF6 replacement gases9,10,11. However, they have different defects in dielectric strength, liquefaction temperature, GWP, toxicity, stability and so on. Even C4F7N, the most popular gas in SF6 substitution research, faces the challenge of high liquefaction temperature, making its application in alpine areas difficult12.

In recent years, trifluoromethylsulfonyl fluoride (CF3SO2F) has proven to be an eco-friendly insulation replacement gas with excellent potential and performance. Not only the AC and DC breakdown voltage of CF3SO2F can be increased to 1.3–1.6 times that of SF6 under the same conditions, but also the GWP of CF3SO2F (3678) is much lower than that of SF613,14. In addition, the lower liquefaction temperature (–22 °C), excellent gas-solid compatibility, low toxicity, and high stability of CF3SO2F have been proven15,16. However, gaseous dielectrics can decompose under discharge or localized overheating faults, forming inevitable byproducts. The study of the decomposition characteristics of gas-insulating media is an essential indicator of its reliability, closely related to its self-recovery and insulation performance17,18,19. Wang et al. analyzed the possible decomposition pathways and byproducts of CF3SO2F by quantum chemical methods15. Our team calculated the equilibrium composition, thermodynamic properties, and transport coefficients of CF3SO2F gas mixtures and found that the gas mixing ratio and pressure affect the thermophysical and transport properties of CF3SO2F gas mixtures20,21. Despite these contributions, current kinetic and thermodynamic studies present fundamental limitations. Existing research often overlooks the dynamic decomposition properties of CF3SO2F, especially under varying conditions, which impedes risk assessment and safe deployment22. The experimental difficulties and high costs associated with such studies exacerbate these gaps, resulting in a lack of comprehensive insights into the micro-mechanisms underlying these processes23,24.

Theoretical approaches are powerful tools to study the dynamic decomposition properties of CF3SO2F mixtures at the atomic level15,25. The molecular simulation community has long faced the problem of accuracy and efficiency in modeling potential energy surfaces and interatomic forces. For instance, although the ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations based on density functional theory (DFT) could show sufficient accuracy in describing chemical reactions that contain bond cleavage and formation, its computational cost of such high-level methods would limits their application to systems with hundreds to thousands of atoms26,27. Conversely, empirical and reactive force fields allow for larger and longer simulations24,28,29,30,31. However, parameters fitting in these methods are usually lengthy processes, and their accuracy and transferability are often questioned. Therefore, a theoretical approach with quantum chemical accuracy and lower computational resource requirements is needed for high-precision simulations of the dynamic thermal decomposition process of CF3SO2F gas mixtures. Over the past few years, machine learning methods using DFT data have achieved some notable successes in the characterization of molecular macrosystems32,33,34. Deep learning potential (DLP) developed on machine learning can automatically extract features from DFT data for deep neural network training and achieve preset accuracies35,36. DLP can take into account the time cost of empirical force fields while maintaining accuracy in ab initio. Yang et al. have successfully used DLP to simulate the dynamic and complex decomposition process of urea in water37.

Inspired by machine learning-based approaches to molecular simulations, a neural network-based machine learning potential with comparable accuracy to ab initio and comparable efficiency to empirical potential-based molecular dynamics was developed to describe the dynamic thermal decomposition of CF3SO2F mixtures. Based on the machine-learning potential-driven molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the decomposition mechanism of CF3SO2F mixtures at different temperatures and gas mixing ratios and components of the main decomposition products were obtained. The effects of the CF3SO2F mixing ratio on the decomposition of the CF3SO2F mixture were analyzed to reveal the mechanism of the thermal decomposition of the CF3SO2F mixture under different pressures. Compared with CO2, N2 as a buffer gas can inhibit the decomposition of CF3SO2F to a certain extent. The thermal decomposition properties of CF3SO2F gas mixtures were experimentally investigated using a constructed thermal decomposition platform, and characteristic decomposition products aiming to characterize the failure were proposed. This work provides significant insight into the thermal decomposition behavior of CF3SO2F and its mixtures, contributing to the understanding of its stability and decomposition pathways under extreme conditions. Furthermore, the computational framework is potentially transferable for investigating the physicochemical properties and decomposition mechanisms of other promising insulating gases, guiding the development of eco-friendly alternatives to SF6.

Results

DLP training and structure of simulation boxes

Figure 1 illustrates the workflow involved in training DLP and calculating the decomposition products of CF3SO2F at various temperatures based on DLP. Initially, a potential is trained on a dataset composed of structures randomly selected from the AIMD reaction trajectories of a model with well-determined elemental and molecular configurations. This initial potential serves as a starting point for an iterative training process. Subsequently, the DLP of CF3SO2F is developed and trained using potentials, forces, and virials from the AIMD dataset, which consists of a temperature range from 300 K to 3200 K in the NVT ensemble35. Through multiple explorations, labeling, and training, we compiled a comprehensive dataset of the CF3SO2F gas mixture configurations across a wide range of temperatures27,38. The DLP was trained and fine-tuned after the dataset was built, and extensive validation tests confirmed that it would produce only small errors. Detailed information on the settings used for AIMD computation and DLP training is given in the methods section.

The workflow comprises four key steps: (1) Configuration sampling from AIMD trajectories, (2) Training of the DLP, (3) Validation of the DLP against DFT benchmarks, and (4) Large-scale molecular dynamics simulations of CF3SO2F decomposition across a range of temperatures (T1 to Tn), with supercell size adjusted to model different system pressures.

