Abstract

A plethora of next-generation all-optical devices based on exciton-polaritons have been proposed in latest years, including prototypes of transistors, switches, analogue quantum simulators and others. However, for such systems consisting of multiple polariton condensates, it is still challenging to predict their properties in a fast and accurate manner. The condensate physics is conventionally described by polariton Gross-Pitaevskii equations (GPEs). While GPU-based solvers currently exist, we propose a significantly more efficient machine-learning-based Fourier neural operator approach to find the solution to the GPE coupled with exciton rate equations, trained on both numerical and experimental datasets. The proposed method predicts solutions almost three orders of magnitude faster than CUDA-based solvers in numerical studies, maintaining the high degree of accuracy. Our method not only accelerates simulations but also opens the door to faster, more scalable designs for all-optical chips and devices, offering promising implications for quantum computing, neuromorphic systems, and various photonic applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the decades a wide range of all-optical devices, from switches1,2,3,4,5,6,7 and transistors8,9,10 to analogue quantum simulators11,12 and neuromorphic computing13,14,15,16,17,18, have been reported. In particular, exciton-polariton-based devices have emerged, capitalizing on the nonlinearities and unique propagation properties of these quasiparticles19. A notable example is the optically activated transistor switch, initially designed for cryogenic conditions using polariton condensates8, with recent advances enabling ambient operation9,10. Further progress of all-optical devices necessitates the development of precise and adaptable simulation tools. Just as Electronic Design Automation (EDA) played a pivotal role in the evolution of chip design, there is a pressing need for emulators that can capture the rich nonlinear characteristics inherent in optical devices. However, accurately predicting the behavior of systems with multiple coupled polariton condensates presents significant computational challenges. The complexity of solving the driven-dissipative polariton equations, which couple the condensate dynamics with reservoir evolution grows dramatically with the number of condensates, making conventional numerical methods computationally expensive for large-scale systems such as polariton chains, lattices, or graphs. Moreover, conventional approaches face scalability limitations when simulating extensive polariton networks, particularly for systems requiring high spatial resolution (e.g., 1024 × 1024 grid size20). In this connection, rapid development of machine learning (ML) techniques holds great potential for overcoming these computational bottlenecks and offers a chance to revolutionise polaritonics.

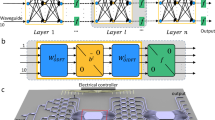

The microcavity exciton-polariton (hereafter polariton) system21 consists of two strongly coupled components: excitons confined in an active material and photons trapped in a microcavity. Polaritons can form condensates, i.e., a macroscopic coherent quantum state19, and they interact over large distances through ballistic propagation, forming many-body systems such as dyad22,23, chain24,25, lattice11,26 or graph11 (see example in Fig. 1a). In non-resonant pumping schemes (Fig. 1b), condensation occurs through a multi-step process involving hot electron-hole plasma cooling, excitons forming along the lower polariton branch, parametric scattering, and ultimately condensate formation above threshold27,28. Unlike equilibrium condensates described by the conventional Gross-Pitaevskii equation (GPE), polariton condensates are intrinsically driven-dissipative systems, requiring a fundamentally different theoretical framework. In the polariton GPE29, the excitonic reservoir acts as both a gain by feeding particles into the condensate through stimulated scattering and a source of repulsive interactions that shape the condensate’s spatial profile (see Methods for theoretical details).

a The upper layer shows the nonresonant pump profile featuring three Gaussian spots, while the lower one shows the wavefunction density of the condensates at the final time. Three white dashed lines indicate the central positions of the pump regions and align with their corresponding locations on the condensate density map. b Depiction of the scattering process, tracing the transition from the hot electron-hole plasma phase, through the reservoir cooling phase, to the scattering in the condensates. Only the lower polariton branch of the polariton energy mode is shown here.

Advances in semiconductor microcavity fabrication and spatial light modulators (SLMs) have enabled diverse nonlinear phenomena and pump profile manipulation, revealing applications from condensate amplifiers28,30 and waveguides31,32,33,34 to quantum computing35. Among these systems, polariton graphs while showing potential in solving optimization problems and simulating physical models such as Ising, XY, and Heisenberg systems11,36, pose the most significant computational challenge due to their complexity, diversity and irregularity. To this aim, robust solutions to the polariton GPE29 are essential. While parallel computing powered and GPU-based GPE solvers exist for both uniform37,38,39,40 and non-uniform meshes41, they struggle with the computational demands of large-scale polariton networks. Even with GPU acceleration, the simulation time scales unfavorably with system size. The Fourier Neural Operator (FNO)42 offers a promising alternative by learning mappings in Fourier space using a fixed number of modes (see Methods for architecture details), making its learnable parameters independent of spatial discretization, enabling efficient scaling to large systems. Various ML architectures have been proposed for partial differential equation (PDE) solutions, including convolution-based methods, like U-Net43 and operator-learning methods such as Deep Operator Networks44, Graph Neural Operators45, Multipole Graph Neural Operators46, FNOs42 and Physics-informed Neural Operators47. Though convolution-based methods achieve good accuracy, they fail to scale efficiently to larger systems. Operator-learning methods overcome this by learning mappings between infinite-dimensional spaces enabling predictions at different discretisation at a similar speed.

