Abstract

Bacterial suspensions and other active fluids are known to develop highly dynamical vortex states, denoted as active or mesoscale turbulence. We reveal the pronounced effect of non-Newtonian rheological conditions on these turbulent states, concentrating on shear thinning. A self-sustained heterogeneous state of coexisting turbulent and quiescent areas develops, which results in anomalous velocity statistics. The heterogeneous state emerges in a hysteretic transition when varying activity. We provide an extensive numerical analysis and observe features consistent with a directed percolation transition. Our results are important, for instance, when addressing active objects in biological media with complex rheological properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bacterial suspensions are a paradigmatic example of active matter1,2,3. Due to the constant energy input on the scale of bacterial microswimmers, such suspensions exhibit various kinds of spatiotemporal dynamics4. These include biofilm formation5 as well as collective motion and swarming states6,7, which enable the rapid expansion to new territories. In particular, swimming bacteria display swirling and vortex patterns8,9,10,11, which have been denoted as active or mesoscale turbulence11,12. In contrast to inertial turbulence, these states exhibit a characteristic vortex size. observed, for example, in suspensions of Bacillus subtilis8,11,13. The key features are captured by continuum-theoretical descriptions11,14,15,16 in terms of the velocity field.

Both the propulsion mechanism and the interactions between microswimmers are mediated by the solvent medium. In general, the environments inhabited by bacteria and other biological microswimmers often display non-Newtonian and viscoelastic properties17. Examples include spermatozoa in the reproductive tract18 and pathogenic bacteria in gastric mucus or other extracellular fluids19. Predominantly, blood shows shear thinning and can display complex rheological properties such as viscoelasticity and thixotropy20. During biofilm formation, bacteria excrete extracellular polymeric substances5,21, likewise resulting in non-Newtonian rheology22.

The development of realistic models for collective motion of microswimmers thus necessitates to include non-Newtonian effects. So far, complex solvents have mostly been investigated in the case of single-swimmer dynamics, for instance, exploring the impact of viscoelasticity and shear thinning or thickening on the swimming speed23,24,25. These studies show that, depending on various parameters such as swimmer geometry and fluid properties, complex rheology can enhance or hinder self-propulsion26,27. It allows for reciprocal deformations of the swimmers to achieve propulsion28,29,30,31, in contrast to Newtonian fluids featuring time-reversible Stokes flow32,33.

So far, only a limited number of studies explore the impact of complex rheological properties on the collective motion of microswimmers. Here, the focus has generally been on viscoelastic fluids. Diverse spatiotemporal pattern formation is observed, which results in enhanced complexity or calming effects depending on the elastic parameters34,35,36,37,38,39. Recent studies have further demonstrated that complex rheological properties such as shear thickening40 and viscoelasticity41 can be utilized to control emergent states. However, in experiments bacterial suspensions often display shear thinning due to the presence of extracellular polymers22. The impact of such shear-thinning rheological conditions on active turbulence are still to be explored.

We address this open question through a recent continuum theory15,42,43 that shows turbulent dynamics consistent with experimental observations on both bacterial microswimmers and ATP-driven microtubular networks43. Its versatility, besides characterizing pure active turbulence, has been demonstrated, for example, by extensions for shear-thickening active suspensions40. We now provide the missing and significantly more abundant case of mesoscale turbulence in shear-thinning suspensions. That is, viscosity locally decreases with increasing local shear rate. We explore the resulting patterns of mesoscale turbulence and find, as a key observation, that shear thinning leads to hysteretic behavior of the turbulent state when varying the activity. More precisely, a regime of coexisting patterns of turbulence and macroscopically quiescent patches (vanishing collective velocity) emerges through shear thinning. Anomalous velocity statistics are found in this regime. Thus, we uncover a self-sustained dynamic state of heterogeneity combining regions of turbulence with nonturbulent patches.

Results

Mesoscale turbulence

To quantify the given situation, we consider a recent continuum theory15,40,42,43 that describes the dynamics of the overall (collective) velocity field v(x, t) of the entire incompressible suspension via a generalized Navier–Stokes equation,

Here, the constant density ρ is absorbed into the pressure and stress tensor, \(\tilde{p}=p/\rho\) and \(\tilde{{{\boldsymbol{\sigma }}}}={{\boldsymbol{\sigma }}}/\rho\). The stress tensor is expanded in gradients of the deformation rate tensor Σ = [(∇ v) + (∇v)⊤]/2,

where ⊤ marks the transpose15,40,42,43. Key features are the emergence of highly dynamic vortex patterns and the selection of a specific length scale of the vortex size. In the context of microswimmer suspensions, the resulting state is usually denoted as mesoscale turbulence11.

For Γ2 = Γ4 = 0, the theory reduces to the familiar case of vanishing activity. Then, Γ0 corresponds to the kinematic viscosity ν. We adopt the relation Γ0 = ν for the active case. The coefficient Γ4 must be positive to ensure stability at short wavelengths. Activity of the swimmers increases the coefficient Γ2, which excites patterns of intermediate wavelengths once \({\Gamma }_{2} > \sqrt{4\nu {\Gamma }_{4}}\). A linear stability analysis reveals a critical finite wavenumber \({k}_{{{\rm{c}}}}=\sqrt{{\Gamma }_{2}/2{\Gamma }_{4}}\). The resulting band of unstable modes indicates wavenumbers at which energy is pumped into the system as a result of the intrinsic activity of the microswimmers. Subsequently, nonlinear advection, represented by v ⋅ ∇ v in Eq. (1), is responsible for the development of turbulence and associated energy transport between wavenumbers. The resulting balance between energy input and dissipation leads to a statistically stationary state15,40,42,43.

For further details of the theoretical description, we refer to Supplementary Note 1. There, we also point out important differences to the Toner–Tu44 and Toner–Tu–Swift–Hohenberg equations11,12,16. The latter represent a related framework to model mesoscale turbulence. Compared to those, the here-employed description is formulated in terms of the overall velocity of the suspension instead of the velocity of only the microswimmers. Consequently, incorporating non-Newtonian rheology is straightforward.

To investigate how the interplay of non-Newtonian rheology and active energy input impacts the emerging dynamic structures, we now turn to the abundant case of shear-thinning active suspensions. In a minimal approach, the dependence of the local viscosity ν(x) on the local shear rate \(\dot{\gamma }({{\bf{x}}})\) is described in terms of the frequently considered Cross fluid45,46. Its main feature is a viscosity ν∞ at high shear rate that is smaller than the viscosity ν0 at low shear rate, accompanied by a continuous crossover region in between,

The local shear rate is calculated from the deformation rate tensor via \(\dot{\gamma }({{\bf{x}}})=\sqrt{2{{\boldsymbol{\Sigma }}}({{\bf{x}}}):{{\boldsymbol{\Sigma }}}({{\bf{x}}})}\). While the exponent n quantifies the steepness of the crossover, the reference shear rate \({\dot{\gamma }}_{{{\rm{cr}}}}\) locates this crossover, see the inset of Fig. 1a. In our case, the non-Newtonian properties included in our model are induced by the carrier fluid and thus appear in the continuum description, which represents both microswimmers and solvent by one velocity field. Bacterial suspensions during biofilm formation provide an example of this situation. There, extracellular polymers excreted by the bacteria lead to complex, non-Newtonian rheology of the suspension22.