The reliability of the deep learning potential for modeling reactive events was rigorously validated. Initially, a machine-learning potential was trained on a dataset constructed by systematically sampling structures at regular time intervals from the AIMD reaction trajectories. This procedure ensures that the dataset captures a representative ensemble of the well-defined, chemically relevant configurations sampled during the reactive dynamics, covering both stable intermediates and transition regions, as shown in Fig. S1. The dataset is randomly divided into a training set (comprising 90% of the structures) and a validation set (comprising 10% of the structures). The training set was employed to fit a neural network, with internal validation performed using the validation set to ensure that the error on the validation set is not significantly higher than that on the training set. As illustrated in Fig. S2, the trained potential function accurately reproduces the DFT data, yielding a root-mean-square error (RMSE) of merely 1.3 meV for the total energy of each atom. The RMSE for the forces is 0.023 eV/Å, and the RMSE for the virials per atom is 2.5 meV, closely aligning with the DFT results. The deviation distribution plots for energy, force, and virials are all centered around zero, indicating the model’s robust predictive capability.

To quantitatively assess the potential’s accuracy, the potential energy surfaces of the CF3SO2F molecule with changing CF3−SO2F, F−CF2SO2F, F−CF3SO2, and O−CF3SOF bond lengths were computed with both the DLP and the reference DFT method, showing excellent agreement (Fig. S3). Moreover, the DLP’s description of key stationary points was consistent with high-level CCSD(T) reference data from the literature15. These results consistently identify C–S bond homolysis as the dominant initial decomposition step, followed by dissociation of the resulting radical, which confirms its transferability and robustness for probing the decomposition mechanism. The principal advantage of the DLP approach lies in its capacity to go beyond static energy calculations and provide statistically meaningful insights into finite-temperature reaction dynamics, including product branching ratios, at a computational cost inaccessible to direct ab initio molecular dynamics. Finally, the trained DLP was utilized to simulate the CF3SO2F/CO2 gas mixture (hereafter denoting a mixture of CF3SO2F in a CO2 buffer gas) at various temperatures.

Molecular dynamics simulations using the trained DLP were conducted with LAMMPS39. Seven initial simulation boxes under different states, which contain at least 10,000 atoms to simulate the real environment, were created by randomly placing the molecules in a cubic box, as detailed in Table 1. For instance, simulation box No. 3 comprises 500 CF3SO2F molecules and 3667 CO2 molecules, totaling 15,001 atoms, with a cubic box side length of 553.24 Å and a 0.002328 g/cm³ density. This configuration corresponds to an actual condition of a 12% CF3SO2F/CO2 gas mixture at 25 °C and 0.1 MPa.

It has been demonstrated that CF3SO2F gas mixtures with less than 20% CF3SO2F mixing ratio are more advantageous for engineering applications40,41. To investigate the decomposition of CF3SO2F gas mixtures under different mixing ratios and the impact of these mixing ratios on decomposition, simulations were performed with varying CF3SO2F mixing ratios. No.1 and No.2 simulation boxes maintain the total CF3SO2F molecules fixed and simulate 20% CF3SO2F/CO2 and 14% CF3SO2F/CO2 systems, respectively. Similarly, No.6 and No.7 simulation boxes keep the total number of molecules constant to simulate the same systems. In addition, simulation boxes No. 4 and No. 5 represent the decomposition of 12% CF3SO2F/CO2 gas mixture at 0.3 MPa and 0.5 MPa to investigate the effect of pressure on decomposition respectively. The simulation boxes for CF3SO2F/N2 (hereafter denoting a mixture of CF3SO2F in a N2 buffer gas) under different conditions were built according to the same approach as shown in Table S1.

Decomposition of CF3SO2F

The two primary causes of decomposition in the insulating dielectric region are localized overheating faults and high temperatures resulting from localized (corona) or arc discharges24. The temperature in the core region of a localized discharge ranges from 700 to 1200 K, while in the arc discharge region, it spans from 3000 to 12000 K. To investigate the effect of temperature on the decomposition characteristics of the gas mixture, molecular dynamics simulations of the model were conducted in the range of 300 K to 3200 K. CF3SO2F in CF3SO2F/CO2 begins to decompose at 1400 K, indicating that it remains stable in the presence of localized discharges as shown in Fig. 2a.

a Decomposition time evolution at 0.1 MPa with different temperatures in 12%CF3SO2F/88%CO2 mixture. b Decomposition time evolution at 2200 K with different pressures in 12%CF3SO2F/88%CO2 mixture. c Decomposition time evolution at 2200 K and 0.1 MPa with different mixing ratios in CF3SO2F/CO2 mixtures. d Final decomposition ratios after 1000 ps under different conditions in CF3SO2F/CO2 and CF3SO2F/N2 mixtures. e Decomposition time evolution at 2200 K with different pressures in 12%CF3SO2F/88%N2 mixture. f Decomposition time evolution at 2200 K and 0.1 MPa with different mixing ratios in CF3SO2F/N2 mixtures.

The buffer gas CO2 does not decompose between 1400 K and 2200 K, aligning with previous studies24. As the temperature increases from 1400 to 2200 K, the decomposition rate of CF3SO2F rises, with the decomposition ratio (the percentage of decomposed CF3SO2F) within 1000 ps increasing from 0.07 to 0.77, as illustrated in Fig. 2d. When the temperature reaches 3200 K (Fig. 2a), the decomposition ratio of CF3SO2F surges to 0.94 within 1000 ps, indicating rapid decomposition in the arc discharge channel.