The FNO architecture (see Methods) operates by learning integral operators in Fourier space through spectral convolutions. This spectral approach efficiently captures global dependencies, making it particularly suitable for PDEs with long-range interactions like those in polariton systems. We specifically chose FNO, a specific variant of Neural Operator, over other ML approaches, as their spectral formulation directly parallels the split-step Fourier method (SSFM) used to solve the polariton GPE (see SSFM-FNO correspondence in Methods). Additionally, the FNO learns the solution operator mapping between function spaces rather than specific numerical solutions tied to fixed PDE parameters, enabling generalization across different pump configurations and system conditions. In this work, we apply the FNO architecture to approximate polariton GPE solutions. To develop this approach, we first generate comprehensive numerical datasets comprising 11,220 simulations and 156 experimental measurements of polariton condensate configurations under varying pump conditions. We then train a 4-layer FNO architecture with 128 Fourier modes retained in each spatial dimension to learn the mapping from pump profiles to steady-state condensate densities (see Methods and Supplementary Notes 2–5 for complete architecture and implementation details). The advantage of the FNO method is a significant speedup of the result, which is especially useful in the case of simulations with many parameters. While SSFM requires iterative time-stepping with a small interval, in the FNO approach the solution is obtained with a speedup of about three orders of magnitude. Furthermore, the prediction process also supports parallel inference of different cases simultaneously, potentially yielding additional speed improvements. In terms of scalability, the FNO method allows training the algorithm using relatively small grids and inference on larger ones, which is not available in the SSFM approach.

Moreover, FNOs have shown widespread success in application to many other areas of physics and engineering48,49,50,51. We validate our approach using a high-quality microcavity sample52, to verify the method using real experimental results as input to train the FNO model, demonstrating, to the best of our knowledge, the first direct application of Neural Operators to coupled exciton-polariton condensate systems with experimental data. This work not only addresses the computational challenges of large-scale polariton simulations but also lays the groundwork for scalable workflows in the design of reconfigurable, all-optical devices.

Results

Steady-state condensates

In Fig. 2, we present the predictions of the FNO model for 4 representative test cases and their corresponding ground truths obtained from numerical simulations of the driven-dissipative polariton equations (see Methods). Note that we have carefully chosen four distinct pump profiles (see Fig. 2a–d) to visualize the performance of the model with varying inputs. As we see in Fig. 2e–h for predictions and in Fig. 2i–l for numerical ground truth, the model is highly accurate (see Fig. 2m–p) in predicting the steady-state solution ∣Ψ(t → ∞)∣ to the polariton GPE (see Methods). The FNO predictions demonstrate excellent agreement with numerical ground truth, capturing key features of the condensate density, including interference patterns and fringe parity. Notably, the model accurately predicts the direction of ballistic flow and scattering on below-threshold barriers, aligning with similar experimental results observed in inorganic semiconductor materials, where clear interference patterns have been reported23,26. We see that the predictions and the simulation ground truths are almost the same for different pump configurations, including the parity of fringes among spots. The parity of these fringes is responsive to the distance between spots23, which also indicates that our model is capable of capturing these details, such as the type of interaction between condensates.

a–d From left to right, the different pump configurations are P = 0.85, 0.9, 1.2, 1.4 Pth. e–h Corresponding condensate solutions ∣Ψp∣ with pump profiles, each featuring a distinct spatial profile and intensity from the prediction datasets. i–l Corresponding numerical steady-state solutions ∣Ψg∣ from the ground truth. m–p Corresponding absolute errors between prediction and ground truth \(\left\vert \right.| {\Psi }_{p}| -| {\Psi }_{g}| \left\vert \right.\). The white bar on all panels is 10 μm. The corresponding percentage errors of the number of condensate particles, are 1.12%, 4.07%, 0.04%, 0.24%. Pth is the threshold of the power density per single Gaussian spot.

