Abstract

Vortex beams (VBs) shift keying is a digital communication technique that encodes data by rapidly switching or shifting the orbital angular momentum (OAM) state of a light beam, improving the performance of free-space optical communication. However, current VB-based shift keying secure systems still face several issues, such as limited capacity, the need for model retraining during key renewal and in some cases, vulnerability to ciphertext-only or known-plaintext attacks. In this article, we address these critical challenges by integrating VB array, phase encoding, spatial coherence modulation and deep learning techniques. By utilizing 9 spatial channels each with 16-ary phase differences in the proof-of-principle experiments, the information content carried by a single symbol reach 36 bits. Moreover, a double-encryption transmission scheme is proposed, leveraging the coherence structure and spatial reading trajectory of the VB array. This method has been experimentally verified to provide ultra-high security at the physical layer, effectively resisting both ciphertext-only and known-plaintext attacks. The corresponding bit error rates and pixel error rates can highly reach at least 3.7 × 10−1 and 8.6 × 10−1, respectively. Our work offers the potential for next generation VB-array-based high security FSO communication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vortex beam (VB) carrying orbital angular momentum (OAM) is a special type of structured light1,2. Its helical phase wave-front can be characterized by a phase factor \(\exp (il\theta )\), where l is the topological charge (TC) and θ is the azimuthal angle. Due to the theoretically unbounded values of TC, it has been utilized for multiplexing data in both quantum and optical information transmission3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13. Meanwhile, the generation of VBs has a variety of mature techniques now available, including spiral holograms14, metasurfaces15, and integrated photonic devices16. Among the VB-based free-space optical (FSO) communication systems, OAM-shift keying (OAM-SK) is a major modulation technique17,18. The unique helical phase of VBs endows the OAM-multiplexing modes with distinct petal-like fringe features along the angular space. These intrinsic features naturally guide the design of OAM-SK, where each OAM-multiplexing mode can be mapped to a specific data symbol19.

Encrypted information transmission techniques have attracted extensive attention from academia and industry as a mean to achieve high-security optical communication20,21. Current deep learning-based VB-based SK encryption communication can be performed using two primary techniques: speckle encryption22,23 and OAM spectrum distortion encryption24,25. In terms of speckle encryption, dynamic scattering media are utilized to transform OAM multiplexing modes into speckles. However, recent studies on this topic demonstrate that the speckle correlation analysis of VBs can exploit the scattering invariance of OAM modes to recover information26,27, potentially making speckle encryption ineffective against ciphertext-only attacks during transmission. Moreover, the large number of speckle patterns introduces significant code redundancy. This disadvantage limits the upper information capacity and increases the computational and time costs, making it impossible to perform rapid key renewal during a known-plaintext attack. For OAM spectrum distortion encryption, additional degrees of freedom, e.g., power orders in power-exponent airy vortex beams24, and phase-only OAM-multiplexing method25 destroy the homogeneity of OAM spectrums, invalidating conventional OAM-sorting schemes13,28. However, these methods also rely on large amounts of training data, and thus limit the upper information capacity and increase the computational costs, leading to the vulnerability to a known-plaintext attack. The comparisons between the mentioned encryption approaches and our proposed approach are presented in Table 1. In summary, this work presents an encrypted approach that achieves higher capacity, eliminates the need for model retraining during encryption key renewal and robust against ciphertext-only or known-plaintext attacks.

In this article, we present an approach for boosting the security and capacity of an FSO communication system using VB array, phase encoding, spatial coherence modulation and deep learning techniques. Our well-designed composite grating enables the generation of controllable VB arrays, allowing the simultaneous transmission of multiple independent data-carrying OAM beams. Different from representing data using different OAM symbols, we convey information via the phase difference between OAM modes, which fully utilizes the spatial bandwidth, as illustrated in Fig. 1, showing significant improvement in spatial multiplexing capacity. By utilizing nine spatial locations, each with 16 possible phase differences in the proof-of-principle experiments, we realize the transmission of 36 bits of information encoded in a single symbol. We demonstrate the simultaneous transmission of nine grayscale images and three true-color images on the application of multi-channel FSO communication, with an average bit error rate (BER) no more than 5.2 × 10−4. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, a double-encryption information transmission technique that fully leverages the coherence structure and spatial reading trajectory of VB arrays is first proposed. Experimental BERs, highly reaching at least 3.7 × 10−1, demonstrate that in both ciphertext-only or known-plaintext attacks, the physical layers are effectively robust. Specifically, the first secure physical layer ensures high security when the transmitter and eavesdropper share either a mode clock or a symbol clock. Moreover, even if the first physical layer is compromised in certain ways, the second secure physical layer can maintain ultra-high security through a flexible key renewal strategy. Our work offers the potential for next-generation VB array-based high-security and capacity FSO communication.

The initial Gaussian width of the light beams, w0 is set at 1.5 mm, and the simulated diffraction distance in free space is 3 m. Radial-index (~LG(1, p, 0)) and azimuthal-index (~LG(l, 0, 0)) shift keying suffer from spatial channel crosstalk, whereas phase-difference shift keying (~LG(±1, 0, Δφ)), due to its minimal beam divergence, enables crosstalk-free multi-channel transmission.