We further investigate the effect of pressure on the decomposition behavior of CF3SO2F. The decomposition of CF3SO2F under pressures of 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 MPa at 2200 K is shown in Fig. 2b. The decomposition rate and ratio of CF3SO2F increase with rising pressure. The decomposition ratio of CF3SO2F reaches to 0.87 and 0.94 at 0.3 and 0.5 MPa, respectively. This trend can be attributed to the increased pressure raising the concentration of molecules, thereby increasing the probability of intermolecular collisions and accelerating the decomposition rate and ratio of CF3SO2F.

To uncover the effect of gas mixing ratios on decomposition, the time evolution of CF3SO2F decomposition for different CF3SO2F/CO2 gas mixture systems at 2200 K is illustrated in Fig. 2c. Compared to 12%CF3SO2F/88%CO2 (0.77), the decomposition ratio of 14%CF3SO2F/86%CO2 (0.74) and 20%CF3SO2F/80%CO2 (0.64) within 1000 ps decrease sequentially. To address the potential influence of varying total system size, we employed two distinct modeling strategies. One strategy maintained a constant total number of molecules for all mixture ratios to directly control for system size effects. Conversely, the other strategy kept the number of CF3SO2F reactant molecules constant and varied only the number of buffer gas (N2 or CO2) molecules. The decomposition results from both approaches, analyzed over consistent time spans, are presented in Fig. S4. A similar result that the increased CF3SO2F mixing ratio would suppress the decomposition of the mixture can be observed. This may be primarily attributed to changes in molecular interactions and reaction kinetics. As the mixing ratio of CF3SO2F increases, the intermolecular forces, such as van der Waals forces and dipole-dipole interactions between CF3SO2F molecules42,43, become more significant. These interactions enhance the overall stability of the system, effectively suppressing the decomposition pathways. Moreover, in mixtures with a higher mixing ratio of CF3SO2F, a greater proportion of the collision energy is transferred into vibrational modes. Since CF3SO2F possesses more vibrational degrees of freedom than CO2 as shown in Tables S2 and S3, a higher proportion of the total energy is stored in these modes rather than in translation and rotation. This reduces the fraction of effective collisions where the energy in the translational and rotational degrees of freedom exceeds the activation barrier for decomposition, thereby lowering the reaction rate. The decomposition behavior of CF3SO2F remained consistent across different mixture ratios, regardless of the mixing gas model employed. The consistent decomposition behavior obtained from both the constant total number and constant CF3SO2F number approaches confirms the robustness of our findings.

As another commonly used buffering gas, N2 was systematically investigated to elucidate its influence on the thermal decomposition characteristics of CF3SO2F. Figures S5 and Fig. 2e, f present the decomposition trends of CF3SO2F/N2 mixtures under various temperatures, pressures, and mixing ratios conditions. Notably, the parametric dependencies observed in N2-based mixtures mirror those in CF3SO2F/CO2 systems, confirming the generalizability of our previous findings. However, the decomposition ratios of CF3SO2F in N2-buffered mixtures (ranging from 0.79 to 0.87) are notably lower than those observed in CO2-buffered systems (ranging from 0.87 to 0.94) at elevated pressures (0.3–0.5 MPa), as shown in Fig. 2d. This consistency was further verified by three separate simulations employing N2 or CO2 as buffer gases, respectively, as shown in Fig. S6. This statistically significant discrepancy indicates that N2 offers greater effectiveness in suppressing the thermal decomposition of CF3SO2F, highlighting its potential as a more efficient buffering gas in high-pressure applications. The differing effects of N2 and CO2 buffer gases on CF3SO2F decomposition stem from their distinct vibrational energy transfer efficiencies. Analysis of their vibrational spectra reveals that CO2, as a linear triatomic molecule, possesses low-frequency modes that effectively couple with the vibrational modes of excited CF3SO2F as shown in Tables S2 and S3. This facilitates resonant energy transfer during collisions, promoting greater energy accumulation in CF3SO2F and resulting in the observed higher decomposition yield in CO2 mixtures compared to N2, where such efficient vibrational coupling is absent.

Main decomposition products distribution and evolution

Figure S7a illustrates decomposition products of the CF3SO2F/CO2 mixture at temperatures ranging from 1400 to 3200 K. In this study, decomposition products are categorized as primary or secondary based on their formation mechanisms. Primary products, such as CF4 and SO2, are directly formed from the initial breakdown of CF3SO2F. Secondary products, such as SO and CF2, result from subsequent reactions involving intermediate species. In the analysis of decomposition products, CO2 originating from the buffer gas was systematically excluded to ensure that the reported product yields exclusively reflect new species formed from the decomposition of CF3SO2F and its subsequent reactions. The decomposition of the CF3SO2F/CO2 mixture begins at 1400 K. At this temperature, the extent of decomposition is limited, and the dominant reaction pathway yields CF4 and SO2. As the temperature increases to 2200 K, the number of primary decomposition products (CF4 and SO2) increase (Fig. S7a), while their relative concentrations decrease due to further decomposition into secondary products such as SO and CF3 (Fig. 3a).

