Abstract

Neural networks have shown to be a powerful tool to represent the ground state of quantum many-body systems, including fermionic systems. However, efficiently integrating lattice symmetries into neural representations remains a significant challenge. In this work, we introduce a framework for embedding lattice symmetries in fermionic wavefunctions and demonstrate its ability to target both ground states and low-lying excitations. Using group-equivariant neural backflow transformations, we study the t-V model on a square lattice away from half-filling. Our symmetry-aware backflow significantly improves ground-state energies and yields accurate low-energy excitations for lattices up to 10 × 10. We also compute accurate two-point density-correlation functions and the structure factor to identify phase transitions and critical points. These findings introduce a symmetry-aware framework important for studying quantum materials and phase transitions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Strong correlations lead to rich physical phenomena in quantum many-body systems, such as metal-insulator transitions, spin-charge separation, and the paradigmatic fractional quantum Hall effect1,2,3,4. The strong interactions among particles in these systems make their description complex. Various numerical methods have been developed to tackle the strongly correlated regime, including variational approaches such as variational Monte Carlo (VMC)5 and tensor network methods6. Machine learning has recently found its application in quantum many-body physics to introduce flexible and powerful parameterizations of quantum states. This is guided by the capacity of neural networks to act as universal and efficient high-dimensional function approximators7. They have shown great potential, often resulting in state-of-the-art ground state approximations, especially in 2D8,9,10,11,12,13, and have also found their application in dynamics7,14,15,16,17,18,19,20.

Neural network quantum states (NQS)7 have also been used to simulate fermionic systems in the first and second quantization formalisms21,22,23,24,25,26,27. In the latter, the fermionic anticommutation relations make variational approaches challenging. This is particularly clear when mapping fermionic operators onto spin operators, e.g. using Jordan-Wigner in >1D, where these mappings introduce a highly nonlocal spin Hamiltonian28. On the other hand, in the first quantization formalism one must exactly fulfill the particle-permutation antisymmetry of the wave function. A conventional variational wavefunction typically involves a (mean-field) Slater determinant to account for antisymmetry, combined with a two-body Jastrow factor29 to capture particle correlations. One way to further improve this ansatz is by introducing correction terms known as backflow transformations (BF). This modification involves making the orbitals within the Slater determinant depend on the positions of all fermions. Feynman and Cohen originally introduced the idea to analyze the excitation spectrum of liquid Helium-430, and it was successfully extended to electronic degrees of freedom31,32,33,34,35. Backflow transformations can alter the nodal surface, thereby reducing approximation errors32,36,37,38. Recently, the backflow transformation has been introduced as a neural network in the context of NQS applied to discrete39 and continuous26,27 fermionic systems. For spin degrees of freedom, it has been demonstrated that embedding symmetries into NQS can greatly improve ground state accuracy13,21,40,41,42,43,44,45,46. Furthermore, restoring the symmetries of the system enables us to target low-lying excited states that can be classified by the different symmetry sectors21,40. One general way to target the low-energy states of the symmetry sectors is by applying quantum-number projectors to the wave function21.

In this work, we introduce a method for embedding lattice symmetries of 2D fermionic lattice Hamiltonians into neural backflow transformations and demonstrate its efficacy using Slater-Backflow-Jastrow wavefunction ansatzes. Our approach incorporates symmetry-aware neural backflow transformations, fulfilling equivariance conditions for translational and particle-permutation symmetries through convolutional neural networks (CNN). By employing quantum number projection, we symmetrize the wavefunction and accurately target low-lying excited states by varying quantum numbers such as total momentum.

We benchmark our ansatz on the t-V model on a square lattice and find that it significantly increases the ground-state accuracy compared to other state-of-the-art approaches. Additionally, it enables precise determination of low-lying excited states over a wide range of interaction strengths. The results demonstrate the robustness of this approach in capturing phase transitions and identifying the critical interaction strength. Furthermore, a V-score analysis highlights the improved variational accuracy of our method across diverse interaction strengths, system sizes, and excitations, showcasing the effectiveness of symmetry-aware neural backflow transformations for fermionic systems.

Results

Hamiltonian and Observables

The Hamiltonian of the t-V model reads

The first term describes electron hopping between neighboring sites with hopping parameter t. The second term corresponds to the nearest neighbor Coulomb repulsion with interaction strength V ≥ 0. We will set t = 1 from hereon. We further decompose the Hilbert space \({{{\mathcal{H}}}}\) into fixed particle-number subspaces \({{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{{N}_{f}}\)47. The t-V model was originally introduced to study the thermodynamic and transport properties of superconductors48,49. Additionally, it provides a conceptual framework for explaining phenomena such as phase separation or stripe order in cuprates and organic conductors50,51,52,53,54,55. In practice, the t-V model can be realized, for example, in experiments with strongly polarized 3He atoms56,57, or using cold atoms in optical lattices with Rydberg dressing58. Despite its apparent simplicity, the t-V model cannot be solved analytically in two or higher dimensions. It also reveals highly nontrivial phase transitions that have been studied in previous works with various computational techniques, including variational Monte Carlo22,50,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66.

In the strong-coupling limit where V/t → ∞ we encounter a charge-ordering (CO) phase where the system behaves classically. At large V/t, it is energetically unfavorable for two fermions to occupy neighboring lattice sites. The correlations become short-ranged, suggesting localization and insulating behavior, giving rise to a charge-ordered insulating phase. At half-filling, where the particle density is \(\bar{n}=0.5\), the charge order forms a checkerboard pattern. Conversely, at weak interaction strengths V/t, the fermions can easily hop between neighboring lattice sites, and the system behaves like a non-interacting free Fermi gas. In this weak coupling limit the system enters the metallic phase and becomes exactly solvable at V/t → 022,59,60,67,68,69,70,71,72.

We introduce the normalized density-density correlation function as22

where \({S}_{R}(i)=\{j\in {{{\mathcal{V}}}}:d(i,j)=R\}\) is the set of vertices with a fixed distance R from the vertex i. Another important observable to detect the CO phase is the structure factor59,60,62,63,73:

In the CO phase, well-defined peaks at K = (π, π) indicate a checkerboard charge pattern, and in the thermodynamic limit S((π, π))/Ns converges to a finite value, reflecting long-range order.

