Abstract

The coherence length ξ is the fundamental length scale of superconductors which governs the sizes of Cooper pairs, vortices, Andreev bound states, and more. In BCS theory, the coherence length is ξBCS = ℏvF/Δ, where vF is the Fermi velocity and Δ is the pairing gap. It is clear that increasing Δ will shorten ξBCS. In this work, we show that the quantum metric, which is the real part of the quantum geometric tensor, gives rise to an anomalous contribution to the coherence length. Specifically, \(\xi =\sqrt{{\xi }_{{{{\rm{BCS}}}}}^{2}+{\ell }_{{{{\rm{qm}}}}}^{2}}\) for a superconductor where ℓqm is the quantum metric contribution. In the flat-band limit, ξ does not vanish but is bound below by ℓqm. We demonstrate that under the uniform pairing condition, ℓqm is controlled by the quantum metric of minimal trace in the flat-band limit. Physically, the Cooper pair size of a superconductor cannot be squeezed down to a size smaller than ℓqm which is a fundamental length scale determined by the quantum geometry of the wave functions. Lastly, we compute the quantum metric contributions for the family of superconducting moiré graphene materials, demonstrating the significant role played by quantum metric effects in these narrow-band superconductors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bardeen–Cooper–Schriffer (BCS) theory1 of superconductivity stands as one of the most successful and influential theories in modern physics. It offers a mean-field, yet non-perturbative and microscopic framework for understanding superconductivity. It has been very successful in describing a large number of superconductors2,3,4. Deviations from the BCS theory are not unusual, which are often attributed to strong interaction effects5,6. Recently, the observations of superconductivity in twisted bilayer graphene7,8,9,10,11 and related graphene family12,13,14 hinted that a new theory is needed to describe superconductors with nearly flat bands. It was observed in a recent experiment11 that some important physical quantities deviate greatly from BCS predictions and the microscopic origins behind them are not yet clear.

For example, the BCS superconducting coherence length ξBCS is expressed as ℏvF/Δ, where vF is the Fermi velocity and Δ is the pairing gap. When the moiré band of twisted bilayer graphene is nearly flat with vF ≈ 103 m/s and Δ ≈ 0.2 meV, ξBCS is estimated to be around 3 nm which is more than one order of magnitude shorter than the values measured using upper critical field measurements11. Furthermore, the low Fermi velocity (or equivalently, large effective mass) should lead to a low superfluid stiffness. This results in an expected Berezinskii–Kosterlitz–Thouless transition temperature much lower than the transition temperature measured at optimal doping11. It had been pointed out by previous works that the quantum metric15,16 of the flat bands, which is the real part of the quantum geometric tensor, is essential in sustaining a supercurrent17,18. Apart from the investigations of superfluid weight19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34, the quantum geometry affects other physical quantities such as the intrinsic nonlinear transport35,36,37 and electron–phonon coupling38.

In recent work, by deriving the Ginzburg–Landau theory for an exactly flat band (with zero bandwidth)39, we pointed out that ξ is determined by the quantum metric of the Bloch wave function which is independent of the interaction strength. This contradicts the intuition that stronger attractive interactions between electrons generally result in a smaller Cooper pair size and shorter coherence length, as described by the BCS theory.

Explicitly, considering the Bloch states of a band represented by \(\left\vert u({{{\boldsymbol{k}}}})\right\rangle\), the quantum geometric tensor \({\mathfrak{G}}\)40,41 is

Here, a and b represent the momentum directions. The quantum geometric tensor can be decomposed into real and imaginary parts as \({\mathfrak{G}}={{{\mathcal{G}}}}-i{{{\mathcal{F}}}}/2\), where the real part \({{{\mathcal{G}}}}\) is the quantum metric and the imaginary part \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}\) is the Berry curvature. Berry curvature arises from the phase difference between adjacent Bloch states and characterizes the band topology of materials42,43,44,45,46,47. The study of the physical consequences of the Berry curvature has been one of the central topics in modern physics. On the other hand, the effect of quantum metric, which measures the distance between two quantum states48, is much less studied. It was pointed out that the quantum metric provides the size (or the so-called quadratic spread) ℓqm of the optimally localized Wannier state of a band49, where \({\ell }_{{{{\rm{qm}}}}}=\root 4 \of {\det \overline{{{{\mathcal{G}}}}}}\). Here, \(\overline{{{{\mathcal{G}}}}}\), defined in Eq. (11), is the weighted average of the quantum metric of the Bloch states within a band. The mathematical definition of ℓqm, which we call the quantum metric length, measures the minimal spread of the Wannier functions, is schematically illustrated in Fig. 1. However, the impact of the quantum metric length ℓqm on physical quantities was not clear. Until very recently, the Ginzburg–Landau theory39 shown that at zero temperature, ξ = ℓqm for an exactly flat band, which is independent of the interaction strength.

