Abstract

The quantum Rabi model (QRM) is a cornerstone in the study of light-matter interactions within cavity and circuit quantum electrodynamics (QED). It effectively captures the dynamics of a two-level system coupled to a single-mode resonator, serving as a foundation for understanding quantum optical phenomena in a great variety of systems. However, this model may produce inaccurate results for large coupling strengths, even in systems with high anharmonicity. Moreover, issues of gauge invariance further undermine its reliability. In this work, we introduce a renormalized QRM that incorporates the effective influence of higher atomic energy levels, providing a significantly more accurate representation of the system while still maintaining a two-level description. To demonstrate the versatility of this approach, we present two different examples: an atom in a double-well potential and a superconducting artificial atom (fluxonium qubit). This procedure opens new possibilities for precisely engineering and understanding cavity and circuit QED systems, which are highly sought-after, especially for quantum information processing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Effective low-energy models serve as foundational tools across diverse areas of physics, from describing many-body systems to characterizing light-matter interactions. By systematically eliminating terms that virtually excite particles into high-energy states through perturbative methods, they provide simplified yet accurate descriptions of low-energy physics while incorporating the influence of high-energy states through renormalized coupling terms. This approach has proven to be remarkably successful in various contexts. In condensed matter physics, notable examples include the effective spin Hamiltonian derived from the half-filled Hubbard model1,2 and the Kondo model3. The BCS theory of superconductivity4 and the theory of Josephson tunneling5 also rely heavily on effective low-energy descriptions. Beyond condensed matter, these techniques form the backbone of renormalization group methods in high-energy physics6.

In the context of light-matter interactions, low-energy effective Hamiltonians serve as indispensable tools, particularly in cavity and circuit quantum electrodynamics (QED)7,8,9,10. These models are typically derived by truncating the matter Hilbert space to a few relevant states while considering only one or a few modes of the electromagnetic resonator. The quantum Rabi model (QRM) stands as the quintessential example, describing the interaction between a two-level quantum emitter and a single-mode resonator. The QRM has provided deep insights into the physics of cavity and circuit QED systems, and has also been experimentally realized across diverse platforms, including superconducting qubits11,12, semiconductor quantum dots13,14, and trapped ions15.

The QRM accurately captures the physics of genuine two-level systems (i.e., spin-1/2 systems) and can serve as a reasonable approximation for multi-level systems truncated to their lowest two levels. However, there are regimes in which this two-level truncation fails to yield reliable results. In superconducting qubits like the transmon16, fluxonium17, or flux qubits18, truncating to a few energy levels is common but often inaccurate, especially when the anharmonicity of such systems is not sufficiently high. This limitation affects critical operations in quantum information19 such as readout, gate fidelities, and error correction, where precise modeling is essential. For instance, it has been shown that the readout of the transmon may ionize the system, leading to significant measurement errors20,21. Another factor that can compromise the accuracy of the two-level projection is the coupling strength. Recent experimental advances have demonstrated how cavity and circuit QED systems can reach non-perturbative regimes, such as the ultrastrong coupling (USC) and deepstrong coupling (DSC) regimes22,23. In these regimes, the standard QRM faces several fundamental issues, including the breakdown of gauge invariance24,25,26,27,28,29,30, complications in the theory of photodetection31,32, and challenges in treating open quantum systems33,34,35. In all these cases, the standard QRM may yield inaccurate description of the behavior of these devices, even in the presence of very high anharmonicity, thus calling for a more advanced model.

In this work, we propose a different perspective to address these issues through a renormalization procedure of the QRM, which we name Renormalized QRM (RQRM). In this effort, we were inspired by another well-established class of effective Hamiltonians widely adopted in the quantum theory of polaritons in solids, i.e., the Hopfield model36 and its few-mode generalizations, which describe the interaction between photons and collective matter excitations37. In particular, it has been demonstrated that accurately describing such experimental results across various systems and spectral ranges (see, e.g.,38,39) requires the introduction of an Hopfield model, where both the photonic resonance frequency and the light-matter coupling strength are renormalized by introducing a background dielectric function ϵ∞, which effectively accounts for the influence of higher-energy excitations. While renormalizing models of interacting bosons is simple due to their harmonic nature, the renormalization of the QRM is not as straightforward and remains largely unexplored.

In this work, we propose a systematic approach for developing RQRMs, which account for the influence of higher atomic energy levels. We first derive a general formulation of the RQRM applicable to both cavity and circuit QED systems. Extensive numerical simulations demonstrate that these RQRMs significantly improve accuracy across different coupling regimes and anharmonicities. We then explore the connections between our approach and other theoretical methods, in particular the resolvent technique. Additionally, we investigate two more aspects of the RQRM, i.e., its gauge invariance properties and its impact on physical observables. All the simulations are performed using the QuantumToolbox.jl package in Julia40.

Results

Renormalization of the Quantum Rabi Model in cavity QED

In the context of cavity QED, the QRM can be derived from a variety of different systems. As a pedagogical example, we start by considering a single electric dipole of charge q and mass m in a one-dimensional potential, which interacts with a single cavity mode with frequency ωc. In the electric-dipole approximation, the radiation wavelength is much larger than the atomic size, allowing us to neglect the spatial dependence of the vector potential, i.e. \({\hat{A}}={A}_{0}\left({\hat{a}}+{\hat{a}}^{{\dagger} }\right)\), where A0 is the zero-point fluctuation amplitude and \({\hat{a}}\left({\hat{a}}^{{\dagger} }\right)\) is the annihilation (creation) operator of the electromagnetic mode. The Hamiltonian in the dipole gauge reads41,42,43,44

where \(V({\hat{x}})\) is the atomic potential, \({\hat{x}}\) is the position operator and \({\hat{p}}\) is its conjugate momentum. For illustrative purposes, let us assume the case of a double-well potential \(V({\hat{x}})=\alpha {\hat{x}}^{4}-\beta {\hat{x}}^{2}\), with α, β > 0. By adjusting the parameter γ = mβ3/(ℏ2α2), we can tune the anharmonicity of the atomic system (see Supplementary Note 2). In particular, increasing γ leads to an increase in the ratios ωjk/ω10, where ωjk = ωj − ωk is the transition frequency between the j-th and k-th atomic levels.

