Abstract

Due to their particle-like properties, three-dimensional (3D) spin textures have garnered significant interest, particularly for their potential applications in next-generation information storage devices. However, efficiently identifying these textures remains a major challenge, especially if they are of antiferromagnetic nature. Here, we demonstrate that instead of relying solely on the magnetic stray field, which vanishes in antiferromagnets, one can harvest the usually disregarded electronic signal. This gives rise to a electron holographic contribution probed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). We reveal the underlying physics, systematically quantify, and offer disentangling strategies for both conventional and previously neglected identified TEM images, extracted from various magnetic structures, including ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic skyrmion tubes, as well as hopfions. Our findings mark a milestone in advancing the exploration and possible application of 3D spin textures in next-generation spintronic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The miniaturisation of data storage units leads to an increasing impact of quantum effects and thermal effects, which hinders a further decreases in size. Therefore, the ongoing search for radically new storage techniques is vital to keep up with the industrial and academic needs of future devices. Particularly interesting for future spintronic devices are topologically protected spin textures, which are spatially localised quasiparticles. Prominent examples are (anti-) skyrmions, chiral bobbers, and hopfions. The skyrmion is a topological spin texture, with a whirlpool-like magnetic profile, confined in two dimensions1,2,3,4,5. Skyrmions can acquire a third dimension once stacked upon each other to form skyrmion-tubes6,7,8. Compared to skyrmions, bobbers are relatively new spin textures9,10,11, which consist of skyrmion-tubes, with decreasing size along one direction, ultimately terminating in a magnetic singularity, called a Bloch-point. Recently, another type of three-dimensional (3D) topological spin textures, the hopfions12,13,14, became heavily explored due to their intriguing properties. The hopfion has a donut-like shape and can be seen as a twisted skyrmion-tube, where the two ends are connected to form a closed loop. It was predicted to be hosted in frustrated magnets15, and has been observed recently16,17. We note however, that the identification and visualization of 3D spin textures, especially for hopfions, remain challenging.

Powerful experimental tools utilized to explore such spin textures are X-ray techniques (X-PEEM, MTXM, etc.)18,19 or transmission electron microscopy (Lorentz imaging (LTEM)20,21, electron holography22,23,24,25,26, etc.) due to their significant spatial resolution. However, they only provide access to a portion of the projected spin texture. In principle, a reconstruction of the 3D spin texture is possible by obtaining images from different incident beam angles with electron-holography27, LTEM28, and MTXM29. Naturally, the more information is obtained from each individual image, the more meaningful the information about the 3D structure becomes.

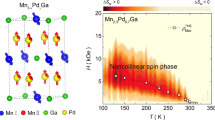

In the current work, we demonstrate that electron holography images contain additional and nontrivial information, which, to the best of our knowledge, has so far not been considered and is paramount for the characterization of complex spin textures (see Fig. 1). Up to now, the data is analyzed in terms of the stray magnetization emanating from the explored spin textures. Here, we show, however, the emergence of a series of induced charges carried by the spin textures, which deflect the impinging electron beam and contribute to the phase shift detected in transmission electron microscopy (TEM). As this phase shift is caused by charges, this component is found in the electronic part of the phase image; it is usually assumed that this mainly consists of the mean inner potential. To avoid confusion, we refer to the discovered contributions of the phase image as a non-collinearity-induced (NCI) electronic phase image. The identified induced charges are shaped by isotropic, chiral non-collinear, and spin-orbit contributions while remaining finite in antiferromagnetic (AFM) non-collinear materials. We discuss these terms, their amplitude, and impact on TEM images, which offer promising opportunities in exploring 3D complex magnetic objects.

a Schematic and simplified setup for capturing phase images within a transmission electron microscope. b Tilt series of phase-images and decomposition of a single phase-image into magnetic and electronic components as exemplified for a hopfion. The illustrated phase images are the basic ingredients for a 3D reconstruction of the spin texture, ultimately enabling tomography, which is not the focus of our study. The electronic component consists of three contributions that depend on the rotation of the magnetic moment and the presence of spin-orbit coupling. For the simulation, we used a common value of 300 keV for the acceleration voltage.