In realistic materials such as twisted bilayer graphene and related moiré flat-band superconductors, the bands are nearly flat, but the dispersion is still finite. One fundamental question arises: What is the interplay between the quantum metric effect and the finite dispersion of the band? In this work, we demonstrate that

In other words, there is an anomalous quantum metric contribution to the superconducting coherence length (recall that ξBCS = ℏvF/Δ). In the flat-band limit with vanishing vF, the quantum metric effect can be significant and even dominant. We show that this is indeed the case for several moiré superconductors with nearly flat bands11,12,13,14. Our result gives a possible explanation for why the observed superconducting coherence length in the recent experiment11 is much larger than expected. It is worth noting that the coherence length is lattice-geometry independent while the quantum metric is lattice-geometry dependent31,50. To resolve the discrepancy, we apply the uniform pairing condition when evaluating the pair correlators and then demonstrate that ℓqm is related to the quantum metric of the minimal trace31. We delineate the physical picture that, in the presence of the quantum metric, increasing the attractive interaction strength between electrons can only reduce the BCS part of the coherence length and squeeze the Cooper pair size down to the quantum metric length ℓqm, but not further, as demonstrated in Fig. 2.

a For a conventional superconductor with a dispersive band (as illustrated by the insert) without quantum metric, the coherence length ξ = ℏvF/Δ decreases as Δ (Δ is the superconducting pairing gap) increases and ξ is not bounded from below. b In the presence of quantum metric, the superconducting coherence length ξ has a lower bound of ℓqm. For a superconductor with a narrow band (as illustrated in the insert), the conventional contribution can be suppressed as Δ increases.

Additionally, for a topological flat band with nontrivial (spin) Chern number, \(\xi \ge a\sqrt{| C| /4\pi }\), where a is the lattice constant. At the end of this work, we show that the quantum metric length ℓqm is important for the superconducting moiré graphene family. As the new length scale ℓqm defined by the quantum metric is a fundamental property of the band structure and its importance should be manifested beyond superconducting phenomena, we expect that ℓqm also plays a crucial role in other interaction-driven ordered states (such as the magnetic or density-wave states33,51) in flat-band systems.

Results

Quantum metric and coherence length

We investigate the interplay between quantum metric and band dispersion in superconductors where superconductivity appears within an isolated narrow band. To begin with, we describe our formalism from a multi-orbital Hamiltonian with two components: the non-interacting part H0 and the attractive interacting part Hint, which read

where \({h}_{ij,\alpha \beta }^{\sigma }\) is the hopping integral and U denotes the on-site attractive interaction strength. aiασ annihilates a fermion with spin σ in the orbital α at the site i (we may call aiασ orbital fermions). Considering an isolated band near the Fermi energy separated from other bands with a large band gap, we can have an effective one-band description. For s-wave superconducting phase, it is common to introduce orbital-dependent order parameters Δα = −U〈aiα↓aiα↑〉. The mean-field ground state has been extensively investigated, particularly with regard to the superfluid weight determined by the quantum metric17. It is possible to project the orbital fermion aiασ onto the fermion cσ of the isolated band, which is referred as the band fermion. In particular, we employ the following projection scheme

where we explicitly keep the orbital positions {δα} within a unit cell. The Bloch state uασ(k) of the isolated band with energy ϵσ(k) satisfies the time-reversal symmetry \({u}_{\alpha }({{{\boldsymbol{k}}}})\equiv {u}_{\alpha \uparrow }({{{\boldsymbol{k}}}})={u}_{\alpha \downarrow }^{* }(-{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}})\). The projection in Eq. (5) yields an effective one-band mean-field Hamiltonian Hmf,

with Δ = 1/N∑αkΔα∣uα(k)∣2. The projected mean-field Hamiltonian Hmf is independent of the choice of orbital positions {δα}. To facilitate the theoretical analysis, we can adopt the uniform pairing condition and the minimal quantum metric31. The former assumes that the pairing potentials are the same for different orbitals, and the latter is specific to orbital positions corresponding to the minimal trace of quantum metric. Then we can define the Cooper pair operator \(\hat{\Delta }({{{\boldsymbol{q}}}})=\frac{1}{N}{\sum }_{i\alpha }{e}^{-i{{{\boldsymbol{q}}}}\cdot ({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{i}+{{{{\mathbf{\delta }}}}}_{\alpha })}{a}_{i\alpha \downarrow }{a}_{i\alpha \uparrow }\) which is formulated after projection as

Here the form factor \({{\Lambda }}({{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}+{{{\boldsymbol{q}}}},{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}})={\sum }_{\alpha }{u}_{\alpha }^{* }({{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}+{{{\boldsymbol{q}}}}){u}_{\alpha }({{{\boldsymbol{k}}}})\) appears as the overlap between two Bloch states. Then we can evaluate the pairing correlator \({{{\mathcal{C}}}}({{{\boldsymbol{r}}}})={\sum }_{{{{\boldsymbol{q}}}}}{e}^{-i{{{\boldsymbol{q}}}}\cdot {{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}\langle \hat{\Delta }({{{\boldsymbol{q}}}}){\hat{\Delta }}^{{{\dagger}} }({{{\boldsymbol{q}}}})\rangle\) to deduce the coherence length. The pairing correlator \({{{\mathcal{C}}}}({{{\boldsymbol{r}}}})\) is expected to decay exponentially as a function of ∣r∣ at zero temperature for an isotropic system. In other words, \({{{\mathcal{C}}}}({{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}) \sim {e}^{-| {{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}| /\xi }\) and the decay length ξ is the superconducting coherence length52. As shown in Supplementary Note 2, \({{{\mathcal{C}}}}({{{\boldsymbol{r}}}})\equiv {\sum }_{{{{\boldsymbol{q}}}}}{e}^{-i{{{\boldsymbol{q}}}}\cdot {{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}{{{\mathcal{M}}}}({{{\boldsymbol{q}}}})\), where