Methods

Principle of multi-channel optical communication

The multi-channel optical communication is a key for multi-user applications. To achieve multi-channel optical communication, a composite grating is designed to generate a controllable VB array. Assuming the incident light field distribution on the grating’s entrance surface is Ein(r), the light field distribution Eout(r) on the exit surface after complex amplitude modulation can be expressed as follows:

where \({{{\rm{T}}}}({{{\bf{r}}}})={\sum }_{i=1}^{N}{\sum }_{j=1}^{M}{t}_{i,j}({{{\bf{r}}}})\exp (i({\xi }_{i}x+{\eta }_{j}y))\) is the transmittance function of the composite grating, r = (x, y) = (r, θ), and ti,j(r) represents the (i×j)th modulated signal. The far-field distribution of Eout(r) can be described by the Fraunhofer diffraction integral, which is as follows:

where \((\cdot )\) represents dot production operation and \(k=\frac{2\pi }{\lambda }\) is the wavenumber, with λ being wavelength. By applying the frequency shift property of the Fourier transform, Eq. (2) can be formulated as follows:

Here, Ein(r) is assumed to be a unit-amplitude plane wave. Equation (3) shows that the far-field distribution of Eout(r) is a weighted superposition of the Fourier transforms of the modulated signals ti,j(r), each with a different k-space shift. As a proof of concept, we demonstrate a 3 × 3 LGVB array (N = M = 3) combined with phase-difference encoding to construct a nine-channel optical communication system. Each modulated signal can be designed as follows:

where \({{{\rm{LG}}}}_{p}^{l}({{{\bf{r}}}})\) is the complex function of Laguerre-Gaussian (LG) mode with radial coefficient p, Δφi,j represents the phase difference loaded onto the (i, j)th information carrier (\({{{\rm{LG}}}}_{0}^{-1}({{{\bf{r}}}})\)), and \({LG}_{0}^{1}({{{\bf{r}}}})\) is served as a reference OAM mode. The continuous phase differences (0 to 2π) are discretized into 16 uniformly quantized levels: \(\Delta {\varphi }_{i,j}\in \{0,\frac{\pi }{8},\frac{2\pi }{8},\ldots ,\frac{15\pi }{8}\}.\) Each level is assigned with a 4-bit binary sequence (e.g., 0 → “0000″, π/8 → ”0001″, 2π/8 → “0010″, etc.). Consequently, the total number of available modes reaches 169, which results in 36 bits per symbol and highlights the potential of our coding scheme. Note that the channel number (N = M = 3) and phase difference interval in this example are chosen solely to illustrate the working principle of the proposed multi-channel system. In practice, larger channel numbers (N, M > 3) and finer phase intervals can further boost channel capacity, as be proven in the discussions of “Recognizable phase difference bandwidth” and “VB array expansion capability”.

High-security optical communication enabled by partial coherence and multi-channel vortices

As illustrated in Table 1, achieving both high-security and high-capacity information transmission using OAM modes still presents several challenges, which include but are not limited to the substantial code redundancy in the encoder and high computational and time cost in the decoder. To address these issues, we seek to obtain an additional effective encoding degree of freedoms. Specifically, we leverage the coherence structure and spatial positions of the VB array to implement high-security and high-capacity information encryption. In the section “Compressive mode representation for spatially partial coherence modulation”, we introduce the fundamental principles of spatial partial coherence modulation with controllable average-mode number (i.e., compressive mode representation). In the section “Principle of the high-security optical communication”, we propose and elaborate on a double-encryption technique that combines a designed coherence structure with the spatial positions of the VB array.

Compressive mode representation for spatially partial coherence modulation

Spatial coherence describes the field fluctuation correlation between spatial Dirac point sources or spatial modes at a certain time frequency. There have been three commonly used spatially coherence modulation techniques, including Van Cittert-Zernike theorem29,30,31,32,33, complex or phase-only transmittance screen34,35,36, and coherent/pseudo-mode representation30,37,38. The former two techniques rely on random mode ensembles, and the modulation efficiency can only be improved by using faster modulators. In contrast, the coherent/pseudo-mode representation technique relies on customized mode ensembles and can further enhance modulation efficiency not only through faster modulators but also by requiring fewer average modes. In our previous work39, we explored an extended pseudo-mode-representation-based approach and found it effective for the specified application, as the required number of average modes can be flexibly controlled. Briefly, we treat the average-mode number as a constraint and employ an algorithm to filter average modes of a random process to achieve a specified spatial coherence structure. However, the mode filtering algorithm requires multiple iterations and lacks a gradient descent mechanism, making this method inefficient. Here, we further enhance this method by theoretically determining the average modes with a specific mode number (even as low as 2).

In this article, we focus on the field fluctuation correlation between two spatial modes (SMs) as an illustrative example. Importantly, this method is also compatible with multiple spatial Dirac point sources or SMs. Compressive mode representation introduces homogeneous phases {vn} to one of the spatial modes. Specifically, the interference field, which also corresponds to the average mode, can be described as follow:

In order to quantify the spatial field fluctuation correlation between two SMs, we employ two key physical quantities. First, the cross-spectral density (CSD) between two SMs is defined as follow:

where i,j take values from {1, 2} and N denotes the number of average modes. Second, by normalizing the CSD, the complex degree of coherence (DOC) can be expressed as follows:

The function \(Arg(\cdot )\) extracts the phase part. When \(| \gamma | =1\), the light field is completely coherent with maximum fluctuation correlation. Conversely, when \(| \gamma | =0\), the light field is incoherent with no fluctuation correlation. Intermediate values of γ indicate partially coherent light fields. The intensity distribution of the interference field between two spatial modes can now be written as follows:

The function \(Re(\cdot )\) and \(| \cdot |\) respectively extracts the real part and the amplitude part. As can be seen from Eq. (8), the interference is directly related to the fluctuation correlation of the field.

