Abstract

Active matter systems display collective behaviors that are impossible in thermodynamic equilibrium. One such feature, observed in in dense active matter systems is the appearance of long-range velocity correlations without explicit aligning interaction. However, the conditions for the appearance of these correlations remain largely unexplored. Here we show that such long-range velocity correlations can also be generated in a dense athermal passive system by the inclusion of a very small fraction of active Brownian particles. We develop a continuum theory to explain the emergence of velocity correlations generated via such active dopants. We validate the predictions for the effects of magnitude and persistence time of the active force and the area fractions of active and passive particles using extensive Brownian dynamics simulation of a canonical active-passive mixture. Our work decouples the roles that density and activity play in generating long-range velocity correlations in such exotic non-equilibrium steady states.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Active matter systems are one of the best-known examples of non-equilibrium systems and are famous for their fascinating collective behaviour across a diverse range of length and time scales1,2, from the cytoskeleton to bacterial colonies, tissues, flocks of birds to animal herds.

Systems of active Brownian particles (ABP), i.e., particles exhibiting self-propulsion, are a canonical example of active matter3,4,5,6,7. These systems exhibit two types of non-equilibrium pattern formation: in the presence of aligning interactions between the directions of the self-propelled motion of the particles, they show flocking, i.e., collective directed motion of groups of such particles8,9. In the absence of such aligning interactions, they exhibit motility-induced phase separation (MIPS), crucially without the need for attractive interactions3,4,5. It is important to note that this phase separation is not associated with any macroscopic order in the orientation of the self-propulsion directions of the particles. With external driving, on the other hand, such order can appear, see e.g., ref. 10.

Very recently it has been discovered that while systems without aligning interactions show no macroscopic orientational ordering, there are spectacularly large spatial structures in the instantaneous velocity field, especially within the dense phase created by motility-induced phase separation (MIPS)11,12,13,14,15. It has been shown using both analytical calculations and numerical models (and confirmed in experiments in dense tissues14) that in such a scenario, a dense assembly of active particles generates long-range velocity correlations in the limit of large persistence time (defined as the duration for which the active or propulsion force of a particle maintains its current direction before altering its course). The corresponding correlation length grows as a power law \(\sqrt{{\tau }_{p}}\) with increasing persistence time τp11,12,13,14,15. The emergence of such non-equilibrium velocity correlation has always been attributed to a (highly persistent) dense active matter system and thus taken to require a high density of active particles.

These results raise the question of whether the above two conditions, of high density and high activity, can be decoupled. In particular, could long-range velocity correlations be generated in a dense system of passive particles, by introducing activity only through a small fraction (e.g., much lower than the percolation density) of active particles? A related question of interest is how ordered non-equilibrium states are affected by the inclusion of defect particles (e.g., static defects or motile non-aligning agents known as dissenters) that do not participate in the processes that induce the order. The role of both quenched16,17,18 and annealed16,18,19 disorder in the context of Vicsek-like models has been investigated very recently and it has been shown that the presence of both types of disorder tends to destroy the ordered flocking state16,17,18,19. Our work explores a similar line of questions, but in a system where long-range velocity correlations appear without any explicit alignment interaction. We ask in particular whether the long-range order in the instantaneous velocity field seen in such systems is stabilised or destabilized by the inclusion of a (potentially large) fraction of passive particles.

Motivated by the above questions, in this paper, we study mixtures of active and athermal passive particles to explore whether the inclusion of passive particles enhances or suppresses local orientational order and to see whether we can decouple the roles of activity and density in generating long-range velocity correlations. Using extensive particle-based simulation of an active-passive mixture, we demonstrate that velocity ordering is enhanced by an increasing density of passive particles, and show that long-range velocity correlations can be generated in an athermal passive medium by a tiny fraction of active insertions (dopants) as long as the medium is dense enough. We also construct an analytical theory to explain the physics of velocity correlations in a dense passive medium with active dopants. Our continuum theory predicts that the amplitude of the velocity correlations is proportional to f 2 where f is the magnitude of the propulsion force acting on each active particle, proportional to \({\tau }_{p}^{-3/4}\) where τp is the persistence time of the active particles, and proportional to the density of active particles ϕa. The continuum theory also predicts that the correlation length ξL only depends on τp, as \(\sqrt{{\tau }_{p}}\)11,12,13,14,15, not on the active forcing magnitude f. We verify these theoretical predictions by performing further targeted simulations. The explicit form of the correlation function that we derive theoretically decouples the roles that density and activity play in generating long-range velocity correlations in a non-equilibrium steady state. This insight will be useful in understanding long-range ordering in e.g., dense passive colloidal systems driven by a few self-propelled Janus colloids, or assemblies of dead bacteria churned up by few living ones.

