Abstract

Increasing nitrate (NO3−) concentration in water bodies due to anthropogenic activities has become a leading environmental challenge of the 21st century. Electrochemical nitrate reduction reaction (eNO3RR) offers a sustainable solution by simultaneously removing nitrates and producing ammonia, a valuable feedstock. However, eNO3RR possesses significant challenges, such as efficiency, competing reactions, product selectivity, catalyst stability, etc. This review article highlights the importance of eNO3RR, its mechanistic pathway, in-situ/operando techniques to understand the mechanistic pathway, reactor design, analytical challenges in product estimation, and catalyst designing strategies. This work uniquely integrates in-situ studies, mechanistic insights, and design principles to establish clear structure-activity correlations for advancing eNO3RR catalysts. We conclude with current challenges and prospects to guide future research toward efficient and selective catalysts for eNO3RR-driven ammonia production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The widespread use of fertilizers in agricultural activities and industrial release of untreated wastages and wastewaters from urban areas have resulted in nitrate (NO3−) pollution in water bodies, disrupting the N2 cycle and causing several health hazards1. Unlike other contaminants, NO3− removal from water bodies is difficult due to its high stability and solubility2. Current technologies such as reverse osmosis, ion-exchange, electrodialysis, biological denitrification using anaerobic bacteria, etc., involve substantial capital expenditure and are only effective when the NO3− concentration is significant2,3. The electrochemical nitrate reduction to ammonia (ENRA) is one of the most promising ways to address this, as it is cost-effective, environmentally benign, and energy efficient3. Moreover, in addition to removing NO3− from the water bodies, it also produces NH3, a value-added chemical feedstock4,5. Thus, ENRA represents a dual-function technology that directly links environmental remediation with sustainable energy and fertilizer production, supporting circular nitrogen management and decarbonization efforts.

Ammonia is an essential raw material for various industries such as fertiliser, medicine, leather, paper, food, etc. Additionally, NH3 is also being used as a hydrogen carrier or as a direct energy source, such as in fuel cells for sustainable energy applications6,7. The current industrial NH3 demand is still being filled by the century-old Haber–Bosch (H-B) process. But, the H-B process, where the stable N≡N bond (dissociation energy = 941 kJ mol−1) is broken in the presence of H2, requires a high temperature (400–600 °C) and high pressure (200–300 atm), and emits a large amount of CO28. This high-carbon and energy-intensive process is responsible for more than 1% of global energy consumption and emits 1.5 tons of CO2 per ton of production of NH38. To date, no cutting-edge technology has yet replaced the H-B process to meet the escalating demand for ammonia production. Electrochemical production of NH3 has recently been accepted as an alternative to the H-B process. In this regard, scientists have focused heavily on two processes, namely, electrochemical N2 reduction reaction (eNRR) and electrochemical nitrate reduction reaction (eNO3RR)9. Among these two, the eNO3RR has emerged as a more sustainable alternative as it not only offers a low-cost and environment friendly route to ammonia production but also provides the opportunity to mitigate harmful nitrate pollution in water10,11. Moreover, the ENRA possesses certain advantages over eNRR, such as high solubility of NO3− in electrolyte as compared to N2, and a thermodynamically favourable reaction as ENRA involves breaking of N=O bond (bond dissociation energy of 204 kJ mol−1) instead of N≡N bond12,13. Therefore, the ENRA has the potential to not only serve as an environmental remediation against nitrate pollution but also reduce the carbon footprint by replacing the energy-intensive H-B process, aligning with global carbon-neutral and nitrogen-cycle restoration goals. Despite the advantages, the ENRA suffers from poor selectivity, energy efficiency, and, most importantly, much lower yield as compared to the present industrial processes14,15. The eNO3RR often involves multi-electron, multi-proton pathways with numerous intermediates, requiring precisely engineered catalysts, electrolyte environments, and cell configurations16,17. Moreover, eNO3RR still faces several system-level bottlenecks beyond catalyst design, including sustainable nitrate sourcing, electrolyte engineering, mass-transfer limitations under high current densities, etc18. These aspects are increasingly recognised as critical to achieving high conversion rates and practical deployment of ENRA systems.

This review article critically surveys the recent progress of ENRA. A detailed discussion is provided on the mechanistic pathway followed by eNO3RR. Moreover, we also discussed various in-situ/operando techniques that are crucial to evaluate the mechanistic pathway of eNO3RR catalysts to provide a guideline for future mechanistic studies. We also highlight various evaluation metrics, product detection methods, reactor designs, and cell configurations to provide readers with a comprehensive guide to ENRA. An overview of the theoretical and experimental advances in electrocatalyst development for sustainable ENRA has also been provided. We concluded the article, highlighting the present challenges and our perspectives to provide a clear roadmap for future research direction in electrochemical nitrate conversion and sustainable ammonia synthesis.

Reaction mechanism of electrocatalytic nitrate reduction

The eNO3RR involves two different thermodynamically favoured pathways, namely, (a) Formation of NH3 accompanied by nine protons and eight electrons transfer (Eq. 1), and (b) N2 formation accompanied by twelve protons and ten electrons (Eq. 2).

NH3 formation reaction:

N2 formation reaction:

The first and foremost step in eNO3RR is the activation of the NO3− group. This is achieved by the adsorption of NO3− over the catalyst surface.

(where *NO3− refers to adsorbed NO3− on catalyst surface and * referring to an active catalytic site).

Based on the number of oxygen atoms of the NO3− anion interacting with the active site, Wang et al.19 proposed two possible patterns, namely 1-O, where only one O atom binds with the active site, and 2-O, where two oxygen atoms bind with the active site (Fig. 1 inset). The 2-O pattern is favoured more owing to the higher negative adsorption energy than the 1-O pattern. The negative value of the adsorption energy on the catalyst surface is essential as it determines whether the subsequent steps can follow up spontaneously. This activity performance criterion can be expressed in terms of limiting potential (UL = −Gmax/e), where Gmax is the highest value of free energy change in all fundamental steps. When the limiting potential is plotted against the \({\Delta {{\rm{G}}}}_{{{NO}}_{3}^{-}}^{\ast }\), it gives the volcano diagram, which rationalise that neither too strong nor too weak adsorption of NO3− results in a better catalyst performance (Sabatier Principle)16,19.

Detailed mechanistic pathways of eNO3RR including O-end, O-side, N-end, N-side. The inset at the top left shows the two different patterns of NO3− adsorption on the active site of the catalyst. Adapted with permission from ref. 19. © Elsevier.

Adsorption of NO3− is followed by its reduction into a key intermediate species NO2−, and this is achieved by the following three sequential sub-steps

Summing up the steps (4), (5), and (6), the whole electrochemical reduction *NO3− to *NO2− is accompanied by the transfer of two electron-proton pairs and can be written as,

Product(s) of eNO3RR depend on the fate of *NO2−. *NO2− may further be reduced to *NO, involving the following elementary steps,

Based on the geometric factor of NO adsorption, subsequent processes have been put into three classes, which are the O-end pathway, N-end pathway, and NO-side pathway, as demonstrated in Fig. 1. The O-end pathway to yield NH3 involves the following three consecutive steps.

The N-end pathway yielding NH3 involves the following five elementary steps:

The third pathway is based on the NO-side adsorption, where the site preference (N or O atom of NO) towards protonation determines which proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) process (N-end or O-end) shall be followed towards NH3 formation. If the N-atom is protonated, the resulting *ONH reduces to *O, and further reaction follows a similar O-end pathway. On the contrary, protonation of the O-atom results in *NOH, and the further reaction may follow either N-end pathway (Fig. 2) or may undergo further protonation, ultimately yielding NH320,21.

a Proposed eNO3RR mechanisms and pathways. Adapted with permission from ref. 23. © Wiley b DFT-calculated minimum energy pathway for the conversion of NO2− to NH3 and NO2− at 0 V versus RHE at pH = 14. White, blue, red, brown, and teal spheres correspond to H, N, O, Cu, and Ru atoms, respectively. Adapted with permission from ref. 24. © Springer Nature.

It’s noteworthy to mention that N-N coupling (Fig. 1 bottom right) shall be prohibited for selective NH3 formation. In this regard, the *NO protonation step yielding *NOH or *ONH is crucial22.

Furthermore, *NO intermediate derived from *NO2− may compromise the efficiency of eNO3RR into ammonia by yielding either N2 following Vooys–Koper mechanism or Duca–Feliu–Koper mechanism (Fig. 2a). The *NO2− may dissociate into the medium giving NO2 or HNO2 through Vetter mechanism or Schmid mechanism, respectively. Though route IIIʹ (Fig. 2a) may govern the selectivity of eNO3RR, however, this route is less common and mostly favours in a strongly acidic condition along with a high NO3− concentration (1–4 M HNO3), making it less frequently reported22,23.

