Abstract

Recently discovered high-Tc superconductivity in pressurized bilayer nickelate La3Ni2O7(La-327)is likely driven by the non-phononic repulsive interaction. Depending on the interlayer repulsion strength, the superconducting gap structure is expected to be either d-wave or sign-changing bonding-antibonding s±-wave. Unfortunately, conventional spectroscopic probes of the gap structure are impractical due to the high-pressure requirement. We propose studying the effect of point-like non-magnetic impurities to distinguish these symmetries, which can be achieved by electron irradiation before applying pressure. Here, we theoretically predict conventional suppression for d-wave superconductivity, whereas the suppression for the interlayer s± -wave state depends subtly on the asymmetry of bonding and antibonding subspaces. For the predicted electronic structure of La-327, the s± -wave is more robust, with Tc showing a convex-to-concave transition, indicating a crossover to s++-wave symmetry as impurity concentration increases. We further analyze the sensitivity of these findings to potential electronic structure modifications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

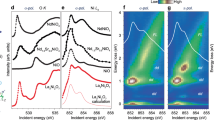

The discovery of high-temperature superconductivity in pressurized La3Ni2O7 (La-327)1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 and La2PrNi2O79, is remarkable not only because of the observed high superconducting transition temperature of about Tc ~ 80 K but also due to the peculiar electronic structure of this bilayer Ruddelsden-Popper (RP) perovskite, which is different from that of hole-doped thin films of superconducting infinite-layer and reduced multilayer nickelates10,11,12.Very recently, signatures of superconductivity with Tc up to 48 K were also detected in thin films of La3−xPrxNi2O7 (x = 0, 0.15, 1) on a compressive strain mediating SrLaAlO4(001) substrate13,14,15,16. Considering La-327 as RP bilayer systems yields a formal Ni 3d7.5 (or 3d8 when considering ligand-hole physics17) electronic configuration with both Ni-eg orbitals crossing the Fermi level. The low-energy physics in this system is governed by the multiorbital and bilayer effects with strong hybridization between the Ni-\({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) and the apical O-pz orbitals18. The multiorbital structure seems to be also one of the key differences between La-327 and the bilayer cuprate superconductors where Cu2+ ions with 3d9 configuration possess only one valence hole in the \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbital, whereas the Ni ion has unpaired valence electrons (holes) in both the \(3{d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) and \(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbitals. Various Hubbard-Hund-type or t −J -like models have already been proposed to capture the superconducting and normal state properties of this multiorbital system17,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34.

Within the variety of model considerations, one of the most interesting theoretical questions concerns the interplay between the intralayer and the interlayer Cooper pairing35, which yields a competition between the s±-wave symmetry of the superconducting order parameter, driven mostly by the interlayer interaction17,19,20,21,22,23,34,36,37,38,39,40,41 and the \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-wave or the dxy-wave symmetries of the superconducting order parameters, driven mostly by the intralayer interaction, respectively17,19,30,39,42.

The bilayer structure of the La-327 allows to separate the electronic states into bonding and antibonding combinations with respect to the layer index. The strong interlayer hybridization (hopping) mediates particularly strong splitting of the bonding and antibonding \(3{d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbitals. While the latter is above the Fermi level, the former forms a flat band (frequently denoted as γ band). Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) at low temperatures sees that band slightly below the Fermi level at ambient pressure43,44. It has been argued that the γ-band crosses the Fermi energy at the high-pressure phase, as supported by a clear drop of the Hall coefficient indicating an increase of hole carrier density3,45. The hybridization of the \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-orbitals between the two layers is somewhat smaller due to their in-plane character and also vanishes along the diagonal of the Brillouin-Zone making bonding-antibonding \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-mostly bands degenerate along this direction19.

Due to the flatness of the γ-band, many theory works pointed out its potential importance for superconductivity irrespective of the type of dominant superconducting instability17,19,20,21,22,23,34,36,37,38,39,40,41. Whether the system chooses s±-wave or d-wave symmetry of the superconducting order parameter depends more on the relative strength of the interlayer versus intralayer antiferromagnetic spin fluctuations46 yet the presence of the γ-band may affect this competition.

The current experimental challenge for studying the high-temperature superconductivity under pressure is to have a reliable experimental probe, which would allow to distinguish between the d-wave and unconventional s±-wave symmetries in bilayer nickelates. Unfortunately, conventional spectroscopic techniques are hard to use under high pressures although they could provide reliable hints if one for example studies impurity-induced bound states47, frequency-dependent spin susceptibility46, or Andreev reflections48. At the same time, multiband d-wave and unconventional s±-wave symmetries are expected to react differently to the non-magnetic point-like impurity scattering, which was investigated previously in detail in iron-based superconductors49,50,51. The latter can be achieved by irradiating high-energy light particles (such as electrons, neutrons, or protons) to the samples52, before the application of pressure.