Results

Theory of magnetic induced charges

Here, we introduce the mechanisms leading to the emergence of the magnetic induced charges. Utilizing multiple scattering theory expressed in a tight-binding formulation, we quantify how the charge carried by a given magnetic atom is modified by the misalignment of the surrounding magnetic moments, as it is the case for a non-collinear spin texture.

We present one of the main results of this paper, that is the formulation of the non-collinearity induced charge as a function of the angle between neighboring magnetic moments, systematically expressed in terms of dot products of magnetic moments (isotropic), cross products (chiral and linear with spin-orbit coupling (SOC) as well as mixed products involving the magnetic moments and the anisotropy field induced by spin-orbit coupling.

Assuming the following Hamiltonian, describing without loss of generality, that each site hosts a single orbital as expressed in the Anderson model30 amended with hopping31,32 between nearest neighboring atomic sites:

In the first term of Eq. (1), ϵd corresponds to the orbital’s energy (in the context of our current work d-orbitals carry the magnetic moments) before the energy splitting is induced by magnetism. The splitting is accounted for by the term Umj = Umej ⋅ σ, where Um represents the exchange splitting, U being the intra-atomic exchange interaction, m the length of the magnetic moment, ej its direction σ the vector of Pauli matrices and \({c}_{j}\,({c}_{j}^{{{\dagger}} })\) stands for the annihilation (creation) operator for site j. While the magnetic moments can be misaligned, their magnitude, for simplicity, is assumed to be the same for all sites. Γ is shaped by the coupling of the orbitals to the bath of electrons, which triggers a broadening of the associated electronic states.

The second term of Eq. (1) accounts for SOC and leads to the Rashba Hamiltonian31,32, which comprises both a non-magnetic and chiral Rashba components. The connection to the Rashba model is detailed in the methods section. The Rashba-angle φR fine-tunes the balance between the conventional spin-independent and chiral Rashba hopping. The anisotropy field nij varies by site and emerges from SOC, leading to a broken inversion symmetry since nij = − nji. It defines a chiral vector, similar to the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction (DMI)33,34,35.

Based on a multiple-scattering approach, utilizing the hopping in a perturbative framework, described in the methods section, we identify a series of charges induced at site j by the misalignment of magnetic moments located at sites i. We focus on processes that are second-order in terms of the hopping t, which are tabulated in Fig. 2.

The arrows indicate the type of magnetic states that can be distinguished by the different terms. For example, the isotropic (a) induced charge differentiates the ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic configurations. The chiral (b) term monitors the change of chirality, while the anisotropic (c) one senses the rotation of both moments with respect to the SOC anisotropy field. Here ei and ej are the unit vectors of two neighbouring magnetic moments, nji is the anisotropy field induced by SOC and φR stands for the Rashba-angle.

The first contribution in Fig. 2a is termed isotropic due to its cosine dependence on the angle between the two magnetic moments; the cosine function cannot differentiate the sign of the angle. It hinges on the difference between spin-independent and chiral Rashba hopping. While being finite without SOC, this term gets reduced with the possibility of cancellation or even sign reversal once incorporating the Rashba coupling. Thus, it emerges as a hybrid of a 0th-order and 2nd-order contribution in SOC, necessitating two electron scattering events between two magnetic moments. The isotropic induced charge is finite for both cases, ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic alignment of the moments.

The chiral contribution (Fig. 2b) depends on the cross-product of the two magnetic moments and is 1st-order in SOC. To be finite, it needs broken inversion symmetry. This allows the chiral contribution to be sensitive to the chiral nature of the underlying spin textures.

The third contribution is anisotropic (Fig. 2c) and 2nd-order in SOC while having a form similar to that of an anisotropy energy, but generalized to a non-local scattering, i.e., involving two different magnetic moments.

