Abstract

The discrete element method (DEM) is a highly accurate and versatile approach for modeling large-scale particulate and fluid-mechanical systems critical to industrial processes. Additionally, DEM offers integration with grid-based computational fluid dynamics, making DEM a key ingredient for the modeling of many multi-physics systems. However, its computational demands, driven by the multiscale nature of these systems, limit simulation scale and duration. To address this, we introduce NeuralDEM, a fast and adaptable deep learning surrogate that captures long-term transport processes across various regimes using macroscopic observables, without relying on microscopic model parameters. NeuralDEM is a deep learning approach scalable to real-time industrial applications. Such scenarios have previously been challenging for deep learning models. NeuralDEM will open many doors to advanced engineering and much faster process cycles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, real-time numerical simulations1,2,3,4,5 have emerged as a modeling paradigm, enabling immediate analysis and decision-making based on live data and conditions. Unlike traditional simulations, which may take hours or even days to run, real-time simulations provide instantaneous feedback, allowing users to interact with and adjust parameters on the fly. Moreover, in engineering, fast simulations are driving the design of safer and more efficient structures and machines by accurately predicting their behavior under different conditions, thereby allowing extensive scans of vast parameter spaces and eliminating the need for expensive physical prototypes.

Especially for numerically expensive problems as found, e.g., in computational particle mechanics and/or fluid dynamics (CFD), selecting the appropriate numerical simulation tool requires weighing accuracy against speed. The discrete element method (DEM)6 provides one of the most accurate representations of a wide range of physical systems involving particulate matter and has become a widely accepted approach for tackling engineering problems connected to such systems. Typical target areas comprise mining and mineral processing7,8,9, steelmaking10,11,12, pharmaceutics13,14,15, additive manufacturing and powder bed fusion16,17,18.

However, the inherent multiscale nature of particulate systems makes DEM computationally costly in several well-known regards. (i) Large-scale granular flows consist of a huge number of particles, each interacting with the surrounding ones. For every grain, its equation of motion (EOM) needs to be solved in a coupled fashion. Current DEM studies dealing with process-relevant problems use many 100k19,20 or even a few million21 particles, while, e.g., an industrial shaft furnace or fluidized bed reactor contains several orders of magnitude more. (ii) The high material stiffness of solid particles severely limits the numerical timestep that can be used in the solution procedure of the EOMs. (iii) There is no straightforward relationship between the microscopic DEM parameters and macroscopically observed behavior. Instead, optimization techniques need to be used to find a set of DEM parameters that reproduces certain characterization measurements (e.g., angle of repose and shear cell measurements).

Issue (i) is usually mitigated by employing coarse-graining techniques that replace many small particles with a large parcel22,23. If the interaction parameters of these parcels are chosen appropriately – either using scaling rules or a calibration routine – the accuracy impairments compared to the fine-grained ground truth are often acceptable. However, the limitation of small timesteps is not sufficiently reduced by larger parcel sizes, and the need for parameter calibration persists, which makes DEM slow and sometimes too cumbersome for a quick application within engineering workflows.

For this reason, we have devised NeuralDEM, an end-to-end deep learning alternative for modeling industrial processes. NeuralDEM introduces multi-branch neural operators inspired by multi-modal diffusion transformers (MMDiT)24 and is scalable to real-time modeling of industrially-sized scenarios. In NeuralDEM, we introduce two key components. Firstly, we model the Lagrangian discretization given by DEM simulations directly from a compressed Eulerian perspective, and thus adopt a field-based point of view. NeuralDEM can generalize across boundary conditions such as inflow velocity and macroscopic quantities, such as internal friction angle, addressing issue (iii). The field-based modeling enables us to directly model macroscopic processes, e.g., mixing or transport, via additional auxiliary continuous fields. The second key component is multi-physics modeling via repeated interactions between physics phases. Multi-physics is prevalent when, e.g., modeling the interaction of fluid dynamics and particulate systems. Together, via the field-based and multi-physics modeling, NeuralDEM addresses common challenges in DEM simulations: enhancing computational feasibility for large particle systems, enabling longer timesteps, and direct conditioning on macroscopic properties without the need for fine-tuned microscopic DEM parameters. Finally, NeuralDEM, additionally learns to stably simulate the system using longer timesteps, addressing issue (ii).

In this work, we present NeuralDEM, a deep learning surrogate for discrete element method (DEM) simulations of granular flows. NeuralDEM combines a field-based representation with multi-branch neural operators, enabling stable and efficient modeling of large-scale particle systems and coupled multi-physics scenarios, as indicated in Fig. 1. We evaluate NeuralDEM on two representative cases: (i) slow and pseudo-steady hoppers with varying hopper angles, internal friction angles, and flow regimes, and (ii) fast and transient fluidized bed reactors with varying inflow velocities. Across both cases, NeuralDEM accurately reproduces key macroscopic quantities such as drainage times, residence times, and mixing indices, while reducing simulation costs by several orders of magnitude. These results suggest that NeuralDEM can extend the applicability of data-driven surrogates to industrially relevant granular flows, providing a foundation for more efficient engineering design and process optimization.

NeuralDEM is an end-to-end approach to replace discrete element method (DEM) routines and coupled multi-physics simulations with deep learning surrogates. a Hopper simulations. NeuralDEM treats inputs and outputs as continuous fields, while modeling macroscopic behavior directly as additional auxiliary fields. b Fluidized bed reactors. NeuralDEM is built to model complex multi-physics simulations, i.e., scenarios that necessitate the interaction of DEM and computational fluid dynamics (CFD). For fluidized bed reactors, air enters the domain from the bottom plane (CFD problem) and pushes the particles up (DEM problem). DEM considers three types of forces that act on particles: particle-particle contacts F(pc), external forces F(ext), and the interaction with a surrounding fluid phase F(pf). Both parts and the interaction thereof are modeled via the multi-branch neural operator approach of NeuralDEM.

Results

We tested the NeuralDEM framework on two industrially relevant use cases with lab-scale dimensions, hoppers and gas-solid fluidized bed reactors, as visualized in Fig. 2. Due to the vast differences of these settings, we trained separate models for the two use cases. We evaluated NeuralDEM on different metrics: (i) Effectiveness of field-based modeling w.r.t. macroscopic quantities. We extracted and compared emerging macroscopic physics phenomena such as drainage times and mixing indices. (ii) Scalability toward industry-relevant simulation sizes. We trained on simulations with up to half a million particles and anticipate good scaling behavior to much higher numbers. (iii) Physically accurate time extrapolation. We showed that our models faithfully describe dynamics for long time horizons – in a fraction of the time that a classical solver would have taken. (iv) Generalization to unseen regions in the design parameter space, such as hopper angles, particle properties, or fluid inlet velocity.