One should note, however, that the sublattice character of the electronic states introduces further caveat as it restricts the possible scatterings due to impurities, making them sometimes only weakly pair-breaking for spin-singlet superconducting phases. For example, it was recently shown to be the case for the Kagome lattice53. For the bilayer system, one has to separately average over impurities in each layer of a bilayer sandwich, which results in an averaging over bonding and antibonding subspaces as was first noted in ref. 54 for a constant and positive gap functions for bonding and antibonding bands. This naturally raises the question on the role of sublattice degrees of freedom in bilayer systems such as La-327 with potential interlayer s±-wave.

In this manuscript, we analyze the Tc suppression in superconducting La-327 due to point-like non-magnetic impurities focusing on the proposed interlayer constant s±-wave Cooper-pairing versus a \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) (or dxy)-wave Cooper pairings scenarios. We first consider a simple cuprate-like bilayer model with one bonding and one antibonding band of 3\({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-orbital character and derive compact analytic expressions for the bonding and antibonding superconducting gap functions, renormalized by impurity scattering. For the half-filled case, both s±- and d-wave superconducting states are equally suppressed due to impurities following the Abrikosov-Gor’kov (AG) pair-breaking behavior55. The deviation from half-filling reduces Tc suppression for the s±-wave case allowing it to distinguish from the d-wave case. In particular, the Tc suppression is of AG-behavior if bonding and antibonding bands similarly contribute at the Fermi surface and decreases if one or the other dominates at the Fermi surface. This decrease happens because impurities first induce an intralayer s-wave component and upon further increase of the impurity concentration enforce a s± → s++ transition of the gap structure, changing the Tc/Tc0 curve from a concave to a convex shape. Therefore, well away from half-filling Tc decreases but may remain finite for the bonding-antibonding s-wave case and the saturation of the Tc indicates a transition from the s±-wave to s++-wave superconductivity. We then analyze the Tc behavior in the bilayer model of pressurized La-327 and show that d-wave and s±-wave symmetry scenarios can be clearly separated by studying the evolution of Tc as a function of point-like disorder concentrations. Furthermore, for the s±-wave case, we argue that the electronic structure modification of the normal state also affects the suppression rate and the crossover concentration at which s±-wave state transforms into s++-wave superconducting state. For example, the presence of the γ-band near the Fermi level enhances the asymmetry of the bonding-antibonding subspaces of the low-energy electronic structure and makes the s±-wave state more robust against adding non-magnetic impurities.

Results

Disordered bilayer model

We consider a bilayer Hamiltonian with point-like non-magnetic impurities \({{{\mathcal{H}}}}={{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{0}+{{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{{{{\rm{int}}}}}+{{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{{{{\rm{dis}}}}}\), where the interaction term gives rise to an instability towards unconventional s±- or d-wave superconductivity, respectively. The non-interacting part is given by

where \({c}_{l,o}^{{{\dagger}} }({{{\bf{k}}}})\) creates an electron in layer l and orbital o with momentum k. In the clean case, there is reflection symmetry between the two layers of a bilayer sandwich, such that the non-interacting Hamiltonian can be written in terms of intra-layer \({\hat{H}}_{0}^{\parallel }\) and interlayer blocks \({\hat{H}}_{0}^{\perp }\)

where the hats refer to the matrices in orbital space. In the following, we drop explicit momentum and frequency dependence and exchange subscripts and superscripts whenever it is convenient for readability. The bilayer phase factors \({e}^{\pm i{k}_{z}d}\) arise from the Fourier transform for a bilayer sandwich with thickness d. The presence of reflection symmetry between the two layers allows to make a transformation into bonding-antibonding space (ba-space).In particular, assuming negligible interbilayer hopping, the non-interacting Hamiltonian is diagonalized by the simple unitary transformations

Here, the bilayer phase factors have been factored out and are no longer present in the ba-space. Within this framework, we thus have a two-dimensional non-interacting Hamiltonian in the ba-space. One should mention, however, that the kz dependence is implicitly included as the physical observables like charge and spin response functions can be classified into even and odd ones with respect to the kz dependence, see for example, ref. 46 for further details.

We next introduce superconductivity on a mean-field level. After applying mean-field approximation, the interaction part reads

and we can again introduce the ba-block structure

which is again diagonalized using the ba-transformation \(\hat{V}\). Therefore, the superconducting gaps are also two-dimensional in ba-space and given by \({\hat{\Delta }}^{{{{\rm{b/a}}}}}={\hat{\Delta }}^{\parallel }\pm {\hat{\Delta }}^{\perp }\).