The relative concentration of CF3SO2F/CO2 final decomposition products a at 1400–3200 K, 12%CF3SO2F and 0.1 MPa, b at 2200 K, 12%CF3SO2F–20%CF3SO2F and 0.1 MPa, c at 2200 K, 12%CF3SO2F and 0.1–0.5 MPa. The relative concentration of CF3SO2F/N2 final decomposition products d at 1400–3200 K, 12%CF3SO2F and 0.1 MPa, e at 2200 K, 12%CF3SO2F–20%CF3SO2F and 0.1 MPa, f at 2200 K, 12%CF3SO2F and 0.1–0.5 MPa.

As the temperature increases to 3200 K, the number of chemical reactions and byproducts in the system significantly increases. At this stage, the mixture transformed into CF4, CF3, CF2, CF, CO, C, SO2F, SOF, SO2, SO, S, F, O2, and O. This is attributed to the further breakdown of large molecular groups into smaller molecules. For instance, CF4 could decompose into CF3, CF2, CF, and C, while SO2 may decompose into SO and S. Consequently, O atoms become the most abundant molecular fragments in the system, originating from the decomposition of both the main insulating gas CF3SO2F and the buffer gas CO2.

The formation of C and S at high temperatures indicates that solid precipitation of these elements should be considered in the design of equipment insulation. The radial distribution function (RDF) provides quantitative insight into the spatial correlation between particles within the system. Figure S8b and c present RDF analyses of the CF3SO2F/CO2 mixture at 2200 and 3200 K, respectively. A pronounced weakening of the characteristic peaks corresponding to S–F, C–O, and S–O bonds is observed compared to the initial decomposition stage at 1400 K (Fig. S8a). This reduction directly reflects the progressive decomposition of CF3SO2F, CO2, and SO2 molecular species as temperature increases.

Figure S7d presents the final decomposition products of the CF3SO2F/N2 mixture across a temperature range of 1400–3200 K. In addition to CF4 and SO2, the primary decomposition products consist of COF2, SOF2 at lower temperatures which are absent in the CF3SO2F/CO2 mixture, suggesting distinct decomposition pathways between the two systems. Both the quantity and relative concentration of these major primary products increase as the temperature rises to 2200 K (Fig. 3d). The reaction complexity intensifies with a further increase in temperature (3200 K). N ≡ N triple bond dissociates, yielding atomic N, meanwhile the primary products (CF4, SO2, COF2, and SOF2) further decompose into secondary species such as CF3, CF2, SO2F, SOF, SO, N, F, and O. Consequently, the quantity and relative concentration of primary products decline as secondary products become dominant. Unlike the CF3SO2F/CO2 mixture, negligible formation of oxygen and solid residues (C and S) is observed, further demonstrating the mechanistic differences between the two mixture systems. From a thermodynamic perspective, the extreme temperatures in the simulation substantially increase the entropy of atomic and radical species. Although molecular nitrogen possesses an exceptionally strong N ≡ N bond, its dissociation into monatomic nitrogen becomes feasible under these conditions. The resulting free atoms are stabilized by the high-entropy environment, making the atomic state more favorable than recombination into less stable molecular products like nitrogen monoxide. Consequently, the buffer gas acts primarily through physical influences such as modulating collision frequency and energy distribution rather than as a key reactant in the core decomposition mechanism.

A comparison of the bond length distributions at 1400 K (Fig. S8d) with those at higher temperatures (Fig. S8e and f) reveals a clear temperature-dependent dissociation behavior, characterized by a broadening of the distribution and the emergence of a peak at longer distances corresponding to bond rupture. The C–S and S–F bonds, mainly associated with CF3SO2F and SO2F, the C–F bond, related to both CF3SO2F and CF4, and the S–O bond, primarily from SO2F, all exhibit noticeable weakening. This indicates the progressive decomposition of these molecular species.

To further investigate the effect of CF3SO2F mixing ratio on the decomposition products of CF3SO2F/CO2 and CF3SO2F/N2 mixtures, the final products quantity and the relative concentration of CF3SO2F mixtures with different CF3SO2F mixing ratios at 2200 K were simulated as shown in Figures S7b, e, and 3b, e. The number of decomposition products decreases as the CF3SO2F mixing ratio in the system increases, consistent with the CF3SO2F decomposition evolution curves (vs. time) at different mixing ratios in Fig. 2c and f. Using CF3SO2F/CO2 mixtures as an example, the SO2 yield exhibits an inverse relationship with the CF3SO2F mixing ratio. Specifically, the 12%CF3SO2F/88%CO2 mixture generates 358 SO2 molecules after 1000 ps under 2200 K, whereas the 20%CF3SO2F/80%CO2 system produces only 280 SO2 molecules. Moreover, as the mixing ratio of CF3SO2F in the system increases (Fig. 3b), the relative concentration of CF4 and SO2 decreases, while the relative concentration of secondary products increases slightly. This trend aligns with the evolution of the final products quantity and relative concentration for mixture systems maintaining constant total number of molecules (Fig. S9), demonstrating the robustness of the results.

To examine the pressure dependence of CF3SO2F decomposition products, simulations were conducted for CF3SO2F/CO2 and CF3SO2F/N2 mixtures at 2200 K across a pressure range of 0.1–0.5 MPa. Figures S7c and 3c illustrate the evolution of final products and product relative concentration in the CF3SO2F/CO2 system. It can be seen that elevated pressure markedly accelerates reactions, promoting the transformation of primary products (CF4 and SO2) into smaller fragments, including SO, CF3, and monoatomic species (C, S, F, and O). At 0.5 MPa, CO2 undergoes substantial dissociation, yielding CO and O. The resulting [CO]/[CO2] ratio of 0.27 in our simulations shows remarkable agreement with the value of 0.26 reported in previous studies24. Furthermore, the O atom is the most abundant single product (1714 particles, 43% of the total). A parallel trend is observed for CF3SO2F/N2 (Figs. 3f, S7f), where high pressure similarly drives further fragmentation of primary products, though with comparatively lower decomposition yields.