Next, we will introduce the technical principle of the compressive mode sample. Since a vector \(A\exp (i\theta )\) with magnitude A less than 1 can be symmetrically decomposed into two unit vectors in the direction of \(\theta \pm arccos(\frac{A}{2})\), the generation of the phase ensemble {vn}, matching the statistical expectation of \({A}_{v}\exp (i{\theta }_{v})\), for a specific average-mode number can be realized by multiple symmetric vector decompositions, allowing the average-mode number to be as small as 2 and flexibly controllable. Specifically, for the case where N is even, the first step is to decompose the vector into \(M(=\frac{N}{2})\) vectors in the direction of θv, and the second step is to obtain N phases through symmetric vector decomposition. In addition, if N is odd, we can first assume that a unit vector is located in the direction of θv, and then the remaining N − 1 vectors can be decomposed using the same method. The pseudocode to generate the phase ensemble is shown in Algorithm 1. To enhance the effectiveness of the subsequent encryption technique, randomness is appropriately introduced in Algorithm 1 at lines 6 and 15. (verification is shown in Supplementary Note 4) However, it should be noted that for other applications, uniform interval segmentation should be employed to ensure complete coverage of all DOCs, overcoming the DOC bandwidth limitation brought by the aforementioned randomness. (Relevant simulation analysis is shown in Supplementary Note 4).

Algorithm 1

Vector decomposition implementation

Input: average-mode number N, magnitude Av, direction θv

Output: phase ensemble vn

Step 1: Vector decomposition in the direction θv

1: \(M\leftarrow Floor[\frac{N}{2}]\)

2: vn ← i

3: while vn ~ isreal do

4: if N is odd then

5: Initialize vn ← [θv]

6: AMs ← 2 × rand([M − 1])

7: AM ← [AMs, N × Av − sum(AMs) − 1] // AM consists of the magnitudes of M vectors in the direction θv

8: else

9: Initialize vn ← []

10: AMs ← 2 × rand([M − 1])

11: AM ← [AMs, N × Av − sum(AMs)]

12: end if

13: end while // Ensuring the feasibility of symmetric vector decomposition of AM by unit vector

Step 2: Vector decomposition in the symmetric direction

1: \({v}_{n}\leftarrow [{\theta }_{v}\pm arccos(\frac{{A}_{N}}{2}),{v}_{n}]\)

2: vn ← shuffle(vn)

Principle of the high-security optical communication

To achieve VB array-based high-security optical communication, encoding dimensions are fully utilized for double encryption, including coherence structure and spatial position. The mechanism of double encryption is illustrated in Fig. 2a. The first-step encryption using coherence structure is depicted in Fig. 2b. First, phase-shift information encoding and off-axis information encoding are applied to the OAM information carrier mode, as explained in Method “Principle of multi-channel optical communication”. Next, the average-mode number encryption process begins by loading a series of customized phases {vn} onto a reference OAM mode, which is then subjected to an off-axis modulation. This process allows the generation of a reference OAM mode ensemble from the same statistical process and is the key step of coherence structure encryption. Then reference OAM modes interfere with the information carrier mode. Owing to the mismatch between the phase differences of the interference average modes and the encoded phase differences, the far-field petal-like intensity patterns of the different interference average modes differ in their rotation angles from the encoded pattern, causing one to retrieve incorrect information from the encrypted VB array, as shown in Fig. 2a. If decryption is required, the average-mode number (different average-mode number corresponds to different coherence structure) must be known, and all corresponding interference average modes must be captured in the far field for incoherent superposition. The far-field intensity of each modulated signal of the interference modes can be expressed as follows:

If not specified, OAMl(r), Av and θv respectively default to \({{{\rm{LG}}}}_{0}^{1}({{{\bf{r}}}})\), 0.5, and 0 in this article.

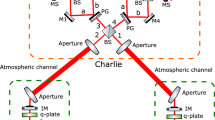

a shows a double-encryption optical communication technique, where the encryption operation is represented by the yellow key symbol. The first key is a varying average-mode number, and the process is exemplified in the dashed black box. The second encryption is a spatial nine-grid decoding trajectory (key 2), where the data is encoded in a grid-like spatial representation with a specific direction, start and end point. b shows a flowchart of average-mode number encryption. The solid lines with different colors represent different channels. The blue dashed boxes correspond to the phase modulation operations of data encoding and average-mode number encryption. The blue solid boxes correspond to the specific operations of data encoding, transmission, and data decryption and decoding.

The second-step encryption is primarily designed to enable flexible key updates without directly varying the physical information carriers. Theoretically, various encryption objects can be devised, such as spatial positions, phase differences between each channel or orders in which modes are addressed in a mode-multiplexed system. In this work, we use spatial position as a validation example. First, to transmit a 36-bit data stream using a single-VB array, one can divide the stream into 9 baud (B1−B9) with an interval of 4 bits, and assign them to channels 1−9 for parallel transmission. Typically, the baud orders correspond directly to the channel orders (e.g., B1 to channel 1, B2 to channel 2). However, for encryption, the transmitter can alter this mapping relationship (e.g., B1 to channel 5, B2 to channel 4). If the receiver decodes the VB array using a mismatched mapping relationship (incorrect decoding trajectory), the resulting information will be incorrect, thereby ensuring the security of the communication. The 3 × 3 grid structure of the nine-grid array inherently allows for 362,880 (i.e., \({A}_{9}^{9}\)) distinct mapping relationships for encryption. To further enhance the security of the encrypted information, the transmitter can apply different mapping transformations based on the 3.6 × 106-dimensional vector space at various time intervals, making brute-force decryption impractical without knowledge of the specific encoding transformations.