For large spin textures, and taking the micromagnetic limit, one can show that the local contribution prevails (Supplementary Note 2). Furthermore, in Supplementary Fig. 1 we address the accuracy of the perturbative approach by making a comparison to the exact result for a dimer.

Based on our findings, we can quantify the different contributions for arbitrary complex spin profiles. In the next subsection, we establish a link to experiments by addressing the impact of non-collinearity-induced charges to TEM and electron holography.

Scheme to quantify phase images and electron holography

In the preceding subsection, we observed that a spin texture leads to the redistribution of charge. This, as we show in the following subsections, can be used to distinguish a spin texture from the ferromagnetic or antiferromagnetic surrounding. In this section, we present a scheme that enables to evaluate the phase images induced by the induced charges and captured by electron holography within TEM. The latter offers an ideal playground for detecting such induced charges, owing to its good spatial resolution, sensitivity to electrostatic potential, and its existing use for the identification of 3D spin textures when probing the impact of stray magnetic field36. We note that our findings from the previous section are general and applicable to other methods based on TEM, such as LTEM or differential phase-contrast (DPC), which can access phase information.

This technique involves directing an electron wave onto the sample. As it traverses the material, the wave accumulates a phase shift, denoted as φ, due to scattering at the material’s electrostatic and magnetic vector potentials. When the electron wave hits the detector, only the amplitude is measured and the phase is lost. There are therefore various methods for converting the phase information into a measurable amplitude. We limit ourselves to electron holography.

There exist several techniques for electron holography, here, we address the common off-axis electron holography37. Thereby, two-dimensional phase image are obtained which correspond to both the electrostatic potential Φ and the magnetic vector potential A:

where we have assumed for simplicity that the electron wave propagates along the z-direction. e0 represents the absolute value of the electron charge. The prefactor CE for the electronic contribution depends on the acceleration voltage used in the TEM, which for the purpose of our study is an advantage over the magnetic component, as it allows the relative strength of the electronic component to be tuned.

As aforementioned, so far, the electronic contribution is considered to be transparent to the underlying magnetic textures when probed by electron holography, which is contradicted by our derivations from the preceding subsections. In Fig. 1b the schematic construction of phase images is shown. A spin texture creates a phase-images that depends on the angle of the incoming electron wave. For each angle, the phase-images consist of several contributions which are either magnetic or electronic. We focus on the electronic contributions, which arise from the contributions shown in Fig. 2. It is at this stage important to be able to compare the relative strength between the previously unidentified electronic contribution to the conventional magnetic one. The latter can be evaluated by an optimized forward model38 that has already demonstrated success39, and reproduced in the following.

Starting from equation (2) and assuming for simplicity that the electron waves travel along the z-direction, one can rewrite the magnetic contribution as

where Msat is a material-dependent saturation magnetization and μ0 the vacuum permeability. Such an equation can be readily solved numerically using e.g. the convolution theorem.

The non-collinearity induced electronic contribution demands the development of a new method, one that is consistent with the approach used for the magnetic part (see methods section for details). We start from Eq. (2) and insert the Poisson’s equation:

which incorporates screening effects via the Thomas-Fermi screening parameter ktf. We are now equipped to explore spin textures addressed in the next subsection.

Non-collinarity induced charges of 3D spin textures

We explore in this section the charge induced by diverse 3D spin textures. There is a plethora of interesting magnetic objects predicted theoretically and observed experimentally, therefore, we had to make a selection of cases to discuss. We start with the skyrmion-tubes, since they have been heavily investigated experimentally and are therefore the ideal candidates to test our predictions. We then continue our study by addressing hopfions. Additionally, the electronic non-collinearity induced phase images for magnetic bubbles are discussed in Supplementary Note 3 and displayed in Supplementary Fig. 2.

