Abstract

We investigate nonreciprocal supercurrent phenomena in superconducting quantum interference devices (SQUIDs) that integrate Josephson junctions with single and multiband order parameters, which may exhibit time-reversal symmetry breaking. Our results show that the magnetic field can independently control both the amplitude and the direction of supercurrent rectification, depending on the multiband characteristics of the superconductors involved. We analyze the effects of in-phase (zero) and antiphase (π) pairing among different bands on the development of nonreciprocal effects and find that the rectification is not influenced by π-pairing. Furthermore, we demonstrate that incorporating multiband superconductors that break time-reversal symmetry produces significant signatures in rectification. The rectification exhibits an even dependence on the magnetic field and the average rectification amplitude across quantum flux multiples does not equal zero. These findings indicate that magnetic flux pumping can be accomplished with time-reversal symmetry broken multiband superconductors by adjusting the magnetic field. Overall, our results provide valuable insights for identifying and utilizing phases with broken time-reversal symmetry in multiband superconductors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is an exciting and rapidly evolving field of research in nonreciprocal superconductivity. Nonreciprocal superconductivity refers to a phenomenon where the properties of a supercurrent change based on the direction in which it flows. This behavior is distinct from conventional superconducting currents, which typically exhibit symmetric isotropic flow. Studying nonreciprocal effects and the rectification of supercurrents (the process of converting bidirectional current flow to unidirectional current flow) not only enhances our understanding of fundamental physics but also paves the way for potential applications in next-generation electronic devices and quantum technologies1,2,3,4,5.

Several directions have been explored in the design of nonreciprocal superconducting effects, with a particular emphasis on the role of materials in developing supercurrent rectifiers. Research has shown nonreciprocal superconducting transport in both traditional superconducting materials and a wide variety of other materials. These include for instance non-centrosymmetric superconductors6,7,8, chiral superconductors9, two-dimensional electron gases, semiconductors10,11, Dirac materials12, patterned superconductors13,14, superconductor-magnet hybrids15,16,17, Josephson junctions that incorporate magnetic atoms18, twisted graphene systems19,20, high-temperature superconductors21 and topological insulators22,23.

Numerous intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms have been put forward to develop a superconducting diode capable of controlling the rectification in both sign and amplitude. In this context, it is widely acknowledged that breaking time-reversal and inversion symmetries constitutes a fundamental requirement for realizing a nonreciprocal supercurrent. Various physical scenarios and mechanisms have been explored to achieve nonreciprocal supercurrent effects, including the manipulation of Cooper pair momenta19,24,25,26, the exploitation of helical phases27,28,29,30,31, magnetic texture and magnetization gradients32,33, the presence of screening currents34,35, and supercurrents associated with self-induced fields36,37.

Typically, the breaking of time-reversal symmetry is accomplished by applying external magnetic fields. Additionally, the presence of vortices is anticipated to contribute to supercurrent diode effects, and this aspect has been investigated across various physical configurations10,17,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53. Moreover, innovative proposals for magnetic field-free superconducting diodes have emerged, utilizing magnetic materials incorporated into specifically designed heterostructures15,16. Alternatively, mechanisms involving back-action supercurrent effects due to applied gating43 offer a pathway to achieve superconducting rectification effects without relying on external magnetic fields or magnetic materials. This diverse range of approaches highlights the ongoing advancements in superconducting diodes, paving the way for novel applications and technologies.

Regarding the origin of time-reversal symmetry breaking (TRSB), a large variety of superconducting materials display characteristics indicative of spontaneous TRSB below their transition temperatures54,55,56,57. This phenomenon can occur in the presence of spin or orbital angular momentum of the Cooper pairs, due to disorder58,59,60,61, or in the presence of π-pairing–characterized by an antiphase relationship between the order parameters across different bands. π-pairing and multiband electronic structures frequently occur together and usually signal the presence of unconventional superconducting phases. This is evident in various materials platforms such as iron-based superconductors62,63, oxide interface superconductors64,65, and systems exhibiting electrically or orbitally driven superconductivity66,67,68,69,70, as well as in multiband noncentrosymmetric superconductors71,72,73,74,75. Grasping the mechanisms behind TRSB in multiband phases and pinpointing effective detection methods to explore the intricacies of multiband superconductors remains a significant challenge that has not yet been fully resolved. A striking manifestation of the occurrence of TRSB superconductivity is to have a zero-field superconducting diode15,19. In this context, recently, the magnetic-field free superconducting diode effect has been observed in intrinsic flakes based on kagome CsV3Sb5 where the dynamic modulation of the polarity of the supercurrent has been interpreted as evidence of TRSB in the superconducting state76. Also, the nonzero polar Kerr effect and the specific heat measurements indicate that UTe2 belongs to the class a multicomponent superconductor, in which time-reversal symmetry is broken below the critical temperature77.

Focusing on Josephson devices employing conventional superconductors, the superconducting diode effect has been proposed by exploiting the combination of high harmonics in the Josephson current phase relation and applied magnetic field in single junctions or interferometric configurations43,78,79,80, both for dc and ac regimes81 and multiterminal geometries82,83,84. The nonreciprocal effects with conventional superconductors have been measured in Dayem bridges43 and in interferometric setups involving superconducting quantum interference devices (SQUIDs)45,85.

A different perspective is given by considering multiband superconductors that can spontaneously break time-reversal symmetry. Along this line, it has been recently shown that nonreciprocal superconducting effects can be achieved in Josephson junctions hosting multiband superconductors even without an applied magnetic field. Distinct features in the parameter space have been obtained with the multipolar distribution of the rectification amplitude, thus having a potential impact on the detection of unconventional types of pairing86.

A question now arises: Can the combined application of multiband superconductors, which undergo π-pairing or possess a superconducting order parameter that breaks time-reversal symmetry, along with a magnetic field in interferometric setups, lead to nonreciprocal effects that enhance the control of the rectification amplitude and the detection capabilities? In this paper, we face this problem by investigating the phenomena of nonreciprocal supercurrents within superconducting quantum interferometric devices (SQUIDs), which integrate Josephson junctions featuring single and multiband order parameters (see Fig. 1). Our study reveals that applying a magnetic field operating the SQUID can influence the magnitude and orientation of supercurrent rectification, in a way that depends on the multiband characteristics of the superconductors involved. We delve into how different pairing configurations—precisely zero and π-pairing across various bands—affect the emergence of nonreciprocal effects. Our analysis demonstrates that the presence of π-pairing does not alter the qualitative behavior of the rectification process as a function of the magnetic field. When we incorporate multiband superconductors that break time-reversal symmetry, we observe distinct signatures in the rectification behavior: the rectification becomes an even function with respect to the magnetic field, and the average rectification amplitude across different quantum flux multiples does not sum to zero. Moreover, for the case of SQUID based on combined single and three-band superconductors, the rectification amplitude is typically not vanishing at values of the magnetic flux for half-integers of the flux quantum Φ0.

This study sheds light on the properties of nonreciprocal transport in a dc SQUID based on multiband superconductors in the presence of a magnetic field and paves the way for the possibility of using the diode effect to detect the TRSB state in superconducting materials with a multicomponent/multiband order parameter structure.

