Abstract

Standard microscopic approach to magnetic orders is based on assuming a Heisenberg form for inter-atomic exchange interactions. These interactions are considered as the driving force for the ordering transition with magnetic moments serving as the primary order parameter. Any higher-rank multipoles appearing simultaneously with such magnetic order are typically treated as auxiliary order parameters rather than a principal cause of the transition. In this study, we show that these traditional assumptions are violated in the case of PrO2. Evaluating a full set of Pr-Pr superexchange interactions from a first-principles many-body technique we find that its unusual non-collinear 2k magnetic structure stems from high-rank multipolar interactions, and that the corresponding contribution of the Heisenberg interactions is negligible. The observed magnetic order in PrO2 is thus auxiliary to high-rank “hidden” multipoles. Within this picture we consistently account for previously unexplained experimental observations like the magnitude of exchange splitting and the evolution of magnetic structure in external field. Our findings challenge the standard paradigm of observable magnetic moments being the driving force for magnetic transitions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In systems with localized f-electrons, such as compounds with rare-earths or actinides elements, magnetic interactions can induce a rich variety of magnetic orders, often quite complex and non-collinear1,2. The origin of these magnetic structures is usually identified as stemming from a competition between on-site anisotropy (crystal field effects) and inter-site interactions coupling the magnetic moments of f-ions. However, in general, inter-site exchange interactions also include the terms with higher powers of the on-site magnetic moment operator, namely, multipoles3. Discovery of a number of systems with so-called “hidden” order4,5,6,7 has stimulated growing interest to multipolar inter-site exchange interactions. The “hidden”-order systems undergo a pronounced second-order phase transition without developing any conventional magnetic order directly observable, e.g., in neutron diffraction experiments. Apart from f-electron systems3,8, heavy transition-metal oxides with strong spin-orbit coupling have been also found to host multipolar orders9,10,11,12. However, when an order of sizable conventional magnetic moments is detected experimentally, it is by default assumed to be caused by those moments themselves. Here we show that even in this case multipolar inter-site exchange interactions can be not only as important as ordinary Heisenberg terms, but that they can entirely determine the magnetic order in a real correlated f-electron system.

The multipolar moment operators, \({\widehat{O}}_{K}^{Q}\left(K=1,..2J,Q=-K,..K\right)\) are normalized Stevens operators; the latter have been used in the theory of rare-earth magnetism for over 50 years1,3,13. They provide an irreducible operator basis in the space of wave functions for a given ground state multiplet (GSM) of an f-ion with the total angular momentum \(J\) (see Supplementary Note 1 for the list of Stevens operators up to \(K=5\)). Any Hamiltonian acting within the GSM of an f-ion can be expressed as a linear combination of the \({\widehat{O}}_{K}^{Q}\) operators. Therefore, the Hamiltonian describing a system of interacting ions with localized f-electron shells generally reads:

where the summations run over the \(i,j\) lattice sites. The inter-site exchange interaction in the case of correlated insulators is due to superexchange; the parameters \({V}_{{KQ},{K}^{{\prime} }{Q}^{{\prime} }}^{{ij}}\) are thus two-site superexchange interaction (SEI) parameters and \({\widehat{H}}_{{{{{{\rm{CF}}}}}}}^{i}={\sum }_{{KQ}}{B}_{{KQ}}{\widehat{{{{{{\mathscr{O}}}}}}}}_{K}^{Q}\) is the standard single-site CF Hamiltonian1 expressed through unnormalized Stevens operators \({\widehat{{{{{{\mathscr{O}}}}}}}}_{K}^{Q}\). The number of higher rank multipoles (K > 1) and their associated interaction parameters increase rapidly with the multiplicity of the ground state of the f-ion.

Unless there is experimental evidence of “hidden” multipolar order in the system or if large lattice distortions are associated with the magnetic ordering, only first-order (dipole) inter-site interaction terms with K = 1 are typically considered in theoretical analysis. They are of the handbook1 Heisenberg-like form \(\mathop{\sum}\nolimits_{i,j}{\widehat{{{{{{\bf{J}}}}}}}}_{i}{\bar{I}}_{{ij}}{\widehat{{{{{{\bf{J}}}}}}}}_{j}\), where the dipole magnetic moment at the site \(i\) is given by \(g{\mu }_{B}{\widehat{{{{{{\bf{J}}}}}}}}_{i}\), \({\bar{I}}_{{ij}}\) is 3 × 3 interaction matrix, \({g}_{J}\) is the Lande factor and \({\mu }_{B}\) is the Bohr magneton. The usual theoretical approach is then to look for the interaction matrices \({\bar{I}}_{{ij}}\) that stabilize of the observed magnetically ordered structure14, considered as the prime order. The non-zero expectation values of the higher order multipoles that result from the prime order are secondary order parameters. In this paradigm, they are expected to provide small corrections to the Heisenberg Hamiltonian or to the Landau expansion of the free energy.