Schematic of the experimental setups for (a) an initially full hopper silo that drains over time through an outlet at the bottom center, and b a fluidized bed reactor where air is pushed in from the bottom, moving particles around. c The associated dimensions and simulation parameters for both experimental setups.

Hopper

Hoppers are used for short- as well as long-term storage of particulate materials, showcasing slow and pseudo-steady macroscopic behavior. Our experiments contained 250k particles, which gradually exited the domain at the bottom outlet with wall angles between 0° and 60° and different grain friction values. In the present study, we did not consider conditions leading to hanging. One can only speculate if NeuralDEM is capable to learn jamming from corresponding training data, or if one would have to integrate a stochastic model that triggers such events based on a separately learned probability function.

A timestep of ΔtDEM = 10 μs was required for numerical stability of the simulations carried out with LIGGGHTS25 using a standard set of contact models, a non-linear Hertz model for normal force, a history-based tangential force model, and a spring-dashpot model for rolling friction. NeuralDEM, on the other hand, permitted ΔtML = 0.1 s = 10,000 ΔtDEM. Altogether, we created a dataset of 1000 simulations with a random train/validation/test split of 800/100/100.

To train NeuralDEM on hopper simulations, we introduced two auxiliary fields for occupancy and transport. The occupancy field described whether or not a position was occupied by a particle. The transport field predicted the starting position of each particle, modeling the integrated movement over all previous timesteps. Our model contained 50M parameters and was trained for 10 epochs using the LION26 optimizer with batch size 256 and a linear warmup to a learning rate of 1e-4 over the first epoch, followed by a cosine decay schedule. The training took roughly 10 H100 GPU-hours or just over 1 h on a node with 8 H100 GPUs.

Flow regime and visualization via occupancy and transport field

To evaluate the macroscopic modeling of the flow regime inside the hopper, we queried the occupancy field to find occupied positions and then queried the transport field at these positions. We binned the z coordinate of the transport prediction into eight bins, which resulted in “stripes” of particles at the initial timestep. These stripes then evolved in time as particles flowed out. By evaluating their shape and volume at every timestep, we got detailed information on the different flow regimes in the hopper that emerged in dependence on the geometry angles and grain friction coefficients.

Figure 3a shows a case of mass flow, where material moved to the outlet quite uniformly, resulting in a steady flow and a first in - first out operation. NeuralDEM modeled this behavior accurately with layer after layer, leaving the hopper as quantified in Fig. 3b. Contrary, in the funnel flow regime, the material primarily moved down a funnel above the outlet. This resulted in a layer inversion as evidenced by Fig. 3c. Particles from higher layers overtook those from the lower layers through the funnel, and the layers higher up in the hopper emptied first. NeuralDEM reproduced the emerging macroscopic phenomenon with high accuracy. An illustration of this regime is provided in the top row of Fig. 1.

NeuralDEM-generated trajectories vs DEM simulations for the hopper case. a 3D visualizations of the mass flow regime, where different colors indicate different initial particle layers. The fractions of colored material over time are shown in (b) and (c). In mass flow (b), material gets transported uniformly toward the outlet. In funnel flow (c), grains primarily move down a funnel above the outlet, resulting in layer inversion (cf. the top row of Fig. 1), i.e., particles from higher layers overtake those from the lower layers through the funnel. d, e Predictions for residual volume and drainage time for a large variety of parameter combinations showed a high accuracy compared to the DEM ground truth. f, g Drainage time prediction for different dataset splits. f By default, we randomly split data into train/test sets. g Generalization to unseen parameter combinations where all simulations within a 20∘ range of hopper and shear cell friction angle were excluded from training. Empty circles indicate training simulations. The average error is shown on top of (f) and (g). All these emerging macroscopic phenomena were perfectly modeled by NeuralDEM. h, i Time-averaged displacements in the x- and z-directions of five test simulations with different flow regimes, interpolated to evenly spaced positions along the y-axis at the neck position (top of the tapered region). Detailed data are presented in tabular form in Supplementary Data 1.

Notably, NeuralDEM exclusively models fields, which allowed us to evaluate transport and occupancy at arbitrary positions with arbitrary resolution. For example, for the evaluations of this section, we used a tetrahedral grid with 80k cells. Our model made predictions thereof seamlessly despite having seen only particle positions during training.

Drainage time and residual volume

We considered the hopper to be drained by specifying a threshold of particles located above the outlet (“falling down”) for both classical DEM- and NeuralDEM-generated trajectories. This definition was necessary as material residues got stuck on the outlet slope if it was very frictional or if the slope was too flat. To evaluate the drainage time of the NeuralDEM model, we queried the occupancy field at the particle positions of the initial packing above the outlet until the number of occupied positions was less than a specified threshold. After the hopper was drained, we queried the occupancy field again at all initial particle positions to get the number of residual particles. We then divided their number by that of the initial particles to obtain the residual volume. A comparison of drainage times and residual volumes obtained when running numerical DEM simulations with those from NeuralDEM is provided by Fig. 3e. For all investigated combinations of particle properties and geometry angles, we found a very good agreement with an average drainage time error of 0.19 s, with a majority of drainage times being larger than 20 s. Also, residual volumes had a high agreement with an average error of 0.41%. These results were insensitive to the specific value of the threshold within reasonable bounds.

The average prediction error of the drainage time increased to about 0.4 s for a NeuralDEM model that had been trained with the same particle size and density, but a single macroscopic material property, such as the shear cell friction angle, as input instead of microscopic DEM interaction parameters. Since the calibration of DEM parameters from characterization experiments might not even yield a unique solution, we regard this prediction accuracy as surprisingly good. To decrease the error further, additional macroscopic properties could be integrated. However, the same care as for DEM parameter calibration routines would have to be taken for a proper choice of characterization experiments27.

To further analyze generalization performance, we considered a different data split that assigned all simulations where both the hopper angle and the internal friction angle were within the “center” region of 20° to the test set. Figure 3g visualizes the prediction of NeuralDEM on this split, where Fig. 3f shows results for the random data split for reference. Note that we employed the shear cell friction angle only for visualization purposes; the models used rolling and sliding friction scalars, which are more informative.

