Abstract

Nonreciprocal supercurrent refers to the phenomenon where the maximum dissipationless current in a superconductor depends on its direction of flow. This asymmetry underlies the operation of superconducting diodes and is often associated with the presence of vortices. Here, we investigate supercurrent nonreciprocal effects in a superconducting weak-link hosting distinct types of vortices. We demonstrate how the winding number of the vortex, its spatial configuration, and the shape of the superconducting lead can steer the sign and amplitude of the supercurrent rectification. We identify a general criterion for optimizing the rectification amplitude based on vortex patterns, focusing on configurations where the first harmonic of the supercurrent vanishes. We prove that supercurrent nonreciprocal effects can be used to diagnose high-winding vortex and to distinguish between different types of vorticity. Our results provide a toolkit for controlling supercurrent rectification through vortex phase textures and detecting unconventional vortex states.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vortices represent fundamental topological excitations in superfluids and superconductors. They have been predicted and successfully observed in a broad range of systems, including superconductors1, liquid helium2,3,4, ultracold atomic gases5, photon fields6, and exciton-polariton condensates7,8. Vortices are generally characterized by a quantized phase winding and a suppressed order parameter at their core. A gradient of the phase ϕ of the superconducting order parameter \(\Delta =| \Delta | \exp (i\phi )\) yields a circulating supercurrent around the core of the vortex, whereas the amplitude is vanishing, i.e. ∣Δ∣ → 0. For conventional superconductors, due to the single-valuedness of the superconducting order parameter, the winding number associated with the phase gradient is forced to be an integer V0. In principle, V0 can assume values larger than one. Apart from having V0 vortices with winding number equal to one, a giant vortex with winding number V0 can also be realized. A giant vortex is expected to be relevant in small superconductors with confined geometries. To date, probing of such unconventional vortex state has been mostly addressed by magnetic means in suitably tailored geometric configurations, e.g., by Hall probe9,10,11 and scanning SQUID microscopy12, or by tunneling microscopy and spectroscopy13,14,15,16,17.

Here, we unveil a specific relation between the occurrence of vortex states with any given winding number in a Josephson weak-link and the rectification of the supercurrent flowing across the junction. Supercurrent rectification is a timely problem at the center of intense investigation18,19,20,21,22,23,24. A large body of work devoted to supercurrent rectification focuses on superconducting states marked by linear phase gradients with, for instance, Cooper pair momentum25,26,27, spin-flipper by ferromagnets28, or helical phases29,30,31,32,33, as well as screening currents34,35, and supercurrent related to self-field36,37 or back-action mechanisms38. Vortices or circular phase gradients, associated to conventional winding, are also expected to yield supercurrent diode effects, due to the induced Josephson phase shift39, and their role has been investigated for a variety of physical configurations37,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49. However, whether and how superconducting phase patterns with nontrivial winding for the vorticity can be probed by nonreciprocal response, which are problems not yet fully uncovered.

By studying nonreciprocal supercurrent effects arising from distinct types of vortex phase texture in Josephson weak-links, in this paper, we show that while a superconducting phase with vortices can generally lead to nonvanishing supercurrent rectification, the sign and amplitude of the rectification in the Josephson diode effect can be manipulated by the position of the vortex core and the winding of the phase vortex. We thereby uncover a general criterion to single out which phase vortex configuration can maximize the rectification amplitude of the supercurrent. Our findings provide a toolkit for the design and control of supercurrent rectification by vortex phase texture.

Results and Discussion

In this section, we study the supercurrent rectification by examining one and two vortices situated within the superconducting lead of the junction and assuming that the core position can be varied and it can be marked by different winding numbers. We would like to point out that to realize nonreciprocal superconducting phenomena, it is essential to break both inversion and time-reversal symmetries. This condition is crucial for establishing nonreciprocal behavior in superconducting transport, and it can be directly inferred in a superconducting weak link, for example, from the parity properties of the current-phase relation with respect to the phase bias. In the examined system, these symmetries are broken by the presence of vortices in the superconducting leads. Specifically, when analyzing the junction with either one or two vortices, the system lacks a center of inversion and is not invariant under time-reversal symmetry. For example, considering a single vortex on one side of the junction, there are no inversion centers, and the phase pattern does not remain invariant under time reversal. These symmetry considerations directly influence the current-phase relation of the Josephson junction. Specifically, the relation features a first harmonic with even parity, which implicitly reflects the broken time-reversal symmetry. Additionally, the second harmonic contains both even- and odd-parity components with respect to the applied phase bias. Although the odd-parity component can exist regardless of the vortex presence when the junction is outside the tunneling regime, the even-parity contribution arises from the vortex-induced symmetry breaking. Then, we note that the rectification amplitude is generally nonzero when a nontrivial even-parity first harmonic coexists with the second harmonic component. Our results thus will demonstrate that the vortex plays a role in the rectification process of the supercurrent by generating a nonzero even-parity first harmonic term. In particular, the position of the vortex affects both the amplitude of the first harmonic term and the second harmonic component, too, thus resulting in a modulation of the sign and amplitude of the supercurrent rectification. Here, we adopt a superconducting phase profile designed to qualitatively capture the main features of the giant vortex as observed in relevant experiments13,15,50,51,52 and discussed in several theoretical studies53,54,55,56,57,58,59. However, this approach does not incorporate the boundary-induced corrections required to fully satisfy supercurrent conservation at the sample edges. While such corrections are known to play a crucial role in stabilizing high-winding-number vortices, particularly in finite-size systems54,55,56,57,58,59 or in the presence of strong pinning53, we point out that a self-consistent treatment of the superconducting phase, accounting for boundary effects, lies beyond the scope of the present study.