We will study the t-V model on a two-dimensional square lattice of side L and with periodic boundary conditions, for various system sizes \(| {{{\mathcal{V}}}}| ={L}^{2}\) and different interaction strengths V/t, with densities close to half-filling and at closed momentum shells.

Ground States

We benchmark our symmetrized Neural Slater-Backflow-Jastrow (\({\psi }_{BF}^{K}\)) ansatz with respect to a mean-field Slater determinant (which is equivalent to Hartree-Fock (HF)), a symmetrized Slater-Jastrow (ψK) without backflow, and a non-symmetrized Slater-Jastrow. Furthermore, we compare our results with ground state energies obtained using another state-of-the-art neural quantum state method, specifically the “Slater-Jastrow with an additional sign correction neural network" ansatz from ref. 22. In their method, they do not use the symmetry-averaging process. Instead, they employ a Slater-Jastrow-inspired ansatz with deep residual networks and convolutional residual blocks to approximately determine the ground state of spinless fermions on a square lattice with nearest-neighbor interaction. The ansatz is a modified Hartree-Fock wavefunction, enhanced by a Jastrow factor and a sign-correcting neural network, both of which are constructed to be invariant under certain lattice symmetries.

It is important to note that the simulations in this section for the different system sizes are performed in an open shell domain, where fermions occupy the lowest-energy available states. In the context of spinless fermions, a “closed shell” configuration occurs when all momentum states within the Fermi surface are fully occupied, typically resulting in a non-degenerate ground state with total momentum K = (0, 0). In contrast, an “open shell” configuration arises when some momentum states remain unfilled, leading to a partially filled Fermi surface and potentially different total momenta for the ground state. Thus, in our open shell setup, the ground state does not necessarily correspond to K = (0, 0).

In Fig. 1a, we present results for a small system size L = 4 at a density of \(\bar{n}=0.44\) and ground state momentum K = (π, 0), allowing comparison to results obtained by exact diagonalization (ED). Mean-field Slater relative errors range from 10−3 to 10−1, with accuracies decreasing at large interaction strengths V/t. Our symmetrized backflow ansatz consistently yields ground-state errors below 10−3, also at higher values of V/t, and achieves lower errors compared to other state-of-the-art methods. We also observe that the symmetry-aware backflow transformation yields the most accurate ground-state energies over the whole interaction regime. For a larger system size L = 10, at a density of \(\bar{n}=0.44\) and ground state momentum \({{{\bf{K}}}}=(\frac{3\pi }{5},\frac{2\pi }{5})\), shown in Fig. 1b, this trend is confirmed. The backflow corrections significantly lower the estimated ground-state energy across all coupling strengths. We compare the converged VMC energies with HF energies by computing the difference E − EHF. Our results show that the backflow ansatz consistently provides lower energies across the full range of interaction strengths.

We evaluate the performance of the symmetrized Neural Slater-Backflow-Jastrow (\({\psi }_{BF}^{K}\), red) against several other wavefunction models: symmetrized Slater-Jastrow without backflow (ψK, yellow), non-symmetrized mean-field Slater (blue), and non-symmetrized Slater-Jastrow (green). Additionally, we compare to the neural quantum state “Slater-Jastrow with an additional sign correction neural network” described in ref. 22 (black). In panel a, results are presented for a lattice size L = 4 with \(\bar{n}=0.44\), showing relative errors compared to exact diagonalization (ED) as a function of the interaction strengths V/t. Panel b shows the deviation from Hartree-Fock (HF) energies, defined as E − EHF, for a system with L = 10 and a filling fraction \(\bar{n}=0.44\). Error bars in both panels represent the corresponding standard deviations, where provided.

In Fig. 2a, we show the density-density correlation function as defined in Eq. (2) for L = 10 close to half-filling \(\bar{n}=0.44\) (see Supplementary Note II for results on the 8 × 8 system). When the interaction strength increases, the correlations start to oscillate more pronouncedly as a result of the increasingly ordered charge distribution. In the CO phase, the amplitudes of the oscillations decrease more gradually with distance compared to that of the metallic phase. For weak couplings, the correlations barely oscillate and fade as the graph distance R increases.

a The two-point density-density correlation functions as a function of graph distance R for different interaction strengths V/t for a system size of L = 10 and particle density \(\bar{n}=0.44\). b Finite-size scaling of the structure factor S(π, π)/Ns versus different system sizes 1/L (where L = 4, 6, 8, 10) with \(\bar{n}=0.44\) for different values of V/t close to the estimated critical point Vc/t ≃ 1.14 ± 0.04. Error bars represent the corresponding standard deviations.

To pinpoint the transition point in the thermodynamic limit, we use finite-size scaling. We study the structure factor S(π, π)/Ns for various V/t. The critical transition point is found where the structure factor attains a finite value in the thermodynamic limit. In Fig. 2b we plot the structure factor S(π, π)/Ns as a function of the inverse system size 1/L (for L = 4, 6, 8, 10) and in Table 1 we report the extrapolated results in the thermodynamic limit.

We apply a least squares regression using the SciPy74 library to fit the data and extrapolate S(π, π)/Ns to the thermodynamic limit. In the metallic phase, the structure factor is expected to vanish for large system sizes, such that there exists a finite critical system size, Lc, beyond which the order parameter vanishes. This reflects the short-range nature of correlations in the metallic phase, which become negligible as the system size increases, causing the structure factor to diminish and ultimately disappear. In contrast, in the CO phase, Lc tends to infinity, meaning the structure factor remains finite in the thermodynamic limit. The critical interaction strength, Vc/t, was identified at the point where the extrapolated S∞ transitions from the metallic phase to a positive finite value in the CO phase, signaling the onset of long-range order. Error estimates for Vc/t were calculated using error propagation, based on the uncertainties in S∞ at these transition points.

Near half-filling, specifically for \(\bar{n}=0.44\), we estimate that the transition occurs at Vc/t ≃ 1.14 ± 0.04, which is consistent with the value reported in ref. 22. While the order parameter from Eq. (3) of ref. 22 explicitly assumes a symmetry-broken ground state, we enforce the symmetry and nevertheless find a transition point compatible with ref. 22 using the density-density structure factor. We selected a density close to half-filling to observe the metallic to CO phase transition while avoiding the need for interpolating densities. This choice allowed us to explore conditions slightly doped away from half-filling, given that the phases at exact half-filling have already been extensively studied22,50,59,60,62,63.

