Abstract

There has been longstanding interest in the evolution of positive and negative relationships among countries. An interdisciplinary field of study, Structural Balance Theory, has developed on the dynamics of such appraisal systems. However, the advancement of research in the field has been impeded by the lack of longitudinal empirical data on large-scale networks. We construct the networks of international amicable and hostile relations occurring in specific time-periods in order to study the global evolution of the network of such international appraisals. Here we present an empirical evidence on the alignment of Structural Balance Theory with the evolution of the structure of this network, and a model of the probabilistic micro-dynamics of the alterations of international appraisals during the period 1995-2018. Also remarkably, we find that the trajectory of the Frobenius norm of sequential transition probabilities, which govern the evolution of international appraisals among nations, dramatically stabilizes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Networks of relationships such as like/dislike, trust/distrust, and praise/blame among individuals or collective actors may alter over time. The investigation of the topology of such signed appraisal networks, their evolution over time, and the development of models of their evolution have attracted sustained interdisciplinary interest. The conducted work posits that changes in the structure of appraisal networks are based on tensions generated by particular configurations of appraisals1 that violate transitivity (a friend of a friend is a friend), and perhaps other such rules (an enemy of an enemy is a friend, a friend of an enemy is an enemy, an enemy of a friend is an enemy). Appraisal networks may arise in small groups of individuals, in communities, or in very large-scale networks composed of collective actors that are organizations or nations with alliances and animosities.

In this paper, we investigate large-scale appraisal networks of collective actors where nodes represent nations, states, or regions of a country2,3,4,5,6,7,8. The motivations for exploiting such data include an understanding of the origins of war, the formation of alliances, and the balance of powers. Similarly motivated research includes2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Some of this research on international appraisals has been guided by a network science theory of structural balance1,9 in which signed networks evolve toward either a network of all-positive appraisals or a network composed of two components of actors with all-positive within-component appraisals and all negative between-component appraisals. Gellman et al.10 used structural balance theory to analyze the origins of World War I, and Antal et al.11 similarly used balance theory to explore the evolution of major changes among the protagonists prior to World War I during the period 1872–1907. Moore12 used balance theory to analyze the conflict over Bangladesh’s separation from Pakistan in 1972. Harary et al.5 also analyzed international relations among nations and different states of equilibrium and disequilibrium, using structural balance theory for the crisis in the Middle East in 1956. Harary et al.5 showed how ten countries, after each international shock, sought a new equilibrium alignment consistent with what balance theory predicts.

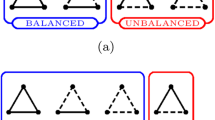

Structural balance theory has deep roots in sociology13 and social psychology1. Its applications include research on consumer-branding14, sports15, virtual worlds16, and social animals17. It posits that networks of positive or negative interpersonal appraisals evolve towards stable topologies1,9,18,19,20. The formal development of structural balance theory was set in motion with Cartwright and Harary’s9 definition of attractive and repulsive configurations. Their approach, which has become the standard model of structural balance, assumes a complete appraisal network in which all individuals have either a positive or negative appraisal of any other individual in the network. Thus, any three individuals’ interpersonal appraisals of one another must be 1 of the 16 configurations, some of which are posited to generate tensions that trigger a structural change. Notably, the classical structural balance theory model, which satisfies Cartwright and Harary’s criterion of structural balance, permits only 2 of the 16 feasible types. On this basis, a group’s network topology must be either a complete network of all-positive appraisal or a network partitioned into two antagonistic subgroups with no negative within-group appraisals and all negative between-group appraisal. The theory asserts that a network of positive and negative interpersonal relations evolves towards either a cohesive group or to a partition into two antagonistic subgroups21,22.

Despite numerous theoretical advancements and empirical studies on balance theory, the dynamic predictions of network state changes have rarely been tested with empirical investigations of longitudinal data16,23. There have been a large number of empirical studies on static networks24,25,26. Longitudinal studies have been limited to small populations of actors and to a small number of temporal states of the network2,27. In contrast, this study presents results on the most extensive set of longitudinal data yet assembled that allows research on the question of whether the evolution of appraisal networks is mainly driven by reductions of intransitive relations.

To tackle those shortcomings in the literature, we use Integrated Crisis Early Warning System (ICEWS) dataset, which is a comprehensive, automated, and validated system to monitor national, sub-national, and internal crises28. Its event data are publicly available and consists of coded interactions between socio-political actors (i.e., friendly or hostile actions between individuals, groups, sectors, and nation-states). Geographical–temporal metadata are extracted and associated with the relevant events within a news article. The data structure is a list of events. Every event has an occurrence date, a source actor, and a target actor. Every event is also annotated with a value in the [−10, +10] interval that indicates the orientation of the source to the target actor: −10 (completely offensive) to +10 (completely supportive). For instance, the news event “Japan said on Tuesday it had halted economic aid to Yugoslavia in line with Western efforts to end the fighting there” is coded as a directed edge from Japan to Yugoslavia with weight −5.6, which is calculated based on the content of the news and the type of event (which in this case was “reduce or stop economic assistance”). Generally, the actors have political positions in a particular country, such as government administration, military, police, and so on. In our analysis, we consider every country as a node and focus our analysis on international events in which the source and target nodes belong to different countries.

In the span of 23+ years from September 1, 1995 to September 30, 2018, the ICEWS data include 250 countries and 8,073,921 international events, each of which are positive or negative appraisals generated from a source country to some other target country. Each appraisal is a value in the interval [−10, +10] that indicates the orientation of the source to the target actor in a news event that occurred at a particular time: −10 (completely offensive) to +10 (completely supportive). The event data present positive, negative, and null international edges. The null edges are either a source-target news event that cannot be given a sign or an indicator that no source-target news event has been published. Precisely, there are 5,974,283 positive international edges (74%), 1,333,646 negative international edges (17%), and null instances of 765,992 neutral edges (with weight zero) (9%). In the ICEWS data, null relations appear when there are neither amicable nor hostile events between two countries. While it may be assumed that all countries are aware of each other’s existence, such awareness need not be coupled with an amicable or hostile relation.