Supercurrent rectification: single vortex configuration

To investigate the rectification properties of the supercurrent in the junction, we start by considering a single vortex configuration assuming a variable winding number and core position as illustrated in Fig. 1. The vortex is placed on the left side of the junction, but the results for vortices on the right side of the junction can be directly obtained by applying an inversion symmetry transformation and considering that it leads to a sign variation of the rectification amplitude (see Supplementary Info - Section B). Antivortex configurations through mirror and time-reversal transformations can also be directly deduced from the results of the single vortex (see Supplementary Info - Section B). To simulate the vortex state with the core at a given position, \({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=({x}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{y}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})\), the phase value at the site j in the left-side superconductor is given by (Fig. 2a)

with \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) being the winding number of the vortex. \({\varphi }_{{{{\rm{v}}}}}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}( \, {{{\boldsymbol{j}}}},{{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})\) reverses its sign by changing the sign of \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\), and \(| {V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}|\) corresponds to the number of sign changes in the real space j for the phase value when winding around the core of the vortex. The pair potential ΔL and ΔR for spin-singlet s-wave state are given by

and ΔR = ∣Δ0∣ with ∣Δ0∣ = 0.02t being the superconducting energy gap amplitude. In the presence of a phase vortex texture, the amplitude of the pair potential ΔL is modified by \({\widetilde{\Theta }}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}( \, {{{\boldsymbol{j}}}},{{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})\) for each site j:

with \({z}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=10a\) being the vortex size.

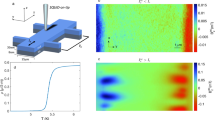

a Schematic of a Josephson junction in the lattice model with a vortex phase texture. SC-L, N, and SC-R mean the Left-side superconductor (SC), the Normal metal, and the Right-side SC. \({N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\), \({N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{R}}}}}\), \({N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{N}}}}}\), Ny, and a denote the number of sites in the left and right-side SCs, and in the normal metal along the x-direction, and number of sites along the y-direction, and lattice constant. \({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=({x}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{y}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})\) is the core position. b A representative nonreciprocal current phase relation with φ being the phase bias across the junction. c, d Sketch of the superconducting weak link with a vortex placed on the left side of the junction. We show two representative vortex positions along the lateral direction. Since the supercurrent pattern is spatially modified by the phase vortex, it can become nonreciprocal, i.e., the forward supercurrent I+ is different from the backward one I−. The vortex winding, \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\), can take any integer number l.

a Schematic illustration of the Josephson junction with real-space coordinates. The analysis is performed for a vortex configuration having winding number \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=+l\) with l = 1, 2, 3. SC-L, N, and SC-R mean the Left-side superconductor (SC), the Normal metal, and the Right-side SC. \({N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\), \({N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{R}}}}}\), \({N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{N}}}}}\), Ny, and a denote the number of sites in the left and right-side SCs, and in the normal metal along the x-direction, and number of sites along the y-direction, and lattice constant. Evolution of the rectification amplitude η with regard to the vortex core coordinates for different winding numbers: (b, c) \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=1\), (f, g) \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=2\), and (j, k) \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=3\). Spatially resolved harmonics of the supercurrent: I1 (red-solid line), I2 (green-dotted), and J1 (blue-dashed) indicate the odd-parity first harmonic, the odd-parity second harmonic, and the even-parity first harmonic amplitude, respectively. Longitudinal scan: I1, I2, and J1 at a given \({y}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) as a function of \({x}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) for (d) \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=1\), (h) \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=2\), and (l) \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=3\). Lateral scan: I1, I2, and J1 at a given \({x}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) as a function of \({y}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) for (e) \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=1\), (i) \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=2\), and (m) \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=3\). The gray dotted lines refer to the position of the maximal rectification and are a guide to indicate the values I1, I2, and J1. We set \({y}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) as (b, d) 0.5a and (f, h, j, l) 5.5a, and \({x}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) as (c, e, g, i) − 23a and (k, m) − 6a. The aspect ratio is (b–i) α = 3/2 and (j–m) α = 1. The maximal rectification η occurs for vortex core positions corresponding to a supercurrent with I1, I2, and J1 components that are comparable in size. The sign change of η is related to the vanishing of J1 and to the zeros of I1 when the amplitude is comparable to J1. Multiple sign reversals of η are observed for \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=3\). Parameters: ∣Δ0∣ = 0.02t (superconducting energy gap amplitude), tint = 0.90 (transparency at the interface), \({N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{N}}}}}=10\), Ny = 30, and \({z}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=10a\) (vortex size).

In Fig. 2b–m, we display the rectification amplitude for various vortex winding values while altering the position of the vortex core. We consider α = 3/2 and α = 1 as representative cases for the aspect ratio of the superconducting lead. The analysis for all vortex windings is performed by scanning the vortex core position within the superconducting lead along the longitudinal (x) and lateral direction y. We start by considering a conventional vortex with winding \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=1\). The outcome of the study indicates that the rectification tends to vanish and changes the sign if the vortex core is placed at the crossing of the longitudinal and transverse mirror lines of the left superconducting lead [Fig. 2 (b,c)]. For the geometry of the junction, these symmetry lines correspond to the y ~ 0 and x ~ − 22a axes. Other vortex core positions away from the symmetry lines give a negligible rectification. One can also observe that the maximum of the rectification occurs nearby these nodal points at a distance that is set by the vortex core size \({z}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\). The behavior of the supercurrent rectification can be understood by inspection of the amplitude of the first harmonics in the current phase relation. For instance, placing the vortex core along the longitudinal direction at a different distance from the interface, we find that the value of the first odd-parity harmonic (I1) changes sign at x ~ − 22a [Fig. 2 (d)]. Then, this configuration allows for a sign change of the time-conserving component of the supercurrent and thus for an effective 0-π Josephson phase transition. For such a position, one can observe that the even-parity first harmonic (J1) and the odd-parity second harmonic (I2) components have a small amplitude and are comparable to that of I1. Instead, when considering the evolution of η as a function of the lateral coordinate y we find that the sign change of η occurs nearby y ~ 0. Now, the sign reversal is guided by the first even-parity harmonic term (J1) in the current phase relation [Fig. 2e]. The J1 component sets out the amplitude of the spontaneous supercurrent induced by the presence of the vortex at zero applied phase bias (i.e., φ = 0). Both the scan along the x and y directions indicate that the rectification amplitude is maximal (of the order of 20%) for vortex core positions \({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) that correspond to configurations for which the first harmonics of the supercurrent have comparable strength. This tendency towards optimal rectification of the supercurrent is an expected outcome that can be directly inferred from the analysis of a Josephson system exhibiting current-phase relationships with generic yet comparable amplitudes for (I1), (I2), and (J1) (60) (see Supplementary Info - Section B). In Section C of the Supplementary Info, we present the current-phase relationship profiles for several representative vortex configurations. The harmonic content depicted in Fig. 2 has been derived from the current-phase relationships evaluated for each corresponding vortex configuration.