Hysteresis loops for the degree of mesoscale turbulence as a function of microswimmer activity a for parameters of shear thinning ν0/ν∞ = 1.5, ζ = 2, and different n. For increasing a, the isotropic, macroscopically quiescent state becomes linearly unstable beyond ath. When decreasing a, turbulence persists down to the critical values \({a}_{n}^{* } < {a}_{{{\rm{th}}}}\). a Quantification via the system-averaged enstrophy 〈ω2〉. Inset: considered effect of shear thinning as described by the dependence of the local viscosity ν on the local shear rate \(\dot{\gamma }\) in the framework of the Cross fluid model45,46. b Quantification via the time-averaged area fraction of turbulent patches Φ. Inset: Φ as a function of the distance to the critical value, \(a-{a}_{n}^{* }\), revealing a regime of power-law scaling. Error bars denote the standard error.

We utilize the length \({k}_{{{\rm{c}}}}^{-1}\), the time \({({k}_{{{\rm{c}}}}^{2}{\nu }_{\infty })}^{-1}\), and the speed kcν∞ to rescale Eq. (1),

where \(\nu /{\nu }_{\infty }=1+({\nu }_{0}/{\nu }_{\infty }-1)/\{1+{[\sqrt{2{{\boldsymbol{\Sigma }}}:{{\boldsymbol{\Sigma }}}}/\zeta ]}^{n}\}\). Thus, the parameters characterizing shear thinning are the viscosity ratio ν0/ν∞, the rescaled crossover shear rate \(\zeta ={\dot{\gamma }}_{{{\rm{cr}}}}/({k}_{{{\rm{c}}}}^{2}{\nu }_{\infty })\), and the exponent n. Moreover, \(a={\Gamma }_{2}^{2}/(4{\nu }_{\infty }{\Gamma }_{4})\) sets the strength of the activity of the microswimmers. Finally, v(x, t) quantifies the solvent flow on length scales several times larger than that of individual microswimmers. Thus, the isotropic state v(x, t) = 0 describes macroscopic quiescence. In this state, the swimmers are active on the microscopic scale, but their orientations are disordered, resulting in the absence of collective motion.

A straightforward stability analysis shows that the quiescent state v(x, t) = 0 is linearly stable below a threshold activity ath = ν0/ν∞ (see Methods). Intuitively, viscosity counteracts turbulence. Thus, the active driving has to overcome the hindrance by the viscosity ν0 for turbulent instabilities to set in. Increasing the activity above ath, this state becomes unstable with respect to the growth of turbulent patterns characterized by a band of unstable modes. The fastest-growing mode km is close to the critical mode kc = 1 for values of a close to ath. For a = 0, we recover the familiar Navier–Stokes equation without activity for a shear-thinning Cross fluid.

Emerging heterogeneous patterns

To analyze the emerging patterns that result from this combination of mesoscale turbulence and shear thinning, we solve Eq. (4) numerically for a large two-dimensional system of size 128π × 128π with periodic boundary conditions (see Methods). We start from random initial conditions and set the parameters to ζ = 2 and ν0/ν∞ = 1.5, while varying the activity a. The viscosity ratio is in the range of recent experimental results on bacterial biofilms, where the rheological properties of the extracellular polymer matrix resulted in a viscosity decrease at high shear rates of up to 75% depending on the species22. We begin below the threshold, a < ath, and then increase activity a. Turbulence develops across the whole system once the threshold ath is passed, where the quiescent state becomes linearly unstable, see the vertical black arrow in Fig. 1a. There, the degree of mesoscale turbulence is quantified by the mean enstrophy 〈ω2〉, where we define the vorticity field ω = (∇×v)z .

The case of decreasing activity a features even more interesting behavior. We start above the threshold, a > ath, implying that the macroscopically quiescent state is linearly unstable. Thus, vortex patterns grow across the whole system according to the finite-wavelength instability discussed above. For illustration, Fig. 2a shows a snapshot of the vorticity field at a = 1.55 > ath. When now decreasing the activity a, turbulence persists down to below the threshold value ath. We have not observed such hysteretic behavior for regular Newtonian fluids. The associated hysteresis loops of mesoscale turbulence, quantified by the mean enstrophy 〈ω2〉, are plotted in Fig. 1b for different values of n. To explain this hysteretic behavior, that is, the persistence of existing turbulence when decreasing the activity down to a < ath, we note the following. The actively induced turbulent state is characterized by relatively high local shear rates. Locally, due to shear thinning, these high shear rates significantly reduce viscosity. Reduced viscosity, in turn, favors turbulence. This feedback mechanism thus provides a channel for the self-sustenance of turbulence below the instability threshold ath, resulting in hysteresis.

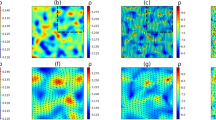

Snapshots of the vorticity field ω (rescaled by its respective maximum value \({\omega }_{\max }\)) for activities (a) a = 1.55 > ath, (b) a = 1.41 < ath, and (c) a = 1.39. Quiescent patches of increasing size develop for decreasing a. d Velocity distribution function \({{\mathcal{P}}}(v)\). Statistics are very close to Gaussian (indicated by the dashed line) for large activity a. Yet, they develop pronounced tails and an elevated maximum for decreasing a. Both axes are normalized using the standard deviation σv. Inset: excess kurtosis β2 as a function of a, quantifying deviations from Gaussian statistics. e, f Snapshots of the locally averaged, coarse-grained viscosity νcg(x) for the same values of a as in (b, c). Remaining parameters are ν0/ν∞ = 1.5, n = 4, ζ = 2, and the size of the snapshots is 64π × 48π.

Decreasing activity further, we observe increasingly heterogeneous states, see the snapshots in Fig. 2b, c. Compared to Fig. 2a, the system now exhibits turbulent regions coexisting with increasingly large quiescent areas devoid of vortices. This emergent heterogeneous state is highly dynamic and the locations of the macroscopically quiescent patches continuously change while the vortex patterns rearrange (see also Supplementary Movie 1).

