Abstract

Force spectroscopy gives access to the underlying free energy landscape of protein folding. Proteins exhibit folding rates between microseconds and hours. To access slow folding rates, magnetic tweezers have shown to be a promising tool, yet it remained unclear if magnetic tweezers capture kinetics of ultra-fast folding proteins. Here, we study the folding mechanics and kinetics of λ6-85; a five-helix bundle protein with fast ~20 µs folding time in the thermal denaturation midpoint. We observed two-state folding of λ6-85 at ~ 6.2 pN and ~ 250 ms folding time in the mechanical midpoint. With optical tweezers, we found that λ6-85 folds at the mechanical midpoint with ~ 15 ms, 16-fold faster than in magnetic tweezers. To resolve the discrepancy between magnetic and optical tweezers, we developed a physics-based model taking into account the constant force condition of magnetic tweezers and the spacer mechanics. Using this model, we reach agreement between magnetic tweezers, optical tweezers and thermal denaturation experiments. In summary, we show that magnetic tweezers capture kinetics of ultrafast conformational changes, even at low forces. The model for extrapolation of the kinetics to force-free conditions provides opportunities of comparability for the growing community of magnetic tweezers force spectroscopy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Single-molecule force techniques allow to observe folding of individual proteins under tension1,2,3. To this end, an external force is applied at two points, typically at the N- and C-termini of a protein-of-interest, while the end-to-end distance is recorded over time. The multidimensional free energy landscape is thus projected on a single reaction coordinate, the end-to-end distance. Unfolded proteins are modeled as polypeptides using polymer physics and the elasticity of individual states is characterized during the folding process4,5,6. Early on, two prominent techniques were established to study protein mechanics, namely Atomic Force Microscopy and optical tweezers, allowing access to the underlying (un)folding energy landscape. Both techniques cover to a large extent the wide range of forces and timescales of protein folding7,8; yet, with limitations on the stability required to study slow kinetics and occasional rapid force-drift that make constant force measurements hard to implement. Such limitations can be readily resolved by high-resolution magnetic tweezers, which had been recently developed as tools for protein folding9,10,11,12,13,14.

Magnetic tweezers allow for ultra-stable measurements giving access to slow kinetics, although with a lower sampling rate than typically used for AFM or optical tweezers. AFM and optical tweezers experiments are performed under extension-constrained geometry, meaning the molecular extension is controlled15. Therefore, AFM and optical tweezers rely on active force feedback loops for near-constant force conditions. In contrast, magnetic tweezers act in a force-constrained geometry due to the separation between the nanometer-sized conformational changes in biomolecules and a magnetic field gradient on the millimeter scale producing constant forces of <1–100 pN16. Therefore, magnetic tweezers provide the intrinsic capability for passive force-clamp experiments. In combination with simultaneous tracking of a reference bead, magnetic tweezers reduce the effects of thermal drift, enabling long measurements of single proteins for hours, days or weeks as well as enhanced statistical sampling methods10,17,18. On the other hand, access to fast kinetics is limited to the sampling frequency of magnetic tweezers, which is on the order of ~1 kHz as compared to ~100 kHz in optical tweezers9,19. A lower sampling rate might appear as a limitation. Earlier studies have shown that micron-scaled probes together with polymeric linkers and force modulate kinetics exponentially to slow down folding rates20,21,22, an advantage already taken by optical tweezers and AFM to study ultrafast folding processes23,24,25,26,27. However, it remains unclear if transitions of a microsecond fast-folding protein can be observed using magnetic tweezers.

Here, we challenged the time-resolution limits of magnetic tweezers using λ6-85, a folding archetype for the study of ultrafast folding proteins and near-downhill folding under small barriers28,29. For that we used the pseudo wildtype λ6-85 (hereafter referred to as λwt) containing a Y22W mutation with ~20 µs kinetics in the thermal denaturation midpoint29,30 – at first glance too fast for magnetic tweezers. Yet, we observed two-state, reversible folding and unfolding transitions with surprisingly slow kinetics on the hundreds of milliseconds time scale. In earlier experiments using optical tweezers, we observed folding kinetics on the tens of millisecond time scale for λwt, while bulk thermal denaturation experiments suggested folding kinetics on the order of tens of microseconds. Such discrepancies raise challenges regarding data interpretation and comparability, which were described also in earlier studies31. Optical tweezers data and force-free data can be reconciled using established extrapolation models, which correct for probe and spacer contributions to the energy landscape. Such models were developed for extension-constrained geometries32,33 and, thus, cannot readily applied for force-constrained magnetics tweezers. Here, we derived an extrapolation model that provides comparability and close agreement between optical tweezers, magnetic tweezers and thermal denaturation bulk data.

Results and Discussion

The mechanical fingerprint of λwt

We used a home-built, ultra-stable, high-resolution magnetic tweezers instrument designed for protein folding force spectroscopy (Methods). The setup was built based on design principles developed and described earlier10,34. The instrument was calibrated by means of the well-studied properties of protein L, using a poly-protein construct with established force-extension characteristics to link magnets position with applied force (Methods). To study λwt unfolding and refolding mechanics, we sub-cloned λwt in an expression plasmid containing an N-terminal HaloTag (Methods), followed by λwt and two Spy0128 domains prior to the C-terminal AviTag (here after H-λwt-Sx2) (Fig. 1a). The HaloTag binds covalently to surface-anchored O4 ligands, the two Spy0128 pilin domains act as spacers and contain isopeptide bonds, which prevents them from unfolding at F < 1000 pN35. Each Spy0128 exhibits an end-to-end distance of 9 nm, as measured from protein structures determined by X-ray crystallography36.

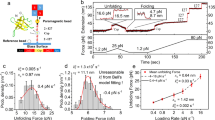

a Schematics of the recombinant protein construct in the magnetic tweezers setup. b Force protocol starting with a force ramp (c) to estimate the total length of the tether, followed by constant force measurements, allowing to determine equilibrium kinetics and states occupancies (d). Inset histograms were built from 200 s for each force and show two states, where the occupation was modulated by the application of different forces. c Zoom-in to the initial force ramp protocol with a tether length of ~35 nm. d Zoom-in to the extension over a time-lapse of 20 s for three different forces showing unfolding and refolding of λwt. Is shown in gray the raw extension data and in black the Savitzky-Golay filtered data with a 51 points window ( ~ 51 ms) as implemented in Igor Pro 8.04.