We compare NeuralDEM’s implicit drainage time predictions (via occupancy field queries) with explicit models such as a k-nearest neighbor (k-NN) regressor and a multilayer perceptron (MLP), which map scalar parameters (hopper angle, sliding friction, rolling friction) to ground truth drainage times, with hyperparameters tuned via grid search. k-NN yielded 0.73 s/1.6 s error (random/generalization splits), while NeuralDEM achieved 0.19 s/0.23 s, showing it learned richer structures than a simple lookup. The MLP reached 0.1 s/0.21 s, slightly outperforming NeuralDEM. Notably, the MLP performance suffered a larger performance drop from random to generalization split. In contrast, NeuralDEM’s minor performance drop suggests that learning full simulation dynamics generalizes better than scalar mapping.

Local time-averaged displacement

To investigate the local agreement of NeuralDEM with DEM, we evaluated the time-averaged displacement per timestep at the top of the tapered region. We selected evenly spaced points along the y-axis and interpolated particle displacements to these fixed locations for every timestep and then averaged these values over time. Figure 3h and i shows strong agreement of NeuralDEM with classical DEM, also in local evaluations.

Fluidized bed

We considered the highly unsteady dynamics of fluidized beds, where particles and air interact in a coupled CFD-DEM simulation. The reactor was filled with 500k particles, and the air that (uniformly) entered the reactor from the bottom was modeled on a grid of 160k hexahedral cells. In total, 456 CFD-DEM trajectories with inlet velocities sampled uniformly from 0.337 m s−1 to 0.842 m s−1 were used, which were randomly split into 360 train simulations and 96 validation simulations. Other parameters, such as particle size or gas density, were kept fixed but could have been included at the cost of creating more training data. The physical duration of one simulation, using a standard set of contact models (a non-linear Hertz model for normal force, a history-based tangential force model, and the Beetstra28 drag force model), amounted to 5 s, comprising 2M DEM timesteps and 20k CFD timesteps. The NeuralDEM model was trained with ΔtML = 4000ΔtDEM and started at 2 s of the original simulation. Additionally, we created 4 simulations of 30 s to evaluate the time extrapolation of our model.

Compared to the hopper simulations, the fluidized bed reactor required longer training with larger models to accurately model simulations due to the chaotic nature of the system. We trained an 850M parameter model for 150 epochs using the LION26 optimizer with batch size 128 and a linear warmup to a learning rate of 4e-5 over the first 15 epochs, followed by a cosine decay schedule. The training took roughly 320 H100-hours and was trained in 10 h on 32 H100 GPUs.

Short- and long-term dynamics

NeuralDEM effectively modeled the chaotic bubble dynamics and accurately reflected the transitions in flow patterns and complex fluidization behavior. A visual comparison of the iso-surface of solid fraction and the magnitude of fluid velocity, shown in Fig. 4a, reveals that the time series closely resembles the corresponding ground truth snapshots. This is especially evident in the bubble structure displayed by the iso-surface of the solid fraction field, where a complex bubble structure forms inside the particle bed at the given inlet velocity.

Visualization of fluidized bed dynamics: a Three snapshots taken at 0.06 s, 0.09 s, and 0.12 s for an inlet velocity of 0.7 m s−1 demonstrate the short-term dynamics. The iso-surfaces of solid fraction at 0.35 uncover the emerging bubble structure of fluidized bed reactors, and the central slices along the y-axis show the magnitude of fluid velocity. b The long-term dynamics, obtained by rolling out the model approximately 10 times its training horizon, are shown using time-averaged fields for particle solid fraction and magnitude of fluid velocity. c Granular mixing behavior is quantified with the temporal evolution of the Lacey mixing index for an unseen inlet velocity of 0.55 m s−1 (cf. Fig. 1 for a visual reference). d, e The average bed height and the approximated kinetic energy of the particles are displayed for the investigated range of inlet velocities.

Additionally, we evaluated time extrapolation capabilities, where we rolled out our model for 28 s (training was performed with data from 3-s-long simulations). Due to the chaotic dynamics in fluidized beds, we used time-averaged statistics for the long-term evaluation. A precise step-by-step comparison would not have been feasible due to diverging trajectories that naturally arise during long rollouts. We found very good agreement of both the temporal averages and standard deviations, as evidenced by Fig. 4b. For mass conservation, we observed hardly any deviation or drift between NeuralDEM and CFD-DEM over the observation time range of 28 s. The mass remained within a 1.5% error margin, demonstrating strong consistency throughout the simulation.

The model demonstrated strong performance on key metrics, achieving a mean error of less than 1% for the average bed height across all test cases, as shown in Fig. 4d. For the bubble frequency, which was only well defined in the low inlet velocity regime, the error remained below 1.5%. In addition, bed dynamics were analyzed using an approximate measure of kinetic particle energy, derived from particle displacements over a machine learning timestep. This estimate did not fully reflect the true kinetic energy, as it is based on average rather than instantaneous particle velocities. As illustrated in Fig. 4e, a larger discrepancy was observed for this metric compared to others. This was primarily due to the absence of velocity fluctuations in NeuralDEM, which captured only the mean particle flow instead of the full spectrum of particle dynamics. Nonetheless, the average error for the kinetic energy approximation remained below 9%.

Mixing

We carried out granular mixing simulations by labeling particles initially in the left half of the reactor as A and those in the right half as B. Since NeuralDEM relies on a field representation, we introduced the concentration fields of particles A and B, respectively. For the comparison with the ground truth in terms of CFD-DEM, we mapped the DEM positions on a mesh employing a Gaussian kernel. These fields were then compared in terms of the Lacey mixing index29. As mixing progressed, it went toward 1. Figure 4c shows that NeuralDEM matched for a medium inlet velocity of 0.55 m s−1 the characteristics of the ground truth trajectory over long time horizons. Furthermore, it accurately predicted the mixing rate for both slow-mixing systems and fast-mixing ones by simply conditioning on the appropriate inlet velocity.

Discussion

The presented work has introduced NeuralDEM, a multi-branch neural operator framework that can learn the complex behavior of particulate systems over a wide range of dynamic regimes: from dense, pseudo-steady motion in hoppers to dilute, highly unsteady flow in fluidized bed reactors. NeuralDEM treats the Lagrangian discretization of DEM as an underlying continuous field while simultaneously modeling macroscopic behavior directly as additional auxiliary fields. Long-term rollouts of our data-driven model showed a high degree of stability and led to accurate predictions regarding various target quantities such as residence times or mixing indices, even for unseen conditions like different wall geometries, material properties, or boundary values.