The development of heterogeneous states of coexistence also significantly changes the velocity statistics \({{\mathcal{P}}}(v)\). Here, v represents an arbitrary component of the velocity field, v = vx or v = vy. Due to macroscopic isotropy, see Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1, either component can be used. In previous studies, employing a similar statistical evaluation11,47,48,49 for the Newtonian case, the velocity statistics were found to be very close to Gaussian in mildly active regimes. Strong activity, however, may lead to anomalous statistics49. In our case, we observe Gaussian behavior in the fully turbulent state for a > ath, see Fig. 2d, suggesting a mildly active regime. However, when decreasing activity below the threshold value ath, the distribution function develops pronounced tails together with a sharper maximum at v = 0. In our situation of shear thinning, these features reflect heterogeneous states of coexisting macroscopically quiescent areas (v ≈ 0) and turbulent regions of elevated local macroscopic velocities.

Since already the turbulent regions themselves are very heterogeneous, we employ a coarse-graining procedure to further quantify the emerging structures. First, we determine the local viscosity from local shear rates via the rescaled version of Eq. (3). Then, across the system, we locally average the viscosity over square regions of a size corresponding to the critical length scale \(2\pi {k}_{c}^{-1}\) (see Methods). Snapshots of the resulting coarse-grained viscosity field νcg(x) are depicted in Figs. 2(e) and (f). To distinguish between turbulent and macroscopically quiescent regions, we introduce a color scheme. If the locally coarse-grained viscosity is large enough to suppress the linear instability and thus turbulence, νcg(x) > ν∗(a) = a ν∞ (see Methods), we employ green color. Contrarily, low-viscosity regions of locally self-sustained turbulence are dyed in purple. In particular, Figs. 2(e) and (f) demonstrate the coexistence of turbulent and macroscopically quiescent regions of comparable area fraction. Further visualizations are provided in Supplementary Fig. 2 and Notes 3 and 4. (Supplementary Movie 1 shows the stable coexistence of rearranging domains at a constant activity, whereas Supplementary Movie 2 shows how the turbulent domains grow when the activity is increased suddenly from a value in the regime of coexistence.)

Critical behavior at the transition to turbulence

To further quantify the transition from fully developed turbulence to macroscopically quiescent states, we determine the time-averaged area fraction of turbulence Φ via the coarse-grained viscosity. We define the fluid at position x as turbulent if νcg(x) < ν∗(a) = a ν∞. Φ acts as an order parameter. Its bounds indicate a macroscopically quiescent state of the entire system (Φ = 0) and fully turbulent ones (Φ = 1). Figure 1b shows Φ as a function of activity a for different values of n. For decreasing a, we observe a clear transition from a fully turbulent to a completely quiescent state. The critical activity \({a}_{n}^{* }\) is determined numerically and marks the point where turbulent patches are finally unable to persist. Here, \({a}_{n}^{* }\) is shifted to smaller activities for larger n, thus extending the region of hysteresis and coexistence.

When we plot Φ as a function of the distance to the critical point \((a-{a}_{n}^{* })\), see the inset of Fig. 1b, we observe power-law behavior \(\Phi \propto {(a-{a}_{n}^{* })}^{{\beta }^{* }}\). We find that the exponent β* does not change when varying the steepness of the shear thinning crossover determined via the parameter n. Fitting the curves in Fig. 1, we obtain β* = 0.352(20), where the number in brackets denotes an error estimate corresponding to a confidence interval of 95%. However, additional simulations, demonstrate that the exponent β* is in fact not universal, see Supplementary Note 5 and Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4. Although independent or only weakly dependent on both ν0/ν∞ and n, it depends on the value of the crossover shear rate ζ.

The power-law scaling indicates that the transition may be linked to a universality class of non-equilibrium phase transitions. Indeed, recent studies50,51,52,53,54 have shown that emergence of turbulence in various systems can be understood as a transition of directed percolation (“DP”). In this analogy, turbulent domains spreading to neighboring regions correspond to the excited state, whereas laminar domains correspond to the absorbing state. Above a certain critical Reynolds number, the turbulent domains may persist in time, thus leading to a percolation transition. The direction of the spreading process of directed percolation therefore corresponds to the time dimension of the driven fluid flow. In addition to driven Couette flows of passive systems52,55,56,57, directed percolation transitions have been found in channel flow53, pipe flow51, turbulent liquid crystals50, as well as active nematics in microchannels54.

Motivated by these studies, we investigate whether the transition between a fully macroscopically quiescent system and patchy self-sustained turbulent states, as observed in our shear-thinning active fluid, exhibits features consistent with directed percolation as well. As discussed, the power-law exponent β*, governing the scaling of the turbulence fraction with \(a-{a}_{n}^{* }\) depends on the magnitude of the crossover shear rate ζ of shear thinning. Directly comparing exponents that govern the scaling in terms of the distance to the critical point with those of the directed percolation universality classes thus seems futile. In fact, there is no a priori reason why the activity a should linearly correspond to the spreading probability, which is the control parameter in directed percolation. Thus, we rather focus our attention on the critical point directly and not on how it is approached.

In directed percolation, the spatial and temporal correlations become scale-free at the critical point58. Accordingly and motivated by previous works50,52,55, we thus focus on the distributions of certain characteristics of the absorbing state, which here is the quiescent state. Specifically, those characteristic parameters are the distances (gap lengths) between turbulent domains, ℓ, and the time intervals (duration) of quiescence between the occurrences of turbulence at fixed spatial positions, τ. We employ the coarse-grained viscosity νcg(x, t) to determine these quantities. For example, the flow field exhibits a quiescent gap of length ℓx in x direction if νcg(x, y, t) < ν∗(a) and νcg(x + ℓx, y, t) < ν∗(a), but \({\nu }_{{{\rm{cg}}}}(x+{\ell }^{{\prime} },y,t) > {\nu }_{* }(a)\) for \(0 < {\ell }^{{\prime} } < {\ell }_{x}\). The gap length ℓy and quiescent time τ are determined analogously.

To obtain the distributions \({{\mathcal{P}}}(\ell )\) and \({{\mathcal{P}}}(\tau )\) at the critical point, we perform additional long-running, large-scale numerical evaluations for the sets of parameters explored so far. Here, we choose values of the activity a as close to the critical value \({a}_{n}^{* }\) as possible. We first determine distributions of gap lengths for the x and y directions separately. As the system exhibits isotropic symmetry in the statistical sense, see Supplementary Note 2, these distributions, \({{\mathcal{P}}}({\ell }_{x})\) and \({{\mathcal{P}}}({\ell }_{y})\), are equal for large enough sample sizes. We thus calculate \({{\mathcal{P}}}(\ell )\) as the average of \({{\mathcal{P}}}({\ell }_{x})\) and \({{\mathcal{P}}}({\ell }_{y})\). The quiescent time distribution, \({{\mathcal{P}}}(\tau )\), can be determined directly.