Decomposition mechanism of CF3SO2F

To elucidate the thermal decomposition mechanisms of CF3SO2F/CO2 mixtures under varying conditions, we examined the temporal evolution of decomposition products. Both product yields and reaction rates showed strong positive correlations with temperature. Notably, the reaction profiles at 3200 K (Fig. 4a) were significantly steeper than those at 2200 K (Fig. S10), indicating an acceleration of the reaction rate at elevated temperatures. Notably, the variation of SO2 number reveals distinct reaction process: (1) an initial rapid accumulation phase (0–100 ps) characterized by a steep number increase, (2) an intermediate transition phase (100–500 ps) showing progressively slower accumulation, and (3) a final depletion phase (> 500 ps) exhibiting accelerated number decline. This behavior reflects rapid CF3SO2F decomposition initially (CF3SO2F → CF4 + SO2), producing SO2 faster than its decomposition. As CF3SO2F depletes, the formation rate of SO2 slows. However, the concurrent increase in the concentrations of SO2 molecules promotes its subsequent decomposition reactions, leading to its net consumption under these conditions. The presence of the product SO2F suggests that a high-temperature decomposition pathway involving direct C–S bond cleavage through intense molecular vibrations, yielding CF3 and SO2F for subsequent decomposition.

Time evolution of major decomposition products in CF3SO2F/CO2 mixtures under different conditions: a at 3200 K, 12%CF3SO2F and 0.1 MPa, b at 2200 K, 20%CF3SO2F and 0.1 MPa, c at 2200 K, 12%CF3SO2F and 0.5 MPa. Time evolution of major decomposition products in CF3SO2F/N2 mixtures under different conditions: d at 3200 K, 12%CF3SO2F and 0.1 MPa, e at 2200 K, 20%CF3SO2F and 0.1 MPa, f at 2200 K, 12%CF3SO2F and 0.5 MPa.

The CF3SO2F mixing ratio significantly influenced decomposition dynamics (Fig. 4b). Increasing the CF3SO2F mixing ratio in the mixture elevated the gas density (Table 1) and suppressed CF3SO2F decomposition, leading to a decrease in the yields of primary products (CF4 and SO2). Both reaction rate and product species exhibited a positive pressure dependence (Fig. 4c). At higher pressures, in addition to the primary products CF4 and SO2, small molecular fragments such as CF3, SO, F, O, S, and C are generated in significantly greater quantities, which suggests that higher pressures promote more extensive molecular dissociation of CF3SO2F.

The decomposition of CF3SO2F is the dominant factor governing the primary reaction pathways and product distribution in CF3SO2F/CO2 mixtures, as shown in Fig. 5a and Table S4. Trajectory simulations reveal that the net reaction CF3SO2F → CF4 + SO2 proceeds via two temperature-dependent pathways rather than a single concerted step. The primary product formation (CF4 + SO2) occurs through a concerted mechanism where C–S bond cleavage and fluorine transfer from SO2F to CF3 proceed simultaneously at temperatures above 1400 K as shown in Fig. S11. This concerted process, mediated by a transition state, directly yields CF4 and SO2, which is consistent with previous studies15. At temperatures exceeding 2200 K, direct C–S bond rupture becomes increasingly prevalent, producing CF3 and SO2F radicals. SO2F then decomposes primarily through S–F bond cleavage (yielding SO2 + F) with minor S–O cleavage (producing SOF + O). The resulting SOF decomposes further to SO and F. Primary products undergo progressive defluorination and deoxygenation, ultimately generating atomic species.

The CF3SO2F/N2 system demonstrates decomposition mechanisms analogous to CF3SO2F/CO2 while displaying distinct kinetic and product characteristics. At lower temperatures, CF3SO2F decomposition with N2 existing proceeds predominantly through two competing pathways: (1) direct formation of primary product of SO2 and CF4 (CF3SO2F → CF4 + SO2), and (2) direct formation of secondary product of COF2 and SOF2 (CF3SO2F → COF2 + SOF2) as shown in Fig. S12. Upon increasing the temperature to 3200 K, an additional pathway emerges involving direct C–S bond cleavage to yield CF3 and SO2F radicals (Fig. 4d), mirroring the behavior observed in CO2-based mixtures. Notably, in the N2 buffer gas, variations in the CF3SO2F mixing ratio show minimal impact on the fundamental reaction pathways, as evidenced by the consistent final product species across different mixture ratios (Figs. 4e and S12), even though the absolute product yields vary with the initial reactant amount. However, the system exhibits significantly reduced product diversity and slower reaction kinetics under elevated pressures (Fig. 4f), confirming the superior efficacy of N2 as a decomposition inhibitor compared to CO2. The distinct decomposition mechanism of CF3SO2F/N2 (Figs. 5b and S13) primarily differs through the inclusion of the COF2/SOF2 formation pathway. The absence of the COF2/SOF2 formation pathway in the CO2 system contributes to the observed differences in product profiles and decomposition rates between the two mixtures.

