Abstract

The Hall response can be dramatically different from its quantized value in materials with broken inversion symmetry. This stems from the leading Hall contribution beyond the linear order, known as the Berry curvature dipole (BCD). While the BCD is in principle always present, it is typically very small outside of a narrow window close to a topological transition and is thus experimentally elusive without careful tuning of external fields, temperature, or impurities. We transcend this challenge by devising optical driving and quench protocols that enable practical and direct access to large BCD. Varying the amplitude of an incident circularly polarized laser drives a topological transition between normal and Chern insulator phases, and importantly allows the precise unlocking of nonlinear Hall currents comparable to or larger than the linear Hall contributions. This strong BCD engineering is even more versatile with our two-parameter quench protocol, as demonstrated in our experimental proposal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The nonlinear Hall effect is an exciting response contribution beyond the much-studied quantum anomalous Hall effect1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8, in which an applied electric field results in a quantized transverse current response in an insulator. It stems from a higher-order correction in the quantum response known as the Berry curvature dipole (BCD)2, which generically exists whenever inversion symmetry is broken2,3,4,5. Venturing beyond the topological paradigm, the BCD leads to an interesting nonlinear anisotropic current response accompanied by higher harmonic generation9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16 and has motivated a large number of experimental investigations. Indeed, the BCD has been observed in a variety of materials, such as two-dimensional bilayer or few-layer WTe28,17,18,19,20,21, BiTeI22, bilayer graphene23, twisted bilayer graphene24,25, twisted double bilayer graphene26, strained twisted bilayer graphene27,28, two-dimensional monolayer WSe229, strained twisted bilayer WSe230, two-dimensional monolayer MoS231,32, Weyl semimetal TaIrTe433, three-dimensional Dirac semimetal Cd3As234,35, \({{\mathbb{Z}}}_{2}\) topological insulator Bi2Se336, the Weyl–Kondo semimetal Ce3Bi4Pd337, and Td-MoTe238. The dominance of the intrinsic nonlinear Hall effect in antiferromagnets with \({{{\mathcal{P}}}}{{{\mathcal{T}}}}\) symmetry has been studied39,40,41,42,43 and subsequently experimentally probed in thick Td-MoTe2 samples44. More recently, the quantum metric-induced nonlinear Hall effect in a topological antiferromagnet MnBi2Te4 has also been reported45,46,47.

Yet, despite its supposed ubiquity, observing the BCD (or its associated nonlinear Hall response) is fraught with practical challenges. Besides generic experimental demands such as maintaining low temperatures (10 ~ 100 K5,8), a key challenge is that the BCD is only significant in a narrow window very close to a topological phase transition3. Accessing it hence requires precise control of external parameters such as magnetic field45,47, electric field5,8,17,19,44, temperature8,44,45,47, charge/carrier density8,45,47, strain26,27,28,29,30, or impurities4,24,25,48,49, which are not easily tuned. As such, only a few notable experimental observations of the nonlinear Hall effect exist till date, through measuring the BCD8,17,18,19,20,21,23,26, intrinsic nonlinear Hall conductivity25,44,45,47, or both24.

To circumvent these challenges, we devise optical driving and quench protocols that can precisely tune a system such that the nonlinear Hall response is dramatically enhanced. Through the periodic driving of polarized light, we not only obtain an approach for driving topological phase transitions that may be inaccessible in static systems, but more importantly unlock new routes towards the versatile engineering of the BCD. Obtaining the effective Hamiltonian through the high-frequency Floquet-Magnus expansion50,51,52, we identify a light-enhanced peak in the BCD that can be tuned via the intensity of an applied circularly polarized laser in a very versatile manner. This is accompanied by a critical light-induced band inversion, which demarcates a topological phase boundary between Chern and normal insulator phases, notably without involving the tuning of any other physical parameter. Crucially, the precise tunability of our approach allows for further band engineering via temporal modulation of the laser strength, resulting in controlled modulation of the BCD strength over a wide range.

Results

General formalism

We first provide the foundational framework for the nonlinear Hall effect, such as to contrast it with the more commonly known linear Hall effect. When subjected to external driving forces, the typical dominant response observed is the linear response, which, for instance, accounts for the well-known quantum Hall effect with broken time-reversal symmetry. In general, a linear response encompasses longitudinal and transverse currents. However, nonlinear response can also manifest strongly in transverse currents2,3,4,5,8,18,25,42,43,44,45,47,48,49 due to higher-order Berry curvature effects, with a doubled frequency component in the current signal in the transverse direction. Consequently, the transverse current is proportional to the second power in the longitudinal fields.

The response from a driven electric field E is measurable through the electric current density J. We expand the electric current density Ji in increasing orders of the electric field as

where {i, j, k, l} ∈ {x, y, z}, and E = (Ex, Ey, Ez) is the external electric field. Here, the first term denotes the linear response, and its frequency follows the external electric field. The second term is the leading nonlinear contribution with a doubled frequency.

Below, we shall derive the linear and nonlinear responses through a semi-classical approach, where the perturbative effects of an external electric field are treated via the electronic occupation functions. Subsuming the effects of electron scattering under a phenomenological relaxation time τ, the relaxation time approximation yields the following Boltzmann equation2,53,54,55

where − e is the electron charge, ℏ is the reduced Planck’s constant, ka is the wave vector of electronic wavepackets along the a ∈ {x, y, z} directions, f0 is the equilibrium occupancy given by the Fermi-Dirac distribution function, and f is the non-equilibrium distribution function. Here, τ sets the timescale for f to relax to its equilibrium distribution f0. By inverting the derivative operators, we can directly solve for the non-equilibrium distribution function f as follows:

To understand how the response originates from this mathematical framework, we expand f into \(f={{{\rm{Re}}}}({f}_{0}+{f}_{1}+{f}_{2}+\cdots )\), where fj contains terms with the j-th power of the electric fields. Below, we shall only retain up to the quadratic order, such that

with band dispersion ϵk and the Berry curvature Ωk56,57. To proceed, we consider a single-frequency driven electric field \({{{\bf{E}}}}(t)={E}_{a}(t){{{{\bf{e}}}}}_{a}={{{\rm{Re}}}}({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{a}{e}^{i\omega t}){{{{\bf{e}}}}}_{a}\) along the a direction and write down the coefficients of non-equilibrium distribution to the first and second orders:

Since the second-order coefficient f2 comprises both \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{a}^{2}\) and \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{a}^{2}{e}^{i2\omega t}\) terms, it contains both a constant and a frequency-doubled term. Specifically, by substituting Eq. (5) into Eq. (4), one can have

where \({J}_{b}^{0}={\chi }_{baa}^{(0)}{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{a}^{2},\,{J}_{b}^{\omega }={\chi }_{ba}^{(1)}{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{a},\,{J}_{b}^{2\omega }={\chi }_{baa}^{(2)}{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{a}^{2}\), with coefficients given at the leading order by

In the above, we have only kept terms to leading order in \(\frac{e\tau }{\hslash }{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{a}a\) (with the lattice constant a), which is very small in relevant experiments8. For the subleading contributions, see equations (50) to (52) in the Methods Section VIA. In the above, εbac is the Levi-Civita anti-symmetric tensor; a, b, and c index the spatial coordinates x, y, and z. The two relevant physical quantities are the linear Hall conductance σc and the nonlinear Hall response BCD (Dac). Specializing to the 2D x − y plane such that the index c = z, we write the Hall conductance as57,58,59

where \({\Omega }_{{{{\bf{k}}}},z}^{(n)}\) is the Berry curvature corresponding to the n-th eigenstate. However, the main quantity of focus in this work is the BCD:

Its detailed derivation can be found in Methods Section VIA. Here, the derivative of the equilibrium distribution function is given by \(\partial {f}_{0}/\partial {\epsilon }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{(n)}=\frac{-{e}^{\left({\epsilon }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{(n)}-{E}_{F}\right)/({k}_{B}T)}}{{\left[1+{e}^{\left({\epsilon }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{(n)}-{E}_{F}\right)/({k}_{B}T)}\right]}^{2}{k}_{B}T}\), where T is the temperature and kB is the Boltzmann constant. The above integral for the BCD indicates that the nonlinear Hall response is predominantly governed by the states near the Fermi energy EF3,4,5,48. We can interpret Dac as the momentum-space integral over the Berry curvature \({\Omega }_{{{{\bf{k}}}},c}^{(n)}\) weighted by the dispersion \({\partial }_{{k}_{a}}{\epsilon }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{(n)}\) and occupation gradient \(\partial {f}_{0}/\partial {\epsilon }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{(n)}\), summed over all eigenstates n. Since inversion symmetry breaking is essential for the non-vanishing Berry curvature, only systems with broken inversion symmetry can exhibit non-zero BCD and thus nonlinear (transverse) response3,4,5,48.