The error panels in Fig. 2m–p reveal that the highest discrepancies occur near pump locations. These deviations arise from multiple factors: (i) the inherent nonlinearity of the system in these regions and the information loss caused by fast Fourier transform cut-off modes in the FNO architecture and (ii) the FNO approximates the first-order solution in the nonlinear operator while the numerical ground truth uses the higher-order one (see Supplementary Note 1 for details), introducing systematic approximation differences. However, errors outside the pump regions are minor, primarily attributable to nonlinear interactions between condensates. Empirically, the lower errors correspond to pump configurations where the distance between the pumps is smaller, leading to better interference predictions. Higher errors correspond to pump configurations where at least one pump is far from the other two, leading to worse interference pattern predictions. This is evident in the results where the pumps are very far apart (see Supplementary Fig. S4), compared to Fig. 2 where pumps are closer together. It is worth mentioning that due to extra interaction, despite for pump configuration with power density being below the threshold for each Gaussian spot denoted as Pth (see Methods for details), as shown in Fig. 2a, b, the whole system is still above the threshold. Also, it is worthy noting that the time to predict numerical solutions for 1122 cases (see Methods) using the CUDA-based numerical method took 3.35 × 104 s, while the FNO model took 8.78 s.

S-curve of condensate particles

As the system reaches the condensate threshold, the occupation of state will increase non-linearly then, followed by a linear increase as the excitation densities keep increasing19, which is known as the S-curve of the condensate system. Here, we demonstrate that the robustness of the FNO model is that it works not only for the linear region when the pumping density is high but also for the weakly pumped region. In Fig. 3a, we plot the logarithmic scale of condensate particle numbers as a function of pump density for the ground truth, while Fig. 3b presents the FNO predictions. Both curves align closely, capturing the transition from weak to strong excitation regimes. The absolute relative errors of number of condensate particles from prediction and numerical solutions with respect to the numerical ones are shown in Fig. 3c. Most errors are less than 10%, which shows great robustness and consistency for the FNO model. Large errors below condensation threshold are expected because there are fewer training datasets with small numbers of particles and therefore show more errors in predictions; therefore, it shows more errors for the predictions. We can see that in Fig. 3a at P = 0.9 Pth there are more test cases with much lower particle numbers.

The logarithmic scale of number of particles for a ground truths denoted as \(\log ({N}_{g})\), b predictions denoted as \(\log ({N}_{p})\), and c the relative error of the condensate particles in the prediction Np with respect to the ground truth Ng as a function of pumping density in the unit of Pth, where Pth is the threshold power of a single Gaussian spot.

Experimental realization

Figure 4 demonstrates the emission profile predictions obtained using experimental data as a training data set compared to the emission pattern obtained directly from the experiment. To obtain the desired spatial geometry of the pump profile, we calculate a series of spatial phase maps (kinoforms)53. A feature of this method is the creation of additional weak spots aligned with the interaction axis of the main spots. They have a much lower intensity than the desired pump spots and thus do not cause the formation of unwanted condensates, and their interactions with the investigated condensates are negligible. All pump spots of the inputs shown in Fig. 4a–d are set to be equal at P = 3.6Pth. The number of fringes predicted from the FNO model, as shown in Fig. 4e–h, is 3, 5, 6 and 8. Even and odd parity indicates the antiferromagnetic and ferromagnetic order in the polariton dyad, respectively. The FNO model reproduces the spatial profile of emissions with high accuracy regardless of the type of interaction between condensates, which is confirmed by Fig. 4i–l presenting experimental emission profiles. The effectiveness of the method was confirmed by an accurate reconstruction of the emission pattern with the correct number of interference fringes and propagation trajectories of polaritons compared to the ground truth obtained from the experiment. Moreover, the comparison of Fig. 4e–h and Fig. 4i–l shows that even subtle details of the patterns such as local intensity minima and maxima of the intensity profiles have been reproduced correctly. The method of post-processing of the experimental data is detailed in Supplementary Note 4. The details of the experimental datasets and hyperparameters can be found in Methods and Supplementary Table S1, respectively. More prediction results with different pump profiles can be found in Supplementary Note 6.

a–d From left to right, the different pump configurations. e–h Corresponding predictions from the pump profiles. i–l Corresponding post-processed photoluminescence from the experiment. The number of fringes on (e–h) is 3, 5, 6, 8, respectively, which is the same as those on (i–l). The white bar on all panels is 10 μm. The pump density for the whole experiment is 3.6 times the threshold value.

Discussion

Various general ML methods have been proposed to incorporate the underlying physics-based losses and information into the model to aid the learning task, such as in refs. 54,55,56,57. In this work, we have taken a purely data-driven approach to training; however, we believe that incorporating additional physics-informed loss terms will improve the accuracy, though this may come at the cost of slower convergence during training55. This is especially appealing, given that we have a strong theoretical understanding of the underlying system. In contrast to the theoretical steady-state datasets, the time-integrated PL data can also achieve good agreement with experimental features. A similar FNO-based real-world data-driven treatment has been adopted for weather forecasts58. In contrast to theoretical datasets, preprocessing of the experimental datasets is critical, as the input parameters from the experimental devices usually come with different orders of magnitude of values. It is important to note that the prediction from the experimental pump profile deviates slightly from the uniform values of the ground truth. Since only the relative intensity of the PL matters, it is not an issue from a physics perspective. Moreover, with the help of a streak camera, PL can be captured at the picosecond level, making it possible to make predictions of a time-resolved condensate formation on the basis of purely experimental data.