Unlike classical balance theory’s prediction9, our empirical evidence does not support the prediction that a network of friends and enemies must evolve either to a network of all friends or to a network of composed two antagonistic components of actors with all-positive within-component appraisals and all negative between-component appraisals. Instead, the evidence supports the conclusion that the evolution of appraisals is mainly driven by reductions of intransitive relations among actors, which allow the emergence of complex network topologies with more than two mutually antagonistic sets of countries and hierarchically structured positive relations between countries29. Intransitive relations occur when there is evidence of a positive chain of international relations \(i\mathop{\longrightarrow }\limits^{+}k\mathop{\longrightarrow }\limits^{+}j\) and evidence of a negative \(i\mathop{\longrightarrow }\limits^{-}j\) relation. Such intransitive relations are assumed to be sources of international tensions that lead to transformations of positive relations to negative relations, and vice versa.

Furthermore, the empirical evidence does not support balance theory’s assumption that every actor has either a positive or a negative orientation to every other actor, and a line of research has developed that relaxes this assumption4,9,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. In large-scale networks, incomplete networks that include indifference relations are the rule. In this study, to the best of our knowledge, for the first time in a longitudinal setting, we are able to address three important limitations of the line of research on the evolution of international appraisals have has been motivated by structural balance theory. These data provide a unique opportunity to (i) construct networks of international amicable and hostile relations among nation-states that occur in specific time periods and (ii) investigate the global evolution of the network of such international appraisals over a lengthy span of time.

Our contributions in this study are as follows. In this article, we advance the line of research on the evolution of the network of amicable and hostile relations among countries, and also the basic science on structural balance theory. To the best of our knowledge, this article reports empirical findings from the largest longitudinal data yet assembled on structural balance theory. First, we address the existing lacuna on balance theory dynamics in large-scale networks that include null (indifference) relations. In networks that include large numbers of null relations, we found startling evidence of changes in international relations that are predominately restricted to only ten types of configurations in the possible set of 138 configurations of null, positive, or negative relations among any three countries. Second, we find surprising evidence that does not comport with balance theory’s prediction of a general tendency toward configurations of international relations that do not violate the theory’s assumptions. Instead, we find a trajectory that involves a short period of increasing numbers of violations of balance theory’s expectations, as indifference relations convert to negative or positive relations, followed by a longer trajectory that involves decreasing numbers of violations of transitive relations. This is an artifact of the dataset from the year 1995 to 2006 as due to increasing relationships among countries, the number of positive ties increases and therefore temporarily the number of intransitive triads increases. However, by investigating the Markov transition matrices of triads during the entire course of this evolution, we found that balanced triads are likely to stay balanced and those unbalanced triads are likely to transition to balanced ones. Third, to the best of our knowledge, we introduce a novel convex optimization model with a convergence guarantee for quantitatively estimating time-varying Markov chains of the transitions of the structure of international relations. Empirical Markov transition matrices show diminishing variability over our longitudinal data and emergent dynamic stability. Fourth, we conclude with evidence suggesting that the evolution of the network structure toward dynamic stability is subject to disturbances that appear to be related to disruptive international events and changes in the global economy. This finding provides a empirical support on a longitudinal setting for earlier research regarding the effect of global trades on international conflicts6.

Results and discussion

Empirical dynamic networks

To investigate the evolution of the international appraisals, these data are disaggregated into time periods. Each time period is associated with the subset of published events that occurred during the period. Each network comprises 62,250 (2502–250) directed positive, negative, and null edges among the 250 countries. A particular source-target ordered pair of countries may be associated with multiple events during a particular time period, and we take the sign of the summed value of these multiple events as the measure of the orientation of the source to the target. Hence, for a 3-month period, we have 101 snapshots of signed and directed networks among countries. We attend to different definitions of period length as a check on the robustness of our findings.

We found that the network structures are in the class of classical core-periphery (also called center-periphery) structures37,38. Such structures of n nodes are composed of one strong component of k nodes (the core) in which one or more paths of positive appraisals exits from every member of the core to every other member of the core. The remaining set of n − k nodes (the periphery) is composed of nodes, each of which have at least one positive appraisal to a node (or nodes) in the core. We found, in the first period of the data, that there are exactly 111 countries in the core and 23 countries in the periphery. These peripheral countries were Afghanistan, Angola, Guinea, Haiti, Sierra Leone, Zimbabwe, Bolivia, Paraguay, Rwanda, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Congo, Grenada, Guatemala, Guyana, Kuwait, Malawi, Mozambique, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Panama, Sudan, and Timor-Leste. We found that over time (in ~4 years), all of the first period peripheral countries moved into the core. That is, the size of the core grew to n = 134 and was maintained as a single strong component of 134 nodes. The remaining 116 countries do not exist in all network periods. Thus, we focus on the network dynamics of these 134 countries in our analysis. Using quarterly periods, the percentage of positive ties in the core increases from 4 to 18%, and the percentage of negative ties increases from 1 to 4%. This trend is shown in Fig. 1a.

