Abstract

According to holography, a black hole is dual to a thermal state in a strongly coupled quantum system. One of the best-known examples of holography is the Anti-de Sitter/Conformal Field Theory (AdS/CFT) correspondence. Despite extensive work on holographic thermodynamics, heat engines for CFT thermal states have not been explored. We construct reversible heat engines where the working substance consists of a static thermal equilibrium state of a CFT. For thermal states dual to an asymptotically AdS black hole, this yields a realization of Johnson’s holographic heat engines. We compute the efficiency for a number of idealized heat engines, such as the Carnot, Brayton, Otto, Diesel, and Stirling cycles. The efficiency of most heat engines can be derived from the CFT equation of state, which follows from scale invariance, and we compare them to the efficiencies for an ideal gas. However, the Stirling efficiency for a generic CFT is uniquely determined in terms of its characteristic temperature and volume only in the high-temperature or large-volume regime. We derive an exact expression for the Stirling efficiency for CFT states dual to AdS-Schwarzschild black holes and compare the subleading corrections in the high-temperature regime with those in a generic CFT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heat engines form a central topic in thermodynamics and played a pivotal role in its historical development1,2,3,4,5. A heat engine consists of a system (working substance) that converts heat into work and operates in a thermodynamic cycle. In such a cycle, an amount of heat (Qin) is supplied from a heat source to the system, part of which is converted into work (W) performed on a work output device, and the remainder waste heat (Qout) is expelled from the system to a heat sink (we define these three quantities to be positive). The heat source and sink can be any external systems that supply and absorbs heat, respectively, but here we take them to consist of one or more thermal reservoirs, which are large enough to exchange finite amounts of heat without changing their temperature.

The operation of a heat engine is constrained by the first and second law of thermodynamics. The first law, expressing energy conservation, reads: Qin = W + Qout. Historically, Carnot6 gave the earliest formulation of the second law in terms of engine efficiency. The efficiency of a heat engine is defined as the ratio of the work done by the system and the heat supplied into the system:

where the final expression follows from the first law.

Carnot’s theorem consists of two parts. First, for two reservoirs at fixed temperatures Th (hot) and Tc (cold), no engine can exceed the efficiency of a reversible engine operating between them. Here, reversible means recoverable: the cycle can be run backward, restoring the working substance and all surroundings (including both reservoirs) to their initial states without net change. Because the reservoirs maintain fixed temperatures, recoverability implies that the working substance be at the same temperature as the reservoir during any heat exchange, making these processes isothermal. In this special case of two fixed-temperature reservoirs, recoverability coincides with the thermodynamic (textbook) definition of reversibility: quasi-static and free of entropy production. Second, all such reversible engines – exchanging heat only isothermally with the two reservoirs – attain the same efficiency, independent of the working substance or cycle details. This universal value is known as the Carnot efficiency: ηCarnot = 1 − Tc/Th, which, by the second law, is an upper bound for any irreversible engine operating between the same two reservoirs: η≤ηCarnot.

The efficiency of an idealized heat engine that is reversible in the thermodynamic sense (quasi-static at all stages and no entropy production) is determined by the cyclic path that the working substance traces in thermodynamic state space, which differs between engines and depends on the type of working substance. In textbooks, the ideal gas is typically used as an example for computing efficiencies of such idealized cycles, but other working substances – such as a Van der Waals fluid7 or a magnetic material8 – are also possible. In this work we consider a working substance consisting of a static, global thermodynamic equilibrium state of a conformal field theory, i.e., a quantum field theory with conformal symmetry.

Our motivation for studying such heat engines comes from holography9,10, i.e., the idea that a gravitational theory in a (D + 1)-dimensional spacetime is equivalent to a quantum gauge theory without gravity living on the D-dimensional boundary of the spacetime. The best understood example of such a gauge/gravity duality is the AdS/CFT correspondence11,12,13,14. A thermal high-energy state in a holographic CFT living on the (conformal) boundary of asymptotically AdS spacetime is dual to a black hole in the bulk geometry15,16. Therefore, CFT heat engines are a tool to probe black hole physics with a thermodynamic non-gravitational system.