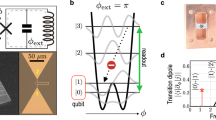

The standard QRM is obtained by truncating the atomic Hilbert space to the two lowest energy levels, which can be formally obtained by applying the projection operator \({\hat{P}}={\sum }_{n = 0}^{1} \vert n \rangle \langle n \vert\) to the full Hamiltonian (see Fig. 1a). It was shown that the QRM in the dipole gauge yields more accurate results compared to other possible gauges24. Therefore, the standard QRM Hamiltonian in the dipole gauge reads

where \({\bar{\omega }}_{10}={\omega }_{10}+({G}_{11}-{G}_{00})/{\omega }_{c}\) is the two-level resonance frequency renormalized by the \({\hat{x}}^{2}\) contribution, as \({G}_{jk}={\sum }_{l}{g}_{jl}{g}_{lk}\equiv {\omega }_{c}^{2}{q}^{2}{A}_{0}^{2}\langle j| {\hat{x}}^{2}| k\rangle /{\hslash }^{2}\). The terms \({g}_{jk}={\omega }_{c}q{A}_{0} \langle j| {\hat{x}}| k \rangle /\hslash\) are the light-matter coupling strengths and \({\hat{\sigma }}_{i}\) are the Pauli matrices. It is worth mentioning that the projection operation can be performed in various ways, leading to different variations of \({\bar{\omega }}_{10}\)24,26,45 (see Supplementary Note 1). The projection onto the unperturbed atomic states, as in Eq. (2), was recently shown to give more accurate results45.

We consider a single electron in a one-dimensional double-well potential, interacting with a cavity mode. a Standard procedure for obtaining the QRM from the full Hamiltonian, which consists of simply projecting in the low-energy subspace of the atomic eigenstates. b Renormalization of the QRM, which takes into account the interaction of photons with the higher-energy atomic levels. The renormalization procedure leads to the presence of new terms in the effective low-energy Hamiltonian, providing more accurate results, still treating the system as a two-level system. c Comparison of the eigenvalues in the full model (blue solid), the standard QRM (red dashed), and the RQRM (green dash-dotted). The RQRM provides more accurate results, even for strong coupling strengths. Parameters used: m = 1, γ = 60, and ωc = 3ω10. Mean square error of the eigenvalues of the first 5 excited states with respect to the full model, as a function of the anharmonicity parameter γ, for g/ωc = 0.8 (d) and g/ωc = 1.5 (e).

The standard QRM in Eq. (2) is well-known to closely match the full model when \({\bar{\omega }}_{10}\simeq {\omega }_{c}\) or for weak coupling strengths46,47. However, when these conditions are not met, its accuracy progressively worsens24.

To address these limitations, we now ask whether an improved version of the QRM can be developed, still within a two-level description, leading us to derive the RQRM. To this end, we first apply a Schrieffer-Wolff (SW) transformation3,48 to the full Hamiltonian in Eq. (1) (see “Methods”). The chosen transformation effectively treats the high-energy subspace as a perturbation, while the two-level subspace is handled non-perturbatively. A detailed discussion on the differences between this approach and traditional perturbative methods (as standard SW) is provided in the Supplementary Note 4. Indeed, this is possible because the higher-energy atomic levels are in the dispersive regime with the cavity, characterized by ∣gjk/(ωjk − ωc)∣ ≪ 1. This condition is satisfied for large enough atomic anharmonicities, which ensure that the transitions from the two lowest energy levels to the higher ones are not resonant with the cavity frequency, i.e. \(\left\vert {\omega }_{jk}\right\vert \gg {\omega }_{c}\). This approach allows for a fully non-perturbative treatment of the QRM, where the two-level system and the cavity field are effectively dressed by the contributions of higher atomic levels (see Fig. 1b). The resulting Hamiltonian reads

with \({\tilde{\omega }}_{10}={\bar{\omega }}_{10}+2{A}_{-}\) and \({\tilde{g}}_{01}={g}_{01}+{C}_{01}\) being the renormalized two-level resonance frequency and coupling strength, respectively. Here, A±, B±, C01 and D01 are the renormalization parameters defined in Eqs. (31)–(34) of the Methods Section, which depend on the microscopic details of the high energy states. These coefficients effectively account for the virtual transitions (up to the first order) between the two-level subspace and higher energy states. Notably, the RQRM in Eq. (3) provides a significantly more accurate description of the full system without requiring explicit enlargement of the Hilbert space.

Figure 1c shows a comparison of the eigenvalues of the first 5 excited states obtained from the full model \({\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{D}}}}\) (solid blue line), the standard QRM in Eq. (2) (red dashed), and the RQRM in Eq. (3) (green dash-dotted). The results confirm that the RQRM yields more accurate predictions than the standard QRM, which diverges at relatively high coupling strengths. The coupling strength \(g=\left\vert {g}_{01}\right\vert\) was varied through A0, which proportionally scales all the other coupling strengths gjk as well.

In Fig. 1d–e, we show the mean square error with respect to the full model \(\sigma =\sqrt{\mathop{\sum }_{j = 1}^{N}{({E}_{j}-{E}_{j}^{{{\rm{full}}}})}^{2}/N}\) of the eigenvalues of the first N = 5 excited states of the full light-matter system. We compare the QRM with the RQRM as a function of the anharmonicity parameter γ for two different coupling strengths, namely g/ωc = 0.8 and g/ωc = 1.5. We observe that the RQRM not only provides more accurate results, but also scales better with increasing anharmonicity.

It is interesting to observe that some of the renormalization terms in (3) become negligible for high anharmonicity, namely the B− and D01 terms (see Methods). Therefore, we can write a simplified version of the RQRM, which is given by

We can now perform a Bogolioubov transformation on the above Hamiltonian, which allows us to diagonalize the purely photonic terms. The resulting Hamiltonian reads

where \({\tilde{\omega }}_{c}=\sqrt{{\omega }_{c}^{2}-4{B}_{+}{\omega }_{c}}\) is the renormalized cavity frequency, and \({\hat{b}}-{\hat{b}}^{{\dagger} }=\sqrt{{\tilde{\omega }}_{c}/{\omega }_{c}}({\hat{a}}-{\hat{a}}^{{\dagger} })\). Remarkably, Eq. (5) preserves a QRM-like structure with renormalized frequencies and coupling, although in general providing slightly less accurate results, with respect to Eq. (3). In scenarios where the experimental setting is fixed, Eq. (5) (derived from Eq. (3)) shows that the standard QRM can still provide a reasonable fit of the obtained transition frequencies, since the fitted parameters include the renormalization effects through effective scaling factors that remain indistinguishable in experimental fits. However, as illustrated in Fig. 1c, such a fit procedure breaks down when varying the coupling strength g (or other system parameters). In such cases, the renormalization of the system frequencies, depending on g, plays a crucial role and must be incorporated for an accurate description, as is done in the RQRM.