This figure presents the dynamics of Integrated Crisis Early Warning System (ICEWS) network over time. a Proportion of positive and negative dyads (edges) over time in the strongly connected component. b Proportion of balanced triads over 23+ years. The three lines represent different subsets of Heider axioms as structural balance criteria in which they all show a similar trend. Triads are counted in networks built by aggregating 3 months of news articles. We found that changing the period length to monthly, biweekly, and weekly does not change the trend in this figure. c Average proportion of triads over 23+ years. Error bars correspond to one standard deviation and are computed using n = 103 network snapshots of quarters. d The set of ten operative triads (most frequent triads out of 138 possible ones).

This theory predicts an evolution of the structure of signed networks toward a state in which all violations are eliminated. In this theory, triads—subsets of three nodes—are considered the building blocks of relationships. Every possible triad of three countries among the core countries (134 countries) involves six edges. Classical structural balance theory assumes the absence of null edges, as every edge can be only positive or negative. In this case, there are 16 possible type of triads21,23,36,39,40. As large networks are rarely fully connected, in this paper, we consider a generalization of structural balance theory in which each edge is either positive, negative, or null. We call it sparse structural balance theory. In this model since null arcs are allowed, there are 138 possible types of triads. Supplementary Methods describe how triads were classified as balanced or unbalanced and Supplementary Fig. 2 shows a total of 138 possible triads named t1 to t138. The underlying idea behind this generalization is that at any given time if an edge has not been existed until now, it means there exists no social tension between those two nodes and that edge should not be considered as a violation by the balance theory axioms. To follow a tremendous literature on structural balance theory, we extend it on sparse networks using three existing models: classical9, clustering18, and transitivity19 (from least to most general, respectively). Each model permits different triad set to be considered structurally balanced. The extension of these models is formally defined in “Methods.” Unlike the past research in sparse balance theory41,42, our study is more general, concise, and uses a set of more detailed and longitudinal real-world datasets.

Remarkably, we found that 91% of the 392,084 observed triads in 23+ years are concentrated on only ten triad types (out of 138). Figure 1d displays this operative set of triad types (most frequent triads). The types 6, 8, and 9 include one or more violations of transitivity, and the others do not. Figure 1c shows the average distribution of operative triads over time and Fig. 1b depicts the temporal trajectory of the percentage of transitive triads. It is evident that structural balance does not always increase. Our finding based on Fig. 1b is that after a decrease of structural balance during the first periods, the network’s trend is toward greater balance since 2006 onward. The main basis of the initial decline are conversions of null relations to positive relations and the associated proliferation of intransitive triad 9 configurations. Over time, many of these violations of transitivity are then resolved by conversions to triads that do not violate transitivity (triads 1, 4, or 10). This increase in the number of triads 6, 8, and 9 before 2006 is not due to any particular major global occurrences, but in fact is the inherent property of inception of many connections among countries around this era. After analyzing the Markov transition matrices of all these triads, we found that there is a high probability for transitioning from all these three not balanced triads to the balanced triads consistently using any period length. This shows that staying in these not balanced triads is temporary. Also, looking at the distribution of triads (Fig. 1c), we see only ~8% of triads (summation of the volume of triads 6, 8, and 9) to be not balanced over the course of more than two decades. The evidence for this result is highlighted in our Markov chain analysis to which we now turn.

Markov model on dynamic networks

Here, we present a Markov model of the dynamical system of the temporal transitions of the networks’ triads that is not restricted to the operative set of triad types. This model provides a deeper image of the probabilistic micro-dynamics of the alterations of international appraisals during the 1995–2018 span of the available data. Figure 2 shows the average probability transition matrix of the 138 possible triad types from 103 networks aggregated over a 3-month period (seasonally). Interestingly, most of the probabilities in this matrix are very close to zero and the dynamics of the system can be described only by a few states. For the sake of visualization, we can focus on the operative set of ten triad types (described in Fig. 1e) and we show their transition probabilities in Fig. 3a. The probability transition matrix is robust with respect to the choice of period. In Fig. 3, each panel shows the transition matrix for period lengths: (a) seasonally, (b) monthly, (c) biweekly, and (d) weekly. The probability transition matrices look very similar. Quantitatively, the Pearson’s correlation between the flatten format of transition matrix in (a) with (b), (a) with (c), and (a) with (d) is 0.99, 0.98, and 0.86, respectively, where all are statistically significant (p < 0.05). Based on these transition matrices, one can see the triads 1, 4, 9, and 10 have large self-transition probabilities (high probability of transitioning from 1 to 1) and, thus, are most likely to persist. More precisely, Fig. 3e shows the stationary distribution of the Markov process. The summation of balanced triads in the stationary distribution is >0.85. It appears that regardless of the definition of the period, the Markov model predicts our empirical finding of a network evolution toward structural balance.

Average probability transition matrix in the Integrated Crisis Early Warning System (ICEWS) dataset. The average is computed from 101 transition matrices between states that are the 138 possible sparse triads (Supplementary Fig. 2 depicts all these triads). The transition matrix is row-stochastic and its elements fall into (0, 1]. This figure shows that there exist only a small number of triad transitions as most elements of this matrix are close to zero. It also depicts that most transitions only happen toward a few of triads. The transition matrix for the top ten most frequent triads is further analyzed in Fig. 3.

Average probability transition matrix only for the core triads 1 in the Integrated Crisis Early Warning System (ICEWS) dataset by aggregating dynamic networks of a seasonally, b monthly, c biweekly, and d weekly period. The transition matrix is row-stochastic and its elements fall into (0, 1]. There are 138 possible triads; only the sub-matrix of the 10 operative triads is shown (given in Fig. 1e). e shows the probability of stationary distribution of the transition matrices, with the different aforementioned periods. The stationary distribution shows the state of the system under the condition that the Markov model persists. It appears that the probability transition matrix and stationary distribution are robust with respect to the choice of period length.

