Abstract

Light pulse atom interferometers (AIFs) are exquisite quantum probes of spatial inhomogeneity and gravitational curvature. Moreover, detailed measurement and calibration are necessary prerequisites for very-long-baseline atom interferometry (VLBAI). Here we provide a theoretical analysis of the phase resulting in a complex gravitational environment and introduce a novel interferometer geometry which singles out the phase shift proportional to the curvature of the gravitational potential. The scale factor depends only on well controlled quantities, namely the photon wave number, the interferometer time and the atomic recoil, which allows the curvature to be accurately inferred from a measured phase. As a case study, we numerically simulate such a gradiometric interferometer in the context of the Hannover VLBAI facility and prove the robustness of the phase shift in gravitational fields with complex spatial dependence. We define an estimator of the gravitational curvature for non-trivial gravitational fields and calculate the trade-off between signal strength and estimation accuracy with regard to spatial resolution. As a perspective, we discuss the case of a time-dependent gravitational field and corresponding measurement strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Light pulse atom interferometers (AIFs) are high-precision instruments used in a wide variety of research fields. Their versatility includes tasks such as determining the fundamental constants1,2,3,4, serving as quantum sensors to measure Earth’s gravitational field5,6,7, proposing measurements for gravitational wave detection8,9,10, exploring fundamental physics and alternative gravitational models11,12,13,14, and performing measurements related to time dilation and gravitational redshift15,16,17,18. In particular, their accuracy as sensors of gravitational fields and their gradients is becoming increasingly important for applications in civil engineering19, inertial sensing20, and geodesy21,22,23,24,25,26.

AIFs are utilized to measure the gravitational field, with gravimeters offering information about the linear gravitational acceleration g along the atomic trajectory. This approach is highly accurate because the leading order phase shift \(\Delta \Phi =gk{T}_{R}^{2}\) connects the desired value of g with the wave vector k and the interferometer time TR, both of which are often known with very high precision.

For measuring the (constant) gravitational gradient, a gradiometric experimental setup is employed, involving a comparison of g-measurements from two spatially separated gravimeters, effectively interpolating the g values between their spatial positions. Such gradiometric experiments are theoretically limited by the measurement uncertainty of the phase shift and the uncertainty of the height difference between the two interferometers. Another way to extract knowledge about the gravity gradient is done using more elaborate AIF geometries27. In these cases, however, the phase shift depends non-linearly on the gravitational field, making an estimation more complicated.

State-of-the-art AIFs are being constructed with increasingly longer baselines28,29,30,31 and more efficient large momentum transfer (LMT) techniques32,33,34, extending beyond the region where the assumption of a constant gradient of the gravitational field remains valid.

The transition to nontrivial gravitational curvature is not only a challenge for large baseline interferometers, but can also be seen as an opportunity for experiments with gravitational test masses. Deliberately introduced nontrivial gravitational fields, which allow the measurement of phases along the atomic trajectory to probe this non-linearity, have been exploited in refs. 35,36 and led to the proposed gravitational Aharonov–Bohm effect37. Measuring anomalies in the gravitational gradient is also used to detect inhomogeneities in the gravitational field19 and will become evermore important for civil engineering and quantum metrology. Resolving a spatially varying gravity gradient to high accuracy with a gradiometric AIF setup is, however, equivalent to comparing g-measurements in close proximity. This procedure is therefore increasingly error prone, because of the relative uncertainty in the position of the atomic ensembles, compared to the separation of the two constituent AIFs.

In this analysis, we introduce a novel geometry for AIFs that is exclusively sensitive to the gravitational curvature, that is, the gradient and higher-order derivatives of the gravitational field. The resulting phase depends, in an idealized model, on the gravity gradient, k, TR, and, additionally, on the atomic recoil ℏ/m, which is also known to high precision. Notably, such an AIF geometry does not require two distinct and spatially separated experimental setups; instead, it consists of two co-located AIFs, initialized at the same height. As a result, the measurement resolution of such a co-located gradiometric interferometer (CGI) is solely determined by the signal magnitude and is not constrained by a spatial separation between the constituent AIFs, i.e., the initial conditions of the constituent AIFs. For simplicity, we assume perfectly resonant (elastic) atomic transitions at every beam splitter and mirror pulse, since our goal is to understand how to interpret the phase shift results for complex gravitational environments.

As a case study, we simulate CGI schemes for the very-long-baseline atom interferometry (VLBAI) facility in Hannover, using its precisely known gravitational field38,39, and analyze the trade-off between signal strength and spatial resolution. Since the atoms sample and average a macroscopic portion of the gravitational field during their flight time, it is not clear a priori how to infer the gravitational curvature at a particular height from a measured phase shift. Our analysis will address and resolve this issue for the CGI and define a general estimator of the gravitational curvature within the framework of idealized atom-photon interactions and a time-independent gravitational background. We also highlight the importance of achieving temporal resolution of the gravitational field, and discuss how this novel AIF geometry might help to accomplish this task.