Here, G0(iωn, k) is the normal Gor’kov’s Green function of the band fermions cσ and ωn = (2n + 1)πT is the Matsubara frequency, as defined in “Methods” section. Then we can extract the coherence length by \({\xi }^{2}=-\frac{1}{2{{{\mathcal{M}}}}(0)}{\left.\frac{{d}^{2}{{{\mathcal{M}}}}({{{\boldsymbol{q}}}})}{d{q}^{2}}\right\vert }_{q = 0}\) with q = ∣q∣ at zero temperature. It is essential to emphasize that the validity of the expression in Eq. (8) hinges on the uniform pairing condition, specifically in relation to the Bloch states of the minimal quantum metric31. Without these conditions, the coherence length calculated using Eq. (8) will be overestimated, and additional details can be found in Supplementary Note 2. To see how the quantum metric affects the coherence length ξ, the form factor Λ enters \({{{\mathcal{M}}}}({{{\boldsymbol{q}}}})\) such that

The matrix \({{{{\mathcal{G}}}}}_{ab}\) is the quantum metric of Bloch states, namely the real part of quantum geometric tensor \({\mathfrak{G}}\) in Eq. (1),

By theoretically evaluating the pairing correlator, we can obtain the coherence length in Eq. (2) as \(\xi =\sqrt{{\xi }_{{{{\rm{BCS}}}}}^{2}+{\ell }_{{{{\rm{qm}}}}}^{2}}\). In fact, the structure of the coherence length in Eq. (2) is general and works regardless of the uniform pairing condition and the minimal quantum metric. The anomalous coherence length is \({\ell }_{{{{\rm{qm}}}}}= \root 4 \of {\det {\overline{{{{\mathcal{G}}}}}}_{ab}}\), where \({\overline{{{{\mathcal{G}}}}}}_{ab}\) is the weighted average of the quantum metric of the band, which is defined by

where ε(k) is the dispersion of the Bogoliubov quasiparticle. In the limit of a flat dispersion ε(k), the quantum metric length ℓqm is reduced to the length scale of the minimal quantum metric. The above discussions on the coherence length in Eq. (2) can be easily generalized to an anisotropic system with a non-circular Fermi surface where the quantum metric length becomes spatially dependent due to finite off-diagonal elements in the quantum metric.

To understand the physical consequence of the anomalous coherence length, we note that for a conventional superconductor, ξ = ξBCS decreases as the interaction strength (or equivalently Δ) increases, as schematically shown in Fig. 2a. However, in the presence of the quantum metric, ξ decreases as Δ increases, but approaches the quantum metric length ℓqm (see Fig. 2b). In the flat-band limit, the coherence length (at zero temperature) is independent of the interaction strength and given by ℓqm. In the presence of finite quantum metric, interactions cannot squeeze the Cooper pairs to a size smaller than ℓqm.

Topologically trivial flat-band model

To support the analytical results mentioned above, we employ the mean-field theory on a microscopic model, which features exactly flat bands without dispersion33,53. The normal state Hamiltonian hs(k) for electrons with spin index s reads

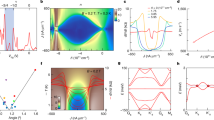

Here, \({\alpha }_{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}}=\chi [\cos ({k}_{x}a)+\cos ({k}_{y}a)]\) and λi are the Pauli matrices in orbital basis. s = ±1 denotes the spins ↑ and ↓. The hs(k) has a pair of perfectly flat bands at energies ϵk = ±t which are depicted in Fig. 3a (solid lines) and the corresponding wave functions are \(\left\vert {u}_{\pm }\right\rangle =1/\sqrt{2}{(\pm 1,is{e}^{is{\alpha }_{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}}})}^{T}\) for the upper band (+) and the lower band (−). The flat band is topologically trivial with the Berry curvature vanishing over the whole Brillouin zone. We can tune the quantum metric by altering the parameter χ in αk. It is straightforward to obtain the quantum metric for + band with components \({{{{\mathcal{G}}}}}_{ab}({{{\boldsymbol{k}}}})={\chi }^{2}{a}^{2}\sin ({k}_{a})\sin ({k}_{b})/4\), which is the minimal quantum metric since the orbitals are located at high-symmetry positions. The averaged quantum metric defined by Eq. (11) is given by \({\overline{{{{\mathcal{G}}}}}}_{ab}={\delta }_{ab}{\chi }^{2}/8\) which is related to the quantum metric length \({\ell }_{{{{\rm{qm}}}}}=\sqrt{2}\chi /4\). In Fig. 3b, we plot the distribution of \({{{\rm{Tr}}}}[{{{\mathcal{G}}}}({{{\boldsymbol{k}}}})]\) that respects the C4 symmetry and that \({{{\rm{Tr}}}}[{{{\mathcal{G}}}}({{{\boldsymbol{k}}}})]\) reaches its maximum at M/2. Since we are interested in a superconducting phase, we do not include other possible ground state ansatz. In the Nambu basis \({\Psi }_{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}}={({a}_{A,{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}\uparrow },{a}_{B,{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}\uparrow },{a}_{A,-{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}\downarrow }^{{{\dagger}} },{a}_{B,-{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}\downarrow }^{{{\dagger}} })^T}\) with an attractive interaction as Eq. (4), we have the mean-field Hamiltonian Hmf