Methods

Particle-based model

We consider a binary mixture20 of athermal passive particles and active Brownian particles (ABP)3,4,5,6,7 moving in two dimensions and occupying area fractions of ϕp and ϕa, respectively. The dynamical evolution of the particle positions is described by the overdamped equations of motion:

where ri is the position vector of the i-th particle and γ is the constant drag coefficient governing the friction force acting on each particle. The factor \({\Delta }_{i}({{{\mathcal{A}}}})\) (Δi = 1 for the active particles and Δi = 0 for the passive particles) restricts the active forces fni to the particles in the subset \({{{\boldsymbol{{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}}}}\) that contains all active particles. Note that there is no thermal noise in the equation of motion of the passive particles: without active dopants they will collectively go to the nearest potential energy minimum. In the presence of active particles, on the other hand, the activity of the latter drives the passive particles to exhibit diffusion-like motion; see the Supplementary Note 4. The orientation vectors of the active forces are \({{{{\bf{n}}}}}_{i}=(\cos {\theta }_{i},\sin {\theta }_{i})\), and the orientation angles θi of the active forcing follow the dynamics

where the noise ζi has zero mean and time correlations \(\langle {\zeta }_{i}(t){\zeta }_{j}({t}^{{\prime} })\rangle ={\delta }_{ij}\delta (t-{t}^{{\prime} }).\) In Eq. (2), τp is the persistence time. All particles in the system interact only through steric interactions described by the forces \({\tilde{{{{\bf{F}}}}}}_{i}=-{\nabla }_{i}U\) where U is a repulsive WCA (Weeks-Chandler-Anderson) interaction potential21 (see the Supplementary Note 1 for the details of the potential).

Results and discussion

Velocity correlations in active–passive mixture

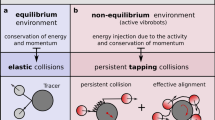

First we reproduce the long-range velocity correlations in a completely active system (see Fig. 1a for a schematic and Fig. 1c for a snapshot of the system showing the long-range ordering of the instantaneous velocities). This effect has been reported before in the context of different dense active matter systems, both in simulations and in experiments11,12,13,14,15. Here we want to explore a different scenario (see Fig. 1b for a schematic) and test whether a dense passive system that is driven by just a few active particles can show similar ordering. Indeed, Fig. 1d shows remarkably similar order in such a dense passive system (ϕp = 0.69) that is driven by a very small fraction (ϕa = 0.01) of active Brownian particles. To explore this further, we also ran simulations for combinations of different fractions of active and passive particles (see Fig. 2 for snapshots and Supplementary Movie 1). Strong local velocity correlations (in terms of the orientation of the velocity field; its magnitude decreases with increasing density, as described below) are seen to emerge as long as the total density ϕtot = ϕa + ϕp is high enough and there exists a non-zero fraction of active particles (Movies with a very small fraction of active particles and varying densities of passive particles are shown in Supplementary Movies 2–5, see also Supplementary Note 2). To get a better understanding of this velocity ordering in an active-passive mixture we developed a continuum theory that we describe in the next paragraph.

a A dense assembly of active particles, and b a dense mixture of active (blue) and athermal passive(red) particles. Snapshots of the system with each particle coloured according to the orientation of its instantaneous velocity vector, for c ϕa = 0.7 (ϕp = 0), d ϕa = 0.01, ϕp = 0.69; both systems show strong emergent velocity correlations. ϕa is the density of active particles, and ϕp is the density of passive particles.