An in-depth understanding of the reaction pathways from NO3− to NH3 is essential for the rational design of effective electrocatalysts. Based on studies of eNO3RR using Ru-dispersed Cu nanowires (Ru–CuNW) catalyst, Chen et al.24 identified a favourable reaction pathway under alkaline conditions through density functional theory (DFT) calculations. This pathway follows the sequence: NO3− → *NO3− → *NO2 → *NO → *N → *NH → *NH2 → *NH3 → NH3 (g) (Fig. 2b), considering both thermodynamics and kinetics. The overall conversion of NO3− to NH3 involves sequential deoxygenation and hydrogenation steps, processes commonly observed on various metal surfaces. During eNO3RR, however, the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER: 2H⁺ + 2e⁻ → H2, E⁰ = 0 V) is an inevitable competing side reaction due to the comparable thermodynamic potentials of HER and eNO3RR, especially under more negative applied potentials24. To improve selectivity toward eNO3RR, strategies have focused on suppressing HER through catalyst design. Nevertheless, it’s important to recognise that adsorbed hydrogen (*H) is crucial for hydrogenation steps in NH3 formation. Thus, achieving a fine balance between *H generation and consumption is key. Although the detailed mechanisms vary with the choice of electrocatalyst, intermediates such as adsorbed nitric oxide (*NO) and nitrite ion (NO2⁻) play a central role in determining selectivity. As illustrated in Fig. 2a, *NO acts as a key branching point that can direct the reaction toward various products, including N2O, N2, NH2OH, or NH3. Therefore, a catalyst’s selectivity in eNO3RR is closely tied to its binding affinity with *NO.

In the eNO3RR process, the rate-determining step is generally the initial reduction of NO3− to NO2−25. A deeper understanding of this step is critical for developing catalysts that enhance charge transfer kinetics, lower energy input, and reduce operational costs. This reduction step typically requires an overpotential, which proceeds at potentials lower than the thermodynamic standard. The sluggish kinetics are largely due to the high energy level of the nitrate’s lowest unoccupied molecular π* orbital (LUMO π*), which hinders efficient charge transfer25. Nevertheless, metals such as Ru, Cu, Fe, Ni, Co, and Ag possess d-orbital energy levels that align well with nitrate’s LUMO π*. Their unfilled d-orbitals facilitate more effective electron transfer, enhancing the electrochemical reduction of NO3−26.

To summarise, an ideal catalyst for eNO3RR into NH3 must have an optimal NO3− adsorption energy and must facilitate the rapid reduction of * NO3− into NO2−, followed by *NO formation with a favourable adsorption configuration on the catalyst surface. Afterwards, sequential PCET steps must ensure the inhibition of the N-N coupling reaction and other competitive reactions to achieve a higher NH3 selectivity.

It is imperative that the identification of reaction intermediates is important to determine the exact mechanistic pathway, which is essential to design the next generation of catalysts. A detailed mechanistic understanding demands direct observation of transient intermediates and dynamic surface transformations under realistic reaction conditions. Conventional ex-situ analyses often fail to capture such short-lived species, resulting in incomplete mechanistic interpretation. Techniques such as in-situ Raman, Differential Electrochemical Mass Spectrometry (DEMS), and Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) have been proven to be effective in evaluating the reaction intermediates and mechanism. In the following section, we will briefly discuss the above-mentioned techniques.

In-situ shell-isolated nanoparticle enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SHINERS)

Shell-isolated nanoparticle enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SHINERS) monitors the adsorption of the reactant and the reaction processes on the catalyst surface, providing insights into different intermediates adsorbed. In this technique, Au nanoparticles coated with SiO2 or TiO2 shells are deposited over the electrode surface as part of its preparation, enhancing the Raman signal and making it a non-invasive technique27. In-situ SHINERS requires a specialised electrochemical setup allowing simultaneous electrochemical measurements and vibrational analysis under operating conditions to monitor reaction intermediates and products. During eNO3RR, the acquired in-situ SHINERS spectral lines corresponding to NO3− and its reduced intermediates adsorbed on the catalyst surface appears in the range of 600 to 1700 cm−¹28. Stretching frequencies at ~1044 and ~1349 cm−1, which correspond to symmetric stretching of NO3− and symmetric NO₂ stretching of the nitrate ion, respectively, help to monitor the consumption of NO3− ions in solution during the reaction29. The adsorbed nitrite (NO2−) species, which is a crucial intermediate, could be detected by its characteristic N=O stretching mode peak at ~1335 cm−1, and the NH3 formation can be confirmed by the −NH2 bending vibration at ~1375 cm−129,30.

SHINERS has been recognised as an effective tool in determining the adsorbed intermediates and mechanism of eNO3RR in various recent studies. For example, the different orientation, modes of association and number of binding sites of nitrite ion (N-bound nitro, O-bound nitro, doubly O-bound chelating nitro, N- and O-bound bridging nitro, as shown in Fig. 3a), was determined based on the corresponding peaks observed in in-situ SHINERS29. Fang et al.31 demonstrated the progression of electrochemical ammonia synthesis from nitrate through SHINERS under varied applied potentials ranging from 0.7 V to −0.1 V (Fig. 3b). They found that at open circuit potential and 0.7 V (vs. RHE), a distinct peak at ~1049 cm⁻¹ was observed, attributed to the symmetric stretching of NO3− ions in solution. At 0.4 V vs. RHE, the adsorption of NO3− onto the catalyst surface takes place as evidenced by the appearance of four peaks: the NO stretching vibration of unidentate nitrate around 998 cm⁻¹, the symmetric and antisymmetric stretching of the NO2 group from chelated nitro configurations near 1125 and 1254 cm⁻¹,and the N=O stretching of a bridged nitro group at ~1439 cm⁻¹. At 0.2 V vs. RHE, the symmetric stretching of surface-adsorbed *NO3⁻ appeared around 1028 cm⁻¹, accompanied by symmetric bending vibrations of HNH at 1315 and 1374 cm⁻¹ and the N = O stretch of HNO around 1540 cm⁻¹. Finally, at 0.1 V, the HNO signal at 1540 cm⁻¹ rapidly diminished, while a new peak at 1591 cm⁻¹, corresponding to the antisymmetric bending vibration of HNH in NH3, emerged. This thorough investigation of the reaction intermediates helped them understand the mechanistic pathways of eNO3RR.

a Different conformations of adsorption for NO2−, NO and HNO on active centre M. Adapted with permission from ref. 29. © Elsevier. b SHINERS spectra between 750–1700 cm−1 on Cu50Co50 in 100 mM KNO3 + 10 mM KOH during cathodic polarisation from 0.7 to −0.1 V. Adapted with permission from ref. 31. © Springer Nature. c In-situ DEMS for the identification of potential intermediates and products involved in eNO3RR on hexagonal close-packed/face-centred cubic RuMo nanoflowers. Adapted with permission from ref. 38. © Wiley. d In-situ FTIR spectra collected for Pd/NF under –1.4 V vs. RHE in 0.1 M NaNO3–. Adapted with permission from ref. 41. © Wiley.

In-situ differential electrochemical mass spectrometry (DEMS)

In-situ DEMS is a cost-effective technique for monitoring the evolution of gaseous or volatile intermediates and products during electrocatalytic reactions. It offers potential, time, mass, and space-resolved data, which significantly enhances our understanding of reaction pathways and kinetics. Given the complexity of the eNO3RR, which involves multiple proton and electron transfers, DEMS plays a vital role by (a) elucidating reaction mechanisms, (b) tracing the nitrogen source, (c) evaluating the impact of reaction conditions, and (d) identifying by-products or competing reactions32,33,34,35,36,37. Reaction conditions such as pH and potential strongly influence the distribution of products, and DEMS provides a rapid and effective means of identifying optimal reaction conditions. In-situ DEMS have been reported to assist in real-time determination of reaction intermediates and products, and hence the mechanistic pathway. For instance, Wang et al.38 utilised in-situ DEMS for the identification of potential intermediates and products involved in eNO3RR on hexagonal close-packed/face-centred cubic RuMo nanoflowers (hcp/fcc RuMo NF). During linear sweep voltammetry (LSV), signals corresponding to m/z values of 2, 14, 15, 16, 17, 28, 30, 31, 33, and 46, representing H2, N, NH, NH2, NH3, N2, NO, HNO, NH2OH, and NO2, were detected (Fig. 3c). Based on the detection of strong *N and weak NH2OH signals, the proposed reaction pathway was established to proceed as: *NO3 → *NO2 → *NO → *N → *NH → *NH2 → *NH3. Similarly, Wang et al.39 detected m/z signals of 17, 30, and 31, corresponding to NH3, NOH, and NH2OH during NO3− electroreduction using disordered RuO2 nanosheet. In another study, Su et al.40 employed online DEMS to investigate the enhanced performance of oxygen-vacancy-rich Ru@P-Fe/Fe3O4 composite nanorods. Over three cycles ranging from −0.15 to −0.75 V vs. RHE, the m/z signals of 46, 31, 30, 17, 16, 15, and 14 corresponding to NO2, NOH, NO, NH3, NH2, NH, and N were observed. The detection of NO in the product stream highlights its role as a key intermediate in the eNO3RR pathway.