In this study, we identify a system—the PrO2 dioxide—in which high-rank multipolar interactions are responsible for the occurrence of the magnetic transition and stabilization of the observed magnetic order. We use first-principle-based many-body techniques to calculate the full set of multipolar SEI and then solve the ab initio effective many-body Hamiltonian (1). Our work demonstrates that the experimentally observed magnetic structure of PrO2 is in fact an auxiliary order imposed by an underlying order of high-rank multipolar moments.

Results and discussion

Experimental low-temperature lattice and magnetic structures of PrO2

At high temperatures, the PrO2 compound has a fluorite crystal structure similar to the dioxides of actinides15. At T = 120 K, it undergoes a Jahn-Teller (JT) structural transition into a structure where the oxygen atoms are shifted from their initial positions in the fluoride structure16,17,18, as shown in Fig. 1a. The resulting oxygen “chiral” structural order doubles the fluorite cubic unit cell in the direction perpendicular to the plane of the oxygen shifts16. In the high temperature phase, the ground state multiplet (GSM) 2F5/2 (J = 5/2) of the Pr4+ Kramer’s ion is split by the cubic crystal field into ground state quartet and doublet states (~130 meV). Below 120 K the JT effect further splits the ground state quartet into two doublets, with a broad excited level centered at ~30 meV at low temperatures19. At the Néel temperature TN = 13.5 K, a complex non-collinear antiferromagnetic (AFM) order sets in17, as shown in Fig. 1b. The magnetic unit cell coincides with the distorted crystal unit cell. The orientation of the magnetic moments in the ordered state is coplanar the oxygen shifts, and there are four non-equivalent magnetic planes. The structure can be better understood by considering separately the Pr magnetic moment components parallel to the edges of the crystal lattice17. At each Pr site, the moduli of these components are the same. The AFM order of the large component is just an alternating AFM order of ferromagnetically ordered basal planes corresponding to the propagation vector k = [001]. The small component exhibits a simple AFM order in the basal plane that repeats itself every fourth layer (k = [10\(\tfrac{1}{2}\)]). It has been shown that the JT effect and the observed CF splitting can be readily understood by employing a standard CF model (1)19,20. Moreover, it has also been demonstrated that direct total energy calculations within the framework of ab-initio DFT + U methodology can predict the stabilization of the observed distorted structure21. However, the physical mechanism behind the observed magnetic order (Fig. 1b) remains unclear. Jensen20 has shown that this magnetic order can be stabilized by including three competing Heisenberg interactions of the same order of magnitude between the Pr ions on three distant nearest neighbor (NN) atomic shells. However, the Heisenberg-like model20 is not able to consistently account for the magnitude of exchange splitting of the lowest CF doublet in the ordered phase19. Neither the changes of magnetic structure and structural domain populations under applied field are consistently explained within its framework. Moreover, this model includes a large and ferromagnetic 2nd NN SEI. For a magnetic insulator, where the SEI are expected to be short-ranged and predominantly AFM in character, such a picture seems quite unlikely. As shown below, our calculations do predict the 2nd and 3rd NN SEI to be negligible compared to the NN ones.

a The distorted crystal structure below 120 K. Yellow balls are Pr, the oxygens positions in the ideal cubic fluorite structure (small white circles) and the corresponding oxygen positions in the distorted structure (red balls) are connected by lines representing the shift due to the distotion (the shift’s magnitude is enhanced with respect to the experimental one for clarity); b Observed antiferromagnetic order at 1.5 K, Ref. 17, which is also the ground state predicted from the nearest-neighbour multipolar superexchange interactions calculated in this work (only Pr atoms are shown for clarity); c Predicted antiferromagnetic order in PrO2 under external magnetic field of 5 Tesla applied in the [110] direction (indicated in the plot by the black arrow).

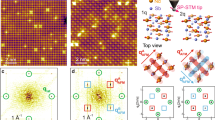

Crystal-field splitting and superexchange interactions

To calculate the full set of parameters required for the effective many-body Hamiltonian (1) for PrO2, we first obtained the paramagnetic CF splitting and composition of the corresponding wave functions for both the cubic fluorite and experimental JT distorted structures using a charge self-consistent DFT + Dynamical Mean-Field Theory (DMFT) technique22,23,24. We treat many-body effects within the Pr 4 f shell in the quasi-atomic Hubbard-I approximation (see Methods). Figure 2a shows the ab-initio-calculated splitting of the energy levels; we obtain 31 and 103 meV for the first and second excited doublets, respectively, in the JT distorted structure. It is in good agreement with the experimental values of ~30 and 130 meV, respectively19. The obtained CF splitting and corresponding wave functions (see Supplementary Note 2) define the single-site CF part of the Hamiltonian (1).