Experimental validation of CF3SO2F decomposition

To validate the simulation results, an overheating decomposition experiment was performed to investigate the thermal decomposition characteristics of 14%CF3SO2F/86%N2 gas mixtures. The experiments were systematically conducted under varying temperatures (150–250 °C in 50 °C increments), overheating duration (5h–15 h in 5 h increments), and gas pressures (0.2–0.4 MPa in 0.1 MPa increments), corresponding to the typical operational range of high voltage gas insulated equipment.

Following each test, the residual gas composition in the reaction chamber was sampled and analyzed. The GC-MS test result of the decomposition products of 14%CF3SO2F/86%N2 at 200 °C for 15 h is illustrated in Fig. S14. CF4 and SO2 were identified as the dominant decomposition products. Consequently, their yield variations under different conditions were systematically analyzed. As shown in Fig. 5e, the quantitative results demonstrate that CF4 and SO2 are the primary decomposition products with comparable concentrations, which aligns with the key predictions of the computational model. Furthermore, the observed consistent increase in their yields with rising temperature, extended reaction time, and elevated pressure firmly establishes the validity of the proposed decomposition mechanism. Furthermore, the radicals generated during decomposition exhibit a low tendency to recombine into CF3SO2F, further confirming the irreversible decomposition process.

Discussion

In summary, the decomposition mechanism of CF3SO2F/CO2 and CF3SO2F/N2 gas mixture at different temperatures, gas mixing ratios, and pressures was theoretically investigated and experimentally verified by deep learning potential training and molecular dynamics simulation. The results show that the decomposition of CF3SO2F/CO2 gas mixture starts at 1400 K under the time scale of 1000 ps, and the primary decomposition products are CF4 and SO2. When the temperature increases to 3200 K, CF3SO2F will decompose rapidly in the arc discharge channel, and the decomposition ratio of CF3SO2F reaches 0.94 within 1000 ps and decomposes to CF4, CF3, CF2, CF, CO, C, SO2F, SOF, SO2, SO, S, F, O2, O. At lower temperatures, the CF3SO2F molecule tends to cleave the C–S bond, with the F atom on SO2F transferring to CF3 during the bond breakage, ultimately forming CF4 and SO2. In contrast, at higher temperatures, increased molecular vibrations cause the C–S bond to break more directly, leading to the formation of CF3 and SO2F, which then undergo further decomposition. Furthermore, a higher initial concentration of CF3SO2F increases the absolute number of decomposition events. The accelerated accumulation of primary products such as CF4 and SO2 favors their own secondary reactions. The initial decomposition rate of CF3SO2F is significantly promoted by elevated system pressure due to the corresponding increase in molecular collision frequency. For engineering applications, this finding highlights the essential need for rigorous condition monitoring of electrical equipment to prevent significant CF3SO2F decomposition due to localized overheating, which would degrade its electrical insulation performance.

The primary decomposition pathways of CF3SO2F/N2 and CF3SO2F/CO2 mixtures are similar, except for an additional reaction in the latter system (CF3SO2F → COF2 + SOF2). The effects of temperature, gas composition, and pressure on the decomposition behavior of CF3SO2F in N2 closely resemble those observed in CO2. However, under high-pressure conditions, N2 acts as an inert buffer gas and more effectively suppresses the decomposition of CF3SO2F compared to CO2.

While CF3SO2F is proposed as an environmentally friendly alternative to SF6, the potential impact of its decomposition products should be rigorously assessed. Our simulations identify CF4 and COF2 as key decomposition species. It is critical to note that while the GWP of CF4 (7390) is significantly lower than that of SF6 (23500), it remains higher than that of carbon dioxide, with an atmospheric lifetime exceeding 50,000 years. Furthermore, COF2 is a highly toxic compound, posing potential safety hazards in the event of insulator failure and gas release. Our results, however, provide crucial insights for mitigating these risks. The formation of both CF4 and COF2 exhibits a strong dependence on temperature and the buffer gas environment. Specifically, using N2 as a buffer gas can suppress the formation of these harmful byproducts, potentially serving as an effective strategy to minimize environmental and safety risks. Therefore, the viability of CF3SO2F as an SF6 replacement hinges not only on its intrinsic properties but also on engineering controls that optimize operating conditions to limit the formation of deleterious by-products. This molecular-level understanding directly informs the development of safer, next-generation gas-insulated equipment aligned with global decarbonization goals.

In conclusion, this study identifies the major decomposition products and elucidates the primary reaction mechanisms of CF3SO2F under high-temperature and high-pressure conditions. The established computational framework provides a foundation that can inform future assessments of environmental impact and guide the development of safer CF3SO2F-based insulation technologies.

Methods

AIMD calculations setup

AIMD simulations were executed to construct the training dataset for machine learning. All calculations were carried out in the Vienna ab initio simulation packages (VASP)44,45. Ion-electron interactions were modeled with the Projector Augmented Wave (PAW) method46. Using the revised Perdew−Burke−Ernzerhof functional for describing electronic exchange and correlations, DFT calculations were executed employing the generalized gradient approximation method47. The plane-wave basis was applied with a cutoff energy of 520 eV. The convergence criteria for the electronic energy and structural relaxation were set to 10–6 eV and 0.01 eV/Å, respectively. AIMD simulations were performed in the canonical ensemble (NVT) with periodic boundary conditions and a time step of 0.5 fs to obtain configurations, energies, forces, and virials over a wide range of temperatures for the CF3SO2F gas mixture with three CF3SO2F molecules and six buffer gas molecules in the box. In the NVT simulations, the Nosé-Hoover thermostat was employed to maintain isothermal conditions at 30–3200 K for 20 ps. Molecular species were identified from the MD trajectories using a topology analysis algorithm based on interatomic distances and bond orders. This method allows for the dynamic tracking of bond formation and dissociation, enabling continuous identification of all chemical species throughout the simulation. The analysis script is available in the associated GitHub repository. Details of DP-GEN, DLP training, and MD setup were listed in the Supplementary Methods section of the Supporting Information.

