Abstract

Data-driven approaches offer novel opportunities for improving the performance of turbulent flow simulations, which are critical to wide-ranging applications from wind farms and aerodynamic designs to weather and climate forecasting. However, current methods for these simulations often require large amounts of data and computational resources. While data-driven methods have been extensively applied to the continuum Navier-Stokes equations, limited work has been done to integrate these methods with the highly scalable lattice Boltzmann method. Here, we present a physics-informed neural network framework for improving lattice Boltzmann-based simulations of near-wall turbulent flow. Using a small amount of data and integrating physical constraints, our model accurately predicts flow behaviour at a wide range of friction Reynolds numbers up to 1.0 × 106. In contradistinction with other models that use direct numerical simulation datasets, this approach reduces data requirements by three orders of magnitude and allows for sparse grid configurations. Our work broadens the scope of lattice Boltzmann applications, enabling efficient large-scale simulations of turbulent flow in diverse contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wall-modelled large-eddy simulations (WMLES) are crucial within industrially designed aerodynamics-driven applications such as aircraft, high-speed trains and wind turbines1,2. These simulations provide a balance between computational efficiency and the resolution of flow physics. Although large-eddy simulations (LES) require fewer computational grid points than direct numerical simulations (DNS), wall-resolved LES necessitates fine grid resolution near the wall. The grid point requirement scales with O(Re13/7)3,4,5. To expedite the aerodynamics-driven design process, WMLES emerges as a viable alternative to reduce computational costs. Accurate modelling of the near-wall fluid field is imperative to maintain coarse-grained near-wall field resolution without compromising the accuracy of far-field physics. Traditionally, the near-wall field is modelled using law of the wall or by solving thin-boundary-layer equations6,7,8,9. In the current era of big data, the increasing availability of DNS data promotes machine learning and data-driven approaches to accurately capture the physics of coarse-grained models10.

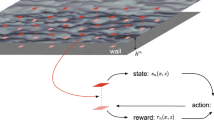

Data-driven approaches based on machine learning (ML) have been widely used in industrial processes11, computer vision12 and control-related problems13,14. Recently, the data-driven approach has been employed for subgrid scale (SGS) modelling15,16,17,18,19 and near wall modelling20,21. A common limitation of data-driven approaches is their lack of generality which stems from an inadequate understanding of the underlying physics. This limitation is evident when trained ML-based models show excellent ability to predict scenarios they have been trained on, sometimes referred to as “seen scenarios” or “interpolated schemes”, yet struggle to predict “unseen scenarios” or “extrapolated schemes”, which fall outside the scope of their training data. A physics-informed data-driven approach offers a way of more effectively utilising datasets by embedding physical principles within the training process. Numerous studies have successfully implemented Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) for investigating turbulent flows using DNS data21,22,23,24. While effective, these methods rely on DNS data which is not only computationally demanding to produce but also requires substantial storage capacity. In contrast, Bae and Koumoutsakos20 employed multi-agent reinforcement learning to model the near-wall field in turbulent flows using hybrid Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS)/LES data. The process of generating training data engenders a notable reduction in both computational and storage demands, particularly when contrasted with techniques that depend on DNS data. Such methods are invariably based on the Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) approaches to solve the Navier-Stokes equations. The Lattice Boltzmann Method (LBM) by contrast, is recognized for its ability to model complex fluid phenomena across multiple scales, from microscopic25,26,27,28,29 to macroscopic30,31,32,33. LBM is known as a kinetic-driven approach. Instead of solving the Navier-Stokes (NS) equations, LBM offers an alternative to conventional CFD methods by solving the Boltzmann equation at a mesoscopic level33,34,35,36. LBM is favoured for its parallelization-friendly characteristics, primarily due to the localized updating of discrete single-particle distribution functions. Through the application of a Chapman-Enskog analysis to the Boltzmann equation, it is possible to derive the Navier-Stokes equations. Hou et al.30 were instrumental in integrating the LES-based approach with LBM, particularly in modelling effective turbulent viscosity. As for near-wall modelling in LBM, Malaspinas et al.37 demonstrated the successful reconstruction of first-layer near-wall velocity with a regularized scheme38 using the Musker wall function or logarithmic law39. Subsequent research focused on reconstructing the velocity field or modelling velocity bounce-back37,40,41,42. The forcing-based method, noted for its simplicity, has also been applied in modelling the near-wall fluid field43,44.