Time-varying Markov model on dynamic networks

Our results show that the probability of transitions to and remaining in balanced states are statistically significant in every period over the 23+ year data span. This motivates us to apply a more holistic and time-varying Markov model in which the transition matrix can smoothly change and is learned via a convex optimization scheme (see “Methods” for details). Figure 4 describes the analysis pipeline of this model. Our Fig. 5 results further support the conclusion that structural balance drives the dynamics of the system. All unbalanced triads have an estimated high mean probability and small standard deviation on transitions into balanced triads, and the balanced triads have an estimated high mean probability and small standard deviation of remaining balanced. Note the distinctive separation of the transition probabilities.

Estimation of transition probability matrices between balanced and unbalanced triads over a sequence of time periods. This figure illustrates the preprocessing steps, the optimization problem, and the results. Step 1: for all time periods t from 1 to T − 1 (where T is the maximum number of periods in that dataset), each edge is labeled using aggregated majority in that period as positive (+) or negative (−). Step 2: we compute the proportion of triads in every period and estimate the transition matrix at time t as the unknown matrix that multiplied by the vector of proportion of triads at period t gives the corresponding vector at period t + 1. Step 3: we estimate all transition matrices together using a time-varying Markov model. This step ensures that the results provide a holistic view of the available longitudinal data. Step 4: we visualize the probability of transition from balanced and unbalanced triads in time-varying estimated transition matrices. By allowing null ties, there are 138 types of triads. Pt represents the unknown transition matrix at time t and \(\hat{{P}_{t}}\) represents the empirically estimated transition matrix at time t, and \({\widetilde{P}}_{t}\) represents the time-varying estimated transition matrix at time t. The four quadrants of \(\hat{{P}_{t}}\) show the average estimated transition probabilities (see “Methods” for details). The result of this experiment is shown in Fig. 5.

Estimated transition probability for a transitivity-, b clustering-, and c classical-balanced and -unbalanced triads in Integrated Crisis Early Warning System (ICEWS) dataset (the pipeline is described in Fig. 4). The Y-axis indicates the kind of transition and the X-axis shows the estimated probability (computed by solving Eq. (7)), the box is the interquartile range of the probability distribution, the orange line is the median and green dot is the average of the distribution, and the whisker shows minimum and maximum of the range of the distribution. This figure shows that the probability of transitions from unbalanced triads to balanced ones is significantly higher than the opposite transitions. Also, the probability of remaining balanced is more likely than the probability of remaining unbalanced. These findings hold regardless of the definition of balance. Box plots are computed using n = 103 network snapshots of quarters. Supplementary Fig. 1 extends this analysis to two Bitcoin datasets showing that movement toward balance is not a peculiarity of the ICEWS dataset.

Applying this experiment on other datasets, we posit this result not only holds in our focal network of international relations, but also in two longitudinal datasets on financial Bitcoin trust networks43,44. Due to the focus of this paper and lack of space, we do not include those figures in the main paper. Supplementary Results provide details about the two Bitcoin datasets. Particularly, Supplementary Table 1 includes statistics regarding all datasets including the Bitcoin trust networks and Supplementary Fig. 1 shows a set of results similar to Fig. 5 applied on all datasets. Although the results show that international and financial networks are very different, our findings on the transition toward balance generalize across all three datasets. Therefore, it appears that transitions toward balance are ubiquitous (i) regardless of the definition of balance, (ii) regardless of the setting (international news networks or financial networks), and (iii) regardless of the type of actor (individuals or countries).

Qualitative relation with exogenous shocks

The transition matrices are stable over time, as measured by the Frobenius norm difference of consecutive matrices (Fig. 6). Interestingly, the Frobenius norm of transition matrices declines smoothly over time. We call this phenomenon, the stability of the dynamics. This finding is aligned with the fact that the number of wars per pair of countries in the past 50 years was roughly a tenth as high as it was from 1820 to 1949. Figure 6a suggests that the disruptions to this trend are associated with important shocks such as the September 11, 2001 attacks (9/11).

a The Frobenius norm difference of consecutive empirical transition matrices (blue line) becomes stable over time corresponding to the Markov chain of triads becoming stable over time. Most global exogenous events (red dots) such as wars trigger disturbances in the dynamics of relationships. b Comparison of the Frobenius norm difference of consecutive empirical transition matrices (full blue line), versus international trades in % of each country’s GDP (dashed red line) highlights a reverse relation between changes in the system and international trades. We find Frobenius norm difference of consecutive empirical transition matrices and international trades are statistically and negatively correlated (Pearson’ coefficients r = − 0.88 and p < 1e − 07). Moreover, we found that the international trades statistically Granger cause (49) the stability of relationships among countries (p < 1e − 03). This result means the more international trades existed, the less changes in the relationships among countries have happened. Aligned with this finding, earlier research (6, 45–48) also claimed increased trades have decreased countries’ incentive to attack each other, leading to a stable and network of alliances. Statistical significance is computed using n = 23 years of global trades and Frobenius norm difference of transition matrices.

Quantitative relation with international trade activity

In addition, inspired by previous research6,45,46,47,48, using the data on international trades among nations since 1995, in Fig. 6b, we find a statistically significant correlation between the Frobenius norm difference of consecutive matrices and the inverse of global trades. World trade data show the global trades among all countries in the world as of the percentage of each countries’ GDP, which is extracted from The World Bank national accounts data (see “Data availability” for details). The stability of dynamics and global trades are correlated in past 23+ years (Pearson’s correlation coefficient of 0.88 (p < 1e − 07)). Figure 6 shows that as relationships among countries have become stable over the years, the volume of trades has been increased.

