Abstract

The near-Earth space environment is populated by the most energetic electrons with velocities very close to the speed of light, reaching ultra-relativistic energies. These electrons present a serious hazard to the Earth-orbiting spacecraft and are referred to as the Van Allen radiation belts.

The question of how these particles are accelerated to such energies is still unanswered. Examining the 20 April 2017 geostorm, we show that such acceleration is achievable only under extremely low plasma density conditions. The global model of radiation belts with a statistical model of plasma density fails to produce the acceleration to such high energies, whereas the model with observed plasma density variations accurately reproduces the observed acceleration at all radial locations and energies. This study demonstrates that electrons are accelerated to multi-MeV by taking energy from plasma waves when the conditions for such acceleration are preferential. It also reveals the intricate interplay between cold plasma and the enhancements of ultra-relativistic electrons that are millions of times more energetic than plasma particles. Similar acceleration may occur in planetary radiation belts, for lab plasmas, at exoplanets, and in other magnetized astrophysical objects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The unexpected discovery of very high particle radiation in near-Earth space1 opened up a new field known as space physics. The regions of high energy radiation were named Van Allen Radiation Belts, as an homage to their discoverer, James Van Allen. The theory explaining how these particles are accelerated to ultra-relativistic energies is still a subject of ongoing debate.

Up until the mid-1990s, it was commonly accepted that electrons are accelerated to relativistic energies through inward radial diffusion2,3,4,5. The random radial displacements of particles lead to net diffusive transport from the populated outer regions to the inner region, which is depleted by loss. Diffusive transport of the particles into the inner region, where the Earth’s magnetic field is stronger, results in an acceleration of particles by means of betatron/Fermi acceleration.

The dynamics of the outer radiation belt have been revisited and received a lot of attention over the last two decades. It was suggested that electrons outside of the plasmasphere could be accelerated locally by taking energy from plasma waves in the Very Low Frequency (VLF) range with kHz-scale frequencies6,7. This acceleration mechanism, potentially responsible for driving electrons to relativistic energies in the outer belt, also demonstrated the capacity for swift acceleration in the so-called slot region between the outer and the inner belts8,9,10.

The support for the existence of the local acceleration mechanism stemmed from the observations of peaks in the radial profiles of Phase Space Density (PSD)11,12, which is a density in six-dimensional momentum-configuration space. The peaks indicate that particles accelerated locally as radial diffusion tends to smooth PSD and produce monotonic profiles. However, since the spacecraft is usually not exactly in the equatorial plane, it’s difficult to observe all electrons as some will mirror closer to the equator and will not be seen by the spacecraft. Moreover, magnetic field models have uncertainties, and the results based on the profiles of PSD that used empirical models of the magnetic field models were widely debated13.

To understand the dynamics of the radiation belts on 30 August 2012, NASA launched the Radiation Belts Storm Probes, which were renamed after the successful launch of the Van Allen Probes. The Van Allen Probes spacecraft14 was equipped with suites of instruments covering a very broad range of energies up to previously not well-studied and observed ultra-relativistic energies. An observational study of electrons at these energies15 discovered the ultra-relativistic population16 in the radiation belts that showed morphological structures and behavior very different from the bulk of the radiation belts. Van Allen Probes’ measurements confirmed the presence of peaks in PSD at ultra-relativistic energies, indicating the potential presence of local acceleration in the radiation belts17. However, it remained unclear how much local acceleration and radial diffusion contribute to the acceleration of the radiation belt. The modeling efforts confirming this hypothesis were done at a particular location in space18,19 and ignored the radial diffusion. The modeling of the storm in 201218 attempted to reproduce a real storm but used only one fixed value of the background density and one value of the distance from the Earth. The density was obtained from a statistical model20 and then divided by a constant factor of 3.5. This value was then assumed constant for the entire 16-hour-long simulation, which is unrealistic. That study concluded that local acceleration was the dominant process responsible for electron acceleration during the 9 October 2012 storm but made an assumption of constant density and ignored the radial diffusion.

