Abstract

Searching for topological superconductors with non-Abelian states has been attracting broad interest. The most commonly used recipe for building topological superconductors utilizes the proximity effect, which significantly limits the working temperature. Here, we propose a mechanism to attain topological superconductivity via forward phonon scatterings. Our crucial observation is that electron-phonon interactions with small momentum transfers favor spin-triplet Cooper pairing under an applied magnetic field. This process facilitates the formation of chiral topological superconductivity even without Rashba spin-orbit coupling. As a proof of concept, we propose an experimentally feasible heterostructure to systematically study the entangled relationship among forward-phonon scatterings, Rashba spin-orbit coupling, pairing symmetries, and the topological property of the superconducting state. This theory not only deepens our understanding of the superconductivity induced by the electron-phonon interaction but also sheds light on the critical role of the electron-phonon coupling in pursuing non-Abelian Majorana quasiparticles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Topological superconductors have been attracting broad interest due to the great potential application of non-Abelian states in fault-tolerant quantum computing1,2,3,4,5. Topological physics in superconductors can arise in an intrinsic or extrinsic manner6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. For example, unconventional superconductors with chiral p-wave Cooper pairing provide a promising platform to achieve intrinsic topological superconductivity in bulk systems25,26,27. Because unconventional superconductors are scarce in nature, recent research activities have been focused on extrinsic mechanisms using the superconducting proximity effect6,7,8,9,10,11,12,20. These extrinsic topological superconductors usually consist of a conventional superconducting substrate to supply pairing potential and a functional add-on layer with the spin-orbit coupling. Thanks to the development of epitaxial growth techniques, recent years have witnessed significant progress in extrinsic topological superconductors28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35, including Rashba nanowires30, ferromagnetic semiconductors36, and high-mobility two-dimensional (2D) electron gas37. However, superconductivity from the proximity effect is usually weaker than that from intrinsic interactions, significantly limiting the working temperature. Furthermore, the small superconducting gap of topological superconductors necessarily increases the vulnerability of its topological boundary modes (i.e., Majorana modes) to disorder38,39. Therefore, an interesting open question in this field is how to break the temperature barrier of artificial topological superconductor.

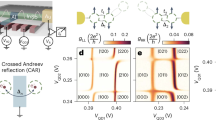

The main finding in this work is that forward electron-phonon (e-ph) scatterings tend to generate spin-triplet Cooper pairs in the presence of a magnetic field, which motivates us to propose a experimentally feasible platform to achieve high-temperature chiral topological superconductivity without using the superconducting proximity effect40. In our proposed protocol (see Fig. 1), phonons originate from the vibration of dipoles at the surface of the ferroelectric substrate coupled to the electrons in the add-on layer, generating intrinsic superconductivity. Previous studies on FeSe/STO showed that such interfacial e-ph interaction has a singularity at the Γ point and significantly enhances the superconducting transition temperature41,42,43,44,45,46,47. The novel effect of forward phonon scatterings could open a pathway to engineering high-temperature topological superconductivity. We demonstrate that the short-ranged forward phonon scattering can induce nonzero triplet pairing potentials and further significantly stabilize the triplet superconductivity against an applied magnetic field. This effect is independent of the Rashba spin-orbit coupling (RSOC)48 and allows us to fulfill the stringent topological superconductivity without RSOC.

a Schematic view of a 2D topological superconductor induced by an interfacial electron-phonon interaction. The magnetic field Bz is applied perpendicular to the surface. Panel b shows two-electron scattering by a phonon with the momentum transfer q. Panel c shows electron scattering near the Fermi level, relevant to the pairing, with zero momentum transfer q = 0. Panel d is the same as panel c but with nonzero momentum transfer q.

The magnetic field does not suppress the triplet superconductivity induced by the forward phonon scattering. In a spin singlet superconductor, the superconducting gap vanishes when the magnetic field strength reaches the Chandrasekhar-Clogston limit, and the normal state becomes the ground state. With the nonzero Rashba spin-orbit coupling, the triplet pairing field usually comes up via the hybridization effect when the singlet pairing field is nonzero. In this case, the triplet pairing field vanishes as the singlet pairing field vanishes. However, in our work, the triplet superconductivity is induced by many-body interactions rather than the hybridization effect. Therefore, there is no Chandrasekhar-Clogston limit49,50,51.

Results

We first set up a platform for free electrons on a square lattice with e-ph coupling, as shown in Fig. 1. The entire Hamiltonian is given by H = H0 + Hph + He−ph, where

Here, \({c}_{{{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}},s}^{{{{\dagger}}} }\) (ck,s) creates (annihilates) an electron with spin s ( = ↑, ↓) and momentum k, \({b}_{{{{{{{{\bf{q}}}}}}}}}^{{{{\dagger}}} }\) (bq) creates (annihilates) a phonon with momentum q, t is the nearest-neighbor hopping integral, and a is the lattice constant. The second term in H0 represents the RSOC with the coupling strength λSOC and the momentum dependence \(d({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}})={{{{{{{\bf{L}}}}}}}}({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}})\cdot {{{{{{{\boldsymbol{\sigma }}}}}}}}=\sin ({k}_{y}a)+i\sin ({k}_{x}a)\), where \({{{{{{{\bf{L}}}}}}}}({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}})=(\sin {k}_{y}a,-\sin {k}_{x}a,0)\) and σ is the Pauli matrix. Ω is the optical phonon frequency, gL is the Landé factor, μB is the Bohr magneton, Bz is the magnetic field, μ is the chemical potential, and N is the lattice size. Finally, g(q) is the matrix element of the e-ph interaction.