To study the mechanics of λwt, we first applied a force ramp to identify the fingerprint and force range of single λwt folding. We increased the pulling force from 1 pN to 20 pN in 10 seconds (loading rate: 1.9 pN s-1), followed by a slow drop of the force from 20 pN to 1 pN in 80 seconds (loading rate: -0.24 pN s-1) (Fig. 1b and c). A rapid increase of the force allows for a quick estimation of extensions, while a slow decrease of the force allows for a search of reversible transitions. During this force cycle, we observed an increase in the extension to ~35 nm, which is in good agreement with the expected ~38 nm from polymer models (Supplementary Note 3). During the slow decrease of pulling force, we observed distinct, repetitive steps in molecular extension within the range of 8 to 5 pN (Fig. 1c, inset), likely representing repetitive λwt refolding and unfolding events. For a further characterization, we performed constant force experiments between 5 and 8 pN in 0.15-0.3 pN steps. At a given force, we observed again hundreds of folding and unfolding events over hundreds of seconds. Increasing the force, inverted the populations from a predominantly folded state (low extension), to a predominantly unfolded state (high extension) (Fig. 1b, d). The minimal force-drift of the magnetic tweezers permitted long measurements of > 1 hour per molecule ( ~ 400 seconds at each force), enough to obtain well-sampled steady population distributions. From the population distributions, we extracted the change of extension upon unfolding \((\Delta {X}_{{\rm{fu}}}(F)\equiv {{X}_{{\rm{u}}}}-{X}_{{\rm{f}}})\) and compared this to the expected step size for λwt unfolding. Folded λwt has a crystallographic end-to-end distance of ~2.7 nm (PDB: 1LMB) and unfolded λwt is an 80 amino-acids long polypeptide with a contour length of 80 aa×0.365 nm/aa = 29.2 nm37. The expected contour length change is therefore \(\Delta {L}_{{{\rm{fu}}}}=29.2\,{{\rm{nm}}}-2.7\,{{\rm{nm}}}=26.5\,{{\rm{nm}}}\), which converts to a change in extension of ~10.4 nm at F = 6.7 pN (Supplementary Note 3), and is in agreement with the data. We therefore conclude that the repetitive steps represent λwt unfolding and refolding events. We measured in total 9 individual λwt tethers and obtained single traces for up to 36,000 s (10 h), containing thousands of transitions.

Equilibrium mechanical stability of λwt

To study the mechanical stability of λwt, we built extension histograms at different constant forces and fitted the folded and the unfolded extension peak with a double-Gaussian distribution (Fig. 2a). Subsequently, we measured from our population diagrams \(\Delta {X}_{{\rm{uf}}}({F}_{{\rm{m}}})\) for every tether, and fit a worm-like chain (WLC) polymer model with persistence length \(p=0.5\,{{\rm{nm}}}\)33. A mean contour length change of \(\langle \Delta {L}_{{{\rm{fu}}}}\rangle =27.3\pm 0.7\,{{\rm{nm}}}\) was extracted (Fig. 2b), in excellent agreement with the expected contour length change of \(26.5\,{{\rm{nm}}}\). The area underneath each Gaussian allowed us to calculate the force-dependent stationary probability of the protein to be in the folded or unfolded state, \({P}_{{{\rm{f}}}}\left(F\right)=\frac{{A}_{{{\rm{f}}}}}{{A}_{{{\rm{u}}}}+{A}_{{{\rm{f}}}}}\) and \({P}_{{{\rm{u}}}}\left(F\right)=\frac{{A}_{{{\rm{u}}}}}{{A}_{{{\rm{u}}}}+{A}_{{{\rm{f}}}}}\), respectively. For each tether, we plot \({P}_{{{\rm{f}}}}\left(F\right)\) and fit a sigmoidal distribution,

to obtain the midpoint force \({F}_{{{\rm{m}}}}\) and the characteristic force response \(\gamma\) (Fig. 2c). Overall, the different tethers were narrowly distributed and we calculated an average \(\langle {F}_{{{\rm{m}}}}\rangle =6.2\pm 0.2\,{{\rm{pN}}}\) (SEM; n = 9 independent tethers) and \(\langle \gamma \rangle =0.42\pm 0.02\,{{{k}}}_{{{\rm{B}}}}{{T\; {{\rm{nm}}}}}^{-1}\) (SEM; n = 9 independent tethers). At this force we expect \(\Delta {X}_{{{\rm{uf}}}}\left({F}_{{{\rm{m}}}}\right)=9.8\,{{\rm{nm}}}\) given \(\Delta {L}_{{{\rm{fu}}}}=26.5\,{{\rm{nm}}}\), again in excellent agreement with our measured values of \(\langle {F}_{m}\rangle\) and \(\langle \gamma \rangle\) given that \(\langle \Delta {X}_{{{\rm{uf}}}}\rangle ({F}_{{{\rm{m}}}})=\frac{{k}_{{\rm{B}}}{{T}}}{{{\rm{\gamma }}}}=9.8\pm 0.5\,{{\rm{nm}}}\)5.

a Extensions histogram of a tether at 6.4 pN (top) and its corresponding double-Gaussian fit (bottom). The red line corresponds to the sum of the Gaussian fit distributions; f, u and t designate the mean extension values for the folded, unfolded and transition state, respectively. b Contour length changes determined from the extension histograms at the mechanical midpoint (n = 9 tethers; ~ 3600 transitions) and estimations using a WLC polymer model. Box-and-whisker plot is drawn from the first to the third inner quartile, whiskers to extreme values, red line corresponds to the median, and red dot to the mean. c Occupancy of the folded state (\({P}_{{{\rm{f}}}}\)) as a function of force with \({P}_{{{\rm{f}}}}={A}_{{{\rm{f}}}}/({A}_{{{\rm{f}}}}+{A}_{{{\rm{u}}}})\). Nine independent measurements (gray) and their corresponding sigmoidal fit is shown. Black markers correspond to exemplary data in Fig. 1 and the red line the sigmoidal curve obtained from the mean values \(\langle {F}_{{\rm{m}}}\rangle =6.2\pm 0.2\,{{\rm{pN}}}\) and \(\left\langle \gamma \right\rangle =0.42\pm 0.02\,{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\;{{\rm{nm}}}^{-1}\). Measurement error corresponds to SEM with n = 9 independent tethers.