Renormalization of the Quantum Rabi Model in Circuit QED

Superconducting circuits are a promising platform for quantum technologies, as they allow the realization of ultrastrong and even deepstrong coupling between artificial atoms and electromagnetic modes9,49,50,51,52. In this context, to illustrate our approach, we focus on a specific example involving the fluxonium qubit. In particular, we focus our attention on the study of a fluxonium-resonator system17,53,54 represented in Fig. 2a, bearing in mind that the same procedure can be applied to other circuits, once the corresponding Hamiltonian is derived. The fluxonium qubit is characterized by higher anharmonicity when compared to other devices, such as the transmon qubit, making it an ideal candidate for the study of the renormalization of the QRM. Specifically, the system under study is composed by a Josephson junction with energy EJ and capacitance C1 in parallel with a inductance L1 to which is added in series an L2C2 resonator. An external flux ϕext is threading the loop formed by the Josephson junction and the inductance L1. The corresponding Hamiltonian is derived by the usual quantization procedure9,55 (see Supplementary Note 3), resulting in

where \({\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{flux}}}}\) and \({\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{res}}}}\) are the fluxonium and resonator bare Hamiltonians, given by

respectively, with ϕ0 = ℏ/2e being the reduced flux quantum and ϕi (Qi) the flux (charge) node variables. Equation (8) can be rewritten as \({\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{res}}}}=\hslash {\omega }_{c}{\hat{a}}^{{\dagger} }{\hat{a}}\), with bosonic operator \({\hat{a}}=({\omega }_{c}{\hat{\phi }}_{2}+i{\hat{Q}}_{2})/{\omega }_{c}{\phi }_{{{\rm{zpf}}}}\), \({\omega }_{c}=1/\sqrt{{L}_{2}{C}_{2}}\) and \({\phi }_{{{\rm{zpf}}}}=\sqrt{\hslash /2{C}_{2}{\omega }_{c}}\).

a Schematical representation of a fluxonium qubit, defined by a Josephson junction with energy EJ and a capacitance C1 in parallel with a inductance L1, galvanically coupled to a LC resonator. First eigenstates of the fluxonium qubit for ϕext = π (b) and ϕext = 3π/4 (c). In the latter, the parity symmetry is broken. In both cases, the dashed black line correspond to the potential. Comparison of the eigenvalues in the full model (solid blue line), the standard QRM (dashed green line), and the RQRM (dotted red line), as a function of the normalized coupling g/ωc, and for ϕext = π (d) and ϕext = 49π/50 (e). As for the real atoms case, the renormalization gives better results. f Time evolution of \(\langle i(\hat{a}-{\hat{a}}^{{\dagger} })\rangle\) after a π-pulse on the qubit and in the case of ϕext = 49π/50. The renormalized QRM provides a better agreement with the full model. The parameters used in this Figure are: EC = q2/(2C1) = 2.5 GHz, EL = (ℏ/2q)2/L1 = 0.5 GHz, EJ = 9 GHz, and ωc = 3ω10, which reproduce typical experimental values for fluxonium qubits17,76. For the π-pulse, we used ωdr = E10, σdr = 50/(E21 − E10) and t0 = 3σdr (see Methods).

The Hamiltonian in Eq. (6) exhibits a striking similarity to the cavity-QED Hamiltonian in Eq. (1). Indeed, it can be shown that Eq. (1) can be obtained by performing a minimal coupling replacement on the photonic operators defined by \({\hat{a}}\to {\hat{a}}+iq{A}_{0}{\hat{x}}/\hslash\)30,56. Analogously, Eq. (6) presents a minimal coupling replacement on the resonator variables. The primary distinction between the two cases lies in the nature of the coupling. In the former, the interaction term is of the form coordinate-momentum \(({\hat{x}}{\hat{E}})\), while in the latter, it involves the two fluxes, which correspond to the generalized coordinates in the so-called flux gauge. Therefore, the two Hamiltonians are simply linked by a unitary transformation \({\hat{T}}=\exp \left(i\pi {\hat{a}}^{{\dagger} }{\hat{a}}/2\right)\) (see Methods). Consequently, the same procedure used in the previous section can be applied here.

First, we derive the Hamiltonian for the QRM by projecting the full Hamiltonian in the low-energy subspace of the fluxonium qubit, which results in

where

with \({\phi }_{ij}= \langle i \vert {\hat{\phi }}_{1}\vert j \rangle\) and \({\Phi }_{ij}=\langle i\vert {\hat{\phi }}_{1}^{2}\vert j \rangle ={\sum }_{k}{\phi }_{ik}{\phi }_{kj}\). Alongside the renormalized qubit frequency \({\bar{\omega }}_{10}\) (previously defined), three additional terms emerge in Eq. (9) due to the breaking of parity symmetry, originating from the external flux ϕext. These additional terms vanish when ϕext = kπ (with \(k\in {\mathbb{Z}}\)), where the symmetry is restored. The third term arises from the projection of \({\hat{\phi }}_{1}^{2}\) onto the unperturbed fluxonium states, similarly to what discussed in the cavity QED case.

Following our approach, we can apply the renormalization procedure to the fluxonium-resonator system. After performing the SW transformation (see Methods), the renormalized Hamiltonian is given by

with \({\tilde{\omega }}_{10}={\bar{\omega }}_{10}+2{A}_{-}\) and \({\tilde{g}}_{jk}={g}_{jk}+{C}_{jk}\). It is worth noting that all the coefficients are the same as those in the natural atom case Eq. (3), defined explicitly in the Methods Equations ((31)–(34)). The Hamiltonian in Eq. (11) is the Circuit QED version of the RQRM.

Figure 2b, c shows the shapes of the fluxonium potential and the respective eigenstates for the symmetric (b) and asymmetric (c) cases, corresponding to ϕext = π and ϕext = 3π/4, respectively. Figure 2d, e shows the comparison of the eigenvalues of the first 5 excited states obtained from the full model (blue solid), the standard QRM (red dashed), and the RQRM (green dash-dotted), as a function of the normalized coupling g/ωc, and for both the symmetric (d) and asymmetric (e) cases. Figure 2f shows the time evolution of the expectation value \(\langle i({\hat{a}}-{\hat{a}}^{{\dagger} })\rangle\), considering the system initially in its ground state and applying a π-pulse on the qubit, in presence of symmetry breaking (see Methods). These results demonstrate that the RQRM provides significantly more accurate results than the standard QRM, even in absence of parity symmetry in the anharmonic potential [Fig. 2e]. Furthermore, the RQRM performs better also in describing the system dynamics and its impact on the observables. In particular, this aspect will be further examined in the following sections.