Results and discussions

The images displayed in Figs. 3a, 5a are sourced from our photo album, and the images displayed in Fig. 3b are the logo of our school, institute, and our research team.

Multi-image parallel transmission

To validate the high-capacity data transmission capability of the proposed scheme, we experimentally demonstrate a nine-channel VB array-coded optical communication system for multi-image parallel transmission. As illustrated in Fig. 3a, we first transmit 100 × 100-pixel grayscale images through each channel. These images are encoded into a sequence of 20,000 holograms (100 × 100 × 2). Consequently, 80,000 kb (100 × 100 × 8) of data were transmitted per channel, resulting in a total data transmission of 720,000 kb across all nine channels. After transmission, the recovered binary sequences in each sub-channel are reshaped into grayscale images, as shown in Fig. 3a.

To evaluate transmission quality, we calculate both the BER and pixel error rate (PER) between the received and original images. BER is defined as the ratio of erroneous bits to the total number of bits (80,000), while PER is calculated by the ratio of incorrectly reconstructed pixels to the total number of pixels (10,000). The detailed results are presented in Supplementary Data 1. The average BER and PER across the nine channels are 5.2 × 10−4 and 2.7 × 10−3, respectively, with maximum values not exceeding 1.6 × 10−3 and 9.3 × 10−3. We further simultaneously transmit three true-color 100 × 100-pixel images to verify the versatility of the proposed scheme. As shown in Fig. 3b, each true-color image is divided into three RGB channels, resulting in a total of nine channels. At this stage, 720,000 kb of data in total are also transmitted. As shown in Supplementary Data 1, the average BER and PER across all channels are 4.0 × 10−5 and 1.7 × 10−4, respectively, with maximum values not exceeding 1.4 × 10−4 and 6.0 × 10−4. Our results demonstrate that each image in every channel has been accurately transmitted and reconstructed, confirming the feasibility of the proposed VB array for high-capacity optical communication and highlighting the effectiveness of multi-channel-coded FSO communication.

Double-encryption scheme for resisting ciphertext-only and known-plaintext attacks

The experimental setup of this section is similar to that in the multi-image parallel transmission. At the transmitter, each pixel’s information of the image is converted into an 8-bit stream, and a 36-bit stream is encoded by a VB array, with each 4-bit baud being transmitted through a specific spatial channel.

Before the discussions about security against decrypted attacks, we should first explore the N’s effective cryptographic space and conclude that statistical inference of the average-mode number is impossible. As shown in the subsection “Recognizable phase difference bandwidth” in the discussion, we will treat a well-trained 48-ary CNN as the tester. We further do some simulations as below. First, a vector decomposition algorithm is applied to generate 1280 mode ensembles satisfying Av = 0.5 and θv = 0 for N ranging from 2 to 45. Next, for each value of N, we generate an average-mode number key following a decreasing order of N, and use it to produce a partially coherent field. This field is then decoded by a CNN. The allowable key bias, denoted as δ, is defined as the maximum deviation such that the CNN’s recognition accuracy remains above 50%. As shown in Fig. 4a, it can be observed that the allowable key bias grows with increasing average-mode number. Most importantly, when the average-mode number ranges from 2 to 25, no key bias is permitted for resisting the statistical inference of the average-mode number key. We therefore identify this as the effective cryptographic space of N. In addition, the statistical inference of the average-mode number requires multiple independent tests using consecutive values of n, through which a consistent statistical structure must be identified. But within the cryptographically effective range of N, no consistent statistical structure can be established across tests performed with different consecutive values of n, making it impossible to reliably infer the true value of N. Therefore, the statistical inference of the average-mode number is impossible.

a The allowable key bias δ versus average-mode number N. b Decryption results of image-encrypted transmission using Encryption Key Group 1. The blue key indicates decryption with the correct key, while the red key corresponds to an incorrect key. The decryption results are displayed with the pixel-value confusion scatter plot between the received and original images. The red dotted line represents the perfect scatter line, with a well-performing communication evidenced by most scatters lying along it. c, d BERs and PERs for different encryption and decryption key groups (which are detailed in the table) under mode-clock-only and symbol-clock-only scenarios.

Against a ciphertext-only attack, where the eavesdropper obtains only the ciphertext without any knowledge of the corresponding plaintext, we have demonstrated that our double-encryption scheme ensures high physical-layer security. This holds true under two specific conditions: if the transmitter and eavesdropper share either a mode clock or a symbol clock. When only the mode clock is shared, the eavesdropper can determine the start and end of each mode but cannot identify symbol temporal boundaries. In addition, when only the symbol clock is shared, the eavesdropper can determine the symbol temporal boundaries but cannot obtain the mode refresh rate.