Moreover, our causality test shows that the more global trades there are, the more stable the relational dynamics become and vice versa over the course of two decades. Granger causality test49 shows a statistically significant effect of global trades on the stability of the dynamics (p < 1e − 03), and also shows a feedback effect (p < 1e − 02). The causality tests are found to be statistically significant using both F test and χ2 test with #lags = 1.

This result simply means as the relations among countries become more stable, they are more willing to trade for economical benefits, and on the other hand, when they internationally trade with one another, they are willing to have a stable relationship with one another. In this study, stability is captured with Markov transition matrices of triads over the course of two decades. This finding comports with the seminal study by Jackson and Nei6 and its finding on stabilizing the international conflicts by the decrease of the number of wars among nations as the same rate as the increase in global trades.

Conclusion

Balance theory has triggered a literature of efforts to specify the mechanisms that alter interpersonal appraisal networks1,9,50 towards states of structural balance. This theory is also associated with research on international relations. However, despite the need for longitudinal data to recover the underlying dynamics of balance theory, such investigations have been rare. We have leveraged an extensive longitudinal dataset to advance the research on the evolution of the network of global international relations, and the basic science on balance theory. We find consistently high probabilities of transition toward and remaining in balanced triads and not vice versa. We believe that balance theory’s prediction of a structural evolution toward balanced states is sound. Also, we found that the network dynamics of international relations over the past 23+ years have been toward structural stability, consistent with balance theory expectations, with occasional shocks of large-scale international events on the trajectory of the global network.

Methods

Generalized structural balance

In order to give formal definitions of different versions of generalized balance theory, we start with Heider’s1,51 four axioms:

-

A1. Friend of a friend is a friend.

-

A2. Friend of an enemy is an enemy.

-

A3. Enemy of a friend is an enemy.

-

A4. Enemy of an enemy is a friend.

Classical balance theory assumes a fully connected network1,18,20,36. We generalize three definitions of balance, based on the above axioms, to networks with null edges. Assume eij represents a directed edge from node i to node j. The value of eij can have negative, positive, or zero (null) value. Out of 138 possible triads, 93 are transitive-balanced (67%), 44 are cluster-balanced (32%), and 24 are classical-balanced (17%). Remarkably, we find a large set of forbidden triad types are transitioning to a relatively small set of permissible triad types (Fig. 5). In balance theory literature, the concept of sparse balance theory has been addressed before as incomplete awareness32,52. The concept has been motivated by the empirical evidence that affective relations are signed but seldom complete—actors may be neutral toward each other or there may be null or unobserved edges. Cartwright and Harary9 define balanced cycles on networks with missing edges such that the only condition is cycles containing an even number of negative edges. In this work, we extend the analysis of networks with null edges to the general case of sparse triads. Table 1 provides formal definitions for balanced triads in sparse networks inspired from three aforementioned historical models. Assume every directed edge e has value ∈ {− 1, 0, + 1}. For every three distinct nodes i, j, and k, to be considered as a balanced triad, the following condition, for any permutation of the nodes, needs to hold.

Network extraction

Networks are extracted by aggregating edges in predetermined periods. If the period length is too short, we would not obtain sufficient information, while too long periods would decrease the granularity of the observations. We use 12 weeks (~1 quarter) as the period duration. Note, Fig. 3 shows that results based on transition matrices are robust with respect to the choice of period length. Consequently, for ICEWS dataset, we have 103 networks. For a given network, the appraisal between nodes i and j is determined by the sign of summed edge weights of all directed edges observed between them (edge (i, j)), during that time period, as described by

where A(tk) shows the adjacency matrix of directed and signed network at time at period tk.

Empirical Markov transition matrices

We use maximum-likelihood estimation for estimating empirical Markov transition matrices. Pt represents a Markov transition probability matrix from time t to t + 1. More precisely, for each consecutive observation period (t, t + 1), we compute Pij(t), the number of triads of type i that moved to type j from period t to t + 1. In fact, for every three nodes in the network, we found the corresponding triad type, at time t and time t + 1, say triad type i and triad type j, respectively. Then, increment the number of transitions happening from Pij(t) ← Pij(t) + 1. Thus, row i sums to Pi⋆(t), the number of triads of type i at time t, while P⋆j(t + 1) is the number of triads that have transitioned to type j at time t + 1. Using the transition matrix Pij(t + 1), the transition probabilities can be estimated to obtain the transition probability matrix. These quantities can be arranged in a matrix and normalized by the sum of every row. Therefore, we have row-stochastic transition matrix P, where each Pij(t) is conditional on i only, and not on prior states occupied by the triad. By the Markov property, they are identical for all triads, and they converge to a stationary probability distribution.

It is implicit in the evolution of structural balance that the triads share edges in a network and that might affect the estimating the empirical Markov transition probabilities. However, based on Markov property, the only requirement is that the next state only depends on the current state as we compute the transition probability matrix from two consecutive time periods. This phenomenon introduces additional structures in the transition matrix. As a consequence, some transitions can rarely happen as some entries of the transition matrix will be close to zero. We mitigate this potential dependency among triad transitions by applying smoothness, which also helps to estimate the correct transition matrix with fewer number of data points.

Estimating time-varying Markov transition matrices

Estimating Markov transition matrices via counting the observed transitions only takes into account the subsequent periods and therefore does not take advantage of any other similarity among transition matrices. The goal is to have a method that while keeping the Markov attribute of the system allows for transition matrices to transfer information based on the existing assumptions in the literature, such as applying smoothness to estimate a more accurate set of transition probability matrices. Hence, we use time-varying Markov chains to capture the most out of the observed transitions in the data. The length of the longitudinal data, in this study, entails having statistical sufficiency to apply a non-parametric convex method to accurately estimate the transition probability matrices directly from the data.