Higher-order corrections of the effective Hamiltonians

The effective Hamiltonians both in cavity [Eq. (3)] and circuit QED [Eq. (11)] are obtained by performing a SW transformation up to the second order in the gjk/(ωjk − ωc) expansion. This leads to an improvement in the accuracy, as can be seen from Fig. 1c–e and Fig. 2d–f. One may wonder whether higher-order corrections can further improve the accuracy of the renormalization procedure. Notice that, even expanding the series of the SW to higher orders, the original eigenvalues are not recovered because the transformation \({\hat{H}}\to {e}^{-{\hat{S}}}{\hat{H}}{e}^{\hat{S}}\) preserves the spectrum of the Hamiltonian only if no projection is performed.

In order to quantify the impact of higher-order corrections on the renormalization, here we adopt the resolvent method57,58,59. In particular, we focus on the cavity QED model, but the same analysis can be applied to other cases. Starting from the eigenvalue equation of the full Hamiltonian in the dipole gauge \({\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{D}}}}\left\vert {\psi }_{{{\rm{D}}}}\right\rangle =E\left\vert {\psi }_{{{\rm{D}}}}\right\rangle\), it is possible to derive an eigenvalue equation for an effective Hamiltonian, defined in the projected subspace, as

where E is the same eigenvalue as in the full case. The energy-dependent effective Hamiltonian is given by

where \({\hat{Q}}={\hat{I}}-{\hat{P}}\) is the projector on the subspace complementary to \({\hat{P}}\).

Equation (12) gives the exact eigenvalues in the low-energy subspace. However, the implicit dependence of the effective Hamiltonian on the eigenvalue E may make the problem challenging. Nonetheless, the resolvent \({\hat{G}}_{{{\rm{QQ}}}}(E)\equiv {(E-{\hat{Q}}{\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{D}}}}{\hat{Q}})}^{-1}\) can be expanded in series by using the property \({(A-B)}^{-1}={A}^{-1}{\sum }_{n = 0}^{\infty }{(B{A}^{-1})}^{n}\), with \(A=-{\hat{Q}}{\hat{H}}_{{0}^{{\prime} }}{\hat{Q}}\) and \(B={\hat{Q}}{\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{int,D}}}}^{{{\rm{H}}}}{\hat{Q}}-E\). Here, \({\hat{H}}_{{0}^{{\prime} }}\) and \({\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{int,D}}}}\) are defined in Eqs. (22), (25), respectively. The series can be truncated up to the M-th order, obtaining a polynomial eigenvalue problem, which can be solved numerically60. A more detailed discussion of this method can be found in the Supplementary Note 4. In the limit of M → ∞, we recover the exact solution.

Figure 3 shows the mean square error of the first 5 excited states with respect to the full model, as a function of the order of the resolvent expansion. We observe that the error decreases exponentially with M, showing the convergence of the method. As a comparison, we plot also the QRM and RQRM errors. While the resolvent method provides higher accuracy, it remains purely numerical. In contrast, the SW approach developed here enables the analytical derivation of an effective Hamiltonian.

Mean square error of the first 5 excited states with respect to the full model, as a function of the order of the resolvent expansion. The error decreases exponentially with the order of the series M, showing the convergence of the resolvent method. To make a comparison, we show also the QRM and RQRM errors. We used the same parameters as in Fig. 1c with g/ωc = 0.8.

Gauge invariance of the renormalized Quantum Rabi Model

Here, we investigate the gauge properties of the RQRM. Models that do not preserve gauge invariance may lead to wrong predictions. One of the most striking examples is the Dicke model, where a collection two-level systems coupled to light was predicted to undergo a second-order phase transition to a photon condensate61,62,63,64,65,66. However, it was later shown that this phase transition is actually forbidden if the so-called \({\hat{{{\bf{A}}}}}^{2}\) term, which restores the gauge invariance, is not neglected67,68. More generally, the photon condensation has been shown to be forbidden by the gauge invariance itself, both in truncated systems69 and in the full Hilbert space70,71,72. In the following, we will derive the RQRM in a gauge invariant form, and we will discuss the implications of this result.

As it is well-known25,45, in the full Hilbert space, we can introduce a gauge parameter η which gives rise to a continuous family of η-dependent Hamiltonians \({\hat{H}}^{(\eta )}\) interpolating between the Coulomb and the dipole gauges, spanned by the unitary transformation \({\hat{U}}^{(\eta )}=\exp (i\eta q{\hat{x}}{\hat{A}}/\hslash )\). Explicitly, for a spatially constant vector potential, we have

where \({\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{a}}}}={\hat{p}}^{2}/(2m)+V({\hat{x}})\) and \({\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{ph}}}}=\hslash {\omega }_{c}{\hat{a}}^{{\dagger} }{\hat{a}}\) are the bare atomic and photonic Hamiltonians. For η = 0, we recover the usual minimal coupling replacement in the Coulomb gauge Hamiltonian \(({\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{C}}}}={\hat{H}}^{(0)})\), whereas for η = 1 we obtain the dipole gauge Hamiltonian \(({\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{D}}}}={\hat{H}}^{(1)})\), showing that in this case the minimal coupling is applied to the photonic term (notice that \({\hat{U}}^{(0)}={\hat{I}}\)).

When truncating to the atomic low-energy subspace, gauge invariance breaks down, as \({\hat{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{{{\rm{C}}}}={\hat{P}}{\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{C}}}}{\hat{P}}\) and \({\hat{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{{{\rm{D}}}}={\hat{P}}{\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{D}}}}{\hat{P}}\) are no longer linked by any unitary transformation. This issue was resolved by applying the minimal coupling replacement directly in the projected Hilbert space26,27,29. Indeed, analogously to the case of the full models, a unitary transformation in the truncated Hilbert space \({\hat{{{\mathcal{U}}}}}=\exp [iq{\hat{P}}{\hat{x}}{\hat{P}}{\hat{A}}]=\exp [i{g}_{01}{\hat{\sigma }}_{x}({\hat{a}}+{\hat{a}}^{{\dagger} })/{\omega }_{c}]\) is defined, which interpolates between the Coulomb and dipole gauges as

where \({\hat{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{{{\rm{a}}}}=\hslash {\omega }_{10}{\hat{\sigma }}_{z}/2\). This procedure restores a discrete form of gauge invariance directly within the truncated space28.