In-situ attenuated total reflection Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR)

In-situ FTIR spectroscopy is a widely employed technique for probing reaction mechanisms under real operating conditions. When infrared light interacts with a sample, specific molecular bonds absorb characteristic wavelengths, resulting in quantized vibrational or rotational energy transitions. Analysis of the absorbed light provides detailed information on molecular structure and bonding environments42. Owing to its high sensitivity, in-situ FTIR can detect subtle vibrational features of functional groups, making it particularly useful for tracking reaction intermediates43,44,45. An electrochemical in-situ FTIR setup integrates an infrared spectrometer with a reaction cell, where the working electrode is placed on an optical crystal, allowing reflected infrared radiation to capture the vibrational signatures of adsorbed species. For eNO3RR, careful monitoring of N–H, O–H, and N–O vibrations is essential to identify intermediate species46,47,48. For example, Guo et al.41 developed a nickel foam-supported palladium nanorod array (Pd/NF) and investigated its reaction pathways using in-situ FTIR. The gradual attenuation of the nitrate band at ~1232 cm⁻¹ reflected reactant consumption, while positive peaks at ~3336, ~1470, ~1329, and 1108 cm⁻¹ were attributed to intermediates including –NH2, monodentate nitrite (M–O–N–O), NO−, and NH3 (Fig. 3d). These findings highlight the capability of in-situ FTIR to unravel mechanistic details and track transient species in nitrate-to-ammonia conversion. Similarly, Hu et al.49 utilised in-situ ATR-FTIR to investigate the adsorption configurations of reactants and intermediates at different nitrate concentrations of 0.01 and 0.1 M. At the higher concentration of 0.1 M, *NO and *NH2OH species predominated over the Ru/Cu2O catalyst. In contrast, when the nitrate concentration was lowered to 0.01 M, the presence of *NO2, *NHO, and *NH3 intermediates was observed. This helped them understand the correlation between the nitrate concentration and hydrogen transfer kinetics, which assists in the hydrogenation of adsorbed NO3− to form NH3 against competitive HER.

The in-situ studies discussed above provide valuable insights about how catalysts behave under real reaction conditions, revealing how the surface structure, oxidation state, and local coordination environment evolve during nitrate reduction. These insights bridge the gap between mechanistic understanding and catalyst design, offering a clearer view of how specific local configurations of the active site govern activity and selectivity, thereby enabling more rational and targeted catalyst development. However, translating this knowledge into practical evaluation requires reliable methods to assess catalytic performance and validate mechanistic hypotheses. Therefore, before discussing catalyst design strategies, it is essential to examine the evaluation parameters, product detection techniques, and reactor configurations that underpin meaningful interpretation of ENRA activity and selectivity.

Evaluation and methodological considerations

Accurate evaluation of catalytic performance is crucial for drawing meaningful conclusions about reaction mechanisms and catalyst efficiency in ENRA. Variations in experimental setups and detection protocols can often lead to inconsistent or misleading comparisons across studies. Therefore, establishing standardised evaluation parameters, reliable product detection techniques, and well-designed reactor configurations is essential to ensure reproducibility and fair benchmarking of catalysts. This section summarises the key methodological aspects that influence ENRA performance assessment, providing a framework to connect mechanistic understanding with practical catalyst design.

Evaluation parameters for ENRA performance

Currently, eNO3RR are typically conducted in a three-electrode configuration using H-type cells. Prior to the main reaction, cyclic voltammetry (CV) or LSV is often employed to evaluate the catalyst’s electrocatalytic activity in electrolytes with and without nitrate. A noticeable increase in current density upon nitrate addition indicates the onset of reduction processes leading to products such as NO2− and NH3. To assess performance comprehensively, key parameters, including Faradaic efficiency (FE), product yield rate, nitrate conversion rate, selectivity, and half-cell energy efficiency, should be evaluated, which can provide quantitative insights into catalyst activity. In the following section, we will highlight each parameter briefly.

Faradaic efficiency (FE)

The FE for NH3 \(({{FE}}_{{{NH}}_{3}})\) formation reflects the proportion of total electrons that contribute specifically to nitrate reduction into ammonia. It directly represents the electron utilisation efficiency and is calculated from the ratio of experimentally consumed charge for NH3 formation to the total charge passed during electrolysis. FE of NH3 production can be expressed as50

Here, M denotes the molecular weight of NH3 (17 g mol‒1), Q is the total charge passed during electrolysis, n represents the number of electrons transferred (8), c is the concentration of generated NH3, V is the catholyte volume in the cathode chamber, and F is the Faraday constant (96,485 C mol‒1).

Yield rate

The NH3 yield rate \(({r}_{{{NH}}_{3}})\) quantifies the amount of ammonia generated per unit time and per unit catalyst mass or electrode area, expressed as mmol h‒1 cm‒2 or mmol h‒1 g‒1, respectively. This parameter provides a measure of catalytic productivity and practical applicability50.

Here, ‘S’ represents the geometric area of the working electrode and ‘m’ represents the loading mass of catalysts, and ‘t’ is the electrolysis time.

Conversion rate

The nitrate conversion rate \(({C}_{{{NH}}_{3}})\) indicates the fraction of initial nitrate ions transformed into ammonia, typically expressed as a percentage. It is particularly significant when evaluating performance in dilute nitrate electrolytes14.

Here, \(\Delta {C}({{NO}}_{3}^{-})\) is the concentration change of NO3‒ before and after electrolysis and \({C}_{0}\,({{NO}}_{3}^{-})\) is the initial concentration of NO3‒.

Selectivity

Selectivity toward NH3 \(({S}_{{{NH}}_{3}})\) represents the proportion of nitrate reduced to ammonia relative to all reduction products. Higher selectivity implies that most nitrate is converted to ammonia rather than to intermediate species such as nitrite or other by-products, thus improving process efficiency and product purity14.

Here, c(NH3) is the produced concentration of NH3.

Half-cell energy efficiency

Half-cell energy efficiency of NH3 production \(({{EE}}_{{{NH}}_{3}})\) evaluates how effectively the system converts electrical energy into chemical energy stored in ammonia. It is determined from the ratio of the theoretical energy for NH3 formation to the total input energy, considering the equilibrium potentials of nitrate reduction (\({E}_{{{NH}}_{3}}^{0}=\,\)0.69 V vs. RHE) and the oxygen evolution reaction (\({E}_{{OER}}^{0}=\)1.23 V vs. RHE). High half-cell energy efficiency indicates superior energy utilisation and industrial potential51.

Here \({E}_{{OER}}\) and \({E}_{{{NH}}_{3}}\) represents applied potential.

Product detection and quantification techniques

In the eNO3RR, NO3– can be converted into various products (NO2–, NH2NH2) other than NH3 through a series of deoxygenation and hydrogenation steps19. Accurate quantification of NH3 is essential for the evaluation of NH3 yield rate, conversion efficiency, FE, and overall eNO3RR performance. One of the methods for NH3 detection and quantification is ion chromatography (IC), which offers several distinct advantages: (1) high efficiency and convenience, enabling rapid and simultaneous detection of multiple ionic species; (2) high sensitivity, suitable for concentration ranges from a few µg L⁻¹ to several hundred mg L⁻¹; (3) high selectivity, allowing precise quantification of both inorganic and organic cations through tailored separation and detection conditions; and (4) excellent stability and compatibility, as the robust, high-pH-tolerant column materials permit the use of strong acid eluents, thereby broadening its applicability. However, IC analysis is limited by its high cost and the need for complex instrumentation, which may restrict its routine use52. Accordingly, the colorimetric technique based on ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) spectrophotometry and the Beer–Lambert law is the most widely used and convenient approach for determining the concentrations of NH3.

To quantify NH3 produced during the reaction, several reagent-dependent colorimetric methods have been developed, the most common being the indophenol blue (IB) and Nessler’s reagent (NR) methods. In the IB method, Berthelot’s reagent, composed of phenol (C6H6O) and hypochlorite (ClO‒) reacts with NH3 in the presence of a nitroprusside catalyst ([Fe(CN)5NO]2‒) to form indophenol, a blue-coloured compound (Scheme 1). Phenol is a corrosive and toxic compound, existing in both solid and liquid states, that readily interconverts at room temperature. To mitigate its hazardous effects, a safer alternative, salicylic acid/ salicylate, has been extensively used as a substitute53,54.

In contrast, the NR method employs an alkaline solution of potassium tetraiodomercurate (K2HgI4) and KOH, where the [HgI4]2‒ anion reacts with NH3 to form a reddish-brown complex according to the following reaction:

The concentration of NH3 is then determined by measuring the absorbance at ~655 nm for the IB method or ~420 nm for the NR method52.

The choice between these methods depends strongly on the pH of the analyte. Under neutral or alkaline conditions, both methods are effective; however, under acidic conditions, only the NR method is suitable, as hypochlorite in the IB reagent becomes unstable in acidic media. Since eNO3RR can be performed in acidic, neutral, or alkaline electrolytes, the analyte pH should be adjusted before adding the colour reagent, particularly when using the IB method. Although NR is applicable across a wide pH range, IB can provide comparable accuracy with proper pH adjustment and dilution. The choice of detection method also depends on the expected ammonia concentration and reaction conditions. While the Nessler’s reagent, indophenol blue, and ion chromatography methods are all accurate below 500 µg L⁻¹, the indophenol blue method performs poorly at higher concentrations and under acidic conditions. However, due to the toxicity, interference by metal ions (Fe2+, Ni2+, Ru3+, In3+) and limited stability of NR, as well as its sensitivity to reaction time, the IB method is generally preferred for convenience and safety52. Irrespective of the detection method, the catalyst material must be free of pre-existing NHx species prior to testing. If present, control and blank experiments are essential to identify any extraneous sources of ammonia. Therefore, for the reliable quantification of ammonia, using multiple complementary methods is always recommended.