Model formulation

For a network At at time t, we count the occurrences of each of three nodes, and classify each into one of 138 possible triads. T represents the number of available time periods and there exists T networks.

There are m entities (triads in a dynamic network) that in parallel change states for T periods of time. As discussed before, there are 138 triad types. The empirical Markov probability transition matrix from time t − 1 to t, represented as \({\hat{{\bf{P}}}}_{t}\), is computed as follows:

where each \({\hat{{\bf{P}}}}_{t}\) is a 138 × 138 Markov transition matrix and there exist \({\hat{{\bf{P}}}}_{1},\ldots ,{\hat{{\bf{P}}}}_{T-1}\) as empirical transition matrices. m represents the number of possible sub-graphs of three. 1 shows indicator function, which in this equation depicts counting the number of transitions from time t − 1 to time t. \({S}_{t}^{(r)}\) shows the type of triad (state) of sub-graph r at time t. In Eq. (2), the numerator accounts for the number of transitions from triad type i to j, and the denominator captures the number of transitions from triad type i to any triads. Figure 3 shows the average empirical Markov transition matrices for a different choice of period length. Now, we formalize an optimization problem to account for potential error in each empirical transition matrix as being optimized to be close to the true underlying time-varying Markov transition matrix as

The algorithm considers these empirical transition matrices as the input, and estimates all latent transition matrices, simultaneously. By definition, a Markov transition matrix, Pt: 138 × 138, should be ergodic, aperiodic, and irreducible. Simply put, in the considered Markov chain, it should be possible to be in any state and also should be possible to get to any state from any state. Thus, there are T probability Markov transition probability matrices and every Pt needs to satisfy

By definition, Markov transition probability matrices should be row-stochastic—every row is sum up to 1. That is,

Regarding the objective function, based on previous studies dealing with time-varying Markov chains53, we make an assumption that subsequent transition matrices are similar to each other; the changes happen smoothly.

Optimization problem

To estimate all unknown transition matrices simultaneously (T − 1 matrices of size 138 × 138), we setup an appropriate optimization problem; we shall solve the optimization problem using convex optimization methods:

where function ψ represents regularization terms for time-varying transition matrices estimation. This function is defined as ψ(X) = λ1∥X∥1 + λ2∥X∥2 for any matrix X ∈ R138 × 138. These terms together penalize both the magnitude and number of changes in the Markov transition matrices between periods. In this equation, Pt: t = 1, …, T − 1 are the variables to be estimated using convex optimization, \({\hat{{\bf{P}}}}_{t}:t=1,\ldots T\) are the empirically estimated transition matrices using counting each triad’s transitions, and \({\widetilde{{\bf{P}}}}_{t}:t=1,\ldots ,T-1\) are the estimated transition matrices. The values of \({\widetilde{{\bf{P}}}}_{t}\) are shown in Fig. 5. More precisely, using function ψ in Eq. (7), we apply two forms of smoothness on subsequent Markov transition matrices: l2-norm (Frobenius norm), also called group lasso that enforces a small amount of change in transition matrices, and l1-norm, also called fused lasso that induces a sparse solution with respect to the changes in matrices. In optimization literature, this criterion is called sparse group lasso54. Together, they encourage subsequent Markov transition matrices to only deviate from each other with small values and in only a few cells.

This formulation allows for learning a separate model for each transition between time periods while inferring information globally across all periods. Non-parametric estimation of all transition matrices together via an optimization problem decreases the chance of overfitting. This method also allows for finer time windows than otherwise, and provides a better inference granularity in time. Consequently, even with few observations of the data, we end up with an accurate estimation for time-varying transition matrices. Algorithm 1 illustrates the steps for estimating the time-varying Markov chains.

The problem in Eq. (7) is convex. The reason is that the objective function is a summation of two norms that are convex, all of the inequality constraints are convex, and all equality constraints are affine. Therefore, the problem is convex55, it has a globally optimal solution, and we solve this equation by a convex optimization solver, CVXPY56.

Model comparison

In order to test the predictability of the estimated transition matrices, we predict the unseen proportion of the unseen triads using the proposed algorithm as compared to competitive baseline methods. For instance, assume we have T periods. We hold out the proportion of triads at time T and train on periods of 1 up to T − 1 using Algorithm 1. Consequently, the estimated transition matrix for time T − 1 to T is multiplied with proportion at T − 1 to give us the predicted proportion at T. We apply one step-ahead forecast, for multiple times, in each time retraining the model up to the last held out time. To this end, we have a more descriptive picture of the prediction power of the proposed method. As the forecast metric, we compute root mean-squared error of the difference between the predicted proportion with the ground truth. Random prediction is neglected due to its significantly worse accuracy compared to other baselines. Consequently, we compare our forecast to a baseline of simply predicting the last time-step proportions versus an average of all preceding time-step proportions.

In this dataset, we modify the proposed model in Eq. (7) to apply the optimization only on a desired time window with length δ. This hyperparameter would be tuned to determine how many past transition matrices are used for optimizing the current time points. The reason is long-range interactions in the objective function could cause unwanted effects if the dynamics are changing so heavily over time. Especially, when we observe in Fig. 6 that the changes are dramatically decreasing over time. Using 2 years as the time window (δ = 8), we compare the proposed model using time-varying Markov model to the baselines in Fig. 7.

Root mean-squared error (RMSE) of different baseline algorithms and the proposed time-varying Markov model (dashed blue) in predicting unseen triad proportions in Integrated Crisis Early Warning System (ICEWS) dataset (the smaller RMSE the better). Average Proportion (dash-dotted orange) computes the average of each triad type proportion up to the current time. Last Proportion (solid green) assumes that the new proportion is exactly the last one, and due to the origin of being smooth, it is highly competitive. The proposed Time-invariant Markov (dotted red) chain method minimizes the RMSE, thus providing the most accurate proportion of triads. The results show that the proposed method almost for every year surpassed the baselines’ accuracy in forecasting the proportion of the triads.

