Abstract

Helices are present in the most important biomolecules (i.e., RNA, DNA). Helices are formed in biology and the laboratory using subunits with information encoded based on molecular recognition. The production of abiotic helical structures is an ongoing goal in synthetic and materials chemistry and has involved the development of organic and metal-organic materials that rely on complementarity of noncovalent forces (e.g. hydrogen bonds, coordination bonds) for helix formation. Herein, we describe a series of supramolecular isomers of three hydrogen-bonded organic cocrystals involving components that self-assemble and show progression at the structural level from a zig-zag chain to a double helix and to a quadruple helix. The isomers constitute a form of trimorphism involving a binary cocrystal system and we show that the polymeric structures can be interconverted through solvent-mediated phase transformations. We demonstrate the cocrystal involving the double helix to possess components that undergo an intermolecular [2 + 2] photodimerization in the crystalline state.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Of the common architectures in biological systems, helices (e.g., RNA, DNA) are of fundamental importance (e.g., relay chemical information)1,2. Ribonucleic acid (RNA) and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) are single- and double-stranded helices, respectively, with the components assembling through hydrogen bonds. Mathematically, the three-dimensional (3D) structure of a helix is derived from the 2D structure of a zig-zag3. The structures of zig-zags and helices are, more generally, examples of skew apeirogons, which are part of a class of infinite 2-polytopes with vertices that are not all colinear (Scheme 1). Progression of the structure of a zig-zag to a helix requires addition of an axis of rotation wherein the vertices are located to lie on the surface of a cylinder3.

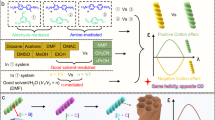

In this report, we describe a binary cocrystal with components that self-assemble to progress at the structural level from a zig-zag to a double helix and to a quadruple helix (Scheme 2). The formation of the 1D structures, which are related as supramolecular isomers4, is manifested as three crystal polymorphs (Forms I-III), wherein the components of each trimorph self-assemble through hydrogen bonds. We show the generation of the polymorphs to be influenced by water, with solutions of higher water content promoting the formation of the quadruple helix. We also show mechanochemistry and heat to promote the formation of the double helix and quadruple helix, respectively. While the development of self-assembled zig-zags and helices being ongoing challenges in synthetic chemistry (e.g., catalysis) and materials sciences (e.g., optoelectronics)5,6, we are unaware of a case wherein the components of a purely organic multi-component system, such as a cocrystal, self-assemble to generate zig-zag and helical structures. Related solids composed of metal-organic components, which are sustained by coordination bonds, are reported to form zig-zags and helices in limited cases6.

Results and Discussion

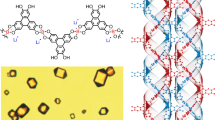

The binary cocrystal (f-cat)·(bpe) (where: f-cat = 3-fluorocatechol; bpe = trans-1,2-bis(4-pyridyl)ethylene) is trimorphic7. Each trimorph is obtained through solution-mediated phase transformation8. Specifically, each form is generated from a slightly opened screw-top sample vial involving an equimolar solution of f-cat (42 mg) and bpe (60 mg) in methanol/water (4 mL, 1:1). Form I (yellow plates) is generated in a period of 5 min upon precipitation from a resulting orange solution. Form II (orange-green dichroic prisms) is generated in the same solvent system after a period of 10 h from a green solution. Prolonged suspension of Form II for 20 h results in the generation of Form III (blue needles) from a blue solution.

As chemical building blocks, f-cat and bpe can function as double hydrogen-bond donors and acceptors, respectively. The diol f-cat can furthermore adopt one of nine likely conformations to support a self-assembly process with bpe (Scheme 3).

Self-assembly of trimorphs

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) analysis reveals the components of Form I to crystallize in the chiral orthorhombic space group P212121 with two molecules each of f-cat and bpe in the asymmetric unit (Fig. 1). The components form a 1D zig-zag chain along a 21-screw with the f-cat molecules adopting a gauche-syn conformation (Fig. 1a,b) (Table 1). The chains involve two unique (f-cat)·(bpe) units within the zig-zag chain based on a repeat distance slightly under 2.0 nm (19.6 Å). The components are sustained by O-H···N hydrogen bonds [O···N distances (Å): O(1)···N(1) 2.701(9)/O(3)···N(2) 2.698(9) and O(4)···N(3) 2.762(9)/O(2)···N(4) 2.823(10)]. The chains interdigitate to exhibit a tongue-in-groove fit within the crystallographic bc-plane (Fig. 1c).