Figure 3 shows \({{\mathcal{P}}}(\ell )\) and \({{\mathcal{P}}}(\tau )\) for ζ = 2, ν0/ν∞ = 1.5, different values of n, and activities as close to the critical point as possible. Both distributions exhibit power-law scaling for sufficiently large ℓ and τ, implying self-similarity at the critical point. Here, the spatial and temporal critical exponents, μ⊥ and μ∥, are defined via \({{\mathcal{P}}}(\ell )\propto {\ell }^{-{\mu }_{\perp }}\) and \({{\mathcal{P}}}(\tau )\propto {\tau }^{-{\mu }_{\parallel }}\). Generally, for 2 + 1 directed percolation (two spatial, one temporal dimension), the exponents are given by \({\mu }_{\perp }^{{{\rm{DP}}}}=1.204(2)\) and \({\mu }_{\parallel }^{{{\rm{DP}}}}=1.5495(10)\)50,59, as indicated by the dashed lines in Fig. 3. The obtained distributions show convincing agreement with these exponents, indicating that the emergence of self-sustained, active turbulent states in shear-thinning fluids may indeed be linked to a directed percolation transition. Additional simulations with different parameter values further support this conclusion, see Supplementary Note 5.

Features of the spatial and temporal structures very close to the critical point in terms of the distributions \({{\mathcal{P}}}\) of (a) the distances (lengths of the gaps) between the turbulent regions ℓ and (b) the time intervals of local quiescence τ. The distributions are normalized by the value at smallest ℓ or τ. The parameters are ζ = 2, ν0 = 1.5ν∞, and activity is a = 1.41460 for n = 2, a = 1.38825 for n = 4, and a = 1.36585 for n = 8. The activities are chosen as close to the critical points as possible, compare Fig. 1. An emergent power-law scaling near the transition for elevated ℓ and τ is consistent with 2 + 1 directed percolation ("DP''), as indicated by the dashed lines, which represent the exponents of directed percolation \({\mu }_{\perp }^{{{\rm{DP}}}}=1.204(2)\) and \({\mu }_{\parallel }^{{{\rm{DP}}}}=1.5495(10)\)50,59.

Exponents determined via fitting to the data points are close to the exponents expected for 2 + 1 directed percolation as well. From corresponding fitting procedures for Fig. 3 and additional data points, see Supplementary Fig. 4, we obtain values of the spatial exponent between μ⊥ = 1.172(5) and μ⊥ = 1.218(6) and of the temporal exponent between μ∥ = 1.5280(30) and μ∥ = 1.5860(32). Further details on the obtained values and the fitting procedure are provided in Methods section, including Table 1. We remark that the irregularities emerging in Fig. 3a for the largest considered values of ℓ are due to the finite system size of 128π × 128π.

As intuitively implied above, the link to a 2 + 1 directed percolation transition is possibly given by the emergence and time evolution of the two-dimensional turbulent patches. Numerical results show that these may spread or die out, suggesting a correspondence to the survival or decay of excited clusters in directed percolation. To further establish this analogy, we perform additional “critical-quench” simulations to determine how turbulent patches decay. For this purpose, we start at an intermediate activity of high turbulence fraction, abruptly decrease the activity to a value close to the critical point, and then observe the time evolution of the turbulence fraction Φ(t). For every investigated magnitude of activity, these simulations are repeated 200 times to obtain adequate statistics. Figure 4 shows Φ(t) for different values of a close to the critical point for an exemplary set of parameters. Below criticality, Φ(t) seems to decay exponentially to zero, whereas above criticality, Φ(t) saturates at a finite value. At the critical point, we observe approximately algebraic decay according to a power law Φ(t) ∝ t−α in the long-time limit. In 2 + 1 directed percolation, the corresponding exponent is given as αDP = 0.4505(10)50,59. Fitting α for 300 < t < 5000 in the situation presented in Fig. 4, we obtain α = 0.4207(16). Thus, the decay of Φ(t) at criticality is roughly consistent with directed percolation.

Evolution of the turbulence fraction Φ(t) after abruptly reducing the activity from a = 1.4 to values close to the critical point. For activities larger than the critical value, a > a*, Φ(t) saturates at a finite value, whereas for a < a*, Φ(t) decays to zero. At the critical activity, here a* ≈ 1.3875, we observe approximate power-law scaling, Φ(t) ∝ t−α, consistent with 2 + 1 directed percolation. This is indicated by the dashed black line, which represents the exponent of directed percolation αDP = 0.4505(10)50,59. The remaining parameters are ζ = 2, ν0 = 1.5ν∞, and n = 4. Error bars denote the standard error.

Our results open the path for further exploration of the actual nature of the transition between quiescence and self-sustained patchy mesoscale turbulence. We here find multiple features at the critical point that are consistent with directed percolation. A major next step is to investigate how the activity a relates to the control parameter in directed percolation. In this context, key questions concern the spreading probability of turbulent patches as well as the motion of fronts separating turbulence and quiescence57.

State diagrams

Finally, to summarize, Fig. 5 shows state diagrams of the shear-thinning active suspension as a function of activity a and viscosity ratio ν0/ν∞ for different values of reference shear rate ζ. The linear instability of the quiescent state for a > ν0/ν∞ yields the diagonal line, right of which we always encounter a fully turbulent state of the entire system. Left of the diagonal, the hysteretic region of coexistence is found above a certain threshold activity. Further to the left, we find the state of complete macroscopic quiescence.

The observed states for the entire system as a function of activity a and viscosity ratio ν0/ν∞ for n = 4 as well as (a) ζ = 1 and (b) ζ = 2. The quiescent state is linearly unstable for a > ν0/ν∞ (diagonal line), resulting in a fully turbulent state. For activities below the linear instability, a < ν0/ν∞, but right to the dashed line, there is a region of hysteresis and spatial coexistence between turbulent and quiescent regions.

When comparing Fig. 5a, b, we observe that an increase in crossover shear rate shifts the region of hysteresis and spatial coexistence to higher activity a. We give an intuitive explanation in the following. The turbulent and quiescent states correspond to low- and high-viscosity domains, respectively. Both regimes must be accessible for the system, so that these two states can coexist. However, for too low activity, local shear rates mostly remain too low so that shear thinning does not set in effectively. Thus, the system does not reach the low-viscosity regime. In particular, local shear rates must significantly exceed the crossover shear rate ζ for shear thinning to play a significant role. Together with an increased value of ζ, the minimum required activity to facilitate self-sustained turbulence based on shear thinning thus becomes larger. Consequently, the coexistence region in the state diagram is shifted to the top right.