The predominance of local acceleration has been questioned in several follow-up studies. It remained unclear if the assumption of constant density is realistic and if the measured density represented a local density at the spacecraft location at a particular time or a global density in the region of the radiation belts. Since the modeling was done at only one radial distance of 5 Earth radii, it remained questionable if the observations would be reproduced at other radial distances. Several studies21,22,23,24 argued that a two-step process may be responsible for the acceleration of electrons to ultra-relativistic energies, and the radial diffusion needs to act together with the local acceleration to produce such high energies.

In this study, we present global simulations of the Earth’s radiation belts for the April 2017 storm. The 3D modeling demonstrates that the local acceleration to such high energies is not a universal process but occurs only when the background plasma density is extremely low. Our results demonstrate that cold particles, which are over a million times less energetic than multi-MeV (>2 MeV) and ultra-relativistic (>~4 MeV) electrons, fully control the acceleration of the radiation belt electrons to such high energies. The acceleration of particles to ultra-relativistic energies in the presence of low plasma density is the most vivid example of how collective phenomena provide the influence of low-energy particles on the high-energy tail in collisionless plasmas.

Results and Discussion

Simulations of the 20 April 2017 storm

We chose the 20 April 2017 storm for which electron measurements of Van Allen Probes, GOES, and Arase are available. This is a relatively moderate storm that shows one of the strongest accelerations to the ultra-relativistic energies during the Van Allen Probes era.

To simulate this storm, we solve the modified 3D Fokker-Planck equation accounting for radial transport, local acceleration, loss to the atmosphere, and mixed diffusion of phase space density (here denoted as f):

where L*, is a radial distance in magnetic coordinates inferred from the magnetic flux through the drifting around the Earth orbit of particles and measured in Earth radii, V and K are modified adiabatic invariants25 describing the momentum of particles and the direction of the velocity in the equatorial plane respectively. DL*L*, DVV, DKV, and DKK are the radial, V, mixed, and K diffusion coefficients, and G is the Jacobian of the transformation from adiabatic invariants to variables used in (1). The lifetime parameter τ accounts for losses of particles at small pitch angles due to collisions with atmospheric neutrals, and for loss at large radial distances outside the magnetopause.

The bounce-average diffusion coefficients due to the interactions with different waves are computed using the quasi-linear theory26,27. To account for the variable density, we calculate diffusion coefficients for various values of density (see Supplementary Fig. 1). We have inferred the evolution of cold plasma density from the EMFISIS instrument on Van Allen Probes28. The evolution of the ratio of the observed density to the value of the statistical model20 is shown in Fig. 1. The method of inferring density from data is discussed in the methods section and illustrated on Supplementary Fig. 4. An alternative method using data assimilation is also described in the methods section and the results are illustrated in the Supplementary Fig. 5. First of all, it should be noticed that the density is highly dynamic and changes over the course of the storm. The values of density as shown in Fig. 1 are often significantly below the average values by a factor varying from 2 to 5 as compared to the statistical data models at L* > 5. Such persistent and low values clearly show that the decrease in density during this storm is not local but global and persists for several days.

a Cold plasma density observed by RBSP-A spacecraft and values inferred from a statistical model20. b Same as Panel a but for RBSP-B spacecraft. c Derived smoothed ratios of the statistical model and observed density is used for modeling outside of the plasmasphere. The observed values of density for this storm are clearly below the statistical values.