In principle, the hydrogen bonding of the zig-zag chain can be manifested as two supramolecular isomers7 wherein the F-atoms point either in the same (parallel) or opposite (antiparallel) directions within an individual chain. For Form I, the f-cat components point in opposite directions, interacting with two crystallographically distinct bpe molecules. The shortest hydrogen-bond distances involve the more acidic hydroxyl group adjacent to the F-atom, with the components of the chain twisted (twist angles: 6.7°, 25.6°, 13.9°, 12.3°) about each hydrogen bond.

In contrast to Form I, the components of Form II self-assemble to form a double helix (Fig. 2). The components crystallize in the monoclinic centrosymmetric space group C2/c with one molecule each of f-cat and bpe in the asymmetric unit. As with Form I, the diol and bipyridine assemble via O-H···N hydrogen bonds [O···N distances (Å): O(2)···N(1) 2.7623(2), O(1)···N(2) 2.7067(1)]. The self-assembly generates chains exhibit a longer overall repeat distance on the order of 3.0 nm (31.4 Å) compared to Form I (Fig. 2a, b), with f-cat adopting a gauche-anti conformation (hydroxyl group twist -130°).

The F-atoms of Form II, in contrast to Form I, point in the same direction (Fig. 2a) along each helix chain, with the helixes running along a crystallographic b-glide plane in a head-to-head arrangement. The components of each strand are more twisted (twist angles: 80.3° and 73.9°) about each hydrogen bond compared to Form I. Offset infinite and face-to-face π-π stacking of bpe [centroid···centroid (Å): 3.867(5)] results in adjacent double helices related by a crystallographic center of inversion (Fig. 2c). The close packing is also mediated by edge-to-face π-interactions of the pyridyl groups and f-cat.

Whereas the components of Form I and Form II form a zig-zag and double helix, respectively, the components of Form III self-assemble to form a quadruple helix. The components crystallize in the trigonal space group R \(\bar{3}\) with one molecule of f-cat and bpe in the asymmetric unit. As with Form I and II, the components generate 1D chains sustained by O-H···N hydrogen bonds [O···N distances (Å): O(1)···N(1) 2.692(1), O(2)···N(2) 2.708(1)] (Fig. 3). The chains participate, in contrast to Form II, as a quadruple helix along the crystallographic c-axis wherein the f-cat molecules adopt an anti-anti conformation. As with Form II, the F-atoms of Form III point in the same direction within a chain (Fig. 3a), with the helices oriented in a head-to-head arrangement. The helical chains tessellate within the ab-plane with packing based on triangles with neighboring helices being of opposite handedness. The F-atoms of the helices converge with F···F interactions at a core separated by 3.820(2) Å. Each helical chain exhibits an overall repeat distance larger than Forms I and II, being on the order of 5.0 nm (48.2 Å) and with the components also twisted (36.8° and 13.3°) from coplanarity.

Role of solvent

To further elucidate the role of solvent in supporting the formation of the polymorphs, we have determined that when equimolar f-cat and bpe are dissolved in either methanol or water, the zig-zag Form I forms as a precipitate as single crystals and a powder. Prolonged suspension for a period of either 2 or 4 h results in a phase transformation to generate either the double helix Form II or quadruple helix Form III, respectively. Form II predominated in mixed solutions with at least 30% methanol (v:v) while Form III predominated in more aqueous solutions (Scheme 4). The dependence of Form III on the high-water content likely can be ascribed to a hydrophobic packing9 effect involving the F-atoms that converge between the helices in the solid (Fig. 3d). A similar phenomenon has been described in materials composed of fluorinated proteins10.

Form II was also determined to form by neat grinding, as well as liquid assisted grinding (LAG) with methanol11. When powder samples of either Form I or Form III were subjected to the grinding conditions, each solid converted to Form II. Grinding of a sample of Form II alone also did not result in a change in phase. A Hirshfeld analysis of each trimorph revealed C···C contacts to constitute the highest percentage in Form II (9.4%), which is consistent with the presence of the face-to-face π-stacks. Face-to-face stacking is significant in stabilizing the structures of proteins and other biomolecules9. The stability of Form II can be attributed to the presence of the face-to-face π-stacks. The prevalence of the stacking is corroborated with energy framework calculations at the B3LYP/6-311 G(d,p) level using CrystalExplorer where the packing of Form II involves dominant dispersion energies (Supplementary Fig. 5). We note that heating of a separate sample of Form II at 130 °C for 2 h resulted in a phase transformation to Form III (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Photoreactivity of π-stacks of double helix

The proximity of the C=C bonds (3.675(4) Å) within the stacks and between the double helices of Form II renders the solid photoactive12,13,14. Specifically, when Form II was subjected to UV-radiation (72 h), the C=C bonds of bpe underwent an intermolecular [2 + 2] photodimerization to afford rctt-tetrakis(4-pyridyl)cyclobutane (tpcb) stereospecifically and in near quantitative yield. The generation of tpcb was evidenced by the complete disappearance of the alkene peak at 7.65 ppm and appearance of the cyclobutane peak at 4.70 ppm on the 1H NMR spectrum (Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8).