We mainly focus on the forward phonon scattering, which originates from the combination of the vibration of dipoles on the substrate surface and the two-dimensional nature of the add-on layer. This forward e-ph interaction was observed in FeSe/STO41,42, where it was found that the ferroelectric instability in SrTiO3 creates electric dipoles with Ti cations and oxygen anions at the surface. The vibration of oxygen anions modulates the dipole potential on the top layer, which is proportional to \({e}^{-| {{{{{{{{\bf{q}}}}}}}}}_{\parallel }| /{q}_{0}}\), where q∥ is the wave vector parallel to the interface and q0 is the scattering range. Reference41 has shown that q0 is proportional to \(\sqrt{{\epsilon }_{\perp }/{\epsilon }_{\parallel }}\), where ϵ∥ and ϵ⊥ are the dielectric constants parallel and perpendicular to the interface, respectively. In two-dimensional materials, ϵ∥ is much larger than ϵ⊥, q0 itself becomes very small. For instance, the scattering range is found to be q0a ~ 0.1 − 0.3 in FeSe/STO41,42. Here, we define the e-ph coupling as \({g}^{2}({{{{{{{\bf{q}}}}}}}})={g}_{0}^{2}f({{{{{{{\bf{q}}}}}}}})\), where g0 describes the interaction strength and f(q) describes its momentum dependence. We adopt \(f({{{{{{{\bf{q}}}}}}}})=4{\pi }^{2}\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi }{q}_{0}}{e}^{-| {{{{{{{\bf{q}}}}}}}}| /{q}_{0}}\)43,47 and 1 to describe the forward and uniform e-ph couplings, respectively.

We analyze our Hamiltonian using the Migdal-Eliashberg (ME) theory in the Nambu space (for details, see Supplementary note 1)52. Without Coulomb interactions, our model only supports spin singlet s-wave and spin triplet p-wave pairing fields (see Supplementary note 2)53,54. Therefore, the initial anomalous self-energy has both s-wave and p-wave features. We assume that the initial pairing field has the form of i[ψs(k) + L(k) ⋅ σ]σy55, where ψs(k) describe the s-wave pairing. The stability of the superconducting state is determined by the self-consistent anomalous self-energy. To further demonstrate the stability of the superconducting state under an applied magnetic field, we evaluate the free energy of an effective model with an attractive interaction, which describes the second-order approximation of the e-ph coupling (see Supplementary note 2).

Without other statement, we set the lattice size N = 40 × 40, the temperature T = 0.01t, the dimensionless e-ph coupling strength \({\lambda }_{{{{{{{{\rm{ph}}}}}}}}}=\frac{2{g}_{0}^{2}}{W\Omega }\langle f({{{{{{{\bf{q}}}}}}}})\rangle =0.8\), and the electron density n = 0.2. This small electron density is chosen because it generates a relatively small critical magnetic field for TSC. This information will be discussed in detail later. A weak spin-orbit coupling has a tiny effect on the bandwidth W, and we set W = 8t. Following ref. 43, we assume that the relevant phonon branch for the forward scattering is an optical phonon with Ω = t. Our work uses an intermediate e-ph coupling strength to generate a large superconducting gap to help analyze theoretical results. To connect to the real material FeSe/STO, we also present results for a model with λph = 0.065. The results obtained from this model are consistent with the conclusion obtained from a model with λph = 0.8. In addition, we tested the robustness of our conclusion against the variation of λph in Supplementary note 3 and Supplementary note 4. Previous studies showed that the Migdal-Eliashberg theory has difficulty in predicting the competition between the charge-density-wave and the superconducting state when the e-ph coupling constant λph > 0.556. In addition, the prediction of the superconducting temperature is not reliable when λph > 0.5. However, these pathological features do not affect our conclusion. First, the forward phonon scattering does not generate a charge-density-wave. Second, our conclusion depends on the existence of superconductivity rather than the superconducting transition temperature. Therefore, the physical scenario obtained from our results is reliable.

To further extract the topological information, an effective single-particle Hamiltonian is constructed by fitting to the ME theory, with \({H}^{{\prime} }={H}_{0}+{\sum }_{{{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}}}\Sigma ({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}})\). In the Nambu space, the self-energy at zero frequency Σ(k) is a 4 × 4 matrix, obtained by extrapolating the self-energy Σ(k, iωn) in the Matsubara frequency ωn space as ωn → 0. Topological invariants such as the first Chern number of \({H}^{{\prime} }\) can thus be calculated in an efficient way (see Methods section)57.