Here, \(\hat{\Delta }={{{\rm{diag}}}}[{\Delta }_{A},{\Delta }_{B}]\) is the mean-field pairing order parameters. The Fermi energy μ is chosen such that the + band is half-filled. The solutions of the order parameters yield ΔA = ΔB = U/4, which satisfy the uniform pairing condition.

a The energy spectrum of the flat-band model in ref. 33. The solid (dashed) lines denote t2 = 0 and t2 = 0.02t, respectively. t2 denotes the nearest hopping which makes the band dispersive. b The profiles of the quantum metric \({{{\rm{Tr}}}}[{{{\mathcal{G}}}}]\) of the conduction band in the first Brillouin zone. The color bar denotes the magnitude of \({{{\rm{Tr}}}}[{{{\mathcal{G}}}}]\). c The calculated coherence length ξ for χ = 5 as a function of the attractive interaction U/t. The red, purple, and blue denote the cases of t2 = 0, t2 = 0.01t and t2 = 0.02t, respectively. The theoretical bound ℓqm is indicated by a dashed green line which coincides with the red one. d The quantum metric dependence of ξ as the parameter χ varies when U = 0.4t. The dashed light blue line marks the length scale ℓqm. All calculations are conducted at kBT = 0.001t and at half-filling μ = t.

Due to the absence of band dispersion, the coherence length \(\xi =\sqrt{2}\chi /4\) depends solely on the quantum metric. This is illustrated in Fig. 3d, where the numerical results [Eq. (8)] of pair correlation functions align with ℓqm. To incorporate the finite band dispersion, one can introduce an additional nearest-hopping term \(\delta h=-2{t}_{2}[\cos ({k}_{x}a)+\cos ({k}_{y}a)]{\lambda }_{0}\) to hs(k), where λ0 is the 2 × 2 identity matrix. This term gives rise to a band dispersion as well as the conventional contribution ξBCS to the total coherence length ξ. In Fig. 3c, the total coherence length gradually decreases for t2 = 0.01t, 0.02t when the attractive interaction strength U increases. In particular, ξ approaches ℓqm in the flat-band limit due to the suppression of ξBCS, as expected from Eq. (2).

Topological bound of the coherence length

In the previous subsection, we have demonstrated how the quantum metric gives a lower bound for the superconducting coherence length. We now consider a system which possesses topological flat bands. As pointed out previously49,54, the quantum metric has a lower bound which is proportional to the Chern number. Therefore, we expect that there is a finite quantum metric length which serves as the lower bound of the superconducting coherence length for a superconductor with nontrivial spin Chern numbers.

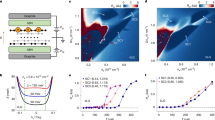

Specifically, the quantum geometric tensor is a positive semidefinite matrix, and in two spatial dimensions, we have the inequality \(\sqrt{\det {{{\mathcal{G}}}}({{{\boldsymbol{k}}}})}\ge | {{{{\mathcal{F}}}}}_{xy}({{{\boldsymbol{k}}}})| /2\), which implies that a topological band must necessarily possess a finite quantum metric. According to Eq. (2), this indicates that there is a lower bound on the coherence length ξ which is determined by the topology of the band such that

where C denotes the (spin) Chern number of a band with a lattice constant a. For demonstration, we consider a two-orbital square lattice with short- and long-range hoppings (Fig. 4a) with a finite spin Chern number55,56,57. Under the basis \({a}_{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}\sigma }={({a}_{A{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}\sigma },{a}_{B{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}\sigma })}^{T}\), the non-interacting Hamiltonian is \({H}_{0}={\sum }_{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}},\sigma }{a}_{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}\sigma }^{{{\dagger}} }{H}_{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}}{a}_{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}\sigma }\), where Hk = ∑ihi(k)λi. Here \({h}_{0}({{{\boldsymbol{k}}}})= (\sqrt{2}-1) \cos (2{k}_{x}a)\cos (2{k}_{y}a)/2\), \({h}_{x}({{{\boldsymbol{k}}}})=-\sqrt{2}[\cos ({k}_{x}a)+ \cos ({k}_{y}a)]/2\), \({h}_{y}({{{\boldsymbol{k}}}})= \sqrt{2}[\cos ({k}_{x}a) -\cos ({k}_{y}a)]/2\), and \({h}_{z}({{{\boldsymbol{k}}}})=-\sqrt{2}\sin ({k}_{x}a)\sin ({k}_{y}a)\). The λi are the Pauli matrices on the orbital basis. Importantly, the lowest band is nearly flat with a spin Chern number C = 2 (see Fig. 4b). The bandwidth is ~1% of the total band gap.