Our approach addresses the multiscale problem of particulate flows in at least two ways: (i) much larger timesteps than those used in classical simulations and (ii) the incorporation of macroscopic characteristics like the angle of repose or shear cell measurements without the specification of microscopic DEM parameters.

Property (i) leads to evaluation times that are several orders of magnitude faster than the underlying (CFD-)DEM simulations and demonstrate the real-time capability of NeuralDEM. NeuralDEM’s field-based representation is computationally much more efficient than the coupled solution of a huge number of real-space EOMs and lends itself to massive parallelization.

Simulating a granular flow of 250k particles through a hopper over 40 s required 3 h on 16 cores of high-performance CPUs when using traditional DEM. In contrast, on a single state-of-the-art GPU, the fastest NeuralDEM inference model faithfully reproduced the physics rollout in just 1.4 s.

Processing all 250k output points on a single GPU took 8 s, and running NeuralDEM on the same 16 CPUs resulted in a trajectory rollout of 41 s.

Compared to the hopper simulations, the fluidized bed reactor was larger and more complex, requiring roughly 20 times larger neural network architectures. Numerically, when using traditional CFD and DEM methods, the simulation of a fluidized bed reactor of 500k particles, with a trajectory spanning 3 s, amounted to 12k CFD and 1.2M DEM timesteps. This required 6 h on 64 cores of high-performance CPUs. In contrast, on a single state-of-the-art GPU, the fastest NeuralDEM inference model faithfully reproduced the same physical behavior in just 11 s. With further speedups via, e.g., model parallelization30,31, or model quantization32,33, real-time inference is within reach.

Regarding property (ii), NeuralDEM does not require the specification of (artificial) microscopic DEM parameters. Instead, it can directly operate on macroscopic properties like the friction angle and flow function from shear cell measurements if sensible ranges of these properties are reflected by the training data. This allows for a simple integration into engineering workflows without inference of DEM parameters via, e.g., a calibration procedure34 before the actual simulation of the material can be run. To condition NeuralDEM on macroscopic parameters, we evaluated the internal friction angle and flow function coefficient in a separate shear cell simulation and trained our model with these properties instead of the microscopic sliding and rolling friction. A certain performance drop was expected as only the microscopic material properties 1:1 reflect the underlying DEM simulation. However, its magnitude was within an acceptable range. For example, the average error on the hopper draining time increased from 0.19 s for given microscopic DEM parameters to 0.4 s for the usage of macroscopic characteristics instead.

While NeuralDEM demonstrates the merits and massive potential of deep learning surrogates, we have applied our methodology only to test cases that are smaller and simpler than real industrial processes. For this reason, future work will address the issues of larger scales and more complex physics. With regard to the spatial scope, it is not clear yet if it is preferable to use data from detailed, fine-grained simulations in small domains and devise strategies for NeuralDEM to upscale this information, or if large-scale data from more approximate, coarse-grained simulations without subsequent upscaling steps lead to more reliable results. Concerning real multi-physics predictions, it is desirable to include heat transport and transfer as well as chemical reactions into NeuralDEM. A larger number of branches needs to interact with each other in the neural operator – dynamics, heat transfer, and chemistry can be tightly coupled – to give a detailed description of how grains of different temperatures and compositions mix and interact. Besides this conceptual challenge, such systems often come with additional time scales because certain chemical reactions might be very slow compared to, e.g., the rapid particle and bubble motion in a fluidized bed. In these cases, data generation with conventional numerical methods could become unfeasible, and it might be necessary to include an intermediate, data-assisted step35 to first obtain long-term training data from short, high-fidelity time series.

Finally, it would be useful to devise a model that can generalize not only over material properties, simple geometry variations, or values of boundary conditions, but also over completely different flow regimes, domain shapes, etc. The demands for training and data preparation would be significant, but huge amounts of such simulation data exist, distributed over research departments around the world.

Methods

Discrete element method

In a system of solid particles with masses mi, radii ri, positions ri, and velocities vi, each of them has to obey Newton’s second law

Particle i experiences forces of external origin, most importantly gravity \({{{{\bf{F}}}}}_{i}^{({{{\rm{ext}}}})}\approx {m}_{i}{{{\bf{g}}}}\), contact forces with the nearby grains and walls \({{{{\bf{F}}}}}_{i}^{({{{\rm{pc}}}})}={\sum }_{j\ne i}{{{{\bf{F}}}}}_{i,j}\), and the influence of a surrounding fluid phase \({{{{\bf{F}}}}}_{i}^{({{{\rm{pf}}}})}\) if present and relevant. The contact force between solid particles i and j is commonly approximated with spring-dashpot models. While simple geometric shapes such as perfect spheres allow computing values for the spring stiffness and dashpot damping from measurable properties like Young’s modulus and coefficients of restitution36, actual, imperfect grains necessitate calibration toward characterization experiments34.

The magnitude of the numerical timestep to solve Equation (1) is limited by the requirement to properly resolve contacts between grains. More specifically, the timestep needs to be significantly smaller than the duration of contact of colliding particles (“Hertz time”) and the time it takes density waves generated upon impact to travel over the grain surface (“Rayleigh time”). For stiff materials, this often amounts to steps in the range of microseconds.

Coupled particle-fluid simulations

Particles will also experience a force from a surrounding fluid phase. While it may be neglected if no significant relative velocities occur, it can be a crucial factor for particle dynamics otherwise. The dominant contributions are usually caused by gradients of the pressure and by the drag force, i.e., the resistance against relative velocity between fluid and grain, so that

The drag coefficient β depends on the particle size and the local flow conditions. A multitude of empirical correlations can be found in the literature to take into account the impact of Reynolds number, particle volume fraction αp, size distribution, etc.37. In the present work, other types of forces, such as lift, were neglected for the sake of simplicity. However, they could be easily included if necessary, e.g., for non-spherical grain shapes. While the machine learning model would have to be extended with additional properties like particle orientation or angular velocity, we do not anticipate any fundamental issues connected to such generalizations.

The fluid velocity itself is governed by the filtered Navier–Stokes equations38

which differ from their single-phase counterpart in two regards. The presence of particles reduces the locally available volume to a fraction αf = 1 − αp, and the density of force Equation (2) exerted by the fluid on the particles is felt by the fluid in the opposite direction because of Newton’s third law. The coupled solution of the CFD Equations (3) and (4) and the DEM Equation (1) gives rise to CFD-DEM simulations.