In Fig. 3, we plot the different non-collinearity induced charges for the Néel- and Bloch-type of skyrmion tubes. As an example, we assume the following electronic parameters: Um = 0.677 eV, ϵd = 0 eV, t = 0.07 eV, Γ = 0.15 eV, φR = π/12, and the Fermi energy ϵF is set to 0.48 eV. The isotropic contribution (b and f) forms a ring pattern that is identical for both types of skyrmions. This is due to the underlying mechanism giving rise to the isotropic induced charge, namely, the cosine angle between neighbouring sites is identical for the two skyrmions. At the core of the skyrmions, the patterns is significantly weaker, due to the underlying magnetic collinearity. At the skyrmion edges, where the non-collinearity is maximized, the induced charge reaches significant values. The chiral nature of the two magnetic objects being distinct, the chiral-induced charge patterns are strikingly different (c and g). This is due to the anisotropy field giving rise to the chiral vector defining the chiral induced charge, which is within the Rashba model identical to the one giving rise to the interface-DMI. The anisotropic patterns, similarly to the isotropic ones, are identical for both skyrmion-tubes (d-h).

(a–d) are associated to the Néel-type skyrmion-tube, while (e–h) shows the Bloch-type skyrmion-tube. The patterns of the induced charges (b-d) and (f-h) are rich and can dramatically change depending on the type of skyrmions. The skyrmion profile (a, e) is obtained from44 with c = w = 10 nm.

After analysing the case of skyrmion-tubes, we address the case of hopfions. While skyrmion-tubes are characterized in our analysis by an identical spin textures along the z-direction, hopfions are different and therefore require us to consider the whole 3D charge distribution as shown in Fig. 4. As an example, we consider two cuts along the planes shown in Fig. 4a.

a The spin-profile on the surface of a torus (hopfion with hopfindex 1) is shown. Two planes are depicted which correspond to the cuts shown in (b, c). (d–f) show the three contributions to the induced charge for cut shown in (b), while (g, h, i) correspond to cut (c). The hopfion profile is obtained from46 which is based on the ansatz presented in47. Thereby we use R = 12 nm, wR = 7.5 nm, h = 6 nm andwh = 3.25 nm.

Starting with the isotropic patterns (d) (associated to in-plane cut (b)) in Fig. 4, we notice an isotropic disk located at the center of the hopfion. The perpendicular cut (g) reveals that the disk extends into a tube with increased intensity at both ends. The chiral patterns possess a more complicated pattern. Two regions with different sign emerge in the in-plane cut, however, the perpendicular cut reveals that these regions change sign along the z-axis, resulting in 4 regions in total. The anisotropic profile hosts ring-like features in (f) associated to the in-plane cut (c), with weak intensity in the center due to the alignment with the background in this region. Within the out-of-plane cut (c), the anisotropic shapes consist of two elongated features, with a mirror symmetry in the middle, which can be easily related to the spin textures depicted in (c). Indeed, in the region where the magnetic moments point along (white arrows) or against (black arrows) the anisotropic contribution is zero.

After the analysis of the non-collinarity induced charges of various 3D spin textures, we address in the next subsection the associated phase images when probed with electron beams pertaining to TEM.

Phase images and electron holography of 3D spin textures

The phase-images are tightly connected to the underlying non-collinearity-induced charges. This can readily be noticed when analysing the phase-image associated to the electronic contribution of the hopfion, see Fig. 5a, which is characterized by red rings directly connected to the charge plotted in Fig. 4f. The latter panel showcases regions with different sign, which are suppressed in the phase-image by the strong anisotropic contribution. Similar conclusions can be drawn for the Néel-type skyrmion-tube when comparing the phase-image in Fig. 5b with the corresponding charge (Fig. 3g). For the acceleration voltage we use 300 keV.