Results

dc SQUID based on Josephson junctions with single- and two-band superconductors

Formalism

In this section, we present the formulation for deriving the expression of the supercurrents flowing within the SQUID, assuming that the junctions include a superconductor with a multiband order parameter (see Fig. 1). We start by introducing the phase differences in the Josephson junctions between the order parameter of one band of the two-band superconductor and the order parameter of the single-band superconducting part of the SQUID loop as φj, where j specifies the indices of the junctions (j = 1, 2). The single-valuedness of the phase differences around the loop, which are thicker than the London penetration depths for the single-band and the two-band superconductors, requires87,88

where Φ is the total magnetic flux and Φ0 is the flux quantum.

It is important to note that the same quantization conditions are applicable and valid for the phase differences between the second component order parameter of the two-band superconductor and the order parameter of the single-band counterpart:

which eventually coincides with the condition Eq. (1), where ϕ is the intrinsic difference between the phases of the order parameters of the two-band superconductor. This phase difference ϕ can acquire nonzero values due to the presence of interband scattering58,59,89, which is characterized by the microscopic coefficient Γij ≠ 0 (for a dirty two-band superconductor). In turn, we have that when Γij = 0 (i.e., a clean two-band superconductor), the values of ϕ are equal to 0 or π, depending on the attractive or repulsive character of the interband interaction and correspond to the pairing symmetry of s++ or s±, respectively. Instead, for ϕ different from 0 or π, a dirty two-band superconductor is characterized by a complex superposition of the two order parameters that thus breaks the time-reversal symmetry.

All calculations are performed upon the assumption that the critical temperature \({T}_{c}^{(s)}\) of the single-band superconducting part of the dc SQUID is at least not less than that of the multi-band counterpart \({T}_{c}^{(s)}\ge {T}_{c}^{(m)}\).

The total current in a DC SQUID can be represented as the sum of the currents flowing through the two Josephson junctions:

where

Here, the Josephson phase differences φj enter implicitly via the functions

where

In turn, functions Fi are expressed in terms of anomalous fi and normal gi Green’s functions, depending on the Matsubara frequency \(\omega \equiv {\omega }_{n}=\left(2n+1\right)\pi T\), and connected by the standard normalization condition \({{g}_{i}}^{2}+{\left\vert \, {f}_{i}\right\vert }^{2}=1\). These expressions are represented as:

where to avoid confusion with the notation for a magnetic flux Φ, the set of Φi functions taken from the original paper ref. 86 for the determination of the Josephson current has been redefined as F0 and Fi.

Finally, the notation \({R}_{Ni}^{(j)}\) represents the partial contributions to the resistance of the junctions (also known as the Sharvin resistance for the case of point contacts90). For simplicity and to facilitate further consideration, we assume \({R}_{N1}^{(1)}={R}_{N2}^{(1)}={R}_{N3}^{(1)}={R}_{N1}^{(2)}={R}_{N2}^{(2)}={R}_{N3}^{(2)}\), except in special cases where it will be specified.

Eq. (4) is the cornerstone of our further calculations and the subsequent consideration of a dc SQUID behavior. It was derived in ref. 86 within the Usadel equations formalism, generalized for the case of multicomponent superconductivity with the interband scattering effect included. The solution of the Usadel equations was done under the approximation of the Josephson junction as a short filament, smaller than the characteristic coherence lengths of all superconductors forming a Josephson system. This allows one to neglect all terms except the gradient ones and to obtain an analytical answer for Green’s functions and then the expression for the current by means of the parametrization in the form of Eq. (8).

Our choice to employ the Usadel formalism for the two-band model is driven by the fact that interband scattering can influence the pairing structure, particularly if a nonzero interband phase difference is realized. The use of the Usadel formalism allows us to investigate these behaviors and the role of interband scattering, thus providing extra insight into the evolution of the nonreciprocal superconducting effects in disordered superconductors.

Let us also note that in the absence of interband scattering, the Usadel equations for a two-band superconductor are split into two independent, uncoupled equations, which are expressed simultaneously in rather simple current-phase relations and at the same time in symmetric transport through Josephson junctions. As a result, the diode effect does not emerge.

For a conventional s-wave single-band superconductor F0 is given by the simple expression:

where \(\left\vert {\Delta }_{0}\right\vert\) is the modulus of the order parameter.

For a dirty two-band superconductor, the functions Fi can be written via Eq. (8) with the approximated expression for

where

and

taking into account the normalization condition for the anomalous and normal Green’s functions, together with corresponding expressions for the order parameters Δ1 and Δ2

and

Eqs. (11 and 12) are valid in the region where both \(\left\vert {\Delta }_{i}\right\vert\) are small, i.e., near the critical temperature \({T}_{c}^{(m)}\). The latter is determined not only by the intraband and interband interactions in a multiband superconductor but also by the interband scattering rate Γ = Γ12 = Γ21, where the additional assumption of equal density of states at the Fermi level for each of the bands N1 = N2 is introduced. This effect is reduced \({T}_{c}^{(m)}\) compared to the critical temperature \({T}_{c0}^{(m)}\) of a clean two-band superconductor when Γ = 058,91.

The diode rectification amplitude, η, is determined by evaluating the difference among the maximal amplitudes of the critical currents for forward (\({I}_{c}^{+}\)) and backward (\({I}_{c}^{-}\)) flow directions:

The reason for studying the nonreciprocal parameter, i.e., the rectification amplitude, is that the difference between the amplitude of the supercurrent in opposite directions is sensitive to the breaking of time reversal symmetry in the superconductor that is employed in the Josephson interferometer. Indeed, a nonvanishing and even parity magnetic field dependence of the rectification amplitude in the examined interferometric setup can be employed as evidence of an anomalous interband pairing structure.

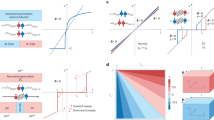

The diode effect

We start by considering the nonreciprocal transport in a dc SQUID, in which the two-band superconductor has no broken TRS state and is characterized by either s++ (order parameter phase difference is ϕ = 0) or s± (ϕ = π) pairing. The numerical calculation was performed using Eqs. (3 and 4) displays the absence of any sign of diode effect. This result is expected since it was shown earlier that the current-phase relation in each Josephson junction between s-wave and s++ or s± two-band superconductors has odd parity. However, when the partial contributions to the resistances of the Josephson junctions are no longer equal, this statement is violated, and the DC SQUID manifests evidence of nonreciprocal transport. In this case, according to the results of the evaluation presented in Fig. 2, depending on the applied magnetic flux Φ, the amplitude of rectification η is affected by the symmetry of the order parameter in the two-band superconductor: the blue curve represents η(Φ) dependence for s++ pairing and the red curve is for s± one. Interestingly, the inhomogeneity of the conducting properties of the dc SQUID allows us to distinguish two given types of symmetry of the order parameter in the two-band superconductor, exploiting the quantitative difference in the behavior of η(Φ). From the experimental point of view, this difference can be performed using a strategy similar to the one in the paper ref. 92. If the two-band part of the dc SQUID has s ± -wave symmetry, one can measure the η(Φ) dependence. Further, by means of various design strategies, one might enhance the role of impurities (e.g., by proton irradiation) in the given two-band superconductor and correspondingly track the changes of η(Φ). The potential appearance of differences between can be exploited to assess a disorder-driven transition from s± to s++ order parameter symmetry.