a Calculated CF splliting of the ground state 4f1 multiplet of the Pr4+ ion in the crystal field of PrO2 in the cubic high temperature phase (left) and in the experimental Jahn-Teller distorted phase (right) at low temperatures; b Temperature map of the calculated superexchange interaction matrix \({V}_{{KQ},{K}^{{\prime} }{Q}^{{\prime} }}^{{ij}}\), see Eq. 1, for the next-neighbor Pr-Pr fluorite structure bond (R = [0, 1/2, −1/2]) in the corresponding Cartesian system. Redish colors mark antiferromagnetic (positive) and bluish colors mark ferromagnetic (negative) superexchange interactions. The corresponding numerical values are given in Supplementary Note 3.

The interaction term in Eq. (1) includes 35 multipolar operators for the Pr4+ ion in the GSM (J = 5/2) configuration (listed in Supplementary Note 1). To obtain the full 35 × 35 interaction matrix \({V}_{{KQ},{K}^{{\prime} }{Q}^{{\prime} }}^{{ij}}\), we used the force theorem in the Hubbard-I Approximation (FT-HI)25, see Method for details. Only the NN SEI are important, the second NN SEI are at least an order of magnitude smaller, the longer range SEI are negligible. The calculated NN SEI is presented in graphic form in Fig. 2b, with corresponding numerical values given in Supplementary Note 3. Since the interaction between multipolar moments of different parity (with odd and even K number) must be zero due to time-reversal symmetry, the interaction matrix has a block-wise form. However, the number of symmetry-independent non-zero elements is still quite large, rendering a phenomenological estimation of the SEI quite unfeasible. This is one of the main reasons why contemporary theories of magnetism are typically limited to the Heisenberg interaction term.

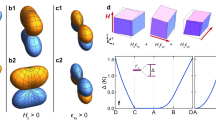

Mean-field magnetic order parameters

Using ab-initio-derived parameters of the full interacting Hamiltonian (Eq. 1), we apply a generalized mean-field approximation (MFA) to study magnetic and multipolar phase transitions in PrO2. To cover all possible orderings within the crystal cell of the distorted structure (Fig. 1), we introduce eight different Pr sublattices (see Method for details). The self-consistent solution of the MFA equations yields a second order phase transition at TN = 21 K where new non-zero order parameters \(\langle {\widehat{O}}_{K(i)}^{Q}\rangle\) emerge. The temperature dependence and schematic pictures of these order parameters are shown in Fig. 3. In agreement with experiment, the large and small magnetic moment components (red and blue arrows in Fig. 3d) correspond to the propagation vectors k = [001], and k = [10\(\tfrac{1}{2}\)], respectively. Hence, in the basal planes of the crystal structure there are two components of the magnetic moment: \({m}_{x}=\langle {\widehat{O}}_{1}^{1}\rangle\), \({m}_{y}=\langle {\widehat{O}}_{1}^{-1}\rangle\) (Fig. 3a). There are also four octupolar moment components \(\langle {\widehat{O}}_{3}^{-3,-{{{{\mathrm{1,1,3}}}}}}\rangle\), and five triakontadipolar components \(\langle {\widehat{O}}_{5}^{-3,-{{{{\mathrm{1,1,3,5}}}}}}\rangle\) (see Fig. 3b and 3c, respectively), resulting in a combined AFM order of odd rank multipoles. The mutual orientation of the magnetic moments in different sub-lattices in the self-consistent solution exactly matches the experimental magnetic order presented in Fig. 1b.

Temperature dependences of the order parameters obtained by solving Eq. 1 in mean-field are shown in (a–c); the corresponding ordered moments are schematically depicted in d–f. a The magnitudes of the two dipole-moment components—principal Mx (propagation vector k = [001]) and secondary My (k = [10\(\tfrac{1}{2}\)])—are indicated by red and blue colors, respectively. The corresponding magnetic structure is shown in d. The magnitude of magnetic octupolar and triakontadipolar on-site moments vs. temperature is shown in b, c; the moments are separated into non-zero projections. The corresponding total octupolar and triakontadipolar moments are schematically depicted in e, f, respectively. The moment expectation values are calculated using the normalized form of the moment operators; the size of moments depicted in e, f is proportional to their absolute magnitude.