Discussion

Summarizing, we reveal heterogeneous spatial coexistence of self-sustained turbulent and macroscopically quiescent regions in shear-thinning active suspensions. These states are found in emergent hysteretic regimes of mesoscale turbulence as a function of activity. Concerning the associated anomalous velocity statistics, we mention related experimental observations on bacterial suspensions of Bacillus subtilis7,60,61. There, motile and immotile areas coexist, induced, for example, by the presence of sublethal doses of antibiotics60 or elevated aspect ratios7. We here provide an illustrative explanation via non-Newtonian shear thinning. For instance, excretions of bacteria5,21,22 can induce such shear thinning in biological suspensions. Our explanation is not based on density variations as involved, for example, in motility-induced phase separation62,63.

Concerning experimental realizations, it is useful to classify the explored range of activities a. In a recent study42, the turbulent states obtained by solving the equation for a Newtonian suspension are compared with the spatiotemporal patterns in bacterial suspensions of Bacillus subtilis. For example, the parameter choice Γ0 = 103 μm2 s−1, Γ2/Γ0 = 1.24 × 102 μm2 and Γ4/Γ0 = 3.53 × 102 μm4 leads to good agreement. In our rescaled equations, this choice corresponds to a dimensionless activity of a ≈ 1.1. This value is in the range of the activities investigated in our study. Since we have observed the same qualitative behavior for all parameter sets, we expect experimental studies aiming to investigate the impact of shear thinning on active suspensions to be feasible. Our work may serve as a guide to choose shear-thinning solvent media with appropriate properties.

Obviously, Eqs. (1) and (2) reproduce well the phenomenology of active suspensions as observed in experiments. This was confirmed quantitatively in a recent study43, where reasons for this match were discussed in detail. In particular, the theory including higher-order Laplaceans in the stress tensor captures the selection of a characteristic vortex size while the presence of the nonlinear advection term leads to turbulence-like dynamics. One may raise the question about the significance of the nonlinear term in the context of microswimmer suspensions, which contain microscopic objects of micrometer size. In favor of its relevance, the effective viscosity of the overall suspension on length scales larger than the microswimmers can be substantially lowered in active suspensions64,65,66,67. Moreover, the characteristic length scale of collective motion, that is, the vortex size, is much larger than single microswimmers10,11,13. Also the speed of collective motion can be larger than the speed of individual microswimmers13. All these effects, a lower overall viscosity, larger relevant length scales, as well as increased collective speed of motion, contribute to an increase in the effective Reynolds number. We refer to Supplementary Note 1 for a more detailed discussion. Moreover, we note that the nonlinear term is not only connected to inertial effects in the classical sense. Particularly, in the classical sense, it is associated with advective transport. Therefore, in the present context, it also expresses the fact of active transport induced by the active agents. This active transport can certainly play a major role in thin films of active suspensions. There is a previous consideration of this context68. Corresponding active contributions stress the importance of the nonlinear term and imply an additional increase in the effective Reynolds number.

The description may find its application also in further contexts, beyond the field of active suspensions. For instance, expansions of the stress tensor of the kind shown in Eq. (2) may provide useful approximative characterizations of emerging patterns in various other types of fluids, for example, in the case of magnetically driven flow69 or, more generally, forced70 and instability-driven turbulence71. Furthermore, the one-dimensional version of Eqs. (1) and (2), denoted as the Nikolaevskiy model72, arises in the context of seismic waves72,73 and reaction-diffusion systems74.

From a fundamental perspective, our study extends recent attempts of linking nonequilibrium transitions, such as the emergence of turbulence51,52,54,75, to universality classes of statistical physics, ranging from Ising behavior76,77 to directed percolation50,51,52,53,54. In the more practical context of applications, the observed phenomena are relevant for microfluidic and mesoscale mixing based on active suspensions78,79,80,81,82,83. Mesoscale turbulence enhances mixing. We have demonstrated that, through shear thinning, the regime of mesoscale turbulence can be extended to lower activities, as the system becomes heterogeneous and maintains self-sustained turbulent patches. In a way, the situation reminds of type-II superconductors, where, in analogy, applications can be extended to higher magnetic fields, maintaining superconductivity through emergent spatial heterogeneities in the system84.

Methods

Linear stability analysis

The linear stability analysis for the rescaled Navier–Stokes equation, that is, Eq. (4), is provided in the following. In particular, we consider the stability of the macroscopically quiescent solution v0 = 0.

As a first step, we add small perturbations to velocity and pressure,

To continue, we make the ansatz

where λ is the complex growth rate and k is the wavevector of the perturbation. We inset Eqs. (5) and (6) into Eq. (4) and linearize around the quiescent solution. Evaluating the temporal and spatial derivatives, we obtain

Multiplying by k and using the incompressibility condition \({{\bf{k}}}\cdot \delta \hat{{{\bf{v}}}}=0\) implies that \(\delta \hat{p}=0\). Thus, the growth rate λ as a function of the wavevector is determined as

We note that λ(k) is always real and find that it can become positive for

This defines the threshold value ath as introduced in the main text. At this value, a finite-wavelength instability sets in and modes associated with the wavenumber kc = 1 start to grow. Increasing a above ath, a band of unstable modes develops. The wavenumber of the mode of maximum growth rate km is close to the critical wavenumber kc.

Numerical methods

We employ a pseudo-spectral scheme to solve Eq. (4) in a two-dimensional system with periodic boundary conditions. Here, gradient terms are computed in Fourier space, which significantly speeds up the calculations85. Time integration is performed via a fourth-order Runge-Kutta method with a time step of Δt = 0.05. It is combined with an operator splitting technique treating the linear and nonlinear parts consecutively86. This approach involves the following process for every Runge-Kutta step. We first consider only the nonlinear terms in the evolution equation, which we integrate to obtain an intermediate velocity field. This field is then used as the initial condition for a second evolution problem using only the remaining linear terms. In this Runge–Kutta step, we first ignore the pressure \(\tilde{p}\). Instead, \(\tilde{p}\) is subsequently obtained via a projection method to ensure that the incompressibility condition, ∇ ⋅ v = 0 is fulfilled85. Here, we compute the divergence of the velocity field obtained via the Runge–Kutta step as describe above. The pressure is then determined in Fourier space as the solution of a Poisson equation that renders the velocity field divergence-free85.

The main results are obtained by starting the numerical calculations for an activity a that is large enough for turbulence to develop. That is, we select a > ν0/ν∞, implying that the macroscopically quiescent state is linearly unstable. The initial conditions are set to v(x, t) = 0, with small random perturbations added to each velocity component at every grid point, following a uniform distribution over [−0.01, 0.01]. We then decrease the activity a in small steps, let the calculations run for 500 time units, and store the resulting velocity fields for subsequent calculations. These fields are used as initializations for further long-time calculations, which produce the presented results within the hysteretic regime. We have confirmed that the results do not depend on the specific numerical procedure. For example, starting directly from an activity a within the hysteretic regime and adding a sufficiently strong local perturbation (such as a localized lattice-like arrangement of vortices) results in patchy turbulent states as well, see Supplementary Note 6.