To gain initial coarse estimations of the distance between the transition state and the unfolded state, \(\Delta {X}_{{{\rm{tu}}}}\left(F\right)\), we used the intersection between both Gaussian fits. Assuming that both, the unfolded state and transition state are dominated by the polypeptide elasticity, we fit the transition state distance with a WLC polymer model and extract a contour length change \(\langle \Delta {L}_{{{\rm{tu}}}}\rangle =13.6\pm 0.5\,{{\rm{nm}}}\) (corresponding to \(\langle \Delta {X}_{{{\rm{tu}}}}({F}_{{{\rm{m}}}})\rangle =5.1\pm 0.2\,{{\rm{nm}}}\)), yielding a first approximation to describe the transition state of λwt.

Magnetic tweezers slow down the kinetics of λwt folding

To extract folding and unfolding rates between both interconverting states, we adapted a thresholding algorithm from single ion channel recordings38,39(Supplementary Note 4). Using this algorithm, we segmented our recorded time trajectories into folded and unfolded states (Fig. 3a) and plotted the logarithm of the dwell times (\({{\mathrm{ln}}}({\tau }_{{{\rm{f}}}/{{\rm{u}}}})\)). Rare kinetic traps appeared (e.g. between 313 and 370 s in Fig. 1b) presumably due to proline isomerization40. Such kinetic traps were easily distinguishable from the rest of the data (Supplementary Note 6). Neglecting traps which accounted for 5 out of ~3600 transitions, we observed a single peak at each force, which suggests a single exponential distribution of lifetimes and, by extension, a single dominant barrier between both states (Fig. 3b). We fitted the probability distribution of lifetimes with

to extract the mean lifetimes and transition rates at each experimentally assessed force41,42. Within the force range of 5–8 pN, we observed a linear-like dependence of the folding and unfolding rates in a semi-logarithmic plot (Fig. 3c). Fitting the force-dependent transition rates, we determined a transition rate of \(\langle {k}_{{{\rm{u}}}\to {{\rm{f}}}}^{{{\rm{MT}}}}({F}_{{{\rm{m}}}})\rangle =\langle {k}_{{{\rm{f}}}\to {{\rm{u}}}}^{{{\rm{MT}}}}({F}_{{{\rm{m}}}})\rangle =4.0\,\pm 0.2\,{{{\rm{s}}}}^{-1}\) (SEM; n = 9 independent tethers) at the midpoint force, surprisingly slow for the fast-folding protein λwt. Noteworthy, in our earlier study using optical tweezers (Methods)27,43, we found at the corresponding midpoint force \(({F}_{{\mbox{m}}}^{{\mbox{OT}}}=5.5\pm 0.1\,{\mbox{pN}})\), \(\langle {k}_{{{\rm{u}}}\to {{\rm{f}}}}^{{{\rm{OT}}}}({F}_{{{\rm{m}}}})\rangle =\langle {k}_{{{\rm{f}}}\to {{\rm{u}}}}^{{{\rm{OT}}}}({F}_{{{\rm{m}}}})\rangle =65\,\pm 10\,{{{\rm{s}}}}^{-1}\), nearly 16-fold faster despite both techniques using force to study λwt folding (Fig. 3d, Supplementary Note 5). Furthermore, with the frequently used Bell-Evans model44,45 for an extrapolation to force-free conditions,

we observed a 100-fold discrepancy between magnetic tweezers, optical tweezers and bulk thermal denaturation experiments with unfolding rates ranging from \({k}_{{{\rm{f}}}\to {{\rm{u}}}}^{{{\rm{MT}}}}(F=0)=0.02\pm 0.01\,{{\mbox{s}}}^{-1}\) to \({k}_{{{\rm{f}}}\to {{\rm{u}}}}^{{{\rm{OT}}}}(F=0)=1.9\pm 0.9\,{{{\rm{s}}}}^{-1}\) and \({k}_{{{\rm{f}}}\to {{\rm{u}}}}^{{{\rm{T}}}-{{\rm{Jump}}}}(T=297.15\,{{\rm{K}}}) \sim 2.4\,{{{\rm{s}}}}^{-1}\)29, respectively (Supplementary Table 1 in Supplementary Note 7). Folding rates differed even by four orders of magnitude from \({k}_{{{\rm{u}}}\to {{\rm{f}}}}^{{{\rm{MT}}}}(F=0)=\left(2.3\pm 1.6\right)\cdot {10}^{4}\,{{\mbox{s}}}^{-1}\) to \({k}_{{{\rm{u}}}\to {{\rm{f}}}}^{{{\rm{OT}}}}(F=0)=\left(1.8\pm 1.2\right)\cdot {10}^{7}\,{{{\rm{s}}}}^{-1}\) and \({k}_{{{\rm{u}}}\to {{\rm{f}}}}^{{{\rm{T}}}-{{\rm{Jump}}}}(T=297.15\,{{\rm{K}}}) \sim ,3.7\cdot {10}^{3}\,{{{\rm{s}}}}^{-1}\). Different models work well for local interpolation, but result in different outcomes in the zero-force extrapolated region46. Hence, to understand the reason for these discrepancies, we expanded the Bell-Evans model by considering the spacer and the probe energetics, as also discussed in earlier studies for AFM and OT20,21,33,47.

We segment unfolded and folded states extensions a and quantify their dwell times by assuming exponential kinetics in a natural logarithm of dwell times distribution b; n = 100–1000 dwell times for every force within a tether. c Exemplary tether with rates at different forces showing linear behavior within the measured forces. Error bars correspond to the 95% CI from Levenberg-Marquardt fitting (see Methods). d Folding rate at the mechanical midpoint for magnetic tweezers (\({k}_{{{\rm{u}}}\to {{\rm{f}}}}^{{{\rm{MT}}}}\left({F}_{{{\rm{m}}}}\right)=4.0\pm 0.2\,{{{\rm{s}}}}^{-1}\), SEM; n = 9) and optical tweezers (\({k}_{{{\rm{u}}}\to {{\rm{f}}}}^{{{\rm{OT}}}}\left({F}_{{{\rm{m}}}}\right)=65\pm 10\,{{{\rm{s}}}}^{-1}\), SEM n = 10)27. Error bars correspond to the SEM.