Moving to even high-winding, \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=2\), we find that the maximal amplitude of the rectification occurs for vortex core positions that are now closer to the lateral edges of the superconductor but still midway from the interface (Fig. 2f, g). Inspection of the harmonic content of the current phase relation confirms that the sign change of the rectification amplitude η occurs when J1 reverses its sign (Fig. 2h, i). Furthermore, we find that the sign change of η does not directly follow the I1 sign change and the maximum of the rectification (η ~ 25%) arises for vortex core positions whose I1, I2, and J1 have comparable size. Let us then consider a vortex with odd high-winding number \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=3\) assuming a square (α = 1) shape for the superconducting lead (Fig. 2j–m). For \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=3\), we observe that the maximal values of the rectification amplitude occur for the vortex core position that is away from the mirror lines of the superconducting lead (Fig. 2j, k). The rectification can reach 30% amplitude, and there are multiple positions of the vortex core for which η is vanishing (Fig. 2j, k). Now, when considering the specific case of the current phase relation in the presence of a vortex, since the second harmonic components are usually smaller than the first harmonic, then the condition to become comparable in amplitude is usually met when the first harmonics are vanishingly small or change sign. This happens, e.g., nearby \({x}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=22a\) or 7a, and in general, nearby the points where the first harmonics become vanishing. In this context, the appearance of a dip and the peak around specific vortex core positions (see Fig. 2b) results from the simultaneous fact that the first odd-parity harmonic reverses sign and that the amplitudes of the first and second harmonics are of similar magnitude.

The analysis indicates that a key element to maximize the rectification is represented by the search for vortex configurations for which the first harmonics (even and odd-parity) are concomitantly almost vanishing. This is a general rule to get large rectification60 (see Supplementary Info - Section D). To this aim, one can make an analytical analysis of the first harmonics by considering the direct process of Cooper pairs transfer across the junction as given by61,62

Taking into account the form of the superconducting order parameter we have that:

This relation is general and can be applied to any type of vortex phase texture. Here, from this expression, we can deduce how the nonreciprocal supercurrent directly links to the winding of the phase vortex. Focusing on the coefficients of \(\sin \varphi\) and \(\cos \varphi\), the structure of the vortex indeed directly impacts the even and odd-parity components of the first harmonics of the supercurrent. For convenience and in order to primarily extract the angular dependence of the harmonic content, we neglect the amplitude variation in the vortex core. Hence, the effective first harmonics components \({\bar{I}}_{1}({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})\) and \({\bar{J}}_{1}({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})\) of \(\widetilde{I}\) are substantially given by

We checked that the spatial variation of the superconducting order parameter in the core of the vortex does not alter the qualitative conclusions of the analysis.

We find that their nodal lines can cross in different sites depending on the winding number and aspect ratio of the superconducting lead [Fig. 3]. In particular, for the case of even winding, \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=2\), the breaking of C4 rotational symmetry for a rectangular-shaped superconductor induces a shift of the nodal line of the odd-harmonic \({\bar{I}}_{1}\) towards the edge of the superconductor (Fig. 3d, e). Then, the crossing with the nodal lines for \({\bar{J}}_{1}\) shifts from \(({x}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{y}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})=(-22a,0)\) to \(({x}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{y}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}) \sim (-22a,\pm 10.5a)\). When considering a vortex with winding \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=3\), due to the higher angular components, the crossings of the vanishing lines for \({\bar{I}}_{1}\) are in multiple points within the superconducting domain at \(({x}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{y}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}) \sim (-7a,\pm 7.5a)\) and ( − 22a, ± 7.5a) [Fig. 3g, h). To verify how the spatial profile of the rectification amplitude varies with different vortex states characterized by their winding numbers, we performed numerical computations of the supercurrent in the superconducting junction. These calculations reveal that the rectification pattern exhibits distinct spatial features depending on the vortex winding number. As illustrated in Fig. 3c, f, i, the pattern of rectification amplitude changes qualitatively with different vortex states. Specifically, for the case where the vortex has a winding number \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=1\), there is a single region where the rectification amplitude vanishes. This region corresponds to the mirror symmetry line with respect to the transformation y → − y. The sign change of the rectification amplitude primarily occurs when crossing this horizontal mirror line at y = 0. In contrast, for a vortex with winding number \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=2\), the spatial pattern features two lines where the rectification amplitude changes sign. These sign-change lines are associated with the vortex core’s position relative to the interface, which can move from regions far from the interface to those closer to it. As the vortex winding number increases further to \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=3\), the number of nodal lines—i.e., lines where the rectification amplitude vanishes—expands to four, indicating a more complex spatial structure of the supercurrent distribution influenced by the vortex’s winding number. These findings confirm the qualitative expectation based on the analysis of the first harmonics of the current phase relation.

Amplitude of the first harmonics of the Josephson current and the rectification versus the vortex core positions \({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=({x}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{y}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})\) for different vortex winding \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\): (a–c) \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=1\), (d–f) \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=2\), (g–i) \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=3\). \({\bar{I}}_{1}\), \({\bar{J}}_{1}\), and η indicate the odd- and even-parity first harmonics of the supercurrent evaluated by the direct Cooper pairs tunneling and the amplitude of the rectification. The color bars indicate the amplitude of (a, d, g) \({\bar{I}}_{1}({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})\), (b,e,h) \({\bar{J}}_{1}({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})\), and (c, f, i) the rectification amplitude η. In (a, b, d, e, g, h), gray-dotted and dashed lines stand for the vortex core positions, \({y}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) and \({x}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\), evaluated in Fig. 2. The aspect ratio is (a–f) α = 3/2 and (g–i) α = 1. In (c, f, i), the rectification amplitude is evaluated by scanning all the positions of the vortex cores by performing the computation of the supercurrent for the weak link, assuming the following parameters: ∣Δ0∣ = 0.02t (superconducting energy gap amplitude), tint = 0.90 (transparency at the interface), \({N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{N}}}}}=10\), Ny = 30, and \({z}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=10a\) (vortex size).