Two-component models

The simplest models with nontrivial linear Hall and nonlinear BCD responses require at least two bands for nontrivial Berry curvature. A generic 2-component model is expressed as the ansatz

where σx,y,z are the Pauli matrices, and σ0 is the 2 × 2 identity matrix. The eigenenergies for its upper (+) and lower (−) bands are

with corresponding eigenvectors \(\left\vert {\psi }^{(\!\pm\! )}\right\rangle\) (k subscript index omitted for brevity). The z component of Berry curvature, which contributes to the Hall response in two-dimensional systems, is given by57,58,59,60,61,62

Notice that, compared to more realistic lattice models under circularly polarized light, a simple linearized model (for example, the type-I Weyl semimetal) with additional quadratic k2 terms can lead to different physics11. For a type-I Weyl semimetal, the population at one Weyl node induced by the left circularly polarized light is the same as that induced at the other Weyl node by the right circularly polarized light11. However, once the non-linearity (near the Weyl nodes) of the band structure is taken into account, the excitations induced near one Weyl node by the left circularly polarized light will no longer overlap perfectly with that induced near the other Weyl node by right circularly polarized light, even though the key Hall contributions remain similar.

Effective Floquet Hamiltonian from optical driving

The paradigmatic model for describing nonlinear Hall materials, for instance, monolayer WTe28,18,19,20, is the two-dimensional tilted massive Dirac model2,3,48,63, which form the theoretical basis in nonlinear Hall effect experiments3,8:

where η is allowed to take values of ± 1 in principle (in our numerics, we set η = − 1), and t0, v, m, and α are parameters that can be empirically fitted. The tilted term t0kxσ0 breaks the inversion symmetry and is key to triggering the nonlinear Hall effect.

We next discuss how optical driving can modify the effective Hamiltonian and consequently significantly and precisely enhance the BCD. In a generic setting, the optical electric field propagating along the z direction can be expressed as \({{{\bf{E}}}}(t)=\partial {{{\bf{A}}}}(t)/\partial t={E}_{0}(\cos (\tilde{\omega }t),\cos (\tilde{\omega }t+\varphi ))\), where E0 is the amplitude of the electric field and \(\tilde{\omega }\) is the angular frequency of the light. The phase φ controls the polarization: φ = 0 introduces linear polarization, while φ = ∓ π/2 introduces left- or right-handed circular polarization. Integrating, we can have \({{{\bf{A}}}}(t)={{{\bf{A}}}}(t+T)={\tilde{\omega }}^{-1}{E}_{0}(\sin (\tilde{\omega }t),\sin (\tilde{\omega }t+\varphi ))\) that is of period \(T=2\pi /\tilde{\omega }\). Notice that the light frequency \(\tilde{\omega }\) is much higher than the ultralow frequency ω (17.77 Hz8) of an longitudinal alternating current (a.c.) \({I}_{x}^{\omega }\), which is used to induce the transverse nonlinear Hall effect in experiments5,8.

Under optical driving, the motion of electrons is governed by minimal substitution of the lattice momentum with the electromagnetic gauge field A(t). Hence, the photon-dressed effective Hamiltonian is given by

In our Floquet band engineering proposal, we are interested in the off-resonant regime where the central Floquet band is far away from other replicas, such that the high-frequency expansion is applicable50,51,52. As such, we set the driving optical frequency to the representative value \(\hslash \tilde{\omega }=1\) eV64 (\(\tilde{\omega } \sim 1.519\times 1{0}^{15}\) Hz), which is much larger than the bandwidth61,65,66. Under periodic driving through A(t), the effective Floquet Hamiltonian52,61,65,66,67\({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}^{(F)}({{{\bf{k}}}})=\frac{i}{T}\ln \left[{{{\mathcal{T}}}}{e}^{-i\int_{0}^{T}{{{\mathcal{H}}}}({{{\bf{k}}}},t)dt}\right]\) is the effective static Hamiltonian with the effects of the periodic driving “averaged” over one period. In the high-frequency regime, a closed-form solution exists via the Magnus expansion50,51,52

where \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{n}=\frac{1}{T}\int_{0}^{T}{{{\mathcal{H}}}}({{{\bf{k}}}},t){e}^{in\tilde{\omega }t}dt\) is the n-th time Fourier component of \({{{\mathcal{H}}}}({{{\bf{k}}}},t)\). For our tilted Dirac model (Eq. (14)), all but the n = 1 commutators vanish, as shown in Methods Section VIB, and the Floquet Hamiltonian takes the form

where h0 = t0kx as before,

and \({A}_{0}=e{E}_{0}/(\hslash \tilde{\omega })\). Specifically, the intensity of the employed light is below the damage threshold. The maximum value of light amplitude used in our work is A0 ~ 1.49 nm−1, which corresponds to the amplitude of the electric field \({E}_{0}=\hslash \tilde{\omega }{A}_{0}/e \sim 1.49\times 1{0}^{9}\) V/m. This maximum value of E0 is smaller than 3.0 × 109 V/m in refs. 68,69, and it is also smaller than the maximum value 1.06 × 1010 V/m in ref. 70. The detailed derivations for Eqs. (17) to (20) can be found in Methods Section VIB. Explicitly, we see that the optical driving has introduced new contributions proportional to \({A}_{0}^{2}\), which acts as a rescaling of the effective mass m (up to an overall rescaling of the Hamiltonian) and hence ultimately its nonlinear response properties. To have non-vanishing BCD, note that t0 ≠ 0 is still required for inversion symmetry breaking (Methods Section VIC), even though time-reversal symmetry is already broken for any values of t0 and A0 (Methods Section VID). Note that in the later numerical calculations, the Hamiltonian (17) would be regularized into its corresponding tight-binding lattice Hamiltonian. The tight-binding lattice model for the Floquet Hamiltonian is shown in Supplementary Note 1.

To estimate the validity of the high-frequency expansion quantitatively, we evaluate the maximum instantaneous energy of the time-dependent Hamiltonian \({{{\mathcal{H}}}}\left({{{\bf{k}}}}-\frac{e}{\hslash }{{{\bf{A}}}}(t)\right)\) averaged over a Floquet period \(\frac{1}{T}\int_{0}^{T}dt\,\max \left\{\left\vert \right.\left\vert \right.{{{\mathcal{H}}}}({{{\bf{k}}}},t)\left\vert \right.\left\vert \right.\right\} < \hslash \tilde{\omega }\) at the Γ point (kx = ky = 0), which gives the following constraint on the optical field parameters: \({{{\rm{Max}}}}\left(v{A}_{0},2\alpha {A}_{0}^{2}\right) < \hslash \tilde{\omega }\) i.e. \({A}_{0} < {{{\rm{Min}}}}\left(\frac{\hslash \tilde{\omega }}{v},\sqrt{\frac{\hslash \tilde{\omega }}{2\alpha }}\right)\). In the high-frequency regime \(\tilde{\omega } \sim 1.519\times 1{0}^{15}\) Hz (\(\hslash \tilde{\omega }=1\) eV) with parameters set to v = 0.1 eV ⋅ nm and α = 0.1 eV ⋅ nm2, the same order as those in representative 2D Dirac materials such as WTe28,17,18,19,20, MoTe263, and other WTe2-type materials71, one can obtain \({A}_{0}=e{E}_{0}/(\hslash \tilde{\omega }) \, < \, 2.236\) nm−1 (\({E}_{0}={A}_{0}\hslash \tilde{\omega }/e \, < \, 2.236\times 1{0}^{9}\) V/m), which corresponds to an incident light intensity72 of \(I=\frac{1}{2}nc{\varepsilon }_{0}| {E}_{0}{| }^{2} < 9.954\times 1{0}^{15}\) W/m2, where n is the refractive index, c is the speed of light in vacuum, and ε0 is the vacuum permittivity. The refractive index \(n \sim {{{\mathcal{O}}}}(1)\), with n ≈ 1.573 observed in monolayer WTe2 in the deep-ultraviolet region.