Role of nitrate concentration, pH and reactor design

In the eNO3RR, nitrate solutions are commonly employed as electrolytes; however, their concentration variation can influence the charge distribution and reaction kinetics at the electrode surface, thereby affecting both the reduction rate and product distribution during the eNO3RR55,56. From a practical standpoint, the nitrate concentration in different waste streams and water sources can vary considerably. For instance, contaminated drinking water typically contains ~1.5 × 10–3 mol L–1 of nitrate while effluents from ion-exchange resin regeneration processes may reach concentrations of around 1.5 × 10–2 mol L–157,58. In contrast, nitrate concentrations in nuclear wastes exceeds 1 mol L–159. Therefore, understanding the influence of nitrate concentration is crucial for optimising reaction conditions and improving the efficiency and selectivity of nitrate conversion processes. Fan et al. examined how the variation of NO3– concentration affects the adsorbed hydrogen (Hads) consumption capacity and nitrate to ammonia conversion60. They found that at lower potentials (0 to –0.23 V), changes in nitrate concentration (NO3–) exerted no significant influence on NH3 production, primarily due to the limited formation of Hads. Conversely, at more negative potentials, the NH₃ yield and FE increased significantly with higher NO3– concentration. Based on this behaviour, they suggested that, under conditions with sufficient Hads availability, elevated nitrate concentrations help maintain the dynamic equilibrium of Hads while suppressing the competing HER, thereby promoting enhanced NH3 generation. To get insights into the kinetic behaviour of nitrate reduction under varying concentration regimes, Taguchi et al. examined the dependence of nitrate concentration on Pt(110) in 0.1 M HClO4 containing KNO361. The reaction exhibited zero-order dependence with respect to nitrate concentration, suggesting that NO3– adsorption occurs on the electrode surface until saturation was achieved. They found that the Tafel slope for nitrate reduction on Pt(110) at varying nitrate concentrations ranges around −66 ± 2 mV dec−1, which implies that electron transfer does not occur during the rate-determining step; instead, the process proceeds through a purely chemical reaction pathway on Pt(100), involving the interaction of adsorbed nitrate with hydrogen adatoms (Hads). Katsounaros et al. expanded this understanding to higher concentration domains, demonstrating a clear transition from first-order to zero-order kinetics as nitrate concentration increases56. At nitrate concentrations below 0.3 M, the reaction exhibits first-order kinetics; however, at higher concentrations, it shifts to zero-order kinetics. This transition is likely caused by surface site saturation, suggesting that the regeneration of active catalytic sites governs the reaction rate under these conditions. Moreover, as the NO₃⁻ concentration increases from 1.5 × 10−3 to 25 × 10−3 mol L−1, the selectivity toward N₂ rises from 70% to 83% and remains nearly constant at higher NO3– concentrations. In contrast, the FE for NH3 decreases from 25% to 11%. However, with a further increase in NO₃⁻ concentration, the total FE for both products increases significantly from 25% to 78% at 0.1 mol L−1, ultimately reaching 95% at 1 mol L−1 during the eNO3RR process. Consistent with the observed transition from first- to zero-order kinetics at higher concentrations, Zhang et al. evaluated the catalytic performance of Fe/Cu-HNG catalyst across a range of nitrate concentrations (15–100 mM) and demonstrated that lower nitrate concentrations limit ion diffusion toward the catalytic surface, resulting in reduced yield rates37. In contrast, elevated concentrations facilitated enhanced mass transport and improved catalytic performance, although the competing HER became more prominent at more negative potentials. Similarly, Wang et al. reported a clear enhancement in NH3 FE with increasing nitrate concentration using a Cu50Ni50/PTFE alloy catalyst, supporting the notion that higher nitrate availability sustains active surface reactions and promotes ammonia formation62. These findings emphasize that nitrate concentration serves as a decisive parameter in governing both the reaction kinetics and product selectivity of eNO3RR systems. Variations in nitrate concentration not only modulate the interfacial charge distribution and diffusion dynamics but also determine the dominant reaction pathway and product selectivity. At low concentrations, limited nitrate availability restricts surface coverage and mass transport, resulting in lower reaction rates and reduced ammonia yields. Conversely, higher nitrate concentrations promote enhanced surface adsorption, sustained Hads equilibrium, and suppression of the competing HER, thereby improving both FE and product yield.

In addition to the concentration of nitrate in the electrolyte, the pH of the electrolyte also plays a crucial role. However, the selectivity of a catalyst toward ammonia formation is primarily governed by the nature of its active sites rather than by electrolyte pH, as the reaction kinetics are dictated by the adsorption energetics of reactants and intermediates. Nevertheless, electrolyte pH can influence proton availability, charge transfer, and the stability of catalysts, electrodes, and intermediates. Meng et al. systematically investigated the pH dependence of eNO3RR on Fe–N–C single-atom catalysts (SACs) through combined experimental and computational analyses63. Their results revealed consistently high activity and >80% FE for NH3 production across acidic, neutral, and alkaline media. Interestingly, HER was found to compete most strongly with nitrate reduction under alkaline conditions, leading to reduced selectivity for NH3 at equivalent potentials.

Beyond catalyst development and electrolyte optimisation, the rational design of electrochemical reactors plays a crucial role in enhancing the performance of eNO3RR. Presently, studies on eNO3RR are commonly conducted using either single-chamber or dual-chamber (H-type) reactors64,65. In a single-chamber configuration, a conventional three-electrode setup comprising a reference, counter, and working electrode is immersed in the electrolyte mixture. However, during NO3– reduction, partially reduced intermediates can diffuse towards the anode and undergo re-oxidation, thereby diminishing the overall FE. To mitigate this issue, a proton exchange membrane, such as Nafion-117, is often introduced between the anode and cathode compartments to create an H-type cell. This separation effectively isolates the cathodic ammonia synthesis reaction from anodic oxygen evolution, preventing oxidation of intermediates and consequently improving NH3 yield and selectivity. Despite these advantages, H-type reactors suffer from limited mass transport, as reactants rely on diffusion to reach the electrode, leading to low current densities and inefficiencies. Membrane resistance further increases cell voltage. Hence, current efforts focus on reactor designs that enhance mass transfer and selectivity for scalable eNO3RR applications66. To meet industrial and commercial demands, it is essential to minimise internal resistance within electrolyzers by eliminating liquid electrolytes between electrodes. This has been achieved through the development of membrane electrode assemblies (MEAs), in which an ion-exchange membrane is directly sandwiched between the electrodes, resulting in low ohmic resistance and improved energy efficiency67,68. For large-scale applications, multiple MEA units can be integrated into an electrolyzer stack to enhance throughput69. For instance, Hu et al. employed MEA to keep nitrate on the catalyst surface for a prolonged time, facilitating complete reduction and improved diffusion through localised turbulence49.

Conventional MEAs typically employ either a cation exchange membrane (CEM) or an anion exchange membrane (AEM); however, both present challenges. CEMs can lead to the crossover of cationic products (e.g., NH4+), while AEMs allow the migration of anionic species (e.g., NO3–, NO2–), reducing overall system efficiency and economic viability. To overcome these limitations, bipolar membranes (BPMs), composed of both a cation exchange layer (CEL) and an anion exchange layer, have been introduced70. BPMs effectively suppress ion crossover by generating H+ and OH‒ in-situ at the membrane interface during operation. The CEL is typically oriented toward the cathode, ensuring a stable supply of protons for the reduction reaction. The versatility of BPMs enables further modification of the reaction microenvironment. For instance, Huang et al. incorporated a mixed cellulose ester interlayer between the BPM and Cu electrode to regulate proton transport and suppress the competing HER71. At low potentials, this interlayer effectively limited proton diffusion, enhancing NH3 yield and FE. At higher potentials, the addition of carbonate ions absorbed excess protons, further mitigating HER and promoting selective nitrate reduction. To advance MEA performance, a polymer solid electrolyte-cation exchange membrane assembly (PSE‒CEM‒MEA) was subsequently developed72. This configuration introduces a double CEM layer with a thin, porous solid electrolyte, i.e., a polymer-based solid-state ion conductor in between. The PSE layer, composed of sulfonated styrene-divinylbenzene copolymer, maintains low interfacial resistance while enabling controlled ion transport. During operation, Na⁺ ions from an intermediate NaOH solution migrate through the CEM, forming a shielding layer at the cathode surface that prevents proton access and elevates local pH, thereby suppressing HER. The generated ammonia can be efficiently recovered by steam stripping, while the NaOH solution is recycled into the system, eliminating the need for frequent electrolyte replenishment. Overall, these advances in MEA and membrane architecture design, including BPM and PSE–CEM configurations, demonstrate effective strategies to suppress HER, enhance NH3 selectivity, and improve both energy efficiency and sustainability in eNO3RR systems.