Results

Measurement of gravitational curvature

Throughout this analysis, we will assume one-dimensional movement of the AIF atoms along the z-axis of a local coordinate system, originating at a fixed height of the experiment and disregard Earth’s rotation. We denote the gravitational potential in the vicinity of the experimental setup by ϕ(z).

To start, we use an idealized gravitational potential

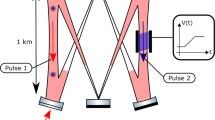

consisting of linear acceleration g and a constant gravity gradient Γ0. To be specific we refer to Γ(z) in general as gravitational curvature, i.e., the gravity gradient and possible higher order derivatives of the potential, as we include at a later step. Note that curvature, in a general relativistic sense, is defined via components of the Riemann curvature tensor. Those components are – to first order–second derivatives of the gravitational potential, as it is the case here. Geodesists, however, often refer to gravitational curvature as third order derivatives of the gravitational potential, i.e., the spatial variation of the gravity gradient. We will focus on the CGI depicted in Fig. 1, consisting of a MZI with 2Nℏk momentum transfer and a SDDI with an initial photon kick of Nℏk in each direction. Regarding potential experimental implementations of the first beam splitter pulse of this geometry, we refer to the analysis in Supplementary Note 3.

The symmetric double diffraction interferometer (SDDI) is depicted in green, the Mach-Zehnder inteferometer (MZI) in blue. The gravitational field is sourced by the mass density ρ(r, t). a Position of the CGI in a large baseline interferometry setup as determined by the initial height z0. CGI geometry shown in more detail (b) in the laboratory frame and c in the freely falling frame. Δh is the length between the initial height z0 and the atomic apex, TR is the time between the laser pulses. \(\left\vert N\right\rangle\) denotes a momentum eigenstate with N momentum quanta, as compared to the initial wave packet. The speed of light was set infinite for the laser pulses in this plot.

The key finding of the work is, that all the dominant phase shifts in each individual AIF cancel out and that the resulting dominant phase shift is given by

This phase shift is proportional to gravitational curvature Γ0 with a well-controlled scale factor \(f=2{N}^{2}\hslash {k}^{2}{T}_{R}^{3}/m\). In order to analyze where this asymmetry in the AIF output results from, we recapitulate that the phase difference at the output port of an AIF originates from three main components40,41,42,43: the propagation phase ΔΦProp, the kick phase ΔΦKick, and the separation phase ΔΦSep. Specifically, all our calculations are conducted in the reference frame where the laser sources are stationary within Earth’s gravitational field, and the atoms fall freely, interacting instantaneously with the light fields as for example in refs. 40,44. To be precise, while we account for the finite speed of light between the laser source and the interaction height, we assume that the atom-light interaction itself occurs instantaneously. The propagation phase is calculated as the difference of the action functional along the upper and lower atomic path. If we denote the classical Lagrangian of an atom of mass m as \(L(z(t))=\frac{m}{2}\dot{z}{(t)}^{2}-m\phi (z(t))\), the propagation phase can be compactly written as

where zup(t) and zlow(t) are the solutions to the classical equations of motion for the atoms on the upper and lower trajectory in the time interval [Tinitial, Tfinal], and the global minus sign is conventional. We note that if the gravitational potential is of at most quadratic order in z, the expression for the propagation phase is exact and not merely an approximation.

The kick phase is determined by the difference in the imprinted AIF laser phases along each path. It contributes positively to the total phase when the atom gains momentum in the process and negatively, when it loses momentum. One can model this, for example, by an interaction potential

where at a time ti a momentum of ℏki is transferred, as it was done in ref. 45. Finally, the separation phase40 is computed by multiplying the average output momentum \(\overline{p}\) in one of the output ports – we choose the 0ℏk-port – with the separation of the atomic wave packets Δz, i.e., \(\Delta {\Phi }_{{{\rm{Sep}}}}=\Delta z\cdot \overline{p}\). Furthermore, the separation phase is usually compensated, since a non-trivial separation at the output port gives rise to a loss of contrast.