Following the same reasoning, the RQRM in Eq. (5) can be interpreted in a gauge-preserving form as

where the renormalized atomic and photonic Hamiltonians are

and the renormalized η-dependent unitary operator is

Consequently, the η-interpolated RQRM becomes

Figure 4 shows the mean square error on the energies of the first five excited states, compared to those obtained from the full model as a function of the gauge parameter η, for g/ωc = 0.8. While the standard QRM breaks gauge invariance (with dipole gauge being the most accurate), the QRM \({\hat{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}^{(\eta )}\) and RQRM \({\hat{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}^{{\prime} (\eta )}\) ensure gauge invariance, with the latter providing a better accuracy.

Mean square error of the eigenvalues of the first 5 excited states with respect to the full model, as a function of the gauge parameter η, for g/ωc = 0.8, m = 1, γ = 60, and ωc = 3ω10. The QRM (red dashed) breaks gauge invariance, showing that the dipole gauge (η = 1) is the most accurate. On the other hand, the RQRM \({\hat{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}^{{\prime} (\eta )}\) (green dotted) in Eq. (19) is not only gauge invariant but also provides more accurate results. For completeness, we also compare these models with the gauge-preserving QRM \({\hat{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}^{(\eta )}\) (blue dash-dotted) in Eq. (15), which, however, does not take into account the renormalization of the higher energy levels.

The effect of the renormalization on the observables and matrix elements

In the previous sections, we have established that the renormalization significantly improves the energy spectrum of the system. However, a comprehensive understanding requires also examining how renormalization influences other physical quantities. In the following, we analyze how the renormalization affects both photonic and atomic observables and matrix elements in the cavity QED case.

Figure 5a shows the expectation value \(\langle {\psi }_{3}\vert {({\hat{a}}+{\hat{a}}^{{\dagger} })}^{2}\vert {\psi }_{3}\rangle\) on the third excited state, as a function of the coupling strength g/ωc. The RQRM provides more accurate predictions, even for large coupling strengths. A similar improvement is observed in Fig. 5b, which displays the matrix element \(| \langle {\psi }_{0}| ({\hat{a}}+{\hat{a}}^{{\dagger} })| {\psi }_{2}\rangle |\), between the ground and the second excited states. Although not directly observable, this quantity is closely related to dissipation rates and line broadening, which play an important role in experimental realizations33,34,73.

a Expectation value of \({(\hat{a}+{\hat{a}}^{{\dagger} })}^{2}\) (a) on the third excited state of the full model (blue solid), QRM (red dashed) and the RQRM (green dash-dotted), as a function of the coupling strength g/ωc. The RQRM provides more accurate results, even for strong coupling strengths. Matrix elements of the cavity field \(\hat{a}+{\hat{a}}^{{\dagger} }\) (b) and the atomic position operator \(\hat{x}\) (c) between the ground and the second excited, as a function of g/ωc. While in the panel (b) the renormalization improves the accuracy, in the panel c it does not. This behavior can be explained by the infidelity of the second excited state of the RQRM with respect to the QRM, as a function of g/ωc, for both the reduced density matrix of the cavity (solid light blue) and the atom (dashed orange) (d).

Interestingly, Fig. 5c reveals that renormalization does not improve the accuracy of the matrix element \(| \langle {\psi }_{0}| {\hat{x}}| {\psi }_{2}\rangle |\). This behavior can be in part understood by observing Fig. 5d, which shows the infidelity \(1-{{\mathcal{F}}}\) of \(\vert {\psi }_{2}\rangle\) between the standard QRM and the RQRM, for the reduced density matrices of the cavity and atom, as a function of g/ωc. More specifically, the fidelity \({{\mathcal{F}}}\) is calculated as:

where \({\hat{\rho }}_{\mu }\) and \({\hat{\sigma }}_{\mu }\) are the reduced density matrices for the renormalized and standard QRM, respectively, with μ indicating either the cavity or atom subsystems. The plot reveals that the renormalization does not significantly change the atomic subsystem, compared to the standard QRM, explaining the behavior in Fig. 5c. On the contrary, the degrees of freedom of the cavity are strongly affected by the renormalization to more accurately reproduce the full model. In fact, the operator \({\hat{x}}\) includes contributions from higher energy levels that cannot be reproduced by the corresponding operator projected into a two-level Hilbert space. Furthermore, the two-level truncation inherently discretizes space28, introducing intrinsic inaccuracies in atomic observables that persist even after renormalization. These differences explain the contrasting behaviors observed in panels (a-b) and (c).

Discussions

In this work, we have demonstrated how renormalizing the QRM by taking into account higher atomic energy levels leads to more accurate predictions, while maintaining analytical and computational tractability. This improvement is particularly evident in the energy spectrum and expectation values of observables, where the RQRM shows better agreement with the full model compared to the standard QRM. We have also derived an RQRM preserving gauge invariance, a fundamental physical requirement often violated by truncated models. As shown in the fluxonium-qubit example, renormalized low-energy effective Hamiltonians can also accurately capture symmetry-breaking effects while preserving the simplicity of a two-level description. This makes it especially useful for studying quantum information protocols19, particularly in the context of superconducting systems9,49,50,51, where precise modeling of light-matter interactions is essential for predicting gate fidelities and decoherence effects.

We expect renormalization to have an even stronger impact on systems characterized by multi-dimensional potentials, such as flux-qubits18. Additionally, this procedure can be extended to other systems in cavity and circuit QED, e.g., systems with multiple non-linear components, or generalized models incorporating three, four, or more low-energy levels while still accounting for the influence of higher-energy states. Such extensions could be particularly valuable for systems where intermediate energy levels play a significant role, such as in Lambda or ladder-type atomic configurations commonly encountered in quantum optics74,75. Additionally, this renormalization approach could be extended to multi-mode cavity systems. This method could also be adapted for other hybrid quantum systems, e.g., optomechanical devices. In each case, the key step is to identify the relevant high-energy states and their influence on low-energy dynamics through virtual processes. Finally, we observe that further study is required to increase the accuracy of matrix elements of observables of the matter component.

Methods

Derivation of the effective Hamiltonian in Cavity QED

In this section, we first present the derivation of the cavity QED Hamiltonian of the main text, while in the next section we focus on the circuit QED case.

We consider the full Hamiltonian expressed in the dipole gauge in Eq. (1), as the perturbative expansion of the SW transformation is not suitable in the Coulomb gauge (see Supplementary Note 1). To facilitate the application of this procedure, we divide the full Hamiltonian in dipole gauge into three terms:

where

is the quasi-free Hamiltonian, which includes the high-energy frequencies renormalized by the \({\hat{x}}^{2}\) term, i.e.