a A two-orbital square lattice with short- and long-range hoppings, b the electronic band structure, c the quantum metric distribution of the lower flat band, and d coherence length ξv.s. pairing gap Δ. In (a), the inter-orbital nearest hopping, intra-orbital next-nearest-neighbor and fifth-nearest-neighbor hoppings are labeled. In (b), the lower band (purple) has nearly zero bandwidth with the Chern number C = 2. In (d), the coherence length is extracted from the pair correlation function and it is bounded by a Chern number, which is guided by the dashed green line.

In Fig. 4c, we depict the distribution of \({{{\rm{Tr}}}}[{{{\mathcal{G}}}}({{{\boldsymbol{k}}}})]\), which exhibits C4 symmetry and has a large quantum metric at X/2 and points connected by symmetry. To demonstrate the effect of the nontrivial Chern number, in the mean-field calculations, we assume the flat band is half-filled for simplicity. The uniform pairing condition is also satisfied as ΔA = ΔB = Δ. Furthermore, we have calculated the Cooper pair correlation functions and extracted the coherence length from Eq. (8), which exhibits a decreasing trend as the band pairing potential Δ increases, as shown in Fig. 4d. Especially, in the limit of large Δ, the coherence length ξ converges to ~\(\root 4 \of {\det \overline{{{{\mathcal{G}}}}}}\) which is larger than \(\sqrt{| C| /4\pi }a\) as predicted by Eq. (14). This result clearly demonstrates how the superconducting coherence length is related to the quantum geometry (both the quantum metric and the topology) of the relevant band.

Application to Moiré materials

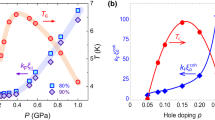

The graphene-based moiré systems provide versatile platforms to explore the exotic phenomena related to the flat bands58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67. In the superconducting graphene-based moiré family14, the quantum metric effect is indeed very crucial. Particularly, the quantum metric plays a significant role in determining the coherence length in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene (MATBG) with twisted angle θ ≈ 1.08°. To provide a qualitative estimation of the impact of the quantum metric, we employ the Bistritzer–MacDonald model to elucidate the significance of the quantum metric in the context of graphene-based moiré materials68. We also assume the presence of an s-wave superconducting phase. As shown in Fig. 5, the quantum metric length ℓqm = 1.2LM ≈ 13 nm. Here, LM ≈ a0/θ represents the moiré lattice constant. By employing the self-consistent mean-field study (in Supplementary Note 4), we calculate the total coherence length using Eq. (8) to take into account the band dispersion. Using the interaction strength U = 0.6 meV, which gives Tc ≈ 1.7 K, we obtain a conventional contribution of ~3 nm and ℓqm ~ 13 nm at θ = 1.08°. Therefore, the total superconducting coherence length given by Eq. (2), is indeed dominated by the quantum metric contribution.

For both MATBG and MATTG, the quantum metric is plotted for the highest valence band, and it exhibits divergence near the K points. In TDBG, an electric field potential of V = 40 meV is applied, leading to flat bands near charge neutrality with Chern number C = ±2. The quantum metric is plotted for the lowest conduction band. In evaluating ℓqm, we ignore the band dispersion.

A large family of moiré systems exhibit superconductivity, such as magic-angle twisted trilayer graphene (MATTG)13 and twisted double-bilayer graphene (TDBG)12. Similar to MATBG, the quantum metric effects cannot be neglected, as shown in Fig. 5. For MATTG, ℓqm = 1.2LM, and for TDBG, ℓqm = 0.5LM. The calculations of ℓqm in Fig. 5 are made by averaging the quantum metric over the moiré Brillouin zone without considering the quasiparticle energy in Eq. (11). Notably, the flat band in TDBG carries a non-zero valley Chern number C = 2, leading to a topology-bound coherence length, as discussed previously. We focus on the quantum metric within a single band, while the generalization to multiple nearly degenerate flat bands consists of replacing the one-band quantum metric with the non-abelian quantum metric69,70. The quantum metric length calculated for the moiré systems is a qualitative estimation because of the limitations of the continuum model and the simple s-wave pairing assumption. It will be an open question of the role that quantum metric plays in unconventional superconductivity for moiré systems.

Conclusion

In this work, we highlight that an intrinsic length scale, ℓqm, derived from the quantum metric, gives rise to an anomalous contribution of the coherence length in superconductors. Particularly in the case of flat bands, ℓqm plays a dominant role in determining the length scale of physical quantities, such as the superconducting coherence length. This length scale is likely also related to the size of vortices, Andreev bound states etc. We propose that our theory may also be applicable to quantum ordered phase in flat-band systems, since ℓqm is derived from the quantum geometry of the band and is independent of the interaction-driven order parameter. Furthermore, it would also be interesting to explore potential extensions of ℓqm to the physical properties of other ordered states (such as ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic states) with flat bands and quantum metric.