When the transmitter and eavesdropper share only a mode clock, it is impossible to figure out the encrypted key of the average-mode number by statistical means. Meanwhile, the eavesdropper is also unable to predict the reading trajectory for unknown known-plaintext pairs and high security of the first encrypted physical layer. Under this eavesdropping condition, the eavesdropper with the wrong coherence structure key can not decrypt correctly because it leads to the crosstalk of the temporally continuous mode ensemble. Next, we further demonstrate a double-encryption information transmission system by transmitting a 100 × 100-pixel grayscale image using different encryption protocols to illustrate this fact. Specifically, we use three types of encryption key group, as shown in the table of Fig. 4. To show more decryption performance features using different decryption key groups, the encryption key group is set to average-mode number 2 and reading trajectory 541,236,987 as an example, and the pixel-value confusion scatter plots of the image-decrypted transmission are shown in Fig. 4b. The pixel-value confusion scatter plots show the match between accurate pixel values and predicted pixel values, with a perfect diagonal line formed by scatters indicating an excellent decoding performance. When both the average-mode number and reading trajectory for decryption match the original settings, the pixel scatters exhibit a nearly perfect diagonal line, indicating that information transmission is successful at this stage. However, when incorrect decryption key groups are used, the chaotic pixel distributions demonstrate that the incorrect average-mode incoherent superposition or decoding trajectory is not able to crack our designed encryption system, thus invalidating the information transmission task. In addition, we have transmitted the same image using two other encryption protocols to further demonstrate the high security of the proposed scheme under mode-clock synchronization only. In the specific protocols, one uses an average-mode number of 3, while the other adopts a modified trajectory key of 156,374,892. The BER and PER of the image-encrypted transmission under these different encryption protocols are analysed in Fig. 4c. When both decryption keys (average-mode number and trajectory) are correct, the BERs remain below 4.6 × 10−3 and the PERs below 2.1 × 10−2, indicating the successful information transmission enabled by a well-trained model. When the average-mode number key is incorrect while the trajectory key remains valid, the BERs sharply increase to 4.9 × 10−1 and the PER reaches 9.9 × 10−1. When both keys are incorrect, the decoding model fails completely. Finally, when the trajectory key is incorrect, but the average-mode number key is valid, which is gotten right by luck by the eavesdropper, the BER still rises to at least 3.7 × 10−1 and the PER to 8.6 × 10−1. These three experimental results demonstrate that it is exceedingly difficult for an eavesdropper to successfully retrieve information under a mode-clock-only condition.

When the transmitter and eavesdropper share only a symbol clock, decryption within N’s effective cryptographic space remains infeasible for digital bit communication systems, though potentially feasible for semantic communication systems40,41. However, with the aid of a spatial trajectory key, high security can be restored in both communication scenarios. Regarding the first point, Fig. 4b illustrates that under the symbol-clock-only condition, decryption key group 3 exhibits distinct scatter lines with a noticeable linear bias from the perfect line. Combined with the decryption BER data in Fig. 4c, it can be seen that this increases the BER from 4.9 × 10−1 to at least 5.6 × 10−1, thereby further enhancing the security of non-semantic digital bit communication. It should be noted, however, that adjacent symbols can still be correctly identified. As a result, such a mechanism fails to provide effective protection for semantic encoding systems. As for the second point, the other symbol-clock-only experimental results in Fig. 4b, c demonstrate that this scenario still maintains high security for both semantic and non-semantic digital bit communication systems, which are similar to that observed in mode-clock-only cases.

In a known-plaintext attack scenario where an eavesdropper obtains both plaintext and corresponding ciphertext, the first secure physical layer still provides high security. However, if the eavesdropper manages to compromise the first physical layer, the second physical layer becomes vulnerable with the assistance of known-plaintext-ciphertext pairs. In such cases, a key renewal strategy can be implemented to maintain an ultra-high level of the second physical-layer security. As a principle-demonstration experiment, we further simulate a dynamic key renewal scenario in an encrypted information transmission system, as shown in Fig. 5. We transmit a 100 × 100-pixel grayscale image using the same encoding method as before. Initially, the transmitter and receiver share the same encryption/decryption key groups. During transmission, the transmitter dynamically renews the encryption key, specifically the decoding trajectory, at two random temporal instances (t1 and t2). When the transmitter modifies the decoding trajectory, a 36-bit all-zero bit sequence is transmitted as a marker code group, which is demonstrated in Supplementary Note 5 that desynchronization happens at very low probability. When this unique marker code group is detected, the receiver will be aware that the decoding trajectory has been renewed. When encryption/decryption key synchronization is maintained throughout transmission, the system can achieve error-free decoding with a BER of 3.79 × 10−3. However, when the receiver is only aware of the first key renewal, the top of the image transmitted in the first temporal interval is successfully decoded, while the latter failed, yielding an overall BER of 1.33 × 10−1. In cases where the receiver is not aware of any key renewal before the latter two temporal intervals, the communication is invalid with a significantly higher BER of 2.70 × 10−1. Except for that in the principle-demonstration experiment, absolute information-theoretic security can be further realized by using a one-time pad to protect the second physical layer.

a Visualization process of time-division-based encryption key renewal transmission, represented by keys of different colors. The results comprise the transmitted and received grayscale images, the corresponding BERs, and pixel-value confusion scatter plots. b The correlation of different colors of key and encryption trajectories.

Briefly, in both types of attack, the first secure physical layer ensures high security when the transmitter and eavesdropper share either a mode clock or a symbol clock. Moreover, even if the first physical layer is compromised in certain ways, the second secure physical layer can maintain ultra-high security through a flexible key renewal strategy.

Next, we will score the proposed communication scheme regarding decoding model, recognizable phase-difference bandwidth, VB array expansion capability and optical communication range and symbol rate for further enhancing the performance of the proposed secure communication scheme.

Decoding model

A decoding model based on a simple LeNet-5 CNN architecture is sufficient to support our optical communication and encryption scheme with high accuracy and high speed (~11.2 ms/symbol). The demodulation scheme based on three convolutional layers offers significant potential to reduce both computational and time burden to the hardware device, as demonstrated by the comparison in Table 1 with other work that uses more complex deep learning models. Meanwhile, we believe that the three-convolutional-layer architecture enables fast recognition speeds and has the potential to be migrated to low-loss and highly parallel optical neural networks or optoelectronic neural networks42.