Designing electrocatalysts

The development of efficient electrocatalysts is critical for economically viable production of NH3 from NO3−. For a given catalyst, activity is primarily influenced by the applied potential and the adsorption strength of reaction intermediates, which in turn affect the surface concentrations of reactants and intermediates73. In eNO3RR, the adsorption energies of nitrogen and oxygen atoms directly impact catalytic performance, while the applied potential further modulates this relationship. Liu et al.74 used DFT-based mean-field microkinetic modelling to examine the eNO3RR activity of various transition metals (Cu, Co, Rh, Pd, Ag, Pt) at different potentials (−0.2 V to 0.4 V vs. RHE) and utilised adsorption energies of oxygen (ΔEO) and nitrogen (ΔEN) as descriptors. The relative adsorption energies help predict the surface coverage of key intermediates like NO2*, O*, and H*, and suggest the predominant product formed, such as NO, NH3, N2, or N2O (Fig. 4a). For example, metals like Fe or Co, with high adsorption energies for O and N (ΔEO and ΔEN), are expected to favour N2 formation. In contrast, metals like Ag or Co, with lower adsorption energies, tend to produce NO. The electrocatalytic NH3 production activity is associated with intermediate, well-balanced ΔEO and ΔEN values (Fig. 4a).

a Theoretical volcano plots of the TOF as a function of ΔEO and ΔEN for electrocatalytic nitrate reduction on transition metal surfaces based on DFT-based microkinetic simulations at a) -0.2 V, b) 0 V, c) 0.2 V, and d) 0.4 V vs. RHE. Adapted with permission from ref. 74. © American Chemical Society. b Theoretical selectivity maps to NO, N2O, N2, or NH3 products from electrocatalytic nitrate reduction as a function of oxygen and nitrogen adsorption energy at a) -0.2 V, b) 0 V, c) 0.2 V, and d) 0.4 V vs. RHE. Adapted with permission from ref. 74. © American Chemical Society. c The differences between the limiting potentials for the eNO3RR and HER. Adapted with permission from ref. 75. © Royal Society of Chemistry.

Selectivity is another essential criterion when designing electrocatalysts for eNO3RR, due to the presence of multiple possible products such as HN3, N2, N2O, and NO. As with activity, both adsorption energies (ΔEO and ΔEN) and the applied potential play significant roles in determining selectivity. Liu et al. established that more negative potentials tend to favour NH3 formation, whereas more positive potentials shift selectivity toward N2, which has a higher standard reduction potential (E⁰ = 1.25 V vs. RHE). Formation of N2 requires strong adsorption of both N and O atoms, while NH3 production is favoured by moderate adsorption strengths. (Fig. 4b) However, competition with the HER, especially under negative potentials, remains a challenge. Since *H binding energy serves as a descriptor for HER activity. A high surface coverage of *H can block active sites, preventing the adsorption of NO3⁻ or its intermediates, resulting in a low FE for nitrate reduction. Consequently, noble metals are generally unsuitable for efficient eNO3RR to NH3, as their strong *H adsorption favours the competing HER. Karamad et al.75 compared the limiting potentials for HER and eNO3RR across various metals. Their analysis showed that the difference in limiting potential between eNO3RR and HER indicates the catalyst’s selectivity toward eNO3RR over HER. Pd exhibited a very low FE for NH3 production, primarily due to the dominance of the HER and the complex multi-step pathway from NO3− to NH3, which involves numerous nitrogen-containing intermediates like NOx, N2H4, and NH2OH76. The optimal catalysts, those both active and selective, lie in the upper-right quadrant of the comparison plot (Fig. 4c).

Strategies to design catalyst for ENRA

The above discussion suggests that modulating the binding energy of different reaction intermediates is crucial to enhance ammonia selectivity and efficiency. Moderate adsorption of O and N is vital for NH3 formation. Researchers have developed various strategies to modulate the intermediate binding energies of eNO3RR to enhance ammonia production selectivity. In this section, we provide an overview of the common strategies adopted by the scientific community to design catalysts for ENRA as summarised in Table 1.

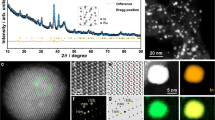

Crystal facet regulation

The catalyst surface plays a crucial role as its atomic structure governs key physical and chemical characteristics, such as surface energy, Fermi level, and the bonding geometry (including atomic distances and angles) of adsorbed intermediates77,78. It is well established that electrochemical reaction steps can differ based on the crystallographic facets of catalysts. This becomes especially significant when multiple reactants and reaction pathways compete on the surface, as specific facets exhibit varying affinities for intermediate species. Consequently, facet orientation can strongly influence both selectivity and activity, offering a means to tailor catalytic performance79,80. Han et al.81 synthesised Pd seed-assisted Pd nanocrystalline with different exposed facets, showing differences in activity, and therefore, established a desired facet-engineered electrocatalyst that could be utilised for efficient eNO3RR into NH3. They showed that in a mixture of 0.1 M Na2SO4 and 0.1 M NO3⁻, Pd octahedrons (111) displayed higher FE and ammonia yield rate compared to Pd cubes (100) and Pd rhombic dodecahedrons (110), achieving a maximum ammonia yield rate of 0.5485 mmol h−1 cm−2 with a FE of 79.91% at −0.71 V vs. RHE. They rationalised the higher activity of Pd (111) facet through DFT studies and substantiated that optimised absorption of NO3− over the (111) facet, poorer response towards HER, and the lower free energy change value at the rate-determining step contributed towards excellent performance of Pd (111) towards eNO3RR to NH3. But, due to the high cost of noble metal, Pd, there is an inclination towards transition metal-based catalysts. Through DFT calculations, Hu et al.82 showed that Cu(111) and Cu(100) surfaces are more active towards eNO3RR as compared to the Cu(110). Moreover, each copper facet demonstrates optimal performance within specific pH ranges: Cu (111) performs best in moderately acidic to alkaline conditions (pH 5.63 to 14), while Cu (100) is more effective in strongly acidic environments. These variations in activity were attributed to differences in the local atomic coordination and electronic structure across the different copper surfaces. These theoretical insights have been experimentally established by Fu et al.83. They developed different facet-engineered copper-based catalysts through solution phase synthesis and compared their electrocatalytic behaviour towards nitrate reduction to ammonia. They reported excellent catalytic activity of Cu (111) nanosheets, achieving an ammonia yield rate of 390.1 μg mgCu−1 h−1 and a FE of 99.7% at −0.15 V (vs. RHE), surpassing Cu (200) nanocubes and Cu nanoparticles with no preferential facet orientation. They established that the (111) facet of Cu nanosheets is active towards eNO3RR to ammonia, and the effectiveness of the reaction is sensitive to the catalyst structure. Hu et al.84 developed Cu (100)-rich rugged Cu-nanobelt (Cu-NBs-100), an electrocatalyst with (100) exposed facets and abundant surface defects. The Cu-NBs-100 exhibited outstanding performance for the eNO3RR, requiring only a low potential of –0.15 V vs. RHE to achieve a FE of 95.3% for NH3 and a peak NH3 production rate of 650 mmol gcat−1 h−1. They correlated the relatively high performance of Cu-NBs-100 to the synergistic interaction between Cu (100) facets and surface defects, resulting in an upshift of the Cu d-band centre, which strengthened the adsorption of NO3− and H*. This dual effect simultaneously enhanced eNO3RR activity and suppressed HER, enabling highly selective nitrate reduction (Fig. 5). In order to improve the selectivity, Qin et al.85 developed Cu2O (100) and Cu2O (111) facets using a very simple chemical reduction method. They showed that the partially unoccupied Cu 3d orbitals on the Cu2O (100) surface were more effective than those on Cu2O (111) in accepting electrons from the Cu2O bulk and NO3⁻ adsorption. As a result, Cu2O (100) achieved a superior NH4⁺ yield rate of 743 μg h⁻¹ mgcat⁻¹ and a high FE of 82.3% at −0.6 V vs. RHE. While many studies have examined the impact of exposed crystal planes on eNO3RR performance, the role of structural disorder has received limited attention. Leveraging the inherent structural flexibility and abundance of active sites in amorphous materials, Wang et al.39 synthesised structurally disordered RuO2 nanosheets. Both experimental and DFT analyses revealed that the amorphous RuO2 (a-RuO2) surface featured numerous oxygen vacancies due to its disordered atomic structure. These vacancies promoted the potential-determining NH2* → NH3* step and adjusted hydrogen binding affinity, resulting in a superior ammonia FE (97.46%) and selectivity (96.42%) compared to low- and high-crystalline RuO2.

a Calculated adsorption free energies (ΔG) of NO3* on Cu (111), Cu (100), and defect-rich Cu (100)-D surfaces (D1–D7 represent different defect sites). b Optimized configurations of NO3* adsorbed (Cu = blue, O = red, N = white). c FT-IR spectra of NO3* adsorption on Cu-NBs-100 and Cu-NBs-111. d Density of states (DOS) of Cu surfaces and e calculated adsorption free energies of H* intermediates on Cu (111), Cu (100), and Cu (100)-D7. f Free energy profiles for NH3 formation from eNO3RR on the three surface models. Adapted with permission from ref. 84. © Royal Society of Chemistry.