Superconductivity

Superconductivity with the interfacial e-ph interaction is studied under an external out-of-plane magnetic field. Figure 2a shows the q0-Bz phase diagram at λSOC = 0.3t. A phase transition from a trivial superconducting (SC) state to a topological superconducting (TSC) state occurs as the magnetic field increases when q0 < 1.2/a. The red dashed curve in Figs. 2 and 3 represents the phase boundary between these two phases. The critical magnetic field Bc for this phase transition exhibits a nonmonotonic behavior. Bc first rapidly increases with q0 for q0 < 0.4/a and then slightly decreases. The TSC state becomes unstable and is replaced by a metallic (M) state when q0 > 1.2/a. For a Holstein model with a uniform e-ph coupling, the external magnetic field rapidly suppresses the SC state (see Supplementary note 8). These results clearly demonstrate that the superconductivity induced by a short-ranged forward e-ph interaction is robust against an applied magnetic field. This fact will be crucial to create field-induced topological superconductivity.

a Phase diagram as a function of magnetic field Bz and scattering range q0. The magnetic field Bz is applied perpendicular to the surface. The color map represents the ratio R between spin-up triplet and singlet pairing fields. Here, SC, TSC, and M denote trivial superconducting, topological superconducting, and metallic states, respectively. The red dashed curve represents the phase boundary between SC and TSC states. b The evolution of the singlet pairing field Δ↑↓ with the magnetic field Bz. c The evolution of the triplet pairing field Δ↑↑ with the magnetic field. Here, we set the Rashba spin-orbit coupling λSOC = 0.3t.

a Phase diagram as a function of magnetic field Bz and spin-orbit coupling λSOC. The color map represents the ratio R between spin-up triplet and singlet pairing fields. The red dashed curve represents the phase boundary between trivial superconducting (SC) and topological superconducting (TSC) states. b The evolution of the singlet pairing field Δ↑↓ with the magnetic field Bz. c The evolution of the spin-up triplet pairing field Δ↑↑ with the magnetic field Bz. The scattering range is set as q0 = 0.4/a, where a is the lattice constant.

The persistence of the superconductivity under a magnetic field at small q0 is attributed to the emergence of a triplet pairing potential. Now, we demonstrate this behavior using a mean-field approach. In the second-order approximation, the two-particle interaction mediated by the e-ph interaction is given by

which is represented by the Feynman diagram in Fig. 1b, d. In the Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer theory58, this interaction is decoupled into pairing terms, and a pair of electrons with momenta k and − k and spin s and \({s }^{{\prime} }\) is coupled via an effective pairing potential, given by \({V}_{{{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}},s ,{s }^{{\prime} }}={\sum }_{{{{{{{{\bf{q}}}}}}}}}\frac{{U}_{{{{{{{{\bf{q}}}}}}}}}}{N}\langle {c}_{{{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}}+{{{{{{{\bf{q}}}}}}}},s }^{{{{\dagger}}} }{c}_{-{{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}}-{{{{{{{\bf{q}}}}}}}},{s }^{{\prime} }}^{{{{\dagger}}} }\rangle\). When Uq is independent of q, the effective potential becomes \({V}_{{{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}},s ,{s }^{{\prime} }}=\frac{U}{N}{\sum }_{{{{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}}}^{{\prime} }}\langle {c}_{{{{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}}}^{{\prime} },s }^{{{{\dagger}}} }{c}_{-{{{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}}}^{{\prime} },{s }^{{\prime} }}^{{{{\dagger}}} }\rangle\). In this case, the effective potential on two electrons with the same spin is zero because \(\langle {c}_{{{{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}}}^{{\prime} },s }^{{{{\dagger}}} }{c}_{-{{{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}}}^{{\prime} },s }^{{{{\dagger}}} }\rangle\) has to be odd in parity. However, when Uq is nonzero only at small momentum, say ∣q∣ = 0, the effective potential on two electrons with the same spin becomes \(U\langle {c}_{{{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}},s }^{{{{\dagger}}} }{c}_{-{{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}},s }^{{{{\dagger}}} }\rangle\), which is sketched in Fig. 1c. In the presence of the spin-orbit coupling or a magnetic field, the effective triplet pairing potential is no longer zero. This nonzero triplet pairing potential can further enhance the triplet pairing field under a magnetic field.