To date, existing data-driven wall models have been developed within the Navier-Stokes framework. However, there is no established data-driven approach that models the near-wall fluid field using the LBM framework. This paper presents a methodology for utilizing both grid-intensive and grid-sparse improved delayed detached eddy simulation (IDDES)45 data to develop a generalized neural network (NN) wall model within the lattice Boltzmann framework. In the current study, IDDES data is trained at friction Reynolds number Reτ = 5200. Subsequently, this data is applied to the NN wall model for turbulent channel flow, incorporating a synthetic turbulent generator (STG) at the inlet as described by Xue et al.46, at Reτ = 1000, 2000, 5200. The results show good agreement with DNS data at coarse resolutions with the channel height of 20 lattice grid separations. To highlight the model’s generality, we further validate our NN wallmodel for the LBM based turbulent channel flow at the friction Reynolds number Reτ = 1.0 × 105 and Reτ = 1.0 × 106. It is noteworthy that the grid-intensive data used in this study amounts to only 45 megabytes (MBs) while the grid-sparse data is even more compact, requiring just 6.4 MBs, in contrast to DNS data, which can range from hundreds of gigabytes (GBs) to several terabytes (TBs). Compared to conventional approaches, which often necessitate extensive physical knowledge and extensive implementation effort to reconstruct near-wall population distributions as noted by Malaspinas et al.37, our data-driven approach reduces the knowledge gap by utilizing macroscopic data derived from solving the Navier-Stokes equations. We emphasize the benefits of integrating data-driven methodologies with physical insights from macro-scale approaches to enhance near-wall dynamics within the lattice Boltzmann framework. This integration effectively leverages CFD data for NN-based wall modelling, which can potentially apply to more complex scenarios, such as near-wall fields in curved geometries in LBM.

Results

Physics-informed neural network wall modelling framework for LBM

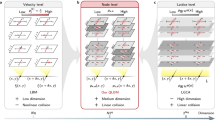

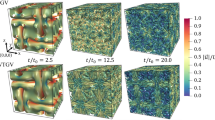

In this subsection, we demonstrate the neural network wall model framework for the LBM. We simulate turbulent channel flow equipped with the STG at the inlet, while the outlet features a sponge region46. The coordinates of the LBM channel flow are denoted as x, y, z, corresponding to the stream-wise, vertical, and span-wise directions, respectively. The domain dimensions of the turbulent channel flow are Lx × Ly × Lz, measuring 320 × 20 × 16 lattice Boltzmann units (LBU). The upper and lower boundaries of the channel employ a free-slip condition. The first layer near the wall is modelled by the pre-trained neural networks. The first step is to train the neural networks which is guided by the macroscopic scale physical data obtained from IDDES simulation. As shown in Fig. 1 (a), we uniformly sample the upper and lower panels of the IDDES periodic channel flow45 at grid points where y+ < 200. Here, y+ represents the dimensionless wall-normal distance, defined as \({y}^{+}=\frac{y{u}_{\tau }}{\nu }\), where ν denotes the kinematic viscosity and uτ is the shear velocity. We ensure consistency in the sampling locations across different instantaneous snapshots for the channel flow simulations. The IDDES simulation of turbulent channel flow is conducted at Reτ = 5200. The neural network has two inputs, which are \(\frac{u}{1000y}\) and \(\log \left(\frac{y}{{y}_{{{{\rm{ref}}}}}}\right)/u\), with u as the near-wall physical velocity and y as the grid physical height and one output which is the shear velocity uτ. A detailed description can be found in Section “Physics-informed neural networks for LBM-based wall model”. Owing to the varying grid density near the wall, the sampled data may range from dense to sparse. Our primary objective is the accurate prediction of the shear velocity to reliably estimate wall velocities. It is crucial to recognize that the grids used in IDDES are distinct from those in lattice Boltzmann configurations. In contrast to conventional CFD methodologies, the LBM utilizes a uniform grid structure and is formulated with dimensionless variables. This distinction in grid structure necessitates precise capture of the physics inherent in the near-wall region. The second step is to integrate the pre-trained NN-based model with the LBM channel flow solver. Figure 1 (b) illustrates the pipeline for applying a neural network wall model to LBM turbulent channel flow. The near-wall region is modelled using a volume force calculated by the prediction of neural networks. The process involves converting LBM data into PINNs feature input with the help of a feature builder, followed by predicting the feature output of shear velocity. Subsequently, this prediction is converted back into LBM data with the help of a data builder to compute the resistive volume force, thereby correcting near-wall velocities. In the feature builder, a normalizer and LBM-to-physical unit converter are utilized to ensure that input values consistently fall within the range \(\left[0,1\right]\). The data builder consists of a denormalizer and a physical-to-LBM unit converter (see Section of “Physics-informed neural networks for LBM-based wall model”).

Diagram of the physics-informed neural networks for wall modelling and implementation for the lattice Boltzmann method trained by IDDES data. a the training data is obtained from the upper and lower near-wall region of a periodic channel flow simulation. We use NN to predict the shear velocity which can be used by the wall model. b LES based LBM channel flow simulation is performed; on the first layer of the wall, we use the LBM data as the input. With the help of the pre-trained PINNs wall model, we can predict LBM shear velocity in order to calculate the resistance wall force Fw for the wall model.