Beyond computational acceleration, the FNO method also provides capabilities for analyzing polariton systems. The accurate prediction of fringe parity enables the rapid determination of coupling types, such as ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic, between condensates23, as demonstrated in Figs. 2 and 4. The method’s ability to identify local intensity minima and maxima in the condensate density facilitates optimization of pump configurations for desired quantum states. These capabilities, combined with the computation speedup, enable applications such as real-time device design optimization, where iterative exploration of pump configurations for specific XY Hamiltonian states11 can now be performed interactively along with comprehensive parameter space exploration. While the interference patterns contain information about the underlying interaction parameters29, extracting these parameters would require further development of inverse modeling techniques. This opens possibilities for future ML-assisted inverse design problems, where desired condensate patterns could be used to determine optimal pump configurations.

In summary, we explored the potential of the FNO in the context of polariton condensates. Our findings demonstrate a notable alignment with the simulation data, with an approximate three orders of magnitude speed up in solution generation compared to CUDA-based GPU solvers. This research not only paves the way for the conceptualization and development of advanced large-scale all-optical devices from both theoretical and experimental perspectives but also draws parallels with the principles of EDA traditionally used in chip design. This approach represents a significant step toward the development of scalable workflows for designing reconfigurable optical devices.

Methods

Polariton Gross–Pitaevskii equation

The dynamics of polariton condensates are governed by the driven-dissipative polariton GPE coupled with the rate equation of the exciton reservoir \({{\mathcal{N}}}\)29:

where m is the polariton effective mass, α and G stand for, respectively, polariton-polariton and polariton-reservoir interaction, R denotes the scattering rate from the reservoir to the condensates, η refers to the ratio of the dark excitons, and γ (Γ) is the decay rate of the polariton (reservoir). The detuning between the exciton and the photon mode can greatly alter the interaction terms with the relationship α = g∣χ∣4 and G = 2g∣χ∣2, and g = g0/N where g0 is the exciton-exciton interaction, NQW is the number of QWs, and ∣χ∣2, representing the percentage of exciton of which the polariton consists, is the Hopfield coefficient59 of the excitonic branch. The FNO is trained to predict the steady-state solutions ∣Ψ(t → ∞)∣ obtained from numerically solving (1) and (2) using the SSFM, which constitute our ground truth data throughout this work.

In this work, the continuous-wave (CW) pump, denoted by P(r), is used to replenish the reservoir, which is depleting due to the dissipative character of the polaritonic system. The nonlinear term ∣ψ∣2 appearing in both the pump-to-reservoir transition (see (2)) and the superfluid in the condensates (see (1)), produce the rich nonlinear characteristic induced from the pump to the condensate.

In the case of CW excitation under a weak pumping regime, the approximate value of ∣ψ∣2 tends towards zero. In this situation, the rate of reservoir with respect to time maintains a stationary state, or in mathematical terms, \(\partial {{\mathcal{N}}}/\partial t=0\). The determination of threshold power, denoted at Pth, is possible through an analysis of the right-hand side (r.h.s.) of (1) where \(R{{\mathcal{N}}}=\gamma\) serves as a representative of the equilibrium state between gain and loss. Therefore, the threshold power Pth = γΓ/R is obtained. This suggests that when the population of polaritons exceeds the condensation threshold Pth, a detectable density value manifests itself. The real potential of (1) denoted V in the stationary state of the system, therefore, is

The real potential is composed of two main components: one originating from the pumping region (first term on the r.h.s of (3)) and the other stemming from the interactions among the polaritons outside this region (second term on the r.h.s of (3)). When the pump power is below the threshold, the direct contribution of the potential goes directly into the pumping profile. This relationship is represented as V(r) = (1 + η)(G/Γ)P(r). The spatial profile is chosen for the demonstration of NG Gaussian spots. That is

where Pi stands for strength of each spot and the normalized Gaussian function Gi(r), with full width at half maximum (FWHM) denoted σ, is defined as

Note that ri represents a different location of spots.

The FNO prediction shown in Results takes P(r) and ∣Ψ(t = 0)∣ as two inputs. Here, ∣Ψ(t = 0)∣ is fixed as a zero matrix with the same dimension as the matrix of P(r). The number of condensate particles in Fig. 3 are calculated from

Fourier neural operators

The numerical solution to (1) and (2) is derived using the SSFM, detailed in Supplementary Note 1. A natural ML analog to this classical method is the FNO architecture42. More generally, Neural Operators60 are a class of models which learn mappings between two infinite-dimensional spaces from a finite set of input-output pairs. Many variants of the Neural Operator architecture have been applied to approximate solutions to Partial Differential Equations, such as in refs. 48,49,50,51. The Neural Operator architecture consists of a lifting operation \({{\mathcal{P}}}\), followed by iterative updates using a Kernel Integral Operator \({{\mathcal{K}}}\), and a final projection operator \({{\mathcal{Q}}}\), as defined in (7).