Before analyzing the dynamics, we always let the simulations for a set of parameters run for at least 3000 time units to ensure the development of statistically stationary states. We have confirmed that these long waiting times are sufficient to exclude transient behavior, see Supplementary Note 6. Close to the critical point, simulations are run even longer (up to 30000 time units). The mean enstrophy 〈ω2〉, the velocity distribution \({{\mathcal{P}}}(v)\), and the turbulence fraction Φ are averaged over 5 consecutive time intervals of 1500 time units. Error bars in the figures denote the standard error, that is, the standard deviation divided by the square root of the number of time intervals.

The velocity statistics \({{\mathcal{P}}}(v)\) as shown in Fig. 2d are determined as an average over \({{\mathcal{P}}}({v}_{x})\) and \({{\mathcal{P}}}({v}_{y})\), that is, the distributions for x and y velocity components, respectively. Due to the statistical dynamical isotropy of the turbulent state, see Supplementary Note 2, the two distributions are the same within our statistical errors. The same holds for the quiescent gap length distribution \({{\mathcal{P}}}(\ell )\), which is determined as an average over \({{\mathcal{P}}}({\ell }_{x})\) and \({{\mathcal{P}}}({\ell }_{y})\). The distributions \({{\mathcal{P}}}(\tau )\) and \({{\mathcal{P}}}(\ell )\) are determined as close as possible to the critical point to investigate the transition regarding a possible link to the directed percolation universality class. Here, we analyze the dynamics in a window of at least 10000 time units.

For most calculations, the system size is set to 128π × 128π and the spatial resolution to 768 × 768 grid points. We have checked that the systems considered are large enough so that finite-size effects do not play any obvious role, see Supplementary Note 7 and Supplementary Fig. 6. To obtain the state diagrams shown in Fig. 5, we rather use a system size of 64π × 64π and 384 × 384 grid points. These sizes are quite large compared to the vortex size, which is close to the critical length scale 2π/kc = 2π. To ensure stability, we only explore activity regimes of a < 1.5515.

Coarse-graining prodecure

To analyze the coexistence of turbulent and macroscopically quiescent regions in space, we first employ a coarse-graining procedure to smoothen the locally nonuniform vortex patterns. In particular, we average the local viscosity over a square region of side length Δx around each point in space. The resulting coarse-grained viscosity field νcg(x, t) at location x = (x, y) is thus obtained from the field ν(x, t) via

where \(\tilde{{{\bf{x}}}}=(\tilde{x},\tilde{y})\). As the vortex structures emerge from the finite-wavelength instability at a = ν0/ν∞, we here choose a side length Δx equal to the critical length scale, that is, Δx = 2π/kc = 2π. The more refined structure of patterns is thus averaged out.

When investigating the spatial coexistence of turbulent and macroscopically quiescent domains, we apply the relations derived above for global linear stability to the local scale. Locally, the quantity of interest is the coarse-grained viscosity νcg(x, t). For our purpose, we replace in Eq. (9) ν0 by νcg(x, t). Then, approximately, we expect a quiescent domain to be stable if, for that domain, νcg(x, t) > ν*(a) = aν∞. Contrarily, if νcg(x, t) < ν* = aν∞, local perturbations grow and turbulence can sustain itself in this area. Overall, this condition allows to distinguish between turbulent and quiescent regions. It forms the basis of the color scale that we have chosen for illustration in Fig. 2e, f. Green color indicates quiescent domains of νcg(x, t) > ν*, whereas purple color marks turbulent regions of νcg(x, t) < ν*.

Fitting critical exponents

In a directed percolation transition, the spatial and temporal structure of the system becomes scale-free at the critical point. This is observed in the distributions \({{\mathcal{P}}}(\ell )\) and \({{\mathcal{P}}}(\tau )\) of the size ℓ and duration τ of gaps between excited (here corresponding to turbulent) domains. At the critical point, these distributions follow power laws, \({{\mathcal{P}}}(\ell )\propto {\ell }^{-{\mu }_{\perp }}\) and \({{\mathcal{P}}}(\tau )\propto {\tau }^{-{\mu }_{\parallel }}\). In directed percolation, the critical exponents μ⊥ and μ∥ are related to the exponents of perpendicular (spatial) and parallel (temporal) correlation lengths, \({\nu }_{\perp }^{{{\rm{DP}}}}\) and \({\nu }_{\parallel }^{{{\rm{DP}}}}\), respectively, via \({\mu }_{\perp }^{{{\rm{DP}}}}=2-{\beta }^{{{\rm{DP}}}}/{\nu }_{\perp }^{{{\rm{DP}}}}\) and \({\mu }_{\parallel }^{{{\rm{DP}}}}=2-{\beta }^{{{\rm{DP}}}}/{\nu }_{\parallel }^{{{\rm{DP}}}}\)50,52. There, βDP is the critical exponent of the proportion of excited regions50,52.

So far, a direct linear correspondence between the control parameter in directed percolation and the activity or other parameters in the type of mesoscale turbulence addressed above has not been revealed. When comparing the results, we thus focus on the behavior at the critical point directly, which in directed percolation is determined by the two exponents \({\mu }_{\perp }^{{{\rm{DP}}}}\) and \({\mu }_{\parallel }^{{{\rm{DP}}}}\). To obtain an accurate estimate of corresponding exponents in our active, shear-thinning system of mesoscale turbulence, we move as close to the critical point as possible. Fitting the curves \({{\mathcal{P}}}(\ell )\) and \({{\mathcal{P}}}(\tau )\) shown in Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4, we obtain the critical exponents for the six parameter sets on display. The results are summarized in Table 1, which includes the ranges of ℓ and τ used for the fit. We find that the exponents obtained from the fits to our data are consistent with the expected values for 2 + 1 directed percolation.

Data availability

The data in support of the reported findings are available within the paper and its supplementary information files.

Code availability

The computer codes used for the numerical calculations and analysis are published on the repository Zenodo and can be found at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15718824.

References

Vicsek, T., Czirók, A., Ben-Jacob, E., Cohen, I. & Shochet, O. Novel type of phase transition in a system of self-driven particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 1226 (1995).

Marchetti, M. C. et al. Hydrodynamics of soft active matter. Rev. Mod. Phys. 85, 1143 (2013).

Bechinger, C. et al. Active particles in complex and crowded environments. Rev. Mod. Phys. 88, 045006 (2016).

Jeckel, H. et al. Learning the space-time phase diagram of bacterial swarm expansion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 1489 (2019).