Overall, crystal facet engineering has proven to be an effective approach for tuning the adsorption strength and reaction pathway of nitrate intermediates, thereby enhancing both activity and selectivity toward ammonia formation. However, achieving precise control over facet exposure, maintaining surface stability under reaction conditions, and translating nanoscale morphology to industrially relevant scale remain key challenges. Moreover, the interplay between crystal facets, surface defects, and amorphous domains is not yet fully understood. Future studies combining facet control with defect or strain engineering, supported by in-situ spectroscopic verification, could provide deeper mechanistic insight and guide the rational design of practical ENRA catalysts.

Spatial confinement of single atoms and dual single atoms

Catalytic activities of any material are determined not only by the type but also by its size. Downsizing a metal catalyst into a single atomic form with no metallic bonding completely changes its electronic properties from the bulk metal86. Confining single atoms and dual single atoms into the matrix of a host material are termed as SACs and dual single-atom catalysts (DSACs), respectively. After its first introduction in 2011, SACs and DSACs have attracted a great deal of interest in the scientific community due to their high catalytic efficiency and high atom utilisation87,88. Host materials play an important role in SACs and DSACs since they stabilise the singly dispersed metal atoms through chemical bonding. The local environment of the single atom, determined by the number and nature of neighbouring atoms and their arrangement in different coordination spheres (up to 2nd), defines the electronic properties and geometric structure89. These properties help tune the metal-host material interaction, further determining the catalytic activity90.

In nature, ferredoxin-dependent nitrite reductase, common in green algae and cyanobacteria, actively facilitates ammonia production via photosynthetic nitrate assimilation. Drawing inspiration from the single iron active site in these enzymes, Li et al.91 developed a densely populated Fe-PPy SAC, synthesised from ferric acetylacetonate/polypyrrole hydrogel precursors. The catalyst showed a maximum NH3 yield rate of 2.75 mg h⁻1 cm⁻2 (~30 mol h⁻1 gFe) with nearly 100% FE. Additionally, the isolated atomic Fe sites exhibited a turnover frequency twelve times greater than that of metallic Fe nanoparticles. Analysis of by-products in the presence of NO3− showed that single-site Fe catalysts produced no detectable H2, whereas notable water dissociation occurred on bulk Fe surfaces (Fe NPs) and the carbon support under negative potentials. In-situ X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy revealed that Fe sites with nitrogen coordination (Fe(II)-Nx) exclusively adsorb NO3− over water molecules and effectively eliminate HER. Moreover, the high redox reversibility of Fe single sites promotes selectivity and efficiency of ammonia production.

Analogously, taking cues from iron-based compounds utilised in H–B catalysis, Wu et al.11 prepared Fe SAC through a transition metal-assisted carbonisation process utilising SiO2 powders as hard templates. The Fe SAC exhibited high activity towards ENRA with a FE of ~75% at −0.66 V vs. RHE and yield rate of ~20,000 μg h−1 mgcat−1. Fe SAC, having a comparatively lower Fe content than Fe nanoparticles (Fe NPs), showed significantly higher catalytic activity, proving the fact of maximum atom utilisation and enhanced activity of SACs. The lack of presence of neighbouring Fe active centre in the Fe SAC helped in the prevention of N-N coupling and hence N2 production. They attributed the Fe–N4 motif as the active sites in Fe SAC for its enhanced performance. Moreover, they also proposed the mechanistic pathway for the eNO3RR to produce NH3 over the Fe SAC (Fig. 6a) based on the DFT study which revealed that the NO* reduction to HNO* and HNO* reduction to N* are the potential limiting steps and a limiting potential of −0.30 V is required to facilitate all the free energy steps downward (Fig. 6b).

a Proposed reaction mechanism to produce NH3 b Free energy vs. reaction coordinate diagram of the proposed mechanism at minimum energy (U = 0) and limiting potential (U = −0.30 V). Adapted with permission from ref. 11. © Springer Nature.

Motivated by the Sabatier principle, which positions Ru at the peak of the volcano plot for H–B ammonia synthesis92, Ke et al.93 synthesised singly dispersed Ru sites on nitrogenated carbon (Ru-SA-NC). The Ru-SA-NC exhibited impressive activity towards selective nitrite and nitrate reduction into ammonia with FE of 97.8% at −0.4 V and 72.8% at −0.6 V, in an alkaline medium. They substantiated the impressive activity of Ru SA-NC to the favourable occurrence of the potential rate-limiting step *NO→ *NOH process on single Ru-sites. Cu-based electrocatalysts have been extensively studied for ENRA, owing to their excellent electrochemical performance, adjustable electronic properties, and affordability94,95. However, major challenges such as catalyst deactivation over prolonged use due to passivation, leaching, and corrosion, and the buildup of nitrite as a by-product, hinder their practical application95. To overcome these difficulties, a promising strategy is to downsize the particles on an atomic scale. Zhu et al., in their work, prepared Cu-SAC on a nitrogenated carbon network (Cu–N–C)96. They established that Cu atoms anchored on nitrogen-doped carbon nanosheets exhibited stronger interactions with NO3⁻ and NO2⁻ compared to Cu nanoparticles and bulk Cu metal. Computational results revealed that Cu-Nx sites, especially Cu-N2 played a vital role in enhancing the adsorption of reaction intermediates. As a result, single-atom Cu catalysts not only significantly accelerated the eNO₃RR but also effectively suppressed the release of nitrite into the solution. Along with Cu, Zn is one of the most abundant, non-toxic, and comparatively cheaper transition metals. Inspired by the work of Li et al.97, where they showed ZnCo2O4 supported on carbon cloth being an efficient electrocatalyst for ammonia synthesis, Zhao et al. thought of exploring Zn-single atomic sites. Zhao et al.98 showed that Zn single atoms anchored on microporous N-doped carbon (ZnSA-MNC) exhibited high activity and selectivity for eNO3RR, achieving 97.2% NO₃⁻ conversion, 94.9% NH3 selectivity, and an NH3 yield rate of ~ 39,000 μg h⁻1 mgcat⁻1 (2.31 mmol h⁻1 mgcat⁻1) at −1.0 V vs. RHE, with a peak FE of 94.8% at −0.9 V vs. RHE.

Previous studies have shown that for several monometallic catalysts (e.g., Cu, Rh, Pd, and Pt), the hydrogenation of NO2⁻ to NH3 becomes the rate-determining step at low overpotentials, as it proceeds more slowly than the initial NO3⁻ to NO2⁻ conversion and consequently, *NO2 tends to desorb from the catalyst surface, leading to the accumulation of NO2− in the electrolyte74,99. For example, Cu-based catalysts commonly yield NO2⁻ rather than NH3, achieving nearly 100% FE for NO2⁻ production at 0 V vs. RHE100. The further hydrogenation of NO2− is limited under low overpotentials due to insufficient surface-adsorbed hydrogen (*H)94. Although higher overpotentials can facilitate water dissociation to generate *H, enhancing the successive reduction and hydrogenation of NO2⁻ beyond the NO3⁻ to NO2⁻ step64, these conditions also favour the HER74. Ultimately, a key limitation of monometallic catalysts lies in their inability to efficiently catalyse both NO3⁻ to NO2⁻ and NO2⁻ to NH3 steps concurrently. To overcome these, DSACs become relevant towards eNO3RR. Wan et al.101 designed a Fe-Mo DSAC and established the synergistic roleplay of Fe and Mo single atom catalysts towards the conversion of NO3− into NH3 with a high selectivity and activity. In the Fe-Mo DSAC catalyst, Mo single atomic sites preferentially convert NO3− into NO2− intermediate, which undergoes further protonation on Fe atomic sites, resulting in the formation of NH3. Synergistic role-playing of Fe and Mo helped to achieve a maximum yield rate of 13.56 mg cm−2 h−1 and FE of 94%, overcoming the shortcomings of individual Mo SAC (low NH3 selectivity, FE < 60%) and the Fe SAC (low ammonia yield rate, <6.5 mg cm-2 h-1).

On a similar line of thought, Zhang et al.37 synthesised a heteronuclear diatomic catalyst (Fe/Cu-HNG) where Fe and Cu active metals are anchored to the holey edge sites of nitrogen-doped graphene (HNG), where each metal centre is coordinated with two nitrogen atoms of the support and the other active metal resembling a “Y-type” ML3 unit structure with a configuration of N2Fe-CuN2. They reported a high catalytic activity of the catalyst with a FE of 92.5% towards NH3 at −0.3 V vs. RHE and a maximum yield rate of 1.08 mmol h−1 mg−1 at −0.5 V vs. RHE. Operando DEMS and DFT calculations revealed that Fe/Cu diatomic sites exhibit strong interactions with NO3− and moderate binding with key intermediates, thereby facilitating NH3 production with reduced energy barriers compared to Fe/Fe and Cu/Cu configurations. This synergistic behaviour accounts for the faster kinetics and enhanced catalytic activity.

Single-atom and dual-atom catalysts have opened new possibilities for ENRA by maximising atom utilisation and enabling precise control over active-site chemistry. However, challenges such as atom migration under operating conditions and difficulties in probing true active configurations still hinder practical deployment. Future work should focus on stabilising atomic sites under dynamic conditions and exploring synergistic dual-atom combinations to couple multi-step nitrate reduction more efficiently.