Excitations

To capture low-lying excitations, we carry out VMC optimizations across various momentum sectors K = (ku, kv), where \({k}_{u,v}\in \{0,\pm \frac{2\pi m}{{L}_{u,v}}\,| \,m=1,2,\ldots ,\frac{{L}_{u,v}}{2}\}\). Here Lu and Lv are the side lengths of the two-dimensional lattice in the eu and ev directions. In Fig. 3, we represent a single quadrant within the corresponding first Brillouin zone with conventional symbols to represent high-symmetry points75.

We first benchmark the performance of our symmetrized Neural Slater-Backflow-Jastrow variational ansatz (\({\psi }_{BF}^{K}\)) and a symmetrized Slater-Jastrow (ψK) (top) model for a system size of L = 4 and \(\bar{n}=0.31\) in Fig. 4. We observe that also in symmetry sectors different from the ground state, the symmetric backflow transformation reduces the relative energy error. We show the lowest energy state in each sector and compare it with results obtained from ED. In the lower panel of Fig. 4, we calculate the corresponding relative errors with respect to the ED energies. For our backflowed ansatz (\({\psi }_{BF}^{K}\)) these lie between 10−6 − 10−3 for all sectors. In Supplementary Note IV, we also include additional simulation data of the open shell L = 4 system (see Fig. S3).

a The lowest (\({E}_{0}^{K}\), teal horizontal lines) and second-lowest energies (\({E}_{1}^{K}\), yellow horizontal lines) for the designated K sector using exact diagonalization (ED), compared to the lowest energies in each sector obtained with our variational ansatzes: symmetrized Neural Slater-Backflow-Jastrow (\({\psi }_{BF}^{K}\), blue) and symmetrized Slater-Jastrow without backflow (ψK, red). b The relative energy errors associated with the ansatzes with respect to the lowest energy in each sector. These results are for a closed-shell system with lattice size L = 4 and a density of \(\bar{n}=0.31\). Error bars represent the corresponding standard deviations.

Prior studies have documented a range of coexistence phenomena for large and finite V/t away from half-filling, transitioning from phase separation to potential stripe and checkerboard coexistence. In ref. 76, the t-V model on a square lattice with nearest-neighbor repulsive interactions was studied using mean-field theory for small system sizes. The authors observed a second-order phase transition from the Fermi liquid to the (π, π) charge density wave state. At stronger repulsion, charge density waves coexisted at different momentum sectors when doped away from half-filling. In ref. 53 and the subsequent study in ref. 54, exact diagonalization was used to study small 2D systems. They found that at high repulsion and around quarter-filling densities, doped holes formed stable charged stripes acting as anti-phase walls77, which are stable against phase separation in fermionic systems.

We extend our analysis to larger system sizes L = 8 with \(\bar{n}=0.39\) and L = 10 with \(\bar{n}=0.41\) to reduce finite-size effects. We simulate each system size with distinct particle densities to ensure they remain within the closed-shell domain, avoiding ground-state degeneracies in the non-interacting limit. We confirm the persistent non-degenerate ground state at the Γ = (0, 0) point (see Fig. 5 for L = 8 and Fig. S2 in Supplementary Note III for L = 10). By comparing our symmetrized Neural Slater-Backflow-Jastrow (\({\psi }_{BF}^{K}\)) ansatz with a symmetrized Slater-Jastrow (ψK) without backflow, we observe improved energy levels, even for low-lying excited states, with the inclusion of the backflow correction term.

Lowest excitation energies in different K sectors for a lattice of size L = 8, corresponding to a closed-shell configuration with particle density \(\bar{n}=0.39\), evaluated across various interaction strengths V/t. Results are shown for symmetrized Neural Slater-Backflow-Jastrow (\({\psi }_{BF}^{K}\), blue) and symmetrized Slater-Jastrow without backflow (ψK, red). Error bars represent the corresponding standard deviations.

In Fig. 6 we depict the gap between the ground state Γ and the excited energy levels in different sectors for different V/t for both system sizes. We define the gap as the difference between the lowest energies in each sector relative to the lowest energy in the Γ sector: ΔK = ∣E0[Γ] − E0[K]∣, where K corresponds to the symbols of different sectors (here K = M, X) and E0[K] is the lowest energy in given sector. Notably, for strong interactions, we consistently observe a smaller gap for ΔM than for ΔX. We include the gap ΔK∞ for the V/t = ∞ value in the plot for both system sizes. This demonstrates a collapse in the interactions at infinite strength, indicating a charge-ordered phase where the electrons are fully localized. Furthermore, the gap between the lowest energy states in the M and X sectors appears largest in the intermediate coupling regime.

Energy gaps ΔK between the ground state (located at the Γ point) and excitation energies (K = M, green; K = X, blue) for a) L = 8 lattice with filling factor \(\bar{n}=0.39\) and b) L = 10 lattice with filling factor \(\bar{n}=0.41\), both being closed-shell systems with no ground state degeneracy. We include ΔK∞ for interaction strength V/t = ∞ in both figures, showing a collapse to a fully localized, charge-ordered phase at infinite repulsion. Error bars represent the corresponding standard deviations.

V-score

We now aim to generalize the assessment of the performance of our model. Since ED becomes intractable for larger system sizes, we rely on the recently introduced V-score as a guiding metric78, which can be computed using the variational energy and its variance. The V-score is dimensionless and invariant under energy shifts by construction. It is defined as78:

where N = Nf the number of degrees of freedom, VarE is the variance, E is the variational energy and for the t-V model

where V is the interaction strength and \(| {{{\mathcal{E}}}}|\) is the number of nearest neighbor bonds. The constant E∞ is used to compensate for global shifts in the energy, depending on the definition of the Hamiltonian.