The thin green curve illustrates the dependence of η(Φ) based on conventional single-band s-wave superconductors with asymmetric Josephson junction characteristics, one of which includes higher \(\sin 2\varphi\) harmonics according to Eq. (20) in ref. 93 with given relations between the partial contributions of the critical currents Ib1/Ia1 = 2 and Ib2/Ia1 = 0.5. The thin black curve corresponds to the dependence η(Φ) for dc SQUID based on S-c-S type of Josephson junctions with different transparency values τ1 = 0.7, τ2 = 0.8, and described by current-phase relations in the form of Eq. (4) in ref. 78 (also known as a generalization of the current-phase relations of the KO-2 theory97,98,99, to the case of multichannel tunneling with different transparency99). The bold blue and red curves represent the η(Φ) dependencies for asymmetric dc SQUID based on Josephson junctions between a conventional single-band s-wave and s++ (ϕ = 0) and s±-wave (ϕ = π) dirty two-band superconductor \(\Gamma /{T}_{c0}^{(m)}=0.06\), respectively, with \(\left\vert {\Delta }_{1}\right\vert =2\left\vert {\Delta }_{0}\right\vert\), \(\left\vert {\Delta }_{2}\right\vert =3\left\vert {\Delta }_{0}\right\vert\) at \(T=0.7{T}_{c0}^{(m)}\), and with \({R}_{N1}^{(1)}/{R}_{N2}^{(1)}=1\), \({R}_{N1}^{(1)}/{R}_{N1}^{(2)}=2\) and \({R}_{N1}^{(1)}/{R}_{N2}^{(2)}=3\).

However, such behavior may not be treated as unique, belonging solely to this type of DC SQUID. It was shown earlier that the nonmonotonic alternating character of η(Φ) with two peaks and zero rectification amplitude at Φ = Φ0/2 should also occur for both an asymmetric higher harmonic SQUID, where one of the Josephson junctions has a higher harmonic of the current-phase relation93, and for a dc SQUID with different transmissions of Josephson junctions78 (see the thin black and green curves, respectively, in Fig. 2).

In the absence of an applied magnetic flux, we can construct a phase diagram of the dc SQUID as a Josephson diode showing the dependence of the rectification amplitude on the parameters of the dirty two-band superconductor: the microscopic coefficient Γ and the intrinsic phase difference ϕ of the order parameters. The visualization of the numerical calculations performed within Eqs. (3) and (4) are presented in Fig. 3a as a contour map of the function η(ϕ, Γ). As expected, for equal partial contributions to the resistivity of two dc SQUID Josephson junctions, it coincides with the analogous phase diagram of the Josephson junction formed by a s-wave single-band and a dirty two-band superconductor86. We note that, owing to the equal partial contributions to the resistance, the dc SQUID effectively acts like a single Josephson junction. Here, the asymmetry in the resistance would modify the phase diagram of the Josephson diode. In addition, we point out that the present phase diagram is useful to guide the discussion of the results, as it is a reference point for the study of nonreciprocal transport in a Josephson interferometer, as discussed in the next paragraph.

a The diode rectification amplitude η as a function of the intrinsic phase difference ϕ and the interband scattering rate \(\Gamma /{T}_{c0}^{(m)}\) assuming a two-band superconductor with \(\left\vert {\Delta }_{1}\right\vert =2\left\vert {\Delta }_{0}\right\vert\), \(\left\vert {\Delta }_{2}\right\vert =3\left\vert {\Delta }_{0}\right\vert\) at \(T=0.7{T}_{c0}^{(m)}\). The white-filled circles depict the reference points for tracking the evolution of η when an external magnetic flux is applied. b The diode rectification amplitude of a dc SQUID η vs an applied magnetic flux Φ/Φ0 for \(\Gamma /{T}_{c0}^{(m)}=0.02\) and ϕ = π/8 (solid black), ϕ = π/2 (solid green), ϕ = 7π/8 (solid red), ϕ = 9π/8 (dotted red), ϕ = 3π/2 (dotted green), ϕ = 15π/8 (dotted black). c The same dependencies for \(\Gamma /{T}_{c0}^{(m)}=0.06\). d The same dependencies as in (c), but with the unequal contribution to the Josephson junctions' resistance \({R}_{N1}^{(1)}/{R}_{N2}^{(1)}=1\), \({R}_{N1}^{(1)}/{R}_{N1}^{(2)}=2\) and \({R}_{N1}^{(1)}/{R}_{N2}^{(2)}=3\).

The bright red and bright blue regions on the phase diagram, which correspond to the maximum and minimum values of the rectification amplitude, are caused by the interplay between the sinusoidal and cosinusoidal components of the current-phase relations of the dc SQUID. Together with the nontrivial dependence of their amplitudes on interband scattering coefficient and the internal phase difference, a sizable value of η emerges for the domains with large Γ and ϕ near 0(2π) or simply in the vicinity of ϕ = π for an arbitrary value of Γ.

The construction of the phase diagram is performed within a non-self-consistent approach, where ϕ and Γ are assumed to be independent variables. Such an assumption is reasonable because the ϕ(Γ) dependence is also determined through four microscopic constants of intra- and interband interaction. Due to them, it is possible to choose a pair of arbitrary values of ϕ and Γ, thus describing representative cases of the family of two-band superconductors with the appropriate matrix of intra- and interband interaction coefficients. Therefore, the phase diagram in Fig. 3a illustrates the diode effect for a family of Josephson junctions including two-band superconducting systems.

We would like to clarify the role of the parameter Γ in our analysis and the overall strategy we employ to explore the parameter space. Since our approach is not self-consistent, we perform a scan over all possible values of the phase ϕ to simulate the various equilibrium configurations that can occur in a multiband superconductor. In this context, Γ is used to investigate how interband scattering influences the current-phase relation for any fixed interband phase ϕ.

We also note that interband scattering can introduce higher harmonic contributions to the current-phase relation and affect the competition between different pairing states, such as the 0 and π states, including s++ and s± configurations. In particular, the second harmonic can significantly impact the occurrence and magnitude of the rectification amplitude, especially when the multiband superconductor breaks time-reversal symmetry. An in-depth quantitative examination of the role of the interband scattering effect through the quantitative parameter Γ on the current-phase relations of the Josephson junction is carried out in Supplementary Discussion (Supplementary Note 1) using Fourier analysis (see Figs. S1 and S2 therein).

Although our treatment does not determine ϕ self-consistently, scanning across the parameter space allows us to infer the behavior of the junction under the influence of non-zero interband scattering, assuming a fixed value of ϕ. This approach allows for providing guidance independently of the specific mechanism responsible for breaking time-reversal symmetry. For example, a distinct response of the rectification amplitude is observed as Γ increases, depending on whether ϕ is near 0 or close to π.