Theorizing about black holes as heat engines17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 and interpreting black hole heat engines in terms of a dual holographic field theory26,27,28,29 is a common theme in the literature. Particularly, the idea of holographic heat engines has been proposed by Clifford Johnson26. We offer a conceptually distinct realization of this idea, which, to our knowledge, has not been explored before. There are fundamental differences between Johnson’s heat engines and those considered in our work. On the one hand, Johnson’s starting point is an extended version of the thermodynamics of black holes in the bulk where the cosmological constant Λ is allowed to vary30,31,32,33,34 (see35 for a review). That is, he employs a bulk pressure that is proportional to Λ and inversely proportional to Newton’s constant G, Pbulk = − Λ/(8πG), and defines the thermodynamic volume as the conjugate thermodynamic quantity. On the other hand, we construct heat engines in the boundary theory, and define the pressure and volume in the CFT in the standard thermodynamic way. It is important to mention that the bulk pressure is not dual to the CFT pressure. In fact, the bulk pressure corresponds to a central charge C in the CFT or the number of colors N in a large-N SU(N) strongly-coupled gauge theory. It is questionable whether C is a thermodynamic variable, since varying it changes the physical theory36. We keep the central charge fixed, so this is not an issue in the present work. Moreover, we stress that even though we define the heat engine in the boundary CFT, there is a one-to-one correspondence between black hole thermodynamics15,18,37,38 and CFT thermodynamics16. In this work we will use the recently developed holographic dictionary in refs. 39,40,41,42,43 to compute the efficiency for heat engines dual to AdS black holes.

Our aim is to present a construction of holographic heat engines and to compute the efficiencies of various idealized engines: Carnot, Brayton, Otto, Diesel, Stirling and the rectangular pressure-volume cycle. We show for most heat engines, except for Stirling, the efficiency is uniquely determined by the CFT equation of state, and is hence the same for holographic and non-holographic CFTs. The Stirling efficiency is only fixed in terms of its characteristic temperature and volume in the high-temperature or large-volume regime, and we compare the subleading corrections in this regime for a generic CFT and for a holographic CFT.

Results

CFT heat engines

We consider heat engines whose working substance is a static, global thermodynamic equilibrium state of a CFT in D spacetime dimensions. The working substance traces a closed thermodynamic cycle, returning to its initial state. We assume the cycle consists of processes that are reversible in the thermodynamic sense: they proceed quasi-statically, so the system remains in equilibrium throughout, and they produce no entropy.

For such quasi-static processes, the first law of thermodynamics reads

where Q is positive when heat enters the system and negative when it leaves. We hold fixed all other conserved quantities (such as electric charge or angular momentum) as well as the central charge of the CFT. The heat source and sink are modeled as (one or more) thermal reservoirs, large enough that their temperatures remain constant during heat exchange; this allows us to work with finite heat and work transfers (Δ) rather than infinitesimals.

Because the processes are reversible in this sense, Clausius’ relation holds,

so adiabatic and isentropic processes coincide. We can thus regard the internal energy as a function of entropy and volume, E = E(S, V), suppressing dependence on other fixed parameters. For a CFT at finite temperature and in a finite volume, E and S are not extensive, i.e., E(aS, aV) ≠ a E(S, V); however, in the high-temperature or large-volume limit, extensivity is recovered (see below).

For the idealized heat engines that we study the cycle consists of four paths and each path corresponds to a particular thermodynamic process, such as adiabatic (Q = 0), isochoric (ΔV = 0), isobaric (ΔP = 0), and isothermal (ΔT = 0) processes. Depending on the type of processes that constitute the cycle, there are different types of heat engines. We label the vertices of the four paths by i = 1, 2, 3, 4, and Ai denotes the value of the thermodynamic variable A at the ith vertex.

In order to compute the efficiencies of various CFT heat engines, we will make use of the scale invariance of CFTs. For homogeneous systems, scale invariance implies that the equation of state is E = (D − 1)PV, often called the conformal equation of state. Note that an ideal gas system satisfies a similar equation as a CFT, given by \(E=\frac{f}{2}PV\), which holds in any number of dimensions. This equation follows from combining the standard equation of state for an ideal gas PV = NT and the equipartition theorem \(E=\frac{f}{2}NT\) (in units kB = 1), where f is the number of degrees of freedom of the gas. For example, for a monatomic gas f = D − 1 and for a diatomic gas f = 2D − 3. Note that the CFT and ideal gas equations of state are the same if f = 2(D − 1), which occurs, for instance, for a triatomic (f = 6) ideal gas in D = 4.

In order to compare the CFT and ideal gas engines, we treat the two cases simultaneously and represent their linear equations of state, collectively, as

with α = f/2 for an ideal gas and α = D − 1 for a CFT. Further, for adiabats the following relation holds

In the case of an ideal gas the exponent is (α + 1)/α = 1 + 2/f, which is equal to the ratio γ ≡ CP/CV > 1 of the (temperature independent) heat capacities at constant pressure and constant volume.

Efficiencies of CFT heat engines

We now summarize our results for the efficiencies of various CFT heat engines. Supplementary Note 1 contains more detailed derivations. We express the efficiencies in terms of the characteristic thermodynamic variables of the engines that are kept fixed along the thermodynamic cycles. For the ideal gas our expressions for the efficiencies are consistent with the literature, e.g.,4,44,45,46,47.