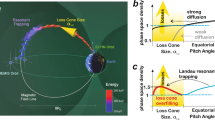

Previous studies29,30 have shown that the decrease in density can lead to an increased diffusion. As discussed in Supplementary Note 1 and illustrated in the Supplementary Fig. 1. the decrease in density results in a shift of resonances to higher energy and in the intensification of the scattering rates. With increasing energy, the scattering of relativistic electrons becomes negligible above ~2 -MeV (see Supplementary Fig. 1). So, the decrease in density produces an increase in local acceleration for multi-MeV and ultra-relativistic electrons at all values of pitch angles without increasing loss, which remains negligible even in the case of low density. While the energy diffusion is relatively slow, the lack of scattering near the loss cone ensures that particles are not lost to the atmosphere and provides gradual hardening of the spectrum. The shift in resonances to higher energies, and increased efficiency of scattering allows for the acceleration of electrons to ultra-relativistic energies when the measured density is used. The loss to the atmosphere is controlled by the scattering rates near the edge of the loss cone, which remain very slow even when the density is low, and hence the decrease in density does not significantly change the loss rates.

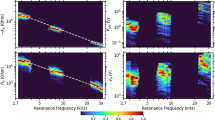

Figure 2 shows a comparison of the simulations with statistical plasma density values20, and plasma density inferred from observations. Two more energies of 2.6 and 7.7 MeV are presented in the Supplementary Fig. 2. While both simulations can approximately reproduce the dynamics of the belts, at MeV energies, only simulations with observed density evolution produce acceleration to ultra-relativistic energies. The evolution contour plot at 4.2 MeV clearly shows that in the case of constant density, there are practically no ultra-relativistic electrons, while for the simulation when the measured density is used, the modeled evolution reproduces the observed enhancement.

a RBSP-A&B MagEIS observations of electron flux at 0.9 MeV and 54° equatorial pitch-angle. b Simulated electron flux at 0.9 MeV and 54° equatorial pitch-angle using diffusion coefficients calculated for the empirical density model. c Simulated electron flux at 0.9 MeV and 54° equatorial pitch-angle using diffusion coefficients calculated using density measured by RBSP-A&B. d Kp index derived from ground observations and showing the level of geomagnetic activity throughout the storm. e–h, Same as (a–d) but for 4.2 MeV electron flux. Observations of 4.2 MeV electrons are provided by the REPT instrument.

Supplementary Note 2 also presents the simulations with density obtained from data-assimilative global simulations of plasma density, which show very similar results to the results shown in the main manuscript (see Supplementary Fig. 6).

As most of the previous 3D studies focused on the approximately 1 MeV populations, it is clear why the effect of density was not noticed in the past. The local acceleration to ultra-relativistic energies occurs only when density is low while acceleration up to 1 MeV can occur by means of a combination of radial diffusion and local acceleration at both times when density values are close to statistical values. The effects of density are not pronounced at MeV energies.

While inside the peak of PSD (L* ~ 5.5), particles at ultra-relativistic energies will be diffusing inwards and further accelerated by the radial diffusion, it’s clear that the transport by 1-2 RE will not be the dominant mechanism of acceleration from MeV up to 8 MeV and can only further increase the energy of electrons by up to 1–2 MeV (see Supplementary Fig. 7). It should be also noted that outside of the peak, radial diffusion will produce a similar effect and will work as a deceleration mechanism10,31.

Similarly, to Figs. 2, 3 shows line plots at various energies. The model results in the heart of the radiation belts clearly show that variable density decreases fluxes at 0.9 MeV and dramatically increases at multi-MeV and ultra-relativistic energies. The simulation with a statistical model of density underestimates observations at 2.6 MeV by a factor of ten and at 7.7 MeV by approximately a factor of thousand, while the simulation with observed density accurately matches the observed enhancements at a wide range of energies.

In general, simulations with observed density variations can reproduce observations with high accuracy. Some points are missing at the highest energy channel of 7.7 MeV as REPT can measure only high counts of these particles and low counts fall below the threshold levels. Small discrepancies during the main phase of the storm could be due to adiabatic changes that cannot be accurately accounted for by the used empirical field model, which is known to be inaccurate during the main phase of the storm or potentially missing EMIC-induced loss32,33 that can produce loss of electrons at these energies.