Snapshot of the system (binary mixture of active and athermal passive particles) for various combinations of values of the area fractions of active and passive particles, ϕa and ϕp, respectively. The snapshots at the bottom right corner show that a small fraction of active inclusions can cause long-range velocity correlations in a dense athermal and almost entirely passive system. Note that the representation focuses on the orientational correlations of the velocity field; variations of velocity magnitude are not shown.

Theory

To derive the correlation of the continuum velocity field of the system, we extend the approach used by Henkes et al. for a dense active system14 to the case of a passive system with active dopants.

We describe the dynamics of the system with the continuum equation

in which ρ = 4ϕtot/πσ2 represents the particle number density, while u(r, t) signifies the displacement field of the entire medium, irrespective of whether the medium comprises active or passive particles. γ denotes the friction coefficient, σ is the diameter of the particles and \(\hat{\Sigma }\) represents the stress tensor. Taking the Fourier transform of Equation (3), with the stress taken as arising from isotropic elasticity with bulk modulus B and shear modulus μ, we obtain:

Here D(q) is the Fourier space dynamical matrix and defined as

Our theory is suitable for describing a dense athermal material that is driven by a small fraction of self-propelled particles. We consider the entire collection of the particles as a dense medium having a smooth velocity field, with the active particles as random point-like defects that are the sources of a force density of the form

for the i-th active particle. Here f is the magnitude of the propulsion force acting on each active particle as before, and ni is the unit vector associated with the orientation of this active force. We now assume that for sufficiently high density, the displacements of all particles remain small, including those of the active particles, so that the positions ri(t) at which the active forces Fi(r, t) act can be taken as fixed to leading order. We can then evaluate the correlation between the force densities from active particles i and j in Fourier space (q, ω) as

where the frequency dependence arises from the dynamics of the active force orientation ni(t)14. We then sum over all the particles (over the indices i and j) and also over the probability distribution of the active particles’ positions ri, which we take as uniform, to arrive at the total force density correlator

where Na is the number of active particles and N the total number of particles in the system; ρ is the particle number density as before. (In the continuum theory expressions derived in Ref. 14, the friction coefficient, there denoted ζ, has to be read as the friction coefficient density, i.e., γρ in our notation. Note that ρ is written as 1/a2 in ref. 14). One can now, following ref. 14, solve Eq. (4) to express u(q, ω) in terms of the force density F(q, ω), and determine the correlator \(\langle {{{\bf{u}}}}({{{\bf{q}}}},\omega )\cdot {{{\bf{u}}}}({{{{\bf{q}}}}}^{{\prime} },{\omega }^{{\prime} })\rangle\) using Eq. (8). As the local velocity \({{{\bf{v}}}}=\dot{{{{\bf{u}}}}}\) has Fourier transform −iωu(q, ω), the velocity statistics are then also determined and integration over frequency gives the equal time (Fourier space) velocity correlator

and from this finally the real space velocity correlation function

We refer to the Supplementary Note 3 for the full calculation, which leads to the following form of the correlation function:

where r is the spatial distance. The correlation function is characterized by two correlation lengths, ξL and ξT, defined as \({\xi }_{T}={\left(\frac{\mu {\tau }_{p}}{\gamma \rho }\right)}^{1/2}\) and \({\xi }_{L}={\left(\frac{(B+\mu ){\tau }_{p}}{\gamma \rho }\right)}^{1/2}\) where B and μ are the bulk and the shear modulus of the system14. At large distances (and for B ≫ μ, which is expected close to the jamming transition), the term with the larger length scale ξL is dominant and the correlation function can be approximated as

The moduli B and μ are expected to depend only on the total area fraction ϕtot = ϕa + ϕp of active and passive particles (though we do not have their explicit dependence for our system). Ideally, we could determine the correlation length from the simulations and compare theory and simulations with that numerically determined correlation length. However, this is only possible if the simulated systems are sufficiently large, so that indeed one length scale is dominant and the single-length scale approximation of Eq. (12) provides an accurate description, which is not fully the case in our simulations. For the system sizes we simulated, we could not accurately determine two length scales numerically from the correlation function. However, since the unknown factors in the correlation lengths depend only on the total area fraction, and not on the other parameters, even in the absence of such explicit expression, we have a testable prediction about the equal time velocity auto correlation function from our continuum theory in terms of the control parameters f, τp, ϕa, ϕp etc. These predictions also remain the same if the approximation in Eq. (12) is not valid, as both correlation lengths show the same scaling with f and τp.