The V-score serves as a valuable tool for discerning which Hamiltonians and regimes pose challenges for arbitrary classical variational techniques, even when we lack prior knowledge about the precise exact solution. Its practicality lies in its ability to quantify the accuracy of a particular method independently, without the need for direct comparisons with other methods. The intuition behind the V-score is that the energy variance, which becomes zero for an exact ground state, serves as a direct measure of how close a variational state is to the true ground state. This allows us to infer the accuracy of a method based on the variance alone. In particular, this metric enables us to draw comparisons between the accuracy obtained with our method on the given Hamiltonian, compared to other commonly studied condensed matter Hamiltonians, including spin Hamiltonians.

In Fig. 7, we present the ground state V-scores for different ansatzes, including the symmetrized Neural Slater-Backflow-Jastrow (\({\psi }_{BF}^{K}\)), symmetrized Slater-Jastrow (ψK) and Hartree-Fock (HF) ansatz, for system sizes L = 4 with \(\bar{n}=0.31\), and L = 10 with \(\bar{n}=0.41\). The data clearly illustrate a strong dependence of V-scores on the specific interaction regime under investigation. In particular, as the V score values increase, it becomes increasingly challenging to achieve accurate solutions using demanding variational algorithms, implying a greater level of difficulty in solving these systems accurately. Despite these challenges, we observe that the backflow ansatz consistently exhibits lower V-scores compared to other methods, indicating its more accurate performance.

Ground state V-scores as a function of interaction strength V/t are compared for different ansatzes: \({\psi }_{BF}^{K}\) (symmetrized backflow Slater-Jastrow, blue/green), ψK (symmetrized Slater-Jastrow, violet/orange), and HF (Hartree-Fock, red/yellow), shown for system sizes L = 4 with particle density \(\bar{n}=0.31\) (triangles) and L = 10 with \(\bar{n}=0.41\) (stars).

Next, we analyze the V-scores of our backflow ansatz for ground states and excitations, as depicted in Fig. 8, across various scenarios and closed-shell system sizes (L = 4 with \(\bar{n}=0.31\), L = 8 with \(\bar{n}=0.39\), and L = 10 with \(\bar{n}=0.41\)). We compute the scores across a range of interactions V/t. We observe that we obtain similar V-scores for excited states as for ground states at all system sizes and interaction strengths. This indicates that our results for excited states are highly accurate, even in the large V/t regime.

V-score for a symmetrized Neural Slater-Backflow-Jastrow as a function of interaction strengths V/t for ground (GS, triangles) and excited states (stars). Data are presented for different system sizes L and particle densities \(\bar{n}\): L = 4 with \(\bar{n}=0.31\) (blue), L = 8 with \(\bar{n}=0.39\) (yellow), and L = 10 with \(\bar{n}=0.41\) (red). Note that excitation data are available for V/t values in the set {0.0, 0.1, 1.0, 10.0}, while ground-state data cover a broader range, including {0.0, 0.1, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, 6.0, 10.0}.

Discussion

In this work, we introduced an approach to studying the low-energy excitation spectrum of fermionic Hamiltonians. By introducing symmetry-aware neural backflow transformations, we show that we can target the eigenstates of fermionic Hamiltonians with high accuracy. As a benchmark comparison, we show that this approach also yields significantly more accurate ground-state energies than other state-of-the-art variational Monte Carlo approaches.

In particular, we introduce equivariance conditions for the backflow transformations that lead to an efficient symmetry projection. We show that convolutional neural networks yield a powerful parametrization for our symmetry-aware backflow transformations that fulfill the equivariance conditions for both translation and particle-permutation symmetry. This key contribution enables us to efficiently access excited states by varying the total momentum K in the quantum number projection. Furthermore, we have showcased the utility of our approach in identifying phase-transitions on the t-V model at system sizes far beyond what is reachable with exact diagonalization. To this end, we computed correlation functions and structure factors, resulting in the pinpointing of the critical point at Vc/t = 1.14. We also computed the V-score to quantify the variational accuracy of our proposed ansatz for different interaction regimes, system sizes, and excitations. Previous analysis based on the V-score has highlighted the challenging nature of targeting fermionic eigenstates. Our observations indicate that the symmetry-aware backflow ansatz yields accurate ground states and performs favorably compared to other state-of-the-art methods over the full interaction regime, including when strong correlations occur. Additionally, we find that our method yields accurate approximations to the low-energy eigenstates with a given K momentum.

Future extensions of our approach include generalizing it by including additional symmetries, such as rotational and reflection symmetries. This will involve using more general group-convolutional kernels, as in group-convolutional neural networks (GCNN)79,80,81. This would require addressing the increased computational demands as the number of symmetry elements grows. We focused on the nearest neighbor t-V model, but an extension is to consider Hamiltonians where spin-degrees of freedom become relevant as well (such as the Fermi-Hubbard model), or where interactions beyond nearest neighbor terms become relevant.

Methods

Fermions on the lattice

Consider a system of fermions that reside on a lattice represented by an undirected graph \({{{\mathcal{G}}}}=({{{\mathcal{V}}}},{{{\mathcal{E}}}})\), with a set of vertices denoted \({{{\mathcal{V}}}}\) and undirected edges as \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}\). Each lattice site is labeled \(i\in {{{\mathcal{V}}}}\), and the total number of sites is \({N}_{s}=| {{{\mathcal{V}}}}|\). To each vertex i we associate a position vector ri. The total number of fermions is conserved and will be fixed at Nf ≤ Ns, and the particle density is defined as \(\bar{n}=\frac{{N}_{f}}{{N}_{s}}\). We introduce the creation and annihilation operators of the fermionic mode (or lattice site) i as \({\hat{c}}_{i}^{{{\dagger}} }\) and \({\hat{c}}_{i}\), respectively, and do not consider the spin of the fermions. These operators respect the usual fermionic anticommutation relations. In addition, we also introduce the corresponding number operator \({\hat{n}}_{i}={\hat{c}}_{i}^{{{\dagger}} }{\hat{c}}_{i}\).