Thus, the calculated 1NN multipolar superexchange interactions stabilize the experimental magnetic structure at low temperatures. The derived value of the Neel temperature is overestimated compared to the experimental value15 of 13.5 K, mainly due to the MFA approximation. It is known that MFA produces much higher TN values in cases of competing AFM interactions on the geometrically frustrated fcc lattice. The zero temperature MFA magnetic moments \({m}_{x}=0.49{\mu }_{B}\), \({m}_{y}=0.82{\mu }_{B}\) are in fair agreement to the neutron diffractions estimates17 of \({m}_{x}=0.35{\mu }_{B}\), \({m}_{y}=0.68{\mu }_{B}\). Our MFA magnetic moments are better agreement with experiment as compared to those calculated by Jensen20 from a semi-empirical Heisenberg Hamiltonian. The MFA moments are expected to be somewhat overestimated since we neglect the dynamical Jahn-Teller effect, which tend to reduce the atomic moments in PrO2 compound19; this reduction was estimated20 to be about 5%. A similar reduction of the magnetic moments due to the dynamical Jahn-Teller effect is also characteristic for the isostructural UO2 compound26.

The magnetic order in PrO2 induces an exchange splitting of the CF doublet with the magnitude of 2.7 meV at T = 10 K (75% of experimental TN) as measured by inelastic neutron scattering19. The Heisenberg model of Jensen20 underestimated this splitting by one-third, which was unexpected provided that the same model overestimated the experimental magnetic moments by about 40%. We calculated the splitting of Pr J = 5/2 levels in the magnetically ordered phase using the converged mean field. We obtained the splitting of the ground state doublet (2.64 meV) that matches the experiment at the correspondingly scaled temperature of 15 K (about 75% of theoretical TN). This splitting is predicted by our calculations to reach 3.43 meV at zero temperature.

Magnetic order under applied field

PrO2 also exhibits a complex evolution of the magnetic structure and structural domain distribution under applied magnetic field. An initial application of 5 Tesla field H along the [110] cubic direction was found18 to irreversibly change the distribution of structural domains corresponding to symmetry equivalent JT distortion patterns. Subsequent application of the field in the magnetically ordered phase led to drastic changes in the intensities of magnetic Bragg reflections, which signal significant modifications in the magnetic structure of the preferable structural domain. This field evolution remains poorly understood, since it could not be accounted for within the Heisenberg picture20. We studied the evolution of magnetic structure under \({H||}\)<110> by supplementing the calculated Hamiltonian with the corresponding Zeeman term and solving it in mean-field. We find the field lying in the basal xy plane of the JT structure (Fig. 1a) to be energetically preferable. The calculated magnetic structure under the field H = 5 Tesla is highly unusual (Fig. 1c). The moments of the Pr sites that in the initial structure formed large angles with the field direction keep their large-component propagation vector k = <001> and are aligned orthogonally to the field. The Pr moments initially forming small angles with the field direction are reduced by half and aligned alone the a or b cube edges. This magnetic structure is much more complex than the one initially suggested18 to account for the experimental picture. We find, however, that the predicted structure (Fig. 1c) accounts well for the measured field evolution of Bragg intensities18. Using the experimental setup18 (i. e. assuming \({{{{{\bf{H}}}}}}{||}[0\bar{1}1]\)) we calculated the intensities of the Bragg peaks. In agreement with the experiment18, the (011) Bragg peak is predicted to disappear under applied field, while the (100) peak intensity is almost unchanged and the (211) one diminishes by about 10% (see Supplementary Note 5). We note, however, that our calculations predict a too rapid decay of the (011) reflex with increasing field compared to experiment; this might stem from additional anisotropy contribution due to the dynamic JT effect being neglected in our calculations.

Multipolar superexchange as the driving force for PrO2 magnetic order

As shown above, the fully calculated SEI Hamiltonian (1) provides a faithful description for the properties of magnetically ordered PrO2. Since a very large number terms are included into this Hamiltonian, it is important to understand the impact of different interactions on the complex magnetic and multipolar order in PrO2. To that end, we solved MFA equations only with standard Heisenberg magnetic interactions (dipolar interactions) included. Thus, we used only the dipole-dipole block (K = 1) of calculated SEI, \({\sum }_{i,j}{\sum }_{Q{Q}^{{\prime} }}{V}_{1Q,1{Q}^{{\prime} }}^{{ij}}{\widehat{O}}_{1(i)}^{Q}{\widehat{O}}_{1(\,j)}^{{Q}^{{\prime} }}\), disregarding all higher order multipolar interactions. This can be recast in the standard form \(\mathop{\sum}\nolimits_{i,j}{\widehat{{{{{{\bf{J}}}}}}}}_{i}{\bar{I}}_{{ij}}{\widehat{{{{{{\bf{J}}}}}}}}_{j}\) of a Heisenberg-like interaction between dipole magnetic moments. As expected from earlier analyses provided by Jensen20, solving this Heisenberg-like model in MFA, we derived a wrong AFM order. More importantly, the calculated Neel temperature was found to be just 0.2 K, two orders of magnitude smaller than the ordering temperature obtained with the full calculated SEI matrix.