To simulate the effect of the electron irradiation, we consider randomly distributed point-like impurities at Ni positions in both NiO2 layers. Such impurities locally break the reflection symmetry and consequently mix bonding and antibonding blocks. Impurity averaging will re-introduce the ba-block structure, but one has to be careful to perform the averaging in both layers separately54. The impurity matrices for the upper and lower layers read

where \({\hat{\tau }}_{i}\) denotes the ith Pauli matrix in the Gor’kov-Nambu space. We consider the self-energy arising due to impurity scattering in the non-crossing approximation and assume the same impurity concentration in both layers. For simplicity, we focus on the intraorbital scattering, which preserves C4 symmetry, i.e. \({\hat{W}}_{{{{\bf{k}}}}o,{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{{\prime} }{o}^{{\prime} }}=W\hat{{\mathbb{1}}}\). After impurity averaging, we obtain the self-energy in the form

Importantly, the above expression corresponds to an averaging over bonding and antibonding blocks. To see this, the relation \(2{\hat{G}}_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{\parallel }={\hat{G}}_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{b}+{\hat{G}}_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{a}\) for the Green’s functions can be inserted, which can again be shown by applying the ba-transformation. This ba-averaging is the direct consequence of the local breaking of reflection symmetry. Note that an impurity matrix of the form \({\hat{W}}_{1}+{\hat{W}}_{2}\) is not creating such an averaging54. The Green’s functions are self-consistently calculated via

Note, the self-energy is unity in the layer space and, therefore, transforms trivially to ba-space, which results from impurity averaging restoring the global reflection symmetry.

Single-orbital model

To study the effect of the averaging over ba-space on the Tc-suppression, it is instructive to consider first a simple bilayer model with only one orbital, considered e.g. in ref. 56. To be specific, we employ a t − J- like bilayer model with in-plane nearest neighbor hopping t and interlayer hopping t⊥

Similarly, we consider the superexchange in-plane interaction J and inter-layer interaction J⊥

The summation brackets 〈i, j〉 indicate summation over nearest neighbors only and r is the layer index. Unless stated otherwise, we assume \({J}_{\perp }={({t}_{\perp }/t)}^{2}J\), which is the expected relation once the t − J model is derived from a Hubbard-type model in the strong-coupling limit. The non-interacting parts yields ba-dispersions \({\epsilon }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{{{{\rm{b/a}}}}}=-2t(\cos ({k}_{x})+\cos ({k}_{y}))\pm {t}_{\perp }-\mu\). We perform a mean-field decoupling from which we obtain the following gap equations (neglecting possible in-plane triplet part)57:

with \({\gamma }_{{{{\rm{d/s}}}}}=(\cos ({k}_{x})\mp \cos ({k}_{y}))/2\) and Δb/a = γsΔs + γdΔd ± Δ⊥ and V = − 3J and V⊥ = − (3/8)J⊥. Here, Δs/d denotes the in-plane extended s-wave and \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-wave gap functions, respectively, whereas Δ⊥ is the interlayer s-wave gap and in the case of opposite signs between bonding and antibonding bands refers to the bonding-antibonding s±-wave solution. The dxy-wave solution would have a \(\sin {k}_{x}\sin {k}_{y}\) functional form in the plane. We do not consider it specifically as it behaves similarly to the \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}-\) wave solution in the presence of non-magnetic point-like impurities. In addition, the \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}-\) wave solution can also have an interlayer component \(\pm {\Delta }_{\perp }^{{{{\rm{d}}}}}{\gamma }_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}\) and yield either in-phase or out-of-phase locking between two neighboring planes. At the same time, its magnitude is expected to be much smaller than that in the s-wave case, since the d-wave solution is only dominant for the smaller values of the interlayer hopping. For simplicity, we assume it to be small and consider the in-phase locking of the d-wave solution between the layers.

In the clean case, the \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-wave solution for the given model is found at half-filling for t⊥ ≲ 1.1t. For larger t⊥, the interlayer ba-s± solution becomes dominant at half-filling. Importantly, as Δs and Δ⊥ correspond to gap structures of A1g symmetry, they always occur simultaneously. In the following, we will focus on the pure interlayer ba-s± solution, and the mixed solution is discussed in Supplementary Note 1. In this one-orbital model, the bonding and antibonding Green’s functions in Eq. (8) are given by

and the renormalized quantities \(i{\tilde{\omega }}_{n}=i{\omega }_{n}-{\Sigma }_{0}\), \({\tilde{\epsilon }}_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{{{{\rm{b/a}}}}}={\epsilon }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{{{{\rm{b/a}}}}}+{\Sigma }_{3}\) and \({\tilde{\Delta }}_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{{{{\rm{b/a}}}}}={\Delta }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{{{{\rm{b/a}}}}}+{\Sigma }_{1}\) are defined as

Recall, that for the \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-wave gap function, Σ1 vanishes by symmetry in momentum space as can be readily seen from inserting \({\Delta }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{{{{\rm{b/a}}}}}={\gamma }_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}{\Delta }_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}\) in Eq. (16). The interlayer ba-s±-wave solution with Δb/a = ± Δ⊥ has no dependence on momentum k. Eq. (15) describes the renormalization of the chemical potential. It is included for completeness, however, it has almost negligible effect on our numerical calculations. This is expected for the case of a superconducting BCS-like state. Note also that Σ3 vanishes exactly in case of particle-hole symmetry. As we are interested in the evolution of the superconducting transition temperature, Tc, when the superconducting order parameter approaches the limit Δ → 0, we rewrite Eq. (16) as