Figure 7 depicts that the proposed algorithm outperforms the baselines and makes accurate forecasts of the proportion of triads in the subsequent time period in the ICEWS dataset. Baselines consist of predicting last proportion of triads (Last Proportion), average of previous proportions of triads (Average Proportion), and using previous Markov transition matrix without applying time-varying estimation to estimate the current proportion (Time-invariant Markov). The proposed time-varying Markov model clearly surpasses the baselines in almost every year forecast. We also apply on a validation set of the periods, to carefully tune the hyperparameters of Algorithm 1. In this study, we also set λ1 = 0.01 and λ2 = 0.005.

A future direction to improve the predictability of the model is to remove the Markov assumption in the modeling. We can let models find the best number of previous periods, which should be taken into account for predicting the proportion of triads. Recursive neural networks can model the non-Markovian aspect inherent in the data.

Data availability

We state that all relevant data are available from the authors. The data are publicly available as the so-called “Integrated Crisis Early Warning System (ICEWS) Dataverse” by Boschee et al.57 under https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/28075. The hyperlink also includes a document about the ICEWS event coding protocols.

The World Bank trade data (% of GDP) is also publicly available under https://data.worldbank.org/. The Bitcoin Alpha and OTC datasets are from Kumar et al.43.

Code availability

The source code is publicly available under https://github.com/omid55/dynamic_sparse_balance_theory. To further facilitate usage of the network data and eventually reproducibility of this work, we provide all preprocessed data and networks under https://github.com/omid55/dynamic_sparse_balance_theory/tree/master/preprocessed_data.

References

Heider, F. Attitudes and cognitive organization. J. Psychol. 21, 107–112 (1946).

Zheng, X., Zeng, D. & Wang, F.-Y. Social balance in signed networks. Inf. Syst. Front. 17, 1077–1095 (2015).

McDonald, H. B. & Rosecrance, R. Alliance and structural balance in the international system: a reinterpretation. J. Confl. Resolut. 29, 57–82 (1985).

Easley, D. & Kleinberg, J. Networks, Crowds, and Markets: Reasoning About a Highly Connected World (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010).

Harary, F. A structural analysis of the situation in the Middle East in 1956. J. Confl. Resolut. 5, 167–178 (1961).

Jackson, M. O. & Nei, S. Networks of military alliances, wars, and international trade. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 15277–15284 (2015).

Doreian, P. & Mrvar, A. Structural balance and signed international relations. J. Soc. Struct. 16, 1 (2015).

Belaza, A. M. et al. Statistical physics of balance theory. PLoS ONE 12, e0183696 (2017).

Cartwright, D. & Harary, F. Structural balance: a generalization of Heider’s theory. Psychol. Rev. 63, 277 (1956).

Gellman, P. The elusive explanation: balance of power theory and the origins of World War I. Rev. Int. Stud. 15, 155–182 (1989).

Antal, T., Krapivsky, P. L. & Redner, S. Social balance on networks: the dynamics of friendship and enmity. Phys. D 224, 130–136 (2006).

Moore, M. An international application of Heider’s balance theory. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 8, 401–405 (1978).

Simmel, G. Conflict and the Web of Group Affiliations (Trans. Wolff, K. & Bendix, R.) (Free Press, New York, 1955).

Woodside, A. G. Advancing means—end chains by incorporating Heider’s balance theory and Fournier’s consumer–brand relationship typology. Psychol. Mark. 21, 279–294 (2004).

Fink, J. S., Parker, H. M., Brett, M. & Higgins, J. Off-field behavior of athletes and team identification: using social identity theory and balance theory to explain fan reactions. J. Sport Manag. 23, 142–155 (2009).

Szell, M., Lambiotte, R. & Thurner, S. Multirelational organization of large-scale social networks in an online world. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 13636–13641 (2010).

Ilany, A., Barocas, A., Koren, L., Kam, M. & Geffen, E. Structural balance in the social networks of a wild mammal. Anim. Behav. 85, 1397–1405 (2013).

Davis, J. A. Clustering and structural balance in graphs. Hum. Relat. 20, 181–187 (1967).

Holland, P. W. & Leinhardt, S. Transitivity in structural models of small groups. Comp. Group Stud. 2, 107–124 (1971).

Johnsen, E. C. Network macrostructure models for the Davis–Leinhardt set of empirical sociomatrices. Soc. Netw. 7, 203–224 (1985).

Marvel, S. A., Kleinberg, J., Kleinberg, R. D. & Strogatz, S. H. Continuous-time model of structural balance. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 1771–1776 (2011).

Srinivasan, A. Local balancing influences global structure in social networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 1751–1752 (2011).

Askarisichani, O. et al. Structural balance emerges and explains performance in risky decision-making. Nat. Commun. 10, 1 (2019).

Leskovec, J., Huttenlocher, D. & Kleinberg, J. Predicting positive and negative links in online social networks. In Proc. 19th International Conference on World Wide Web, (eds Mynatt, E., Fitzpatrick, G., Hudson, S., Edwards, K. & Rodden, T.) 641–650 (ACM, 2010).

Newcomb, T. M. The prediction of interpersonal attraction. Am. Psychologist 11, 575 (1956).

Shahriari, M., Sichani, O. A., Gharibshah, J. & Jalili, M. Sign prediction in social networks based on users reputation and optimism. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 6, 91 (2016).

Lazer, D. et al. Computational social science. Science 323, 721–723 (2009).