As an example three different spin textures are used, (a, d) showcase phase-images for a hopfion, (b, e) for a Néel-type skyrmion-tube. The phase-images (c, f) are obtained for an antiferromagnetic Bloch-type skyrmion-tube. The left column (a–c) shows the electronic contribution coming from the non-collinearity induced charge to the phase-image from Eq. (5), while the middle column (d–f) shows the magnetic contribution to the phase-image, defined in Eq. (4). (g) pictures a comparison of the total non-collinearity induced electronic and magnetic contribution to the phase-image for a ferromagnetic Bloch-type skyrmion-tube with different skyrmion diameters and acceleration voltages used in the TEM. We note that these ratios depend on the material and are obtained using the following electronic parameter: Um = 0.677 eV, ϵd = 0 eV, t = 0.07 eV, Γ = 0.15 eV, φR = π/12, and the Fermi energy ϵF is set to 0.48 eV. The line-profiles for the electronic (h) and conventional magnetic (i) phases along the center of a ferromagnetic Néel-type skyrmion-tube (b, e) are shown for different incident beam angles.

Looking at the magnetic contributions to the phase-images in Fig. 5d–f, one sees that the Néel-type skyrmion-tube has a vanishing magnetic contribution for a electron beam perpendicular to the skyrmion. Experimentally, this was observed and therefore samples hosting such skyrmions are rotated to induce a non-vanishing magnetic signature39. Bloch-type skyrmion-tubes induce a magnetic signal in the phase-image without the need of rotation40. For an antiferromagnetic (AFM) Bloch-type Skyrmion-tube, however, atomic resolution is needed in order to pick up a finite magnetic signal (f) since the stray field cancels out. The presented electronic contribution to the phase-image does not suffer from such shortcoming and stay valid up to a sign change (c). In Supplementary Note 4 (Supplementary Fig. 3), we provide the spin texture of the AFM Bloch-skyrmion and additional accelerating voltage diagrams for AFM/FM Bloch- and Néel-skyrmions. This holds true for all non-collinear AFM spin textures. Comparing the impact of rotating the sample on the phase-images shown in Fig. 5h–i, one immediately notices striking differences. While the charge-induced phases are rather finite and stable, the magnetic signal can even vanish.

Experimentally, we expect both signals, magnetic and charge-induced to be measured. To differentiate the two, we explore how the acceleration voltage affects the magnitude of the charge-induced phases. As a reminder the phase induced by the magnetization stray field is voltage-independent. In Fig. 5 (g), the ratio of the total electronic non-collinearity induced and magnetic contribution to the phase-image are shown as function of the acceleration voltage u and diameter d of a spin texture, here the Bloch-type skyrmion-tube. While typically an acceleration voltage of 300 keV is used, we predict that reducing both the voltage and the skyrmion diameter enhances the amplitude of the charge-induced phase. Relatively low voltages (even below 100 keV) can induce significant charge-induced phases. This is a general behavior for the isotropic and chiral contributions, which also holds true for different spin textures.

Discussion

By demonstrating that the charge pertaining to a magnetic state changes in a non-trivial fashion when the magnetic moments are perturbed, we identified analytically that the underlying induced charge follows specific dependencies with respect to the angle between the magnetic moments. This implies that the electronic signal, not considered so far when analysing experimentally TEM electron-holographic images, contains crucial information on non-trivial magnetic states.

Our findings unveiling isotropic, anisotropic and chiral contributions to the images accessible experimentally, opening perspectives in the realm of 3D spin textures probed via TEM. Similar concepts have been shown to be crucial for the visualization of spin textures via scanning tunneling spectroscopy41,42,43.

The textures of the phase images are rich and distinct when comparing the conventional magnetic ones to the charge-induced ones. The interplay of both contributions to the total signal can be complex depending on the underlying spin textures. Here, we addressed and compared signals pertaining to Néel and Bloch skyrmion-tubes as well as hopfions.

An appealing procedure to identify the previously neglected signal would be to proceed to a study as a function of the acceleration voltage of the TEM’s electron beams and size of the spin textures. The latter can be controlled by applying a magnetic field44. Measurements with arbitrary acceleration voltages are probably challenging currently, but future developments in this context might lead to breakthroughs. We highlight that such an idea has been used on the basis of LTEM45. Furthermore, a simple way to remove the magnetic contribution consists in flipping the sample, followed by a subtraction of the two signals (before and after flipping).