Dense-data wall model vs sparse-data wall model

Due to the nature of the IDDES simulation, the original IDDES data may consist of “gaps” in the vertical direction near the wall. As shown in Fig. 2a, blue dots represent dense data, indicating densely arranged grids below y+ < 200 near the wall. The application of neural networks to learn wall functions from data is demonstrated. The red line confirms that NNs accurately capture the wall functions at y+ < 200. This NN model, which requires no PDF data correction, is thus referred to as the “NNWC” model (Neural Networks Without PDF Correction). The NNWC model’s predictions correspond closely with the IDDES data. In Fig. 2 (b), red dots represent sparsely configured grids near the wall, enhancing computational efficiency. However, the direct application of the NNWC model to sparse data, as depicted by the dark green line, risks overfitting and creating a staggered wall function. To mitigate this, we apply PDF corrections (described as the “NNPC” model - Neural Networks with PDF Correction), minimizing the impact of “gap” regions between data groups during training (see Section of “Neural network training”). As shown by the blue line, the NNPC model can precisely capture the law of the wall even with sparse training data. We further checked the performance of the NNPC and NNWC model regarding shear velocity prediction using IDDES data and LBM data.

Diagram of neural networks learning law of the wall at y+ < 200 with IDDES data. a demonstrates dense data configuration (blue dots) with u+ as function of y+. NNWC prediction is illustrated by the red line. b demonstrates sparse data configuration (red dots) comparing NNWC (green line) and NNPC (blue line) predictions.

Figure 3a depicts the Absolute Relative Error (ARE) in predicting shear velocity, uτ, using neural networks on IDDES data, comparing both the NNWC and NNPC models. The blue curve illustrates the ARE of the NNWC model’s predictions for dense data. This error decreases to 2% around y+ ≈ 200, reflecting the model’s training on datasets below y+ = 200. Beyond this point, the ARE rises to 7% but remains stable up to y+ = 5000. Conversely, the red curve represents the ARE of the NNPC model for sparse data. With the application of the PDF correction, the ARE drops below 1% near y+ ≈ 200. Despite a slight increase in ARE beyond y+ = 200, it stabilizes at around 4% for y+≤5000. The NNPC model demonstrates an accuracy improvement of 3% over the NNWC model. We also tested the model using data in lattice Boltzmann units to predict the shear velocity uτ,lbm, aiming to mimic wall models integrated with the LBM solver. Figure 3b shows the LBM velocity in the channel flow, ulbm, as a function of the predicted shear velocity uτ,lbm. Red triangles represent NNPC predictions, while green triangles are indicative of NNWC predictions. Both models exhibit good alignment with the LBM data. Based on the findings in Figs. 2 and 3, the NNPC model is selected for interpolation and extrapolation tests in LBM channel flow simulations.

a absolute relative error (ARE) for uτ prediction based on IDDES simulations for y+ up to 5200 with or without PDF correction. Blue and red lines represent the NNWC and NNPC error respectively. b LBM data prediction on shear velocity uτ,lbm with input of LBM velocity ulbm at y+ = 260 for the channel flow simulation at Reτ = 5200. Blue dots represents the LBM data, the NNPC and NNWC model predictions are represented by the red and green triangles respectively.

Interpolation validation for the neural network wall model up to R e τ = 5200

The turbulent channel flow serves as the validation case for the neural network wall model. In this setup, the channel flow employs a LBM-based synthetic turbulence generator at the inlet, as described in46, and incorporates a sponge layer at the outlet. The volume force, Fw(x, t), exerted on the first layer of cells near the wall, can be characterized at location x as

where τw can be obtained by shear velocity and density: \({\tau }_{{{{\rm{w}}}}}({{{\bf{x}}}},t)={u}_{\tau ,{{{\rm{lbm}}}}}^{2}({{{\bf{x}}}},t)\rho ({{{\bf{x}}}},t)\). A is the acting area. The height of the channel is set to 20 LBU. Consequently, the y+ values of the first cell layer for friction Reynolds numbers Reτ = 1000, 2000, and 5200 are approximately 50, 100, and 260, respectively. These results are benchmarked against DNS data from refs. 47,48. Owing to the rapid convergence characteristics of the turbulence generator46, simulations are executed at various friction Reynolds numbers. Each simulation runs for a total duration of 12 domain-through-times (12T), with statistical analyses commencing post 2T. The cross-section sampling is performed at x/δ = 8 to ensure robust statistical properties of the turbulence, where δ is the turbulent boundary layer thickness and is equal to δ = 10 LBU for the channel flow case. Figure 4a illustrates the mean flow velocity u+ of LBM turbulent flow as a function of y+. The red, blue, and green dots correspond to LBM simulations at Reτ = 1000, 2000, 5200, respectively. The black dotted line represents the DNS data at Reτ = 5200. The results of our LBM NNPC-based wall model demonstrate good alignment with the DNS data. Subsequently, the turbulent shear stress \({\left\langle {u}^{{\prime} }{v}^{{\prime} }\right\rangle }^{+}\) is compared with the DNS reference data. Figure 4b displays \({\left\langle {u}^{{\prime} }{v}^{{\prime} }\right\rangle }^{+}\) as a function of y/δ for Reτ = 1000, 2000, 5200. The red, blue, and green dotted lines represent the DNS references47,48, while the corresponding coloured points denote the LBM NNPC-based wall model results. Discrepancies are observed in the first three cells near the wall, attributable to coarse-grained resolution issues, given that the channel height comprises only 20 lattice units. Beyond the fourth grid cell, the LBM results closely match the DNS data, indicating the efficacy of our wall model in accurately capturing the physics of the turbulent stress tensor in channel flow.