When the resulting photoreacted solid was dissolved in ethanol, single crystals as colorless plates of composition 2(f-cat)·(tpcb) formed. The asymmetric unit consists of one full molecule of tpcb and two molecules of f-cat, which crystallize in the monoclinic space group P21/c (Fig. 4). The components generate a O-H···N hydrogen-bonded corrugated network within the crystallography ab-plane [O···N distances (Å): O(1)···N(3) 2.682(2), O(2)···N(4) 2.694(2), O(3 A)···N(2) 2.661(2), O(4 A)···N(1) 2.592(2)] (Fig. 4a). The cyclobutanes of 2(f-cat)·(tpcb) are bridged by f-cat in anti-gauche (-175.75°) and gauche-anti conformations (177.7°) (Fig. 4b, c). The network can be simplified as a sql topology (point symbol 44.62) with the nodes as the centroids of the cyclobutane rings of tpcb (Fig. 4d)15. Thus, the photodimerization supports a change from a double helix to a sql network. While [2 + 2] photodimerizations in the solid state have been reported between 3D network structures (i.e., diamondoid networks)16, we are unaware of an example wherein an intermolecular photodimerization occurs between helical structures.

Conclusions

In this report, we have described trimorphism involving a hydrogen-bonded binary cocrystal. With f-cat being unsymmetrical and conformationally flexible, supramolecular isomerism was expressed in Form I as a planar zig-zag and Form II and Form III as double and quadruple helices, respectively. Components of the double helices of Form II were also demonstrated to be photoactive in the solid state. We are now studying the scope of the polymorphism and extension to additional unsymmetrical coformers with the idea of determining the breadth of self-assembled frameworks that existence within the polymorphism domain. With the structures of zig-zags also being present in biochemistry (e.g., Z-DNA), it is intriguing to consider whether zig-zags of biological origin have a capacity to spontaneously evolve and self-assemble into helical structures.

Materials and Methods

Materials

3-fluorocatechol, acetonitrile, chloroform, ethyl acetate, and methanol were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals. Trans-1,2-bis(4-pyridyl)ethylene was purchased from TCI Chemicals. All chemicals were used as received and without further purification.

Photodimerization experiments

A powder sample of Form II was subjected to UV-radiation (up to 72 h) using an ACE photocabinet equipped with an ACE quartz, 450 W, broadband, medium pressure, Hg-vapor lamp.

Nuclear magnetic resonance

Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (¹H-NMR) spectra were measured on a Bruker AVANCE 400 MHz spectrometer using DMSO-d₆ as the solvent.

Mechanochemistry

Liquid-assisted grinding (LAG) experiments were conducted in an FTS-1000 shaker mill using 5.0 mL PTFE jars and two stainless-steel balls (5.0 mm diameter). The reactions were performed at 20 Hz with 50 µL of solvent.

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) data were collected on a Bruker Nonius Kappa CCD single-crystal X-ray diffractometer using MoKα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å). Reflections were harvested from ϕ and ω scans with an intensity threshold of I > 2σ (I). Data collection, reduction, and cell refinement were accomplished using the Bruker Apex2 software suite. Using Olex217, structure solution and refinement were accomplished using SHELXT18 and SHELXL19, respectively. Non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. Hydrogen atoms of carbon atoms were refined in geometrically constrained positions.

Powder X-ray diffraction

Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) data were collected on a Bruker D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer using CuKα1 radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) in the range 5–45° (scan type: coupled Two Theta/Theta; scan mode: continuous PSD fast; step size: 0.019°) (40 kV and 30 mA).

Computational analysis

CrystalExplorer 21.5 program20 was utilized to evaluate the interaction energies at B3LYP/6311 G(d,p) level. Interaction energies (Eele, Emol, Edis, Erep, Etot) of Forms I-III are shown in Supplementary Table 4 and energy frameworks are illustrated in Supplementary Figs. 4–6.

Data availability

The data supporting this study is presented in the article and its supplementary information. The X-ray crystallographic data for structures reported in this Article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers CCDC 2431180, 2431183, 2431185, and 2431187. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

References

Banfalvi, G. Structural organization of DNA. Biochem. Educ. 14, 50–59 (1986).