A Carnot cycle consists of isothermal expansion (1 → 2), adiabatic expansion (2 → 3), isothermal compression (3 → 4) and adiabatic compression (4 → 1). There is an inward heat flow from the hot reservoir to the system along path 1 → 2 and an outward heat flow to the cold sink along 3 → 4. The Carnot efficiency is

In the Brayton (or Joule) cycle the working substance is first compressed adiabatically (1 → 2), heated up isobarically (2 → 3), expanded adiabatically (3 → 4) and cooled isobarically (4 → 1). The Brayton efficiency is

In an Otto cycle, which is a rough approximation of a gasoline engine, the working substance is first compressed adiabatically (1 → 2), then heated up isochorically (2 → 3), expanded adiabatically (3 → 4), and finally cooled isochorically (4 → 1). The Otto efficiency is

The Diesel cycle consists of adiabatic compression (1 → 2), isobaric heating up (2 → 3), adiabatic expansion (3 → 4) and then isochoric cooling (4 → 1). In terms of the compression ratio V1/V2 and cutoff ratio V3/V2 the Diesel efficiency reads

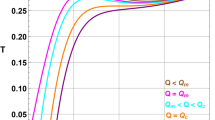

The efficiency of the Diesel cycle is always less than that of the Otto cycle if V3 > V2, for a given compression ratio (see also Fig. 1).

This plot shows the efficiency η as a function of compression ratio v for Otto (blue), Diesel (green), and Stirling (red) engines in D = 4. The solid lines correspond to a monatomic ideal gas (f = 3) and dashed lines to general CFTs (for Stirling: CFT on a plane). The fixed temperature ratio for Stirling is t ≡ Th/Tc = 2 and the fixed cutoff ratio for Diesel is V3/V2 = 1.5.

For the cycle that forms a rectangle in a PV-diagram, paths 2 → 3 and 4 → 1 are isobars, and paths 1 → 2 and 3 → 4 are isochores. The efficiency for this cycle is

Note that for \(\gamma > \frac{D}{D-1}\) the Brayton, Otto and rectangular engines are more efficient for ideal gases than for CFT working substances (see Fig. 1 for the Otto engine).

The Stirling cycle consists of two isothermal paths (expansion along 1 → 2 and compression along 3 → 4), and two isochores (2 → 3 and 4 → 1). In the absence of a regenerative heat exchanger there is heat gain along paths 1 → 2 and 4 → 1, and heat rejection along the paths 2 → 3 and 3 → 4. Without regeneration the Stirling efficiency for an ideal gas and generic CFT is

This is a universal expression that holds for a generic scale invariant system, however it depends on four thermodynamic variables, in contrast to the efficiencies of other engines. This is because in the non-regenerative Stirling cycle there is heat exchange along all four paths, and the heat exchanges along the isotherms and isochores cannot be expressed in terms of the same thermodynamic variables. We want to express the efficiency (11) in terms of T and V alone, which are the characteristic parameters of the Stirling engine, since they are constant along the isotherms and isochores, respectively, and they are experimentally controllable. In order to so do we need to know the functions S(T, V) and P(T, V), which depend on the details of the CFT and the spatial geometry.

For concreteness, we now consider a CFT working substance with a characteristic scale R and volume V ∝ RD−1, such as a round sphere of radius R. The dimensionless products ER and TR are then scale invariant, which do not change as one varies the volume. This implies the entropy and dimensionless energy ER only depend on T and V via the product TR. In a high-temperature or large-volume expansion of the entropy and energy the leading term is extensive, i.e., S ∝ (TR)D−1 ∝ TD−1V and ER ∝ (TR)D, or, equivalently, E ∝ TDV48. The pressure follows from inserting the scaling of the energy into the conformal equation of state, yielding P ∝ TD. Moreover, the scaling of the subleading terms in an expansion around TR = ∞ is also fixed: the next order is always subleading in (TR)−2 with respect to the previous order. For instance, the expansion of the scale invariant product of the canonical free energy F and R in any CFT is49

From this expansion the entropy and pressure can be explicitly computed via the standard thermodynamic relations S = − (∂F/∂T)V and P = − (∂F/∂V)T, see Supplementary Note 3. Inserting this into the Stirling efficiency (11) yields

where ξij and χij are up to order \({{{\mathcal{O}}}}({T}_{i}^{-4}{V}_{j}^{-4/(D-1)})\)

Here T1 ≡ Tc and T2 ≡ Th. Note the Stirling efficiency is uniquely fixed to leading order in the high-temperature or large-volume expansion. But to subleading order \({\eta }_{{{{\rm{Stirling}}}}}^{{{{\rm{CFT}}}}}\) depends on aD and aD−2, which are defined via (12) as the coefficients of the leading and subleading terms in the free energy expansion. These coefficients are independent of (T, V), but do depend on the matter content of CFTs. They have been explicitly computed for free CFTs in D = 4 and D = 6 in49. For instance, for \({{{\mathcal{N}}}}=4\) SYM theory with SU(N) gauge group in D = 4 we have a4 = (N2 − 1)/48 and a2 = − (N2 − 1)/8, so a4/a2 = − 1/6.