Supercurrent rectification: two-vortex configuration

Next, we show the rectification caused by two vortices in one lead of the superconducting junction. The pair potential with two vortices in the left-side superconductor is expressed by:

with

the size of vortices \({z}_{m}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\), and the core positions \({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{m}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=({x}_{m}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{y}_{m}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})\) for m = 0, 1. Each phase vortex is given by

where V m is the number of windings for each phase vortex.

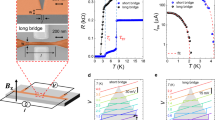

We plot the rectification and Josephson components (I1, I2, and J1) as a function of the literal direction \({\widetilde{y}}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) in a representative case [Fig. 4]. Then we set the position of one phase vortex at \(({x}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{y}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})=(-30a,0.5a)\). We choose each winding number as (Fig. 4b, d) \(({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{V}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})=(+1,+1)\) and (c,e) \(({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{V}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})=(+1,-1)\). For \(({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{V}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})=(+1,+1)\), the rectification is enhanced up to 40% near \({y}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=0\) (Fig. 4b) owing to the comparable Josephson components ∣I1∣ ~ ∣I2∣ ~ ∣J1∣ (Fig. 4d). On the other hand, for \(({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{V}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})=(+1,-1)\), because ∣I1∣ is larger than ∣I2∣ and ∣J1∣ (Fig. 4e), the amplitude of the rectification is small compared with that for \(({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{V}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})=(+1,+1)\) (Fig. 4c). Thus, the same sign for winding is favorable for enhancing the rectification.

a Schematic illustration of two vortices in the left-side superconductor. SC-L, N, and SC-R mean the Left-side superconductor (SC), the Normal metal, and the Right-side SC. \({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{m}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=({x}_{m}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{y}_{l}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})\) with m = 1, 2 indicate core position for each vortex. \({V}_{0,1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) mean the winding number of each phase vortex. \({N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\), \({N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{R}}}}}\), \({N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{N}}}}}\), Ny, and a denote the number of sites in the left and right-side SCs, and in the normal metal along the x-direction, and number of sites along the y-direction, and lattice constant. b, c Rectification η and (d, e) I1, I2, J1 as a function of the literal direction \({y}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) for each (b, d) \(({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{V}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})=(+1,+1)\) and (c, e) \(({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{V}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})=(+1,-1)\). We set the core positions as \(({x}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{y}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})=(-30,0.5)\) and \({x}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=-15\). I0 = 0.122∣Δ0∣(2e/ℏ) stands for the maximum Josephson current without any phase vortices in superconductors. We select the parameters: ∣Δ0∣ = 0.02t (superconducting energy gap amplitude), tint = 0.90 (transparency at the interface), \({N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}={N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{R}}}}}=45\), \({N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{N}}}}}=10\), Ny = 30, and \({z}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}={z}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=10a\) (each vortex size).

Based on the discussion in the case of one-phase vortex, we can also define \({\bar{I}}_{1}\) and \({\bar{J}}_{1}\) in this case. \({\bar{I}}_{1}({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})\) and \({\bar{J}}_{1}({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})\) are given by

with \({\varphi }_{{{{\rm{v}}}}}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}( \, {{{\boldsymbol{j}}}},{{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})={\varphi }_{{{{\rm{v}}}}0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}( \, {{{\boldsymbol{j}}}},{{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})+{\varphi }_{{{{\rm{v}}}}1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}( \, {{{\boldsymbol{j}}}},{{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})\). Fixing the position of one phase vortex at \(({x}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{y}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})=(-30a,0.5a)\), we plot \({\bar{I}}_{1}({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})\) and \({\bar{J}}_{1}({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})\) for the \({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) space as shown in Fig. 5. For \(({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{V}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})=(+1,+1)\) shown in Fig. 5a, c, since nodal lines appear around \({x}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}} \sim -11a\) for \({\bar{I}}_{1}\) and \({y}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}} \sim 0\) for J1, the amplitude of I1 and J1 are small near these lines, respectively. For \(({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{V}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})=(+1,-1)\), we obtain \({\bar{I}}_{1}\le 0\) and the nodal line around \({y}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}} \sim 0\) for J1 (Fig. 5b, d). Based on these \({\bar{I}}_{1}\) and J1, ∣I1∣ is larger than I1 and J1 (Fig. 4d). Thus, using \({\bar{I}}_{1}\) and \({\bar{J}}_{1}\) is generic way to express I1 and J1.

a, b \({\bar{I}}_{1}\) and (c, d) \({\bar{J}}_{1}\) for the \({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=({x}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{y}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})\) space at (a, c) \(({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{V}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})=(+1,+1)\) and (b, d) \(({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{V}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})=(+1,-1)\). The color bars indicate the amplitude of (a, c) \({\bar{I}}_{1}({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})\) and (b, d) \({\bar{J}}_{1}({{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})\). We set the core positions as \(({x}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}},{y}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}})=(-30a,0.5a)\) and the vortex size as \({z}_{1}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=10a\) (\({N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}={N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{R}}}}}=45\) and Ny = 30). The Gray line indicates the scanning site in Fig. 4.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that nonreciprocal supercurrents are achieved in the presence of high-winding vortex and multiple vortices. The resulting behavior contains distinct features that can be exploited to distinguish physical configurations with vortices having winding number equal to one, coexistence of vortices and antivortices, or the occurrence of a giant vortex. In particular, we uncover the spatial profile of the supercurrent rectification with respect to the vortex core position. The rectification pattern depends on the number of windings, with an increase in the winding number producing more complex nodal structures. We find that for \({V}_{{{{\rm{0}}}}}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=1\), a single sign change line exists, while for 2 and 3, multiple lines and nodal points appear, demonstrating how winding number shapes the spatial rectification behavior. Our findings indicate that the achieved vortex diodes do not exhibit a high rectification efficiency. However, in this context, unlike semiconducting diodes, there are no fundamental reasons to exclude the use of superconducting diodes in superconducting electronics and quantum circuitry, even if their rectification efficiency does not reach 100%. Recent reports indeed highlighted the potential use of superconducting diodes in diverse applications63,64,65, demonstrating that even with low rectification efficiencies, superconducting diodes can effectively perform functions such as alternating current (AC) to direct current (DC) conversion and rectification. In particular, one of the primary applications of superconducting diodes involves converting AC to DC at low temperatures to generate stable and adjustable DC bias currents from radiofrequency signals. They achieve this with a rectification efficiency below 50% exploiting vortex dynamics, with the nonreciprocal critical current that arises from the asymmetric expulsion of vortices from the superconducting nanostructure. In our vortex diode design, instead, we assume that the nonreciprocal supercurrent can be controlled by the vortex position within the junction, without the need to move the vortex itself, where one can achieve rectification amplitudes of the order of 30%. In this framework, it is worth pointing out that, with respect to the design of vortex diodes and control knobs, vortices can be manipulated (e.g., displaced, introduced, or removed) by magnetic field39,66,67, current68,69,70, light71,72, and mechanical strain73.