Zero-force extrapolation models in a magnetic tweezers instrument

As a first approach, we estimated the free energies between the folded and unfolded states from the work performed in the experiments, given that λwt folds and unfolds reversibly. At the midpoint force \({F}_{{{\rm{m}}}}\) and a measurement temperature of \(T=297.15\,{{\rm{K}}}\) (used here-after for all our estimations), we calculated the reversible work \({W}_{{{\rm{fu}}}}\left({F}_{{{\rm{m}}}}\right)={F}_{{{\rm{m}}}}\Delta {X}_{{{\rm{fu}}}}\left({F}_{{{\rm{m}}}}\right)=(14.8\pm 0.3)\,{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\). However, to estimate \(\Delta {G}_{{{\rm{fu}}}}\left(F=0\right)\) we have to subtract the stretching energy of the unfolded protein polypeptide chain48, which we estimated by analytical integration of the WLC model to be \(\Delta {G}_{{{\rm{stretch}}}}\left({F}_{{{\rm{m}}}}\right)\approx 6.6\,{k}_{{\rm{B}}}{T}\;\;\;(\Delta {L}_{{{\rm{fu}}}}=26.5\,{{\rm{nm}}},\;{p}=0.5\,{{\rm{nm}}})\) (Supplementary Note 3). Hence, following

we obtained \({\Delta G}_{{{\rm{fu}}}}^{{{\rm{MT}}}}\left(F=0\right)=8.2\pm 0.3\,{k}_{B}T\), which is slightly lower than earlier studies using optical tweezers27 (\({\Delta G}_{{{\rm{uf}}}}^{{{\rm{OT}}}}(F=0)=9.0\pm 0.1\,{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\)) and slightly higher than CD-spectroscopy chemical denaturation estimates (\({\Delta G}_{{{\rm{uf}}}}^{{{\rm{CD}}}}\left(\left[{{\rm{urea}}}\right]=0\right)=7.34\,{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\))29. Small \(\sim 1\,{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\) discrepancies in energy estimates can arise for instance from different parameters of the polymer model. If a higher persistence length for the unfolded protein of \(p=0.7\,{{\rm{nm}}}\) instead of \(p=0.5\,{{\rm{nm}}}\) is used, we estimate \(\Delta {G}_{{{\rm{stretch}}}}\left({F}_{{{\rm{m}}}}\right)\approx 7.6\,{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\;\;\;(\Delta {{{L}}}_{{{\rm{fu}}}}=26.5\,{{\rm{nm}}},\;{p}=0.7\,{{\rm{nm}}})\) and \({\Delta G}_{{{\rm{fu}}}}^{{{\rm{MT}}}}\left(F=0\right)=7.2\pm 0.3\,{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\), nearly perfectly matching the CD-spectroscopy data. These discrepancies are nevertheless very small, which showcase the benefits of including the energetic contribution of protein stretching (entropic forces) into extrapolations. We would like to point out caution when comparing force spectroscopy outcomes to data using other denaturation mechanisms (chemical or thermal denaturation), which likely show a more compact unfolded state49.

While we observed close agreement between magnetic tweezers, optical tweezers and bulk chemical denaturation in folding stabilities, the interconversion kinetics still show a difference of up to four orders of magnitude. To overcome this discrepancy, we expanded the Bell-Evans model by a force-dependent distance to the transition state for unfolding and folding reactions, \(\Delta {X}_{{{\rm{ft}}}}\left(F\right)\) and \(\Delta {X}_{{{\rm{tu}}}}\left(F\right)\), respectively. The unfolded and transition states can be described with the WLC model (i.e. \({X}_{{{\rm{u}}}/{{\rm{t}}}}={X}_{{{\rm{u}}}/{{\rm{t}}}}^{{{\rm{WLC}}}}(F,p,{L}_{{{\rm{u}}}/{{\rm{t}}}})\))50 while folded states with a Freely Jointed Chain (FJC) model11(i.e. \({X}_{{{\rm{f}}}}={X}_{{{\rm{f}}}}^{{{\rm{FJC}}}}({{\rm{F}}},{l}^{0})\)) (Supplementary Note 3). Using Kramers’ rate theory, the folding and unfolding rates follow15,32

It is important to always compare our fitting outcomes with the results obtained using Eq. 4 by means of the detailed balance condition5,

which we used as a control comparing extrapolations based on kinetics and extrapolations based on equilibrium probabilities and extensions. While Eqs. 5.1 and 5.2 improve the unfolding rate extrapolation, we found still discrepancies between magnetic tweezers and optical tweezers of more than one order of magnitude for \({k}_{{{\rm{f}}}\to {{\rm{u}}}}(F=0)\) and two orders of magnitude for \({k}_{{{\rm{u}}}\to {{\rm{f}}}}(F=0)\) (Fig. 4c and d, and Supplementary Table 1 in Supplementary Note 7). Upon closer inspection, we realized that the energetic terms of the spacers are not explicitly accounted for in the given Eq. 5.1 and Eq. 5.2, which in our experimental design, correspond to both Spy0128 domains as well as the Halo-Tag domain.

a For optical tweezers, the trap is described as a Hookean spring and the DNA spacer by means of an extensible WLC model (eWLC). b For magnetic tweezers, the probe is at constant force, linkers are folded proteins described by FJC models, and unfolded λwt is described by a WLC model. c and d show the folding and unfolding rates’ response to force, respectively, along with their fitting outcomes after zero-force extrapolations with the different models described in the main text. For the magnetic tweezers, rates of all n = 9 tethers in gray and exemplary data of a single tether in black are shown. Black trend-lines show the average of n = 9 individual fits. Optical tweezers data is shown in red, fits in light red. e Energy landscape parameters comparison between T-jump, OT and three models for MT data extrapolation. Error bars represent SEM (n = 9). Acronyms: WLC corresponds to Worm Like Chain; eWLC, elastic Worm Like Chain; FJC, Freely Jointed Chain.

Spacer and probe contributions to kinetics had been widely demonstrated in force spectroscopy 22,51,52,53. In analogy to AFM and OT models22,33, we decided to separate the energy barrier into probe, spacer and protein-free energy changes during the folding process. For optical tweezers, the folding and unfolding rates follow equations of the form