So far, the charge-induced signals were evaluated without accounting for self-consistency in the response of the charge to the magnetic texture. This assumption is more justified for large spin textures with a relatively small misalignment of the magnetic moments, which is then expected to be associated with a small change in charge per site. This, however, does not affect the generality of our findings, namely the different types of dependencies with respect to the angles between the magnetic moments. In Supplementary Note 1, we compare the perturbative approach with the exact solution for a dimer.

The surge for exploring complex spin textures in 3D calls for the invention of new experimental methodologies. Here, we demonstrate that “conventional" TEM setups can readily be utilized to explore an intriguing emergent phenomenon, overlooked so far. We foresee new developments that will enable the observation of magnetic-induced charges, which will be one additional milestone for the identification of 3D spin textures and their potential use as magnetic bits in information technology.

Methods

Induced charge

In order to calculate the induced charge from non-colinearity of magnetic moments, we separate the Hamiltonian in Eq. (1) in two different contributions: local terms V and hopping terms T, containing the interaction between different atomic sites. The Green function associated to the non-interacting system g can be easily evaluated. It can be used to construct the interacting Green function G by solving the Dyson equation

where we have used

Obtaining the Green function clearly involves matrix inversion and multiplication, which can be computationally extremely challenging for huge matrices. Since we do not want to restrict ourselves to small systems we need an approximate scheme which can deal efficiently with huge systems. The Dyson equation can be solved in a perturbative fashion by realizing that it can be expressed in the open form

This open form serves as the foundation for the perturbative approach, enabling an analytical approximation of the full Green function by neglecting higher-order terms in T.

Starting from Eq. (8), we consider only the first non-vanishing correction to the density of states (dos). The density of states is related to Green function:

ℑ stands for the imaginary part, Trσ represents the trace over the spin-channel and j is labelling the sites. By combining the definitions of the dos (Eq. (9)) and the Dyson equation (Eq. (8)), we arrive at a perturbative expansion for the dos at site j

Here, we utilize the fact that hopping is purely non-local, meaning that Tii = 0. As a result, the first-order correction in T vanishes, allowing us to focus on the second-order correction. Naturally, the accuracy of the results would depend on the amplitude of the hopping. It is thus important to exercise caution when interpreting the results, as even non-physical phenomena may arise when a strong hopping t is employed. However, for small values of t, this approximation can provide reasonably accurate quantitative outcomes for the utilized Hamiltonian. The charge is obtained by integrating the DOS over the energy

Rashba model

Starting from Eq. (1), we focus on the hopping32 contribution to the Hamiltonian:

and shortly demonstrate the connection to the Rashba model31. Assuming for simplicity a two-dimensional simple cubic lattice and periodicity, we perform a Fourier transformation and obtain

where k is given in units of the inverse lattice constant.

For small values of k we recover the Rashba-type formulation of the Hamiltonian

which can be compared to the usual form: \({\sum }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}{\alpha }_{{{{\rm{R}}}}}({\sigma }_{{{{\rm{x}}}}}{k}_{{{{\rm{y}}}}}-{\sigma }_{{{{\rm{y}}}}}{k}_{{{{\rm{x}}}}})\,{c}_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{{{\dagger}} }{c}_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}\) thereby identifying the so-called Rashba-parameter αR to be proportional to the sine of the Rashba-angle.