We would like to discuss how the achieved results depend on system parameters like temperature, junction interface, and disorder. Within our model description, the effects of temperature are to substantially reduce the amplitude of the superconducting order parameter. Hence, we do not expect qualitative changes but rather a modification of the amplitude of the supercurrent. Regarding the disorder, as shown in Section D of the Supplementary Information, we find that the rectification amplitude is not much altered by the local disorder potential. What is more relevant is the junction transparency as it enters to modify the second harmonic component of the supercurrent, as predicted by the Kulik-Omelyanchuk theory, for a superconducting weak link. We have examined the rectification amplitude for a representative vortex configuration in terms of the junction transparency for a representative vortex configuration (see Supplementary Information - Section D). Our results confirm that the rectification amplitude gets suppressed when the superconducting junction is brought into the tunneling regime.

It is also interesting to comment on the possibility of having a coexistence of vortex states and finite momentum pairing, a physical scenario that might lead to nontrivial effects for the superconducting vortex diode. However, it is unlikely that the vortex phase enables the formation of finite momentum pairing. This can happen for large values of the applied magnetic field when a vortex lattice can coexist with a finite momentum pairing of the FFLO type74). This is, however, in a regime of an applied magnetic field, which is beyond the examined cases in our paper because the coexistence occurs close to the upper critical field. Our study refers to a small applied magnetic field where only a few vortices nucleate into the superconductor.

We would also like to mention that our results refer to short superconducting junctions. In short Josephson junctions, the current phase relation’s structure and strong coupling can enhance diode efficiency by creating pronounced asymmetries. Instead, long Josephson junctions (LJJs), with their complex phase dynamics and fluxon motion, can manifest different mechanisms for the diode effect. The fluxonium diode, for instance, employs a control line to induce magnetic field asymmetry, though its performance remains not fully tested75,76. Another concept involves a single annular junction with a control line requiring precise flux insertion77. Recent advances include asymmetric inline LJJs demonstrating sizable superconducting diode effects78. A suitable platform to observe these effects can be based on Josephson junctions made of nanoislands in the presence of an applied magnetic field13. It is known that giant vortices can be induced by a magnetic field for superconductors with coherence length much smaller than the magnetic penetration depth (e.g., Pb or Nb based nanostructures)13. In particular, as demonstrated by the theoretical and experimental results in ref. 13, for systems with a size approximately five times the coherence length, the application of a magnetic field on the order of tens of millitesla can induce transitions involving changes in the vortex winding configurations. Our calculations are based on a system size and coherence length that align with this analysis. Then, starting from a low magnetic field configuration with a vortex having, for instance, winding \({V}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=1\) nearby the center of the superconducting lead, the transition to a higher winding vortex state by the increase of the magnetic field will be accompanied by a sizable variation of the rectification. Detection of such transitions can be used to probe the high-winding vortex phase.

Along this line, one can also envision a field-free platform79 with circular current flow inducing high-winding vortices that concomitantly yield supercurrent rectification (see Fig. 6). The described setup provides a potential approach to investigating nonreciprocal phenomena through the manipulation of high-winding vortices. By utilizing an external current to induce a vortex in a proximitized superconductor and examining the resulting supercurrent behavior across a weak link, this configuration offers a means to characterize and understand the underlying physics of nonreciprocity in superconducting systems with nontrivial vortex states. Such insights could pave the way for advanced superconducting devices with directional control and enhanced functionalities. Moreover, since a generic phase vortex texture can be expanded in harmonics by employing vortex configurations with different windings, then, in principle, our results provide a toolkit to design the supercurrent rectification for a wide variety of superconducting phase patterns.

An external current source (I1) injects current into a superconductor labeled S (depicted in red). The circulating current influences a nearby proximitized superconductor, \({S}^{{\prime} }\) (shown in orange), leading to the nucleation of an electrically controlled vortex within it79. A supercurrent, I2, flows through a weak link based on \({S}^{{\prime} }\) superconducting leads, where an electrically controlled vortex exists on one side of the junction. The nonreciprocal behavior of I2 can be exploited to identify the nature of the induced vortex.

Method

In this section, we present the model Hamiltonian in real space for the superconducting leads, along with the methodology we used to analyze the current-phase relationship and to identify the maximum supercurrent that can flow in both directions across the junction.

Model Hamiltonian

We consider a planar superconducting weak-link with the geometry shown in Fig. 1a. For convenience, the system size is expressed as \({N}_{y}a\times ({N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}+{N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{N}}}}}+{N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{R}}}}})a\) with Ny being the lateral number of sites, \({N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{L,R,N}}}}}\) the site numbers in the left (L), right (R) and normal (N) region of the superconducting weak-link, and a is the lattice length, respectively. The superconducting order parameter on the left and right side of the junction is given by \({\Delta }_{{{{\rm{L,R}}}}}{e}^{i{\varphi }_{{{{\rm{L,R}}}}}}\).