Further, for an ideal gas the change in the entropy along an isotherm is given as \(\Delta S=N\,{{{\rm{ln}}}} \left({V}_{2}/{V}_{1}\right)\) and the pressure is related to the temperature and volume by the equation of state P = NT/V. Hence, the Stirling efficiency for an ideal gas is given by

We thus find that the dependence of the Stirling efficiency on T and V is different for an ideal gas and a CFT working substance.

Although all the heat cycles we consider are reversible in the thermodynamic sense, their efficiencies are not constrained by the second part of Carnot’s theorem (see Introduction) to equal the Carnot efficiency – except for the Carnot cycle itself. This part of the theorem applies only to engines that are recoverable, which for two fixed-temperature reservoirs means all heat exchange must be isothermal with the appropriate reservoir. The Brayton, Otto, Diesel, and rectangular cycles fail this condition, as they contain no isothermal steps; heat is transferred along non-isothermal paths where the working substance’s temperature changes. Even if such cycles are carried out quasi-statically and without entropy production, these steps would require a continuum of reservoirs to remain reversible, violating the two-reservoir assumption. The Stirling engine does include isothermal expansion and compression with fixed-temperature reservoirs, but also has isochores where the working substance’s temperature changes, making those steps non-isothermal and likewise non-recoverable. The Carnot cycle alone consists entirely of isotherms and adiabats, is recoverable, and satisfies all the assumptions of the theorem, thus achieving ηCarnot = 1 − Tc/Th.

In Fig. 1 we plotted the efficiencies as a function of compression ratio v (the ratio of larger volume and smaller volume, i.e., V1/V2 for Otto and Diesel and V2/V1 for Stirling) for the Otto, Diesel and Stirling engines. For Stirling the temperature ratio t ≡ Th/Tc is kept fixed and for Diesel the cutoff ratio V3/V2 is fixed. The Otto and Diesel efficiencies asymptote to 1, and the v → ∞ limit of the Stirling efficiency is 1 − t−1 for an ideal gas and (1 − t−D)/D for a CFT on a plane. In Fig. 2 we plotted the efficiencies as a function of the temperature ratio t, at fixed compression ratio v, for the Carnot and Stirling engines. These plots show that the efficiency is universally higher for (monatomic) ideal gases than for CFTs. The Carnot efficiency asymptotes to 1, and the Stirling efficiency asymptotes to (v − 1)/(Dv − 1) for a CFT on a plane and to \({{\rm{ln}}} (v)/(f/2+{{\rm{ln}}} (v))\) for an ideal gas.

Finally, we plotted the PV-diagrams for all heat engines in Fig. 3 (for a holographic CFT) and Fig. 4 (for a monatomic ideal gas), and the TS-diagrams in Fig. 5 (for a holographic CFT) and Fig. 6 (for a monatomic ideal gas). In Supplementary Note 2 we derive the equations for the various cycle paths that are used to make these plots. The PV-diagrams for the CFT and ideal gas systems are identical for the Brayton, Otto, Diesel and rectangle engines, but different for the Carnot and Stirling engine. Moreover, the TS-plots corresponding to the CFT and ideal gase systems are different for the Brayton, Otto, Diesel, rectangle and Stirling engines, but identical for the Carnot engine. By comparing the Carnot (Figs. 3a and 4a) and Stirling cycles (Figs. 3e and 4b) we see that the isotherm for a CFT monotonically increases with V whereas the isotherm for the ideal gas monotonically decreases with V. The slope of the adiabats is also different for the two systems. Further, by comparing the cycles in Figs. 5 and 6 we see that the isochores and isobars in a TS-diagram are different for CFT and ideal gas systems.

These plots are heat cycles for thermal CFT working substances dual to AdS-Schwarzschild black holes. The number of CFT spacetime dimensions is D = 4. In all figures dotted lines correspond to isotherms, short dashed lines to adiabats, long dashed lines to isobars, and dotdashed lines to isochores. The red curves indicate the cycle, the numbers at the vertices denote the ordering of the cycle, and the arrows the direction of the cycle. Th and Tc are the temperatures of the hot and cold reservoirs, respectively. The panels represent (a) the Carnot cycle (isotherm-adiabat-isotherm-adiabat), (b) Brayton cycle (adiabat-isobar-adiabat-isobar), (c) Otto cycle (adiabat-isochore-adiabat-isochore), (d) Diesel cycle (adiabat-isobar-adiabat-isochore), (e) rectangle cycle (isochore-isobar-isochore-isobar), and (f) Stirling cycle (isotherm-isochore-isotherm-isochore).