For a proper definition of the field quantities αp and f(pf), Lagrangian particle information needs to be mapped onto Eulerian fields. To this end, a filter function gl(r), e.g., a Gaussian with width l, is employed in terms of

An analogous definition to Equation (6) can be invoked to define the spatial field distribution of any particle property.

Neural operators

Neural operators are well-suited to describe the evolution and interaction of physical quantities over space and time, i.e., continuously changing fields. Neural operators39,40,41,42 are formulated with the aim of learning a mapping between function spaces, usually defined as Banach spaces \({{{\mathcal{U}}}}\), \({{{\mathcal{V}}}}\) of functions defined on compact input and output domains \({{{\mathcal{X}}}}\) and \({{{\mathcal{Y}}}}\), respectively. A neural operator \(\hat{{{{\mathcal{G}}}}}:{{{\mathcal{U}}}}\to {{{\mathcal{V}}}}\) approximates the ground truth operator \({{{\mathcal{G}}}}:{{{\mathcal{U}}}}\to {{{\mathcal{V}}}}\).

When training a neural operator \(\hat{{{{\mathcal{G}}}}}\), a widely adopted approach is to construct a dataset of N discrete data pairs \(({{{{\boldsymbol{u}}}}}_{i,j},{{{{\boldsymbol{v}}}}}_{i,{j}^{{\prime} }})\), i = 1, …, N, which correspond to ui and vi evaluated at spatial locations j = 1, …, K and \({j}^{{\prime} }=1,\ldots ,{K}^{{\prime} }\), respectively. Note that K and \({K}^{{\prime} }\) can, but need not be equal, and can vary for different i, which we omit for notational simplicity. In neural operator learning, the goal is to learn an approximation of the ground truth operator \({{{\mathcal{G}}}}\), that maps an input function ui to an output function vi via a neural operator \(\hat{{{{\mathcal{G}}}}}\). The functions are given via K and \({K}^{{\prime} }\) discretized input and output points, respectively. On this dataset, \(\hat{{{{\mathcal{G}}}}}\) is trained to map ui,j to \({{{{\boldsymbol{v}}}}}_{i,{j}^{{\prime} }}\) via supervised learning, where \(\hat{{{{\mathcal{G}}}}}\) is composed of three maps43,44: \(\hat{{{{\mathcal{G}}}}}:= {{{\mathcal{D}}}}\circ {{{\mathcal{A}}}}\circ \,{{{\mathcal{E}}}}\), comprising the encoder \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}\), the approximator \({{{\mathcal{A}}}}\), and the decoder \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}\). First, the encoder \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}\) transforms the discrete function samples ui,j to a latent representation of the input function. Then, the approximator \({{{\mathcal{A}}}}\) maps the latent representation to a representation of the output function. Lastly, the decoder evaluates the output function at spatial locations \({j}^{{\prime} }\). The neural network \(\hat{{{{\mathcal{G}}}}}\) is then trained via gradient descent, using the gradient of, e.g., a mean squared error loss in the discretized space \({{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}_{i}=\frac{1}{{K}^{{\prime} }}{\sum }_{{j}^{{\prime} }}\parallel {\hat{{{{\boldsymbol{v}}}}}}_{i,{j}^{{\prime} }}-{{{{\boldsymbol{v}}}}}_{i,{j}^{{\prime} }}{\parallel }_{2}^{2}\), where ∥2 is the Euclidean norm.

NeuralDEM

NeuralDEM presents an end-to-end solution for replacing computationally intensive numerical DEM routines and coupled CFD-DEM simulations with fast and flexible deep learning surrogates. NeuralDEM introduces two modeling paradigms:

-

Physics representation: We model the Lagrangian discretization of DEM as an underlying continuous field, while simultaneously modeling macroscopic behavior directly as additional auxiliary fields. NeuralDEM encodes different physics inputs that are representative of DEM dynamics and/or multi-physics scenarios. Examples are particle displacement, particle mixing, solid fraction, or particle transport.

-

Multi-branch neural operators: We introduce multi-branch neural operators scalable to real-time modeling of industrial-size scenarios. Multi-branch neural operators build on the flexible and scalable “Universal Physics Transformer”44 framework by enhancing encoder, decoder, and approximator components using multi-branch transformers to allow for modeling of multi-physics systems. The system quantities fundamental to predicting the evolution of the state in time are modeled in the main branches, where they are tightly coupled. Additionally, auxiliary off-branches can be added to directly model macroscopic quantities by retrieving information from the main-branch state and further refining the prediction using relevant inputs.

Physics representation

As is common when training deep learning surrogates, we train on orders of magnitude coarser time scales than what a classical solver requires to be stable and accurate. For the numerical experiments in this paper, the timescale relation is at least 1000ΔtDEM = ΔtML. Additionally, for learning the dynamics of particle movement, we use the particle displacement, which is defined as the difference between the position \({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{i}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{3}\) of particle i at timestep tML and the position of the same particle at timestep tML + ΔtML. Finally, we use the term transport to denote the particle movement integrated over multiple timesteps ΔtML.

NeuralDEM models the Lagrangian discretization of DEM as a continuous field in a compressed latent space, leveraging the insight that the effective degrees of freedom of physical systems are often much smaller than their input dimensionality45. Therefore, we assume that there exists some underlying field that describes the particle displacements in a DEM simulation and learn this underlying field over the whole domain instead of a displacement per particle. However, particle displacements can fluctuate depending on their exact position within the bulk of the material. Such fine-grained details are lost when going to a field-based representation, which smoothes out these variations. This makes field-based models unable to move particles accurately around in space, which would be required to get macroscopic insights into the simulation dynamics.

To circumvent this issue, we introduce additional auxiliary fields that model the macroscopic insights directly instead of calculating them in post-processing from the particle locations. For example, by modeling the accumulated particle movement over a long period of time via a “transport” field, we can learn macroscopic properties directly instead of integrating short-term movements, which would require precise prediction of the fluctuations thereof. This is visualized in Fig. 5. Similarly, NeuralDEM could learn the local Sauter diameter field \({d}_{{{{\rm{S}}}}}({{{\bf{r}}}})\equiv {\sum }_{i}{g}_{l}(| {{{\bf{r}}}}-{{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{i}| ){d}_{i}^{3}/{\sum }_{i}{g}_{l}(| {{{\bf{r}}}}-{{{{\bf{r}}}}}_{i}| ){d}_{i}^{2}\) and its variance to approximate the dynamics of a polydisperse system. For more complex cases like multipeak size distributions, one could train a model to predict the probability of finding a grain with a certain diameter at a given location, which would provide a more comprehensive view but come with higher data demands.