and obtain two equations \({\tilde{\Delta }}_{{{{\rm{b/a}}}}}={\Delta }_{{{{\rm{b/a}}}}}+{\tilde{\Delta }}_{{{{\rm{b}}}}}{\Omega }_{{{{\rm{b}}}}}+{\tilde{\Delta }}_{{{{\rm{a}}}}}{\Omega }_{{{{\rm{a}}}}}\). A similar set of equations was discussed in the context of iron-based superconductors49,51 with one important difference. In particular, here the inter-band coefficients are not symmetric because in general Ωa ≠ Ωb. Solving for \({\tilde{\Delta }}_{{{{\rm{b/a}}}}}\), we find

and after inserting Δb/a = ± Δ⊥ explicitly, we obtain

As follows from Eq. (19), the Tc suppression for the ba-s±-wave depends on the difference between Ωb and Ωa. For the specific case Ωb = Ωa, we find \({\tilde{\Delta }}_{{{{\rm{b/a}}}}}=\pm {\Delta }_{\perp }\) and this version of the ba-s±-wave solution will be suppressed by potential point-like impurities in the same way as the d-wave superconducting state with Σ1 = 0. However, if there is an imbalance (in this particular case it is particle-hole asymmetry) between bonding and antibonding sub-spaces, there will be deviation from the AG behavior. Moreover, finite Ωb ≠ Ωa induces different magnitudes for the bonding and superconducting gap functions \({\tilde{\Delta }}_{{{{\rm{b/a}}}}}\) as the second term on the r.h.s. of Eq. (19) is of different sign. In particular, for increasing impurity density, Ωb + Ωa approaches unity and \({\tilde{\Delta }}_{{{{\rm{b/a}}}}}\) must change its sign, if Ωa/b > Ωb/a, respectively. Therefore, a s±-wave to s++-wave crossover happens, which already was discussed previously in the context of iron-based superconductors49,51. As Ωb + Ωa approaches unity, one might be worried about a divergence due to the denominator. However, this is of course not the case because of the concurrent suppression of Δ⊥. Note that this can be understood with the renormalized Matsubara frequency \({\tilde{\omega }}_{n}={\omega }_{n}/(1-{\Omega }_{{{{\rm{b}}}}}-{\Omega }_{{{{\rm{a}}}}})\) entering the gap equation Eq. (12). The renormalization of the quasiparticle energies is typically negligible. Note that the numerator in the correction term in Eq. (19) depends linearly on the impurity density. Consequently, the deviation from AG behavior is small for low impurity densities but sizable for higher impurity densities.

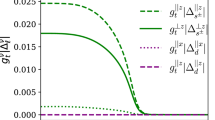

For our simple model, we employ \({\epsilon }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{{{{\rm{b/a}}}}}=-2t(\cos ({k}_{x})+ \cos ({k}_{y}))\pm {t}_{\perp }-\mu\). At half-filling, μ = 0, and the relation \({\epsilon }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{{{{\rm{b}}}}}=-{\epsilon }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}+(\pi ,\pi )}^{{{{\rm{a}}}}}\) guarantees Ωb = Ωa (note that for this case particle-hole symmetry is present). Therefore, moving away from half-filling allows us to tune the particle-hole asymmetry between bonding and antibonding bands and, consequently, between Ωb and Ωa. In Fig. 1 the Tc suppression for exemplary band fillings n = 1, n = 0.75, and n = 0.5 are compared for the pure interlayer ba-s±-wave and \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-wave Cooper-pairing scenarios. Clearly, the qualitative behavior is changing as the imbalance between bonding and antibonding bands increases. At half-filling, both scenarios give the same qualitative AG shape (Fig. 1a). Upon lowering the filling to n = 0.75, the Tc curve for the interlayer s±-wave starts to deviate from AG form close to the critical impurity density at which superconductivity is completely suppressed (Fig. 1(b)). At quarter-filling, n = 0.5, the initial slope is still comparable for both scenarios but the Tc curve for the interlayer ba-s±-wave state changes from convex to concave shape and persists up to more than three times larger impurity densities. We adopt J and t⊥ such that we have roughly the same Tc in the clean state. The results are not sensitive to the variation of t⊥. Fixing t⊥ and varying J and J⊥ independently gives qualitatively identical results as shown in Supplementary Fig. S4. More details on the numerical calculation can be found in the Supplementary Note 4.

The superconducting transition temperature Tc is calculated for different impurity concentrations for bonding-antibonding s±-wave (with bonding/antibonding superconducting order parameter given by Δb/a = ± Δ⊥, where Δ⊥ is the momentum independent interlayer order parameter) and d-wave (\({\Delta }_{{{{\rm{b/a}}}}}={\Delta }_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}(\cos ({k}_{x})- \cos ({k}_{y}))/2\) with Δd denoting the intralayer d-wave order parameter) Cooper-pairings for a bilayer model with single orbital for various band fillings n = 1 (a), n = 0.75 (b), and n = 0.5 (c). The temperature is normalized to the calculated transition temperature of the clean system Tc0. The impurity concentrations are normalized using also the impurity strength W and density of states at the Fermi level N(0). The insets show the corresponding Fermi surface with bonding and antibonding bands as solid blue and dashed red lines, respectively. The imbalance (here it is controlled by the particle-hole asymmetry) between bonding and antibonding bands increases from left to right. The intralayer interaction J and interlayer hopping t⊥ are modified such that Tc0 is roughly the same for all cases.