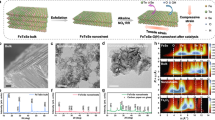

Regulating microenvironments and tailoring defects

It has been reported that amorphous metal particles may possess superior catalytic performance for electrochemical ammonia synthesis compared to their crystalline counterparts102,103,104. This enhancement is attributed to the high density of low-coordination surface atoms in amorphous structures, which generate “dangling bonds” and offer a greater number of active catalytic sites. Based on this idea, Jian et al.105 presented a straightforward ambient chelated co-reduction method for the in-situ synthesis of ultrafine, amorphous ruthenium (Ru) nanoclusters of diameter ~1.2 nm, uniformly anchored on carbon nanotubes (CNTs). When employed for eNO3RR, amorphous Ru nanoclusters on CNTs (denoted as a1-Ru/CNTs) achieved a high ammonia yield of 145.1 μg h⁻¹ mgcat⁻¹ and an FE of 80.62%, substantially outperforming crystalline Ru nanoclusters on CNTs (c-Ru/CNTs) (69.54 μg h⁻¹ mgcat⁻¹ and 43.02%, respectively). The a1-Ru/CNTs catalyst also demonstrated remarkable stability, maintaining catalytic performance with negligible degradation over prolonged testing. They deduced that a1-Ru/CNTs possessed abundant low-coordinated Ru active sites compared to their crystallized counterpart and therefore a1-Ru/CNTs exhibited a superior catalytic ability. Li et al.106 also engineered a Ru-based strained electrocatalyst, Ru/oxygen-doped-Ru core–shell nanoclusters for the ENRA. The incorporation of oxygen dopants induced tensile strain by expanding the Ru lattice, which helped to suppress the competitive HER effectively while facilitating the formation of adsorbed hydrogen (·H) by lowering the energy barrier for hydrogen–hydrogen coupling. The generated ·H species enhanced the hydrogenation of reaction intermediates, driving the reaction towards ammonia production. As a result of simultaneously inhibiting HER and promoting eNO3RR, they achieved a high ammonia synthesis rate at room temperature with a maximum yield of 5.56 mol gcat–1 h–1 and nearly 100% FE. Inspired by the superior ORR activity of Pd-based catalysts and the impressive response of vacancy-engineered TiO2 catalyst, Guo et al.107 synthesised Pd-doped TiO2 (Pd/TiO2) nanoarray catalyst for eNO3RR towards ammonia formation coupled with energy supply application. The Pd-doping widened the interplanar distances in the TiO2 lattice along with the introduction of dislocations and distortion defects, which played a role in favouring eNO3RR. The Pd/TiO2 nanoarray catalyst demonstrated a remarkable ammonia FE of 92.1%, an exceptional nitrate conversion efficiency of 99.6%, and a record-high ammonia yield of 1.12 mg cm−2 h−1, showing a significant improvement compared to the pristine TiO2 nanoarray catalyst. Investigating the O-2p orbitals with the density of states (DOS) calculations, they proved that Pd/TiO2 showed a stronger capacity towards capturing electrons from reactant species, NO3−, than pristine TiO2 and thus showed relatively higher activity (Fig. 7). Moreover, the free energy calculation revealed that the Pd/TiO2 has lower adsorption energy for the ENRA intermediates (Fig. 7e).

Electron density map of a TiO2 and b Pd/TiO2 c O 2p PDOS of free NO3−, TiO2 and Pd/TiO2 d electron density mapping of Pd/TiO2(left) and Pd/TiO2-NO3− (right). e Plot of free energy vs. reaction coordinates for ENRA over TiO2 and Pd/TiO2. Adapted with permission from ref. 107. © Royal Society of Chemistry.

Previous studies have demonstrated that noble metals such as Pt, Rh, and Ru exhibited excellent performance in eNO3RR74,106,108. However, limited availability and high cost significantly hinder practical applications of noble metal-based catalysts. In contrast, earth-abundant transition metal oxides not only offer promising activity for eNO3RR but also present considerable value-added applications109,110,111. For instance, the monometallic oxide Co3O4 has shown catalytic response in this context112,113. Nevertheless, monometallic oxides still face challenges, including poor electrical conductivity, suboptimal NO3− adsorption, and insufficient suppression of the HER. To address these limitations, spinel-type oxides (AB2O4) such as NiCo2O4,(ref. 114) ZnCo2O4,(ref. 97) MnCo2O4,(ref. 115) and FeCo2O4(ref. 116) have attracted significant attention for eNO3RR applications in recent years. Their advantages include flexible cation arrangements and enhanced electronic conductivity. Among them, the bimetallic oxide NiCo2O4 has been reported to be at least twice as conductive as the monometallic Co3O4114. Most studies suggested that bimetallic oxides generally exhibited superior conductivity compared to their monometallic counterparts. Moreover, their outstanding catalytic activity was attributed to the optimised adsorption energies of reaction intermediates and enhanced nitrate adsorption, facilitated by interactions between the two metal components commonly referred to as microenvironment regulation, which also helped in suppressing HER. Liu et al. explored the electrocatalytic nitrate reduction activity of NiCo2O4 nanowire array. This nanowire array was grown directly on carbon cloth, referred to as NiCo2O4/CC, eliminating the need for polymer binders such as Nafion, which can hinder performance114. The NiCo2O4/CC catalyst demonstrated exceptional eNO3RR activity, achieving a nitrate reduction rate of 973.2 μmol h⁻1 cm⁻2 and a FE of 99.0% at −0.3 V vs. RHE. A key factor contributing to this performance is the emergence of half-metallic characteristics on the NiCo2O4 (311) surface. This behaviour is attributed to the substitution of Co3⁺ ions by Ni2⁺ at octahedral sites, effectively acting as p-type dopants in the Co3O4 lattice. Such microenvironmental regulation enhances electron transfer during the eNO3RR process. In contrast, the Co3O4 (311) surface exhibits semiconducting properties, resulting in less efficient electron transport. The distinct electronic structures of NiCo2O4 and Co3O4 surfaces contributed to their differences in catalytic performance. Notably, the NiCo2O4 (311) surface binds NO3⁻ more strongly than hydrogen atoms, improving selectivity and suppressing the HER. Overall, NiCo2O4 offered significant advantages over Co3O4 in terms of electrical conductivity and HER suppression, which were the primary reasons for its superior eNO3RR performance. Additionally, the presence of oxygen vacancies (a result of defect engineering) can lower the free energy of nitrate adsorption, while also tune the d-band centre and modulate hydrogen affinity39,47. Du et al.117 reported that defective Fe2TiO5 nanofibers containing abundant oxygen vacancies exhibited a notably low free energy for nitrate adsorption ( − 0.28 eV), resulting in a high ammonia yield of 0.73 mmol h⁻1 mg⁻1 and a FE of 87.6%. Notably, the enhancement of eNO3RR performance through the introduction of oxygen vacancies has also been observed in monometallic oxides such as TiO2, RuO2, and others39,47. Wang et al.118 developed a dual-site electrocatalyst comprising oxygen vacancy (Ov)-enriched MnO2 (MnO2-Ov) nanosheets and Pd nanoparticles (deposited over MnO2), constructed over three-dimensional porous nickel foam (Pd-MnO2-Ov/Ni foam). The Pd–MnO2-Ov/Ni foam could achieve a NH3 selectivity of 87.64% at −0.85 V vs. Ag/AgCl and delivered NO3− conversion rate of 642 mg N m−2electrode h−1, outperforming both Pd/Ni foam (NH3 selectivity 85.02% and conversion rate of 369 mg N m−2electrode h−1) and MnO2/Ni foam (NH3 selectivity 32.25% and conversion rate of 118 mg N m−2electrode h−1). They rationalised that the Ov sites over MnO2 nanosheet arrays helped in the adsorption and activation of NO3− species, while Pd-sites helped in H2 adsorption and subsequent protonation to yield NH3. Wang et al.111 developed Cu/oxygen vacancy-rich Cu-Mn3O4 heterostructured ultrathin nanosheet arrays grown on copper foam (Cu/Cu-Mn3O4 NSAs/CF) electrocatalyst combining interface and defect engineering techniques. These self-supported nanosheet arrays feature a carefully designed composition and architecture, offering numerous exposed active sites, a tuned electronic structure, and strong interfacial synergy. Owing to these advantages, the Cu/Cu-Mn3O4 NSAs/CF exhibited excellent electrocatalytic performance for ENRA. The catalyst achieved a high nitrate conversion efficiency of 95.8%, ammonia selectivity of 87.6%, ammonia production rate of 0.21 mmol h−1 cm−2, and FE of 92.4%. Inspired by the unique architecture of enzymes, where the active metal centre and surrounding protein scaffolds collectively govern high activity, Chen et al.119 reported a novel metal-mediated organic molecular solid catalyst by incorporating Cu in 3,4,9,10-perylenetetracarboxylic dianhydride (PTCDA) for ENRA. The Cu-PTCDA molecular solid catalyst achieved a maximum FE of 85.9% at −0.4 V vs. RHE and exhibited an NH3 yield rate of 436 ± 85 µg h−1 cm−2. They screened the activity of a series of catalysts with different metals (Ag, Bi, Ir, Pt, Pd, Rh, Ru, Au) incorporated in 0.1 M phosphate buffer solution (PBS) with pH 7, containing 500 ppm NO3− under the applied potential of −0.4 V vs. RHE and found that Cu incorporated in PTCDA exhibited the maximum of total FE of 83.5% (NO3− → NO2−/NH3) after one hour of reaction. They rationalised the better performance of Cu–PTCDA by the effective charge transfer interaction between Cu and NO3−.