These plots are heat cycles for (a) Carnot (isotherm-adiabat-isotherm-adiabat) and (b) Stirling (isotherm-isochore-isotherm-isochore) engines with a working substance consisting of a monatomic (γ = 5/3) ideal gas in D = 4 spacetime dimensions. The dotted lines correspond to isotherms, short dashed lines to adiabats, and dotdashed lines to isochores. The red curves indicate the cycle, the numbers at the vertices denote the ordering of the cycle, and the arrows the direction of the cycle. Th and Tc are the temperatures of the hot and cold reservoirs, respectively.

These plots are heat cycles for thermal CFT working substances dual to AdS-Schwarzschild black holes. The number of CFT spacetime dimensions is D = 4. In all figures dotted lines correspond to isotherms, short dashed lines to adiabats, long dashed lines to isobars, and dotdashed lines to isochores. The red curves indicate the cycle, the numbers at the vertices denote the ordering of the cycle, and the arrows the direction of the cycle. Th and Tc are the temperatures of the hot and cold reservoirs, respectively. The panels represent (a) the Carnot cycle (isotherm-adiabat-isotherm-adiabat), (b) Brayton cycle (adiabat-isobar-adiabat-isobar), (c) Otto cycle (adiabat-isochore-adiabat-isochore), (d) Diesel cycle (adiabat-isobar-adiabat-isochore), (e) rectangle cycle (isochore-isobar-isochore-isobar), and (f) Stirling cycle (isotherm-isochore-isotherm-isochore).

These plots are heat cycles for monatomic (γ = 5/3) ideal gas working substances in D = 4 spacetime dimensions. The dotted lines correspond to isotherms, short dashed lines to adiabats, long dashed lines to isobars, and dotdashed lines to isochores. The red curves indicate the cycle, the numbers at the vertices denote the ordering of the cycle, and the arrows the direction of the cycle. Th and Tc are the temperatures of the hot and cold reservoirs, respectively. The panels represent (a) the Brayton cycle (adiabat-isobar-adiabat-isobar), (b) Otto cycle (adiabat-isochore-adiabat-isochore), (c) Diesel cycle (adiabat-isobar-adiabat-isochore), (d) rectangle cycle (isochore-isobar-isochore-isobar), and (e) Stirling cycle (isotherm-isochore-isotherm-isochore).

Holographic heat engine

So far we have considered heat engines for generic CFTs. Next, we construct heat engines for holographic CFT states that are dual to AdS black holes. We stress that the generic CFT results for the engine efficiencies above also hold for holographic CFTs, but for the Stirling engine we can compute the efficiency exactly by invoking holography. For heat engines of holographic CFTs the geometry is fixed to be equivalent (up to Weyl rescaling) to the boundary geometry of the dual black hole spacetime. That is because we take the working substance of holographic heat engines to be the entire spatial geometry of the holographic CFT. Furthermore, we only consider black holes with positive heat capacity, since if the heat capacity were negative the cycles in the PV-diagrams 3 and 4 would act as refrigerators (and the reverse cycles would be heat engines). Large enough AdS black holes indeed have positive heat capacity and thus their thermodynamic cycles (in the order 1 → 2 → 3 → 4 → 1) can operate as heat engines.

Concretely, here we consider static, spherically symmetric, uncharged asymptotically AdS black holes, a.k.a. AdS-Schwarzschild black holes, in D + 1 spacetime dimensions. Hence, in our setup the spatial geometry of the holographic heat engine is a round sphere with radius R and volume V = ΩD−1RD−1. For these black holes the holographic dictionary reads (see Supplementary Note 4 for a derivation)39,40,41,42

We defined x ≡ rh/L with rh the horizon radius of the black hole and L the AdS curvature radius. The heat capacity at fixed V and C is positive if \(x > \sqrt{(D-2)/D}\). Crucially, the boundary volume V and the central charge C can be independently varied, since they depend on R and L, respectively. In previous dictionaries, e.g., in39,50,51, R was set equal to L, so that V and C could be independently varied only if Newton’s constant G is allowed to change. For holographic heat engines, however, we want to keep the theory parameters in the bulk and boundary fixed (G and C) while allowing V to vary, which is possible only if R ≠ L41.

We now compute the Stirling efficiency by invoking the holographic dictionary above. From (17)–(20) one can derive exact expressions for S(T, V) and P(T, V) (see Supplementary Note 5). Inserting them into (11) yields that the Stirling efficiency for CFT states dual to AdS-Schwarzschild takes the same form as (13), but now the functions ξij and χij are given by

These are exact expressions in the temperature and volume. We can expand them at high temperature or large volume. The result up to subleading order is the same as (14) and (15) with the ratio of the coefficients given by

This agrees with earlier findings for these coefficients in holographic CFTs48,49. Importantly, the holographic Stirling efficiency is lower than the leading order contribution to the efficiency in the high-temperature and large-volume expansion, for which ξij = χij = 1. Moreover, we checked by plotting that for \({{{\mathcal{N}}}}=4\) SYM theory in D = 4 the Stirling efficiency is higher at zero ’t Hooft coupling (for which a4/a2 = − 1/6) than at infinite coupling (with a4/a2 = − 1/12, cf. (22)). Thus, this suggests for CFTs the Stirling efficiency decreases as the coupling increases.