Divergent nonlinear Hall response near a topological transition

Light-induced topological transition

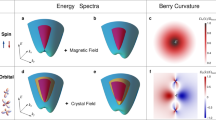

Before showing how a large nonlinear Hall response can be achieved, we first elaborate on the topological phase transition induced by optical driving. Shown in Fig. 1 are the energy band structure, Berry curvature, Hall conductance, and BCD under right-handed circularly polarized light (i.e., φ = π/2) at different intensities A0.

Top row a1–e1: The ky = 0 slice of the Floquet band structure (Eq. (12)) for our nonlinear Hall medium (Eq. (17)), which exhibits a band inversion at laser amplitude A0 → A0c ≈ 1.0541nm−1. Second row a2–e2: Berry curvature \({\Omega }_{{{{\bf{k}}}},z}^{(-)}\) (Eq. (13)) of the lower band, which integrates to + 1 for A0 < A0c and 0 for A0 > A0c. Third row a3–e3: The resultant linear Hall conductance (Eq. (9)) as a function of the Fermi energy EF, which is quantized at + e2/h in the gap (pale yellow) for A0 < A0c and 0 for A0 > A0c, corresponding to the Chern insulator (CI) and normal insulator (NI) phases, respectively. Fourth row a4–e4: The nonlinear BCD Dxz (Eq. (10)), which vanishes when EF is in the gap, but which peaks when EF is near the band edge. Near the transition at A0 ≈ A0c, the peak becomes drastically higher and narrower. The other parameters are φ = π/2 (right-handed circularly polarized light), \(\hslash \tilde{\omega }=1\) eV, t0 = 0.05 eV ⋅ nm, v = 0.1 eV ⋅ nm, α = 0.1 eV ⋅ nm2, m = 0.1 eV, η = − 1, and kBT = 0.003 eV, i.e., T ≈ 34.8136 K, which are of the same order as those in refs. 8,63,71.

As can be theoretically predicted from Eqs. (18) to (20), the energy gap (pale yellow in Fig. 1a1–e1 closes at the critical intensity \({A}_{0c}=\sqrt{m/\left(\alpha +\eta \frac{{v}^{2}\sin \varphi }{\hslash \tilde{\omega }}\right)}\approx 1.0541\) nm−1 Fig. 1c1. Tuning the intensity across A0c not only closes and then opens the energy gap, but also gives rise to band inversion (Fig. 1a1–e1, as evident from the change in sign of the Berry curvature of the lower band as shown in Fig. 1a2–e2, as analytically derived in Supplementary Note 2.

The fact that this band inversion corresponds to a topological transition can be seen in the change of the quantized value of the Hall conductance σH for EF in the gapped region (yellow) (Fig. 1a3–e3). When the light intensity A0 is below the critical value A0c, the energy spectrum is gapped (Fig. 1a1 and b1) and the corresponding Hall conductance is quantized at e2/h within the gap as shown in Fig. 1a3 and b3. This corresponds to the Chern insulator (CI) phase. When the light intensity A0 > A0c, the spectrum is also gapped, as shown in Fig. 1d1 and e1, but the corresponding Hall conductance equals zero as shown in Fig. 1d3 and e3. This is the normal insulator (NI) phase.

Most saliently, at the topological phase transition A0c, the BCD (Dxz) diverges for EF near the band edge, just outside of the pale yellow gap region. Very close to the transition, as shown in Fig. 1c4, it is orders of magnitude larger than that away from the transition, i.e., Fig. 1a4, b4, d4, and e4. Since the BCD is proportional to the nonlinear Hall conductance, which can be directly measured, this divergence would have profound physical consequences, as explored in the following subsection. Analogous results under left-handed circularly polarized light (φ = − π/2) are qualitatively similar and can be found in Supplementary Note 3.

Notice that the circularly polarized light (φ = ± π/2) can be used to break the time-reversal symmetry of the nonlinear Hall material (for example, WTe23,8) and realize a topological transition between normal and Chern insulator phases, but the linearly polarized light cannot break the time-reversal symmetry. Therefore, varying the amplitude of an incident circularly polarized laser drives a topological transition between normal and Chern insulator phases, and importantly allows the precise unlocking of nonlinear Hall currents comparable to or larger than the linear Hall contributions, notably without involving the tuning of any other physical parameter. Moreover, the high-harmonic generation is also a nonlinear process10. As pointed out by ref. 10, time-reversal symmetry-broken systems can lead to anomalous odd harmonics even based on a linearly polarized driving pulse. This is an alternate way to see the nonlinear Hall effect using a polarized driving light.

Non-quantized current from nonlinear light-enhanced BCD

While it is commonly expected for the Hall current to be quantized according to the Chern number, in the presence of a large BCD, the Hall current should actually deviate considerably from its quantized value. In principle, this should be observable since a large BCD generally exists near a topological Chern transition with inversion symmetry breaking. However, in most realistic experimental settings, it is usually extremely difficult to tune the system to the BCD peak, which is extremely narrow, as plotted in black in Fig. 2a for our system with φ = π/2 (right-handed circularly polarized light). A key advantage of our Floquet-induced BCD approach is that, by adjusting the laser intensity A0, one is able to very precisely tune the system across the topological transition value A0c, where the BCD (black) peaks and its corresponding bandgap Δ (blue) vanishes.

(a) BCD (Eq. (10)) peak max(∣Dxz∣) (black) and band gap \(\Delta =\min [{\epsilon }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{(+)}]-max[{\epsilon }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{(-)}]\) (blue) as a function of light amplitude A0. While the gap Δ vanishes as A0 → A0c ≈ 1.0541 nm−1, leading to a transition between the Chern insulator (CI) and normal insulator (NI) phases, the BCD is dramatically enhanced. The BCD peak values correspond to the maximum of Dxz over the broad window EF ∈ ( − 0.2, 0.2) eV. (b) The root-mean-square Hall current density \(\sqrt{\langle {J}_{y}^{2}\rangle }\) (Eq. (21)) as a function of A0, from metallic (EF = 0.1 eV) to purely insulating (EF → 0) cases. While \(\sqrt{\langle {J}_{y}^{2}\rangle }\) is understandably not quantized along the dashed line when the system is not insulating (purple, yellow), it is still not completely quantized even when EF is well within the gap (red). Instead, it exhibits a pronounced spike when A0 is very close to A0c due to the large BCD contribution. Despite its narrowness, this spike is experimentally accessible due to the experimental ease of tuning A0. Other than the electric field amplitude \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{x}\) = 0.1 V/m, τ ≈ 4.12434 × 10−14 s8, a.c. frequency ω = 17.777 Hz8, and the other parameters used are identical to those in Fig. 1.

The tuning of the light amplitude to a precision of A0 ~ 0.1 nm−1 at least or better has been shown to be experimentally feasible. With fixed \(\hslash \tilde{\omega }=1\) eV and the relation \({A}_{0}=e{E}_{0}/(\hslash \tilde{\omega })\), we can get the precision of light amplitude A0 ~ 0.025 nm−1 with E0 = 2.5 × 107 V/m74, A0 ~ 0.116 nm−1 with E0 = 11.6 × 107 V/m75, and A0 ~ 0.04 nm−1 with E0 = 4.0 × 107 V/m76. Here E0 is the amplitude of the electric field for the light. This precision in tuning A0 allows one to observe the Hall current deviating greatly from its quantized value. Plotted in Fig. 2b is the root-mean-square of the Hall current density Jy (Eq. (6)) averaged over a period \(\tilde{T}=2\pi /\omega\) as the driving light intensity A0 is varied for an applied field \({E}_{x}^{\omega }={{{\rm{Re}}}}({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{x}{e}^{i\omega t})\). Explicitly, from Eq. (6) to (8),

where σH gives the linear Hall conductance contribution and the BCD (Dxz) provides the nonlinear contribution. When EF is outside of the bandgap (see Fig. 1), \(\sqrt{\langle {J}_{y}^{2}({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{x})\rangle }\) is not quantized as expected. However, for smaller Fermi energy, i.e., EF = 0.001 eV (red) where the system is clearly insulating, \(\sqrt{\langle {J}_{y}^{2}({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{x})\rangle }\) does not remain quantized all the time; when A0 is tuned very close to A0c where a Chern transition occurs, \(\sqrt{\langle {J}_{y}^{2}({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{x})\rangle }\) exhibits a sharp spike due to the BCD (Dxz) peak. For a very narrow window of light intensity A0, this nonlinear contribution can in fact be much larger than the usual linear contribution. Importantly, this window, albeit narrow, is readily experimentally accessible due to the ease of accurately tuning A077,78. Further discussion on the competition between the linear and nonlinear current contributions can be found in Methods Section VIE.