Here, σ corresponds to a non-linearity and W and b correspond to the weights and biases of the Kernel Integral Layer, respectively. \({{\mathcal{P}}}\) and \({{\mathcal{Q}}}\) are point-wise fully local projection and lifting operators. The choice of the Kernel Integral Operator \({{\mathcal{K}}}\) delineates the class of the Neural Operator. Specifically, the FNO (see Fig. 5) uses the Kernel Integral Operator defined by:

Here \({{\mathcal{F}}}\) and \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}^{-1}\) correspond to the Fourier and Inverse Fourier Transforms and \({{{\mathcal{R}}}}_{\phi }\) corresponds to a learned, complex-valued multiplier applied mode-wise to the top k modes pertaining to each layer, where k is a hyperparameter in the model. See Supplementary Note 2 for further architectural details.

The process begins with the input a(x) which undergoes a lifting operation, denoted as \({{\mathcal{P}}}\). This is followed by 4 consecutive Fourier layers. Subsequently, a projector \({{\mathcal{Q}}}\) transforms the data to the desired target dimension, resulting in the output u(x). The inset provides a detailed view of the structure of a Fourier layer. Data initially flow to the layer as ν(x) and are bifurcated into two branches: one undergoes a linear transformation W, and the other first experiences a Fourier transformation, from which the 128 lowest Fourier modes are kept, and the other higher modes are filtered out by undergoing a transformation R, and ends with an inverse Fourier transformation with these left modes. The two data streams then converge, followed by the application of an activation function σ.

Here, the FNO implementation with k = 128 modes, along with 4 FNO layers and 64 hidden channels, was determined through hyperparameter optimization to minimize the trade-off between model expressiveness and generalization performance for the polaritonic system. Note that while the numerical ground truth is computed using the second-order Strang splitting, the FNO architecture approximates the simpler first-order solution (see Supplementary Note 1 for details). This difference also contributes to the systematic errors observed in Fig. 2, particularly in regions of strong nonlinearity, such as near pump locations.

The natural choice of the FNO architecture for approximating the solution to (1) and (2) is due to the inductive bias that arises from the SSFM-FNO correspondence stated below.

Theorem 1

(SSFM-FNO Correspondence) Suppose that σ ∈ (TW) is a Tauber-Wiener function, X is a Banach Space, K ⊂ X is a compact set, V is a compact set in C(K), Ψt is a nonlinear continuous operator representing the solution of the first-order Split-step Fourier Method at time t. Then for any any ϵ > 0, there are a positive integer n, m points x1, . . . , xm ∈ K, and real constants ci, θi, ξij (for i = 1, . . . , n and j = 1, . . . , m) such that:

holds for allu ∈ V.

Proof. See SI.

Sample and experimental techniques

The sample used in the experiment is the 2λ high-quality semiconductor optical microcavity with quantum wells52. The structure consists of a GaAs-based microcavity placed between two DBRs made of pairs of GaAs and AlAs0.98P0.02 layers. In the microcavity region, the three pairs of 6 nm In0.08Ga0.92As QWs placed in anti-nodes of the electric field. Two additional QWs positioned at the extreme nodes of the cavity wells serve for carrier collection. The sample was held in a cold finger, closed-cycle cryostat operating at a temperature of T ≈ 7K.

The optical nonresonant excitation is provided by a continuous-wave Ti:Sapphire laser modulated by an acousto-optic modulator to prevent heating effects. In order to obtain the pump profile with multiple-spot excitation, a reflecting liquid-crystal spatial light modulator (SLM) is used. The screen of the SLM displays calculated phase holograms in the Fourier plane modulating the Gaussian beam of the excitation laser beam. The phase holograms are accomplished by imprinting an analytically generated phase pattern on the SLM screen. The procedure results in generating the intended configuration of the laser spots at the focal plane of the microscope objective lens.

Numerical simulation

To better emulate the experiment, σ ≈ 0.85 μm, the FWHM of each Gaussian spot equalling to 2 μm, is chosen. The simulation is based on InGaAs QWs52 with slightly negatively detuned cavities. The parameters are the following: m = 0.28 meV ps2 μm−2, ∣χ∣2 = 0.4, NQW = 6, g0 = 0.01 meV μm2, ℏR = 10g, η = 2, and γ−1 = Γ−1 = 5.5 ps. All the numerical simulations were generated using the SSFM on a 256 × 256 grid with 0.5 μm/pixel resolution, corresponding to 128 μm × 128 μm physical size. The numerical ground truth was obtained by solving the polariton GPE with Dirichlet boundary conditions and adaptive time stepping with Δt = 0.01 ps until steady state.