Ghosh, A. & Bansal, M. A glossary of DNA structures from A to Z. Acta Crystallogr. D. 59, 620–626 (2003).

Coexeter, H. S. M. Regular Complex Polytopes (London: Cambridge University Press, 1974).

Hennigar, T. L., MacQuarrie, D. C., Losier, P., Rogers, R. D. & Zaworotko, M. J. Supramolecular isomerism in coordination polymers: conformational freedom of ligands in [Co(NO3)2(1,2-bis(4-pyridyl)ethane)1.5]n. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 36, 972–973 (1997).

Yashima, E. et al. Supramolecular helical systems: helical assemblies of small molecules, foldamers, and polymers with chiral amplification and their functions. Chem. Rev. 116, 13752–13990 (2016).

Zhang, J.-P., Huang, X.-C. & Chen, X.-M. Supramolecular isomerism in coordination polymers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 2385–2396 (2009).

Ortiz-de León, C. & MacGillivray, L. R. Clues from cocrystals: a ternary solid, polymorphism, and rare supramolecular isomerism involving resveratrol and 5-fluorouracil. Chem. Commun. 57, 3809–3811 (2021).

Yu, J., Henry, R. F. & Zhang, G. G. Z. Cocrystal screening in minutes by solution-mediated phase transformation (SMPT): preparation and characterization of ketoconazole cocrystals with nine aliphatic dicarboxylic acids. J. Pharm. Sci. 114, 592–598 (2025).

Dalvi, V. H. & Rossky, P. J. Molecular origins of fluorocarbon hydrophobicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 13603–136067 (2010).

Marsh, E. N. G. Fluorinated proteins: from design and synthesis to structure and Stability. Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 2878–2886 (2014).

Karki, S., Friscic, T., Jones, W. D. & Motherwell, S. Screening for Pharmaceutical Cocrystal Hydrates via Neat and Liquid-Assisted Grinding. Mol. Pharm. 4, 347–354 (2007).

MacGillivray, L. R. et al. Supramolecular control of reactivity in the solid state: from templates to ladderanes to metal-organic frameworks. Acc. Chem. Res. 41, 280–291 (2008).

Hutchins, K. M., Sumrak, J. C., Swenson, D. C. & MacGillivray, L. R. Head-to-tail photodimerization of a thiophene in a co-crystal and a rare adipic acid dimer in the presence of a heterosynthon. CrystEngComm 16, 5762–5764 (2014).

Paul, A. K., Karthik, R. & Natarajan, S. Synthesis, structure, photochemical [2 + 2] cycloaddition, transformation, and photocatalytic studies in a family of inorganic organic hybrid cadmium thiosulfate compounds. Cryst. Growth Des. 11, 5741–5749 (2011).

Mitina, T. G. & Blatov, V. A. Topology of 2-periodic coordination networks: toward expert systems in crystal design. Cryst. Growth Des. 13, 1655–1664 (2013).

Park, I.-H. et al. Metal–organic organopolymeric hybrid framework by reversible [2+2] cycloaddition reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 414–419 (2014).

Dolomanov, O. V. et al. OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 42, 339–341 (2009).

Sheldrick, G. M. SHELXT: Integrated space-group and crystal structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. Found. Adv. 71, 3–8 (2015).

Sheldrick, G. M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. C. Struct. Chem. 71, 3–8 (2015).

Spackman, P. R. et al. CrystalExplorer: A program for Hirshfeld surface analysis, visualization and quantitative analysis of molecular crystals. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 54, 1006–1011 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The work received financial support from the National Science Foundation (L. R. M. DMR-DMR-2221086, CHE-1828117), the Canada Excellence Research Chair Program (L. R. M.), and the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (C. O. -de L., graduate fellowship).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.J.E.D. designed the cocrystallization and carried out cocrystallization experiments, analyzed the results, and wrote the manuscript. C.O.-de L. carried out cocrystallization experiments, performed the photodimerizations, performed calculations, analyzed the results, and wrote the manuscript. M.G.V.-R. carried out cocrystallization experiments, performed calculations, and analyzed the results. D.C.S. collected the SCXRD data. L.R.M. supervised the research project and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks Michael Ward and the other, anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Duncan, A.J.E., Ortiz-de León, C., Vasquez-Ríos, M.G. et al. Trimorphism of a binary cocrystal system with hydrogen-bonded zig-zag, double helix and quadruple helix structures. Commun Chem 9, 49 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01856-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01856-w