Thus, the dominant contribution to the ordering in PrO2 must be due to high-order multipolar SEIs. We verified this explicitly, by setting in Eq. 1 all SEI involving dipole operators to zero. By solving Eq. 1 with the dipole-moment contribution completely suppressed, we find essentially the same magnetic structure with the magnitude of magnetic moment reduced by about 6% and TN = 18 K. Hence, the actual contribution of dipole moments into the formation of ordered structure is insignificant. This can be further confirmed by evaluating the contributions of various SEI, \({V}_{{KQ},{K}^{{\prime} }{Q}^{{\prime} }}^{{ij}}{\langle {\widehat{O}}_{K}^{Q}\rangle }_{\!i}{\langle {\widehat{O}}_{{K{{\hbox{'}}}}}^{{Q{{\hbox{'}}}}}\rangle }_{\!j}\), into the magnetic ordering energy; this analysis shows that the leading contributions are due to octupolar and trikontadipolar SEI (see Supplementary Note 4). This means that the observed magnetic order in PrO2 is in fact induced by multipolar interactions, with the actual contribution by dipole moments being quite negligible.

To understand the mechanism through which the secondary dipole order is induced we determined among the J = 5/2 moments those that are active within the lowest CF doublet. Since the JT splitting of 30 meV between this doublet and the first excited one (Fig. 2a) is an order of magnitude larger than the exchange splitting of about 3 meV, one may assume that the admixture of excited CF levels by the exchange field is negligible. The degrees-of-freedom of the lowest CF doublet can be represented by a pseudo-spin-1/2 variable \(\tau\) with the two Kramers’ partners being the two eigenstates of \({\tau }_{z}\). The physical content of these four spin-1/2 operators \({\tau }_{\alpha }\)– the identity \({\tau }_{I}\) as well as \({\tau }_{x}\), \({\tau }_{y}\), and \({\tau }_{z}\) – is determined by upfolding them into the full J = 5/2 as \({\widetilde{\tau }}_{\alpha }=P{\tau }_{\alpha }{P}^{{{\dagger}} }\), where the columns of the projection matrix \(P\) are the CF doublet eigenstates in the J = 5/2 basis. Subsequently expanding \({\widetilde{\tau }}_{\alpha }\) into the J = 5/2 Stevens operators \({\widehat{O}}_{L}^{M}\) one finds

where for brevity we introduce a shorthand notation \({S}_{3}^{\alpha }\) (\({S}_{5}^{\alpha }\)) for normalized superpositions of octupole (trikontadipole) Stevens operators contributing to a given \({\tau }_{\alpha }\). Analogous expression is found for \({\tau }_{z}\), which includes only \(z\)-projections of the magnetic operators and thus, due to a strong planar anisotropy, plays no role in the magnetic order. The identity \({\tau }_{I}\) is formed by time-even J = 5/2 operators corresponding to the CF; thus, it also plays no role.

One sees that any doublet-space density matrix for an arbitrary planar order, \(\rho ={\tau }_{x}\langle {\tau }_{x}\rangle +{\tau }_{y}\langle {\tau }_{y}\rangle\), will include about the same total contributions due to dipoles, octupoles and trikontadipoles, since their respective contributions to both \({\tau }_{x}\) and \({\tau }_{y}\) are very similar. The strong JT splitting thus entangles magnetic operators of different ranks together; this is how dominating multipolar SEIs induce the secondary dipole order in PrO2. Due to this entanglement, separating the order parameters presented in Fig. 3 into primary and secondary ones does not imply any difference in their temperature dependence. Their temperature dependences (Fig. 3d, 3e, and 3f), when normalized to the corresponding zero-temperature values, collapse onto the same curve (see Supplementary Fig. 1). However, one still may ask the physically relevant question: which interactions drive the magnetic order of PrO2? Our direct calculations convincingly show that those interactions are multipolar. Among various multipolar order parameters shown in Fig. 3, the octupoles \({\widehat{O}}_{3}^{1}(x{z}^{2})\) and trikontadipoles \({\widehat{O}}_{5}^{1}(x{z}^{4})\), which correspond to a magnetic density oblate along the secondary component (\(y\)) direction, provide the leading contribution to the ordering energy (see Supplementary Note 4).

Conclusions

In general, there is no physical reason why dipolar inter-site exchange interactions should dominate higher-order multipolar ones in heavy ions with unquenched orbital moments. This work demonstrates that the prevailing paradigm, which suggests that observed magnetic order arises solely from interactions between the observed order parameters, can be violated in real systems. A possible prominent role of the higher order multipolar interactions in PrO2 has been suggested previously3,20. However, here, we show that those multipolar SEI are not simply significant, but that they fully determine the physics of the magnetic behavior in PrO2. Complex combined order parameters entangling both magnetic and multipolar interactions, uncovered here in the case of PrO2, could be rather common in localized f-electron systems. Consequently, the analysis of magnetic structures in f-electron materials should incorporate multipolar degrees of freedom from the onset, even in cases where only dipolar moments are experimentally detected.