Numerical dataset

The datasets are constructed based on varying pump profiles P(r), as described in (4). This profile is characterized by four Gaussian spots taking NG = 4 with the spatial profile of each spot obtained by Gi(r). Among these four spots, three of them are equally powered and have their power set at Pi = 0.85, 0.90, 0.95, 1.0, 1.05, 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4, 1.5, 1.6 Pth, while the fourth spot is powered far below the threshold at Pi = 0.5 Pth. Thus, in terms of the power value, there are 11 different configurations. Note that Pth refers to the threshold power for a single spot, which means that the entire system can still trigger the condensate with three spots below the threshold with an additional contribution from the interaction among them22. The reason why the power varies is that we want the datasets to also cover the S-curve (see Fig. 3a), the region where the power-intensity relationship19 is taken into account. These profiles are stochastically determined within a square region that measures 64 μm × 64 μm out of the entire configuration with 128 μm × 128 μm. The region where Gaussian spots stay is smaller than the full grid, to make sure that they are still far from the region where the boundary condition is applied. Care has also been taken to ensure that the Gaussian spots do not overlap under the same power density, so that without losing generality the minimal distance between two spots is set at 4× FWHM of the Gaussian spot. Additionally, every pump profile is unique, and among the spots with power exceeding the threshold, each one is distinct from the others, thereby eliminating any potential redundancy. Given 0.5 μm resolution per pixel per dimension, the total datasets for the pump configuration is with size 256 × 256 × 11,220 where 256 represents each square map size per dimension and 11,220 is the number of different pump configurations (of which 1122 configurations are used for testing, 1122 configurations are used for validation, and 8976 for training respectively). The datasets for the density map are of size 256 × 256 × 2 × 11,220 where 2 refers to the density at the initial and final time. It is worth mentioning that the systems of all the datasets are chosen with a system only at stationary state with single energy mode, which means that the results with multiple energy modes are excluded. In multimode cases, the wavefunction density changes at different times, which can be found in experiments23,61.

Experimental dataset

The experimental pump profiles are normalized to unity. PL data are enhanced using logarithmic function and contrast-limited adaptive histogram equalization62, which is detailed in SI. The datasets are of size 256 × 256 × 1120 of which 1104 cases are used for training and 16 cases for testing. The initial state is a zero-valued array of size 256 × 256 × 1120. Data argumentation is applied for the training datasets by rotating the original 138 training datasets at 45° step around the image center, namely, 0°, 45°, 90°, … , 315°, at the center of the image, resulting in training datasets of size 1104.

Implementation of FNO model

The FNO model was implemented using the Neural Operators in PyTorch and trained on an Intel Core i9-13900KF CPU with 64 GB of RAM and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU (24 GB of global memory). The architecture employs a 2D FNO with 128 × 128 Fourier modes retained in each spatial dimension, 4 Fourier layers, and 64 hidden channels. The input consists of 2 channels (pump profile and initial zero state), which are lifted to a 64-dimensional feature space before passing through the Fourier layers. Domain padding of 12.5% with symmetric mode was applied to handle boundary effects. Training used the Adam optimizer (learning rate: 3 × 10−3, weight decay: 5 × 10−5) with cosine annealing scheduling. The oscillations observed in the training curves (see Supplementary Figs. S2, S3) are a direct consequence of this cosine annealing schedule where the maximum number of epochs in a cycle is set to 30, which we found to perform well with the polaritonic condensates datasets and effectively prevent overfitting. The details of hyperparameter (see Supplementary Table S1), and Training or validation losses versus epochs using numerical and experimental datasets of the FNO model can be found, respectively, in Supplementary Figs. S2, S3.

Data availability

All data supporting this study are openly available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15845086.

Code availability

All code supporting this study are openly available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15845086.

References

Amo, A. et al. Exciton–polariton spin switches. Nat. Photonics 4, 361–366 (2010).

Giorgi, M. D. et al. Control and ultrafast dynamics of a two-fluid polariton switch. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 266407 (2012).

Gao, T. et al. Polariton condensate transistor switch. Phys. Rev. B 85, 235102 (2012).

Dreismann, A. et al. A sub-femtojoule electrical spin-switch based on optically trapped polariton condensates. Nat. Mater. 15, 1074–1078 (2016).

Ma, X. et al. Realization of all-optical vortex switching in exciton-polariton condensates. Nat. Commun. 11, 897 (2020).

Feng, J. et al. All-optical switching based on interacting exciton polaritons in self-assembled perovskite microwires. Sci. Adv. 7, eabj6627 (2021).

Chen, F. et al. Optically controlled femtosecond polariton switch at room temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 057402 (2022).

Ballarini, D. et al. All-optical polariton transistor. Nat. Commun. 4, 1778 (2013).

Zasedatelev, A. V. et al. A room-temperature organic polariton transistor. Nat. Photonics 13, 378–383 (2019).