Recognizable phase-difference bandwidth under current decoding model

By representing the information through the phase differences between the modes rather than OAM symbols, the challenges of beam divergence and crosstalk associated with high-order OAM modes are effectively addressed. This encoding scheme ensures that the spatial bandwidth is fully utilized without facing the aforementioned challenges, thereby significantly enhancing the spatial-division multiplexing capacity of the VB array. To accurately decode the information from the VB array, a well-trained CNN is developed to convert the phase differences into corresponding bit sequences, based on the unique relationship between phase difference and rotated light intensity. Since the recognizable phase-difference bandwidth determines the capacity of phase-encoded information, we test smaller intervals within the 0 to 2π phase range, specifically from \(\frac{2\pi }{16}\) to \(\frac{2\pi }{32}\), \(\frac{2\pi }{48}\), \(\frac{2\pi }{64}\), \(\frac{2\pi }{80}\), \(\frac{2\pi }{96}\) and \(\frac{2\pi }{128}\) to determine the minimum detectable phase-difference bandwidth under the current decoder. Note that the structure parameters of the decoder remain invariant, except that the number of nodes in the last FC layer is set to 16, 32, 48, 64, 80, 96, and 128, respectively, to classify finer phase differences. We conduct the simulation analysis using the same hyperparameter list shown in the table of Note 3 in supplement 1, except that the training sample numbers, to obtain the training and testing accuracy of the CNN on different phase-difference-dependent datasets. For each dataset, a total of 120 augmented images for each code are generated, with 100 images used for training and the remaining 20 images used for testing. The results shown in Fig. 6 show that our current decoder can achieve 100% accuracy on the testing sets of a completely coherent beam with a maximum phase-difference bandwidth of \(\frac{2\pi }{64}\) and a partially coherent beam with a maximum phase-difference of \(\frac{2\pi }{48}\).

VB array expansion capability

With sufficient CCD’s aperture and resolution, the scale of the VB array can be expanded from 3 × 3 to 4 × 4 and even 7 × 7, as shown in Fig. 7. It is crucial to highlight that the appearance of speckles and intensity distortions is attributed to the specific design of the phase-only phase masks. These effects can be mitigated through the application of alternative optimization algorithms19,43. As the array grows, the number of available coding modes increases quadratically (e.g., 5 × 5 corresponds to 26×25, 150 bits per symbol) and the number of spatial encryption trajectories grows at a factorial rate (e.g., 5 × 5 corresponds to 25!, 1.55 × 1025 trajectories per symbol), thereby significantly enhancing both communication capacity and security. In further experiments, we achieve decoding accuracies of 0.999 and 0.993, respectively, in 4 × 4 and 5 × 5 arrays with each channel containing 64 arrays. These facts indicate that our proposed approach has the potential for further improvement in communication capacity and security.

Enhancing the communication range and symbol rate

In terms of communication range, the communication link in our experiment spans a distance of 1.5 m. However, the potential communication range of our approach is much greater. Considering sufficient light power, a large enough aperture of the camera device, and an appropriate image-capture strategy to capture the entire light signal, the communication distance could be extended to the order of kilometers17. As the communication distance increases, the light beam inevitably experiences distortions due to atmospheric turbulence (AT) and obstructions. The latter impairments lead to distortions in the intensity distribution, thereby degrading system performance9. Fortunately, there are two main approaches to mitigate these impairments.

First, previous studies have demonstrated that mode purity can be significantly improved through phase compensation techniques, such as the Gerchberg−Saxton (GS) algorithm44 or the stochastic parallel gradient descent algorithm45. Also, advanced deep learning-based adaptive optics methods, such as inverse turbulence phase compensation46,47 and direct light intensity reconstruction48,49, offer effective platforms for mitigating the adverse effects of AT. Second, the flexibility in selecting OAM carriers allows us to choose OAM modes with unique resistance advantages. Examples include but are not limited to: the self-healing vortex beams can effectively mitigate the amplitude truncations of signals by obstacles50,51; the auto-focusing vortex beams can effectively resist turbulence distortions52,53,54; the perfect vortex beams with energy-flow-reversing dynamics, generated by spatial spectrum engineering, not only enable bypassing obstacles and resisting turbulence distortions through energy redistribution, but also have an OAM-independent diffraction divergence angle, which hold potential to alleviate performance limitations caused by insufficient receiver apertures55.

Regarding system data rate, the data rate in our system is limited by the spatial light modulator (SLM) with a minimum response time of 200 ms. In the future, faster transfer speeds can be achieved by using advanced bulk optical components, such as digital micromirror devices (DMDs) with response times on the order of microseconds56. Furthermore, our encoding approach can be integrated with existing modulation techniques, such as wavelength-division multiplexing57, time-division multiplexing58, and polarization-division multiplexing59, to further boost data rates.

Conclusion

In summary, we have proposed an approach to enhance the high security and capacity of the FSO communication system by integrating VB array, phase encoding, spatial coherence modulation and deep learning techniques. As proof-of-principle experiments, we demonstrate multi-image parallel transmission. In the former experiments, nine independent and freely controllable channels can be created directly for parallel transmission, resulting in an information capacity nine times that of traditional single-VB systems. We demonstrate the simultaneous transmission of nine 100 × 100-pixel grayscale images and three 100 × 100-pixel true-color images over a 1.5-m FSO communication link, achieving an average BER of no more than 5.2 × 10−4. The low BER confirms the feasibility of capacity-enhancing multi-channel VB modulation. Additionally, we fully leverages coherence structure and spatial reading trajectory of VB arrays to achieve double encryption. Experimental BERs, highly reaching at least 3.7 × 10−1, demonstrate that in both ciphertext-only or known-plaintext attacks, the physical layers are effectively robust. Specifically, the first secure physical layer ensures high security when the transmitter and eavesdropper share either a mode clock or a symbol clock. Moreover, even if the first physical layer is compromised in certain ways, the second secure physical layer can maintain ultra-high security through a flexible key renewal strategy. Finally, we discuss the recognizable phase-difference bandwidth, decoding model, VB array expansion capability, and optical communication range and symbol rate to highlight the significant potential and future improvement of our work, paving the way for next-generation high-security FSO communications.