The light-matter interaction is divided into the low-energy and high-energy terms given by, respectively

where \({{\mathcal{S}}}={\{0,1\}}^{2}\) is the low-energy manifold corresponding to the ground and first excited atomic states, and \(\overline{{{\mathcal{S}}}}={{\mathbb{N}}}^{2}\setminus {{\mathcal{S}}}\) is its complementary subspace. This implies that \({\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{int,D}}}}^{{{\rm{L}}}}\) has elements only in the low-energy subspace, while \({\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{int,D}}}}^{{{\rm{H}}}}\) contains elements in the high-energy subspace.

While the low-energy interaction term cannot be treated perturbatively, the high-energy interaction term \({\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{int,D}}}}^{{{\rm{H}}}}\) can be regarded as a perturbation on \({\hat{H}}_{{0}^{{\prime} }}\). Specifically, we assume that the cavity and the high-energy transitions are in the dispersive regime with the cavity, i.e. \(\left\vert {g}_{jk}/({\omega }_{jk}^{{\prime} }-{\omega }_{c})\right\vert \ll 1\). Under this condition, we employ the SW transformation to derive the effective influence of the high-energy terms on the low-energy subspace.

To this end, we introduce the generator of the SW transformation, \({\hat{S}}\), which, by using the Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff lemma, satisfies

By truncating the series to the second order in the perturbation, and subsequently projecting into the two-level subspace, we obtain the effective Hamiltonian in the truncated Hilbert space

with \({\hat{P}}={\sum }_{j = 0}^{1}\vert j \rangle \langle j \vert\) the projector onto the two-level subspace. We point out that the series is consistently truncated up to the second order in A0, which is the parameter varied in the plots of the main text.

The generator \({\hat{S}}\) is defined such that \(\left[{{\hat{H}}}_{{0}^{{\prime} }},{\hat{S}}\right]=-{{\hat{H}}}_{{{\rm{int,D}}}}^{{{\rm{H}}}}\), in order to eliminate the high-energy terms from the effective Hamiltonian. This leads to the following expression for the generator

and, consequently, the effective Hamiltonian becomes

We notice that \({{\hat{P}}}\left[{{\hat{H}}}_{{{\rm{int,D}}}}^{{{\rm{L}}}},{{\hat{S}}}\right]{{\hat{P}}}=0\), because \({{\hat{H}}}_{{{\rm{int,D}}}}^{{{\rm{L}}}}\) is only composed of terms acting on the two-level subspace, and \({\hat{S}}\) is composed of terms acting only on its complementary subspace, resulting in a first-order zero contribution in the low-energy subspace. Finally, by explicitly expanding the other terms, we get the following effective Hamiltonian, up to an identity term

where A± = A11 ± A00 and B± = B11 ± B00, with the following coefficients:

The effective Hamiltonian Eq. (30), which coincides with Eq. (3) upon the introduction of the renormalized parameters, describes the low-energy physics of the system in the dipole gauge. However, many of these terms become negligible for increasing anharmonicity. Specifically, we notice that Djk scales as \({g}_{jl}{g}_{kl}^{2}/{\omega }_{jl}^{2}\), where j and k are states in the low-energy subspace and l belongs to the high-energy subspace, while the remaining coefficients scale linearly. Consequently, Djk approaches zero more rapidly compared to the other coefficients. Furthermore, although the individual terms Bjj are non-negligible, their difference B11 − B00 can be neglected as it also scales quadratically with the nonlinearity. With these considerations, we finally get the reduced effective Hamiltonian Eq. (4).

Derivation of the effective Hamiltonian in circuit QED

We first rewrite the Hamiltonian in Eq. (6) by using the bosonic operator \({\hat{a}}\) for the bare mode of the harmonic resonator in Eq. (8), while employing the unperturbed states of the fluxonium Hamiltonian in (7). Therefore, the resulting Hamiltonian reads

By the introduction of the coupling strengths gjk and Gjk as in Eq. (10) of the main text, the Hamiltonian in Eq. (35) reads

Both the generator \({\hat{S}}\) of the SW transformation and the effective Hamiltonian can be determined by using a key observation: Hamiltonian in Eq. (36) is structurally equivalent to the dipole gauge Hamiltonian of the cavity QED case in Eq. (21), following the application of the unitary transformation \({\hat{T}}=\exp \left(i\pi {{\hat{a}}}^{{\dagger} }{\hat{a}}/2\right)\) as \({\hat{T}}{{\hat{H}}}_{{{\rm{D}}}}{{\hat{T}}}^{{\dagger} }\). This transformation interchanges the roles of the position and momentum operators of the resonator, as the only formal difference between the two Hamiltonians lies in the nature of the coupling, as already mentioned in the main text. Therefore, upon the application of the unitary transformation \({\hat{T}}\) to Eq. (28), the SW generator for the Hamiltonian of a fluxonium-resonator circuit is

Hence, following the same procedure as in the cavity QED case presented in the previous section, the renormalized Hamiltonian is given by

where \({\tilde{g}}_{jk}={g}_{jk}+{C}_{jk}\) and the coefficients are identical to those of natural atoms, as no a priori selection rules have been employed in the derivation of the coefficients. However, in evaluating the Hamiltonian in Eq. (30), it has been taken into account that the parity of the potential leads to the vanishing of the coupling constants gjk between states of the same parity. Consequently, Gjk vanishes between states of different parity. On the other hand, in the circuit QED case, where such symmetry can be broken, several additional terms appear in the renormalized Hamiltonian in Eq. (38).

Simulation of the π-pulse

To simulate the π-pulse time evolution in Fig. 2f, the wavefunction of the full system evolves according to the Schrödinger equation

with \({\hat{H}}(t)={{\hat{H}}}_{{{\rm{fr}}}}+{{\hat{H}}}_{{{\rm{dr}}}}(t)\) and

Analogously, in the case of the QRM and RQRM, the time evolution is generated by \({\hat{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{{{\rm{fr}}}}+{\hat{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{{{\rm{dr}}}}(t)\) and \({\hat{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{{{\rm{fr}}}}^{{{\rm{eff}}}}+{\hat{{{\mathcal{H}}}}}_{{{\rm{dr}}}}(t)\), respectively, with

Data availability

Data produced in the current study were generated using custom code (see Code Availability statement).

Code availability

The source code generated during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Takahashi, M. Half-filled Hubbard model at low temperature. J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 10, 1289–7301 (1977).