Comparison with theory

To validate the predictions of our theory we ran further simulations to test explicitly the effects of varying active force magnitude f, persistence time τp, and area fractions of active ϕa and passive particles ϕp, and compared the correlation functions from those simulations with those calculated using the continuum theory.

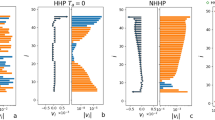

Eq. (12) predicts that the prefactor of the velocity-velocity spatial auto-correlation function will scale as f 2 when we vary the active force magnitude f, without any associated variation in the correlation length. Therefore the values of the scaled auto-correlation function C(r)/f 2 are expected to collapse into a single curve for different values of the active forcing f as long as the other parameters are kept constant. Note that is prediction is obtained both from the approximation in Eq. (12) and from the full expression in Eq. (11). Figure 3a clearly shows that the scaled correlation functions for different magnitudes of the active force do indeed collapse on top of each other. In Fig. 3b we show an estimate of the correlation length (ξL, obtained by fitting the correlation function with the single-exponential approximation from Eq. (12) for large r) as a function of the active force f for different persistence times (τp), which provides further evidence that the correlation length is independent of the magnitude of the active force when the persistence time is kept constant.

a Scaled velocity-velocity spatial auto correlation C(r) as a function of spatial distance r, for different active force magnitudes f as indicated in the legend, and persistence time τp = 3 b The correlation length ξL as a function of the active force f for different persistence times τp as shown; the plot demonstrates that, at fixed persistence time, the correlation length is independent of the magnitude of the active force. The simulations for this figure were conducted at densities ϕa = 0.01 and ϕp = 0.94 of active and passive particles, respectively. To accurately estimate the correlation length, we conducted 50 simulations with random initial configurations, collected 2500 snapshots in a stationary state from these simulations, and averaged the results to ensure precision. The error bars show the standard error of the mean.

To shed light on the effects of the persistence time scale we vary τp next, keeping both area fractions (ϕa, ϕp) and the active forcing magnitude f constant. Our continuum theory (see Eq. (12)) suggests that the prefactor of the velocity-velocity spatial auto-correlation function (taken as a function of r/ξL) scales as \({\xi }_{L}^{-2} \sim {\tau }_{p}^{-1}\), due to the dependence of ξL on τp. Figure 4a shows that the simulation data points for different persistence times τp for a given active force f fall close to a single curve once we scale C(r) appropriately, i.e., C by τp and r by ξL. Figure 4b further indicates that the correlation length ξL grows as the square root of persistence time τp regardless of the magnitude of the active force (to emphasize the importance of persistence time τp, we have shown in Fig. S1 that if the system is at high density and the active particles do not have sufficient persistence time, they cannot produce long range velocity correlations.). This is also consistent with our theory and earlier studies11,12,13,14,15. Importantly, within our theory, this scaling holds for both correlation lengths, ξL and ξT, so it can even be expected to be valid if the correlation length obtained from the fit reflects a combination of the two, e.g., if the simulated system is not large enough for the approximation Eq. (12) to be valid. We note that this qualitative scaling can be obtained from the simple argument that velocity correlations will be dominated by elastic modes whose relaxation rate (μ + B)q2/(γρ) is of the order of the inverse persistence time 1/τp, giving a length scale of \(1/q \sim {[(\mu +B){\tau }_{p}/(\gamma \rho )]}^{1/2}={\xi }_{L}\).

a The scaled equal-time velocity-velocity correlation as a function of spatial distance r for different persistence times τp as indicated, for active force magnitude f = 0.25. b The correlation length ξL as a function of the persistence time τp for different values of the active force magnitude f. The plot shows that the correlation length ξL grows as a power law (with exponent \(\frac{1}{2}\), black dashed line) with the persistence time τp, and this behaviour is independent of the magnitude of the active force f, which is shown in the legend. The simulations for this figure were conducted at densities ϕa = 0.01 and ϕp = 0.94 of active and passive particles, respectively. To accurately estimate the correlation length, we conducted 50 simulations with random initial configurations, collected 2500 snapshots in a stationary state from these simulations, and averaged the results to ensure precision. The error bars show the standard error of the mean.