with the superscripts p and s to denote the protein and spacer, respectively. For optical tweezers (Fig. 4a), the model contains the energy contributions of the DNA-spacer (1826 bp) using an extensible WLC model (eWLC), the protein entropic forces \({{F}}_{{{\rm{WLC}}}}^{{{\rm{p}}}}\), and the potential energy gain of the probe \({\Delta E}_{{{\rm{ij}}}}^{{{\rm{probe}}}}=\frac{1}{2}{\alpha }^{{{\rm{probe}}}}{({X}_{{{\rm{j}}}}^{{{\rm{p}}}+{{\rm{s}}}})}^{2}-\frac{1}{2}{\alpha }^{{{\rm{probe}}}}{({X}_{{{\rm{i}}}}^{{{\rm{p}}}+{{\rm{s}}}})}^{2}\), with \({X}_{{{\rm{i}}}}^{{{\rm{p}}}+{{\rm{s}}}}={X}_{{{\rm{i}}}}^{{{\rm{s}}}}+{X}_{{{\rm{i}}}}^{{{\rm{p}}}}\) and \({\alpha }^{{{\rm{probe}}}}\) the stiffness of the optical tweezers. The sign of each energy contribution is given by the differences in extension of the individual components, which depend on the constantly changing forces of the extension-constrained optical tweezers tether (e.g. \({X}_{{{\rm{t}}}}^{{{\rm{s}}}}={X}^{{{\rm{s}}}}\left({F}_{{{\rm{t}}}}\right) > {{X}_{{{\rm{u}}}}^{{{\rm{s}}}}=X}^{{{\rm{s}}}}({F}_{{{\rm{u}}}})\)). Conversely, the magnetic tweezers is a force-constrained instrument (Fig. 4b)15. As a consequence, the potential energy gain of the magnetic tweezers probe cannot be described by a Hookean spring, but by a constant force field \((F\Delta {X}_{{{\rm{tu}}}}^{{{\rm{p}}}+{{\rm{s}}}})\). The spacer proteins in our magnetics tweezers experiments are very stiff compared to DNA handles and are thus better described using a FJC model, with each folded domain described as a rigid segment of length given by its crystallographic end-to-end distance (as in Supplementary Note 3). Taking this into account, we modified Eqs. 7.1 and 7.2 as follows,

taking care that the signs of the energy contributions match those in Eqs. 7.1 and 7.2. In a first approximation, we assume \({x}_{{{\rm{t}}}}^{{{\rm{s}}}}=0\), i.e. the spacer extension at the transition state is zero, yielding us an upper bound estimation of \({k}_{{{\rm{u}}}\to {{\rm{f}}}}^{{{\rm{MT}}}}(F=0)\). We then fit the folding and unfolding rate, independently, with varying \({x}_{{{\rm{t}}}}^{{{\rm{p}}}}(p,{L}_{{{\rm{t}}}})\) and the zero force rate \({k}_{{{\rm{i}}}\to {{\rm{j}}}}^{0}\) (Fig. 4c, d). We obtained \({k}_{{{\rm{u}}}\to {{\rm{f}}}}^{{{\rm{MT}}}}\left(F=0\right)=\left(2.9\pm 1.2\right)\cdot {10}^{4}\,{{\rm{s}}}^{-1}\) and \({{{k}}}_{{{\rm{f}}}\to {{\rm{u}}}}^{{{\rm{MT}}}}\left({{\rm{F}}}=0\right)=5.3\pm 2.5\,{{{\rm{s}}}}^{-1}\), both in good agreement with \({k}_{{{\rm{u}}}\to {{\rm{f}}}}^{{{\rm{OT}}}}\left(F=0\right)=\left(4.4\pm 3.7\right)\cdot {10}^{4}\,{\rm{s}}^{-1}\) and \({k}_{{{\rm{f}}} \to {{\rm{u}}}}^{{{\rm{OT}}}}\left(F=0\right)=4.9\pm 2.2\,{{\rm{s}}}^{-1}\) from our earlier optical tweezers experiments (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Table 1 in Supplementary Note 7). As a control, we verified that the fitting outcomes follow the detailed balance condition (Eq. 6) an that \(\Delta {X}_{{{\rm{fu}}}}^{{{\rm{p}}}}=\Delta {X}_{{{\rm{ft}}}}^{{{\rm{p}}}}+\Delta {X}_{{{\rm{tu}}}}^{{{\rm{p}}}}\) match our expectations. Note that by assuming a Kramers’ rate pre-factor of \({\tau }_{0}=1.5\,{{\rm{\mu }}}{{\rm{s}}}\) for λwt28, we estimate that the transition barrier discrepancies between the three independent methods – magnetic tweezers, optical tweezers and T-jump – are only 1–2.5 \({k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\). In particular, given the used molecular construct, we predict that \({k}_{{{\rm{f}}}\to {{\rm{u}}}}^{{{\rm{MT}}}}\left(F\right)\) follows a strong non-monotonic behavior (Fig. 4d), originating from the additional entropic barrier imposed by the spacer mechanics. We finally explored \({x}_{{{\rm{t}}}}^{{{\rm{s}}}}\ne 0\), assuming that both spacer and protein act as Hookean springs in series with the force balance condition \(F={\Delta {X}_{{{\rm{ut}}}}^{{{\rm{s}}}}\partial }_{F}{X}_{{{\rm{s}}}}=\) \(\Delta {X}_{{{\rm{ut}}}}^{{{\rm{p}}}}{\partial }_{F}{X}_{{{\rm{p}}}}\) during folding, and discuss the limitations in the Supplementary Note 8. To estimate the effects that other tethers might have on the entropic barrier, we used the case in which \({X}_{{{\rm{t}}}}^{{{\rm{s}}}} \, \ne \, 0\) for different \({X}_{{{\rm{t}}}}^{{{\rm{s}}}}\) values showing that long DNA spacers contribute less to the barrier (See Supplementary Note 9). In this way we evaluate the effects of further corrections to \({X}_{{{\rm{s}}}}\), accounting for unstructured amino acids that link proteins together obtaining a minor effect on the energetics (\(\sim 1\,{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\); see Supplementary Note 10).

What does a model-based approach tell us about the entropic barriers of the magnetic tweezers instrument? It is not uncommon that an instrument has an effect on transition rates of a single molecule. For instance, Langevin dynamics can be used to illustrate that the diffusion constant of the apparatus can slow down observed kinetics. Nevertheless, bead size effects on diffusion hardly solve the observed discrepancies alone. As modelled in20 and31, in the most extreme cases report a 100-fold change in apparatus diffusion constant, leads to ~5-fold reduced kinetics. For our system we estimate up to ~2-fold change in kinetics from beads diffusion (see Fig. 5a and Supplementary Note 11). In contrast, based on extrapolation models (Eqs. 8.1 and 8.2), we can estimate now spacer and device contributions to the energy barrier at the mechanical midpoint which has an exponential effect on kinetics (Figs. 5b, c). According to these fitting estimations assuming\(\,{X}_{{{\rm{t}}}}^{{{\rm{s}}}}\approx 0\) for magnetic tweezers, the entropic energy gain of the spacer during folding at the mechanical midpoint approximates to \(-6.1\,{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\), that of the protein \(4.6\,{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\), while the probe potential energy gain is \(-7.6\,{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\), resulting in a total sum of \(-9.1\,{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\). In contrast, for our optical tweezers geometry, we obtained values of \(-3.3\,{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\) for the DNA spacer (1826 bp), \(3.8\,{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\) for the protein and \(-5.7\,{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\) for the probe, for a total sum of \(-5.2\,{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\) at the mechanical midpoint. Spacer contributions become intuitive given the steep energy costs of stretching a stiff linker during protein folding, while instrument contributions involve the spring constant of the optical tweezers, and the slightly different mechanical midpoints that we observe in both techniques. In sum, the magnetic tweezers configuration increased the barrier at the mechanical midpoint by \({\Delta }_{{{\rm{MT}}}-{{\rm{OT}}}}\Delta {G}_{{{\rm{ft}}}}\left({F}_{{{\rm{m}}}}\right)\approx 3.9\,{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\) compared to the optical tweezers. Such an additional barrier slows down the transition rate from \({k}_{{{\rm{obs}}}}^{{{\rm{OT}}}}=64\,{{\rm{s}}}^{-1}\) to \({k}_{{{\rm{obs}}}}^{{{\rm{MT}}}}\approx 1.3\,{\rm{s}}^{-1}\), very close to the measured rates.