Methods

Mean-field theory and Gor’kov Green function. For a mean-field study, we can decouple the interaction term Hint in Eq. (4) with pairing order parameters \({\Delta }_{\alpha }=-U\langle {\hat{a}}_{i\alpha \downarrow }{\hat{a}}_{i\alpha \uparrow }\rangle\) to yield a mean-field Hamiltonian Hmf

where the Ψk is the spinor with components \({({\Psi }_{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}})}_{\alpha \uparrow }={a}_{\alpha \uparrow }({{{\boldsymbol{k}}}})\) and \({({\Psi }_{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}})}_{\alpha \downarrow }={a}_{\alpha \downarrow }^{{{\dagger}} }(-{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}})\). Here aασ is a Fermion operator on the orbital basis and τx,y,z are the Pauli matrices. The \(\hat{h}\) is the matrix with elements \({(\hat{h})}_{\alpha \beta }={h}_{\alpha \beta }({{{\boldsymbol{k}}}})-\mu {\delta }_{\alpha \beta }\) and the pairing matrix \(\hat{\Delta }\) has elements \({(\hat{\Delta })}_{\alpha \beta }={\Delta }_{\alpha }{\delta }_{\alpha \beta }\). Within the mean-field Hamiltonian, we can define the Green function \({\hat{G}}_{\alpha {\alpha }^{{\prime} },\sigma {\sigma }^{{\prime} }}(i{\omega }_{n},{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}})=\langle {({\psi }_{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}})}_{\alpha \sigma }(i{\omega }_{n}){({\psi }_{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}}^{{{\dagger}} })}_{{\alpha }^{{\prime} }{\sigma }^{{\prime} }}(i{\omega }_{n})\rangle\) with

where ωn = (2n + 1)πkBT is the Matsubara frequency. Then one may evaluate the pairing correlation function \({{{\mathcal{C}}}}({{{\boldsymbol{r}}}},{{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}^{{\prime} })\) with the Green function for a multicomponent fermion aασ. For an s-wave superconductor, we expect an exponential decay behavior in \({{{\mathcal{C}}}}({{{\boldsymbol{r}}}},{{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}^{{\prime} })\) as a function of \(| {{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}-{{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}^{{\prime} }|\).

On the other hand, we apply a mean-field theory to the effective two-band model after the projection. For a superconducting phase, we can introduce an s-wave pairing order parameter \(\Delta =-\frac{U}{N}{\sum }_{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}}\langle {c}_{\downarrow }(-{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}){c}_{\uparrow }({{{\boldsymbol{k}}}})\rangle ,\) and set Δ to be real via fixing the gauge. Here cσ is a Fermion operator on the flat band. Then we can have a mean field Hamiltonian

where \({\psi }_{{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}}={[\begin{array}{c}{c}_{\uparrow }({{{\boldsymbol{k}}}}),{c}_{\downarrow }^{{{\dagger}} }(-{{{\boldsymbol{k}}}})\end{array}]}^{T}\) is the Nambu spinor. One can directly extract the Green’s function G for the band fermions as

In evaluating physical quantities such as the pairing correlation function, one should first project the observables onto an isolated band, and then apply Wick’s theorem via Gor’kov’s Green function. The projection helps uncover the role of quantum metric in physical quantities such as the coherence length.

Data availability

The data generated from our codes that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bardeen, J., Cooper, L. N. & Schrieffer, J. R. Microscopic theory of superconductivity. Phys. Rev. 106, 162 (1957).

Carbotte, J. Properties of boson-exchange superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 62, 1027 (1990).

Sigrist, M. & Ueda, K. Phenomenological theory of unconventional superconductivity. Rev. Mod. Phys. 63, 239 (1991).

Blatter, G., Feigel’man, M. V., Geshkenbein, V. B., Larkin, A. I. & Vinokur, V. M. Vortices in high-temperature superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 66, 1125 (1994).

Stewart, S. G. Heavy-fermion systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 56, 755 (1984).

Keimer, B., Kivelson, S. A., Norman, M. R., Uchida, S. & Zaanen, J. From quantum matter to high-temperature superconductivity in copper oxides. Nature 518, 179–186 (2015).

Cao, Y. et al. Unconventional superconductivity in magic-angle graphene superlattices. Nature 556, 43–50 (2018).

Yankowitz, M. et al. Tuning superconductivity in twisted bilayer graphene. Science 363, 1059–1064 (2019).

Arora, H. S. et al. Superconductivity in metallic twisted bilayer graphene stabilized by wse2. Nature 583, 379–384 (2020).

Oh, M. et al. Evidence for unconventional superconductivity in twisted bilayer graphene. Nature 600, 240–245 (2021).

Tian, H. et al. Evidence for Dirac flat band superconductivity enabled by quantum geometry. Nature 614, 440–444 (2023).

Liu, X. et al. Tunable spin-polarized correlated states in twisted double bilayer graphene. Nature 583, 221–225 (2020).

Park, J. M., Cao, Y., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T. & Jarillo-Herrero, P. Tunable strongly coupled superconductivity in magic-angle twisted trilayer graphene. Nature 590, 249–255 (2021).