Multiorbital model of La-327

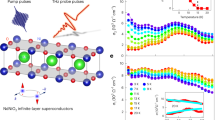

We now turn to the analysis of the Tc suppression in pressurized La-327 based on a two-orbital model Hamiltonian. The non-interacting part is described by the tight-binding parametrization, based on eg-manifold consisting of Ni 3\({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) and 3\({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbitals in each layer, taken from ref. 28, yet another typical tight-binding parametrization with a larger set of hoppings17 would give similar results. Importantly, the interlayer intraorbital hopping between \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbitals is larger than the intralayer intraorbital hopping between \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbitals by a ratio of about 1.3. The corresponding Fermi surface is shown in the inset of Fig. 2(a). In the context of our discussion so far, it is important to note that there is a large particle-hole asymmetry between bonding and antibonding bands as there are two bonding (α and γ) pockets, whereas there is only a single antibonding (β) pocket. While the α and β-bands are due to bonding-antibonding splitting of mostly 3\({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-orbitals, the bonding 3\({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) states give rise to the flattish γ pocket within DFT results1, and the antibonding 3\({d}_{{z}^{2}}\)-states are well above the Fermi level. At the same time, low-temperature ARPES experiments at ambient pressure do not observe the γ pocket, contrary to the DFT prediction43,44. One explanation for this discrepancy is linked to a spin-density-wave (SDW) ordering transition, taking place around TSDW ~ 150 K58 and possibly splitting off the γ-pocket from the Fermi level59. In any case, it leaves the pocket’s fate in the high-pressure phase open to the effect of strong electronic correlation17,24,60. To mimic the effect of an absent γ pocket we modified the onsite energies of the two-orbital model to shift the γ band below EF by about 50 meV keeping the overall band filling unchanged.

a The superconducting transition temperature Tc is calculated for different impurity concentrations nimp for La-32728 for the interlayer s±-wave gap structure determined by the bonding/antibonding superconducting order parameters Δb/a = ± Δ⊥ and intralayer d-wave gap structure (\({\Delta }_{{{{\rm{b/a}}}}}={\Delta }_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}(\cos ({k}_{x})-\cos ({k}_{y}))/2\)). The temperature is normalized to the transition temperature in the clean system Tc0. The impurity concentrations are normalized using also the impurity strength W and density of states at the Fermi level N(0). The intralayer interaction J and interlayer interaction J⊥ are chosen such that Tc ≈ 80 K. In (b) the on-site orbital energies are chosen such that the γ pocket is shifted 50 meV below the Fermi surface as it is the case for the La-327 at ambient pressure43,44, keeping the band filling unchanged. The insets show the corresponding Fermi surface where the solid blue and dashed red lines refer to bonding and antibonding Fermi surface sheets, respectively.

The interactions are included on the level of exchange-like terms, similar to the case of the bilayer t − J like model from ref. 34

and restricted to in-plane nearest neighbor interaction J between \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbitals and the interlayer ones within a bilayer sandwich between \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbitals J⊥34. However, note that the different orbitals are well hybridized, which guarantees strong coupling of the planes also for the \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-orbitals. In particular, the hybridization term between \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) and \({d}_{{z}^{2}}\) orbitals follows the momentum dependence of γd. The consequence is that a \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-wave superconducting gap function with an intraorbital gap \({\Delta }_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}^{{{{\rm{b/a}}}}}\) also induces an interorbital gap \({\Delta }_{\,{\mbox{inter}}\,}^{{{{\rm{b/a}}}}}\) following \({\gamma }_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}^{2}\) (see Fig. S2 for illustration). Hence, one obtains with orbital hybridization a non-vanishing anomalous self-energy Σ1 even for the d-wave case. However, there is no strong deviation from AG-behavior for La-327 as shown in Fig. S1. For the interlayer ba-s±-wave scenario with constant intraorbital \({\Delta }_{{z}^{2}}^{{{{\rm{b/a}}}}}\) the hybridization forces \({\Delta }_{\,{\mbox{inter}}\,}^{{{{\rm{b/a}}}}}\) to follow the form factor γd.

Having several orbitals brings additional complexity and therefore we proceed numerically. In particular, we solve Eq. (7) and Eq. (8) and the superconducting gap equations

self-consistently where \({F}_{i}^{{{{\rm{b/a}}}}}\) denotes the ith intraorbital component of the anomalous ba-Green’s function. To find Tc we solve the gap equations self-consistently upon varying the impurity concentrations until the gap value converges to a value ≤10−5 eV and further restrict the momentum summation to a 100 meV shell around the Fermi level. To keep the tetragonal symmetry we also assume that the impurity scattering is diagonal in the orbital space.