Solving the Euler-Lagrange equation for this potential with initial conditions z0 and v0 results in an atomic trajectory of the form

When evaluating the the trajectories for the upper and lower AIF paths of the MZI and SDDI, cf. Fig. 1, we assume identical initial conditions z0 and v0 for both interferometers before the first beam splitter, and account for the different photon recoils by the respective momentum kicks at t = 0. Evaluating the trajectories for the AIF paths at the time t = TR of the mirror pulse results in positions

for the upper and the lower arm of the MZI, and analogously for the SDDI in

It is the asymmetry of the trajectories in Eqs. (6) and (7) due to the photon recoil that ultimately leads to differences in the sensitivity of the MZI and SDDI regarding gravitational curvature. The majority of phase contributions in an AIF scale with the enclosed spacetime area, which is identical in both the MZI and SDDI configurations shown in Fig. 1. However, ΔΦCurv arises exclusively in the MZI and vanishes in the SDDI, indicating that this particular phase contribution remains unchanged in the differential setup.

In our theoretical framework, the phase shift is consistently calculated at the 0ℏk output port of each AIF. Within this setup, the curvature phase shift is attributed solely to arise within the MZI. Specifically, it is the asymmetry in the atomic trajectory that influences the propagation phases. In detail, we have

where Eq. (8b) holds up to negligible relativistic corrections (commented on in the Supplementary Note 1). The additional phase in the MZI results from the propagation phase in the time interval [TR, 2TR] along the \(\frac{m}{2}{\Gamma }_{0}z{(t)}^{2}\) part of the Lagrangian–especially due to a non-vanishing photon-recoil asymmetry in the initial heights in z(t), as seen in Eqs. (6) and (7). In contrast, this contribution vanishes in the SDDI, since both \({z}_{{{\rm{up}}}}^{{{\rm{SDDI}}}}{({T}_{R})}^{2}\) and \({z}_{{{\rm{low}}}}^{{{\rm{SDDI}}}}{({T}_{R})}^{2}\) will exhibit identical photon-recoil dependent phase contributions, thereby nullifying any output signal. In a differential measurement setup one is therefore left with a net contribution of propagation phases consisting of the phase of interest, as given in Eq. (2). A complete evaluation of phases as outlined before reveals that this is in fact the dominant signal in the differential phase of a MZI and a SDDI. Note that, so far, no scheme for gravity gradient mitigation46,47,48 has been included for the considered interferometer setup; thus, each constituent AIF will have a non-trivial wave-packet separation at the output port, leading to a possible loss of contrast. However, applying the same frequency shift to both interferometers in the mirror pulse will not result in a different differential phase shift, therefore opening up the possibility to include a (common) detuning for the two constituent AIFs, increasing each one’s contrast, without altering the phase shift.

The results of a comprehensive account of phases along the lines of49 are summarized in Table 1. The first contribution, i.e., term #1, \(2Nkg{T}_{R}^{2}\), is the well known phase due to linear gravity. The next three phases (#2 − #4) connect the gravity gradient with the initial conditions z0, v0 and the linear gravitational acceleration – each of which are identical for the MZI and SDDI. The fifth contribution is the phase of interest and provides the dominant contribution in the differential signal of both interferometers. The remaining phases (#6 − #10), of which some contribute to the differential propagation phase Eq. (2), are related to the Doppler effect or relativistic corrections and are at least ten orders of magnitude smaller than the fifth phase, if one assumes the numerical values: ωR = 107 Hz, Nk = 4 × 106 m−1, m = 87 amu, TR = 0.6 s, z0 = 5 m, v0 = 6 m/s, g = 9.81 m/s2 and Γ0 = −2.7 × 10−6 Hz2 = −2.7 × 103 E. These values correspond to a typical atomic fountain using Rubidium and Bragg transitions with a baseline of roughly 2 m without LMT. The value of the gravity gradient corresponds to the approximate average value within the VLBAI facility in Hannover. More details on each of the phase contributions and their origin are given in the Supplementary Note 1.

The phase in Eq. (2) corresponds to the dominant phase discussed by Asenbaum et al. in ref. 35, where it was phrased as a ‘tidal phase’. In this reference, the phase arises from the differential signal of two spatially separated MZIs, one of which is in close proximity to a gravitational test mass inducing a local gravitational gradient. The gravity gradient Γ0 is denoted by Asenbaum et al.35 by Tzz. The factor of 4 difference in the expression for the tidal phase results from a difference in the number of imprinted photon momenta in the MZIs. The same phase has also been discussed before by Dimopoulos et al.50, where it was referred to as a ‘1st gradient recoil’. It is worth noting that one can interpret this phase as a ‘gradient correction’ of the recoil phase ΔΦrecoil = ℏN2k2TR/m, which is at the heart of the AIF measurements of the fine-structure constant1,2.