Park, J. M. et al. Robust superconductivity in magic-angle multilayer graphene family. Nat. Mater. 21, 877–883 (2022).

Hu, X., Hyart, T., Pikulin, D. I. & Rossi, E. Geometric and conventional contribution to the superfluid weight in twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 237002 (2019).

Julku, A., Peltonen, T. J., Liang, L., Heikkilä, T. T. & Törmä, P. Superfluid weight and berezinskii-kosterlitz-thouless transition temperature of twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 101, 060505 (2020).

Peotta, S. & Törmä, P. Superfluidity in topologically nontrivial flat bands. Nat. Commun. 6, 8944 (2015).

Törmä, P., Peotta, S. & Bernevig, B. A. Superconductivity, superfluidity and quantum geometry in twisted multilayer systems. Nat. Rev. Phys. 4, 528–542 (2022).

Julku, A., Peotta, S., Vanhala, T. I., Kim, D.-H. & Törmä, P. Geometric origin of superfluidity in the lieb-lattice flat band. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 045303 (2016).

Liang, L. et al. Band geometry, berry curvature, and superfluid weight. Phys. Rev. B 95, 024515 (2017).

Liang, L., Peotta, S., Harju, A. & Törmä, P. Wave-packet dynamics of bogoliubov quasiparticles: quantum metric effects. Phys. Rev. B 96, 064511 (2017).

Iskin, M. Berezinskii-kosterlitz-thouless transition in the time-reversal-symmetric hofstadter-hubbard model. Phys. Rev. A 97, 013618 (2018).

Iskin, M. Quantum-metric contribution to the pair mass in spin-orbit-coupled Fermi superfluids. Phys. Rev. A 97, 033625 (2018).

Iskin, M. Exposing the quantum geometry of spin-orbit-coupled Fermi superfluids. Phys. Rev. A 97, 063625 (2018).

Mondaini, R., Batrouni, G. G. & Grémaud, B. Pairing and superconductivity in the flat band: Creutz lattice. Phys. Rev. B 98, 155142 (2018).

Iskin, M. Origin of flat-band superfluidity on the Mielke checkerboard lattice. Phys. Rev. A 99, 053608 (2019).

Xie, F., Song, Z., Lian, B. & Bernevig, B. A. Topology-bounded superfluid weight in twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 167002 (2020).

Verma, N., Hazra, T. & Randeria, M. Optical spectral weight, phase stiffness, and t c bounds for trivial and topological flat band superconductors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2106744118 (2021).

Herzog-Arbeitman, J., Peri, V., Schindler, F., Huber, S. D. & Bernevig, B. A. Superfluid weight bounds from symmetry and quantum geometry in flat bands. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 087002 (2022).

Kitamura, T., Yamashita, T., Ishizuka, J., Daido, A. & Yanase, Y. Superconductivity in monolayer fese enhanced by quantum geometry. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 023232 (2022).

Huhtinen, K.-E., Herzog-Arbeitman, J., Chew, A., Bernevig, B. A. & Törmä, P. Revisiting flat band superconductivity: dependence on minimal quantum metric and band touchings. Phys. Rev. B 106, 014518 (2022).

Mao, D. & Chowdhury, D. Upper bounds on superconducting and excitonic phase stiffness for interacting isolated narrow bands. Phys. Rev. B 109, 024507 (2024).

Hofmann, J. S., Berg, E. & Chowdhury, D. Superconductivity, charge density wave, and supersolidity in flat bands with a tunable quantum metric. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 226001 (2023).

Mao, D. & Chowdhury, D. Diamagnetic response and phase stiffness for interacting isolated narrow bands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120, e2217816120 (2023).

Gao, A. et al. Quantum metric nonlinear hall effect in a topological antiferromagnetic heterostructure. Science 381, 181–186 (2023).

Wang, N. et al. Quantum-metric-induced nonlinear transport in a topological antiferromagnet. Nature 621, 487–492 (2023).

Kaplan, D., Holder, T. & Yan, B. Unification of nonlinear anomalous hall effect and nonreciprocal magnetoresistance in metals by the quantum geometry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 026301 (2024).

Yu, J. et al. Non-trivial quantum geometry and the strength of electron–phonon coupling. Nat. Phys. 20, 1–7 (2024).

Chen, S. A. & Law, K. Ginzburg-landau theory of flat-band superconductors with quantum metric. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 026002 (2024).

Provost, J. & Vallee, G. Riemannian structure on manifolds of quantum states. Commun. Math. Phys. 76, 289–301 (1980).

Berry, M. V. Quantal phase factors accompanying adiabatic changes. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A. Math. Phys. Sci. 392, 45–57 (1984).

Klitzing, K. V., Dorda, G. & Pepper, M. New method for high-accuracy determination of the fine-structure constant based on quantized hall resistance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 494 (1980).

Thouless, D. J., Kohmoto, M., Nightingale, M. P. & den Nijs, M. Quantized Hall conductance in a two-dimensional periodic potential. Phys. Rev. Lett. 49, 405 (1982).