Defect and microenvironment engineering offer powerful routes to tune local electronic structures, optimise adsorption energies, and suppress competing reactions in ENRA. Amorphization, vacancy formation, and lattice strain have collectively demonstrated significant improvements in selectivity and activity. However, achieving precise control over defect concentration and maintaining stability under reaction conditions remains challenging. Future efforts should focus on controlled defect introduction to clarify structure-function relationships and guide the rational design of robust ENRA catalysts.

Alloy-based catalysts

Recent studies have demonstrated encouraging progress in the eNO3RR using catalysts composed of monometallic elements such as Ir, Pt, Rh, Ru, Pd, Cu, Ni, Ag, and Au22,120. Despite these advances, a major challenge remains: developing cost-effective catalysts without compromising (ideally enhancing) catalytic activity. Alloying of metals introduces heterogeneity between and within the composing elements, modifying charge distribution, which may give rise to active sites121. Additionally, the incorporation of secondary metals imparts intrinsic functionalities, including the suppression of nitrite generation and the promotion of sequential reaction pathways, thereby contributing to enhanced electrochemical performance of the catalyst62,122,123. Therefore, researchers have focused on alloying metals, particularly with Cu, due to its low cost and ease of fabrication for eNO3RR to ammonia. Cu has been successfully alloyed with Ti124, Fe125, and Pd126, resulting in significantly improved eNO3RR. For example, incorporating Pd atoms into Cu to form a Pd-Cu nanoalloy suppresses the HER and enhances proton transfer to NO3‒ species, thereby boosting eNO3RR activity126. The Pd-Cu catalyst exhibited a sixfold increase in catalytic activity compared to pristine Cu or Pd alone. Wang et al.62 developed Cu-Ni alloy-based catalyst, which showed sixfold higher activity towards eNO3RR compared to pure Cu-based one at 0 V (vs. RHE). They prepared Cu-Ni catalysts varying Cu-to-Ni ratios as 30:70, 50:50, and 80:20 by electrodepositing on both polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) membranes and rotating disk electrodes. Cu50Ni50/PTFE exhibited a 99 ± 1% FE for NH3 with 50 mV lower overpotential than Cu/PTFE in similar conditions. Alloying with Ni helped to achieve relatively higher FE at lower NO3– concentrations (≤10 mM) with a lower overpotential value. Through DFT studies, they validated that the introduction of Ni atoms upshifted the d-band centre of Cu towards the Fermi level, and this feature enhanced the intermediate adsorption energies on the Cu-Ni surface, resulting in lower overpotential and enhanced activity. The incorporation of Fe heteroatoms into Cu-based catalysts could further significantly boost the catalytic activity. Wang et al.127 fabricated a unique CuFe catalyst by strategically doping Fe into Cu to form a metasequoia-like nanocrystal structure for efficient eNO3RR in neutral media. They fabricated three different catalysts through electrodeposition by varying the weight percentage ratio of Fe and Cu with stoichiometries Cu49Fe1, Cu99Fe1, and Cu19Fe1. Among these three, Cu49Fe1 exhibited the best performance, showing 86.8% selectivity towards NH3 with 94.5% FE, and retained its optimum activity after four continuous cycles, proving its stability. The incorporation of Fe induced a negative shift in the Cu 2p3/2 and Cu 2p1/2 binding energies, suggesting a shift of the Cu 3d band toward a deeper energy level, facilitating the adsorption of reactant and intermediate species and favouring higher catalytic performances.

Gao et al.122 alloyed Cu with Ru to construct reduced graphene oxide supported Ru-Cu alloyed catalysts, RuxCuy/rGO, for ENRA. Among various Ru/Cu ratios, Ru1Cu10/rGO showed superior activity with an NH3 yield rate of 190 ± 7 mmol gcat−1 h−1 and FE of 92% at −0.15 V vs. RHE. The high activity of Ru1Cu10/rGO arises from the synergistic interaction between Ru and Cu through a relay catalysis mechanism. In this system, Cu primarily facilitates the reduction of NO3⁻ to NO2⁻, while Ru efficiently catalyses the subsequent reduction of NO2⁻ to NH3. Furthermore, alloying Ru with Cu modulates the d-band centre of the catalyst, thereby optimising the adsorption energies of the reactant NO3⁻ and the reaction intermediate NO2⁻, enhancing ammonia production.

Among the bimetallic systems, Cu-Co alloys are among the most widely investigated catalysts for eNO3RR128,129. He et al.130 proposed that the superior performance of CuCo alloys can also be explained by a tandem catalysis pathway. In this case, Cu serves as the active site for NO3⁻ adsorption and reduction to NO2⁻, whereas Co exhibits high selectivity for the subsequent conversion of NO2⁻ to NH3. Building on this concept, Fang et al.31 demonstrated a CuCo bimetallic nanosheet catalyst with remarkable performance, achieving nearly 100% FE at 0.2 V vs. RHE with a maximum yield rate of 960 mmol gcat−1 h−1 and sustaining an industrially relevant current density of 1035 mA cm−2. This represents a record-breaking benchmark for eNO3RR to date. The incorporation of Co into Cu not only accelerated electron transfer but also facilitated efficient delivery of electrons and protons to adjacent Cu sites, thereby improving nitrate utilisation to yield ammonia.

Alloy engineering effectively combines the strengths of different metals, offering tunable electronic structures and synergistic active sites that enhance both activity and selectivity in ENRA. Tandem mechanisms, where each metal facilitates a distinct reaction step, have proven particularly advantageous for improving nitrate utilization. However, understanding the precise nature of these synergistic sites and ensuring alloy stability under operating conditions remain ongoing challenges131. Future studies should integrate in-situ spectroscopic techniques with theoretical modelling to elucidate dynamic interactions and guide the rational design of durable alloy-based ENRA catalysts.

Metal-free catalyst

Owing to the complex synthesis routes of metal-based catalysts132,133,134,135, which elevate processing costs and risk metal leaching into treated water, non-metallic carbon materials have emerged as attractive alternatives. Huang et al. reported amorphous graphene synthesised by laser irradiation shows exceptional FE (≈100%)136. The oxidized laser-induced graphene (LIG) and oxidised LIG (ox-LIG) both outperformed reduced graphene oxide (rGO) in nitrate reduction. DFT calculations revealed that their amorphous structures lowered energy barriers for key intermediates (*NO2OH, *NO, *NOH) and enabled flexible stabilisation of adsorbed species. Notably, hydrogen bonding in ox-LIG further promoted intermediate stabilisation and accelerated reaction kinetics, leading to the highest eNO3RR activity. Huang et al. developed polymeric graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) catalysts with controllable nitrogen vacancy (NV) concentrations for efficient ENRA137. The optimised catalyst achieved exceptional ammonia selectivity (69.78%) and FE (89.96%) at −1.6 V vs SCE. Theoretical calculations showed that introducing NVs generates new electronic states near the Fermi level, enhancing conductivity and facilitating nitrate adsorption, activation, and dissociation. Moreover, an optimal NV concentration effectively modulates the adsorption energies of key intermediates (*NO, *NOH, *NH2), thereby accelerating the overall reduction process. This highlights defect engineering as an effective strategy for enhancing metal-free eNO3RR. Similarly, Fan et al. demonstrated that intrinsic structural defects in carbon nanotubes (CNTs) play a decisive role in boosting catalytic activity by increasing the adsorption energies of intermediates such as *NO2 and *NO138. These findings underscore the central importance of defect sites as active centres in carbon-based catalysts. Expanding this design principle, Li et al. synthesised a series of N-doped carbon catalysts derived from polyaniline hydrogels, systematically tuning the graphitic-N content to optimise nitrate reduction performance65. The catalyst with the highest graphitic-N content achieved an impressive NH3 yield rate of 1.33 mg h‒1 cm‒2 and a FE of 95%. Mechanistic analysis revealed that the strong adsorption of NO3– and the balanced hydrogen adsorption on graphitic-N sites, together facilitate the enhanced eNO3RR performance. Furthermore, Li et al. reported a metal-free porous fluorine-doped carbon (FC) catalyst for ENRA139. Fluorine doping perturbed the carbon’s electronic structure, inducing positively charged sites that favoured nitrate adsorption while effectively suppressing the competing HER. Consequently, the FC electrocatalyst achieved a FE of 20% and an ammonia yield rate of 23.8 mmol h‒1 gcat‒1 in acidic media, underscoring the promise of heteroatom doping in regulating surface charge and catalytic selectivity. In summary, these studies collectively demonstrate that structural and electronic modulation via defect creation, heteroatom doping, or amorphization can significantly enhance the activity, selectivity, and stability of metal-free carbon-based catalysts for eNO3RR. Such design strategies not only advance our understanding of active site chemistry in carbon materials but also pave the way toward sustainable, scalable, and environmentally benign ammonia synthesis routes beyond metal-dependent systems.

Conclusions and outlook