In this study, we use the time-dependent evolution of plasma density and show that plasma density controls the acceleration to ultra-relativistic electrons. This study demonstrates that a depleted plasma density is a necessary condition for such acceleration. Our simulations with realistic density controlling local acceleration reproduce the dynamics at multi-MeV and ultra-relativistic energies globally at all radial distances, showing that such energies are reached by means of local acceleration. Our simulation provides excellent agreement with observations and, unlike previous attempts to understand acceleration to such high energies, includes both radial diffusion, which is important at MeV energy, and local acceleration which starts dominating the acceleration as the energy increases. This study is also consistent with the statistical study19, which presented the correlation between the density and acceleration to high energy, and the observational study34.

Previous attempts to quantify the role of local acceleration for ultra-relativistic electrons have not been done in 3D or have not compared the dynamics with realistic and statistical background density evolution. Radial diffusion is clearly essential for accelerating particles to MeV energies. The evidence for that is provided by the radial diffusion simulations, which can approximately reproduce the dynamics of relativistic electron belts5,10,35,36. The presence of the MeV is essential for the acceleration to multi-MeV and above as these particles are the seed population for the local acceleration to multi-MeV. Radial diffusion also contributes to the redistribution of fluxes and can transport particles to lower L-shells from the center of acceleration. However, the acceleration associated with the transport by one or even several Earth radii can provide only up to 2 MeV (see Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Fig. 7), which is very small as compared to the observed acceleration of approximately MeV to 7.7 MeV. So, the majority of this acceleration is produced locally by taking energy from the VLF waves.

The non-linear scattering has been shown by a number of theoretical studies to play a most important role in the evolution of the radiation belts37,38. However, quasi-linear simulations have shown to be able to provide a surprising accuracy at all radial locations for MeV16 and now multi-MeV and ultra-relativistic energies in this study. That is also consistent with the recent results39.

The results presented here provide an example of extreme efficiency of the local acceleration if the conditions of background plasma facilitate such acceleration. Superstorms and mega-storms may significantly deplete the background plasma density even further, while waves may be even stronger. Such an event may result in acceleration to even higher energies than considered in this study. Very similar acceleration to ultra-relativistic energies is likely to occur in the magnetospheres of giant planets, exoplanets, and various astrophysical magnetized objects.

Methods

Illustration of the effects of density on the pitch angle and energy scattering

The change in density descents is an increase in resonant energy. The increase in resonant energy is clearly seen in Supplementary Fig 1. The background density is assumed to have a radial and Magnetic Local Time (MLT) profile according to a statistical model20 but divided by a variable factor according to observations. The appropriate pre-calculated diffusion coefficient is then at a particular time according to the observed density. It should be noted that the wave statistics used for calculating the diffusion coefficients do not change with different cold density levels. The development of such wave models will be the subject of future research but will be a challenging task. Current wave models already suffer from a lack of observations during storm conditions. Observations as a function of latitude for storms exhibiting density depletions will be even scarcer, requiring the integration of data from all past missions and, potentially, new measurements.

Numerical approach for the solution of the Fokker-Planck equation

The VERB code40,41 has been validated against years of Van Allen Probe observations16,42,43, a 40-day interval of CRRES41, individual storms44,45, and superstorms46. VERB solves the Fokker-Planck equation (Eq. 1) in 3 dimensions, describing the evolution of electron phase space density in terms of radial distance from Earth, and the parallel and perpendicular momentum of particles.

The mixed diffusion terms are accounted for using the fully implicit method39. To compute radial transport, we tested various radial diffusion rates47,48,49 (see Supplementary Fig. 8). We have tested the sensitivity of the code to different parameterizations and found that the radial diffusion empirical coefficients that include a dependence on the first adiabatic invariant49 give the best results at ultra-relativistic energies. Figure S8 illustrates that the main conclusions of the study do not depend on the assumed model of radial diffusion coeffects and are true for all the considered models. The models that show no dependence on energy, show a bit less realistic results at the low inner boundary of fluxes at multi-MeV, and realistic radiation belts at MeV. That indicates that a realistic parameterization of radial diffusion should have weaker diffusion rates at multi-MeV and ultra-relativistic energies49. Additional evidence for that comes from the observations of remnant belts or “storage ring”15 that persist for up to a month in the belts.