Having an analytic form of this phase shift, see Eq. (2), reveals the key advantage of this geometry – namely, the direct proportionality of the phase shift to Γ0 and the very accurately known quantities k, TR and ℏ/m, enabling to measure the gravity gradient with an accuracy determined by the phase shift measurement. To emphasize this point once more: Either, phase shifts that are directly proportional to the gravity gradient depend either on the initial conditions z0 and v0 (terms #3, #4), which have a comparably high measurement uncertainty if they are not controlled via coherent processes51, particularly for smaller baselines. Or they exhibit a non-linear dependence on the gravitational field, i.e., they scale with g(z) ⋅ Γ(z) as in ref. 27, making the inversion complicated for complex gravitational fields (term #5).

We have now demonstrated how the gravity gradient can be extracted using a novel differential setup, utilizing only the spatial dimensions of a single interferometer. However, up to this point, we have considered an idealized gravitational potential with a constant gravitational gradient. In real-life experiments, this assumption will inevitably be violated to varying extents, as will be discussed in the next section at the example of the VLBAI setup located in Hannover. The (classically) measured gravitational field in this experimental setup offers a chance to analyze whether the CGI continues to extract information about the gravitational gradient, to understand the averaging process along the atomic trajectory, and, most importantly, to identify any errors that may arise in the interpretation of real-life phase shift data.

Non-ideal gravitational fields

In real world applications, the gravitational field will not always be sufficiently described in the idealized fashion of Eq. (1), such that one needs to analyze higher order effects. Expanding the potential in a neighborhood of the origin of the local coordinate system in a general Taylor expansion yields

where the summation must be carried to a considerable order Npot, depending on the complexity of the gravitational environment, as we will discuss below. Similarly to before we can now write

with a generalized curvature phase

Here \({{{\mathcal{A}}}}_{{{\rm{MZI}}}}(n)\), \({{{\mathcal{A}}}}_{{{\rm{SDDI}}}}(n)\) are geometry dependent quantities. One can write \({{{\mathcal{A}}}}_{{{\rm{MZI}}}}(n)\) as

which coincides with the spacetime area of the MZI for n = 1. The formula for the SDDI is completely analogous. Approximations underlying Eq. (10) are discussed in the Supplementary Note 1. Additional phase contributions arising from finite speed of light (FSL) and their mitigation are discussed in Supplementary Note 2. The theoretical analysis in this work and the derivation of Eqs. (2) rely on a semiclassical approach40,42, which was explained in great detail in ref. 49. Alternatively, perturbation theory methods45 or the use of the midpoint theorem52,53 are also possible. Note that there is no n = 1 contribution in ΔΦCurv. This means that phase shifts resulting from linear gravitational acceleration g cancel in this geometry to leading order, as we have seen for the example of an idealized gravitational potential of second order in Eq. (1) and for the explicit gravitational field of VLBAI Hannover in the next section.

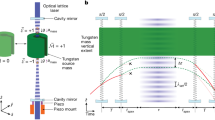

Gravitational background of the VLBAI Hannover

In VLBAI facilities under construction around the world29,30,54, despite the best efforts to thermally and magnetically shield the atoms from the outside world, gravitational non-linearities can hardly be compensated for by additional masses. Especially temporarily varying mass distributions, such as ground water or even laboratory equipment and concrete structures may alter the gravitational field that the atoms experience during each AIF sequence. At the VLBAI facility in Hannover, a high-precision measurement campaign was carried out with classical sensors to understand the gravitational field – and its fluctuations – along the 10 m baseline of the interferometer38,39. Figure 2 displays the measured gravitational non-linearity of the gravity gradient as a function of height, which varies in the range of about 10−7 s−2, i.e., 10−6 g/m. The variations correlate with the building structure, cf. Fig. 2.

a Vertical profile of the VLBAI Hannover within the HITec building. Cross-section taken from ref. 38 and adapted. b Gravitational acceleration g(z) and c gravitational gradient Γ(z) as functions of height in the region of interest (ROI) (0–8 m) of VLBAI. g(z) is interpolated by a polynomial fit, Γ(z) is the spatial derivative of this fit. Reference acceleration gref = 9.812 m/s2.