Electronic contribution to electron holography

The electronic contribution demands the development of a method that is consistent with the approach used for the magnetic part. We recall the definition of the electronic contribution to the phase-image and insert the Poisson’s equation:

which involves a fundamental problem: the long-range nature inherent to the Coulomb potential causes divergence of the phase-shift. Therefore, we incorporate Thomas-Fermi screening with the screening parameter ktf

There is still a critical issue to address. Upon careful examination of Eq. (17) or Eq. (18) it becomes apparent that the integral diverges for \({{{\bf{r}}}}={{{{\bf{r}}}}}^{{\prime} }\). This divergence stems from the singular nature of the point charge. To resolve this challenge, we address the point charge singularity by spreading it into a uniform charge distribution within a sphere of radius R

Here, θ denotes the Heaviside function and Vsphere(R) corresponds to the volume of a sphere with radius R. The integration with respect to \(\widetilde{{{{\bf{r}}}}}\) can be treated analytical, while the remaining integration are solved numerically.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on request.

References

Bogdanov, A. & Yablonskiui, D. Thermodynamically stable “vortices" in magnetically ordered crystals. The mixed state of magnets. Sov. Phys. JETP 68, 101 (1989).

Rößler, U. K., Bogdanov, A. N. & Pfleiderer, C. Spontaneous skyrmion ground states in magnetic metals. Nature 442, 797–801 (2006).

Pappas, C. et al. Chiral paramagnetic skyrmion-like phase in MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 197202 (2009).

Neubauer, A. et al. Topological Hall effect in the A phase of MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 186602 (2009).

Mühlbauer, S. et al. Skyrmion lattice in a chiral magnet. Science 323, 915–919 (2009).

Milde, P. et al. Unwinding of a skyrmion lattice by magnetic monopoles. Science 340, 1076–1080 (2013).

Birch, M. T. et al. Real-space imaging of confined magnetic skyrmion tubes. Nat. Commun. 11, 1726 (2020).

Seki, S. et al. Direct visualization of the three-dimensional shape of skyrmion strings in a noncentrosymmetric magnet. Nat. Mater. 21, 181–187 (2022).

Rybakov, F. N., Borisov, A. B., Blügel, S. & Kiselev, N. S. New type of stable particlelike states in chiral magnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 117201 (2015).

Zheng, F. et al. Experimental observation of chiral magnetic bobbers in B20-type FeGe. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 451–455 (2018).

Ran, K. et al. Creation of a chiral bobber lattice in helimagnet-multilayer heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 017204 (2021).

Whitehead, J. H. C. An expression of Hopf’s invariant as an integral. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 33, 117–123 (1947).

Tai, J.-S. B. & Smalyukh, I. I. Static Hopf solitons and knotted emergent fields in solid-state noncentrosymmetric magnetic nanostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 187201 (2018).

Sutcliffe, P. Hopfions in chiral magnets. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 51, 375401 (2018).

Sutcliffe, P. Skyrmion knots in frustrated magnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 247203 (2017).

Kent, N. et al. Creation and observation of hopfions in magnetic multilayer systems. Nat. Commun. 12, 1562 (2021).

Zheng, F. et al. Hopfion rings in a cubic chiral magnet. Nature 623, 718–723 (2023).

Tonner, B. P. & Harp, G. R. Photoelectron microscopy with synchrotron radiation. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 59, 853–858 (1988).

Stöhr, J. et al. Element-specific magnetic microscopy with circularly polarized x-rays. Science 259, 658–661 (1993).

Janzen, E. G. & Blackburn, B. J. Detection and identification of short-lived free radicals by electron spin resonance trapping techniques (spin trapping). photolysis of organolead,-tin, and-mercury compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 91, 4481–4490 (1969).

Chapman, J. N. The investigation of magnetic domain structures in thin foils by electron microscopy. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 17, 623 (1984).

Gabor, D. Microscopy by reconstructed wave-fronts. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A. Math. Phys. Sci. 197, 454 – 487 (1949).

Tonomura, A. Electron-holographic interference microscopy. Adv. Phys. 41, 59–103 (1992).

McCartney, M. & Smith, D. Electron holography: Phase imaging with nanometer resolution. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 37, 729–767 (2007).

Midgley, P. & Dunin-Borkowski, R. Electron tomography and holography in materials science. Nat. Mater. 8, 271–80 (2009).

Kasama, T., Dunin-Borkowski, R. & Beleggia, M.Electron Holography of Magnetic Materials, 53–80 (InTech, 2011).