a Mean velocity, u+, as function of y+. The black dotted line represents the DNS reference at Reτ = 5200. The red, blue and green triangles are NNPC-LBM results at Reτ = 1000, 2000, 5200 respectively. b \({\left\langle {u}^{{\prime} }{v}^{{\prime} }\right\rangle }^{+}\) as function of y/δ. The red, blue and green dotted lines are DNS reference at Reτ = 1000, 2000, 5200. The red and blue triangles and the green dots are NNPC-LBM results at Reτ = 1000, 2000, 5200 respectively.

Extrapolation studies for the neural network wall model up to R e τ = 1.0 × 106

To demonstrate the generality of our NNPC-based wall model, we extended its application to friction Reynolds numbers Reτ = 1.0 × 105 and Reτ = 1.0 × 106, which are two orders of magnitude higher than those considered in previous LBM-base wall model studies37,40,41,42,49. For channel flow simulations at these elevated Reynolds numbers, the first cell layer of the NNPC-based model corresponds to approximately y+ = 5000 and y+ = 50000, respectively, exceeding the range of the initial training dataset.

Figure 5 presents u+ as a function of y+ for Reτ = 1.0 × 105 and 1.0 × 106. The black dotted line represents the DNS reference at Reτ = 5200. Due to the absence of DNS data for these higher Reynolds numbers, the green dotted line depicts the universal logarithmic wall law (Log WL), which is expressed as

where κ is chosen to be 0.42 and B is set to 5.2. The purple and yellow dots represent the LBM-based NNPC wall model results at Reτ = 1.0 × 105 and Reτ = 1.0 × 106, respectively. Results from the channel flow simulations under Reτ = 5200 are also included in the figure, depicted in faded colours for comparative purposes. We also compared the reference from an existing LBM wall model (LBM-WM)37 at Reτ = 2.0 × 104 which is the highest reference friction Reynolds number within the LBM literature. The black open circles show that LBM-WM turbulent channel flow results overestimate u+ against the scaling law at Reτ = 2.0 × 104. Although our neural network model is primarily guided by macroscopic data, as a kinetic approach, our NNPC-LBM wall model results align well with the logarithmic wall law up to Reτ = 1.0 × 106. This concordance highlights the versatility and effectiveness of our NNPC-based wall model within the LBM framework.

Mean velocity u+ as function of y+ at Reτ = 1.0 × 105 (purple triangles) and Reτ = 1.0 × 106 (yellow triangles). The black open circles denote the existing LBM velocity wall model based on the reference data37. The green dotted line is the log wall law satisfying Eq. (2), for which DNS data is only available up to Reτ = 5200. The faded red and blue triangles and green dots are NNPC-LBM results at Reτ = 1000, 2000, 5200 respectively.

Conclusions

This paper introduces a physics-informed neural network wall model tailored for the lattice Boltzmann method. The model was trained using IDDES channel flow simulations at Reτ = 5200. Due to grid sparsity near the wall, the training dataset encompasses both dense and sparse data configurations below y+ = 200. Implementing PDF corrections leads to a 2% reduction in error compared to models without such corrections, yielding an approximate absolute relative error of 4% for y+ > 1000. We evaluated our NNPC-based wall model in LBM channel flow simulations using STG as the inlet. Despite the coarse-grained nature of LBM channel flow, our simulation results align well with DNS data up to Reτ = 5200. It is noteworthy that previous LBM channel flow studies can only validate the wall model up to Reτ = 20, 00037. We further validate our NNPC-based LBM wall model with the logarithmic wall law at scale of Reτ = 106 where DNS data is not available. This evidence supports the conclusion that our NNPC-based wall model is effective for arbitrarily high friction Reynolds numbers. It should be noted that investigations beyond this range were not conducted as they exceed typical application requirements. Nonetheless, we are confident that the model will adhere to the logarithmic wall law even at higher friction Reynolds numbers. As a concluding remark, our NNPC-based wall-model demonstrates effective performance on coarse-grained grids near the wall. It is versatile enough to be applied to flows at arbitrarily high Reynolds numbers, opening up a broad array of aerodynamics-related industrial applications.