Enhanced BCD through Floquet quench

An interesting extension of our above-mentioned approach involves performing a Floquet quench on the normal and Chern insulator phases. Since from Fig. 1, the Chern insulator phase exists without optical driving and the normal insulator phase is generated by a strong polarized light, we shall periodically quench the polarized light to alternate rapidly between light-off and light-on (shown in Fig. 3), as can be achieved in experiments on attosecond pulses of light9,13,14,79,80,81,82. Without loss of generality, we employ right-handed circularly polarized light with φ = π/2 in the following discussions.

In our nonlinear Hall material (taking the left figure for example), a lock-in amplifier is used to measure the nonlinear Hall voltage \({V}_{y}^{2\omega }\) resulting from a longitudinal electrical field \({E}_{x}^{\omega }={{{\rm{Re}}}}({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{x}{e}^{i\omega t})\) induced by an a.c. \({I}_{x}^{\omega }\) with ultralow frequency ω, which is much lower than the optical driving frequency \(\tilde{\omega }\). Left figure: In the duration time T1, there is no illumination on the nonlinear Hall material. Right figure: In the duration time T2, there is a high-frequency irradiated light (purple) with amplitude \({A}_{0}=\sqrt{2}{A}_{0c}\) and high frequency \(\tilde{\omega }\) illuminating the nonlinear Hall material. The total periodic time is T = T1 + T2.

As shown in Fig. 3, we consider a periodic two-step quench with a total period of T1 + T2, such that each period consists of an odd (even) step governed by the Hamiltonian under light-off (light-on) polarized light described by \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{1}({{{\bf{k}}}})\) [\({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{2}({{{\bf{k}}}})\)], for a duration of T1 [T2]. \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{1}({{{\bf{k}}}})\) denotes the Hamiltonian without light, i.e., A0 = 0, and \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{2}({{{\bf{k}}}})\) denotes the Hamiltonian under right-handed circularly polarized light with φ = π/2 and \({A}_{0}=\sqrt{2}{A}_{0c}=\sqrt{2m/\left(\alpha +\eta \frac{{v}^{2}\sin \varphi }{\hslash \tilde{\omega }}\right)}\approx 1.49071\) nm−1, which from Fig. 1 is well within the normal insulating phase. The effective Floquet Hamiltonian is given by61

whose gap (pale yellow in Fig. 4) depends intimately on the values of both T1 and T2. For our choice of light amplitudes A0 = 0 for \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{1}({{{\bf{k}}}})\) and \({A}_{0}=\sqrt{2}{A}_{0c}\) for \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{2}({{{\bf{k}}}})\), the gap closes at T1 = T2 (Fig. 4b1), which also induces a band inversion that separates the CI phase (with T1 > T2) from the NI phase (with T1 < T2). This is shown through the Berry curvature of the lower band \({\Omega }_{{{{\bf{k}}}},z}^{(-)}\) in Fig. 4a2–c2 and its corresponding linear Hall conductance in Fig. 4a3–c3. Similar to that in Fig. 1, the BCD (Dxz) also exhibits a sharp peak near the band edge when the band gap vanishes, although this behavior is now precisely tunable through the ratio T1/T2 (with T2 fixed at 0.1ℏ/eV ≈ 6.58212 × 10−17s), rather than the laser amplitude A0. Analogous results for left-handed circularly polarized optical driving (φ = − π/2) can be found in the Supplementary Note 3.

a1–c1 Floquet energy bands (Eq. (22)) for the ky = 0 slice. In (a1) where T1 = 0.1T2 and (c1) where T2 = 0.1T1, the \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{2}({{{\bf{k}}}})\) with light amplitude \({A}_{0}=\sqrt{2}{A}_{0c}\) and \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{1}({{{\bf{k}}}})\) with A0 = 0 are respectively dominant. They respectively correspond to the normal insulator (NI) and Chern insulator (CI) phases and are both gapped (pale yellow). But in (b1) where T1 = T2, nontrivial contributions from \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{1}({{{\bf{k}}}})\) and \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{2}({{{\bf{k}}}})\) cancel each other out, leaving a gapless band structure. a2–c2 Berry curvature (Eq. (13)) of the lower band, whose integral over the kx-ky plane interpolates between the quantized values of 0 and + 1 as T1/T2 increases. a3-c3 The corresponding Hall conductance (Eq. (9)), which exhibits these quantized values when EF is within the band gap (pale yellow). a4–c4 The BCD (Dxz) (Eq. (10)), which vanishes for EF within the band gap but which peaks at the band edges, particularly when T1 = T2. The other parameters are identical to those in Fig. 1. Here, T2 is fixed at 0.1ℏ/eV ≈ 6.58212 × 10−17 s.

With independent control over both T1 and T2 step durations, this Floquet quench approach offers even greater versatility in tuning the topological phase transition and approaching the BCD peak. Shown in Fig. 5 are the band gap Δ and BCD peak \(\max | {D}_{xz}|\) in the parameter spaces of T1 and T2. Evidently, the phase boundary occurs along the T1 = T2 line, which also corresponds to the peaks in the BCD. By simultaneously adjusting T1 and T2, maximal nonlinear Hall response from the BCD term can be obtained.

Our quenching protocol offers versatility in the tuning of the nonlinear Hall response through the two independent quench durations T1 and T2. a The band gap Δ (Eq. (22)) in the (T2, T1) parameter space. b The quench-enhanced BCD peak (Eq. (10)), which saliently peaks around the T1 = T2 line where the gap closes. Here NI denotes the normal insulator phase and CI denotes the Chern insulator phase. The other parameters are identical to those in Fig. 1.

Measurement of the nonlinear BCD response

The nonlinear response due to light-enhanced BCD can be experimentally measured in the schematic setup shown in Fig. 6a. Floquet driving is achieved through high-frequency laser pumping (purple), whose amplitude A0 can be tuned to sensitively adjust the BCD strength. The nonlinear response current density \({J}_{y}^{2\omega }\), which is perpendicular to the longitudinal electric field \({E}_{x}^{\omega }={{{\rm{Re}}}}({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{x}{e}^{i\omega t})\) induced by an alternating current (a.c.) \({I}_{x}^{\omega }\) at ultralow frequency ω, can be measured with a lock-in amplifier on its corresponding potential difference \({V}_{y}^{2\omega }\).

a In our nonlinear Hall insulator, a lock-in amplifier can be used to measure the nonlinear Hall voltage \({V}_{y}^{2\omega }\) resulting from a longitudinal electrical field \({E}_{x}^{\omega }={{{\rm{Re}}}}({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{x}{e}^{i\omega t})\) induced by an a.c. \({I}_{x}^{\omega }\) of ultralow frequency ω, which is much lower than the optical driving frequency \(\tilde{\omega }\). High-frequency (\(\tilde{\omega }\)) irradiated light (purple) of amplitude A0 ≈ A0c produces the requisite Floquet-enhanced Berry curvature dipole (BCD). b The BCD (Dxz) (Eq. (10)) as a function of the Fermi energy EF for various light amplitudes A0 close to the critical value A0c ≈ 1.0541 nm−1 where a topological transition occurs, as labeled in (c). The BCD is dramatically enhanced nearest to A0c, peaking at ~ 3 nm that is comparable to experimentally measured values in Ref. 8. c The peak of the second-harmonic Hall current density \({J}_{y}^{2\omega }={\chi }_{yxx}^{(2)}{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{x}^{2}\) (Eq. (6)), which varies nonlinearly with the amplitude of the applied perpendicular electric field \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{x}\), and is greatly enhanced for A0 nearest to A0c. The other parameters are φ = π/2 (right-handed circularly polarized light), \(\hslash \tilde{\omega }=1\) eV, t0 = 0.05 eV ⋅ nm, v = 0.1 eV ⋅ nm, α = 0.1 eV ⋅ nm2, m = 0.1 eV (Eq. (14)), kBT = 0.003 eV, i.e., T ≈ 34.8 K, τ ≈ 4.124 × 10−14 s8, and ω = 17.77 Hz8.