Using the presented continuous physics representation, we model the Lagrangian discretization of DEM as an assumed underlying field. The approximator maps the encoded representation to one that can be decoded at any specified spatial location \(j{\prime}\). The multi-branch neural operator is a family of deep learning architectures that processes multi-physics quantities and can distinguish between primary quantities, used to model the core physics in the main branches, and secondary quantities, which are used to predict additional desired quantities in the off-branches, both modeled as fields. The quantities come, e.g., from DEM simulations with coupled particles and fluid, which the architecture handles using specialized encoders and decoders. All modules processing the primary quantities influence each other. In contrast, those that process secondary quantities are independent and use the tokens from the primary branch as additional information but cannot affect them.

Even over such a large timestep, the evolution of a flow and its properties at each point is mainly determined by the field values in a nearby, bounded subdomain which grows with the step size, and is hardly influenced by very distant points46. This behavior can be resembled by the attention mechanism of transformer networks47.

Multi-branch neural operators

Emerging bulk behavior of classical solvers as motivation

Classical solvers can create full simulations via precisely updating microscopic properties such as the particle positions at extremely high time resolution, with optional coupling to, e.g., a fluid phase, which is updated with similar precision and timescale. Similarly, NeuralDEM aims to extract the physical dynamics and simulation state updates from the microscopic properties also used in classical solvers, which we call “main-phase(s)” where each main-phase is processed by one main-branch transformer in our model. Using an example of a particle-fluid coupled simulation, one main branch predicts particle displacements, while a second main branch predicts fluid velocities and pressures. All main branches are tightly coupled via frequent information exchange during the model forward pass.

Microscopic inaccuracies of neural operators

While the model is trained using microscopic properties, neural operators are not able to predict microscopic properties, such as the particle displacements, accurately enough because neural operators are not as precise as classical solvers and operate on a much coarser time resolution. It is therefore not feasible to exclusively rely on an accurate prediction of these microscopic properties in the main branches. Creating simulations by moving initial particle positions according to the predicted displacements would quickly result in unphysical states (e.g., overlapping particles) and become inaccurate.

Macroscopic modeling via auxiliary fields

An important observation regarding the systems we model is that the insights that a classical solver can provide into the physical dynamics are rarely on a microscopic level and more often on a macroscopic level, where the macroscopic properties are extracted from the microscopic results of the classical solver. Motivated by this intuition, we introduce additional off-branches, which are trained to model macroscopic processes such as particle mixing or particle transport directly during training. Similar to classical solvers, where the macroscopic process does not influence the microscopic updates, off-branches do not influence any of the main branches. Instead, each off-branch creates its predictions by repeatedly processing its own data, as well as retrieving information from the microscopic state of the main branches (without influencing them).

Multi-branch transformers

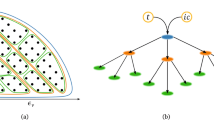

The central neural network component of NeuralDEM is a multi-branch transformer. Multi-branch transformers, as the name suggests, consist of multiple branches: main branch(es) and off-branch(es). Each branch is a stack of transformer47 blocks where weights are not shared between branches. Each branch operates on a set of so-called tokens, which are obtained by embedding the input into a compressed latent representation. Main branch(es) concatenates all tokens before each attention operation along the set dimension, allowing interactions between them, followed by splitting tokens again into the different branches, akin to multi-modal diffusion transformer (MMDiT) blocks24. Additionally, multi-branch transformers can include arbitrarily many off-branches, where the self-attention is replaced by a cross-attention which uses only its own off-branch tokens as queries and concatenates its own off-branch tokens with the main-branch tokens to use as keys and values. This roughly corresponds to simultaneous self-attention between the off-branch tokens and cross-attention between off-branch and main-branch tokens. No gradient flows through the cross-attention back to the main-branch tokens. Off-branches are implemented via a modified diffusion transformer block48. A schematic sketch is shown in Fig. 6.

Schematic of a multi-branch transformer architecture. DiT48 modulation is applied to each attention and MLP block but is omitted for visual clarity.

In our numerical experiments, we consider temporally evolving systems of multiple fields. Each input at time t \({{{{\boldsymbol{u}}}}}_{i}^{t}\) consists of h = 1, …, M fields, where the hth field at timestep t is denoted as \({{{{\boldsymbol{u}}}}}_{i}^{h,t}\). Each field is modeled by one branch of the multi-branch transformer. We create datasets of function pairs that are evaluated at K and \({K}^{{\prime} }\) input and output positions \(({{{{\boldsymbol{u}}}}}_{i,j}^{h,t}\,{{{{\boldsymbol{v}}}}}_{i,{j}^{{\prime} }}^{h,t+\Delta t})\) and train all M branches in parallel to map \({{{{\boldsymbol{u}}}}}_{i,j}^{h,t}\) to the target \({{{{\boldsymbol{v}}}}}_{i,{j}^{{\prime} }}^{h,t+\Delta t}\). Each branch of the multi-branch transformer consists of M encoders \({{{{\mathcal{E}}}}}^{h}\), M approximators \({{{{\mathcal{A}}}}}^{h}\), and M decoders \({{{{\mathcal{D}}}}}^{h}\).

Scalar parameter conditioning

Physical simulations often require various scalar parameters such as material properties (e.g., friction or particle size) or geometry variations (e.g., slope angles or outlet width) to define the simulation properties. It is vital to provide these scalars also to the machine learning model to produce accurate results. A common way to do this is by feature modulation49 which scales and shifts intermediate feature activations based on a vector representation of the scaler parameters. As NeuralDEM is a transformer architecture, we use DiT-style modulation48, which scales, shifts, and gates the activations of each attention and MLP block based on a learned vector representation of the scalar parameters. This form of conditioning allows NeuralDEM to generalize across geometries and across non-trivial particle-particle interactions by conditioning on respective variables.

An important property of this conditioning mechanism is that it allows us to condition on parameters that describe only the macroscopic material behavior. For example, our model can be conditioned on the measured parameters, like the internal friction angle or the flow function coefficient from a shear cell device, instead of requiring the microscopic friction parameters necessary for simulating with a classical DEM solver (e.g., particle sliding friction coefficient). In practice, this allows us to simulate any material by simply using a shear cell to determine its friction angle. In contrast, for classical solvers, one would need to estimate the microscopic friction parameters of the material using a calibration procedure34 in order to simulate it, which is tedious, error-prone, and often inaccurate.