To observe the evolution of the rectification amplitude of the dc SQUID when an external magnetic flux is applied, we impose a set of reference points on the constructed phase diagram with fixed values of Γ and ϕ (white-filled circles in Fig. 3a) to encompass all possible hallmarks and describe the behavior of such a superconducting Josephson diode. Following these points, we plot the dependencies η(Φ) for \(\Gamma =0.02{T}_{c0}^{(m)}\) (Fig. 3a), \(\Gamma =0.06{T}_{c0}^{(m)}\) (Fig. 3b) and \(\Gamma =0.08{T}_{c0}^{(m)}\) (Fig. 3c). For greater clarity and to better track the evolution of the rectification amplitude, we deliberately separated the curves of these functions for ϕ < π through solid lines and for ϕ > π using dashed lines.

Now, we can outline several features of the rectification amplitude behavior. First, it is essential to note that the diode effect is still preserved in a zero magnetic field. The diode effect vanishes when Φ = Φ0/2, as well as when Φ = Φ0/4 and Φ = 3Φ0/4 (Fig. 3b, c). The last two points with η = 0 result from the reciprocal compensation of the four contributions to the total current through Josephson junctions with equal partial resistances. The dependence of the rectification amplitude has a nonmonotonic sign variable character with two peaks (minima or maxima) where the coefficient η has the same sign. Moreover, the function η(Φ) is even with respect to the point Φ = Φ0/2.

It is obvious that the phase diagram of the Josephson diode demonstrated in Fig. 3a can also be plotted for other ratios of the order parameter moduli of the single- and two-band superconductors. Numerical simulations reveal that, to a greater or lesser extent, the diode effect is also manifested for other values of ∣Δ1∣/∣Δ0∣ and ∣Δ1∣/∣Δ0∣, except for a rather exotic case from the point of view of real superconductors case when ∣Δ1∣ = ∣Δ2∣ = ∣Δ0∣.

For completeness of the characterization, we additionally impose unequal, arbitrarily chosen contributions to the resistance of Josephson junctions and revisit the evolution of η(Φ) for the case of chiral symmetry of the order parameter with the specific value of \(\Gamma /{T}_{c0}^{(m)}=0.06\). According to the numerical calculations shown in Fig. 3d, the rectification amplitude function loses its parity and acquires an asymmetric form (compare with the set of analogous dependencies in Fig. 3c). The loss of parity of the η(Φ) dependence is an expected result since the dc SQUID is no longer acting effectively as a single Josephson junction. The non-equal contributions to the resistances form additional channels for the interference of current-phase relations with different amplitudes of the two Josephson junctions. As a result, their superposition leads to a profile without any parity of the rectification amplitude as a function of the magnetic flux.

Based on the above features of the diode effect in DC SQUID, we can introduce a quantitative criterion to identify the occurrence of the TRSB state in a multicomponent superconductor in the form of a definite integral of the function η(Φ):

If \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}=0\), as for the rectification amplitude dependencies in Fig. 2, which are odd functions, then the TRSB state does not occur in this superconductor. Otherwise, when \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}\ne 0\) as to η(Φ) shown in Fig. 3b–d, this state can emerge. It is important to note that in some exceptional cases, as shown in the following for the case of a three-band superconductor, the introduced criterion, Eq. (16), may fail.

To study the diode effect in a dc SQUID based on a two-band superconductor, a specific intermediate temperature was chosen, which is close enough to the critical temperature of the two-band superconductor without the interband scattering effect Γ = 0. Taking into account that the interband scattering suppresses the critical temperature of the two-band superconductor, such a temperature regime allows us to apply a solution of the Usadel equations for the Green functions given by the zeros of Eq. (11) and the first-order approximation as in Eq. (12). As we approach the critical temperature, we have that the first-order approximation, Eq. (12), becomes negligible, the chiral symmetry of the order parameter vanishes, and the diode effect is not realized (this occurs in the case of equal partial contributions to the Josephson junctions resistance).

Conversely, with decreasing temperature, a more complicated structure of the Green’s functions will come into play. Consequently, the diode effect will be more pronounced, acquiring a saw-tooth-like shape of the η(Φ) dependence similar to the thin black curve in Fig. 2.

dc SQUID based on Josephson junctions with single- and three-band superconductors

Formalism

The quantization condition of the phase differences of a dc SQUID can be easily generalized for the case of a three-band superconductor87,88:

where φ1 − φ2 is the phase difference of Josephson junctions between the first order parameter of a three-band superconductor and the order parameter of the conventional s-wave single-band superconducting part of the SQUID loop. The same is true for the phase differences between the second, and third order parameters of the three-band superconductor and the order parameter of the single-band counterpart:

and

where the intrinsic phase differences ϕ and θ determine the phase differences between order parameters Δ1, Δ2 and Δ1, Δ3 of a bulk three-band superconductor. The phase differences ϕ and θ control the ground states of a three-band superconductor. If ϕ and θ are not equal to 0 or π, the ground state undergoes frustration, and the TRSB state emerges. Here, we ignore the effect of interband scattering and put Γij = 0, i.e., a dirty three-band superconductor with strong enough dominant intraband scattering compared to its interband counterparts is under consideration.

For simplicity, we consider a DC SQUID at a temperature equal to zero and with energy gaps identical to each other ∣Δ0∣, for both superconductors. In this case, currents through junctions I(φ1) and \(I\left({\varphi }_{2}\right)\) can be expressed as

where

and

The diode effect

Based on Eqs. (20–22), assuming φ1 = φ2 and setting as in the previous subsection equal contributions to the Josephson junctions resistance \({R}_{N1}^{(1)}/{R}_{N2}^{(1)}=1\),\({R}_{N1}^{(1)}/{R}_{N3}^{(1)}=1\), \({R}_{N1}^{(1)}/{R}_{N1}^{(2)}=1\), \({R}_{N1}^{(1)}/{R}_{N2}^{(2)}=1\) and \({R}_{N1}^{(1)}/{R}_{N3}^{(2)}=1\), one can calculate the phase diagram of the state of a Josephson diode based on dc SQUID as a function of the internal phase differences ϕ and θ in the absence of an external magnetic field (for comparison, we recall that in the case of a dc SQUID based on a two-band superconductor, the internal phase difference ϕ and the interband scattering coefficient Γ are the governing parameters). The result presented in Fig. 4a in the form of the contour map of the function η(ϕ, θ) predictably completely reproduces the phase diagram of a superconducting diode based on the Josephson junction between a single-band and a three-band superconductor86. As in the case of a two-band superconductor, the coincidence of the phase diagrams stems from identical contributions to the resistances of the two Josephson junctions and as in the case of a two-band superconductor their mismatch would modify the nonreciprocal pattern with respect to the presented results in Fig. 4a. We also note that the present phase diagram is useful to guide the study of the diode effect when the magnetic field is included.

a Diode rectification amplitude η as a function of the internal phase differences ϕ and θ. The filled white circles illustrate the reference points for tracking the evolution of η when an external magnetic flux is applied. b Dependence of the diode rectification amplitude of a dc SQUID vs an applied magnetic flux Φ/Φ0 for θ = π/6 and ϕ = π/4 (blue), ϕ = π/2 (green), ϕ = 2π/3 (magenta), and ϕ = 5π/6 (red). c The same dependencies for θ = π/4. d The same dependencies for θ = π/3.