Methods

Ab initio calculations

We calculated the electronic structure of PrO2 within the DFT + DMFT framework using the experimental lattice structures of both the high-temperature cubic structure and the “chiral” JT-distorted body-centered tetragonal one17. In these calculations we employed the full-potential DFT code Wien2k27 and the charge self-consistent DMFT implementation provided by “TRIQS” library24,28. We treat Pr 4 f states within the Hubbard-I (HI) approximation. We employ the Wien-2k basis cutoff \({R}_{{MT}}{K}_{\max }\) = 8, local density approximation, and include spin-orbit. 3000 and 800 k-points in the full Brillouin zone were employed in the cubic and tetragonal cases, respectively. The on-site Coulomb repulsion for Pr 4 f shell was parametrized by U = F0 = 6.5 eV and JH = 0.73 eV; these values agree with previous applications of DFT + HI calculations to Pr compounds29,30. The projective 4 f Wannier orbitals were constructed from the 4f-like Kohn-Sham (KS) bands within the range [−1:2.7] eV with respect to the KS Fermi level. The fully localized limit double counting was calculated using the nominal N = 1 occupancy of Pr4+ 4f.

The CF splitting and states for the Pr 4 f shell were obtained from converged DFT + HI calculations.

Within our self-consistent DFT + HI calculations we average the Boltzmann weights of CF eigenstates within the GSM, which is shown31 to suppress the contribution of the self-interaction error of DFT into the CF splitting. This approach has been successfully applied in calculations of the CF splitting in a number of rare-earth-based intermetalics and insulators32,33,34. As it was demonstrated31, the CF splitting calculated with this method exhibits a very weak dependence on the values of U and JH. The reason is that CF is weak in rare-earth ions and acts mainly within the GSM, while U and JH define the splitting between multiplets corresponding either to different shell occupancies or to different spin/orbital quantum numbers. Thus, U and JH only weakly, through inter-multiplet mixing effects, influence the composition of the GSM.

The SEIs for all Pr-Pr bonds within several first correlation shells were obtained using the FT-HI method25 applied as a postprocessing of the converged DFT + HI electronic structure of the cubic structure. We previously used the FT-HI method to calculate superexchange interactions for the actinide dioxides UO2 and NpO228,35. Only the SEIs coupling the lowest CF levels in the cubic structure - triplet and quartet, respectively – were calculated for those systems. We found this strategy to be not appropriate here since the JT distortion is rather large in PrO2 strongly mixing the cubic GS \({\varGamma }_{8}\) and excited \({\varGamma }_{6}\) levels. Therefore, we evaluated the SEI interaction matrix \({V}_{{KQ},{K}^{{\prime} }{Q}^{{\prime} }}^{{ij}}\) for the full J = 5/2 multiplet and explicitly kept the CF term in the Hamiltonian (1).

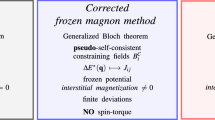

Mean-field calculations

We solved the many-body effective Hamiltonian (1) in the MFA considering all possible orders realizable within the distorted unit cell of PrO2 (Fig. 1a). To this end we Introduce eight different Pr sublattices, chosen in a way to exclude any intra-sublattice coupling, and thus allowing for all possible type of ordering with given periodicity. For a mean-field Hamiltonian

we obtained a set of coupled mean-field equations for each of the 35 multipolar moments \(\left\langle {\widehat{O}}_{K(i)}^{Q}\right\rangle\) on each \({i}^{{th}}\) sub-lattice, resulting in a system of 280 equations:

which we solve iteratively.

Let us note, that ignoring the exchange induced mixing of the excited states into the lowest doublet, one can reduce the problem of the phase transition in PrO2 to an anisotropic Heisenberg model in the pseudo-spin ½ space introduced above, where all the relevant interactions will be described by usual dipole-dipole interactions in the pseudospin space. However, all physical multipolar interactions will be entangled in such pseudo-spin exchange interactions.