To shed light on the pairing symmetry, we examine the evolution of both spin-singlet and triplet pairing fields under a magnetic field. (The momentum-dependent anomalous self-energy is plotted in Supplementary note 6). Here, we focus on the average value of the pairing field and label the singlet, spin-up triplet, and spin-down triplet pairing fields as Δ↑↓, Δ↑↑, and Δ↓↓, respectively. These average pairing fields are defined as \({\Delta }_{s {s }^{{\prime} }}=\frac{1}{N}{\sum }_{{{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}}}| {\Delta }_{s {s }^{{\prime} }}({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}})|\), where \({\Delta }_{s {s }^{{\prime} }}({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}})=\langle {c}_{{{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}},s }{c}_{-{{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}},{s }^{{\prime} }}\rangle\). Figure 2b, c plot Δ↑↓ and Δ↑↑, respectively, for different values of q0. The forward e-ph interaction induces only the s-wave singlet SC state in the absence of the magnetic field and RSOC59. RSOC mixes spin-up and spin-down electrons, leading to a nonzero triplet pairing field at Bz = 060. Our nonzero Δ↑↑ at Bz = 0 shown in Fig. 2c is consistent with this prediction. As shown in Fig. 2b, a magnetic field suppresses the singlet pairing field and enhances the spin-up triplet pairing field, consistent with our mean-field analysis. The nonzero Δ↑↓ under a strong magnetic field is attributed to the RSOC. To further gain insight into the evolution of the triplet pairing field under the magnetic field, we use the color map of Fig. 2a to represent the ratio R between Δ↑↑ and Δ↑↓. It is found that the pairing field is dominated by the singlet (spin-up triplet) field as gLμBBz < ( > )0.4.

Next, we analyze the effect of the RSOC. Figure 3a plots the Bz-λSOC phase diagram at q0 = 0.4/a, and Fig. 3b, c show the corresponding singlet and spin-up triplet pairing fields as a function of Bz, respectively. It is found that the critical magnetic field of this phase transition depends on λSOC very weakly. In fact, the topological phase transition is induced by the Lifshift transition that one of two bands moves above the Fermi level (This result will be explained in the next section.). Therefore, the critical magnetic field strongly depends on the charge density rather than λSOC (see Supplementary note 4).

At λSOC = 0, there is a discontinuous phase transition from a pure singlet SC state to a pure triplet SC state at gLμBBz = 0.3t. In our calculations, the spin-up and spin-down triplet pairings have different symmetric structures (\({\Delta }_{\uparrow \uparrow }\propto -\sin {k}_{y}-i\sin {k}_{x}\) and \({\Delta }_{\downarrow \downarrow }\propto \sin {k}_{y}-i\sin {k}_{x}\)), leading to + 1 and − 1 chern numbers on the spin-up and spin-down bands in the pure triplet SC state, respectively. In this case, the total Chern number is zero. These different symmetric structures originate from the Rashba spin-orbit coupling. When the Rashba spin-orbit coupling is absent, spin-up and spin-down triplet pairings could have the same symmetric structure, leading to a nonzero Chern number. Therefore, the topological property in the pure triplet SC state with both spin-up and spin-down pairings is undetermined. By further increasing the magnetic field, the spin-down band moves above the Fermi surface, and the SC state is nontrivial.

Topological phase transition

Our topological phase transition is induced by a Lifshitz transition. This is confirmed by plotting the momentum-dependent spectral function As(k, ω) as shown in Fig. 4a–d with q0 = 0.4/a and λSOC = 0.3t. As(k, ω) is obtained from the analytic continuation of the imaginary-frequency Green’s function using the Páde approximation. Here, the band gap near the Fermi level shown in Fig. 4a–d is not the Bogoliubov gap because the analytic continuation is performed on the normal Green’s function. The spin SU(2) symmetry is broken by the RSOC. With Bz = 0, the RSCO lifts the degeneracy of bands except for k = (0, 0) and k = (π, π). With nonzero Bz, the band degeneracy is lifted everywhere. We label a band with a smaller (larger) Fermi momentum as band α (η). At Bz = 0, spin-up and spin-down electrons have an equivalent weight on both bands. At a fixed electron density, the magnetic field transfers spin-up (spin-down) electrons to the η (α) band. With increasing magnetic field, the α band at the Γ point slowly moves from below to above the Fermi surface. At gLμBBz = 1.3t, the α band moves across the Fermi surface at the Γ point and is dominated by the spin-down electrons in the low-energy region (see Supplementary note 7). The ground state becomes the TSC state when band α moves above the Fermi surface (gLμBBz > 1.3t).

Panels a and b plot the spectral functions A↑(k, ω) in the momentum (k) and the energy (ω) space for the spin-up electrons at gLμBBz = 0.45t and 1.45t, respectively. gL is the Landé factor and μB is the Bohr magneton. Panels c and d plot the corresponding spectral functions A↓(k, ω) for the spin-down electrons. e The evolution of the Bogoliubov gap Δ as a function of the magnetic field Bz. Here, ED and SF denotes that results obtained from exact diagonalization and spectral functions, respectively. f The Chern number C as a function of the magnetic field Bz. Panels g and h plot quasiparticle band structures of a finite thickness ribbon in the trivial superconducting (SC) and topological superconducting states (TSC), respectively. Here, the Rashba spin-orbit coupling is set as λSOC = 0.3t and the scattering range is q0 = 0.4/a.

We further examine the detail of the topological phase transition. Fig. 4e plots the Bogoliubov gap Δ obtained from the spectral function (SF) As(k, ω) and the exact diagonalization (ED) of the effective single-particle Hamiltonian \({H}^{{\prime} }\). Δ from the spectral function is obtained by searching for the minimal excitation energy. With increasing magnetic field Bz, both Bogoliubov gaps gradually approach zero at gLμBBz = 1.3t and rapidly increase by further increasing Bz, signaling the topological phase transition at gLμBBz = 1.3t. This transition accompanies the change in the Chern number from 0 to 1, as shown in Fig. 4f, confirming that the Lifshitz transition induces the topological transition.