The reason for this behavior has already been pointed out ref. 86, and for completeness, we include the discussion here. Over the lines defined by the relations θ = (2n + 1)π/2 + ϕ, θ = (2n + 1)π/2 + ϕ, θ = nπ − ϕ, the even harmonics of the second and third terms of Eqs. (21) and (22) cancel out. This leads to the vanishing of the rectification amplitude for the case of equal contributions to the Josephson junctions’ resistance. The robustness against the applied magnetic field hints at the topological nature of these nodal lines, which will be the subject of further study.

To elucidate the behavior of the DC SQUID in an external magnetic field, we use the same strategy as in the previous subsection, i.e., we use reference points (filled white circles) to study the rectification amplitude evolution as a function of the applied magnetic flux. We have deliberately arranged this set of points in the intervals 0 < ϕ < π and 0 < θ < π (the third quadrant of the circle centered at ϕ = π and θ = π) because, as can be seen, the pattern exhibits properties of translational symmetry. Thus, considering Eq. (17) and the current-phase relations given by Eqs. (20–22), we compute the dependencies η(Φ), including the so-called nodal points, where the rectification amplitude is zero at Φ = 0 (see Fig. 4b–d).

Due to the TRSB state, the rectification amplitude η is not equal to zero in the zero magnetic field and remarkably has an even parity upon reversal of the magnetic field. The dependence of the coefficient η on the applied magnetic flux is qualitatively the same as for the dc SQUID based on a two-band superconductor, i.e., a sign-variable nonmonotonic function with the presence of two maxima (minima) of the same sign. Similarly, this function η(Φ) is symmetric with respect to the vertical line Φ = Φ0/2.

A hallmark of the dc SQUID with a three-band superconductor is the non-zero value of the rectification amplitude at Φ = Φ0/2 in the vast majority of the sets ϕ and θ corresponding to the TRSB state. At the same time, it is notable that the nodal points remain robust against the applied magnetic flux, and the rectification amplitude is strictly zero for any value of Φ. For example, Fig. 4b shows that a complete suppression of the rectification amplitude is achieved for ϕ = 5π/6 (red line) when θ = π/6. The same occurs for θ = π/4 (see Fig. 4c), where η = 0 for ϕ = π/2 (green line) and for θ = π/3 (see Fig. 4d), when ϕ = 2π/3 (magenta line).

Regarding the profile of the rectification amplitudes (Fig. 4b–d), the sharp turn arises from the presence of multiple maxima and minima in the current-phase relation due to the non-harmonic content of the current-phase relation. Then, the transition between different extremal values as the applied magnetic flux changes can lead to a rapid variation of the rectification amplitude. Indeed, when the system shifts between configurations that share the same forward or backward amplitudes, this results in a change in the slope of the rectification value in terms of the applied magnetic flux. We would like to note that this behavior can also manifest in the absence of any source of TRSB within the multiband pairing, as illustrated in Fig. 2 and in agreement with the findings of ref. 92. Furthermore, we observe that abrupt variations in the rectification amplitude tend to become more gradual at finite temperatures, owing to the averaging over various energy configurations.

We draw attention to the fact that there may be configurations where \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}=0\), and the superconductor exhibits a TRSB state. For example, this occurs at the points in the phase diagram shown in Fig. 4a, where the black solid lines intersect. Apart from the indicator, we note that the profile of the rectification amplitude in terms of the magnetic field is generally expected to have an even parity component when the time-reversal symmetry is broken through interband nontrivial phase differences.

It is worth pointing out that the asymmetry in the conductive properties of Josephson junctions has the same qualitative character as in the case of DC SQUIDs based on a two-band superconductor. In other words, the functions η(Φ) are no longer even for a superconductor with TRSB state, evolving to an asymmetric structure with \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}\ne 0\) (see Fig. 2b). In turn, the dependencies of η(Φ) for a dc SQUID based on a three-band superconductor without the TRSB state, when the internal phase differences (ϕ, θ) = (0, 0), (ϕ, θ) = (0, π), (ϕ, θ) = (π, 0) or (ϕ, θ) = (π, π), also demonstrate the diode effect with the same value \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}=0\) as in a two-band superconducting case (see Fig. 2a).

Without going into details, we also make a few remarks regarding the temperature evolution of the rectification amplitude for the dc SQUID with a three-band superconductor. As the temperature increases, the Josephson current can no longer be represented as an analytical expression of Eqs. (20–22), except near the critical temperature, where the dependence becomes sinusoidal. However, numerical calculations based on the general expression for the current of Eq. (4) reveal the transformation of sawtooth-like dependencies η(Φ) into smoother curves, and even near the critical temperature, the diode effect can be preserved with \({{{\mathcal{I}}}}\ne 0\) if the three-band superconductor still has a TRSB state.

Conclusions

Having demonstrated the behavior of a SQUID in the presence of multiband superconductors, it is interesting to discuss which materials can be employed for the proposed effects. From a practical point of view, the most suitable and promising compound for the implementation of a multicomponent superconducting element of a dc SQUID can be taken from the iron-based family, and in particular, the case of BaxK1−xFe2As2. As experiments have shown94, at the doping level x ≈ 0.73, a state with broken time-reversal symmetry emerges in this multi-band superconductor, with critical temperature \({T}_{c}^{(m)}\approx 10\) K and energy gaps in the overdoped regime (0.4 < x < 0.8) at T = 0 varying in the interval ∣Δ2∣(0) = 1 − 3 meV and ∣Δ3∣(0) = 5 − 8 meV. In general, the ratio of the energy gaps in this superconductor aligns with the ratio of the moduli of the order parameters used to probe the diode effect in a two-band superconductor (see Fig. 3). Note also that in the optimally doped regime x ≈ 0.4 ARPES studies show distinct gaps on the inner hole (smaller gap), outer hole, and electron pockets (larger gap), justifying BaxK1−xFe2As2 even as a three-band superconductor95,96. Although we have shown the existence of nonreciprocal transport in a dc SQUID in the simplest case of coinciding moduli of order parameters, it is obvious that the diode effect will take place in the more complicated case of a real three-band superconductor with unequal energy gaps.

On the other hand, the single-band s-wave part of the dc SQUID could be niobium nitride NbN with \({T}_{c}^{(s)}\approx 16\) K and the energy gap ∣Δ0∣(0) = 2.5 − 3 meV or some compounds from the superconducting A15 family (such as V3Si with \({T}_{c}^{(s)}\approx 17\) K and the energy gap ∣Δ0∣(0) = 2.4 − 2.8 meV) or even the two-band superconducting magnesium diboride MgB2 with \({T}_{c}^{(s)}\approx 39\) K, in which both components of the order parameter have an isotropic s wave structure without the presence of the broken time-reversal state. Although in our calculations the relations between the order parameter moduli in single- and two-band superconductors are a paradigmatic example, we recall the fact established in this work that the diode effect is also manifested for other energy gap relations. Therefore, the realistic choice of a single-band counterpart for a multiband superconductor mentioned here does not disrupt our conceptual conclusions regarding the emergence of nonreciprocal superconducting transport in such Josephson interferometers.