Shilliday, A. & Lautenschlager, J. Data for a worldwide ICEWS and ongoing research. Adv. Des. Cross-Cultural Activities 455, 454–464 (2012).

Friedkin, N. E., Proskurnikov, A. V. & Bullo, F. Positive contagion and the macrostructures of generalized balance. Netw. Sci. 7, 445–458 (2019).

Harary, F. On the measurement of structural balance. Behav. Sci. 4, 316–323 (1959).

Abell, P. Structural balance in dynamic structures. Sociology 2, 333–352 (1968).

de Nooy, W. The sign of affection: Balance-theoretic models and incomplete signed digraphs. Soc. Netw. 21, 269–286 (1999).

Kunegis, J. et al. Spectral analysis of signed graphs for clustering, prediction and visualization. In Proceedings of the 2010 SIAM International Conference on Data Mining (eds Parthasarathy, S., Liu, B., Goethals, B., Pei, J. & Kamath, C.) 559–570 (2010).

Terzi, E. & Winkler, M. A spectral algorithm for computing social balance. In International Workshop on Algorithms and Models for the Web-Graph (Eds Frieze, A., Horn, P. & Pralat, P.) 1–13 (Springer, 2011).

Facchetti, G., Iacono, G. & Altafini, C. Computing global structural balance in large-scale signed social networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 20953–20958 (2011).

Rawlings, C. M. & Friedkin, N. E. The structural balance theory of sentiment networks: Elaboration and test. Am. J. Sociol. 123, 510–548 (2017).

Shils, E. et al. Center and Periphery (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1975).

Bourgeois, M. & Friedkin, N. E. The distant core: social solidarity, social distance and interpersonal ties in core–periphery structures. Soc. Netw. 23, 245–260 (2001).

Sørensen, A. B. & Hallinan, M. T. A stochastic model for change in group structure. Soc. Sci. Res. 5, 43–61 (1976).

Juszczyszyn, K., Musial, K. & Budka, M. Link prediction based on subgraph evolution in dynamic social networks. In 2011 IEEE Third International Conference on Privacy, Security, Risk and Trust and 2011 IEEE Third International Conference on Social Computing (eds Pentland, A. et al.) 27–34 (IEEE, 2011).

Belaza, A. M. et al. Social stability and extended social balance-quantifying the role of inactive links in social networks. Phys. A 518, 270–284 (2019).

Estrada, E. & Benzi, M. Walk-based measure of balance in signed networks: detecting lack of balance in social networks. Phys. Rev. E 90, 042802 (2014).

Kumar, S., Spezzano, F., Subrahmanian, V. & Faloutsos, C. Edge weight prediction in weighted signed networks. In IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (eds Baeza-Yates, R., Zhou, Z.-H., Bonchi, F. & Domingo-Ferrer, J.) 221–230 (2016).

Kumar, S. et al. Rev2: fraudulent user prediction in rating platforms. In Proc. ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining (eds Chang, Y., Zhai, C., Liu, Y. & Maarek, Y.) 333–341 (ACM, 2018).

Barbieri, K., Keshk, O. M. & Pollins, B. M. Trading data: evaluating our assumptions and coding rules. Conflict Manag. Peace Sci. 26, 471–491 (2009).

Martin, P., Mayer, T. & Thoenig, M. Make trade not war? Rev. Econ. Stud. 75, 865–900 (2008).

Oneal, J. R. & Russett, B. Assessing the liberal peace with alternative specifications: trade still reduces conflict. J. Peace Res. 36, 423–442 (1999).

Hegre, H., Oneal, J. R. & Russett, B. Trade does promote peace: new simultaneous estimates of the reciprocal effects of trade and conflict. J. Peace Res. 47, 763–774 (2010).

Granger, C. W. Causality, cointegration, and control. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 12, 551–559 (1988).

Friedkin, N. E. A formal theory of reflected appraisals in the evolution of power. Adm. Sci. Q. 56, 501–529 (2011).

Heider, F. The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations (Psychology Press, 2013).

Montgomery, J. D. Balance theory with incomplete awareness. J. Math. Sociol. 33, 69–96 (2009).

Chiba, T., Hino, H., Akaho, S. & Murata, N. Time-varying transition probability matrix estimation and its application to brand share analysis. PLoS ONE 12, e0169981 (2017).

Friedman, J., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. A note on the group lasso and a sparse group lasso. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/pdf/1001.0736 (2010).

Boyd, S. & Vandenberghe, L. Convex Optimization (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2004).

Diamond, S. & Boyd, S. CVXPY: a Python-embedded modeling language for convex optimization. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 17, 1–5 (2016).

Boschee, E. et al. ICEWS coded event data. Harvard Dataverse 12, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/28075 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by a UC Multicampus-National Lab Collaborative Research and Training (UC-NL-CRT) grant, titled “Political Conflict and Stability in Dynamic Networks,” under grant number LFR-18-547591, and by the US Army Research Laboratory and US Army Research Office under grant number W911NF-15-1-0577. We thank Prof. Yu-Xiang Wang for his instructive comments on the proposed optimization model and thank Haraldur Hallgrimsson for his comments on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.A. analyzed the data and implemented the methods. O.A. and N.E.F. led the study. F.B. and A.K.S. actively participated in the discussion and gave critical comments. All authors substantially contributed to the design of the analysis and the writing of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Askarisichani, O., Singh, A.K., Bullo, F. et al. The 1995-2018 global evolution of the network of amicable and hostile relations among nation-states. Commun Phys 3, 215 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-020-00478-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-020-00478-z

This article is cited by

-

Balance and fragmentation in societies with homophily and social balance

Scientific Reports (2021)