a To estimate the difference in kinetics between optical tweezers and magnetic tweezers, Langevin dynamics simulations revealed a ~ 2-fold change in kinetics given the different apparatus diffusion coefficients (see Supplementary Note 11). \({k}_{M}\) represents the molecular rate and \({k}_{{MA}}\) the observed rate using the same nomenclature as in20. b, c Entropic barrier contributions for magnetic and optical tweezers, respectively, of each mechanical element in the respective models (with \({x}_{t}^{s}=0\)) modulate the force response differently. For a better comparison, the sum of contributions (total, red) is offset by \({\ln}\left({{k}}_{{\mathrm{uf}}}\left({\mathrm{F}}=0\right)\right)=10\). Mechanical midpoint forces are \(({F}_{{\rm{m}}})\) of each instrument (grey dashed line) are slightly different with to 6.2 pN in MT and 5.5 pN in OT.

Conclusion

In this study we showed that magnetic tweezers are suitable to study the ultra-fast folding λwt. We obtained insights into the mechanical requirements to unfold λwt as well as its force-dependent kinetics. We developed a model to take into consideration the instrument contributions to the altered kinetics from zero force conditions and compared the effects of extension-constraints in a typical optical tweezers to force-constraints in a magnetic tweezers. A rigorous theoretical framework for the extrapolation of experimental data to zero force conditions is an important prerequisite to study protein folding or conformational kinetics using magnetic tweezers. We anticipate that this model will facilitate the interpretation and comparability of magnetic tweezers data to other force spectroscopy approaches. In the case of λ-repressor, we anticipate that the study of mutations on the folding kinetics and the underlying energy landscape, as well as the transition towards downhill folding will be enabled. It is important to note, that the polymer model-based approach presented here remains in good agreement with diffusion-based perspectives developed in the field of force-probe artifacts20. \(\Delta {X}_{{{\rm{ut}}}}\) and \(\Delta {X}_{{{\rm{ft}}}}\) from the polymer model perspective are related to the diffusion coefficients of λwt in its folded or unfolded state. Though, the here presented polymer model approach bears an intuitive link to the experimentally determined end-to-end distance. The improved extrapolation models have not only implications as correction factors in force spectroscopy experiments, but also play an important role in the context of multi-domain proteins, where force-dependent barriers and spacer-like structures might arise as key players in folding kinetics.

Methods

Protein expression and purification

Please find a detailed step-by-step description of our sub-cloning and purification protocols in our Supplementary Note 1. Two plasmids where kindly provided by the Fernandez lab (Columbia University) encoding for HaloTag-(Protein L)8 and HaloTag-(spy0128)2, both with N-terminal His6Tag and AviTag10,42 in a pFN18A inducible expression vector. Protein L: HaloTag-(Protein L)8, was overexpressed in E. coli BLR cells and purified by affinity chromatography using standard FPLC protocols using an ÄKTA pure purification system (GE Healthcare). Subsequent size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200 increase 10/300GL, Cytiva) increase the purity > 95%. In vitro biotinylation was achieved by the BirA500-RT kit (Avidity). Excess biotin was removed using a MW cut-off centrifugation (Vivaspin 6, Cytiva) and the samples were flash frozen, aliquoted and stored at -70°C. The storage buffer consists of 10 mM Hepes, 150 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol and pH 7.2. λwt: λwt was subcloned into the HaloTag-(spy0128)2 encoding backbone using BamHI and BglII restriction sites and verified by sequencing. The resulting HaloTag-λwt-(spy0128)2 was overexpressed in a E. coli BL21(DE3) strain. Subsequent purification and biotinylation was identical to the Protein L protocol.

Chambers and surface preparation for force spectroscopy measurements

Measurement chambers were assembled by two coverslips, connected by a Parafilm spacer. The top coverslip (22 mm×22 mm, 1.5 thickness) was hydrophobic (methoxy-silane), while the bottom coverslip (40 mm×24 mm, 1.5 thickness) carried a Halo-O4-ligand and reference beads (amino silane followed by functionalization) as described earlier10. A detailed protocol is provided in Supplementary Note 1.

Magnetic tweezers setup

We used a custom-built magnetic tweezers setup following the design of the Fernandez lab10. The instrument was built using a Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted microscope on top of an Accurion workstation for vibration isolation. It is equipped with a 100x S-Fluor NA1.3 oil immersion objective, a 20x Plan NA0.4 objective (both Nikon) and a collimated light source consisting of a Cool-LED pE100 white lamp with a HQ 525/40 M green filter (Thorlabs). For image acquisition, we used a XIMEA XiQ CMOS sensor camera (MQ013MG-ON, XIMEA). As magnets we used two lines of five neodymium grade N52 magnets (D33, K&U Magnets) stacked on top of each other. Their position was controlled with a Linear voice-coil (LFA-2010, Equipment solutions) that allows fast (0.7 m/s) and precise (150 nm resolution in a range of 10 mm) movements. The objective position was controlled using a C-focus piezo position system (Madcity labs) for position feedback. Instrumentation was controlled using a multifunction DAQ card (NI USB-6341, National Instruments) to control the piezo actuator and a PID correction system (responsible for positioning and constant loop feedback on the voice coil movement) kindly calibrated by the members of Fernandez lab. The software to control the microscope was developed in Visual Studio Pro 2017. We calibrated the magnetic tweezers instrument by means of the polymer properties of the reference protein L as described in Supplementary Note 2.