To obtain the BCD (Dxz) explicitly, we invoke the nonlinear Hall response relation \({J}_{y}^{2\omega }={\chi }_{yxx}^{(2)}{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{x}^{2}\) in Eq. (8):

in which \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{x}\) and \({J}_{y}^{2\omega }\) can be obtained from the excitation current \({I}_{x}^{\omega }\) and measured perpendicular \({V}_{y}^{2\omega }\) via Ohm’s law as \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{x}=\frac{{I}_{x}^{\omega }}{\sigma W}\) and \({J}_{y}^{2\omega }=\frac{\sigma {V}_{y}^{2\omega }}{W}\). As shown in Fig. 6a, W is the effective sample width, and the longitudinal conductance is of the order of σ ~ 10−5 S8. From the Drude formula \(\sigma =\frac{{n}_{0}{e}^{2}\tau }{\tilde{m}}\), one can also estimate the relaxation time τ to be ~ 10−14 s with the effective mass being \(\tilde{m}=0.3{m}_{e}\), me the electron mass8, and n0 the charge density. Tuning this charge density n0 also modifies the Fermi energy EF, as demonstrated by first-principle calculations in a related system8.

Experimentally, it suffices to use an ultralow a.c. frequency ω of the order of 10−102 Hz8, such that ωτ → 0 and we obtain

Based on these physical parameters, the BCD (Dxz) is plotted in Fig. 6b for various optical driving amplitudes A0 near the critical value A0c ≈ 1.0541 nm−1. It exhibits peaks of up to 3 nm for A0 = 1.0540 nm−1 (blue curve in Fig. 6b), the same order as in the experimentally measured BCD in bilayer WTe28, even though our system is monolayer. The peak width increases with temperature and is about EF ~ 10−2 eV when calculated with the temperature of T ≈ 34.8 K taken from the experiment in8.

As evident, Dxz exhibits high sensitivity to the value of A0 near the critical value A0c. This also translates to the high sensitivity of the peak of the nonlinear Hall current density \({J}_{y}^{2\omega }\), as plotted in Fig. 6c. The nonlinearity of the current response is evident from the curvature of max(\({J}_{y}^{2\omega }\)) plotted against the perpendicular electric field amplitude \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{x}\), particularly for values of A0 closest to A0c (blue, pink).

Notice that there are two frequency scales that differ by several orders of magnitude in this work: the very slow driving frequency of the longitudinal electrical field (ω = 17.77 Hz8), and the rapid driving from the irradiation (\(\hslash \tilde{\omega }=1\) eV). As shown in Fig. 6a, the driving frequency of the longitudinal electrical field (blue) E (i.e., \({E}_{x}^{\omega }\)) in Eq. (4) is ω = 17.77 Hz8, which is very low. Therefore, the semiclassical current (Eq. (4)), which involves the Berry curvature, is valid. On the other hand, the high frequency \(\hslash \tilde{\omega }=1\) eV is for our irradiated light (purple) as shown in Fig. 6a. Here, the rapid driving modifies the band structure and does not participate in the semiclassical theory, which is based on the effective Floquet model after “integrating out” the rapid driving. Furthermore, our irradiated light (purple) is along z direction as shown in Fig. 6a and Eq. (13) only provides the z component of the Berry curvature. Therefore, the irradiated light cannot contribute to the semiclassical current (Eq. (4)) with an additional term \(\frac{e}{\hslash }{{{{\bf{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{light}}}}}\times {{{{\mathbf{\Omega }}}}}_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}\), where Elight is the electrical field of our irradiated light and Elight × Ωk = ElightΩk,z(ez × ez) = 0. But the irradiated light can modify the Berry curvature through the electromagnetic gauge field (Eq. (15)) within the Floquet theory as shown in Eq. (13).

Conclusion

We find that nonlinear Hall materials can exhibit a strong light-enhanced Berry curvature dipole (BCD) and hence a nonlinear Hall response when excited by circularly polarized lasers. This was established using the two-dimensional tilted massive Dirac Hamiltonian that accurately models known nonlinear Hall materials such as WTe28,17,18,19,20, MoTe244,63, and other WTe2-type materials71. More generally, however, the dramatic light-induced BCD enhancement is expected to occur in all media with simultaneously broken time-reversal and inversion symmetries, albeit only in close proximity to a topological transition.

The generically very narrow window of large BCD places significant challenges on its experimental observation. This challenge is crucially addressed through our Floquet approach, which enables convenient, precise access to the topological transition by varying the laser amplitude or quench duration. We find a significant light-enhanced peak for the BCD at a specific critical intensity of incident light, at which there is a light-induced topological band inversion: when the light intensity is subcritical, the system is a Chern insulator, whereas exceeding the critical intensity results in a transition to a normal insulator phase. Conversely, by measuring the BCD peak as a function of light intensity, the location of the topological phase transition point can also be accurately determined. In all, our approach not only precisely assesses a topological transition and its accompanying BCD peak, but also enhances the sensitivity and reproducibility of nonlinear Hall measurements in the larger realm of nonlinear physics83,84.

Particularly, we find that our work and ref. 85 focus on different physics that is distinguished by the magnitude of the frequency of the pumping light. The previous work85 focuses on the nonlinear optical susceptibilities of semiconductors. Notice that the optical susceptibilities require that the frequency of the driving light be in the same order of magnitudes as the bandwidth. It is called a resonant light when its frequency is about the same as the bandwidth. Therefore, the electrons can transition between the conduction band and the valence band, driven by the resonant light. However, in our work, we focus on the off-resonant light, whose frequency is much larger than the bandwidth. In this case, the electrons cannot transition between the conduction band and the valence band, driven by the off-resonant light. Therefore, an effective Floquet Hamiltonian based on a high-frequency expansion method provided in our work is applicable for this off-resonant light situation.

Methods

Nonlinear Hall effect

In this subsection, we will introduce the nonlinear Hall effect, where the transverse electric current contains both linear and quadratic (or even higher) contributions from the external electric field due to higher-order Berry curvature corrections2,3,4,5,8,42,44,48.

In the quantum Hall (or quantum anomalous Hall) effect, under broken time-reversal symmetry, longitudinal current does not flow due to the band gap. Instead, due to topological in-gap states, a transverse linear Hall current density Jy = σxyEx exists at the same a.c. frequency. It is well known that at zero temperature, a perturbative expansion in linear response theory gives the Hall conductance \({\sigma }_{xy}=-\frac{{e}^{2}2\pi }{h}\int\frac{{d}^{2}{{{\bf{k}}}}}{{(2\pi )}^{2}}{\varepsilon }^{xyz}{\Omega }_{{{{\bf{k}}}},z}\), where εxyz is the Levi-Civita anti-symmetric tensor. But the nonlinear Hall response tells of another story: Instead of the usual Ohm’s law, we have a quadratic I-V relation, i.e., the transverse current density is proportional to the second power of the longitudinal electric field, due to high-order Berry curvature-like contributions. Generically, we can write the response to the electric current density as

where {i, j, k, l} ∈ {x, y, z}, E = (Ex, Ey, Ez) is the external electric field; the first term is the linear term with frequency as the external electric field; and the second term is the leading-order nonlinear transverse response with a doubled a.c. frequency that can be measured with a lock-in amplifier. In the following subsubsections, we derive and study the coefficient χijk for the nonlinear Hall effect.

Equations of motion

Under an electric field E, the equations of motion of semi-classical electronic wavepackets are given by56,57,86,87

where both the position r and wave vector k simultaneously characterize the center-of-mass and momentum of a wavepacket, \(\dot{{{{\bf{r}}}}}\) and \(\dot{{{{\bf{k}}}}}\) are their time derivatives, E is the external longitudinal electric field, ϵk is the energy band dispersion, and Ωk is the Berry curvature defined in k space56,57.