The Hamiltonian describing the superconducting junction illustrated in Fig. 1 (a) is written as

with φ = φL − φR being the phase difference between the superconducting order parameters in the two sides of the junction and j = (jx, jy) with \({j}_{x}\in [-{N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}+1,{N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{N}}}}}+{N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{R}}}}}]\) and jy ∈ [ − (Ny − 1)/2, (Ny − 1)/2] indicating the site indices in the real space. Here, \(\langle {j}_{x},{j}_{y};{j}_{x}^{{\prime} },{j}_{y}^{{\prime} }\rangle\) indicates the summation within the nearest-neighbor hopping, and \({\widehat{C}}^{{{\dagger}} }({j}_{x},{j}_{y})=[{c}_{{j}_{x},{j}_{y},\uparrow }^{{{\dagger}} },{c}_{{j}_{x},{j}_{y},\downarrow }]\) denotes the creation operator at j. Because we do not consider any symmetry breaking in the normal state, the number of the basis can be \(2({N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}+{N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{N}}}}}+{L}_{x}^{{{{\rm{R}}}}}){N}_{y}\), not \(4({N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}+{N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{N}}}}}+{L}_{x}^{{{{\rm{R}}}}}){N}_{y}\). Then \(\widehat{H}({j}_{x},{j}_{y};{j}_{x}^{{\prime} },{j}_{y}^{{\prime} };\varphi )\) is given by

with the Hamiltonian in the Nambu space \({\widehat{H}}^{{{{\rm{L,N,R}}}}}\) and the tunneling part \({\widehat{H}}_{J}^{{{{\rm{L,R}}}}}\). The detail of the Hamiltonian is described by

with the on-site energy term ε = − 0.25t, the energy gap function with spin-singlet s-wave state \({\Delta }_{{{{\rm{L,R}}}}}{e}^{i{\varphi }_{{{{\rm{L,R}}}}}}\), and the nearest neighbor hopping terms tx,y. In the present study, the pairing amplitude is on-site and included in the local term of the Hamiltonian for the left and right-side superconductors. We point out that the position dependence of the order parameter ΔR(jx, jy; φ) takes into account the change in the phase and amplitude due to the presence of the vortices. This is a convenient approach that can be generally applied for analyzing the effects of nonstandard vortices without explicitly incorporating the source responsible for generating the vortex. The tunneling Hamiltonian is expressed as

with tint = 0.90, the charge transfer amplitude at the interface, setting out the transparency of the junction.

Josephson current and rectification

Next, we consider how the Josephson current flowing in the junction (Fig. 1a) is evaluated. The current phase relation of the Josephson current is obtained by evaluating the variation of the free energy F with respect to the phase bias across the junction, i.e. φ:

with the free energy in a Josephson junction at zero temperature, evaluated as

Here, \({N}_{x}={N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}+{N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{N}}}}}+{N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{R}}}}}\) and Ny denote the total number of sites along the x-direction and along the y-direction, and E(φ) and \(\left|\Phi \right\rangle\) stand for the eigenvalue and eigenstate of \(\widehat{H}(x,y;x{\prime} ,y{\prime} ;\varphi )\). We numerically obtain E(φ) by the full diagonalization of \(\widehat{H}({j}_{x},{j}_{y};{j}_{x}^{{\prime} },{j}_{y}^{{\prime} };\varphi )\) in Eq. (14). The computational analysis is performed at zero temperature, but a thermal change does not qualitatively alter the results. For our purposes, we recall that if time-reversal is broken, then the supercurrent can be expanded in even and odd harmonics with respect to the phase bias variable as

in ref. 62. To assess the nonreciprocal supercurrent due to the presence of the vortex in the junction, we evaluate the rectification amplitude η that is conventionally expressed as

with I+(−) the maximum amplitude of the supercurrent for forward (backward) directions, respectively. For the presented results, we set the energy gap amplitude as ∣Δ0∣ = 0.02t (t is the electron hopping amplitude), the maximum Josephson current value, without vortex, as \({I}_{{{{\rm{0}}}}}=0.012| {\Delta }_{0}| (\frac{2e}{\hslash })\), and the size of the superconducting leads as \({N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}={N}_{x}^{{{{\rm{R}}}}}=\alpha {N}_{y}\) with α being the aspect ratio setting out a square or rectangular shape of the superconductors in the junction. The computation is performed for Ny = 30, and \({z}_{0}^{{{{\rm{L}}}}}=10a\) for the size of the vortex core. A variation of these lengths does not affect the results; thus, for clarity, we introduce the coordinates (jx, jy) in the Josephson junction (Fig. 2a).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Abrikosov, A. A. On the Magnetic properties of superconductors of the second group. Sov. Phys. JETP 5, 1174–1182 (1957).

Vinen, W. F. & Shoenberg, D. The detection of single quanta of circulation in liquid helium II. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A. Math. Phys. Sci. 260, 218–236 (1961).

Bewley, G. P., Paoletti, M. S., Sreenivasan, K. R. & Lathrop, D. P. Characterization of reconnecting vortices in superfluid helium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 13707–13710 (2008).

Gomez, L. F. et al. Shapes and vorticities of superfluid helium nanodroplets. Science 345, 906–909 (2014).

Hadzibabic, Z., Krüger, P., Cheneau, M., Battelier, B. & Dalibard, J. Berezinskii–kosterlitz–thouless crossover in a trapped atomic gas. Nature 441, 1118–1121 (2006).

Allen, L., Beijersbergen, M. W., Spreeuw, R. J. C. & Woerdman, J. P. Orbital angular momentum of light and the transformation of Laguerre-Gaussian laser modes. Phys. Rev. A 45, 8185–8189 (1992).

Lagoudakis, K. G. et al. Quantized vortices in an exciton–polariton condensate. Nat. Phys. 4, 706–710 (2008).

Roumpos, G. et al. Single vortex–antivortex pair in an exciton-polariton condensate. Nat. Phys. 7, 129–133 (2011).

Geim, A. K. et al. Phase transitions in individual sub-micrometre superconductors. Nature 390, 259–262 (1997).

Geim, A. K. et al. Fine structure in magnetization of individual fluxoid states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 1528–1531 (2000).

Morelle, M., Bekaert, J. & Moshchalkov, V. V. Influence of sample geometry on vortex matter in superconducting microstructures. Phys. Rev. B 70, 094503 (2004).