Though our theory primarily describes the velocity correlation in the dense limit of the system (typically above the jamming area fraction) it can also be applied at moderate density. The system, driven by activity, may then still form large clusters with high local density to which our theory can be applied, even when the overall density is below the jamming threshold. To test this hypothesis we analysed the velocity correlation in a simulation performed at area-fraction ϕtot = 0.6 with ϕa = 0.2 and ϕp = 0.4 and f = 1.0 for various values of τp: we do see a \(\sqrt{{\tau }_{p}}\) dependence of the velocity correlation length in this case as well (see Fig. 5). In addition, we examined the mean squared displacement of passive particles at different densities and for varying magnitudes of persistence time and active force, as shown in Supplementary Note 4 and Supplementary Fig. S2.

a Scaled equal-time velocity auto-correlation as a function of spatial distance r for different persistence times τp, with active force magnitude f = 1.0, at densities ϕa = 0.2 and ϕp = 0.4 of active and passive particles, respectively. b Correlation length ξL as a function of persistence time τp extracted from the data in a. Black dashed line shows \(\sqrt{\tau }\). To accurately estimate the correlation length, we conducted 50 simulations with random initial configurations, collected 2500 snapshots in a stationary state from these simulations, and averaged the results to ensure precision. The error bars show the standard error of the mean.

We next explore the dependence on the area fractions of passive and active particles ϕp and ϕa, respectively, while keeping the active forcing parameters (f, τp) constant. The theory suggests that apart from the linear dependence on the fraction of active particles ϕa there is no separate dependence on ϕa, i.e., all other density dependences of the correlation function C(r) appear only via the total area fraction ϕtot = ϕa + ϕp of the binary mixture. Our simulations, which involve different mixture compositions, confirm this prediction in Fig. 6a where we scale the correlation function by the area fraction of active particles ϕa for a fixed value of the total density ϕtot. Also note that upon increasing the total density the velocity correlation length increases, while the magnitude of the correlation decreases with ϕtot due to crowding (see Fig. S3). Figure 6b shows that the system has practically the same correlation length regardless of the fraction ϕa of active particles (or the fraction ϕp of passive particles) when the total area fraction ϕtot is sufficiently high and kept constant.

a The scaled velocity-velocity spatial autocorrelation function C(r) as a function of spatial distance r for different combinations of densities ϕa and ϕp of active and passive particles for a fixed value of ϕtot = 0.95 overall density. b Data for the correlation length are consistent with ξL being constant across the same combinations of ϕa and ϕp; the color scheme is the same as in a. The simulations for this figure were conducted at persistence time τp = 10 and active force f = 0.5. To accurately estimate the correlation length, we conducted 50 simulations with random initial configurations, collected 2500 snapshots in a stationary state from these simulations, and averaged the results to ensure precision. The error bars show the standard error of the mean.

We finally conducted a systematic investigation of finite-size effects for a system with a fixed total density of ϕtot = 0.95 (ϕa = 0.01, ϕp = 0.94), while using the same values for persistence time and self-propulsion force as in the previous plots. Specifically, we explored three different system sizes (L = 53σ, 106σ, 177σ) and found that the results exhibit a considerable degree of overlap across these system sizes (Fig. 7).

a Correlation length ξL as a function of the magnitude of the active force f for two different persistence times (τp = 10 and 100) and three different system sizes L. The results indicate that the correlation length ξL is unaffected by changes in the active force f, for fixed values of persistence time τp and system size L. The color scheme is the same as in b. b Correlation length ξL as a function of persistence time τp for different values of the active force magnitude (f = 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1) and three different system sizes L (indicated by different colors and markers). The results demonstrate that the correlation length ξL exhibits a power-law growth (with exponent \(\frac{1}{2}\), black dashed line) with increasing persistence time τp and that this behavior is independent of the magnitude of the active force f and system size L. To accurately estimate the correlation length, we conducted 50 simulations with random initial configurations, collected 2500 snapshots in a stationary state from these simulations, and averaged the results to ensure precision. The error bars show the standard error of the mean.