Zasedatelev, A. V. et al. Single-photon nonlinearity at room temperature. Nature 597, 493–497 (2021).

Berloff, N. G. et al. Realizing the classical XY hamiltonian in polariton simulators. Nat. Mater. 16, 1120–1126 (2017).

Lagoudakis, P. G. & Berloff, N. G. A polariton graph simulator. N. J. Phys. 19, 125008 (2017).

Opala, A., Ghosh, S., Liew, T. C. & Matuszewski, M. Neuromorphic computing in ginzburg-landau polariton-lattice systems. Phys. Rev. Appl. 11, 064029 (2019).

Ballarini, D. et al. Polaritonic neuromorphic computing outperforms linear classifiers. Nano Lett. 20, 3506–3512 (2020).

Mirek, R. et al. Neuromorphic binarized polariton networks. Nano Lett. 21, 3715–3720 (2021).

Ghosh, S., Nakajima, K., Krisnanda, T., Fujii, K. & Liew, T. C. H. Quantum neuromorphic computing with reservoir computing networks. Adv. Quantum Technol. 4, 2100053 (2021).

Opala, A. et al. Training a neural network with exciton-polariton optical nonlinearity. Phys. Rev. Appl. 18, 024028 (2022).

Opala, A. & Matuszewski, M. Harnessing exciton-polaritons for digital computing, neuromorphic computing, and optimization. Opt. Mater. Express 13, 2674–2689 (2023).

Kasprzak, J. et al. Bose–Einstein condensation of exciton polaritons. Nature 443, 409–414 (2006).

Wang, Y., Lagoudakis, P. G. & Sigurdsson, H. Enhanced coupling between ballistic exciton-polariton condensates through tailored pumping. Phys. Rev. B 106, 245304 (2022).

Weisbuch, C., Nishioka, M., Ishikawa, A. & Arakawa, Y. Observation of the coupled exciton-photon mode splitting in a semiconductor quantum microcavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 3314–3317 (1992).

Tosi, G. et al. Sculpting oscillators with light within a nonlinear quantum fluid. Nat. Phys. 8, 190–194 (2012).

Töpfer, J. D., Sigurdsson, H., Pickup, L. & Lagoudakis, P. G. Time-delay polaritonics. Commun. Phys. 3, 2 (2020).

Pickup, L., Sigurdsson, H., Ruostekoski, J. & Lagoudakis, P. G. Synthetic band-structure engineering in polariton crystals with non-Hermitian topological phases. Nat. Commun. 11, 4431 (2020).

Dovzhenko, D., Aristov, D., Pickup, L., Sigurosson, H. & Lagoudakis, P. Next-nearest-neighbor coupling with spinor polariton condensates. Phys. Rev. B 108, L161301 (2023).

Töpfer, J. D. et al. Engineering spatial coherence in lattices of polariton condensates. Optica 8, 106 (2021).

Wouters, M., Carusotto, I. & Ciuti, C. Spatial and spectral shape of inhomogeneous nonequilibrium exciton-polariton condensates. Phys. Rev. B 77, 115340 (2008).

Wertz, E. et al. Propagation and amplification dynamics of 1d polariton condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 216404 (2012).

Wouters, M. & Carusotto, I. Excitations in a nonequilibrium Bose-Einstein condensate of exciton polaritons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 140402 (2007).

Niemietz, D. et al. Experimental realization of a polariton beam amplifier. Phys. Rev. B 93, 235301 (2016).

Schmutzler, J. et al. All-optical flow control of a polariton condensate using nonresonant excitation. Phys. Rev. B 91, 195308 (2015).

Cristofolini, P., Hatzopoulos, Z., Savvidis, P. G. & Baumberg, J. J. Generation of quantized polaritons below the condensation threshold. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 067401 (2018).

Wang, Y., Sigurdsson, H., Töpfer, J. D. & Lagoudakis, P. G. Reservoir optics with exciton-polariton condensates. Phys. Rev. B 104, 235306 (2021).

Aristov, D., Baryshev, S., Töpfer, J. D., Sigurosson, H. & Lagoudakis, P. G. Directional planar antennae in polariton condensates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 123, 121101 (2023).

Kavokin, A. et al. Polariton condensates for classical and quantum computing. Nat. Rev. Phys. 4, 435–451 (2022).

Kalinin, K. P., Alyatkin, S., Lagoudakis, P. G., Askitopoulos, A. & Berloff, N. G. Simulating the spectral gap with polariton graphs. Phys. Rev. B 102, 180303 (2020).

Lončar, V. et al. CUDA programs for solving the time-dependent dipolar gross–pitaevskii equation in an anisotropic trap. Comput. Phys. Commun. 200, 406–410 (2016).

Schloss, J. & O’Riordan, L. GPUE: Graphics processing unit gross–pitaevskii equation solver. J. Open Source Softw. 3, 1037 (2018).