In the following we will discuss our differential measurement scheme for the VLBAI Hannover. We start by analyzing multiple CGI sequences from Fig. 1, where the MZI spans height difference of Δh, with varying initial heights z0. The apex of each atomic trajectory will be obtained at t = TR, which is achieved by setting v0 = gTR and \({T}_{R}=\sqrt{2\Delta h/g}\). For simplicity we will always analyze such trajectories in this section, such that one can view Δh and TR interchangeably. Due to the non-uniform nature of the gravitational potential, it is not immediately evident how to convert a phase shift measurement into an accurate estimate of the gravitational quantity of interest. This challenge arises because the atoms sample a macroscopic portion of the gravitational field along their path, effectively interacting with non-trivially averaged versions of g and Γ throughout their trajectories. Note that the (idealized) dominant phase shift in Eq. (2) is cubic in time, which hints to the fact that the averaging procedure is governed by the time exponent of the idealized phase shift. Based on our numerical simulations, we can confirm that the gravitational gradient at a certain height has a direct correlation with the phase shift of the CGI, where the atomic initial height is shifted by the cubic mean of the atomic position along its trajectory

Connecting this finding with the previously introduced scale factor f one can define an estimator for the gravity gradient by

Note that f arises from the idealized description of the CGI and should therefore yield an especially good approximation for the actual, but unknown, scale factor for small Δh. Figure 3a shows the excellent agreement with the correct gravity gradient Γ(z0) for small baselines Δh, i.e., high spatial resolutions. We furthermore illustrate how increasing the baseline – and thus the average phase shift – results in a higher root mean-square error \(\Delta \hat{\Gamma }\) in the estimation of the gravity gradient in Fig. 3b.

a Comparison of the measured phase shift ΔΦ(z0) (black), the gravity gradient Γ(z0) from Fig. 2 (orange), and the estimator for the gravity gradient \(\hat{\Gamma }({z}_{0})\) from Eq. (12) (red dashed) for three different values of TR (and therefore Δh), i.e., different choices of measurement resolution. b Phase shift magnitude for co-located gradiometric interferometers (CGIs) with varying baselines Δh and corresponding root mean-square error in the estimation of the gravity gradient. \(\Delta \hat{\Gamma }\) is averaged over all possible initial heights in the VLBAI's region of interest (ROI) obtainable with a baseline of Δh and 〈Γ〉 = 2.75 × 103 E is the magnitude of the mean gravitational gradient of the facility.

These findings highlight the critical importance of having a thorough understanding of the gravitational environment in VLBAI facilities, since the connection between the measured phases and the corresponding height this estimation belongs to were previously unclear. This knowledge is particularly crucial when the objective is to detect signals from additional test masses or even gravitational waves.

Discussion

We have introduced a novel differential setup to measure gravitational curvature and have simulated its behavior in a complex gravitational field. Furthermore, we defined an estimator for the gravity gradient that aligns with the true value within a 1% margin for interferometers with baselines up to 3.5 m. The question of determining the appropriate averaging procedure to achieve alignment between the AIF phase and the gravitational signal, as in our case with the gravitational gradient case, is inherently complex, especially for arbitrary gravitational fields. Future work on this topic will be necessary, especially if one wants to measure gravitational waves or dark matter with earthbound experiments, with more elaborate interferometer geometries. This is because gravitational perturbations and non-linearities cannot be effectively shielded in those setups and must therefore be characterized with high accuracy. For example, in the VLBAI facility in Hannover targeting among others high precision gravimetry, the gravity gradient changes by approximately 300 E over the whole baseline. Moreover, constructions such as underground tunnels, modify the gravitational field and can be detected by gravity gradient measurements55 as exemplified by Stray et al.19 employing a conventional gradiometer using two MZIs. (There are deviation of about 150 E required a phase resolution of 17.5 mrad.).

Another alternative strategy to measure the gravity gradient involves the mitigation techniques46,47,48. For the idealized gravitational potential from Eq. (1), these schemes modify one of the AIF pulse as \(k \, \mapsto (1+{\Gamma }_{0}{T}_{R}^{2}/2)\,k\), reducing the wave-packet separation at the output port to achieve higher contrast. By scanning through different pulse detunings and identifying the highest contrast of the interference signal, one can infer the value of Γ0 from the optimal detuning frequency. This approach is experimentally simple, but requires multiple AIF experiments to scan various detuning frequencies. The repetition presents a challenge, especially for time-varying gravitational fields, which may cause temporal variations in Γ(z). Also, similar to this analysis, one needs to analyze which averaging procedure for Γ(z) is involved for the detuning parameter that results in the highest contrast. Additionally one should keep in mind that not only a gravitational gradient would cause a misalignment at the output port, but a variety of different effects, ranging from uncontrolled magnetic field fluctuations to imperfect laser systems, could lead to a wave-packet separation, therefore masking the true value of the gravitational gradient.

Until now, we have assumed the gravitational background near the interferometric baseline to be constant in time. This assumption, however, is not valid, especially for large experimental setups with baselines of 100 m or more56,57. Variations in ground and surface water ρWater(t), seismic activity ρEarth(t), and even air pressure differentials ρAir(t) can significantly impact the experimental outcomes. It could therefore be beneficial to include an array of these newly described AIFs with an extension of Δh and separation Δl along the baseline of a large scale experiment. Ideally, this array would be located in a parallel shaft, measuring the gravitational field in real time, while other interferometric experiments are done in the main experimental facility. This array of AIFs should be seen as an integral part of the experimental setup and would be used to gauge and interpret the phase shifts of the other measurements.