The TSC state at high fields is further confirmed by examining the edge spectrum. For this purpose, we construct an effective single-particle Hamiltonian on a finite-thickness ribbon with a periodic boundary condition along the x-direction and an open boundary condition along the y-direction. In this case, the self-energy Σ(kx, ry) is obtained from the Fourier transform of Σ(k). We cut off Σ(kx, ry) at a distance ∣ry∣ = 3a because Σ(kx, ry) is negligible at ∣ry∣ > 3a (see supplementary note 5). Figure 4g, h plot the ribbon-geometry spectrum with λSOC = 0.3t and a ribbon thickness of 100a. We observe a nonzero Bogoliubov gap with q0 = 0.4/a and gLμBBz = 0.2t and gapless chiral Majorana edge modes with q0 = 0.4/a and gLμBBz = 1.8t. This result confirms the TSC state in the latter.

Our results show that the topological superconductivity is induced by the Lifshitz transition, where one band moves beyond the Fermi level. Therefore, the critical magnetic field is proportional to the charge density. A smaller charge density should generate a smaller critical field. For example, we observe that the critical magnetic field is suppressed to 0.04t at n = 0.1 (see Supplementary note 4).

Relevance to materials

We proposed a generic mechanism to obtain topological superconductivity using forward phonon scattering. Next, we will discuss some potential materials to apply our mechanism. The most straightforward material is FeSe/STO, although the TSC has not been observed in FeSe/STO. A previous theoretical study found that a model with t = 75 meV, Ω = 100 meV, q0 = 0.1/a, and \({g}_{0}=\sqrt{0.15}\Omega \sim \sqrt{0.2}\Omega\) can reproduce the experimentally observed angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy in the monolayer FeSe/STO43. Here, we performed calculations with these parameters at the reduced charge density n = 0.05 to suppress the critical magnetic field for the TSC. Thus, our theoretical model should correspond to the low-density electron gas grown on the STO substrate. The RSOC is set as λSOC = 0.3t. This RSOC could be induced by considering metallic compounds containing heavy elements, but the results are not sensitive to the value of RSOC, as discussed earlier. Figure 5a, b plot the Bogoliubov gaps from exact diagonalization of the effective Hamiltonian for \({g}_{0}=\sqrt{0.15}\Omega\) (λph = 0.04875) and \({g}_{0}=\sqrt{0.2}\Omega\) (λph = 0.065), respectively. The green (blue) region represents the trivial (topological) superconducting state. It is found that the critical magnetic field for TSC is about 15 T when \({g}_{0}=\sqrt{0.15}\Omega\) and 52 T when \({g}_{0}=\sqrt{0.2}\Omega\). This range of the magnetic field is beyond the upper critical magnetic field for conventional superconductors, where the superconductivity vanishes. However, the upper critical magnetic field for the forward phonon scattering-induced superconductivity can be very large. For example, the upper critical magnetic field in the monolayer FeSe/STO is about 30.2 T61.

Panels a and b plot the evolution of the Bogoliuov gap Δ as a function of the magnetic field Bz for the electron-phonon coupling strength \({g}_{0}=\sqrt{1.5}\Omega\) and \({g}_{0}=\sqrt{2}\Omega\), respectively. SC and TSC denote trivial superconducting and topological superconducting states, respectively. Here, phonon frequency Ω = 100 meV, the scattering range q0 = 0.1/a, the hopping parameter t = 75 meV, the Rashba spin-orbit coupling λSOC = 0.3t, and the electron density n = 0.05.

Because our mechanism requires a change in the Fermi surface topology by a magnetic field, it is necessary to reduce the carrier density further, which might be challenging with iron-based superconductors. However, our results with realistic e-ph coupling parameters for FeSe/STO can be used to guide implementing topological superconductors with two-dimensional semiconductors, including KTaO362 and GaAs63, where a small charge density is easy to be made. Since the lowest energy conduction band is located at the Γ point in KTaO3 and GaAs, our two-dimensional tight-binding model can effectively describe their low-energy band structure. For two-dimensional semiconductors, we expect a large ratio between the inplane dielectric constant ϵ∥ and out-of-plane dielectric constant ϵ⊥, leading to a small value of q0 and a large value of g0, which is proportional to \(\frac{\sqrt{{\epsilon }_{\parallel }}}{{\epsilon }_{\perp }}\)42. In addition, we note that the growth of KTaO3 and GaAs on the SrTiO3 substrate has been achieved in experiments62,63. Furthermore, two-dimensional superconductivity has been confirmed on the surface of KTaO364. With these considerations, heterostructures, such as KTaO3/STO and GaAs/STO, might be promising pathways to achieve topological superconductivity.