The resulting Tc suppression with the \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\)-wave and interlayer ba-s±-wave solutions are plotted in Fig. 2 with (a) and without (b) the γ-pocket being at the Fermi level. We find that for the electronic structure of La-327 there is a significant difference of the Tc curves, produced by point-like non-magnetic impurities. While d − wave superconductivity is suppressed following more or less the conventional AG pair-breaking behavior, expected for the d − wave superconducting state, and the difference arises due to the multi-orbital character of superconductivity, the bonding-antibonding s±-wave superconducting state deviates strongly. Although Tc is reduced for increasing impurity concentration, its value finally saturates due to s±-wave to s++-wave crossover, and the latter is robust to the non-magnetic impurity scattering. The crossover is visualized in Supplementary Fig. S2.

Furthermore, changing the fermiology of the initial model from having the low-energy regime dominated by the bonding subspace to having a more balanced appearance of both ba-subspace, i.e. without the bonding z-electronic states (γ-pocket) at the Fermi level, shifts the crossover from convex to concave shape of the Tc curve as a function of impurity concentration. To be more precise, we even find a change in dominance from bonding to antibonding subspace near the Fermi level as apparent from the inset in Fig. 2b. Therefore, the s++-wave at higher impurity densities will adopt the sign of the antibonding β band. This implies that for some position of the γ pocket near 50 meV below the Fermi surface, bonding, and antibonding subspaces must be balanced in the low-energy regime. In a small region around this position, the interlayer ba-s-wave and d-wave Tc suppression curves will not be distinguishable. For this rather unlikely case, together with other experimental data providing evidence for the interlayer ba-s-wave, making a precise comparison to the future experimental data would allow us to make indirect conclusions on the fate of the γ-pocket in this case and finally its role for superconductivity in La-327. As soon as the γ pocket is shifted below the Fermi level, the dominant superconducting gap structure changes, making the interlayer ba-s±-wave not the leading solution and it requires much higher interaction J⊥ to stabilize34.

Conclusion

To summarize, we analyze the suppression of unconventional superconductivity in pressurized La-327 by non-magnetic point-like impurities assuming sign-changing bonding-antibonding s±-wave and d-wave symmetries of the superconducting order parameters, currently discussed in the literature. We show that each superconducting order parameter is suppressed in a different fashion. While the suppression of the d-wave superconductivity follows more or less the Abrikosov-Gor’kov characteristic behavior for the unconventional superconducting order, the bonding-antibonding sign-changing s±-wave superconductivity is suppressed differently, depending on the asymmetry of the bonding-antibonding electronic bands. A weak asymmetry of the bonding-antibonding bands with respect to their location at the Fermi level would result in the suppression of the s±-wave superconducting state similar to the d-wave case. Away from this high-symmetry point of the bilayer model, s±-wave superconductivity is more robust against non-magnetic impurity scattering and the Tc curve experiences a crossover from convex to concave shape, which signals the corresponding evolution from s±-wave to s++-wave superconductivity. This characteristic behavior makes it an indicative test for experimental verification by studying Tc evolution as a function of electron irradiation. Furthermore, the robustness of superconductivity in the s±-wave case also depends on the bonding-antibonding band structure asymmetry with respect to the Fermi level of the normal state model and could be used to elucidate the role of the γ-pocket in the pressurized La-327 samples. Another interesting test would be to study the change of the slope of the upper critical field under the effect of electron irradiation like it was proposed for the iron-based superconductors61.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this article are openly available at https://doi.org/10.60517/5d86p042m.

Code availability

The code written for MATLAB software62 is openly available at https://doi.org/10.60517/5d86p042m.

References

Sun, H. et al. Signatures of superconductivity near 80 K in a nickelate under high pressure. Nature 621, 493 (2023).

Hou, J. et al. Emergence of high-temperature superconducting phase in pressurized La3Ni2O7 crystals. Chin. Phys. Lett. 40, 117302 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. High-temperature superconductivity with zero resistance and strange-metal behaviour in La3Ni2O7−δ. Nat. Phys. 20, 1269 (2024).

Zhou, Y. et al. Investigations of key issues on the reproducibility of high-tc superconductivity emerging from compressed La3Ni2O7. Matter Radiat. Extremes 10, 027801 (2025).

Zhang, M. et al. Effects of pressure and doping on Ruddlesden-Popper phases Lan+1NinO3n+1. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 185, 147 (2024).

Wang, L. et al. Structure responsible for the superconducting state in la3ni2o7 at high-pressure and low-temperature conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 7506 (2024).

Wang, G. et al. Pressure-induced superconductivity in polycrystalline La3Ni2O7−δ. Phys. Rev. X 14, 011040 (2024).

Dong, Z. et al. Visualization of oxygen vacancies and self-doped ligand holes in la3ni2o7- δ. Nature 630, 847 (2024).