Bellissard, J., van Elst, A. & Schulz-Baldes, H. The noncommutative geometry of the quantum hall effect. J. Math. Phys. 35, 5373–5451 (1994).

Hasan, M. Z. & Kane, C. L. Colloquium: topological insulators. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 3045–3067 (2010).

Qi, X.-L. & Zhang, S.-C. Topological insulators and superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1057–1110 (2011).

Shapere, A. & Wilczek, F. Geometric Phases in Physics, Vol. 5 (World Scientific, 1989).

Anandan, J. & Aharonov, Y. Geometry of quantum evolution. Phys. Rev. Lett. 65, 1697 (1990).

Marzari, N. & Vanderbilt, D. Maximally localized generalized Wannier functions for composite energy bands. Phys. Rev. B 56, 12847 (1997).

Simon, S. H. & Rudner, M. S. Contrasting lattice geometry dependent versus independent quantities: Ramifications for berry curvature, energy gaps, and dynamics. Phys. Rev. B 102, 165148 (2020).

Han, Z., Herzog-Arbeitman, J., Bernevig, B. A. & Kivelson, S. A. "quantum geometric nesting" and solvable model flat-band systems. Phys. Rev. X 14, 041004 (2024).

Annett, J. F. Superconductivity, Superfluids and Condensates, Vol. 5 (Oxford University Press, 2004).

Hofmann, J. S., Chowdhury, D., Kivelson, S. A. & Berg, E. Heuristic bounds on superconductivity and how to exceed them. npj Quantum Mater. 7, 83 (2022).

Roy, R. Band geometry of fractional topological insulators. Phys. Rev. B 90, 165139 (2014).

Sun, K., Gu, Z., Katsura, H. & Das Sarma, S. Nearly flatbands with nontrivial topology. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 236803 (2011).

Yang, S., Gu, Z.-C., Sun, K. & Das Sarma, S. "Topological flat band models with arbitrary chern numbers”. Phys. Rev. B—Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 86, 241112 (2012).

Mitscherling, J. & Holder, T. Bound on resistivity in flat-band materials due to the quantum metric. Phys. Rev. B 105, 085154 (2022).

Ledwith, P. J., Tarnopolsky, G., Khalaf, E. & Vishwanath, A. Fractional Chern insulator states in twisted bilayer graphene: an analytical approach. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 023237 (2020).

Da Liao, Y. et al. Correlation-induced insulating topological phases at charge neutrality in twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. X 11, 011014 (2021).

Song, Z.-D. & Bernevig, B. A. Magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene as a topological heavy fermion problem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 047601 (2022).

Chou, Y.-Z. & Das Sarma, S. Kondo lattice model in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 026501 (2023).

Herzog-Arbeitman, J. et al. Topological heavy fermion principle for flat (narrow) bands with concentrated quantum geometry. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.07253 (2024).

Hu, H. et al. Symmetric kondo lattice states in doped strained twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 166501 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Polynomial sign problem and topological mott insulator in twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. B 107, L241105 (2023).

Hu, H., Bernevig, B. A. & Tsvelik, A. M. Kondo lattice model of magic-angle twisted-bilayer graphene: Hund’s rule, local-moment fluctuations, and low-energy effective theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 026502 (2023).

Kolár, K., Shavit, G., Mora, C., Oreg, Y. & von Oppen, F. Anderson’s theorem for correlated insulating states in twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 076204 (2023).

Kwan, Y. H. et al. Kekulé spiral order at all nonzero integer fillings in twisted bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. X 11, 041063 (2021).

Bistritzer, R. & MacDonald, A. H. Moiré bands in twisted double-layer graphene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 12233–12237 (2011).

Mera, B. & Mitscherling, J. Nontrivial quantum geometry of degenerate flat bands. Phys. Rev. B 106, 165133 (2022).

Herzog-Arbeitman, J., Chew, A., Huhtinen, K.-E., Törmä, P. & Bernevig, B. A. Many-body superconductivity in topological flat bands. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.00007 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank Adrian Po for illuminating discussions. K.T.L. acknowledges the support of the Ministry of Science and Technology, China, and Hong Kong Research Grant Council through Grants No. 2020YFA0309600, No. RFS2021-6S03, No. C6053-23G, No. AoE/P-701/20, No. 16310520, No. 16310219, No. 16307622, and No. 16311424.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.T.L. and S.C. conceived the project. J.-X.H. performed the major part of the calculations and analysis. J.-X.H., S.C., and K.T.L. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors. All authors are involved in the discussions.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

This manuscript has been previously reviewed at another journal that is not operating a transparent peer review scheme. The manuscript was considered suitable for publication without further review at Communications Physics. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, JX., Chen, S.A. & Law, K.T. Anomalous coherence length in superconductors with quantum metric. Commun Phys 8, 20 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-024-01930-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-024-01930-0

This article is cited by

-

Quantum geometry in quantum materials

npj Quantum Materials (2025)

-

Emergent Haldane model and photon-valley locking in chiral cavities

Communications Physics (2025)

-

Flat-band Fulde-Ferrell-Larkin-Ovchinnikov state from quantum geometric discrepancy

Quantum Frontiers (2025)