Depending on the frequency of variations in the gravitational potential, Δh and Δl can be adjusted suitably to obtain a time- and height-resolved measurement of the gravitational field along the baseline. However, the temporal fluctuations of the gravitational field can–a priori–span a broad frequency domain. Consider, for the moment, that one wants to resolve changes in the gravitational field with a frequency centered around ν, and that each AIF run takes a time \(2{T}_{R}=2\sqrt{2\Delta h/g}\). Firstly, we know that ν−1 > 2TR, which constrains TR, i.e., Δh. This can be challenging for very high frequencies ν, as a smaller TR results in a smaller phase shift, which must still be greater than the measurement uncertainty. Assuming a minimal phase resolution of 1 mrad, N = 4, and the phase output of the AIF being dominantly given by Eq. (2), this would require a minimal interferometer time of TR≥ 0.3 s, corresponding to a maximum variation frequency of the gravitational field of ν ≤ 3.3 Hz. This would enable measurements of Earth’s primary and secondary micro-seismic frequency peaks, which are both below 1 Hz, see ref. 56. Note that multiple concurrent interferometer setups like those could, however, improve the sampling frequency and allow for resolutions of even faster gravitational field fluctuations.

Secondly, the choice of Δl depends on the complexity of the (static) gravitational potential and the measurement uncertainties of g(z) and Γ(z) given by the previously determined value of Δh. The separation between each interferometer height should be chosen such that it resolves the spatial and temporal changes, possibly by choosing non-uniform separations between each interferometer, i.e., tighter spacing, when the gravitational field is especially non-trivial in space or time.

Extending this concept, one could strategically position gravitational anharmonicities, such as test masses, near the AIF baseline to explore the intricate interplay between quantum mechanics and gravity with greater precision. Phenomena such as the ‘gravitational Aharonov–Bohm’ effect37 and the fundamental interaction between quantum matter and (classical) gravitational fields require a precise interpretation of phase shifts, possibly reaching sub-mrad scales. Therefore, the analysis presented here serves as a crucial preliminary step towards achieving such goals.

To summarize, we introduced a novel AIF geometry designed to exhibit high sensitivity in the measurement of gravitational gradients. In addition, we performed numerical simulations to analyze the behavior of this AIF sequence in the gravitational field of the VLBAI facility in Hannover, Germany. Our results provide new insights into the interpretation of phase shift data in complex gravitational environments. This analysis serves as a case study for VLBAI, highlighting the critical role of accurate gravitational models in state-of-the-art atom interferometry experiments with baselines longer than 10 m and shows how one would construct an estimator for the gravity gradient in such non-trivial gravitational fields. It should be noted that we idealized the atom-light interaction by assuming instantaneous and lossless processes. We also disregarded Earth’s rotation. Actual VLBAI will experience a variety of different error sources, which need to be included in the theoretical description – especially when it comes to gravitational uncertainties, i.e., resulting from geographical position or a (gravitationally) noisy lab environment in general and are subject to future work.

Data availability

The numerical and algebraic phase shift calculations that support the findings of this study are available in58.

Code availability

All numerical results and figures were generated using the open-source Python algorithm referenced in58.

References

Parker, R. H., Yu, C., Zhong, W., Estey, B. & Müller, H. Measurement of the fine-structure constant as a test of the standard model. Science 360, 191–195 (2018).

Morel, L., Yao, Z., Cladé, P. & Guellati-Khélifa, S. Determination of the fine-structure constant with an accuracy of 81 parts per trillion. Nature 588, 61–65 (2020).

Rosi, G., Sorrentino, F., Cacciapuoti, L., Prevedelli, M. & Tino, G. Precision measurement of the Newtonian gravitational constant using cold atoms. Nature 510, 518–521 (2014).

Schelfhout, J. S., Hird, T. M., Hughes, K. M. & Foot, C. J. A single-photon large-momentum-transfer atom interferometry scheme for Sr or Yb atoms with application to determining the fine-structure constant https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.10225 (2024).

Wu, X. et al. Gravity surveys using a mobile atom interferometer. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax0800 (2019).

del Aguila, R. P. et al. Bragg gravity-gradiometer using the 1S0–3P1 intercombination transition of 88Sr. N. J. Phys. 20, 043002 (2018).

Fang, B. et al. Metrology with atom interferometry: Inertial sensors from laboratory to field applications. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 723, 012049 (2016).