Comparison with Johnson’s holographic heat engines

Next we compare our holographic heat engines with those in Johnson’s work26,27,28,29 and subsequent follow-ups. Apart from the fact that both heat engines make use of the AdS/CFT correspondence, they are completely different. The key predictions for the efficiencies of all heat engines are distinct, and the way the engines operate is also different, as we explain below. Moreover, we do not just give predictions for holographic heat engines, but also for generic CFTs.

The main difference between the two constructions lies in the definitions of pressure and volume. Johnson considers the bulk pressure Pbulk = − Λ/(8πG), proportional to the cosmological constant Λ, and defines the volume as its conjugate quantity in the extended first law of black holes, in which Λ is being varied30,31,32,33,34. On the other hand, we construct heat engines in the dual thermal conformal field theory, where pressure and volume are defined in standard thermodynamic terms. These distinct definitions of pressure and volume imply that our holographic heat engines function in an entirely different way from Johnson’s engines. For instance, Johnson26 considered charged AdS black holes instead of Schwarzschild-AdS black holes, because in his approach the former allow for nontrivial engine cycles in the PV-plane, while the latter do not. Our construction already gives nontrivial cycles for Schwarzschild-AdS black holes.

A consequence of the previous point and a crucial difference is that in Johnson’s heat cycles, the underlying theory changes when pressure varies, whereas in our construction, the theory remains fixed. This is because varying the bulk pressure in Johnson’s approach corresponds to adjusting the cosmological constant and the number of colors N in the boundary theory. Consequently, in his model, the boundary theory itself changes during the thermodynamic cycle. However, pressure should be a thermodynamic state variable, meaning it is a property of the state and not of the theory. As emphasized in ref.36, N is not a function of the boundary spacetime, which is required for a state variable describing local thermodynamic equilibrium. This implies that changing N does not correspond to a standard thermodynamic process, but rather a flow within the space of CFTs. Therefore, Johnson26 conjectured that his engine cycles could be realized using renormalization group flow, but it remains unclear whether this is feasible, and it stands in conflict with the usual operation of heat engines. Our holographic heat engines, on the other hand, operate in the conventional thermodynamic sense, by adjusting the thermal state quasi-statically, which is a major advantage over Johnson’s approach. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the efficiency of our scale-invariant heat engines is comparable to that of ideal gas engines, showing that our approach follows standard thermodynamic principles.

A more fine-grained difference is that in Johnson’s approach the Carnot and Stirling engine are identical for charged AdS black holes, since adiabats are equal to isochores, whereas in our approach they are not. This is because both the entropy and the volume in extended thermodynamics of static AdS black holes depend only on the horizon radius, so they are not independent52. This is problematic in itself, because it implies that the energy function E(S, V) and its partial derivatives \(\left(\frac{\partial E}{\partial S}{\vert }_{V},\frac{\partial E}{\partial V}{\vert }_{S}\right)\) are ill defined. Our approach does not suffer from this degeneracy, since entropy and volume are independent variables. Thus, in our construction the Carnot and Stirling engine are distinct, as they should be.

Another key advantage of our proposal is that the efficiencies of holographic heat engines can potentially be experimentally tested. This is possible because our working substance consists of a strongly coupled CFT thermal state, which can be realized at the quantum critical point of a condensed matter system at finite temperature, such as high-temperature superconductors (see ref. 53 for a review). The Stirling efficiency in (13) and (21) provides a distinct prediction for a thermal CFT system dual to a black hole. As a result, our work offers a framework for experimentally testing holographic models in a condensed matter setting. In contrast, no direct experimental connection can be made with Johnson’s heat engines, as the theory evolves along the heat cycles, and because the bulk pressure and volume do not agree with those in the CFT. Furthermore, Johnson’s heat engines do not implement the CFT equation of state, which played a crucial role in our approach.

Conclusion

In this paper we proposed a way to construct heat engines in holographic field theories. The working substance can be modeled by a strongly coupled, large-N, conformally invariant thermal system that is dual to a black hole spacetime16,54. A crucial aspect of the holographic dictionary that we used is that the volume can be independently varied from the other thermodynamic variables. We computed the efficiencies of various idealized engines for (holographic) CFTs.