Wolf, D. et al. Holographic vector field electron tomography of three-dimensional nanomagnets. Commun. Phys. 2, 87 (2019).

Phatak, C., Beleggia, M. & De Graef, M. Vector field electron tomography of magnetic materials: Theoretical development. Ultramicroscopy 108, 503–513 (2008).

Hierro-Rodriguez, A. et al. Revealing 3d magnetization of thin films with soft X-ray tomography: magnetic singularities and topological charges. Nat. Commun. 11, 6382 (2020).

Anderson, P. W. Localized magnetic states in metals. Phys. Rev. 124, 41–53 (1961).

Bychkov, Y. A. & Rashba, E. I. Oscillatory effects and the magnetic susceptibility of carriers in inversion layers. J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 17, 6039 (1984).

Chaudhary, G., dos Santos Dias, M., MacDonald, A. H. & Lounis, S. Anatomy of magnetic anisotropy induced by Rashba spin-orbit interactions. Phys. Rev. B 98, 134404 (2018).

Dzyaloshinskii, I. E. Thermodynamic theory of weak ferromagnetism in antiferromagnetic substances. Sov. Phys. JETP 5, 1259–1272 (1957).

Moriya, T. New mechanism of anisotropic superexchange interaction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 4, 228 (1960).

Moriya, T. Anisotropic superexchange interaction and weak ferromagnetism. Phys. Rev. 120, 91 (1960).

Zheng, F. et al. Towards three-dimensional mapping of skyrmionic spin textures in an FeGe nanodisk using off-axis electron holography. Microsc. Microanalysis 29, 1396–1397 (2023).

Midgley, P. An introduction to off-axis electron holography. Micron 32, 167–184 (2001).

Caron, J. Model-based reconstruction of magnetisation distributions in nanostructures from electron optical phase images. Ph.D. thesis, Dissertation, RWTH Aachen University, 2017 (2017).

Denneulin, T. et al. Off-axis electron holography of néel-type skyrmions in multilayers of heavy metals and ferromagnets. Ultramicroscopy 220, 113155 (2021).

Park, H. S. et al. Observation of the magnetic flux and three-dimensional structure of skyrmion lattices by electron holography. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 337–342 (2014).

Lima Fernandes, I., Blügel, S. & Lounis, S. Spin-orbit enabled all-electrical readout of chiral spin-textures. Nat. Commun. 13, 1576 (2022).

Crum, D. M. et al. Perpendicular reading of single confined magnetic skyrmions. Nat. Commun. 6, 8541 (2015).

Hanneken, C. et al. Electrical detection of magnetic skyrmions by tunnelling non-collinear magnetoresistance. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 1039–1042 (2015).

Romming, N., Kubetzka, A., Hanneken, C., von Bergmann, K. & Wiesendanger, R. Field-dependent size and shape of single magnetic skyrmions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 177203 (2015).

Kohn, A., Petford-Long, A. K. & Anthony, T. C. Magnetic potential in patterned materials determined using energy-dependent lorentz phase microscopy. Phys. Rev. B 72, 014444 (2005).

Wang, X. S., Qaiumzadeh, A. & Brataas, A. Current-driven dynamics of magnetic hopfions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 147203 (2019).

Hietarinta, J. & Salo, P. Faddeev-hopf knots: dynamics of linked un-knots. Phys. Lett. B 451, 60–67 (1999).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge fruitful discussions with Rafal Dunin-Borkowski. This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) within the SPP 2137 “Skyrmionics” (Project LO 1659/8-1, S.L.) and as part of the German Excellence Strategy -EXC3112/1 -533767171 (Center for Chiral Electronics).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L. initiated, designed and supervised the project. M.W. derived the theoretical framework and performed the simulations. Both authors wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Winterott, M., Lounis, S. Unlocking hidden potential in electron holography of non-collinear spin textures. Commun Phys 8, 466 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02422-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02422-5