Beaufils, Q. et al. Cold-atom sources for the Matter-wave laser Interferometric Gravitation Antenna (MIGA). Sci. Rep. 12, 19000 (2022).

Chen, Z., Louie, G., Wang, Y., Deshpande, T. & Kovachy, T. Enhancing strontium clock atom interferometry using quantum optimal control. Phys. Rev. A 107, 063302 (2023).

Canuel, B. et al. ELGAR-a European laboratory for gravitation and atom-interferometric research. Class. Quantum Gravit. 37, 225017 (2020).

Schlippert, D. et al. Quantum test of the universality of free fall. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 203002 (2014).

Damour, T. Theoretical aspects of the equivalence principle. Class. Quantum Gravit. 29, 184001 (2012).

Colladay, D. & Kostelecký, V. A. CPT violation and the standard model. Phys. Rev. D. 55, 6760–6774 (1997).

Asenbaum, P., Overstreet, C., Kim, M., Curti, J. & Kasevich, M. A. Atom-interferometric test of the equivalence principle at the 10−12 level. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 191101 (2020).

Loriani, S. et al. Interference of clocks: a quantum twin paradox. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax8966 (2019).

Roura, A., Schubert, C., Schlippert, D. & Rasel, E. M. Measuring gravitational time dilation with delocalized quantum superpositions. Phys. Rev. D. 104, 084001 (2021).

Zych, M., Costa, F., Pikovski, I. & Brukner, Č. Quantum interferometric visibility as a witness of general relativistic proper time. Nat. Commun. 2, 1–7 (2011).

Di Pumpo, F. et al. Gravitational redshift tests with atomic clocks and atom interferometers. PRX Quantum 2, 040333 (2021).

Stray, B. et al. Quantum sensing for gravity cartography. Nature 602, 590–594 (2022).

Geiger, R., Landragin, A., Merlet, S. & Pereira Dos Santos, F. High-accuracy inertial measurements with cold-atom sensors. AVS Quantum Sci. 2, 024702 (2020).

Antoni-Micollier, L. et al. Detecting volcano-related underground mass changes with a quantum gravimeter. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL097814 (2022).

Bidel, Y. et al. Absolute marine gravimetry with matter-wave interferometry. Nat. Commun. 9, 627 (2018).

Bidel, Y. et al. Absolute airborne gravimetry with a cold atom sensor. J. Geod. 94, 1–9 (2020).

Farah, T. et al. Underground operation at best sensitivity of the mobile LNE-SYRTE cold atom gravimeter. Gyroscopy Navigation 5, 266–274 (2014).

Haagmans, R., Siemes, C., Massotti, L., Carraz, O. & Silvestrin, P. ESA’s next-generation gravity mission concepts. Rendiconti Lincei. Sci. Fisiche e Nat. 31, 15–25 (2020).

Lévèque, T. et al. CARIOQA: Definition of a Quantum Pathfinder Mission https://www.spiedigitallibrary.org/conference-proceedings-of-spie/12777/127773L/CARIOQA-definition-of-a-Quantum-Pathfinder-Mission/10.1117/12.2690536.full (2022).

McGuirk, J. M., Foster, G. T., Fixler, J. B., Snadden, M. J. & Kasevich, M. A. Sensitive absolute-gravity gradiometry using atom interferometry. Phys. Rev. A 65, 033608 (2002).

Coleman, J. MAGIS-100 at Fermilab. arXiv preprint https://arxiv.org/abs/1812.00482 (2018).

Badurina, L. et al. AION: an atom interferometer observatory and network. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2020, 011 (2020).

Zhan, M.-S. et al. ZAIGA: Zhaoshan long-baseline atom interferometer gravitation antenna. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D. 29, 1940005 (2020).

Abend, S. et al. Terrestrial very-long-baseline atom interferometry: Workshop summary. AVS Quantum Sci. 6, 32–44 (2024).

Plotkin-Swing, B. et al. Three-path atom interferometry with large momentum separation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 133201 (2018).

Rodzinka, T. et al. Optimal floquet engineering for large scale atom interferometers. Nat. Commun. 15, 10281 (2024).

Li, J., Kovachy, T., Bonacum, J. & Shahriar, S. M. Sensitivity of a point-source-interferometry-based inertial measurement unit employing large momentum transfer and launched atoms. Atoms 12, https://www.mdpi.com/2218-2004/12/6/32 (2024).

Asenbaum, P. et al. Phase shift in an atom interferometer due to spacetime curvature across its wave function. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 183602 (2017).

Asenbaum, P., Overstreet, C. & Kasevich, M. A. Matter waves and clocks do not observe uniform gravitational fields. Phys. Scr. 99, 046103 (2024).