It will prove useful to connect the two main formalisms for describing fermionic systems: first quantization, which labels the fermions, and second quantization where we consider the occupation number basis or a given orbital set (here the lattice sites). To establish the correspondence, we consider a canonical ordering of the lattice sites through their label assignment i = {1, . . . , Ns}. The latter can be chosen arbitrarily, and in practice we choose a zigzag-like ordering in the case of the 2D lattice. This enables us to recover the particle positions in the first quantization framework from a given occupation number configuration in second quantization (see ref. 22). We introduce \(x=({{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{{i}_{1}},{{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{{i}_{2}},\ldots ,{{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{{i}_{{N}_{f}}})\), where ip is the site index occupied by the pth electron, where the fermion number index is determined by the chosen canonical ordering. In other words, we have an ordered set of indices \({i}_{1} \, < \, {i}_{2} \, < \, .. \, < \, {i}_{{N}_{f}}\). Furthermore, we introduce the occupation number configuration \(n=({n}_{1},\ldots ,{n}_{{N}_{s}})\in {\{0,1\}}^{{N}_{s}}\). Hence, in this notation, the canonical ordering allows us to extract active or occupied lattice indices \({\{{i}_{p}\}}_{p = 1,\ldots ,{N}_{f}}\), given the occupation numbers n. This establishes implicit mappings x = x(n) and n = n(x) (see Fig. 9).

This figure shows how the occupation configuration \(n=({n}_{1},\ldots ,{n}_{{N}_{s}})=(0,0,1,1,0,0,0,1,0)\) maps to the position vectors \(x=({{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{{i}_{1}},{{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{{i}_{2}},\ldots ,{{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{{i}_{{N}_{f}}})\), and vice versa, illustrating the relationship between occupied lattice sites and their indices respecting a canonical ordering.

Wavefunction ansatz

Slater-Jastrow

Consider a set of Nf single-particle mean-field (MF) orbitals \({\{{\phi }_{\mu }\left({{{\bf{r}}}}\right)\}}_{\mu = 1,\ldots ,{N}_{f}}\) evaluated at position r. For convenience, we introduce the matrix \(M\in {{\mathbb{C}}}^{{N}_{f}\times {N}_{s}}\), with elements defined as

for all Ns sites i. For a given set of particle positions x, we define the reduced matrix \(\overline{M}\in {{\mathbb{C}}}^{{N}_{f}\times {N}_{f}}\) by selecting the columns of M corresponding to the occupied sites: \(\overline{M}={M}_{\mu ,{i}_{p}}\), where ip are the lattice sites that are occupied by particle p ∈ {1, . . , Nf}.

The mean-field Slater determinant can be dressed with a Jastrow factor that introduces two-body correlations, and we obtain:

The two-body Jastrow factor is defined as29,82

where the subscript d(ij) of the complex variational parameters W denotes the distance between site i and j.

Neural Backflow Transformation

The Slater-Jastrow wavefunction ansatz can be further improved by including backflow transformations, thereby significantly increasing the expressiveness of the model. We use the neural backflow transformation that effectively promotes the single-particle orbitals to many-body orbitals26,27,39. Therefore, we introduce the backflow function F that produces a configuration-dependent orbital matrix \(F\in {{\mathbb{C}}}^{{N}_{f}\times {N}_{s}}\). We then adapt the orbital matrix as

where ∘ corresponds to an element-wise product between the matrices M and F. The corresponding reduced matrix of B is \(\bar{B}\), and is obtained similarly as for \(\overline{M}\). The Neural Slater-Backflow-Jastrow ansatz is then defined as

Below, we will describe the properties of the backflow function F and introduce a neural parametrization thereof.

Symmetries and Excitations

We consider an electronic Hamiltonian on a lattice that commutes with the elements of a symmetry group G, such as total spin, the total momentum, and geometrical symmetries such as rotation. The eigenstates of the many-body Hamiltonian can be classified with the symmetry sectors of G. We restrict the NQS ansatz to a given symmetry sector labeled by I through a quantum-number projection

and \({\chi }_{g}^{I}\) is the character corresponding to the irreducible representation (irrep) I and group element g. To make the notation more explicit, consider a translation operator denoted by \(\hat{g}={\hat{T}}_{{{{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}}}\), where τ is the corresponding translation vector. The effect of the operator on a configuration n is to permute the site indices \((1,\ldots ,{N}_{s})\to ({\tau }_{1},\cdots \,,{\tau }_{{N}_{s}})\), i.e. \({\hat{T}}_{{{{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}}}\vert n\rangle =\vert {n}_{{\tau }_{1}},\cdots \,,{n}_{{\tau }_{{N}_{s}}}\rangle\) where in terms of the position map \({n}_{{\tau }_{i}}=n({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{i}-{{{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}})\). In this work we focus on the projected form

where K is the total momentum and the sum runs over all possible translation vectors. Due to the antisymmetric nature of the wavefunction, translating fermions can lead to a change in the sign of the wavefunction, depending on how their positions are permuted. This effect is naturally handled by the above-mentioned quantum number projection with corresponding characters, ensuring that the fully symmetrized wavefunction remains translationally invariant.

We use this approach to compute both the ground state and the low-lying excited states. The low-lying excitations are characterized by different momentum sectors, and their computation involves optimizing the wavefunction within the quantum number sectors distinct from the ground state43,45. Instead of focusing on a single excited state individually, an alternative strategy involves adopting a multi-target approach, which has recently been introduced for continuous systems83. However, for cost-effectiveness and interpretation in terms of translation quantum numbers, we focus on the symmetry-projection method outlined above.

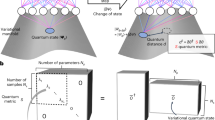

In a brute-force approach, the evaluation of the symmetrized wave function ψI(n) for a configuration n would require \(\left\vert G\right\vert\) evaluations of the parametrized non-symmetric wave function ψ in Eq. (11). In particular, for translation symmetry in Eq. (12) of a square lattice of size L × L, this would require \(\left\vert G\right\vert ={L}^{2}\) evaluations. The computational burden induced by the symmetrization procedure can therefore become significant for increasing system sizes. For this purpose, we introduce a set of symmetry-aware neural backflow transformations that are constructed as equivariant functions, requiring only a single evaluation of a neural network to produce all \(\psi \,({\hat{g}}^{-1}n)\) (i.e. ∀ g ∈ G) required to evaluate the projection in Eq. (11). This will allow us to reach larger system sizes, even when considering deep neural networks to represent the backflow transformation. In the next section, we discuss the requirements of this symmetry-aware backflow transformation and introduce a specific neural parametrization to fulfill the constraints.