Wang, N. et al. Bulk high-temperature superconductivity in pressurized tetragonal La2PrNi2O7. Nature 634, 579 (2024).

Li, D. et al. Superconductivity in an infinite-layer nickelate. Nature 572, 624–627 (2019).

Pan, G. A. et al. Superconductivity in a quintuple-layer square-planar nickelate. Nat. Mater. 21, 160–164 (2021).

Osada, M. et al. A superconducting praseodymium nickelate with infinite layer structure. Nano Lett. 20, 5735–5740 (2020).

Ko, E. K. et al. Signatures of ambient pressure superconductivity in thin film La3Ni2O7. Nature 638, 935–940 (2025).

Zhou, G. et al. Ambient-pressure superconductivity onset above 40 k in bilayer nickelate ultrathin films. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.16622 (2024).

Bhatt, L. et al. Resolving structural origins for superconductivity in strain-engineered La3Ni2O7 thin films (2025), arXiv:2501.08204 [cond-mat.supr-con].

Liu, Y. et al. Superconductivity and normal-state transport in compressively strained La2PrNi2O7 thin films (2025), arXiv:2501.08022 [cond-mat.supr-con].

Lechermann, F., Gondolf, J., Bötzel, S. & Eremin, I. M. Electronic correlations and superconducting instability in La3Ni2O7 under high pressure. Phys. Rev. B 108, L201121 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Lin, L.-F., Moreo, A. & Dagotto, E. Electronic structure, dimer physics, orbital-selective behavior, and magnetic tendencies in the bilayer nickelate superconductor La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Phys. Rev. B 108, L180510 (2023).

Xia, C., Liu, H., Zhou, S. & Chen, H. Sensitive dependence of pairing symmetry on ni-eg crystal field splitting in the nickelate superconductor La3Ni2O7. Nat. Commun. 16, 1054 (2025).

Qin, Q. & Yang, Y.-f High-Tc superconductivity by mobilizing local spin singlets and possible route to higher Tc in pressurized La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 108, L140504 (2023).

Huang, J., Wang, Z. & Zhou, T. Impurity and vortex states in the bilayer high-temperature superconductor La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 108, 174501 (2023).

Oh, H. & Zhang, Y.-H. Type-II t−J model and shared superexchange coupling from Hund’s rule in superconducting La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 108, 174511 (2023).

Qu, X.-Z. et al. Bilayer t-J-J⊥ model and magnetically mediated pairing in the pressurized nickelate La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 036502 (2024).

Ryee, S., Witt, N. & Wehling, T. O. Quenched pair breaking by interlayer correlations as a key to superconductivity in La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 096002 (2024).

Tian, Y.-H., Chen, Y., Wang, J.-M., He, R.-Q. & Lu, Z.-Y. Correlation effects and concomitant two-orbital s±-wave superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 under high pressure. Phys. Rev. B 109, 165154 (2024).

Liao, Z. et al. Electron correlations and superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 under pressure tuning. Phys. Rev. B 108, 214522 (2023).

Kaneko, T., Sakakibara, H., Ochi, M. & Kuroki, K. Pair correlations in the two-orbital Hubbard ladder: Implications for superconductivity in the bilayer nickelate La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 109, 045154 (2024).

Luo, Z., Hu, X., Wang, M., Wú, W. & Yao, D.-X. Bilayer two-orbital model of La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 126001 (2023).

Chen, J., Yang, F. & Li, W. Orbital-selective superconductivity in the pressurized bilayer nickelate La3Ni2O7: An infinite projected entangled-pair state study. Phys. Rev. B 110, L041111 (2024).

Jiang, K., Wang, Z. & Zhang, F.-C. High temperature superconductivity in La3Ni2O7. Chin. Phys. Lett. 41, 017402 (2024).

Shen, Y., Qin, M. & Zhang, G.-M. Effective bi-layer model hamiltonian and density-matrix renormalization group study for the high-tc superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 under high pressure. Chin. Phys. Lett. 40, 127401 (2023).

Yang, Y.-f, Zhang, G.-M. & Zhang, F.-C. Interlayer valence bonds and two-component theory for high-Tc superconductivity of La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Phys. Rev. B 108, L201108 (2023).

Wú, W., Luo, Z., Yao, D.-X. & Wang, M. Superexchange and charge transfer in the nickelate superconductor La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 67, 117402 (2024).

Luo, Z., Lv, B., Wang, M., Wú, W. & Yao, D.-X. High-Tc superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 based on the bilayer two-orbital t-J model. npj Quantum Mater. 9, 61 (2024).

Dagotto, E., Riera, J. & Scalapino, D. Superconductivity in ladders and coupled planes. Phys. Rev. B 45, 5744 (1992).

Zhang, Y., Lin, L.-F., Moreo, A., Maier, T. A. & Dagotto, E. Trends in electronic structures and s±-wave pairing for the rare-earth series in bilayer nickelate superconductor R3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 108, 165141 (2023).