Overstreet, C., Asenbaum, P., Curti, J., Kim, M. & Kasevich, M. A. Observation of a gravitational Aharonov-Bohm effect. Science 375, 226–229 (2022).

Schilling, M. et al. Gravity field modelling for the Hannover 10 m atom interferometer. J. Geodesy 94, 122 (2020).

Lezeik, A. et al. Understanding the gravitational and magnetic environment of a very long baseline atom interferometer. In Proc. Ninth Meeting on CPT and Lorentz Symmetry, 64–68 (World Scientific, 2023).

Hogan, J. M., Johnson, D. & Kasevich, M. A. Light-pulse atom interferometry. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.0806.3261 (2008).

Bordé, C. J. Atomic interferometry with internal state labelling. Phys. Lett. A 140, 10–12 (1989).

Storey, P. & Cohen-Tannoudji, C. The Feynman path integral approach to atomic interferometry. A tutorial. J. de. Phys. II 4, 1999–2027 (1994).

Kasevich, M. & Chu, S. Atomic interferometry using stimulated Raman transitions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 181–184 (1991).

Dimopoulos, S., Graham, P. W., Hogan, J. M. & Kasevich, M. A. Testing general relativity with atom interferometry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 111102 (2007).

Ufrecht, C. & Giese, E. Perturbative operator approach to high-precision light-pulse atom interferometry. Phys. Rev. A 101, 053615 (2020).

D’Amico, G. et al. Canceling the gravity gradient phase shift in atom interferometry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 253201 (2017).

Roura, A. Circumventing Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle in atom interferometry tests of the equivalence principle. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 160401 (2017).

Overstreet, C. et al. Effective inertial frame in an atom interferometric test of the equivalence principle. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 183604 (2018).

Werner, M. et al. Atom interferometers in weakly curved spacetimes using Bragg diffraction and Bloch oscillations. Phys. Rev. D. 109, 022008 (2024).

Dimopoulos, S., Graham, P. W., Hogan, J. M. & Kasevich, M. A. General relativistic effects in atom interferometry. Phys. Rev. D. 78, 042003 (2008).

Loriani, S. et al. Resolution of the colocation problem in satellite quantum tests of the universality of free fall. Phys. Rev. D. 102, 124043 (2020).

Bordé, C. J. Atomic clocks and inertial sensors. Metrologia 39, 435 (2002).

Antoine, C. & Bordé, C. J. Quantum theory of atomic clocks and gravito-inertial sensors: an update. J. Opt. B: Quantum Semiclassical Opt. 5, S199 (2003).

Dickerson, S. M., Hogan, J. M., Sugarbaker, A., Johnson, D. M. S. & Kasevich, M. A. Multiaxis inertial sensing with long-time point source atom interferometry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 083001 (2013).

Snadden, M., McGuirk, J., Bouyer, P., Haritos, K. & Kasevich, M. Measurement of the Earth’s gravity gradient with an atom interferometer-based gravity gradiometer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 971 (1998).

Mitchell, J., Kovachy, T., Hahn, S., Adamson, P. & Chattopadhyay, S. MAGIS-100 environmental characterization and noise analysis. J. Instrum. 17, P01007 (2022).

Abe, M. et al. Matter-wave atomic gradiometer interferometric sensor (MAGIS-100). Quantum Sci. Technol. 6, 044003 (2021).

Werner, M. & Hammerer, K. Local measurement scheme of gravitational curvature using atom interferometers. https://data.uni-hannover.de/dataset/61114e88-4a5f-4f29-a7fc-11b3c60864c8 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dorothee Tell and Philip Schwartz for insightful discussions. This work was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy (EXC-2123 QuantumFrontiers Grants No. 390837967), through CRC 1227 (DQ-mat) within Projects No. A05, B07, B09 and through the QuantERA 2021 co-funded project No. 499225223 (SQUEIS), and the German Space Agency (DLR) with funds provided by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK) due to an enactment of the German Bundestag under Grants No. 50WM2253A (AI-Quadrat). MW, KH and NG acknowledge funding by the AGAPES project - grant No 530096754 within the ANR-DFG 2023 Programme.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.W., K.H., N.G., D.S., and E.M.R. initiated the research direction, M.W. and K.H. developed the analytical and numerical modeling, M.W. created the figures and drafted the initial manuscript, A.L. and D.S. provided the gravitational model of the VLBAI Hannover, D.S., E.M.R., N.G., and K.H. supervised the project. All authors actively participated in discussing the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Werner, M., Lezeik, A., Schlippert, D. et al. Local measurement scheme of gravitational curvature using atom interferometers. Commun Phys 8, 463 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02396-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02396-4