Flexible model architecture for variable simulation use cases

As physical simulations exhibit a broad range of dynamics, and relevant macroscopic insights can vary drastically depending on the use case, our multi-branch transformer architecture should be seen as a flexible framework that enables various use cases instead of a “set in stone” architecture. Components can become redundant in certain settings, or special use cases could require additional components. For example, in simulations with laminar or pseudo-steady dynamics, the whole simulation is fully specified by the initial state, making encoding subsequent states and interaction between branches redundant. However, in very unsteady systems, all components of the multi-branch transformer architecture are very much necessary to produce accurate time evolution, as slightly different initial states can lead to vastly different instantiations of dynamics, which requires a physically accurate state at each timestep and interactions between the states of different branches.

Additionally, the initial encoding of physics phases benefits from specialized designs, depending on the input data. For irregular grid data (e.g., particles), we use the supernode pooling from UPT44, which aggregates information around particles via message passing to so-called supernodes, which are randomly selected particles. Fluid phases are typically represented via regular grid data, which is computationally more efficient and allows efficient coupling to, e.g., particle simulations. For regular grid data, we use the vision transformer patch embedding50, which splits the input into non-overlapping patches and embeds them using a shared linear projection.

Finally, decoding is performed using the same architecture for both particle and grid data, using a perceiver-based neural field decoder51, which is queried at locations \({{{{\boldsymbol{y}}}}}_{i,{j}^{{\prime} } = 1,\ldots ,{K}^{{\prime} }}\) in parallel. This type of decoding first embeds query locations to be used as queries for the perceiver cross-attention and uses the latent tokens as keys and values. This results in a point-wise evaluation of the latent space based on the query position, which is what enables effective parallelization.

We use a standard pre-norm vision transformer architecture50,52 where each branch of the multi-branch transformer corresponds to a single vision transformer. The total number of blocks is evenly distributed across the encoder, approximator, and decoder.

Data availability

As the storage requirements for the full datasets considered in this study are quite large (3.2 TB), it is available upon request from data@emmi.ai. Additionally, a single trajectory of the hopper and the fluidized bed simulations is published together with the model weights and inference code as outlined in the code availability statement.

Code availability

We published code to reproduce the results of this study using a single trajectory of the full dataset at https://github.com/Emmi-AI/NeuralDEM. This includes code for loading the published data, visualizing the data, instantiating a NeuralDEM model with a provided pre-trained checkpoint, generating a trajectory using this model, visualizing the results, and calculating metrics. The released code also includes a project page (https://emmi-ai.github.io/NeuralDEM/) with video visualizations of the data and the model predictions.

References

Chen, Y. et al. Digital twins in pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical manufacturing: a literature review. Processes 8, 1088 (2020).

Ali, Z. et al. From modeling and simulation to digital twin: evolution or revolution? SIMULATION 100, 751–769 (2024).

Guillaud, X. et al. Applications of real-time simulation technologies in power and energy systems. IEEE Power Energy Technol. Syst. J. 2, 103–115 (2015).

Yan, W., Wang, J., Lu, S., Zhou, M. & Peng, X. A review of real-time fault diagnosis methods for industrial smart manufacturing. Processes 11, 369 (2023).

Javaid, M., Haleem, A. & Suman, R. Digital twin applications toward industry 4.0: A review. Cogn. Robot. 3, 71–92 (2023).

Cundall, P. A. & Strack, O. D. L. A discrete numerical model for granular assemblies. Géotechnique 29, 47–65 (1979).

André, F. P. & Tavares, L. M. Simulating a laboratory-scale cone crusher in DEM using polyhedral particles. Powder Technol. 372, 362–371 (2020).

Mittal, A., Mangadoddy, N. & Banerjee, R. Development of three-dimensional GPU DEM code–benchmarking, validation, and application in mineral processing. Comput. Part. Mech. 10, 1533–1556 (2023).

Zhang, C., Chen, Y., Wang, Y. & Bai, Q. Discrete element method simulation of granular materials considering particle breakage in geotechnical and mining engineering: a short review. Green. Smart Min. Eng. 1, 190–207 (2024).

Aminnia, N. et al. Three-dimensional CFD-DEM simulation of raceway transport phenomena in a blast furnace. Fuel 334, 126574 (2023).

Amani, H., Alamdari, E. K., Moraveji, M. K. & Peters, B. Experimental and numerical investigation of iron ore pellet firing using coupled CFD-DEM method. Particuology 93, 75–86 (2024).

Lichtenegger, T. & Pirker, S. Fast long-term simulations of hot, reacting, moving particle beds with a melting zone. Chem. Eng. Sci. 283, 119402 (2024).

Benque, B. et al. Improvement of a pharmaceutical powder mixing process in a tote blender via DEM simulations. Int. J. Pharm. 658, 124224 (2024).

Giannis, K., Schilde, C., Finke, J. H. & Kwade, A. Modeling of high-density compaction of pharmaceutical tablets using multi-contact discrete element method. Pharmaceutics 13, 2194 (2021).

Grohn, P., Lawall, M., Oesau, T., Heinrich, S. & Antonyuk, S. CFD-DEM simulation of a coating process in a fluidized bed rotor granulator. Processes 8, 1090 (2020).

Chen, H. et al. A review on discrete element method simulation in laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. Addit. Manuf. Front. 1, 100017 (2022).

Nasato, D. S. & Pöschel, T. Influence of particle shape in additive manufacturing: discrete element simulations of polyamide 11 and polyamide 12. Addit. Manuf. 36, 101421 (2020).

Zhang, J., Tan, Y., Xiao, X. & Jiang, S. Comparison of roller-spreading and blade-spreading processes in powder-bed additive manufacturing by DEM simulations. Particuology 66, 48–58 (2022).

de Munck, M., Peters, E. & Kuipers, J. Fluidized bed gas-solid heat transfer using a CFD-DEM coarse-graining technique. Chem. Eng. Sci. 280, 119048 (2023).

Li, R., Duan, G., Yamada, D. & Sakai, M. Large-scale discrete element modeling for a gas-solid-liquid flow system. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 62, 17008–17018 (2023).

Diez, E. et al. Particle dynamics in a multi-staged fluidized bed: particle transport behavior on micro-scale by discrete particle modelling. Adv. Powder Technol. 30, 2014–2031 (2019).