Methods

The multiple-relaxation time lattice Boltzmann method

This study employs a three-dimensional (3D) Lattice Boltzmann model featuring 19 discretized directions, known as the D3Q19 model. The lattice cell is specified by its position x and time t, and is characterized by a discretized velocity set ci where i ∈ {0, 1, …, Q − 1} with Q = 19. Macro-scale quantities such as density, momentum, and momentum flux tensors are derived from the distribution function fi(x, t), the discrete velocities ci, and the volume acceleration, g,:

The evolution equation for the distribution functions, accounting for collision and forcing, can be expressed as:

where Ω denotes the multiple relaxation time (MRT) collision kernel, defined as Ω = M−1SM50. The matrix S is a diagonal matrix comprising relaxation frequencies for different moments, expressed as S = diag{ω0, ω1, …, ωQ−1}. The matrix M represents the transformation matrix that converts population space to moment space, derived using the Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization process (See Supplementary Information S1.). In Eq. (6), Δt symbolizes the lattice Boltzmann time step, which is standardized to unity. The frequency ωi corresponds to the inverse of relaxation time τi. It is important to note that we equate τk = τ9 = τ11 = τ13 = τ14 = τ15, all of which are associated with the kinematic viscosity ν, which is

with cs representing the speed of sound, and \({c}_{s}^{2}\) equating to 1/3 in LBU. The other relaxation parameters, which are not governed by the viscosity, are set as follows:

F(x, t) in Eq. (6) is the vector of Fi(x, t) which is the force acting on the fluid cell51:

Smagorinsky subgrid-scale modelling

In this part, we summarize the lattice-Boltzmann-based Smagorinsky Subgrid Scale (SGS) LES techniques. Within the LBM framework, the effective viscosity νeff30,52,53 is modelled as the sum of the molecular viscosity, ν0, and the turbulent viscosity, νt:

where \(\left\vert \bar{{{{\bf{S}}}}}\right\vert\) is the filtered strain rate tensor, Csmag is the Smagorinsky constant, Δ represents the filter size which is set to 1 LBU. The Smagorinsky constant for this study is set to Csmag = 0.01.

Synthetic turbulence generator formulation

The synthetic turbulence generator requires a velocity field given by a k − ε Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) simulation54. The total velocity uin(x, t) at the inlet is given by

where uRANS is the velocity vector obtained from a RANS simulation, then the interpolated velocity will be applied on LBM grid in case of grid resolution differences46. The STG generates the velocity fluctuations \({{{{\bf{u}}}}}^{{\prime} }({{{\bf{x}}}},t)\) at the cell x at time t:

The time-averaged velocity fluctuation is zero, i.e., \(\langle {{{{\bf{u}}}}}^{{\prime} }({{{\bf{x}}}},t)\rangle =0\). The term aαβ represents the Cholesky decomposition of the Reynolds stress tensor. The fluctuations \({{{{\bf{v}}}}}^{{\prime} }({{{\bf{x}}}},t)\) are imposed by N Fourier modes. A detailed descriptions of this process are available in Xue et al.46.

Physics-informed neural networks for LBM-based wall model

We use a NN model that contains several fully connected hidden layers with the tanh function as an activation function. Generally, the input is reformulated so that it provides crucial physics and helps to find a convergence in the optimization process when training the model. We use IDDES data to learn law of the wall, then we apply the data-driven wall model within the LBM-based framework. It is important to note that LBM is based on dimensionless units instead of the physical units, thus it is important to guarantee the correct physics can be transferred via this framework. The feature builder and data builder ensure the correctness of the unit conversion, normalization and denormalization process. Moreover, the IDDES data intensity near the wall is much lower compared with the DNS data. We apply two different approaches to estimate the wall model. One is referred to as the “NNWC” model (Neural Networks Without PDF Correction), however; due to varying grid density near the wall in IDDES data, “gaps” may exist between data points. Thus, we designed a second model with the grid intensity PDF correction denoted as “NNPC” (Neural Networks with PDF Correction). The detailed description of our NN models is provided in Table 1. In the first row, both the NNPC and NNWC models are tested on predicting u+, using y+ as the input. The results are presented in Fig. 2. Note that both input and output are normalized and denormalized accordingly before entering and exiting the data-driven models. In the second row, to ensure we identify a model with the generality to predict shear velocity uτ, we need actual physics-informed input. With the assistance of our feature builder, we first transform our LBM data into physical data as guided by Supplementary Information S2. Subsequently, we select \(\frac{u}{1000y}\) and \(\log \left(\frac{y}{{y}_{{{{\rm{ref}}}}}}\right)/u\) to capture the log-scale slope of the logarithmic wall law as described in Eq. (2). Here, \({y}_{{{{\rm{ref}}}}}=\frac{1}{R{e}_{\tau }}\) serves as the reference distance, correlated with Reτ, to ensure generality. The feature builder then normalizes the input accordingly. This pair of variables is sufficiently informative to elucidate the relative relationships between u and y, and robust enough for applying the scaling law. Additionally, the stability of these variables across varying Reτ ensures their reliability over different flow regimes. The model outputs a value in the interval [0,1]. Through the denormalization process, this output is linearly mapped to [\({u}_{\tau ,\min }\), \({u}_{\tau ,\max }\)] for further application.