Calculations of neutron-scattering intensities

We calculated the intensities of neutron Bragg peaks using the beyond-dipole-approximation approach11. Namely, the intensity of elastic scattering \(I({{{{{\bf{q}}}}}})\) at the scattering vector q reads

where \(\langle {O}_{\mu }({{{{{\bf{q}}}}}})\rangle =\mathop{\sum}\nolimits_{i}{\langle {O}_{\mu }\rangle }_{i}{e}^{{{{{{\rm{i}}}}}}{{{{{\bf{q}}}}}}{{{{{{\bf{R}}}}}}}_{{{{{{\boldsymbol{i}}}}}}}}\) is the Fourier transform of the order parameter \({\langle {O}_{\mu }\rangle }_{i}\) for the magnetic multipole \(\mu \mathop{\scriptstyle{{{{{\mathrm{def}}}}}}}\limits_{=}\,[{KQ}]\) at site i, \({{{{{{\bf{R}}}}}}}_{{{{{{\boldsymbol{i}}}}}}}\) is the coordinate of this site within the magnetic unit cell, \({F}_{\mu \alpha }({{{{{\bf{q}}}}}})\) is the form-factor for the multipole \(\mu\) and \(\alpha =x,y,\) \({or}\) \(z\), \(\widehat{{{{{{\bf{q}}}}}}}\) = \({{{{{\bf{q}}}}}}{{{{{\boldsymbol{/}}}}}}{{{{{\bf{|q|}}}}}}\). The form-factors \({F}_{\mu \alpha }({{{{{\bf{q}}}}}})\) were calculated by evaluating matrix elements of the neutron scattering operator36 in the Pr J = 5/2 basis and expanding the resulting matrix in the basis of J = 5/2 magnetic multipole operators37 as detailed in Supplementary of11. To compute the matrix elements, we used the radial integrals \(\left\langle {j}_{l}\right\rangle\) calculated38 for Pr3+, since this data for Pr4+ are not available in the literature. In spite of the large magnitudes of high-rank multipolar order parameters in PrO2, their contribution to the Bragg peaks intensities that we calculated was found to be negligible due to their small form-factors. The spectroscopical probes could be able to distinguish purely dipole moments from the pseudo-spin moments composed of multipolar ones. As it was shown previously11, high-rank multipoles have very different neutron form-factors peaked at large momentum transfers and these form factors can be evaluated. In the case of PrO2, a rather large magnitude of dipole moment renders the contribution of multipole moments insignificant for the low-q Bragg peaks that we consider.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study as well as methodological details required to reproduce these data are included in the article text, Supplementary Information and cited references. Additional data related to this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Jensen, J. & Mackintosh, A. R. Rare Earth Magnetism. (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1991).

Lander, G. H., 1993: Neutron elastic scattering from actinides and anomalous lanthanides in Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths (eds. Gschneider, K. A., Eyring, L, Lander, G.H. & Choppin. G.R) Vol. 17, 635–709 (Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, 1993).

Santini, P. et al. Multipolar interactions in f -electron systems: the paradigm of actinide dioxides. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 807 (2009).

Santini, P., Carretta, S., Magnani, N., Amoretti, G. & Caciuffffo, R. Hidden order and low-energy excitations in NpO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 207203 (2006).

Mydosh, J. A. & Oppeneer, P. M. Colloquium: hidden order, superconductivity, and magnetism: the unsolved case of URu2Si2. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1301 (2011).

Haule, K. & Kotliar, G. Arrested Kondo effect and hidden order in URu2Si2. Nat. Phys. 5, 796 (2009).

Chandra, P., Coleman, P. & Flint, R. Hastatic order in the heavy-fermion compound URu2Si2. Nature 493, 621 (2013).

Suzuki, M.-T., Ikeda, H. & Oppeneer, P. M. First-principles theory of magnetic multipoles in condensed matter systems. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 87, 041008 (2018).

Lu, L. et al. Magnetism and local symmetry breaking in a Mott insulator with strong spin orbit interactions. Nat. Commun. 8, 14407 (2017).

Maharaj, D. D. et al. Octupolar versus Neel order in cubic 5d2 double perovskites. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 087206 (2020).

Pourovskii, L. V., Fiore Mosca, D. & Franchini, C. Ferro-octupolar order and low-energy excitations in d2 double perovskites of osmium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 237201 (2021).

Fiore Mosca, D. et al. Interplay between multipolar spin interactions, Jahn-Teller effect, and electronic correlation in a Jeff = 3/2 insulator. Phys. Rev. B 103, 104401 (2021).

Altshuler S. A. & Kozyrev, B. M. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance in Compounds of Transition Elements, (2nd edn. Wiley, 1974).

McHenry, M. & Laughlin, D. E. Theory of Magnetic Phase Transitions, Characterization of Materials (Wiley, 2012).

Kern, S., Loong, C.-K., Faber, J. Jr & Lander, G. H. Neutron scattering investigation of the magnetic ground state of PrO2. Solid State Commun. 49, 295 (1984).

Webster, C. H. et al. Influence of static Jahn-Teller distortion on the magnetic excitation spectrum of PrO2: a synchrotron x-ray and neutron inelastic scattering study. Phys. Rev. B 76, 134419 (2007).