Hall-Stoodley, L., Costerton, J. W. & Stoodley, P. Bacterial biofilms: From the natural environment to infectious diseases. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 95 (2004).

Be’er, A. & Ariel, G. A statistical physics view of swarming bacteria. Mov. Ecol. 7, 1 (2019).

Be’er, A. et al. A phase diagram for bacterial swarming. Commun. Phys. 3, 66 (2020).

Dombrowski, C., Cisneros, L., Chatkaew, S., Goldstein, R. E. & Kessler, J. O. Self-concentration and large-scale coherence in bacterial dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 098103 (2004).

Sokolov, A., Aranson, I. S., Kessler, J. O. & Goldstein, R. E. Concentration dependence of the collective dynamics of swimming bacteria. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 158102 (2007).

Sokolov, A. & Aranson, I. S. Physical properties of collective motion in suspensions of bacteria. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 248109 (2012).

Wensink, H. H. et al. Meso-scale turbulence in living fluids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 14308 (2012).

Alert, R., Casademunt, J. & Joanny, J.-F. Active turbulence. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys.13 (2022).

Nishiguchi, D., Aranson, I. S., Snezhko, A. & Sokolov, A. Engineering bacterial vortex lattice via direct laser lithography. Nat. Commun. 9, 4486 (2018).

Dunkel, J., Heidenreich, S., Bär, M. & Goldstein, R. E. Minimal continuum theories of structure formation in dense active fluids. New J. Phys. 15, 045016 (2013).

Słomka, J. & Dunkel, J. Generalized Navier–Stokes equations for active suspensions. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 224, 1349 (2015).

Reinken, H., Klapp, S. H. L., Bär, M. & Heidenreich, S. Derivation of a hydrodynamic theory for mesoscale dynamics in microswimmer suspensions. Phys. Rev. E 97, 022613 (2018).

Li, G., Lauga, E. & Ardekani, A. M. Microswimming in viscoelastic fluids. J. Non-Newt. Fluid Mech. 297, 104655 (2021).

Fauci, L. J. & Dillon, R. Biofluidmechanics of reproduction. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 38, 371 (2006).

Celli, J. P. et al. Helicobacter pylori moves through mucus by reducing mucin viscoelasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 14321 (2009).

Beris, A. N., Horner, J. S., Jariwala, S., Armstrong, M. J. & Wagner, N. J. Recent advances in blood rheology: a review. Soft Matter 17, 10591 (2021).

Worlitzer, V. M. et al. Biophysical aspects underlying the swarm to biofilm transition. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn8152 (2022).

Jana, S. et al. Nonlinear rheological characteristics of single species bacterial biofilms. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 6, 19 (2020).

Teran, J., Fauci, L. & Shelley, M. Viscoelastic fluid response can increase the speed and efficiency of a free swimmer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 038101 (2010).

Li, G. & Ardekani, A. M. Undulatory swimming in non-Newtonian fluids. J. Fluid Mech. 784, R4 (2015).

Datt, C., Zhu, L., Elfring, G. J. & Pak, O. S. Squirming through shear-thinning fluids. J. Fluid Mech. 784, R1 (2015).

Montenegro-Johnson, T. D., Smith, D. J. & Loghin, D. Physics of rheologically enhanced propulsion: different strokes in generalized Stokes. Phys. Fluids 25 (2013).

van Gogh, B., Demir, E., Palaniappan, D. & Pak, O. S. The effect of particle geometry on squirming through a shear-thinning fluid. J. Fluid Mech. 938, A3 (2022).

Qiu, T. et al. Swimming by reciprocal motion at low Reynolds number. Nat. Commun. 5, 5119 (2014).

Datt, C., Nasouri, B. & Elfring, G. J. Two-sphere swimmers in viscoelastic fluids. Phys. Rev. Fluids 3, 123301 (2018).

Yasuda, K., Kuroda, M. & Komura, S. Reciprocal microswimmers in a viscoelastic fluid. Phys. Fluids 32 (2020).

Eberhard, M., Choudhary, A. & Stark, H. Why the reciprocal two-sphere swimmer moves in a viscoelastic environment. Phys. Fluids 35 (2023).

Purcell, E. M. Life at low Reynolds number. Am. J. Phys. 45, 3 (1977).

Lauga, E. & Powers, T. R. The hydrodynamics of swimming microorganisms. Rep. Prog. Phys. 72, 096601 (2009).

Bozorgi, Y. & Underhill, P. T. Role of linear viscoelasticity and rotational diffusivity on the collective behavior of active particles. J. Rheol. 57, 511 (2013).

Bozorgi, Y. & Underhill, P. T. Effects of elasticity on the nonlinear collective dynamics of self-propelled particles. J. Non-Newt. Fluid Mech. 214, 69 (2014).

Hemingway, E. J. et al. Active viscoelastic matter: From bacterial drag reduction to turbulent solids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 098302 (2015).

Hemingway, E. J., Cates, M. E. & Fielding, S. M. Viscoelastic and elastomeric active matter: Linear instability and nonlinear dynamics. Phys. Rev. E 93, 032702 (2016).

Li, G. & Ardekani, A. M. Collective motion of microorganisms in a viscoelastic fluid. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 118001 (2016).

Plan, E. L. C. V. I. M., Yeomans, J. M. & Doostmohammadi, A. Active matter in a viscoelastic environment. Phys. Rev. Fluids 5, 023102 (2020).

Reinken, H. & Menzel, A. M. Vortex pattern stabilization in thin films resulting from shear thickening of active suspensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 138301 (2024).

Liu, S., Shankar, S., Marchetti, M. C. & Wu, Y. Viscoelastic control of spatiotemporal order in bacterial active matter. Nature 590, 80 (2021).

Słomka, J. & Dunkel, J. Geometry-dependent viscosity reduction in sheared active fluids. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2, 043102 (2017).

Słomka, J. & Dunkel, J. Spontaneous mirror-symmetry breaking induces inverse energy cascade in 3d active fluids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 2119 (2017).

Toner, J., Tu, Y. & Ramaswamy, S. Hydrodynamics and phases of flocks. Ann. Phys. 318, 170 (2005).

Cross, M. M. Rheology of non-newtonian fluids: a new flow equation for pseudoplastic systems. J. Colloid Sci. 20, 417 (1965).

Barnes, H. A., Hutton, J. F. & Walters, K. An introduction to rheology, Vol. 3 (Elsevier, Amsterdam, 1989).

Bratanov, V., Jenko, F. & Frey, E. New class of turbulence in active fluids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 15048 (2015).

James, M. & Wilczek, M. Vortex dynamics and lagrangian statistics in a model for active turbulence. Eur. Phys. J. E 41, 21 (2018).