Equivariance Condition

We will introduce backflow transformations that keep both the particle-permutation and lattice symmetries manifest, by introducing transformations that are equivariant under the respective groups. More concretely, when two fermions p and q are exchanged by the permutation operator \({\hat{P}}_{pq}\) or when a lattice-symmetry transformation \(\hat{g}\) is applied to the lattice, the respective outputs of the neural backflow change accordingly:

In the case of translations we enforce \({F}_{\mu ,{i}_{p}}({\hat{T}}_{{{{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}}}^{-1}n)={F}_{\mu ,{\hat{T}}_{{{{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}}}{i}_{p}}(n)={F}_{\mu ,{{{\mathcal{I}}}}({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{{i}_{p}}+\tau )}\), where \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{{i}_{p}}+{{{\boldsymbol{\tau }}}})\) (defined in Fig. 9) denotes the index of the lattice site obtained by shifting \({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{{i}_{p}}\) by the translation vector τ. In other words, lattice symmetries can be defined by their permutation of the lattice sites.

Our key objective is to preserve translation equivariance in the backflow transformation. Using this, we can construct a symmetrized Neural Slater-Backflow-Jastrow ansatz, given that the Jastrow correlation function is translation-invariant and the backflow is constructed as a neural network respecting the equivariance conditions in Eqs. (13) and (14). A natural candidate for a translation-equivariant neural network is a convolutional neural network operating on occupation configurations79,80,81, which naturally exhibits these properties. In a CNN, spatial translations in the input lead to corresponding shifts in the output feature maps, effectively preserving spatial locality. The occupation configurations undergo multiple CNN-transformation layers, resulting in outputs of the same size L2 as the input configuration. This preserves the structure needed to maintain equivariance, without averaging over symmetry group elements as done for invariance. We employ Nf independent backflow transformations corresponding to the different orbitals μ. From the outputs, we obtain the reduced matrix \(\overline{B}\) in Eq. (10), by selecting the columns corresponding to the occupied sites from the resulting backflow matrix Fμ,i(n). We depict this procedure in Fig. 10 where we provide a concise visual representation of a CNN backflow satisfying the equivariance conditions. In summary, given our CNN backflow is equivariant: instead of evaluating the CNN for all elements of the translation symmetry group, we can extract all the required \(\psi \left({\hat{g}}^{-1}n\right)\) in Eq. (11) from the output of a single evaluation of the backflow CNN. This approach improves efficiency and reduces computational redundancy in handling symmetrical transformations. In Fig. 10, we illustrate this symmetry-averaging process under equivariance conditions. For additional information on the architecture and its adaptation to different system sizes, we refer to Supplementary Note I.

Panel a) showcases how the backflow determinants are constructed. The neural network CNNμ for a given orbital μ takes as input the configuration n, and produces a backflow vector output Fμ(n). The reduced matrix \({\bar{F}}_{\mu }\) is obtained by selecting the active indices i from Fμ. These active indices are linked to the occupied sites, represented by the dark green blocks in the input n, using the canonical ordering. Panel b) demonstrates the equivariance property of the backflow function. Applying a symmetry transformation to the input as \({\hat{g}}^{-1}n\) and then extracting the active indices, we get \({\bar{F}}_{\mu }({\hat{g}}^{-1}n)\). This is equivalent to applying the symmetry transformation directly to the active indices represented by \(\hat{g}i\). This results equivalently in the reduced matrix \({\bar{F}}_{\mu \hat{g}}(n)\). Panel c) represents the quantum number projection. Following a single CNN evaluation, we obtain the reduced matrices \({\bar{F}}_{\mu g}\), \(\forall \hat{g}\in G\) by properly constructing the reduced matrix, without reevaluating the backflow CNN. Subsequently, we compute the symmetry-averaged wavefunction \(\psi ({\hat{g}}^{-1}n)\).

Data availability

The data underlying this study are accessible upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Hubbard, J. Electron correlations in narrow energy bands iii. an improved solution. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A. Math. Phys. Sci. 281, 401–419 (1964).

Vijayan, J. et al. Time-resolved observation of spin-charge deconfinement in fermionic hubbard chains. Science 367, 186–189 (2020).

Li, G. et al. Theoretical paradigm for the quantum spin hall effect at high temperatures. Phys Rev. B 98, https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevB.98.165146 (2018).

Avella, A. Strongly correlated systems, vol. 176 (Springer, 2013).

McMillan, W. L. Ground state of liquid he4. Phys. Rev. 138, A442–A451 (1965).

White, S. R. Density matrix formulation for quantum renormalization groups. Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 2863–2866 (1992).

Carleo, G. & Troyer, M. Solving the quantum many-body problem with artificial neural networks. Science 355, 602–606 (2017).

Carleo, G. et al. Machine learning and the physical sciences. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1, https://doi.org/10.1103/revmodphys.91.045002 (2019).

Deng, D.-L., Li, X. & Sarma, S. D. Quantum entanglement in neural network states. Phys. Rev. X 7, https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevX.7.021021 (2017).

Chen, J., Cheng, S., Xie, H., Wang, L. & Xiang, T. Equivalence of restricted boltzmann machines and tensor network states. Phys. Rev. B 97, https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevB.97.085104 (2018).

Ferrari, F., Becca, F. & Carrasquilla, J. Neural gutzwiller-projected variational wave functions. Phys. Rev. B. 100, https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevB.100.125131 (2019).

Hibat-Allah, M., Ganahl, M., Hayward, L. E., Melko, R. G. & Carrasquilla, J. Recurrent neural network wave functions. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevResearch.2.023358 (2020).

Nomura, Y. & Imada, M. Dirac-type nodal spin liquid revealed by refined quantum many-body solver using neural-network wave function, correlation ratio, and level spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. X 11, 031034 (2021).

Czischek, S., Gärttner, M. & Gasenzer, T. Quenches near ising quantum criticality as a challenge for artificial neural networks. Phys. Rev. B 98, 024311 (2018).

Fabiani, G. & Mentink, J. H. Investigating ultrafast quantum magnetism with machine learning. SciPost Phys. 7, 004 (2019).