MacDonald, A. H., Girvin, S. M. & Yoshioka, D. \(\frac{t}{U}\) expansion for the Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. B 37, 9753–9756 (1988).

Schrieffer, J. R. & Wolff, P. A. Relation between the Anderson and Kondo Hamiltonians. Phys. Rev. 149, 491–492 (1966).

Bardeen, J., Cooper, L. N. & Schrieffer, J. R. Theory of superconductivity. Phys. Rev. 108, 1175–1204 (1957).

Josephson, B. D. Possible new effects in superconductive tunnelling. Phys. Lett. 1, 251–253 (1962).

Wilson, K. G. The renormalization group and critical phenomena. Rev. Mod. Phys. 55, 583–600 (1983).

Brune, M. et al. Quantum Rabi oscillation: A direct test of field quantization in a cavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 1800–1803 (1996).

Haroche, S. Nobel Lecture: Controlling photons in a box and exploring the quantum to classical boundary. Rev. Mod. Phys. 85, 1083–1102 (2013).

Blais, A., Grimsmo, A. L., Girvin, S. M. & Wallraff, A. Circuit quantum electrodynamics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 93, 025005 (2021).

De Bernardis, D., Mercurio, A. & De Liberato, S. Tutorial on nonperturbative cavity quantum electrodynamics: is the Jaynes–Cummings model still relevant? J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 41, C206 (2024).

Wallraff, A. et al. Strong coupling of a single photon to a superconducting qubit using circuit quantum electrodynamics. Nature 431, 162–167 (2004).

Gu, X., Kockum, A. F., Miranowicz, A., Liu, Y.-x & Nori, F. Microwave photonics with superconducting quantum circuits. Phys. Rep. 718, 1–102 (2017).

Reithmaier, J. P. et al. Strong coupling in a single quantum dot–semiconductor microcavity system. Nature 432, 197–200 (2004).

Lodahl, P., Mahmoodian, S. & Stobbe, S. Interfacing single photons and single quantum dots with photonic nanostructures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 347–400 (2015).

Leibfried, D., Blatt, R., Monroe, C. & Wineland, D. Quantum dynamics of single trapped ions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 75, 281–324 (2003).

Koch, J. et al. Charge-insensitive qubit design derived from the Cooper pair box. Phys. Rev. A 76 (2007).

Manucharyan, V. E., Koch, J., Glazman, L. I. & Devoret, M. H. Fluxonium: Single cooper-pair circuit free of charge offsets. Science 326, 113–116 (2009).

Mooij, J. E. et al. Josephson persistent-current qubit. Science 285, 1036–1039 (1999).

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information: 10th Anniversary Edition (Cambridge University Press, 2012). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511976667.

Shillito, R. et al. Dynamics of transmon ionization. Phys. Rev. Appl. 18. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevApplied.18.034031 (2022).

Dumas, M. F. et al. Measurement-Induced Transmon Ionization. Phys. Rev. X 14. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevX.14.041023 (2024).

Forn-Díaz, P., Lamata, L., Rico, E., Kono, J. & Solano, E. Ultrastrong coupling regimes of light-matter interaction. Rev. Mod. Phys. 91, 025005 (2019).

Frisk Kockum, A., Miranowicz, A., De Liberato, S., Savasta, S. & Nori, F. Ultrastrong coupling between light and matter. Nat. Rev. Phys. 1, 19–40 (2019).

De Bernardis, D., Pilar, P., Jaako, T., De Liberato, S. & Rabl, P. Breakdown of gauge invariance in ultrastrong-coupling cavity QED. Phys. Rev. A 98, 053819 (2018).

Stokes, A. & Nazir, A. Gauge ambiguities imply Jaynes-Cummings physics remains valid in ultrastrong coupling QED. Nat. Commun. 10, 499 (2019).

Di Stefano, O. et al. Resolution of gauge ambiguities in ultrastrong-coupling cavity quantum electrodynamics. Nat. Phys. 15, 803–808 (2019).

Taylor, M. A. D., Mandal, A., Zhou, W. & Huo, P. Resolution of gauge ambiguities in molecular cavity quantum electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 123602 (2020).

Savasta, S. et al. Gauge principle and gauge invariance in two-level systems. Phys. Rev. A 103, 053703 (2021).

Dmytruk, O. & Schiró, M. Gauge fixing for strongly correlated electrons coupled to quantum light. Phys. Rev. B 103, 075131 (2021).

Settineri, A. et al. Gauge freedom, quantum measurements, and time-dependent interactions in cavity QED. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 023079 (2021).

Ridolfo, A., Leib, M., Savasta, S. & Hartmann, M. J. Photon blockade in the ultrastrong coupling regime. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 193602 (2012).

Mercurio, A. et al. Regimes of cavity QED under incoherent excitation: From weak to deep strong coupling. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 023048 (2022).

Beaudoin, F., Gambetta, J. M. & Blais, A. Dissipation and ultrastrong coupling in circuit QED. Phys. Rev. A 84, 043832 (2011).

Settineri, A. et al. Dissipation and thermal noise in hybrid quantum systems in the ultrastrong-coupling regime. Phys. Rev. A 98, 053834 (2018).

Mercurio, A. et al. Pure dephasing of light-matter systems in the ultrastrong and deep-strong coupling regimes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 123601 (2023).

Hopfield, J. J. Theory of the contribution of excitons to the complex dielectric constant of crystals. Phys. Rev. 112, 1555–1567 (1958).

Mills, D. & Burstein, E. Polaritons: the electromagnetic modes of media. Rep. Prog. Phys. 37, 817 (1974).

Henry, C. H. & Hopfield, J. J. Raman scattering by polaritons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 15, 964–966 (1965).

Fröhlich, D., Mohler, E. & Wiesner, P. Observation of exciton polariton dispersion in CuCl. Phys. Rev. Lett. 26, 554–556 (1971).

Mercurio, A. et al. QuantumToolbox.jl: An efficient Julia framework for simulating open quantum systems. Quantum 9, 1866 (2025).

Power, E. A. & Zienau, S. Coulomb gauge in non-relativistic quantum electro-dynamics and the shape of spectral lines. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A, Math. Phys. Sci. 251, 427–454 (1959).

Woolley, R. G. Molecular quantum electrodynamics. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A. Math. Phys. Sci. 321, 557–572 (1971).

Babiker, M. & Loudon, R. Derivation of the Power-Zienau-Woolley Hamiltonian in quantum electrodynamics by gauge transformation. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A. Math. Phys. Sci. 385, 439–460 (1983).