Data availability

Data underlying the results presented in this paper are not publicly available at this time but may be obtained from the authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code used in this study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Allen, L., Beijersbergen, M. W., Spreeuw, R. & Woerdman, J. Orbital angular momentum of light and the transformation of Llaguerre-Gaussian laser modes. Phys. Rev. A 45, 8185 (1992).

He, C., Shen, Y. & Forbes, A. Towards higher-dimensional structured light. Light Sci. Appl. 11, 205 (2022).

Zhu, J., Wang, L. & Zhao, S. Security-enhanced and high-resolution fractional orbital angular momentum multiplexing holography. ACS Photonics 11, 4626–4634 (2024).

Liu, R. et al. Multichiral vortex beam for high-quality information encryption. ACS Photonics 11, 3105–3111 (2024).

Winzer, P. J. Making spatial multiplexing a reality. Nat. Photonics 8, 345–348 (2014).

Fang, X., Ren, H. & Gu, M. Orbital angular momentum holography for high-security encryption. Nat. Photonics 14, 102–108 (2020).

Willner, A. E. et al. Utilizing structured modal beams in free-space optical communications for performance enhancement. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 29, 1–13 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Terabit free-space data transmission employing orbital angular momentum multiplexing. Nat. Photonics 6, 488–496 (2012).

Krenn, M. et al. Communication with spatially modulated light through turbulent air across vienna. N. J. Phys. 16, 113028 (2014).

Willner, A. E. et al. Optical communications using orbital angular momentum beams. Adv. Opt. Photon. 7, 66–106 (2015).

Gibson, G. et al. Free-space information transfer using light beams carrying orbital angular momentum. Opt. Express 12, 5448–5456 (2004).

Ren, Y. et al. Free-space optical communications using orbital-angular-momentum multiplexing combined with mimo-based spatial multiplexing. Opt. Lett. 40, 4210–4213 (2015).

Gong, L. et al. Optical orbital-angular-momentum-multiplexed data transmission under high scattering. Light Sci. Appl. 8, 27 (2019).

Huo, P. et al. Tailoring electron vortex beams with customizable intensity patterns by electron diffraction holography. Opto-Electron. Adv. 7, 230184 (2024).

Pu, M. et al. Catenary optics for achromatic generation of perfect optical angular momentum. Sci. Adv. 1, e1500396 (2015).

Zhao, W. et al. All-on-chip reconfigurable generation of scalar and vectorial orbital angular momentum beams. Light Sci. Appl. 14, 1–15 (2025).

Krenn, M. et al. Twisted light transmission over 143 km. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 13648–13653 (2016).

Liu, Z., Yan, S., Liu, H. & Chen, X. Superhigh-resolution recognition of optical vortex modes assisted by a deep-learning method. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 183902 (2019).

Meng, W., Li, B., Luan, H., Gu, M. & Fang, X. Orbital angular momentum neural communications for 1-to-40 multicasting with 16-ary shift keying. ACS Photonics 10, 2799–2807 (2023).

Busse, H. & Hess, B. Information transmission in a diffusion-coupled oscillatory chemical system. Nature 244, 203−205 (1973).

Selimkhanov, J. et al. Accurate information transmission through dynamic biochemical signaling networks. Science 346, 1370–1373 (2014).

Wan, Z., Wang, H., Liu, Q., Fu, X. & Shen, Y. Ultra-degree-of-freedom structured light for ultracapacity information carriers. ACS Photonics 10, 2149–2164 (2023).

Feng, F. et al. Deep learning-enabled orbital angular momentum-based information encryption transmission. ACS Photonics 9, 820–829 (2022).

Yu, X. et al. Multi-dimensional information encrypted transmission and efficient decryption using power-exponent airy vortex beams. J. Light. Technol. 43, 2535−2543 (2024).

Chen, J. et al. Phase-encoding truncated orbital angular momentum modes for high-security and high-capacity information encryption. J. Light. Technol. 42, 3677−3683 (2024).

Ma, R. et al. Orbital-angular-momentum-dependent speckles for spatial mode sorting and demultiplexing. Optica 11, 595–605 (2024).

Ye, Z. et al. Vortex memory effect of light for scattering-assisted massive data transmission. Optica 12, 281–295 (2025).

Huang, H. et al. 100 tbit/s free-space data link enabled by three-dimensional multiplexing of orbital angular momentum, polarization, and wavelength. Opt. Lett. 39, 197–200 (2014).

De Santis, P., Gori, F., Guattari, G. & Palma, C. An example of a collett-wolf source. Opt. Commun. 29, 256–260 (1979).

Gori, F. & Santarsiero, M. Devising genuine spatial correlation functions. Opt. Lett. 32, 3531–3533 (2007).

Lu, X., Wang, Z., Zhan, Q., Cai, Y. & Zhao, C. Coherence entropy during propagation through complex media. Adv. Photonics 6, 046002–046002 (2024).