Schmitt, M. & Heyl, M. Quantum many-body dynamics in two dimensions with artificial neural networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 100503 (2020).

Fabiani, G., Bouman, M. D. & Mentink, J. H. Supermagnonic propagation in two-dimensional antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 097202 (2021).

Hofmann, D., Fabiani, G., Mentink, J. H., Carleo, G. & Sentef, M. A. Role of stochastic noise and generalization error in the time propagation of neural-network quantum states. SciPost Phys. 12, 165 (2022).

Nys, J., Pescia, G. & Carleo, G. Ab-initio variational wave functions for the time-dependent many-electron schrödinger equation. 2403.07447 (2024).

Lin, S.-H. & Pollmann, F. Scaling of neural-network quantum states for time evolution. Phys. status solidi (b) 259, 2100172 (2022).

Choo, K., Mezzacapo, A. & Carleo, G. Fermionic neural-network states for ab-initio electronic structure. Nat Commun. 11, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15724-9 (2020).

Stokes, J., Moreno, J. R., Pnevmatikakis, E. A. & Carleo, G. Phases of two-dimensional spinless lattice fermions with first-quantized deep neural-network quantum states. Phys. Rev. B. 102, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.102.205122 (2020).

Hermann, J. et al. Ab-initio quantum chemistry with neural-network wavefunctions. 2208.12590 (2022).

Pescia, G., Nys, J., Kim, J., Lovato, A. & Carleo, G. Message-passing neural quantum states for the homogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. B 110, 035108 (2024).

Kim, J. et al. Neural-network quantum states for ultra-cold fermi gases. Commun. Phys. 7, https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-024-01613-w (2024).

Pfau, D., Spencer, J. S., Matthews, A. G. D. G. & Foulkes, W. M. C. Ab initio solution of the many-electron schrödinger equation with deep neural networks. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevresearch.2.033429 (2020).

Hermann, J., Schätzle, Z. & Noé, F. Deep-neural-network solution of the electronic schrödinger equation. Nat. Chem. 12, 891–897 (2020).

Nys, J. & Carleo, G. Variational solutions to fermion-to-qubit mappings in two spatial dimensions. Quantum 6, 833 (2022).

Jastrow, R. Many-body problem with strong forces. Phys. Rev. 98, 1479–1484 (1955).

Feynman, R. P. & Cohen, M. Energy spectrum of the excitations in liquid helium. Phys. Rev. 102, 1189–1204 (1956).

Holzmann, M., Ceperley, D. M., Pierleoni, C. & Esler, K. Backflow correlations for the electron gas and metallic hydrogen. Phys. Rev. E 68, 046707 (2003).

Holzmann, M. & Moroni, S. Orbital-dependent backflow wave functions for real-space quantum monte carlo. Phys. Rev. B 99, 085121 (2019).

López Ríos, P., Ma, A., Drummond, N. D., Towler, M. D. & Needs, R. J. Inhomogeneous backflow transformations in quantum monte carlo calculations. Phys. Rev. E 74, 066701 (2006).

Tocchio, L. F., Becca, F., Parola, A. & Sorella, S. Role of backflow correlations for the nonmagnetic phase of the t–\({t}^{{\prime} }\) hubbard model. Phys. Rev. B 78, 041101 (2008).

Tocchio, L. F., Becca, F. & Gros, C. Backflow correlations in the hubbard model: an efficient tool for the metal-insulator transition and the large-u limit. Phys. Rev. B 83, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.83.195138 (2011).

Kwon, Y., Ceperley, D. M. & Martin, R. M. Effects of three-body and backflow correlations in the two-dimensional electron gas. Phys. Rev. B 48, 12037–12046 (1993).

Kwon, Y., Ceperley, D. M. & Martin, R. M. Effects of backflow correlation in the three-dimensional electron gas: Quantum monte carlo study. Phys. Rev. B 58, 6800–6806 (1998).

Hutcheon, M. Stochastic nodal surfaces in quantum monte carlo calculations. Phys. Rev. E 102, https://doi.org/10.1103/physreve.102.042105 (2020).

Luo, D. & Clark, B. K. Backflow transformations via neural networks for quantum many-body wave functions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.122.226401 (2019).

Lange, H., Döschl, F., Carrasquilla, J. & Bohrdt, A. Neural network approach to quasiparticle dispersions in doped antiferromagnets (2023).

Vieijra, T. & Nys, J. Many-body quantum states with exact conservation of non-abelian and lattice symmetries through variational monte carlo. Phys. Rev. B. 104, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.104.045123 (2021).

Vieijra, T. et al. Restricted boltzmann machines for quantum states with non-abelian or anyonic symmetries. Phys.Rev. Lett.124, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.124.097201 (2020).

Mizusaki, T. & Imada, M. Quantum-number projection in the path-integral renormalization group method. Phys. Rev. B. 69, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.69.125110 (2024).

Morita, S., Kaneko, R. & Imada, M. Quantum spin liquid in spin 1/2 j1-j2 heisenberg model on square lattice: Many-variable variational monte carlo study combined with quantum-number projections. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 84, 024720 (2015).

Nomura, Y. Helping restricted boltzmann machines with quantum-state representation by restoring symmetry. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 33, 174003 (2021).

Choo, K., Carleo, G., Regnault, N. & Neupert, T. Symmetries and many-body excitations with neural-network quantum states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevLett.121.167204 (2018).

Jung, J.-H. & Noh, J. D. Guide to exact diagonalization study of quantum thermalization. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 76, 670–683 (2020).

Lam, L. & Bunde, A. Phase transitions and dynamics of superionic conductors. Z. f.ür. Phys. B Condens. Matter 30, 65–78 (1978).

Girvin, S. M. Critical conductivity of the lattice gas. J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 11, L751 (1978).

Czart, W., Robaszkiewicz, S. & Tobijaszewska, B. Charge ordering and phase separations in the spinless fermion model with repulsive intersite interaction. Acta Phys. Polonica Ser. a 114, 129–134 (2008).

Dagotto, E., Hotta, T. & Moreo, A. Colossal magnetoresistant materials: the key role of phase separation. Phys. Rep. 344, 1–153 (2001).