The Fokker-Planck equation cannot be solved without providing proper initial and boundary conditions. The initial condition is built from one trajectory of the RBSP-A satellite, starting around 20 April, 7:00 p.m. UTC, and ending around 20 April, 11:30 p.m. UTC. To describe the initial condition on the whole simulation grid, we extrapolate data in pitch-angle assuming a sinusoidal distribution, and extrapolate the data beyond the satellite’s apogee by propagating the flux measured at the apogee to higher L* assuming that it stays constant.

The boundary conditions have to be provided for V, K, and L*. The lower V boundary is taken from the initial condition and is assumed to stay constant throughout the storm. The upper V boundary, describing electrons above 10 MeV, is set to constant zero, describing the absence of particles at such high energies. Both boundary conditions in K are set up to be zero derivatives, describing a symmetric pitch-angle distribution around 90° and allowing a filled loss cone at 0°.

At the lower L* boundary at L* = 1, we set up a constant value of zero, while the upper L* boundary at L* = 6.6 is built from observations of two Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites (GOES-13 and -15). The particle observations are converted to phase space density as a function of V and K using the T04s magnetic field model. This allows us to use the GOES observations as a boundary at L* = 6.6, even though they are not flying at exactly L* = 6.6 throughout the storm. This method assumes that particles are transported adiabatically between the satellites’ location and L* = 6.6. Furthermore, we convert from integral to differential flux, assuming that the flux has an exponential dependence on energy. We set the flux at energies above 2 MeV to zero, assuming no incoming particles from the plasma sheet at such high energies.

Another parameter that has to be specified in the simulations is the location of the magnetopause, which can cause strong loss during geomagnetic storms10,45. The observations at 0.9 MeV indicate magnetopause shadowing during the early phase of the storm (see Supplementary Fig. 3). In this study, we assume that the L* of the magnetopause is taken from statistical models50, and then we subtract an empirical factor of 2.5 to account for the fact that the model predicts the radial distance and L* will be lower. The magnetopause is assumed to be compressed up to 22 April, 08:00 a.m. UTC, after that the magnetopause is assumed to be at L* = 10 corresponding to no magnetopause shadowing. It is also possible that EMIC waves may contribute to the loss of electrons at higher L-shells; however, since the focus of this study is acceleration, the exact details of the loss mechanism during the main phase of the storm are not a focus of this investigation.

The diffusion coefficients in V and K are pre-calculated using the Full Diffusion Code26 for different density levels. We use the chorus wave model developed from Van Allen Probes observations51 (see Supplementary Note 4). In the past, diffusion coefficients were calculated assuming the statistical Sheeley model to determine the cold plasma density. In this work, we also calculate the diffusion coefficients for all L* and MLT for plasma conditions, by assuming the Sheeley model divided by a constant factor (2,3,4,5). Based on the density measured by the satellites or predicted by the physics-based model, we decide which diffusion coefficient to use at each time point, L* and MLT. The MLT-dependent diffusion coefficients are averaged in MLT to give the final input into the VERB model.

Method of density calculation

We use the level 4 data product provided by the EMFISIS team, containing the cold plasma density derived by identifying the upper hybrid frequency or through the spacecraft potential28. The data is binned by 5 min to smooth outliers before the ratio to the MLT-resolved empirical plasma trough model20 is calculated for each point in time. Measurements inside the plasmasphere and plumes are identified by the criterion used by Sheeley20 and neglected. The derived ratios still show large variability, representing small-scale features or plasmaspheric plumes in the plasma trough (see Supplementary Fig. 4b,d). To attempt to reconstruct the average global picture of the density depletion, we calculate a moving average of the ratios using windows of 160 minutes and take the mean of the ratios derived from RBSP-A and -B (see Supplementary Fig. 4e). We tested different window sizes and this value gave us the most satisfying results considering the acceleration over all energies. The smoothed ratios are then used to decide which diffusion coefficients to use at each time point by choosing the nearest integer ratio level (see Supplementary Fig. 4f). It is, in general, possible that by averaging we underestimate the depletions and consequently the local acceleration. This potential additional local acceleration6 may be compensated by the EMIC wave scattering and loss, which can operate at these energies. However, including such events and studying this possibility would require a global and very accurate knowledge of the spatial distribution of density and EMIC waves, which is currently not available. While such effects can potentially quantitatively alter the results, they would not affect the main conclusions of the study, stating that acceleration to such high energies is not possible unless the density is globally decreased below statistical values.