Conclusion

We have found that the forward e-ph interaction favors spin-triplet superconductivity under a magnetic field. We also predict a magnetic-field-induced transition (λSOC = 0) or crossover (λSOC ≠ 0) from a singlet-dominant to a triplet-dominant pairing phase. These results allow us to design a protocol to create artificial chiral topological superconductor via the forward e-ph interaction. Since the triplet superconductivity is intrinsically generated, we do expect the superconducting gap to be larger than that of a superconducting-proxitimized system, thus providing a pathway towards high-temperature non-Abelian Majorana platforms4,65,66,67.

The relaxation of Rashba interaction greatly facilitates the materialization of our platform. For example, the 2D electron gas can be obtained by using the metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistors68. Since the electron gas can feature rather high mobility, the disorder effect will be suppressed to guarantee the robustness of Majorana physics. We hope our work will inspire more theoretical and experimental efforts to explore Majorana physics from an electron-phonon origin.

Methods

Migdal-Eliashberg theory

We use the self-consistent Migdal-Elaishberg approximation to study the two-dimensional single-band model with e-ph interactions. The self-consistent Migdal-Eliashberg approximation is a diagrammatic approach, which neglects higher-order corrections to the e-ph interaction vertex. In our calculations, we consider two self-energy diagrams in the Naumbu space, which are represented by

Here, G(k, in) and F(k, iωn) are the electron normal and anomalous Green’s function with the momentum k and the fermionic Matsubara frequency ωn. D(q, iνn) is the phonon Green’s function with the momentum q and the bosonic Matsubara frequency νn. The Hartree energy ΣH(k) is given by

The selfenergy is determined by self-consistently solving Dyson’s equation. In our calculations, the self-consistent calculation is only performed on the electronic part, and we use the bare phonon Green’s function. When the electronic density is small, the renormalization of the phonon’s band structure is small, and this approximation is valid. The same procedure has been adopted in the previous studies of the monolayer FeSe/STO43.

Exact diagonalization

In the main text, we exactly diagonalize the effective one-particle Hamiltonian to analyze the Chern number. The effective one-particle Hamiltonian is given by

where H0(k) is the non-interaction Hamiltonian at the momentum k and Σ(k) is the self-energy at zero frequency, obtained by extrapolating the self-energy Σ(k, iωn) in the Matsubara frequency ωn space as ωn → 0. The effective one-particle Hamiltonian \({H}^{{\prime} }({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}})\) is a 4 × 4 matrix, and we numerically diagonalize it.

We follow the method proposed in ref. 57 to evaluate the Chern number. we first define a U(l) link variable from the wave function ψn(k) of the nth band as

where \({N}_{{{{{{{{\bf{d}}}}}}}}}({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}})=|\left\langle {\psi }_{n}({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}})\right\vert {\psi }_{n}({{{{{{{\bf{k}}}}}}}}+{{{{{{{\bf{d}}}}}}}})\rangle|\). Next, we define a lattice field strength by

The Chern number associated to the nth band is given as

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Code availability

The Migdal-Eliashberg code can be downloaded at https://github.com/sli43/forward-phonon-scattering.

References

Freedman, M., Nayak, C. & Walker, K. Towards universal topological quantum computation in the \(\nu =\frac{5}{2}\) fractional quantum Hall state. Phys. Rev. B 73, 245307 (2006).

Nayak, C., Simon, S. H., Stern, A., Freedman, M. & Das Sarma, S. Non-abelian anyons and topological quantum computation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 1083–1159 (2008).

Field, B. & Simula, T. Introduction to topological quantum computation with non-abelian anyons. Q. Sci. Technol. 3, 045004 (2018).

Lian, B., Sun, X.-Q., Vaezi, A., Qi, X.-L. & Zhang, S.-C. Topological quantum computation based on chiral Majorana fermions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 115, 10938–10942 (2018).

Lutchyn, R. M. et al. Majorana zero modes in superconductor-semiconductor heterostructures. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 52–68 (2018).

McMillan, W. L. Tunneling model of the superconducting proximity effect. Phys. Rev. 175, 537–542 (1968).

Fu, L. & Kane, C. L. Superconducting proximity effect and Majorana fermions at the surface of a topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 096407 (2008).

Qi, X.-L., Hughes, T. L., Raghu, S. & Zhang, S.-C. Time-reversal-invariant topological superconductors and superfluids in two and three dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 187001 (2009).

Alicea, J. New directions in the pursuit of Majorana fermions in solid state systems. Rep. Progr. Phys. 75, 076501 (2012).

Beenakker, C. Search for Majorana fermions in superconductors. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 4, 113–136 (2013).

Jiang, J.-H. & Wu, S. Non-abelian topological superconductors from topological semimetals and related systems under the superconducting proximity effect. J. Phys. 25, 055701 (2013).

Xu, J.-P. et al. Artificial topological superconductor by the proximity effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 217001 (2014).

Sajadi, E. et al. Gate-induced superconductivity in a monolayer topological insulator. Science 362, 922–925 (2018).

Zhang, P. et al. Observation of topological superconductivity on the surface of an iron-based superconductor. Science 360, 182–186 (2018).