Conclusion

In this article we have demonstrated that long-range velocity correlations (which have only been observed in dense active mater system until now11,12,13,14,15) can be generated in a dense athermal passive system by including a very small fraction of persistent active Brownian particles. This observation conceptually decouples the roles played by density and activity parameters in generating such non-equilibrium ordering effects. Also, our results extend the discussion on whether the inclusion of disorder can increase order in a system or whether conversely, it tends to destroy order16,17,18,19.

We started by providing evidence that with a very small amount of active inclusions or dopants, an otherwise passive, dense athermal system can exhibit long-range velocity correlations similar to a pure dense assembly of active particles. We explored the degree of velocity correlation for different numbers of active and passive particles in such a mixture. We then derived the continuum theory to calculate the equal time velocity auto-correlation function in terms of the microscopic system parameters such as f, τp, etc. This theory made testable predictions that we confirmed via further molecular dynamics simulations. We examined the impact of different parameters on the velocity correlations and found good agreement between the simulation results and the continuum theory. Specifically, we found that the correlation length depends only on the overall area fraction of active and passive particles and grows as \(\sqrt{{\tau }_{p}}\) with the persistence time of self-propulsion. The latter result is in agreement with previous findings on purely active systems11,12,13,14,15.

Our predictions and results can be further tested both in simulations20,22,23 and in experiments, e.g., on mixtures of microbes and passive colloidal particles24, assemblies of active and passive colloids25,26, mixture of motile and non-motile bacteria27, or active granular mixtures28,29. In fact, real-world systems will typically be active-passive mixtures rather than purely active, so the result that velocity correlations are also seen in mixtures is crucial for their experimental observation in any system. Understanding the decoupling of density and activity makes it possible not only to reproduce a long-range velocity correlation in different active-passive mixtures or assemblies but also paves the way for designing and controlling active matter for practical purposes, e.g., in the context of transport and mixing.

Data availability

Data from this study are available via GRO.data at https://doi.org/10.25625/TURZGG.

Code availability

The code used in this study is available via GRO.data at https://doi.org/10.25625/TURZGG.

References

Marchetti, M. C. et al. Hydrodynamics of soft active matter. Rev. Mod. Phys. 85, 1143–1189 (2013).

Bechinger, C. et al. Active particles in complex and crowded environments. Rev. Mod. Phys. 88, 045006 (2016).

Fily, Y. & Marchetti, M. C. Athermal phase separation of self-propelled particles with no alignment. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 235702 (2012).

Takatori, S. C. & Brady, J. F. Towards a thermodynamics of active matter. Phys. Rev. E 91, 032117 (2015).

Cates, M. E. & Tailleur, J. Motility-induced phase separation. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 6, 219–244 (2015).

Levis, D., Codina, J. & Pagonabarraga, I. Active brownian equation of state: metastability and phase coexistence. Soft Matter 13, 8113–8119 (2017).

Solon, A. P., Stenhammar, J., Cates, M. E., Kafri, Y. & Tailleur, J. Generalized thermodynamics of motility-induced phase separation: phase equilibria, laplace pressure, and change of ensembles. New J. Phys. 20, 075001 (2018).

Mora, T. et al. Local equilibrium in bird flocks. Nat. Phys. 12, 1153–1157 (2016).

Ballerini, M. et al. Interaction ruling animal collective behavior depends on topological rather than metric distance: Evidence from a field study. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 1232–1237 (2008).

Mandal, R. & Sollich, P. Shear-induced orientational ordering in an active glass former. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2101964118 (2021).