Data availability

All RBSP-ECT data are publicly available at the website https://rbsp-ect.newmexicoconsortium.org/data_pub/. Kp values are from the NASA OMNIWeb data explorer, accessible at https://omniweb.gsfc.nasa.gov/form/dx1.html. The codes are publicly available at https://rbm.epss.ucla.edu/.

Code availability

The VERB-4D source code is available under this link: https://rbm.epss.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/codes/verb4d.zip.

References

Van Allen, J. A., Ludwig, G. H., Ray, E. C. & McIlwain, C. E. Observation of high intensity radiation by satellites 1958 alpha and gamma. Jet. Propuls. 28, 588–592 (1958).

Kellogg, P. J. Van Allen radiation of solar origin. Nature 183, 1295 (1959).

Falthammar, C.-G. Effects of time dependent electric fields on geomagnetically trapped radiation. J. Geophys. Res. 70, 2503–2516 (1965).

Schulz, M. & Lanzerotti, L. J. Particle Diffusion in the Radiation Belts (Springer, New York, 1974).

Hudson, M. K., Elkington, S. R., Lyon, J. G., Goodrich, C. C. & Rosenberg, T. J. Simulation of radiation belt dynamics driven by solar wind variations. in Sun-Earth Plasma Connections, Geophys. Monograph. Ser., Vol. 109, (eds Burch, J. L., Carovillano, R. L., & Antiochos, S. K.) pp. 171–182 (AGU, Washington, D. C, 1999).

Horne, R. B. & Thorne, R. M. Potential waves for relativistic electron scattering and stochastic acceleration during magnetic storms. Geophys. Res. Lett. 25, 3011–3014 (1998).

Summers, D., Thorne, R. M. & Xiao, F. Relativistic theory of wave-particle resonant diffusion with application to electron acceleration in the magnetosphere. J. Geophys. Res. 103, 20487–20500 (1998).

Baker, D. N. et al. An extreme distortion of the Van Allen belt arising from the Hallowe’en solar storm in 2003. Nature 432, 878–881 (2004).

Horne, R. B. et al. Timescale for radiation belt electron acceleration by whistler mode chorus waves. J. Geophys. Res. 110, A03225 (2005).

Shprits Y. Y. et al. Outward radial diffusion driven by losses at magnetopause, J. Geophys. Res. Space Physics, 111, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JA011657 (2006).

Green, J. C. & Kivelson, M. G. Relativistic electrons in the outer radiation belt: differentiating between acceleration mechanisms. J. Geophys. Res. 109, A03213 (2004).

Shprits, Y. Y. et al. Reanalysis of relativistic radiation belt electron fluxes using CRRES satellite data, a radial diffusion model, and a Kalman filter. J. Geophys. Res. 112, A12216 (2007).

Olifer, L., Mann, I. R., Ozeke, L. G., Morley, S. K. & Louis, H. L. On the formation of phantom electron phase space density peaks in single spacecraft radiation belt data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL092351 (2021).

Mauk, B. H. et al. Science objectives and rationale for the radiation belt storm probes mission. Space Sci. Rev. 179, 3–27 (2013).

Baker, D. N. et al. The Relativistic Electron-Proton Telescope (REPT) instrument on board the Radiation Belt Storm Probes (RBSP) spacecraft: characterization of Earth’s radiation belt high-energy particle populations. Space Sci. Rev. 179, 337–381 (2013).