Wang, D. et al. Evidence for Majorana bound states in an iron-based superconductor. Science 362, 333–335 (2018).

Lee, K., Hazra, T., Randeria, M. & Trivedi, N. Topological superconductivity in Dirac honeycomb systems. Phys. Rev. B 99, 184514 (2019).

Machida, T. et al. Zero-energy vortex bound state in the superconducting topological surface state of Fe(Se,Te). Nature Mater. 18, 811–815 (2019).

Zhu, S. et al. Nearly quantized conductance plateau of vortex zero mode in an iron-based superconductor. Science 367, 189–192 (2019).

Rameau, J. D., Zaki, N., Gu, G. D., Johnson, P. D. & Weinert, M. Interplay of paramagnetism and topology in the Fe-chalcogenide high-Tc superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 99, 205117 (2019).

Trang, C. X. et al. Conversion of a conventional superconductor into a topological superconductor by topological proximity effect. Nature Commun. 11, 159 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. Evidence for dispersing 1D Majorana channels in an iron-based superconductor. Science 367, 104–108 (2020).

Chen, C. et al. Atomic line defects and zero-energy end states in monolayer Fe(Te,Se) high-temperature superconductors. Nature Phys. 16, 536–540 (2020).

Mascot, E. et al. Origin of topological surface superconductivity in FeSe0.45Te0.55. arXiv: 2102.05116 (2021).

Zhang, R.-X. & Das Sarma, S. Intrinsic time-reversal-invariant topological superconductivity in thin films of iron-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 137001 (2021).

Qi, X.-L. & Zhang, S.-C. Topological insulators and superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1057–1110 (2011).

Yang, J. et al. Spin-triplet superconductivity in K2Cr3As3. Sci. Adv. 7, 4432 (2021).

Chou, Y.-Z., Wu, F., Sau, J. D. & Das Sarma, S. Correlation-induced triplet pairing superconductivity in graphene-based moiré systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 217001 (2021).

Hor, Y. S. et al. Superconductivity in CuxBi2Se3 and its implications for pairing in the undoped topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 057001 (2010).

Fu, L. & Berg, E. Odd-parity topological superconductors: Theory and application to CuxBi2Se3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 097001 (2010).

Mourik, V. et al. Signatures of Majorana fermions in hybrid superconductor-semiconductor nanowire devices. Science 336, 1003–1007 (2012).

Kallin, C. Chiral p-wave order in Sr2RuO4. Rep. Prog. Phys. 75, 042501 (2012).

Das, A. et al. Zero-bias peaks and splitting in an Al-InAs nanowire topological superconductor as a signature of Majorana fermions. Nature Phys. 8, 887–895 (2012).

Xu, G., Lian, B., Tang, P., Qi, X.-L. & Zhang, S.-C. Topological superconductivity on the surface of Fe-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 047001 (2016).

Liu, Y.-C., Zhang, F.-C., Rice, T. M. & Wang, Q.-H. Theory of the evolution of superconductivity in Sr2RuO4 under anisotropic strain. npj Q. Mater. 12, 12 (2017).

Li, Y. W. et al. Observation of topological superconductivity in a stoichiometric transition metal dichalcogenide 2M-WS2. Nature Commun. 12, 2874 (2021).

Kezilebieke, S. et al. Topological superconductivity in a van der waals heterostructure. Nature 588, 424–428 (2020).

Aghaee, M. et al. InAs-Al hybrid devices passing the topological gap protocol. Phys. Rev. B 107, 245423 (2023).

Hui, H.-Y., Sau, J. D. & Das Sarma, S. Bulk disorder in the superconductor affects proximity-induced topological superconductivity. Phys. Rev. B 92, 174512 (2015).

Lu, Y., Virtanen, P. & Heikkilä, T. T. Effect of disorder on Majorana localization in topological superconductors: A quasiclassical approach. Phys. Rev. B 102, 224510 (2020).

Stanescu, T. D. & Sarma, S. D. Proximity-induced superconductivity generated by thin films: Effects of fermi surface mismatch and disorder in the superconductor. arXiv:2206.13526 (2022).

Lee, J. J. et al. Interfacial mode coupling as the origin of the enhancement of Tc in FeSe films on SrTiO3. Nature 515, 245–248 (2014).

Lee, D.-H. What makes the Tc of FeSeSrTiO3 so high? Chin. Phys. B 24, 117405 (2015).

Rademaker, L., Wang, Y., Berlijn, T. & Johnston, S. Enhanced superconductivity due to forward scattering in FeSe thin films on SrTiO3 substrates. N. J. Phys. 18, 022001 (2016).

Zhang, S. et al. Role of SrTiO3 phonon penetrating into thin FeSe films in the enhancement of superconductivity. Phys. Rev. B 94, 081116(R) (2016).

Rebec, S. N. et al. Coexistence of replica bands and superconductivity in FeSe monolayer films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 067002 (2017).

Song, Q. et al. Evidence of cooperative effect on the enhanced superconducting transition temperature at the FeSe/SrTiO3 interface. Nature Commun. 10, 758 (2019).