Substituting Eq. (27) into Eq. (26), the formula of \(\dot{{{{\bf{r}}}}}\) becomes

where we have defined the wavepacket velocity as56

Boltzmann equation within the relaxation time approximation

In the case of thermal equilibrium without an external field, the distribution function is the Fermi-Dirac distribution function

where β = 1/(kBT) with Boltzmann constant kB and temperature T, and μ is the chemical potential.

When collisions exist, we consider the non-equilibrium distribution function f(r, k, t)

Further, we expand the non-equilibrium distribution as

and obtain

Thus, the Boltzmann equation acts as

where the left side is a drift term and the right side is a collision term.

Under an external electric field E, the drift term of the Boltzmann equation (Eq. (34)) becomes

where we have used \(\frac{\partial f}{\partial {{{\bf{r}}}}}=0\) since the field is spatially homogeneous on the length scale of a wavepacket. We employ a simple relaxation time approximation

Then, the Boltzmann equation (34) becomes

where \({{{{\bf{v}}}}}_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}=\frac{1}{\hslash }{\nabla }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}{\epsilon }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}\).

Furthermore, the Boltzmann equation (37) becomes

Importantly, this allows for a controlled approximation of the distribution function as

where fn refers to the contribution to f that is of the n-order in the field E (and also of eτ/ℏ). Here, we noted that ∂tf0 = 0.

We specialize in an oscillating (i.e., a.c.) electric field, \({{{\bf{E}}}}(t)={E}_{a}^{\omega }(t){{{{\bf{e}}}}}_{a}=\frac{1}{2}{{{\rm{Re}}}}({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{a}{e}^{i\omega t}+{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{a}^{* }{e}^{-i\omega t}){{{{\bf{e}}}}}_{a}={{{\rm{Re}}}}({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{a}{e}^{i\omega t}){{{{\bf{e}}}}}_{a}\), where the driving field oscillates harmonically in time, but it is uniform in space. With the amplitude vector \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{a}\) and frequency ω, we have the linear contribution f14

where we noted that

is still linear in the electric field \({E}_{a}^{\omega }\). Furthermore, the leading-order nonlinear response contribution is given by

where τ is taken to be spatially constant, i.e., \({\partial }_{{k}_{a}}\tau =0\). Note that f2 contains two distinct types of nonlinear contributions, one oscillating at the doubled frequency 2ω and the other static.

Electric current density

Explicitly, from the definition of the non-equilibrium distribution function, we have the electric current density

where V = LD is the volume in D dimensions. As k lives in the lattice Brillouin zone, we should replace the sum over k by the integral \({\sum }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}\to V\int\frac{{d}^{D}{{{\bf{k}}}}}{{(2\pi )}^{D}}\). Substituting Eqs. (28) and (38) into (43), we obtain, to the leading nonlinear order,

Further, we have the b-component in the electric current density

where εabc is the Levi-Civita anti-symmetric tensor; a, b, and c stand for the spatial coordinates x, y, and z,

By defining

where we identify the linear Hall coefficient \({\chi }_{ba}^{(1)}\) and nonlinear Hall coefficients \({\chi }_{ba}^{(0)},{\chi }_{ba}^{(2)}\) as

where \({{{{\bf{v}}}}}_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}=\frac{1}{\hslash }{\nabla }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}{\epsilon }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}\), \({v}_{a}=\frac{1}{\hslash }{\partial }_{{k}_{a}}{\epsilon }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}\), and

Here, we can use

In the above, we have approximated the expressions to the leading order in a small dimensionless parameter \(\frac{e\tau }{\hslash }{{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{a}a\) (with the lattice constant a) that is proportional to τ. Taking the Hamiltonian (14) as an example, the factor \({\partial }_{{k}_{y}}{\epsilon }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{(n)}\) in both Cyx and Uyxx is an odd function of ky, and the factor \({\partial }_{{k}_{x}}{f}_{0}\) in Cyx is an even function of ky. Therefore, the integrand \(({\partial }_{{k}_{y}}{\epsilon }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{(n)})({\partial }_{{k}_{x}}{f}_{0})\) in Cyx is an odd function of ky, which contributes zero with the integral of ky. Similarly, the integrand \(({\partial }_{{k}_{y}}{\epsilon }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{(n)})({\partial }_{{k}_{x}}{\partial }_{{k}_{x}}{f}_{0})\) in Uyxx is an odd function of ky, which also contributes zero with the integral of ky.

Expression for the Floquet Hamiltonian 17

In this subsection, we derive the concrete analytical expressions for the time Fourier components \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{0}\), \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{-n}\), and \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{n}\) that enter the Floquet Hamiltonian (16) of the main text. With \({{{\bf{A}}}}(t)={\tilde{\omega }}^{-1}{E}_{0}(\sin (\tilde{\omega }t),\sin (\tilde{\omega }t+\varphi ))\) and \({A}_{0}=e{E}_{0}/(\hslash \tilde{\omega })\), we have the photon-dressed effective Hamiltonian as

We can extract the time Fourier components in \({{{\mathcal{H}}}}({{{\bf{k}}}},t)\) to give analytical expressions for \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{0}\), \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{-n}\), and \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{n}\) in the Floquet Hamiltonian (16):

Importantly, only the n = 1 commutator in the Floquet-expanded effective Hamiltonian evaluates to nonzero:

where we have used [σa, σb] = 2iεabcσc.

Therefore, the Floquet Hamiltonian can be written as

Inversion symmetry

We show that the Floquet Hamiltonian (70) (or Eq. (17) in the main text) is inversion-symmetric only when t0 = 0. As such, a nonzero t0 is necessary for the BCD.

The Floquet Hamiltonian (70) under inversion transformation becomes

where \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}={\sigma }_{z}\)88 is the inversion operator, and we have used

As a result of Eq. (71), if t0 = 0, we have \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}{{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}^{(F)}({{{\bf{k}}}}){{{{\mathcal{I}}}}}^{-1}={{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}^{(F)}(-{{{\bf{k}}}})\) which satisfies inversion symmetry. However, for t0 ≠ 0, Eq. (71), the extra 2t0kxσ0 term appears due to broken inversion symmetry.

Time-reversal symmetry is broken

Here we show that the Floquet Hamiltonian (70) (or Eq. (17) in the main text) does not satisfy the time-reversal symmetry regardless of the values of t0 and A0.

The Floquet Hamiltonian (70) under time-reversal transformation becomes

where \({{{\mathcal{T}}}}=i{\sigma }_{y}{{{\mathcal{K}}}}\)88 is the time-reversal operator with the complex conjugate operator \({{{\mathcal{K}}}}\) such that \({{{\mathcal{K}}}}{{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}^{(F)}({{{\bf{k}}}}){{{{\mathcal{K}}}}}^{-1}={{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}^{{(F)}^{* }}({{{\bf{k}}}})\), and

Due to the presence of the σ0 and σz terms, Eq. (76) shows that the time-reversal symmetry is broken, i.e., \({{{\mathcal{T}}}}{{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}^{(F)}({{{\bf{k}}}}){{{{\mathcal{T}}}}}^{-1}\ne {{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}^{(F)}(-{{{\bf{k}}}})\) whether t0 and A0 equal zero or not. In the same way, we can show that the original static tilted Dirac Hamiltonian (Eq. (14) in the main text) also does not satisfy the time-reversal symmetry, regardless of whether t0 vanishes.

Competition between the linear and nonlinear current densities

In this subsection, we present more data on the competition between the linear and nonlinear current densities as a function of the Fermi energy at different light intensities.

As shown in Fig. 7, the root-mean-square total current density (Eq. (21) as defined in the main text) along the y direction is plotted as a function of the Fermi energy EF at different light intensities, for fixed electronic field intensity or amplitude \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{x}\)= 0.1 V/m.