Neural network training

We trained the PINNs model in a supervised fashion, with a loss function \({{{\mathcal{L}}}}\), consisting of L2 norm and a weight function. The model is trained by a sample of size N, with a predicted vector XPINNs and target vector Y, the total loss yields:

Here the weight function \({w}_{{{{\rm{loss}}}}}=1/\left[{P}_{r}\left({{{{\bf{X}}}}}_{{{{\rm{PINNs}}}}}\right)+\epsilon \right]\) compensates for the gaps in data points (as shown in Fig. 2 (a)). The constant ϵ = 10−6 avoids infinite value of the weight function. To provide a general solution to deal with the arbitrary “gap” on data sample, the weight function is also learned during the training process. An M-dimensional input data with N sample points is firstly normalized and linearly projected into interval [0,1]. Here, the M is a number of inputs which is set to 2. The data range across each dimension is discretized into J uniform segments. Therefore, the likelihood of a data point being located in the jth segment of the ith dimension is quantified as

where Ni,j denotes the number of training data falls in the jth segment in ith dimension. We use the expression

to denote the relative possibility of a data point that falls in the (j1, j2. . . jM) segment. We pragmatically used J = 100 in the training phase.

The sparse dataset consists of a total of 10,500 input-output pairs. Data are sampled from 100 uncorrelated snapshots in time. In each snapshot, we select 15 out of 105 uncorrelated locations on the x − z plane at both the top and bottom of the channel. At each location, we sample 7 cells from the second to the eighth layer from the wall, vertically positioned within 28 < y+ < 150. For the model trained on dense data, the dataset comprises 9600 input-output pairs, also sampled from 100 uncorrelated snapshots. In each snapshot, we select 8 out of 400 uncorrelated locations on both the top and bottom planes. We sample the 12 cells from the 9th to the 20th closest to the wall, vertically located within 30 < y+ < 180. A detailed description of the y+ values at each level is depicted in Table 2. We adopted a training-to-test ratio of 80% to 20%. The training process employs the Adam optimization algorithm, utilizing a periodic time step across 300 epochs. In terms of training effort, the lightweight nature of the IDDES data allows for the training process to be efficiently conducted on a laptop equipped with an i7-14650HX CPU using PyTorch, with results obtainable within 20 minutes. Once the training process is completed, we can integrate the data-driven wall-model into the solver with PyTorch C++ API.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Information. The training data set for sparse data and dense data can be found on University College London Centre for Computational Science GitHub page55.

Code availability

The training code and data set for sparse data and dense data can be found at the University College London Centre for Computational Science GitHub page56

References

Porté-Agel, F., Wu, Y.-T., Lu, H. & Conzemius, R. J. Large-eddy simulation of atmospheric boundary layer flow through wind turbines and wind farms. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 99, 154–168 (2011).

Mehta, D., Van Zuijlen, A., Koren, B., Holierhoek, J. & Bijl, H. Large Eddy Simulation of wind farm aerodynamics: A review. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 133, 1–17 (2014).

Chapman, D. R. Computational aerodynamics development and outlook. AIAA J. 17, 1293–1313 (1979).

Choi, H. & Moin, P. Grid-point requirements for large eddy simulation: Chapman’s estimates revisited. Phys. Fluids 24, 011702 (2012).

Yang, X. I. & Griffin, K. P. Grid-point and time-step requirements for direct numerical simulation and large-eddy simulation. Phys. Fluids 33, 015108 (2021).

Schumann, U. Subgrid scale model for finite difference simulations of turbulent flows in plane channels and annuli. J. Comput. Phys. 18, 376–404 (1975).

Park, G. I. & Moin, P. An improved dynamic non-equilibrium wall-model for large eddy simulation. Phys. Fluids 26, 015108 (2014).

Larsson, J., Kawai, S., Bodart, J. & Bermejo-Moreno, I. Large eddy simulation with modeled wall-stress: recent progress and future directions. Mech. Eng. Rev. 3, 15–00418 (2016).

Bose, S. T. & Park, G. I. Wall-modeled large-eddy simulation for complex turbulent flows. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 50, 535–561 (2018).

Brunton, S. L., Noack, B. R. & Koumoutsakos, P. Machine learning for fluid mechanics. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 52, 477–508 (2020).

Yin, S., Ding, S. X., Xie, X. & Luo, H. A review on basic data-driven approaches for industrial process monitoring. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 61, 6418–6428 (2014).