Gardiner, C. H. et al. Cooperative Jahn-Teller distortion in PrO2. Phys. Rev. B 70, 024415 (2004).

Gardiner, C. H., Boothroyd, A. T., McKelvy, M. J., McIntyre, G. J. & Prokeš, K. Field-induced magnetic and structural domain alignment in PrO2. Phys. Rev. B 70, 024416 (2004).

Boothroyd, A. T. et al. Localized 4f states and dynamic Jahn-Teller effect in PrO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 2082 (2001).

Jensen, J. Static and dynamic Jahn-Teller effects and antiferromagnetic order in PrO2: a mean-field analysis. Phys. Rev. B 76, 144428 (2007).

Tran, F., Schweifer, J., Blaha, P., Schwarz, K. & Novàk, P. PBE + U calculations of the Jahn-Teller effect in PrO2. Phys. Rev. B 77, 085123 (2008).

Georges, A., Kotliar, G., Krauth, W. & Rozenberg, M. J. Dynamical mean-field theory of strongly correlated fermion systems and the limit of infinite dimensions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 68, 13–125 (1996).

Anisimov, V. I., Poteryaev, A. I., Korotin, M. A., Anokhin, A. O. & Kotliar, G. First-principles calculations of the electronic structure and spectra of strongly correlated systems: dynamical mean-field theory. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 9, 7359 (1997).

Aichhorn, M. et al. TRIQS/DFTTools: a TRIQS application for ab initio calculations of correlated materials. Comput. Phys. Commun. 204, 200 (2016).

Pourovskii, L. V. Two-site fluctuations and multipolar intersite exchange interactions in strongly correlated systems. Phys. Rev. B 94, 115117 (2016).

Ippolito, D., Martinelli, L. & Bevilacqua, G. Dynamical Jahn-Teller effect on UO2. Phys. Rev. B 71, 064419 (2005).

Blaha, P. et al. WIEN2k, An augmented Plane Wave + Local Orbitals Program for Calculating Crystal Properties (Karlheinz Schwarz, Techn. Universität Wien, 2018).

Parcollet, O. et al. TRIQS: A toolbox for research on interacting quantum systems. Computer Phys. Commun. 196, 398 (2015).

Locht, I. L. M. et al. Standard model of the rare earths analyzed from the Hubbard I approximation. Phys. Rev. B 94, 085137 (2016).

Galler, A. & Pourovskii, L. V. Electronic structure of rare-earth mononitrides: quasiatomic excitations and semiconducting bands. N. J. Phys. 24, 043039 (2022).

Delange, P., Biermann, S., Miyake, T. & Pourovskii, L. Crystal field splittings in rare earth-based hard magnets: an ab initio approach. Phys. Rev. B 96, 155132 (2017).

Pourovskii, L. V., Boust, J., Ballou, R., Gomez Eslava, G. & Givord, D. Higher-order crystal field and rare-earth magnetism in rare-earth–Co5 intermetallics. Phys. Rev. B 101, 214433 (2020).

Boust, J. et al. Ce and Dy substitutions in Nd2Fe14B: Site-specific magnetic anisotropy from first principles. Phys. Rev. Mater. 6, 084410 (2022).

Bernáth, B. et al. Massive magnetostriction of the paramagnetic insulator KEr(MoO4)2 via a single-ion effect. Adv. Electron. Mater. 8, 2100770 (2022).

Pourovskii, L. V. & Khmelevskyi, S. Hidden order and multipolar exchange striction in a correlated f-electron system. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2025317118 (2021).

Lovesey, S. W. Theory of Neutron Scattering from Condensed Matter (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1984).

Shiina, R., Sakai, O. & Shiba, H. J. Magnetic form factor of elastic neutron scattering expected for octupolar phases in Ce1-xLaxB6 and NpO2. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 76, 094702 (2007).

Freeman, A. J. & Desclaux, J. P. Dirac-Fock studies of some electronic properties of rare-earth ions. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 12, 11 (1979).

Acknowledgements

L.V.P. acknowledges support from European Research Council Grant ERC-319286-“QMAC” and the computer team at CPHT. S.K. acknowledges TU Wien Bibliothek for financial support through its Open Access Funding Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.K. performed mean-field calculations, determined ordered states, and wrote the initial version of the manuscript. L.V.P. carried out calculations of crystal field, superexchange interactions, and neutron scattering intensities. Both authors contributed equally to the analysis of the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks Paolo Santini, Andrew Boothroyd, Ryousuke Shiina, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khmelevskyi, S., Pourovskii, L.V. Non-collinear magnetism driven by a hidden multipolar order in PrO2. Commun Phys 7, 12 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-023-01503-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-023-01503-7

This article is cited by

-

Hidden orders in spin–orbit-entangled correlated insulators

Nature Reviews Materials (2025)