Cohen-Tannoudji, C., Dupont-Roc, J. & Grynberg, G.Lagrangian and Hamiltonian Approach to Electrodynamics, The Standard Lagrangian and the Coulomb Gauge, chap. 2, 79–168 (John Wiley and Sons, Ltd, 1997).

Arwas, G., Manucharyan, V. E. & Ciuti, C. Metrics and properties of optimal gauges in multimode cavity QED. Phys. Rev. A 108, 023714 (2023).

Lamb, W. E. Fine structure of the hydrogen atom. III. Phys. Rev. 85, 259–276 (1952).

Bassani, F., Forney, J. J. & Quattropani, A. Choice of gauge in two-pho ton transitions: 1s − 2s transition in atomic hydrogen. Phys. Rev. Lett. 39, 1070–1073 (1977).

Bravyi, S., DiVincenzo, D. P. & Loss, D. Schrieffer–Wolff transformation for quantum many-body systems. Ann. Phys. 326, 2793–2826 (2011).

Niemczyk, T. et al. Circuit quantum electrodynamics in the ultrastrong-coupling regime. Nat. Phys. 6, 772–776 (2010).

Yoshihara, F. et al. Superconducting qubit–oscillator circuit beyond the ultrastrong-coupling regime. Nat. Phys. 13, 44–47 (2017).

Krantz, P. et al. A quantum engineer’s guide to superconducting qubits. Appl. Phys. Rev. 6 https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5089550 (2019).

Yoshihara, F., Ashhab, S., Fuse, T., Bamba, M. & Semba, K. Hamiltonian of a flux qubit-LC oscillator circuit in the deep–strong-coupling regime. Sci. Rep. 12 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-10203-1 (2022).

Manucharyan, V. E., Baksic, A. & Ciuti, C. Resilience of the quantum Rabi model in circuit QED. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 50, 294001 (2017).

Nguyen, L. B. et al. High-coherence fluxonium qubit. Phys. Rev. X 9 https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevX.9.041041 (2019).

Vool, U. & Devoret, M. Introduction to quantum electromagnetic circuits. Int. J. Circuit Theory Appl. 45, 897–934 (2017).

Garziano, L., Settineri, A., Di Stefano, O., Savasta, S. & Nori, F. Gauge invariance of the Dicke and Hopfield models. Phys. Rev. A 102, 023718 (2020).

Cohen-Tannoudji, C., Dupont-Roc, J. & Grynberg, G. Atom-Photon Interactions: Basic Process and Appilcations (Wiley, 1998). https://doi.org/10.1002/9783527617197.

Mila, F. & Schmidt, K. P. Strong-Coupling Expansion and Effective Hamiltonians, 537–559 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-10589-0_20.

Fulde, P.Electron correlations in molecules and solids, vol. 100 (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012).

Mehrmann, V. & Voss, H. Nonlinear eigenvalue problems: a challenge for modern eigenvalue methods. GAMM-Mitteilungen 27, 121–152 (2004).

Dicke, R. H. Coherence in spontaneous radiation processes. Phys. Rev. 93, 99–110 (1954).

Hepp, K. & Lieb, E. H. On the superradiant phase transition for molecules in a quantized radiation field: the Dicke maser model. Ann. Phys. 76, 360–404 (1973).

Wang, Y. K. & Hioe, F. T. Phase Transition in the Dicke model of superradiance. Phys. Rev. A 7, 831–836 (1973).

Emary, C. & Brandes, T. Quantum chaos triggered by precursors of a quantum phase transition: The Dicke model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 044101 (2003).

Emary, C. & Brandes, T. Chaos and the quantum phase transition in the Dicke model. Phys. Rev. E 67, 066203 (2003).

Bužek, V., Orszag, M. & Roško, M. Instability and entanglement of the ground state of the Dicke model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 163601 (2005).

Rza̧żewski, K. & Wódkiewicz, K. Comment on “Instability and Entanglement of the Ground State of the Dicke Model”. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 089301 (2006).

Nataf, P. & Ciuti, C. No-go theorem for superradiant quantum phase transitions in cavity QED and counter-example in circuit QED. Nat. Commun. 1, 72 (2010).

Andolina, G. et al. A non-perturbative no-go theorem for photon condensation in approximate models. Eur. Phys. J. 137, 1–14 (2022).

Knight, J. M., Aharonov, Y. & Hsieh, G. T. C. Are super-radiant phase transitions possible? Phys. Rev. A 17, 1454–1462 (1978).

Andolina, G. M., Pellegrino, F. M. D., Giovannetti, V., MacDonald, A. H. & Polini, M. Cavity quantum electrodynamics of strongly correlated electron systems: A no-go theorem for photon condensation. Phys. Rev. B 100, 121109 (2019).

Andolina, G. M., Pellegrino, F. M. D., Giovannetti, V., MacDonald, A. H. & Polini, M. Theory of photon condensation in a spatially varying electromagnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 102, 125137 (2020).

Breuer, H.-P. & Petruccione, F. The Theory of Open Quantum Systems. Oxford Graduate Texts (Oxford University Press, 2002). https://books.google.it/books?id=Z1ZQAAAAMAAJ.

You, J. Q. & Nori, F. Atomic physics and quantum optics using superconducting circuits. Nature 474, 589–597 (2011).

Fleischhauer, M., Imamoglu, A. & Marangos, J. P. Electromagnetically induced transparency: Optics in coherent media. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 633–673 (2005).

Mencia, R. A., Lin, W.-J., Cho, H., Vavilov, M. G. & Manucharyan, V. E. Integer Fluxonium Qubit. PRX Quantum 5 https://doi.org/10.1103/PRXQuantum.5.040318 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge enlightening discussions with Filippo Ferrari. S.S. acknowledges the Army Research Office (ARO) (Grant No. W911NF-19-1-0065). V.S. acknowledges support by the Swiss National Science Foundation through Projects No. 200020_215172, 200021-227992, and 20QU-1_215928.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.S. conceived the research. D.L. and A.M. carried out the analytical and numerical calculations and wrote the manuscript. O.D.S. performed the preliminary simulations. V.S. and S.S. supervised the project. All authors participated in the discussion of the results and contributed to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

- This manuscript has been previously reviewed at another journal that is not operating a transparent peer review scheme. The manuscript was considered suitable for publication without further review at Communications Physics.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lamberto, D., Mercurio, A., Di Stefano, O. et al. Renormalization and low-energy effective models in cavity and circuit quantum electrodynamics. Commun Phys 8, 430 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02325-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02325-5