For future work there are many generalizations of our setup worth studying. We only described the simplest holographic heat engines as a proof of principle that our construction works. First, one could study other types of engines, ideally more realistic ones for which the efficiency of holographic systems can be experimentally tested. Second, we considered only field theories with conformal symmetry, but one could define heat engines for holographic field theories with different global symmetries, such as anisotropic scaling symmetry55,56. Third, one could compute the Stirling efficiency for specific CFTs at finite temperature and volume, for instance perturbatively at weak coupling, and compare with the holographic result. It would be particularly valuable to investigate the coupling dependence of the Stirling efficiency and to understand the physical origin behind the higher efficiency at weak coupling. Finally, one could study holographic engines for different types of black holes, such as charged or rotating black holes or black hole solutions to higher curvature gravity.

Data availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Code availability

Code sharing not applicable to this article as no compute codes were generated or used during the current study.

References

Wrangham, D.The Theory and Practice of Heat Engines (The University Press, 1942). https://books.google.nl/books?id=lGlMAAAAMAAJ.

Sandfort, J.Heat Engines. Science study series (Greenwood Press, 1979). https://books.google.nl/books?id=8tRZAAAAYAAJ.

Bharatha, S. & Truesdell, C. A.The Concepts and Logic of Classical Thermodynamics as a Theory of Heat Engines: Rigorously Constructed upon the Foundation Laid by S. Carnot and F. Reech (1989). https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-642-81077-0#toc.

Sonntag, R., Borgnakke, C. & Van Wylen, G.Fundamentals of Thermodynamics (Wiley, 2003). https://books.google.co.in/books?id=ZfNHPgAACAAJ.

Senft, J.Mechanical Efficiency of Heat Engines (Cambridge University Press, 2007). https://books.google.nl/books?id=2SqxYs59wDUC.

Carnot, S., Clapeyron, B. P. E. & Clausius, R. R.Reflections on the motive power of fire / and other papers on the second law of thermodynamics. (Dover Publications, New York, 1960).

Madakavil, A. S. & Kım, I. Heat engines running upon a non-ideal fluid model with higher efficiencies than upon the ideal gas model. International Journal of Thermodynamics 20, 16–24 (2017).

Karle, A. The thermomagnetic curie-motor for the conversion of heat into mechanical energy. International Journal of Thermal Sciences 40, 834–842 (2001).

Hooft, G.’t. Dimensional reduction in quantum gravity. Conf. Proc. C 930308, 284–296 (1993).

Susskind, L. The World as a hologram. J. Math. Phys. 36, 6377–6396 (1995).

Maldacena, J. M. The Large N limit of superconformal field theories and supergravity. Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 2, 231–252 (1998).

Gubser, S. S., Klebanov, I. R. & Polyakov, A. M. Gauge theory correlators from noncritical string theory. Phys. Lett. B 428, 105–114 (1998).

Witten, E. Anti-de Sitter space and holography. Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 2, 253–291 (1998).

Aharony, O., Gubser, S. S., Maldacena, J. M., Ooguri, H. & Oz, Y. Large N field theories, string theory and gravity. Phys. Rept. 323, 183–386 (2000).

Hawking, S. W. & Page, D. N. Thermodynamics of Black Holes in anti-De Sitter Space. Commun. Math. Phys. 87, 577 (1983).

Witten, E. Anti-de Sitter space, thermal phase transition, and confinement in gauge theories. Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 2, 505–532 (1998).

Geroch, R. Colloquium at princeton university (December 1971).

Bekenstein, J. D. Black holes and entropy. Phys. Rev. D 7, 2333–2346 (1973).

Sciama, D. Black holes and their thermodynamics. Vistas in Astronomy 19, 385–401 (1976).

Kaburaki, O. & Okamoto, I. Kerr black holes as a carnot engine. Phys. Rev. D 43, 340–345 (1991).

Landsberg, P. T.Thermodynamics and Black Holes, 99-146 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 1992). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-2420-1_3.

Opatrný, T. & Richterek, L. Black hole heat engine. American Journal of Physics 80, 66–71 (2012).

Curiel, E. Classical Black Holes Are Hot (2014). 1408.3691.

Bravetti, A., Gruber, C. & Lopez-Monsalvo, C. S. Thermodynamic optimization of a Penrose process: An engineers’ approach to black hole thermodynamics. Phys. Rev. D 93, 064070 (2016).

Prunkl, C. E. A. & Timpson, C. G. Black Hole Entropy is Thermodynamic Entropy (2019). 1903.06276.

Johnson, C. V. Holographic Heat Engines. Class. Quant. Grav. 31, 205002 (2014).

Johnson, C. V. An Exact Efficiency Formula for Holographic Heat Engines. Entropy 18, 120 (2016).

Chakraborty, A. & Johnson, C. V. Benchmarking black hole heat engines, I. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 27, 1950012 (2018).

Johnson, C. V. Holographic Heat Engines as Quantum Heat Engines. Class. Quant. Grav. 37, 034001 (2020).