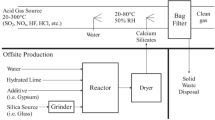

Thermal decomposition characteristics test platform

The experimental platform for investigating thermal decomposition characteristics comprises three main components: (1) a high-temperature test chamber, (2) a temperature control system, and (3) a DC power supply. The stainless steel test chamber (340 L grade, 10 L capacity) operates within a pressure range of 0–0.4 MPa. The thermal decomposition tests were conducted using a custom experimental platform, with the physical setup and schematic diagrams shown in Fig. 5c, d. The system pressure was monitored by a high-precision digital barometer connected to the chamber. A temperature control system, integrating electromagnetic relays with sensors and controllers, maintained precise thermal conditions. A DC power supply energized thermocouples to simulate the localized overheating faults typical in gas-insulated equipment. The gas composition and relative concentration of CF3SO2F mixed gas after the test were analyzed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) equipped with a GS-GASPRO column (60 m). The inlet temperature was maintained at 100 °C with a split ratio of 20:1. Helium carrier gas was used at a constant flow mode with a total flow of 57.0 mL/min, a column flow of 2.43 mL/min, and a linear velocity of 39.7 cm/s. The oven temperature program was as follows: held at 40 °C for 1 min, ramped to 120 °C at 7 °C/min, and finally held at 120 °C for 6 min. The MS ion source and transfer line temperatures were both set to 200 °C. Species identification was achieved by matching the acquired mass spectra and retention times against reference standards.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information. Source data are available as Supplementary Data 1.

Code availability

The DLP models are available on GitHub at https://github.com/LZYUCL/DLP_CF3SO2F and archived on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17731042.

References

Li, J. et al. Efficient continuous SF6/N2 separation using low-cost and robust metal-organic frameworks composites. Nat. Commun. 16, 632 (2025).

Rotering, P., Mück-Lichtenfeld, C. & Dielmann, F. Solvent-free photochemical decomposition of sulfur hexafluoride by phosphines: formation of difluorophosphoranes as versatile fluorination reagents. Green. Chem. 24, 8054–8061 (2022).

Xiao, S., Yang, Y., Li, Y., Lin, J. & Jin, Y. Decarbonizing the non-carbon: benefit-cost analysis of phasing out the most potent GHG in interconnected power grids. Environ. Sci. Technol. 59, 4255–4265 (2025).

An, M. et al. Sustained growth of sulfur hexafluoride emissions in China inferred from atmospheric observations. Nat. Commun. 15, 1997 (2024).

Ko, G., Go, W. & Seo, Y. Kinetic selectivity of SF6 during formation and dissociation of SF6+N2 hydrates and its significance in hydrate-based greenhouse gas separation. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 9, 14152–14160 (2021).

Mengesha, I. & Roy, D. Carbon pricing drives critical transition to green growth. Nat. Commun. 16, 1321 (2025).

Gao, W. et al. Mitigation of aging product generation in C4F7N-based SF6 alternatives: a holistic approach. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 12, 6467–6472 (2024).

Rabie, M. & Franck, C. M. Assessment of eco-friendly gases for electrical insulation to replace the most potent industrial greenhouse gas SF6. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 369–380 (2018).

Li, X., Zhao, H., Wu, J. & Jia, S. Analysis of the insulation characteristics of CF3I mixtures with CF4, CO2, N2, O2 and air. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 46, 345203 (2013).

Nechmi, H. E., Beroual, A., Girodet, A. & Vinson, P. Effective ionization coefficients and limiting field strength of fluoronitriles-CO2 mixtures. IEEE Trans. Dielect. Electrical Insulation 24, 886–892 (2017).

Li, X. et al. Calculation of thermodynamic properties and transport coefficients of C5F10O-CO2 thermal plasmas. J. Appl. Phys. 122, 143302 (2017).

Wang, Y., Huang, D., Liu, J., Zhang, Y. & Zeng, L. Alternative environmentally friendly insulating gases for SF6. Processes 7, 216 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Synthesis and dielectric properties of trifluoromethanesulfonyl fluoride: an alternative gas to SF6. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 58, 21913–21920 (2019).

Long, Y. et al. Electron swarms parameters in CF3SO2F as an alternative gas to SF6. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59, 11355–11358 (2020).

Zhang, M., Hou, H. & Wang, B. Mechanistic and kinetic investigations on decomposition of trifluoromethanesulfonyl fluoride in the presence of water vapor and electric field. J. Phys. Chem. A 127, 671–684 (2023).

Hu, S. et al. Dielectric properties of CF3SO2F/N2 and CF3SO2F/CO2 mixtures as a substitute to SF6. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59, 15796–15804 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. Decomposition mechanism of C5F10O: an environmentally friendly insulation medium. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 10127–10136 (2017).

Gao, W. et al. High-throughput compatibility screening of materials for SF6-alternative insulation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 13296–13306 (2024).