Bierwisch, C., Kraft, T., Riedel, H. & Moseler, M. Three-dimensional discrete element models for the granular statics and dynamics of powders in cavity filling. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 57, 10–31 (2009).

Sakai, M. & Koshizuka, S. Large-scale discrete element modeling in pneumatic conveying. Chem. Eng. Sci. 64, 533–539 (2009).

Esser, P. et al. Scaling rectified flow transformers for high-resolution image synthesis. In Proceedings International Conference on Machine Learning, Vol. 235, 12606–12633 (PMLR, 2024).

Kloss, C., Goniva, C., Hager, A., Amberger, S. & Pirker, S. Models, algorithms and validation for opensource DEM and CFD-DEM. Prog. Comput. Fluid Dyn. 12, 140–152 (2012).

Chen, X. et al. Symbolic discovery of optimization algorithms. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 36, 49205–49233 (2023).

Marín Pérez, J., Comlekci, T., Gorash, Y. & MacKenzie, D. Calibration of the DEM sliding friction and rolling friction parameters of a cohesionless bulk material. Particuology 92, 126–139 (2024).

Beetstra, R., van der Hoef, M. A. & Kuipers, J. A. M. Drag force of intermediate Reynolds number flow past mono- and bidisperse arrays of spheres. AIChE J. 53, 489–501 (2007).

Lacey, P. M. C. Developments in the theory of particle mixing. J. Appl. Chem. 4, 257–268 (1954).

Shoeybi, M. et al. Megatron-LM: training multi-billion parameter language models using model parallelism. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1909.08053 (2019).

Xu, Y. et al. GSPMD: general and scalable parallelization for ML computation graphs. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2105.04663 (2021).

Sung, W., Shin, S. & Hwang, K. Resiliency of deep neural networks under quantization. arXiv preprint https://arxiv.org/abs/1511.06488 (2015).

Liu, Z. et al. Post-training quantization for vision transformer. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 28092–28103 (2021).

Coetzee, C. J. Calibration of the discrete element method. Powder Technol. 310, 104–142 (2017).

Lichtenegger, T., Peters, E. A. J. F., Kuipers, J. A. M. & Pirker, S. A recurrence CFD study of heat transfer in a fluidized bed. Chem. Eng. Sci. 172, 310–322 (2017).

Johnson, K. L. Contact Mechanics (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1985).

Kieckhefen, P., Pietsch, S., Dosta, M. & Heinrich, S. Possibilities and limits of computational fluid dynamics–discrete element method simulations in process engineering: a review of recent advancements and future trends. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 11, 397–422 (2020).

Anderson, T. B. & Jackson, R. O. Y. A fluid mechanical description of fluidized beds. Ind. Eng. Chem. Fundam. 6, 527–539 (1967).

Lu, L., Jin, P., Pang, G., Zhang, Z. & Karniadakis, G. E. Learning nonlinear operators via deeponet based on the universal approximation theorem of operators. Nat. Mach. Intell. 3, 218–229 (2021).

Li, Z. et al. Neural operator: Graph kernel network for partial differential equations. In ICLR 2020 Workshop on Integration of Deep Neural Models and Differential Equations https://openreview.net/forum?id=fg2ZFmXFO3 (2020).

Li, Z. et al. Fourier neural operator for parametric partial differential equations. In ICLR https://openreview.net/forum?id=c8P9NQVtmnO (2021).

Kovachki, N. B. et al. Neural operator: learning maps between function spaces with applications to pdes. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 24, 89:1–89:97 (2023).

Seidman, J., Kissas, G., Perdikaris, P. & Pappas, G. J. Nomad: nonlinear manifold decoders for operator learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 5601–5613 (2022).

Alkin, B. et al. Universal physics transformers. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 38, 25152–25194 (2024).

Lichtenegger, T. Local and global recurrences in dynamic gas-solid flows. Int. J. Multiph. Flow. 106, 125–137 (2018).

Lichtenegger, T. Data-assisted, physics-informed propagators for recurrent flows. Phys. Rev. Fluids 9, 024401 (2024).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. Adv. neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 5998–6008 (2017).

Peebles, W. & Xie, S. Scalable diffusion models with transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 4195–4205 (2023).

Perez, E., Strub, F., De Vries, H., Dumoulin, V. & Courville, A. Film: Visual reasoning with a general conditioning layer. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 32, 3942–3951 (2018).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In ICLR, Vol. 9 https://openreview.net/forum?id=YicbFdNTTy (2021).

Jaegle, A. et al. Perceiver: General perception with iterative attention. In Proceedings International Conference on Machine Learning, Vol. 139, 4651–4664 (PMLR, 2021).

Baevski, A. & Auli, M. Adaptive input representations for neural language modeling. In ICLR, Vol. 7 https://openreview.net/forum?id=ByxZX20qFQ (2019).

Acknowledgements

We would like to sincerely thank Dennis Just, Miks Mikelsons, Robert Weber, Bastian Best, the whole NXAI team, and the whole Emmi AI team for their ongoing help and support. We are grateful to Sepp Hochreiter, Phillip Lippe, Maurits Bleeker, Patrick Blies, Andreas Fürst, Andreas Mayr, Andreas Radler, Behrad Esgandari, and Daniel Queteschiner for their valuable inputs. Samuele Papa and Johannes Brandstetter thank Efstratios Gavves and Jan-Jakob Sonke for their help in making Samuele’s research exchange smooth and mutually beneficial. We acknowledge the EuroHPC Joint Undertaking for awarding us access to Karolina at IT4Innovations, Czech Republic, MeluXina at LuxProvide, Luxembourg, LUMI at CSC, Finland, and Leonardo at CINECA, Italy. The ELLIS Unit Linz, the LIT AI Lab, and the Institute for Machine Learning are supported by the Federal State of Upper Austria.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.A., T.K., and S.Pa. were the core contributors of this project. They implemented all aspects of NeuralDEM, such as the model architecture, the training and simulation workflows, and all experiments and evaluations. S.Pi. provided regular feedback and suggested potential target cases. T.L. and J.B. conceptualized and supervised all aspects of this project. B.A., T.K., S.Pa., T.L., and J.B. contributed to the writing and editing of the present manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alkin, B., Kronlachner, T., Papa, S. et al. NeuralDEM for real time simulations of industrial particular flows. Commun Phys 8, 440 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02342-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02342-4