Gopalakrishnan, K., Khaitan, S. K., Choudhary, A. & Agrawal, A. Deep convolutional neural networks with transfer learning for computer vision-based data-driven pavement distress detection. Constr. Build. Mater. 157, 322–330 (2017).

Ding, S. X. Data-driven design of fault diagnosis and fault-tolerant control systems (Springer, London, 2014).

Hou, Z.-S. & Wang, Z. From model-based control to data-driven control: Survey, classification and perspective. Inf. Sci. 235, 3–35 (2013).

Sarghini, F., De Felice, G. & Santini, S. Neural networks based subgrid scale modeling in large eddy simulations. Comput. fluids 32, 97–108 (2003).

Gamahara, M. & Hattori, Y. Searching for turbulence models by artificial neural network. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2, 054604 (2017).

Wu, J.-L., Xiao, H. & Paterson, E. Physics-informed machine learning approach for augmenting turbulence models: A comprehensive framework. Phys. Rev. Fluids 3, 074602 (2018).

Xie, C., Wang, J., Li, H., Wan, M. & Chen, S. Artificial neural network mixed model for large eddy simulation of compressible isotropic turbulence. Phys. Fluids 31, 085112 (2019).

Cai, S. et al. Flow over an espresso cup: inferring 3-D velocity and pressure fields from tomographic background oriented Schlieren via physics-informed neural networks. J. Fluid Mech. 915, A102 (2021).

Bae, H. J. & Koumoutsakos, P. Scientific multi-agent reinforcement learning for wall-models of turbulent flows. Nat. Commun. 13, 1443 (2022).

Yang, X., Zafar, S., Wang, J.-X. & Xiao, H. Predictive large-eddy-simulation wall modeling via physics-informed neural networks. Phys. Rev. Fluids 4, 034602 (2019).

Raissi, M., Perdikaris, P. & Karniadakis, G. E. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 378, 686–707 (2019).

Wang, J.-X., Wu, J.-L. & Xiao, H. Physics-informed machine learning approach for reconstructing Reynolds stress modeling discrepancies based on DNS data. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2, 034603 (2017).

Davidson, L. Using machine learning for formulating new wall functions for Large Eddy Simulation: A second attempt, Div. of Fluid Dynamics, Mechanics and Maritime Sciences, Chalmers University of Technology (2022).

Xue, X., Biferale, L., Sbragaglia, M. & Toschi, F. A lattice Boltzmann study on Brownian diffusion and friction of a particle in a confined multicomponent fluid. J. Comput. Sci. 47, 101113 (2020).

Xue, X., Sbragaglia, M., Biferale, L. & Toschi, F. Effects of thermal fluctuations in the fragmentation of a nanoligament. Phys. Rev. E 98, 012802 (2018).

Xue, X., Biferale, L., Sbragaglia, M. & Toschi, F. A lattice Boltzmann study of particle settling in a fluctuating multicomponent fluid under confinement. Eur. Phys. J. E 44, 1–10 (2021).

Chiappini, D., Xue, X., Falcucci, G. and Sbragaglia, M. Ligament break-up simulation through pseudo-potential lattice Boltzmann method, in AIP Conference Proceedings, Vol. 1978 (AIP Publishing, 2018) p. 420003

Chiappini, D., Sbragaglia, M., Xue, X. & Falcucci, G. Hydrodynamic behavior of the pseudopotential lattice Boltzmann method for interfacial flows. Phys. Rev. E 99, 053305 (2019).

Hou, S., Sterling, J., Chen, S. and Doolen, G. A lattice Boltzmann subgrid model for high Reynolds number flows, Pattern formation and lattice gas automata, 151–166 (1995).

Toschi, F. & Bodenschatz, E. Lagrangian properties of particles in turbulence. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 41, 375–404 (2009).

Karlin, I. V., Ferrante, A. & Öttinger, H. C. Perfect entropy functions of the lattice Boltzmann method. EPL (Europhys. Lett.) 47, 182 (1999).

Lallemand, P. & Luo, L.-S. Theory of the lattice Boltzmann method: Dispersion, dissipation, isotropy, Galilean invariance, and stability. Phys. Rev. E 61, 6546 (2000).

Succi, S. The Lattice Boltzmann Equation for Fluid Dynamics and Beyond (Oxford University Press, 2001).

Krüger, T. et al. The lattice Boltzmann method. Springe. Int. Publ. 10, 978–3 (2017).

Lallemand, P., Luo, L.-s, Krafczyk, M. & Yong, W.-A. The lattice Boltzmann method for nearly incompressible flows. J. Comput. Phys. 431, 109713 (2021).

Malaspinas, O. & Sagaut, P. Wall model for large-eddy simulation based on the lattice Boltzmann method. J. Comput. Phys. 275, 25–40 (2014).

Latt, J., Chopard, B., Malaspinas, O., Deville, M. & Michler, A. Straight velocity boundaries in the lattice Boltzmann method. Phys. Rev. E 77, 056703 (2008).