Schulz, H. J. Correlation exponents and the metal-insulator transition in the one-dimensional hubbard model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 64, 2831–2834 (1990).

Henley, C. L. & Zhang, N.-G. Spinless fermions and charged stripes at the strong-coupling limit. Phys. Rev. B. 63 (2001).

Zhang, N. G. & Henley, C. L. Stripes and holes in a two-dimensional model of spinless fermions or hardcore bosons. Phys. Rev. B 68, 014506 (2003).

Ma, K.-H. & Tong, N.-H. Interacting spinless fermions on the square lattice: Charge order, phase separation, and superconductivity. Phys. Rev. B. 104, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.104.155116 (2021).

Partridge, G., Li, W., Liao, Y. & Hulet, R. Pairing, phase separation, and deformation in the bec-bcs crossover. J. Low. Temp. Phys. 148, 323–330 (2007).

Moreo, A. & Scalapino, D. J. Cold attractive spin polarized fermi lattice gases and the doped positive u hubbard model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 216402 (2007).

Weckesser, P. et al. Realization of a rydberg-dressed extended bose hubbard model. https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.20128 (2024).

Gubernatis, J. E., Scalapino, D. J., Sugar, R. L. & Toussaint, W. D. Two-dimensional spin-polarized fermion lattice gases. Phys. Rev. B 32, 103–116 (1985).

Scalapino, D. J., Sugar, R. L. & Toussaint, W. D. Monte carlo study of a two-dimensional spin-polarized fermion lattice gas. Phys. Rev. B 29, 5253–5255 (1984).

de Woul, J. & Langmann, E. Partially gapped fermions in 2d. J. Stat. Phys. 139, 1033–1065 (2010).

Song, J.-P. & Clay, R. T. Monte carlo simulations of two-dimensional fermion systems with string-bond states. Phys. Rev. B 89, 075101 (2014).

Sikora, O., Chang, H.-W., Chou, C.-P., Pollmann, F. & Kao, Y.-J. Variational monte carlo simulations using tensor-product projected states. Phys. Rev. B 91, 165113 (2015).

Corboz, P., Orús, R., Bauer, B. & Vidal, G. Simulation of strongly correlated fermions in two spatial dimensions with fermionic projected entangled-pair states. Phys. Rev. B 81, 165104 (2010).

Evertz, H. G. The loop algorithm. Adv. Phys. 52, 1–66 (2003).

Dai, Z., Wu, Y., Wang, T. & Zaletel, M. P. Fermionic isometric tensor network states in two dimensions (2022).

Giamarchi, T. Quantum Physics in One Dimension. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198525004.001.0001 (Oxford University Press, 2003).

Jördens, R., Strohmaier, N., Günter, K., Moritz, H. & Esslinger, T. A mott insulator of fermionic atoms in an optical lattice. Nature 455, 204–207 (2008).

Fratini, S. & Merino, J. Unconventional metallic conduction in two-dimensional hubbard-wigner lattices. Phys. Rev. B 80, 165110 (2009).

Greiner, M., Mandel, O., Esslinger, T., Haensch, T. & Bloch, I. Quantum phase transition from a superfluid to a mott insulator in a gas of ultracold atoms. Nature 415, 39–44 (2002).

Driscoll, K. Long-range Coulomb interactions and charge frustration in strongly correlated quantum matter. 2022GRALY003 https://hal.science/tel-03626120 (2022).

Mocanu, C. Bosonization of dimerized spinless-fermion and hubbard chains. arXiv:cond-mat/0505238 [cond-mat.str-el] https://arxiv.org/abs/cond-mat/0505238 (2005).

Dang, L., Boninsegni, M. & Pollet, L. Vacancy supersolid of hard-core bosons on the square lattice. Phys. Rev. B 78, 132512 (2008).

Virtanen, P. et al. Scipy 1.0: Fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in python. Nat. Methods 17, 261–272 (2020).

Khanikaev, A. B., Baryshev, A. V., Inoue, M., Granovsky, A. B. & Vinogradov, A. P. Two-dimensional magnetophotonic crystal: Exactly solvable model. Phys. Rev. B 72, 035123 (2005).

Chen, K.-T. & Chiu, Y.-J. Spinless fermions with repulsive interactions. https://web.mit.edu/8.334/www/grades/projects/projects10/Chen+Chiu.pdf (2010).

Mila, F. Exact result on the mott transition in a two-dimensional model of strongly correlated electrons. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14047–14049 (1994).

Wu, D. et al. Variational benchmarks for quantum many-body problems. Science 386, 296–301 (2024).

Cohen, T. S. & Welling, M. Group equivariant convolutional networks (2016).

Roth, C. & MacDonald, A. H. Group convolutional neural networks improve quantum state accuracy (2021).

Roth, C., Szabó, A. & MacDonald, A. High-accuracy variational monte carlo for frustrated magnets with deep neural networks. 108, 054410 (2023).

Pei, M. Y. & Clark, S. R. Compact neural-network quantum state representations of jastrow and stabilizer states. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 54, 405304 (2021).

Pfau, D., Axelrod, S., Sutterud, H., von Glehn, I. & Spencer, J. S. Natural quantum monte carlo computation of excited states (2023).

Carleo, G. et al. NetKet: A machine learning toolkit for many-body quantum systems. SoftwareX 10, 100311 (2019).

Vicentini, F. et al. NetKet 3: Machine Learning Toolbox for Many-Body Quantum Systems. SciPost Phys. Codebases 7, https://scipost.org/10.21468/SciPostPhysCodeb.7 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dian Wu and Javier Robledo Moreno for engaging discussions. We especially thank Javier Robledo Moreno for sharing the data of ref. 22. We express our gratitude to Yusuke Nomura for providing valuable insights regarding quantum phase transitions and their connection to the structure of excitations. This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation under Grant No. 200021_200336, and Microsoft Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.R. developed the code and performed the calculations. J.N. and G.C. supervised the project and provided guidance. All three authors contributed to analyzing the results and writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Romero, I., Nys, J. & Carleo, G. Spectroscopy of two-dimensional interacting lattice electrons using symmetry-aware neural backflow transformations. Commun Phys 8, 46 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-01955-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-01955-z