The root-mean-squrare total current density (Eq. (21)) along the y direction, averaged over an oscillation period as a function of the Fermi energy EF at different light intensities from (a) in the Chern insulator phase, to (b, c) just before and after the topological phase transition, and (d) in the trivial phase. Very sharp and divergently large current density peaks occur very close to the phase transition. Other parameters are the electronic field intensity \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}_{x}\)=0.1 V/m, φ = π/2 (right-handed circularly polarized light), \(\hslash \tilde{\omega }=1\) eV, t0 = 0.05 eV ⋅ nm, v = 0.1 eV ⋅ nm, α = 0.1 eV ⋅ nm2, m = 0.1 eV, η = − 1, kBT = 0.003 eV, i.e., T ≈ 34.8136 K, τ ≈ 4.12434 × 10−14 s8, and ω = 17.777 Hz8.

When A0 is sufficiently small such that the system is in the Chern insulator phase, i.e., A0 = 0.5 nm−1, there is an obvious nonzero flat \(\sqrt{\langle {J}_{y}^{2}\rangle }\) region as shown in Fig. 7a, which is approximately at the value of the quantized linear Hall current density. The two broad peaks at larger EF (which are in the bulk bands) are not from the nonlinear Hall response, but rather result from the non-quantized Hall response from incomplete band filling.

But when A0 tends to the critical value A0c ≈ 1.0541 nm−1, the gap and hence the flat region disappear, with two very pronounced sharp peaks near the point EF = 0 as shown in Fig. 7b and c. While they are also within the bulk bands, teetering at their edges, the peak values of the root-mean-square current density are far higher. That is due mostly to the nonlinear Hall contribution from divergently large BCD. We emphasize that although such a large nonlinear Hall response seemingly requires fine-tuning to observe, the light amplitude A0 is exactly such a very tunable parameter. When A0 becomes even larger such that the system is in the topologically trivial phase with vanishing Chern number, i.e., A0 = 1.5 nm−1, there is a flat region at zero as shown in Fig. 7d, where both the linear and nonlinear Hall effects essentially vanish.

References

Chang, C.-Z. et al. Experimental observation of the quantum anomalous Hall effect in a magnetic topological insulator. Science 340, 167–170 (2013).

Sodemann, I. & Fu, L. Quantum nonlinear Hall effect induced by Berry curvature dipole in time-reversal invariant materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 216806 (2015).

Du, Z. Z., Wang, C. M., Lu, H.-Z. & Xie, X. C. Band Signatures for Strong Nonlinear Hall Effect in Bilayer WTe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 266601 (2018).

Du, Z. Z., Wang, C. M., Li, S., Lu, H.-Z. & Xie, X. C. Disorder-induced nonlinear Hall effect with time-reversal symmetry. Nat. Commun. 10, 3047 (2019).

Du, Z. Z., Lu, H.-Z. & Xie, X. C. Nonlinear Hall effects. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3, 744 (2021).

Ortix, C. Nonlinear hall effect with time-reversal symmetry: Theory and material realizations. Adv. Quantum Technol. 4, 2100056 (2021).

Bandyopadhyay, A., Joseph, N. B. & Narayan, A. Non-linear hall effects: Mechanisms and materials. arXiv:2401.02282 (2024).

Ma, Q. et al. Observation of the nonlinear Hall effect under time-reversal-symmetric conditions. Nature 565, 337–342 (2019).

Mrudul, M. S. & Dixit, G. High-harmonic generation from monolayer and bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 103, 094308 (2021).

Bharti, A., Mrudul, M. S. & Dixit, G. High-harmonic spectroscopy of light-driven nonlinear anisotropic anomalous Hall effect in a Weyl semimetal. Phys. Rev. B 105, 155140 (2022).

Bharti, A., Ivanov, M. & Dixit, G. How massless are Weyl fermions in Weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. B 108, L020305 (2023).

Lv, Y.-Y. et al. High-harmonic generation in Weyl semimetal β-WP2 crystals. Nat. Commun. 12, 6437 (2021).

Ghimire, S. & Reis, D. A. High-harmonic generation from solids. Nat. Phys. 15, 10–16 (2019).

Nourbakhsh, Z., Tancogne-Dejean, N., Merdji, H. & Rubio, A. High Harmonics and Isolated Attosecond Pulses from MgO. Phys. Rev. Appl. 15, 014013 (2021).

Lee, C. H., Zhang, X. & Guan, B. Negative differential resistance and characteristic nonlinear electromagnetic response of a Topological Insulator. Sci. Rep. 5, 18008 (2015).

Tai, T. & Lee, C. H. Anisotropic nonlinear optical response of nodal-loop materials. Phys. Rev. B 103, 195125 (2021).

Xu, S.-Y. et al. Electrically switchable Berry curvature dipole in the monolayer topological insulator WTe2. Nat. Phys. 14, 900–906 (2018).

Kang, K., Li, T., Sohn, E., Shan, J. & Mak, K. F. Nonlinear anomalous Hall effect in few-layer WTe2. Nat. Mater. 18, 324–328 (2019).

Xiao, J. et al. Berry curvature memory through electrically driven stacking transitions. Nat. Phys. 16, 1028–1034 (2020).

Ye, X.-G. et al. Control over Berry curvature dipole with electric field in WTe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 016301 (2023).

Huang, M. et al. Giant nonlinear Hall effect in twisted bilayer WSe2. Natl Sci. Rev. 10, nwac232 (2023).

Facio, J. I. et al. Strongly enhanced berry dipole at topological phase transitions in BiTeI. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 246403 (2018).

Ho, S.-C. et al. Hall effects in artificially corrugated bilayer graphene without breaking time-reversal symmetry. Nat. Electron. 4, 116–125 (2021).

Duan, J. et al. Giant second-order nonlinear hall effect in twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 186801 (2022).

Huang, M. et al. Intrinsic nonlinear hall effect and gate-switchable berry curvature sliding in twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 066301 (2023).

Sinha, S. et al. Berry curvature dipole senses topological transition in a moiré superlattice. Nat. Phys. 18, 765–770 (2022).

Pantaleón, P. A., Low, T. & Guinea, F. Tunable large Berry dipole in strained twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 103, 205403 (2021).

Zhang, C.-P. et al. Giant nonlinear Hall effect in strained twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 106, L041111 (2022).

Qin, M.-S. et al. Strain tunable Berry curvature dipole, orbital magnetization and nonlinear Hall effect in WSe2 monolayer. Chin. Phys. Lett. 38, 017301 (2021).

Hu, J.-X., Zhang, C.-P., Xie, Y.-M. & Law, K. Nonlinear Hall effects in strained twisted bilayer WSe2. Commun. Phys. 5, 255 (2022).

Lee, J., Wang, Z., Xie, H., Mak, K. F. & Shan, J. Valley magnetoelectricity in single-layer MoS2. Nat. Mater. 16, 887–891 (2017).

Son, J., Kim, K.-H., Ahn, Y. H., Lee, H.-W. & Lee, J. Strain engineering of the berry curvature dipole and valley magnetization in monolayer MoS2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 036806 (2019).

Kumar, D. et al. Room-temperature nonlinear Hall effect and wireless radiofrequency rectification in Weyl semimetal TaIrTe4. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 421–425 (2021).

Shvetsov, O. O., Esin, V. D., Timonina, A. V., Kolesnikov, N. N. & Deviatov, E. Nonlinear Hall effect in three-dimensional weyl and dirac semimetals. JETP Lett. 109, 715–721 (2019).

Zhao, T.-Y. et al. Gate-tunable berry curvature dipole polarizability in dirac semimetal Cd3As2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 186302 (2023).

He, P. et al. Quantum frequency doubling in the topological insulator Bi2Se3. Nat. Commun. 12, 698 (2021).

Dzsaber, S. et al. Giant spontaneous Hall effect in a nonmagnetic Weyl–Kondo semimetal. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 118, e2013386118 (2021).

Tiwari, A. et al. Giant c-axis nonlinear anomalous Hall effect in Td-MoTe2 and WTe2. Nat. Commun. 12, 2049 (2021).

Ma, D., Arora, A., Vignale, G. & Song, J. C. W. Anomalous Skew-scattering nonlinear hall effect and chiral photocurrents in \({{{\mathcal{PT}}}}\)-symmetric antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 076601 (2023).

Das, K., Lahiri, S., Atencia, R. B., Culcer, D. & Agarwal, A. Intrinsic nonlinear conductivities induced by the quantum metric. Phys. Rev. B 108, L201405 (2023).