Other relevant materials to be employed are those belonging to the class of kagome materials. In this context, our results might account for the qualitative features observed in the superconducting field-free diode effects for the CsV3Sb5 kagome system76. We expect that interference between domains with different phases among the bands dependent order parameters will lead to asymmetric rectification amplitude in the applied magnetic field. Additionally, we argue that thermal cycles can lead to slight changes in the phase of the superconducting order parameter, which would be associated with a sizable modification of the polarity of the nonreciprocal response. This is explicitly demonstrated by our results when comparing time-reversal broken configurations.

We note that non-reciprocity edge over conventional current-phase relation lies in its ability to break the symmetry I(φ) = −I(−φ), i.e., the parity with respect to the Josephson phase φ, enabling directional control of supercurrents, leading to phenomena like supercurrent diode effects, and opening new avenues in superconducting device engineering (e.g., superconducting isolators and circulators, elements to protect quantum bits from noise, rectifiers in high-frequency and microwave circuits, etc.).

Our findings can be potentially relevant for single-band superconductors with multiple components (e.g., px + ipy). However, due to the directional character of the pairing components involved in the chiral state, we argue that the proposed interference effects would be sensitive to the interface orientation or to the interface character, thus making it more challenging the detect or the occurrence of nonreciprocal phenomena.

Regarding the hallmarks of the supercurrent rectification interferometric setup, we point out those related to the configurations integrating multiband superconductors with broken time reversal symmetry. Our findings show that the dependence on the magnetic field becomes even parity for junctions having equal resistance, or they do not have any parity for generic configurations. Hence, there is a net and sizable rectification amplitude when sweeping the magnetic field over positive and negative values or over multiple quantum fluxes. Then, due to the non-vanishing rectification even in the presence of magnetic field variation, we argue that with these types of SQUIDs one can envision the design of a magnetic flux pump or magnetic field rectifier.

We would like to point out that there are two primary reasons for investigating interferometric effects in multi-band superconductors. First, the majority of known superconductors feature an electronic structure with multiband or multiorbital characteristics and can display unconventional pairing that involves the spontaneous breaking of time-reversal symmetry. Examples include iron-based superconductors, heavy fermions, transition metal dichalcogenides, ruthenates, and even elemental superconductors such as niobium. Detecting and confirming the presence of TRSB in superconductors is a significant experimental challenge. Second, employing interferometric setups enables us to leverage the interference between different supercurrent channels, also related to the multiband character of the materials, through the application of magnetic fields. Our findings indicate that nonreciprocal supercurrent effects observed in such interferometric configurations may serve as signatures to probe and understand the pairing structure in multiband superconductors. This approach hence, may help to disentangle the complex nature of the pairing mechanisms.

Moreover, we emphasize that the nonreciprocal behavior observed in interferometric setups utilizing multiband superconductors that break time-reversal symmetry enables the design of a rectification amplitude with a distinctive mark: it can have an even-parity dependence on the applied magnetic field. Typically, the rectification amplitude changes sign when the magnetic field orientation is reversed. Our findings point to a different behavior that, in turn, can serve as a clear signature of the interference between supercurrents originating from multiband superconductors with broken time-reversal symmetry and conventional Josephson currents. We point out that this insight can provide valid support in understanding the magnetic field dependence of the rectification amplitude observed in kagome compounds76 and in van der Waals heterostructures such as NbSe2/Nb3Br8/NbSe215.

Regarding the advantages of the use of multiband superconductors, we also point out that they introduce multiple degrees of freedom that can augment the range of exploitation and functionality as superconducting diodes and, in principle, the efficiency (e.g., the strength of interband interaction, interband scattering, and the ratio of the order parameters' amplitudes).

The ability to detect a superconducting state with TRSB, measuring nonreciprocal supercurrents, may offer a more effective approach than other methods. This is because such measurements directly probe the symmetry breaking, regardless of the magnetic field magnitude generated by the Cooper pairs or their spatial arrangement. This is demonstrated by the distinct magnetic field dependence of the rectification amplitude when there is a nontrivial interband phase difference. We argue that this behavior with a non-vanishing rectification signal in the interferometric setup can be observed even when interband anomalous phases cancel out, resulting in a net zero phase difference.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Upadhyay, R. et al. Microwave quantum diode. Nat. Commun. 15, 630 (2024).

Castellani, M. et al. A superconducting full-wave bridge rectifier. Nat. Electron. 8, 417–425 (2025).

Ingla-Aynés, J. et al. Efficient superconducting diodes and rectifiers for quantum circuitry. Nat. Electron. 8, 411–416 (2025).

Paghi, A. et al. InAs on Insulator: a new platform for cryogenic hybrid superconducting electronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2416957 (2025).

Ingla-Aynes, J. et al. Efficient superconducting diodes and rectifiers for quantum circuitry. Nat. Electron. 5, 2520 (2025).

Wakatsuki, R. et al. Nonreciprocal charge transport in noncentrosymmetric superconductors. Sci. Adv. 3, e1602390 (2017).

Ando, F. et al. Observation of superconducting diode effect. Nature 584, 373–376 (2020).

Zhang, E. et al. Nonreciprocal superconducting NbSe2 antenna. Nat. Commun. 11, 5634 (2020).

Zinkl, B., Hamamoto, K. & Sigrist, M. Symmetry conditions for the superconducting diode effect in chiral superconductors. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 033167 (2022).

Itahashi, Y. M. et al. Nonreciprocal transport in gate-induced polar superconductor SrTiO3. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay9120 (2020).

Mondal, S., Fu, P.-H. & Cayao, J. Josephson diode effect with Andreev and Majorana bound states. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.08318 (2025).

Zeng, W. Transverse Josephson diode effect in tilted Dirac systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 176002 (2025).

Lyu, Y.-Y. et al. Superconducting diode effect via conformal-mapped nanoholes. Nat. Commun. 12, 2703 (2021).

Osin, A. S., Levchenko, A. & Khodas, M. Anomalous Josephson diode effect in superconducting multilayers. Phys. Rev. B 109, 184512 (2024).

Wu, H. et al. The field-free Josephson diode in a van der Waals heterostructure. Nature 604, 653–656 (2022).

Narita, H. et al. Field-free superconducting diode effect in noncentrosymmetric superconductor/ferromagnet multilayers. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 823–828 (2022).

Cheng, Q., Mao, Y. & Sun, Q.-F. Field-free Josephson diode effect in altermagnet/normal metal/altermagnet junctions. Phys. Rev. B 110, 014518 (2024).

Trahms, M. et al. Diode effect in Josephson junctions with a single magnetic atom. Nature 615, 628–633 (2023).

Lin, J.-X. et al. Zero-field superconducting diode effect in small-twist-angle trilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 18, 1221–1227 (2022).

Scammell, H. D., Li, J. I. A. & Scheurer, M. S. Theory of zero-field superconducting diode effect in twisted trilayer graphene. 2D Mater. 9, 025027 (2022).