Musker, A. Explicit expression for the smooth wall velocity distribution in a turbulent boundary layer. AIAA J. 17, 655–657 (1979).

Haussmann, M. et al. Large-eddy simulation coupled with wall models for turbulent channel flows at high Reynolds numbers with a lattice Boltzmann method: Application to Coriolis mass flowmeter. Comput. Math. Appl. 78, 3285–3302 (2019).

Maeyama, H., Imamura, T., Osaka, J. and Kurimoto, N. Unsteady turbulent flow simulation using lattice Boltzmann method with near-wall modeling, in AIAA Aviation 2020 Forum p. 2565 (2020).

Wilhelm, S., Jacob, J. & Sagaut, P. A new explicit algebraic wall model for LES of turbulent flows under adverse pressure gradient. Flow. Turbul. Combust. 106, 1–35 (2021).

Kuwata, Y. & Suga, K. Wall-modeled large eddy simulation of turbulent heat transfer by the lattice Boltzmann method. J. Comput. Phys. 433, 110186 (2021).

Xue, X., Yao, H.-D. & Davidson, L. Wall-modeled large-eddy simulation integrated with synthetic turbulence generator for multiple-relaxation-time lattice Boltzmann method. Phys. Fluids 35, 065115 (2023).

Shur, M. L., Spalart, P. R., Strelets, M. K. & Travin, A. K. A hybrid RANS-LES approach with delayed-DES and wall-modelled LES capabilities. Int. J. Heat. Fluid Flow. 29, 1638–1649 (2008).

Xue, X., Yao, H.-D. & Davidson, L. Synthetic turbulence generator for lattice Boltzmann method at the interface between rans and LES. Phys. Fluids 34, 055118 (2022).

Hoyas, S. & Jiménez, J. Scaling of the velocity fluctuations in turbulent channels up to Re τ = 2003. Phys. Fluids 18, 011702 (2006).

Lee, M. & Moser, R. D. Direct numerical simulation of turbulent channel flow up to Re τ ≈ 5200. J. Fluid Mech. 774, 395–415 (2015).

Pasquali, A., Geier, M. & Krafczyk, M. Near-wall treatment for the simulation of turbulent flow by the cumulant lattice Boltzmann method. Comput. Math. Appl. 79, 195–212 (2020).

d’Humieres, D. Multiple–relaxation–time lattice Boltzmann models in three dimensions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 360, 437–451 (2002).

Guo, Z., Zheng, C. & Shi, B. Discrete lattice effects on the forcing term in the lattice Boltzmann method. Phys. Rev. E 65, 046308 (2002).

Smagorinsky, J. General circulation experiments with the primitive equations: I. the basic experiment. Monthly Weather Rev. 91, 99–164 (1963).

Koda, Y. & Lien, F.-S. The lattice Boltzmann method implemented on the GPU to simulate the turbulent flow over a square cylinder confined in a channel. Flow., Turbul. Combust. 94, 495–512 (2015).

Abe, K., Kondoh, T. & Nagano, Y. A new turbulence model for predicting fluid flow and heat transfer in separating and reattaching flows-I. Flow field calculations. Int. J. heat. mass Transf. 37, 139–151 (1994).

Xue, X., Wang, S., Yao, H.-D., Davidson, L. and Coveney, P. V. Physics informed data-driven near-wall modelling for lattice Boltzmann simulation of high reynolds number turbulent flows (figures and data sets), https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13759611 (2024).

Xue, X., Wang, S., Yao, H.-D., Davidson, L. and Coveney, P. V. Physics informed data-driven near-wall modelling for lattice Boltzmann simulation of high reynolds number turbulent flows (code), https://github.com/UCL-CCS/PINN-WM-LBM (2024).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding support from European Commission CompBioMed Centre of Excellence (Grant No. 675451 and 823712). Support from the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council under the projects “UK Consortium on Mesoscale Engineering Sciences (UKCOMES)" (Grant No. EP/R029598/1) and “Software Environment for Actionable and VVUQ-evaluated Exascale Applications (SEAVEA)" (Grant No. EP/W007711/1) is gratefully acknowledged. We kindly acknowledge the funding from Chalmers Transport Area of Advance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.X., H.D.Y., and L.D. conceived the initial plan for this research. H.D.Y., L.D., and P.V.C. acquired funding and access to computing resources. X.X. and S.W. designed and conducted the numerical simulations. L.D. provided the IDDES data for training. X.X. and S.W. performed analysis. All authors discussed the findings. X.X., L.D., and P.V.C. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks PRATIKKUMAR Raje and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xue, X., Wang, S., Yao, HD. et al. Physics informed data-driven near-wall modelling for lattice Boltzmann simulation of high Reynolds number turbulent flows. Commun Phys 7, 338 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-024-01832-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-024-01832-1