Peng, D. et al. Optical coherence encryption with structured random light. PhotoniX 2, 6 (2021).

Pang, Z. & Arie, A. Coherence synthesis in nonlinear optics. Light Sci. Appl. 14, 101 (2025).

Hyde IV, M. W. Stochastic complex transmittance screens for synthesizing general partially coherent sources. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 37, 257–264 (2020).

Liu, L. et al. Ultra-robust informational metasurfaces based on spatial coherence structures engineering. Light Sci. Appl. 13, 131 (2024).

Zhu, X. et al. High-speed optical coherence manipulation based on lithium niobate films modulator. PhotoniX 6, 17 (2025).

Wang, F., Lv, H., Chen, Y., Cai, Y. & Korotkova, O. Three modal decompositions of gaussian schell-model sources: comparative analysis. Opt. Express 29, 29676–29689 (2021).

Liu, X. et al. Unlocking secure optical multiplexing with spatially incoherent light. Laser Photonics Rev. 19, 2401534 (2025).

Li, Y. et al. Coherence shaping for optical vortices: a coherence shift keying scheme enabled by deep learning for optical communication. Opt. Lett. 50, 2390–2393 (2025).

Qin, Z., Tao, X., Lu, J., Tong, W. & Li, G. Y. Semantic communications: principles and challenges. Preprint at arXiv:2201.01389 (2021).

Gao, Z., Jiang, T., Zhang, M., Wu, H. & Tang, M. Optical semantic communication through multimode fiber: from symbol transmission to sentiment analysis. Light Sci. Appl. 14, 60 (2025).

Ye, J. et al. Multiplexed orbital angular momentum beams demultiplexing using hybrid optical-electronic convolutional neural network. Commun. Phys. 7, 105 (2024).

Lesem, L., Hirsch, P. & Jordan, J. The kinoform: a new wavefront reconstruction device. IBM J. Res. Dev. 13, 150–155 (1969).

Fu, S., Zhang, S., Wang, T. & Gao, C. Pre-turbulence compensation of orbital angular momentum beams based on a probe and the gerchberg–saxton algorithm. Opt. Lett. 41, 3185–3188 (2016).

Xie, G. et al. Phase correction for a distorted orbital angular momentum beam using a zernike polynomials-based stochastic-parallel-gradient-descent algorithm. Opt. Lett. 40, 1197–1200 (2015).

Liu, J. et al. Deep learning based atmospheric turbulence compensation for orbital angular momentum beam distortion and communication. Opt. Express 27, 16671–16688 (2019).

Jia, Q. et al. Compensating the distorted oam beams with near zero time delay. Appl. Phys. Lett. 121, 011104 (2022).

Lohani, S., Knutson, E. M. & Glasser, R. T. Generative machine learning for robust free-space communication. Commun. Phys. 3, 177 (2020).

Lin, W. et al. Turbulence-tolerant 12-bit/symbol oam shift keying free space optical communication using a two-stage neural network. Opt. Laser Technol. 187, 112758 (2025).

Li, S. & Wang, J. Adaptive free-space optical communications through turbulence using self-healing bessel beams. Sci. Rep. 7, 43233 (2017).

Mphuthi, N. et al. Free-space optical communication link with shape-invariant orbital angular momentum bessel beams. Appl. Opt. 58, 4258–4264 (2019).

Wang, S., Cheng, M., Yang, X., Xu, J. & Yang, Y. Self-focusing effect analysis of a perfect optical vortex beam in atmospheric turbulence. Opt. Express 31, 20861–20871 (2023).

Yan, X., Guo, L., Cheng, M. & Chai, S. Free-space propagation of autofocusing airy vortex beams with controllable intensity gradients. Chin. Opt. Lett. 17, 040101 (2019).

Yan, X., Guo, L., Cheng, M. & Li, J. Controlling abruptly autofocusing vortex beams to mitigate crosstalk and vortex splitting in free-space optical communication. Opt. Express 26, 12605–12619 (2018).

Yan, W. et al. Energy-flow-reversing dynamics in vortex beams: OAM-independent propagation and enhanced resilience. Optica 11, 531–541 (2024).

Ayoub, A. B. & Psaltis, D. High speed, complex wavefront shaping using the digital micro-mirror device. Sci. Rep. 11, 18837 (2021).

Sano, A. et al. Ultra-high capacity wdm transmission using spectrally-efficient pdm 16-qam modulation and c-and extended l-band wideband optical amplification. J. Light. Technol. 29, 578–586 (2011).

Richter, T. et al. Transmission of single-channel 16-qam data signals at terabaud symbol rates. J. Light. Technol. 30, 504–511 (2011).

Chen, Z.-Y. et al. Use of polarization freedom beyond polarization-division multiplexing to support high-speed and spectral-efficient data transmission. Light Sci. Appl. 6, e16207–e16207 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors disclose support for the research of this work from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.12174122), Guangdong provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 2022A1515011482 and 2024A1515010556), and Program of Innovation and Entrepreneurship for Undergraduates (Grant No. 20241057432014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. developed the theory of partial coherence modulation and double encryption, and performed all associated simulations. Weiqing Lin implemented the neural networks, and conducted all related simulations. W.L. was responsible for developing the electronic control system for synchronizing the SLM and CCD. Z.W. designed the experimental setup and performed the experiments. D.D. conceived of and led the project. All authors contributed to data analysis and manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Lin, W., Li, W. et al. Partial coherence and multi-channel vortices enhance high-security free-space optical communication. Commun Phys 9, 10 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02441-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02441-2