Kastor, D., Ray, S. & Traschen, J. Enthalpy and the Mechanics of AdS Black Holes. Class. Quant. Grav. 26, 195011 (2009).

Dolan, B. P. The cosmological constant and the black hole equation of state. Class. Quant. Grav. 28, 125020 (2011).

Dolan, B. P. Pressure and volume in the first law of black hole thermodynamics. Class. Quant. Grav. 28, 235017 (2011).

Cvetic, M., Gibbons, G. W., Kubiznak, D. & Pope, C. N. Black Hole Enthalpy and an Entropy Inequality for the Thermodynamic Volume. Phys. Rev. D 84, 024037 (2011).

Kubiznak, D. & Mann, R. B. Black hole chemistry. Can. J. Phys. 93, 999–1002 (2015).

Kubiznak, D., Mann, R. B. & Teo, M. Black hole chemistry: thermodynamics with Lambda. Class. Quant. Grav. 34, 063001 (2017).

Mancilla, R. Generalized Euler Equation from Effective Action: Implications for the Smarr Formula in AdS Black Holes (2024). 2410.06605.

Bardeen, J. M., Carter, B. & Hawking, S. W. The Four laws of black hole mechanics. Commun. Math. Phys. 31, 161–170 (1973).

Hawking, S. W. Particle Creation by Black Holes. Commun. Math. Phys. 43, 199–220 (1975). [Erratum: Commun.Math.Phys. 46, 206 (1976)].

Visser, M. R. Holographic thermodynamics requires a chemical potential for color. Phys. Rev. D 105, 106014 (2022).

Cong, W., Kubiznak, D., Mann, R. B. & Visser, M. R. Holographic CFT phase transitions and criticality for charged AdS black holes. JHEP 08, 174 (2022).

Ahmed, M. B., Cong, W., Kubizňák, D., Mann, R. B. & Visser, M. R. Holographic Dual of Extended Black Hole Thermodynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 181401 (2023).

Ahmed, M. B., Cong, W., Kubiznak, D., Mann, R. B. & Visser, M. R. Holographic CFT phase transitions and criticality for rotating AdS black holes. JHEP 08, 142 (2023).

Gong, T.-F., Jiang, J. & Zhang, M. Holographic thermodynamics of rotating black holes. JHEP 06, 105 (2023).

Shaw, J. Comparing carnot, stirling, otto, brayton and diesel cycles. Transactions of the Missouri Academy of Science 42, 1–6 (2008).

Callen, H. B.Thermodynamics and an introduction to thermostatistics; 2nd ed. (Wiley, New York, NY, 1985). https://cds.cern.ch/record/450289.

Schroeder, D.An Introduction to Thermal Physics (Addison Wesley, 2000). https://books.google.nl/books?id=1gosQgAACAAJ.

Boles, M. A. & Çengel, Y. A.Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach, 7th Edition (2009). https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:57036601.

Verlinde, E. P. On the holographic principle in a radiation dominated universe (2000). hep-th/0008140.

Kutasov, D. & Larsen, F. Partition sums and entropy bounds in weakly coupled CFT. JHEP 01, 001 (2001).

Dolan, B. P. Bose condensation and branes. JHEP 10, 179 (2014).

Karch, A. & Robinson, B. Holographic Black Hole Chemistry. JHEP 12, 073 (2015).

Dolan, B. P.Where Is the PdV in the First Law of Black Hole Thermodynamics? (INTECH, 2012). 1209.1272.

Hartnoll, S. A., Lucas, A. & Sachdev, S. Holographic quantum matter (2016). 1612.07324.

Heemskerk, I., Penedones, J., Polchinski, J. & Sully, J. Holography from Conformal Field Theory. JHEP 10, 079 (2009).

Taylor, M. Lifshitz holography. Class. Quant. Grav. 33, 033001 (2016).

Cong, W., Kubizňák, D., Mann, R. B. & Visser, M. R. Holographic dictionary for Lifshitz and hyperscaling violating black holes (2024). 2410.16145.

Acknowledgements

M.R.V. is grateful to S. Borsboom, E. Curiel, T. Jacobson, K. Landsman, J. Pedraza, J. Uffink, W. Unruh, E. Verlinde, A. Wall and D. Wallace for useful discussions. He also thanks the participants at the Peyresq Physics 2025 conference, where this work was presented, for their interesting questions. This work is supported in part by the Spinoza Grant of the Dutch Science Organization (NWO) awarded to Klaas Landsman.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.R.V. came up with the project idea, supervised the research, verified and contributed calculations, and wrote the manuscript. N.L. did this as a summer research project, he performed most of the calculations, contributed to the conceptual framework, and made all the figures.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks Pankaj Chaturvedi and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lilani, N., Visser, M.R. Heat engines for scale invariant systems dual to black holes. Commun Phys 8, 379 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02291-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02291-y