Liu, H. et al. Intrinsic second-order anomalous hall effect and its application in compensated antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 277202 (2021).

Gao, Y., Yang, S. A. & Niu, Q. Field induced positional shift of bloch electrons and its dynamical implications. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 166601 (2014).

Wang, C., Gao, Y. & Xiao, D. Intrinsic Nonlinear Hall Effect in Antiferromagnetic Tetragonal CuMnAs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 277201 (2021).

Lai, S. et al. Third-order nonlinear Hall effect induced by the Berry-connection polarizability tensor. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 869–873 (2021).

Gao, A. et al. Quantum metric nonlinear Hall effect in a topological antiferromagnetic heterostructure. Science 381, 181 (2023).

Kaplan, D., Holder, T. & Yan, B. Unification of nonlinear anomalous hall effect and nonreciprocal magnetoresistance in metals by the quantum geometry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 026301 (2024).

Wang, N. et al. Quantum-metric-induced nonlinear transport in a topological antiferromagnet. Nature 621, 487–492 (2023).

Chen, R., Du, Z. Z., Sun, H.-P., Lu, H.-Z. & Xie, X. C. Nonlinear hall effect on a disordered lattice. Phys. Rev. B 110, L081301 (2024).

Atencia, R. B., Xiao, D. & Culcer, D. Disorder in the nonlinear anomalous Hall effect of \({{{\mathcal{PT}}}}\)-symmetric Dirac fermions. Phys. Rev. B 108, L201115 (2023).

Magnus, W. On the exponential solution of differential equations for a linear operator. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. 7, 649 (1954).

Blanes, S., Casas, F., Oteo, J.-A. & Ros, J. The magnus expansion and some of its applications. Phys. Rep. 470, 151 (2009).

Lee, C. H., Ho, W. W., Yang, B., Gong, J. & Papić, Z. Floquet mechanism for non-abelian fractional quantum hall states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 237401 (2018).

Schliemann, J. & Loss, D. Anisotropic transport in a two-dimensional electron gas in the presence of spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. B 68, 165311 (2003).

Sinitsyn, N. Semiclassical theories of the anomalous hall effect. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 20, 023201 (2007).

Mahan, G. D.Many-particle physics (Springer Science & Business Media, 2013).

Xiao, D., Chang, M.-C. & Niu, Q. Berry phase effects on electronic properties. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1959–2007 (2010).

Shen, S.-Q.Topological insulators (Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd., 2017).

Kubo, R. Statistical-mechanical theory of irreversible processes. I. General theory and simple applications to magnetic and conduction problems. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 12, 570–586 (1957).

Thouless, D. J., Kohmoto, M., Nightingale, M. P. & den Nijs, M. Quantized hall conductance in a two-dimensional periodic potential. Phys. Rev. Lett. 49, 405–408 (1982).

Kubo, R., Yokota, M. & Nakajima, S. Statistical-mechanical theory of irreversible processes. II. Response to thermal disturbance. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 12, 1203–1211 (1957).

Qin, F., Lee, C. H. & Chen, R. Light-induced half-quantized hall effect and axion insulator. Phys. Rev. B 108, 075435 (2023).

Qin, F., Shen, R., Li, L. & Lee, C. H. Kinked linear response from non-Hermitian cold-atom pumping. Phys. Rev. A 109, 053311 (2024).

Muechler, L., Alexandradinata, A., Neupert, T. & Car, R. Topological nonsymmorphic metals from band inversion. Phys. Rev. X 6, 041069 (2016).

Sie, E. J., Rohwer, T., Lee, C. & Gedik, N. Time-resolved XUV ARPES with tunable 24–33 eV laser pulses at 30 meV resolution. Nat. Commun. 10, 3535 (2019).

Qin, F., Lee, C. H. & Chen, R. Light-induced phase crossovers in a quantum spin Hall system. Phys. Rev. B 106, 235405 (2022).

Qin, F., Chen, R. & Lu, H.-Z. Phase transitions in intrinsic magnetic topological insulator with high-frequency pumping. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 34, 225001 (2022).

Oka, T. & Aoki, H. Photovoltaic Hall effect in graphene. Phys. Rev. B 79, 081406 (2009).

Wang, Z. F., Liu, Z., Yang, J. & Liu, F. Light-Induced Type-II Band Inversion and Quantum Anomalous Hall State in Monolayer FeSe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 156406 (2018).

Bao, C., Tang, P., Sun, D. & Zhou, S. Light-induced emergent phenomena in 2D materials and topological materials. Nat. Rev. Phys. 4, 33–48 (2022).

Sentef, M. et al. Theory of Floquet band formation and local pseudospin textures in pump-probe photoemission of graphene. Nat. Commun. 6, 7047 (2015).

Liu, J. A short review on first-principles study of gapped topological materials. Comput. Mater. Sci. 195, 110467 (2021).

Paschotta, R.Encyclopedia of laser physics and technology (Wiley-VCH Weinheim, 2016).

Buchkov, K. et al. Anisotropic optical response of wte2 single crystals studied by ellipsometric analysis. Nanomaterials 11, 2262 (2021).

Wang, Y., Steinberg, H., Jarillo-Herrero, P. & Gedik, N. Observation of Floquet-Bloch states on the surface of a topological insulator. Science 342, 453–457 (2013).

Mahmood, F. et al. Selective scattering between Floquet–Bloch and Volkov states in a topological insulator. Nat. Phys. 12, 306–310 (2016).

McIver, J. W. et al. Light-induced anomalous Hall effect in graphene. Nat. Phys. 16, 38–41 (2020).

Zhou, S. et al. Pseudospin-selective floquet band engineering in black phosphorus. Nature 614, 75–80 (2023).

Kobayashi, Y. et al. Floquet engineering of strongly driven excitons in monolayer tungsten disulfide. Nat. Phys. 19, 171–176 (2023).

Castelvecchi, D. & Sanderson, K. Physicists who built ultrafast ‘attosecond’lasers win Nobel Prize. Nature 622, 225–227 (2023).

Paul, P.-M. et al. Observation of a train of attosecond pulses from high harmonic generation. Science 292, 1689–1692 (2001).

Hentschel, M. et al. Attosecond metrology. Nature 414, 509–513 (2001).

Kruchinin, S. Y., Krausz, F. & Yakovlev, V. S. Colloquium: Strong-field phenomena in periodic systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 021002 (2018).

He, P. et al. Nonlinear planar Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 016801 (2019).

Tuloup, T., Bomantara, R. W., Lee, C. H. & Gong, J. Nonlinearity induced topological physics in momentum space and real space. Phys. Rev. B 102, 115411 (2020).

Aversa, C. & Sipe, J. E. Nonlinear optical susceptibilities of semiconductors: Results with a length-gauge analysis. Phys. Rev. B 52, 14636–14645 (1995).

Chang, M.-C. & Niu, Q. Berry Phase, Hyperorbits, and the Hofstadter Spectrum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 1348–1351 (1995).

Sundaram, G. & Niu, Q. Wave-packet dynamics in slowly perturbed crystals: Gradient corrections and Berry-phase effects. Phys. Rev. B 59, 14915–14925 (1999).

Chen, R. Y. et al. Magnetoinfrared spectroscopy of landau levels and zeeman splitting of three-dimensional massless dirac fermions in ZrTe5. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 176404 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge helpful discussions with Hao-Jie Lin and Xiao-Bin Qiang. C.H.L. and F.Q. acknowledge support from the QEP2.0 Grant from the Singapore National Research Foundation (Grant No. NRF2021-QEP2-02-P09) and the Singapore Ministry of Education Academic Research Fund Tier-II Grant (Award No. MOE-T2EP50222-0003). R.C. acknowledges the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12304195) and the Chutian Scholars Program in Hubei Province.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.Q. performed theoretical calculations and wrote parts of the manuscript. R.C. assisted in improving the theoretical analysis and numerical calculations. C.H.L. supervised the project, wrote the manuscript and provided technical guidance. All authors discussed the analytical and numerical results and contributed to all aspects of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks Gopal Dixit and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qin, F., Chen, R. & Lee, C.H. Light-enhanced nonlinear Hall effect. Commun Phys 7, 368 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-024-01820-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-024-01820-5