Ghosh, S. et al. High-temperature Josephson diode. Nat. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-024-01804-4 (2024).

Tanaka, Y., Lu, B. & Nagaosa, N. Theory of giant diode effect in d-wave superconductor junctions on the surface of a topological insulator. Phys. Rev. B 106, 214524 (2022).

Lu, B., Ikegaya, S., Burset, P., Tanaka, Y. & Nagaosa, N. Tunable Josephson diode effect on the surface of topological insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 096001 (2023).

Pal, B. et al. Josephson diode effect from Cooper pair momentum in a topological semimetal. Nat. Phys. 18, 1228–1233 (2022).

Yuan, N. F. Q. & Fu, L. Supercurrent diode effect and finite-momentum superconductors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2119548119 (2022).

Wang, R. & Hao, N. Universal diagnostic criterion for intrinsic superconducting diode effect. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.04876 (2025).

Edelstein, V. M. Magnetoelectric Effect in Polar Superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 2004–2007 (1995).

Ilić, S. & Bergeret, F. S. Theory of the supercurrent diode effect in Rashba superconductors with arbitrary disorder. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 177001 (2022).

Daido, A. & Yanase, Y. Superconducting diode effect and nonreciprocal transition lines. Phys. Rev. B 106, 205206 (2022).

He, J. J., Tanaka, Y. & Nagaosa, N. A phenomenological theory of superconductor diodes. N. J. Phys. 24, 053014 (2022).

Turini, B. et al. Josephson diode effect in high-mobility insb nanoflags. Nano Lett. 22, 8502–8508 (2022). PMID: 36285780.

Cayao, J., Nagaosa, N. & Tanaka, Y. Enhancing the Josephson diode effect with Majorana-bound states. Phys. Rev. B 109, L081405 (2024).

Roig, M., Kotetes, P. & Andersen, B. M. Superconducting diodes from magnetization gradients. Phys. Rev. B 109, 144503 (2024).

Hou, Y. et al. Ubiquitous superconducting Diode effect in superconductor thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 027001 (2023).

Sundaresh, A., Väyrynen, J. I., Lyanda-Geller, Y. & Rokhinson, L. P. Diamagnetic mechanism of critical current non-reciprocity in multilayered superconductors. Nat. Commun. 14, 1628 (2023).

Krasnov, V. M., Oboznov, V. A. & Pedersen, N. F. Fluxon dynamics in long Josephson junctions in the presence of a temperature gradient or spatial nonuniformity. Phys. Rev. B 55, 14486–14498 (1997).

Golod, T. & Krasnov, V. M. Demonstration of a superconducting diode-with-memory, operational at zero magnetic field with switchable nonreciprocity. Nat. Commun. 13, 3658 (2022).

Suri, D. et al. Non-reciprocity of vortex-limited critical current in conventional superconducting micro-bridges. Appl. Phys. Lett. 121, 102601 (2022).

Gutfreund, A. et al. Direct observation of a superconducting vortex diode. Nat. Commun. 14, 1630 (2023).

Gillijns, W., Silhanek, A. V., Moshchalkov, V. V., Reichhardt, C. J. O. & Reichhardt, C. Origin of reversed vortex ratchet motion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 247002 (2007).

Jiang, J. et al. Reversible ratchet effects in a narrow superconducting ring. Phys. Rev. B 103, 014502 (2021).

He, A., Xue, C. & Zhou, Y.-H. Switchable reversal of vortex ratchet with dynamic pinning landscape. Appl. Phys. Lett. 115, 032602 (2019).

Margineda, D. et al. Sign reversal diode effect in superconducting dayem nanobridges. Commun. Phys. 6, 343 (2023).

Paolucci, F., De Simoni, G. & Giazotto, F. A gate- and flux-controlled supercurrent diode effect. Appl. Phys. Lett. 122, 042601 (2023).

Greco, A., Pichard, Q. & Giazotto, F. Josephson diode effect in monolithic dc-SQUIDs based on 3D Dayem nanobridges. Appl. Phys. Lett. 123, 092601 (2023).

Lustikova, J. et al. Vortex rectenna powered by environmental fluctuations. Nat. Commun. 9, 4922 (2018).

Debnath, D. & Dutta, P. Gate-tunable Josephson diode effect in Rashba spin-orbit coupled quantum dot junctions. Phys. Rev. B 109, 174511 (2024).

Mao, Y., Yan, Q., Zhuang, Y.-C. & Sun, Q.-F. Universal spin superconducting diode effect from spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 216001 (2024).

Cheng, Q. & Sun, Q.-F. Josephson diode based on conventional superconductors and a chiral quantum dot. Phys. Rev. B 107, 184511 (2023).

Sun, Y.-F., Mao, Y. & Sun, Q.-F. Design of Josephson diode based on magnetic impurity. Phys. Rev. B 108, 214519 (2023).

Banerjee, S. & Scheurer, M. S. Enhanced superconducting diode effect due to coexisting phases. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 046003 (2024).

Banerjee, S. & Scheurer, M. S. Altermagnetic superconducting diode effect. Phys. Rev. B 110, 024503 (2024).

Soori, A. Josephson diode effect in one-dimensional quantum wires connected to superconductors with mixed singlet-triplet pairing. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 37, 10LT02 (2025).

Kallin, C. & Berlinsky, J. Chiral superconductors. Rep. Prog. Phys. 79, 054502 (2016).

Wysokiński, K. I. Time reversal symmetry breaking superconductors: Sr2RuO4 and beyond. Condensed Matter. https://www.mdpi.com/2410-3896/4/2/47 (2019).

Ghosh, S. K. et al. Recent progress on superconductors with time-reversal symmetry breaking. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 33, 033001 (2020).

Zhao, S. Y. F. et al. Time-reversal symmetry breaking superconductivity between twisted cuprate superconductors. Science 382, 1422–1427 (2023).

Stanev, V. & Koshelev, A. E. Complex state induced by impurities in multiband superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 89, 100505 (2014).

Garaud, J., Corticelli, A., Silaev, M. & Babaev, E. Properties of dirty two-band superconductors with repulsive interband interaction: normal modes, length scales, vortices, and magnetic response. Phys. Rev. B 98, 014520 (2018).

Lee, W.-C., Zhang, S.-C. & Wu, C. Pairing state with a time-reversal symmetry breaking in FeAs-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 217002 (2009).

Maiti, S., Sigrist, M. & Chubukov, A. Spontaneous currents in a superconductor with s + is symmetry. Phys. Rev. B 91, 161102 (2015).

Grinenko, V. et al. Superconductivity with broken time-reversal symmetry inside a superconducting s-wave state. Nat. Phys. 16, 789–794 (2020).

Grinenko, V. et al. State with spontaneously broken time-reversal symmetry above the superconducting phase transition. Nat. Phys. 17, 1254–1259 (2021).

Scheurer, M. S. & Schmalian, J. Topological superconductivity and unconventional pairing in oxide interfaces. Nat. Commun. 6, 6005 (2015).

Singh, G. et al. Gate-tunable pairing channels in superconducting non-centrosymmetric oxides nanowires. npj Quantum Mater. 7, 2 (2022).