Single-molecule force spectroscopy measurements

8 µl M-270 streptavidin-coated paramagnetic beads (Diameter 2.7 µm; Dynabeads) were passivated overnight before performing experiments in 200 µl of PBS-BSA 1% or blocking buffer (Tris 20 mM, NaCl 150 mM, MgCl2 2 mM, BSA 1% and NaN3 0.001% titrated with HCl to pH 7.4). For λwt experiments, beads were washed three times with PBS-BSA 1% using magnets to remove them from the solution prior to overnight incubation on a rotator. The next day, prepared chambers were incubated for 30-60 min with the protein of interest (HaloTag-(Protein L)8 or HaloTag-λwt-(spy0128)2) at c = 10-25 nM diluted in PBS-BSA 1% at pH 7.4. To avoid oxidation of the proteins during magnetic tweezers experiments, we wash the chamber with 10 mM ascorbic acid in PBS-BSA 1% carefully titrated back to pH 7.4. Finally, 30 µl of the magnetic beads solution was introduced to the fluid cell, incubated ∼10 minutes at RT, and proceeded to the magnetic tweezers. Each experiment was preceded by x-y positioning of the magnets and calibration of their offset distance to the surface. For x-y positioning the field of view is centered at the gap between the two distal magnets. The 0.00 ± 0.01 mm magnets to surface offset distance was calibrated by using the voice-coil z-control to gently touch the surface of a reference bottom glass. The fluid cell was placed and a z-stack library and track in real-time z-position of the beads with a 100X objective was prepared. Reference beads position is used to correct for drift. The sampling rate ranges between 400-1200 Hz depending on the region-of-interest size (lateral distance between measurement bead and reference bead). Z-positions of both beads were determined in real-time and saved. After data acquisition data was analyzed using custom-written scripts in Igor Pro 8.04 (Wavemetrics, Portland, USA). For fitting a built-in Levenberg-Marquardt non-linear least squares algorithm was used. Fitting errors in the rates were determined within each independent tether, and via numerical Monte Carlo simulations to estimate the effect of time-limited measurements. When required, Gaussian error propagation was used as implemented numerically in http://www.julianibus.de/.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Analyzed data, i.e. rates and occupancies with their corresponding measurement errors, is provided as Supplementary Data 1. Raw data of this study is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Code availability

Pseudocode for data analysis is described in the Algorithm S1 in Supplementary Note 8. Igor Pro implemented scripts are available upon request.

References

Woodside, M. T. & Block, S. M. Reconstructing Folding Energy Landscapes by Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 43, 19–39 (2014).

Puchner, E. M. & Gaub, H. E. Force and function: probing proteins with AFM-based force spectroscopy. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 19, 605–614 (2009).

Žoldák, G. & Rief, M. Force as a single molecule probe of multidimensional protein energy landscapes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 23, 48–57 (2013).

Bustamante, C., Chemla, Y. R., Forde, N. R. & Izhaky, D. Mechanical Processes in Biochemistry. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73, 705–748 (2004).

Tinoco, I. Jr & Bustamante, C. The effect of force on thermodynamics and kinetics of single molecule reactions. Biophys. Chem. 101–102, 513–533 (2002).

Bustamante, C., Alexander, L., Maciuba, K. & Kaiser, C. M. Single-Molecule Studies of Protein Folding with Optical Tweezers. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 89, 443–470 (2020).

Neuman, K. C. & Nagy, A. Single-molecule force spectroscopy: optical tweezers, magnetic tweezers and atomic force microscopy. Nat. Methods 5, 491–505 (2008).

Naganathan, A. N. & Muñoz, V. Scaling of Folding Times with Protein Size. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 480–481 (2005).

Choi, H.-K., Kim, H. G., Shon, M. J. & Yoon, T.-Y. High-Resolution Single-Molecule Magnetic Tweezers. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 91, 33–59 (2022).

Popa, I. et al. A HaloTag Anchored Ruler for Week-Long Studies of Protein Dynamics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 10546–10553 (2016).

Chen, H. et al. Dynamics of Equilibrium Folding and Unfolding Transitions of Titin Immunoglobulin Domain under Constant Forces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 3540–3546 (2015).

Tapia-Rojo, R., Alonso-Caballero, Á. & Fernández, J. M. Talin folding as the tuning fork of cellular mechanotransduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117, 21346–21353 (2020).

Min, D., Jefferson, R. E., Bowie, J. U. & Yoon, T.-Y. Mapping the energy landscape for second-stage folding of a single membrane protein. Nat. Chem. Biol. 11, 981–987 (2015).

Löf, A. et al. Multiplexed protein force spectroscopy reveals equilibrium protein folding dynamics and the low-force response of von Willebrand factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 18798–18807 (2019).

Zhao, X., Zeng, X., Lu, C. & Yan, J. Studying the mechanical responses of proteins using magnetic tweezers. Nanotechnology 28, 414002 (2017).

De Vlaminck, I. & Dekker, C. Recent Advances in Magnetic Tweezers. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 41, 453–472 (2012).

Valle-Orero, J. et al. Mechanical Deformation Accelerates Protein Ageing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 9741–9746 (2017).

Tapia-Rojo, R. et al. Enhanced statistical sampling reveals microscopic complexity in the talin mechanosensor folding energy landscape. Nat. Phys. 19, 52–60 (2023).

Polimeno, P. et al. Optical tweezers and their applications. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 218, 131–150 (2018).

Cossio, P., Hummer, G. & Szabo, A. On artifacts in single-molecule force spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 14248–14253 (2015).

Neupane, K. & Woodside, M. T. Quantifying Instrumental Artifacts in Folding Kinetics Measured by Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 111, 283–286 (2016).

Schlierf, M. & Rief, M. Folding of Proteins under Mechanical Force. in Handbook of Single-Molecule Biophysics (eds. Hinterdorfer, P. & Oijen, A.) 397–406 (Springer US, New York, NY, 2009).

Schönfelder, J. et al. Reversible two-state folding of the ultrafast protein gpW under mechanical force. Commun. Chem. 1, 1–9 (2018).

Žoldák, G., Stigler, J., Pelz, B., Li, H. & Rief, M. Ultrafast folding kinetics and cooperativity of villin headpiece in single-molecule force spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 18156–18161 (2013).

Edwards, D. T., LeBlanc, M.-A. & Perkins, T. T. Modulation of a protein-folding landscape revealed by AFM-based force spectroscopy notwithstanding instrumental limitations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2015728118 (2021).