Rademaker, L., Alvarez-Suchini, G., Nakatsukasa, K., Wang, Y. & Johnston, S. Enhanced superconductivity in FeSe/SrTiO3 from the combination of forward scattering phonons and spin fluctuations. Phys. Rev. B 103, 144504 (2021).

Sau, J. D., Lutchyn, R. M., Tewari, S. & Das Sarma, S. Generic new platform for topological quantum computation using semiconductor heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 040502 (2010).

Chandrasekhar, B. S. A note on the maximum critical field of high-field superconductors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1, 7–8 (1962).

Clogston, A. M. Upper limit for the critical field in hard superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 9, 266–267 (1962).

Xie, Y.-M., Zhou, B. T. & Law, K. T. Spin-orbit-parity-coupled superconductivity in topological monolayer WTe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 107001 (2020).

Marsiglio, F. Eliashberg theory: A short review. Ann. Phys. 417, 168102 (2020).

Wan, X. & Savrasov, S. Y. Turning a band insulator into an exotic superconductor. Nature Commun. 5, 4144 (2014).

Brydon, P. M. R., Das Sarma, S., Hui, H.-Y. & Sau, J. D. Odd-parity superconductivity from phonon-mediated pairing: Application to CuxBi2Se3. Phys. Rev. B 90, 184512 (2014).

Yoshida, T. & Yanase, Y. Topological d + p-wave superconductivity in Rashba systems. Phys. Rev. B 93, 054504 (2016).

Chubukov, A. V., Abanov, A., Esterlis, I. & Kivelson, S. A. Eliashberg theory of phonon-mediated superconductivity — when it is valid and how it breaks down. Ann. Phys. 417, 168190 (2020).

Fukui, T., Hatsugai, Y. & Suzuki, H. Chern numbers in discretized Brillouin zone: Efficient method of computing (spin) Hall conductances. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 74, 1674–1677 (2005).

Bardeen, J., Cooper, L. N. & Schrieffer, J. R. Theory of superconductivity. Phys. Rev. 108, 1175–1204 (1957).

Li, S. & Johnston, S. Quantum monte carlo study of lattice polarons in the two-dimensional three-orbital Su-Schrieffer-Heeger model. npj Q. Mater. 5, 40 (2020).

Gor’kov, L. P. & Rashba, E. I. Superconducting 2D system with lifted spin degeneracy: Mixed singlet-triplet state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 037004 (2001).

Zhou, G. et al. Interface induced high temperature superconductivity in single unit-cell FeSe on SrTiO3(110). Appl. Phys.Lett. 108, 202603 (2016).

Opoku, F., Govender, K. K., van Sittert, C. G. C. E. & Govender, P. P. Enhancing charge separation and photocatalytic activity of cubic SrTiO3 with perovskite-type materials MTaO3 (M=Na, K) for environmental remediation: A first-principles study. ChemistrySelect 2, 6304–6316 (2017).

Fujioka, H. et al. Epitaxial growth of semiconductors on SrTiO3 substrates. J. Cryst. Growth 229, 137–141 (2001).

Ren, T. et al. Two-dimensional superconductivity at the surfaces of KTaO3 gated with ionic liquid. Sci. Adv. 8, 4273 (2022).

Kitaev, A. Fault-tolerant quantum computation by anyons. Ann. Phys. 303, 2–30 (2003).

Nayak, C., Simon, S. H., Stern, A., Freedman, M. & Das Sarma, S. Non-abelian anyons and topological quantum computation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 1083–1159 (2008).

Sarma, S. D., Freedman, M. & Nayak, C. Majorana zero modes and topological quantum computation. Nature News 1, 15001 (2015).

Klitzing, K. V., Dorda, G. & Pepper, M. New method for high-accuracy determination of the fine-structure constant based on quantized hall resistance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 494–497 (1980).

Acknowledgements

S.L. and S.O. are supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, National Quantum Information Science Research Centers, Quantum Science Center. L.-H.H. and R.-X.Z. are supported by a startup fund from University of Tennessee. This research used resources of the Compute and Data Environment for Science (CADES) at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, which is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC05-00OR22725. We thank Y. Wang and R. S. Fishman for discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

This manuscript has been authored by UT-Battelle, LLC under Contract No. DE-AC05-00OR22725 with the U.S. Department of Energy. The United States Government retains and the publisher, by accepting the article for publication, acknowledges that the United States Government retains a non-exclusive, paid-up, irrevocable, world-wide license to publish or reproduce the published form of this manuscript, or allow others to do so, for United States Government purposes. The Department of Energy will provide public access to these results of federally sponsored research in accordance with the DOE Public Access Plan (http://energy.gov/downloads/doe-public-access-plan).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L. performed calculations. S.L., L.-H.H., R.-X.Z., and S.O. contributed to analyzing the data and writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, S., Hu, LH., Zhang, RX. et al. Topological superconductivity from forward phonon scatterings. Commun Phys 6, 235 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-023-01311-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-023-01311-z

This article is cited by

-

Majorana corner states on the dice lattice

Communications Physics (2023)