Mukherjee, S., Singh, R. K., James, M. & Ray, S. S. Intermittency, fluctuations and maximal chaos in an emergent universal state of active turbulence. Nat. Phys. 19, 891 (2023).

Takeuchi, K. A., Kuroda, M., Chaté, H. & Sano, M. Directed percolation criticality in turbulent liquid crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 234503 (2007).

Sipos, M. & Goldenfeld, N. Directed percolation describes lifetime and growth of turbulent puffs and slugs. Phys. Rev. E 84, 035304(R) (2011).

Lemoult, G. et al. Directed percolation phase transition to sustained turbulence in Couette flow. Nat. Phys. 12, 254 (2016).

Sano, M. & Tamai, K. A universal transition to turbulence in channel flow. Nat. Phys. 12, 249 (2016).

Doostmohammadi, A., Shendruk, T. N., Thijssen, K. & Yeomans, J. M. Onset of meso-scale turbulence in active nematics. Nat. Commun. 8, 15326 (2017).

Chantry, M., Tuckerman, L. S. & Barkley, D. Universal continuous transition to turbulence in a planar shear flow. J. Fluid Mech. 824, R1 (2017).

Klotz, L., Lemoult, G., Avila, K. & Hof, B. Phase transition to turbulence in spatially extended shear flows. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 014502 (2022).

Gomé, S., Rivière, A., Tuckerman, L. S. & Barkley, D. Phase transition to turbulence via moving fronts. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 264002 (2024).

Hinrichsen, H. Non-equilibrium critical phenomena and phase transitions into absorbing states. Adv. Phys. 49, 815 (2000).

Muñoz, M. A., Dickman, R., Vespignani, A. & Zapperi, S. Avalanche and spreading exponents in systems with absorbing states. Phys. Rev. E 59, 6175 (1999).

Benisty, S., Ben-Jacob, E., Ariel, G. & Be’er, A. Antibiotic-induced anomalous statistics of collective bacterial swarming. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 018105 (2015).

Ilkanaiv, B., Kearns, D. B., Ariel, G. & Be’er, A. Effect of cell aspect ratio on swarming bacteria. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 158002 (2017).

Worlitzer, V. M. et al. Motility-induced clustering and meso-scale turbulence in active polar fluids. New J. Phys. 23, 033012 (2021).

Worlitzer, V. M. et al. Turbulence-induced clustering in compressible active fluids. Soft Matter 17, 10447 (2021).

Haines, B. M., Aranson, I. S., Berlyand, L. & Karpeev, D. A. Effective viscosity of dilute bacterial suspensions: a two-dimensional model. Phys. Biol. 5, 046003 (2008).

Sokolov, A. & Aranson, I. S. Reduction of viscosity in suspension of swimming bacteria. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 148101 (2009).

Heidenreich, S., Dunkel, J., Klapp, S. H. L. & Bär, M. Hydrodynamic length-scale selection in microswimmer suspensions. Phys. Rev. E 94, 020601 (2016).

López, H. M., Gachelin, J., Douarche, C., Auradou, H. & Clément, E. Turning bacteria suspensions into superfluids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 028301 (2015).

Linkmann, M., Marchetti, M. C., Boffetta, G. & Eckhardt, B. Condensate formation and multiscale dynamics in two-dimensional active suspensions. Phys. Rev. E 101, 022609 (2020).

Ouellette, N. T. & Gollub, J. P. Curvature fields, topology, and the dynamics of spatiotemporal chaos. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 194502 (2007).

Jiménez, J. & Guegan, A. Spontaneous generation of vortex crystals from forced two-dimensional homogeneous turbulence. Phys. Fluids 19 (2007).

van Kan, A., Favier, B., Julien, K. & Knobloch, E. From a vortex gas to a vortex crystal in instability-driven two-dimensional turbulence. J. Fluid Mech. 984, A41 (2024).

Beresnev, I. A. & Nikolaevskiy, V. A model for nonlinear seismic waves in a medium with instability. Phys. D: Nonlinear Phenom. 66, 1 (1993).

Tribelsky, M. I. & Tsuboi, K. New scenario for transition to turbulence? Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 1631 (1996).

Tanaka, D. Chemical turbulence equivalent to Nikolavskii turbulence. Phys. Rev. E 70, 015202 (2004).

Reinken, H., Heidenreich, S., Baer, M. & Klapp, S. H. L. Pattern selection and the route to turbulence in incompressible polar active fluids. New J. Phys. 26, 063026 (2024).

Marcq, P., Chaté, H. & Manneville, P. Universality in Ising-like phase transitions of lattices of coupled chaotic maps. Phys. Rev. E 55, 2606 (1997).

Reinken, H., Heidenreich, S., Bär, M. & Klapp, S. H. L. Ising-like critical behavior of vortex lattices in an active fluid. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 048004 (2022).

Kim, M. J. & Breuer, K. S. Enhanced diffusion due to motile bacteria. Phys. Fluids 16, L78 (2004).

Sokolov, A., Goldstein, R. E., Feldchtein, F. I. & Aranson, I. S. Enhanced mixing and spatial instability in concentrated bacterial suspensions. Phys. Rev. E 80, 031903 (2009).

Leptos, K. C., Guasto, J. S., Gollub, J. P., Pesci, A. I. & Goldstein, R. E. Dynamics of enhanced tracer diffusion in suspensions of swimming eukaryotic microorganisms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 198103 (2009).

CP, S. & Joy, A. Friction scaling laws for transport in active turbulence. Phys. Rev. Fluids 5, 024302 (2020).

Mukherjee, S., Singh, R. K., James, M. & Ray, S. S. Anomalous diffusion and Lévy walks distinguish active from inertial turbulence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 118001 (2021).

Reinken, H., Klapp, S. H. L. & Wilczek, M. Optimal turbulent transport in microswimmer suspensions. Phys. Rev. Fluids 7, 084501 (2022).

de Gennes, P.-G., Superconductivity of metals and alloys (Westview Press, Boulder, 1999).

Canuto, C., Hussaini, M. Y., Quarteroni, A. & Zang, T. A. Spectral methods: Evolution to complex geometries and applications to fluid dynamics (Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, 2007).

Cross, M. & Greenside, H. Pattern formation and dynamics in nonequilibrium systems (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2009).

Acknowledgements

We thank Sébastien Gomé for stimulating discussions and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation, DFG) for support through the Research Grant no. ME 3571/5-1 (project number 413993436). Moreover, A.M.M. acknowledges support by the DFG through the Heisenberg Grant no. ME 3571/4-1 (project number 413993216).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M.M. and H.R. designed the study, wrote the paper, and discussed the results. H.R. developed and performed the computational calculations.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Reinken, H., Menzel, A.M. Self-sustained patchy turbulence in shear-thinning active fluids. Commun Phys 8, 270 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02200-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02200-3