Caprini, L., Marini Bettolo Marconi, U. & Puglisi, A. Spontaneous velocity alignment in motility-induced phase separation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 078001 (2020).

Caprini, L. & Marini Bettolo Marconi, U. Spatial velocity correlations in inertial systems of active brownian particles. Soft Matter 17, 4109–4121 (2021).

Caprini, L., Marconi, U. M. B., Maggi, C., Paoluzzi, M. & Puglisi, A. Hidden velocity ordering in dense suspensions of self-propelled disks. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 023321 (2020).

Henkes, S., Kostanjevec, K., Collinson, J. M., Sknepnek, R. & Bertin, E. Dense active matter model of motion patterns in confluent cell monolayers. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–9 (2020).

Szamel, G. & Flenner, E. Long-ranged velocity correlations in dense systems of self-propelled particles. Europhys. Lett. 133, 60002 (2021).

Yllanes, D., Leoni, M. & Marchetti, M. C. How many dissenters does it take to disorder a flock? N. J. Phys. 19, 103026 (2017).

Das, R., Kumar, M. & Mishra, S. Polar flock in the presence of random quenched rotators. Phys. Rev. E 98, 060602 (2018).

Martinez, R., Alarcon, F., Rodriguez, D. R., Aragones, J. L. & Valeriani, C. Collective behavior of vicsek particles without and with obstacles. Eur. Phys. J. E 41, 1–11 (2018).

Bera, P. K. & Sood, A. K. Motile dissenters disrupt the flocking of active granular matter. Phys. Rev. E 101, 052615 (2020).

Abbaspour, L. & Klumpp, S. Enhanced diffusion of a tracer particle in a lattice model of a crowded active system. Phys. Rev. E 103, 052601 (2021).

Weeks, J. D., Chandler, D. & Andersen, H. C. Role of repulsive forces in determining the equilibrium structure of simple liquids. J. Chem. Phys. 54, 5237–5247 (1971).

Stürmer, J., Seyrich, M. & Stark, H. Chemotaxis in a binary mixture of active and passive particles. J. Chem. Phys. 150, 214901 (2019).

Banerjee, J. P., Mandal, R., Banerjee, D. S., Thutupalli, S. & Rao, M. Unjamming and emergent nonreciprocity in active ploughing through a compressible viscoelastic fluid. Nat. Commun. 13, 4533 (2022).

Williams, S., Jeanneret, R., Tuval, I. & Polin, M. Confinement-induced accumulation and de-mixing of microscopic active-passive mixtures. Nat. Commun. 13, 4776 (2022).

Singh, D. P., Choudhury, U., Fischer, P. & Mark, A. G. Non-equilibrium assembly of light-activated colloidal mixtures. Adv. Mater. 29, 1701328 (2017).

Mu, Y. et al. Binary phases and crystals assembled from active and passive colloids. ACS Nano 16, 6801–6812 (2022).

Patteson, A. E., Gopinath, A. & Arratia, P. E. The propagation of active-passive interfaces in bacterial swarms. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–10 (2018).

Kumar, N., Soni, H., Ramaswamy, S. & Sood, A. Flocking at a distance in active granular matter. Nat. Commun. 5, 1–9 (2014).

Gupta, R. K., Kant, R., Soni, H., Sood, A. K. & Ramaswamy, S. Active nonreciprocal attraction between motile particles in an elastic medium. Phys. Rev. E 105, 064602 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted within the Max Planck School Matter to Life, supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) in collaboration with the Max Planck Society. The simulations were run on the GoeGrid cluster at the University of Göttingen, which is supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Project IDs 436382789; 493420525) and MWK Niedersachsen (Grant no. 45-10-19-F-02). This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant agreement no. 893128. We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Funds/transformative agreements of the University of Göttingen.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.A. and R.M. designed the simulations. L.A. wrote the simulation code, ran the model, and analysed output data. R.M. and P.S. designed the theory. S.K. and P.S. supervised the study. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data, discussions of the results, and writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abbaspour, L., Mandal, R., Sollich, P. et al. Long-range velocity correlations from active dopants. Commun Phys 7, 289 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-024-01780-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-024-01780-w