Suehiro, J., Zhou, G. & Hara, M. Detection of partial discharge in SF6 gas using a carbon nanotube-based gas sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 105, 164–169 (2005).

Ke, X. et al. Calculation of particle composition and physical property parameters of arc plasma particles of CF3SO2F and its gas mixtures. Trans. China Electrotech. Soc. 39, 6145–6161 (2024).

Wang, A. et al. Arc plasma transport parameter calculation and related influencing factor analysis for CF3SO2F gas mixture as new eco-friendly insulating medium. High. Volt. Eng. 50, 4261–4271 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Critical review of thermal decomposition of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances: mechanisms and implications for thermal treatment processes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 5355–5370 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Insight into the decomposition mechanism of C6F12O-CO2 gas mixture. Chem. Eng. J. 360, 929–940 (2019).

Zhang, X. et al. Decomposition mechanism of the C5-PFK/CO2 gas mixture as an alternative gas for SF6. Chem. Eng. J. 336, 38–46 (2018).

Yang, M., Raucci, U. & Parrinello, M. Reactant-induced dynamics of lithium imide surfaces during the ammonia decomposition process. Nat. Catal. 6, 829–836 (2023).

Car, R. & Parrinello, M. Unified approach for molecular dynamics and density-functional theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 55, 2471–2474 (1985).

Wang, H., Zhang, L., Han, J. & Weinan, E. Deepmd-kit: a deep learning package for many-body potential energy representation and molecular dynamics. Comput. Phys. Commun. 228, 178–184 (2018).

Vanommeslaeghe, K. et al. CHARMM general force field: a force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all-atom additive biological force fields. J. Comput. Chem. 31, 671–690 (2010).

Chenoweth, K., van Duin, A. C. T. & Goddard, W. A. ReaxFF reactive force field for molecular dynamics simulations of hydrocarbon oxidation. J. Phys. Chem. A 112, 1040–1053 (2008).

Cao, Y., Liu, C., Zhang, H., Xu, X. & Li, Q. Thermal decomposition of HFO-1234yf through ReaxFF molecular dynamics simulation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 126, 330–338 (2017).

Liu, H., Wang, J., Li, Q. & Haddad, A. M. Development of ReaxFFSFOH force field for SF6-H2O/O2 hybrid system based on synergetic optimization by CMA-ES and MC methodology. ChemistrySelect 6, 4622–4632 (2021).

Chmiela, S. et al. Machine learning of accurate energy-conserving molecular force fields. Sci. Adv. 3, e1603015 (2017).

Schütt, K. T., Arbabzadah, F., Chmiela, S., Müller, K. R. & Tkatchenko, A. Quantum-chemical insights from deep tensor neural networks. Nat. Commun. 8, 13890 (2017).

Smith, J. S., Isayev, O. & Roitberg, A. E. ANI-1: an extensible neural network potential with DFT accuracy at force field computational cost. Chem. Sci. 8, 3192–3203 (2017).

Zhang, Y. et al. DP-GEN: a concurrent learning platform for the generation of reliable deep learning based potential energy models. Comput. Phys. Commun. 253, 107206 (2020).

Feng, Y. & Wang, C. Surface confinement of finite-size water droplets for SO3 hydrolysis reaction revealed by molecular dynamics simulations based on a machine learning force field. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 10631–10640 (2023).

Yang, M., Bonati, L., Polino, D. & Parrinello, M. Using metadynamics to build neural network potentials for reactive events: the case of urea decomposition in water. Catal. Today 387, 143–149 (2022).

Zhang, L. et al. Deep potential molecular dynamics: a scalable model with the accuracy of quantum mechanics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 143001 (2018).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS - a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 271, 108171 (2022).

Zheng, Y., Hao, D., Liu, W., Ren, S. & Zhou, W. Ionization and attachment properties of gas mixtures with CF3SO2F plus air/CO2/N2. IEEE Trans. Dielect. El. In. 1–1 https://doi.org/10.1109/TDEI.2025.3566365 (2025).

Liu, W. et al. Experimental study of compatibility between the eco-friendly insulation mixed gas CF3SO2F/N2 and EPDM and CR materials. ACS Omega 9, 7958–7966 (2024).

Hermann, J., DiStasio, R. A. Jr & Tkatchenko, A. First-principles models for van der waals interactions in molecules and materials: concepts, theory, and applications. Chem. Rev. 117, 4714–4758 (2017).

Sasihithlu, K. & Scholes, G. D. Vibrational dipole–dipole coupling and long-range forces between macromolecules. J. Phys. Chem. B 128, 1205–1208 (2024).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comp. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFB2401400).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Anyang Wang, Zeyuan Li, and Shubo Ren contributed equally to this work. Anyang Wang: writing—original draft, investigation, visualization. Zeyuan Li: validation, visualization, software. Shubo Ren: methodology, investigation, validation. Xue Ke: investigation, visualization. Xuhao Wan: validation, visualization. Rong Han: investigation. Xianglian Yan: resources, Wen Wang: investigation. Yu Zheng: resources, methodology, supervision. Yuzheng Guo: writing—review and editing, supervision. Jun Wang: writing—review and editing, supervision, funding acquisition, conceptualization.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Thuat T. Trinh and Felix Schmalz for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, A., Li, Z., Ren, S. et al. Probing the thermal decomposition mechanism of CF3SO2F by deep learning molecular dynamics. Commun Chem 9, 40 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01847-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01847-x