Yang, Q.-G., Wang, D. & Wang, Q.-H. Possible s±-wave superconductivity in La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 108, L140505 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Lin, L.-F., Moreo, A., Maier, T. A. & Dagotto, E. Structural phase transition, s±-wave pairing, and magnetic stripe order in bilayered superconductor La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Nat. Commun. 15, 2470 (2024).

Heier, G., Park, K. & Savrasov, S. Y. Competing dxy and s± pairing symmetries in superconducting La3Ni2O7:LDA+FLEX calculations. Phys. Rev. B 109, 104508 (2024).

Yang, H., Oh, H. & Zhang, Y.-H. Strong pairing from a small Fermi surface beyond weak coupling: Application to La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 110, 104517 (2024).

Sakakibara, H., Kitamine, N., Ochi, M. & Kuroki, K. Possible high Tc superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 under high pressure through manifestation of a nearly half-filled bilayer Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 106002 (2024).

Lu, C., Pan, Z., Yang, F. & Wu, C. Interlayer-coupling-driven high-temperature superconductivity in La3Ni2O7 under pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 146002 (2024).

Yang, J. et al. Orbital-dependent electron correlation in double-layer nickelate La3Ni2O7. Nat. Commun. 15, 4373 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Electronic correlation and pseudogap-like behavior of high-temperature superconductor La3Ni2O7. Chin. Phys. Lett. 41, 087402 (2024).

Zhou, Y. et al. Investigations of key issues on the reproducibility of high-Tc superconductivity emerging from compressed La3Ni2O7, Matter and Radiation at Extremes 10, 027801 (2025)

Bötzel, S., Lechermann, F., Gondolf, J. & Eremin, I. M. Theory of magnetic excitations in the multilayer nickelate superconductor La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 109, L180502 (2024).

Huang, J., Wang, Z. D. & Zhou, T. Impurity and vortex states in the bilayer high-temperature superconductor La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. B 108, 174501 (2023).

Yang, Y.-F. Possible fano effect and suppression of Andreev reflection in La3Ni2O7. Chin. Phys. Lett. 42, 017301 (2025).

Efremov, D. V., Korshunov, M. M., Dolgov, O. V., Golubov, A. A. & Hirschfeld, P. J. Disorder-induced transition between s± and s++ states in two-band superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 84, 180512 (2011).

Hirschfeld, P. J. Using gap symmetry and structure to reveal the pairing mechanism in Fe-based superconductors. Comptes Rendus. Phys. 17, 197–231 (2015).

Korshunov, M. M., Togushova, Y. N. & Dolgov, O. V. Impurities in multiband superconductors. Phys.-Uspekhi 59, 1211–1240 (2016).

Mizukami, Y. et al. Disorder-induced topological change of the superconducting gap structure in iron pnictides. Nat. Commun. 5, 5657 (2014).

Holbæk, S. C., Christensen, M. H., Kreisel, A. & Andersen, B. M. Unconventional superconductivity protected from disorder on the kagome lattice. Phys. Rev. B 108, 144508 (2023).

Hofmann, U., Keller, J. & Kulić, M. Interlayer pairing in high temperature superconductors: effect of nonmagnetic impurities. Z. f.ür. Phys. B Condens. Matter 81, 25–32 (1990).

Abrikosov, A. & Gor’Kov, L. Zh. é ksp. teor. fiz. 39, 1781 1960 sov. phys. JETP 12, 1243 (1961).

Maier, T. A. & Scalapino, D. J. Pair structure and the pairing interaction in a bilayer Hubbard model for unconventional superconductivity. Phys. Rev. B 84, https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.84.180513 (2011).

Coleman, P., Introduction to many-body physics. (Cambridge University Press, 2015) Chap. 15.

Chen, K. et al. Evidence of spin density waves in La3Ni2O7−δ. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 256503 (2024).

Lechermann, F., Bötzel, S. & Eremin, I. M. Electronic instability, layer selectivity, and Fermi arcs in La3Ni2O7. Phys. Rev. Mater. 8, 074802 (2024).

Wang, Y., Jiang, K., Wang, Z., Zhang, F.-C. & Hu, J. Electronic and magnetic structures of bilayer La3Ni2O7 at ambient pressure. Phys. Rev. B 110, 205122 (2024).

Kogan, V. G. & Prozorov, R. Disorder-dependent slopes of the upper critical field in nodal and nodeless superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 108, 064502 (2023).

T. M. Inc. Matlab version: 9.14.0 (r2023a) (2023).

Acknowledgements

The work is supported by the German Research Foundation within the bilateral NSFC-DFG Project ER 463/14-1, and by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) (No. JP22H00105) from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.S. and I.M.E. conceived the project. S.B. performed the analytical and numerical calculations and the corresponding analysis with I.M.E. and F.L. supervising the research. All authors wrote and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks Thomas Maier and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bötzel, S., Lechermann, F., Shibauchi, T. et al. Theory of potential impurity scattering in pressurized superconducting La3Ni2O7. Commun Phys 8, 154 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02056-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02056-7