Kokubo, N., Okayasu, S., Kanda, A. & Shinozaki, B. Scanning squid microscope study of vortex polygons and shells in weak-pinning disks of an amorphous superconducting film. Phys. Rev. B 82, 014501 (2010).

Kanda, A., Baelus, B. J., Peeters, F. M., Kadowaki, K. & Ootuka, Y. Experimental evidence for giant vortex states in a mesoscopic superconducting disk. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 257002 (2004).

Cren, T., Fokin, D., Debontridder, F., Dubost, V. & Roditchev, D. Ultimate vortex confinement studied by scanning tunneling spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 127005 (2009).

Cren, T., Serrier-Garcia, L., Debontridder, F. & Roditchev, D. Vortex fusion and giant vortex states in confined superconducting condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 097202 (2011).

Timmermans, M., Serrier-Garcia, L., Perini, M., Van de Vondel, J. & Moshchalkov, V. V. Direct observation of condensate and vortex confinement in nanostructured superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 93, 054514 (2016).

Samokhvalov, A. V. et al. Electronic structure of a mesoscopic superconducting disk: Quasiparticle tunneling between the giant vortex core and the disk edge. Phys. Rev. B 99, 134512 (2019).

Ando, F. et al. Observation of superconducting diode effect. Nature 584, 373–376 (2020).

Bauriedl, L. et al. Supercurrent diode effect and magnetochiral anisotropy in few-layer NbSe2. Nat. Commun. 13, 4266 (2022).

Baumgartner, C. et al. Supercurrent rectification and magnetochiral effects in symmetric Josephson junctions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 39–44 (2022).

Wu, H. et al. The field-free Josephson diode in a van der Waals heterostructure. Nature 604, 653–656 (2022).

Jeon, K.-R. et al. Zero-field polarity-reversible Josephson supercurrent diodes enabled by a proximity-magnetized Pt barrier. Nat. Mater. 21, 1008–1013 (2022).

Nadeem, M., Fuhrer, M. S. & Wang, X. The superconducting diode effect. Nat. Rev. Phys. 5, 558–577 (2023).

Ghosh, S. et al. High-temperature Josephson diode. Nat. Mater. 23, 612–618 (2024).

Lin, J.-X. et al. Zero-field superconducting diode effect in small-twist-angle trilayer graphene. Nat. Phys. 18, 1221–1227 (2022).

Pal, B. et al. Josephson diode effect from Cooper pair momentum in a topological semimetal. Nat. Phys. 18, 1228–1233 (2022).

Yuan, N. F. Q. & Fu, L. Supercurrent diode effect and finite-momentum superconductors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119, e2119548119 (2022).

Pal, S. & Benjamin, C. Quantized Josephson phase battery. Europhys. Lett. 126, 57002 (2019).

Edelstein, V. M. Magnetoelectric Effect in Polar Superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 2004–2007 (1995).

Ilić, S. & Bergeret, F. S. Theory of the supercurrent diode effect in Rashba superconductors with arbitrary disorder. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 177001 (2022).

Daido, A. & Yanase, Y. Superconducting diode effect and nonreciprocal transition lines. Phys. Rev. B 106, 205206 (2022).

He, J. J., Tanaka, Y. & Nagaosa, N. A phenomenological theory of superconductor diodes. N. J. Phys. 24, 053014 (2022).

Turini, B. et al. Josephson diode effect in high-mobility insb nanoflags. Nano Lett. 22, 8502–8508 (2022).

Hou, Y. et al. Ubiquitous Superconducting Diode Effect in Superconductor Thin Films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 027001 (2023).

Sundaresh, A., Väyrynen, J. I., Lyanda-Geller, Y. & Rokhinson, L. P. Diamagnetic mechanism of critical current non-reciprocity in multilayered superconductors. Nat. Commun. 14, 1628 (2023).

Krasnov, V. M., Oboznov, V. A. & Pedersen, N. F. Fluxon dynamics in long Josephson junctions in the presence of a temperature gradient or spatial nonuniformity. Phys. Rev. B 55, 14486–14498 (1997).

Golod, T. & Krasnov, V. M. Demonstration of a superconducting diode-with-memory, operational at zero magnetic field with switchable nonreciprocity. Nat. Commun. 13, 3658 (2022).

Margineda, D. et al. Back-action supercurrent rectifiers. Commun. Phys. 8, 16 (2025).

Golod, T., Rydh, A. & Krasnov, V. M. Detection of the phase shift from a single Abrikosov vortex. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 227003 (2010).

Suri, D. et al. Non-reciprocity of vortex-limited critical current in conventional superconducting micro-bridges. Appl. Phys. Lett. 121, 102601 (2022).

Gutfreund, A. et al. Direct observation of a superconducting vortex diode. Nat. Commun. 14, 1630 (2023).

Gillijns, W., Silhanek, A. V., Moshchalkov, V. V., Reichhardt, C. J. O. & Reichhardt, C. Origin of reversed vortex ratchet motion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 247002 (2007).

Jiang, J. et al. Reversible ratchet effects in a narrow superconducting ring. Phys. Rev. B 103, 014502 (2021).

He, A., Xue, C. & Zhou, Y.-H. Switchable reversal of vortex ratchet with dynamic pinning landscape. Appl. Phys. Lett. 115, 032602 (2019).

Margineda, D. et al. Sign reversal diode effect in superconducting dayem nanobridges. Commun. Phys. 6, 343 (2023).

Paolucci, F., De Simoni, G. & Giazotto, F. A gate- and flux-controlled supercurrent diode effect. Appl. Phys. Lett. 122, 042601 (2023).

Greco, A., Pichard, Q. & Giazotto, F. Josephson diode effect in monolithic DC-SQUIDs based on 3D Dayem nanobridges. Appl. Phys. Lett. 123, 092601 (2023).

Lustikova, J. et al. Vortex rectenna powered by environmental fluctuations. Nat. Commun. 9, 4922 (2018).

Itahashi, Y. M. et al. Nonreciprocal transport in gate-induced polar superconductor SrTiO3. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay9120 (2020).