Mercaldo, M. T., Solinas, P., Giazotto, F. & Cuoco, M. Electrically tunable superconductivity through surface orbital polarization. Phys. Rev. Appl. 14, 034041 (2020).

Bours, L., Mercaldo, M. T., Cuoco, M., Strambini, E. & Giazotto, F. Unveiling mechanisms of electric field effects on superconductors by a magnetic field response. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 033353 (2020).

Mercaldo, M. T., Giazotto, F. & Cuoco, M. Spectroscopic signatures of gate-controlled superconducting phases. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 043042 (2021).

De Simoni, G. et al. Gate control of the current–flux relation of a Josephson quantum interferometer based on proximitized metallic nanojuntions. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 3, 3927–3935 (2021).

Mercaldo, M. T., Ortix, C. & Cuoco, M. High orbital-moment Cooper pairs by crystalline symmetry breaking. Adv. Quantum Technol. 6, 2300081 (2023).

Hillier, A. D., Quintanilla, J. & Cywinski, R. Evidence for time-reversal symmetry breaking in the noncentrosymmetric superconductor LaNiC2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 117007 (2009).

Biswas, P. K. et al. Evidence for superconductivity with broken time-reversal symmetry in locally noncentrosymmetric SrPtAs. Phys. Rev. B 87, 180503 (2013).

Shang, T. et al. Nodeless superconductivity and time-reversal symmetry breaking in the noncentrosymmetric superconductor Re24Ti5. Phys. Rev. B 97, 020502 (2018).

Singh, D. et al. Time-reversal symmetry breaking in the noncentrosymmetric superconductor \({{{{\rm{Re}}}}}_{6}{{{\rm{Hf}}}}\): further evidence for unconventional behavior in the α-Mn family of materials. Phys. Rev. B 96, 180501 (2017).

Singh, D. et al. Time-reversal symmetry breaking in the noncentrosymmetric superconductor Re6Ti. Phys. Rev. B 97, 100505 (2018).

Le, T. et al. Superconducting diode effect and interference patterns in kagome CsV3Sb5. Nature 630, 64–69 (2024).

Hayes, I. M. et al. Multicomponent superconducting order parameter in ute2. Science 373, 797–801 (2021).

Souto, R. S., Leijnse, M. & Schrade, C. Josephson diode effect in supercurrent interferometers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 267702 (2022).

Bozkurt, A. M., Brookman, J., Fatemi, V. & Akhmerov, A. R. Double-Fourier engineering of Josephson energy-phase relationships applied to diodes. SciPost Phys. 15, 204 (2023).

Yu, W. et al. Time reversal symmetry breaking and zero magnetic field Josephson diode effect in Dirac semimetal Cd3As2 mediated asymmetric squids. Phys. Rev. B 110, 104510 (2024).

Cuozzo, J. J., Pan, W., Shabani, J. & Rossi, E. Microwave-tunable diode effect in asymmetric squids with topological Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. Res. 6, 023011 (2024).

Coraiola, M. et al. Flux-tunable josephson diode effect in a hybrid four-terminal Josephson junction. ACS Nano 18, 9221–9231 (2024).

Chirolli, L. et al. Diode effect in Fraunhofer patterns of disordered multi-terminal Josephson junctions. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.19338 (2024).

Huamani Correa, J. L. & Nowak, M. P. Theory of universal diode effect in three-terminal Josephson junctions. SciPost Phys. https://doi.org/10.21468/SciPostPhys.17.2.037 (2024).

Greco, A., Pichard, Q., Strambini, E. & Giazotto, F. Double loop dc-SQUID as a tunable Josephson diode. Appl. Phys. Lett. 125, 072601 (2024).

Yerin, Y., Drechsler, S.-L., Varlamov, A. A., Cuoco, M. & Giazotto, F. Supercurrent rectification with time-reversal symmetry broken multiband superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 110, 054501 (2024).

Yerin, Y. S., Omelyanchouk, A. N. & Il’ichev, E. Dc squid based on a three-band superconductor with broken time-reversal symmetry. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 28, 095006 (2015).

Yerin, Y. S., Kiyko, A. S., Omelyanchouk, A. N. & Il’ichev, E. Josephson systems based on ballistic point contacts between single-band and multi-band superconductors. Low. Temp. Phys. 41, 885–896 (2015).

Yerin, Y., Drechsler, S.-L., Cuoco, M. & Petrillo, C. Magneto-topological transitions in multicomponent superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 106, 054517 (2022).

Sharvin, Y. V. A possible method for studying Fermi surfaces. Sov. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 21, 655 (1965).

Gurevich, A. Enhancement of the upper critical field by nonmagnetic impurities in dirty two-gap superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 67, 184515 (2003).

Ghigo, G. et al. Disorder-driven transition from s± to s++ superconducting order parameter in proton irradiated \({{{\rm{Ba}}}}{({{{{\rm{fe}}}}}_{1-x}{{{{\rm{rh}}}}}_{x})}_{2}{{{{\rm{as}}}}}_{2}\) single crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 107001 (2018).

Fominov, Y. V. & Mikhailov, D. S. Asymmetric higher-harmonic squid as a Josephson diode. Phys. Rev. B 106, 134514 (2022).

Grinenko, V. et al. Superconductivity with broken time-reversal symmetry in ion-irradiated Ba0.27K0.73Fe2As2 single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 95, 214511 (2017).

Ding, H. et al. Observation of fermi-surface-dependent nodeless superconducting gaps in Ba0.6K0.4Fe2As2. Europhys. Lett. 83, 47001 (2008).

Cai, Y. et al. Genuine electronic structure and superconducting gap structure in (Ba0.6K0.4) Fe2As2 superconductor. Sci. Bull. 66, 1839–1848 (2021).

Kulik, I. & Omelyanchouk, A. Properties ol superconducting microbridges in the pure limit. Fiz. Nizk. Temp. 3, 945–948 (1977).

Haberkorn, W., Knauer, H. & Richter, J. A theoretical study of the current-phase relation in Josephson contacts. Phys. Status Solidi 47, K161–K164 (1978).

Golubov, A. A., Kupriyanov, M. Y. & Il’ichev, E. The current-phase relation in Josephson junctions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 76, 411–469 (2004).

Acknowledgements

F.G. and M.C. acknowledge the EU’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Framework Programme under grant no. 964398 (SUPERGATE), and the PNRR MUR project PE0000023-NQSTI for partial financial support. F.G. also acknowledges the EU’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Framework Programme under grants no. 101057977 (SPECTRUM). Y.Y. acknowledges the funding received from HPC National Center for HPC, Big Data and Quantum Computing—HPC (Centro Nazionale 01—CN0000013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Y., M.C., and F.G. conceived the project. Y.Y. performed the computations. Y.Y., M.C., F.G., S.-L.D. and A.A.V. analyzed and discussed the results and the implications equally at all stages. The manuscript has been written by Y.Y., M.C. and F.G. with the help of all the authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yerin, Y., Drechsler, SL., Varlamov, A.A. et al. Supercurrent diode effect in Josephson interferometers with multiband superconductors. Commun Phys 8, 356 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02253-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02253-4