Shprits, Y. Y. et al. A new population of ultra-relativistic electrons in the outer radiation zone. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 127, e2021JA030214 (2022).

Reeves, G. D. et al. Electron acceleration in the heart of the Van Allen radiation belts. Science 341, 991–994 (2013).

Thorne, R. M. et al. Rapid local acceleration of relativistic radiation-belt electrons by magnetospheric chorus. Nature 504, 411–414 (2013).

Allison, H. J., Shprits, Y., Zhelavskaya, I., Wang, D. & Smirnov, A. Gyroresonant wave-particle interactions with chorus waves during extreme depletions of plasma density in the Van Allen radiation belts. Sci. Adv. 7, eabc0380 (2021).

Sheeley, B. W., Moldwin, M. B., Rassoul, H. K. & Anderson, R. R. An empirical plasmasphere and trough density model: CRRES observations. J. Geophys. Res. 106, 25631–25641 (2001).

Katsavrias, C. et al. Highly relativistic electron flux enhancement during the weak geomagnetic storm of April–May 2017. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 124, 4402–4413 (2019).

Zhao, H., Baker, D. N., Li, X., Jaynes, A. N. & Kanekal, S. G. The acceleration of ultrarelativistic electrons during a small to moderate storm of 21 April 2017. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 5818–5825 (2018).

Zhao, H. et al. On the acceleration mechanism of ultrarelativistic electrons in the center of the outer radiation belt: A statistical study. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 124, 8590–8599 (2019).

Jaynes, A. N. et al. Fast diffusion of ultrarelativistic electrons in the outer radiation belt: 17 March 2015 storm event. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 10,874–10,882 (2018).

Subbotin, D. A. & Shprits, Y. Y. Three-dimensional radiation belt simulations in terms of adiabatic invariants using a single numerical grid. J. Geophys. Res. 117, A05205 (2012).

Shprits, Y. Y. & Ni, B. Dependence of the quasi-linear scattering rates on the wave normal distribution of chorus waves. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 114, A11205 (2009).

Orlova, K. & Shprits, Y. Y. On the bounce-averaging of scattering rates and the calculation of bounce period. Phys. Plasmas 18, 092904 (2011).

Kurth, W. S. et al. Electron densities inferred from plasma wave spectra obtained by the Waves instrument on Van Allen Probes. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 120, 904–914 (2015).

Horne, R. B., Glauert, S. A. & Thorne, R. M. Resonant diffusion of radiation belt electrons by whistler-mode chorus. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 1493 (2003).

Agapitov, O., Mourenas, D., Artemyev, A., Hospodarsky, G. & Bonnell, J. W. Time scales for electron quasi-linear diffusion by lower-band chorus waves: the effects of ωpe/Ωce dependence on geomagnetic activity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 6178–6187 (2019).

Miyoshi, Y. S., Jordanova, V. K., Morioka, A. & Evans, D. S. Solar cycle variations of the electron radiation belts: observations and radial diffusion simulation. Space Weather 2, S10S02 (2004).

Thorne, R. M. & Kennel, C. F. Relativistic electron precipitation during magnetic storm main phase. J. Geophys. Res. (1896-1977) 76, 4446–4453 (1971).

Blum, L. W., Remya, B., Denton, M. H. & Schiller, Q. Persistent EMIC Wave Activity Across the Nightside Inner Magnetosphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL087009 (2020).

Allison, H. J. & Shprits, Y. Local Heating of Radiation Belt Electrons to Ultra-relativistic Energies. Nat. Commun. 11, 4533 (2020).

Hudson, M. K. et al. Increase in the relativistic electron flux in the inner magnetosphere: ULF wave mode structure. Adv. Space Res. 25, 2327–2337 (2000).

Shprits, Y. Y., Thorne, R. M., Reeves, G. D. & Friedel, R. Radial diffusion modeling with empirical lifetimes: comparison with CRRES observations. Ann. Geophys. 23, 1467–1471 (2005).