Fink, H. J. & Presson, A. G. Superheating of the Meissner state and the giant vortex state of a cylinder of finite extent. Phys. Rev. 168, 399–402 (1968).

Bruyndoncx, V. et al. Giant vortex state in perforated aluminum microsquares. Phys. Rev. B 60, 4285–4292 (1999).

Kramer, R. B. G., Silhanek, A. V., Van de Vondel, J., Raes, B. & Moshchalkov, V. V. Symmetry-induced giant vortex state in a superconducting Pb film with a fivefold Penrose array of magnetic pinning centers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 067007 (2009).

Buzdin, A. I. Multiple-quanta vortices at columnar defects. Phys. Rev. B 47, 11416–11419 (1993).

Schweigert, V. A., Peeters, F. M. & Deo, P. S. Vortex phase diagram for mesoscopic superconducting disks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 2783–2786 (1998).

Tanaka, K., Robel, I. & Jankó, B. Electronic structure of multiquantum giant vortex states in mesoscopic superconducting disks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99, 5233–5236 (2002).

Chao, X. H., Zhu, B. Y., Silhanek, A. V. & Moshchalkov, V. V. Current-induced giant vortex and asymmetric vortex confinement in microstructured superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 80, 054506 (2009).

Palonen, H., Jaikka, J. & Paturi, P. Giant vortex states in type i superconductors simulated by Ginzburg-Landau equations. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 25, 385702 (2013).

Amundsen, M. & Linder, J. General solution of 2d and 3d superconducting quasiclassical systems: coalescing vortices and nanoisland geometries. Sci. Rep. 6, 22765 (2016).

Liu, J.-X., Shi, L.-M. & Zha, G.-Q. Giant vortex state in a mesoscopic superconducting thin ring. Phys. C: Superconductivity Its Appl. 588, 1353917 (2021).

Tanaka, Y., Lu, B. & Nagaosa, N. Theory of giant diode effect in d-wave superconductor junctions on the surface of a topological insulator. Phys. Rev. B 106, 214524 (2022).

Josephson, B. D. Possible new effects in superconductive tunnelling. Phys. Lett. 1, 251 (1962).

Golubov, A. A., Kupriyanov, M. Y. & Il’ichev, E. The current-phase relation in Josephson junctions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 76, 411–469 (2004).

Upadhyay, R. et al. Microwave quantum diode. Nat. Commun. 15, 630 (2024).

Castellani, M. et al. A superconducting full-wave bridge rectifier. Nat. Electron. 8, 417–425 (2025).

Ingla-Aynos, J. et al. Efficient superconducting diodes and rectifiers for quantum circuitry. Nat. Electron. 8, 411–416 (2025).

Reichhardt, C. & Olson Reichhardt, C. J. Depinning and nonequilibrium dynamic phases of particle assemblies driven over random and ordered substrates: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 80, 026501 (2016).

Ma, X., Reichhardt, C. J. O. & Reichhardt, C. Braiding Majorana fermions and creating quantum logic gates with vortices on a periodic pinning structure. Phys. Rev. B 101, 024514 (2020).

Golod, T., Iovan, A. & Krasnov, V. M. Single Abrikosov vortices as quantized information bits. Nat. Commun. 6, 8628 (2015).

Sok, J. & Finnemore, D. K. Thermal depinning of a single superconducting vortex in Nb. Phys. Rev. B 50, 12770–12773 (1994).

Milošević, M. V., Kanda, A., Hatsumi, S., Peeters, F. M. & Ootuka, Y. Local current injection into mesoscopic superconductors for the manipulation of quantum states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 217003 (2009).

Veshchunov, I. S. et al. Optical manipulation of single flux quanta. Nat. Commun. 7, 12801 (2016).

Mironov, S. et al. Anomalous Josephson effect controlled by an Abrikosov vortex. Phys. Rev. B 96, 214515 (2017).

Kremen, A. et al. Mechanical control of individual superconducting vortices. Nano Lett. 16, 1626–1630 (2016).

Shimahara, H. Transition from the vortex state to the Fulde–Ferrell–Larkin–Ovchinnikov state in quasi-two-dimensional superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 80, 214512 (2009).

Raissi, F. & Nordman, J. E. Josephson fluxonic diode. Appl. Phys. Lett. 65, 1838–1840 (1994).

Raissi, F. Modeling of the Josephson fluxonic diode. IEEE Trans. Appl. Superconductivity 13, 3817–3820 (2003).

Carapella, G. & Costabile, G. Ratchet effect: Demonstration of a relativistic fluxon diode. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 077002 (2001).

Guarcello, C., Pagano, S. & Filatrella, G. Efficiency of diode effect in asymmetric inline long Josephson junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 124, 162601 (2024).

Amundsen, M., Ouassou, J. A. & Linder, J. Field-free nucleation of antivortices and giant vortices in nonsuperconducting materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 207001 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the EU’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Framework Program under Grant Agreement No. 964398 (SUPERGATE), No. 101057977 (SPECTRUM), by the PNRR MUR project PE0000023-NQSTI, by the PRIN project 2022A8CJP3 (GAMESQUAD), and by the MAECI project “ULTRAQMAT”. M.C. also acknowledges support by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR) PRIN 2022 under the Grant No. 2022LP5K7 (BEAT). M.T.M. and C.O. acknowledge partial support from PNRR MUR project PE0000023-NQSTI - TOPQIN. Y.F. gratefully acknowledges access to the computational facilities of Okayama University. We thank S. Ikegaya and Y. Tanaka for valuable discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.C. conceived and supervised the project. Y.F. developed the theoretical framework and performed the computations, with support from M.C., C.O., and M.T.M. The manuscript was written by Y.F., M.C., and C.O., with contributions from M.T.M., F.G., D.M., A.C., and E.S. The experimental implementation was proposed by M.C., supported by F.G., D.M., E.S., and A.C. All authors - A.C., M.C., Y.F., F.G., D.M., M.T.M., C.O., and E.S. - participated equally in discussing and analyzing the results and their implications at all stages of the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks Max Geier and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fukaya, Y., Mercaldo, M.T., Margineda, D. et al. Supercurrent diode with high winding vortex. Commun Phys 8, 518 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02431-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02431-4