Wilson, J. P. Generalized finite-difference time-domain method with absorbing boundary conditions for solving the nonlinear schrödinger equation on a GPU. Comput. Phys. Commun. 235, 279–292 (2019).

Smith, B. D., Cooke, L. W. & LeBlanc, L. J. GPU-accelerated solutions of the nonlinear schrödinger equation for simulating 2d spinor BECs. Comput. Phys. Commun. 275, 108314 (2022).

Kivioja, M., Mönkölä, S. & Rossi, T. GPU-accelerated time integration of gross-pitaevskii equation with discrete exterior calculus. Comput. Phys. Commun. 278, 108427 (2022).

Li, Z. et al. Fourier neural operator for parametric partial differential equations. In International Conference on Learning Representations https://openreview.net/forum?id=c8P9NQVtmnO (2021).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2015, (eds, Navab, N., Hornegger, J., Wells, W. M. & Frangi, A. F.) 234–241 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2015).

Lu, L., Jin, P., Pang, G., Zhang, Z. & Karniadakis, G. E. Learning nonlinear operators via DeepONet based on the universal approximation theorem of operators. Nat. Mach. Intell. 3, 218–229 (2021).

Li, Z. et al. Neural operator: Graph kernel network for partial differential equations. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS, 2020).

Li, Z. et al. Multipole graph neural operator for parametric partial differential equations. In ICLR 2020 Workshop on Integration of Deep Neural Models and Differential Equations (ICLR, 2020).

Li, Z. et al. Physics-informed neural operator for learning partial differential equations. ACM J. Data Sci. https://doi.org/10.1145/3648506 (2024).

Gopakumar, V. et al. Fourier neural operator for plasma modelling. In Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Workshop on AI4Science (NIPS, 2021).

Wen, G., Li, Z., Azizzadenesheli, K., Anandkumar, A. & Benson, S. M. U-fno-an enhanced fourier neural operator-based deep-learning model for multiphase flow. Adv. Water Resour. 163, 104180 (2022).

Zhang, T., Trad, D. & Innanen, K. Learning to solve the elastic wave equation with Fourier neural operators. Geophysics 88, T101–T119 (2023).

Li, Z., Peng, W., Yuan, Z. & Wang, J. Fourier neural operator approach to large eddy simulation of three-dimensional turbulence. Theor. Appl. Mech. Lett. 12, 100389 (2022).

Cilibrizzi, P. et al. Polariton condensation in a strain-compensated planar microcavity with InGaAs quantum wells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 191118 (2014).

Lesem, L. B., Hirsch, P. M. & Jordan, J. A. The kinoform: A new wavefront reconstruction device. IBM J. Res. Dev. 13, 150–155 (1969).

Raissi, M., Perdikaris, P. & Karniadakis, G. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 378, 686–707 (2019).

Karniadakis, G. E. et al. Physics-informed machine learning. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3, 422–440 (2021).

Lu, L., Meng, X., Mao, Z. & Karniadakis, G. E. DeepXDE: A deep learning library for solving differential equations. SIAM Rev. 63, 208–228 (2021).

Cuomo, S. et al. Scientific machine learning through physics–informed neural networks: Where we are and what’s next. J. Sci. Comput. 92, 88 (2022).

Pathak, J. et al. FourCastNet: a global data-driven high-resolution weather model using adaptive Fourier neural operators. In Proc. Platform for Advanced Scientific Computing Conference (PASC) (ACM, 2023).

Hopfield, J. J. Theory of the contribution of excitons to the complex dielectric constant of crystals. Phys. Rev. 112, 1555–1567 (1958).

Kovachki, N. et al. Neural operator: Learning maps between function spaces with applications to pdes. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 24, 1–97 (2023).

Krizhanovskii, D. N. et al. Coexisting nonequilibrium condensates with long-range spatial coherence in semiconductor microcavities. Phys. Rev. B 80, 045317 (2009).

Zuiderveld, K. Contrast limited adaptive histogram equalization. In Graphics Gems 474–485 (Elsevier Inc., 1994).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the European Union Horizon 2020 program, through a Future and Emerging Technologies (FET) Open research and innovation action under Grant Agreement No. 964770 (TopoLight).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W. and S.T.S. conceptualized the idea. S.T.S. and Y.W. contributed to the code. Y.W. performed the theoretical modelling and numerical simulations. K.S. performed the experiments. S.T.S., Y.W., K.G., and A.I.A. contributed to the machine learning analysis. Y.W., S.T.S, and K.S. wrote the manuscript. Y.W. and P.G.L. led the research. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results and revision to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks Paolo Comaron and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Sathujoda, S.T., Sawicki, K. et al. A Fourier neural operator approach for modelling exciton-polariton condensate systems. Commun Phys 8, 505 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02409-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02409-2