Reifs, A. et al. Compliant mechanical response of the ultrafast folding protein EnHD under force. Commun. Phys. 6, 7 (2023).

Mukhortava, A. Downhill folders in slow motion: Lambda repressor variants probed by optical tweezers. (Doctoral dissertation, TU Dresden, 2017).

Yang, W. Y. & Gruebele, M. Folding at the speed limit. Nature 423, 193–197 (2003).

Yang, W. Y. & Gruebele, M. Rate-temperature relationships in lambda-repressor fragment lambda 6-85 folding. Biochemistry 43, 13018–13025 (2004).

Huang, G. S. & Oas, T. G. Submillisecond folding of monomeric lambda repressor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 92, 6878–6882 (1995).

Sancho, D. D., Schönfelder, J., Best, R. B., Perez-Jimenez, R. & Muñoz, V. Instrumental Effects in the Dynamics of an Ultrafast Folding Protein under Mechanical Force. J. Phys. Chem. B 122, 11147–11154 (2018).

Dudko, O. K., Hummer, G. & Szabo, A. Theory, analysis, and interpretation of single-molecule force spectroscopy experiments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 15755–15760 (2008).

Schlierf, M., Berkemeier, F. & Rief, M. Direct observation of active protein folding using lock-in force spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 93, 3989–3998 (2007).

Tapia-Rojo, R., Mora, M. & Garcia-Manyes, S. Single-molecule magnetic tweezers to probe the equilibrium dynamics of individual proteins at physiologically relevant forces and timescales. Nat. Protoc. 19, 1779–1806 (2024).

Rivas-Pardo, J. A., Badilla, C. L., Tapia-Rojo, R., Alonso-Caballero, Á. & Fernández, J. M. Molecular strategy for blocking isopeptide bond formation in nascent pilin proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, 9222–9227 (2018).

Kang, H. J., Coulibaly, F., Clow, F., Proft, T. & Baker, E. N. Stabilizing Isopeptide Bonds Revealed in Gram-Positive Bacterial Pilus Structure. Science 318, 1625–1628 (2007).

Dietz, H. & Rief, M. Exploring the energy landscape of GFP by single-molecule mechanical experiments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101, 16192–16197 (2004).

Boukhet, M. et al. Probing driving forces in aerolysin and α-hemolysin biological nanopores: electrophoresis versus electroosmosis. Nanoscale 8, 18352–18359 (2016).

Oukhaled, A., Bacri, L., Pastoriza-Gallego, M., Betton, J.-M. & Pelta, J. Sensing Proteins through Nanopores: Fundamental to Applications. ACS Chem. Biol. 7, 1935–1949 (2012).

Rognoni, L., Möst, T., Žoldák, G. & Rief, M. Force-dependent isomerization kinetics of a highly conserved proline switch modulates the mechanosensing region of filamin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 5568–5573 (2014).

Sigworth, F. J. & Sine, S. M. Data transformations for improved display and fitting of single-channel dwell time histograms. Biophys. J. 52, 1047–1054 (1987).

Tapia-Rojo, R., Alonso-Caballero, A., Badilla, C. L. & Fernandez, J. M. Identical sequences, different behaviors: Protein diversity captured at the single-molecule level. Biophys. J. 123, 814–823 (2024).

Mukhortava, A. & Schlierf, M. Efficient Formation of Site-Specific Protein–DNA Hybrids Using Copper-Free Click Chemistry. Bioconjug. Chem. 27, 1559–1563 (2016).

Bell, G. I. Models for the Specific Adhesion of Cells to Cells. Science 200, 618–627 (1978).

Evans, E. & Ritchie, K. Dynamic strength of molecular adhesion bonds. Biophys. J. 72, 1541–1555 (1997).

Schlierf, M. & Rief, M. Single-Molecule Unfolding Force Distributions Reveal a Funnel-Shaped Energy Landscape. Biophys. J. 90, L33–L35 (2006).

Schlierf, M. & Rief, M. Surprising simplicity in the single-molecule folding mechanics of proteins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed Engl. 48, 820–822 (2009).

Liphardt, J., Onoa, B., Smith, S. B., Tinoco, I. & Bustamante, C. J. Reversible unfolding of single RNA molecules by mechanical force. Science 292, 733–737 (2001).

Stirnemann, G., Kang, S., Zhou, R. & Berne, B. J. How force unfolding differs from chemical denaturation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 3413–3418 (2014).

Rognoni, L., Stigler, J., Pelz, B., Ylänne, J. & Rief, M. Dynamic force sensing of filamin revealed in single-molecule experiments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 19679–19684 (2012).

Forns, N. et al. Improving Signal/Noise Resolution in Single-Molecule Experiments Using Molecular Constructs with Short Handles. Biophys. J. 100, 1765–1774 (2011).

Maitra, A. & Arya, G. Influence of pulling handles and device stiffness in single-molecule force spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 1836–1842 (2011).

Chang, J.-C., de Messieres, M. & La Porta, A. Effect of handle length and microsphere size on transition kinetics in single-molecule experiments. Phys. Rev. E 87, 012721 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Julio Fernandez and his group for kindly providing electronics and a construction guide as well as software for the magnetic tweezers setup. We also thank the Fernandez lab for the expression plasmid containing protein L8 and the HaloTag-Spy0128 plasmid. We thank the European Commission through Erasmus+ (to C.A.Q.C.), BMBF OptiZeD 03Z2EN511 (to M.S.), DFG SCHL1896/4-1 and SCHL1896/6-1 (to M.S.), and TU Dresden for funding. M.S. was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy- EXC-2068 - 390729961- Cluster of Excellence Physics of Life of TU Dresden. We thank Kristin Hunold, Dr. Anna Svirina and Dr. Yujun Zhang for molecular biology support and the members of B CUBE and especially the Schlierf group for their extensive feedback and discussions.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S. and C.A.Q.-C. conceptualized the study, C.A.Q.-C., A.M., M.A.B., A.H., K.-L.S. and M.S. devised and validated the methodology, C.A.Q.-C. and A.M. performed the investigation and formal analysis, C.A.Q.-C. and M.S. developed the theoretical model, A.H. provided resources, M.S. supervised the project, C.A.Q.-C. and M.S. wrote the original draft and all other authors reviewed and edited it. M.S. acquired funding for the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks Raul Perez-Jimenez and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Quintana-Cataño, C.A., Mukhortava, A., Boukhet, M.A. et al. Magnetic tweezers to capture the fast-folding λ6-85 in slow motion. Commun Phys 8, 13 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-024-01916-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-024-01916-y