Tsurutani, B. T., Verkhoglyadova, O. P., Lakhina, G. S. & Yagitani, S. Properties of dayside outer zone chorus during HILDCAA events: Loss of energetic electrons. J. Geophys. Res. 114, A03207 (2009).

Albert, J. M., Artemyev, A. V., Li, W., Gan, L. & Ma, Q. Models of Resonant Wave-Particle Interactions. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 126, e2021JA029216 (2021).

Artemyev, A. V., Mourenas, D., Zhang, X.-J. & Vainchtein, D. On the incorporation of nonlinear resonant wave-particle interactions into radiation belt models. J. Geophys. Res.: Space Phys. 127, e2022JA030853 (2022).

Subbotin, D. A. & Shprits, Y. Y. Three-dimensional modeling of the radiation belts using the Versatile Electron Radiation Belt (VERB) code. Space Weather 7, S10001 (2009).

Subbotin, D., Shprits, Y. Y. & Ni, B. Three-dimensional VERB radiation belt simulations including mixed diffusion. J. Geophys. Res. 115, A03205 (2010).

Wang, D. & Shprits, Y. Y. On how high-latitude chorus waves tip the balance between acceleration and loss of relativistic electrons. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 7945–7954 (2019).

Subbotin, D. A., Shprits, Y. Y. & Ni, B. Long-term radiation belt simulation with the VERB 3-D code: Comparison with CRRES observations. J. Geophys. Res 116, A12210 (2011).

Kim, K. C., Shprits, Y. Y., Subbotin, D. & Ni, B. Relativistic radiation belt electron responses to GEM magnetic storms: Comparison of CRRES observations with 3-D VERB simulations. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 117, A08221 (2012).

Wang, D. et al. The effect of plasma boundaries on the dynamic evolution of relativistic radiation belt electrons. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 125, e2019JA027422 (2020).

Shprits, Y. et al. Profound change of the near-Earth radiation environment caused by solar superstorms. Space Weather 9, https://doi.org/10.1029/2011SW000662 (2011).

Brautigam, D. H. & Albert, J. M. Radial diffusion analysis of outer radiation belt electrons during the October 9, 1990, magnetic storm. J. Geophys. Res. 105, 291–309 (2020).

Ozeke, L. G. et al. ULF wave derived radiation belt radial diffusion coefficients. J. Geophys. Res. Space Physics, 117, A04222 (2012).

Liu, W. et al. On the calculation of electric diffusion coefficient of radiation belt electrons with in situ electric field measurements by THEMIS. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 1023–1030 (2016).

Shue, J. H. et al. Magnetopause location under extreme solar wind conditions. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 103, 17691–17700 (1998).

Wang, D. et al. Analytical chorus wave model derived from Van Allen probe observations. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 124, 1063–1084 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This research has been partially funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) - SFB1294/1–318763901 and by the International Space Science Institute (ISSI) in Bern, through ISSI International Team project #24-628-Precipitation of Energetic Particles from Magnetosphere and Their Effects on the Atmosphere. D. W. acknowledges the support from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovative programme (grant agreement number: 101124679 - WIRE), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) through the project “Understanding the Properties of Chorus Waves in the Earth’s Inner-magnetosphere and Their Effects on Van Allen Radiation Belt Electrons” (Chorus Waves) - WA 4323/5–1 (project number: 520916080), and the DFG project “Magnetosphere, Ionosphere, Plasmasphere, and Thermosphere as a couple system” (MIPT) (project number: 462853228).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Y.S. Initiated and conceived the study, analyzed the results, provided funding, and wrote the manuscript. B.H. Performed and designed simulations, analyzed results, commented on the manuscript. D.W. calculated and provided diffusion coefficients.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shprits, Y.Y., Haas, B. & Wang, D. Low-density plasma as a key catalyst for electron acceleration in the Van Allen radiation belts. Commun Phys 8, 314 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02223-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02223-w